Abstract

The large-scale integration of semiconductor spin qubits into quantum processors will require the characterization of quantum components at scale. However, such characterization is challenging and typically requires radio-frequency measurements at millikelvin temperatures and the presence of magnetic fields. Here we report a scalable architecture for characterizing spin qubits using a quantum dot crossbar array. The approach, which we term as the qubit-array research platform for engineering and testing, uses a crossbar array comprising tightly pitched spin-qubit tiles and is implemented in planar germanium, with the potential to host 1,058 single-hole spin qubits. We measure a subset of 40 tiles and demonstrate key device functionality at millikelvin temperatures, including tile addressability, threshold voltage and charge noise statistics, as well as the characterization of hole spin qubits and their coherence times in a single tile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Spin qubits1 can be manufactured in modern semiconductor foundries2 and can leverage decades of technology development in the semiconductor industry. They are, thus, a promising route to address the scalability challenges of quantum technology. However, the integration of millions of highly coherent spin qubits into a quantum processor still requires advances in materials synthesis, fabrication processes and control strategies3,4. These developments depend on the ability to test quantum components at scale for yield and performance, and under environmental conditions such as cryogenic temperatures.

Various approaches have been explored to streamline the cryogenic testing of quantum devices, including on-chip and off-chip multiplexers5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, to improve the limited input and output connectors in existing cryostats. Alternatively, a cryogenic 300-mm-wafer prober has been used to perform low-frequency measurements on a large number of quantum dots at 1.6 K (ref. 15), offering fast feedback to optimize complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor-compatible fabrication processes of spin-qubit devices. However, these approaches do not currently offer a scalable solution for the statistical measurements of spin qubits, which typically require radio-frequency (RF) measurements at millikelvin temperatures in the presence of magnetic fields.

In this Article, we report a scalable architecture for characterizing spin qubits using a quantum dot crossbar array; the approach is termed a qubit-array research platform for engineering and testing (QARPET). The crossbar is based on arrayed, individually addressable and tightly pitched spin-qubit tiles, with a qubit density of 2 × 106 mm−2 and sublinear scaling of interconnects. The architecture is inspired by device matrix arrays, which are widely used in the semiconductor industry to assess the matching properties of transistors16,17,18,19. We implement QARPET in planar germanium (Ge) quantum wells20 and fabricate a large crossbar array device of 23 × 23 tiles, which has the potential to test 1,058 single-hole spin qubits within a single cooldown. We show that the approach offers tile addressability and can acquire spin-qubit device metrics, including threshold voltages and charge noise, by using RF reflectometry at millikelvin temperatures. We extend these measurements to a statistical analysis across 40 tiles, illustrating the scalability of the approach. We also demonstrate spin control within a tile by implementing singlet–triplet (ST) qubits (operated with baseband-only control signals) and Loss–DiVincenzo (LD) single-hole qubits (driven by electric-dipole spin resonance), and characterize their coherence times.

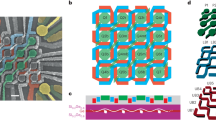

A scalable spin-qubit tile in a crossbar array

Figure 1a,b illustrates the design of a scalable spin-qubit tile that can be arranged into an n × m crossbar array architecture. Plunger gates control the chemical potentials of the charge sensor (Ps) and of two quantum dots (P1 and P2). Barrier gates adjust the coupling between the sensor and the ohmics (Bs), the sensor and the neighbouring dot (B1), and between the dots (B2). A global screening gate (S) shapes the surrounding potential landscape. Two ohmic electrodes (O1 and O2) run vertically and merge at the edges into a single pair of ohmic contacts for the entire crossbar, minimizing the off-chip resonators needed for RF reflectometry. Rows of tiles share plunger gates, columns share barrier gates and the meandering design of P1 prevents overlaps, enabling Ps, P1 and P2 to be patterned in the same layer to simplify fabrication. Similar to wordlines and bitlines in random-access memories21,22, a specific tile indexed (i, j) is activated and addressed by energizing its Ps and Bs electrodes, which form a sensor dot sufficiently coupled to the ohmic contacts to provide a transport path. With sensor-based tile selectivity, dot plungers and barrier electrodes can be shorted across tiles, reducing the required control lines. An n × m crossbar hosting 2mn qubits needs only (n + m + 7) lines: (n + m) for Bs and Ps; seven for P1, P2, B1, B2, S, O1 and O2. Therefore, this architecture achieves the sublinear scaling of control lines with the number of qubits, following Rent’s rule with an exponent p = 0.5 (refs. 23,24).

a, Design of a scalable spin-qubit tile comprising a sensing dot and a double dot, with plunger gates (Ps, P1, P2), barrier gates (Bs, B1, B2), ohmic contacts (O1, O2) and a screening gate S. b, Tile layout, with meandering vertical plunger gates and horizontal barrier gates, allows for integration into a scalable device architecture. A single tile (for example, the central tile in the illustrated 3 × 3 array) is selected for measurements by energizing the correspondent sensor plunger and barrier with gate bias \({V}_{{P}_{{\rm{s}}}}\) and \({V}_{{B}_{{\rm{s}}}}\), respectively. The reflectance measured between O1 and O2 will be proportional to the reflectance of the sensor in the central tile, allowing to be exclusively sensitive to the charges in the dots of the selected tile. c, False-coloured scanning electron microscopy image highlighting a tile within a crossbar device comprising 23 × 23 tiles and fabricated on a Ge/SiGe heterostructure following the architecture shown in a and b. The colour scheme matches the schematics in a. The tile has a footprint of 1 × 1 μm2; the circular plungers defining the sensor and the dots have a nominal diameter of 180 nm and 130 nm, respectively. The barriers B1 and B2 have a width of 60 nm and 50 nm, respectively. d, Transmission electron microscopy images showing cross-sections of a tile within the crossbar. The top panel is along the horizontal axis of the tile, crossing the circular sensor and dot plungers. The bottom panel is along the vertical axis of the tile, crossing the sensor barriers and circular plunger. The multilayer gate structure is fabricated on a buried 16-nm-thick Ge/SiGe quantum well, positioned at 55 nm from the surface. The colour scheme and labels match the schematics in a. e, Scanning electron micrograph image showing the entire crossbar device extending over an area of 23 × 23 μm2 and featuring 529 tiles arranged in a 23 × 23 array indexed by plunger rows i and barrier columns j. The gate electrodes and the ohmic contacts fan out at the periphery of the crossbar.

