Abstract

In mitigating and adapting to climate change-related risks, unbiased risk assessments are essential. Yet individuals systematically rate their personal risks as lower than those of others, believing themselves to be less at risk than others (that is, a self–other discrepancy). In a preregistered multi-level meta-analysis, we estimate the overall effect and boundary conditions for a self–other discrepancy in climate change-related risk perceptions. The synthesis incorporated 60 datasets, comprising 83 effect sizes from 70,337 participants across 17 countries. Results revealed that in 81 of 83 datasets, participants perceived their personal climate change-related risks as lower than others (d = −0.54, 95% CI [−0.68, −0.39]). This skewness was robust across specific extreme weather-related hazards and general climate change-related risks. Notably, the self–other discrepancy was less pronounced when comparisons involved specific others (for example, neighbours) or high-risk regions (for example, Asia), and more pronounced when the referents were compatriots or humanity as a whole or when the context was low-risk regions (for example, Europe). These results highlight a critical implication for the general public and a challenge for risk communicators: a widespread misperception, where people perceive personal climate change-related risks as lower than others, may hinder public engagement in mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Climate change-related risks are intensifying, driven in part by increasingly frequent and severe extreme weather events. Heatwaves, storms, droughts and floods bring widespread destruction and disruption1. In adapting to and mitigating these risks, unbiased public risk perceptions are essential2,3,4,5. Although risk perceptions depend on individual traits and the nature of hazards, judgements about risks are often shaped by decision-making heuristics6,7. To conserve cognitive resources, people may evaluate risk comparatively, assessing their personal risk relative to the risk of others. Comparative risk perceptions tend to be skewed, with personal risks perceived as lower than those of others8,9,10. In this meta-analysis, we set out to estimate the extent and boundary conditions of such skewness (that is, self–other discrepancy) in climate change-related risk perceptions. It is important to note, however, that we are synthesizing discrepancies at the study level, without an objective standard to establish that risk perceptions are overly optimistic11.

Risk perceptions refer to an individual’s evaluation of the severity and/or likelihood of a hazard affecting themselves or others. These judgements are prone to various biases12. Most people perceive risks to be less likely and less severe for themselves than for others13,14. Such self–other discrepancies can impede risk-preventive actions, such as quitting smoking15, getting vaccinated16 and mitigating climate change17. From a practical standpoint, skewed climate change-related risk perceptions may lead individuals to underestimate their own vulnerability, thereby undermining effective risk communication18.

Various self-serving biases cause people to hold overly favourable beliefs about their own outcomes and abilities compared with others8,13,19,20,21,22. The umbrella term ‘overoptimism’ encompasses three biases: overestimation of absolute abilities, overconfidence implying unrealistic precision and overplacement, which skews judgements towards being ‘better-than-average’ or underestimating their comparative risks23,24,25. We provide a meta-analytic estimate reflecting overplacement in climate change-related risk by synthesizing evidence of skewness in relative risk perceptions.

Three cognitive process models seek to explain this bias. First, the egocentrism model, which proposes a self-centred bias, suggests that overplacement results from overemphasizing personal characteristics as compared with an average ‘other’26. This leads people to exaggerate their own capabilities in handling or avoiding risks, such as climate change-related weather events. Second, the focalism model suggests that overplacement occurs from overemphasizing the characteristics of the focal object20. When the self is focal, personal risk resilience may be overemphasized. Finally, the generalized group account proposes that overplacement occurs because people view individuated referents more favourably than generalized referents20. In this view, self–other discrepancies are positively related to the generality of the referent.

In this meta-analysis, primary studies do not control for participants’ or others’ objective risks, so we cannot determine whether perceptions are overly optimistic at the individual level. Here self–other discrepancy refers to a form of overplacement in which participants’ average risk perceptions are lower than their perceptions of the average risk of others11,20.

Hypotheses and primary data

Hypothesis 1

Personal climate change-related risks will be perceived as less likely and/or severe than others’ risks.

According to the generalized group account, self-serving biases will be more pronounced when individuals compare themselves with a generalized other rather than a specific other27,28. This boundary condition may arise from selective comparison, where individuals conjure a high-risk stereotype when allowed to compare themselves with a large pool of referents28,29. Accordingly, we hypothesize that personal risk perceptions will be less skewed when comparing with specific referents (for example, neighbours) rather than general referents (for example, compatriots or humanity).

Hypothesis 2

Climate change-related risk perceptions will be less skewed when individuals compare themselves with specific referents rather than with general referents.

Risk perceptions have been proposed to be less skewed when people face objective risks30,31. Because people in some world regions face objectively higher climate change-related risk than others, we expect people living in these regions to exhibit smaller self–other discrepancies than those in countries facing lower levels of climate change-related risks. The key climate change-related risks, as identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports1, are especially prominent in regions with low-income populations and low-lying coastal systems. In adapting to climate change-related risks, maladaptation is most frequent in the Global South. From the period 1993 to 2022, countries in Asia such as China and the Philippines have been disproportionally affected by climate change-related extreme weather events32. To examine the effect of such objective risk, we partitioned the dataset into three world regions: Asia and Oceania, assessed as having the highest objective risk; USA, assessed as having medium risk; and Europe, assessed as having the lowest risk among the three.

