Abstract

Ultrasound data is relatively under-utilized in machine learning applied to medical imaging research when compared to other imaging modalities. Towards rectifying this, this paper (and the associated webpage) catalogs and assesses the usability of publicly available ultrasound datasets and models. Datasets were categorized and ranked using an original dataset quality score, SonoDQS. The models were scored using our model quality score, SonoMQS. We identified 72 public ultrasound datasets covering different anatomies and collected in different parts of the world. We identified 56 open-source models trained on ultrasound data. Most open-source models were trained on datasets that are or were made publicly available. A plurality of the datasets are of similar quality, corresponding to bronze (fifth tier) in the SonoDQS ranking. There are a few publicly available datasets of fetal content (5) and prostate anatomy (4) in spite of the wide use of ultrasound in these clinical areas, acknowledging a notable gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrasound is relatively underrepresented in research in the machine learning applied to medical imaging space when compared to other modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and X-ray computer tomography (CT). By way of illustration, at a leading international conference in medical image analysis in 2023 (Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Interventions, MICCAI 2023)1, only 51 papers were classed under the ultrasound modality topic. On the other hand, there were 185 papers and 126 papers that were classed under the MRI and CT topics, respectively. This observation holds true for earlier years as well. In MICCAI 2022, the equivalent figures are 43 ultrasound, 159 MRI and 82 CT papers2 and in MICCAI 2021, the figures are 32 ultrasound, 128 MRI, and 95 CT papers3. This holds despite the wide variety of tasks performed on ultrasound imaging data, including image classification4,5,6, image captioning7,8,9,10, video captioning11,12, representation learning13,14,15, and segmentation16,17.

In this paper, we report on a study to collate, analyze and score publicly available ultrasound datasets and models. Our goal was to identify open-source resources available for ultrasound imaging research, including machine learning-based analysis and sonography data science, to encourage the scientific community to answer more research questions pertaining to clinical ultrasound.

There are several related reviews on public datasets for other medical imaging modalities and clinical imaging areas. Khan et al.18 reviews publicly available ophthalmological imaging datasets and scores them based on how much information on them is made available. Magudia et al.19 discuss the challenges of assembling large medical datasets and share best practices on cohort selection, data retrieval, storage, and failure handling. Kohli et al.20 highlight the need for improved collection, annotation, and reuse of medical imaging data, as well as the development of best practices and standards. These works19,20 suggest there is a need to standardize how datasets are described and what information to track when they are collected and prepared. In this paper, we describe the methods used in our search for public ultrasound datasets and open-source models and detail what we have found available and any interesting points to note relating to the public resources.

To build AI-powered clinical solutions that generalize well, researchers need access to datasets on which to train their proposed models on. Ideally, they would train on a variety of datasets that have different characteristics, such as the country of origin, the type of scanning device used, and the time-frame during which the data was collected.

AI-powered clinical solutions that could be of benefit to current medical practice can vary. One way, for example, would be through solutions that could allow for assistive tools that speed up the scanning process (e.g., automatic segmentation of anatomies of interest), leading to direct benefits to clinician productivity, allowing medical facilities to serve more people in the same window of time.

Results

Findings of the dataset search

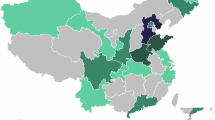

The results of the dataset search suggest that there are a number of different anatomies represented in open-source ultrasound datasets, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. It is interesting to note from Table 1 that our search implies that the popularity of using ultrasound imaging in clinical practice or clinical research does not translate to the availability of public datasets. An example is the prostate, where only four publicly available datasets were identified. Fetus and fetal related anatomies are among the less prevalent anatomies in public US datasets, as shown in Fig. 2. In Figs. 3 and 4, we summarize where and when publicly available US datasets are being acquired and collected, respectively. These are but two ways to visualize some of the characteristics of the datasets.

Left shows male anatomy, right female anatomy. The colors orange, green, black, blue, red, violet, pink, yellow, and peach represent parts of the circulatory system, the brain, the thyroid gland, parts of the digestive system, the kidneys, the lungs and the breasts, lymph nodes, the reproductive system, and the musculoskeletal system, respectively. The fetus is not shown in the anatomy diagrams. Plot was made using the pyanatomogram library180. Anatomogram silhouettes © EMBL-EBI Expression Atlas, CC BY 4.0181.

The numbers shown are the number of datasets that contain data samples of this anatomy group. Some datasets contain multiple anatomy groups. The plot was made using the python library Matplotlib182.

Note that datasets that do not mention where the data is acquired are not included. This map, plotted using the python library plotly183, is provided for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect any legal or political stances. Basemap: Natural Earth (Public Domain).

Please note this only includes datasets that mention ranges of acquisition. The plot was made using the python library Matplotlib182.

In our proposed SonoDQS dataset quality score, there are seven possible tiers or ranks: diamond, platinum, gold, silver, bronze, steel, and unrated. A plurality (40.32% of the datasets are of similar quality, corresponding to bronze (fifth tier out of seven tiers) in the SonoDQS ranking. The classification of the datasets according to the SonoDQS ranks can be found in the pie chart in Fig. 5. Some dataset characteristics are considered to be more important when showing how complete a dataset is Fig. 6 shows these characteristics, and it is pleasing to note that most of these characteristics are shared and made available with their corresponding datasets.

The plot was made using the python library Matplotlib182.

100% means this characteristic or information is always shared with datasets. The plot was made using the python library Matplotlib182.

Discussion

We identified 72 public ultrasound datasets covering different anatomies and coming from different parts of the world. We observed that anatomies such as fetal content and prostate did not have many public datasets as one might have expected given the wide spread use of ultrasound in these clinical ultrasound areas. We identified 56 open-source models trained on ultrasound data. It is noteworthy that when open-sourcing models, researchers share more comprehensive information about the models than they do when sharing the dataset.

Most open-source models 30/56 actually do not publicly make available their model weights; however, they still met our definition of open source because the code, the dataset, and the training details are available.

We recognize that the boundary thresholds set for SonoDQS ranks were set empirically and could undergo refinement in the future. The ranks, nonetheless, are useful as a guide to help in the selection of the datasets to consider and a way to look at the quality of ultrasound datasets as whole. A researcher is likely to use the dataset characteristics when deciding which exact datasets are useful for their purpose. The fact that there are few open-sourced fetal ultrasound datasets and prostate ultrasound datasets is particularly noteworthy. The published literature in this area is primarily on private data.

