Abstract

Effective first-trimester screening for congenital heart disease (CHD) remains an unmet clinical need, hampered by technical limitations and the absence of validated diagnostic tools. To address this, we collected a vast cohort of 108,521 first-trimester cardiac screenings conducted across multiple regions in China, from which 8062 Doppler flow four-chamber view images were selected. Using this curated dataset, we developed and validated an interpretable deep learning (DL) model that mimics clinical reasoning with diastolic flow patterns, providing accurate and explainable CHD diagnosis in first-trimester. Interpretability analyses confirmed its diagnostic logic strongly aligns with clinical expertise. In rigorous evaluations, the model demonstrated high accuracy across multiple external validation datasets, matched or surpassed experienced clinicians, and showed potential to augment their diagnostic capabilities. To our knowledge, this is the first validated interpretable DL system for first-trimester CHD screening, potentially enabling earlier intervention through an advanced diagnostic window.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD), the most prevalent congenital anomaly worldwide, remains a major contributor to infant morbidity and mortality1,2. Although advances in prenatal imaging and neonatal care have significantly improved survival and quality of life, severe cases continue to impose long-term burdens on families and healthcare systems3,4,5. While mid-trimester fetal echocardiography, typically performed between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation, remains the standard approach for prenatal CHD screening6,7, the growing adoption of nuchal translucency screening has opened a critical window for earlier cardiac assessment between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation8. First-trimester diagnosis can improve perinatal outcomes by enabling timely specialist referral and multidisciplinary intervention8, while also serving as a sentinel marker for chromosomal, genetic, and extracardiac anomalies, prompting early diagnostic work-up9,10,11,12. Moreover, it is particularly valuable for detecting progressive cardiac lesions, such as obstructive outflow tract anomalies, that may evolve over gestation and potentially benefit from in utero therapy13,14,15. Beyond clinical implications, early CHD detection also carries important ethical and emotional implication, affording families more time to process prognostic information and make informed reproductive decisions without the constraints of later gestation, particularly in the context of severe or life-limiting anomalies16,17,18. Recent guidelines from leading societies have endorsed first-trimester fetal cardiac screening, underscoring its growing global importance in early prenatal care19,20.

Despite its potential, first-trimester cardiac screening remains severely limited by low diagnostic accuracy, with reported sensitivity ranging from only 14 to 17% in both high- and low-risk populations21, contrasting sharply with the over 90% sensitivity achieved in the second trimester22. This discrepancy reflects the technical and physiological challenges inherent to early gestation, including the small size and high mobility of the fetal heart, as well as reduced acoustic resolution, all of which hinder the reliable acquisition and interpretation of diagnostic-quality images. While simplified scanning protocols and Doppler flow imaging have been proposed to improve early detection23, first-trimester cardiac assessment remains limited in routine practice. Operator dependency, variable image quality, and high cognitive demands during real-time scanning hinder widespread implementation, particularly in low-resource or high-throughput settings. These constraints underscore the need for automated and interpretable solutions to enable timely, accurate, and scalable CHD screening.

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), is revolutionizing the analysis of medical images, demonstrating expert-level performance in tasks ranging from disease detection to segmentation and diagnosis24,25,26,27. Within prenatal care, ultrasound imaging is indispensable yet inherently operator-dependent and time-consuming, presenting a significant opportunity for AI-assisted solutions. Consequently, AI applications in prenatal ultrasound have rapidly expanded. These include the automated identification of standard fetal planes (e.g., of the brain and abdomen), biometric measurements (e.g., head circumference and femur length), and the screening for structural anomalies such as neural tube defects28,29,30,31. Among these applications, fetal cardiac screening remains one of the most challenging due to the heart’s complex anatomy and dynamic nature. Achieving early and accurate detection of CHD is a critical yet arduous goal. While several studies have explored AI for fetal echocardiography, the majority focus on the second trimester32,33. First-trimester screening presents a promising frontier for earlier CHD detection, but it introduces additional challenges for AI, including smaller anatomical scales and limited available data. Furthermore, the lack of model interpretability poses a significant barrier to clinical trust and adoption34,35,36.

Here, we present an interpretable DL framework for the automated detection of major and specific cardiac abnormalities using Doppler-enhanced four-chamber view (4CV) images acquired between 11 and 14 weeks of gestation. Leveraging a large-scale, multicenter dataset spanning diverse clinical settings, our model outperformed current clinical practice, matching or exceeding expert-level accuracy across multiple external validations. An overview illustrating the overall study design and model framework is provided in Fig. 1. To our knowledge, this is the first validated interpretable DL system for first-trimester fetal cardiac screening, with potential to enable earlier intervention and broaden global access to high-quality prenatal cardiac care.

a A multi-center dataset was established, comprising images with defect labels, cardiac region masks, and flow patterns annotated by expert clinicians. b The proposed model uses cardiac masks to focus attention and predicts flow patterns before determining abnormalities, enhancing interpretability. c Comprehensive validation was performed across external datasets using standard metrics, with performance benchmarked against six clinicians with 5–8 years of experience. Model interpretability was verified through saliency map IoU and flow pattern prediction performance. d A representative case demonstrates the inference process from flow pattern detection to final diagnosis and explanation. 4CV four-chamber view, AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, AVSD atrioventricular septal defect, FSV functional single ventricle, HV hypoplastic ventricles, IoU intersection-over-union.

Results

Sample characteristics

Our study leveraged, to our knowledge, the largest cohort to date for first-trimester fetal cardiac screening, encompassing 108,521 individual cases. A final dataset of 8062 Doppler flow 4CV ultrasound images was curated for model development and validation. Annotation reliability was exceptionally high, with inter-rater agreement exceeding 99% for all flow patterns (Cohen’s κ and Fleiss’ κ values approaching 1.000), confirming the reliability of our annotations (Supplementary Table 1).

