Abstract

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) aims to avoid carbon leakage by pricing the production emissions of imported goods. Currently, the CBAM applies to iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen. As the European Union considers extending the CBAM to chemicals by 2030, its effectiveness in this complex industry remains uncertain. Here we assess how well the CBAM would capture emissions in the chemical industry by using the life-cycle assessment data of 4,470 global chemical production facilities, focusing on the key products ethylene and polyethylene. We find that the current CBAM framework would cover 50–60% of production emissions for these products, leaving substantial upstream emissions unpriced. This limited emission coverage risks compromising the policy’s climate ambition and distorts market incentives. To improve effectiveness, the CBAM would need to expand to include fossil feedstocks and refinery products, and implement high fallback default values for embodied emissions to incentivize data reporting. Our findings highlight the need for detailed supply chain tracking and early engagement with chemical industry stakeholders to ensure that the CBAM supports a fair and effective net-zero transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Increased climate action is necessary to limit the consequences of global warming1. To mitigate climate change, countries set nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement2. While the Paris Agreement facilitates policy coordination through periodic reporting and progress assessment, climate policy implementation remains largely decentralized. This decentralization can result in unilateral climate policies that financially burden producers, potentially shifting production to regions with less stringent regulation—a phenomenon called carbon leakage3,4. Carbon leakage can increase global emissions and compromise the competitiveness of industries in climate-ambitious countries5. To mitigate carbon leakage, multiple countries consider Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAMs)6,7,8,9 to establish a level playing field for domestic industries by taxing imported goods based on their carbon footprint.

In 2023, the European Union (EU) introduced a CBAM for major industry sectors at risk of carbon leakage10 to complement the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). While the ETS regulates emissions from emission-intensive industries within the EU, the CBAM extends carbon pricing to certain imported goods. However, its scope is more limited, currently covering iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminium, electricity and a few other products, including hydrogen. Moving from its current transitional phase to full effect by 202610,11, the EU CBAM functions similarly to an import tax proportional to the greenhouse gas emissions caused during the production (‘embodied emissions’) of imported goods5,12,13,14.

Note that while the EU legislation uses the term ‘embedded’ emissions, we refer to embodied emissions throughout this work to avoid confusion with end-of-life carbon release, particularly in the context of life-cycle assessment (LCA).

To prevent carbon leakage, the CBAM must accurately distinguish between high-emission and low-emission imports and charge producers accordingly. Inaccurate determination of embodied emissions could undermine the goal of the CBAM, potentially incentivizing EU producers to relocate to regions with looser emission standards and increasing global production emissions.

Accurate determination of embodied emissions is thus crucial for the effectiveness of CBAMs. From an environmental standpoint, the ideal policy would account for actual cradle-to-border life-cycle emissions for each import. However, achieving this theoretical ideal requires prohibitively extensive primary data5,13,15. As an alternative, each imported product can be assigned a default embodied emission value, at the cost of reduced accuracy and diminished CBAM effectiveness16.

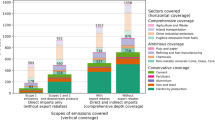

The adopted EU CBAM stipulates that embodied emissions for imports are calculated using facility-specific emission data (‘baseline calculation’, Fig. 1). Specifically, baseline embodied emissions are the sum of direct emissions from the facility (‘scope 1’) and embodied emissions of any CBAM-covered precursor inputs into the facility, thereby including some non-energy-related supply chain emissions (‘scope 3’) in the calculation. In addition, emissions from energy supply (‘scope 2’) are accounted for in the fertilizer and cement sectors10. Ideally, embodied emissions from CBAM-covered precursors should be determined using the same facility-specific baseline calculation. However, if facility-specific data for precursors are unavailable, up to 20% of the reported embodied emissions may be based on country-specific default values published by the European Commission11. These fallback default values currently represent average embodied emissions for product groups. After the transitional period, all fallback values will be increased by a mark-up, whose size is still to be determined (‘fallback calculation’, Fig. 1)10. The EU Commission’s proposed Omnibus I package17 (February 2025) would remove the 20% fallback cap, allowing more flexible use of fallback values.

All CBAM designs calculate embodied emissions using a facility-specific ‘baseline’ calculation and country-specific ‘fallback’ default values for cases in which primary data are unavailable. The designs differ in the strictness of fallback values and in the consideration of fossil feedstocks in the CBAM scope. All designs assume that the CBAM scope is extended to include chemicals. Scope 1, direct emissions from the facility; Scope 2, energy-related emissions (assumed to be covered for chemicals in this study, but not included for all sectors covered by the CBAM); Scope 3, remaining supply-chain emissions.

The EU CBAM10,18 currently does not include the organic chemical and polymer industries despite the fact that these industries are emitting 20% of the global industrial greenhouse gases19 and are regarded as at risk of carbon leakage by the EU6,14,20. While the EU debated expanding the CBAM scope to a number of organic base chemicals and polymers21, these products were ultimately excluded owing to technical limitations that prevent accurate calculation of their embodied emissions10. The rationale of the EU for the initial exclusion thus focuses on the feasibility of embodied emissions calculation at the beginning of the chemical supply chain. By contrast, the European Chemical Industry Council raises concerns about potential circumvention issues further downstream in the supply chain22.

