Abstract

To address the enduring and deepening crisis facing fresh waters, many nations have recently set bold targets for freshwater protection. However, the lack of comprehensive databases and integrative frameworks hampers a robust evaluation of current freshwater protections and prioritization of future opportunities to meet these goals. This study provides a comprehensive assessment of river protection for the USA by reconciling the disparate array of major federal, state, tribal and private protection mechanisms into a single, multifaceted index. We report that just over one tenth of the river length of the contiguous USA and less than one fifth of rivers nationwide are currently protected at a level deemed viable. Lowland headwater streams and intermittent watercourses are consistently underprotected. Protection is also often spatially misaligned with other conservation objectives, where only a small fraction of watersheds with high biodiversity, habitat intactness and importance to drinking water supply are adequately (30% of river length) protected. Our assessment of river protection highlights the urgency to increase new and fortify existing protections for rivers in the years to come if we are to meet ambitious conservation targets, reverse the curve of biodiversity loss and ensure that healthy rivers benefit everyone.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17279334 (ref. 74). The sources of the datasets are available within the paper (and its Supplementary Information files). To make these data more accessible, we have also created an interactive, online mapping explorer that allows anyone to explore the extent of protection and identify conservation opportunities for US rivers available at https://map.myriver.americanrivers.org/.

Supplementary Information is available for this paper. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to L.C. and J.D.O.

Code availability

The code to reproduce the results and figures of this study is available via GitHub at https://github.com/liseCSP/National-Protected-Rivers-Assessment.

References

Living Planet Report 2022—Building a Nature-Positive Society (eds Almond, R.E.A. et al.) (WWF, 2022).

Ceballos, G. et al. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400253 (2015).

Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (eds Brondízio, E. S. et al.) (IPBES Secretariat, 2019).

Dinerstein, E. et al. A global deal for nature: guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw2869 (2019).

Vári, Á et al. Freshwater systems and ecosystem services: challenges and chances for cross-fertilization of disciplines. Ambio 51, 135–151 (2022).

Lynch, A. J. et al. People need freshwater biodiversity. WIREs Water 10, e1633 (2023).

Urban, M. C. Accelerating extinction risk from climate change. Science 348, 571–573 (2015).

Sayer, C. A. et al. One-quarter of freshwater fauna threatened with extinction. Nature 638, 138–145 (2025).

Gurney, G. G., Adams, V. M., Álvarez-Romero, J. G. & Claudet, J. Area-based conservation: taking stock and looking ahead. One Earth 6, 98–104 (2023).

Moberg, T. et al. Designing and Managing Protected and Conserved Areas to Support Inland Water Ecosystems and Biodiversity Report No. 8 (IUCN, 2024).

Birnie-Gauvin, K. et al. The RACE for freshwater biodiversity: essential actions to create the social context for meaningful conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e12911 (2023).

Tickner, D. et al. Bending the curve of global freshwater biodiversity loss: an emergency recovery plan. BioScience 70, 330–342 (2020).

van Rees, C. B. et al. Safeguarding freshwater life beyond 2020: recommendations for the new global biodiversity framework from the European experience. Conserv. Lett. 14, e12771 (2021).

Abell, R., Allan, J. D. & Lehner, B. Unlocking the potential of protected areas for freshwaters. Biol. Conserv. 134, 48–63 (2007).

Moravek, J. A. et al. Centering 30 × 30 conservation initiatives on freshwater ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 21, 199–206 (2023).

Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity 15/4. Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

Conserving and Restoring America the Beautiful (US Government, 2021).

A Pathway for Inland Waters in the 30×30 Target: Discussion Document (The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas and the WWF, 2022).

Moir, K., Thieme, M. & Opperman, J. Securing a Future that Flows: Case studies of Protection Mechanisms for Rivers (WWF and The Nature Conservancy, 2016).

Bastin, L. et al. Inland surface waters in protected areas globally: current coverage and 30-year trends. PLoS ONE 14, e0210496 (2019).

Opperman, J. J. et al. Safeguarding free-flowing rivers: the global extent of free-flowing rivers in protected areas. Sustainability 13, 2805 (2021).

Abell, R., Lehner, B., Thieme, M. & Linke, S. Looking beyond the fenceline: assessing protection gaps for the world’s rivers. Conserv. Lett. 10, 384–394 (2017).

