Abstract

Conventional approaches to policy design often neglect the plasticity of citizens’ beliefs and values upon which policy effectiveness and political sustainability depend. A consequence, by way of illustration, is that environmental policies may crowd out pre-existing green values. Our representative survey of 3,306 Germans finds that enforced restrictions to promote carbon-neutral lifestyles would trigger strong negative responses because they ‘restrict freedom’. This is true even among those who would adopt green lifestyles when voluntary, thus possibly undermining support for green political movements. These results combined with the long-term political consequences of the polarizing reactions to Covid mandates motivate a new approach to climate policy design. We set aside the conventional economic model assuming self-interested citizens, in which there could be no green values to crowd out. Instead, we propose a dynamic approach recognizing that (1) to succeed, essential policies including bans, carbon taxes and the promotion of new technologies must be both implementable and politically sustainable, entailing (2) a critical role for citizens’ green values, which (3) may be either diminished or cultivated, depending on policy design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

In response to the climate challenge, technology and the physical sciences have advanced dramatically; but the social science of implementable and sustainable policy design is still in its infancy. This paper takes up a charge issued by the Nature Sustainability Expert Panel on Behavioral Science for Design, namely that “behavioral science must inform our pursuit of sustainability”. We address what they term the “challenges beyond the built environment”, taking seriously “respectful acknowledgement of users’ intrinsic humanity and desire for autonomy”. We provide evidence that indeed, “design processes … both intentionally and tacitly shape judgement, decision making and actions, and therefore also shape the sustainability of outcomes”, and we discuss implications for sustainable policy design (see pages 2, 8 and 9 of ref. 1).

Consistent with the approach we propose, L. Mattauch, N. Stern and their coauthors warn that poorly designed environmental policies might crowd out background social norms essential to policy effectiveness2. Our research also responds to a warning by K. Nyborg, K. Arrow, P. Ehrlich, S. Levin, E. Weber and other environmental policy scholars: “Climate change, biodiversity loss, antibiotic resistance and other global challenges pose major collective action problems … policy can support social norm changes, helping to address [these] problems” (see page 43 of ref. 3). However, they caution that poorly designed policies may “turn virtuous cycles into vicious ones”. Examples are policies undermining beliefs or values on which the policy’s implementation and continued electoral support depend, as appears to be the case with affirmative action or immigration policies in some countries.

Another example are mandates and restrictions, which are essential tools of climate and public health policy implementation, as shown by their successful deployment to reduce smoking and increase the use of seat belts. However, we provide evidence that even citizens who favour green lifestyles if voluntary are less likely to be favourable if legally enforced, for example restricting the use of cars in cities, room temperature, meat consumption, short-haul flights and purchases of products with substantial carbon footprints. While our data concern lifestyle changes, our approach applies more generally to environmental policy, for example, acceptance of carbon capture and storage technologies or changes in land use to facilitate renewable energies.

The implication for policy design is not to abandon mandates, but instead, to find ways to mitigate or reverse these unintended crowding-out effects of legally enforced restrictions. We provide a model showing that, even in cases where this is not possible, the imposition of mandates can induce a shift from a carbon trap to a green equilibrium.

Our key finding—restrictions may crowd out green values that are required if climate policies are to be effectively implemented and politically sustainable—suggests that we need to rethink the conventional economic approach to policy design4. After presenting our results, we draw on recent models of policy design with endogenous preferences5,6,7 and suggest ways that climate policy design could take account of the plasticity of citizens’ values.

Mandating green lifestyle changes could be counterproductive

The negative responses to restrictions and mandates that provoke these concerns are puzzling in cases where the action targeted by the policy is a costly contribution to a public good. Behavioural experiments indicate that many people are conditional cooperators: they willingly contribute to the public good as long as they believe that most others will as well8.

Policies that include monitoring and penalties for non-compliance would appeal to these conditional cooperators, because they are willing to contribute but fear being taken advantage of by free-riders who reap the benefits of the public good without contributing9,10. If conditional cooperators are prevalent, we would expect that enforcement would make adopting green lifestyles more attractive. This is not what we found.

We conducted a survey of a representative sample of 3,306 Germans on their responses to policies to promote less carbon-intensive lifestyles, conditional on their being either enforced or instead recommended but voluntary.

To explore whether bans or restrictions may crowd out green values, it is essential to treat a person’s pro or con attitudes towards their adopting the behaviour targeted by the policy (‘being okay with it’ or not) as distinct from either support for the policy or obedience to the law in the case of an enforced mandate or ban. Therefore, our questions ask about the respondent’s attitude towards themselves doing what the policy recommends or requires, not their support for the policy (that is, their normative view of whether or not this policy should be in place) or whether a person would comply with a legally imposed and enforced measure. We explain this distinction in greater detail in Methods.

We asked, for example: “To what extent do you agree with foregoing the use of a car in city centres if… not using a car in city centres is strongly recommended by the government, but remains voluntary?… a ban on cars in city centres (apart from exceptional cases) is introduced and checked by the government?” Answers were given on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not agree at all) to 4 (fully agree), which we term the level of agreement.

A negative response to restrictions—less agreement with adopting the behaviour prescribed by the policy if enforced rather than voluntary—is the result of what is termed control aversion in economics11. We measure the extent of control aversion by the Likert scale difference in agreement induced by the absence or presence of enforcement. A control-averse response reflects crowding-out of intrinsic motivation. Greater agreement in the case of an enforced rather than a voluntary policy reflects crowding-in.

