Abstract

Clinical trial failures are frequently driven by patient heterogeneity and limited sample sizes that obscure treatment effects by diluting statistical power. We introduce NetraAI, a novel explainable artificial intelligence (AI) platform that integrates dynamical-systems modeling, evolutionary long-range memory feature selection, and large-language model (LLM)-generated insights, to discover high-effect-size patient subpopulations (“Personas”) from high-dimensional clinical data. In a Phase II ketamine trial for treatment-resistant depression (n = 63), NetraAI analyzed psychiatric scale data (175/patient) and MRI-derived features (185/patient). NetraAI outperformed traditional machine learning (ML) models in predicting treatment outcomes, improving predictive accuracy by approximately 25-30% and achieving higher sensitivity and specificity in detecting responders. NetraAI identified a 10-clinical variable model that improved predictive AUC by 0.32 over standard machine learning (ML) models and an 8-MRI feature model achieving 95% accuracy and 100% specificity. These findings demonstrate that an explainable dynamical AI approach can leverage small but rich datasets to uncover hidden clinically meaningful subgroups. NetraAI’s precision enrichment strategy has the potential to improve trial success rates and enable personalized medicine by prospectively identifying patients most likely to benefit from a given therapy in oncology, psychiatry, neurodegeneration, and for other disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinical trials are the backbone of evidence-based medicine, yet they often fail to demonstrate efficacy – not necessarily due to inadequate treatments, but because patient heterogeneity dilutes meaningful responses1. Genetic, demographic, disease-specific, and environmental differences among patients can obscure true therapeutic effects, diminish statistical power, and yield ambiguous or negative outcomes2,3. With only 10–20% of drug candidate submissions resulting in regulatory approval—a success rate that has remained unchanged for decades— there is an urgent need for innovative approaches that enhance both efficiency and precision without sacrificing scientific rigor or patient safety4.

A promising solution is enrichment, in which trials prospectively select or stratify patients most likely to respond to therapy. However, identifying these subgroups requires analyzing multi-modal high-dimensional data—from demographic factors, clinical rating scales, to multi-omics and imaging biomarkers—to find multivariate patterns that are not evident via univariate analyses5,6. Traditional subgroup analyses predominately rely on univariate approaches, leaving them statistically underpowered, prone to false discoveries, and unable to capture the complex, multivariate interactions essential for precision stratification3,7,8,9. Moreover, these approaches are typically conducted post-hoc rather than prospectively, limiting their impact on trial design. It is not surprising that failure to pre-identify treatment-responsive subpopulations remains a leading cause of late-stage trial failures1,10,11.

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) hold promise for enrichment by detecting latent responder subgroups in complex data12,13. However, the vast majority of existing ML tools struggle with the n ≪ p problem typical in early-phase trials: small patient numbers but many variables (“small n, large p”)14. Even worse, many ML models operate as “black boxes,” producing outputs with limited interpretability for clinical or regulatory decision-making15,16,17. This underscores a critical need for AI systems that are explainable, reproducible, and capable of robust performance in small cohorts18.

Here, we introduce NetraAI, an explainable AI platform with a dynamical systems core and iterative feature refinement, specifically designed to discover interpretable, high-effect-size patient subpopulations to guide prospective enrichment. NetraAI embeds patients in a high-dimensional geometric space, where outcome-driven clusters naturally emerge. Then, without pruning variables with univariate methods, a standard practice used to avoid enormous computational complexity19,20, NetraAI leverages a long-range memory mechanism to iteratively learn combinations of variables. This process is used to efficiently characterize robust patient subpopulations (“Personas”) through the combination of 2–4 variables and their corresponding intervals as a simple way of identifying favorable patients for a clinical trial. Typically, discovering near-optimal variable combinations that explain differential treatment responses between active and control conditions is combinatorially intractable due to the exponential growth of possible variable subsets and their interactions; however, NetraAI effectively addresses this complexity8,9. The resulting Personas undergo rigorous internal validation via bootstrapping and holdout methods, resulting in distinct, biologically explainable facets of disease dynamics and drug response, rather than arbitrary statistical clusters. The minimal variable combination makes it feasible to identify these patients during clinical trial screening. A Persona-tuned large language model (LLM) transforms these findings into transparent, explainable, clinically-actionable, and regulatory-aligned inclusion/exclusion (I/E) criteria.

This is the first detailed report of NetraAI’s mathematical foundations and analytical methodologies, and demonstrated application to a small Phase II ketamine trial in treatment-resistant depression (TRD) (n = 63). We benchmarked NetraAI against traditional ML and LLM-based approaches for identifying response models and their corresponding driving variables. After deriving each method’s optimal variable set—using clinical scales and MRI features separately— we trained each traditional approach with NetraAI’s insights to measure performance gains. While multi-modal models are feasible, for clarity of exposition, we separate the reporting into unimodal comparisons. Our aim is to show that NetraAI can retrospectively identify responder subpopulations with substantially enhanced treatment effects—offering a practical pathway for how early-phase trials across therapeutic areas (from psychiatry to oncology) might be enriched prospectively to accelerate drug development and improve patient outcomes.

Results

Identification of a high-response subgroup from psychiatric scale data and NetraAI’s performance gain over traditional machine learning methods

Consistent with prior studies, this trial found that ketamine led to greater short-term improvement in depression scores compared to placebo, but not all patients responded robustly21,22. Using psychiatric scale data from this Phase II ketamine trial in TRD (n = 63; 175 variables per patient) with response considered to be a ≥40% improvement on the Montgomery–Ǻsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), we set to identify enriched subpopulations responsive to ketamine.

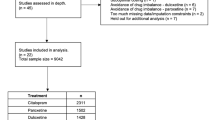

Two workflows were run in parallel—traditional ML and NetraAI-relabeling—to compare performance afforded by NetraAI’s relabeling (Fig. 1). Conventional classifiers (Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and a Deep Neural Network) internally conducted feature selection from the full dataset as part of their training process. Each classifier independently identified and leveraged variables deemed most relevant and predictive for the classification task, reflecting conventional, data-driven ML modeling approaches23. These conventional ML models attempted to learn models by using baseline variables from the dataset to characterize patient populations. The low AUC values for Random Forest (0.27) and Gradient Boosting (0.29) likely stemmed from the combination of small sample size, high dimensionality, class imbalance, and substantial heterogeneity in the unprocessed dataset. Under these conditions, tree-based ensembled methods can overfit to noise, sometimes producing inversely correlated predictions. Overall, conventional ML models produced area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) values between 0.27 ± 0.16 and 0.62 ± 0.15, with accuracy ranging from 44.5% ± 6.3 to 60.3% ± 7.3, and F1 score from 55.0% ± 13.2 to 74.6% ± 5.4 (Table 1), suggesting overfitting and weak signal extraction. This illustrates a broader challenge in clinical trial datasets, unstratified, high-heterogeneity data can cause conventional ML methods to perform no better, or even worse than chance. NetraAI mitigates this by identifying coherent, explainable subpopulations through variable-bundle learning, producing lower-noise feature spaces that are better aligned with the underlying biological signal.