Acreman, M., Hughes, K. A., Arthington, A. H., Tickner, D. & Dueñas, M. Protected areas and freshwater biodiversity: a novel systematic review distils eight lessons for effective conservation. Conserv. Lett. 13, e12684 (2020).

Leal, C. G. et al. Integrated terrestrial-freshwater planning doubles conservation of tropical aquatic species. Science 370, 117–121 (2020).

Lawrence, D. J. et al. National parks as protected areas for U.S. freshwater fish diversity: national parks as freshwater protected areas. Conserv. Lett. 4, 364–371 (2011).

Higgins, J. et al. Durable freshwater protection: a framework for establishing and maintaining long-term protection for freshwater ecosystems and the values they sustain. Sustainability 13, 1950 (2021).

Pringle, C. M. Hydrologic connectivity and the management of biological reserves: a global perspective. Ecol. Appl. 11, 981–998 (2001).

Juffe-Bignoli, D. et al. Achieving Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 to improve the performance of protected areas and conserve freshwater biodiversity. Aquat. Conserv. 26, 133–151 (2016).

Harrison, I. J. et al. Protected areas and freshwater provisioning: a global assessment of freshwater provision, threats and management strategies to support human water security. Aquat. Conserv. 26, 103–120 (2016).

Flitcroft, R. L., Abell, R., Harrison, I., Arismendi, I. & Penaluna, B. E. Making global targets local for freshwater protection. Nat. Sustain. 6, 1499–1502 (2023).

Perry, D. [Re] framing the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act for ecosystem based resilience and adaptation. J. Wilderness Med. 23, 41–48 (2017).

Graziano, M. P., Deguire, A. K. & Surasinghe, T. D. Riparian buffers as a critical landscape feature: insights for riverscape conservation and policy renovations. Diversity 14, 172 (2022).

Perry, D., Harrison, I., Fernandes, S., Burnham, S. & Nichols, A. Global analysis of durable policies for free-flowing river protections. Sustainability 13, 2347 (2021).

Dietz, M. S., Belote, R. T. & Aplet, G. H. Mind the GAP—but make it better: improving the U.S. Gap Analysis Project’s protected-area classification system to better reflect biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e12901 (2023).

Dreiss, L. M. & Malcom, J. W. Identifying key federal, state, and private lands strategies for achieving 30 × 30 in the United States. Conserv. Lett. 15, e12849 (2022).

Bennett Wilkinson, J. The state role in biodiversity conservation. Issues Sci. Technol. 15, 71–77 (1999).

Comte, L., Olden, J. D., Lischka, S. & Dickson, B. G. Multi-scale threat assessment of riverine ecosystems in the Colorado River Basin. Ecol. Indic. 138, 108840 (2022).

Creed, I. F. et al. Enhancing protection for vulnerable waters. Nat. Geosci. 10, 809–815 (2017).

Eklund, J. & Cabeza, M. Quality of governance and effectiveness of protected areas: crucial concepts for conservation planning. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1399, 27–41 (2017).

Morgan, M. C. Water law in the 1990s shifting roles and modern concerns. Nat. Resour. Environ. 5, 20–33 (1991).

Major, J., Perry, D., Aslan, C. & McManamay, R. Identifying gaps in protected areas to expand integrated riverine ecosystem conservation. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 3, e470 (2021).

Joppa, L. N. & Pfaff, A. High and far: biases in the location of protected areas. PLoS ONE 4, e8273 (2009).

Jenkins, C. N., Van Houtan, K. S., Pimm, S. L. & Sexton, J. O. US protected lands mismatch biodiversity priorities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5081–5086 (2015).

Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data (Congressional Research Service, 2020); https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R42346

Cohen, J. E. & Small, C. Hypsographic demography: the distribution of human population by altitude. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14009–14014 (1998).

Brinkerhoff, C. B., Gleason, C. J., Kotchen, M. J., Kysar, D. A. & Raymond, P. A. Ephemeral stream water contributions to United States drainage networks. Science 384, 1476–1482 (2024).

Datry, T., Larned, S. T. & Tockner, K. Intermittent rivers: a challenge for freshwater ecology. BioScience 64, 229–235 (2014).

Hamilton, H., Rapacciuolo, G., Kanter, J., Jones-Farrand, D. T. & Young, B. E. A landscape conservation perspective of state species of greatest conservation need. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 6, e13223 (2024).