We asked the same people a similar set of questions about Covid policies (our survey was conducted during the fourth wave of the pandemic). The comparison with responses to Covid policies provides us with a well-studied benchmark of control-averse responses to public policies and their broader political ramifications. Comparing the two domains will also provide insights on the mechanisms behind control aversion and allow more adequate understanding of control aversion as a generic psychological trait with some domain-specific aspects.

In three previous waves of our survey, the extent of ‘agreement’ with voluntary Covid policies provided accurate predictions of the subsequent observed voluntary take-up of contact tracing apps and vaccinations, suggesting external validity of our method. Moreover, control aversion with respect to Covid policies was remarkably robust over four survey waves starting early in the pandemic (including the new data presented here), despite rapidly changing information, policies enacted, and severity of the pandemic12,13. Thus, our survey evidence appears to measure relatively stable preferences capable of explaining individual behaviour with respect to public policies.

Results

More control aversion for climate than for Covid policies

We find substantial control aversion for climate policies, at levels exceeding that for vaccination mandates and other enforced Covid measures. The pie charts in Fig. 1 show that control-averse responses are frequent across all policies (orange slices). There are also some who exhibit crowding-in, responding positively to enforcement (blue slices), possibly conditional cooperators as we hypothesized above.

Figure 1 also shows cumulative distributions of agreement under enforced (red) versus voluntary (blue) policies. Across all domains, most respondents agree with adopting the behaviour if the policy is voluntary (blue step functions, Likert levels 3 and 4). Respondents agree less if the policy is enforced (red step functions), especially for those targeting climate. Across all ten policies, enforcement provokes opposition (levels 0 and 1) from a minimum of one-fifth (Covid masks) to a maximum of three-fifths (restricting meat) of the sample.

a–e, Responses to climate policies: limiting living room at maximum 70° F or 21° C (a), limiting meat consumption (b), no cars in inner cities (c), no short-haul flights (d) and avoiding CO2 heavy products (e). f–j, Responses to Covid policies: using tracing app (f), getting vaccinated (g), limiting contacts (h), limiting travels (i) and wearing a mask (j). Pie charts show the shares of types of responses to enforced versus voluntary policies. Responses to enforcement are negative (reflecting control aversion or crowding-out) if agreement is lower in case of enforced rather than voluntary policies and analogously for positive responses (crowding-in). The underlying choice distributions are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1. Cumulative distributions show agreement in case of enforced (red) versus voluntary (blue) policies. For example, the cumulative distributions in a show the percentage of respondents who fully agree (agreement level 4) with limiting room temperature if it is enforced or voluntary, that is, 15% or 43%, respectively. The sum of those expressing agreement levels 3 and 4 amounts to 25% or 63%, respectively, in the enforced or voluntary cases. Strongest opposition (agreement level 0) was expressed by 43% or 11%, respectively, if enforced or voluntary (the final step on the right in the upper left graph). The light red area between the two-step functions shows the cost of control. To control for their possible impact on the climate questions, 40% of our sample were not asked the Covid questions. Accordingly, for the climate policies in a–e, sample sizes are n = 3,272, n = 3,262, n = 3,268, n = 3,269 and n = 3,263, respectively; and for the Covid policies in f–j, sample sizes are n = 1,953, n = 1,951, n = 1,948, n = 1,949 and n = 1,949, respectively.

The area between the blue and red step functions is what we term the ‘cost of control’ on citizens’ attitudes, namely the average difference in agreement between the voluntary and enforced cases. The measure captures both the frequencies of types of responses to control (as indicated by the pies in Fig. 1) as well as the different strength of their responses in the two cases (the step functions).

Averaging across the two sets of policy domains, the cost of control is 52% greater for climate than for Covid policies (95% CI: 0.40, 0.65; Supplementary Equations (1) and (2)). The persistence of our panel-based measures of control aversion covering 2 years of exposure to Covid policies12,13 provides no evidence that the costs of control would be substantially reduced by peoples’ mere exposure to mandated climate policies.

We exploit our available data in the two domains, climate and Covid, to better understand the nature of control aversion as a psychological trait. Thus, we analyse control aversion across the ten different policies using principal components analysis. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, the first three principal components appear to capture, respectively, (1) generic control aversion as a psychological trait, irrespective of the particular policy, (2) differential responses to Covid and climate policies and (3) a component we interpret as the degree of personal invasiveness of the policy (changing diet or room temperature, getting vaccinated or a tracing app may be perceived as invasive, unlike less invasive policies such as, say, mask wearing).

On this basis, we consider control aversion to be a generic psychological trait with domain-specific aspects, some of which are susceptible to policy design. We will also provide evidence that in the policy-specific domain, the extent of control aversion is not fixed and can be substantially mitigated or even reversed by people’s attitudes and beliefs.

Belief in policy effectiveness may crowd-in agreement

Figure 1 shows that the level of agreement with adopting the targeted behaviour is substantial and differs little across voluntary policies. However, negative responses to enforcement differ markedly, control aversion being particularly pronounced for the policies we term invasive (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3).