Both workflows are applied to the same trial dataset (n = 63; endpoint ≥40% MADRS improvement at Day 7; 175 baseline clinical scales variable per patient). For the traditional pipeline, four classifiers (Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Deep Neural Network) are used to identify models to characterize ketamine response. Performance is assessed by accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity. For the NetraAI Relabeling Pipeline, NetraAI relabels patients, excludes unexplainable patients, and derives a 10-variable model. The same four traditional classifiers are retrained on the NetraAI-relabeled cohort and reduced feature set, and their post-relabeling metrics are compared to the traditional baseline to quantify performance lift.

As the primary goal of NetraAI is to discover Personas for drug preferential response, the patient population is separated into two categories: placebo non-responders or treatment responders (PNR/TR), the favorable subpopulation, and placebo responders or treatment non-responders (PR/TNR), the unfavorable subpopulation. In this case, the dataset consists of 43 patients in the PNR/TR class and 20 patients in the PR/TNR class. NetraAI utilized its novel approach to introduce an “unknown” or unexplainable class, while learning a 10-variable bundle that defined a set of 26 out of the 63 trial participants, of whom 81% were true PNR/TRs. “Unexplainable” patients are those whose feature profiles do not allow for a stable, interpretable classification within the learned variable bundles that define the responder and non-responder subpopulations. Patients are deemed unexplainable if there is low cluster membership confidence, no coherent subpopulation profile, and ambiguous class separation. Importantly, unexplainable does not mean the patient is an outlier in a purely statistical sense, rather that they cannot be embedded into a stable, high-effect-size, explainable subpopulation within the learned dynamical system. The defining variables for the explainable PNR/TR group were drawn from two clinical scales, consisting of the following: Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS) Derealization, Total Score, Slow Motion, Depersonalization, In a Dream, Take Longer, Amnesia, Colors Diminished, Separated from What is Happening, and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Indecisiveness24,25.

The standard classifiers were retrained exclusively on these features and also took advantage of a label that categorized this 26-subject set as a dependent variable. This yielded dramatic performance improvements in terms of robustness as shown in Table 1. All NetraAI-guided models outperformed traditional approaches, with performance gains exceeding 30 percentage points in AUC, underscoring NetraAI’s ability to define a clinically plausible subpopulation and select a small set of high-impact features to improve classification performance compared to traditional, high-dimensional approaches. While all NetraAI-guided models outperformed their traditional counterparts, the post-NetraAI Naïve Bayes model showed only a marginal change in F1-score (55.0% ± 13.2 vs 54.9% ± 19.5). This likely reflects Naïve Bayes’ simplifying independence assumption, which is not well-suited to the correlated clinical features identified by NetraAI, in contrast to multivariate classifiers that capitalized on these dependencies and showed greater F1 improvements.

MRI-based neuroanatomical model discovery and NetraAI-enhanced classification performance

Using the same approach as outlined above, we evaluated whether structural MRI features (185 volumetric features per patient) could define ketamine-responsive subpopulations. Univariate ANOVA F-test and mutual information was used to score features, where the runs were independent of NetraAI’s input. To provide a more competitive and interpretable baseline, we restricted the analysis to the top 15 features based on ANOVA F-test scores (Table 2), which represented the MRI volumetric features showing the greatest class-wise variability. Naïve Bayes had the best performance with 64% ± 5 accuracy, 60% ± 8 AUC, 68% ± 16 sensitivity, and 55% ± 19 specificity (Table 3). Other traditional models exhibited poor generalization, particularly in specificity, likely due to class imbalance and the small sample size.

Alternatively, NetraAI identified a subgroup of 15 patients, 12 of whom were true PNR/TRs (80%) defined by eight key MRI volumetric reductions: right hippocampus, right posterior cingulate cortex (gray matter), right medial orbitofrontal cortex (gray matter), left inferior temporal gyrus (white matter), left middle temporal gyrus (gray matter), bilateral temporal pole (white matter), right rostral middle frontal gyrus (white matter). Retraining the traditional classifiers using only these NetraAI-identified features achieved up to 100% accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, and an AUC of 1.0 with Gradient Boosting (Table 3). This significantly improved model performance across all metrics, with the greatest relative lift in AUC from 0.34–0.60 to 0.94–1.00, and near complete elimination of false positives, exceeding ordinary variability encountered with standard methods in small datasets.

It is important to note that these near-perfect metrics should not be interpreted as evidence of global predictive accuracy across all patients. Rather, they reflect NetraAI’s ability to isolate a coherent, high-effect-size subpopulation within a limited dataset. Since the sample size remains limited to 63 subjects, these findings should be viewed as hypothesis-generating and requiring replication in independent cohorts and prospective trials. Within this context, the identified brain regions have known associations with depression pathophysiology and ketamine response mechanisms26,27. These volumetric decreases may represent a biologically distinct depressive subtype characterized by reduced structural integrity in emotion- and cognition-related circuits, potentially priming these patients for enhanced responsiveness to ketamine’s synaptic plasticity-promoting effects28,29.

Identification and characterization of NetraAI-derived patient personas

The prior analyses focused on classical ML models trained to distinguish between treatment arms, specifically PNR/TR versus PR/TNR, using either the original dataset or the NetraAI-defined subpopulation. The aim was predictive—to assess whether the provided features and labels could be used to build a model that distinguishes between treatment arms that generalizes well to unseen patients, evaluated using conventional metrics such as accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity. In contrast, Personas serve an explanatory role – a structured representation of a distinct patient type. The purpose of the Persona is to help us understand and define the patients who would preferentially benefit from one treatment over another, in this case, placebo or ketamine. These interpretable profiles provide a transparent framework for prospective trial enrichment, regulatory review, or targeted patient selection.

