Abstract

Decentralized approaches to natural resource governance can promote conservation while reducing poverty in the Global South. However, the local benefits under decentralized governance are often unequal, reflecting extant social inequalities. There is a lack of rigorous evidence from national-scale studies showing how decentralization programmes affect inequality compared with what is observed in decentralization’s absence, and extant theory leads to competing hypotheses about such effects. We use data from a large-scale forestry-sector decentralization programme in Nepal during 2001–2011 to test general theories regarding the effects of such initiatives on inequality. We analyse census micro-data from two nationwide censuses, which we merge with administrative data on the implementation of decentralization and analyse through a two-way fixed-effects estimation approach. We find evidence suggesting that Nepal’s programme delivers significant poverty-alleviating benefits to the dominant ethnic and caste groups and comparatively smaller benefits to members of marginalized minority groups, resulting in apparent local increases in rural inequality associated with the programme. Thus, even relatively progressive programmes, such as Nepal’s, may lead to potential trade-offs between poverty alleviation, environmental conservation and inequality outcomes. Improved compliance with equity provisions may help to equalize effects, as could more substantial targeted benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Decentralized, community-based approaches to natural resource governance can improve environmental management while reducing rural poverty1,2. Programmes based on this logic have created natural resource user groups—local committees of resource users with management authority over common-pool resources—in communities across the Global South, and decentralization has long been one of the leading natural resource policy instruments2,3,4. Such governance approaches can alleviate poverty among rural households by expanding rights of access to the natural resources upon which they depend, creating new opportunities for resource-based livelihood activities and raising natural resource revenues that local user groups can invest in local development or pay back to programme participants in the form of cash benefits2.

Despite apparent successes, one of the key challenges facing decentralized natural resource governance approaches is that of inequality5,6,7,8, with relatively wealthy local households, male-headed households and households belonging to the dominant ethnic groups appearing to reap the most benefits under decentralization6,9. There is, however, a lack of rigorous evidence showing whether decentralized governance approaches make inequality better or worse compared with pre-existing policy arrangements. For example, past research suggests a 4.3% relative decrease in average rural poverty rates as a result of Nepal’s forestry decentralization programme1, which had enlisted a large share of the country’s households to manage more than one-third of the country’s forests by 202010. Understanding how this policy has impacted rural inequality, however, would require a theoretical and methodological approach that disaggregates the programme’s effects on poverty rates according to socially relevant sub-populations that map onto longstanding patterns of social and economic marginalization.

Through such an approach, our study estimates the impacts of Nepal’s forestry decentralization programme on local inequality in rural areas. We use this programme, which is seen as a model decentralization policy, to test competing theoretical expectations and investigate underlying causal mechanisms. Our work moves the current state of the knowledge forward on several fronts. First, while numerous studies—especially those employing qualitative methods—have described various inequalities that occur under decentralized forest management regimes without systematically comparing these outcomes to those that occur in the absence of decentralization (for example, refs. 6,11), this does not necessarily indicate how much better or worse inequality is under forestry decentralization as there are probably inequalities in the absence of decentralization as well. Second, other studies do make such comparisons with outcomes in the absence of decentralization, but employ dependent variables that do not capture the poverty differences between members of historically marginalized and advantaged social groups that are of primary interest in our study (for example, refs. 5,12). These bodies of research have been valuable for highlighting various inequalities related to forestry decentralization. Building upon this work, the current study uses large-scale, nationwide data from a country undergoing a forestry decentralization programme to measure poverty gaps between households belonging to marginalized and advantaged social groups, and to estimate the impact of decentralization on those poverty gaps by making comparisons with outcomes in the absence of decentralization. This analysis is timely in light of growing debates about potential interactions, trade-offs and synergies between the multiple environmental, economic and social outcomes from conservation policy instruments1,2,13 and sustainable development efforts14.

Decentralization can create both economic benefits and burdens for rural resource users, which in turn lead to changes in rural poverty. In the case of forestry decentralization, for example, the potential poverty-alleviating benefits of decentralization may include the expanded availability of subsistence forest products (such as firewood, fodder and wild foods) for rural users, owing to reforestation, and the aforementioned livelihood and cash benefits made available to rural households1,7. The economic burdens of decentralization for rural households may include new limits and fees on the collection of forest products, restrictions on the conversion of forests to agricultural land and the temporary closure of forests to promote regrowth1,7,9,15. While the impact of decentralization on average rural poverty rates, as estimated in previous studies1, depends upon the net impact of these various benefits and burdens for the average rural household, the effect of decentralization on inequality depends upon the heterogeneity of that net impact across different rural sub-populations.

Hypotheses

We test two competing hypotheses. First, we propose Hypothesis 1 (H1): decentralized resource governance alleviates inequality. There are theoretical reasons to expect that inequality may not be as severe under natural resource decentralization compared with the institutional arrangements that decentralization is implemented to replace in Global South countries—arrangements that are often characterized by informal domination by local elites through self-organized local institutions. Even where central governments have de jure property rights over natural resources, they are often unable to monitor and enforce them over large resources in rural areas, leading to de facto open access scenarios or governance through rules and norms that are self-organized locally16. Self-organized local institutions often reflect the preferences of traditionally dominant members of the community, and channel disproportionate benefits to those community members17,18.

The formal, externally imposed rules implemented under a decentralized resource governance programme may therefore reduce inequality by providing some constraints on the powers of the local dominant groups. Decentralized resource governance programmes may also encourage social inclusion and more equal benefit sharing through formal policy provisions targeting benefits toward, or encouraging the participation of, marginalized households7,19. The equity-focused provisions in the Nepalese programme, described below, are evidence of this. Local elites have little incentive to adopt such measures in the absence of policy mandates from above. Taken together, this suggests that more natural resource benefits may accrue to households belonging to marginalized groups under decentralization, compared with under the typical pre-decentralization scenarios.

