Abstract

The integration of generative AI (GenAI) in patient communication presents benefits and challenges. This retrospective observational study analyzed EHR audit logs to assess how 75 healthcare professionals (HCPs) utilized AI-generated drafts for patient messages from October 2023 to August 2024 at a large health system in New York City. Overall utilization was low (19.4%), though prompt refinements improved usage (from 12% to 20%), particularly among physicians. GenAI drafts were generated for all messages, including 80% that received no response, adding to the review burden and potentially undermining efficiency. Text analysis showed HCPs preferred concise, information-rich drafts, with role-based differences—physicians favored shorter drafts, while clinical support staff preferred more empathetic responses. AI-generated drafts reduced message turnaround time by 6.76% despite a marginal increase in required steps (InBasket actions). These findings highlight the need for targeted GenAI deployment strategies, better aligned with clinician workflows and optimized draft generation for improved efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing volume of patient messages in electronic health record (EHR) inboxes reflects a broader shift toward asynchronous, digital care that may be more accessible and efficient for patients1. Without dedicated time or workflow support, healthcare professionals (HCPs) are often left to manage this demand unsustainably, adding to their administrative burden2,3, worsening burnout4,5,6. In response, healthcare systems have implemented various inbox management strategies7 aimed at supporting HCP workload while maintaining patient communication quality. These include filtering low-clinical-value messages, delegating messages to advanced practice providers (APPs) and support staff8, automating message triage9, and implementing billing policies to reduce avoidable patient messages5. However, these interventions have costs and their effectiveness is limited4, highlighting the need for more efficient and scalable solutions to manage the growing patient message volume. To address this, health systems are increasingly deploying large language model (LLM)-based generative artificial intelligence (GenAI)10 to draft message replies11,12,13,14,15. However, its impact on reducing HCP’s efforts to address patient messages remains unclear14,16, and little is known about how these drafts affect response quality and timeliness or affect patient outcomes17,18.

GenAI has shown the ability to apply medical knowledge accurately19,20, and generate contextually relevant responses21,22. Studies evaluating GenAI-drafted responses to patient messages have found them comparable to human responses in acceptability, accuracy, and empathy by both patients and providers14,23,24,25,26. When integrated into the EHR inbox (referred to as the InBasket in our EHR and hereafter in this paper), GenAI can leverage patient-specific information from the EHR and draft responses to patient messages that HCPs can review and edit before sending to patients12,27. This approach can help alleviate the cognitive load associated with responding to patient messages28, that often requires HCPs to navigate through interfaces, search the EHR for relevant information and compose responses while managing other complex clinical tasks, and places competing demands on their working memory29. This process is inefficient due to navigational challenges in EHR, poor interface design, and usability issues including excessive clicks, limited customization (e.g., inability to hide rarely used folders), unclear icons, and confusing layouts30. A recent qualitative study across six health systems identified over 50 EHR-related barriers to efficient message processing31. While reviewing GenAI-generated drafts may require additional time than reviewing patient messages alone14,32, it is unknown whether the time spent is offset by reductions in task-switching and information retrieval from EHR33. Although GenAI has the ability to extract and summarize relevant EHR information34, current implementations fall short of this promise35. Ultimately, the value of GenAI augmentation36 within the InBasket depends on whether and how it streamlines patient communication, improves provider efficiency, and enhances patient outcomes37.

Despite its potential, GenAI adoption in patient communication remains largely experimental, with most institutions piloting but not fully embracing it38. Prior evaluations have provided inadequate evidence of impact on provider efficiency, with many pilot studies reporting low utilization rates by providers11,28. This limited uptake reflects broader skepticism toward digital health technologies39. Concerns include accuracy, liability, reduced autonomy, depersonalized patient interactions, and AI-generated hallucinations (fabricated information that could mislead users)40,41, as well as apprehensions that such tools prioritize institutional efficiency over patient care14. Key limitations of prior evaluations include reliance on simulations and surveys measuring perceived rather than actual utilization, reducing real-world applicability15,24. Studies reporting utilization at the provider-level rather than message-level11,28 risks biasing usage estimates15. Most evaluations emphasize time-based metrics12 while overlooking the complexity of managing patient messages—such as reading inquiries, reviewing charts, and interpreting lab results42,43—tasks that are known contributors to task-switching and cognitive load44,45. EHR audit logs, which provide detailed records of providers’ actions43,46,47,48, can be leveraged for evaluating the utility of GenAI-drafted responses to patient messages37, providing real-world insights into their impact on clinical workflow and efficiency.

This study attempts to address these critical gaps by examining trends in the utilization of GenAI-drafted responses to patient messages over time and across different user roles, and how quality-relevant features of generated drafts influence utilization. It uses EHR audit log data to compare the steps taken by HCPs in managing patient messages, evaluating the impact of using generated drafts on workflow. By identifying factors that facilitate or hinder utilization, this research aims to inform strategies for optimizing GenAI implementation for managing patient messages in clinical practice. The Methods section details the study setting, the GenAI integrated InBasket workflow, the clinical sites that implemented GenAI drafts for patient messages, the roles of participating users in healthcare delivery, and the types of patient messages and corresponding provider activities analyzed.