To identify Personas that characterize preferential response to ketamine, the dataset was split into a 50/50 train/test set for validation. Personas are identified in the training set (n = 32) that are validated with bootstrapping, and those that meet significance thresholds (p < 0.05, Cohen’s D > 0.5) are evaluated for feasibility in the holdout testing set (n = 31). Table 4 shows two Personas identified by NetraAI that characterize patients that demonstrate a preferential response to ketamine.

An LLM tuned with these Personas provided the following output:

“The first profile (Persona 1) appears to identify ketamine responders through a specific white matter signature. The restricted volumes in left posterior cingulate and right inferior parietal white matter tracts suggest altered connectivity within key default mode network components. Given ketamine’s known effects on glutamatergic signaling and rapid synaptic plasticity, these patients likely experience enhanced functional connectivity restoration in these impaired circuits following treatment.

The association with BDI crying/emotional reactivity is particularly revealing. Patients with this neuroanatomical signature appear to experience robust improvements in emotional regulation after ketamine administration. This suggests ketamine may preferentially modulate the emotional processing networks in these individuals, potentially through NMDA receptor-mediated effects on amygdala-cingulate connectivity. Their superior treatment response compared to placebo indicates ketamine may specifically target this dysregulated emotional circuit.

The second phenotype (Persona 2) presents a distinctly different ketamine response predictor based on gray matter morphology. The volumetric pattern in left isthmus cingulate and right lingual regions suggests altered processing in networks involved in interoception and emotional visual processing. Ketamine’s action in these patients likely involves modulation of salience network activity and autonomic regulation.

The correlation with cardiovascular anxiety symptoms (HAMA-09) provides a critical clinical marker. Patients exhibiting this phenotype show preferential improvement in somatic anxiety manifestations after ketamine treatment versus placebo. This suggests ketamine’s mechanism in these responders may involve recalibration of dysregulated interoceptive processing and autonomic hyperarousal through its effects on anterior insula-cingulate connectivity.

From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest two neurobiologically distinct pathways to ketamine response:

-

White matter-mediated emotional regulation circuit restoration (Persona 1).

-

Gray matter-mediated interoceptive/autonomic recalibration (Persona 2).

These profiles could significantly enhance our precision in ketamine therapy. Patients with prominent emotional dysregulation and specific posterior cingulate white matter alterations may represent ideal candidates for ketamine intervention, while those with somatic anxiety features and isthmus cingulate-lingual alterations may constitute another responsive subgroup.

These results can now be used by clinicians and trialists to identify TRD patients that would most likely benefit from ketamine. Moreover, the interpretability of the surviving personas enables real-time clinical reasoning by linking anatomical markers to symptom dimensions. By anchoring treatment decisions in explainable subpopulation dynamics, we reduce reliance on trial-and-error prescribing and move toward a neurobiologically grounded framework for patient stratification. These phenotypes are not only reproducible but also mechanistically plausible, suggesting they can serve as foundations for prospective enrichment strategies in future clinical trials and real-world implementation of precision psychiatry.

Experimental demonstration of NetraAI-driven information gain and dimensionality reduction with minimal loss of predictive power

To assess the information gain capabilities of NetraAI’s combinatorial feature learning and dimensionality reduction, we used a synthetic dataset with >500 features to simulate high-dimensional clinical data. We evaluated how sequentially reducing the feature set— from 500 down to 4 via NetraAI’s long-range memory mechanism impacts predictive performance and information retention. This analysis provides quantitative insights into NetraAI’s ability to identify and retain the most informative feature combinations while discarding redundant or low-informative variables.

NetraAI demonstrated robust dimensionality reduction capabilities. A minimal feature set consisting of only 4 variables retained nearly identical predictive performance, as measured by AUC, compared to the full 500-variable model. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to show that NetraAI-selected features explained the majority of variance present in the original dataset (Fig. 2). Together, these findings illustrate NetraAI’s capacity to generate highly interpretable and simplified models that capture the variability in the patient population and improve the generalizability of the resulting models. By effectively reducing model complexity, NetraAI also mitigates overfitting, promoting generalizability and predictive robustness in clinical research settings19,23.

The cumulative explained variance via PCA demonstrating how each step reduces noise while retaining the core signal. As NetraAI reduced the number of variables to model the patients and discover robust subpopulations, the explanatory power of the models improved. The observed cumulative explained variance is a way to demonstrate the validity of these reductions and the improved robustness of the resulting models.

Discussion

This study introduces NetraAI, a novel, mathematically-augmented ML system designed to optimize clinical trial effectiveness through robust subpopulation discovery and trial enrichment. Unlike many conventional ML tools, NetraAI emphasizes explainability, reproducibility, and clinical relevance through several key innovations: (1) a dynamical systems core that constructs a geometric patient space, (2) evolutionary feature selection with long-range memory, and (3) post-hoc natural language synthesis via a pretrained LLM. Importantly, NetraAI avoids reliance on external datasets, mitigating risks related to bias, population drift, and unaligned data structures30. Instead, it optimally extracts high-quality subpopulations from within a trial’s own data, supporting trial enrichment, early decision-making, and prospective design optimization.

We have demonstrated that this dynamical-systems AI platform can overcome the challenges of patient heterogeneity and high dimensionality in early-phase clinical trials through its application to a small Phase II ketamine trial. Whereas standard models failed to isolate meaningful subgroups, NetraAI discovered a 10-variable psychiatric scale model that enriched for responders with >80% true positives (Table 1). Showing its flexibility across different data types, NetraAI identified an eight-feature neuroanatomical model achieving 100% accuracy and specificity, an up to 60-point improvement in model performance compared to standard classifiers alone (Table 3). These results identified neuroanatomical correlates of response in regions like the hippocampus, cingulate, and orbitofrontal cortex, areas previously implicated in both depression pathology and ketamine’s mechanism of action31,32. These biologically plausible models suggest broader applications in biomarker development, digital phenotyping, and mechanistic stratification. While these neuroanatomical findings are biologically plausible and supported by prior literature, they should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive evidence of mechanistic pathways.

These findings address the pervasive “small-n, large-p” problem in early phase trials, where univariate or black-box ML approaches either overfit or lack interpretability. It is important to consider that small datasets frequently fail to reflect the broader, real-world patient population, limiting the external validity of models derived from them33. A key advantage of NetraAI’s strategy lies in its ability to handle smaller datasets with heterogeneous or incomplete clinical information. Traditional analytical frameworks often attempt to model entire patient populations, which can introduce considerable noise, dilute meaningful signals, and obscure clinically significant subgroups2,8.

