Abstract

Building damage poses serious safety risks, causing substantial financial losses worldwide. Engineering shortcomings are commonly cited as the cause of long-term structural failures, often neglecting the exacerbating role of land subsidence. Here we used satellite radar observations during 2015–2023 to estimate differential settlements at 5 fast-growing Indian megacities, including more than 13 million buildings and 80 million people. Our analysis reveals 878 km² of land subsiding, exposing ~1.9 million people to subsidence rates of more than 4 mm yr−1. An estimated 2,406 buildings across Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai are at high risk of structural damage from ongoing land subsidence. Sustained over 50 years, current subsidence rates could place as many as 23,529 buildings at very high risk of structural damage in Chennai, Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Bengaluru. Our results highlight the compounding risk of infrastructure damage from subsidence, assisting policymakers to develop resilience plans and adaptation strategies that prioritize mitigation and maintenance spending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Across the globe, building collapses emerge as a recurring disaster, causing substantial loss of lives and properties1. Between 1970 and 2020, more than 180 disastrous building collapse events were reported worldwide, killing more than 330 people per year on average1. These tragic incidents are not immediately related to seismic events or climate extremes but are most prevalent in developing countries. For instance, in 2013, a residential structure in Mumbai collapsed, leading to at least 61 fatalities and injuring 32 people2. The same year, Bangladesh witnessed one of the deadliest building collapses in history when Rana Plaza in Dhaka fell, resulting in 1,134 deaths and injuring more than 2,500 individuals3. In September 2014, a church building collapsed in Lagos, Nigeria, claiming 115 lives4. On 19 March 2019, a building complex in Dharwad, Karnataka, collapsed, causing 19 deaths and 82 injuries5. In November 2021, the failure of a high-rise building in Lagos, Nigeria, led to 42 deaths6. These tragic incidents of building collapse underscore the lethal impact of building structural damage. Their causes are often identified in the aftermath of an event and attributed to a range of interrelated factors that weaken the structural stability, such as poor design standards and materials7, age and wear8, inadequate maintenance9, adjacent excavations10, soil issues11, foundation movements7, and exposure to natural hazards such as floods, hurricanes12 and land subsidence13,14,15,16. Even though land subsidence alone does not directly cause building collapse, its compounding effect and potential to cause long-term structural weakening are often ignored or overlooked when designing new infrastructure or planning maintenance, despite its prevalence in more than 150 cities globally17.

Differential land settlement refers to the uneven vertical displacement of adjacent ground surfaces, resulting in spatially variable deformation. This phenomenon is often most pronounced at the boundaries of high-subsidence or uplift zones, where the displacement gradient is large. However, differential subsidence also occurs across the interior of a subsiding region, the so-called subsidence bowl, due to localized geotechnical heterogeneity. It is particularly notable in environments with rapidly varying soil properties over short distances: for example, in drained coastal plains where stratified layers of sand, clay and organic material exhibit differing compressibility and consolidation behaviours18. Differential settlement introduces non-uniform ground deformation, which imposes varying stress distributions on overlying structures, thereby increasing the likelihood of foundation distress, structural weakening and long-term strain accumulation18,19,20,21,22. Moreover, differential settlement acts as a compounding stressor that magnifies the impact of other factors contributing to severe building damage19,20. When structures experience uneven ground movement, stress concentrations form, weakening load-bearing components and promoting cracking in foundations and walls21. The risks intensify when compounded by poor construction practices, ageing infrastructure, increased loading, seismic events, fluctuating groundwater levels or extreme weather events. In earthquake-prone areas, for example, differential settlement may impair a building’s capacity to absorb seismic forces, increasing collapse risk22. In flood-prone regions, it can alter drainage patterns or damage essential utilities, heightening vulnerability23. Therefore, even though differential subsidence may not directly threaten structural integrity, it synergistically interacts with other risk factors, exacerbating deterioration. For example, in 2023, differential settlement was widely reported as contributing to the structural damage and cracks observed in ~800 buildings in the Himalayan city of Joshimath, India16. There are likely many more instances of structure weakening promoted by differential subsidence. However, subsidence observation is typically unavailable at a resolution required to resolve differential settlements surrounding buildings. Thus, the link between differential land subsidence and structure weakening that promotes building damage remains elusive.

Various natural and anthropogenic processes17 drive land subsidence, with aquifer and sediment compaction being the chief factors. Aquifer compaction is commonly due to reduced water pressure within aquifers owing to groundwater overexploitation24. Aquifer systems have become increasingly stressed globally25, accelerating aquifer compaction worldwide. The demand for groundwater is often driven by reduced surface water supply due to extreme droughts and increased water demand due to population growth and socioeconomic development stresses. Currently, more than 0.9 billion of the global urban population reside in water-stressed regions, and projections indicate that in 2050, nearly 2.3 billion city dwellers will be exposed to water shortage26. The compounding effects of a changing climate, population growth and human management decisions might exacerbate groundwater pumping-related subsidence worldwide27. Additionally, reservoir rock compaction can result from hydrocarbon extraction28, and its occurrence is likely to increase in the future to meet India’s growing energy demands.

The world’s largest urban population resides in India, where nearly 0.2 billion people live in the cities. Five Indian megacities, Delhi (National Capital Territory, NCT), Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Chennai (Fig. 1a–e), comprise a population of 83 million29. The country’s population continues growing at a rate of 0.92% as of 202430. By ~2030, Delhi is projected to surpass Tokyo as the world’s largest megacity, and India is projected to witness the emergence of two additional megacities29. India’s population growth can worsen the severe water scarcity that many urban areas face26.

