Abstract

Despite their growing use in medicine, large language models (LLMs) demonstrate limited diagnostic reasoning. We evaluated a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps (Initial Diagnosis → Verification → Final Diagnosis) on 589 MedQA-USMLE and 300 NEJM cases using GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3. Each case was sampled five times and evaluated by blinded board-certified doctors. After verification of the initial diagnosis, the final diagnosis achieved up to 5.2% higher accuracy, 16.0% lower uncertainty, and 23.3% greater consistency. Among three reasoning errors, the reasoning procedure of the final diagnosis showed the largest reduction in incorrect medical knowledge (63.0%). Compared with Chain-of-Thought, the framework yielded improvements of up to 4.0% in accuracy, 4.9% reductions in uncertainty, and 11.0% increases in consistency. These results suggest that the two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps may contribute to improved diagnostic reasoning, as observed on these two datasets under experimental conditions. More datasets and models will be needed to evaluate performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

LLMs have gained increasing adoption in the medical field due to their capabilities in natural language understanding and integration of medical knowledge1,2. As model architectures scale and medical pretraining data are further refined, their performance on various clinical tasks has progressively improved3,4. Beyond answering structured questions and interpreting clinical guidelines, recent studies suggest that LLMs also demonstrate emerging diagnostic reasoning abilities, indicating their potential in medical diagnostic tasks5,6,7,8.

Despite these advancements, current LLMs still face certain limitations in medical diagnostic applications. The diagnostic accuracy of LLMs remains lower than that of doctors9,10,11. For the same medical case, LLMs can produce multiple inconsistent diagnostic conclusions11,12,13. Diagnostic tasks demand definitive conclusions, yet LLMs occasionally provide uncertain results, which does not fully meet the requirements of medical diagnostic settings7,14. Furthermore, LLMs may generate hallucinations in medical contexts, producing information that lacks factual grounding and compromises their reliability in such applications15,16,17. Consequently, improving the medical diagnostic reasoning capabilities of LLMs to better assist doctors in addressing diagnostic challenges has become a critical issue requiring resolution.

In diagnostic reasoning, a diagnosis is rarely finalized immediately after it is first made. Doctors typically generate an initial diagnosis and then verify it by reviewing patient information, consulting clinical guidelines, and considering differential diagnoses before confirmation18,19,20. This structured verification process is widely recognized as important for minimizing diagnostic errors. However, current prompting strategies for LLMs, such as Chain-of-Thought (CoT), have improved reasoning performance in diagnostic tasks but typically operate as a single-pass process and generally lack an explicit verification stage21,22,23,24,25.

Several prompting strategies have been proposed that introduce additional reasoning or verification elements beyond the standard CoT approach. These include Tree-of-Thoughts (ToT)26,27,28, Self-Consistency (SC)29,30,31, Self-Refine (SR)32,33,34, and Chain-of-Verification(CoV)35,36. These strategies have been mainly applied to general reasoning or mathematical tasks. They usually do not execute verification as a clearly separated step, and verification is typically implicit or blended into the reasoning process. CoV adds a verification phase, but because the verification questions are model-generated, they may misalign with the focal concerns of diagnostic reasoning, resulting in inconsistent coverage.

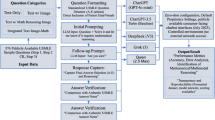

Building on these strategies and patterns inspired by diagnostic review processes, we propose a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification step. The framework separates reasoning into two stages: an Initial Diagnosis stage, in which the model generates a preliminary conclusion using CoT prompting, followed by a Verification stage that validates case details, checks consistency with diagnostic criteria, and considers differential diagnoses before producing the Final Diagnosis. We designed four verification strategies: Stepwise Verification(SV), Knowledge-Augmented Verification (KV), Differential Verification (DV), and Hybrid Verification (HV). Their verification steps and design rationale are summarized in Table 1, and we evaluated them on two datasets and two LLMs, with blinded assessments conducted by doctors.

Results

Evaluation Within Each Verification Strategy: Initial vs. Final Diagnosis

Accuracy

We compared the diagnostic accuracy of the initial and final diagnoses within each of the four verification strategies (SV, KV, DV, HV). Accuracy was defined as the proportion of responses assigned a score of 1 or 2, out of the total number of responses. Statistical differences between initial and final diagnoses were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

On the MedQA-USMLE (MedQA) dataset, GPT-4o had higher accuracy in SV (77.33% vs. 79.96%, p < 0.001), KV (78.39% vs. 80.11%, p < 0.001), and DV (77.75% vs. 79.37%, p = 0.001). For DeepSeek-V3, accuracy was higher in SV (74.18% vs. 75.75%, p < 0.001) and HV (73.23% vs. 73.79%, p = 0.015). No other comparisons were statistically significant.