Conversely, we propose the competing hypothesis 2 (H2): decentralized resource governance worsens inequality. There is reason to believe that the formal institutions and bureaucratic structures inherent to decentralized resource governance may merely empower members of dominant groups further6. This is because members of historically dominant social groups tend to be more literate, politically connected and advantaged when it comes to dealing with bureaucrats, and are often treated as ‘gatekeepers’ by government officials7,20,21. They are therefore better able to navigate the processes of natural resource decentralization programmes and to influence local rules. Where dominant groups can manipulate processes and rules, they may also eventually receive higher proportions of benefits generated from decentralized management efforts, or be better able to avoid the aforementioned economic burdens of decentralization22. Furthermore, if they have better access to capital and markets, members of dominant groups may be better equipped to use their natural resource rights productively under decentralization. If the distribution of resource-related benefits and burdens is more unequal under decentralization compared with the distribution in the absence of decentralization, such programmes may enrich members of dominant groups without delivering equivalent benefits to the marginalized. This suggests the potential for worse inequality under such programmes.

Multiple mechanisms may connect decentralization to poverty and inequality. As discussed above, existing theories lead to two competing predictions regarding the effects of decentralization on local inequality. It is also possible that the effect is null, and neither hypothesis is supported. However, because decentralization’s impacts on inequality depend upon its potentially heterogeneous impacts on poverty, any positive, negative or null effect on inequality could be explained by multiple causal mechanisms. For example, decentralization may increase inequality if it increases poverty among the marginalized while alleviating poverty among the advantaged, or if it simply benefits the advantaged more than the marginalized, since either mechanism would widen the gap between the two sub-populations.

We were able to identify 13 such mechanisms, summarized in Table 1. We designed our empirical approach to not only test H1 and H2, but to generate information on the underlying mechanism. This information is highly policy-relevant in light of the fact that the 13 potential mechanisms summarized in Table 1 vary in terms of their normative desirability. For example, more than one-third of the mechanisms summarized in Table 1, even some of the potential inequality-alleviating mechanisms, imply higher rates of poverty for certain sub-populations as a result of decentralization. Other mechanisms can be conceptualized as Pareto improvements because they imply that decentralization provides poverty-alleviating benefits to at least one group without making any other group poorer.

Empirical case

We use the case of Nepal during the 2001–2011 period to test these general hypotheses about the effects of decentralization on inequality. Since the early 1990s, the Government of Nepal has been handing over patches of forested land to local communities and providing those communities with collective rights to manage and use these community forests under the community forestry programme8,23,24,25. During this period, local forestry officials have been implementing the programme by establishing Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs)—village-level forest management groups with official management authority under the programme—in rural villages across the country. As of 2011, local officials had registered more than 17,000 CFUGs, with more than 22,000 registered by 202010,26.

The programme offers subsistence benefits to rural households—such as fodder for domesticated animals, firewood, other non-timber forest products or small timber that local people can collect from the community forest—paid employment opportunities in the CFUG or cash benefits, such as micro-loans or grants paid by the CFUG to member households7,26,27,28,29,30. Local villagers participate in CFUGs through a variety of activities, such as attendance of CFUG governance meetings (which accounted for roughly half of the time and effort that member households allocated to CFUG participation according to one study26) and maintenance or monitoring activities (such as cutting fire lines, planting trees, thinning or serving as forest watchers)7,26. Previous research indicates substantial variation in the depth of members’ participation7,11.

As previous research describes, while the central government guidelines structure how CFUGs constitute themselves and manage community forests, there is still some variation in CFUG governance characteristics26. Typically, local people define membership criteria when a CFUG is formed, and those criteria are usually based primarily on households’ proximity to the forest. There is variation in the demographic profiles of the executive committees of locals that lead CFUGs. Funding to local CFUGs has historically come from a combination of forest product sales, foreign donor funding, membership fees, penalties for rule breaking and interest charged on credit provided by the CFUG. CFUGs have spent those funds on expenses related to forest management and on programmes related to local development or the support of local livelihoods. These governance characteristics are typically defined in the governing documents of each CFUG, though there is some variation in the extent to which CFUGs update these documents on a regular basis, as prescribed by government policy, and in the degree to which the content of these governing documents complies with government guidelines regarding CFUG governance8,26.

There are pronounced disparities in Nepal based on ethnicity and caste. Brahmins, Chhetris and Newars make up the historically advantaged ethnic and caste groups in terms of human development outcomes (health outcomes, literacy and educational attainment), economic status and wealth, and political representation7,31. Dalit castes and Janajati groups (state-recognized indigenous and ethnic minority groups) have consistently scored lower than the Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar groups, on average, in terms of human development31, political representation31, empowerment31, chronic and structural poverty32 and upward mobility33. The Newar community is sometimes, but not always, identified as a Janajati group. However, owing to their traditionally advantaged status, we follow previous scholarship in grouping the Newar community with the Brahmin and Chhetri communities, and using the term ‘Janajati’ to mean ‘non-Newar Janajati’34. In addition, other minority groups, such as Muslims and certain non-Dalit Hindu castes, especially in the southern region of the Terai, have faced various forms of marginalization31.

The forestry decentralization programme was designed with these longstanding social inequalities in mind. Government guidelines direct CFUGs to provide marginalized groups with representation in CFUG executive committees, poverty-alleviating benefits funded from the CFUG budget, designated forest areas for livelihood activities and free or subsidized forest products26,35. Despite these progressive features, prior evidence suggests that ethnicity- and caste-based inequalities persist. Historically, Dalits, Janajatis and other minority households have been less likely to participate substantively in CFUG decision-making7,26,34,36, and some of the subsistence and cash benefits from decentralized forestry may flow disproportionately toward Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar households37. Qualitative case studies and other survey research corroborates this general story, even where households belonging to marginalized groups comprise a share of forest users34,38.