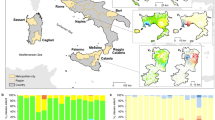

a–e, Satellite images of five Indian megacities: Delhi (a), Mumbai (b), Bengaluru (c), Chennai (d) and Kolkata (e) and an overview of their location in India (centre). The red (orange) rectangles indicate frames from ascending (descending) Sentinel-1A/B flight orbits that were used to generate VLM for each megacity. Supplementary Table 2 provides the path and frame numbers of Sentinel-1 data. Coloured variably sized circles indicate 26 building collapses that occurred between 1989 and 2023 and killed or injured about 351 and 320 people, respectively. The size of the circles corresponds to the number of reported deaths, and the colour indicates the number of individuals who sustained injuries. The displayed locations of collapses are approximate. This information on these incidents was collected from online media outlets and is summarized in the source data file63. It is important to note that although differential subsidence can compromise the structural integrity of buildings, there is no proven direct link to collapses. However, it can contribute to failure when combined with other factors, such as engineering and design flaws, poor maintenance, and the impact of other natural hazards. f, Monthly TWS change in centimetres of an equivalent water column for each megacity region measured by GRACE/GRACE-FO mission between 2002 and 2023. The rate of TWS change and associated uncertainty were estimated using linear regression and single-spectrum analysis, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). g, Time series of depth to groundwater in metres at selected groundwater well sites in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Chennai. Maps in a–e generated with QGIS 3.34 and ArcMap 10.8. Hillshade map from USGS SRTM 1arc DEM product. Credit: satellite images in a–e, Esri, USGS | Esri, TomTom, FAO, NOAA, USGS | Earthstar Geographics.

Surface water supply and groundwater demand in India critically depend on monsoon precipitation for replenishment31. However, observed shifts in the monsoon dynamics, characterized by a delayed onset and earlier offset, coupled with variable precipitation intensities, have exerted considerable stress on aquifers in recent decades31. These changes result in reduced recharge rates and periods, which affect the resilience of groundwater resources and heighten the vulnerability of aquifers to overexploitation. Groundwater head in major aquifer systems of India has been consistently decreasing, including those in megacities32, as shown in some representative wells with historical data (Fig. 1g). The decline in terrestrial water storage (TWS) captured via satellite gravimetry33 for the cities’ broader regions, points to a substantial issue of diminishing water reserves. The Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment and its follow-on (GRACE/GRACE-FO) mission-based TWS estimates comprises storage change in all compartments of the water cycle, including soil, surface water, groundwater and snow water at a spatial resolution of ~300 km. Seasonal variations in TWS, introduced by annual changes in each compartment, are typically dominated by soil moisture34. A fast and intense multiyear or longer-term decline in TWS, however, is often underlain by intense and regionally widespread groundwater overdraft35 (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 1).

Declining groundwater head often leads to land subsidence, a phenomenon that has been reported for several Indian megacities36,37,38,39. This raises the concern that differential land subsidence promotes structure weakening and potential building damage. Although India introduced a National Building Code in 1970 to ensure safety standards for new construction, it lacked formalized criteria for assessing the safety and resilience of buildings after construction until 201740.

Here we investigate the occurrence and implications of differential land subsidence in the five Indian megacities: Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Chennai. For that, we implement a cutting-edge spaceborne multitemporal Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) algorithm and analyse Sentinel-1 C-band SAR images between 2015 and 2023 to obtain high-resolution and accurate spatiotemporal maps of vertical land motion (VLM) over the studied megacities. Using these datasets, we present the individual building-level maps of angular distortion and building damage risk for Indian megacities. We further assess the accumulation of VLM rates over several decades to generate ‘undefended’ scenarios of differential land subsidence for each megacity and evaluate the potential building damage risk if no subsidence mitigation and adaptation strategies are implemented.

Results

Land subsidence in Indian megacities

Utilizing 1,299 Sentinel-1 SAR images, including 15 frames, we generated high-resolution VLM rates for 5 Indian megacities (Fig. 1): Delhi (2015–2023), Mumbai (2015–2023), Bengaluru (2019–2023), Chennai (2015–2020) and Kolkata (2017–2023). The dataset encompasses ~0.5 million elite pixels (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The SAR images were processed using an advanced multitemporal InSAR algorithm to generate high-resolution maps of VLM rates for each city (Methods).

a–e, InSAR VLM rate maps observed in Delhi (a; 2015–2023), Mumbai (b; 2015–2023), Bengaluru (c; 2019–2023), Chennai (d; 2015–2020) and Kolkata (e; 2017–2023). The maps include ~0.5 million pixels each, corresponding to an average ~75 m resolution. f, The empirical cumulative distribution function of VLM rates for all observed data pixels in each megacity. g, VLM distribution in each megacity, showing the percentage of area falling within specific VLM categories. h, Boxplot statistics of VLM rates for each Indian megacity. Boxplots display the median (central line), interquartile range (IQR; 25th–75th percentiles, box bounds), whiskers extending to 1.5 × IQR and outliers as individual points. Minimum and maximum values are also indicated. The sample sizes were n = 182,817 (Delhi), n = 146,648 (Mumbai), n = 64,286 (Kolkata), n = 94,376 (Chennai) and n = 63,464 (Bengaluru). Mean rates of VLM for Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata are −0.8 ± 2.2 mm yr−1, −0.8 ± 1.2 mm yr−1, −0.7 ± 1.7 mm yr−1, −0.7 ± 2.8 mm yr−1 and −2.2 ± 1.8 mm yr−1, respectively. Maximum, minimum and mean VLM rates for the smallest administrative divisions in India, namely wards, are provided in Supplementary Tables 3–7. i,j, Treemap charts showing population exposed to different VLM categories estimated using the WorldPop 100-m gridded population dataset74. Almost 1.9 million (M) people in Indian megacities are exposed to subsidence of more than 4 mm yr−1. Maps in a–e generated with MATLAB R2023a. Credit: basemaps in a–e, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

We found widespread subsidence in all cities, with maximum rates of 51.0 mm yr−1, 31.7 mm yr−1, 26.1 mm yr−1, 16.4 mm yr−1 and 6.7 mm yr−1 for Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai, Kolkata and Bengaluru, respectively (Fig. 2g). Additionally, we identified subsidence hotspots in most cities (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 3–6). For instance, rates of up to 28.5 mm yr−1, 38.2 mm yr−1 and 20.7 mm yr−1 affected areas of Bijwasan, Faridabad and Ghaziabad, in Delhi (Fig. 2a). In Chennai, the fastest subsidence rates surround flood plains of the Adyar River and city centre areas, including Valasaravakkam, Kodambakkam, Alandur and Tondiarpet (Fig. 2d). We also identified localized uplift in some cities, such as areas near Dwarka, Delhi that are rising at a rate of 15.1 mm yr−1 (Fig. 2a). The VLM empirical cumulative distributions (Fig. 2f) indicate that 31,373 (17.16%, 196.27 km2), 41,937 (28.59%, 262.36 km2), 19,240 (30.31%, 120.37 km2), 12,198 (12.92%, 76.31 km2) and 35,632 (55.42%, 222.91 km2) pixels in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata, respectively, are affected by subsidence after accounting for uncertainty (one standard deviation) (Fig. 2f). Only pixels with VLM values more negative than the uncertainty threshold are classified as subsiding. Figure 2g,h provides the statistics for VLM results obtained for each city, and Fig. 2i,j displays the population exposed to different levels of VLM. The seasonal amplitude of VLM is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