The proposed SonoDQS and SonoMQS scores fundamentally are meant to encourage the consistent sharing of comprehensive information on public ultrasound datasets and open-source models in a standardized manner. This consistent sharing of relevant comprehensive information in a standardized manner is important to clinical decision making and ultrasound diagnostics. If, for example, a hospital is interested in using a readily-available model but would want one trained on data from their geographic region or trained on data acquired with equipment similar to what they have in-house. Being open about such details ensures greater transparency which is important in the clinical space but also is reassuring to potential users because they know more about the datasets and the models. Potentially, being more open about these details might help slightly with clinical translation.

We acknowledge the existence of limitations with our work. In terms of datasets, we only focus on publicly available datasets disregarding in our analyses and reporting private datasets that are publicly known to exist but are not available. The number of SonoDQS ranks is somewhat subjective (diamond, platinum, etc.) despite going through an iterative process. They exist to make it easy to quickly compare the SonoDQS scores of a large number of datasets.

This paper catalogs open sourced ultrasound datasets and ranks them based on how open they are and how much information has been shared about the data. Open source models are also reported and ranked in terms of how open-sourced they have been made. For the reporting of both the public datasets and the open-sourced models, the cut-off date was September 2025.

Methods

Identification of publicly available ultrasound imaging datasets

Team members searched for information on datasets and models starting in April 2024 and ending in September 2025 The search strategies are described next. Each team member was tasked with searching and identifying publicly available ultrasound datasets. This was achieved in a number of ways, such as through search engines (most typically Google search21), the website Paperswithcode22, WeChat search23, social media, blogs, Google Scholar24, ChatGPT25 and its ability to conduct searches through Bing26, survey papers27, and Google Dataset28. The search terms that were used to identify and locate open-source ultrasound imaging datasets include “ultrasound imaging”, “public ultrasound datasets”, and “ultrasound”.

One important characteristic is dataset access. A dataset may be available immediately as an open access dataset or available on request which may require the signing of an agreement before the dataset can be downloaded. This is similar to what was done by ref. 18 for opthalmological datasets who also noted whether publicly available opthalmological datasets were open-access or available on request.

There are several dataset characteristics that we attempted to identify. We based these on the checklist used by organizers of MICCAI 2024 Challenges29. This collected information goes into tables, the summary table and the detailed table. The 13 more important dataset characteristics of interest: (1) dataset name, (2) link to dataset, (3) anatomy, (4) scanning mode, (5), multi-modal (text+image), (6) total dataset size, (7) training, validation, and test set sizes, (8) task category, (9) geography of study, (10) year(s) of acquisition, (11) other imaging and metadata, (12) single machine or multiple machines (single center or multiple centers), and (13) open access (OA) or available on request (AR). Please find the interactive table on display on the webpage interface.

There are 20 further characteristics that are relatively less important but are still collected and considered. These characteristics are: (1) device(s) used to acquire data (US machine type and transducer), (2) data acquisition protocols, (3) center or institute collecting or providing data, (4) characteristics of the data acquirers (such as their experience level), (5) other characteristics of the training, validation, and testing datasets (such as the data distribution), (6) what is considered a single data sample, (7) number of operators or sonographers, (8) how annotations are made (manually or automatically) and by how many annotators, (9) the instructions given to the annotators, (10) annotation description, (11) how were annotations merged together if required, (12) dataset application cases (such as education), (13) ethics approval statement, (14) data usage agreement, (15) challenge if dataset is associated with a challenge, (16) imaging modalities and techniques used, (17) context information relevant to the spatial or spatio-temporal data, (18) patients’ (or subjects’) details, such as gender, age, and medical history, (19) Doppler imaging (Y/N), and (20) B-mode imaging (Y/N).

For ease of readability of this paper, a reduced version of the table is included as Table 1. This table has four columns: (1) the name of the dataset, (2) the anatomies involved, (3) the total size of the dataset, and (4) whether the dataset is open access or available on request. The full table webpage has been made uploaded as additional material as HTML files.

Another characteristic of note is the scanning mode. We have specified five possible scanning modes: (1) 2D ultrasound images from freehand scanning potentially containing both standard and non-standard planes for the scanned anatomy, (2) 2D ultrasound images meant solely for diagnostics and measurements typically containing only standard planes for the scanned anatomy, (3) 2D+t content (i.e. ultrasound videos), (4) 3D ultrasound images (there is different physics involved and different probes used compared to 2D imaging), and (5) 3D ultrasound images reconstructed from 2D ultrasound images.

Dataset characteristics were extracted from the source material by the team member that found the dataset during the data search stage. Subsequently, a second team member verified and corrected, if necessary, the characteristics. This cross-referencing was done, as a quality assurance step, to ensure the integrity of the content in the paper, the webpage, and their associated tables.

Identification of open-source ultrasound imaging models

On 7 July 2024, in a lecture titled “Collaborate as a Community: Innovations and Trends in Open-Source AI”, presented at the Machine Learning for Health & Bio track of the Oxford Machine Learning Summer School (Oxford, UK), Vincent Moens described four elements of a trained model that relate to its “openness”: (1) the code, (2) the training data, (3) the model weights, and (4) the training procedure details (unpublished). A fully open model will provide details on all four elements, and a closed model provides no detail. Models may also have different degrees of openness between these two extremes. While a fully open model is desirable, a partially open model may still be very useful for community research and allow for model comparisons.

Any deep learning models trained on ultrasound data were eligible for inclusion. The search was conducted in two stages. First, we performed a literature search to identify studies related to ultrasound data analysis published since 2022. This search focused on top journals and conferences in medical imaging, including IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, Medical Image Analysis, and the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). We used keywords describing various types of ultrasound, including ‘ultrasound’, ‘US’, ‘sonography’, and ‘sonographer’. This returned 112 IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging papers, 170 Medical Image Analysis papers, and 97 MICCAI papers. In the second stage, we conducted a targeted search on GitHub, using similar keywords to identify highly starred repositories published since 2022. We reviewed the top results from the first ten pages after sorting by stars.

For each identified paper or Github repository, we checked whether open-source code and model weights were provided. If the training data is open source in addition to the training details and the code is shared, then even if model weights are not available, we recorded it as an open-source model. We did this because, theoretically, given the code, the training details, and the training data, one could obtain the weights by training the model the same way on the same data. The search for the two sources was done from August 2024 to December 2024.

The search yielded 52 open-source models that met our criteria. In summary, to find the open-source models, we have perused the Github pages of many publications published as part of the main conferences of MICCAI 2024, MICCAI 2023, and MICCAI 2022 as well as the journals Medical Image Analysis (MedIA) and IEEE Transactions in Medical Imaging (TMI).