In regression models (exemplified by cars in Fig. 2a) we find similar patterns for all policies. Not surprisingly, trust in public institutions and climate concern increase agreement and also for some policies mitigate control aversion. However, the associated effect sizes along with the sociodemographics are modest (Supplementary Fig. 4 shows the full regressions for all climate policies).

a,b, Linear regressions for attitudes and beliefs (a) and political party inclination (b) for the example of not using cars in inner cities predicting agreement in case of voluntary (blue) and enforced (red) policies (left) and predicting control aversion (right). Parties in b are ordered according to their seating in the German parliament corresponding to their political orientation from left (The Left, at the top) to right (AfD, at the bottom). Shown are the estimated normalized coefficients and the 95% CIs. The full set of regressions including sociodemographic controls (not shown here) for all the five climate policies is provided in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 as well as Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The sample sizes for a are n = 3,067 if voluntary, n = 3,066 if enforced and n = 3,063 for control aversion. The sample sizes for b are n = 2,463 if voluntary, n = 2,463 if enforced and n = 2,459 for control aversion. c,d, Belief in the effectiveness of a policy (c) and not feeling restricted in one’s freedom (d) may reduce control aversion. Average difference in agreement in case of voluntary versus enforced implementation of a policy (in Likert scale units) depending on participants’ beliefs in policy effectiveness (c) and perceived restriction of freedom in the mandated case (d). A positive average reflects average control aversion (crowding-out) on the sample level, whereas a negative average reflects crowding-in. Perceived freedom restriction and belief in policy effectiveness were measured on a five-point Likert scale (as explained in Supplementary Table 1). Data are represented as mean values with 95% CI. The underlying distributions are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. The sample sizes depend on the number of respondents on the two extremes of the effectiveness and freedom restriction scales. In c, sample sizes for climate policies are (in the order of the bars from left to right): n = 434, n = 518, n = 479, n = 614, n = 381, n = 772, n = 223, n = 1,329, n = 254 and n = 775; and for Covid policies, sample sizes (in the order of the bars from left to right) are: n = 546, n = 180, n = 253, n = 889, n = 191, n = 547, n = 193, n = 588, n = 191 and n = 923. In d, sample sizes for climate policies are (in the order of the bars from left to right): n = 946, n = 690, n = 962, n = 496, n = 800, n = 736, n = 457, n = 1,397, n = 473 and n = 636; and for Covid policies, sample sizes (in the order of the bars from left to right) are: n = 386, n = 729, n = 415, n = 836, n = 494, n = 273, n = 390, n = 422, n = 298 and n = 716.

An individual’s self-assessed measure of altruism is associated with both greater agreement in the case of voluntary policies and heightened control aversion. This is in line with the mechanism underlying the crowding-out phenomenon: pre-existing pro-social motivations are diminished by control, and for entirely self-interested subjects, there is nothing for control to crowd out14.

As expected from cross-national and other evidence15,16, an important predictor of agreement in both the voluntary and enforced cases is the belief that the targeted behaviour is an effective way to address the climate challenge (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). In most cases, belief in policy effectiveness also strongly mitigates control aversion. This is consistent with the psychologist M. Lepper and his coauthors’ reference to the “detrimental effects of unnecessarily close… supervision or the imposition of unneeded temporal deadlines” or other “superfluous constraints” (see page 62 of ref. 17). In Lepper’s framework, an ineffective policy would be more likely to crowd out positive motivations because it would be seen as ‘unnecessary’, ‘superfluous’ or ‘unneeded’.

Figure 2c illustrates the substantial reduction of control aversion associated with a strong belief in policy effectiveness. Among those convinced that mask wearing and travel limitations are effective, enforcement actually crowds-in agreement, average agreement being greater for enforced than for the voluntary implementation.

From our panel survey data on Covid measures following the same respondents over the course of the pandemic, we also know that the degree of agreement changes when beliefs and attitudes change12,18. This has important implications for policy design, even though we cannot establish that the differences in agreement associated with the belief in effectiveness in Fig. 2c represent causal effects. For example, an avid driver who is concerned about climate but also strongly opposed to restrictions on the use of cars in city centres may be more comfortable believing that car bans are not an effective way to address climate change. Here the causal effect would run from disagreement with the targeted behaviour to a belief in the ineffectiveness of the policy.

Nonetheless, changing peoples’ beliefs about policy effectiveness could support agreement with the targeted green behaviour. If a person came to believe that, say, banning cars from cities was effective in mitigating climate change, dropping one’s opposition to the car ban would reduce cognitive dissonance19.

However, the climate policies we identified as invasive (reducing meat consumption and room temperature) are distinctive in this respect: control aversion in these cases appears to be immune to respondents’ belief in policy effectiveness, trust in public institutions or concern about climate change. It appears that aversion to violations of one’s perceived personal space20 (here affecting a person’s body) may have a lexical priority that is not readily ameliorated by policy design, suggesting that responses were based on feelings rather than cognitive assessments21.

Control ‘restricts my freedom’

The psychological basis of control aversion is termed reactance, introduced by J. W. Brehm22 and described as an “an unpleasant motivational arousal that emerges when people experience a threat to or loss of their free behaviours”23. For all five of the climate policies, the respondents’ perception that an enforced policy ‘restricts my freedom’ is the most important predictor of control aversion (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 2d shows that those who believe that the enforced version of the policy ‘does not restrict my freedom at all’ are much less control averse. (Again, we cannot establish this relationship as causal.) Similar to the belief in effectiveness, for those who do not perceive wearing masks and travel limitations as freedom restrictions, enforcement crowds in agreement.

The climate policy for which respondents were least likely to feel that enforcement restricts their freedom (Supplementary Table 1)—limiting short-haul flights—is also the policy for which there are the fewest control-averse types (as evident from Fig. 1).