In Delhi (Fig. 2a,g), the primary driver of land subsidence is the compaction of alluvial deposits caused by extensive groundwater withdrawals37,41 (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, the localized uplift in ward Dwarka (Supplementary Fig. 4) is attributed to aquifer recharge, facilitated by strict government regulations implemented between the mid-2000s and 2011, which curtailed groundwater pumping, promoted rainwater harvesting and supported the revival of an old water body between 2012 and 2015, thereby mitigating strain on groundwater resources and enhancing recharge37,42. In Chennai, the widespread subsidence observed in the city centre can be attributed to the compaction of alluvium deposits from Holocene fluvial sediments, especially in the floodplain of the Adyar River (Fig. 2d), characterized by sandy clay, silt and sand. In addition, the two major hotspots of subsidence (K.K. Nagar and Tondiarpet) in Chennai can be related to groundwater extraction (Supplementary Fig. 5). The VLM rate in Kolkata broadly agrees with that of earlier studies39, and minor discrepancies are likely due to differences in the observation period. The observed subsidence pattern in Kolkata may be attributed to the compaction of Pleistocene and Holocene sediments. In Bengaluru, the widespread presence of igneous and metamorphic rocks such as gneiss, granodiorites and granite may also be responsible for the relatively minimal subsidence witnessed (Fig. 2c,g). However, there was an increase in the extraction of groundwater in Bengaluru towards the end of 2022, which can be derived from a comparison of groundwater level and deformation time series (Supplementary Fig. 6). Subsidence is notably lower in the majority of Mumbai except in economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods (for example, Dharavi) with high-density informal settlements (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition to the potential compaction resulting from extensive groundwater extraction through millions of unregulated borewells, Indian megacities may also experience subsidence due to the cumulative weight of the urban structures above43.

Angular distortion hazards

Angular distortion hazard, the ratio of differential subsidence to the horizontal distance over which subsidence occurs, can cause damage to infrastructure, increasing the risk of building damage19,44,45,46,47. Here we oversampled the InSAR VLM annual rates to the vertices of individual buildings and computed the angular distortion annual rate (β) for each building and then scaled it with the observation period of 2015–2023 to retrieve the total angular distortion (βtot); see Methods for details. We displayed the results in four categories: low, medium, high and very high total angular distortion hazards (Supplementary Fig. 8a–e). We found that in Delhi, 2,718 (0.055%) buildings are exposed to medium hazards. In comparison, 167 buildings in Mumbai are affected by a combination of medium, high and very high hazards (Supplementary Table 8). Approximately 39 buildings in Chennai are in the medium hazard category, having βtot ranging from 0.0006 rad to 0.02 rad. All of Bengaluru and Kolkata fall within the low hazard category.

We created various distortion angle hazard accumulation scenarios, assuming differential subsidence continues sublinearly. For simplicity, we present these scenarios as future projections, assuming subsidence began at the start of the InSAR measurement period for each city. However, they can be similarly applied to any period. To this end, we estimated and categorized βtot for 10 years (near future; Supplementary Fig. 9a–e), 30 years (intermediate future; Supplementary Fig. 10a–e) and 50 years (far future; Fig. 3a–e) scenarios. For the near-future scenario (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 8), 6,188 (0.17%) buildings in Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai fall into the medium hazard category, whereas the rest of the buildings, including those in Bengaluru and Kolkata, are categorized as low hazard.

a–e, Total angular distortion (βtot) projected for the next 50 years in Delhi (a), Mumbai (b), Bengaluru (c), Chennai (d) and Kolkata (e). f, Count of buildings per each hazard category (low to very high) for a 50-year scenario, per megacity. The inset bar chart represents the number of buildings in each megacity with no data. Maps in a–e generated using MATLAB R2023a and QGIS 3.34. Credit: basemaps in a–e, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

For the intermediate-future scenario (Supplementary Fig. 10a–e and Supplementary Table 8), 4,804,360 (97.3%), 41,349 (0.84%) and 4,116 (0.083%) of Delhi’s buildings fall into the low-, medium- and high-hazard categories, respectively. The corresponding values for Mumbai are 1,991,849 (93.2%), 20,106 (0.94%) and 353 (0.016%). Additionally, approximately 5,751 (0.36%) and 7,843 (0.31%) are characterized as medium hazards in Bengaluru and Kolkata, respectively. Furthermore, 72,947 (3.3%) and 1,720 (0.079%) of Chennai are located within the medium- and high-hazard zones, respectively.

For the far-future scenario (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 8), the low-hazard zone encompasses 4,768,420 (96.5%), 63,913 (91.34%), 1,554,336 (97.6%), 1,959,415 (90.9%) and 2,352,852 (95.8%) buildings in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata, respectively. Chennai includes the largest number of buildings 177,347 (8.2%) exposed to moderate hazards. The high hazard affects 15,530 (0.72 %) in Chennai, 17,492 (0.35%) in Delhi, 4,172 (0.19%) in Mumbai, 263 (0.011%) in Kolkata and 221 (0.014%) in Bengaluru.

Subsidence-related building damage risk

We further assess the subsidence-related building damage risk for the above hazard scenarios by considering building densities obtained from the Google Open Buildings (v3) dataset for the five Indian megacities (see Methods for details). We found that during the observation period (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12 and Supplementary Table 9), in Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai, 2,264, 110 and 32 buildings, respectively, are categorized as under high damage risk. All other megacities collectively have 100% of their buildings in the very low, low and medium risk categories.

For the near-future scenario (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14 and Supplementary Table 9), 2.1 million, 1.28 million, 0.88 million, 0.67 million and 0.48 million buildings in Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bengaluru and Mumbai, respectively, have medium damage risk. Also, 3,169, 958 and 262 buildings are exposed to a high risk in Delhi, Chennai and Mumbai, respectively.

For the intermediate-future scenario (Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16 and Supplementary Table 9), we estimated that 24,582, 14,249, 2,577, 40,843 and 4,052 buildings are exposed to high damage risk in these cities, respectively, and 3,169, 255 and 958 buildings in Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai are in the very-high-risk category.