Despite these concerns, the European Commission will reassess an extension of the CBAM to the chemical and polymer sectors as part of the full CBAM review at the end of the transitional period, that is, by the end of 2025, with the goal of including these sectors by 203010,23. While qualitative studies on the CBAM classify the polymer and chemical industries as at risk of carbon leakage6,14,20, and particularly complex24,25,26, current quantitative studies on CBAM design bypass the issue of embodied emissions determination by focusing on broad economic assessments across all sectors and assuming one uniform product per sector27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. Although these higher-level models offer valuable insights into overall trade impacts, industry competitiveness, welfare impacts in individual countries and carbon leakage mitigation rates, they lack the granularity needed to capture product-specific differences in embodied emissions—an aspect critical for accurately evaluating the effectiveness of the CBAM in the chemical sector.

Here we quantitatively assess whether the current EU CBAM is likely to accurately account for the emission intensity of non-EU chemicals and polymers. We focus on the beginning of the chemical supply chain, investigating products that were considered for CBAM inclusion during policy negotiations, in which the EU anticipates challenges in embodied emissions calculation. We quantify the performance of the EU CBAM in determining embodied emissions in imports of polyethylene and ethylene, the most-produced polymer and basic chemical, respectively. Using life-cycle assessment data for 4,470 chemical production facilities worldwide37 as a benchmark for embodied emissions, we study the capacity of the EU CBAM to calculate accurate embodied emissions for beginning-of-supply-chain chemicals.

Our analysis shows that the EU CBAM extended to the chemical sector covers approximately 50–60% of production chain emissions for ethylene and polyethylene production and qualitatively identifies emission intensity for polyethylene. However, we find perverse incentives in ethylene reporting. To improve the accuracy of embodied emissions calculations, the CBAM would need to include fossil feedstocks and refinery products and implement high fallback default values. We showcase that addressing these areas could substantially improve the CBAM emission coverage for beginning-of-supply-chain chemicals and polymers.

Results

Polyethylene production emissions covered by the CBAM

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over the full life cycle capture the climate impact of chemicals production. Today, the life-cycle emissions of non-EU polyethylene producers, on average, surpass those of EU producers (Extended Data Fig. 1). Our analysis of 512 non-EU polyethylene production facilities reveals a wide range in life-cycle emissions, with some facilities emitting up to 10 times more than the average (Fig. 2a). Emission-intensive outliers supply 7% of non-EU polyethylene, but account for 20% of the emissions. By contrast, such high emitters are not found in the EU, where life-cycle emissions are more evenly distributed.

A perfect CBAM would exactly match cradle-to-border GHG emissions. a, Embodied emissions for polyethylene under the chemicals covered plus the average fallback design. b, Embodied emissions for ethylene under the chemicals covered plus the average fallback design. c, Embodied emissions for ethylene under the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus the average fallback design. ‘Self-profiting reporting behaviour’ assumes that facilities supply baseline data only if it results in lower embodied emissions than the fallback value. Facilities are ordered by decreasing cradle-to-border life-cycle emissions.

Breaking down polyethylene production GHG emissions reveals that scope 3 emissions constitute the largest share at 80% (Extended Data Fig. 1), highlighting the substantial impact of precursor production on the overall life-cycle emissions. Energy-related scope 2 emissions contribute less at 17%, and direct scope 1 emissions are the smallest, averaging only 3%.

On the basis of these life-cycle GHG emissions data, we can calculate embodied emissions under the EU CBAM framework. The ‘chemicals covered plus average fallback’ design (Fig. 1) assumes that the CBAM scope includes all organic chemicals as classified by the EU Combined Nomenclature (CN) (Supplementary Section 3) but excludes fossil feedstocks and refinery products in line with the current CBAM practice for hydrogen38. As in the current CBAM, all CBAM designs in this study calculate embodied emissions using a facility-specific ‘baseline’ calculation and country-specific ‘fallback’ default values for cases in which primary data are unavailable (Fig. 1).

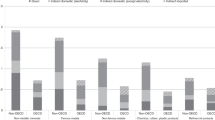

The baseline embodied emissions determined by the CBAM (Fig. 2a, dark green line) successfully identify high-emitting polyethylene producers and already cover 60% of polyethylene life-cycle emissions. Still, a substantial emission share is overlooked owing to incomplete coverage of scope 3 emissions under the CBAM. Specifically, the embodied emissions of chemical precursors such as ethylene do not accurately reflect their life-cycle emissions, leading to a 40% gap in emission coverage (Fig. 3a).

A perfect CBAM would exactly match cradle-to-border GHG emissions, achieving 100% emission coverage. ‘Baseline’ assumes that all facilities provide primary emission data. ‘Self-profiting reporting behaviour’ assumes that facilities supply baseline data only if it results in lower embodied emissions than the fallback value.

The fallback default values in the CBAM transitional period correspond to country averages11. Such averages underestimate emissions from high-emitting producers and overestimate those from low-emitting producers (Fig. 2a, light green line). The fallback contribution exceeds the current regulatory limit of 20% of reported embodied emissions for imported products owing to the large contribution of ethylene to the carbon footprint of polyethylene. Thus, under current rules, the fallback strategy would not be directly applicable to polyethylene imports.

However, the Omnibus I package17 proposed by the European Commission in February 2025 aims to remove the 20% cap on fallback value use. In line with this policy shift, the ‘self-profiting reporting behaviour’ design (Fig. 2a, hatched area) assumes that importers choose whichever value—baseline or fallback—is lower, that is, financially more favourable. Self-profiting reporting behaviour reduces emission coverage to 53%, creating a 7% gap due to the reliance on average fallback values (Fig. 3a).