Results

Sample Description

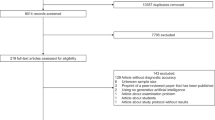

Of the 75 pilot HCPs included in the study, 54 were physicians (72%), 14 were clinical support staff (18.67%), and 7 were administrative support (9.33%). Between October 11, 2023 (when the last pilot HCP onboarded and started seeing GenAI-drafts to patient messages) and August 31, 2024, a total of 55,767 unique patient messages were received that were either addressed to or responded by the HCPs. Approximately 80% (44,454) of these messages (e.g., thank you notes, consecutive patient messages prior to HCP’s response) were resolved without any response sent. For these 44,454 messages, length of GenAI-generated drafts averaged 56 words per message (min: 3, max: 330, SD: 27.56, 95% CI: 55.31 to 55.83). Based on an average adult silent reading rate of 238 words per minute (wpm)49, the estimated mean reading time for these drafts is 13.51 s (min: 0.76 s, max: 83.19 seconds, SD: 6.95 seconds, 95% CI: 13.94 s to 14.08 s) per message, totaling approximately 10,006.29 HCP-minutes relative to 7,389.08 HCP-minutes for reading the patient messages themselves. Of the remaining 11,313 patient messages, drafts were displayed in at least one pilot HCP’s InBasket in 5935 instances (52.5%) and were used as the denominator for calculating overall utilization.

GenAI Draft Utilization

In 1149 of the 5935 eligible instances, HCPs read a patient message and used the “Start with Draft” option to compose a response (see Supplementary Fig. 1), yielding a utilization rate of 19.4%. Only 3.3% (n = 196) of messages were initiated using the “Start Blank Reply” function. Utilization improved significantly over time (F(8,126) = 2.68, p = 0.009) increasing from period 1 with the out-of-the-box prompt (mean= 0.12, SD = 0.13, 95% CI = 0.09–0.18) to its peak in the period 3 (see Supplementary Fig. 2) following the February 28, 2024 super-prompt update (mean=0.20, SD = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.14–0.22). See Supplementary Table 1 for details on prompt changes. HCP type was an important predictor of draft utilization (see Fig. 1). The administrative support group consistently showed the highest utilization across all periods, peaking in period 3 (mean=0.32, SD = 0.12, 95% CI = 0.27–0.37). Physicians’ utilization was at its highest during the final period (mean=0.12, SD = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.10–0.14), while clinical support staff demonstrated their greatest utilization in period 1 (mean=0.14, SD = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.07–0.20) (see Supplementary Table 4). Comparison of utilization across the three periods showed significant differences for physicians (test-stat = 23.74, p < 0.001), but not for the other two groups.

Draft Characteristics Influencing Utilization

The logistic regression model identified several draft characteristics from Table 1 as significant predictors of draft utilization. Among characteristics derived from the draft alone, informativeness (i.e. entropy), sentiment subjectivity, reading ease, affective content and brevity were significant predictors of utilization (see Fig. 2). Specifically, entropy (β = 0.4047, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.125 to 0.685), sentiment subjectivity (β = 0.4050, p = 0.010, 95% CI: 0.098 to 0.711) and Flesch reading score (β = 0.0161, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.011 to 0.022) were all positively associated with utilization. Mean sentence length also showed a positive association with utilization (β = 0.0549, p = 0.002), but word count was negatively associated with utilization (β = -0.0108, p < 0.001, 95% CI: -0.017 to -0.005), suggesting that users preferred drafts with fewer, but more informative sentences. Relating draft characteristics to patient messages, semantic similarity with patient messages was positively linked with utilization (β = 1.2968, p < 0.001, 95% CI: 0.759 to 1.835), while content overlap with patient messages had a small but significant negative effect (β = -0.3032, p = 0.028, 95% CI: -0.574 to –0.033).

The importance of draft characteristics as determinants of draft utilization varied across HCP types. Post-hoc tests revealed that physicians were less likely to use longer drafts, utilizing those with fewer words than clinical support (mean difference = -9.70, p < 0.001) and administrative support (mean difference = -8.15, p < 0.001). Drafts utilized by physicians also had lower readability, evident by lower Flesch reading ease scores than those used by administrative support (mean difference = -1.99, p < 0.001) and clinical support (mean difference = -2.43, p < 0.001). In contrast, clinical support staff favored drafts with higher affective content than physicians (mean difference = 0.7216, p < 0.001) and administrative support (mean difference = 0.4419, p = 0.012), with similar differences also observed for sentiment subjectivity, entropy scores.

Semantic similarity to patient messages also varied by HCP type, with drafts used by administrative support showing lower semantic similarity to patient messages than those used by physicians (mean difference = -0.0189, p < 0.001) and clinical support (mean difference = -0.0235, p = 0.008), and lower content overlap with patient messages compared to physicians (mean difference = -0.0264, p < 0.001). These results are consistent with those expected if administrative support users focused their responses more on administrative issues and less on addressing patients’ medical concerns.

Patient and Message Characteristics Influencing Utilization

We also explored whether draft utilization was influenced by factors on the patient side. Patient complexity did not influence draft utilization; after adjusting for age, the mean Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) of patients was 2.22, with no significant difference between groups (difference: -0.13, p = 0.66). To assess whether draft utilization varied depending on the cognitive load required to understand the patient message, we evaluated message complexity and found that message complexity was associated with increased GenAI draft utilization. Messages responded to with GenAI drafts were less readable than those without, as reflected by a lower Flesch reading score (difference: -1.27, p = 0.005) and a higher syllables-per-word count (difference: 0.02, p = 0.01). No significant differences were observed in lexical diversity or sentence length (see Supplementary Table 5).