From July 2025 to September 2025, we later expanded our search strategy to ensure a broader and more systematic coverage of the literature. Specifically, we used Google Scholar to search for ultrasound deep learning models published after 2022 Year using the keywords “ultrasound” + “deep learning”. We reviewed the first 20 pages of results for each query, which corresponds to several hundred candidate works, and selected representative high-quality papers based on (i) publication in top-tier venues, (ii) relevance to ultrasound modeling, and (iii) shared a link to a GitHub repository. This brought the total number of found open-source models to 56.

There are specific characteristics we report for open-source models, including direct links to the open-source code, the task the model was designed for, the corresponding open-source dataset and its accessibility, training details, availability of model weights, competing interest statements, authorship and contribution statements, and software citations. These characteristics then make up the columns of the model table as shown in Table 2. We categorize the models based on 13 different tasks: Image enhancement, generation, pretraining/foundation model, detection, segmentation, estimation, classification, post-processing, report generation, scanning-guide, explainability, reconstruction, and registration. Here, Image Enhancement implies enhancing the low quality ultrasound images to the high-quality images. Post-processing refers to the matching of clinical post-processing techniques typically found in commercial ultrasound scanners. Estimation means prediction or quantification of different diagnostic parameters from ultrasound images such as ejection fraction, biometry, displacement, etc. Scanning-guide indicates automated scanning guidance algorithm designed to help sonographers capture high-quality ultrasound images.

Scoring datasets and models

We draw inspiration from the data quality score used by Health Data Research UK (HDRUK)30,31 to define an ultrasound dataset quality score. In this context, datasets are not scored based on the quality of the data samples or how well-annotated they are, but rather on how complete the information shared on the dataset is. We have adapted the HDRUK score, and for the sake of clarity, we refer to our modified HDRUK score as SonoDQS.

It is worth noting that the score components are weighted. Different characteristics that contribute to SonoDQS have different weights associated with them based on their relative importance. For SonoDQS, the weighting of the different characteristics was chosen as follows. The characteristics that we consider more important make up the characteristics that are part of the summary table. These characteristics have been given twice as much weight as those only in the detailed table.

SonoDQS quantifies the completeness of data entries by weighting completed fields, summed in the numerator. The denominator is the total number of dataset characteristics. The result provides a percentage that reflects the extent of completeness, adjusted for the relative importance or weight of the different characteristics.

HDRUK scores are binned into four levels: “bronze”, “silver”, “gold”, and “platinum”30. For SonoDQS we also use “platinum”, “gold”, “silver”, and “steel” as rankings. However, additionally we include “unrated”, which denotes datasets that that have significant gaps in data reporting or unverifiable details.

Initially, for SonoDQS, we assigned a level of “platinum” for scores ≥0.6, “gold” for scores <0.6 and ≥0.5, “silver” for scores <0.5 and ≥0.4, and “bronze” for scores below 0.4. Level boundaries were subsequently refined empirically as follows.

Firstly, to emphasize the greater quality of platinum and gold, we adjusted the level thresholds as follows: ≥0.7 for the “platinum” level, <0.7 and ≥0.55 for “gold”, <0.55 and ≥0.25 for “silver”, <0.25 and ≥0.1 for “bronze”. Datasets that score <0.1 are considered “unrated”.

The thresholds were further refined so that the threshold for silver became ≥0.57. Two more levels: “diamond” (to be the highest) and “steel” (to be above “unrated”) were subsequently introduced. The final levels were fixed at “diamond” ≥0.87, “platinum” <0.875 and ≥0.77, “gold” <0.77 and ≥0.67, “silver” <0.67 and ≥0.57, “bronze” <0.5 and ≥0.45, “steel” <0.45 and ≥0.32, and “unrated” <0.32. The SonoDQS level boundary values were set early while dataset collection was still ongoing (when no more than 32 datasets had been found) to define wide, non-overlapping ranges even as we expanded from four to five to seven levels. These values were agreed on by our internal team, ensuring a coverage of a wide range of values, and then fixed for all subsequent analyses, avoiding post hoc fitting upon completion of the search for datasets.

Our motivation and justification for the threshold choices is to reward datasets for being more open about the characteristics of the dataset and how it was collected. Open-sourced datasets can nonetheless be useful for research, irrespective of the richness of the metadata and our naming convention was chosen to recognize the current breadth of metadata available from zero upwards.

A perfect SonoDQS (1.0) score means that possible details that a majority of researchers and practitioners might want to know about a given dataset have been revealed by the publishers of the dataset. The less of those details are available, the lower the score. Those details, or characteristics, were determined in an iterative process. First, we started with the details that MICCAI Challenges32 are expected to include when introducing a dataset for a Challenge. Then, we cull the details that are irrelevant to ultrasound imaging specifically, while adding missing characteristics that are important to know before working on an ultrasound dataset. Then, we ranked the characteristics into two tiers to reflect their importance to a researcher who has yet to start working on a dataset.

The higher-tier characteristics have twice as much of an effect (value = 1 + 1) on the SonoDQS on the score than the lower tier (value = 1). If information pertaining characteristic is not available, a dataset gets a value = 0 for that characteristic. The values are summed together and averaged, giving us the SonoDQS score. Therefore, assuming we are only working with three characteristics where one is high-tier and is filled in, one is low-tier and is filled in, one is low-tier but not filled in, then the SonoDQS score would be ((1 + 1) + 1 + 0)/4.

Like the publicly available datasets, we also rated the open-source models. It is important to emphasize that we do not rate them based on the performance on tasks but rather how clearly the authors of the model have explained what the model does, how the model was trained, and what data it was trained on.

Inspired by RipetaScores33, we developed a modified scoring method tailored to open-source ultrasound models, which we call the Sonographic Model Quality Score (SonoMQS). Unlike the RipetaScore, SonoMQS omits certain criteria less relevant to this context, such as biological materials documentation. Instead, it emphasizes transparency and accessibility in deep learning models.

RipetaScores are not specific to machine learning-based models but rather a mechanism to score scientific research33. In a RipetaScore, there are three main considerations: reproducibility, professionalism, and research. Reproducibility focuses on whether the research being scored has enough information associated with it that would allow it to be reproduced, such as the availability of the data the model was trained on. The reproducibility category considers aspects such as the availability and location of data, the availability of code, software citations, and the documentation of biological materials. The professionalism category assesses the presence of author contribution statements, authorship clarity, competing interest declarations, ethical approval details, and funding transparency. The research category evaluates the clarity of study objectives and the presence of well-defined section headers in the manuscript. Together, these components provide a comprehensive measure of a study’s adherence to good scientific practices.