Model performance

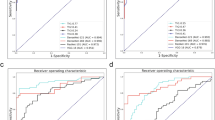

The model demonstrated excellent performance in detecting specific cardiac abnormalities across all validation sets (Fig. 2a and Table 1). In the internal validation set, the model achieved perfect discrimination with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 1.000 (95% CI 1.000–1.000), sensitivity of 0.995 (95% CI 0.988–1.000), and specificity of 0.999 (95% CI 0.997–1.000). Performance remained robust across external validation sets, with AUROCs ranging from 0.925 (95% CI 0.881–0.963) to 1.000 (95% CI 0.999–1.000). Notably, in the largest external validation set 1, the model maintained high discrimination with an AUROC of 0.986 (95% CI 0.980–0.992). For subtype classification, the model also demonstrated strong discriminative ability across different anomaly types (Fig. 2a and Table 1). Performance was consistently high for normal cases and functional single ventricle (FSV), with slightly lower metrics for atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) and hypoplastic ventricles (HV) across both internal and external validation sets. Specifically, AUROCs for normal and FSV typically ranged from 0.886 to 0.978, while those for AVSD and HV were between 0.836 and 0.928. The confusion matrix (Fig. 2b) reveals that misclassifications predominantly occurred between anatomically similar defect types. Decision curve analyses demonstrated the clinical utility of our model across a wide range of threshold probabilities, suggesting potential benefit in clinical implementation (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

a ROC curves for (i) binary classification model on different validation sets and (ii)-(iv) subtype classification model on different validation sets and different subtypes. Clinicians’s true positive and false positive rates are also plotted along with the ROCs for comparison. b Confusion matrix for subtype classification model on validation datasets. c IoU between model-generated saliency maps and expert-annotated cardiac structures. IoU between different cardiac mask annotators is also plotted for comparison. d Radar plots comparing clinician performance metrics (AUROC, Sensitivity, Specificity, F1 score) with and without AI assistance in the binary and subtype classification. e Representative prediction examples. From left to right, each panel shows: the reference label, model-generated saliency map (with red intensity indicating regions of higher model attention), ground truth mask for the cardiac region, model prediction and explanation. AUROC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, AVSD atrioventricular septal defect, FSV functional single ventricle, HV hypoplastic ventricles, IoU intersection-over-union, GT ground truth.

Model interpretability

Across all validation sets, the model achieved consistent IoU scores of approximately 0.8, approaching the inter-annotator consistency among three expert clinicians (IoU approximately 0.9) (Fig. 2c). This demonstrates that the model reliably focuses on clinically relevant cardiac structures during diagnosis, rather than relying on spurious features or artifacts. Supplementary Fig. 7 provides additional saliency map visualizations across various defect subtypes. The model demonstrated strong performance in predicting the three diastolic flow patterns, with F1 scores ranging from 0.893 to 1.000 across all validation sets (Table 2). We also analyzed the relationships between flow pattern features and defect subtype features extracted from the trained model (Supplementary Fig. 6). The results indicated that the learned relationships between flow patterns and defect subtypes were consistent with established clinical knowledge, confirming that the model’s decision-making process aligns with expert diagnostic reasoning. Representative examples in Fig. 2e illustrate how the model integrates saliency information and flow pattern analysis to produce faithful explanations alongside its predictions.

Comparison with clinicians

To benchmark our model’s performance against current clinical practice, we invited six clinicians (each with 5–8 years of relevant experience) to independently evaluate a randomly selected subset of 80 cases from the external validation datasets. Each clinician was blinded to the reference standard and model predictions. The evaluation comprised both binary disease classification and detailed subtype discrimination. To ensure a fair comparison, both the AI model and human readers were evaluated under identical conditions, using only color Doppler frames without any accompanying B-mode information. Following this comparative assessment, our model achieved comparable or superior performance (Fig. 2a). For binary classification, both clinicians and our model demonstrated near-perfect diagnostic accuracy. In subtype classification, clinicians exhibited substantial variability; sensitivity for AVSD detection was particularly low in some cases, and performance for HV and FSV classification ranged widely, with certain clinicians approaching chance levels. Notably, our model consistently performed at or above the average level of clinical experts while maintaining robust performance across external validation sets. Detailed individual clinician results are provided in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

AI assistance enhances clinician diagnostic performance

To further investigate the potential of our model to augment clinical decision-making, we extended the comparative study (Section “Comparison with clinicians”) by allowing clinicians to review the model’s predictions and flow-based explanations after their initial independent assessments. Clinicians were informed that the AI outputs were intended as supportive information but might not always be accurate, and were given the option to revise their diagnoses accordingly.

The integration of AI assistance demonstrably improved most clinician diagnostic performance, and did not lead to deterioration in performance for any clinician (Fig. 2d). For binary classification, AI support generally enhanced diagnostic accuracy, reflected by improvements in key metrics such AUROC and sensitivity across the clinicians, with AUROC gains reaching up to 0.088. In the more challenging subtype classification task, AI assistance similarly resulted in improved AUROC for all clinicians, with the most pronounced absolute gain of 0.097, and notable increases in sensitivity, with a maximum improvement of 0.208. Detailed results for each clinician are provided in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. These findings demonstrate that our model, particularly through its provision of transparent flow-based explanations, effectively augments clinician diagnostic performance in the challenging screening for specific fetal cardiac defects in the first trimester.

Discussion

This study presents the first interpretable DL model for first-trimester fetal cardiac assessment using Doppler flow 4CV imaging, enabling early detection of specific and major cardiac anomalies with high accuracy and interpretability. To ensure robust model development and validation, we established the largest and most diverse multicenter cohort to date, comprising 108,521 first-trimester cardiac ultrasound exams from tertiary hospitals across geographically distinct regions of China. This unprecedented dataset underpins the model’s strong performance, scalability, and generalizability across varied clinical environments.

To date, the application of AI in first-trimester fetal cardiac assessment has been scarcely explored. To our knowledge, only one prior study by Ungureanu et al. has proposed a DL-based decision support system using standard 2D cine sweeps acquired during early fetal echocardiography37. However, their work primarily emphasized system design and lacked reporting of performance metrics or clinical validation, thereby limiting its translational impact. In contrast, our study introduces the first empirically validated DL model purpose-build for early CHD screening. The model not only achieved excellent binary classification accuracy—a result that, while potentially attributable to the relative simplicity of the two-class distinction, still reflects its ability to match the near-perfect performance level of human experts—but also approached expert-level performance in subtype classification. Furthermore, it demonstrated strong robustness and generalizability through rigorous validation on multiple independent datasets derived from a large, geographically diverse, multi-center cohort.