We measured poverty among 522,440 rural Nepalese households using data from the 2001 and 2011 population censuses, calculating a multi-dimensional poverty index for households in the census samples on the basis of multiple indicators related to households’ material deprivations along three dimensions—health, education and living standards, following previous research in this context1. We used records from the Department of Forests to identify when each ward—the smallest officially defined geographic unit in the country—received its first implementation of the decentralized forestry programme, defining implementation as the formation of the first CFUG in that ward. To test H1 and H2, we fit a linear two-way fixed-effects model to the household-level micro-data, generating within-ward estimates of ethnic- and caste-based inequality, as well as predicted within-ward differences in those estimates of inequality on the basis of the local presence or absence of the decentralized forestry programme. See Methods for additional details on the data and methods.

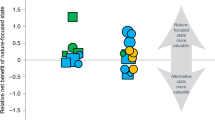

Estimates from the model suggest that, in the absence of the programme, households belonging to the historically marginalized Dalit, Janajati and other minority groups scored higher on the poverty index compared with households in the same ward belonging to the relatively advantaged Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar groups (P < 0.001 for all estimates), which is consistent with previously noted patterns of inequality in Nepal31. More importantly, interaction term estimates from the model suggest that the implementation of the forestry decentralization programme in a ward predicts wider inequalities in poverty indices between the various groups, which is consistent with H2. Figure 1 shows these estimates visually. On the basis of the results of the two-way fixed-effects model, local implementation of the programme predicts within-ward poverty gaps that are roughly 0.15 standard deviation units larger between Dalit households compared with Brahmin, Chhetri or Newar households in the same ward (P < 0.001), with similar predicted increases in the within-ward poverty gap between other minority and Brahmin, Chhetri or Newar households (P = 0.005) and smaller predicted increases in the within-ward poverty gap between Janajati and Brahmin, Chhetri or Newar households (P = 0.007). Thus, inequality is more severe with the decentralized forestry programme in place. Full model results are presented in Supplementary Note 1.

Each estimate represents the average predicted difference in the poverty index between households from a given ethnicity/caste category and Brahmin/Chhetri/Newar (BCN) households in the same ward on the basis of the results of a two-way fixed-effects model fitted on samples of households from population censuses in 2001 and 2011. Treated households are defined as those with forestry decentralization implemented in their ward by the year of the census, whereas control households are defined as those without (Methods). Positive values indicate that average poverty indices for households belonging to a given group are higher compared with poverty indices for Brahmin/Chhetri/Newar households in the same ward. N = 522,440 households included in model estimation. Robust 95% confidence intervals, corrected for clustering at the ward level. See Methods for details on the data and modelling approach.

We generated sub-group estimates of the effect of the decentralized forestry programme on poverty indices for households belonging to each of the four ethnicity and caste categories on the basis of contrasts from the model. These estimates, which are presented visually in Supplementary Note 1, help to situate our results among the multiple mechanisms through which decentralization can reshape inequality (Table 1). The estimated effect of the programme on poverty is strongest among Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar households, equating to a predicted change in the poverty index of roughly −0.16 standard deviation units for these households (P < 0.001). For Janajati households, the estimated effect of the programme is smaller, corresponding to a change in the poverty index of about −0.04 standard deviation units (P = 0.006). Among Dalit and other minority households, the estimated effects of the programme on poverty indices are substantively close to zero and not statistically significant (P = 0.532 and P = 0.877, respectively). While moderately sized confidence intervals do not allow us to completely rule out the possibility that the programme may have an effect on poverty for households belonging to the Dalit and other minority groups, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that the programme has no effect on poverty for these households, and thus find no convincing statistical evidence of such effects.

Taken together, these sub-group estimates indicate a potential causal mechanism explaining the effects of the programme on inequality as estimated previously through the interaction terms. While the interaction estimates presented previously suggest that decentralization widens local poverty gaps between ethnic and caste groups, the sub-group estimates suggest that the programme does so because it delivers benefits that decrease poverty among the historically advantaged Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar groups while having weaker (or null) impacts on poverty among members of the marginalized minority groups. We therefore find no evidence in support of an alternative potential mechanism proposed in Table 1—that the programme widens inequality by worsening poverty among households belonging to marginalized ethnic and caste groups.

One limitation of our analysis is that we are unable to compare the estimated effects of decentralized forestry on inequality to those of other donor projects or government-sponsored initiatives. However, in Supplementary Note 2, we contextualize the estimates from these results by comparing them with broader inequality trends in Nepal between 2001 and 2011. During this period, a number of social and policy-related factors impacted rural poverty, as discussed in Supplementary Note 2. This additional analysis suggests that the estimated effects of the programme on inequality appear substantively small in comparison with broader variations in inequality during the same period.

Discussion

This study contributes to the body of evidence on the human impacts of environmental policies and sustainability initiatives1,2,13,39,40 by providing statistical estimates of the impacts of natural resource decentralization on extant, local-level inequalities in a large, nationwide sample. While the programme is associated with small increases in observed inequality, we find no evidence associating decentralization with on-average increases in poverty among households belonging to marginalized minority groups, building upon previous studies suggesting that forestry decentralization has a net positive impact on alleviating rural poverty1. Furthermore, we hold that there is still the potential for programmes like this one to be improved so that they alleviate inequality and poverty jointly. Future research and policy experimentation should focus on this aim. Recent research suggests that some of the aforementioned equity-focused elements of Nepal’s programme had uneven compliance during the period of our study8, which suggests that improving monitoring and enforcement of equity-related programme features may be enough to make decentralization a ‘win–win’ for inequality and poverty alleviation. Furthermore, there are likely new reforms to decentralization programmes that can enhance their impacts on poverty while creating new inequality-alleviating benefits, such as reforms that make it easier for rural households to establish resource-based commercial enterprises under these programmes, coupled with targeted capacity-building and other supports for historically marginalized groups24,30. Coupling natural resource decentralization with payment schemes may also help to equalize outcomes under decentralization if such payment schemes target the marginalized effectively41.