However, the focus should be on patient subgroups that can be characterized with some degree of significance, without attempting to explain all patients in a dataset. NetraAI embraces this and deliberately trades exhaustive explanation for greater interpretability and predictive accuracy for clearly defined subpopulations. NetraAI leverages an emergent property that isolates high-effect-size subpopulations—coherent clusters of patients whose outcomes can be explained by a distinct, consistent set of variables. In this approach, patients who fall outside of those well-explained clusters are designated as “unknown,” effectively granting the model the capacity to acknowledge what it cannot classify. By focusing on what can be learned and deliberately excluding cases it cannot explain, NetraAI maximizes the reliability of its predictions, even with limited data. In this context, the reported near-perfect accuracy and specificity of the MRI-based model should not be misinterpreted as evidence that the method can predict treatment response for all patients. Rather, the results underscore NetraAI’s capacity to uncover and validate explainable, biologically coherent subpopulations in which signal-to-noise ratios are strongest. This approach both mitigates concerns of overfitting and highlights the value of NetraAI as a hypothesis generating tool to guide prospective validation in larger, more representative trials.

Furthermore, by treating placebo response as an informative tool rather than a confounder to be statistically removed or controlled, this novel framework refines patient selection and optimizes drug efficacy analysis. In this way, it moves beyond the conventional binary classification of response versus non-response by decomposing the response space into two clinically meaningful subpopulations (PNR/TR and PR/TNR). In doing so, it clarifies treatment efficacy by separating— rather than confounding—drug effects with placebo-driven improvements, ultimately providing a more accurate signal of true therapeutic effect.

Importantly, NetraAI’s built-in LLM component transforms these Personas (Table 4) into language consistent with trial design practices, bridging the gap between AI-driven insights and trial protocol design. By identifying these subpopulations a priori, with transparency, this not only facilitates prospective enrichment, but also supports ethical and equitable trial conduct by making subpopulation definitions explicit and reviewable.

While the current study highlights a specific ketamine trial, NetraAI is therapeutic-area agnostic, with an architecture that can be applied to other diseases or trial datasets. This broader applicability underscores its capacity to advance precision enrichment strategies across diverse clinical research domains.

Despite these strengths, we recognize inherent limitations of the current study. Our analyses used retrospective data with relatively small sample sizes; although bootstrapping and nested holdout testing confirmed stability, external and prospective validation are necessary to confirm generalizability. Specifically, two forms of validation were performed: (1) internal NetraAI validation during training, and (2) a true hold-out validation in which data excluded from variable-bundle discovery were used to test the ability to identify the same Persona in unseen participants. While this hold-out approach confirms that the Personas can be rediscovered in data not used for their derivation, these findings have not yet been tested in an independent ketamine trial, and stronger claims about predictive utility will require replication in larger, prospective cohorts. The most definitive validation of our approach would be for a subsequent clinical trial to employ a previously derived Persona as a covariate and confirm its predictive validity for the same drug; we are presently awaiting the results of such a study.

Furthermore, while the LLM-assisted synthesis of I/E criteria improves interpretability, it remains a prototype step and must be human-reviewed before implementation in trial protocols. We also acknowledge the potential risk of LLM “hallucination,” in which mechanistic explanations, while linguistically coherent and biologically plausible, may not be supported by the underlying data. To mitigate this, the LLM is never tasked with inventing mechanistic rationales de novo; instead, it operates on structured Persona definitions containing explicit variable ranges, effect size metrics, significance measures, and class composition statistics derived directly from NetraAI’s learning process. Any supplementary mechanistic context is drawn from a curated, graph-theory-based compression utilizing Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) of relevant literature and datasets, including regulatory guidance and prior clinical trials, ensuring that references remain anchored in verifiable sources. In this framework, the LLM’s role is augmentative rather than authoritative, with all outputs subject to review and confirmation by domain experts before use in trial design or decision-making. These steps, along with exploration in broader and larger datasets with other modalities—genomic, proteomic, or digital biomarkers—will be essential for establishing NetraAI’s utility and reproducibility.

Looking forward, embedding NetraAI into adaptive trial frameworks could enable real-time enrichment: early data could seed Persona identification, guiding mid-trial enrollment to favor likely responders. Additional studies using NetraAI-derived criteria are underway to apply the platform to oncology and other psychiatry trials. Enhancements to the LLM workflow—including transparent prompt design and iterative expert feedback, will further strengthen the regulatory alignment of the AI-driven Persona insights. Taken together, the present study should be viewed as establishing feasibility and internal reproducibility, while providing a roadmap for future external validation rather than a claim of prospective clinical utility at this stage.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that explainable, dynamical AI can transform early-phase clinical development by identifying and characterizing subpopulations with unprecedented clarity and robustness. By demonstrating feasibility, internal validity, and clinical relevance, this work lays the groundwork for its use. It addresses many critical challenges in the field: overcomes the challenge of trial heterogeneity, demonstrates internal reproducibility even with a small dataset, operates in a therapeutic-area agnostic manner, and provides transparent output interpretable by clinicians and regulators. Demonstrating NetraAI’s full potential, however, will require replication in additional datasets and testing within prospective or adaptive trial workflows, where early signals can guide real-time enrichment decisions. NetraAI is uniquely positioned as an AI tool to support precision medicine initiatives, helping sponsors conduct more targeted efficient, and transparent trials, ultimately bringing therapies to the right patient populations and improving clinical outcomes.

Methods

NetraAI architecture and workflow

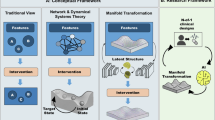

NetraAI is an explainable AI platform that uses a mathematically augmented, iterative ML approach to identify treatment-responsive patient subpopulations. It is specifically designed to address the challenge of capturing complex, high-dimensional interactions between patient features in small, heterogeneous clinical trial datasets that are challenging for traditional ML approaches due to overfitting or obscuring underlying mechanisms. NetraAI’s architecture consists of three key components: (1) a dynamical systems-based clustering engine, (2) an intrinsic long-range memory mechanism and iterative feature learning process, and (3) a post-processing module that fuses validated outputs with a pretrained LLM to produce regulatory-aligned criteria34.