Overall, these findings show that draft characteristics, particularly information content, relevance and completeness are key factors influencing the likelihood of message utilization, but the importance of these factors varied across HCP types. They also suggest that HCPs used GenAI drafts when the messages patients sent were more difficult to understand with respect to readability.

Efficiency Evaluation

HCPs responded to 11,313 patient messages, generating 52,397 InBasket actions, with an average of 4.65 actions per message (range: 2–113; SD: 3.4; 95% CI: 4.59-4.72). A subset (7.41%, n = 838) of patient messages were missing second-level timestamps in action logs, leaving 10,475 messages for time analysis. The median turnaround time was 354 s (IQR: 14,264 seconds). The median message open time was 55 seconds (IQR: 5,097 seconds) and the median time since last opened was 17 seconds (IQR: 61 seconds). Among the 20 distinct action types recorded (Supplementary Table 3), view reports, which involve opening the message without any additional steps taken, accounted for 56.4% (n = 29,540) of all actions. On average, each message required 2.76 unique actions (range: 2–7; SD: 0.8; 95% CI: 2.75–2.78) and 1.89 repeated actions (range: 0–106; SD: 3.01; 95% CI: 1.83–1.94). Additionally, messages were forwarded to another HCP in 669 instances, approximately 1 in every 17 messages.

First, we evaluated potential time-related efficiency gains (see Table 2) from GenAI draft utilization by comparing time metrics between messages responded to with and without GenAI drafts (see Fig. 3). Responses utilizing GenAI drafts had a 6.76% shorter median turnaround time than those that did not utilize GenAI drafts (median [utilized]: 331 seconds, median [not utilized]: 355 seconds, difference: -24 seconds, p < 0.001). However, the median message open time increased by 7.27% (median [utilized]: 59 seconds, median [not utilized]: 55 seconds, difference: 4 seconds, p < 0.001), and the median time since last opened (unattended time) increased by 15% (median [utilized]: 23 seconds, median [not utilized]: 20 seconds, difference: 3 seconds, p < 0.001). (See Supplementary Table 6 for additional details).

Box plots and bar charts (with SD as error bars) show distribution of time-related measures and InBasket actions, with the utilized group in blue and non-utilized in orange. Subfigures include: (a) turnaround time, (b) message open time, (c) time since last opened, (d) total actions, (e) unique actions, (f) repeated actions, (g) view report actions, and (h) session counts. Time-related measures (a–c) were log-transformed to account for skewness and reduce the influence of extreme values in the figure.

Given that faster response time when utilizing GenAI drafts could not be explained by earlier message opening or reduced unattended time, we analyzed InBasket actions to understand the source of time efficiency gains. Comparing all InBasket actions for messages in which GenAI drafts were utilized to those in which they were not utilized revealed that HCPs took slightly (1.95%) more actions (mean [utilized]: 4.71, mean [not utilized]: 4.62, difference: 0.09, p = 0.38) per message when utilizing GenAI drafts (see Supplementary Table 7). When removing the reply actions (Reply to patient, Message Patient, and IB suggested response), which differed for GenAI drafts, the difference was even smaller (mean [utilized]: 2.86, mean [not utilized]: 2.84, difference: 0.02, p = 0.45). GenAI draft utilization was associated with an increase in unique actions (mean [utilized]: 2.82, mean [not utilized]: 2.76, mean difference: 0.06, p = 0.02), while repeated actions (mean [utilized]: 1.88, mean [not utilized]: 1.89, mean difference: -0.01, p = 0.94) and message views (mean [utilized]: 2.61, mean [not utilized]: 2.62, mean difference: -0.01, p = 0.73) remained nearly unchanged (see Supplementary Table 7).

While the number of actions differed relatively little, the frequency of a few types of actions differed when responses utilized the GenAI drafts (see Supplementary Table 8). In particular, there were fewer shifts of responsibility (any of the following actions: Take responsibility, Take put back responsibility submenu, Put responsibility back, and Move to My Messages) for responses that utilized GenAI drafts (mean [utilized]: 0.03, mean [not utilized]: 0.07, difference: 0.04, p = 0.04) but more create telephone call (mean [utilized]: 0.03, mean [not utilized]: 0.06, difference: -0.03, p = 0.01), and encounter for medical review actions (mean [utilized]: 0.04, mean [not utilized]: 0.06, difference: -0.02, p = 0.07). Additionally, no significant association was observed between draft utilization and message forwarding among HCPs (χ² = 0.04; p = 0.84; see Supplementary Table 9 for details).

Discussion

In this comprehensive evaluation using electronic health record (EHR) audit logs, we examined how healthcare professionals (HCPs) utilized these drafts in patient communication, assessing differences in utilization across roles, the characteristics of drafts that increase utilization, and the impact of utilization on providers’ efficiency and workload. Our analysis shows overall utilization improved over time but remained low at 19.4%. Our study spanned 11 months, far longer than prior institutional pilots lasting only a few weeks11, yet utilization rates remained as low as early GenAI deployments9, and far lower than the rates implied by experimental findings24. Prompt refinements have significantly improved utilization over time, particularly among physicians.