We implement this architecture in a low-disorder Ge/SiGe heterostructure on a Si wafer25 (Methods), which was used in several spin-qubit experiments26,27,28,29. We fabricate a crossbar array of 23 × 23 spin-qubit tiles, which can support up to 1,058 individually addressable spin qubits, whereas requiring only 53 control lines. The fabrication process entails germanosilicide ohmic contacts to the Ge quantum well and a multilayer gate stack patterned by electron-beam lithography and metal lift-off (Methods). The scanning electron microscopy image shown in Fig. 1c provides detailed views of a tile within the crossbar. The tile footprint is 1 μm, achieved through a tightly knit fabric of nanoscale electrodes and yielding a high density of quantum dot qubits of 2 × 106 mm−2. Furthermore, the tile footprint is comparable with the length scale of strain and compositional fluctuations of the heterostructure30, making the device suitable for probing variations in quantum dot metrics arising from the underlying heterostructure.

The transmission electron microscope images in Fig. 1d show cross-sections of a tile along the circular dot and sensor plunger direction (top panel) and, orthogonally, across the sensor plunger and barrier direction (bottom panel). These images illustrate the germanosilicide ohmic contacts to the buried Ge quantum well and the three layers of gates (screening, barriers and plungers) with a dielectric in between. To electrostatically define charge sensors and quantum dots in the buried Ge quantum well, circular plunger gates are set to a negative potential to accumulate holes, whereas barrier-gate potentials are adjusted to tune the tunnel couplings between the source and drain reservoirs and between the dots. The image of the entire crossbar (Fig. 1e) highlights the fan out of the nanoscale gate electrodes and ohmic contacts at the periphery of the crossbar (Supplementary Fig. 1). The realization of such a QARPET chip demonstrates the viability of our approach to array dense spin-qubit tiles even without the strict process control available in an advanced semiconductor foundry.

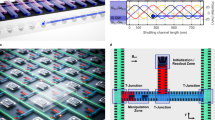

Charge sensor addressability and single-hole occupancy

We evaluate the functionality of the device at 100 mK, by measuring a subset of 40 tiles, arranged in five rows and eight columns. The preselection process, based on the cryogenic setup and packaging constraints and testing at 4.2 K, is detailed in Supplementary Fig. 1, together with the considerations of potential failure modes of the architecture (Supplementary Discussion). Tile selectivity is demonstrated using RF reflectometry to measure sensor reflectance through the ohmic contacts, tuning the sensor of one tile at a time to a regime showing clear Coulomb blockade signatures in Bs versus Ps gate maps (Fig. 2a). A negative slope of the Coulomb peaks confirms that the measured reflectance corresponds to the targeted tile. If the reflectance signal originated from another tile, vertical or horizontal Coulomb peak lines would appear. The vertical lines would indicate that the signal comes from the sensor of a tile in the same row as the targeted tile, as the selected barrier gate would not affect its chemical potential, whereas the horizontal lines would correspond to a sensor of a tile in the same column. We are able to tune the sensor of 38/40 tiles in Coulomb blockade, demonstrating single-tile addressability in the dense array. These measurements also demonstrate the robustness of the RF reflectometry approach in addressing hundreds of sensor dots connected in parallel, despite the increased parasitic capacitance.

a, Sensor reflectance maps are measured on a QARPET device with RF reflectometry as a function of the sensor plunger (Ps) and sensor barrier (Bs) for a subset of 40 tiles arranged in five rows and eight columns of the device. The selectivity of each tile is confirmed by the observation that the sensor signal of all sensor barrier maps presents Coulomb peaks with a negative slope. This indicates that the sensing dot is capacitively coupled to both intended sensor plunger gate (Ps) and sensor barrier gate (Bs). Furthermore, a Coulomb blockade is observed in all tiles except for two ((4, 22) and (21, 7)), indicating that the tile design is suitable for performing charge sensing. b, Sensor reflectance maps as a function of the sensor plunger (Ps) and the plunger of dot 1 (P1) show charge occupation down to the last hole for the 37 tiles with a sensor that displays a clear Coulomb blockade signal. In the three tiles with no data, the sensor did not display clear Coulomb peaks (as shown in a). Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 include the colour-scale bar and voltage values.

Using charge sensing, we demonstrate quantum dots in the few-hole occupation regime, a typical condition for spin-qubit operations. We focus on the occupation of the first dot (D1) that can be directly loaded from the nearby sensing dot, easing the operation. The tuning of dot 2 (D2) in this device was prevented by barrier B2 leaking to ground. We sequentially tune D1 to the few-hole regime in each tile by measuring charge stability diagrams of Ps versus P1 (Fig. 2b) and adjusting voltages in real time, with all other gates grounded during tuning. Overall, we tune D1 to the last hole in 37/40 tiles, with the first transition line approximately centred in each stability diagram. Only three dots failed achieving the last hole due to sensor issues, with tile (4, 23) showing insufficient contrast in sensor Coulomb peaks and tiles (4, 22) and (21, 7) failing to reach Coulomb blockade within the gate-voltage boundaries set for this measurement (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). This failure mode does not affect the operation of other tiles; the other failure modes for this device type are discussed in the Supplementary Discussion.