While an important predictor of control aversion, the perception that an enforced policy restricts freedom is not as common as one may think. Although differences among the policies are substantial, for none of the ten climate and Covid policies is there a majority that has this sentiment (between 25% and 48%, for the cases of short-haul flights and meat, respectively, either weakly or strongly feel that mandates would restrict their freedom). A challenge for climate policy design is not only that they tend to be perceived as more freedom restricting, but also that it is more difficult to frame adopting a green lifestyle as freedom-enhancing compared with Covid policies (for example, successful mask and vaccination mandates restore freedom of travel and in-person interactions).

Consistent with the importance of the sense that control ‘restricts freedom’ as a contributor to control aversion, the heightened and robust control aversion for limiting meat consumption and home heating may also reflect that suitable alternatives are lacking, which has been shown to have important effects on climate policies in other settings24. The availability and attractiveness of green alternatives (for example, plant-based food and heat pumps) may thus be critical in supporting higher levels of agreement and mitigating control aversion by reducing perceived freedom restrictions. For example, decent train connections in Europe may be a reason why ‘limiting short-haul flights’ is seen less as restricting freedom and evokes less control aversion among Germans than other policies.

We also find that control aversion as well as agreement in the voluntary and enforced cases of policy implementation are associated with political party affiliation (as shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figure 5). Respondents leaning towards the more left-wing parties express higher agreement, while in particular supporters of the German right-wing populist party AfD agree less with the behaviours targeted by the climate policies. Left-minded respondents are less control averse and right-wing supporters are more control averse—except for policies we term privacy intrusive, where political party support has no explanatory power.

We conjectured that there might be two framings that might mitigate or even reverse crowding-out: conditional cooperation and moral values. First, following our above reasoning about conditional cooperators, knowing that free-riders would be punished should make people feel more comfortable contributing. Second, derived from the theory of the expressive function of law25,26, we framed limiting our carbon footprint as a shared moral imperative for which we hypothesized that prohibition would affirm society’s values rather than limit one’s freedom. These framings (compared to a neutral or no frame, as shown in Supplementary Table 4) had virtually no effect on respondents’ agreement levels and failed to mitigate crowding-out.

Does our evidence suggest that mandates to alter individual behaviour should be abandoned by policy-makers? This is not an implication of our results. We illustrate this using a model of policy design as an equilibrium selection problem.

Mandates designed to escape a carbon trap

Imagine a policy-maker who intervenes in a dynamic process seeking to displace a society from a carbon trap to a green equilibrium, despite the presence of control aversion.

Consider a ban on cars in city centres, except for electric cars. Assume that in the absence of the ban, e-vehicles (EVs) will remain a small fraction of all vehicles, but consistent with our results, introducing the ban will crowd out green attitudes, reducing the value that people place on driving an EV as a climate mitigating action. We show that in this setting, even a temporary ban nonetheless can induce a dynamic of EV adoption, leading most people to give up conventional cars. Here the policy designer uses a mandate (temporary car ban) to induce a shift from a self-sustaining carbon trap to a self-sustaining green equilibrium (termed equilibrium selection).

To represent this process, we extend a model of EV adoption developed by the second author as a member of the CORE team27. In the model, there are two kinds of vehicle—powered by either conventional carbon-based internal combustion (c-vehicles) or electric batteries (EVs). The costs of owning and operating an EV are lower the more other EV-users there are, for two reasons.

First, if there are few EVs, then building charging stations will not be profitable, so they will be rare and far between. Second, economies of scale in the EV production imply that the more are being produced, the lower the price at which they can be sold for a profit. We assume that the costs of owning and operating a c-vehicle, by contrast, do not depend on the number of other c-vehicles on the road. These assumptions are illustrated in Fig. 3a, were cc and ce(et) are the costs of operating a conventional and an electric vehicle, respectively, and et is the fraction of all vehicles that are electric in period t.

a, Costs of operating EVs and c-vehicles. b, Adoption dynamic curves (ADCs) without and with a car ban. In b, the solid blue line is the initial ADC. An equilibrium is any point where the ADC crosses the ray from the origin (fraction of EVs unchanged). There is a green EV equilibrium (G) and the status quo brown carbon-based equilibrium (B). The arrowheads on the blue solid ADC show the out-of-equilibrium dynamics of the system. Both the carbon-based (B) and the EV-based (G) equilibria are stable, while T, a tipping point, is an unstable equilibrium. The dashed ADCs show the effects of substantial (red) and less substantial (blue) crowding-out due to control aversion in reaction to the car ban.

In the model, people value an EV as a climate mitigating action. We capture this green value by vi, defined as the additional cost of an EV that makes individual i indifferent between the two modes of transport.

We assume that v is normally distributed with parameters such that some people prefer EVs even if few are being produced and consequently the cost disadvantage is substantial. Correspondingly, we assume that a few are sufficiently pro-carbon that they will not purchase an EV, even if all other households had done so, as a result incurring higher costs than those driving EVs.

In any period, a fraction of people buy a new vehicle, with person i purchasing an EV if ce(et) − vi < cc. Figure 3b shows an adoption dynamics curve (ADC) indicating how many will be driving electric vehicles next period (t + 1), for every level of EV owners as a fraction of all drivers this period (t). The convex and then concave (S-shaped) nature of the ADC results from the normal distribution of green values, v, combined with economies of scale in the production of EVs (Fig. 3a). Similar ADCs, but instead based on conformist preferences, are the foundation of models of the social multiplier of policy interventions18,28.