On the NEJM Case Records (NEJM) dataset, GPT-4o had higher accuracy across all four strategies: SV (35.40% vs. 39.93%, p < 0.001), KV (37.53% vs. 40.53%, p < 0.001), DV (36.13% vs. 41.33%, p < 0.001), and HV (38.13% vs. 40.07%, p = 0.004). For DeepSeek-V3, accuracy also increased in all strategies: SV (43.40% vs. 46.87%, p < 0.001), KV (44.33% vs. 45.67%, p = 0.009), DV (44.00% vs. 45.87%, p < 0.001), and HV (43.53% vs. 45.13%, p = 0.011). Full results are presented in Table 2.

Uncertainty

We compared the uncertainty of initial and final responses within each of the four verification strategies (SV, KV, DV, HV). Uncertainty was defined as the proportion of responses scored 3, indicating that the model’s answer was uncertain. For each strategy, we calculated the overall uncertainty rate as uncertain responses divided by total valid responses. Differences between initial and final uncertainty were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

On the MedQA dataset, GPT-4o had lower uncertainty in SV (5.51% vs. 2.32%, p < 0.001), KV (4.35% vs. 2.11%, p < 0.001), DV (4.74% vs. 0.56%, p < 0.001), and HV (2.77% vs. 1.51%, p < 0.001). For DeepSeek-V3, uncertainty was also lower in SV (3.75% vs. 2.18%, p < 0.001), KV (4.21% vs. 3.19%, p < 0.001), DV (3.05% vs. 1.19%, p < 0.001), and HV (3.02% vs. 2.46%, p = 0.002).

On the NEJM dataset, GPT-4o had reduced uncertainty in SV (21.87% vs. 9.60%, p < 0.001), KV (14.93% vs. 6.47%, p < 0.001), DV (18.67% vs. 2.67%, p < 0.001), and HV (9.33% vs. 5.13%, p < 0.001). For DeepSeek-V3, all four strategies also had reduced uncertainty: SV (8.13% vs. 3.40%, p < 0.001), KV (4.33% vs. 2.13%, p < 0.001), DV (4.67% vs. 0.87%, p < 0.001), and HV (4.73% vs. 2.87%, p < 0.001). Full results are presented in Table 3.

We also analyzed how uncertain responses (scored 3) in the initial diagnosis transitioned to other categories—incorrect (score 0), partially correct (score 1), or correct (score 2)—in the final diagnosis for each verification strategy. Full results are presented in Table 4.

Consistency

We compared the consistency of initial and final responses within each of the four verification strategies (SV, KV, DV, HV). Consistency was defined as the proportion of cases where all five responses had the same score. Differences were analyzed using the McNemar test.

On the MedQA dataset, GPT-4o had higher consistency in KV (74.74% vs. 77.89%, p = 0.001) and DV (74.56% vs. 79.82%, p < 0.001). No significant difference was found in SV or HV. For DeepSeek-V3, consistency did not significantly change in any strategy.

On the NEJM dataset, GPT-4o had higher consistency in all four strategies: SV (53.00% vs. 66.00%, p < 0.001), KV (60.00% vs. 66.67%, p = 0.002), DV (53.00% vs. 76.33%, p < 0.001), and HV (63.00% vs. 71.00%, p = 0.001). For DeepSeek-V3, higher consistency was observed in SV (56.33% vs. 64.33%, p < 0.001), KV (64.67% vs. 70.00%, p = 0.007), and DV (66.33% vs. 71.67%, p = 0.002). No significant difference was found in HV. Full results are presented in Table 5.

Reasoning Process Evaluation

We compared the reasoning process between the initial and final responses within each of the four verification strategies (SV, KV, DV, HV). For each strategy, 100 cases were randomly sampled in which the initial diagnosis was scored 0 (incorrect) or 3 (uncertain). Both initial and final responses were assessed for hallucination type I (H1), hallucination type II (H2), and reasoning errors. Proportions were compared using the McNemar test.

On the MedQA dataset using GPT-4o, the proportion of H1 increased in HV (11.00% vs. 27.00%, p = 0.002) and decreased in KV (19.00% vs. 4.00%, p = 0.001). H2 was reduced across all four strategies: SV (90.00% vs. 44.00%, p < 0.001), KV (91.00% vs. 44.00%, p < 0.001), DV (86.00% vs. 39.00%, p < 0.001), and HV (94.00% vs. 63.00%, p < 0.001). Reasoning errors decreased in SV (83.00% vs. 66.00%, p < 0.001) and DV (89.00% vs. 77.00%, p = 0.004). No other differences were statistically significant.