Electrostatic variability

We investigate the electrostatic variability across the tiles by focusing on lever arms, single-hole voltages and addition voltages related to D1. The distributions of these metrics across different tiles reflect differences in dot shape and position, the uniformity of the semiconductor heterostructure and gate stack, and must be evaluated collectively to account for tile-specific tuning conditions.

Figure 3a shows the distributions of the lever arms of nearby gates (Ps, Bs, S and B1) relative to D1, divided by the lever arm of P1 to D1 (Methods and Supplementary Figs. 4–7)31. As expected from the tile design (Fig. 3a, inset), the chemical potential of D1 is more influenced by the gates closest to the dot plunger (B1 and S) and less by sensor gates (Ps and Bs) in spite of their larger dimensions. Figure 3b shows the distribution of voltages applied to gates within a tile for tuning D1 to the single-hole regime. The distribution for the sensor gates has the largest standard deviation (\({\sigma }_{{P}_{{\rm{s}}}}=86\) mV, \({\sigma }_{{B}_{{\rm{s}}}}=58\) mV) compared with the other gates (for example, \({\sigma }_{{P}_{1}}=38\) mV, \({\sigma }_{{B}_{1}}=36\) mV). This is expected given the manual tuning approach and the typically broad voltage range available for achieving sharp Coulomb peaks that can be used for sensing. To isolate the variability introduced by manual tuning, we calculate the virtual gate voltage vP1 (proportional to the chemical potential of D1; Methods) by summing the contributions of each gate weighted by its relative lever arm. We observe that the distribution width is reduced to \({\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}{P}_{1}}=29\) mV compared with \({\sigma }_{{P}_{1}}=38\) mV. Additionally, we follow the analysis in refs. 15,32 and calculate the standard deviation of the plunger- and barrier-voltage difference σ(P1 − B1) for achieving the first hole. We obtain σ(P1 − B1) = 63 mV, pointing to a uniform disorder potential environment across the device (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a, By analysing statistical data over the 37 functional tiles of a QARPET device such as in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. 4–7, we obtain violin plots of the relative lever arm of all gates with respect to P1. b, Violin plots show the distribution of voltages for the different gates, whereas the last hole is reached in dot 1. We also report the values of virtual P1 (vP1), calculated by adding the contribution of each surrounding gate, weighted by the relative lever arm and normalized by the median value of P1. Although part of the variability of P1 arises from the different voltages applied to the surrounding gates, vP1 accounts for this and, therefore, results in a smaller variability. The variability in vP1 can be used across different crossbar devices as a metric to benchmark, for example, improvements in the uniformity of the Ge/SiGe heterostructure. c, Violin plots show the distribution of the addition voltage for different hole occupations of dot 1. We observe, on average, a larger addition voltage for N = 2 and 6 (red arrows), consistent with the shell filling of circular-hole quantum dots. Black lines in the violin plots denote the minimum, maximum and median of each distribution. The total number of data points in a–c is 112, 112 and 207, respectively.

In Fig. 3c, we investigate the distribution of addition voltages across different tiles for different hole occupations. We observe, on average, a larger addition voltage for occupation with two and six holes (red arrows), consistent with the shell filling of circular-hole quantum dots33 and the absence of low-energy excited states in all the dots34. From the distribution, we note that the variability of addition voltage for each occupation is about 10% of its mean value, which gives an insight into the minimum expected variability of pulse amplitudes required for operating multiple qubits in a device. Comparing the median addition voltage for the first hole (~21 mV) with the distribution of P1 voltages for the first charge transition (Fig. 3b), we estimate that applying the P1 median voltage to different tiles would tune D1 to single-hole occupation in 25% of the cases. This increases to 57% and 75% when targeting occupation up to three and five holes, respectively. Odd charge occupation different than the single hole can be explored for robust and localized qubit control35. These insights provide a concrete benchmark for further materials and process optimization towards shared-control spin-qubit architectures36.

Charge noise

We characterize the charge noise properties of the sensors in the multihole regime using the flank method25,37,38,39. Figure 4a shows the obtained charge noise power spectral density Sϵ as a function of frequency f (Methods), measured at the flank of three neighbouring Coulomb peaks (Fig. 4a, inset) of charge occupation (n − 1), n and (n + 1) to build up statistics. We fit each spectrum with the function S0/fγ to obtain the charge noise \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) at 1 Hz (Fig. 4a, black arrow) and the spectral exponent γ, and iterate this protocol for all tiles under investigation (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). The average γ is close to 1 and is not correlated to \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) (Supplementary Fig. 11), suggesting that the observed 1/f trend results from an ensemble of two-level fluctuators with a wide range of activation energies40,41.

