Abstract

Decarbonizing the economy requires a large-scale transition from fossil carbon-containing feedstocks to minerals and biomass, notably wood in buildings. Increasing harvesting is under discussion to meet the supply of wood for ‘timber cities’, with potentially negative impacts on forests and biodiversity. Here we investigate pathways to timber cities, including their impacts on land use, energy use and greenhouse gas emissions by quantifying global and regional wood cycles using Bayesian material flow analysis. We show that shifting wood fuel to industrial use and maximizing circular use of wood can make timber cities possible with the current harvest volume. Our results reveal that these pathways have better environmental performance than increased harvesting, reducing total CO2 equivalent emissions by 2100 by 40.8 Gt compared to business as usual. To achieve the wood transition, regional and cross-sectoral governance and planning are needed, addressing national-level pathways and inter-regional wood transport. The most critical actions are reducing the use of virgin wood as fuel by promoting cleaner alternatives, and using wood waste more effectively globally, rather than expanding plantation forests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Achieving decarbonization ambitions such as the Paris Agreement and net-zero strategies of intergovernmental organizations1 requires widespread switching from fossil carbon-containing feedstocks to minerals and biomass to produce materials and energy; the ‘wood transition’ describes the role of wood in this switch. Wood contributes to climate change mitigation by storing carbon dioxide (CO2) during growth, which remains sequestered in its products, and by substituting functionally equivalent and higher greenhouse gas (GHG; expressed as CO2 equivalents, CO2-eq.) emission footprints materials such as concrete, steel, plastics (for example, polyethene), glass, cotton and fossil fuels (for example, coal, oil, natural gas)2. It is estimated that wood products currently in use (for example, construction timber, wooden furniture) sequester a net emissions of 0.33 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2-eq. per year globally3 and 0.04 GtCO2-eq. per year in Europe4. These sequestrations were comparable to the total CO2-eq. emissions of Spain (0.3 GtCO2-eq.) and Denmark (0.04 GtCO2-eq.) in 2022, respectively5.

Many studies have investigated the impact of wood substitution for reducing CO2-eq. emissions for different regions and industries6,7,8. Construction is the most studied sector2. The worldwide substitution of engineered structural timber such as glue-laminated timber (glulam) and cross-laminated timber (CLT) for steel and concrete in structural frames of buildings has important climate change benefits9,10. It was reported that for 90% of the new urban population, construction of new residential and commercial buildings (with a 30 m2 per capita average floor area) with engineered timber structural frames and wood-based envelopes can store 0.94 GtCO2-eq. per year10.

However, it is poorly understood how the supply of wood from both natural forests and anthropogenic sources (for example, plantation, circular use) can be managed to meet the anticipated increase in demand required to achieve the wood transition, whether globally or regionally. Increasing forest harvest volumes and expanding plantation forests lead to large negative impacts, including loss of natural forest ecosystems and biodiversity11,12,13,14. For the global wood transition, it is expected that developing and least developed countries such as India, Nigeria, Congo and Ethiopia15 will have the highest demand for engineered timber16. However, secondary forests (forests that show signs of human intervention and control, that is, mature wood resources suitable for sustainable forestry) and plantation forest areas are limited in many of these countries, meaning that there is substantial deforestation risk associated with the expansion of wood production in these countries17. Therefore, it is crucial to explore alternative ways, other than further harvesting, to meet the wood demand of timber cities (for timber cities, we assume that 90% of the new urban population will live in engineered timber buildings in line with refs. 10,16).

Previous studies analysed wood use in individual countries and aspects such as environmental impacts18, material use19,20,21 and material efficiency22,23,24. Wood transition studies mainly focused on increased harvesting and expanding plantation forests to meet engineered timber demand. It was reported that by 2100 the global wood plantation area should increase to 425 million hectares (Mha) to fulfil the increased demand for buildings in the wood transition16. This is a 224% expansion compared to the global plantation area in 2020 (131 Mha), which conflicts with the historical trend of a 2.5% decrease in global forest area between 2000 and 2021 (including a decrease by 0.5% between 2017 and 2021)25. It was also proposed that shifting wood fuel harvesting to industrial use could fulfil the requirement for engineered timber in nearly 50% of new residential and commercial buildings globally10. However, large-scale wood fuel replacement may result in increased demand for carbon-intensive alternative energy sources such as oil and coal, particularly in Africa and Latin America due to population dependence on bioenergy26. These facts show the substantial potential for supply–demand imbalances in, and unintended environmental impacts such as an increase in fossil fuel use, and loss of natural forest ecosystems and biodiversity12,13,14 of the wood transition.

In summary, past studies about the future supply and demand of wood do not (1) assess alternative wood transition pathways such as high circular use of wood, (2) quantify how much additional fossil fuel-derived energy is needed to enable shifting wood fuel to industrial use for the wood transition, (3) account for the impact of increased waste generation amounts (due to increased engineered structural timber production) on the wood cycle and associated emissions and (4) provide detailed global and regional quantification of engineered structural timber production (for example, glulam, CLT), which is a key enabler of the wood transition. To fill these knowledge gaps, we analyse and compare pathways towards a large-scale transition to timber cities, to identify feasible wood transitions and their environmental impacts.

We consider the current state of the wood cycle to indicate business as usual, and three wood transition scenarios that model the construction of engineered timber buildings for 90% of the new urban population. They are: (1) a baseline (‘business as usual’, BAU) scenario where no wood transition occurs, and wood transition scenarios where engineered timber demand will be supplied by (2) wood fuel shifting to industrial use (‘shift’), (3) increased harvesting (‘harvest’) and (4) high circular use of wood (‘circular’) (main pathways; Methods). We introduce a novel circular pathway and enhance wood fuel shifting and increased harvesting pathways. This is through a detailed quantification of the wood cycle, changes in energy balance and the impact of existing and increasing wood waste on the wood cycle. We also provide global hybrid pathways (that is, combination of main pathways) because it may not be possible to follow a single transition scenario due to global and regional constraints (for example, low recycling potentials in some countries). All these scenarios explore the whole system quantifying energy supply and demand, plantation forest area needs, and GHG emissions from the wood cycle, energy use and production of non-biomass construction materials.

We first quantify the wood life cycle in 2021 comprehensively at regional and global levels as a first step in connecting socio-economic and biophysical processes to understand interactions between society and nature27 for wood (for example, wood use of society for energy and construction needs), then use the results to analyse pathways, opportunities and barriers for the wood transition. The pathways are modelled for 2021, our reference year, and assume that annual changes in engineered timber demand, emissions and energy balance due to the construction of timber cities will be the same between 2021 and 2100. We used recently developed Bayesian material flow analysis (BaMFA) methodology28 for explicit disaggregation of wood-based products and waste flows to the higher level of detail which is needed for analysis of wood transition. We also provide these higher reliability results in a database to facilitate future wood research (available as electronic Supplementary Information29).

Results

Global wood cycle reveals barriers and opportunities

Engineered structural timber currently plays a minor role in the global wood cycle and represents a small share of construction products. This indicates that a large-scale transition to timber cities requires a major realignment in the wood and construction sectors. Engineered structural timber constituted only 0.26% (7.4 million oven-dry metric tonnes (Modmt), with a range of 5.5–9.2 Modmt) of the total end use of wood in 2021 (Fig. 1). This is equivalent to 2.7% of the total amount of wood used in construction (273 Modmt, or 9.8% of the total wood end use in 2021) (Fig. 1). This annual production rate could therefore satisfy 2.9% of the residential and commercial building demand for the global wood transition (Supplementary Table 5).