On the MedQA dataset using DeepSeek-V3, H1 decreased in SV (21.00% vs. 4.00%, p < 0.001) and HV (37.00% vs. 22.00%, p = 0.003). H2 was reduced in all strategies: SV (92.00% vs. 65.00%, p < 0.001), KV (96.00% vs. 42.00%, p < 0.001), DV (97.00% vs. 69.00%, p < 0.001), and HV (87.00% vs. 54.00%, p < 0.001). Reasoning errors were also reduced in all strategies: SV (98.00% vs. 89.00%, p = 0.004), KV (99.00% vs. 93.00%, p = 0.041), DV (99.00% vs. 90.00%, p = 0.004), and HV (100.00% vs. 91.00%, p = 0.004). No other differences were statistically significant.

On the NEJM dataset using GPT-4o, H1 decreased in SV (22.00% vs. 4.00%, p < 0.001) and HV (14.00% vs. 7.00%, p = 0.035). H2 was reduced in all strategies: SV (91.00% vs. 36.00%, p < 0.001), KV (91.00% vs. 45.00%, p < 0.001), DV (98.00% vs. 51.00%, p < 0.001), and HV (99.00% vs. 39.00%, p < 0.001). Reasoning errors decreased in SV (99.00% vs. 93.00%, p = 0.031), KV (100.00% vs. 93.00%, p = 0.016), and DV (100.00% vs. 87.00%, p < 0.001). No other differences were statistically significant.

On the NEJM dataset using DeepSeek-V3, H1 decreased in all strategies: SV (37.00% vs. 6.00%, p < 0.001), KV (35.00% vs. 1.00%, p < 0.001), DV (29.00% vs. 1.00%, p < 0.001), and HV (40.00% vs. 7.00%, p < 0.001). H2 was also reduced across all strategies: SV (96.00% vs. 44.00%, p < 0.001), KV (98.00% vs. 48.00%, p < 0.001), DV (96.00% vs. 33.00%, p < 0.001), and HV (93.00% vs. 53.00%, p < 0.001). Reasoning errors declined in SV (100.00% vs. 92.00%, p = 0.008), KV (100.00% vs. 91.00%, p = 0.004), and DV (100.00% vs. 94.00%, p = 0.041). No other differences were statistically significant. Full data are presented in Table 6.

We also calculated the proportion of cases in which an initial diagnosis rated 0 was revised to a rating of 1 or 2 in the final diagnosis. This analysis reflects the frequency with which the verification process resulted in a partial or complete correction of an initially incorrect response. Detailed values for each strategy and model are presented in Table 4.

Comparison of Final Diagnoses: Verification Strategies vs. CoT

Accuracy

We compared the final diagnosis accuracy between each verification strategy and CoT. On the MedQA dataset, for GPT-4o, KV had higher accuracy than CoT (80.11% vs. 78.60%, p = 0.035). For DeepSeek-V3, both SV (75.75% vs. 73.02%, p = 0.001) and DV (74.84% vs. 73.02%, p = 0.033) had higher accuracy than CoT. On the NEJM dataset, for DeepSeek-V3, all four verification strategies—SV (46.87% vs. 42.87%, p < 0.001), KV (45.67% vs. 42.87%, p = 0.012), DV (45.87% vs. 42.87%, p = 0.006), and HV (45.13% vs. 42.87%, p = 0.020)—had higher accuracy than CoT. No other differences were statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05). Full results are presented in Table 7.

Uncertainty

We compared the final diagnosis uncertainty between each verification strategy and CoT. On the MedQA dataset, for GPT-4o, DV had a lower uncertainty rate than CoT (0.56% vs. 1.96%, p < 0.001). For DeepSeek-V3, KV had a higher uncertainty rate than CoT (3.19% vs. 1.75%, p < 0.001). On the NEJM dataset, for GPT-4o, DV (2.67% vs. 7.53%, p < 0.001) and HV (5.13% vs. 7.53%, p = 0.022) had lower uncertainty than CoT. For DeepSeek-V3, both KV (2.13% vs. 3.40%, p = 0.021) and DV (0.87% vs. 3.40%, p < 0.001) had lower uncertainty. No other differences were statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05). Full results are presented in Table 7.

Consistency

We compared the final diagnosis consistency between each verification strategy and CoT. On the NEJM dataset, GPT-4o had higher consistency in DV than CoT (76.33% vs. 65.33%, p = 0.002). For DeepSeek-V3, consistency was higher in KV (70.00% vs. 63.00%, p = 0.011) and DV (71.67% vs. 63.00%, p = 0.001). On the MedQA dataset, DeepSeek-V3 had lower consistency in HV than CoT (68.07% vs. 72.63%, p = 0.034). No other comparisons were statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05). Full results are presented in Table 7.