Nepal’s decentralized forestry programme is an ideal test case through which to test our hypotheses, not only because it is a mature programme that is often regarded as a model decentralization policy, but also because it is an exceptionally progressive one from the perspective of equity7,8. Nonetheless, readers should not assume that the present or future effects of Nepal’s decentralization programme are necessarily the same as the estimated effects of the programme during the study period. In the years since, Nepal has transitioned to a federal state, forest-dependent livelihood strategies have become less common in some rural areas (owing to migration and other factors)29,30,42 and forestry-sector policy has evolved incrementally43. Furthermore, some research suggests that the Scientific Forest Management programme, promoted through government policies over the past decade to commercialize community forests in Nepal through the prioritization of high-value timber varieties in some communities, may disproportionately benefit local elites44. We encourage future research on these more recent developments.

Several other important questions remain in light of our study. First, our household-level analysis is unable to speak to gender disparities in the distribution of benefits under decentralization11,45. Second, Nepal’s decentralization programme resembles similar programmes in other countries, in that it contains elements of centralization, with central government policies and local forestry bureaucrats playing an important role in shaping the local benefit-sharing practices of CFUGs46,47. While the aforementioned equity-related guidelines promulgated by the government suggest that such centralization can be harnessed in pursuit of more equitable outcomes, the persistence of inequality under decentralization suggests that there is room for future research to study the conditions under which such central efforts to improve equity are successful.

Third, how do variations in local context influence the effects of decentralization on inequality? This is an important area for future research for several reasons. First, it is possible that the ethnic composition of the community moderates the effects seen in this study. For example, in Nepal, there are some villages where households belonging to marginalized ethnic and caste minority groups are the numeric majority. While extant theory and qualitative evidence strongly suggest that ethnic and caste-based marginalization is a function of discriminatory norms and local power dynamics9,20, which are unlikely to be reversed simply because historically marginalized groups are in the local numeric majority, the role of local demographic composition as a potential moderator of the effects of decentralization on inequality is an area for further research. Relatedly, rates of participation among marginalized minority groups, especially Dalits, in the executive committees that govern CFUGs have been low in many local settings26,34, though qualitative studies suggest that such participation may have increased since the data were collected36. Future research should examine what effect, if any, this local representation has on the inequality-related outcomes considered in this study.

It is also possible that the effects of decentralization programmes on inequality interact with the local historical context around natural resource governance. The extant qualitative literature suggests that, in some settings, local elites have a history of traditional control over natural resource governance that predates decentralization, and that these entrenched claims allow them to dominate the institutions of decentralization42. It is therefore possible that outcomes are most unequal in communities with a history of such traditional institutions.

Finally, ecological factors may play a role in moderating the effects of decentralization on inequality owing to differences in resource salience between different physiographic regions. For example, some local settings in the low-lying Terai region of Nepal are characterized by elite capture of high-value tree species, which suggests that decentralization may be more likely to widen inequalities in these communities than in others6. Conversely, certain localities in the mountain region have seen marginalized groups actively engage in the commercial sale of traditional medicinal plants from decentralized forestry as market demand for such products has grown, which may help to dampen inequality48. While our additional analyses of differences between the physiographic regions in Supplementary Note 2 are unable to explore such heterogeneities since we lack detailed local data on resource salience across the study area and study period, contextual details such as these suggest the potential for within-country differences in the decentralization–inequality relationship across different local ecological contexts.

Methods

Census sample and poverty index

We drew our sample of households from an 11% random subset from the 2001 population census and a 12% random subset from the 2011 population census49,50. The data from the two census years represent a random cross-sectional probability sample from each census, rather than a linked panel. Urban wards were excluded from our analytic sample. This study complied with the guidance of the Human Research Protection Program at Indiana University, as explained below (see ‘Ethical review’ section).

This approach operationalizes inequality on the basis of ethnicity and caste because local inequalities on this basis are deeply ingrained in Nepalese society, though there are other important inequalities based on gender and region that our study is unable to capture31. We used data on the castes and ethnic identities of each household head to cross-reference each household’s ethnic or caste group with existing literature and official sources31,51, constructing four categories on the basis of existing typologies31,52: (1) Brahmin/Chhetri/Newar, (2) Dalit, (3) Janajati and (4) other minority. Consistent with previous research, the ‘other minority’ category includes members of any caste or ethnic group who do not belong to the other three categories and is comprised mostly of non-Dalit Terai/Madhesi Hindu minority-caste groups and Muslims31. Supplementary Note 2 includes descriptive statistics on our census sample.

To measure poverty among households in the sample, we calculated a multi-dimensional poverty index that included six indicators measuring three dimensions of deprivation: health, education and living standards. As household-level measures of poverty, multi-dimensional indices are justified on the grounds that poverty manifests as multiple deprivations of a households’ basic needs, and that health outcomes, educational attainment and household living conditions are therefore a more ‘direct method’ of poverty measurement than are measures of household income53,54,55. Extended Data Table 1 shows the six indicators used to calculate the household-level poverty index, their weights and how they were measured from the census questionnaires. The poverty index was standardized on the basis of the mean and standard deviation in 2001. The three dimensions included in the poverty index were based on established multi-dimensional poverty indices, and are justified on the grounds that they reflect some of the central material deprivations often experienced by poor households1,56,57. The six indicators were selected to be similar to previous studies in this context1, and are commonly employed in poverty indices owing to the fact that they capture clear deprivations across each dimension56.