Hypothesis 3

Samples from world regions with a relatively higher level of objective climate change-related risk will exhibit a smaller self–other discrepancy than samples from regions with a relatively lower level of objective climate change-related risk.

Primary studies

We synthesized 59 datasets from 2010 to 2023, comprising 83 effect sizes. Sample sizes ranged from 18 to 4,246, with a total sample size of 70,337 participants, most sampled by non-random procedures. The sample covers 17 countries, representing North America (k = 30), Europe (k = 11), Asia (k = 12) and Oceania (k = 4). All primary studies used survey methods to assess perceived climate change-related risks for both participants themselves and other humans who are currently living (that is, not future generations). The majority of studies employed indirect methods, using two identical items apart from targeting personal or others’ risk (Supplementary Data, Supplementary Material 5).

Results

A multi-level meta-analysis confirmed Hypothesis 1, revealing that personal risks were rated as lower than the risks of others (d = −0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) [−0.68, −0.39]). This overall effect implies that in more than 68% of the cases, climate change-related risks are perceived as both less likely and less severe for oneself than for others. Skewed comparative risk perceptions were observed in 81 of the 83 effect sizes. In assessing dispersion, a Q test showed that the overall effect was significantly heterogeneous (Q = 153, d.f.(82), P < 0.001), implying that the true effect size varies across samples. Furthermore, the relative heterogeneity was approximately 49% at the between-study level (I2 = 48.8) but close to zero at the within-study level (I2 < 0.01). In assessing the absolute dispersion of the overall effect, prediction intervals were overlapping zero (95% PI [−1.31, 0.24]; Fig. 1), meaning that when predicting the effect in a specific future study, the self–other discrepancy might be reversed. Taken together, the size of the overall effect is noteworthy in the light of typical meta-analytic effects within the social sciences (for example, ref. 33). Nevertheless, the overall effect was substantially dispersed, calling for subgroup analyses, as predicted by Hypotheses 2 and 3. Before testing these hypotheses, a meta-regression showed that the overall effect was statistically significant for both general climate change-related risks (d = −0.59, 95% CI [−0.75, −0.43]) and specific extreme weather-related events (d = −0.33, 95% CI [−0.64, −0.18]), with no statistically significant moderation (QM = 2.1, d.f.(2), P = 0.14). In assessing dispersion, the model was still significantly heterogeneous (Q = 136.7, d.f.(80), P < 0.001), implying that the true effect size varies across samples. Furthermore, the relative heterogeneity was approximately 47% on the between-study level (I2 = 46.9) but close to zero on the within-study level (I2 < 0.01).

In 81 of 83 effect sizes, personal risks were rated as lower than those of others, resulting in an overall self–other discrepancy (d = −0.54, 95% CI [−0.68, −0.39]). Diamond represents the overall effect size and CI; whiskers represent the prediction interval, where 0 implies that personal climate change-related risks are perceived to be equal to the risk of others.

To test Hypothesis 2, we conducted a multi-level linear meta-regression testing whether the overall effect is moderated by the referent, categorized as three subgroups: (0) close others (for example, people in your community), (1) compatriots (for example, people in participants’ country) and (2) humanity (for example, all people). Both the estimate for the model intercept (d = −0.26, 95% CI [−0.46, −0.07]) and the estimate for the moderation of referent (d = −0.23, 95% CI [−0.35, −0.11]) were statistically significant, as the omnibus test of the moderation (QM = 14.3, d.f.(1), P < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Adding a referent reduced dispersion, although the effect remained significantly heterogeneous (Q = 111.1, d.f.(80), P < 0.001). The relative heterogeneity at the between-study level was also decreased by approximately 10 percentage points compared with the main analysis (I2 = 39.1). The within-study level of heterogeneity was close to zero (I2 < 0.01). The prediction interval for the moderation still overlapped zero (95% PI [−1.02, 0.53]. This suggests that when predicting a future observation, now taking the referent into account, the self–other discrepancy could still be reversed for that specific observation. However, when estimating the population parameter, we obtained a statistically significant moderation, indicating that the point estimates differ across referents.

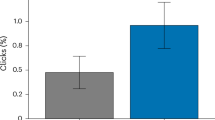

The self–other discrepancy was least skewed when comparing with close others (d = −0.28, 95% CI [−0.50, −0.07]), more skewed when comparing with compatriots (d = −0.47, 95% CI [−0.65, −0.26]) and especially skewed when comparing with humanity (d = −0.72, 95% CI [−0.88, −0.56]; Fig. 2). Taken together, these results confirm Hypothesis 2 by suggesting that climate change-related risk perceptions were less skewed when individuals compared themselves with specific referents rather than with general referents.

Although personal risk perceptions were lower than perceptions of the risk of others in all cases, this skewness became less pronounced when people compared themselves with close others rather than with general others. Bold lines represent the point estimate standard error, and whiskers the 95% prediction interval.