This robustness is particularly evident when assessing our model’s performance across different ultrasound imaging platforms. We analyzed the distribution of ultrasound machine types across participating centers (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). Our analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity in equipment types and manufacturers, with each center utilizing different combinations of ultrasound systems. Notably, the external validation sets included data acquired from several ultrasound machines that were not represented in the training dataset. Despite this challenging scenario, the model demonstrated consistent performance without significant degradation compared to internal validation results. This suggests that the model has learned clinically relevant features that are relatively invariant to the technical specifications of different ultrasound systems. The ability to generalize across diverse imaging platforms enhances the clinical applicability of our method, particularly in real-world settings where healthcare facilities often operate with heterogeneous equipment.

It is important to acknowledge that the selection of ultrasound images for automated analysis in first-trimester screening warrants deliberate discussion. First-trimester fetal cardiac screening represents a particularly demanding domain in prenatal imaging, largely due to inherent limitations in image quality at this early gestational stage. It is widely recognized in clinical practice that even highly trained sonographers and fetal cardiologists cannot confidently interpret images with significant acoustic artifacts or poor signal-to-noise ratio. Our decision to apply exclusion criteria—specifically the removal of suboptimal or ambiguous cases—was therefore guided by established diagnostic protocols, wherein such images are typically addressed through repeat transvaginal acquisition, real-time optimization, or follow-up scans in later gestation21,38. This approach aligns with real-world screening workflows and was necessary to ensure reliable identification of subtle Doppler flow patterns within the 4CV, a prerequisite for reproducible and clinically meaningful AI analysis.

Beyond diagnostic performance, the clinical utility of our model lies in its role as a decision support tool that complements, rather than replaces, specialist expertise in first-trimester cardiac screening. Acting as a perceptual aid, the model addresses practical clinical challenges such as time constraints, cognitive burden, and examiner fatigue, while enhancing screening sensitivity39. Our results demonstrate that model assistance can effectively augment clinical assessment, with improvements in diagnostic accuracy as detailed in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5. This assistive capacity holds significant value in busy clinical settings, facilitating more consistent and reliable early detection of CHD.

The enhanced clinical utility of our approach stems from a fundamental shift in focus—from static anatomical structures to dynamic flow patterns captured by Doppler flow imaging. While high-resolution 2D ultrasound remains the gold standard for anatomical diagnosis, its application as a population-level screening tool is limited by technical demands and operator dependency, particularly in early gestation when the fetal heart is small and rapidly beating. To balance clinical utility with practical feasibility, targeted Doppler flow imaging of the 4CV offers a more reproducible and informative alternative, enhancing chamber visualization and delineating inflow jets to support more reliable anatomical interpretation40,41. Doppler flow 4CV imaging also improves discrimination between normal and abnormal cardiac function in the first trimester. Major defects such as tricuspid atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and AVSD can often be identified as early as 11 weeks’ gestation, with reported detection rates exceeding 90% in selected studies21,42. Furthermore, Doppler flow imaging may reveal subtle flow abnormalities (e.g., asymmetry, reduced inflow) in cases where overt structural changes are not yet apparent, such as outflow tract obstructions, thus providing early indicators of evolving cardiac pathology43,44.

A central innovation of our approach lies in its interpretable-by-design architecture, explicitly aligning the model’s decision-making process with established clinical workflows to enhance trust in high-stakes prenatal screening. A persistent barrier to clinical adoption of AI, particularly in sensitive domains such as first-trimester fetal assessment, is the lack of model transparency, which can undermine clinician confidence and impede shared decision-making34,35,36. To address this, our model emulates the stepwise reasoning of expert clinicians: it first evaluates diastolic flow patterns and subsequently integrates these intermediate, clinically meaningful assessments to inform the final classification. This structured approach ensures that the model’s output reflects familiar diagnostic logic, facilitating both transparency and multidisciplinary collaboration. The effectiveness of this alignment is demonstrated through multiple validation metrics: high predictive accuracy in intermediate flow pattern recognition (Table 2), substantial overlap between model attention and clinically relevant cardiac regions (Fig. 2c), and strong concordance with domain knowledge as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6. By mirroring clinical reasoning, the model enables intuitive interpretation and verification of results, ultimately supporting more confident, transparent, and timely decision-making in prenatal care.

Our analysis of specific challenging cases further highlights the model’s clinical utility. In two confirmed HV cases, a substantial proportion of clinicians misclassified the images as normal, despite adequate image quality and optimized Doppler settings. This misjudgment may reflect a clinical tendency to normalize suboptimal findings, particularly in settings where misadjusted pulse repetition frequency (PRF) is common38. Elevated PRF can suppress low-velocity flow, producing asymmetrical patterns that mimic HV45, which clinicians often dismiss as technical artifacts rather than true pathology. Such heuristic-driven tolerance may lead to overlooked abnormalities. In contrast, our model, trained exclusively on standardized, quality-controlled images, correctly identified these anomalies, illustrating its robustness under optimized imaging conditions and its ability to mitigate biases inherent in human interpretation. Another compelling case involved a fetus with a downward-pointing cardiac apex, diagnosed with AVSD. The model correctly identified the defect, while half of the clinicians classified it as normal, likely due to the subtlety of the septal abnormality and the challenging view46. This example highlights the model’s potential to support clinical decision-making in scenarios where fetal positioning or anatomical subtleties compromise human detection. Representative examples are illustrated in Fig. 2e.

From a translational standpoint, the model is well suited for integration into existing prenatal screening workflows. It can be deployed in real time by embedding into ultrasound systems or used post-acquisition via on-device or cloud-based platforms. Importantly, it aligns with current first-trimester screening protocols that already include biometric assessment and cardiac plane acquisition19. As it requires only a single Doppler-enhanced 4CV image, integration is minimally disruptive and requires little additional operator training. This enables adoption in a variety of clinical environments, from high-volume tertiary centers to decentralized or resource-limited settings, enhancing scalability and clinical utility47.