The imposition of a ban on c-vehicles in cities has two countervailing effects. First, it undermines individuals’ green values vi, resulting in a control-averse response to the ban (which we have documented), shifting the ADC down. Second, the ban increases the cost of operating a c-vehicle (which would need to be supplemented by taxis or public transport), shifting the ADC up.

In a worst-case scenario as illustrated by the red dashed line in Fig. 3b, the crowding-out effect dominates the effect of increased costs for c-vehicle owners to such an extent that it shifts the ADC so far down that there is no green equilibrium that would be self-sustaining in the absence of a permanent mandate.

The case represented by the blue dashed curve—moderate crowding-out—is more optimistic: a car ban that led the fraction of individuals buying EVs to exceed Z′ (corresponding to the new tipping point T′) would induce further voluntary adoptions of EVs. This would then allow the ban to be rescinded, possibly restoring the initial ADC (solid blue line) if the reactance resulting from the ban does not persist once the ban is rescinded and resulting in a convergence to the green equilibrium G. Knowing the underlying dynamics of EV adoption, the policy designer could thus intervene with a temporary ban to select the green equilibrium, which, once attained, is sustainable in the absence of the ban.

Thus, the fact that bans or mandates induce control-averse responses does not imply a rejection of such policies. The possibility that policies may crowd out pre-existing green values substantially complicates the policy designer’s problem and requires an overhaul of the conventional approach to policy as formalized in the economic field of mechanism design.

Climate policy as a mechanism design problem

Mechanism design is the economics analogue to engineering. Having identified a goal (for example, reducing greenhouse gas emissions), the mechanism designer derives mechanisms (rules of the game) to be implemented by policies such that, given citizens’ values and beliefs, acting independently they will behave in a way that implements the mechanism designer’s goal.

We extend the conventional assumptions of mechanism design in two ways: recognizing the plasticity of green values as well as the fact that successful green policies must be politically sustainable.

First, as opposed to the conventional view taking actors’ values and beliefs as given, we recognize that they may be adversely affected by the mechanisms introduced (as our evidence that green values may be crowded out shows). These effects may include negative spillovers, whereby a control-averse response to a particular policy (for example, ban on cars) is extended to climate policies more generally, undermining support for related interventions29. An example is control-averse responses to mask and vaccination mandates during the pandemic, which appear to have spilled over to generalized hostility towards health professionals and eventually towards governments and the entire scientific community.

These negative spillovers are also possible in the cases we have studied, because the degradation of green values due to control aversion may not be specific to particular policies (consistent with our principal component analysis above). Thus, the adverse side-effects of enforced policies targeting individual lifestyles potentially spill over and undermine support for other needed interventions.

Second, we abandon the static view where the policies under consideration will be set in place by some fictive mechanism designer. Instead, we conceive policies as the result of a democratic political process and a successful policy must be sustainable given this process. We will illustrate our extensions of mechanism design by the example of our empirical data—crowding-out in response to mandates or restrictions. However, our extension of conventional mechanism design applies more generally, including the use of monetary incentives or penalties.

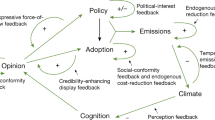

Figure 4 presents both the conventional mechanism design approach and our proposed extensions that recognize the importance and plasticity of citizens’ values and beliefs along with the requirement that policies must be sustainable. The green labels illustrate an application of one of our empirical results, namely the likely control-averse reaction to a ban on cars in cities. The black labels represent the general case.

This representation is an extension to environmental policy of a model of the general problem of optimal policy design with endogenous preferences5,6. Labels in black represent the main concept, labels in green illustrate an environmental policy, the purple dashed arrow shows what is neglected in the conventional approach and is the focus of this article; other effects are represented in grey.

In the standard economic approach, the policy-maker implements a set of incentives (including penalties for violating prohibitions) to alter the expected economic costs and/or benefits of some targeted pro-social or pro-environmental action, as represented by the two causal arrows in the upper part of Fig. 4.

However, as our evidence shows, policies affect not only the material benefits of taking an action, but also the citizen’s values (negatively or positively, represented by minus and plus signs on the dashed purple arrow). In the standard approach, the policy designer does not take account of the purple dashed arrow in the lower part of the figure, either because the citizens’ values motivating the targeted green action in the absence of the policy are assumed to not exist or, if they do, are assumed not to be affected by the policy.

Our evidence of a negative effect of a car ban on citizens’ desire to limit their own car use is illustrated by the purple dashed arrow, which by our evidence, has a negative sign—unless (as we have seen) citizens’ belief in the effectiveness of the ban were sufficient to mitigate or even reverse this control-averse response, or if the ban is not perceived as restricting freedom.

Also shown in Fig. 4 are possible adverse effects of incentives on citizens’ values that spill over to other environmental actions. For example, a control-averse reaction to a car ban may degrade citizens’ pro-environmental policy preferences and support for the political movements advocating them. This may compromise citizens’ future advocacy in support of or opposition to the car ban itself, represented by the lower arrow from citizens’ political action to policy.

The importance of green values and their plasticity with respect to policies suggests that a valuable addition to the environmental policy-maker’s toolbox are approaches to not only avoid crowding-out, but also to cultivate green values. Exploring this crowding-in opportunity requires going beyond the usual framework for the study of institutions and policy design.

Discussion

To fully exploit the opportunities for climate mitigation opened up by recent advances in the physical sciences and engineering, we need a new behavioral science of climate policy design, as advocated by the Nature Sustainability Expert Panel on Behavioral Science for Design.