For the far-future scenario (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 9), less than 4.6% and 1% of the total area of each megacity experiences high and very high risk levels. We estimated that 11,457, 3,477, 112, 8,284 and 199 buildings are within the very-high-damage-risk zone in Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Chennai, respectively. Also, in Chennai, 97,946 buildings are exposed to high damage risk, and the corresponding values for Delhi and Kolkata are 38,428 and 30,344, respectively.

a–e, Risk of subsidence-induced building structural damage projected for the next 50 years in Delhi (a), Mumbai (b), Bengaluru (c), Chennai (d) and Kolkata (e). f–j, Percentage of buildings in each risk category for Delhi (f), Mumbai (g), Bengaluru (h), Chennai (i) and Kolkata (j). The middle of each donut chart displays the number of buildings in each risk category. Maps in a–e generated using MATLAB R2023a and QGIS 3.34. Credit: basemaps in a–e, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

Discussion

This study quantifies the land subsidence rate and potential building damage risk due to differential land subsidence in five Indian megacities: Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata. The spatially semicontinuous VLM rate maps show a heterogeneous pattern of land surface sinking and rising (Fig. 2) caused by various factors. These findings offer a basis for future investigation into the specific causes of subsidence, particularly through quantitative attribution of its drivers.

We estimate that 2,264, 110 and 32 buildings in Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai are currently at high damage risk due to differential land subsidence (Supplementary Table 9). Projection of VLM rates and building structural damage risk is essential for anticipating vulnerable structures47. Our analysis suggests that in 30 years, an estimated 3,169, 958 and 255 buildings in Delhi, Chennai and Mumbai will face a very high risk of damage. Furthermore, in 50 years, 11,457, 3,477, 112, 8,284 and 199 buildings in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Chennai and Kolkata are expected to be at very high risk of damage (Supplementary Table 9). These results reveal that Chennai is characterized by a large number of buildings exposed to high and very high structural damage risk, surpassing Delhi and Mumbai in the far-future projections (Supplementary Table 9).

The provided risk maps should be interpreted with caution. A designation of high or very high risk of building damage does not imply imminent structural failure. Instead, it indicates that differential subsidence in these areas substantially increases vulnerability, potentially amplifying the impacts of other hazards such as flooding, storms or inadequate construction practices, thereby elevating the likelihood of structural failure. Thus, a factor to consider is the compounding effect of other hazards, such as floods, hurricanes and earthquakes, whose risk can be amplified by land subsidence. For instance, differential subsidence can undermine a building’s foundation, making it more susceptible to damage during seismic events or floods. Similarly, the impact of hurricanes is magnified when structural foundations are uneven or weakened. Many cities worldwide are experiencing subsidence, highlighting the urgent need to address its potential impact on exacerbating the effects of other hazards on infrastructure27,36,48.

Furthermore, our risk analysis assumes uniform building vulnerability. The vulnerability of a building depends on several factors, including its construction age, maintenance, characteristics (geometry, floors and materials used)49 and exposure to other hazards such as floods, earthquakes and fires. Such information is often unavailable in many parts of the world50, and thus, performing a comprehensive damage risk assessment is not a trivial task.

Our analysis provides a robust first-order estimation of subsidence-induced building damage risk using angular distortion, a widely used geotechnical parameter that is empirically validated and suitable for regional-scale assessments45,51. To refine these estimates, follow-up research should consider adding subsidence-related damage parameters, such as relative rotation and deflection ratio. Also, the distortion angle hazard accumulation scenarios assume a sublinear VLM, which may vary temporally due to various natural and anthropogenic factors17, affecting the risk maps. Additionally, finer spatial resolution of subsidence data can improve the risk assessment.

An examination of data gathered from news media outlets covering building collapses from 1989 to 2023 (Fig. 1) unveils a notable pattern. Delhi and Mumbai have experienced relatively greater numbers of collapse events than their megacity counterparts. We cautiously suggest that differential land subsidence may affect future structural damage; to establish a robust statistical association between them, we call for creating a comprehensive building damage record that is spatially explicit, temporally resolved and standardized and that includes both damage attributes and building metadata, along with georeferenced information to align with InSAR-based subsidence measurements.

Often, the assumption prevails that differential subsidence is detectable by observing cracks in foundational walls. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that not all building cracks indicate settlement. Conversely, the absence of visible cracks does not definitively rule out the occurrence of settlement52. Navigating this complexity makes it challenging to identify structurally damaged buildings based on conventional techniques and instruments on a large scale, presenting a formidable obstacle for asset managers and policymakers to take preventive actions45. In addition, during the planning stages of new infrastructure projects, such as building construction, geotechnical engineers often lack immediate access to information on differential settlement. This absence of readily available settlement information can cause delays in initiating the projects, as engineers must await the results of labour-intensive geodetic surveys, which can take several months to a year to complete53.

On the other hand, the remote sensing-based InSAR technique applied here offers precise and accurate estimation of VLM for a large spatial extent and at high resolution, which is not currently included in any constructional frameworks. We suggest that this technique will be valuable for monitoring the settlement of construction assets. It can be engaged during any phase of a construction project, including preconstruction, construction, postconstruction and maintenance phases, in addition to other conventional methods53. This could make the InSAR technique a pivotal tool for settlement monitoring and structural damage risk assessment for buildings, which may be integrated into the current construction framework46,47.

We conclude that current and future infrastructure damage risk can be exacerbated through the compounding effect of multiple factors, including climate change, land subsidence and human activities (Fig. 5). Weather extremes directly influence infrastructure vulnerabilities54, and as they become more frequent and intense in the face of climate change55, their toll is increasing, too. Thus, the compounding effect of land subsidence, climate change and weather extremes forms a complex and critical nexus that can exacerbate the risk of structural damage. Climate models project that in the future, wet years will become wetter and dry years drier; thus, the frequency and intensity of floods and droughts will increase56, indicating occasional shortages of surface water and likely increased reliance on groundwater resources. Removal of water from underground results in reduced pore pressure and the closure of pore spaces, manifesting in land subsidence above the aquifer. In particular, alluvial deposits from the Holocene, found along flood plains where human settlement has been growing due to the availability of fresh water and fertile land57, are subject to land subsidence associated with fluid extraction and sediment compaction. In addition, increasing global energy demand is expected to further drive the extraction of oil, gas and coal, potentially intensifying land subsidence in resource-rich regions28. Thus, climate change and human actions can accelerate subsidence rates in places lacking adequate adaptation and mitigation strategies.