For SonoMQS, we give a model a point for affirmative (i.e., “yes”) to each of the following twelve questions: (1) training dataset is public, (2) model weights are public, (3) code is shared, (4) training details mentioned, (5) study objective mentioned, (6) funding statement mentioned, (7) ethics approval statement mentioned, (8) competing interests (conflict of interests) statement mentioned, (9) authorship mentioned, (10) authorship contribution statement mentioned, (11) code availability statement mentioned, (12) and software citations included, with questions (1), (2), (3), and (4) being weighed twice as much. The total number of points is then divided by 16 to obtain the normalized score reported in Table 2 as SonoMQS.

It is important to emphasize that SonoMQS does not measure a model’s performance in its given task. It is not a typical evaluation metric. It is a score that reflects the quality of the reporting surrounding a given model. For example, a high SonoMQS score for a model that performs segmentation does not mean that the model is excellent at segmentation, but rather that the developers of the model have been forthcoming and open about details such as how the model was trained or what the model was trained on.

Data availability

The collected data was made available in the tables in the main paper and the corresponding webpages. The corresponding webpages will be made available online upon paper acceptance. Since we do not train or test our own or others’ deep learning models, we consider the code availability section to not be relevant for this work.

References

Categories ∣ miccai 2023 - accepted papers. https://conferences.miccai.org/2023/papers/categories/ (2023).

Organizers, M. C. Miccai 2022 open access papers and reviews. https://conferences.miccai.org/2022/papers/categories/ (2022).

Organizers, M. C. Miccai 2021 open access papers and reviews. https://miccai2021.org/openaccess/paperlinks/categories/index.html (2021).

Sarker, M. M. K. et al. Comformer: classification of maternal-fetal and brain anatomy using a residual cross-covariance attention guided transformer in ultrasound. IEEE Transact. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 70, 1417–1427 (2023).

Sudharson, S. & Kokil, P. An ensemble of deep neural networks for kidney ultrasound image classification. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 197, 105709 (2020).

Zhu, Y.-C., Jin, P.-F., Bao, J., Jiang, Q. & Wang, X. Thyroid ultrasound image classification using a convolutional neural network. Ann. Trans. Med. 9, 1526 (2021).

Zeng, X., Wen, L., Liu, B. & Qi, X. Deep learning for ultrasound image caption generation based on object detection. Neurocomputing 392, 132–141 (2020).

Alsharid, M. et al. A course-focused dual curriculum for image captioning. In 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 716–720 (IEEE, 2021).

Yang, S. et al. Automatic ultrasound image report generation with adaptive multimodal attention mechanism. Neurocomputing 427, 40–49 (2021).

Zeng, X.-H., Liu, B.-G. & Zhou, M. Understanding and generating ultrasound image description. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 33, 1086–1100 (2018).

Guo, X., Men, Q. & Noble, J. A. Mmsummary: multimodal summary generation for fetal ultrasound video. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 678–688 (Springer, 2024).

Alsharid, M. Generating Textual Captions for Ultrasound Visuals in an Automated Fashion. Ph.D. thesis, University of Oxford (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. Uscl: pretraining deep ultrasound image diagnosis model through video contrastive representation learning. In Medical image computing and computer assisted intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021, Proceedings, Part VIII 24 627–637 (Springer, 2021).

Fu, Z. et al. Anatomy-aware contrastive representation learning for fetal ultrasound. In European Conference on Computer Vision 422–436 (Springer, 2022).

Gridach, M. et al. Dual representation learning from fetal ultrasound video and sonographer audio. In 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 1–4 (IEEE, 2024).

Sarker, M. M. K., Yasrab, R., Alsharid, M., Papageorghiou, A. T. & Noble, J. A. Cnseg-gan: a lightweight generative adversarial network for segmentation of crl and nt from first-trimester fetal ultrasound. In 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Ansari, M. Y. et al. Advancements in deep learning for b-mode ultrasound segmentation: a comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 8, 2126–2149 (2024).

Khan, S. M. et al. A global review of publicly available datasets for ophthalmological imaging: barriers to access, usability, and generalisability. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e51–e66 (2021).

Magudia, K., Bridge, C. P., Andriole, K. P. & Rosenthal, M. H. The trials and tribulations of assembling large medical imaging datasets for machine learning applications. J. Digit. Imaging 34, 1424–1429 (2021).

Kohli, M. D., Summers, R. M. & Geis, J. R. Medical image data and datasets in the era of machine learning-whitepaper from the 2016 c-MIMI meeting dataset session. J. Digit. Imaging 30, 392–399 (2017).

Google. Google search. https://www.google.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

Code, P. W. Papers with code. https://paperswithcode.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

WeChat. Wechat search. https://www.wechat.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

Google. Google scholar. https://scholar.google.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06

OpenAI. Chatgpt. https://chat.openai.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

Microsoft. Bing search engine. https://www.bing.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

Avola, D., Cinque, L., Fagioli, A., Foresti, G. & Mecca, A. Ultrasound medical imaging techniques: a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–38 (2021).

Google. Google dataset search. https://datasetsearch.research.google.com/ Accessed: 2024-09-06.

Challenges, M. B. Structured description of a challenge design. https://www.biomedical-challenges.org/miccai2024/assets/StructuredDescriptionOfAChallengeDesign.pdf Accessed: 2024-04-16.

UK, H. D. R. Data utility evaluation https://www.hdruk.ac.uk/helping-with-health-data/data-utility-evaluation/ (2024).

Gordon, B. et al. Development of a data utility framework to support effective health data curation. BMJ Health Care Inform. 28, e100303 (2021).

MICCAI Challenges. https://www.biomedical-challenges.org/miccai2024/assets/StructuredDescriptionOfAChallengeDesign.pdf [Accessed 01-05-2024]

Sumner, J. Q., Vitale, C. H. & McIntosh, L. D. Ripetascore: measuring the quality, transparency, and trustworthiness of a scientific work. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 6, 751734 (2022).

Burgos-Artizzu, X. P. et al. Fetal_planes_db: common maternal-fetal ultrasound images. Nat. Sci. Rep. 19, 10200 (2020).

Xiao, Y., Fortin, M., Unsgård, G., Rivaz, H. & Reinertsen, I. Re trospective evaluation of cerebral tumors (resect): a clinical database of pre-operative mri and intra-operative ultrasound in low-grade glioma surgeries. Med. Phys. 44, 3875–3882 (2017).