All quantities are in Modmt. Quantities for each flow represent the mean values from the BaMFA results. Mass imbalances result from uncertainty in the input data used in the model and in the conservation of mass conditions as a result of BaMFA. The mean of the absolute mass imbalances for the global wood cycle results is 0.2 Modmt. pr., production; MDF, medium-density fibreboard; HDF, high-density fibreboard; OSB, oriented strand board.

The large footprint of bioenergy in the wood cycle could prevent the major realignment in the wood sector required by the wood transition or lead to an imbalance in the global energy supply. Bioenergy was 67% (1,876 Modmt) of total wood end use in 2021 (Fig. 1). This was used to produce 35.6 exajoules (EJ) of energy, which accounts for 6% of global energy consumption (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

The end uses of hardwood and softwood differ, which is a barrier to the wood transition. Hardwood is more often used as wood fuel: wood fuel accounted for 69% (1,394 Modmt) of the total hardwood harvest. Conversely, sawlogs and veneer logs, which are mainly used to produce sawnwood (for example, for construction timber), accounted for 13% (258 Modmt) of hardwood harvest and 62% (436 Modmt) of softwood harvest (Fig. 1). Softwood is currently the predominant wood type for construction timber products due to its easier-to-process material properties, the lower availability of machinery suitable for processing hardwood16 and the biological limitations of some hardwood species (for example, low durability due to reaction to moisture).

Hardwood use in construction may be the key to meeting engineered timber demand in wood transition, because expanding plantation forests to produce more softwood has limitations: (1) it could lead to loss of natural forests and biodiversity11,12,13,14, (2) natural (for example, vulnerability of softwood species to forest insects) and regional limitations due to softwood (colder climates) and hardwood (temperate climates) tree species grow in different climates, (3) vulnerability of softwood species against fire and wind damage, which can cause widespread tree mortality30. The second and third limitations will become increasingly important due to global warming as it may cause fire and insect outbreaks in forests31. It has been also reported that common hardwoods such as Quercus species (that is, oak) and Fagus sylvatica species (that is, beech) are naturally very durable32. As such, it is more attractive to increase hardwood use in construction through the development of suitable machinery, and more importantly, reducing the dependence of bioenergy on hardwood.

There is substantial potential to reduce the dependency of the wood transition on increased harvesting by increasing material efficiency, including through functional recovery and recycling33 in the wood cycle. Total unrecovered waste (311 Modmt) and total waste used for energy recovery (445 Modmt) consisted of 28% of the total harvest in 2021 (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Fig. 1). Increased engineered timber production in the wood transition will lead to increased production wood waste (for example, wood chips, residues) generation (311 Modmt yr−1) in the global wood cycle creating more circular use potential (Fig. 2b–d). Circular approaches have the potential to accelerate the wood transition as they reduce forest expansion needs, and associated wastes can be locally available around the world (Supplementary Information 1, section 2.1.6, provides details and examples).

a, ‘BAU’ scenario. b, ‘Shift’ scenario. c, ‘Harvest’ scenario. d, ‘Circular’ scenario. The scenarios represent a one-year change for large-scale wood transition based on the global wood cycle for 2021. Timber cities represent that 90% of the new urban population will live in engineered timber buildings with a 30 m2 per capita average floor area. The data for mass, emissions and energy represent total mean annual values based on scenarios.

Multiple transitions are possible without harvesting more

Pathways to a large-scale wood transition affect raw material and harvesting needs, GHG emissions and energy supply from wood-based bioenergy globally. Our results show that the wood transition is possible at current harvesting volumes in case of wood fuel shifting to industrial use (‘shift’) or maximum circular use of wood (‘circular’).

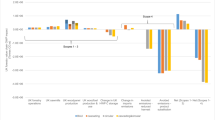

The ‘shift’ scenario relocates 40% (592 Modmt) of annual wood fuel harvesting to industrial roundwood harvesting to meet increasing engineered timber needs (Fig. 2b) (Supplementary Information 1, section 2.1.5, provides a literature review supporting that a 40% relocation is achievable). This scenario uses production wastes from all stages of additional timber production (that is, increased sawnwood and engineered structural timber production due to increased demand) for bioenergy. Despite this, the total amount of wood-based bioenergy decreases by 12% (234 Modmt) due to the relocation of wood fuel, implying a need for other energy sources globally (Fig. 2b). This need is modelled based on the global primary energy supply fuel percentages34 (30.9% oil, 26.8% coal, 23.2% natural gas, 19.1% other).

The ‘circular’ scenario increases annual industrial roundwood harvesting by only 5% (63 Modmt), and it reduces wood fuel harvesting by 6% (90 Modmt) compared to the ‘BAU’ scenario (Fig. 2d). This is achieved by increasing the wood-based waste recycling rate by 27% (57% for ‘circular’ and 30% for ‘BAU’). The wood-based waste which is not recycled is used for bioenergy, ideally making its disposal rate zero.

The ‘harvest’ scenario meets the timber needs of the wood transition by increasing annual industrial roundwood harvesting by 40% (496 Modmt) (Fig. 2c). At the same time, this scenario reduces the wood fuel harvesting need by 11% (165 Modmt) due to increased amount of energy recovery from additional production waste. Overall, the ‘circular’ scenario (1,287 Modmt) needs 29% and 25% less industrial roundwood harvesting compared to the ‘shift’ (1,816 Modmt) and ‘harvest’ (1,720 Modmt) scenarios, respectively (Fig. 2b–d).

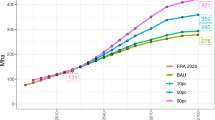

Shift and circular scenarios are more climate-friendly

Shifting wood fuel to industrial use maximizes the potential climate change benefits of the wood transition even though it increases emissions from fossil fuel use. The ‘shift’ scenario (6.06 GtCO2-eq.) reduces annual GHG emissions by 8%, 5% and 0.5% compared to ‘BAU’ (6.57 GtCO2-eq.), ‘harvest’, (6.38 GtCO2-eq.) and ‘circular’ (6.09 GtCO2-eq.) scenarios, respectively (Fig. 3c). This reduction is mostly due to the reduction of biogenic emissions (from combustion of wood for bioenergy): in the global wood cycle, biogenic emissions constitute the largest emission source for each scenario (63% for ‘BAU’, 60% for ‘shift’, 62% for ‘harvest’ and 65% for ‘circular’) (Fig. 3a). Due to reduced wood-based bioenergy resources as a result of the ‘shift’ scenario (234 Modmt less wood-based bioenergy, 4.5 EJ less energy supply), biogenic emissions decrease by 0.50 GtCO2-eq., increasing non-biogenic emissions from additional fossil fuel use by 0.32 GtCO2-eq. annually (Fig. 3a,b). Overall, shifting wood fuel to industrial use can reduce 0.51 GtCO2-eq. of emissions annually with a total of 40.8 GtCO2-eq. by the end of 2100 (~22% of the remaining carbon budget (~188 GtCO2 as of January 202535) to limit warming to 1.5 °C) (Fig. 3c). Timber cities can store 37.6 GtCO2 (0.47 GtCO2 yr−1) and reduce 24 GtCO2-eq. (0.3 GtCO2-eq. yr−1) emissions from non-biomass construction materials relative to ‘BAU’ by the end of 2100 (Fig. 3b,e).

a, Annual wood cycle CO2-eq. emissions. b, Annual emissions from building construction and additional fuel use due to wood transition. c, Total annual CO2-eq. emissions in the wood transition. d, Annual energy supply and demand of wood cycle. e, Annual CO2 storage in harvested wood products. f, Plantation forest area needs. The heights of the bars for each variable represent the mean values calculated based on the wood transition scenarios where new buildings have 30 m2 per capita average floor area. The red error bars represent the minimum and maximum of the net/total mean values (for 30 m2 per capita floor area, red dot) in each bar and are calculated based on the projected minimum (for 9.20 m2 per capita floor area) and maximum (for 79.10 m2 per capita floor area) engineered structural timber demand.