Unlike conventional trial analyses that treat placebo response as a confounding factor to be minimized or eliminated, NetraAI explicitly models placebo response as an informative variable—leveraging it to refine patient selection and optimize drug efficacy analysis. NetraAI moves beyond the conventional binary classification of response versus non-response and instead decomposes the response space into two clinically meaningful subpopulations (Fig. 3):

-

PNR/TR (Placebo non-responders/treatment responders): Patients who do not exhibit a placebo effect, but respond favorably to treatment.

-

PR/TNR (Placebo responders/treatment non-responders): Patients who demonstrate a significant response to placebo, but do not respond meaningfully to the treatment.

This approach is powerful due to the characterization of favorable (PNR/TR) or unfavorable (PR/TNR) subjects, while simultaneously accounting for both the control and active elements of these classes.

Mathematically, NetraAI defines these subpopulations based on observed outcomes:

Where \({Y}_{{placebo}}\) and \({Y}_{{treatment}}\) represent patient response under placebo and treatment conditions, respectively, and \(\delta\) is the threshold for clinically meaningful response. This formulation ensures that NetraAI identifies patient groups that provide the clearest signal of treatment efficacy, rather than confounding drug effects with placebo-driven impairments.

Dynamical system and patient geometry

At the core of NetraAI is a set of discrete iterative function systems (IFS) that adapt dynamically through parameterization. These function systems enable the encoding of all early variables (baseline or screening), including clinical scales, demographics, biomarkers, genetics, and imaging variables, into a geometric space where they act as vertices of a cyclic graph35. This mapping relies on the contraction principles based on the Banach Fixed-Point Theorem to guarantee that patient representations converge into stable attractor states36. These clusters are emergent: no assumptions are made about the distribution or separability of the data. Importantly, the emergent geometry is non-parametric and data-driven, allowing for flexible representation even in small datasets. Further, the long-range memory mechanism, a fundamental emergent property of the dynamical system, allows for the discovery of combinatorial feature learning through a process with linear complexity for each iteration.

According to the Banach Contraction Theorem, a function \(f\) defined on a metric space \(S\) is guaranteed to have a fixed point under iteration if it satisfies:

Thus, there exists a unique fixed-point z such that:

By iterating a carefully chosen function on this space, the geometric image of points begins to contract and cluster, effectively yielding a high-resolution representation of all patients and their relationships based on the driving variables and their sequencing in system evolution. The IFS employed is a dynamical system that maps patients into a two-dimensional space. This is not a projection but an encoding of the most significant driving variables into the mapping of all the patients in each dataset onto this two-dimensional configuration space.

The supervised learning framework in NetraAI follows an iterative process to identify and refine high-effect-size subpopulations consisting of the following steps:

-

1.

Assemble all variables into a single vector.

-

2.

Divide this vector into even segments of size n. Any leftover segments of size <n are randomly mixed and distributed among other segments to ensure all variables have a chance to be considered.

-

3.

The IFS is applied to each segment and scored based on the binary dependent variable (e.g., responder or non-responder) using a loss function. The long-range memory mechanism emerges from the IFS.

-

4.

The purity score is used to evaluate cluster effectiveness.

-

5.

Given the cluster-induced probabilities (pi), the Binary Cross Entropy loss over the entire dataset is:

$${L}_{{BCE}}=-\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}\left[{y}_{i}\mathrm{ln}\left({p}_{i}\right)+\left(1-{y}_{i}\right)\mathrm{ln}\left(1-{p}_{i}\right)\right]$$(5)This is used to evaluate the performance, where \({y}_{i}\in \left\{\mathrm{0,1}\right\}\) represents the true class label, and to find the best models.

-

6.

The best-performing segments are retained while lower-performing segments are discarded.

-

7.

Surviving segments are combined into a new vector, and the process is repeated iteratively (1000 iterations).

-

8.

The final surviving segments define powerful combinations of 2–4 variables, identifying high-effect-size subpopulations aligned with the dependent variable.

The long-range memory mechanism both significantly reduces the complexity of discovering optimal variable combinations and robustly identifies clinically meaningful subpopulations within trial data.

Evolutionary feature selection with long-range memory

To identify the most predictive combinations of variables, NetraAI incorporates an intrinsic long-range memory mechanism that provides a powerful way for multivariate signatures to be found despite the enormous complexity involved. This is paired with methods that are similar to genetic algorithms37. Variable segments that perform well are retained and recombined to form the next generation of potential variable candidates. The long-range memory mechanism allows each iteration to discover hard-to-find combinations of variables. This is made possible because each variable has a sustained, logarithmically decaying influence on other variables within each iteration. This means that surviving sets of variables then influence later iterations38. This approach mitigates the combinatorial explosion associated with feature selection and supports efficient discovery of clinically interpretable subpopulations. The resulting subset of variables defines a perspective that is associated with a subpopulation of patients.

Purity-based optimization and loss function

To quantify how well the clustering captures the dependent variable, we define the cluster-induced probability of belonging to the positive class for cluster Ck as:

where \(|{{\rm{C}}}_{1}|\) and \(|{{\rm{C}}}_{0}|\) denote the number of class-1 and class-0 samples in cluster Ck. Each sample xᵢ ∈ Ck inherits this probability:

The clustering process can be interpreted as minimizing the conditional entropy of the class label Y given the cluster assignment C:

Here, \(P\left(C=k\right)=\frac{\left|{C}_{k}\right|}{N}\) denotes the empirical probability that the cluster-assignment random variable C takes the value k, i.e., the probability that a randomly chosen patient lies in cluster Ck \(P\left(y,|,{C}_{k}\right)\) is the proportion of samples with class Y within Ck; and N is the total number of samples.

Minimizing H(Y|C) is equivalent to minimizing the binary cross-entropy loss across all samples, using the cluster-induced probabilities \({p}_{i}\):

This brings us back to the definition of the loss function in the previous section.

Training, holdout validation, and persona generation

To ensure patient subpopulation discoveries are both predictive and statistically rigorous, the dataset is randomly split into two independent subsets, typically 50% training and 50% holdout sets to ensure findings from the training set can be prospectively validated (Fig. 4). Within the training set, the learning process includes sub-sampling across 1000 iterations and subgroups of single variables, pairs, triples, and quadruples that consistently replicate across 10,000 bootstrap samples are designated as valid Personas.