The calculation of multi-dimensional poverty indices can vary depending upon data availability and theory56. In our case, there are some indicators used in previous poverty indices that are not included here. Most notably, although some multi-dimensional poverty indices include data on nutrition in the health dimension54, the censuses from which we drew our sample did not collect data on nutrition.

Furthermore, two common indicators of health and education are omitted from our index owing to the fact that they are inapplicable to large sub-samples in our data: child mortality (measured in other studies as the death of a child below the age of 5 or 6 years1,54) and school attendance (measured, in this case, as whether or not the household had at least one child aged between 6 and 16 years who was not enrolled in school1). More than half of our sample lacked children under the age of 6 years, and nearly one-third lacked school-aged children. The issue of non-applicability in the construction of multi-dimensional poverty indices has long been recognized58, and recent research suggests that non-applicability can have a substantial impact on such indices59. Some studies simply code all households for which an indicator is non-applicable as non-deprived on those indicators, which would mean, for example, automatically coding households in our sample who lacked children under the age of 6 years as non-deprived on the child mortality indicator, thereby making it less likely that these ineligible households will achieve poverty indices as high as the eligible households by the design of the index. This could bias comparisons in our case. This is because ineligibility rates for child mortality and school attendance are not only high in our sample but also noticeably correlated with the four ethnicity and caste categories. For example, compared with Dalit households in our sample, Brahmin, Chhetri and Newar households have a roughly 20% lower likelihood of meeting the applicability criterion for the child mortality indicator, which is to have household members in the relevant age group during the period preceding the census. This could create apparent inequalities in the health dimension of the poverty index that are driven more strongly by differential eligibility among sub-groups than by measured deprivations. Other studies deal with the issue of non-applicability by calculating and weighting the index differently for households with non-applicable indicators, but this compromises comparability across households and sub-populations, and is therefore not appropriate for our study54,60. We therefore used the ‘universal measures’ approach described by Alkire et al.54, which is to limit the indicators to those that are universally applicable in the population (or nearly so) with coverage across each dimension.

It is reasonable to expect that the index will capture changes in poverty induced by the decentralized forestry programme through several theoretical mechanisms. First, community forestry often provides direct income from employment and forest-based commercial livelihood opportunities to participants, and some CFUGs provide micro-loans and small grants to member households26,28,61. Households can use these direct benefits to invest in health, education and living standards. Second, by improving the availability and supply of forest products (such as wild foods), community forestry can cause direct changes in consumption. Third, cheaper access to forest products may mean that some households have more funds to devote to consumption across areas such as nutrition, healthcare and education, and towards household amenities. Finally, community forestry provides public good benefits at the village level. These include investments in local development projects, such as projects to fund local schools or improve local water infrastructure26, which may improve the wellbeing of households regardless of their reliance on the community forest or direct participation in the CFUG.

One limitation of our census data is that they do not contain information on forest-related income. We are therefore unable to use the distribution of forest-related income or the collection of forest products as alternative dependent variables in our analysis. Such data would provide a number of advantages, including the ability to calculate a Gini index of income, which is often of interest in studies of inequality. More generally, data on forest income and forest benefits could allow for a more direct examination of how decentralization changes the flow of both.

Our dependent variable, however, offers several advantages that such an income measure would not. First, while examining the flow of benefits may reveal inequalities in the distribution of those benefits, those inequalities are policy-relevant owing to their potential impacts on the material living conditions of rural resource users. An analysis of the former would not necessarily yield clear information on the latter, since large apparent inequalities in forest benefits might manifest in either small or large differences in households’ abilities to meet their basic needs in consumption, healthcare, education and living standards. Second, direct, household-level measures of forest income and forest product collection, which are themselves often non-monetary and sometimes difficult to quantify, would not capture the subset of benefits from forestry decentralization that accrue as public goods, such as the local development investments mentioned above. These benefits may have important impacts on human development, even among households who do not use community forests or interact with the programme directly. Third, while direct income measures would allow us to calculate a Gini index of forest income, thereby producing a clearer picture of how forestry decentralization changes the concentration of direct forest benefits as previous studies have done5, Gini indices have their own limitations. Namely, such indices are blind to the identities of individual households, in contrast to our modelling approach, which operationalizes inequality as average poverty gaps between members of politically and socially relevant groups that map onto longstanding patterns of marginalization and discrimination (allowing us to test the various mechanisms proposed in Table 1).

With these points in mind, we recommend that future studies complement ours with analyses that are similar in method to the current study, but with forest income and direct forest benefits as the outcomes of interest. Such analyses, which would require large-scale micro-data on income and benefits collected in the presence and absence of forestry decentralization, would help to contextualize our results. Specifically, such analyses could estimate changes in the overall concentration of forest income caused by decentralization. Furthermore, they could provide more detailed information on the specific micro-processes that give rise to the overall inequalities estimated in our study, which could inform the design of future policies meant to correct inequality under forestry decentralization.

Data on the forestry decentralization programme

The data on forestry decentralization were collected from the Department of Forests in January 2017 and contain records on all CFUGs reported by local forestry officials to the central government and logged in the database by that date (18,960 CFUGs). During the 2001–2011 period, rural Nepal was divided into more than 3,000 Village Development Committees and municipalities, which were divided further into roughly 36,000 wards that received implementation of the decentralization programme in a staggered manner. For a given household interviewed in ward w at census year t, we used these data to construct a dichotomous policy treatment indicator for whether or not at least one CFUG was formed under the forestry decentralization programme in ward w before census year t. Ward numbers associated with CFUGs were mostly or completely missing from the database for 16 districts. For five of these districts, we were able to fill in the missing data using records provided by district-level forest offices. Observations from the remaining 11 districts were excluded from the analysis.