Saura, S. et al. Protected area connectivity: shortfalls in global targets and country-level priorities. Biol. Conserv. 219, 53–67 (2018).

Perry, D. et al. Resilient riverine social–ecological systems: a new paradigm to meet global conservation targets. WIREs Water 11, e1753 (2024).

Sulliván, S. M. P. et al. Waterbody connectivity: linking science and policy for improved waterbody protection. BioScience 75, 68–91 (2025).

Piczak, M. L. et al. Protecting and restoring habitats to benefit freshwater biodiversity. Environ. Rev. 32, 438–456 (2024).

Chapman, M., Boettiger, C. & Brashares, J. S. Leveraging private lands to meet 2030 biodiversity targets in the United States. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e12897 (2023).

Talty, M. J., Mott Lacroix, K., Aplet, G. H. & Belote, R. T. Conservation value of national forest roadless areas. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2, e288 (2020).

Walls, M., Lee, P. & Ashenfarb, M. National monuments and economic growth in the American West. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay8523 (2020).

Gap Analysis Project (GAP), Protected Areas Database of the United States (PAD-US) 3.0: U.S. Geological Survey Data Release (US Geological Survey, 2023).

National Conservation Easement Database (Ducks Unlimited and The Trust for Public Land, 2023); https://www.conservationeasement.us/

USGS National Hydrography Dataset v2.1 (NHD) for Hydrologic Unit (HU) 4 (US Geological Survey, 2019).

USGS National Hydrography Dataset Best Resolution (NHD) – Alaska (US Geological Survey, 2023).

Rodrigues, A. S. L. & Cazalis, V. The multifaceted challenge of evaluating protected area effectiveness. Nat. Commun. 11, 5147 (2020).

Guidance on Using the Indicators of the Monitoring Framework of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (CBD/SBSTTA/26/INF/14) (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024); https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/92cf/b458/18519b4c0b487bf9bfc23988/sbstta-26-inf-14-en.pdf

Pellissier, L. et al. Species distribution models reveal apparent competitive and facilitative effects of a dominant species on the distribution of tundra plants. Ecography 33, 1004–1014 (2010).

Abell, R. et al. Freshwater Ecoregions of North America (Island Press, 2000).

McManamay, R. A. & DeRolph, C. R. A stream classification system for the conterminous United States. Sci. Data 6, 190017 (2019).

McManamay, R. A., George, R., Morrison, R. R. & Ruddell, B. L. Mapping hydrologic alteration and ecological consequences in stream reaches of the conterminous United States. Sci. Data 9, 450 (2022).

Theobald, D. M. et al. Data for detailed temporal mapping of global human modification from 1990 to 2017. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3963012 (2023).

Theobald, D. M. et al. Earth transformed: detailed mapping of global human modification from 1990 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1953–1972 (2020).

Knox, R., Morrison, R. & Wohl, E. CONUS floodplain areas. HydroShare https://doi.org/10.4211/hs.15c4ab0ebfe7447298b18af37caf4e0e (2022).

National Levee Database (US Army Corps of Engineers, 2024).

Knox, R. L., Morrison, R. R. & Wohl, E. E. Identification of artificial levees in the contiguous United States. Water Resour. Res. 58, e2021WR031308 (2022).

Theobald, D. M. A general model to quantify ecological integrity for landscape assessments and US application. Landsc. Ecol. 28, 1859–1874 (2013).

The Map of Biodiversity Importance (NatureServe Network data release, 2024); https://www.natureserve.org/map-biodiversity-importance

Mack, E., Lilja, R., Claggett, S., Sun, G. & Caldwell, P. Forests to Faucets 2.0: Connecting Forests, Water, and Communities. WO-GTR-99 (US Forest Service, 2022); https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/63723

Comte, L. et al. Protected rivers assessment of the United States (PRA-US) v.1.2. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17279334 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by American Rivers. We thank M. Khoury from The Nature Conservancy for the Outstanding Tribal Resource Waters Datasets; D. Hockman-Wert, M. Snyder and R. Flitcroft from the US Forest Service for the Northwest Forest riparian reserve dataset; and all the GIS analysts at various state agencies for the State Wild and Scenic datasets, the Outstanding National and State Resource Waters datasets and the riparian buffer datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and writing (original draft): L.C. and J.D.O. Data collection, curation and formal analysis: L.C. Funding acquisition: C.L., B.G.D. and D.M. Project administration: J.D.O., C.L. and B.G.D. Writing (review and editing): L.C., J.D.O., C.L., B.G.D., J.Z. and D.M.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Lucy Bastin, Matthew Dietz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Overview of the workflow and mechanisms of river protection considered in this assessment.