a, Power spectral densities Sϵ from the three measured Coulomb flanks of the charge sensor in tile (4, 16). The spectra are fitted to a S0/fγ dependence (Supplementary Fig. 10). The inset shows the sensor reflectance at ohmic O1 with respect to the sensor plunger Ps, showing three Coulomb peaks with black, grey and light grey circles positioned at their flanks. b, Heat map of \({{S}}_{0}^{1/2}\) from the 40 investigated tiles (row i, column j) within the QARPET device. Each tile in the heat map is partitioned in three to report \({{S}}_{0}^{1/2}\) for increasing charge occupancy Ni,j − 1, Ni,j, Ni,j + 1, corresponding to measurements from subsequent Coulomb flanks. The accompanying histogram shows the overall distribution, made of the total 120 experimental \({{S}}_{0}^{1/2}\) values. c, Voltage power spectral density of dot D1 in tile (4, 16) in the few-hole regime calculated from tracking the transition voltages to charge occupancy N = 1, 2, 3 (Methods). The spectra are fitted to an S0/fγ dependence (Supplementary Fig. 14). The inset shows a 200-s repeated loading of the first hole in D1 by sweeping the plunger P1. The red line shows the estimated position for the N = 0 to N = 1 charge state transition. The transition voltage is then converted to the spectral density (Methods) shown here. d, Similar to b, the heat map of the few-hole regime \({{S}}_{0}^{1/2}\) corresponding to the physical location of each tile within the QARPET device. A faulty RF line prevents fast measurements of the eight connected tiles in row four (Methods). The remaining five tiles with no data are due to sensor drifts that prevented the full 200-s acquisition from being completed in a single run.

For each addressed tile (i, j), the heat map (Fig. 4b) displays the charge noise \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) measured at the three subsequent charge occupations, with the specific charge occupation marginally affecting the noise properties of the device (Supplementary Fig. 12). The overall distribution is shown in the accompanying histogram and is characterized by a spread over more than an order of magnitude, with a geometric mean of 2.4 ± 1.7 μeV Hz−1/2. This experimental mean matches closely the bootstrapped mean (Supplementary Fig. 13), indicating that our sample size is sufficiently large to provide confidence in the accuracy of the mean value. From the heat map, we identify a noisier device region in the bottom-left quadrant, i ∈ {19, 21}, j ∈ {14, 16}, as well as the best-performing tile, indexed (17, 21), with an average charge noise \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) of 0.7 ± 0.24 μeV Hz−1/2 and a minimum of 0.36 μeV Hz−1/2.

We complement the charge noise analysis by characterizing quantum dot D1 under P1 in the few-hole regime, which is the typical regime of operation for qubits. Figure 4c shows the frequency dependence of the voltage spectral density for the first three hole transitions. Following the methodology in ref. 42, these spectra are evaluated from the time traces of the transition voltages (Fig. 4c, inset) obtained by sweeping across the charge transition region over a fixed time. As shown in Fig. 4a, we fit each spectrum to S0/fγ to obtain the charge noise \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) at 1 Hz (Fig. 4c, black arrow) and the spectral exponent γ, and extend this protocol to all measurable tiles (Supplementary Fig. 14). The resulting heat map in Fig. 4d displays the charge noise values \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) measured at the three subsequent charge transitions, with the accompanying histogram showing the overall distribution. The distribution is characterized by a geometric mean value \({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\) of 52 ± 31 μV Hz−1/2. The average charge noise is marginally affected by the specific hole filling, but rather the standard deviation decreases with increasing hole occupancy (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Our statistical characterization enables a comparison with charge noise measurements in quantum dot devices using a higher-quality Ge/SiGe heterostructure grown on a Ge substrate42. We observe charge noise values an order of magnitude higher than in ref. 42 for both charge sensors (Supplementary Fig. 15) in the multihole regime and dots in the few-hole regime. These results support the understanding from ref. 42 that charge noise in Ge/SiGe heterostructures grown on Ge wafers may be lower than in those grown on Si wafers. The fabrication of QARPET devices on Ge/SiGe heterostructures grown on Ge wafers will improve the statistical assessments of charge noise uniformity over larger areas.

Qubits

Last, we focus on a single tile of a second QARPET device with a functional interdot barrier and demonstrate the ability to encode ST and LD spin qubits in the crossbar. Figure 5a shows the charge stability diagram of the double dot (D1, D2) obtained by sweeping the detuning ε12 and chemical potential axes μ12. For ST qubits, we define the detuning of the two dots ε12 to be zero at the centre of the (1, 1) charge region and perform a spin funnel experiment. Starting from the (0, 2) region, we pulse the system towards the (1, 1) region at varying detunings ε12, we let it evolve for 100 ns and pulse back to the read-out point (Fig. 5a, red dot). We do this for varying magnetic fields (B) to map the S–T− anticrossing as a function of B (dark blue line)43, which confirms the ability to read-out spins using the Pauli spin blockade method.

a, Charge stability diagram of dot 1 and dot 2 measured on tile (19, 14) from a second QARPET device, showing the sensor reflectance VR as a function of detuning ε12 and chemical potential μ12 of the double quantum dot. The red dot indicates the read-out point inside the Pauli spin blockade window, the black dot shows the manipulation point and the white arrows represent the pulse sequence from initialization to manipulation and read-out. The gate voltages at the centre of the (1, 1) region correspond to Ps = −1,169.6 mV, Bs = −501.9 mV, P1 = −663.6 mV, P2 = −688.7 mV, B1 = −385.0 mV, B2 = −320.0 mV and S = −146.5 mV. b, Experimental results for spin funnel, showing the singlet probability PS as a function of ε12 and applied magnetic field B. The applied magnetic field is nominally parallel to the device plane. The system is initialized in a singlet, pulsed from the (0, 2) region towards the (1, 1) region in 1 μs at varying ε12 values, left evolving for 100 ns and pulsed to the read-out point in 1 ns. c, Experimental results for ST0 oscillations, showing PS as a function of ε12 and varying times τ. At B = 20 mT, the system is initialized in a singlet, pulsed from the (0, 2) region towards the (1, 1) region in 1 ns, left evolving for varying times τ and pulsed to the read-out point in 1 ns. This sequence is repeated for different ε12 values. d, Experimental results for ST0 oscillations, showing PS as a function of B and τ. The system is initialized in a singlet, pulsed from (0, 2) to the manipulation point in 1 ns and left evolving for varying times τ, and pulsed to the read-out point in 1 ns. This sequence is repeated for different magnetic fields.