Additional Experiment 1: Accuracy, Uncertainty, and Consistency in Alternative Strategies and Models

To further evaluate prompting strategies, we tested four previously proposed methods (SC,ToT, SR, and CoV) along with two additional models (Gemini-2.5-flash and Qwen3). Thirty questions were randomly sampled from each of the MedQA and NEJM datasets, and performance was assessed using the same accuracy, uncertainty, and consistency metrics and statistical tests as in the main analysis.

Across the sampled questions, none of the four alternative strategies (SC, ToT, SR, CoV) improved accuracy compared with CoT. In some cases, performance was lower; for example, on the NEJM dataset using Gemini-2.5-flash, ToT reached 45.33% accuracy compared with 60.67% for CoT (p = 0.023).

Accuracy differences (ΔAccuracy) between these strategies and CoT across models and datasets are shown in Fig. 1. No notable differences in uncertainty or consistency were observed among these strategies. The SHV strategy also showed no differences from the original HV in any metric. Full results are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Full prompt templates for five strategies (CoT, ToT, SR, SC, CoV) are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Note: SV, Stepwise Verification; KV, Knowledge-Augmented Verification; DV, Differential Verification; HV, Hybrid Verification; SC, Self-Consistency; ToT, Tree-of-Thoughts; SR, Self-Refine; CoV, Chain-of-Verification; CoT, Chain-of-Thought. Accuracy (%): proportion of responses scored 1 or 2. ΔAccuracy (%): accuracy of each prompting strategy’s final diagnosis minus the accuracy of CoT within the same model–dataset condition.

We compared diagnostic accuracy, uncertainty, and consistency between temperature settings of 0 and 0.6 across both LLMs and the two medical datasets. The analyses showed no significant differences between Temperature 0 and Temperature 0.6 in any of the evaluated metrics. Full results are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Additional Experiment 2: Token Length, Redundancy, and Component count Effects on HV

To investigate why HV’s final accuracy was lower than its initial accuracy on MedQA–GPT-4o (79.47% vs. 78.60%; p = 0.058), we randomly selected 50 MedQA questions and obtained three independent GPT-4o answers per question. We evaluated eight strategies: the original versions of SV, KV, DV, and HV; SHV (an HV variant with redundant instructions removed); and three two-component hybrids: SKV (SV + KV), SDV (SV + DV), and KDV (KV + DV). For each of these eight strategies, we also constructed a Short version by substantially reducing prompt tokens. In the original version of the prompts, each round was submitted to the LLM as an independent prompt, resulting in relatively long prompt token lengths. To reduce the overall token usage, the short version maintained the same content but merged rounds 1–3 into a single prompt for the initial diagnosis stage and combined round 4 and subsequent rounds into another prompt for the final diagnosis stage. This modification substantially decreased the total prompt token length while preserving the semantic integrity of the original instructions. Scoring and statistical analysis were performed as before, and we compared ΔAccuracy (final minus initial accuracy) for all strategies. Full prompt templates for these strategies are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

Token length

We compared the difference between final and initial accuracy for the Original and Short versions of each strategy. Only the HV Original version had ΔAccuracy < 0 (66.00% vs 63.33%, p = 0.313), whereas the Short-HV version had ΔAccuracy > 0 (64.67% vs 65.33%, p = 0.906).No Initial-to-Final change reached statistical significance for any strategy (all p > 0.05), and ΔAccuracy did not differ significantly between the Short and Original versions for any strategy (all p > 0.05). Full results are provided in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Redundancy

SHV showed ΔAccuracy = 0 (68.00% vs 68.00%; p = 0.313). Neither HV nor SHV exhibited a significant Initial-to-Final change (both p > 0.05). The ΔAccuracy also did not differ significantly between SHV and HV (p = 0.359). Full results are provided in Supplementary Table 6.

Component count

The two-component hybrids (SKV, SDV, KDV) each had ΔAccuracy > 0, but none showed a significant Initial-to-Final change (all p > 0.05). In comparisons with HV, ΔAccuracy did not differ significantly for SKV, SDV, or KDV (all p > 0.05). Full results are provided in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 2.

Discussion

We found that the impact of individual verification strategies varied across models. For example, SV improved diagnostic accuracy in DeepSeek-V3 but did not produce similar improvements in GPT-4o or other models. We evaluated a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps. Compared with single-stage reasoning, this framework showed differences in performance across several evaluation metrics. Within this framework, verification strategies had varying effects depending on the model, and the design space remains broad, encompassing different structures and levels of complexity. Given this variability, identifying a single optimal strategy is challenging. In the MedQA–GPT-4o combination, we observed a trend: with increasing prompt token length and more components combined, the initial-to-final accuracy gain tended to be smaller. HV, the longest and most component-rich variant, was the only case showing a decrease from initial to final accuracy. Although these differences were not statistically significant, the trend may suggest that longer prompts and more complex hybrids are not necessarily associated with improved accuracy in the MedQA–GPT-4o combination. Additional studies are required to substantiate these findings.