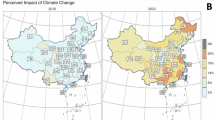

Last, we test Hypothesis 3, which states that as objective risks increase, self–other discrepancies will decrease. Climate change-related risks vary by region—Asia and Oceania face high objective risks, the USA faces medium risk, and Europe faces the lowest risks of the three. Testing Hypothesis 3, we ran a meta-regression using referent, centred at humanity (for example, all people), as well as the region as moderators. When controlling for region in the model, the linear effect for the referent was significant (d = −0.18, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.07]). When investigating the self–other discrepancy, the effect was significant in all regions. Confirming Hypothesis 3, risk perceptions were least skewed in the high-risk region (Asia/Oceania: d = −0.42, 95% CI [−0.65, −0.19]), followed by the medium-risk region (USA: d = −0.65, 95% CI [−0.84, −0.45]), and most skewed when objective risks were lowest (Europe: d = −1.20, 95% CI [−1.45, −0.92]; Fig. 3). The omnibus test of moderation was significant for the model with both moderators (QM = 42, d.f.(3), P < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference between the medium-risk and high-risk regions (z = 1.70, P = 0.09). In assessing dispersion, for the model including both referent and objective risk, data were no longer significantly heterogeneous (Q = 71, d.f.(79), P = 0.69), indicating improved precision. Furthermore, the relative heterogeneity was further reduced to approximately 24% on the between-study level (I2 = 24.0) and close to zero on the within-study level (I2 < 0.01). Taken together, these results show that both the referent (Hypothesis 2) and objective risk (Hypothesis 3) together explained a noteworthy amount of the dispersion in the self–other discrepancy. When risks were objectively low, prediction intervals did not overlap zero for either of the referents, while it overlapped zero for all referents when objective risks were high (Supplementary Data, Supplementary Material 9).

Discussion

From a multi-level meta-analysis, comprising 83 effect sizes from 70,337 participants across 17 countries, we draw four key conclusions regarding climate change-related risk perceptions. First, comparative risk perceptions were robustly skewed, with individuals rating their personal risks as lower than those of others (that is, self–other discrepancy) in 81 of 83 effect sizes. Second, this skewness was consistent across both specific extreme weather-related risks and general climate change-related risks, with no significant difference between the two. Third, the self–other discrepancy was less pronounced when comparing with a specific other (that is, neighbours or city) rather than with a general other (that is, humanity or country). Finally, the self–other discrepancy was further reduced under high levels of climate change-related risks (that is, Asian sample) compared with under lower levels of risk (that is, European sample).

This meta-analysis examines items assessing self–other risk comparisons, which primary studies aggregated into a single index variable representing overall risk perception. As a result, these measures have rarely, if ever, been reported separately to examine discrepancies in self–other judgements. Because the specific items used to estimate the self–other discrepancy in this meta-analysis were not the focus in the primary studies, the risk of publication bias is probably minimal. Supporting this, both P-curve analysis and robust Bayesian meta-analysis (RoBMA) revealed no evidence for publication bias (Methods). Minimizing the risk of publication bias is a central aspect of any meta-analysis, particularly in the light of ref. 33, who reported that the average effect in psychological research was reduced from d = 0.37 to d = 0.26 when correcting for publication bias. By contrast, we obtained a noteworthy overall effect (d = −0.54), highlighting the importance of self–other discrepancies in climate change-related risk perceptions.

These results might be challenged by suggesting that people are comparing their personal risks with the risks of any person in a particular group (the ‘cumulative risk’ explanation). If this explanation is true, the effect should decrease or even disappear if people compare their own risk with the risk of one other referent selected at random. Among the included primary studies, one study aimed to control for this by asking participants to rate their personal risk compared with the risk of ‘a random person in your city’ and the risk of ‘a random person in your country’ (Skipor & M.B., unpublished data). Results did not support the cumulative risk explanation as risk perceptions about a random other also displayed self–other discrepancies (that is, d = 0.32 and d = 1.0, respectively).

The meta-analysis confirmed that risk perceptions were more strongly misaligned when individuals compared themselves with general others rather than with specific others. This intriguing finding also highlights a limitation of the present study—that risk perception was assessed without controlling for all measures of objective risks. The subgroup-analysis comparing different world regions partially accounts for objective risk as climate change has historically affected, and is indeed projected to affect, different parts of the world to different extents1,32. In line with the proposed moderating effect of objective risk, we found that the samples from Asia and Oceania exhibited a smaller self–other discrepancy than the samples from the USA and Europe. We note, however, that within-group heterogeneity remained relatively large in all subgroups, suggesting that additional predictors may explain variance that was not captured in this meta-analysis, such as temporal closeness to extreme weather events.

Results align with the generalized group account, suggesting individuals may selectively compare their own risks with high-risk referents, those in areas with objectively higher risks. This implies that self–other discrepancies may arise not only from self-focused bias but also from biased referent selection10,13.

In examining comparative risk perceptions between general climate change-related risks and specific extreme weather risks, we found no statistically significant differences although one might expect the perceived probability of climate change risks to be higher. The non-significant findings provide important insight into the idea that probability may reduce the perceived impact or likelihood of risks, as proposed by ref. 10. As no significant difference could be detected, our meta-analysis suggests that this effect may not always occur.