A large-scale wood transition is possible without dramatically affecting the global energy balance and land use but only through the ‘shift’ and ‘circular’ pathways. The ‘shift’ scenario needs 4.5 EJ (~0.75% of global energy consumption) energy supply from other sources (Fig. 3d). Although the ‘circular’ scenario has the highest energy use in wood cycle stages (8.8 EJ) among the wood transition scenarios, increased wood-based waste use for energy recovery (10.2 EJ) makes the bioenergy supply the same as the ‘BAU’ and ‘harvest’ scenarios (35.6 EJ) (Fig. 3d). Our results also show that the ‘shift’ scenario can meet harvesting needs without additional plantation forests, and the ‘circular’ scenario requires an additional 15% plantation forest area (21 Mha expansion, total of 158 Mha) compared to ‘BAU’. This is 87% less than the expansion needs in the ‘harvest’ scenario (168 Mha expansion, total of 305 Mha) (Fig. 3f).

Regional variations limit the wood transition

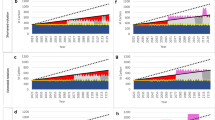

There are substantial differences between regional wood cycles (Figs. 4 and 5). Regions comprising mostly developing and underdeveloped countries (‘China’ (CHA), ‘India’ (IND), ‘Latin America’ (LAM), ‘Middle East Asia’ (MEA), ‘Non-European Countries’ (NEU), ‘Other Asian Countries’ (OAS), ‘Reforming Economies’ (REF) and ‘Sub-Saharan Africa’ (SSA)) produced only 30% of the total global amount of engineering structural timber products despite these regions accounting for ~87% of the global population (and expected to be ~90% of the global population by 21005) (Fig. 4). These regions direct relatively large amounts of wood to bioenergy, and relatively little to construction, due to several factors such as economic development differences (for example, available production facilities) and cultural influences (for example, regional architectural preferences). They also had more total harvesting (77% of the total harvesting) and illegal harvesting (93% of illegal harvesting) (Fig. 5a), and so face the highest deforestation threat36 (Supplementary Information 1, section 2.3.1, provides detailed regional variations).

a, Harvest. b, Wood-based products end uses. c, Bioenergy use. d, Construction use. e, Post-consumer wood waste treatment. f, Post-consumer paper and paperboard waste treatment. The heights of the bars for each variable represent the mean values from the BaMFA results. The red error bars represent the lower and upper bounds of 95% credible intervals of the total mean values (red dot) in each bar and are calculated by summing the lower and upper bounds of the 95% credible intervals of each associated flow from the BaMFA results. agglo., agglomerates; proc., processed.

The differences in regional wood cycles limit the possibilities for regional wood transitions. For example, because the SSA and MEA regions have currently very limited secondary wood product use and wood-based waste, the recycling potential is inadequate to meet the high demand for engineered structural timber (89 Modmt for SSA and 24 Modmt for MEA) of these regions in the ‘circular’ scenario (Supplementary Figs. 15 and 23). In the ‘shift’ scenario, the MEA region also does not have sufficient wood fuel harvesting (45 Modmt) to be shifted to meet the increased demand for industrial roundwood (102 Modmt), meaning the region would need additional roundwood harvesting. Because of the low recycling potential and limited plantation forest area in the IND, MEA and SSA regions, the ‘circular’ scenario in these regions needs the same plantation forest expansion as the ‘harvest’ scenario (55 Mha for IND, 101 Mha for MEA and 87 Mha for SSA) (Supplementary Figs. 10, 16 and 24).

Hybrid pathways and inter-regional transport are beneficial

Hybrid pathways can make a global wood transition more feasible by overcoming global and regional limitations. For example, if 50% of the increased demand for engineered structural timber production is met by wood fuel shifting and the other 50% by increased harvesting (‘shift + harvest’), plantation forest expansion needs and annual emissions decrease by 100 Mha (60%) and 0.14 GtCO2-eq. (2%), respectively, compared to the ‘harvest’ scenario (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). Also, the mix of ‘shift’ and ‘circular’ scenarios (‘shift + circular’: 50% of the increased demand is met by wood fuel shifting, and the other 50% by applying circular pathway principles) shows similar CO2-eq. emissions reductions (0.5 GtCO2-eq. yr−1) to the ‘shift’ scenario (0.51 GtCO2-eq. yr−1) by decreasing total harvest needs by 1% (27 Modmt) (Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). Therefore, hybrid pathways provide increased environmental benefits than the ‘harvesting’ scenario alone (Supplementary Information 1, section 2.2).

Inter-regional wood transport can accelerate the wood transition and help avoid unintended environmental consequences such as deforestation in natural forests. Our results show that the production of engineered structural timber in the EUR region and exporting it to the SSA region does not compromise the climate change benefits of the wood transition (EUR + SSA case study in Supplementary Information 1, section 2.4.13). Considering the EUR and SSA regions together, the ‘harvest’ scenario shows total annual non-biogenic emissions from wood processing and transport increase by 6% (0.03 Gt) and 22% (0.03 Gt), respectively, compared to the ‘BAU’ scenario (Supplementary Fig. 28a). Construction of engineered timber buildings in the SSA region can reduce annual GHG emissions from the production of non-biomass construction materials by 0.11 Gt (92% decrease) and increase CO2 storage in harvested wood products by 0.17 Gt (155% increase) in all wood transition scenarios compared to the ‘BAU’ scenario (Supplementary Fig. 28b,e). Production of timber to satisfy demand in a region with limited resources in another region can also maximize the potential benefits of circular wood use, and substantially reduce the plantation forest area need. For example, the ‘circular’ scenario in EUR + SSA case study (26 Mha expansion) needs ~threefold less expansion of plantation forest area compared to SSA (83 Mha expansion) (Supplementary Figs. 24 and 28f).

Discussion

Our results show that either high circular wood use, wood fuel shifting to industrial use or a mix of these pathways can fulfil the engineered timber demand for the global wood transition to timber cities without further harvesting. We reveal that shifting 40% of annual wood fuel harvesting to industrial roundwood can satisfy this transition for 90% of the new urban population, contrary to Churkina et al.10. We attribute this difference to the improved wood cycle quantification in our scenarios, and the target year difference in this study10 (wood transition by 2050 vs. 2100). Consistent with Mishra et al.16, we model the wood transition to be completed by 2100 instead of 2050, because the latter requires unrealistically rapid changes in multiple regions and sectors (for example, construction, energy).