Castro, E. R., Espinoza, F. R. N. & Pedraza, L. Ddti: an open access database of thyroid ultrasound images. http://cimalab.unal.edu.co/?lang=en&mod=project&id=31 (2023).

Montoya, A. et al. Ultrasound nerve segmentation. https://kaggle.com/competitions/ultrasound-nerve-segmentation (2016).

Organizers, U. I. E. C. Ultrasound image enhancement challenge 2023 datasets. https://ultrasoundenhance2023.grand-challenge.org/datasets/ (2023).

Huang, Z., Long, G., Wessler, B. & Hughes, M. C. A new semi-supervised learning benchmark for classifying view and diagnosing aortic stenosis from echocardiograms. In Proc. 6th Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference (MLHC) (2021).

Ebadi, A. et al. Covidx-US - an open-access benchmark dataset of ultrasound imaging data for AI-driven COVID-19 analytics. Front Biosci. 27, 198 (2022).

Singla, R. et al. The open kidney ultrasound data set. In International Workshop on Advances in Simplifying Medical Ultrasound 155–164 (Springer, 2023).

Prabakaran, B. S., Hamelmann, P., Ostrowski, E. & Shafique, M. Fpus23: an ultrasound fetus phantom dataset with deep neural network evaluations for fetus orientations, fetal planes, and anatomical features. IEEE Access 11, 58308–58317 (2023).

Medicine, S. C. & (AIMI), I. Stanford AIMI dataset. https://stanfordaimi.azurewebsites.net/datasets/a72f2b02-7b53-4c5d-963c-d7253220bfd5 (2023).

AIMI, S. Echonet-dynamic: a large video dataset of echocardiograms for cardiac motion and chamber sizes assessment. https://stanfordaimi.azurewebsites.net/datasets/834e1cd1-92f7-4268-9daa-d359198b310a (2020).

Ouyang, D. et al. Video-based ai for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature 580, 252–256 (2020).

Cunningham, R. & Cronin, N. Fallmud: fascicle lower leg muscle ultrasound dataset. https://kalisteo.cea.fr/index.php/fallmud/ (2020).

Michard, H., Luvison, B., Pham, Q.-C., Morales-Artacho, A. J. & Guilhem, G. Aw-net: automatic muscle structure analysis on b-mode ultrasound images for injury prevention. In Proc. 12th ACM Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology, and Health Informatics 1–9 (ACM, 2021).

Shao, W. & Brisbane, W. Micro-ultrasound prostate segmentation dataset [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10475293 (2024).

Project, H. H. Camus: segmentation of echocardiographic images dataset. https://humanheart-project.creatis.insa-lyon.fr/database/#collection/6373703d73e9f0047faa1bc8 (2022).

Leclerc, S. et al. Deep learning for segmentation using an open large-scale dataset in 2d echocardiography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 2198–2210 (2019).

AIMI, S. Echonet-lvh: a large video dataset of echocardiograms for cardiac function and structure assessment. https://stanfordaimi.azurewebsites.net/datasets/5b7fcc28-579c-4285-8b72-e4238eac7bd1 (2022).

Duffy, G. et al. High-throughput precision phenotyping of left ventricular hypertrophy with cardiovascular deep learning. JAMA Cardiol. 7, 386–395 (2022).

Marcinkevičs, R. et al. Regensburg pediatric appendicitis dataset (1.03) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7711412 (2023).

Marcinkevics, R. et al. Interpretable and intervenable ultrasonography-based machine learning models for pediatric appendicitis. Med. Image Anal. 91, 103042 (2024).

Basu, S. et al. Unsupervised contrastive learning of image representations from ultrasound videos with hard negative mining. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 423–433 (Springer, 2022).

Basu, S. et al. Gallbladder ultrasound video (gbusv) dataset. https://gbc-iitd.github.io/data/gbusv (2022).

Basu, S., Gupta, M., Rana, P., Gupta, P. & Arora, C. Surpassing the human accuracy: gallbladder cancer detection from usg with curriculum learning. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 20854–20864 (2022).

Basu, S., Gupta, M., Rana, P., Gupta, P. & Arora, C. Gallbladder cancer ultrasound (gbcu) dataset. https://gbc-iitd.github.io/data/gbcu (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. A new dataset and a baseline model for breast lesion detection in ultrasound videos. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 614–623 (Springer, 2022).

Lin, Z. et al. Cva-net: a baseline model for breast lesion detection in ultrasound videos. https://github.com/jhl-Det/CVA-Net (2022).

Leitner, C. et al. Automatic tracking of the muscle tendon junction in healthy and impaired subjects using deep learning. In 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine Biology Society (EMBC) 4770–4774 (IEEE, 2020).

Leitner, C. et al. A human-centered machine-learning approach for muscle-tendon junction tracking in ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 1920–1930 (2021).

Leitner, C. et al. deepmtj test-set data (2021).

Leitner, C. deepmtj: muscle-tendon junction tracking in ultrasound images. https://osf.io/wgy4d/ (2021).

Al-Dhabyani, W., Gomaa, M., Khaled, H. & Fahmy, A. Breast ultrasound images dataset [data set]. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/aryashah2k/breast-ultrasound-images-dataset (2020).

Al-Dhabyani, W., Gomaa, M., Khaled, H. & Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief. 28, 104863 (2020).

Mercier, L. et al. Bite: brain images of tumors for evaluation database [data set]. https://nist.mni.mcgill.ca/bite-brain-images-of-tumors-for-evaluation-database/ (2012).

Mercier, L. et al. Online database of clinical mr and ultrasound images of brain tumors. Med. Phys. 39, 3253–3261 (2012).

Alfageme, F. Dermatologic ultrasound images for classification [data set]. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/alfageme/dermatologic-ultrasound-images (2022).

Laverde-Saad, A. et al. Discriminative deep learning based benignity/malignancy diagnosis of dermatologic ultrasound skin lesions with pretrained artificial intelligence architecture. Ski. Res. Technol. 28, 35–39 (2022).

Adiwijaya, NOVIA WISESTY, U. & Astuti, W. Polycystic ovary ultrasound images dataset. https://doi.org/10.34820/FK2/QVCP6V (2021).

Meiburger, K. M. et al. Carotid ultrasound boundary study (cubs): an open multicenter analysis of computerized intima–media thickness measurement systems and their clinical impact. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 47, 2442–2455 (2021).

Nelson, A. Development of an ai/ml-ready knee ultrasound dataset in a population-based cohort. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SKP9IB (2023).

Biobank, U. Search. https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/search.cgi?wot=0&srch=ultrasound&yfirst=2000&ylast=2024 (2024).