Figure 5c,d demonstrates coherent ST0 oscillations as a function of detuning, magnetic field and evolution time. We initialize a singlet in the (0, 2) configuration, diabatically pulse towards (1, 1), let evolve for a time τ and diabatically pulse to the read-out point. This sequence is repeated for different τ values, for different detunings (Fig. 5c) and different magnetic fields (Fig. 5d). From fitting the oscillation frequency as a function of the magnetic field (Supplementary Fig. 15), we estimate the g-factor difference Δg = 0.0734 ± 0.0001 and the residual exchange at zero detuning J(ε12 = 0) = 3.736 ± 0.112 MHz.

We measure the electric-dipole spin resonance spectra of the two single-hole spin LD qubits Q1 and Q2 (Fig. 6a) by starting with a singlet in the (0, 2) configuration, pulsing slowly towards the (1, 1), applying a microwave (MW) pulse to plunger P1/P2 (top/bottom panel) at frequency f and pulsing to the read-out point. A dark blue line is visible where the MW driving frequency is at resonance with the qubit. At zero detuning, that is, at the centre of the (1, 1) region, the g-factors for the two qubits result in g1 = 0.30 and g2 = 0.36 (in line with the values reported for the same heterostructure in ref. 26 and with other works on Ge (refs. 27,44)). The difference in these g-factors is also consistent with Δg = 0.073 extracted from the ST qubit experiment shown in Fig. 5b.

a, Electric-dipole spin resonance spectra of qubits Q1 (top) and Q2 (bottom), showing the singlet probability PS as a function of detuning (ϵ12) and MW pulse frequency f. Starting from the (0, 2) configuration, we pulse in 10 μs towards (1, 1) at varying detunings ε12, apply a MW pulse with frequency f and pulse diabatically to the read-out point. At zero detuning, the g-factors of the two qubits are g1 = 0.30 and g2 = 0.3. A higher value in the colour bar represents a higher singlet probability. b, Ramsey experiment of qubits Q1 (top) and Q2 (bottom), showing the spin-down probability P↓ as a function of the waiting time τ between two π/2 pulses. Fitting of the results with \(P=a\cos (2\mathrm{\pi \varDelta }f\tau +\phi )\exp (-{(\tau /{T}_{2}^{* })}^{{\alpha }^{* }})\) yields \({T}_{2}^{* }\) values of (4.43 ± 0.13) μs and (5.75 ± 0.19) μs for Q1 and Q2, respectively. c, Hahn-echo experiment of qubits Q1 (top) and Q2 (bottom), showing the spin-down probability P↓ as a function of waiting time τ. The pulse sequence consists of π/2, π and π/2 pulses, separated by waiting time τ. Fitting the results with \(P=a\exp (-{(2\tau /{T}_{2}^{{\rm{H}}})}^{{\alpha }^{{\rm{H}}}})\) yields \({T}_{2}^{{\rm{H}}}\) values of (10.11 ± 0.42) μs and (12.69 ± 0.40) μs for Q1 and Q2, respectively. Initialization is performed pulsing deep in (0, 2) and waiting for 100 μs for the system to relax into the singlet. All the measurements are performed at a magnetic field of 50 mT, oriented parallel to the device.

After calibrating the π/2 qubit rotations, we characterize the qubits’ coherence in this system. We perform a Ramsey experiment (Fig. 6b) on both qubits at a magnetic field of 50 mT and extract coherence times \({T}_{2}^{* }\) of (4.43 ± 0.13) μs and (5.75 ± 0.19) μs for Q1 and Q2, respectively. These coherence times are comparable with the best results measured in Ge at a similar magnetic field28. Further, we perform a Hahn-echo experiment (Fig. 6c) and extract coherence times \({T}_{2}^{{\rm{H}}}\) of (10.11 ± 0.42) μs and (12.69 ± 0.40) μs for Q1 and Q2, respectively, comparable with previous experiments28 (note that in ref. 28, \({T}_{2}^{H}\) of 32 μs is measured at 25 mT where coherence is expected to be longer compared with our field of 50 mT). This proof-of-principle demonstration further motivates the use of QARPET devices for a statistical characterization of qubit coherence and is encouraging for scaling quantum processors in dense Ge qubit arrays.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the key functionalities of our QARPET architecture at millikelvin temperature using RF reflectometry, including tile selectivity, single-hole quantum dots, ST and single-spin LD qubits. We reported statistics on single-hole and addition voltages, providing insights into the uniformity of gate-defined quantum confinement in our device architecture; this is relevant for the operations of hole spin qubits45,46 and for developing shared-control spin-qubit architectures36. Our systematic exploration of charge noise highlights the potential of the architecture as a tool for statistical benchmarking. The approach could, in particular, provide the statistical analysis of spin qubits within a single cooldown and across micrometre-scale length scales, which is relevant for noisy intermediate-scale quantum processors. The integration of autonomous, machine learning-assisted routines for efficient tuning, read-out and control of spin qubits47 will be a key step in this direction.