Incomplete emission coverage due to chemical precursors

Ethylene is an important basic chemical at the beginning of the chemical and polymer supply chain and contributes 95% of scope 3 emissions in our dataset for polyethylene, making it central to the understanding of the 40% emission coverage gap attributed to incomplete scope 3 coverage. Unlike polyethylene, ethylene is not widely traded but produced and consumed locally, while its derivatives are globally traded and comprise over 40% of organic chemicals by volume39. However, it is worth noting that ethylene trading is currently increasing in certain regions, for example, the United States40.

The life-cycle GHG emission profile of ethylene resembles that of polyethylene, with scope 3 emissions being the largest contributor (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, for ethylene, scope 3 emissions stem from fossil feedstock precursors (43% of total ethylene life-cycle emissions) rather than chemical precursors (16%). This distribution affects emission coverage: facilities using chemical precursors such as methanol partially account for scope 3 emissions in embodied emissions calculations, while facilities using fossil feedstock precursors such as naphtha do not. Consequently, the chemicals covered plus average fallback baseline design (Fig. 2b, dark green line) does not reliably rank installations by life-cycle GHG emissions, as seen in the peak of baseline embodied emissions around a cumulative production volume of 90 Mt yr−1 (Fig. 2b). As Fig. 2a–c is ordered by decreasing life-cycle GHG emissions, such peaks in embodied emissions indicate potential perverse incentives, in which a lower-emitting facility faces higher embodied emissions than a higher-emitting facility. In the chemicals covered plus average fallback baseline design, we thus find a potential perverse incentive to adopt ethylene production processes with low scope 1 and 2 emissions, even if these processes use emission-intensive fossil feedstock precursors, leading to higher overall life-cycle emissions.

The chemicals covered plus average fallback baseline design achieves 51% emission coverage for ethylene (Fig. 3b). The coverage gap is larger than for polyethylene owing to a higher share of fossil feedstock-related emissions in ethylene. Assuming country-average fallback default values and self-profiting reporting behaviour, ethylene emission coverage drops to 39%, revealing an additional 12% gap (Fig. 3b).

Increasing emission coverage by including fossil feedstocks

To address the incomplete scope 3 coverage for chemicals and polymers, the ‘chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback’ design extends the CBAM scope to include fossil feedstocks and refinery products (‘fossil feedstocks’) such as coal, natural gas, naphtha and ethane (Fig. 1).

Applying the extended CBAM scope to ethylene production effectively resolves concerns regarding perverse incentives (Fig. 2c) and improves baseline emission coverage to 95% (Fig. 3b). As fallback default values are determined as averages, these default values also increase under the extended CBAM scope, which in turn improves emission coverage even under self-profiting reporting behaviour to 76%.

The improved emission coverage of ethylene production also positively impacts polyethylene embodied emissions (Extended Data Fig. 2): with the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback design, baseline emission coverage for polyethylene increases to 95% (+35%), and under self-profiting reporting behaviour, emission coverage improves to 83% (+30%) (Fig. 3a).

Overall, the more comprehensive scope 3 coverage improves the embodied emissions calculation throughout the supply chain. However, emission coverage gaps of 18% for ethylene and 12% for polyethylene remain owing to low reporting incentives from average fallback values.

Incentivizing data reporting with high fallback values

To discourage the use of fallback values, the EU plans to set these fallback values at high emission intensity levels38, with a mark-up on country-specific averages to be determined by the end of the transitional period11. The importance of mark-ups was reaffirmed in the Commission’s Omnibus I proposal17. Figure 4 explores this degree of flexibility in policy design: as the mark-up increases, more facilities are incentivized to report baseline embodied emissions based on primary data. Consequently, higher mark-ups effectively narrow the gap between self-profiting and baseline emission coverage. Our analysis reveals that the relationship between mark-up and incentivization is highly nonlinear: after an initial proportional phase where increasing the mark-up effectively raises coverage, a saturation phase is reached where a further increase in mark-up yields diminishing returns. This shows that while higher fallback values incentivize data reporting, their effectiveness is not linear, and excessively high mark-ups provide little additional benefit. We find that ethylene generally requires higher mark-ups than polyethylene to achieve similar incentivization levels (compare lines in Fig. 4), suggesting a need for product-specific mark-ups to achieve uniform reporting incentives across products. For instance, to incentivize 90% of facilities to provide primary data under a CBAM extended to chemicals, ethylene requires a 63% mark-up, while polyethylene needs only 21%. In general, products with greater emission disparities require higher mark-ups to achieve similar reporting incentives. Consequently, applying a uniform mark-up risks undermining the CBAM objective—levelling the playing field for products with substantial variability in embodied emissions. Conversely, applying high mark-ups to products with more uniform emission intensities could impose an unnecessary reporting burden.

As an alternative approach, we consider setting fallback values at the average embodied emissions level of the top 10% highest-emitting facilities per country, an approach discussed during CBAM negotiations21 (Fig. 1). This high fallback approach aims to reflect the emission intensity of the largest emitters.