This figure showcases the relationship between natural and anthropogenic factors contributing to land subsidence, such as groundwater pumping, oil/gas extraction, urbanization, drought, increasing population and land use changes, alongside their direct impact on the structural integrity of buildings. Top: use of SAR sensors aboard satellites to conduct large-scale monitoring of urban areas, enabling the detection of differential subsidence effects across major cities around the world. This monitoring is crucial in assessing the risks to and planning for the maintenance of essential infrastructure in response to both gradual and sudden deformations driven by environmental and human activities. Map data in 3D visualization from OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright).

To reduce risks and improve building codes, materials and oversight, we propose a holistic preventative approach to infrastructure management comprising research, mitigation, adaptation and technology implementation. A better understanding of potential threats to infrastructure is pivotal to developing innovative solutions addressing emerging challenges. These solutions should be tailored to the individual needs of communities and account for local socioeconomic conditions. Furthermore, urban planners should consider developing land subsidence-resilient infrastructure, given that development in subsidence-prone areas is unavoidable. Resources are limited and often vary from one community to another, so a preventative approach should leverage Big Earth observation datasets, such as those presented here, to ensure fair, equitable and sustainable access to datasets. Finally, land subsidence mitigation and adaptation strategies should be implemented, which include new regulations to reduce groundwater extraction, surface water management, groundwater recharge, revegetation and soil conservation58. Using this holistic preventative approach, societies can better protect their infrastructure and ensure the safety and well-being of their inhabitants. Such an integrated approach is crucial for current urban management and future research directions aimed at safeguarding against the compounded risks of subsidence, climate change and human activities.

Methods

InSAR data processing

In total, we used 1,299 Sentinel-1 A/B interferometric wide SAR images from 15 Sentinel-1 frames to measure Earth surface deformation in a line-of-sight (LOS) direction for Indian megacities using multitemporal interferometric SAR analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Based on the availability of Sentinel-1 images, the InSAR analysis period for the selected megacities varied. For Delhi and Mumbai, the InSAR data processing covered SAR images acquired from 2015 to 2023, and for Kolkata, the processed images were from 2017 to 2023. In the case of Chennai, the images spanned from 2015 to 2020, whereas for Bengaluru, images from 2019 to 2023 were used. Chennai, Bengaluru and Mumbai have images only from descending flight orbit directions, whereas Delhi and Kolkata have data from both ascending and descending flight orbits. We generated 5,472 interferograms from both ascending and descending orbit images. We used a temporal baseline of 400 days and a perpendicular baseline of 150 m. We multilooked the images with the original pixel spacing of 2.3 m × 14.1 m by a factor of 32 × 6 times in the range and azimuth direction, respectively, resulting in a 73.6 m × 85 m (~75 m) pixel resolution of subsequent deformation data.

We generated high-resolution spatiotemporal LOS deformation data using the wavelet-based InSAR (WabInSAR) algorithm59,60,61 (Supplementary Fig. 17). In our data processing, the WabInSAR algorithm aided in extracting the deformation phase component from the wrapped complex interferometric phase, which contains other phase components (orbital phase, topographic phase, atmospheric phase and other nuisance phase components) that necessitate removal59. Initially, the geometrical and topographic phases were computed and eliminated from the wrapped interferograms utilizing the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model, which has a spatial resolution of ~30 m (ref. 60). Then, to identify the elite pixels that are correlated temporally apart from the noisy ones, the time series of the wrapped interferometric phase is analysed statistically in the wavelet domain59. After this, an iterative two-dimensional sparse phase unwrapping algorithm was applied to unwrap the wrapped interferograms and calculate the phase estimate for each chosen elite pixel in space and time59. Atmospheric error correction was performed following ref. 60, by first identifying interferogram pairs affected by minimal decorrelation errors using the minimum spanning tree algorithm60. The selected pairs, characterized by minimal temporal and perpendicular baselines, were used to estimate spatially correlated atmospheric signals. A 5 km ×5 km patch-wise two-dimensional smoothing spline was then applied to each minimum spanning tree pair to estimate the delay, which was then subtracted from all other pairs. The corrected phase time series was subsequently low-pass filtered in time using wavelet coefficient thresholding59 to further remove temporally uncorrelated components of the delay. Additionally, potential long-wavelength ionospheric artifacts were identified and removed60. After that, we eliminated the orbital error caused by the imprecise position of the satellite, which further improved the accuracy of the estimated deformation phase61. To remove the orbital error, we applied precise orbit ephemerides files provided by the European Space Agency. A robust regression along with a continuous wavelet transform was utilized to invert the phase deviations from unwrapped interferograms and to diminish the temporal nuisance phase component contributed by atmospheric delay61. Finally, utilizing reweighted least squares, we computed the LOS deformation velocities for each elite pixel by fitting an optimal line to the associated deformation time series in relation to the reference points. The coordinate information of the reference points selected for each Indian megacity to calculate the LOS velocities in the outskirts of city boundaries is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

The derived LOS velocities encompass deformation in three directions: two horizontal components (north–south and east–west) and one vertical component (up–down). Due to the right-looking setup and near-polar orbit of the Sentinel-1 satellites, observations occurring along the north–south direction are insensitive and negligible. Subsequently, for Indian megacities Delhi and Kolkata, we merged the resulting LOS velocities from ascending and descending flight orbits to obtain east–west (E) and up–down (U) velocities47. The process for obtaining high-resolution E and U velocity maps included detecting pixels of LOS velocities from ascending and descending orbits that were closely located and merging them using equation (1):

where ASCLOS and DESLOS represent extracted LOS velocities from ascending and descending flight orbits, respectively. C denotes the unit vector62, which is calculated with the help of incidence and heading angles. Consequently, equation (1) is substituted in equation (2) to generate high-resolution E and U velocity maps:

where T is defined as transpose. In the case of Chennai, Mumbai and Bengaluru, with LOS velocities from only one SAR viewing geometry (descending orbit) of Sentinel-1, we assumed east–west motion to be negligible and projected our extracted LOS velocities onto the vertical direction with the help of equation (3)

where θ denotes the local incidence angle that is estimated for each selected elite pixel.