A dataset undergoes manual wrangling and is randomly split into 50% training and 50% holdout sets. Within the training set, there is a further dataset split, where NetraAI, an iterative process, identifies combinations of variables that consistently predict the binary outcome (e.g., responder or non-responder) to generate Personas. Surviving Personas that meet predefined p-value (p < 0.05) and Cohen’s D (Cohen’s D > 0.5) thresholds for meaningful separation between treatment and control are tested on the holdout set to evaluate generalizability using performance metrics.

Each persona is defined by a minimal set of early-stage features (typically 2–4 variables at screening or baseline) with specific value ranges. These features are interpretable by clinicians and can be directly tied to clinical, biochemical, or demographic characteristics. Once identified, personas are tested on the holdout set to evaluate generalizability and calculate performance metrics (AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity) to reinforce their predictive power. A model is considered successful if it meets the clinical trial’s predefined effect size and p-value (typically Cohen’s D > 0.5 and p < 0.05) thresholds for meaningful separation between the control and treatment groups.

Data lifting and large language model integration

Following Persona discovery, NetraAI “lifts” the structured subgroup data into a format suitable for interpretation by an LLM. The LLM used in this study is a pretrained biomedical transformer (not patient-facing; 4o model of ChatGPT augmented by Keymate.AI) with access to clinical literature, trial design guidelines, and regulatory standards31,39. Exposing NetraAI Personas to an LLM acts as a form of contextual fine-tuning, enabling reasoning over high-signal, explainable subgroups distilled from noisy clinical data.

Each Persona is represented as a compact machine-readable record containing variable definitions and ranges, effect size metrics (Cohen’s D), significance measures (p-values, confidence intervals), and cluster composition details (class proportions, sample sizes). These records are provided in JSON format alongside natural-language descriptors, enabling the LLM to generate human-readable explanations and I/E criteria that remained consistent with the quantitative boundaries defined by NetraAI.

In parallel, DAG-based compression of relevant literature, including regulatory guidance and prior clinical trial publications, allows the model to operate on a distilled, coherent representation of supporting evidence. This dual-format, context-rich approach enhances relevance, reduces hallucination risk, and improves reproducibility when synthesizing discovered Personas into enriched trial protocols, I/E criteria, and explanatory notes grounded in biomedical context.

For example, if NetraAI identifies the following Persona:

LLM outputs are reviewed and curated by clinical experts before use. The LLM does not drive patient selection autonomously; rather, it enhances explainability and aligns subgroup findings with clinical knowledge and regulatory frameworks, providing: (1) disease state representation from multiple validated perspectives, (2) adaptive I/E criteria optimization, and (3) regulatory-grade generalization with retained trial-specificity, moving toward prospective, adaptive, and AI-enhanced patient recruitment strategies.

Perspective analytics

NetraAI proves multiple Personas, offering multiple lenses or “perspectives” on the patient population to yield more comprehensive trial design insights. This Perspective Analytics framework allows for the systematic extraction of multiple distinct, validated models that each represent an interpretable facet of the disease and drug response landscape rather than a single monolithic one. By leveraging Perspective Analytics, NetraAI provides structured, interpretable, and clinically meaningful insights, enabling clinicians and regulators to evaluate patient subgroups from different validated vantage points. This approach supports adaptive, inclusive, and data-driven trial optimization.

By embracing a multi-perspective insight space, where each validated Persona contributes to a more complete, structured understanding of treatment effects, NetraAI moves beyond singular statistical models that force homogeneity on trial data.

Mathematically, let \({\mathcal{D}}\) represent the original, heterogeneous clinical trial dataset. The lifting process, \({\mathcal{L}}\) maps this raw dataset into a structure space of validated Personas \({\mathcal{P}}\), each representing a unique subpopulation with high predictive value:

Where each \({{\mathcal{P}}}_{{\rm{i}}}\in {\mathcal{P}}\) satisfies the following properties:

-

Minimal complexity, maximal predictive power: Each Persona is characterized by a feature set of only 2–4 variables, yet consistently exhibits strong predictive separation between treatment and control groups while aligning with the need for these models to be practically feasible.

-

Holdout generalization: Each Persona must demonstrate statistical robustness on unseen patient data, ensuring that its predictive effect size remains significant beyond the training cohort.

-

Multi-perspective clustering: Rather than reducing patient data to a single explanatory model, NetraAI extracts multiple coexisting Personas, each representing a distinct, yet valid subpopulation structure.

This transformation restructures the dataset into a compact, yet highly informative form, effectively resolving the inherent sparsity and high-dimensional noise of small clinical trials, while ensuring that multiple perspectives on drug response remain accessible for downstream analysis.

The multi-perspective, high-fidelity view of the disease state and drug interaction landscape via Perspective analytics allows the LLM to operate on the structured Persona manifold, extracting higher-order relationships between subpopulations and generalizes I/E criteria. Mathematically, we can describe the interaction between NetraAI’s structured Persona cluster and the LLM as:

Where \({\mathcal{F}}\) represents the LLM-driven synthesis function and \({\mathcal{C}}\) denotes the final set of I/E criteria that have been adapted based on both the trial-specific findings and the LLM’s global biomedical knowledge.

Mathematically, these Personas are essentially low-dimensional rules that define meaningful patient groups. When these structured personas are introduced into an LLM as contextual prompts, they act as a form of soft fine-tuning. Rather than modifying the LLM’s weights, this process conditions the model’s behavior on clinically grounded priors, enabling it to reason over clinically relevant patterns while reducing overfitting and enhancing generalizability. This can be viewed as a form of Bayesian regularization, where each persona introduces a structured prior that guides the model toward more plausible and interpretable outputs, allowing the clinical trialist to see their clinical trial patient population through the lens of the massive medical corpus of data that a foundational model was trained on. By leveraging Perspective Analytics, NetraAI ensures that trial optimization is no longer constrained by statistical limitations, but is instead driven by a synthesis of rigorous, validated subpopulation discoveries and intelligent, generalizable AI insights.

Use case dataset: ketamine trial in major depressive disorder (MDD)

We applied NetraAI to a completed randomized, double-blind crossover Phase II study (NCT00088699) of intravenous racemic ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) as compared to saline placebo for the TRD (n = 33) sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)21,40. Ketamine and placebo infusions were administered two weeks apart in randomized order. All participants were TRD, defined as failure to respond to at least one previous antidepressant trial and were required to have a Montgomery–Ǻsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score of 20 or more before each infusion. Participants were 18-65 years old and free from psychiatric medications at least two weeks before initial ketamine/placebo administration. Participants underwent structural MRI upon initial screening into the study and MEGs before the initial infusion (2–4 days before baseline) and the day of each ketamine/placebo infusion (6–9 h later). The primary outcome was the MADRS, which was assessed, among other measures at baseline, 40 min, 80 min, 120 min, 230 min, 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 7 days, 10 days, and 11 days after infusion.