Our analysis reveals that the high fallback approach offers both high emission coverage and reporting incentives. To achieve similar emission coverage using a mark-up, relatively high mark-ups (190–340%) are required (Extended Data Fig. 3). Conversely, lower mark-ups (50–140%) suffice to achieve a similar reporting incentivization rate (Fig. 4). The disparity arises because the high fallback approach accounts for country-specific variations in emission intensity. By contrast, a uniform mark-up applied to country averages is less effective in incentivizing data reporting in countries with a high variation in emission intensity. Country-specific mark-ups are needed to ensure consistent reporting incentives across countries, which would also lead to higher overall emission coverage. Our analysis indicates that a uniform mark-up high enough to increase overall reporting incentives would force all producers in most countries to either report primary data or rely on fallback default values that overcharge them—while only a few high-emitting producers would consistently benefit. This imbalance risks weakening the CBAM levelling effect. However, implementing country-specific mark-ups is controversial, as they could be perceived as discriminatory. Especially given that fallback values may only be used for up to 20% of the reported emissions, the diplomatic challenges must be carefully weighed, and further studies are needed to quantify these country-specific effects more precisely.

Discussion

Introducing the CBAM for chemicals and polymers appears to be a promising strategy for mitigating the recognized carbon leakage risks in these sectors. Our analysis shows that the EU CBAM already shows potential for beginning-of-supply-chain chemicals and polymers, by covering at least 50% of their production emissions in our case studies. However, CBAM emission coverage for organic chemicals and polymers can be further enhanced by addressing two gaps in the current policy framework:

First, the CBAM for chemicals and polymers would need to include fossil feedstocks and refinery products, given that a substantial share of chemical life-cycle emissions originates during the production of fossil feedstock precursors. Although currently not covered under EU CBAM legislation, the EU recognizes an elevated risk of carbon leakage in the fossil feedstocks and refinery products sector and plans to evaluate an extension of the CBAM scope to the sector by the end of the CBAM transitional period.

Including fossil feedstocks and refinery products in the CBAM scope would introduce technical and administrative complexities: the high level of integration of refinery processes, which yield a wide range of products simultaneously, complicates emission allocation to individual products. Addressing these allocation challenges is crucial for effective CBAM implementation. The LCA community has addressed similar challenges, developing robust allocation approaches for refinery products41,42 that adhere to the LCA International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards43,44. These approaches offer a promising starting point for CBAM design. Ultimately, the allocation approach selected by the EU must be transparent and accessible to refineries to accurately calculate their embodied emissions.

Extending the CBAM to fossil feedstocks and refinery products would also necessitate revising current embodied emissions calculations. For instance, current legislation assumes zero embodied emissions for natural gas used as a precursor in hydrogen production38. Consequently, updates would be required to maintain consistency under an expanded CBAM scope. Despite these complexities, expanding CBAM coverage to fossil feedstocks and refinery products is essential to eliminate perverse incentives identified in ethylene production. Furthermore, accurate coverage of fossil feedstock emissions is crucial to incentivizing the transition to renewable carbon sources in the chemical industry, such as CO2-based or bio-based production routes. Without proper coverage, fossil-based chemicals could retain an artificial cost advantage, as their true environmental costs are not reflected in the pricing. Similarly, carbon capture and storage will be effectively incentivized within the CBAM only if fossil feedstock emissions are properly accounted for.

The CBAM is designed to create a level playing field between EU and non-EU producers, but the exclusion of fossil feedstocks creates a critical misalignment with the EU internal carbon pricing framework. Within the EU, the ETS already regulates emission-intensive industries, including refineries, chemical production, and heat and electricity generation. Consequently, the vast majority of emissions from basic chemical supply chains operating within the EU are subject to the ETS. However, if the CBAM excludes fossil feedstocks from its scope, EU-based refineries would face a substantial disadvantage, bearing higher emission-related costs than their non-EU counterparts. This imbalance extends beyond refineries—our findings indicate that incorporating fossil feedstock precursors into the CBAM would enhance the accuracy of embodied emissions accounting throughout the supply chain, including for downstream products.

Second, setting fallback default levels at high levels of emission intensity is a theoretically sound approach to incentivize data reporting throughout supply chains. While fallback values may currently apply only to 20% of reported embodied emissions, this cap is proposed to be removed under the EU Commission’s Omnibus I package. This change would increase the relevance of fallback design for overall CBAM effectiveness, as the effects of low default values will accumulate along the intricate supply chains within the chemical industry. Recognizing the need for high default values, the EU introduced a mark-up on average fallback default values, the size of which remains to be determined. Our case studies suggest that product- and country-specific mark-ups would be necessary to achieve consistent data reporting incentives. Alternatively, fallback default values could be set at the average of the highest-emitting 10% of producers per product to ensure high emission coverage. However, fallback value design must balance multiple considerations beyond emission coverage. Setting high fallback default values could raise legal and diplomatic concerns, particularly if perceived as unfairly penalizing producers without verified emissions data (‘guilty until proven innocent’). Further studies should assess how to balance incentivization and diplomatic considerations.

A key consideration that warrants further attention is the current practice of grouping products by the EU CN codes when setting fallback values. This grouping approach could reduce CBAM emission coverage, as emissions can vary substantially across products within the same group—such as for the case of ethylene (Supplementary Section 2). Averaging fallback default values over such heterogeneous groups leads to the overcharging of producers of inherently lower-emission products and the undercharging of producers of high-emission products.