Analysing both climate change-related and extreme weather-related risks could be viewed as a potential threat to construct validity. Although extreme weather events are increasing due to climate change1 and methods for estimating the relative contribution of anthropogenic climate change to specific extreme weather events are improving34,35, psychological factors still influence the extent to which people attribute these events to anthropogenic climate change36. Integrating climate change with extreme weather risks validates the robustness of our findings, as similar effects were observed across both types of risks. We encourage future research to investigate self–other discrepancies across diverse climate-related risks, such as extreme weather, water scarcity, food security and health.

Heterogeneity across studies was substantial in the overall effect, indicating that variability could not be attributed to sampling error alone. Subgroup analyses reduced a substantial portion of this heterogeneity by taking both the general/specific nature of the referents and the regional levels of climate change-related risks into account. It is important to note, however, that the primary goal of this meta-analysis was not to explain as much variance as possible but rather to quantify the meta-analytic overall effect of self–other discrepancy in climate change-related risk perceptions.

In this meta-analysis, two effect sizes out of 83 showed a reversed effect37,38. Such cases could reveal important boundary conditions. First, in both studies, participants were asked to indicate the level of agreement with being at greater risk than others. These items deviate from all other studies, where participants were asked to assess their risk compared with others without implying that their risk is higher or lower. Although framing a message as losses or gains is known to influence emotions39, it seems unlikely that such large deviations could result from framing alone. Second, Peng et al.37 targeted farmers who all live in areas highly prone to extreme weather events, and as those who work the land for a living, they are likely to have firsthand experience of the risks involved, which has been demonstrated to reverse judgements from being unrealistically optimistic into being ‘unrealistically pessimistic’30,31.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates a robust self–other discrepancy in climate change-related risk perceptions. The magnitude of discrepancy is positively related to referent generality and negatively related to objective risk. We encourage future research to investigate how selection bias and risk exposure may moderate self–other discrepancies in climate change-related risk perceptions.

Limitations

This meta-analysis is limited in scope. As stated in the eligibility criteria, we assessed general and specific risks, where specific risks include various extreme weather-related hazards. It should be noted that there are numerous other specific climate change-related risks. In this meta-analysis, we restricted the scope to focus on extreme weather events. Furthermore, we chose to include studies measuring the risk for ‘you and your family’ in the personal risk category. From a construct validity perspective, this approach may introduce some measurement noise. We made a decision to include these studies as we considered them sufficiently valid while also increasing the statistical power of our meta-analysis.

Future research

Risk perceptions can be skewed on two levels. First, absolute risks can be biased at the individual level or the group level by underestimating the true personal risk or the relative personal risk (that is, falsely perceiving personal risks as lower than the group average). Second, comparative risk can also be biased on the individual or the group level—falsely perceiving personal risks as lower than average when in fact being on average for that person, or that most people’s risk perceptions are below the group average40. Following the eligibility criteria, the majority of primary studies included in the meta-analysis assess absolute risks on the group level (Supplementary Data, Supplementary Material 5). We encourage future research to assess other types of self–other discrepancies related to climate change.

Unrealistic optimism has been criticized for being a statistical artefact11. This critique is valid given the assumption that people possess perfect information. The current work is not concerned primarily with such descriptive accuracy in decision-making under certainty (that is, if risk perceptions match reality), it concerns how people perceive risks under uncertainty. Claiming that some people’s risk perceptions are accurate because they were (not) affected by climate change, while others were affected, is a statement about descriptive accuracy. However, the current results, showing that personal risks are perceived as lower than the risk for others, might have been guided by more information than the pure baselines. We therefore encourage future research to assess climate change-related risks under both certainty and uncertainty.

Past research has examined overplacement using indirect methods, where participants rate the risk or abilities of themselves and others in separate items, and direct methods, where the comparison between the two is assessed with the same item. Within the indirect method, participants may employ either the forced-choice approach, which asks whether they are above or below the average, or the percentile method, which asks participants to place themselves in percentiles relative to the average20. Among the primary studies, 74 used the indirect method and 6 used the direct method. Neither the forced-choice nor the percentile methods were employed in any of the included studies. Importantly, the meta-analysis of ref. 20 on the better-than-average effect reports that the overall effect sizes range from d = 0.62 to d = 1.0 across these methods. We encourage future research to assess whether comparative climate change-related risks can be reduced using the forced-choice or percentile method. In addition, we encourage employing experimental paradigms41,42,43 to further investigate comparative climate change-related risk perceptions.

Finally, we encourage future research to assess comparative climate change-related risk perceptions among specific risks such as renewable energy sources (for example, solar and wind power) and climate change mitigation technologies (for example, carbon capture and storage).

Practical implications

The goal of risk communication is to present information about potential hazards in ways that support informed decision-making, promote protective behaviours and minimize harm. Key challenges include effectively communicating the nature of risks, their probabilities and the emotions they evoke7,18. Cognitive biases, such as optimism bias, often distort risk perception6. Addressing these biases requires understanding their origins and applying corrective measures, such as including baseline risks alongside relative risks to enhance comprehension44.