Beyond its immediate diagnostic performance, addressing these technical challenges holds broader implications for healthcare equity in prenatal care. Although simplified scanning protocols and Doppler flow imaging have been proposed to improve early detection, these strategies remain constrained by their dependence on operator expertise and subjective interpretation40. Compounding this issue is the fact that first-trimester fetal cardiac screening is not routinely performed across all clinical settings48. Many centers offer such assessments only for high-risk pregnancies49, while others lack trained personnel to implement first-trimester cardiac evaluations. These systemic limitations collectively contribute to significant inequities in access to early fetal cardiac screening, with underserved populations bearing a disproportionate burden of undetected CHD. Our interpretable, standardized model offers a scalable solution to these challenges by providing consistent, real-time decision support that reduces dependency on specialist availability and subjective interpretation. By empowering frontline providers with reliable diagnostic assistance, this technology holds substantial promise for expanding access to early fetal cardiac screening and promoting global equity in CHD detection.

Despite the model’s overall strong performance and interpretability, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, despite its alignment with standard clinical practice, the application of image quality-based exclusion criteria may introduce a potential selection bias, as image quality assessment can be subjective and vary across institutions or sonographers. Although our model demonstrated strong performance on cases meeting specific quality thresholds, its efficacy may be influenced by inter-site differences in image quality interpretation. Therefore, future studies evaluating the model’s adaptability to diverse clinical settings with varying image inclusion standards would be valuable to further assess its robustness and real-world applicability. Second, our study focused on severe and specific CHD subtypes that hold high clinical significance, as their early identification can substantially influence prenatal decision-making and fetal management. This focus provided the model with clearer and more consistent learning targets, likely enhancing performance compared to studies involving a broader spectrum of CHD subtypes. Importantly, these findings should not be interpreted as providing sufficient evidence for routine implementation of first-trimester fetal cardiac screening, as the results represent optimized performance under limited conditions and do not capture the full spectrum of CHD encountered in practice. Third, classification accuracy was comparatively lower for certain anomaly subtypes, particularly AVSD and HV. Analysis of confusion matrices (Fig. 2b) indicates that these anomalies were frequently confused with FSV, and vice versa. This pattern likely stems from both class imbalance in the training data and inherent hemodynamic overlap among these conditions, which also poses challenges in clinical expert assessment. For example, although AVSD typically presents with a Y-shaped dual inflow, severe cases may exhibit altered hemodynamics resembling a single dominant inflow, mimicking FSV. Such overlapping phenotypic and hemodynamic features are known sources of diagnostic ambiguity in first-trimester screening. The fact that the model reproduces these complexities suggests that its errors reflect intrinsic diagnostic difficulties rather than arbitrary mistakes. Fourth, the model’s current implementation relies on a single, manually selected diastolic frame from the 4CV Doppler clip. Although this approach ensures that the model analyzes the most diagnostically informative phase of the cardiac cycle, the requirement for manual frame selection introduces operator dependency, reduces the level of automation, and may contribute to inter-observer variability. Moreover, reliance solely on the 4CV may limit detection of certain anomalies, such as conotruncal defects, that require additional views for comprehensive evaluation. To address these limitations, future work will focus on incorporating multi-plane analysis to improve comprehensive evaluation, as well as developing an automated frame selection module capable of identifying the optimal diastolic frame based on both cardiac cycle timing and image quality metrics. Incorporating such functionality, potentially through temporal modeling or video-based DL architectures, will be essential for achieving end-to-end automation and enabling seamless integration into the clinical workflow of sonographers. Finally, although the model achieved performance comparable to expert readers for selected tasks, its clinical role should be understood as complementary rather than substitutive. The system is not intended to replace expert judgment in real-world settings, and its practical utility will depend on careful integration into established scanning workflows and further validation across broader populations and scanning conditions.

In conclusion, this study establishes a large-scale, multicenter framework for early AI-assisted fetal cardiac screening based on Doppler flow 4CV imaging. Our interpretable model demonstrated robust detection of specific and major cardiac anomalies during the critical 11–14 weeks’ gestational window. To further enhance diagnostic accuracy, we have initiated the prospective collection of real-time dual-modality datasets combining B-mode and Doppler flow imaging, aiming to systematically assess the independent and complementary contributions of structural and flow information. Future directions also include expanding sample diversity and validating performance across broader clinical settings to advance scalable, equitable prenatal care.

Methods

Data collection

The study enrolled data from seven tertiary referral centers across China. These included four large-scale maternity or women’s and children’s specialty hospitals: Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital (BOGH), Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAH), Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care (CH), Northwest Women’s and Children’s Hospital (NWCH), and two major general hospitals with prominent obstetrics and gynecology departments: Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (XH) and the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (TAHZU), as well as PLA General Hospital (PLAH), a comprehensive medical center with a high-volume obstetric service. The annual delivery volumes across these centers range from approximately 10,000 to over 20,000 births. Together, they serve diverse populations spanning northern, central, southern, and western China, ensuring the geographic diversity and representativeness of the dataset. We retrospectively collected Doppler flow 4CV images from first-trimester (11–14 weeks) fetal cardiac ultrasounds. Depending on local protocols and equipment settings, both color and power Doppler modes were used to visualize intracardiac flow. Normal cases were confirmed as structurally normal in both second-trimester follow-up and postnatal assessments. Abnormal cases were confirmed by expert consensus based on transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound findings, supplemented by selective fetal autopsy when available. Cardiac defects that could not be reliably diagnosed from diastolic Doppler flow 4CV imaging, such as small ventricular septal defects, tricuspid valve dysplasia, or great vessel abnormalities, rare subtypes with insufficient sample size were excluded. Abnormal cases were categorized into three specific and distinguishable subtypes based on diastolic Doppler flow 4CV imaging features: (1) AVSD - single Y-shaped atrioventricular inflow pattern; (2) HV - asymmetry or underdevelopment ventricles with unequal dual inflow. (3) FSV - comprising mitral or tricuspid atresia and classic single-ventricle physiology, presenting as a single dominant inflow.