In addition to community forestry practiced through CFUGs, Nepal had other, smaller-scale natural resource management programmes during the study period that emphasized local participation and poverty alleviation to varying degrees. Most notably, these included leasehold forestry (under which about 40,000 ha of forest were managed by 201862) partnership forests (about 7,000 ha by 2008) and Conservation Area Management Committees (CAMCs), which are involved in management at some protected areas such as the Annapurna Conservation Area42. Because our data capture the implementation of the community forestry programme, as measured through the formation of CFUGs registered under the programme, our analysis is limited to CFUGs only, and is unable to speak to the impacts of these other management models.

Modelling approach

We used a two-way fixed-effects modelling approach that provided within-ward estimates of ethnic and caste-based inequality, and predicted within-ward differences in those estimates of inequality on the basis of the presence or absence of the forestry decentralization programme, while controlling for ward-level fixed-effects, key characteristics of the household and year fixed-effects. The model is expressed by the following equation (1):

In equation (1), povertyh is the multi-dimensional poverty index for household h, and CFwt is the dichotomous indicator for whether or not ward w had at least one CFUG that formed under the forestry decentralization programme before census year t. The ethnic and caste background of household h is given by a vector of dummy variables representing whether or not the household head is Dalit, Janajati or a member of another minority group (Dalith, Janajatih or other minorityh), with Brahmin/Chhetri/Newar as the omitted comparison category. The variable 2011t is a dichotomous indicator for whether or not the observation comes from the 2011 census, with the 2001 census treated as the omitted comparison category. uw is a vector of ward fixed-effects, and Xh is a vector of additional household-level covariates to improve the precision of the estimates—a dichotomous indicator for whether or not the household head was a woman in the census year and the age of the household head at the census date.

The coefficient estimates on the ethnic and caste minority categories (β2, β3 and β4) represent the average within-ward gap in the poverty index between members of each minority category and the Brahmin/Chhetri/Newar category, in 2001 standard deviation units, in wards that had not yet received the programme. The estimates on the interactive terms (β5, β6 and β7) represent the predicted within-ward differences in each of those poverty gaps in the presence of the programme compared with its absence. We interpret these coefficients on the interaction terms as our best within-ward estimates of the association between programme implementation and local inequality. Whereas Supplementary Note 2 presents simple, over-time changes in within-ward poverty gaps between 2001 and 2011, the interaction term estimates from the regression model represent our best estimates of changes in within-ward inequality that we can attribute to the decentralized forestry programme.

Recent work suggests that causal inference with two-way fixed-effects often depends upon strict parametric assumptions. Specifically, in a ‘multi-period’ panel data structure, where units experience treatment at more than one point in the panel (such as before the 2001 census and between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, in our data), this approach only identifies causal impacts under the strict assumption of linear and additive effects—an assumption which may not always hold true in practice (even when weighting methods are used)63. This same work shows that two-way fixed-effects models fitted on a classical difference-in-differences data structure—where there are two time periods, and where treatment is only assigned between those two time periods—do not depend on these parametric assumptions. By extension, the latter approach is more likely than the former to estimate unbiased causal effects. Therefore, we excluded from our analytic sample all households in wards that had at least one CFUG that formed under the forestry decentralization programme before the 2001 census year, since this produces the classical difference-in-differences data structure. Omitting these observations also avoids what the econometrics literature has called the ‘forbidden comparisons’ problem64. This approach leaves us with a final analytic sample of N = 522,440 households with complete data.

This estimation approach is robust to a wide variety of potential unmeasured confounders if modelling assumptions of the method are met65. Importantly, because it conditions on ward and year, it estimates effects without conditioning on ward- and year-level observables, as would be the case with other inference approaches such as covariate matching, which is difficult in data-sparse environments and when the dependent variable is a complex social outcome with potentially unmeasurable predictors (such as inequality). By including year fixed-effects in the estimation, this approach controls for the potentially confounding effects of large-scale, national-level trends that may have taken place across the country, and by including ward fixed-effects in the estimation, the approach controls for unmeasured time-invariant covariates at the ward level (see Supplementary Note 3 for a more detailed discussion).

Despite the strength of this modelling strategy, it is not robust to reverse causality, though this is the case with many alternative approaches to causal inference such as those based on covariate matching66. Finally, one potential threat to the validity of our estimation approach is the possibility of bias arising from time-varying, ward-varying confounding variables. In Supplementary Note 3, we discuss this last possibility in greater detail and attempt to control for seven potential confounding variables of this type. We find that the estimates reported in our results are replicated when we attempt to control for these time-varying covariates. As we discuss in Supplementary Note 3, while these additional tests do not rule out the possibility of omitted variable bias owing to the fact that there is still the potential for omitted variables that we cannot observe, they make this possibility appear less probable. In Supplementary Note 4, we also re-ran our analysis on a larger sample that did not omit households in wards treated before the 2001 census year, as described above (N = 733,991). While the estimates do exhibit some differences from those reported in our main results, the estimates in Supplementary Note 4 are less credible since they rely upon less plausible causal assumptions and are influenced by the forbidden comparisons problem, as noted above.

Despite the strengths of our approach, our analysis cannot capture potential local heterogeneities in the implementation of the equity-focused elements of the programme—heterogeneities which are noted in the Discussion and which may imply that effects on inequality are stronger or weaker in some local contexts than in others. This is a potential area for future research. Finally, for treated wards, Eq. (1) does not capture the age of the CFUG by year t, and therefore does not estimate whether the effects of the programme on inequality might deepen over time. We address this issue with an additional analysis in Supplementary Note 5, which presents an alternative statistical model to explore the possibility of differences in these effects over time.

Analyses were performed through estimation commands in Stata (version 18), and visualizations were generated through graphing commands in R (version 4.2.1).