QARPET is a flexible platform and has the potential for further optimization in both design and implementation. The current design features two quantum dots per tile for charge and spin manipulation, but this number could be extended to q > 2, requiring a linear increase in control lines (n + m + 2q + 3) to operate q × n × m qubits, thereby maintaining a sublinear scaling of interconnects. The specific properties of the heterostructure, such as the SiGe barrier thickness, also influence the dimensions of the plunger and barrier gates, thereby setting the minimum tile footprint and determining the overall qubit density of the device.

Although demonstrated in a Ge/SiGe heterostructure, the QARPET architecture could be adapted to other accumulation-mode undoped heterostructures with appropriate design and process modifications. However, such adaptations may introduce additional challenges. For instance, implementing QARPET in Si/SiGe heterostructures would require narrower gates due to the heavier electron mass compared with holes in strained Ge, as well as additional accumulation gate layers to connect charge sensors to remote doped reservoirs.

With hundreds of nominally identical quantum dot qubits integrated in a single die, QARPET could be used as a test bed for the training of automated routines for all phases of device tuning, from quantum dot read-out to single-spin operation, as well as exploring the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence48,49. The implementation of testing platforms like QARPET with advanced semiconductor manufacturing could also reduce device variability and could accelerate the development cycle of industrial spin qubits. Furthermore, due to the dense pattern of multilayer gates, QARPET-like devices may provide the benchmarking of spin-qubit performance in a practically relevant electrostatic environment and could, thus, assist in the development of large-scale quantum processors.

Methods

Ge/SiGe heterostructure growth

The Ge/SiGe heterostructure is grown on a 100-mm n-type Si(001) substrate using an Epsilon 2000 (ASMI) reduced-pressure chemical vapour deposition reactor. The layer sequence comprises a Si0.2Ge0.8 virtual substrate obtained by reverse grading, a 16-nm-thick Ge quantum well, a 55-nm-thick Si0.2Ge0.8 barrier and a thin sacrificial Si cap. Further details and electrical characterization of Hall-bar-shaped heterostructure field-effect transistors on this semiconductor stack are presented in ref. 25.

Device fabrication

The fabrication of QARPET devices entails the following steps: electron-beam lithography of the ohmic contacts layer; wet etching of the sacrificial Si cap in buffer oxide etch for 10 s; deposition of the ohmic contacts via electron-gun evaporation of 15 nm of Pt at a pressure of 3 × 10−6 mbar at the rate of 3 nm min−1, followed by rapid thermal annealing at 400 °C for 15 min in a halogen-lamps-heated chamber in an argon atmosphere to form PtSiGe ohmic contacts50; atomic layer deposition of 5 nm of \({{{\rm{Al}}}_{2}{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) at 300 °C; electron-beam lithography and deposition of the first gate layer via electron-gun evaporation of 3 nm of Ti and 17 nm of Pd; lift-off in AR600-71 at 45 °C with sonication at medium–high power for 1 h, and the patterned side of the chip facing downwards to avoid redeposition of metal on the chip surface. For each subsequent gate layer, the last two steps are repeated, increasing the deposited Pd thickness each time by 5 nm to guarantee film continuity at the location of overlap with the first gate layer. We perform atomic force microscopy imaging of the developed resist after each resist development and metal lift-off to monitor the fabrication process.

Measurements

Device 1 was screened for leakage at 4.2 K before millikelvin measurements (Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the yield details). Possible failure modes for this architecture are described in the Supplementary Discussion. All measurements are performed in an Oxford wet-dilution refrigerator with a base temperature of ~100 mK. Using battery-powered voltage sources, d.c. voltages are applied to the gates. The d.c. voltages on gates are combined with an a.c. voltage from a Qblox arbitrary waveform generator by a bias-tee with a cut-off frequency of 3 Hz. The a.c. voltage used for pulses and RF driving is generated by an arbitrary waveform generator. We studied two devices. Measurements and the corresponding analyses reported in Figs. 2–4 and Supplementary Figs. 1–15 are from QARPET device 1. The interdot barrier B2 was leaky, preventing double-dot studies on this specific device and the RF line connected for i = 4 was faulty, preventing, on this row, the fast 2D maps of P1 versus other gates. In QARPET device 2, we focused on a single tile with measurements and the corresponding analysis reported in Figs. 5 and 6 and Supplementary Fig. 16. The magnetic field is applied via a one-axis solenoid magnet that is nominally parallel to the device plane.

Relative lever arm calculation

The relative lever arms to D1 with respect to P1 (Fig. 3a) are derived from the slopes of the transition lines in the reflectance maps of all P1-to-surrounding-gates pairs31 for all the tiles in which it was measurable (Supplementary Figs. 4–7). The slope of the transition lines in these gate–P1 maps allows to extract the lever arm of gate gi to D1 relative to the lever arm of P1 to D1 (\({\alpha }_{{g}_{i},{D}_{1}}/{\alpha }_{{P}_{1},{D}_{1}}\)) (ref. 31). The variability of the relative lever arms across different spin-qubit tiles arises form differences in the shape and position of dot D1, which depends on the electrostatic potential surrounding the dot and reflects the variability in the semiconductor-stack and gate-stack uniformity, as well as differences in electrostatic tuning of the tile. The virtual gate voltage vP1 is calculated as uP1 ⋅ median(P1)/median(uP1), where \(\,{\rm{u}}{P}_{1}=\sum {g}_{i}{\alpha }_{{g}_{i},{D}_{1}}/{\alpha }_{{P}_{1},{D}_{1}}\), with gi comprising Ps, Bs, B1, P1 and S.