Shifting virgin wood fuel has the best climate change performance even though our model shows that it will increase fossil fuel emissions. This is because the reduction in biogenic emissions is larger than the additional fuel use emissions. The utilization of virgin wood for bioenergy is of environmental concern because it is not carbon neutral due to life cycle (for example, harvesting, transport) and land use emissions, and time lag between biogenic emissions and sequestration37,38,39,40. Use of virgin wood to produce bioenergy is responsible for 2.9 GtCO2-eq. yr−1 emissions (Supplementary Table 3). This is ~tenfold higher than the calculated CO2-eq. emissions reduction from the production of construction materials in the wood transition (~0.3 GtCO2-eq. yr−1, buildings with a 30 m2 per capita average floor area10). It, therefore, may be more important to reduce emissions from burning wood for energy than using wood in construction.

Greater investment in renewable alternatives to wood, such as solar and wind, is needed to both enable shifting wood fuel to industrial use and reduce overall CO2-eq. emissions from fossil fuel use. However, this faces practical (for example, electricity infrastructure development) and regional challenges. The share of electricity in global energy consumption was 20% in 20211, meaning there is a great electrification need in many sectors such as transport and buildings. For example, Africa has only 1% of the installed global solar energy capacity despite having 60% of its solar resource41. Of the total Africa population, 65% (~900 million people) and 43% lack access to clean cooking and electricity, respectively26. As a result, the climate change benefits of reducing virgin wood harvesting for bioenergy depend on the widespread adoption of renewable energy sources, which can reduce annual emissions from the wood transition by an additional 0.3 GtCO2-eq.

High circular wood use can accelerate the wood transition by reducing plantation forest expansion needs (87%) and cumulative CO2-eq. emissions (5%) by 2100 compared to increased harvesting. Benefits of circular wood use include facilitating avoidance of much of the temporal lag between the supply of virgin wood grown in forests and demand16, and providing an immediate and sustained reduction for virgin wood42. Circular wood use can also increase the global carbon sink42 of harvested wood products because it uses wood-based waste to produce new wood-based products or as feedstock in other sectors such as chemical (for example, lignin-based batteries43) and agriculture (for example, mulch)44. However, applying circular economy principles to the wood industry is challenging and limited by sectoral barriers (for example, weak visions for decarbonization42, limited willingness for cross-sectoral collaboration42, poor transparency of material flows42) and technical difficulties (for example, energy input and emissions due to recycling processes6, scrap contamination45 and structural conditions of wastes). For example, current engineered structural timber products such as glulam and CLT are produced from solid sawnwood46 and do not allow the use of recycled materials. However, recovered oak pieces from demolition47 and discarded wooden sleepers48 have recently been tested in the production of CLT, which were found to be suitable for structural applications in buildings. Implementation of these technologies requires further validation with larger samples from pilot production47,49. Increasing circular use requires better management of the life cycle of products from production to end use, and creating markets for waste-derived products. For example, the design and installation of timber components in a building requires special planning so that it can be disassembled without any damage to use in a new project (that is, design for reuse)50.

Transporting wood between regions can contribute to avoiding deforestation. Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Oceania are the regions with the most deforestation. Around 43 Mha forest area, an area roughly the size of Morocco, was lost between 2004 and 2017 in these regions (>10% of their total forest area)36. Inter-regional transport of wood may reduce total plantation forest needs in regions with deforestation hotspots, and accelerate the wood transition. Overseas transport of wood increases wood cycle transport emissions because it contributes importantly to the climate change impacts of wood products51. However, the increase in transport emissions is much less than the reduced emissions from non-biomass construction materials in the wood transition scenarios (for example, EUR + SSA case study; ‘Results’). To validate this, future studies should investigate wood trade flow analysis to identify import dependence and resource criticality of countries, and to quantify global climate change impacts of wood transport.

We showed that shifting wood for fuel to industrial use and circularity are lower CO2-eq. emitting pathways than increased harvesting and can support large-scale wood transitions. Regional limitations may dictate that only a mix of these pathways is feasible. Some regions (for example, CAZ) can meet their demand by partly shifting wood fuel to industrial use and increasing circular use. We expect the increase in wood waste (311 Modmt yr−1) from the production of engineered timber to increase the potential for circular wood use, and substantially reduce the demand for industrial roundwood or wood fuel in every wood transition pathway and region. Yet, some regions with low circular wood use potential (for example, SSA) may need to shift their wood fuel use to construction, expand their plantation forests and import wood from other regions together. The main regional constraints are bioenergy demand, recycling potential and the potential for forest and biodiversity loss. Globally, the most critical actions are reducing the use of virgin wood as fuel and using wood waste more effectively.

Moving forward, policymakers should consider identifying national-level (for example, ref. 52) wood transition pathways because transition analyses should be tailored to the local situations: problems, drivers of problems and possible solutions vary from region to region. Such analyses require reliable local data on the life cycles of associated materials especially for the construction and energy sectors to conduct suitably detailed substitution analyses (for example, detailed stock and flow data for aggregates, steel, natural gas, oil, coal, renewables). Future analyses should also consider the long-term climate impacts of timber cities (that is, after 2100, when timber buildings start to reach the end of their life span) because end-of-life utilization of timber waste can have substantial climate change impacts53 (Supplementary Information 1, section 3). Systems-based and whole-life-cycle approaches54 in substitution studies should be prioritized to realize global decarbonization through feasible transitions from fossil carbon-containing feedstocks to minerals and biomass.

Methods

Our wood cycle shows flows of wood-based products from harvesting to end-of-life waste including a detailed breakdown of products to support analysis of wood substitution, waste/residue generation and trade flows for 13 regions including global in 2021. We then created a comprehensive analysis of potential annual changes in the wood cycle if a large-scale wood transition were to occur. Our scenario analysis results provide emissions from the wood cycle, building construction, and additional fuel use changes, energy supply and demand of the wood cycle, CO2 storage in harvested wood products, and plantation forest area needs.

We use standard MAgPIE-4 (Model of Agricultural Production and its Impact on the Environment) world regions55 consistent with a previous study on assessing future land use16. MAgPIE-4 is a modular open-source framework for modelling global land systems. It simulates global land use scenarios and their interactions with the environment (for example, analysing future food demand based on population and gross domestic product projections, and calculating land use emissions from this future food demand). The regions are defined based on criteria including population, gross domestic product, energy demand for food, average production process costs and self-sufficiency ratios for food55. MAgPIE-4 features 12 regions: CAZ (Canada, Australia, New Zealand), CHA (China), EUR (Europe), IND (India), JPN (Japan), LAM (Latin America), MEA (Middle East Asia), NEU (Non-European Countries), OAS (Other Asian Countries), REF (Reforming Economies), SSA (Sub-Saharan Africa) and USA (United States of America) (Supplementary Table 6).

Our methodology mainly includes five steps, which are (1) wood-based product and activity classification, (2) data collection and preparation, (3) BaMFA, (4) scenario analysis for the wood transition and (5) output evaluation and visualization (Extended Data Fig. 4). We provide the full dataset for input tables, adapted BaMFA codebase and model outputs along with detailed output material flow tables and related Sankey diagrams of all life cycle stages for each region in Supplementary Information 2 (ref. 56). We also provide these (interactive) Sankey diagrams on a website that accompanies this Article (https://alperenyayla.github.io/globalwoodcycle (ref. 29)).