We applied a novel text-analysis framework to understand how draft content affects use rather than benchmark the underlying large language model (LLM)50, which has been extensively evaluated elsewhere51. Our analysis of the relationship between draft content and utilization rate suggests that drafts with more informative content, greater subjective language and clearer readability were more likely to be utilized. Drafts with greater relevance to the patient message were used more often, but those with higher overlap of content from the patient message were used slightly less. Overall, these findings suggest that drafts likely to serve patient needs better were more likely to be utilized. Some improvement on these dimensions may be achieved with better prompts while further improvement may require fine-tuning the LLM itself but understanding what characteristics most strongly influence utilization enables more efficient progress toward implementation objectives.

Overall draft utilization rates varied by role with administrative support staff consistently demonstrating higher utilization, regardless of prompt updates. These findings mirror those in other sectors that have demonstrated GenAI’s ability to bridge expertise gaps for lower-skilled workers52. If similar benefits are realized in patient communication, it could enhance efficiency by enabling support staff—who typically handle fewer messages53— to manage a larger share of routine patient interactions, particularly those that do not require input from physicians or specialists. By improving communication quality, GenAI can catalyze the professional development of support staff and enhance patient care.

The draft qualities that most strongly influenced utilization differed across HCP roles, suggesting that implementation success may depend on customizing the technology to user role. Physicians preferred shorter yet more complete drafts, while clinical support staff utilized drafts with more affective content, suggesting that they prioritized expressing empathy in patient interactions54. Administrative support staff, in contrast, utilized drafts less relevant to patient messages, which can be expected due to their non-clinical advisory role. These role-based differences emphasize the need for AI-generated drafts to be tailored not only for content quality but also for appropriate use across HCP groups15.

Overall, draft utilization was greater when the original patient message was less readable. Prior work has shown that InBasket management is time-consuming, burdensome and burnout-inducing55. More complex and difficult to understand patient messages exacerbate cognitive load. Team-based care interventions designed to aid InBasket management redirect less complex messages to non-physician HCP’s, but do so without alleviating the cognitive load of complex patient messages8,55. The inverse relationship between reading complexity and utilization may reflect demand for GenAI that succinctly summarizes patient messages in accessible language that requires less effort to reply to, but this could potentially raise safety concerns.

The burnout and burden associated with InBasket work has sparked interest in GenAI solutions that can increase HCP’s InBasket management efficiency. HCPs are familiar with technologies portrayed as increasing efficiency that in practice impose new and greater time demands that sap efficiency56. Our analysis identified such a risk in the need to review unnecessary drafts, which were generated and displayed for all patient messages, without considering whether a response is necessary. While it is difficult to determine with certainty whether HCPs read drafts in such cases, our estimates suggest that when drafts are reviewed, they add a significant burden, increasing the time spent on each message by 135.42% compared to reading the patient message alone. Recent perspectives in digital health implementation increasingly emphasize digital minimalism, advocating for a deliberate, optimized approach to avoid overwhelming clinicians57. The core tenets of digital minimalism—“clutter is costly, optimization is vital, and intentionality is essential”—are particularly relevant here58. Even if unnecessary drafts are not always read, their presence adds to InBasket clutter, a known stressor linked to physician burnout59. Prior work in implementation science has highlighted the importance of workflow integration in determining the success of health technologies; poorly integrated tools often fail due to misalignment with end-user needs60. A more targeted AI deployment strategy, focused on high-yield patient message types, can improve acceptance and utilization among HCPs.

Our analysis of message actions and time metrics revealed that AI-generated drafts significantly impact patient message handling. We found evidence that messages completed without drafts required 6.76% more time to complete despite involving similar numbers of actions, suggesting that utilization may streamline message management. These findings are consistent with prior studies that showed, despite AI-generated replies leading to increased read time12, healthcare providers experience lower cognitive load when editing AI-generated drafts for patient responses, compared to writing replies from scratch13. Our data was collected over a longer time period post-implementation when users may have been farther along the learning curve. Notably, message forwarding rates were not significantly associated with draft utilization, indicating that GenAI did not enable support staff to independently handle more patient messages. This suggests that while the drafts improve individual message processing, their impact on broader workflow efficiency remains limited in the current implementation, representing an important area for further analysis and improvement. There is an urgent need to improve draft utilization before GenAI can meaningfully reduce the InBasket burden of patient messages on HCPs.

More fine-grained analysis of actions offers insight into how message handling may change with GenAI draft utilization. Messages completed without drafts involved more shifts of responsibility. On the other hand, those in which drafts were utilized were more likely to involve creating a telephone call, which itself imposes additional time requirements. These results are also consistent with broader research on human-centered AI that suggest automated systems can streamline workflows but may also introduce new complexities or time burdens61.

This study has several limitations

It was conducted within a single health system, and findings may not reflect experiences in other settings with different workflows, staffing models, or patient populations. The evaluation did not include qualitative feedback from HCPs to explain why drafts were or were not used. Additionally, the absence of human annotation and structured review of a random sample of drafts limits insights into draft quality and end-user perceptions. Comparisons across HCP types may be biased due to class imbalance, with physicians comprising the majority of users. Temporal factors such as holiday schedules may have further influenced message volume and draft utilization. Despite these constraints, our findings provide critical insights into how GenAI-generated drafts impact healthcare communication, highlighting both efficiency gains and future implementation challenges. Broader adoption will require optimization of AI-generated responses to enhance usability and better align with provider needs. Future research should incorporate multi-site, mixed-methods evaluations to capture usage patterns and end-user perspectives, refine draft generation strategies, assess patient perceptions, and ensure that AI integration supports clinical workflows without introducing unintended burdens.