Our study’s focus on two products allows us to assess emission coverage but not the broader implications for carbon leakage. While 100% emission coverage is ideal, lower emission coverage levels may still effectively mitigate carbon leakage. However, determining a minimum threshold for effective mitigation would require advanced economic models5,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 that consider market mechanisms, locational advantages and other strategic factors beyond our study’s scope. More importantly, existing economic models commonly assume one uniform sector product, whereas our research underscores the variability in CBAM performance across different products. Without higher-resolution economic models that capture this variability, the relationship between emission coverage and carbon leakage rates cannot be quantified. Future research should therefore focus on refining the granularity of economic models to enable such assessments and to address complexities such as circumvention, which are crucial for the effective implementation of the CBAM for chemicals and polymers.

Although our study shows that accurate embodied emissions calculations can be achieved at the beginning of the chemical supply chain, challenges remain further downstream. The chemical industry’s complex and untransparent supply chains, with multiple production pathways leading to the same product, pose substantial circumvention risks if only parts of the supply chain are covered under the CBAM22. However, comprehensive coverage of the chemical industry would entail substantial administrative efforts owing to the vast array of final and intermediate products. Similar conclusions are drawn in a recent report by the Commission for Carbon Competitiveness26, which argues that supply chain complexity and the abovementioned allocation challenges make the CBAM unlikely to serve as a viable near-term solution for carbon leakage protection for chemicals. Experience from the fertilizer sector, currently covered under the CBAM, might offer valuable insights into potential circumvention issues and provide a useful reference for evaluating the extension of the CBAM to organic chemicals.

For the CBAM to cover large shares of emissions, precise supply chain tracking is a prerequisite. Traceable supply chains enable accurate embodied emissions calculation by producers and allow the EU to effectively verify reported embodied emissions and detect potential foul play. Finally, engaging chemical industry experts both now, in policy design, and during potential implementation, for monitoring and verification of reported embodied emissions, is crucial to ensuring the reliability of emission data and, thus, the efficacy of the CBAM.

Methods

Input data

The data for our case study are based on industry emission data from 4,470 chemical production facilities worldwide, each producing basic chemicals or polymers. Facility-specific life-cycle emission data are obtained from the cm.chemicals database, which is derived from commercial industry databases and covers over 95% of polyethylene and ethylene production globally37 The cm.chemicals database also comprehensively represents production within the EU.

From the cm.chemicals database, we selected all facilities producing the considered products ethylene and polyethylene. Furthermore, we include emission data for additional products needed to calculate fallback default values: the EU CBAM default values are determined as averages per CN code, that is, multiple products may share the same default value although they differ in life-cycle emissions10 Our dataset thus includes not only ethylene and polyethylene facilities, but also all facilities producing propylene, butadiene, butene, isoprene, benzene and other C4 chemicals, which all share a CN code with ethylene. This averaging lowers the default values for ethylene compared with a separate accounting (details are discussed in Supplementary Section 2). The chemicals and polymers in our dataset represent the current production and are therefore based on fossil resources. Potential future supply chains based on CO2 and biomass as well as carbon capture and storage are not considered.

For each facility in our dataset, the input data comprise information on products, production process, country, annual production volume in the reference year 2017 and life-cycle GHG emissions per kg of product. Emission data are resolved by product and divided into emission scopes according to the method described in Supplementary Section 3. For chemical processes with multiple products (for example, steam crackers), emissions are allocated to individual chemical products according to the products’ energy content, that is, their lower heating values37.

For additional data on fossil feedstock production emissions (see also ‘Baseline embodied emissions calculation’ section below), we use the ecoinvent database, v.3.10 (ref. 45). In ecoinvent, emissions from multi-product refineries are also allocated to individual products based on the products’ energy content, that is, their lower heating values41. This approach is in line with the ISO standards for LCA43,44. Allocation is performed at the process step level, ensuring the consideration of the complex network of refinery processes41.

Life-cycle emissions calculation

Life-cycle emissions in our study are derived from established LCA databases that follow the ISO-standardized LCA43,44 methodology. LCA is the common scientific method to evaluate the environmental impacts of chemical processes46. While we use LCA data for embodied emissions calculations, our study is not a full LCA study but rather an analysis based on existing LCA results for individual chemical facilities. For instance, LCA usually assesses impacts across a range of environmental impact categories, whereas our study focuses on the climate change impact category using GWP100 according to the IPCC 2013 method47. Specifically, we consider GHG emissions in all life-cycle stages up to the finished product imported into the EU (‘cradle to gate’). For each facility, impact assessment results are reported in the Carbon Minds database for a functional unit of 1 kg of chemical product at the facility. We exclude transport emissions for the import into the EU.

Baseline embodied emissions calculation

Here we present the calculation rules of embodied emissions for the designs introduced in Fig. 1. In our calculations, we distinguish between chemical and fossil feedstock precursors according to the EU CN classification48. A list of relevant precursors for the ethylene and polyethylene case studies is provided in Supplementary Section 3. For all studied designs, we assume that scope 2 emissions are covered by CBAM for organic chemicals and polymers, similar to the approach in the fertilizer sector.

In the chemicals covered (cc) design, we calculate baseline embodied emissions for each facility f according to equation (1):

where \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f/p}^{{\rm{cc}}}\) denotes embodied emissions for facility f/chemical precursor p according to the chemicals covered designs, \({\rm{E{m}}}_{f}^{{\rm{scope}}\,{x}}\) denotes emissions of scope x related to facility f, Pf is the set of chemical precursor inputs p into facility f, mp is the mass of chemical precursor input p into facility f and F is the set of all facilities f.