Wood-based product and activity classifications

We classified wood-based products and processing activities mainly following the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) classification of forest products57 to facilitate the inclusion of internationally comparable data. The wood classification mainly includes raw materials (for example, roundwood), primary products (for example, sawnwood, pulp), secondary products (for example, construction timber, packaging materials) and post-consumer waste (that is, post-consumer wood and paper). Primary products are produced by processing raw materials and are inputs for further production stages. Secondary products are mainly produced from primary products and used by end users. We made modifications in the FAO57 classification to achieve our goal of analysing and presenting data for wood substitution. These modifications include separating ‘engineered structural timber products’ from ‘builder’s joinery and carpentry wood’, and instead considering the latter as ‘other construction timber’ products. We assumed that ‘wood products for domestic and decorative use’ are classified as ‘other manufactured wood products’ and included ‘secondary paper products’ within ‘other paper and paperboard’. We added a stock of illegal sources to quantify illegal logging, which refers to the act of unlawfully harvesting wood58, and included production wastes, imports and exports and end-of-life uses to describe the entire wood cycle. We classified waste treatment activities following Eurostat59, with one modification: ‘open dump’ is added as a separate waste treatment method because disposing of waste in open dumps accounts for great amounts of the total waste in some regions. Six waste treatment methods were included in our study: ‘recycling’, ‘energy recovery’, ‘non-energy recovery’, ‘incineration-disposal’, ‘landfill’ and ‘open dump’ (see Supplementary Table 7 for the full list of classification).

Data collection and preparation

Our study uses stock and flow data, ‘changes in stock’ and ‘flow’ quantities, unit conversion factors and transfer coefficients. Wood stock and flow data were collected from various sources, primarily the Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT)60. The data we use relating to conversion factors are mainly based on FAO, International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) and United Nations61. End-of-life waste quantities of paper and paper products were calculated using the ‘net addition to stock’ parameter (which refers to a proportion of total production to identify the quantity of product that stays in use for a year) by van Ewijk et al.62. We estimated end-of-life waste quantities of wood products and proportions of treatment methods for all wood-based wastes using the World Bank waste database63 (see Supplementary Information 2 (ref. 56) for all datasets, data sources and calculations such as conversion factors and production process mass balance).

Mass conservation is performed on the basis of the oven-dry metric tonne (odmt) for all wood-based products. Because wood product quantities are reported in different units such as cubic metres for roundwoods and sawnwoods, and metric tonnes for paper products, we used conversion factors to change reported units into odmt. In calculating conversion factors, we subtracted masses of moisture and other components such as adhesives and additives in wood-based products to prevent including the mass of other materials in the mass of wood64. Because the properties of wood-based products such as dimensions and wood content vary by region, we used region-specific conversion factors where data were available. In the absence of these data, we used average conversion factors considering all available data for different countries.

We calculated the percentages of by-products and waste in each primary and secondary production process (for example, chips and particles from sawnwood production) and waste flows, which are generally not reported on (Extended Data Fig. 4b). For primary processing and secondary paper production, we did this using mass conservation and reported data for source materials and primary products and/or conversion factors61,62. The dataset for secondary wood products (for example, construction timber and wooden furniture) was developed using mass conversation and environmental product declaration (EPD) data65 using product density, and wood contents of the end products. The non-hazardous wastes specified by EPDs were assumed to be wood waste. We used the same material efficiency metric (or yield ratio, which is the proportion of the main product that is produced in a process relative to waste generated in that process) and production waste type (that is, wood residues) for all secondary wood products, which assumes that they have similar production processes.

Bayesian material flow analysis

We used recently developed BaMFA methodology28 for (1) explicit disaggregation of wood-based products to the higher level of detail that is needed for analysis of the wood transition (for example, engineered structural timber products); (2) inclusion of end-of-life flows, which are currently poorly reported on; and (3) reconciliation of the available data to quantify uncertainty and improve the reliability of the quantitative results (study by Wang et. al.28 and Supplementary Information 1, section 4.1, provide more details).

Contrary to the traditional MFA approach in which mass balance is enforced manually, we used BaMFA methodology where mass balance is incorporated into the model likelihood function28. The model outputs estimates, which are approximately rather than strictly mass balanced, and slight mass imbalances can be interpreted as epistemic uncertainty in the system66. In this model, processes are disaggregated resulting in a parent and child process structure. Parent processes contain subprocesses, and child processes do not contain any subprocesses. Here we disaggregated the wood-based product and waste classification and then created relationships between these disaggregated elements, such as flows and transfer coefficients, based on the data and information available.

In BaMFA, ‘changes in stock’ and ‘flow’ variables are described using two different levels of knowledge: ‘prior’ and ‘observed’. Detailed information on the selection of ‘prior’ and ‘observed’ data for each data point is given in Supplementary Information 2 (ref. 56). Multiple sources and data points can be used to describe any ‘change in stock’ or ‘flow’ variable in the input dataset. Some data points are specified without any knowledge or input value, and output values for these variables are calculated by the BaMFA model. For all variables without any ‘prior’ input, the model assigns a ‘prior’ quantity automatically which is the mean value of all prior data point inputs in our wood cycle analyses.

Accordingly, we used five input data tables which are ‘changes in stocks’, ‘changes in stocks prior’, ‘flows’, ‘flows prior’ and ‘ratio’. The ‘changes in stocks’ data table includes all child processes and notable parent processes of interest. The ‘flows’ data table includes all flows in the system. In the ‘changes in stocks’ and ‘flows’ data tables, data points with observed knowledge are included as numerical values, and other data points (for example, variables with only prior knowledge or without any value) are left as unknown (‘nan’). The ‘changes in stocks prior’ and ‘flows prior’ data tables only contain the quantities of related data points indicated as priors. The ‘ratio’ data table includes transfer coefficient values, and they are treated as observed data.

The BaMFA model is implemented in Python, and PyMC3 (ref. 67) is used to conduct Bayesian inference via the No-U-Turn-Sampler algorithm. The BaMFA codebase consists of four Python and one Jupyter Notebook source files. The Python source files define the necessary functions to prepare the input data for analysis (‘preprocessingagg.py’), to construct prior distributions for analysis (‘prior.py’), to conduct material flow analysis using Bayes’ theorem (‘model.py’) and lastly to construct posterior predictive distributions and plots for model and data checking (‘posteriorpredictive.py’). An additional Jupyter Notebook file (‘run-wood-model.ipynb’) is used to run the complete BaMFA model and obtain outputs combining all the other source files. The original BaMFA code28 uses ‘comma-separated values’ files as inputs. Because we use the FAO database and other information such as unit conversion factors, production process mass balances and waste data to provide data for our input data tables, we instead used separate Excel worksheets for these data tables contained within a single Excel input file for each region (including global). We additionally created another Python source file (‘outputforsankey.py’) to obtain the BaMFA model results for flows to make it easier to plot them in Sankey diagram format.

The BaMFA model produces posterior distributions of all child stock changes and flows by combining the prior distribution and data (including mass balance for all processes) via Bayes’ theorem, which includes quantifying and propagating uncertainties. The posterior distribution provides estimates for each stock change or flow of interest via the posterior mean and uncertainty quantification through 95% credible intervals. We visualized the mean values in Sankey diagrams and provided the full results in Supplementary Information 2 (ref. 56).

