Abstract

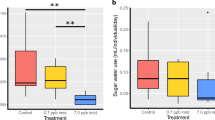

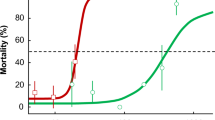

Bees provide crucial pollination services for crop cultivation, contributing billions of dollars to the global agricultural economy. However, exposure to pesticides such as neonicotinoids represents a major problem for bee health, necessitating strategies that can improve agricultural sustainability and pollinator health. Here we report a simple and scalable solution, through ingestible hydrogel microparticles (IHMs), which can capture neonicotinoids in vitro and in the bee gastrointestinal tract to mitigate the harmful effects of pesticides. Using the common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) as a model species and the neonicotinoid imidacloprid, we demonstrated by means of lethal and sublethal assays the substantial benefits of IHM treatments. Under lethal exposure of imidacloprid, bumblebees that received IHM treatment exhibited a 30% increase in survival relative to groups without IHM treatment. After a sublethal exposure of 5 ng, IHM treatment resulted in improved feeding motivation and a 44% increase in the number of bees that engaged in locomotor activity. Wingbeat frequency was significantly lower after a single 5 or 10 ng imidacloprid dose; however, IHM treatment improved wingbeat frequency. Overall, the IHMs improved bumblebee health, and with further optimization have the potential to benefit apiculture and reduce risk during crop pollination by managed bees.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Wingbeat frequency videos were captured using a high-speed camera, which resulted in the raw data files being exceedingly large; therefore, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Videos acquired during locomotion studies can be found at https://github.com/julia-caserto/Bee-Locomotion-Analysis. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code used to analyze locomotion videos can be found at https://github.com/julia-caserto/Bee-Locomotion-Analysis.

References

Klein, A. M. et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Biol. Sci. 274, 303–313 (2007).

Porto, R. G. et al. Pollination ecosystem services: a comprehensive review of economic values, research funding and policy actions. Food Secur. 12, 1425–1442 (2020).

Bruckner, S. et al. A national survey of managed honey bee colony losses in the USA: results from the Bee Informed Partnership for 2017–18, 2018–19 and 2019–20. J. Apic. Res. 62, 429–443 (2023).

Bartomeus, I. et al. Historical changes in northeastern US bee pollinators related to shared ecological traits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4656–4660 (2013).

LeCroy, K. A., Savoy-Burke, G., Carr, D. E., Delaney, D. A. & Roulston, T. H. Decline of six native mason bee species following the arrival of an exotic congener. Sci. Rep. 10, 18745 (2020).

Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C. & Rotheray, E. L. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides and lack of flowers. Science 347, 1255957 (2015).

Graham, K. K. et al. Identities, concentrations and sources of pesticide exposure in pollen collected by managed bees during blueberry pollination. Sci. Rep. 11, 16857 (2021).

Graham, K. K. et al. Pesticide risk to managed bees during blueberry pollination is primarily driven by off-farm exposures. Sci. Rep. 12, 7189 (2022).

McArt, S. H., Fersch, A. A., Milano, N. J., Truitt, L. L. & Böröczky, K. High pesticide risk to honey bees despite low focal crop pollen collection during pollination of a mass blooming crop. Sci. Rep. 7, 46554 (2017).

Krupke, C. H., Hunt, G. J., Eitzer, B. D.,Andino, G. & Given, K. Multiple routes of pesticide exposure for honey bees living near agricultural fields. PLoS ONE 7, e29268 (2012).

Pettis, J. S. et al. Crop pollination exposes honey bees to pesticides which alters their susceptibility to the gut pathogen Nosema ceranae. PLoS ONE 8, e70182 (2013).

Stanley, D. A. et al. Neonicotinoid pesticide exposure impairs crop pollination services provided by bumblebees. Nature 528, 548–550 (2015).

Whitehorn, P. R., O’Connor, S., Wackers, F. L. & Goulson, D. Neonicotinoid pesticide reduces bumble bee colony growth and queen production. Science 336, 351–352 (2012).