For the NetraAI analysis, response was considered a ≥40% reduction in MADRS scores from baseline to day 7. Participants were pooled regardless of infusion order to gather all placebo and ketamine responses (n = 63; 3 participant data samples were not usable). Each participant had 175 baseline features, including psychiatric scales, symptom ratings, and lab values. The objective was to characterize PNR/TR (Placebo non-responder/treatment responder) versus PR/TNR (Placebo responder/treatment non-responder) and identify enriched subpopulations responsive to ketamine as shown in the above example.

Here, the goal is to demonstrate the significant advancement in generating robust models through NetraAI’s learning paradigm. A standard subset of powerful ML techniques was used to learn how to distinguish PNR/TR participants from PR/TNR and nested cross-validation was used to evaluate these models.

NetraAI is then employed to model these data and discover which subpopulations are most explainable and by what combination of variables. This information is then provided to standard ML methods through a relabeling of the patient population and a reduction of the independent variables to the ones identified by NetraAI. The new resulting models, if successful, will learn how to identify a desirable subpopulation, identify patients that it cannot predict, and be robust enough to replicate.

MRI analysis substudy

For the same trial population, T1-weighted structural magnetic resonance images (MRIs) were available. We extracted 185 volumetric features per subject (e.g., cortical thickness, subcortical volumes). NetraAI was applied to MRI data to identify neuroanatomical correlates of treatment response.

Parallel machine learning analyses

A series of parallel analyses were conducted to compare the predictive performance of traditional ML classifiers against models utilizing variable subsets derived via NetraAI to evaluate the extent to which NetraAI guided feature selection enhances classification accuracy in identifying strong responders (i.e., PNR/TR) versus weak responders to ketamine treatment.

Specifically, two parallel analytical pipelines were implemented (Fig. 1):

-

1.

Traditional ML classifier pipeline: The full dataset, without prior filtering or dimensionality reduction, was provided to standard ML classifiers, which internally conducted feature selection as part of their training process. The classifiers employed included Naïve Bayes, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Deep Neural Networks (DNN). Each classifier independently identified and leveraged variables deemed most relevant and predictive for the classification task, reflecting conventional, data-driven ML modeling approaches23.

-

2.

NetraAI-guided feature pipeline: NetraAI was independently used to identify high-effect-size variable subsets related to two distinct data domains: (1) clinical rating scales (e.g., MADRS and other psychiatric assessments), and (2) MRI-derived neuroimaging measures (the latter not detailed in this report, but used in parallel analyses). A specific subpopulation identified by NetraAI as strong PNR/TRs was labeled as class “1,” while remaining patients were designated as class “0” (unknown subgroup). These labels provided a binary classification target for subsequent analyses. The ML classifiers were then retrained using only these NetraAI-derived features for each respective domain, allowing for the evaluation of the discriminative power of NetraAI’s feature selection strategy in isolation, without additional feature engineering.

Both pipelines were rigorously evaluated through nested cross-validation, with a 5-fold inner loop for hyperparameter tuning and a 5-fold outer loop for unbiased performance estimation41. Nested cross-validation involves the use of two cross-validation loops: an inner loop dedicated to model selection and hyperparameter optimization, and an outer loop dedicated to estimating the generalization performance of the finalized model. This separation ensures that performance estimates are not optimistically biased by the tuning process, as the outer-loop test data remain completely independent of all training and selection steps. All models were implemented using Python’s scikit-learn library42. Missing data were handled via median imputation applied within each training fold to prevent data leakage. Performance metrics included Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC), classification accuracy, and F1-score, with results presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) across outer cross-validation folds.

This parallel analysis design enabled a direct, fair comparison between traditional model-driven feature selection and NetraAI-guided variable curation, elucidating how these different approaches influence model generalizability and performance.

Dimensionality reduction and information gain experiment

To assess information retention, we used a synthetic clinical dataset with >500 variables and performed stepwise feature elimination (100, 50, 30, 20, 5, 4 variables), guided by NetraAI rankings. For each reduction level, we computed AUC across three classifiers and conducted PCA to estimate cumulative variance explained43. The objective was to evaluate how well NetraAI preserves signal with fewer variables.

Data availability

The clinical trial dataset analyzed in this study is available upon reasonable request from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), led by Dr. Elizabeth Ballard. Access requires appropriate approvals from NIMH in accordance with institutional and regulatory guidelines.

References

Fogel, D. B. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: a review. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 11, 156 (2018).

Kent, D. M. et al. The predictive approaches to treatment effect heterogeneity (PATH) statement. Ann. Intern Med. 172, 35 (2019).

Rothwell, P. M. Treating individuals 2: subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet 365, 176–186 (2005).

Yamaguchi, S., Kaneko, M. & Narukawa, M. Approval success rates of drug candidates based on target, action, modality, application, and their combinations. Clin. Transl. Sci. 14, 1113 (2021).

Drysdale, A. T. et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat. Med. 23, 28–38 (2017).

Chekroud, A. M. et al. Cross-trial prediction of treatment outcome in depression: a machine learning approach. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 243–250 (2016).

Wang, R., Lagakos, S. W., Ware, J. H., Hunter, D. J. & Drazen, J. M. Statistics in medicine-reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2189–2194 (2007).

Lipkovich, I., Dmitrienko, A. & D’Agostino, R. B. Tutorial in biostatistics: data-driven subgroup identification and analysis in clinical trials. Stat. Med. 36, 136–196 (2017).

Foster, J. C., Taylor, J. M. G. & Ruberg, S. J. Subgroup identification from randomized clinical trial data. Stat. Med. 30, 2867–2880 (2011).

Kola, I. & Landis, J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 711–716 (2004).

Trusheim, M. R., Berndt, E. R. & Douglas, F. L. Stratified medicine: strategic and economic implications of combining drugs and clinical biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 287–293 (2007).

Weissler, E. H. et al. The role of machine learning in clinical research: transforming the future of evidence generation. Trials 22, 1–15 (2021).