Images were screened by two senior fetal sonographers; quality control was performed by a third expert. Eligible images were required to display a centered and appropriately magnified 4CV with clearly delineated intracardiac blood flow. Non-standard images (e.g., ectopia cordis, severe shadowing) and poor-quality scans (e.g., due to high maternal BMI, abdominal scarring, or Doppler artifacts) were excluded. The final dataset included 2232 images from 453 abnormal fetuses. A 3:1 matching strategy of normal to abnormal cases was adopted to enhance statistical power and mitigate class imbalance, a common limitation in developing AI models for rare conditions such as CHD. This approach facilitated robust model training while maintaining feasibility within a limited sample of abnormal cases. Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria and image allocation strategy are shown in Fig. 3.

Data were collected from seven tertiary centers: Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital (BOGH), Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAH), Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (XH), Changsha Hospital for Maternal and Child Health Care (CH), Northwest Women’s and Children’s Hospital (NWCH), the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (TAHZU), and PLA General Hospital (PLAH). The training and validation sets were split at the case level (80 %/20 %) to prevent data leakage from different images of the same case. Cases excluded due to “not readily identifiable on diastolic-phase 4CV” included conditions such as small ventricular septal defects, tricuspid valve dysplasia, or great vessel abnormalities presenting with a normal 4CV appearance. “Incomplete or non-standard 4CV” referred to instances of severe shoulder shadowing, ectopia cordis, or views deemed non-standard by expert review. “Suboptimal quality” exclusions comprised images with insufficient magnification, poor acoustic windows (e.g., due to thick abdominal wall or scars), or excessive Doppler overflow or aliasing. 4CV = four-chamber view.

Three experienced fetal sonologists annotated intracardiac blood flow using LabelMe software. Normal cases had left/right inflows labeled as “left heart”/“right heart”; abnormal cases were labeled as “single heart” or dual inflows depending on presentation. Mask annotation consistency was calibrated using 150 test images and reviewed by a senior expert to ensure accuracy and uniformity. Each image was further evaluated for three flow patterns: (1) number of filled chambers (1–4), (2) atrioventricular flow number (single/two), and (3) flow symmetry (equal/unequal). Discrepancies were resolved by expert consensus. A random subset of 500 images was used to assess annotation agreement (Supplementary Table 1).

The dataset was structured to enable comprehensive evaluation of diagnostic capability at two clinical decision levels. For binary classification, we allocated data from three hospitals for model development, with 5254 images for training and 1534 for validation. The remaining data were stratified into external validation cohorts by hospital origin: external validation set 1 (n = 833), external validation set 2 (n = 136; combined data from three different hospitals), and external validation set 3 (n = 305; prospectively collected validation data). For the more granular subtype classification task, we combined data from four hospitals to enable a more robust evaluation, resulting in a training set of 2372 cases, a validation set of 614 cases, and an external validation set of 1254 cases. Detailed characteristics of these datasets are presented in Table 3.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee at each participating center. Approval was granted by the ethics committee at BOGH (No. 2022-KY-097-03), GZAH (No. 20194), XH (No. 202211714), CH (No. CSSFYBJYEC-SOP-005-F07V1.0), TAHZU (No. 2022-099), PLAH (No. S2022-707-01), and NWCH (No. 2025-018-01). Written informed consent was obtained from participants at all centers except NWCH, where the requirement was waived by the local ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the data collection. The study has been registered on Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2400086975) and follows the TRIPOD reporting guidelines.

Data preprocessing

All echocardiographic images were subjected to a standardized preprocessing pipeline to ensure uniformity across the multi-institutional dataset. Initially, contours were delineated using masks to identify the cardiac region in the original images; a square crop was applied with a side length equivalent to twice the maximum of the contour’s length and width, centered at the contour centroid, thereby isolating the heart area and minimizing interference from extraneous information. Images were then uniformly resized to 256 × 256 pixels using bilinear interpolation. Statistical analysis of the training dataset revealed mean pixel values of [0.325, 0.325, 0.325] and standard deviations of [0.229, 0.229, 0.229]. During the training phase, several data augmentation techniques were implemented to enhance model robustness, including grayscale conversion, horizontal and vertical flipping, Gaussian blur, and random resized cropping to 224 × 224 pixels. The probability of applying Gaussian blur was set at 0.2, while other augmentations were applied with a probability of 0.5. Test samples were directly resized to 224 × 224 pixels without augmentation. All images underwent normalization using the aforementioned statistical parameters to stabilize training and improve generalization capability. Following standard machine learning practice, the dataset was divided into training and validation sets at a ratio of 4:1, with stratification performed at the patient level to prevent data leakage that could occur if images from the same patient appeared in both sets. This configuration balances the need for sufficient training data with adequate validation set size for reliable performance assessment. External validation was conducted using completely independent samples from different hospitals. The detailed distribution of the dataset is presented in Table 3. In this study, we employed a centralized processing strategy to ensure consistency and standardization of data from all participating hospitals. Specifically, each hospital was responsible for collecting raw image data. These datasets were then collated and centrally processed. This centralized workflow included all critical steps such as image annotation and preprocessing, which were performed uniformly by a single team using a consistent set of protocols. We adopted this approach to minimize inter-site variability that could arise from different local processing pipelines and to ensure a uniform quality standard for the final dataset used in our analysis.

Data standardization and interoperability

All processed images for public release were saved in lossless PNG format to preserve image fidelity while removing embedded patient-identifying information. To maximize interoperability, we provide metadata in two complementary formats. A simplified CSV file contains essential fields for each image: unique image ID, de-identified patient ID, maternal age, ultrasound device, hospital center, diagnostic outcome, and expert-annotated flow pattern characteristics. For advanced integration, we structured comprehensive metadata as JSON-based resources following the FHIR standard (http://hl7.org/fhir/R5/). Clinical terminology within these resources, where applicable, has been mapped to SNOMED CT (https://browser.ihtsdotools.org/) to ensure semantic consistency.