River conservation [blue], riparian and floodplain conservation areas [green], endangered species critical habitat [magenta], terrestrial protected areas (strict) [pink], terrestrial protected areas (other) [beige], multiple use (special management) [dark grey], and multiple use (other) [grey]. Abbreviations: Protected Area Database of the United States (PAD-US), National Conservation Easement Database (NCED), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Areas of Critical Concern (ACEC), Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRA), National Parks (NP), Research natural Areas (RNA), State Wilderness Areas (SWA), Wilderness Areas (WA).

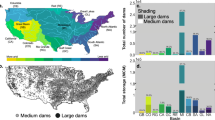

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial distribution of river protection according to major categories of protection.

The thickness of the river segments is scaled according to stream order. To resolve overlap among mechanisms for display purposes, the colors are shown according to the following hierarchy: ONRW/OTRW > Wild and Scenic Rivers > State Wild and Scenic Rivers > Eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers > Scenic Riverways, National Rivers and Recreation Areas > Riparian and Floodplain Conservation Areas > Northwest Forest Plan - Key Watersheds > Watershed Protection Areas > Fishing Management Areas > IUCN I > IUCN II > IUCN III > IUCN IV > IUCN V > IUCN VI > IUCN OCA > Critical Habitat (ESA) > Multiple use > Riparian Buffers. For the terrestrial protected areas, we adopted the International Union for Nature Protected Areas categories, ranging from strict nature reserves (category I) to other conservation areas (category OCA, also including unassigned protected areas), as opposed to designation types to avoid the difficulty in assigning a specific rank to each designation type separately.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Mechanisms of protection of U.S. rivers.

Network showing the contribution of the individual mechanisms of river protection across the entire U.S. where the size of the circles indicates the total percentage of river length protected by a given mechanism, the thickness of the links the degree of co-occurrence among mechanisms, and the colors the major protection categories (only mechanisms representing > 0.01% of the total river network are shown).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Number of protection mechanism per protection class.

Percentage of river length protected according to different classes of the Protected River Index (PRI) and number of individual mechanisms of protection across stream segments.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Representativeness according to freshwater ecoregions.

Percentage of river length protected according to different classes of the Protected River Index (PRI) (colored sectors; right) within freshwater ecoregions and percentage of total river length across freshwater ecoregions (white sectors; left). The inset illustrates the spatial distribution of the freshwater ecoregions corresponding to numbers in brackets on the barplot labels.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Representativeness according to hydrologic regions.

(a) Percentage of river length protected according to different classes of the Protected River Index (PRI) (colored sectors; right) within hydrologic regions (Hydrologic Unit Code 02) and (b) percentage of total river length across hydrologic regions (white sectors; left). The map in (c) illustrates the spatial distribution of hydrologic regions.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Representativeness according to elevation.

Percentage of river length protected according to different classes of the Protected River Index (PRI) within elevation classes (colored sectors; right) and total river length (white sectors; left) across elevation classes. Lowlands < 200 m; Hills = 200-500 m; Mid-altitude = 500-1,000 m; High mountains = 1,000-2,000 m; Very high mountains ≥ 2,000 m.

Extended Data Fig. 8 In-state versus upstream out-of-state viable protected river length among pairs of states in the U.S.

Self-links in the Sankey plot represent in-state viable protected river length within state borders and between-state links upstream out-of-state viable protected river length in the watersheds upstream of the focal states but within the same river basins. Protected river length for each state is expressed as a percentage of in-state and upstream out-of-state total river length, respectively, and not the amount of water exchanged.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Local versus upstream viable protection.

Percentage of viable protection of watersheds (Hydrologic Unit Code 12; HUC12) in the contiguous U.S. where high versus low protection is defined according to the 30% target. The extent of protection is given separately for source watersheds for which upstream protection cannot be estimated.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods and Tables 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Comte, L., Olden, J.D., Littlefield, C. et al. National assessment of river protection in the United States. Nat Sustain (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01693-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01693-8