Deguine, J.-P. et al. Integrated pest management: good intentions, hard realities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 41, 38 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Pollen-inspired enzymatic microparticles to reduce organophosphate toxicity in managed pollinators. Nat. Food 2, 339–347 (2021).

Camp, A. A. & Lehmann, D. M. Impacts of neonicotinoids on the bumble bees Bombus terrestris and Bombus impatiens examined through the lens of an adverse outcome pathway framework. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 40, 309–322 (2021).

Liu, G. Y., Ju, X. L. & Cheng, J. Selectivity of Imidacloprid for fruit fly versus rat nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by molecular modeling. J. Mol. Model. 16, 993–1002 (2010).

Grünewald, B. & Siefert, P. Acetylcholine and its receptors in honeybees: involvement in development and impairments by neonicotinoids. Insects 10, 420 (2019).

Alkassab, A. T. & Kirchner, W. H. Sublethal exposure to neonicotinoids and related side effects on insect pollinators: honeybees, bumblebees and solitary bees. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 124, 1–30 (2017).

Gregorc, A. et al. Effects of coumaphos and imidacloprid on honey bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) lifespan and antioxidant gene regulations in laboratory experiments. Sci. Rep. 8, 15003 (2018).

Wu, Y.-Y. et al. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on targeting muscle and ribosomal protein related genes in the honey bee Apis mellifera L. Sci. Rep. 7, 15943 (2017).

Yao, J., Zhu, Y. C. & Adamczyk, J. Responses of honey bees to lethal and sublethal doses of formulated clothianidin alone and mixtures. J. Econ. Entomol. 111, 1517–1525 (2018).

Tasman, K., Hidalgo, S., Zhu, B., Rands, S. A. & Hodge, J. J. L. Neonicotinoids disrupt memory, circadian behaviour and sleep. Sci. Rep. 11, 2061 (2021).

He, B. et al. Imidacloprid activates ROS and causes mortality in honey bees (Apis mellifera) by inducing iron overload. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 3, 112709 (2021).

Xu, X. et al. Neonicotinoids: mechanisms of systemic toxicity based on oxidative stress-mitochondrial damage. Arch. Toxicol. 96, 1493–1520 (2022).

Imidacloprid: Proposed Interim Registration Review Decision. Case Number 7605 (EPA, 2020); www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/documents/imidacloprid_pid_signed_1.22.2020.pdf

Klingelhöfer, D., Braun, M., Brüggmann, D. & Groneberg, D. A. Neonicotinoids: a critical assessment of the global research landscape of the most extensively used insecticide. Environ. Res. 213, 113727 (2022).

Hirata, K., Jouraku, A., Kuwazaki, S., Kanazawa, J. & Iwasa, T. The R81T mutation in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor of Aphis gossypii is associated with neonicotinoid insecticide resistance with differential effects for cyano- and nitro-substituted neonicotinoids. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 143, 57–65 (2017).

Sahoo, T. R. & Prelot, B. in Nanomaterials for the Detection and Removal of Wastewater Pollutants (eds Bonelli, B. et al.) 161–222 (Elsevier, 2020).

Azpiazu, C. et al. Chronic oral exposure to field-realistic pesticide combinations via pollen and nectar: effects on feeding and thermal performance in a solitary bee. Sci. Rep. 9, 13770 (2019).

Muth, F., Gaxiola, R. L. & Leonard, A. S. No evidence for neonicotinoid preferences in the bumblebee Bombus impatiens. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191883 (2020).

Parmezan, A. R. S., Souza, V. M. A., Žliobaitė, I. & Batista, G. E. A. P. A. Changes in the wing-beat frequency of bees and wasps depending on environmental conditions: a study with optical sensors. Apidologie 52, 731–748 (2021).

Santoyo, J., Azarcoya, W., Valencia, M., Torres, A. & Salas, J. J. P. A. Frequency analysis of a bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) wingbeat. Pattern Anal. Applic. 19, 487–493 (2016).