In the case of comparative climate change-related risk perceptions, we found that individuals perceive risks as more likely and/or severe for others than for themselves, which could hinder risk-preventive actions15,16,17. By analysing this skewness across different referents, we observed that risk perceptions are less skewed when comparisons involve specific others rather than general others. Practically, these findings suggest that framing risk communication by referencing general others may foster skewed risk perceptions. We recommend using specific referents to reduce skewness, helping individuals make better-informed decisions about mitigating and adapting to climate change-related risks.

Methods

Meta-analytic aim

This meta-analysis synthesized survey-based research assessing perceptions of climate change-related risks for oneself and for others, using either direct (single-item) or indirect (separate items) measures. For each study, we recorded the specificity of the referent (general versus specific) and the participants’ country. In addition to testing the overall effect, this information allowed us to test whether referent specificity and objective climate change risk moderated the self–other discrepancy. This meta-analysis was preregistered and conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to assure maximum transparency and reproducibility45.

Eligibility criteria

-

(1)

The record must provide unique and original survey data. Hence, studies based on reused data from either a common data pool or past studies were excluded.

-

(2)

Data must be collected without or before any experimental intervention. Data based on a research design assessing risk perceptions between experimental conditions were excluded.

-

(3)

Participants must gauge the same future climate change risks for themselves as for the referent. Studies assessing different risk measures or different risk objects for the participant and the referent were excluded. For studies using multiple measures of risk (for example, probability, severity and/or a general risk assessment), we chose to include the item measuring probability.

-

(4)

The risk object must be either non-specific or specific climate change-related extreme weather risk. We included the non-specified climate risks ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’. The specific risks include, but are not limited to, ‘heatwaves’, ‘flooding’, ‘wildfire’, ‘droughts’, ‘tropical cyclones’, and ‘heavy precipitation’.

-

(5)

The risk participants must include at least one from each category: themselves = ‘you’ or ‘household’ or ‘you and your family’ or ‘your family’ or ‘you and your household’ or ‘your household’ or ‘me’ or ‘me and my family’ or ‘my family’ or ‘me and my household’ or ‘my household’, not ‘family’ or ‘relatives’ or ‘parents’. Other now-living people = ‘family’ or ‘relatives’ or ‘parents’ or ‘children’ or ‘people in my neighbourhood/town/city/state/country/world’ or ‘humanity’, not ‘society’ or ‘the environment’ or ‘plants and animals’ or ‘future generations’.

-

(6)

All articles must be written in English.

Search strategy

The search strategy included four parts: (1) searching the SCOPUS database for published scientific records, (2) screening studies included in the recent review by van Valkengoed et al.45, (3) searching citations of six key references (refs. 4,5,46,47,48,49), (4) searching for unpublished data by posting a call on the ‘Environmental Psychology Mailing List’. We chose to use a set of key references instead of multiple databases because key references let us find records that search engines do not pick up. Examples of these are national surveys and other data that are not traditionally published in peer-reviewed journals. The search process was initiated on 26 February 2024, meaning that no records published after this date have been included.

Reference 49 was chosen because it is one of the first and most cited articles that has a scale that is eligible for the meta-analysis. Reference 48 is one of the key articles on experiencing extreme weather events. References 4,5,47 are widely cited articles examining climate change-related risk perceptions, climate change adaptation and experiences of extreme weather events. Reference 46 was chosen because it provides an updated review, including national surveys and databases, hence complementing the search in SCOPUS.

Because studies on risk perceptions attract broad and interdisciplinary research, we restricted the search string to the fields using research methods eligible for the current meta-analysis. More specifically, we included environmental science, earth and planetary sciences, social sciences, economics, econometrics and finance, decision sciences, psychology, multidisciplinary, and neuroscience. The final number of records (excluding duplicates) to screen was 7,546.

Screening process

Results from the literature search were uploaded to Rayyan and duplicates were removed (https://www.rayyan.ai). After screening the 7,546 abstracts, we retrieved the full texts of the remaining 1,954 records to be considered. After screening all full-text records, 50 articles remained containing 60 independent samples with a total of 83 effect sizes. Finally, a PRISMA flow chart was constructed to aid readers in visually assessing our process as well as to assure a greater level of reproducibility45.

In validating the coding manual, two independent reviewers screened 5% of the full texts. Results showed insufficient intercoder reliability (K = 0.121). Therefore, we revised the coding manual and recruited a second independent coder who also reviewed 5% of the full-text articles. The revised coding manual resulted in acceptable intercoder reliability (K = 0.846). A single coder finalized the screening of the full-text articles according to the eligibility criteria. Both versions of the coding manual can be found on OSF (Open Science Framework; Supplementary Information, Supplementary Material 4). Details are in the PRISMA flow chart (Supplementary Fig. 1). For a more in-depth account of the workflow behind this meta-analysis and zip files containing all excluded articles sorted by reason for exclusion, see Supplementary Information, Supplementary Materials 2, 3 and 8.