Model architecture

The framework implements an end-to-end trainable architecture that transforms raw diastolic Doppler flow 4CV imaging into diagnostic predictions, closely aligned with the diagnostic reasoning process of fetal cardiologists. In contrast to conventional “black-box” DL models that rely on high-dimensional features which are hard to interpret, our framework enforces a transparent diagnostic pathway: from image-level representations to flow pattern extraction, and ultimately to diagnostic outputs. This design ensures that each prediction is supported by interpretable and faithful explanations, thereby enhancing the trustworthiness and clinical applicability of the automated screening process, which is a critical requirement for prenatal cardiac assessment. The framework consists of four main components, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1. First, a structure-guided feature learning module incorporates cardiac masks drawn by clinicians through an IoU loss, focusing the model’s attention on relevant cardiac structures and improving diagnostic robustness. Then, a flow pattern analysis module projects image features extracted by image encoders to three predefined diastolic flow patterns, supervised by corresponding expert-annotated labels. Furthermore, a flow-based anomaly prediction component implements a hierarchical screening strategy, efficiently filtering normal cases while flagging potential anomalies for detailed classification, aligning with standard clinical workflows. Finally, the flow-based disease prediction module generates final predictions solely based on the learned diastolic flow pattern features using a cross-attention mechanism, ensuring that all diagnostic decisions are traceable to specific anatomical and functional observations. The detailed technical implementation of each component is described in Sections "Technical Details" and "Hyperparameters for Model Training"

Outcome

The primary objective was to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the DL model for detecting CHD from first-trimester ultrasound imaging, with the AUROC as the prespecified primary endpoint, complemented by sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score. Secondary objectives focused on model interpretability, assessed through two complementary approaches: diastolic flow pattern prediction consistency with expert annotations, and spatial alignment of saliency maps with expert-annotated cardiac masks.

Statistical analysis

The dataset size was determined by the availability of eligible ultrasound scans from the participating centers and was not derived from a formal power calculation. We calculated diagnostic performance metrics including AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score using the TorchMetrics library (version 1.4.2). We employed non-parametric bootstrap resampling with 10,000 iterations to generate 95 % confidence intervals for all reported metrics. Model interpretability was quantitatively evaluated through diastolic flow pattern prediction accuracy using the F1 score, analyzed as a multilabel classification task, and spatial correspondence between model-generated saliency maps and expert-annotated cardiac structures using IoU metrics. All statistical analyses were performed using Python 3.12.4.

Technical details

For an echocardiographic image x, our model f first predicts flow pattern results yf (where \({y}_{f}^{1}\), \({y}_{f}^{2}\), and \({y}_{f}^{3}\) correspond to chamber number, flow number, and flow symmetry, respectively). Based on these flow pattern results, the model directly determines whether the sample is abnormal. If an abnormality is detected, the model further predicts the anomaly subtype yd using the flow pattern predictions and related information. This design ensures that the model’s anomaly detection and subtype classification align with clinical diagnostic procedures, thus guaranteeing the interpretability and transparency of the model’s decision-making process.

For the structure guided feature learning module, the initial step involves extracting robust image features from the echocardiographic image using a pretrained vision transformer (ViT) as the image encoder. The ViT50 is one of the most widely adopted encoders for image feature extraction in image classification tasks, owing to its ability to capture long-range dependencies and hierarchical representations through self-attention mechanisms. This process can be mathematically represented as:

where Ti denotes the extracted image features, and di is the dimensionality of these features, which is determined by the specific ViT architecture employed. To mitigate the risk of the model learning irrelevant or spurious features that could lead to incorrect associations—such as focusing on non-cardiac regions—we impose a structural constraint during training. Specifically, we compute an IoU loss between the feature map H generated by the encoder and a predefined mask M that highlights cardiac regions of interest. The loss is formulated as:

This loss encourages the model to prioritize features aligned with anatomically relevant areas, such as the heart chambers and valves, thereby enhancing the reliability of downstream predictions. By integrating this constraint, the framework not only improves feature localization but also supports clinical interpretability, as the model’s attention is guided to regions that correspond to key diagnostic indicators in echocardiography.

For the flow pattern analysis, the extracted image features Ti are projected into a flow representation space through our constructed flow encoder fh, yielding three feature representations: \({T}_{f}^{1},{T}_{f}^{2},{T}_{f}^{3}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{f}}\) (where df is the dimensionality of the flow features, a hyperparameter we set). These representations correspond to chamber number, flow number, and flow symmetry, respectively. The flow encoder fh consists of three parallel modules, each comprising a linear layer followed by a ReLU activation function. This process can be mathematically formulated as:

where \({W}_{k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{f}\times {d}_{i}}\) are learnable weight matrices and \({b}_{k}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{d}_{f}}\) are bias terms. Subsequently, these flow features are passed through separate linear classifiers to obtain the flow pattern prediction results \({\widehat{y}}_{f}\):

where σ represents the sigmoid activation function, \({W}_{k}^{{\prime} }\) are the classifier weight matrices, and \({b}_{k}^{{\prime} }\) are the bias terms. The predicted flow patterns \({\widehat{y}}_{f}\) are compared with the ground truth flow pattern labels yf using Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) loss, denoted as \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{F}\):

In flow-based anomaly prediction, if all flow pattern predictions are normal (chamber number ≥2, flow number =2, flow symmetry is equal), the sample is directly classified as Normal. If any flow pattern prediction indicates an abnormality, the sample undergoes further subtype screening, which will be elaborated in subsequent sections. This module ensures that anomaly diagnosis is entirely based on flow patterns, consistent with professional medical diagnostic procedures. The flow pattern predictions can faithfully explain the anomaly detection results, allowing clinicians to rapidly verify them and effectively improving diagnostic efficiency.

In flow-based subtype classification, considering that identical flow patterns may correspond to different anomaly subtypes, and the same anomaly type might present different flow patterns, we cannot simply classify subtypes based on the flow pattern predictions. To maintain interpretability, we also need to ensure by design that disease prediction results are entirely derived from flow pattern information. Following51,52, we employ a cross-attention mechanism for classification. First, we create N learnable disease embeddings \({T}_{d}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{N\times {d}_{f}}\) with the same dimensionality as the flow pattern feature representations, to encode disease-related information for subsequent subtype classification. Next, Td serves as queries, while the concatenated flow pattern features \({T}_{f}=[{T}_{f}^{1},{T}_{f}^{2},{T}_{f}^{3}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3\times {d}_{f}}\) serve as keys and values. This can be formulated as:

The resulting disease logits are compared with disease labels using Cross Entropy (CE) loss, denoted as \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{D}\):

We now define the overall loss function. In the binary classification task, the model’s final objective function is:

In the subtype classification task, the final objective function is:

where α, β, and γ are hyperparameters that adjust the weights of different loss components.