Panziera, D., Requier, F., Chantawannakul, P., Pirk, C. W. W. & Blacquière, T. The diversity decline in wild and managed honey bee populations urges for an integrated conservation approach. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, 767950 (2022).

Ward, L. T. et al. Pesticide exposure of wild bees and honey bees foraging from field border flowers in intensively managed agriculture areas. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154697 (2022).

Peng, Y.-S. & Marston, J. M. Filtering mechanism of the honey bee proventriculus. Physiol. Entomol. 11, 433–439 (1986).

Sambe, H., Hoshina, K., Moaddel, R., Wainer, I. W. & Haginaka, J. Uniformly-sized, molecularly imprinted polymers for nicotine by precipitation polymerization. J. Chromatogr. A 1134, 88–94 (2006).

Chen, J. et al. Dummy template surface molecularly imprinted polymers based on silica gel for removing imidacloprid and acetamiprid in tea polyphenols. J. Sep. Sci. 43, 2467–2476 (2020).

Kumar, N., Narayanan, N. & Gupta, S. Application of magnetic molecularly imprinted polymers for extraction of imidacloprid from eggplant and honey. Food Chem. 255, 81–88 (2018).

Wang, X., Mu, Z., Liu, R., Pu, Y. & Yin, L. Molecular imprinted photonic crystal hydrogels for the rapid and label-free detection of imidacloprid. Food Chem. 141, 3947–3953 (2013).

Russell, A. L., Morrison, S. J., Moschonas, E. H. & Papaj, D. R. Patterns of pollen and nectar foraging specialization by bumblebees over multiple timescales using RFID. Sci. Rep. 7, 42448 (2017).

Marletto, F., Patetta, A. & Manino, A. Laboratory assessment of pesticide toxicity to bumblebees. Bull. Insectol. 56, 159–164 (2003).

Chen, Y. R., Tzeng, D. T. W. & Yang, E. C. Chronic effects of imidacloprid on honey bee worker development—molecular pathway perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11835 (2021).

Démares, F. J. et al. Honey bee (Apis mellifera) exposure to pesticide residues in nectar and pollen in urban and suburban environments from four regions of the United States. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 41, 991–1003 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Chronic exposure to field-realistic doses of imidacloprid resulted in biphasic negative effects on honey bee physiology. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 144, 103759 (2022).

Sampson, B. et al. Sensitivity to imidacloprid insecticide varies among some social and solitary bee species of agricultural value. PLoS ONE 18, e0285167 (2023).

Gradish, A. E. et al. Comparison of pesticide exposure in honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae): implications for risk assessments. Environ. Entomol. 48, 12–21 (2018).

Paus-Knudsen, J. S., Sveinsson, H. A., Grung, M., Borgå, K. & Nielsen, A. The neonicotinoid imidacloprid impairs learning, locomotor activity levels and sucrose solution consumption in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 42, 1337–1345 (2023).

Lambin, M., Armengaud, C., Raymond, S. & Gauthier, M. Imidacloprid-induced facilitation of the proboscis extension reflex habituation in the honeybee. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 48, 129–134 (2001).

Lin, Y. C., Lu, Y. H., Tang, C. K., Yang, E. C. & Wu, Y. L. Honey bee foraging ability suppressed by imidacloprid can be ameliorated by adding adenosine. Environ. Pollut. 332, 121920 (2023).

Switzer, C. M. & Combes, S. A. The neonicotinoid pesticide, imidacloprid, affects Bombus impatiens (bumblebee) sonication behavior when consumed at doses below the LD50. Ecotoxicology 25, 1150–1159 (2016).

Combes, S. A., Gagliardi, S. F., Switzer, C. M. & Dillon, M. E. Kinematic flexibility allows bumblebees to increase energetic efficiency when carrying heavy loads. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay3115 (2020).