We calculate facility-specific baseline embodied emissions for the chemicals and feedstocks covered (cfc) designs according to equation (2):

where \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f/p/q}^{{\rm{cfc}}}\) denotes embodied emissions for facility f/chemical precursor p/fossil feedstock precursor q according to the chemicals and feedstocks covered designs, \({\rm{E{m}}}_{f}^{{\rm{scope}}\,{x}}\) denotes emissions of scope x related to facility f, Pf is the set of chemical precursor inputs p into facility f, Qf is the set of fossil feedstock precursor inputs q into facility f, mp/q, is the mass of chemical precursor input p/fossil feedstock precursor input q into facility f and F is the set of all facilities f.

As our input data comprise only the total life-cycle GHG emissions \({\rm{E{m}}}_{q}^{{\rm{LCA}}}\) for fossil feedstock precursors, we must assume a ratio α of life-cycle emissions covered by the CBAM to determine the embodied emissions of fossil feedstock precursors \({\rm{E{E}}}_{q}^{{\rm{cfc}}}\) according to equation (3):

where \({\rm{E{E}}}_{q}^{{\rm{cfc}}}\) denotes embodied emissions for fossil feedstock q according to the chemicals and feedstocks covered designs, \({\rm{E{m}}}_{q}^{{\rm{LCA}}}\) denotes life-cycle GHG emissions for fossil feedstock q (scopes 1 through 3) and α is the ratio of life-cycle emissions covered by the chemicals and feedstocks covered designs.

As detailed data source on fossil feedstock production emissions, ecoinvent was used, the largest available life-cycle assessment database45. Using ecoinvent data, we recursively apply equation (2) to all relevant fossil feedstock production processes (compare Supplementary Section 4) to then determine α as an average (equation (4)):

where α is the ratio of life-cycle emissions covered by the CBAM, \({\rm{E{E}}}_{q}^{{\rm{cfc}}}\) denotes embodied emissions for fossil feedstock q according to the chemicals and feedstocks covered designs, \({\rm{E{m}}}_{q}^{{\rm{LCA}}}\) denotes life-cycle emissions for fossil feedstock q (scopes 1 through 3) and Q is the set of fossil feedstock precursors q relevant to our case study.

Our assumption is thus that about 90% of life-cycle emissions from fossil feedstock precursor production are covered by the CBAM in the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback design. The remaining 10% are contributed mainly by infrastructure such as pipeline or plant construction and related processes.

Fallback embodied emissions calculation

For average fallback designs without mark-up, the calculation of fallback default embodied emissions values involves filtering the full set of chemical facilities based on product group and location and averaging the baseline embodied emissions for the filtered facilities. The process can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Dataset filtering according to the rules specified in the EU CBAM

-

a.

We filter the datasets according to product groups using the CN code.

-

b.

We select the facilities from the exporting country.

-

a.

-

(2)

Production-volume weighted averaging:

For the subset of chemical facilities remaining after step 1, we use production-volume weighted averaging of baseline embodied emissions (equation (5), applied analogously for the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback design).

where \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f}^{{cc},{\rm{fallback}}}\) denotes embodied emissions according to the chemicals covered plus average fallback design for facility f; Fc,CN ⊂ F denotes the subset of facilities f that obey the filter criteria, that is, produce products in CN code CN and located in country c; prodVolf is the production volume of facility f; and \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f}^{{\rm{cc}}}\) denotes baseline embodied emissions of facility f according to the chemicals covered design.

Per the EU CBAM regulation, fallback default values for emission embodied in products are set at a country-specific average emission intensity, increased by a proportional mark-up10. The size of the mark-up will be determined in the implementing acts, based on information gathered during the transitional period of the CBAM.

To explore the influence of the mark-up on the emission coverage in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 3, we use equation (6) to determine fallback default values with the mark-up mechanism (applied analogously for the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback design):

where \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f}^{{\rm{cc}},{\rm{fallback}}\; {\rm{with}}\; {\rm{mark}}{\text{-}}{\rm{up}}\,\mu }\) denotes fallback embodied emissions for facility f according to the chemicals covered plus average fallback design, increased by a proportional mark-up μ; μ is the value of mark-up; and \({\rm{E{E}}}_{f}^{{\rm{cc}},{\rm{fallback}}}\) denotes fallback embodied emissions for facility f according to the chemicals covered plus average fallback design.

With increasing mark-up, fallback values increase, and more facilities are incentivized to provide baseline embodied emissions data. In addition, we calculate incentivization rates of high fallback designs and depict them as blue circles (chemicals covered) and orange triangles (chemicals and feedstocks covered) to provide a point of reference as to how high mark-ups would need to be set to achieve similar incentivization rates.

We repeat this calculation for various mark-up rates μ.

The high fallback CBAM designs are modelled after an approach proposed during policy negotiations21, in which fallback default values are determined as the average of the baseline embodied emissions for the 10% highest-emitting facilities per country (compare with Fig. 1).

We apply high fallback values to both the chemicals covered and the chemicals and feedstocks covered design. In both cases, the baseline design remains identical (compare equations (1) and (2)). For the fallback default value determination, however, a second filtering step is applied in addition to the calculation procedure for average fallbacks. The procedure for determining high fallback values is:

-

(1)

First filtering (identical to the approach described for average fallbacks)

-

By product group (using the CN code)

-

By importing country

-

-

(2)

Second filtering of the remaining subset

The chemical facilities remaining after step 1 are sorted based on the calculated baseline embodied emissions, and the 10% worst-performing facilities are selected21.