Dorent, R., Wells, W. & Kapur, T. Remind2reg dataset (2023) (2.1) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11387725 (2024).

Juvekar, P. et al. Remind: The brain resection multimodal imaging database. Sci. Data 11, 494 (2024).

van den Heuvel, T. L. A., de Bruijn, D., de Korte, C. L. & van Ginneken, B. Automated measurement of fetal head circumference using 2d ultrasound images [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1327317 (2018).

van den Heuvel, T. L., de Bruijn, D., de Korte, C. L. & Ginneken, B. V. Automated measurement of fetal head circumference using 2d ultrasound images. PLoS ONE 13, e0200412 (2018).

NeuronXJTU & palkia1998. Kfgnet: source code for video classification in kfgnet. https://github.com/NeuronXJTU/KFGNet (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Busis: a benchmark for breast ultrasound image segmentation. Healthcare 10, 729 (2022).

KZ Tehrani, A., Mirzaei, M. & Rivaz, H. Semi-supervised training of optical flow convolutional neural networks in ultrasound elastography. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 504–513 (Springer, 2020).

Mirzaei, M., Asif, A. & Rivaz, H. Combining total variation regularization with window-based time delay estimation in ultrasound elastography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 2744–2754 (2019).

Tehrani, A. K., Sharifzadeh, M., Boctor, E. & Rivaz, H. Bi-directional semi-supervised training of convolutional neural networks for ultrasound elastography displacement estimation. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 69, 1181–1190 (2022).

Tehrani, K. Z., Mirzaei, M. & Rivaz, H. Ultrasound elastography dataset for unsupervised training. https://users.encs.concordia.ca/ĩmpact/ultrasound-elastography-dataset-for-unsupervised-training/ (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Trackerless 3d freehand ultrasound reconstruction challenge - train dataset (part 1) (1.0.0) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11178509 (2024).

Yap, M. H. et al. Automated breast ultrasound lesions detection using convolutional neural networks. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 1218–1226 (2017).

Yap, M. Datasets/software. https://helward.mmu.ac.uk/STAFF/m.yap/dataset.php (2023).

Krönke, M. et al. Segthy dataset: open-access dataset for thyroid and neck segmentation. https://www.cs.cit.tum.de/camp/publications/segthy-dataset/ (2023).

Krönke, M. et al. Tracked 3d ultrasound and deep neural network-based thyroid segmentation reduce interobserver variability in thyroid volumetry. PLos ONE 17, e0268550 (2022).

Bi, Y. et al. Mi-segnet: Mutual information-based us segmentation for unseen domain generalization. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 130–140 (Springer, 2023).

yuan 12138. Mi-segnet: mutual information-based us segmentation for unseen domain generalization. https://github.com/yuan-12138/MI-SegNet (2023).

Li, J. et al. Ultra- sound report generation with cross-modality feature alignment via unsupervised guidance. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging (2024)

Li, J. et al. Ultrasound report generation with cross-modality feature alignment via unsupervised guidance. https://lijunrio.github.io/Ultrasound-Report-Generation/ (2023).

Mo, Y. et al. Hover-trans: anatomy-aware hover-transformer for roi-free breast cancer diagnosis in ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1696–1706 (2023).

Zhuang, Z., Li, N., Joseph Raj, A. N., Mahesh, V. G. & Qiu, S. An rdau-net model for lesion segmentation in breast ultrasound images. PLoS ONE 14, e0221535 (2019).

Baum, Z. M. C., Saeed, S. U., Min, Z., Hu, Y. & Barratt, D. C. MR to ultrasound registration for prostate challenge - dataset (1.0.0) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7870105 (2023).

Baum, Z. M. C., Saeed, S. U., Min, Z., Hu, Y. & Barratt, D. C. mu-regpro challenge: MR to ultrasound registration for prostate. https://muregpro.github.io/ Accessed: 2024-10-14 (2023).

Hamid, S. et al. The smarttarget biopsy trial: a prospective, within-person randomised, blinded trial comparing the accuracy of visual-registration and magnetic resonance imaging/ultrasound image-fusion targeted biopsies for prostate cancer risk stratification. Eur. Urol. 75, 733–740 (2019).

Natarajan, S., Priester, A., Margolis, D., Huang, J. & Marks, L. Prostate MRI and ultrasound with pathology and coordinates of tracked biopsy (prostate-MRI-US-biopsy) (version 2) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.7937/TCIA.2020.A61IOC1A (2020).

Li, J., Zhang, P., Wang, T., Wang, K. & Sheng, B. Lepset (1.0) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8041285 (2023).

Chavignon, A. et al. Opulm pala (1.1) [data set]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4343435 (2020).

Heiles, B. et al. Performance benchmarking of microbubble-localization algorithms for ultrasound localization microscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 605–616 (2022).

Biobank, U. Data-field 30005: carotid artery ultrasound (mat format). https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/field.cgi?id=30005 (2024).

Wiedemann, N. et al. COVID-BLUeS - A Prospective Study on the Value of AI in Lung Ultrasound Analysis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Infor. 29, 6301–6310 (2025).

Born, J. et al. Accelerating detection of lung pathologies with explainable ultrasound image analysis. Appl. Sci. 11, 672 (2021).

Gow, B. et al. Mimic-iv-echo: echocardiogram matched subset. PhysioNet https://doi.org/10.13026/EF48-V217 (2023).

Tyagi, A., et al. Nerve block target localization and needle guidance for autonomous robotic ultrasound guided regional anesthesia. In: 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pp. 5867–5872 (IEEE, 2024).

Regional-US. Brachial plexus and needles annotations data in ultrasound videos. https://github.com/Regional-US/brachial_plexus (2024).

Collaborative, U. I. Unity imaging echocardiography datasets. institution = National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and Imperial College, https://data.unityimaging.net, Available under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license (2024).

Leenings, R. et al. C-trus: a novel dataset and initial benchmark for colon wall segmentation in transabdominal ultrasound. In International Workshop on Advances in Simplifying Medical Ultrasound 101–111 (Springer, 2024).

RLeenings & wwu mmll. C-trus: colon wall segmentation in transabdominal ultrasound dataset. https://github.com/wwu-mmll/c-trus, Dataset for colon wall segmentation in transabdominal ultrasound images (2024).

Sappia, M. S. Acouslic-AI : abdominal circumference operator-agnostic ultrasound measurement (1.1) Prenatal Ultrasound Frames acquired by novice operators using a pre-specified blind-sweep protocol. Includes annotations of fetal abdominal circumference and reference measurements (in mm) per sweep. Updated in Version 1.1 to correct circumference measurement calculations. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12697994 (2024).