Data extraction

After screening the full-text records, we extracted data from those eligible. The data were extracted into a coding protocol including the following information: title, author(s), year of publication, country, risk object(s) (that is, flood, global warming and so on), risk participant(s) (that is, you, you and your family and so on), referent(s) (that is, people in your town/country, humanity and so on), means and standard deviations, effect size(s) (in d), standard error of d, population, sample technique, sample size, method of comparison (direct/indirect), items used from the study (number), items used from the study (text), and question(s) from which items are taken. The protocol is available in the Supplementary Data, Supplementary Material 5. In the following cases, we calculated the effect size by averaging outcome measures: ‘how big of a risk’ and ‘to what extent’50, ‘disease’ and ‘standard of living’49,51,52,53, and ‘likelihood’ and ‘severity’ (Skipor & van Valkengoed, unpublished data).

Sample characteristics

The final sample included 60 datasets collected between 2010 and 2023, yielding 83 effect sizes. Individual study sample sizes ranged from 18 to 4,246, with a combined total of 70,337 participants, most recruited through non-random procedures. The studies covered 17 countries, including North America (k = 30), Europe (k = 11), Asia (k = 12) and Oceania (k = 4).

All primary studies used survey methods to assess perceived climate change-related risks for both participants themselves and other humans currently living. The majority of studies surveyed general population samples; eight focused on students, and a smaller number targeted specific groups such as farmers, landowners, homeowners and adolescents. In assessing personal risks, nearly all studies used the referent ‘you’ or ‘you personally’, with the exception of ten studies that included both the self and family. For referents representing compatriots, most studies used the phrase ‘people in (participants’ country)’ whereas for referents representing humanity, the most common terms were ‘humanity’ or ‘people in developing countries.’ Regarding the risk object, most studies framed it as ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’ while a smaller subset focused on climate change-related weather events. For additional details on study-level characteristics, see Supplementary Data, Supplementary Material 5.

Publication bias assessment

We assessed publication bias both for the overall meta-analytic effect and for each of the three referents. As a first means to assess indications of publication bias, Egger’s test revealed an asymmetry funnel plot (Z = 10.18, P < 0.001). Removing one outlier (+9.1 s.d.) did not alter the funnel plot asymmetry (Z = 10.79, P < 0.001; Extended Data Fig. 1). Because Egger’s test assesses the small-sample effect, which could be indicative yet is not a direct test of publication bias, we conducted a P-curve analysis. Results showed a significantly right skewed distribution of P values, as expected in the absence of P hacking (Z = 50.25, P < 0.001; Extended Data Fig. 1). That lack of evidence for publication bias is not surprising given that the majority of primary research included in the meta-analysis did not report analyses of comparative risk perception. Hence the authors of the primary studies seem to have no incentives to engage in P hacking. Complementing these tests of the small-study effect and publication bias, respectively, we ran a RoBMA. More specifically, we ran RoBMA-PP, focusing on the precision effective test–precision effective estimate of standard error (PET–PEESE) as selection models are redundant under the assumption that P hacking was not prevalent. The analysis included 12 models: 2 (effect: present versus absent) × 2 (heterogeneity: present versus absent) × 3 (publication bias: none versus PET versus PEESE). Moreover, as the overall meta-analytic estimate was dependent on the referent, we ran the RoBMA-PP for each referent. For referent 1, we obtained overall weak support for the presence of an effect (BF10 = 1.83), extreme support for heterogeneity (BF10 > 100) and non-informative support for the presence of publication bias (BF10 = 1.02). Furthermore, data were best described by model 10 assuming the presence of an effect and heterogeneity, and the absence of publication bias (BF10 = 4.19, d = 0.29, 95% credibility interval [0.07, 0.50]). For referent 2, we obtained overall extreme support for the presence of an effect (BF10 > 100) and for heterogeneity (BF10 > 100), and very weak support for the presence of publication bias (BF10 = 1.82). Furthermore, data were best described by model 11 assuming the presence of an effect and heterogeneity, and the PET model (BF10 = 11.54, d = 0.39, 95% credibility interval [0.29, 0.47]). For referent 3, we obtained overall extreme support for the presence of an effect (BF10 > 100) and for heterogeneity (BF10 > 100), and very weak support for the absence of publication bias (BF01 = 1.47). Furthermore, data were best described by model 10 assuming the presence of an effect and heterogeneity, and the absence of publication bias (BF10 = 10.23, d = 0.64, 95% credibility interval [0.48, 0.76]). Taken together, the publication bias assessments seem to provide more support for the absence than for the presence of small-study effects and P hacking.

Data analysis

All analyses were carried out using R 4.4.2. Specific packages and R syntax can be found in Supplementary Material 10 on OSF (https://osf.io/m3qbn; S10_RProject.zip). Due to the nested structure of the data, the studies contributed to more than one risk estimate, the analysis was nested within the study in a multi-level meta-analysis. To control for the correlation between the risk estimates, a correlation of rho = 0.5 was used.