While the two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps reduced the proportion of uncertain responses, further analysis indicated that this reduction was not always beneficial. In some cases, models changed uncertain responses into incorrect ones (score 3 to 0) rather than improving toward partially correct or correct answers. This phenomenon was particularly evident in the NEJM dataset, where the proportion of 3 to 0 transitions was higher. These findings indicate that a decrease in uncertainty may, in certain situations, correspond more to increased confidence than to improved diagnostic reasoning, which should be considered in clinical applications.

Strategies aimed at improving reasoning reliability include multi-path exploration methods, such as SC and ToT, as well as strategies incorporating verification elements, such as SR and CoV26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. In our experiments with a limited sample size, their performance was broadly comparable to CoT prompting. These strategies generally do not implement verification as a distinct and explicitly defined step: SC and ToT expand reasoning paths without a dedicated verification stage, while SR and CoV embed model-generated questions within the reasoning chain itself. These questions are often model-generated and unpredictable, which may omit key aspects, introduce irrelevant content, and lack clearly defined verification objectives. In our work, we designed a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps inspired by diagnostic review practices, which introduces a clearly defined verification stage between the initial and final diagnosis.The predefined verification content is structured but flexible, allowing for different strategies with clear objectives, such as reducing omissions, improving consistency with guideline criteria, or systematically comparing alternative diagnoses. In addition, while most prior strategies have been developed for general reasoning domains such as mathematics or logic, where the focus is on logical correctness, our framework draws conceptual inspiration from diagnostic review procedures, adapting the idea of structured verification to diagnostic reasoning tasks.

Hallucination remains a key challenge in clinical applications, as incorrect or fabricated details can compromise patient safety. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has been explored to improve factual reliability by grounding outputs in external knowledge sources, though its effectiveness depends on the quality and relevance of the retrieved conten6,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Other approaches, such as uncertainty-based detection and multi-agent validation, can help identify or cross-check potentially unreliable information but may not fully prevent hallucinations and can introduce additional complexity17,44,45,46. Our framework draws on patterns common in clinical diagnostic review, including steps analogous to consulting medical references. At present, it operates primarily on the model’s internal knowledge. Whether integrating such verification processes with external reference resources could further enhance performance remains an open question for future research.

We also observed that diagnostic accuracy declined as case complexity increased, consistent with previous findings47,48. This likely reflects the greater complexity of NEJM cases, which require integrating rich clinical narratives with diagnostic findings, in contrast to the more focused questions in MedQA. Even experienced doctors may not achieve perfect accuracy on such complex cases49,50,51. These results suggest that LLMs, even when using prompting strategies designed to improve output quality, may be more appropriate as a complement to human judgment rather than as independent decision-makers. In practice, their main value may lie in offering additional information or alternative perspectives, while final decisions remain with doctors. Safe clinical integration may involve doctor review of model outputs in complex or high-risk scenarios and access to intermediate reasoning steps for verification52,53,54. Future work could explore prospective clinical studies in real-world settings and the development of regulatory guidance addressing validation, oversight, transparency, and accountability.

This study has several limitations. First, the evaluation used two publicly available datasets (MedQA and NEJM Case Records). These datasets have been commonly used in LLM diagnostic reasoning research, but there is a possibility that the models had partial exposure to their content during pretraining. Such exposure could potentially influence absolute performance estimates; however, because all prompting strategies were evaluated under the same conditions, potential effects on relative performance comparisons are likely to be limited.Second, both datasets have limited scope. MedQA consists of standardized exam-style questions, whereas NEJM cases, while clinically rich, are curated and may not fully reflect the complexity of real-world diagnostic practice.Third, the study focused on English-language tasks and two LLMs (GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3). Although a small-scale supplementary evaluation was conducted with two additional models, the limited sample size may not fully capture potential differences across models. Extending the evaluation to other languages, additional clinical domains, private clinical datasets, and a broader range of models would help assess robustness and generalizability. Finally, while verification-based prompting was associated with reductions in uncertainty and hallucinations in several settings, accuracy gains were modest, and in some cases reduced uncertainty coincided with incorrect answers, suggesting possible overconfidence. Future work could explore whether combining verification with other approaches, such as integration with external knowledge sources, may further improve diagnostic reliability.

This study evaluated a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps (Initial Diagnosis → Verification → Final Diagnosis) on two diagnostic datasets under experimental conditions. The framework was associated with reductions in uncertainty, improvements in consistency, and decreases in hallucinations and reasoning errors, although accuracy gains were modest and varied across settings. These findings suggest that a two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps may provide value for diagnostic reasoning tasks, as observed in two datasets and two models, though further research with additional datasets, models, and evaluation settings will be needed to examine robustness and applicability.