Handa, P. et al. Pcosgen-train dataset. Zenodo (2023).

Handa, P. et al. Pcosgen-test dataset https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10510879 (2024).

Eisenbrey, J., Lyshchik, A. & Wessner, C. Ultrasound data of a variety of liver masses. The Cancer Imaging Archive (2021).

Zamanian, H. et al. Behsof: advanced non-alcoholic fatty liver dataset with clinical metadata and ultrasound images for deep learning models. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/BEHSOF_Advanced_Non-alcoholic_fatty_liver_dataset_with_clinical_metadata_and_ultrasound_images_for_Deep_learning_Models/26389069/4 (2024).

Belasso, C. J. et al. Luminous database: lumbar multifidus muscle segmentation from ultrasound images. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21, 703 (2020).

Klepich, J. Liver ultrasound dataset. https://universe.roboflow.com/joe-klepich/liver_ultrasound (2023).

Byra, M. et al. Dataset of b-mode fatty liver ultrasound images. Zenodo 5281 (2018).

Yiming, X. et al. Annotated ultrasound liver images. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7272660 (2022).

Painchaud, N., Duchateau, N., Bernard, O. & Jodoin, P.-M. Echocardiography segmentation with enforced temporal consistency. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 2867–2878 (2022).

Gómez-Flores, W., Gregorio-Calas, M. J. & Coelho de Albuquerque Pereira, W. Bus-bra: a breast ultrasound dataset for assessing computer-aided diagnosis systems. Med. Phys. 51, 3110–3123 (2024).

Gómez-Flores, W., Gregorio-Calas, M. J. & de Albuquerque Pereira, W. C. Bus-bra: a breast ultrasound dataset for assessing computer-aided diagnosis systems. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8231412 (2023).

Zhang, H., Liu, Q., Han, X., Niu, L. & Sun, W. Tn5000: An ultrasound image dataset for thyroid nodule detection and classification. Sci. Data 12, 1437 (2025).

Elmekki, H. et al. Cactus: an open dataset and framework for automated cardiac assessment and classification of ultrasound images using deep transfer learning. Comput. Biol. Med. 190, 110003 (2025).

A, S., POCUS LUS datasets. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/POCUS_LUS_Datasets/29364743 (2025).

Dorosti, S. et al. High-resolution ultrasound data for ai-based segmentation in mouse brain tumor. Sci. Data 12, 1322 (2025).

Dorosti, S. High-resolution ultrasound data for AI-based segmentation in mouse brain tumor. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/_b_i_High-Resolution_Ultrasound_Data_for_AI-Based_Segmentation_in_Mouse_Brain_Tumor_i_b_b_b_/27237894 (2025).

Cervera Gontard, L. Dataset of 3D ultrasound neuroimages. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14917169 (2025).

Katumba, A. et al. A dataset of lung ultrasound images for automated ai-based lung disease classification. Data Brief 62, 112034 (2025).

JeevaWS. Ultrasound normal kidney image dataset. https://universe.roboflow.com/jeevaws/ultrasound-normal-kidney-image (2025).

Songxiong, W. et al. Focus: four-chamber ultrasound image dataset for fetal cardiac biometric measurement. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14597550 (2025).

Li, H. et al. An annotation-free restoration network for cataractous fundus images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 1699–1710 (2022).

Iskandar, M. et al. Towards realistic ultrasound fetal brain imaging synthe- sis. In: Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, Short Paper Track (2023). https://openreview.net/forum?id=mad9Y7khs

Jiao, J. et al. Usfm: a universal ultrasound foundation model generalized to tasks and organs towards label efficient image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 96, 103202 (2024).

Born, J. et al. Accelerating detection of lung pathologies with explainable ultrasound image analysis. Appl. Sci. 11, 672 (2022).

Chen, G., Li, L., Dai, Y., Zhang, J. & Yap, M. H. Aau-net: an adaptive attention u-net for breast lesions segmentation in ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1289–1300 (2022).

Lin, X. Xiang, Y. & Yu, L. Yan, Z.: Beyond adapting SAM: Towards end-to-end ultrasound image segmentation via auto prompting. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 24–34 (Springer, 2024).

Ouyang, D. et al. Echonet-dynamic: a large new cardiac motion video data resource for medical machine learning. In NeurIPS ML4H Workshop 1–11 (2019).

Basu, S., Gupta, M., Madan, C., Gupta, P. & Arora, C. Focusmae: gallbladder cancer detection from ultrasound videos with focused masked autoencoders. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 11715–11725 (IEEE, 2024).

Christensen, M., Vukadinovic, M., Yuan, N. & Ouyang, D. Vision–language foundation model for echocardiogram interpretation. Nat. Med. 30, 1481–1488 (2024).

Stojanovski, D., Hermida, U., Lamata, P., Beqiri, A. & Gomez, A. Echo from noise: synthetic ultrasound image generation using diffusion models for real image segmentation. In International Workshop on Advances in Simplifying Medical Ultrasound 34–43 (Springer, 2023).

Sun, A. et al. Boosting breast ultrasound video classification by the guidance of keyframe feature centers. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 441–451 (Springer, 2023).

Huang, O. et al. Mimicknet, mimicking clinical image post-processing under black-box constraints. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 39, 2277–2286 (2020).

Tang, Y. et al. Pld-al: Pseudo-label divergence-based active learning in carotid intima-media segmentation for ultrasound images. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 57–67 (Springer, 2023).

Yu, H. et al. Mining negative temporal contexts for false positive suppression in real-time ultrasound lesion detection. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 3–13 (Springer, 2023).

Dorent, R. et al. Unified brain MR-ultrasound synthesis using multi-modal hierarchical representations. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 448–458 (Springer, 2023).

Smith, D. H., Lineberger, J. P. & Baker, G. H. On the relevance of temporal features for medical ultrasound video recognition. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 744–753 (Springer, 2023).

Velikova, Y., Azampour, M. F., Simson, W., Gonzalez Duque, V. & Navab, N. Lotus: learning to optimize task-based us representations. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 435–445 (Springer, 2023).

Avisdris, N. et al. Biometrynet: landmark-based fetal biometry estimation from standard ultrasound planes. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 279–289 (Springer, 2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Key-frame guided network for thyroid nodule recognition using ultrasound videos. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 238–247 (Springer, 2022).

Thomas, S., Gilbert, A. & Ben-Yosef, G. Light-weight spatio-temporal graphs for segmentation and ejection fraction prediction in cardiac ultrasound. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 380–390 (Springer, 2022).