Ethical considerations and data availability

Meta-analyses are usually exempt from ethics approval since they do not collect any new data. When going through public material such as published articles, neither confidentiality nor consent is a problem. For a meta-analysis to be ethically conducted, there is a different set of issues that must be tackled. A meta-analysis should be properly documented and transparent in its approach to ensure that key information has not been left out or that the data have not been manipulated by malicious actors. Furthermore, the results ought to be clearly reported and sufficiently scrutinized by testing for publication bias54. Given this, several steps have been taken to ensure the transparency and rigour that a meta-analysis requires. First, the entire process from preregistration to extracted data has been meticulously documented and is publicly available at OSF so that anyone can see it (Supplementary Information, Supplementary Material 1). Second, strict eligibility criteria have been adhered to and tested by having an independent reviewer screen a subset of full-text articles. Third, APA guidelines are followed throughout the paper, making it simple to follow. Finally, the results have been analysed for publication bias, and all included studies have been properly accredited in the references.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data are publicly available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/4wj7m/).

Code availability

The R script is publicly available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/4wj7m/).

References

IPCC Climate Change 2023 (eds Core Writing Team et al.) (IPCC, 2023); https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647

Bergquist, M., Nilsson, A., Harring, N. & Jagers, S. C. Meta-analyses of fifteen determinants of public opinion about climate change taxes and laws. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 235–240 (2022).

Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M. T., Rosenthal, S. A. & Leiserowitz, A. Identifying the most important predictors of support for climate policy in the United States. Behav. Public Policy 5, 480–502 (2020).

van Valkengoed, A. M. & Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 158–163 (2019).

van der Linden, S. The social–psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 41, 112–124 (2015).

Siegrist, M. & Árvai, J. Risk perception: reflections on 40 years of research. Risk Anal. 40, 2191–2206 (2020).

Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E. & MacGregor, D. G. in The Feeling of Risk (ed. Slovic, P.) 21–36 (Routledge, 2013).

Dunning, D., Heath, C. & Suls, J. Flawed self-assessment. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 5, 69–106 (2004).

Hsee, C. K. & Weber, E. U. A fundamental prediction error: self–others discrepancies in risk preference. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 126, 45–53 (1997).

Weinstein, N. D. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science 246, 1232–1233 (1989).

Harris, A. J. L. & Hahn, U. Unrealistic optimism about future life events: a cautionary note. Psychol. Rev. 118, 135–154 (2011).

Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 236, 280–285 (1987).

Sharot, T. The optimism bias. Curr. Biol. 21, R941–R945 (2011).

Sjöberg, L. The different dynamics of personal and general risk. Risk Manage. 5, 19–34 (2003).

Weinstein, N. D., Marcus, S. E. & Moser, R. P. Smokers’ unrealistic optimism about their risk. Tob. Control 14, 55–59 (2005).

Dryhurst, S. et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 23, 994–1006 (2020).

Bergquist, M. Most people think they are more pro-environmental than others: a demonstration of the better-than-average effect in perceived pro-environmental behavioral engagement. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 42, 50–61 (2020).

Rakow, T., Heard, C. L. & Newell, B. R. Meeting three challenges in risk communication: phenomena, numbers, and emotions. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2, 147–156 (2015).

Weinstein, N. D., Grubb, P. D. & Vautier, J. S. Increasing automobile seat belt use: an intervention emphasizing risk susceptibility. J. Appl. Psychol. 71, 285–290 (1986).

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C. & Alicke, M. D. The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 118–149 (2019).

Moore, D. A. When good = better than average. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2, 277–291 (2007).

Korbmacher, M., Kwan, C. & Feldman, G. Both better and worse than others depending on difficulty: replication and extensions of Kruger’s (1999) above and below average effects. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 17, 449–486 (2022).

Kruger, J. & Dunning, D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 77, 1121–1134 (1999).

Moore, D. A. & Healy, P. J. The trouble with overconfidence. Psychol. Rev. 115, 502–517 (2008).

Sanchez, C. & Dunning, D. Overconfidence among beginners: is a little learning a dangerous thing? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 114, 10–28 (2018).

Moore, D. A. & Small, D. A. Error and bias in comparative judgment: on being both better and worse than we think we are. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 92, 972–989 (2007).

Alicke, M. D., Klotz, M. L., Breitenbecher, D. L., Yurak, T. J. & Vredenburg, D. S. Personal contact, individuation, and the better-than-average effect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 68, 804–825 (1995).

Perloff, L. S. & Fetzer, B. K. Self–other judgments and perceived vulnerability to victimization. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 50, 502–510 (1986).

Diel, K. & Friese, M. Morally charged: why people prefer to compare themselves with others who are less environmentally friendly than themselves. J. Environ. Psychol. 96, 102318 (2024).

Burger, J. M. & Palmer, M. L. Changes in and generalization of unrealistic optimism following experiences with stressful events: reactions to the 1989 California earthquake. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 18, 39–43 (1992).

Weinstein, N. D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 39, 806–820 (1980).

Adil, L., Eckstein, D., Kuenzel, V. & Schaefer, L. Climate Risk Index 2025—Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? (Germanwatch, 2025); https://www.germanwatch.org/en/node/93013

Bartoš, F. et al. Footprint of publication selection bias on meta-analyses in medicine, environmental sciences, psychology, and economics. Res. Synth. Methods 15, 500–511 (2024).