The resultant vertical velocities of Indian megacities in local reference frames are tied to the IGS14 reference frame based on the available Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) station measurements for converting local velocities to a global reference frame. The final vertical velocities of Indian megacities63 are shown in Fig. 2 and the standard deviation in Supplementary Fig. 18. The VLM rates are validated against available GNSS observations. The absolute difference between the vertical rate of GNSS station and median value of nearby pixels within an ~150 m distance is 0.68 mm yr−1 at the Bengaluru dataset (Supplementary Fig. 19). The cross-correlation of LOS rates for corresponding pixels within ascending and descending tracks64 yields Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.88 for Delhi and 0.81 for Kolkata, suggesting that LOS displacements are mainly dominated by vertical motions (Supplementary Fig. 19c,d) and that the presence of secondary horizontal displacements derived the observed differences.

Assessment of total angular distortion

In the domain of geotechnical practices, a comprehensive body of research since the 1950s has unequivocally established that the magnitude of structural damage resulting from foundational movements induced by subsidence is intricately linked to the intensity of factors such as differential settlement and angular distortion19,21,44,52,65,66,67,68. Following those foundational studies, contemporary researchers have leveraged the capabilities of the InSAR technique for a comprehensive assessment of the large-scale damage incurred by buildings due to the sinking of the ground in large cities14,45,46,47,49,69,70. In the context of building foundation design, the term ‘settlement’ refers to the vertical displacement of the foundation52. Given that structural damage to buildings is frequently associated with variations in settlement across different locations within a structure, the focus is often placed on differential settlement rather than absolute settlement52. In turn, the differential settlement gives rise to angular distortion, identified as a hazard to the structural integrity of buildings, stemming from strain alterations between two adjacent points in a structure’s foundation19,44,47,52,70.

Expressed in terms of l, representing the longest length of buildings, and Δδ, denoting the differential settlement of buildings, the formulation for generating angular distortion is given by equation (4)

We calculated Δδ for the InSAR period for each building polygon by interpolating the VLM rates to building polygon vertices, rather than using a set grid. To our knowledge, this building-specific approach has not been applied in previous studies and extends the grid-based approach, such as that used in ref. 71. Further, we calculated and used the longest length l of each building footprint in this study. This way, we estimated β at the building scale for ~13.27 million buildings in Indian megacities, based on the Google Open Buildings (v3) dataset (see ‘Building structural damage risk assessment’).

Because the calculated β is representative of a single year, we multiplied the estimated β with the respective InSAR period to calculate the total angular distortion βtot over the InSAR period. Nevertheless, it is crucial to emphasize that the calculated βtot for the InSAR period reflects partial distortion and does not encapsulate the entirety of the distortion that happened over the buildings’ entire lifespan46,47. Based on existing literature19,45,46,47, we categorized hazard severity into four classes denoting increasing levels of building structural damage: low (0 > βtot < 0.0006 rad), medium (0.0006 rad ≥ βtot < 0.002 rad), high (0.002 rad ≥ βtot < 0.008 rad) and very high (βtot ≥ 0.008 rad). Based on actual evidence, a set of dimensionless angular distortion values was proposed by previous research19,67 that is widely accepted as the critical index of settlement, defining the threshold of minimal to extremely severe damage to buildings. Refs. 19,67 are among the foundational studies on this subject, which have utilized evidence-based data over the years to provide the established values that have been further investigated and accepted by supplementary studies21,65. Even within the permissible settlement criteria outlined by the 1955 USSR building code, which was established through 25 years of empirical observation, a β value exceeding 1/500 (0.002 rad) was reported as the uppermost threshold indicative of moderate to severe structural damage52,67. Reference 20 discusses that settlement exceeding 1/120 (0.008 rad) can associate severe damage from analysing thousands of damaged homes in California.

Further, to investigate potential future scenarios of structural damage from subsidence in Indian megacities, we delve into three distinct projection timeframes: a 10-year near-future period, a 30-year intermediate-future period and a 50-year far-future period. These analyses extend beyond the historical records from InSAR observations, assuming a continuous and linear subsidence rate throughout the latter part of the twenty-first century17. Adopting a linear model is a common practice in investigating future hazards13, as observed in scenarios such as those arising from relative sea-level rise based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Amendment report72.

Building structural damage risk assessment

The risk of building damage due to differential subsidence is a function of several factors defined as

where F is a deterministic or stochastic function, βtot is the total distortion angle, V is the vulnerability of the building (for example, structural sensitivity to uneven ground motion), and E is exposure (for example, building density in the affected area). For assessing buildings that are exposed to different severities of structural damage owing to βtot in different hypothesized scenarios, we obtained the polygon-based footprint data of buildings for Indian megacities from the Google Open Buildings (v3) dataset, which encompasses more than 1.8 billion building footprints73. The extracted data contain more than ~13.27 million building footprints located in the five Indian megacities (Supplementary Fig. 20). Using such a widely recognized and high-resolution building footprint dataset aids in precisely identifying the structures that are affected by angular distortion on a large regional scale. Unfortunately, data on the vulnerability of buildings to differential subsidence are not available, and thus, we assume a uniform vulnerability for all buildings. For the exposure analysis, we resampled the building footprint data to a 0.2 km × 0.2 km grid based on the building density categorization followed by ref. 46. We categorized building footprint density into three classes47: low (building count ranging from 0 to fewer than 2,000), moderate (between 2,000 and 5,000) and high (exceeding 5,000; Supplementary Fig. 21). Based on the generated per-building βtot for different scenarios and building density classifications, we generated the risk map for specific building structural damage, ranging from very low to very high categories based on a three-dimensional risk matrix14,47,51 (Supplementary Fig. 22). Although the risk is assigned at the building level, this method captures element of collective risk by accounting for the potential amplification of structural impacts in densely built environments, under the assumption of uniform vulnerability. In such contexts, a low individual hazard may still contribute to a high overall risk when many buildings are clustered together. Consequently, assessing risk through this combined lens is important for informing urban planning and disaster-mitigation strategies, which are often designed to reduce societal-level losses rather than only individual damage.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are deposited in the University Libraries, Virginia Tech database. The datasets can be accessed using this link: https://doi.org/10.7294/25856260.v2 (ref. 63). The Sentinel-1 data used in this study are accessible from the Alaska Satellite Facility (https://search.asf.alaska.edu/#/). The population dataset is available from https://hub.worldpop.org/geodata/listing?id=78. The groundwater data can be accessed from the India Water Resources Infromation System (https://indiawris.gov.in/wris/#/). The GRACE/GRACE-FO data (RL06 Level 3 product of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory) are accessible from Earthdata Login (https://urs.earthdata.nasa.gov/). The Google Buildings dataset can be obtained from https://sites.research.google/gr/open-buildings/.