Ethics statement

This study uses de-identified, secondary census micro-data collected in 2001 and 2011 by the Government of Nepal and provided to the research team by the Central Bureau of Statistics. The Human Research Protection Program at Indiana University considers studies using de-identified secondary data to be ‘non-human subjects research’ and does not subject them to review.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The census micro-data analysed in this study were provided to the research team by the National Statistics Office (previously the Central Bureau of Statistics), Government of Nepal. Restrictions on the census micro-data prevent the research team from sharing the datasets. However, if permission is granted by the appropriate government agency, the corresponding author will share the data analysed in this study upon reasonable request. Interested parties may contact the National Statistics Office (info@nsonepal.gov.np).

Code availability

The analyses were performed using analysis and graphing commands in Stata (version 18) and R (version 4.2.1). The code files to run these commands will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Oldekop, J. A., Sims, K. R. E., Karna, B. K., Whittingham, M. J. & Agrawal, A. Reductions in deforestation and poverty from decentralized forest management in Nepal. Nat. Sustain. 2, 421–428 (2019).

Hajjar, R. et al. A global analysis of the social and environmental outcomes of community forests. Nat. Sustain. 4, 216–224 (2021).

Miteva, D. A., Pattanayak, S. K. & Ferraro, P. J. Evaluation of biodiversity policy instruments: what works and what doesn’t?. Oxf. Rev. Economic Policy 28, 69–92 (2012).

Agrawal, A., Chhatre, A. & Hardin, R. Changing governance of the world’s forests. Science 320, 1460–1462 (2008).

Persha, L. & Andersson, K. P. Elite capture risk and mitigation in decentralized forest governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 24, 265–276 (2014).

Iversen, V. et al. High value forests, hidden economies and elite capture: evidence from forest user groups in Nepal’s Terai. Ecol. Econ. 58, 93–107 (2006).

Cook, N. Experimental evidence on minority participation and the design of community-based natural resource management programs. Ecol. Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108114 (2024).

Cook, N. J., Benedum, M. E., Gorti, G. & Thapa, S. Promoting women’s leadership under environmental decentralization: the roles of domestic policy, foreign aid, and population change. Environ. Sci. Policy 139, 240–249 (2023).

Agarwal, B. Gender and Green Governance: the Political Economy of Women’s Presence within and beyond Community Forestry (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Pandey, H. P. & Pokhrel, N. P. Formation trend analysis and gender inclusion in community forests of Nepal. Trees For. People 5, 100106 (2021).

Agarwal, B. Gender Challenges (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Coleman, E. A. & Fleischman, F. D. Comparing forest decentralization and local institutional change in Bolivia, Kenya, Mexico, and Uganda. World Dev. 40, 836–849 (2012).

Oldekop, J. A., Holmes, G., Harris, W. E. & Evans, K. L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 30, 133–141 (2016).

Nilsson, M., Griggs, D. & Visbeck, M. Policy: map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 534, 320–322 (2016).

Malla, Y. B., Neupane, H. R. & Branney, P. J. Why aren’t poor people benefiting more from community forestry. J. For. Livelihood 3, 78–92 (2003).

Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005).

Coleman, E. A. & Mwangi, E. Conflict, cooperation, and institutional change on the commons. Am. J. Political Sci. 59, 855–865 (2015).

Knight, J. & Calvert, R. Institutions and Social Conflict (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

Pokharel, B. K., Branney, P., Nurse, M. & Malla, Y. B. Community forestry: conserving forests, sustaining livelihoods and strengthening democracy. J. For. Livelihood 6, 8–19 (2007).

Kashwan, P. Integrating power in institutional analysis: a micro-foundation perspective. J. Theor. Politics 28, 5–26 (2016).

Nightingale, A. J. The experts taught us all we know’: professionalisation and knowledge in Nepalese community forestry. Antipode 37, 581–604 (2005).

Andersson, K. P. et al. Wealth and the distribution of benefits from tropical forests: implications for REDD+. Land Use Policy 72, 510–522 (2018).

Bajracharya, D. Deforestation in the food/fuel context: historical and political perspectives from Nepal. Mt. Res. Dev. 3, 227–240 (1983).

Sapkota, L. M., Dhungana, H., Poudyal, B. H., Chapagain, B. & Gritten, D. Understanding the barriers to community forestry delivering on its potential: an illustration from two heterogeneous districts in Nepal. Environ. Manag. 65, 463–477 (2020).

Ojha, H., Persha, L. & Chhatre, A. Community Forestry in Nepal: a Policy Innovation for Local Livelihoods (International Food Policy Research Institute, 2009).

Persistence and Change: Review of 30 Years of Community Forestry in Nepal (Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, 2013).

Dongol, C. M., Hughey, K. F. D. & Bigsby, H. R. Capital formation and sustainable community forestry in Nepal. Mt. Res. Dev. 22, 70–77 (2002).

Rai, R., Neupane, P. & Dhakal, A. Is the contribution of community forest users financially efficient? A household level benefit–cost analysis of community forest management in Nepal. Int. J. Commons 10, 152–157 (2016).

Benedum, M. E., Cook, N. J. & Vallury, S. Remittance income weakens participation in community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-16436-300334 (2025).

Cook, N. J., Khatri, D. B., Poudel, D. P., Paudel, G. & Acharya, S. Dropping out of environmental governance: why Nepal’s community-based forestry program is losing participants. Elementa (Wash. D.C.) https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2024.00059 (2025).

Bennett, L., Tamang, S., Onta, P. & Thapa, M. Unequal Citizens: Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal (The World Bank, 2006).

Wagle, U. R. The caste/ethnic bases of poverty dynamics: a longitudinal analysis of chronic and structural poverty in Nepal. J. Dev. Stud. 53, 1430–1451 (2017).

Moving Up the Ladder: Poverty Reduction and Social Mobility in Nepal (The World Bank, 2016).