Harrer, S., Shah, P., Antony, B. & Hu, J. Artificial intelligence for clinical trial design. Trends Pharm. Sci. 40, 577–591 (2019).

Kolluri, S., Lin, J., Liu, R., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, W. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical research and development: a review. AAPS J. 24, 19 (2022).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S. & Guestrin, C. ‘Why should I trust you?’ Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proc. ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 13–17 August 2016, 1135–1144 (ACM, 2016).

Chaddad, A., Peng, J., Xu, J. & Bouridane, A. Survey of explainable AI techniques in healthcare. Sensors 23, 634–634 (2023).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Good Machine Learning Practice for Medical Device Development: Guiding Principles | FDA. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/good-machine-learning-practice-medical-device-development-guiding-principles.

Guyon, I. & De, A. M. An introduction to variable and feature selection André Elisseeff. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 1157–1182 (2003).

Heinze, G., Wallisch, C. & Dunkler, D. Variable selection – A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom. J. 60, 431 (2018).

Ballard, E. D. et al. Functional changes in sleep-related arousal after ketamine administration in individuals with treatment-resistant depression. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 238 (2024).

Price, R. B. et al. International pooled patient-level meta-analysis of ketamine infusion for depression: In search of clinical moderators. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 5096–5112 (2022).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The elements of statistical learning. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-84858-7 (2009).

Bremner, J. D. et al. Measurement of dissociative states with the Clinician-Administered Dissociative States Scale (CADSS). J. Trauma Stress 11, 125–136 (1998).

Wideman, T. H. et al. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine 178–179 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_441 (2013).

Abdallah, C. G., Sanacora, G., Duman, R. S. & Krystal, J. H. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: a window into a new neurobiology for mood disorder therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 66, 509 (2014).

Price, R. B. & Duman, R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 530–543 (2020).

Murrough, J. W., Abdallah, C. G. & Mathew, S. J. Targeting glutamate signalling in depression: progress and prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 472–486 (2017).

Duman, R. S., Shinohara, R., Fogaça, M. V. & Hare, B. Neurobiology of rapid acting antidepressants: convergent effects on GluA1-synaptic function. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1816 (2019).

Gichoya, J. W. et al. AI pitfalls and what not to do: mitigating bias in AI. Br. J. Radio. 96, 20230023 (2023).

Medeiros, G. C. et al. Brain-based correlates of antidepressant response to ketamine: a comprehensive systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 790–800 (2023).

Espinoza Oyarce, D. A., Shaw, M. E., Alateeq, K. & Cherbuin, N. Volumetric brain differences in clinical depression in association with anxiety: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 45, 406 (2020).

van der Ploeg, T., Nieboer, D. & Steyerberg, E. W. Modern modeling techniques had limited external validity in predicting mortality from traumatic brain injury. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 78, 83–89 (2016).

Ganguli, S., Huh, D. & Sompolinsky, H. Memory traces in dynamical systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 18970–18975 (2008).

Barnsley, M. F. & Demko, S. Iterated function systems and the global construction of fractals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 399, 243–275 (1985).

Geraci, J. et al. Machine learning hypothesis-generation for patient stratification and target discovery in rare disease: our experience with Open Science in ALS. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 17, 1199736 (2023).

Holland, J. H. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: an introductory analysis with applications to biology, control, and artificial intelligence. Adapt. Nat. Artif. Syst. https://doi.org/10.7551/MITPRESS/1090.001.0001 (1992).

Chen, J. et al. Quantifying brain-functional dynamics using deep dynamical systems: technical considerations. iScience 27, 110545 (2024).

Keymate.AI stay organized while working with ChatGPT. https://www.keymate.ai/.

Nugent, A. C. et al. Ketamine has distinct electrophysiological and behavioral effects in depressed and healthy subjects. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1040–1052 (2019).

Varma, S. & Simon, R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinform. 7, 1–8 (2006).

Pedregosa FABIANPEDREGOSA, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Giuliani, A. The application of principal component analysis to drug discovery and biomedical data. Drug Discov. Today 22, 1069–1076 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and in particular Dr. Elizabeth Ballard and Dr. Carlos A. Zarate Jr., for providing access to the clinical trial dataset that made this research possible. We also acknowledge the support of the Intramural Research Program at the NIMH, National Institutes of Health. We would also like to thank NetraMark for supporting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. conceptualized and designed the study. E.D.B. and C.A.Z.J. provided the clinical trial data. J.G., M.T., C.C., and P.L. performed the data analysis and generated the results. L.P. and L.A. supplied clinical expertise and interpretation. J.G., B.Q., and L.P. drafted the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.G., B.Q., M.T., C.C., and P.L. are employed by NetraMark Corp. J.G. declares that he owns substantial shares in NetraMark Holdings, which funded a major portion of this study. L.P. and L.A. are also shareholders in this company. C.A.Z.J is listed as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression and suicidal ideation; as a co-inventor on a patent for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, (S)-dehydronorketamine, and other stereoisomeric dehydroxylated and hydroxylated metabolites of (R,S)-ketamine in the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain; and as a co-inventor on a patent application for the use of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine in the treatment of depression, anxiety, anhedonia, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder. He has assigned his patent rights to the U.S. government but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government. E.D.B. and C.A.Z.J. are employees of the United States Government, and this work was completed as part of their official duties as Government employees. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government. Funding for this work was provided in part by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (IRP-NIMH-NIH; ZIAMH002927). L.P. disclosures (Last 2 years): AbbVie, USA; Acumen, USA; Aicure, USA; Alexion, Italy; BCG, Switzerland; Astra-Zeneca, Italy; Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH, Germany; EDRA-LSWR Publishing Company, Italy; GH-Pharma, Ireland; GLG-Institute, USA; Immunogen, USA; Johnson & Johnson USA; LB-Pharmaceuticals, USA; Magdalena BioSciences, USA; MSD, Italy; Sanofi-Aventis-Genzyme, France and USA; Lundbeck, Denmark and Italy; NapoPharma, USA and EU; NetraMark, Canada; Pfizer Global, USA; Relmada Therapeutics, USA; Takeda, USA. Shares/Options: Relmada, NetraMark.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geraci, J., Qorri, B., Tsay, M. et al. Explainable AI-driven precision clinical trial enrichment: demonstration of the NetraAI platform with a phase II depression trial. npj Digit. Med. 8, 749 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02143-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02143-7