Code availability

The WabInSAR algorithm (v5.6) used in this study can be openly accessed using this link: https://www.eoivt.com/software.

References

Keim, M. When buildings collapse. DisasterDoc https://web.archive.org/web/20230921164425/https://disasterdoc.org/when-buildings-collapse/ (2021).

Bagri, N. T. & Harris, G. Scores feared trapped in collapse of Mumbai building. The New York Times (27 September 2013).

Kabir, H., Maple, M., Islam, M. S. & Usher, K. The current health and wellbeing of the survivors of the Rana Plaza building collapse in Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 2342 (2019).

Okunola, O. H. Survival of the fittest: assessing incidents of building collapse and reduction practices in Lagos, Nigeria. Environ. Qual. Manag. 31, 141–150 (2022).

Kidwai, N. 12 dead in Karnataka building collapse, 10 still feared trapped 3 days on. NDTV.com https://www.ndtv.com/karnataka-news/12-dead-in-karnatakas-dharwad-building-collapse-10-still-feared-trapped-3-days-on-2010993 (2019).

Awe, O. O., Atofarati, E. O., Adeyinka, M. O., Musa, A. P. & Onasanya, E. O. Assessing the factors affecting building construction collapse casualty using machine learning techniques: a case of Lagos, Nigeria. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 24, 261–269 (2024).

Burland, J. B., Broms, B. B. & De Mello, V. F. B. Behaviour of foundations and structures. In Proc. 9th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering (1978).

Caredda, G. et al. Learning from the progressive collapse of buildings. Dev. Built Environ. 15, 100194 (2023).

Seeley, I. H. Building Maintenance (Bloomsbury, 1987).

Son, M. & Cording, E. J. Estimation of building damage due to excavation-induced ground movements. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 131, 162–177 (2005).

Burland, J., Burbidge, M. & Wilson, E. Settlement of foundations on sand and gravel. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 78, 1325–1381 (1985).

Pistrika, A. K. & Jonkman, S. N. Damage to residential buildings due to flooding of New Orleans after hurricane Katrina. Nat. Hazards 54, 413–434 (2010).

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C. & Kirwan, M. L. Hidden vulnerability of US Atlantic coast to sea-level rise due to vertical land motion. Nat. Commun. 14, 2038 (2023).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Urban growth and land subsidence: multi-decadal investigation using human settlement data and satellite InSAR in Morelia, Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 811, 152211 (2022).

Vassileva, M. et al. A decade-long silent ground subsidence hazard culminating in a metropolitan disaster in Maceió, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 11, 7704 (2021).

Chourasia, A. et al. Damage assessment of buildings due to land subsidence in Joshimath town of Northwestern Himalaya, India. Nat. Hazards 120, 11433–11450 (2024).

Shirzaei, M. et al. Measuring, modelling and projecting coastal land subsidence. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 40–58 (2020).

Verberne, M., Koster, K. & Fokker, P. A. Multi-data settlement prediction along a road section integrating InSAR and coastal subsurface information with data assimilation. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1323874 (2024).

Skempton, A. W. & Macdonald, D. H. The allowable settlements of buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. 5, 727–768 (1956).

Meehan, R. L. & Karp, L. B. California housing damage related to expansive soils. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 8, 139–157 (1994).

Grant, R., Christian, J. T. & Vanmarcke, E. H. Differential settlement of buildings. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 100, 973–991 (1974).

Miano, A., Mele, A. & Prota, A. Fragility curves for different classes of existing RC buildings under ground differential settlements. Eng. Struct. 257, 114077 (2022).

Nadal, N. C., Zapata, R. E., Pagán, I., López, R. & Agudelo, J. Building damage due to riverine and coastal floods. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 136, 327–336 (2010).

Huning, L. S. et al. Global land subsidence: impact of climate extremes and human activities. Rev. Geophys. 62, e2023RG000817 (2024).

Scanlon, B. R. et al. Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 87–101 (2023).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667 (2021).

Herrera-García, G. et al. Mapping the global threat of land subsidence. Science 371, 34–36 (2021).

Candela, T. & Koster, K. The many faces of anthropogenic subsidence. Science 376, 1381–1382 (2022).

India will have 7 mega cities by 2030. World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/india-megacities-by-2030-united-nations/ (2016).

World population prospects 2024. United Nations https://population.un.org/wpp/ (2024).

Maharana, P., Agnihotri, R. & Dimri, A. P. Changing Indian monsoon rainfall patterns under the recent warming period 2001–2018. Clim. Dyn. 57, 2581–2593 (2021).

Jasechko, S. et al. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 625, 715–721 (2024).

Landerer, F. W. & Swenson, S. C. Accuracy of scaled GRACE terrestrial water storage estimates. Water Resour. Res. 48, W04531 (2012).

Güntner, A. et al. A global analysis of temporal and spatial variations in continental water storage. Water Resour. Res. 43, W05416 (2007).

Panda, D. K. & Wahr, J. Spatiotemporal evolution of water storage changes in India from the updated GRACE-derived gravity records. Water Resour. Res. 52, 135–149 (2016).

Wu, P.-C., Wei, M. M. & D’Hondt, S. Subsidence in coastal cities throughout the world observed by InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098477 (2022).

Garg, S., Motagh, M., Indu, J. & Karanam, V. Tracking hidden crisis in India’s capital from space: implications of unsustainable groundwater use. Sci. Rep. 12, 651 (2022).

Kumar, H., Syed, T. H., Amelung, F., Agrawal, R. & Venkatesh, A. S. Space-time evolution of land subsidence in the National Capital Region of India using ALOS-1 and Sentinel-1 SAR data: evidence for groundwater overexploitation. J. Hydrol. 605, 127329 (2022).

Shastri, A. et al. Two decades of land subsidence in Kolkata, India revealed by InSAR and GPS measurements: implications for groundwater management and seismic hazard assessment. Nat. Hazards 118, 2593–2607 (2023).

Bansal, S., Biswas, S. & Singh, S. K. Holistic assessment of existing buildings: Indian context. J. Build. Eng. 25, 100793 (2019).