We have documented a source of failure: control-averse responses to restrictions and mandates that could reduce or even reverse the intended effects of policies to promote green lifestyle changes and instead cultivate anti-environmentalist values more generally, which would render the policies unsustainable politically.

To mitigate climate change, therefore, policy designers need to ensure that climate policies are themselves sustainable in the long run. Beyond mitigating or avoiding the crowding-out we have documented, well-designed policies should aim at cultivating and enhancing the values and beliefs essential to sustainable climate mitigation. Both experimental and field evidence point to successful examples of policies that can crowd-in green values30,31. The small tax on plastic grocery bags imposed in Ireland in 2002, for example, virtually eliminated their use, apparently by heightening the salience of green values32.

Bringing these aspirations to practice will require a reconsideration of the widely used economic approach to policy design based on the idea that citizens are entirely self-interested with given beliefs. We have proposed instead an empirically based dynamic approach recognizing (1) that successful policies must be both implementable and politically sustainable in a liberal democracy and (2) the resulting critical role of citizens’ green values and beliefs, which (3) are not given but may be either diminished or cultivated by climate policy design.

Methods

The wave of our survey reported here was conducted in April 2022. This was during the fourth wave of the Covid pandemic and before the energy crisis in Germany following the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, which prompted policies such as limiting room temperature, and also before the subsequent prominent public discussion about heat pumps in Germany.

In addition to our questions on agreement with adopting the behaviour prescribed by the policy if voluntary and if enforced, we also elicited respondents’ sociodemographics, their climate concern, beliefs about the effectiveness of the policies, their perception of freedom restrictions in the case of mandates and trust in public institutions (Supplementary Table 1).

The survey this paper relies on was the fourth wave of a panel survey on Covid policies, with the questions on climate policies being introduced only in this wave. The core methods are unchanged over the course of the panel, as documented in our earlier work12,13,18 and below.

The questions

To study the possibility that enforcement may crowd out intrinsic, other-regarding or green motivations, it is essential to isolate how individuals feel about adopting the behaviour that the policy seeks to promote from confounds such as their support of the policy or their willingness to obey the law. Therefore, our questions ask about the extent to which the respondent ‘agrees’ with (in the sense of ‘being okay with’) the behaviour prescribed by the policy and not whether a person supports and would comply with a legally imposed and enforced policy.

It is likely that people might not agree with the prescribed behaviour but still comply with it because the costs of non-compliance are too high. This distinction is crucial to detect crowding-out due to enforcement. The answers to our questions in case of enforcement allow us to identify the share of people who are comfortable (‘agree’) with adopting the behaviour in case it is mandated and enforced which could be very different from the share of citizens who are not okay with it but would comply with it under enforcement—possibly being left with heightened negative emotions such as anger, aggression, frustration and hostility towards their government or those advocating the policy.

To study whether enforcement can succeed in implementing a measure (not the question we are asking), an appropriate survey question would enquire about intended behaviour, not subjective attitudes. However, a positive answer to such a question is uninformative about subjects’ attitudes behind compliance. Instead, it measures the extent to which people state that they will obey the law and, presumably, most Germans would state in a survey that they would comply with a mandatory policy. To understand the crowding-out phenomenon, we need to elicit people’s attitudes behind their compliance behaviour and not their willingness to comply with enforcement per se, which is a different research topic.

Moreover, our survey questions on agreement in case of voluntary implementation have a strong normative content (‘strongly recommended by the government’). This serves to stress that even in the absence of enforcement, compliance is clearly desirable. Asking the question on agreement in case of voluntary policies without stressing its normative importance would give the impression that non-compliance is equally permitted and acceptable, which is not the way in which voluntary compliance has been promoted in actual policy-making.

Finally, the way we formulated our questions on agreement is not meant to elicit policy support in general. It is possible that people do not agree with leading a more CO2-neutral lifestyle themselves, although are in full support of such policies nonetheless.

The design

To identify differential individual responses, all subjects were asked to state their level of agreement with themselves adopting the behaviour prescribed by the policy in two cases: if it is advised but voluntary and if it is enforced.

In an earlier survey on Covid policies, we investigated the possibility of a demand effect due to our within-subjects design, that is, asking a subject to answer both questions. For this purpose, we implemented a between-subjects design confronting respondents with only one alternative (either voluntary or enforced) and obtained results similar to those resulting from asking each subject to answer both questions as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Further, we also confirmed that altering the order of the alternatives in a within-subjects design did not affect average agreement with enforced or voluntary Covid policies in a meaningful way.

To limit a potential spillover effect—a subject answering questions in a way to minimize inconsistency—the module containing the questions on agreement and the module containing the questions about policy effectiveness and the perceptions of freedom restrictions were separated by unrelated modules.

The survey

The questions were embedded in an online survey on Covid and climate initiated by the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’ at the University of Konstanz, who also predetermined the sample size.

Participants were recruited from a commercial online access panel administered and remunerated by the survey provider respondi, which usually conducts market research. Membership of the respondi survey pool and participation in its surveys is voluntary and follows a double opt-in registration process. Participation is incentivized with tokens that can be exchanged for goods. Given this material incentive and the usual marketing research done using the pool, people registered there are unlikely to have atypical intrinsic or social motivation relevant to the subject matter of the survey. This is important because otherwise, voluntary participation in the survey might create a sample bias in favour of voluntary policies.