Methods

Settings, and Gen AI integration

This prospective observational quality improvement study was conducted at New York University Langone Health (NYULH), a large academic health system in New York City. A total of 108 HCPs including physicians and their support staff from three clinical sites (two Internal Medicine and one Neurology department) participated in a phased rollout. Prior to using the generated drafts, HCPs were required to accept a one-time disclaimer affirming their understanding and agreement to use the tool responsibly. Only those who completed this step (n = 75) were included in the study; HCPs who did not accept the disclaimer at the time of data collection (n = 33) were excluded from all analyses. Messages designated as non-urgent medical advice requests by patients at submission were routed to the EHR vendor (Epic Systems) upon inbox delivery, which automatically classified them into four predefined groups: general inquiries, test results, medications, and paperwork. Initially, this classification triggered a separate prompt for each category, leveraged patient-specific information from the EHR (e.g., the patient’s problem list, medication list, recent and upcoming appointments) to provide additional context to the message. Later in the study, the process shifted to a unified super prompt, which was used for all message types (see Supplementary Table 1). During the study period, NYULH implemented two rounds of iterative prompt improvement based on initial user feedback, transitioning from an initial out-of-the box prompt from Epic to a more refined prompt that included instructions more specific to the health system’s existing processes (see Supplementary Table 1). GenAI-drafted responses were then seamlessly embedded within the InBasket clinical messaging interface. When HCPs opened a patient message in their InBasket, an AI-generated draft response was displayed alongside the original message, with three response options presented simultaneously on the same screen: (a) “Start with the draft”—use the draft as a starting point, edit as needed, and send; (b) “Start blank reply”—compose response from a blank screen; or (c) use the existing “Reply to patient” function to write a message independently (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Options (b) and (c), functionally redundant in the system design, both allowed HCPs to compose responses from blank screen and were classified as non-utilization of the AI-generated draft.

Data Collection and Measurement

HCPs were classified into three groups based on their service-role: physicians, clinical support (e.g., medical assistants, registered nurses), and administrative support (e.g., patient support associates, front desk, manager) (see Supplementary Table 2). The dataset included all patient-initiated messages managed by participating HCPs during the study period, for which AI-drafted responses were generated and displayed (see Supplementary Note 1 for inclusion exclusion criteria). Each message was assigned a unique identifier by the electronic health record (EHR) system. The data collection process tracked messages using these identifiers through EHR audit logs, capturing clinical activities performed by HCPs from the message’s entry into their InBasket until it was marked as “Done,” signifying that no further action was needed (Fig. 4). This ensured that all relevant actions by HCPs were accurately and chronologically linked to the corresponding messages.

Measuring GenAI Draft Utilization

GenAI draft utilization was defined as the proportion of patient-initiated messages for which HCPs used the generated draft as a starting point for editing and sending a response. Messages were excluded from measuring utilization if they: a) did not require a response (e.g., marked “Done” without a response), b) had unusable drafts, such as a system error message, or c) involved generated drafts that were not displayed to any participating HCP. The latter occurred when HCPs completed messages via an alternative interface where drafts were not shown, despite being enabled in the InBasket (see Supplementary Note 1 for inclusion exclusion criteria). To analyze trends, utilization was evaluated at two-week intervals, mitigating the potential biases of longer monthly periods—influenced by seasonal fluctuations in patient inquiries—and shorter weekly periods, which could be disproportionately affected by provider unavailability. Utilization was further stratified and compared across three time periods defined by GenAI prompt updates: period 1 with out-of-the-box prompt by the EHR vendor (11th October 2023- 6th December 2023), period 2 with first prompt change (7th December 2023- 27th February 2024), and period 3 with second prompt change (28th February 2024- 31st August 2024). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes prompt description, prompt changes, and user feedback on the drafts that informed these revisions (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for inclusion exclusion criteria for prompt revision timeline). The underlying LLM (GPT-4) remained unchanged throughout the study period. Utilization patterns were also analyzed across three HCP categories to identify potential variations. The GenAI implementation resulted in drafts being generated for all messages, regardless of whether a response was needed. The reading time cost of reviewing these drafts was estimated based on an average adult silent reading rate of 238 words per minute (wpm)49.

Draft Linguistic Characteristics Influencing Utilization

To identify factors influencing GenAI-draft utilization, we analyzed the draft characteristics that HCPs likely consider when deciding whether to utilize them. These measures were selected to assess the quality of the generated drafts, not the performance of the language model that produced them, which remained constant throughout the study. We evaluated draft characteristics both independently and in relation to the patient messages. When analyzing drafts alone, we considered brevity, readability, informativeness and empathy– dimensions commonly assessed in prior evaluations of GenAI drafts and considered relevant to both HCP’s decision-making and patient experience14,24,62,63. Brevity was assessed as draft length and was measured by the draft’s word count. Readability was evaluated using the Flesch reading ease score, lexical diversity, mean sentence length, and mean syllables per word. Informativeness was quantified using entropy, a measure of how unpredictable words in text are. Repetitive or redundant text is predictable but not informative, while higher entropy indicates text with rich information content that is generally less predictable64. Empathy was evaluated through LIWC-22 (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count), a widely used tool in social science that analyzes the proportion of prosocial, polite, and affective dimensions65. Additionally, sentiment analysis was performed to measure subjectivity (range: 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater subjectivity) and polarity (range: -1 to 1, with higher values reflecting a more positive tone)66,67.