-

(3)

Production-volume weighted averaging of embodied emissions (identical to the approach described for average fallbacks) for the facilities remaining after steps 1 and 2 yield the fallback default values.

Self-profiting reporting behaviour

In a CBAM incorporating fallback values, the embodied emissions actually applied to imports depend on the reporting behaviour of importers, who might not have access to emission data themselves or have a monetary incentive to withhold emission data if their actual embodied emissions are higher than the corresponding default value. Our underlying assumption for the ‘self-profiting reporting behaviour’ is that facilities have knowledge of their emissions but will report their emissions only if they have a monetary incentive to do so. For facilities that do not report emission data, we apply embodied emissions according to the fallback design. The self-profiting reporting behaviour design, therefore, acts like a cut-off, in which facilities will be charged for fallback embodied emissions or less (equation (7), applied analogously for the chemicals and feedstocks covered plus average fallback design).

For the calculations including a mark-up on fallback default values, self-profiting reporting behaviour embodied emissions are calculated analogously.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

We sourced the input data for our analysis from the cm.chemicals database by Carbon Minds, which requires a specific license. Please contact Carbon Minds directly via email at info@carbon-minds.com for more information on the full dataset. In addition, we used background data from the ecoinvent database v.3.10 (www.ecoinvent.org), which is available under license. A minimum working subset of the input dataset and aggregated data for the full input dataset are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15059496 (ref. 49).

Code availability

Calculations according to online methods were performed using Python. The code used to conduct our analysis is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15059496 (ref. 49).

References

Shukla, P. R., Skea, J. & Reisinger, A. (eds) Climate Change 2022. Mitigation of Climate Change (IPCC, 2022).

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris Agreement (United Nations, 2015).

Grubb, M. et al. Carbon leakage, consumption, and trade. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 753–795 (2022).

European Commission. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/708 of 15 February 2019 supplementing Directive 2003/87/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council concerning the determination of sectors and subsectors deemed at risk of carbon leakage for the period 2021 to 2030. OJEU 120, 20–26 (2019).

Fontagné, L. & Schubert, K. The economics of border carbon adjustment: rationale and impacts of compensating for carbon at the border. Annu. Rev. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-082322-034040 (2023).

Leonelli, G. C. Practical obstacles and structural legal constraints in the adoption of ‘defensive’ policies: comparing the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the US Proposal for a Border Carbon Adjustment. Legal Stud. 42, 696–714 (2022).

Greening Imports: A UK Carbon Border Approach HC 737 (UK House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, 2022).

Department of Finance Canada. Exploring Border Carbon Adjustments for Canada (Digital Transformation Office, 2021); https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/consultations/2021/border-carbon-adjustments/exploring-border-carbon-adjustments-canada.html

Ramseur, J. L., Murrill, B. J. & Casey, C. A. Border Carbon Adjustments: Background and Recent Developments R47167 (Congressional Research Service, 2022).

European Parliament and European Council. Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism. OJEU 130, 52–104 (2023).

European Commission. Commission implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/1773 of 17 August 2023 laying down the rules for the application of Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards reporting obligations for the purposes of the carbon border adjustment mechanism during the transitional period. OJEU 228, 94–195 (2023).

Cosbey, A., Droege, S., Fischer, C. & Munnings, C. Developing guidance for implementing border carbon adjustments: lessons, cautions, and research needs from the literature. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 13, 3–22 (2019).

Dröge, S. & Fischer, C. Pricing carbon at the border: key questions for the EU. ifo DICE Rep. 18, 30–34 (2020).

Ismer, R. & Neuhoff, K. Border tax adjustment: a feasible way to support stringent emission trading. Eur. J. Law Econ. 24, 137–164 (2007).

Weisbach, D., Elliott, J., Foster, I., Kortum, S. & Munson, T. Unilateral carbon taxes, border tax adjustments and carbon leakage. Theor. Inq. Law https://doi.org/10.1515/til-2013-012 (2013).

Mehling, M. A. & Ritz, R. A. From theory to practice: determining emissions in traded goods under a border carbon adjustment. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 39, 123–133 (2023).

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/956 as Regards Simplifying and Strengthening the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism COM(2025) 87 final (European Commission, 2025).

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism COM/2021/564 (European Commission, 2021).

Global Chemicals Outlook II. From Legacies to Innovative Solutions. Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations Environment Programme, 2019).

Böhringer, C., Fischer, C., Rosendahl, K. E. & Rutherford, T. F. Potential impacts and challenges of border carbon adjustments. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 22–29 (2022).

Amendments Adopted by the European Parliament on 22 June 2022 on the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (COM(2021)0564 - C9-0328/2021 - 2021/0214(COD)) P9_TA(2022)0248 (European Parliament, 2022).

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) Proposal Needs Upgrading for Chemicals Position Paper (European Chemical Industry Council (CEFIC), 2022).

European Parliament. Deal Reached on New Carbon Leakage Instrument to Raise Global Climate Ambition (2022); European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20221212IPR64509/deal-reached-on-new-carbon-leakage-instrument-to-raise-global-climate-ambition

Meyer, T. & Tucker, T. N. A pragmatic approach to carbon border measures. World Trade Rev. 21, 109–120 (2022).

Kortum, S. & Weisbach, D. The design of border adjustments for carbon prices. Natl Tax J. 70, 421–446 (2017).