The survey was implemented and run by the surveyLab at the University of Konstanz from 21 to 28 April 2022. Our questions concerning climate policies in case they are voluntary or enforced were part of a larger interdisciplinary survey on topics related to inequality, Covid and climate. Invited survey participants self-selected into the online panel titled ‘Living in exceptional circumstances’, and subjects were not aware of the specific topic of any module (including ours) when agreeing to participate.

Before and after the modules, respondents answered a series of questions on sociodemographics, attitudes, beliefs and other controls. Basic demographics were mandatory to answer, in particular the questions concerning the sampling criteria. All other questions were voluntary and subjects were free to quit the survey at any time.

LimeSurvey v.3.22.27 was used to program and conduct the survey. Invitations were handled by the commercial provider respondi. The data were analysed using Stat/SE 15.1.

The participants

Participants were required to be 18 years of age or older German-speaking residents of Germany. The quota reflected the resident population in terms of (the marginal distributions of) age group, gender, education and region (with a double quota for East Germany). The resulting distribution of characteristics in our sample on key sociodemographics and the respective national characteristics are provided in Supplementary Table 5. All results reported in the paper are based on unweighted observations. Using sample weights to achieve full representativeness on observables has little effect on our main findings.

Unavoidably, we cannot exclude the possibility that our sample is unrepresentative on unobservables that would have affected our results33,34. However, we find it difficult to provide a compelling empirical illustration of what might be those unobservables whose exclusion would bias our results. Supplementary Table 6 compares a dimension that was not used to create our sample (political party inclination) with representative surveys at the time of our survey. The distribution of party preferences in our survey is close to the average of these representative voting polls.

The mean age of the sample was 44 years (s.d. 14 years) and 46% were female. The survey was the fourth wave of a panel survey on Covid and we restrict our sample to respondents who have not participated in any of the earlier waves.

The following exclusion criteria were defined by the surveyLab: dropout during the survey, nonsense responses to open questions, speeders and straightlining. Exclusions were performed by the surveyLab based on an independent standard quality check, without any involvement of the authors of this article. We use list-wise exclusion of subjects with missing data in the variables used for the regressions.

The treatments

Our questions on Covid policies were asked in the first part of the survey and the questions related to climate change were asked in the second part. To control for a potential spillover effect of the Covid on the climate questions, two-fifths of the participants were not asked the Covid questions, such that our sample size for the Covid questions is 1,976 participants and the full sample of 3,306 participants answered the climate questions. Whether or not respondents were asked the Covid questions has virtually no effect on the results reported in our paper.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Konstanz, IRB 20KN09-006. All subjects provided informed consent. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations. This research does not result in stigmatization, incrimination, discrimination or personal risk to participants.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The anonymized survey data have been deposited at GESIS SowiDataNet datorium (German Data Archive for the Social Sciences) and are available at https://doi.org/10.7802/2961 (ref. 35). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code files to replicate the results of the paper are available at GESIS SowiDataNet datorium: https://doi.org/10.7802/2961 (ref. 35).

Change history

01 January 2026

In the version of this article initially published, current ref. 32 appeared as ref. 27, while ref. 27 (Carlin et al., 2025) has now been updated. The references are amended in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Lotz, L. et al. Twenty Questions About Design Behavior for Sustainability (International Expert Panel on Behavioral Science for Design, 2019); https://www.nature.com/documents/design_behavior_for_sustainability.pdf

Mattauch, L., Hepburn, C., Spuler, F. & Stern, N. The economics of climate change with endogenous preferences. Resour. Energy Econ. 69, 101312 (2022).

Nyborg, K. et al. Social norms as solutions. Science 354, 42–43 (2016).

Laffont, J. J. Public Economics (MIT, 2000).

Bowles, S. Policies designed for self-interested citizens may undermine ‘the moral sentiments’: evidence from economic experiments. Science 320, 1605–1609 (2008).

Hwang, S.-H. & Bowles, S. Optimal incentives with state-dependent preferences. J. Public Econ. Theory 16, 681–705 (2014).

Besley, T. & Persson, T. The political economics of green transitions. Q. J. Econ. 138, 1863–1906 (2023).

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S. & Fehr, E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 71, 397–404 (2001).

Shinada, M. & Yamagishi, T. Punishing free riders: direct and indirect promotion of cooperation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 28, 330–339 (2007).

Rustagi, D., Engel, S. & Kosfeld, M. Conditional cooperation and costly monitoring explain success in forest commons management. Science 330, 961–965 (2010).

Falk, A. & Kosfeld, M. The hidden costs of control. Am. Econ. Rev. 96, 1611–1630 (2006).

Schmelz, K. & Bowles, S. Opposition to voluntary and mandated COVID-19 vaccination as a dynamic process: evidence and policy implications of changing beliefs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2118721119 (2022).

Schmelz, K. Enforcement may crowd out voluntary support for COVID-19 policies, especially where trust in government is weak and in a liberal society. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016385118 (2021).

Bowles, S. & Polania-Reyes, S. Economic incentives and social preferences: substitutes or complements?. J. Econ. Lit. 50, 368–425 (2012).

Dechezleprêtre, A. et al. Fighting climate change: international attitudes toward climate policies. Am. Econ. Rev. 115, 1258–1300 (2025).

Fosgaard, T. R., Pizzo, A. & Sadoff, S. Do people respond to the climate impact of their behavior? The effect of carbon footprint information on grocery purchases. Environ. Resour. Econ. 87, 1847–1886 (2024).