When evaluating drafts in relation to patient messages, we adopted a question-answering framework derived from the text analysis literature, treating patient messages as questions and drafts as potential answers, with draft quality assessed for relevance and completeness. Relevance was determined by measuring semantic similarity between the draft and the patient’s inquiry using Sentence-BERT (SBERT), a widely used transformer-based model that produces sentence embeddings for efficient comparison68,69. Completeness was evaluated by assessing content overlap, where key terms in patient messages were identified using named entity recognition (NER) and cross-verified against the drafts, following established approaches for clinical information extraction70,71. The SpaCy library, which provides pretrained NER models, was used for entity extraction. Details on these measures are provided in Table 1.

To examine the effect of linguistic characteristics on draft utilization, drafts were categorized as either utilized or displayed but non-utilized by HCPs, and the features of these two groups were compared across the measures described above. This approach allowed us to identify linguistic factors that may facilitate or hinder the adoption of GenAI-generated responses.

Effects of utilization on HCP efficiency

Before evaluating the workflow impact of GenAI-draft utilization, we first considered the variability in patient message complexity, as HCPs likely require more time and effort to respond to more complex messages72, potentially masking any time savings or reductions in tasks associated with using GenAI drafts. However, measuring clinical complexity of the message content on a large scale is resource intensive73. To approximate the clinical complexity of messages, we used two proxies: reading complexity of messages and patient complexity at the time of messaging. Reading complexity was assessed using the same readability measures from Table 1 and the number of questions in patient messages, quantified by counting sentences that began with wh-words (e.g., why, how, where)74. Patient complexity was measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)75, which accounts for their age and comorbidities.

To assess the effect of GenAI drafts on efficiency, we adopted a framework (Table 2) derived from previous research on EHR-related HCP workload and efficiency12,46,76,77. This framework examined both message- and HCP-level effects. At the message level, we examined whether GenAI draft utilization led to time savings or reduced the number of actions needed to complete a patient message. At the HCP level, we analyzed efficiency by examining the proportion of messages forwarded by clinical and administrative support staff, as physicians rarely forward messages. Forwarding was analyzed only for support staff, assuming messages were intended for the physicians they support per standard team-based workflows. We compared the efficiency metrics between messages with utilized and non-utilized drafts while controlling for patient’s clinical complexity and the draft’s reading complexity. This approach captures both immediate and broader efficiency gains from GenAI-draft utilization.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized patient messages, healthcare provider (HCP) actions, and longitudinal utilization trends over two-week intervals, stratified by HCP type. Differences in outcome variables based on GenAI-draft utilization were assessed using univariate analyses at message level. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was evaluated using Levene’s test. When assumptions for parametric tests were not met, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. For significant Kruskal–Wallis results, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Mann–Whitney U tests with Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Draft utilization was predicted using a logistic regression model, with HCP type and linguistic features from Table 2 as predictors, after checking for multicollinearity. Message-level outcomes were analyzed using multivariable regression models adjusting for patient and draft complexity, allowing us to isolate the effect of GenAI-draft utilization on HCP efficiency.

Data availability

The primary data on patient messages, HCP actions, and responses used for analysis were sourced from the electronic health record (EHR) data of the New York University (NYU) Langone Health (NYULH) system, containing protected health information (PHI); as such, they cannot be shared publicly. Access to the underlying data requires a Data Use Agreement and IRB approval from NYU Langone Health and its EHR vendor (Epic). While the full content of patient messages and HCP responses cannot be disclosed, de-identified, aggregated metadata on their characteristics can be made available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code that supports the statistical analyses and the study findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Analysis to process and analyze data was generated with Python v3.11.5.

References

Rotenstein, L. S., Landman, A. & Bates, D. W. The electronic inbox-benefits, questions, and solutions for the road ahead. JAMA 330, 1735–1736 (2023).

Nath, B. et al. Trends in electronic health record inbox messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic in an ambulatory practice network in New England. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2131490 (2021).

Burden, M. & Dyrbye, L. Evidence-Based Work Design - Bridging the Divide. N. Engl. J. Med 392, 1044–1046 (2025).

Mandal, S. et al. Quantifying the impact of telemedicine and patient medical advice request messages on physicians’ work-outside-work. NPJ Digit Med 7, 35 (2024).

Holmgren, A. J., Byron, M. E., Grouse, C. K. & Adler-Milstein, J. Association Between Billing Patient Portal Messages as e-Visits and Patient Messaging Volume. JAMA 329, 339–342 (2023).

Baxter, S. L. et al. Association of Electronic Health Record Inbasket Message Characteristics With Physician Burnout. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2244363 (2022).

Paul Testa, A. S. How We’re Improving Physicians’ Messaging Experience Through Digital Tools, https://medium.com/nyu-langones-health-tech-hub/how-were-improving-physicians-messaging-experience-through-digital-tools-1c0abd8e711b (2022).

Fogg, J. F. & Sinsky, C. A. In-Basket Reduction: A Multiyear Pragmatic Approach to Lessen the Work Burden of Primary Care Physicians. NEJM catalyst innovations in care delivery 4. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.22.0438 (2023).

Si, S. et al. In Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference. 436-456 (PMLR).

Ouyang, L. et al. Vol. 35 (eds Koyejo S. et al.) 27730-27744 (2022).

Garcia, P. et al. Artificial Intelligence-Generated Draft Replies to Patient Inbox Messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e243201 (2024).