Methods

Experiment design

A total of 589 randomly selected questions from the MedQA dataset and 300 randomly selected cases from the NEJM Case Records were included. 19 MedQA cases without explicit diagnostic conclusions were excluded. As shown in Fig. 2, four verification strategies (SV, KV, DV, HV) in two-stage prompting framework and the CoT strategy were applied to GPT-4o and DeepSeek-V3. Each prompt was executed independently five times per model and strategy, generating 43,500 diagnostic responses with associated reasoning chains. We compared initial and final diagnoses within each verification strategy, as well as final diagnoses from the four verification strategies with those from CoT, in terms of accuracy, uncertainty, consistency, and hallucinations and reasoning errors during the reasoning process.

Datasets

We used two datasets, MedQA and NEJM Case Records, to evaluate the performance of prompting strategies on diagnostic tasks of different complexity. MedQA consists of standardized medical exam questions with broad topical coverage and high structural consistency, and has often been used in previous studies to assess LLM diagnostic reasoning in exam-style settings3,7,51,55. From this dataset, we randomly selected 589 questions whose type is labeled as step 2 and step 3 in the dataset, as these questions involve multi-step reasoning processes and can be used to evaluate the diagnostic reasoning performance of large language models. Multiple-choice options were removed to convert them into open-ended tasks suitable for evaluating diagnostic reasoning.

In contrast, NEJM Case Records contains detailed case reports characterized by unstructured narratives, dispersed clinical information, and complex diagnostic reasoning requirements. This dataset has been used in recent studies to examine LLM performance on case-based diagnostic tasks51,52. From NEJM, we randomly selected 300 representative cases with definitive diagnoses. For each case, diagnostic content was retained, while expert discussion and final diagnoses were removed, and an open-ended diagnostic question was appended to create reasoning-focused tasks.

For both datasets, each case was tested under five prompting strategies, with each strategy executed independently five times per model.

Model configuration and LLM programming

We selected four general-purpose LLMs: GPT-4o-2024-08-06 (Endpoints: v1/chat/completions), DeepSeek-V3-0324 (Endpoints: chat/completions), gemini-2.5-flash-preview-05-20 (Endpoints: v1beta/openai/) and qwen3-235b-a22b (Endpoints: compatible-mode/v1) to conduct all experiments. For both models, the parameters were set as follows: temperature = 0.6, top_p = 0.9, and frequency_penalty = 0, presence_penalty = 0. All prompts were submitted via API, and responses containing diagnostic conclusions and reasoning chains were retrieved in JSON format. To make sure that each step in the prompts is actually responded by the LLM, we employ API to simulate a multi-turn dialog scenario, effectively guiding the model to complete all predefined reasoning steps in prompt and preventing it from skipping steps through deceptive summarization. All API-based experiments were implemented in Python 3.11.1, Openai SDK 1.8.0, Pandas 2.2.3 and Numpy 1.26.4.

Prompt design

We implemented five prompting strategies: the standard CoT and four verification-based strategies (SV, KV, DV, and HV). The design of these verification-based strategies was informed by two sources: (1) existing prompting methods that introduce additional reasoning or verification mechanisms, such as ToT, SC, SR, and CoV26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36; and (2) common diagnostic review practices, including verifying case details, checking consistency with guideline criteria, and considering differential diagnoses18,19,20.

CoT guides the model to generate a diagnostic conclusion in a single forward reasoning process without explicit verification. In contrast, all verification-based strategies adopt a two-stage reasoning structure:

(1) Initial Diagnosis, in which the model produces a preliminary diagnosis and reasoning chain using CoT-style prompting; and

(2) Verification, in which the model reviews the reasoning process of the initial diagnosis, applies the specific verification steps of the selected strategy (SV, KV, DV, or HV), and then generates the final diagnostic conclusion.

Representative examples of the full prompt templates are provided in Supplementary Table 8.

Expert evaluation and scoring criteria

The evaluation team consisted of three board-certified general practitioners, each with over 10 years of clinical experience in multi-system disease management at tertiary hospitals. All evaluators had no involvement in prompt design and were not authors of this study. Each case was independently assessed by two doctors, with discrepancies resolved through consensus discussion involving a third doctor. Evaluators were blinded to both the model identity and the prompting strategy during scoring.

The evaluation criteria were as follows:

Score 2: The diagnosis was completely correct and fully matched the correct diagnosis.

Score 1: The diagnosis was partially correct, broader than the correct diagnosis but within the same diagnostic category.

Score 0: The diagnosis was incorrect, with no apparent clinical relevance to the correct diagnosis.

Score 3: The diagnosis was uncertain, involving ambiguous or multiple competing diagnoses (e.g., “pancreatitis or appendicitis”). Representative examples for each score level are provided in Supplementary Table 9.