Lepper, M. R., Sagotsky, G., Defoe, J. & Greene, D. Consequences of superfluous social constraints: effects on young children’s social inferences and subsequent intrinsic interest. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 42, 51–65 (1982).

Schmelz, K. & Bowles, S. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccination resistance when alternative policies affect the dynamics of conformism, social norms, and crowding out. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2104912118 (2021).

Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford Univ. Press, 1957).

Dosey, M. A. & Meisels, M. Personal space and self-protection. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 11, 93 (1969).

Hsee, C. K. & Rottenstreich, Y. Music, pandas, and muggers: on the affective psychology of value. J. Exp. Psychol. 133, 23 (2004).

Brehm, J. W. A Theory of Psychological Reactance (Academic, 1966).

Steindl, C., Jonas, E., Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E. & Greenberg, J. Understanding psychological reactance: new developments and findings. Z. Psychol. 223, 205–214 (2015).

Lanz, B., Wurlod, J.-D., Panzone, L. & Swanson, T. The behavioral effect of Pigovian regulation: evidence from a field experiment. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 87, 190–205 (2018).

Galbiati, R. & Vertova, P. Obligations and cooperative behaviour in public good games. Games Econ. Behav. 64, 146–170 (2008).

Sunstein, C. On the expressive function of law. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 144, 2021 (1996).

Carlin, W., Bowles, S., Stevens, M., Osei-Twumasi, O. & Tipoe, E. Economic dynamics: Financial and environmental crises. in Unit 8, The CORE Econ Team, The Economy 2.0: Macroeconomics. https://books.core-econ.org/the-economy/macroeconomics/08-financial-environmental-crises-01-lehman-brothers-collapse.html (2025).

Konc, T., Savin, I. & van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. The social multiplier of environmental policy: application to carbon taxation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 105, 102396 (2021).

Truelove, H., Carrico, A., Weber, E. U., Raimi, K. & Vandenbergh, M. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: an integrative review and theoretical framework. Glob. Environ. Change 29, 127–138 (2014).

Grillos, T., Bottazzi, P., Crespo, D., Asquith, N. & Jones, J. P. G. In-kind conservation payments crowd in environmental values and increase support for government intervention: a randomized trial in Bolivia. Ecol. Econ. 166, 106404 (2019).

Galbiati, R. & Vertova, P. How laws affect behaviour: obligations, incentives and cooperative behavior. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 38, 48–57 (2014).

Bowles, S. The Moral Economy—Why Good Incentives are no Substitutes for Good Citizens (Yale Univ. Press, 2016).

Oster, E. Unobservable selection and coefficient stability: theory and evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 37, 187–204 (2019).

Dutz, D. et al. Selection in Surveys: Using Randomized Incentives to Detect and Account for Nonresponse Bias (NBER, 2021).

Schmelz, K. & Bowles, S. Replication data for: ‘An empirically-based dynamic approach to sustainable climate policy design’. GESIS SowiDataNet https://doi.org/10.7802/2961 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank U. Fischbacher for suggesting important improvements, the research group at the Thurgau Institute of Economics (TWI), in particular A. Asri, V. Asri, F. Dvorak, I. Wolff and K.S.’s colleagues on the Covid-19 ad hoc survey task force team of the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’ at the University of Konstanz (in particular M. Busemeyer, C. Diehl and S. Koos) for valuable criticism and suggestions on the survey design; the surveyLab, T. Hinz and T. Wöhler for support implementing the survey; J. Camilo Cardenas Campo, J. Donges, M. Dumas, T. Fosgaard, S. Goldlücke, M. Greenberg, S. Haustein, K. Nakagawa, P. Martinsson, L. Mattauch, P. Sacket, D. Schrag, A. Stier, A. Teytelboym, M. Veronesi, E. Wood, seminar participants at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the Research Seminar on Environmental, Resource and Climate Economics (RSERC) at TU Berlin, the Behavioral Science for Policy Lab (BSPL) at Princeton University, as well as participants of our SFI working group on sustainable climate policies for helpful comments; R. Strerath for research assistance and C. Seigel of the Santa Fe Institute library. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under the Excellence Strategy of the German Federal and State Governments (gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) im Rahmen der Exzellenzstrategie des Bundes und der Länder–EXC-2035/1–390681379, K.S.), the Santa Fe Institute (S.B. and K.S.), the Technical University of Denmark (DTU, K.S.), the TWI (K.S.) and the Erika and Werner Messmer Foundation (K.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S. conceived of the initial research question and the Covid survey items. K.S. and S.B. designed the climate survey questions, performed the research, analysed data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Tobias Brosch and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 The effect of beliefs and attitudes on control aversion.

Distributions of differences in agreement for (a) those with no and a strong belief in the effectiveness of a policy, and (b) those who do not at all or do strongly feel restricted in their freedom by a mandate. For each box, the center line represents the median, the bottom represents the 25th percentile, and the top represents the 75th percentile. The whiskers indicate the lower and upper adjacent values (25th percentile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range, that is, the difference between the 75th and 25th quartiles, and 75th percentile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range, respectively). The sample sizes for (a) correspond to Fig. 2c and the sample sizes for (b) correspond to Fig. 2d.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary notes and explanations, survey questions, Figs. 1–6 and Tables 1–6.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmelz, K., Bowles, S. An empirically based dynamic approach to sustainable climate policy design. Nat Sustain (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01715-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01715-5