Tai-Seale, M. et al. AI-Generated Draft Replies Integrated Into Health Records and Physicians’ Electronic Communication. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e246565 (2024).

Baxter, S. L., Longhurst, C. A., Millen, M., Sitapati, A. M. & Tai-Seale, M. Generative artificial intelligence responses to patient messages in the electronic health record: early lessons learned. JAMIA Open 7, ooae028 (2024).

English, E., Laughlin, J., Sippel, J., DeCamp, M. & Lin, C. T. Utility of Artificial Intelligence-Generative Draft Replies to Patient Messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2438573 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. The effect of using a large language model to respond to patient messages. Lancet Digit Health 6, e379–e381 (2024).

Walker, A., Baxter, S., Tai-Seale, M., Sitapati, A. & Longhurst, C. The bot will answer you now: Using AI to assist patient-physician communication and implications for physician inbox workload. Annals of Family Medicine 21 (2023).

Cavalier, J. S. et al. Ethics in Patient Preferences for Artificial Intelligence-Drafted Responses to Electronic Messages. JAMA Netw. Open 8, e250449 (2025).

Ayers, J. W., Desai, N. & Smith, D. M. Regulate Artificial Intelligence in Health Care by Prioritizing Patient Outcomes. JAMA 331, 639–640 (2024).

Shelmerdine, S. C. et al. Can artificial intelligence pass the Fellowship of the Royal College of Radiologists examination? Multi-reader diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ 379, e072826 (2022).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Zhao, W. X. et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 (2023).

Bubeck, S. et al. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: Early experiments with gpt-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712 (2023).

Johnson, D. et al. Assessing the Accuracy and Reliability of AI-Generated Medical Responses: An Evaluation of the Chat-GPT Model. Res Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2566942/v1 (2023).

Small, W. R. et al. Large Language Model-Based Responses to Patients’ In-Basket Messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2422399 (2024).

Nov, O., Singh, N. & Mann, D. Putting ChatGPT’s Medical Advice to the (Turing) Test: Survey Study. JMIR Med Educ. 9, e46939 (2023).

Sezgin, E., Sirrianni, J. & Linwood, S. L. Operationalizing and Implementing Pretrained, Large Artificial Intelligence Linguistic Models in the US Health Care System: Outlook of Generative Pretrained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) as a Service Model. JMIR Med Inf. 10, e32875 (2022).

Webster, P. Six ways large language models are changing healthcare. Nat. Med. 29, 2969–2971 (2023).

Yan, S. et al. Prompt engineering on leveraging large language models in generating response to InBasket messages. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 31, 2263–2270 (2024).

Baddeley, A. Working memory. Science 255, 556–559 (1992).

Budd, J. Burnout Related to Electronic Health Record Use in Primary Care. J Prim Care Community Health 14, 21501319231166921. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501319231166921 (2023).

Murphy, D. R., Giardina, T. D., Satterly, T., Sittig, D. F. & Singh, H. An Exploration of Barriers, Facilitators, and Suggestions for Improving Electronic Health Record Inbox-Related Usability: A Qualitative Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1912638 (2019).

Hersh, W. Search still matters: information retrieval in the era of generative AI. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 31, 2159–2161 (2024).

Moy, A. J., Cato, K. D., Kim, E. Y., Withall, J. & Rossetti, S. C. A Computational Framework to Evaluate Emergency Department Clinician Task Switching in the Electronic Health Record Using Event Logs. AMIA Annu Symp. Proc. 2023, 1183–1192 (2023).

Alkhalaf, M., Yu, P., Yin, M. & Deng, C. Applying generative AI with retrieval augmented generation to summarize and extract key clinical information from electronic health records. J. Biomed. Inf. 156, 104662 (2024).

Wachter, R. M. & Brynjolfsson, E. Will Generative Artificial Intelligence Deliver on Its Promise in Health Care?. JAMA 331, 65–69 (2024).

Reinhard, P. In Mensch und Computer 2024-Workshopband. https://doi.org/10.18420/muc12024-mci-dc-18360 (Gesellschaft für Informatik eV).

Ko, D. G., Tachinardi, U. & Warm, E. J. Secure messaging telehealth billing in the digital age: moving beyond time-based metrics. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 32, 230–234 (2025).

Idnay, B. et al. Environment scan of generative AI infrastructure for clinical and translational science. Npj Health Syst. 2, 4 (2025).

Borges do Nascimento, I. J. et al. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. npj Digital Med. 6, 161 (2023).

Bang, Y. et al. In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing and the 3rd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers). 675-718.

Ji, Z. et al. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 1–38 (2023).

Akbar, F. et al. Physicians’ electronic inbox work patterns and factors associated with high inbox work duration. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 923–930 (2020).

Kannampallil, T. & Adler-Milstein, J. Using electronic health record audit log data for research: insights from early efforts. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 30, 167–171 (2022).

Ahmed, A., Chandra, S., Herasevich, V., Gajic, O. & Pickering, B. W. The effect of two different electronic health record user interfaces on intensive care provider task load, errors of cognition, and performance. Crit. Care Med 39, 1626–1634 (2011).

Ratanawongsa, N., Matta, G. Y., Bohsali, F. B. & Chisolm, M. S. Reducing misses and near misses related to multitasking on the electronic health record: observational study and qualitative analysis. JMIR Hum. Factors 5, e4 (2018).