Chatterjee, R. S. et al. Unravelling the dynamics and causes of land subsidence in the National Capital Territory of Delhi, India, by spaceborne and in situ observations. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82, 413 (2023).

Kumar, H. et al. InSAR reveals recovery of stressed aquifer systems in parts of Delhi, India: evidence for improved groundwater management. Water Resour. Res. 61, e2024WR037704 (2025).

Tiwari, D. K. et al. Delhi urbanization footprint and its effect on the earth’s subsurface state-of-stress through decadal seismicity modulation. Sci. Rep. 13, 11750 (2023).

Burland, J. B. & Wroth, C. P. Settlement of buildings and associated damage (1975).

Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M. & Barnard, P. L. Slowly but surely: exposure of communities and infrastructure to subsidence on the US east coast. PNAS Nexus 3, pgad426 (2024).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Present-day land subsidence rates, surface faulting hazard and risk in Mexico City with 2014–2020 Sentinel-1 IW InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 253, 112161 (2021).

Ohenhen, L. O. & Shirzaei, M. Land subsidence hazard and building collapse risk in the coastal city of Lagos, West Africa. Earths Future 10, e2022EF003219 (2022).

Ao, Z. et al. A national-scale assessment of land subsidence in China’s major cities. Science 384, 301–306 (2024).

Peduto, D., Nicodemo, G., Maccabiani, J. & Ferlisi, S. Multi-scale analysis of settlement-induced building damage using damage surveys and DInSAR data: a case study in The Netherlands. Eng. Geol. 218, 117–133 (2017).

Rosser, J. F. et al. Predicting residential building age from map data. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 73, 56–67 (2019).

Haghshenas Haghighi, M. & Motagh, M. Uncovering the impacts of depleting aquifers: a remote sensing analysis of land subsidence in Iran. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk3039 (2024).

Wahls, H. E. Tolerable settlement of buildings. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 107, 1489–1504 (1981).

Reinders, K. J., Giardina, G., Zurfluh, F., Ryser, J. & Hanssen, R. F. Proving compliance of satellite InSAR technology with geotechnical design codes. Transp. Geotech. 33, 100722 (2022).

Shortridge, J. & Camp, J. S. Addressing climate change as an emerging risk to infrastructure systems. Risk Anal. 39, 959–967 (2019).

AghaKouchak, A. et al. Climate extremes and compound hazards in a warming world. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 48, 519–548 (2020).

Stevenson, S. et al. Twenty-first century hydroclimate: a continually changing baseline, with more frequent extremes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2108124119 (2022).

Rentschler, J. et al. Global evidence of rapid urban growth in flood zones since 1985. Nature 622, 87–92 (2023).

Alam, S., Gebremichael, M., Li, R., Dozier, J. & Lettenmaier, D. P. Can managed aquifer recharge mitigate the groundwater overdraft in California’s central valley? Water Resour. Res. 56, e2020WR027244 (2020).

Shirzaei, M. A wavelet-based multitemporal DInSAR algorithm for monitoring ground surface motion. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 10, 456–460 (2013).

Lee, J.-C. & Shirzaei, M. Novel algorithms for pair and pixel selection and atmospheric error correction in multitemporal InSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 286, 113447 (2023).

Shirzaei, M. & Bürgmann, R. Topography correlated atmospheric delay correction in radar interferometry using wavelet transforms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L01305 (2012).

Hanssen, R. F. Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis (Springer, 2001).

Sadhashivam, N., Ohenhen, L., Khorrami, M., Werth, S. & Shirzaei, M. Data for vertical land motion and building damage risk for the Indian megacities. University Libraries, Virginia Tech https://doi.org/10.7294/25856260.v2 (2024).

Wang, G., Li, P., Li, Z., Liang, C. & Wang, H. Coastal subsidence detection and characterization caused by brine mining over the Yellow River Delta using time series InSAR and PCA. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 114, 103077 (2022).

Bjerrum, L. Allowable settlement of structures. In Proc. 3rd European Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering Vol. 2, 135–137 (1963).

Boscardin, M. D. & Cording, E. J. Building response to excavation-induced settlement. J. Geotech. Eng. 115, 1–21 (1989).

Polshin, D. E. & Tokar, R. A. Maximum allowable non-uniform settlement of structures. In Proc. 4th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering Vol. 1, 402–405 (Butterworths Scientific Publications, 1957).

Zhou, S., Di, H., Xiao, J. & Wang, P. Differential settlement and induced structural damage in a cut-and-cover subway tunnel in a soft deposit. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 30, 04016028 (2016).

Ma, P., Zheng, Y., Zhang, Z., Wu, Z. & Yu, C. Building risk monitoring and prediction using integrated multi-temporal InSAR and numerical modeling techniques. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 114, 103076 (2022).

Cigna, F. & Tapete, D. Satellite InSAR survey of structurally-controlled land subsidence due to groundwater exploitation in the Aguascalientes Valley, Mexico. Remote Sens. Environ. 254, 112254 (2021).

Ohenhen, L. O. et al. Land subsidence risk to infrastructure in US metropolises. Nat. Cities 2, 543–554 (2025).

IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

Sirko, W. et al. Continental-scale building detection from high resolution satellite imagery. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2107.12283 (2021).

Population counts. WorldPop https://hub.worldpop.org/project/categories?id=3 (2025).

Acknowledgements

N.S. and S.W. were partly supported by NASA grant nos 80NSSC21K0061 and 80NSSC24K0176. L.O., M.K. and M.S. were partly supported by a grant from DoD. We express our gratitude to the Copernicus Programme of the European Space Agency for providing open access to Sentinel-1 data. Additionally, we extend our thanks to Google Research for making the Open Buildings dataset freely available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.S., L.O., S.W. and M.S. designed the study. N.S. conceived the study with input from L.O., S.W. and M.S. N.S., L.O. and M.K. performed the analysis. N.S. created the figures. N.S. wrote the first draft of the paper with contributions from S.W. and M.S. N.S., L.O., M.K., S.W. and M.S. edited the paper. S.W. and M.S. supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Ekbal Hussain, Kay Koster and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sadhasivam, N., Ohenhen, L., Khorrami, M. et al. Building damage risk in sinking Indian megacities. Nat Sustain 8, 1467–1479 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01663-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01663-0

This article is cited by

-

Sinking Indian megacities

Nature Sustainability (2025)