For a detailed uncertainty evaluation, we used marginal posterior distribution graphs of each data point for child stocks and flows. These graphs show both the posterior distribution results (posterior mean and 95% credible interval bounds) and our input values for each data point, allowing us to compare our input values with the corresponding BaMFA model output. We also analyse the BaMFA output results using Bayesian posterior predictive P values to compare the input data with the posterior distributions28. P values are calculated for each data point for all parameters including changes in stocks, flows, transfer coefficients and conservation of mass conditions. P values greater than 0.95 or smaller than 0.05 indicate an inconsistency between the model output and input data68.

A key value of BaMFA is that it quantifies the uncertainty in the input data and propagates it into the output results (posterior distributions)28. This enables the identification of both input data and the calculation of output results with relatively high uncertainty. We used this information to direct the collection of more data, and data from more reliable sources, to reduce the overall uncertainty in our results. We validate our results by comparing them with data reported in the existing literature (for example, FAO69). Accordingly, another key value of our study is that it highlights data points in the wood cycle that require further investigation (Supplementary Information 1, section 2.5, provides detailed uncertainty results).

Scenario analysis

To analyse CO2-eq. emissions, energy and plantation forest changes caused by a large-scale wood transition, we investigated four main scenarios (that is, main pathways): (1) a baseline business as usual (BAU) scenario in which future urban mid-rise buildings are built with steel and concrete, and three wood transition scenarios in which future urban mid-rise buildings are built with engineered timber and involve (2) shifting wood fuel to industrial use (‘shift’), (3) more harvesting (‘harvest’) and (4) a high wood recycling rate (‘circular’). For all wood transition scenarios, 90% of the new urban population is assumed to live in engineered timber buildings (30 m2 per capita average floor area with a range of 9.20 m2 per capita and 79.10 m2 per capita), with the rest living in buildings constructed with steel and concrete10,16 (Extended Data Fig. 4d). These scenarios are modelled for 2021, our reference year, and assume that annual changes in engineered timber demand, emissions and energy balance due to the construction of timber cities will be the same between 2021 and 2100 (inclusive) consistent with the approach used by Churkina et al.10.

We additionally define three hybrid scenarios at the global scale, which combine the three main wood transition scenarios (that is, shift, harvest and circular): (1) ‘shift + harvest’, where the increased demand for engineered structural timber production is met by wood fuel shifting and increased harvesting; (2) ‘shift + circular’, where the increased demand for engineered structural timber production is met by wood fuel shifting and more wood recycling; and (3) ‘circular + harvest’, where the increased demand for engineered structural timber production is met by increased harvesting and more wood recycling (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.1, provides a detailed explanation and related assumptions of the scenarios).

The reason for exploring global hybrid pathways is that it may not be possible to follow a single transition scenario due to global and regional constraints (for example, because 100% recovery and reuse of materials can be theoretically possible but not achievable in practice due to yield losses, and low wood waste recycling potentials in some regions such as SSA). Therefore, the main pathways represent reference points that highlight the landscape of possible scenarios, and hybrid pathways represent scenarios that are more likely to be implemented.

We calculate the engineered structural timber demand in each region and globally based on urban population growth corresponding to the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2 (SSP2) scenario70. Countries reach their peak urban population in different years (for example, 2090 for Australia, 2080 for Türkiye). Population growth between 2020 and the year of the peak urban population is considered as the potential new population that will live in engineered timber buildings for that country (that is, peak urban population growth). On the basis of this, peak urban population growth in each country, cumulative population growth for regions and global is calculated. We then convert the cumulative population into annual population growth, averaged over 80 years (2021–2100, inclusive), which models the large-scale transition to timber cities as a linear gradual process. For this population growth, we calculated total engineered structural demand based on floor area per capita, and structural and enclosure system material intensity assumptions taken from Churkina et. al.10 (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.2).

We use the ecoinvent database71 (v3.10 cut-off) to calculate CO2-eq. emissions from and energy input to the global wood cycle. For each production process, we identify CO2-eq. emissions and energy use associated directly with that process (for example, for sawnwood production, only CO2-eq. emissions and energy use in the sawnwood production facility) and transport (for example, delivery to the consumer of produced sawnwood) per odmt of the product. These process inputs and outputs are linearly scaled from product to global levels. We also calculate CO2-eq. emissions from building construction and additional fuel use (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.3). In scenarios where bioenergy supply is reduced due to wood transition (for example, ‘shift’ and ‘shift + circular’), other energy sources need to be used. This need is modelled based on the global primary energy supply fuel percentages by the International Energy Agency34 (30.9% oil, 26.8% coal, 23.2% natural gas, 19.1% other).

When wood is completely combusted, all carbon contained in it is emitted into the atmosphere (that is, biogenic emissions). We calculate these biogenic CO2-eq. emissions due to bioenergy use (that is, combustion) of wood-based products based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines72, and our BaMFA results for bioenergy use (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.7). For biogenic CO2 removals from forest regrowth, we use the forward-looking approach which takes into account the carbon sequestration in growing trees after harvest. This sequestration is modelled as a Gaussian distribution based on tree species’ rotation period73. Because it is an incremental process, to be consistent with our scenario modelling, we find the total sequestration between 2020 and 2100, and convert this total sequestration quantity into annual sequestration values, by assuming it will be the same each year, similar to the approach for engineered timber demand (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.4).

We calculate plantation forest area needs based on the current harvest rate of plantation forests. We assume 33% of industrial roundwood harvesting is met by plantation forests74. Regional harvest rates of plantation forests are found according to each region’s (including global) industrial roundwood harvesting (results of BaMFA) and plantation forest areas in 2021 (from the FAOSTAT database25). We also assume that additional industrial roundwood is met by the expansion of plantation forest areas based on the current harvesting rate (Supplementary Information 1, section 4.4.5).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All input and output datasets, data sources for each data point, calculations such as conversion factors and production process mass balances, the BaMFA model codebase, Sankey diagrams and data tables for the figures in the paper are available in Supplementary Information 2 via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10828213 (ref. 56). A selection of numerical results is provided within this paper (including data presented in Supplementary Information 1). Interactive Sankey diagrams and related data tables, which accompany this paper, are publicly available at https://alperenyayla.github.io/globalwoodcycle (ref. 29). Wood stock and flow data were collected from various sources, primarily FAOSTAT60. The data relating to conversion factors were mainly sourced from the FAO, ITTO and United Nations61. End-of-life waste quantities of wood products and proportions of treatment methods for all wood-based wastes were calculated based on the World Bank waste database by Kaza et al.63. To calculate global and regional demand for engineered structural timber products, population and urban population share data were used from the shared socio-economic pathways scenario database published by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis75. The ecoinvent database (v3.10 cut-off) was used to calculate CO2-eq. emissions from and energy input to the global and regional wood cycles71.

Code availability

The BaMFA model was implemented in Python (v3.9.16), and PyMC3 (v3.11.2) was used to conduct Bayesian inference via the No-U-Turn-Sampler algorithm. The source code for the adapted BaMFA used in this study is publicly available via Github at https://github.com/alperenyayla/globalwoodcycle and in Supplementary Information 2 via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10828213 (ref. 56). The original BaMFA code is also publicly available via Github at https://github.com/jwang727/BayesianMFAcode (ref. 28).

References

Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach (IEA, 2023); https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach

Myllyviita, T., Soimakallio, S., Judl, J. & Seppala, J. Wood substitution potential in greenhouse gas emission reduction-review on current state and application of displacement factors. For. Ecosyst. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-021-00326-8 (2021).

Johnston, C. M. & Radeloff, V. C. Global mitigation potential of carbon stored in harvested wood products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 14526–14531 (2019).