David, A. et al. Widespread contamination of wildflower and bee-collected pollen with complex mixtures of neonicotinoids and fungicides commonly applied to crops. Environ. Int. 88, 169–178 (2016).

Schuhmann, A. & Scheiner, R. A combination of the frequent fungicides boscalid and dimoxystrobin with the neonicotinoid acetamiprid in field-realistic concentrations does not affect sucrose responsiveness and learning behavior of honeybees. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 256, 114850 (2023).

Kenna, D. et al. Pesticide exposure affects flight dynamics and reduces flight endurance in bumblebees. Ecol. Evol. 9, 5637–5650 (2019).

El Khoury, S., Giovenazzo, P. & Derome, N. Endogenous honeybee gut microbiota metabolize the pesticide clothianidin. Microorganisms 10, 493 (2022).

Zhou, T., Jørgensen, L., Mattebjerg, M. A., Chronakis, I. S. & Ye, L. Molecularly imprinted polymer beads for nicotine recognition prepared by RAFT precipitation polymerization: a step forward towards multi-functionalities. RSC Adv. 4, 30292–30299 (2014).

Rademacher, E., Harz, M. & Schneider, S. Effects of oxalic acid on Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Insects 8, 84 (2017).

Lagergren, S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of sobule substances. Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakad. Handl. 24, 1–39 (1898).

Ho, Y. S. & McKay, G. A comparison of chemisorption kinetic models applied to pollutant removal on various sorbents. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 76, 332–340 (1998).

Wang, M., Yang, C., Cao, J., Yan, H. & Qiao, F. Dual-template hydrophilic imprinted resin as an adsorbent for highly selective simultaneous extraction and determination of multiple trace plant growth regulators in red wine samples. Food Chem. 411, 135471 (2023).

Blanchard, G., Maunaye, M. & Martin, G. Removal of heavy metals from waters by means of natural zeolites. Water Res. 18, 1501–1507 (1984).

Skorupski, P. & Chittka, L. Photoreceptor spectral sensitivity in the bumblebee, Bombus impatiens (Hymenoptera: Apidae). PLoS ONE 5, e12049 (2010).

Kántor, I. et al. Biocatalytic synthesis of poly[ε-caprolactone-co-(12-hydroxystearate)] copolymer for sorafenib nanoformulation useful in drug delivery. Catal. Today 366, 195–201 (2021).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Therneau, T. M. coxme: Mixed effects Cox models. R package version 2.2-18.1 (2022).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Cornell University Department of Human Ecology for the use of HPLC. Fluorescence microscopy was carried out at the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology’s BRC Imaging Facility. We acknowledge the use of field emission scanning electron microscopy supported by NSF through the Cornell University Materials Research Science and Engineering Center DMR-1719875. This work was supported by the New York State Environmental Protection Fund. We acknowledge the following USDA NIFA grants: 2021-22-127 (M.M.) and 2021-08373 (M.K.S.). We thank A. Rios Tascon for helping design locomotion chambers and providing code to analyze locomotion videos. Schematics in Fig. 1a and 4a were created with BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.C. and M.M. conceived the study. J.S.C., M.M. and S.H.M. designed experiments. J.S.C. conducted and supervised all experiments and data collection. L.W. prepared materials, performed colony maintenance and assisted with bee transfers and experiments. S.F. assisted with bee transfers and experiments. C.R., M.H., S.J. and M.K.S. collected WBF data and calculated WBF. J.S.C. analyzed all data collected. J.S.C., S.H.M. and M.M. reviewed and interpreted the results. J.S.C. wrote the paper; M.M. provided substantial edits. All authors reviewed and commented on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Rachel Parkinson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–8.

Supplementary Data

Source data for Supplementary Figs. 3, 4 and 7.

Source data

Source Data

Statistical source data for Figs 1c,d, 2a–d, 4b,d and 5b,c.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Caserto, J.S., Wright, L., Reese, C. et al. Ingestible hydrogel microparticles improve bee health after pesticide exposure. Nat Sustain 7, 1441–1451 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01432-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01432-5