Reasoning process evaluation

We evaluated reasoning processes for cases where the initial diagnosis was either incorrect (score = 0) or uncertain (score = 3), as generated by two representative LLMs under the four verification prompting strategies. From each dataset (MedQA-USMLE and NEJM Case Records), 100 cases meeting these criteria were randomly selected for analysis. The evaluation process followed the same procedure as diagnostic scoring: each reasoning chain was independently reviewed by two doctors, and disagreements were resolved through adjudication by a third doctor. The evaluation consisted of two steps: (1) determining whether errors were present in the reasoning process, and (2) classifying identified errors into one of the following categories:

H1 (factually incorrect information)

Introduction of symptoms, test results, or medical facts that were absent from the case or inaccurately stated based on the case information.

H2 (incorrect medical knowledge)

Use of medical principles, mechanisms, or conclusions that conflicted with authoritative guidelines or established medical knowledge, indicating misuse or fabrication of clinical reasoning.

Reasoning errors (flawed reasoning process)

Logical inconsistencies, incorrect causal relationships, or omission of critical reasoning steps necessary to reach the diagnosis. Representative examples of each error type are provided in Supplementary Table 10.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.4.1. For accuracy and uncertainty, which were treated as discrete ordinal variables, normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test. As these data were not normally distributed, paired comparisons were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. For binary outcomes, such as consistency and reasoning-related errors, differences between paired categorical responses were assessed with McNemar’s test. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript are provided in our Supplementary Information and open access figshare (10.6084/m9.figshare.29207015). This includes all prompts, LLM responses, code, and reviewer grades.

References

Bedi, S., Jain, S. S. & Shah, N. H. Evaluating the clinical benefits of LLMs. Nat. Med. 30, 2409–2410 (2024).

Shah, N. H., Entwistle, D. & Pfeffer, M. A. Creation and adoption of large language models in medicine. JAMA 330, 866–869 (2023).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Kung, T. H. et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit. Health 2, e0000198 (2023).

Kresevic, S. et al. Optimization of hepatological clinical guidelines interpretation by large language models: a retrieval augmented generation-based framework. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 102 (2024).

Liévin, V., Hother, C. E., Motzfeldt, A. G. & Winther, O. Can large language models reason about medical questions?. Patterns 5, 100943 (2024).

Liu, X. & Liu, H. Y. et al. A generalist medical language model for disease diagnosis assistance. Nat. Med. 31, 932–942 (2025).

Kanjee, Z., Crowe, B. & Rodman, A. Accuracy of a generative artificial intelligence model in a complex diagnostic challenge. JAMA 330, 78–80 (2023).

Pagano, S. et al. Arthrosis diagnosis and treatment recommendations in clinical practice: an exploratory investigation with the generative AI model GPT-4. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 24, 61 (2023).

Mandalos, A. & Tsouris, D. Artificial versus human intelligence in the diagnostic approach of ophthalmic case scenarios: a qualitative evaluation of performance and consistency. Cureus 16, e62471 (2024).

Shao, H., Wang, F. & Xie, Z. S2AF: an action framework to self-check the understanding self-consistency of large language models. Neural Netw. 187, 107365 (2025).

Wu, S. H. et al. Collaborative enhancement of consistency and accuracy in US diagnosis of thyroid nodules using large language models. Radiology 310, e232255 (2024).

Madrid, J. et al. Performance of plug-in augmented ChatGPT and its ability to quantify uncertainty: simulation study on the German Medical Board Examination. JMIR Med. Educ. 11, e58375 (2025).

Farquhar, S., Kossen, J., Kuhn, L. & Gal, Y. Detecting hallucinations in large language models using semantic entropy. Nature 630, 625–630 (2024).

Verspoor, K. Fighting fire with fire’—using LLMs to combat LLM hallucinations. Nature 630, 569–570 (2024).

Romera-Paredes, B. et al. Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models. Nature 625, 468–475 (2024).

Koufidis, C., Manninen, K., Nieminen, J., Wohlin, M. & Silén, C. Clinical sensemaking: advancing a conceptual learning model of clinical reasoning. Med. Educ. 58, 1515–1527 (2024).

Kuhn, J. et al. Teaching medical students to apply deliberate reflection. Med. Teach. 46, 65–72 (2024).

Mamede, S. & Schmidt, H. G. Deliberate reflection and clinical reasoning: founding ideas and empirical findings. Med. Educ. 57, 76–85 (2023).

Meskó, B. Prompt engineering as an important emerging skill for medical professionals: tutorial. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e50638 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Prompt engineering in consistency and reliability with the evidence-based guideline for LLMs. NPJ Digit Med. 7, 41 (2024).