Flank method for charge noise characterization of quantum dots in multihole regime

We characterize charge noise of the sensors using the flank method, measured via RF reflectometry. The process begins by tuning the surrounding gates until the reflected signal exceeds the baseline by at least 10 mV, marking the turn on of the device. A multihole quantum dot is then defined beneath Ps by gradually lowering the barrier gates surrounding Ps until a spectrum of Coulomb peaks is observed without any background signal. Next, we record the reflected signal on the right flank of the first three Coulomb peaks, where the slope (∣dI/dVsd∣) of the peaks is the steepest. The signal is sampled at a rate of 1 kHz for a duration of 100 s using a Qblox digitizer. To compute the current power spectral density SI, the 100-s current trace is divided into ten 10-s segments. The power spectral densities for each segment are calculated and averaged to yield SI. For each Coulomb peak analysed, we convert SI into the charge noise power spectral density (Sϵ) using

where α is the lever arm extracted from the analysis of the Coulomb diamonds (Supplementary Fig. 9). Finally, the spectral densities are fitted to a 1/fγ model and the value of the spectral density at 1 Hz (\({{S}}_{{\rm{0}}}^{1/2}\)) and exponent (γ) are extracted and reported.

Charge transition method for charge noise characterization of quantum dots in few-hole regime

We begin by tuning P1 to the last hole, as described previously. To probe electrostatic fluctuations in the quantum dot, we repeatedly sweep across the charge transition point over a period of 200 s at a rate of 300 Hz. Transition voltages are extracted by performing a sigmoid fit to each sweep repetition42. From the transition-voltage data, we calculate the voltage spectral density and fit the results to a 1/fγ dependence, reporting the noise value at 1 Hz and the spectral exponent. Because we use the sensor to monitor the transition voltage, the measurements include noise contributions from both Ps and P1. However, we find that the spectral density of the sensor is an order of magnitude lower than the spectral densities measured for P1. This confirms that the observed traces are dominated by charge noise from the quantum dot under P1 (ref. 42).

Data availability

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are available via Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/15089359 (ref. 51).

References

Burkard, G., Ladd, T. D., Pan, A., Nichol, J. M. & Petta, J. R. Semiconductor spin qubits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 025003 (2023).

Zwerver, A. et al. Qubits made by advanced semiconductor manufacturing. Nat. Electron. 5, 184–190 (2022).

De Leon, N. P. et al. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 372, eabb2823 (2021).

Saraiva, A. et al. Materials for silicon quantum dots and their impact on electron spin qubits. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2105488 (2022).

Ward, D. R., Savage, D. E., Lagally, M. G., Coppersmith, S. N. & Eriksson, M. A. Integration of on-chip field-effect transistor switches with dopantless Si/SiGe quantum dots for high-throughput testing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 213107 (2013).

Al-Taie, H. et al. Cryogenic on-chip multiplexer for the study of quantum transport in 256 split-gate devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 243102 (2013).

Puddy, R. K. et al. Multiplexed charge-locking device for large arrays of quantum devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 143501 (2015).

Schaal, S. et al. A CMOS dynamic random access architecture for radio-frequency readout of quantum devices. Nat. Electron. 2, 236–242 (2019).

Paquelet Wuetz, B. et al. Multiplexed quantum transport using commercial off-the-shelf CMOS at sub-kelvin temperatures. npj Quantum Inf. 6, 43 (2020).

Pauka, S. J. et al. Characterizing quantum devices at scale with custom cryo-CMOS. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 054072 (2020).

Ruffino, A. et al. A cryo-CMOS chip that integrates silicon quantum dots and multiplexed dispersive readout electronics. Nat. Electron. 5, 53–59 (2021).

Bavdaz, P. L. et al. A quantum dot crossbar with sublinear scaling of interconnects at cryogenic temperature. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 86 (2022).

Wolfe, M. A. et al. On-chip cryogenic multiplexing of Si/SiGe quantum devices. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2410.13721 (2024).

Thomas, E. J. et al. Rapid cryogenic characterization of 1,024 integrated silicon quantum dot devices. Nat. Electron. 8, 75–83 (2025).

Neyens, S. et al. Probing single electrons across 300-mm spin qubit wafers. Nature 629, 80–85 (2024).

Pelgrom, M. J. M., Duinmaijer, A. C. J. & Welbers, A. P. G. Matching properties of MOS transistors. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 24, 1433–1439 (1989).

Ohkawa, S., Aoki, M. & Masuda, H. Analysis and characterization of device variations in an LSI chip using an integrated device matrix array. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 17, 155–165 (2004).

Tsunomura, T., Nishida, A. & Hiramoto, T. Analysis of NMOS and PMOS difference in Vt variation with large-scale DMA-TEG. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 56, 2073–2080 (2009).

Mizutani, T., Kumar, A. & Hiramoto, T. Measuring threshold voltage variability of 10G transistors. In Proc. International Electron Devices Meeting 25.2.1–25.2.4 (IEEE, 2011).

Scappucci, G. et al. The germanium quantum information route. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 926–943 (2021).

Veldhorst, M., Eenink, H. G. J., Yang, C. H. & Dzurak, A. S. Silicon CMOS architecture for a spin-based quantum computer. Nat. Commun. 8, 1766 (2017).

Li, R. et al. A crossbar network for silicon quantum dot qubits. Sci. Adv. 4, 3960 (2018).

Landman, B. S. & Russo, R. L. On a pin versus block relationship for partitions of logic graphs. IEEE Trans. Computers C-20, 1469–1479 (1971).

Franke, D. P., Clarke, J. S., Vandersypen, L. M. K. & Veldhorst, M. Rent’s rule and extensibility in quantum computing. Microprocess. Microsyst. 67, 1–7 (2019).