Sunam, R. K. & McCarthy, J. F. Advancing equity in community forestry: recognition of the poor matters. Int. For. Rev. 12, 370–382 (2010).

Community Forestry Development Guidelines (Government of Nepal, 2009).

Devkota, B. P. Social inclusion and deliberation in response to REDD+ in Nepal’s community forestry. For. Policy Econ. 111, 102048 (2020).

Karki, A. & Poudyal, B. H. Access to community forest benefits: need driven or interest driven?. Res. Glob. 3, 100041 (2021).

Yadav, B. D., Bigsby, H. & MacDonald, I. How can poor and disadvantaged households get an opportunity to become a leader in community forestry in Nepal?. For. Policy Econ. 52, 27–38 (2015).

Timko, J. et al. A policy nexus approach to forests and the SDGs: tradeoffs and synergies. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 34, 7–12 (2018).

Persha, L., Agrawal, A. & Chhatre, A. Social and ecological synergy: local rulemaking, forest livelihoods, and biodiversity conservation. Science 331, 1606–1608 (2011).

Lambini, C. K. & Nguyen, T. T. Impact of community based conservation associations on forest ecosystem services and household income: evidence from Nzoia Basin in Kenya. J. Sustain. For. 41, 440–460 (2022).

Poudel, D. P. Migration, forest management and traditional institutions: acceptance of and resistance to community forestry models in Nepal. Geoforum 106, 275–286 (2019).

Hobley, M. & Malla, Y. B. in Routledge Handbook of Community Forestry (eds Palmer, J. et al.) 477–490 (Routledge, 2022).

Paudel, D., Pain, A., Marquardt, K. & Khatri, S. Reterritorialization of community forestry: scientific forest management for commercialization in Nepal. J. Political Ecol. 29, 455–474 (2022).

Kimengsi, J. N. & Bhusal, P. Community forestry governance: lessons for Cameroon and Nepal. Soc. Nat. Resour. 35, 447–464 (2022).

Basnyat, B., Treue, T. & Pokharel, R. K. Bureaucratic recentralisation of Nepal’s community forestry sector. Int. For. Rev. 21, 401–415 (2019).

Basnyat, B., Treue, T., Pokharel, R. K., Lamsal, L. N. & Rayamajhi, S. Legal-sounding bureaucratic re-centralisation of community forestry in Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 91, 5–18 (2018).

Kunwar, R. M., Mahat, L., Acharya, R. P. & Bussmann, R. W. Medicinal plants, traditional medicine, markets and management in far-west Nepal. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9, 24 (2013).

Central Bureau of Statistics. National Population Census. (Government of Nepal, 2001).

Central Bureau of Statistic. National Population Census. (Government of Nepal, 2011).

Population Monograph of Nepal 2, 165–170 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2014).

Bennett, L., Dahal, D. R. & Govindasamy, P. Caste, Ethnic and Regional Identity in Nepal: Further Analysis of the 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. (Macro International, Inc., 2008).

Sen, A. Poverty and Famines: an Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. (Oxford Univ. Press, 1983).

Alkire, S. et al. Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

Afonso, H., LaFleur, M. & Alarcón, D. Multidimensional Poverty: Development Issues No. 3. (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015).

Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2018: The Most Detailed Picture to Date of the World’s Poorest People (Human Development Initiative, 2018).

Dirksen, J. & Alkire, S. Children and multidimensional poverty: four measurement strategies. Sustainability 13, 9108 (2021).

Alkire, S. & Santos, M. E. Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Dev. 59, 251–274 (2014).

Klasen, S. & Villalobos, C. Diverging identification of the poor: a non-random process. Chile 1992–2017. World Dev. 130, 104944 (2020).

Santos, M. E. Challenges in designing national multidimensional poverty measures. (United Nations, 2019).

Pandit, B. H., Albano, A. & Kumar, C. Community-based forest enterprises in Nepal: an analysis of their role in increasing income benefits to the poor. Small-scale For. 8, 447–462 (2009).

Nepal, P., Khanal, N. R., Zhang, Y., Paudel, B. & Liu, L. Land use policies in Nepal: an overview. Land Degrad. Dev. 31, 2203–2212 (2020).

Imai, K. & Kim, I. S. On the use of two-way fixed effects regression models for causal inference with panel data. Political Anal. 29, 405–415 (2021).

Borusyak, K. & Jaravel, X. Revisiting Event Study Designs. Rev. Econ, Stud. 91, 3253–3285 (2024).

Morgan, S. L. & Winship, C. Counterfactuals and Causal Inference (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Cunningham, S. Causal Inference: the Mixtape (Yale Univ. Press, 2021).

Acknowledgements

This study received funding from the National Science Foundation of the USA through grants BCS-2343136 (to N.J.C.), SES-1757136 (to K.P.A.) and SES-2242507 (to N.J.C., K.P.A. and T.G). We thank the following agencies of the Government of Nepal that provided essential data for this study: the Central Bureau of Statistics, the Ministry of Forests and Environment and five district-level forestry offices. Participants in the Indiana University Ostrom Workshop Colloquium Series provided substantive feedback on an earlier version of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.J.C. conceived and designed the study, the theoretical approach and the methodological approach. N.J.C., K.P.A. and T.G. acquired funding. N.J.C., M.E.B., B.K.K., D.B.K. and D.P.P. acquired the data and compiled the dataset. N.J.C. performed the statistical analysis. N.J.C., K.P.A., M.E.B., T.G., B.K.K., D.B.K. and D.P.P. wrote and edited the paper. N.J.C. is the corresponding author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Jude Kimengsi, Abigail York and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–4 and References.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cook, N.J., Andersson, K.P., Benedum, M.E. et al. Effects of forestry decentralization on rural inequality in Nepal. Nat Sustain (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01729-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01729-z