Rule, A., Chiang, M. F. & Hribar, M. R. Using electronic health record audit logs to study clinical activity: a systematic review of aims, measures, and methods. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 27, 480–490 (2020).

Sinsky, C. A. et al. Metrics for assessing physician activity using electronic health record log data. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 27, 639–643 (2020).

Amroze, A. et al. Use of electronic health record access and audit logs to identify physician actions following noninterruptive alert opening: descriptive study. JMIR Med. Inf. 7, e12650 (2019).

Brysbaert, M. How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate. J. Mem. Lang. 109, 104047 (2019).

Abbasian, M. et al. Foundation metrics for evaluating effectiveness of healthcare conversations powered by generative AI. NPJ Digit Med. 7, 82 (2024).

Rydzewski, N. R. et al. Comparative Evaluation of LLMs in Clinical Oncology. NEJM AI 1, https://doi.org/10.1056/aioa2300151 (2024).

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D. & Raymond, L. R. Generative AI at work. (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023).

Huang, M. et al. In 2023 IEEE 11th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI). 381-387 (IEEE).

Derksen, F., Bensing, J. & Lagro-Janssen, A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 63, e76–e84 (2013).

Smith, L., Kirk, W., Bennett, M. M., Youens, K. & Ramm, J. From Headache to Handled: Advanced In-Basket Management System in Primary Care Clinics Reduces Provider Workload Burden and Self-Reported Burnout. Appl Clin. Inf. 15, 869–876 (2024).

Sinsky, C. et al. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann. Intern Med 165, 753–760 (2016).

Singh, N., Lawrence, K., Sinsky, C. & Mann, D. M. Digital Minimalism - An Rx for Clinician Burnout. N. Engl. J. Med 388, 1158–1159 (2023).

Newport, C. Digital minimalism: Choosing a focused life in a noisy world. (Penguin, 2019).

Gawande, A. Why doctors hate their computers. The New Yorker 12 (2018).

Greenhalgh, T. et al. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med Internet Res 19, e367 (2017).

Shneiderman, B. Human-centered artificial intelligence: Reliable, safe & trustworthy. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 36, 495–504 (2020).

Hong, C. et al. Application of unified health large language model evaluation framework to In-Basket message replies: bridging qualitative and quantitative assessments. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 32, 626–637 (2025).

Robinson, E. J. et al. Physician vs. AI-generated messages in urology: evaluation of accuracy, completeness, and preference by patients and physicians. World J. Urol. 43, 48 (2024).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. ACM SIGMOBILE Mob. Comput. Commun. Rev. 5, 3–55 (2001).

Pennebaker J. W., B R., Booth R. J., Ashokkumar A., Francis M. E. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC-22, https://www.liwc.app (2022).

He, L. & Zheng, K. How Do General-Purpose Sentiment Analyzers Perform when Applied to Health-Related Online Social Media Data?. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 264, 1208–1212 (2019).

RamyaSri, V., Niharika, C., Maneesh, K. & Ismail, M. Sentiment Analysis of Patients’ Opinions in Healthcare using Lexicon-based Method. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 9, 6977–6981 (2019).

Reimers, N. & Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP) (p. 3982). Association for Computational Linguistics (2019).

Yang, X. et al. Measurement of Semantic Textual Similarity in Clinical Texts: Comparison of Transformer-Based Models. JMIR Med Inf. 8, e19735 (2020).

Dirkson, A., Verberne, S., Kraaij, W., van Oortmerssen, G. & Gelderblom, H. Automated gathering of real-world data from online patient forums can complement pharmacovigilance for rare cancers. Sci. Rep. 12, 10317 (2022).

Lopez, I. et al. Clinical entity augmented retrieval for clinical information extraction. NPJ Digit Med 8, 45 (2025).

Kummervold, P. E. & Johnsen, J. A. Physician response time when communicating with patients over the Internet. J. Med Internet Res. 13, e79 (2011).

Lanham, H. J., Leykum, L. K. & Pugh, J. A. Examining the complexity of patient-outpatient care team secure message communication: qualitative analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e218 (2018).

Klare, G. R. Assessing readability. Reading research quarterly, 62–102 (1974).

Huang, Y. Q. et al. Charlson comorbidity index helps predict the risk of mortality for patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 15, 58–66 (2014).

Lawrence, K. et al. The Impact of Telemedicine on Physicians’ After-hours Electronic Health Record “Work Outside Work” During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Retrospective Cohort Study. JMIR Med Inf. 10, e34826 (2022).

Rule, A. et al. Guidance for reporting analyses of metadata on electronic health record use. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 31, 784–789 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) grants 1928614 and 2129076 (PI: O.N., Co-PIs: D.M., B.M.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M., in collaboration with B.M.W., D.M., and O.N., conceptualized the study. S.M. led data collection with support from V.M. and A.C.S., conducted the analyses, drafted the manuscript, and coordinated the coauthors’ feedback. B.M.W. advised on data analysis. W.S., S.R., A.C.S., and D.M. contributed clinical workflow insights critical to data interpretation and results. A.S. provided expertise in implementation science, shaping the Discussion and future directions. B.M.W. and O.N. supervised the project and contributed substantially to writing, revision, and submission. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mandal, S., Wiesenfeld, B.M., Szerencsy, A.C. et al. Utilization of Generative AI-drafted Responses for Managing Patient-Provider Communication. npj Digit. Med. 8, 591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01972-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01972-w