Lee, K. et al. Usg-net: Deep learning-based ultrasound scanning-guide for an orthopedic sonographer. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 23–32 (Springer, 2022).

Velikova, Y., Simson, W., Azampour, M. F., Paprottka, P. & Navab, N. Cactuss: common anatomical ct-us space for us examinations. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 19, 861–869 (2024).

KZ Tehrani, A. & Rivaz, H. Physically inspired constraint for unsupervised regularized ultrasound elastography. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 218–227 (Springer, 2022).

Tang, F., Ding, J., Wang, L., Xian, M. & Ning, C. Multi-level global context cross consistency model for semi-supervised ultrasound image segmentation with diffusion model. Preprint at arXiv:2305.09447 (2023).

Tang, F., Wang, L., Ning, C., Xian, M. & Ding, J. Cmu-net: a strong convmixer-based medical ultrasound image segmentation network. In 2023 IEEE 20th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI) 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Reynaud, H. et al. Feature-conditioned cascaded video diffusion models for precise echocardiogram synthesis. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 142–152 (Springer, 2023).

Nguyen, T. T. H., Truong, V. B., Nguyen, V. T. K., Cao, Q. H. & Nguyen, Q. K. Towards trust of explainable ai in thyroid nodule diagnosis. In International Workshop on Health Intelligence 11–26 (Springer, 2023).

Xu, H. et al. LGRNet: Local-global reciprocal network for uterine fibroid segmentation in ultra- sound videos. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 667–677 (Springer, 2024).

Li, Q. et al. Nonrigid reconstruction of freehand ultrasound without a tracker. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 689–699 (Springer, 2024).

Nasiri-Sarvi, A., Hosseini, M.S., & Rivaz, H. Vision mamba for classification of breast ultrasound images. In: Deep Breast Workshop on AI and Imaging for Diagnostic and Treatment Challenges in Breast Care, pp. 148–158 (Springer, 2024).

Lei, L. et al. Epicardium prompt-guided real-time cardiac ultrasound frame-to-volume registration. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 618–628 (Springer, 2024).

Tmenova, O., Velikova, Y., Saleh, M., & Navab, N. Deep spectral methods for unsupervised ultrasound image interpretation. In: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, pp. 200–210 (Springer, 2024).

Li, H. et al. A spatio-temporal graph convolutional network for ultrasound echocardiographic landmark detection. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103272 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. Neural implicit surface reconstruction of freehand 3D ultrasound volume with geometric constraints. Med. Image Anal. 98, 103305 (2024).

Laumer, F. et al. Weakly supervised inference of personalized heart meshes based on echocardiography videos. Med. Image Anal. 83, 102653 (2023).

Basu, S., Gupta, M., Rana, P., Gupta, P. & Arora, C. Radformer: Transformers with global–local attention for interpretable and accurate gallbladder cancer detection. Med. Image Anal. 83, 102676 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Ift-net: interactive fusion transformer network for quantitative analysis of pediatric echocardiography. Med. Image Anal. 82, 102648 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Deep semi-supervised ultrasound image segmentation by using a shadow aware network with boundary refinement. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 3779–3793 (2023).

Li, J., Li, S., Hu, Y. & Tao, H. A self-guided framework for radiology report generation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 588–598 (Springer, 2022).

Hahne, C., Chabouh, G., Chavignon, A., Couture, O. & Sznitman, R. RF-ULM: ultrasound localization microscopy learned from radio-frequency wavefronts. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43, 3253–3262 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Dsmt-net: Dual self-supervised multi-operator transformation for multi-source endoscopic ultrasound diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43, 64–75 (2023).

Chen, Y., Zhang, C., Ding, C. H. & Liu, L. Generating and weighting semantically consistent sample pairs for ultrasound contrastive learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1388–1400 (2022).

Lucassen, R. T. et al. Deep learning for detection and localization of b-lines in lung ultrasound. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 4352–4361 (2023).

Basu, S., Gupta, M., Rana, P., Gupta, P. & Arora, C. Surpassing the human accuracy: detecting gallbladder cancer from usg images with curriculum learning. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 20886–20896 (IEEE, 2022).

Jiang, H. et al. Microsegnet: a deep learning approach for prostate segmentation on micro-ultrasound images. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 112, 102326 (2024).

Płotka, S. et al. Deep learning fetal ultrasound video model match human observers in biometric measurements. Phys. Med. Biol. 67, 045013 (2022).

Blanken, N. et al. Super-resolved microbubble localization in single-channel ultrasound rf signals using deep learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 2532–2542 (2022).

Salvucci, M. pyanatomogram: a python package to annotate and highlight organs and tissues in figures. https://pypi.org/project/pyanatomogram/ (2021).

Moreno, P. et al. Expression atlas update: gene and protein expression in multiple species. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D129–D140 (2022).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Inc., P. T. Collaborative data science. https://plot.ly (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the InnoHK-funded Hong Kong Centre for Cerebro-cardiovascular Health Engineering (COCHE), the UKRI (UK Research and Innovation) (grant reference EP/X040186/1 (Turing AI Fellowship: UltraSound Multi-Modal Video-based Human-Machine Collaboration)), and the EPSRC (Engineering and Physical Research Council) (program grant EP/T028572/1, VisualAI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. was involved in literature search, figures, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, conceptualization, data curation, methodology, validation, visualization, project administration, and writing. X.G. was involved in literature search, data collection, conceptualization, data curation, methodology, validation, and writing. Q.M. was involved in literature search, data collection, data curation, methodology, validation, and writing. P.S. was involved in figures, data analysis, data interpretation, data curation, methodology, validation, visualization, and writing. D.M. was involved in literature search, data collection, data curation, methodology, validation, and writing. R.A. was involved in literature search, data collection, data curation, methodology, and validation. C.O. was involved in data curation, validation, and writing. J.A.N. was involved in literature search, data interpretation, writing, conceptualization, project administration, supervision, resources, funding acquisition, and methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Alison Noble is a senior consultant to Intelligent Ultrasound Ltd, with the consultancy managed by Oxford University Innovation. This connection did not motivate or influence this work in any way, which was conducted independently and as part of her university academic research. Alison Noble is a Trustee of Health Data Research UK, the UK national institute for health data science. HDRUK did not contribute to the paper. We declare no other competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsharid, M., Guo, X., Men, Q. et al. On the public dissemination and open sourcing of ultrasound resources, datasets and deep learning models. npj Digit. Med. 8, 777 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02162-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02162-4