Yan, S. et al. Prompt engineering on leveraging large language models in generating response to InBasket messages. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 31, 2263–2270 (2024).

Shi, J., Li, C., Gong, T., Wang, C. & Fu, H. CoD-MIL: chain-of-diagnosis prompting multiple instance learning for whole slide image classification. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 44, 1218–1229 (2025).

Yang, H. S., Li, J., Yi, X. & Wang, F. Performance evaluation of large language models with chain-of-thought reasoning ability in clinical laboratory case interpretation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med 63, e199–e201 (2025).

Long J. Large language model guided tree-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08291 (2023).

Yao, S. et al. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 36, 11809–11822 (2023).

Mo, S. & Xin, M. Tree of uncertain thoughts reasoning for large language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 12742−12746 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Universal self-consistency for large language model generation. In Proceedings of the ICML 2024 Workshop on In-Context Learning. Available at: https://openreview.net/forum?id=LjsjHF7nAN (2024).

Taubenfeld, A. et al. Confidence improves self-consistency in llms. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 20090–20111 (ACL, 2025).

Prasad, A. Self-consistency preference optimization. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations. Available at: https://openreview.net/forum?id=jkUp3lybXf.

Madaan, A. et al. Self-refine: Iterative refinement with self-feedback[J]. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 46534–46594 (2023).

Ranaldi, L. & Freitas, A Self-refine instruction-tuning for aligning reasoning in language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2325–2347 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Revise: Learning to refine at test-time via intrinsic self-verification[J]. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.14565 (2025).

Dhuliawala, S. et al. Chain-of-verification reduces hallucination in large language models. Findings Assoc Comput Linguist: ACL 2024, 3563–3578 (2024).

He, B. et al. Retrieving, rethinking and revising: The chain-of-verification can improve retrieval augmented generation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 10371–10393 (EMNLP, 2024).

Ke, Y. H. et al. Retrieval augmented generation for 10 large language models and its generalizability in assessing medical fitness. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 187 (2025).

Wada, A. et al. Retrieval-augmented generation elevates local LLM quality in radiology contrast media consultation. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 395 (2025).

Lopez, I. et al. Clinical entity augmented retrieval for clinical information extraction. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 45 (2025).

Gaber, F. et al. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 263 (2025).

Masanneck, L., Meuth, S. G. & Pawlitzki, M. Evaluating base and retrieval augmented LLMs with document or online support for evidence based neurology. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 137 (2025).

Tayebi Arasteh, S. et al. RadioRAG: Online Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Radiology Question Answering. Radio. Artif. Intell. 7, e240476 (2025).

Zhang, G. et al. Leveraging long context in retrieval augmented language models for medical question answering. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 239 (2025).

Zhang, H., Deng, H., Ou, J. & Feng, C. Mitigating spatial hallucination in large language models for path planning via prompt engineering. Sci. Rep. 15, 8881 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 159 (2025).

Hao, G., Wu, J., Pan, Q. & Morello, R. Quantifying the uncertainty of LLM hallucination spreading in complex adaptive social networks. Sci. Rep. 14, 16375 (2024).

Savage, T., Nayak, A., Gallo, R., Rangan, E. & Chen, J. H. Diagnostic reasoning prompts reveal the potential for large language model interpretability in medicine. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 20 (2024).

McDuff, D. et al. Towards accurate differential diagnosis with large language models. Nature 642, 451–457 (2025).

Levine, D. M. et al. The diagnostic and triage accuracy of the GPT-3 artificial intelligence model: an observational study. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e555–e561 (2024).

Goh, E. et al. Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2440969 (2024).

Suh, P. S. et al. Comparing diagnostic accuracy of radiologists versus GPT-4V and Gemini Pro Vision using image inputs from diagnosis please cases. Radiology 312, e240273 (2024).

Kopka, M., von Kalckreuth, N. & Feufel, M. A. Accuracy of online symptom assessment applications, large language models, and laypeople for self-triage decisions. NPJ Digit. Med. 8, 178 (2025).

Harrer, S. Attention is not all you need: the complicated case of ethically using large language models in healthcare and medicine. EBioMedicine 90, 104512 (2023).

Iqbal, U. et al. Impact of large language model (ChatGPT) in healthcare: an umbrella review and evidence synthesis. J. Biomed. Sci. 32, 45 (2025).

Singhal, K. et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 31, 943–950 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the doctors who participated in the evaluation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ming Shao took primary responsibility for the study design and the finalization of the manuscript. Haichun Zhang contributed by providing critical research directions, developing the program in accordance with the designed experiment, conducting statistical and visual data processing, and revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, M., Zhang, H. Two-stage prompting framework with predefined verification steps for evaluating diagnostic reasoning tasks on two datasets. npj Digit. Med. 8, 782 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02146-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02146-4