Finally, we describe the process of model explanation generation. According to (8), for an input image x, the logit for disease i is the weighted sum of keys and values, with weights determined by the similarity between disease embedding i and the keys. These attention weights represent the contribution of specific flow patterns to the prediction result, ensuring the faithfulness of flow-based explanations. This design provides reliable and effective information for clinicians to understand and assess the model’s predictions.

Hyperparameters for model training

All the experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. When training the binary classification model, the maximum number of training epochs was set to 100, with a batch size of 32. We employed the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of 5e − 5, and weight decay of 1e − 4. A dynamic learning rate adjustment strategy was implemented wherein the learning rate was reduced by a factor of 0.5 when the validation loss showed no improvement for five consecutive epochs, with a minimum learning rate threshold of 1e − 6. To facilitate stable early-stage training, we incorporated a warmup mechanism for the first 100 optimization steps, during which the learning rate linearly increased from zero to the initial value. Training stability was further enhanced through an early stopping mechanism that terminated training if the validation loss failed to decrease for ten consecutive epochs, and gradient clipping at a value of 1.0 to prevent gradient explosions and ensure numerical stability. For the image encoding component, we utilized a ViT-B/16 architecture pretrained on ImageNet 1K dataset. To address overconfidence issues and mitigate overfitting, we implemented logit normalization53 with a temperature parameter of 0.01. The dimensionality of flow pattern features df was configured at 512, with weighting parameters α and β both set to 1.0. The subtype classification model was fine-tuned from the pretrained weights of the binary classification model to leverage learned representations. The initial learning rate was slightly reduced to 3e − 5 to ensure stable fine-tuning. we implemented a cosine annealing scheduler with warm restarts to dynamically modulate the learning rate throughout training. This scheduler initially decreased the learning rate following a cosine function over 6 epochs, then reset i to the inittial value and repeated the cycle with progressively longer periods, doubling the cycle length after each restart. The minimum learning rate was set to 3e − 6. Consistent with the binary classification model training, we maintained the maximum number of epochs at 100, batch size of 32, AdamW optimizer with weight decay of 1e − 4, early stopping mechanism with patience of ten epochs, gradient clipping at 1.0, and logit normalization with temperature parameter of 0.01. The weighting coefficients α, β, and β were configured at 0.8, 0.2, and 1.0 respectively, to appropriately balance the contributions from different feature components in the multi-class prediction framework.

Data availability

The data will be available immediately following the publication with no end date. The researchers who apply to access the data should provide a methodologically sound proposal to qingqingwu@ccmu.edu.cn to gain access, and they must sign a data access agreement during the application.

Code availability

The code to reproduce the results can be accessed at https://github.com/Sorades/FTCHD.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 455–463 (2019).

Van, dL. D. et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 58, 2241–2247 (2011).

Miles, K. G. et al. Mental health conditions among children and adolescents with congenital heart disease: a danish population-based cohort study. Circulation 148, 1381–1394 (2023).

Amdani, S. et al. Evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 150, e33–e50 (2024).

Bai, Z. et al. The global, regional, and national patterns of change in the burden of congenital birth defects, 1990–2021: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2021 and forecast to 2040. Eclinicalmedicine 77, 102873 (2024).

Nurmi, M. O., Pitkänen-Argillander, O., Räsänen, J. & Sarkola, T. Accuracy of fetal echocardiography diagnosis and anticipated perinatal and early postnatal care in congenital heart disease in mid-gestation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 101, 1112–1119 (2022).

Haberer, K. et al. Accuracy of fetal echocardiography in defining anatomic details: a single-institution experience over a 12-year period. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 35, 762–772 (2022).

Freud, L. R. & Simpson, L. L. Fetal cardiac screening: 1st trimester and beyond. Prenat. Diagn. 44, 679–687 (2024).

Jin, S. C. et al. Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nat. Genet. 49, 1593–1601 (2017).

Dovjak, G. O. et al. Abnormal extracardiac development in fetuses with congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78, 2312–2322 (2021).

Zaidi, S. & Brueckner, M. Genetics and genomics of congenital heart disease. Circ. Res. 120, 923–940 (2017).

Norton, M. E., Biggio, J. R., Kuller, J. A. & Blackwell, S. C. The role of ultrasound in women who undergo cell-free DNA screening. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216, B2–B7 (2017).

Donofrio, M. T. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. Circulation 129, 2183–2242 (2014).

Corroenne, R. et al. Postnatal outcome following fetal aortic valvuloplasty for critical aortic stenosis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 64, 339–347 (2024).

Jaeggi, E., Renaud, C., Ryan, G. & Chaturvedi, R. Intrauterine therapy for structural congenital heart disease: Contemporary results and canadian experience. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 26, 639–646 (2016).

De Jong, A., Dondorp, W. J., Frints, S. G. M., De Die-Smulders, C. E. M. & De Wert, G. M. W. R. Advances in prenatal screening: the ethical dimension. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 657–663 (2011).

Harris, K. W., Brelsford, K. M., Kavanaugh-McHugh, A. & Clayton, E. W. Uncertainty of prenatally diagnosed congenital heart disease: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e204082 (2020).

Nakao, M. et al. Association between parental decisions regarding abortion and severity of fetal heart disease. Sci. Rep. 14, 15055 (2024).

Bilardo, C. M. et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): performance of 11–14-week ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 127–143 (2023).

Moon-Grady, A. J. et al. Guidelines and recommendations for performance of the fetal echocardiogram: an update from the american society of echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 36, 679–723 (2023).

Karim, J. N., Bradburn, E., Roberts, N., Papageorghiou, A. T. & Study, ftA. First-trimester ultrasound detection of fetal heart anomalies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 11–25 (2022).

Bak, G. S. et al. Detection of fetal cardiac anomalies: cost-effectiveness of increased number of cardiac views. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 55, 758–767 (2020).