Lodari, M. et al. Low percolation density and charge noise with holes in germanium. Mater. Quantum Technol. 1, 011002 (2021).

Hendrickx, N. W. et al. A single-hole spin qubit. Nat. Commun. 11, 3478 (2020).

Hendrickx, N. et al. Sweet-spot operation of a germanium hole spin qubit with highly anisotropic noise sensitivity. Nat. Mater. 23, 920–927 (2024).

Wang, C.-A. et al. Operating semiconductor quantum processors with hopping spins. Science 385, 447–452 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Universal control of four singlet–triplet qubits. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 209–215 (2025).

Stehouwer, L. E. A. et al. Germanium wafers for strained quantum wells with low disorder. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 092101 (2023).

Tidjani, H. et al. Vertical gate-defined double quantum dot in a strained germanium double quantum well. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 054035 (2023).

Ha, W. et al. A flexible design platform for Si/SiGe exchange-only qubits with low disorder. Nano Lett. 22, 1443–1448 (2022).

van Riggelen, F. et al. A two-dimensional array of single-hole quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 044002 (2021).

Lim, W. H., Yang, C. H., Zwanenburg, F. A. & Dzurak, A. S. Spin filling of valley-orbit states in a silicon quantum dot. Nanotechnology 22, 335704 (2011).

John, V. et al. Robust and localised control of a 10-spin qubit array in germanium. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-65577-3 (2025).

Borsoi, F. et al. Shared control of a 16 semiconductor quantum dot crossbar array. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 21–27 (2024).

Connors, E. J., Nelson, J., Qiao, H., Edge, L. F. & Nichol, J. M. Low-frequency charge noise in Si/SiGe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 100, 165305 (2019).

Paquelet Wuetz, B. et al. Reducing charge noise in quantum dots by using thin silicon quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 14, 1385 (2023).

Massai, L. et al. Impact of interface traps on charge noise and low-density transport properties in Ge/SiGe heterostructures. Commun. Mater. 5, 151 (2024).

Paladino, E., Galperin, Y., Falci, G. & Altshuler, B. 1/f noise: implications for solid-state quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 361 (2014).

Elsayed, A. et al. Low charge noise quantum dots with industrial CMOS manufacturing. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 70 (2024).

Stehouwer, L. E. A. et al. Exploiting strained epitaxial germanium for scaling low-noise spin qubits at the micrometre scale. Nat. Mater. 24, 1906–1912 (2025).

Jirovec, D. et al. A singlet-triplet hole spin qubit in planar Ge. Nat. Mater. 20, 1106–1112 (2021).

Jirovec, D. et al. Dynamics of hole singlet-triplet qubits with large g-factor differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 126803 (2022).

Bosco, S., Benito, M., Adelsberger, C. & Loss, D. Squeezed hole spin qubits in Ge quantum dots with ultrafast gates at low power. Phys. Rev. B 104, 190501 (2021).

Malkoc, O., Stano, P. & Loss, D. Optimal geometry of lateral GaAs and Si/SiGe quantum dots for electrical control of spin qubits. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235413 (2016).

Carlsson, C. et al. Automated all-RF tuning for spin qubit readout and control. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.10834 (2025).

Zwolak, J. P. et al. Data needs and challenges for quantum dot devices automation. npj Quantum Inf. 10, 105 (2024).

Alexeev, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence for quantum computing. Nat. Commun. 16, 10829 (2025).

Tosato, A. et al. Hard superconducting gap in germanium. Commun. Mater. 4, 23 (2023).

Tosato, A. Data underlying the publication: QARPET: a qubit- array research platform for engineering and testing. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15089359 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to F. Borsoi, P. C. Fariña, H. Tidjani, S. Philips and D. Jirovec for fruitful discussions. G.S. and A.E. acknowledge support from the European Union through the IGNITE project (grant number 101069515). D.D.E. acknowledges support from the European Union through the QLSI project (grant number 951852). D.C. acknowledges support from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO/OCW), via the Open Competition Domain Science—M program. K.H. acknowledges the research programme Materials for the Quantum Age (QuMat) for financial support. This programme (registration number 024.005.006) is part of the Gravitation programme financed by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW). This research was sponsored in part by the Army Research Office (ARO) under award number W911NF-23-1-0110. The views, conclusions and recommendations contained in this document are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed nor should they be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office (ARO) or the US government. The US government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein. This research was sponsored in part by The Netherlands Ministry of Defence under award number QuBits R23/009. The views, conclusions and recommendations contained in this document are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed nor should they be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of The Netherlands Ministry of Defence. The Netherlands Ministry of Defence is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. designed and fabricated the devices on heterostructures provided by L.S., with contributions from D.C. to packaging, from K.L.H. to device inspection and from D.D.E. for process development. A.T. assembled the setup and fridge, performed the quantum dot and qubit measurements, and analysed the corresponding data. A.E. and F.P. performed the noise measurements, analysed with help from L.E.A.S. and D.D.E. A.T., A.E. and G.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. G.S. and A.T. conceived the project, supervised by G.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.S. and A.T. are inventors on a patent application (international application number PCT/NL2024/050325) submitted by Delft University of Technology related to the QARPET architecture. G.S. is founding advisor of Groove Quantum BV and declares equity interests. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Electronics thanks Gang Cao and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–16 and Discussion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tosato, A., Elsayed, A., Poggiali, F. et al. A crossbar chip for benchmarking semiconductor spin qubits. Nat Electron (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-026-01569-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-026-01569-5