Otto, F. E. Attribution of weather and climate events. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 42, 627–646 (2017).

Otto, F. E. Attribution of extreme events to climate change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 48, 813–828 (2023).

Ogunbode, C. A., Demski, C., Capstick, S. B. & Sposato, R. G. Attribution matters: revisiting the link between extreme weather experience and climate change mitigation responses. Glob. Environ. Change 54, 31–39 (2019).

Peng, L., Tan, J., Lin, L. & Xu, D. Understanding sustainable disaster mitigation of stakeholder engagement: risk perception, trust in public institutions, and disaster insurance. Sustain. Dev. 27, 885–897 (2019).

You, M. & Ju, Y. Comparing outrage effect on the risk perception of climate change versus fine dust. Health Commun. 35, 1678–1685 (2019).

Nabi, R. L. et al. Can emotions capture the elusive gain–loss framing effect? A meta-analysis. Commun. Res. 47, 1107–1130 (2020).

Shepperd, J. A., Klein, W. M., Waters, E. A. & Weinstein, N. D. Taking stock of unrealistic optimism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 395–411 (2013).

Burton, J. W., Harris, A. J., Shah, P. & Hahn, U. Optimism where there is none: asymmetric belief updating observed with valence-neutral life events. Cognition 218, 104939 (2022).

Garrett, N. & Sharot, T. Optimistic update bias holds firm: three tests of robustness following Shah et al. Conscious. Cogn. 50, 12–22 (2017).

Garrett, N. & Sharot, T. There is no belief update bias for neutral events: failure to replicate Burton et al. (2022). J. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 876–886 (2023).

Gigerenzer, G., Wegwarth, O. & Feufel, M. Misleading communication of risk. BMJ 341, c4830 (2010).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 (2021).

van Valkengoed, L., Steg, L. & Perlaviciute, G. The psychological distance of climate change is overestimated. One Earth 6, 362–391 (2023).

Whitmarsh, L. Are flood victims more concerned about climate change than other people? The role of direct experience in risk perception and behavioural response. J. Risk Res. 11, 351–374 (2008).

Spence, A., Poortinga, W. & Pidgeon, N. F. The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Anal. 32, 957–972 (2011).

Leiserowitz, A. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: the role of affect, imagery, and values. Climatic Change 77, 45–72 (2006).

Karlsson, H., Asutay, E. & Västfjäll, D. A causal link between mental imagery and affect-laden perception of climate change related risks. Sci. Rep. 13, 10081 (2023).

Wang, C., Geng, L. & Rodríguez-Casallas, J. D. How and when higher climate change risk perception promotes less climate change inaction. J. Clean. Prod. 321, 128952 (2021).

Yang, J. Z., Kahlor, L. A. & Griffin, D. J. I share, therefore I am: a US–China comparison of college students’ motivations to share information about climate change. Hum. Commun. Res. 40, 112–135 (2014).

Zobeidi, T., Yazdanpanah, M. & Bakhshi, A. Climate change risk perception among agriculture students: the role of knowledge, environmental attitude, and belief in happening. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 22, 43–55 (2020).

Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Vol. 2 (Sage, 2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors who made this meta-analysis possible by providing raw data or summarizing their data. We thank R. Pourasgari for assisting in double coding material, K. Ask for valuable comments on the paper and L. Effenberg for work on data administration. This research was funded by FORMAS grant number 2022-01871, received by M.B.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gothenburg. This research was funded by FORMAS 2022-01871 awarded to M.B.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project administration: M.B. Research idea: M.B., P.B. and I.S. Eligibility criteria: M.B. and I.S. Writing search terms: I.S. and M.B. Searching: I.S. and M.B. Screening: I.S. Data extraction: I.S. and M.B. Effect size calculation schedule: M.B. Calculating effect sizes: M.B. Flow chart: I.S. Organizing supplementary materials and uploading on OSF: I.S. Writing preregistration: I.S. and M.B. Meta-analytic model: P.B. Figures displaying meta-analytic results: P.B. and M.B. Egger’s test and RoBMA: M.B. P-curve analysis: I.S. Writing: M.B., P.B. and I.S. Revision: M.B., P.B. and I.S. Funding: M.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Heather Akin, Matto Mildenberger and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Assessing publication bias by funnel plot and P-curve analysis.

a) Funnel plot with effect size Cohen’s d on the X-axis and standard errors on the Y-axis after removing one outlier. b) p-curve analysis including lines for the observed p-curve, null of no effect, and null of 33% power.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Materials 1–4 and 8. Supplementary information for 1, preregistration; 2, search terms and searching; 3, screening; 4, coding manual; and 8, all excluded articles sorted by reason.

Supplementary Data 5–7 and 9

All extracted data, effect size calculations, data file for primary analyses and estimates for subgroups CI and PI.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sandlund, I., Bjälkebring, P. & Bergquist, M. Meta-analytical evidence of a self–other discrepancy in climate change-related risk perceptions. Nat Sustain (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01717-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01717-3