Orlandi, E., Rossi, C., Perino, A., Musicò, G. & Orlandi, F. Simplified first-trimester fetal cardiac screening (four chamber view and ventricular outflow tracts) in a low-risk population. Prenat. Diagn. 34, 558–563 (2014).

Kocak, B., Baessler, B., Cuocolo, R., Mercaldo, N. & Pinto dos Santos, D. Trends and statistics of artificial intelligence and radiomics research in radiology, nuclear medicine, and medical imaging: bibliometric analysis. Eur. Radio. 33, 7542–7555 (2023).

Adedinsewo, D. A. et al. Artificial intelligence guided screening for cardiomyopathies in an obstetric population: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Nat. Med. 30, 2897–2906 (2024).

Wang, Y.-R. J. et al. Screening and diagnosis of cardiovascular disease using artificial intelligence-enabled cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Med. 30, 1471–1480 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Self-improving generative foundation model for synthetic medical image generation and clinical applications. Nat. Med. 31, 609–617 (2025).

Sun, L. et al. A novel artificial intelligence model for measuring fetal intracranial markers during the first trimester based on two-dimensional ultrasound image. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 167, 1090–1100 (2024).

Horgan, R., Nehme, L. & Abuhamad, A. Artificial intelligence in obstetric ultrasound: a scoping review. Prenat. Diagn. 43, 1176–1219 (2023).

Xie, H. et al. Using deep-learning algorithms to classify fetal brain ultrasound images as normal or abnormal. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 56, 579–587 (2020).

Luo, D. et al. A prenatal ultrasound scanning approach: one-touch technique in second and third trimesters. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 47, 2258–2265 (2021).

Arnaout, R. et al. An ensemble of neural networks provides expert-level prenatal detection of complex congenital heart disease. Nat. Med. 27, 882–891 (2021).

Liastuti, L. D. & Nursakina, Y. Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence models in detecting congenital heart disease in the second-trimester fetus through prenatal cardiac screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 12, 1473544 (2025).

Salih, A. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence and cardiac imaging: toward more interpretable models. Circ.: Cardiovasc. Imaging 16, e014519 (2023).

Lipton, Z. C. The doctor just won’t accept that! Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1711.08037 (2017).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 206–215 (2019).

Ungureanu, A. et al. Learning deep architectures for the interpretation of first-trimester fetal echocardiography (LIFE) - a study protocol for developing an automated intelligent decision support system for early fetal echocardiography. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23, 20 (2023).

Allary, M. & Quarello, E. Comment je fais… Optimiser mes réglages Doppler pour une analyse du coeur foetal au premier trimestre de la grossesse ?. Gynécol. Obstét. Fertil. Sénol. 52, 720–724 (2024).

Vorster, M., Casmod, Y. & Hajat, A. Sonographers’ experiences in coping with stress in the workplace in gauteng, South Africa. Radiography 31, 102960 (2025).

Quarello, E., Lafouge, A., Fries, N., Salomon, L. J. & Cfef, T. Basic heart examination: feasibility study of first-trimester systematic simplified fetal echocardiography. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 49, 224–230 (2017).

Yang, S. et al. Evaluation of first-trimester ultrasound screening strategy for fetal congenital heart disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 65, 478–486 (2025).

Kołodziejski, M. et al. Early fetal cardiac scan as an element of the sonographic first-trimester screening. Folia Med. Cracov. 60, 17–26 (2020).

Rieder, W., Eperon, I. & Meagher, S. Congenital heart anomalies in the first trimester: from screening to diagnosis. Prenat. Diagn. 43, 889–900 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Echocardiographic follow-up and pregnancy outcome of fetuses with cardiac asymmetry at 18–22 weeks of gestation. Prenat. Diagn. 34, 900–907 (2014).

Bottelli, L., Franzè, V., Tuo, G., Buffelli, F. & Paladini, D. Prenatal detection of congenital heart disease at 12-13 gestational weeks: detailed analysis of false-negative cases. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 577–586 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Efficacy of atrioventricular valve regurgitation in the first trimester for the diagnosis of atrioventricular septal defect. J. Clin. Ultrasound 52, 405–414 (2024).

Gomes, R. G. et al. AI system for fetal ultrasound in low-resource settings. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.10139 (2022).

Esteves, K. M. et al. The value of detailed first-trimester ultrasound in the era of noninvasive prenatal testing. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 229, 326.e1–326.e6 (2023).

Turan, S., Asoglu, M. R., Ozdemir, H., Seger, L. & Turan, O. M. Accuracy of the standardized early fetal heart assessment in excluding major congenital heart defects in high-risk population: A single-center experience. J. Ultrasound Med. 41, 961–969 (2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929 (2021).

Rigotti, M., Miksovic, C., Giurgiu, I., Gschwind, T. & Scotton, P. Attention-based interpretability with concept transformers. In Proc. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent.https://openreview.net/forum?id=kAa9eDS0RdO (2021).

Wen, C., Ye, M., Li, H., Chen, T. & Xiao, X. Concept-based lesion aware transformer for interpretable retinal disease diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Med. Imag. 44, 57–68 (2025).

Wei, H. et al. Mitigating neural network overconfidence with logit normalization. In Proc. Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 23631–23644 (PMLR, 2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants 2022YFC2703300, 2022YFC2703301, and 2023YFC2705700 from the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W., B.D. and M.Y. accessed and verified the data and take responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: W.L., C.W., H.L., S.Y., Q.W., B.D. and M.Y. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: W.L., C.W., H.L. and S.Y. Drafting of the manuscript: W.L., C.W., H.L., and S.Y. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: W.L., C.W., H.L., S.Y., Q.W., B.D. and M.Y. Statistical analysis: W.L., C.W., H.L. and S.Y. Obtained funding: Q.W. and B.D. Administrative, technical, or material support: K.S., H.Y., H.L., H.X., X.G., S.Z., Z.Y. and Q.W. Supervision: Q.W., B.D. and M.Y. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, W., Wen, C., Li, H. et al. An interpretable deep learning model for first-trimester fetal cardiac screening. npj Digit. Med. 9, 43 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02217-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02217-6