Pilli, R., Grassi, G., Kurz, W. A., Fiorese, G. & Cescatti, A. The European forest sector: past and future carbon budget and fluxes under different management scenarios. Biogeosciences 14, 2387–2405 (2017).

European Commission Joint Research Centre et al. GHG Emissions of all World Countries (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023); https://doi.org/10.2760/953322

Duan, Z. C., Huang, Q. & Zhang, Q. Life cycle assessment of mass timber construction: a review. Build. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109320 (2022).

Geng, A. X., Ning, Z., Zhang, H. & Yang, H. Q. Quantifying the climate change mitigation potential of China’s furniture sector: wood substitution benefits on emission reduction. Ecol. Indic. 103, 363–372 (2019).

Smyth, C., Rampley, G., Lempriere, T. C., Schwab, O. & Kurz, W. A. Estimating product and energy substitution benefits in national-scale mitigation analyses for Canada. GCB Bioenergy 9, 1071–1084 (2017).

Pauliuk, S. et al. Global scenarios of resource and emission savings from material efficiency in residential buildings and cars. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25300-4 (2021).

Churkina, G. et al. Buildings as a global carbon sink. Nat. Sustain 3, 269–276 (2020).

Braun, A. C. et al. Assessing the impact of plantation forestry on plant biodiversity: a comparison of sites in Central Chile and Chilean Patagonia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 10, 159–172 (2017).

Burivalova, Z., Sekercioglu, Ç. H. & Koh, L. P. Thresholds of logging intensity to maintain tropical forest biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 24, 1893–1898 (2014).

Chaudhary, A., Burivalova, Z., Koh, L. P. & Hellweg, S. Impact of forest management on species richness: global meta-analysis and economic trade-offs. Sci. Rep. UK https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23954 (2016).

Martin, P. A., Newton, A. C., Pfeifer, M., Khoo, M. & Bullock, J. M. Impacts of tropical selective logging on carbon storage and tree species richness: a meta-analysis. For. Ecol. Manage. 356, 224–233 (2015).

World Population Prospects 2022 (United Nations, 2022); https://population.un.org/wpp/

Mishra, A. et al. Land use change and carbon emissions of a transformation to timber cities. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32244-w (2022).

The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, Biodiversity and People (FAO & UNEP, 2020); https://doi.org/10.4060/ca8642en

Kayo, C. et al. Environmental impact assessment of wood use in Japan through 2050 using material flow analysis and life cycle assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 23, 635–648 (2019).

Müller, D. B., Bader, H.-P. & Baccini, P. Long-term coordination of timber production and consumption using a dynamic material and energy flow analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 8, 65–87 (2004).

Parobek, J., Palus, H., Kaputa, V. & Supin, M. Analysis of wood flows in Slovakia. Bioresources 9, 6453–6462 (2014).

Sokka, L., Koponen, K. & Keränen, J. T. Cascading use of wood in Finland–with comparison to selected EU countries. Metsäenergian kestävyysselvitys Project numer https://publications.vtt.fi/julkaisut/muut/2015/VTT-R-03979-15.pdf (2015).

Besserer, A., Troilo, S., Girods, P., Rogaume, Y. & Brosse, N. Cascading recycling of wood waste: a review. Polymers https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13111752 (2021).

Goncalves, M., Freire, F. & Garcia, R. Material flow analysis of forest biomass in Portugal to support a circular bioeconomy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105507 (2021).

Marques, A., Cunha, J., De Meyer, A. & Navare, K. Contribution towards a comprehensive methodology for wood-based biomass material flow analysis in a circular economy setting. Forests https://doi.org/10.3390/f11010106 (2020).

Land Use (FAO, 2023); https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RL

Solid Biofuels Consumption Estimation Model (IEA, 2022); https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/solid-biofuels-consumption-estimation-model

Haberl, H. et al. Contributions of sociometabolic research to sustainability science. Nat. Sustain 2, 173–184 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Bayesian material flow analysis for systems with multiple levels of disaggregation and high dimensional data. J. Ind. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13550 (2024).

Yayla, A., Mason, A. R., Wang, J., van Ewijk, S. & Myers, R. J. Global wood cycle. GitHub https://alperenyayla.github.io/globalwoodcycle (2024).

Schelhaas, M. J. et al. Assessing risk and adaptation options to fires and windstorms in European forestry. Mitigation Adapt. Strategies Glob. Change 15, 681–701 (2010).

Freer-Smith, P. H. et al. Plantation Forests in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities (EFI, 2019); https://doi.org/10.36333/fs09

Shirmohammadi, M., Leggate, W. & Redman, A. Effects of moisture ingress and egress on the performance and service life of mass timber products in buildings: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 290, 123176 (2021).

Miller, S. A., Habert, G., Myers, R. J. & Harvey, J. T. Achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the cement industry via value chain mitigation strategies. One Earth 4, 1398–1411 (2021).

World Energy Balances: Overview (IEA, 2024); https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-balances-overview/world

That’s How Fast the Carbon Clock is Ticking (Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, 2025); https://www.mcc-berlin.net/en/research/co2-budget.html

Pacheco, P. et al. Deforestation Fronts: Drivers and Responses in a Changing World (WWF, 2021); https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/deforestation-fronts-drivers-and-responses-in-a-changing-world-full-report

Ahamer, G. Why biomass fuels are principally not carbon neutral. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/en15249619 (2022).

Peng, L., Searchinger, T. D., Zionts, J. & Waite, R. The carbon costs of global wood harvests. Nature 620, 110–115 (2023).

Leturcq, P. Wood preservation (carbon sequestration) or wood burning (fossil-fuel substitution), which is better for mitigating climate change? Ann. For. Sci. 71, 117–124 (2014).

Sterman, J. D., Siegel, L. & Rooney-Varga, J. N. Does replacing coal with wood lower CO2 emissions? Dynamic lifecycle analysis of wood bioenergy. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaa512 (2018).

Africa Energy Outlook 2022 (IEA, 2022); https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022

Forster, E. J., Healey, J. R., Newman, G. & Styles, D. Circular wood use can accelerate global decarbonisation but requires cross-sectoral coordination. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42499-6 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Lignin-based materials for electrochemical energy storage devices. Nano Mater. Sci. 5, 141–160 (2023).

Pandey, S. Wood waste utilization and associated product development from under-utilized low-quality wood and its prospects in Nepal. SN Appl. Sci. 4, 168 (2022).

Song, L. et al. China’s bulk material loops can be closed but deep decarbonization requires demand reduction. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1136–1143 (2023).

Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) (APA, 2024); https://www.apawood.org/cross-laminated-timber

Llana, D. F., González-Alegre, V., Portela, M. & Íñiguez-González, G. Cross laminated timber (CLT) manufactured with European oak recovered from demolition: structural properties and non-destructive evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 339, 127635 (2022).

Carrasco, E. et al. CLT from recycled wood: fabrication, influence of glue pressure and lamina quality on structural performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 378, 131048 (2023).

Rose, C. M. et al. Cross-laminated secondary timber: experimental testing and modelling the effect of defects and reduced feedstock properties. Sustainability 10, 4118 (2018).

Ottenhaus, L.-M. et al. Design for adaptability, disassembly and reuse—a review of reversible timber connection systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132823 (2023).

Punhagui, K. R. & John, V. M. Carbon dioxide emissions, embodied energy, material use efficiency of lumber manufactured from planted forest in Brazil. J. Build. Eng. 52, 104349 (2022).