Policies to Achieve Industrial Decarbonization in Sectors Facing Competitiveness Risks (Comission on Carbon Competitiveness, 2024).

Beaufils, T., Ward, H., Jakob, M. & Wenz, L. Assessing different European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism implementations and their impact on trade partners. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 131 (2023).

Yang, C. & Yan, X. Impact of carbon tariffs on price competitiveness in the era of global value chain. Appl. Energy 336, 120805 (2023).

Zhong, J. & Pei, J. Beggar thy neighbor? On the competitiveness and welfare impacts of the EU’s proposed carbon border adjustment mechanism. Energy Policy 162, 112802 (2022).

Rocchi, P., Serrano, M., Roca, J. & Arto, I. Border carbon adjustments based on avoided emissions: addressing the challenge of its design. Ecol. Econ. 145, 126–136 (2018).

Fischer, C. & Fox, A. K. Comparing policies to combat emissions leakage: border carbon adjustments versus rebates. J. Env. Econ. Manag. 64, 199–216 (2012).

Mörsdorf, G. A simple fix for carbon leakage? Assessing the environmental effectiveness of the EU carbon border adjustment. Energy Policy 161, 112596 (2022).

Bellora, C. & Fontagné, L. EU in search of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Energy Econ. 123, 106673 (2023).

Takeda, S. & Arimura, T. H. A computable general equilibrium analysis of the EU CBAM for the Japanese economy. Jpn. World Econ. 70, 101242 (2024).

Zhu, J., Zhao, Y. & Zheng, L. The impact of the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on China’s exports to the EU. Energies 17, 509 (2024).

Perdana, S., Vielle, M. & Oliveira, T. D. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: implications on Brazilian energy intensive industries. Clim. Policy 24, 260–273 (2024).

Kätelhön, A. et al. Methodology cm.chemicals (Carbon Minds, 2021).

European Commission. Guidance Document on CBAM Implementation for Installation Operators Outside the EU (Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union, 2023).

Chenier, P. J. in Survey of Industrial Chemistry 3rd edn (ed. Chenier, P. J.) 143–162 (Springer, 2002).

Simoes, A. J. G. & Hidalgo, C. A. The economic complexity observatory: an analytical tool for understanding the dynamics of economic development. In Proc. 25th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (eds Johnston, B. & Williams, M.-A.) 39–42 (AAAI, 2011).

Fehrenbach, H. et al. Life Cycle Inventories of Petroleum Refinery Operation for the SRI Project (Institut für Energie- und Umweltforschung, 2018).

Jungbluth, N., Meili, C. & Wenzel, P. Life Cycle Inventories of Oil Refinery Processing and Products (ESU-services, 2018).

ISO 14040:2006: Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework 14040th edn (International Organization for Standardization, 2020).

ISO 14044:2006: Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines 14044th edn (International Organization for Standardization, 2020).

Wernet, G. et al. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 21, 1218–1230 (2016).

Jessop, P. Editorial: Evidence of a significant advance in green chemistry. Green Chem. 22, 13–15 (2020).

IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

European Union. Corrigendum to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/1832 of 12 October 2021 amending Annex I to Council Regulation (EEC) No 2658/87 on the tariff and statistical nomenclature and on the Common Customs Tariff. OJEU 64, (2021).

Minten, H. Embodied emissions calculations for chemicals according to various CBAM designs. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15059496 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors received no dedicated funding for this study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing and visualization. J.H.: conceptualization, methodology and data curation. B.P.: conceptualization and writing—review and editing. C.R.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, and supervision. R.M.: conceptualization, methodology, data provision, and writing—review and editing. A.B.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.B. and R.M. have ownership interests in Carbon Minds, the company supplying the data used for this study. A.B. has served on review committees for research and development at ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies, oil and gas companies that are also active in chemicals and polymer production. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Jasmin Cooper, Aaron Cosbey and Yvonne van der Meer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of polyethylene production.

Cradle-to-border life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of polyethylene facilities in- and outside the EU over their production volume in order of decreasing emissions. For non-EU producers, emissions are separated into “Scope 1” - direct emissions from the facility, “Scope 2” - energy-related supply-chain emissions, and “Scope 3” - remaining supply-chain emissions. Scope 3 emissions from fossil feedstock precursors are hatched, although no such emissions are present in this polyethylene emission profile.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Emission profile: Chemicals & feedstocks covered + average fallback – Polyethylene.

Embodied emissions of non-EU ethylene facilities calculated from cradle-to-border greenhouse gas emission data according to the chemicals & feedstocks covered + average fallback design. A perfect CBAM would cover cradle-to-border greenhouse gas emissions exactly. “Self-profiting reporting behavior” assumes that facilities supply baseline data only if it results in lower embodied emissions than the fallback value.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Emission coverage under varying mark-up on fallback default values.

Emission coverage under self-profiting reporting behavior as a function of the mark-up applied to fallback values. With increasing mark-up, more facilities are incentivized to provide baseline embodied emissions data. Consequently, the self-profiting reporting behavior emission coverage approaches the baseline design emission coverage.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–7, terms and definition, data preparation procedure, calculation details, critical discussion and sensitivity analysis on fossil feedstock data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Minten, H., Hausweiler, J., Probst, B. et al. Embodied emissions of chemicals within the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. Nat Sustain 8, 1381–1390 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01618-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01618-5