Dai, M. et al. Country-specific net-zero strategies of the pulp and paper industry. Nature 626, 327–334 (2024).

Moreau, L., Thiffault, E., Kurz, W. A. & Beauregard, R. Under what circumstances can the forest sector contribute to 2050 climate change mitigation targets? A study from forest ecosystems to landfill methane emissions for the province of Quebec, Canada. GCB Bioenergy 15, 1119–1139 (2023).

Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future (UNEP, 2023); https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/43293

Dietrich, J. P. et al. MAgPIE 4-a modular open-source framework for modeling global land systems. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1299–1317 (2019).

Yayla, A., Mason, A. R., Wang, J., van Ewijk, S. & Myers, R. J. Data repository for global wood harvest is sufficient for climate-friendly transitions to timber cities. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10828213 (2024).

Classification of Forest Products 2022 (FAO, 2022); https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8216en

Illegal Logging (European Commission, 2021); https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/forests/deforestation/illegal-logging_en

Treatment of Waste by Waste Category, Hazardousness and Waste Management Operations (EUROSTAT, 2023); https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ENV_WASTRT/default/table?lang=en

Forestry Production and Trade (FAO, 2024); https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FO

Forest Product Conversion Factors (FAO, ITTO & United Nations, 2020); https://doi.org/10.4060/ca7952en

Van Ewijk, S., Stegemann, J. A. & Ekins, P. Global life cycle paper flows, recycling metrics, and material efficiency. J. Ind. Ecol. 22, 686–693 (2018).

Kaza, S., Yao, L., Bhada-Tata, P. & Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050 (World Bank, 2018); http://hdl.handle.net/10986/30317

Lenglet, J., Courtonne, J. Y. & Caurla, S. Material flow analysis of the forest-wood supply chain: a consequential approach for log export policies in France. J. Cleaner Prod. 165, 1296–1305 (2017).

Environmental Product Declaration Glued Laminated Timber (Glulam) (Wood Solutions, 2017); https://api.environdec.com/api/v1/EPDLibrary/Files/2263eda0-231e-412c-91e4-0a1894bf1a5d/Data

Schwab, O., Zoboli, O. & Rechberger, H. A data characterization framework for material flow analysis. J. Ind. Ecol. 21, 16–25 (2017).

Salvatier, J., Wiecki, T. V. & Fonnesbeck, C. Probabilistic programming in Python using PyMC3. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2, e55 (2016).

Gelman, A. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis (3rd edn) (Taylor & Francis Group, 2013); https://doi.org/10.1201/b16018

Wood Energy (FAO, 2021); https://www.fao.org/forestry-fao/energy/en/

O’Neill, B. C. et al. A new scenario framework for climate change research: the concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change 122, 387–400 (2014).

Ecoinvent database. Ecoinvent https://ecoinvent.org/ (2024).

Eggleston, H., Buendia, L., Miwa, K., Ngara, T. & Tanabe, K. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (IPCC, 2006); https://www.ipcc.ch/report/2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/

Cherubini, F., Peters, G. P., Berntsen, T., Stromman, A. H. & Hertwich, E. CO2 emissions from biomass combustion for bioenergy: atmospheric decay and contribution to global warming. GCB Bioenergy 3, 413–426 (2011).

Jürgensen, C., Kollert, W. & Lebedys, A. Assessment of Industrial Roundwood Production from Planted Forests, Planted Forests and Trees Working Papers eng no. FP/48/E (FAO, 2014); https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2de6f55e-9170-4703-8028-74809aeb2045/content

SSP Database (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways)—Version 2.0. IIIASA https://tntcat.iiasa.ac.at/SspDb/dsd?Action=htmlpage&page=welcome (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Bide for useful discussions on the material flow analysis methodology and results. A.Y. gratefully acknowledges the funding provided by the Republic of Türkiye Ministry of National Education via a postgraduate research scholarship, and Imperial College London via a Dixon scholarship. This work was supported by the United Kingdom Research and Innovation Interdisciplinary Circular Economy Centre for Mineral-Based Construction Materials under Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council grant EP/V011820/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Y. and R.J.M originated the idea; A.Y. prepared the first draft and contributed to research design, write-up and research execution; A.R.M. and J.W. contributed to research execution and write-up; S.v.E. contributed to research design and write-up; R.J.M. led the research design and write-up of the paper, and contributed to research execution.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Bernardino D’Amico, Barbara Reck and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Waste treatment methods of wood-based wastes and their quantities in 2021.

a Wood particles production waste. b Post-consumer wood waste. c Pulp and paper production waste. d Post-consumer paper and paperboard waste. e Total waste. The heights of the bars for each variable represent the mean values from the BaMFA results. The red error bars represent the lower and upper bounds of 95% credible intervals of the total mean values (red dot) in each bar, and are calculated by summing the lower and upper bounds of the 95% credible intervals of each associated flow from the Bayesian material flow analysis (BaMFA) results. Abbreviations: Modmt, million oven-dry metric tonnes; rec., recovery; disp., disposal.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Global hybrid pathways towards large-scale transition for timber cities.

a ‘Business as usual’ (BAU) scenario, b ‘Shift + Harvest’ scenario, c ‘Harvest + Circular’ scenario, d ‘Harvest + Circular’ scenario. The scenarios represent a one-year change for large-scale wood transition based on the global wood cycle in 2021. Timber cities represent that 90% of the new urban population will live in engineered timber buildings with a 30 m2 per capita average floor area. The data for mass, emissions, and energy represent total mean annual values based on scenarios. Abbreviations: Gt CO2-eq., gigatonnes carbon dioxide equivalents; Modmt, million oven-dry metric tonnes; EJ, exajoules.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CO2-eq. emissions from the wood cycle and changing balance due to wood transition, energy balance, CO2 storage in harvested wood products, and plantation forest needs according to different hybrid wood transition pathways.

a Annual wood cycle CO2-eq. emissions, b Annual emissions from building construction and additional fuel use due to wood transition, c Total annual CO2-eq. emissions in the wood transition, d Annual energy supply and demand of wood cycle, e Annual CO2 storage in harvested wood products, f Plantation forest area needs. The heights of the bars for each variable represent the mean values calculated based on the wood transition scenarios where new buildings have 30 m2 per capita average floor area. The red error bars represent the minimum and maximum of the net/total mean values (for 30 m2 per capita floor area, red dot) in each bar, and are calculated based on the projected minimum (for 9.20 m2 per capita floor area) and maximum (for 79.10 m2 per capita floor area) engineered structural timber demand. Abbreviations: CO2-eq., carbon dioxide equivalents; Gt, gigatonnes; EJ, exajoules; Mha, million hectares.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Schematic of the methodology used in this paper.

It includes five steps: a Wood-based product and activity classification, b Data collection and preparation, c Bayesian material flow analysis, d Scenario analysis for wood transition, and e Output evaluation and visualization. Abbreviations: m3, cubic meter; mt, metric tonne; odmt, oven-dry metric tonne; HDI, highest density intervals; CO2, carbon dioxide.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary results, methods, discussion and references. Supplementary Figs. 1–34 and Tables 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yayla, A., Mason, A.R., Wang, J. et al. Global wood harvest is sufficient for climate-friendly transitions to timber cities. Nat Sustain 8, 1013–1025 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01605-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01605-w