Abstract

Organocatalysed photoredox-mediated atom transfer radical polymerization (O-ATRP) is a very promising polymerization method as it eliminates concerns associated with transition-metal contamination of polymer products. However, reducing the amount of catalyst and expanding the monomer scope remain major challenges in O-ATRP. Herein, we report a systematic computer-aided-design strategy to identify powerful visible-light photoredox catalysts for O-ATRP. One of our discovered organic photoredox catalysts controls the polymerization of methyl methacrylate at sub-ppm catalyst loadings (0.5 ppm—a very meaningful amount enabling the direct use of polymers without a catalyst removal process); that is, 100–1,000 times lower loadings than other organic photoredox catalysts reported so far. Another organic photoredox catalyst with supra-reducing power in an excited state and high redox stability facilitates the challenging polymerization of the non-acrylic monomer styrene, which is not successful using existing photoredox catalysts. This work provides access to diverse challenging organic/polymer syntheses and makes O-ATRP viable for many industrial and biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) is the most powerful technique for producing well-defined polymers for a variety of industrial applications that include coatings, adhesives, cosmetics, inkjet printing, detergents, paints and surfactants, with an estimated commercial value exceeding US$20 billion1. However, ATRP often suffers from transition-metal catalyst residues remaining in the polymers. Reducing the transition-metal residues in the final polymers requires the use of ion-exchange resins and absorbents, which increases the process cost. Moreover, complete removal of this transition metal is necessary for certain applications involving microelectronics and biomaterials2.

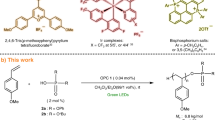

Organocatalysed photoredox-mediated ATRP (O-ATRP) offers an attractive variant to traditional ATRP as it eliminates concerns associated with transition-metal contamination of polymer products3,4,5,6. Hawker and co-workers7 and Matyjaszewski and co-workers8 first demonstrated that phenylphenothiazine analogues are effective organic photoredox catalysts (OPCs) for the O-ATRP of methyl methacrylate (MMA) and its analogues at catalyst loadings of 1,000 ppm (with respect to the monomer) under ultraviolet-light irradiation conditions. Further advances were recently made by Miyake and co-workers9,10,11,12,13 wherein diaryldihydrophenazine and phenoxazine analogues were proposed as OPCs and achieved successful control over the polymerization of acrylic monomers with lower catalyst loadings (at least 200 ppm) under visible-light irradiation. Despite these advances, the reaction scope is still limited to a few acrylic monomers, and high catalyst loadings (commonly 100–1,000 ppm) are required to control polymerization3,4,5,6. In particular, since high catalyst loading requires additional purification processes, such as catalyst removal and recycling, reducing the amount of catalyst to less than 1 ppm for O-ATRP is crucial for the direct use of polymers for most applications.

The discovery of new OPCs is key to overcoming the challenges in O-ATRP. To reduce catalyst loadings, OPCs that strongly absorb visible light and efficiently generate long-lived triplet excitons are required. To successfully polymerize non-acrylic monomers (for example, styrene and vinyl acetate), a photoredox catalyst should exhibit high reducing power in its excited state in order to access unactivated alkyl halides, along with an appropriate ground-state oxidation potential for the effective reduction of its radical cation. In addition, high redox stability is needed since the propagation of some non-acrylic monomers such as styrene is slow and, consequently, long reaction times and rather harsh reaction conditions are required. However, to date, no general guideline on the discovery of OPCs that satisfy all these requirements exists, although a few novel OPCs have recently been proposed14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. As shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 1, these OPCs mostly rely on specific functional groups, and the catalyst properties are only tuned in rather small ranges. We envisaged that a concise yet general strategy based on a molecular platform capable of generating large numbers of OPC candidates, whose catalyst parameters can be systematically controlled over broad ranges, would facilitate the discovery of such OPCs.

Here, we report a systematic computer-aided-design strategy for the discovery of highly efficient OPCs that addresses important challenges in O-ATRP. This design strategy was also validated by in-depth experimental studies. We found that a strongly twisted donor–acceptor (D–A) scaffold can be used to discover novel OPCs. Here, the strong charge-transfer character of the lowest singlet excited states (S1) is a key factor to effectively populate the lowest triplet excited states (T1) and systematically control the essential catalyst parameters over broad ranges. Based on this concept, we provide a flow chart that facilitates the rational design of OPCs. With such a strategy, remarkably efficient and powerful visible-light-absorbing OPCs, including ultra-low catalyst loading (0.5 ppm) and styrene polymerization, were discovered.

Results

Design strategy

The population of T1 plays an essential role in photoredox-mediated reactions, since T1 exhibits a lifetime sufficiently long to ensure efficient photoinduced electron transfer (PET); moreover, T1 is expected to be less susceptible to back electron transfer (BET) between radical ion pairs25,26,27. However, in most purely organic compounds, the intersystem crossing (ISC) from S1 to their triplet manifolds (Tn) is slow due to inefficient spin–orbit coupling (SOC). Consequently, the population of T1 via ISC is dominated by competing relaxation pathways28.

In some special organic molecules, ISC is strongly enhanced by small energy gaps between the S1 state and accepting triplet state (Tac) being an essential ingredient in efficient ISC via SOC29,30,31,32,33. ISC via SOC requires either a heavy atom effect or orthogonality between the S1 and Tac wave functions; such (partial) orthogonality can be realized either by 3,1(nπ*) ↔ 1,3(ππ*) transitions or transitions between charge-transfer (CT) and localized ππ*-type states (3,1(ππ*)CT ↔ 1,3(ππ*)loc) in a somewhat wider definition of the El-Sayed rules34,35,36,37. In this regard, to efficiently generate T1 states in organic molecules, we expect that molecules having directly connected donor and acceptor groups with a twisted geometry and strong charge-transfer character of S1 are good candidates for OPCs, as they could fulfil both small energy gap and orthogonality criteria (Fig. 1a). In fact, such a design was successfully employed for thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters used in organic light-emitting diodes. Strongly twisted D–A structures with a large molecular orbital offset between donor and acceptor moieties lead to minimal overlap between the HOMO and LUMO, thereby minimizing the exchange energy, resulting in a small singlet–triplet energy gap (ΔEST)38,39 (for a discussion of the various electronic and steric factors, see ref. 39).

a, Calculated HOMO and LUMO topologies (left) and energies (middle) of 6f built from fragment molecular orbitals, and a Jablonski diagram of strongly twisted D–A compounds (right). D, donor; A, acceptor; LE, locally excited; CT, charge transfer; HSO, spin-orbit Hamiltonian; ΦISC, the quantum yield of intersystem crossing; δ, first-order mixing coefficient between singlet and triplet states; 3Ψ, triplet wavefunctions; 1Ψ, singlet wavefunctions; IC, internal conversion; FL, fluorescence; PH, phosphorescence. b, Tuning principle of light absorption and redox potentials of ground and excited states in the molecular platform exemplified by 6f. The strong charge-transfer character of S1 is a key factor for systematically controlling these parameters. The HOMO–LUMO gap can be altered by changing the D and A groups. The oxidation and reduction potentials of the ground state are controlled independently by adjusting D and A, respectively, whereas those of the excited state are changed by adjusting A and D, respectively. EA, electron affinity; IP, ionization potential. c, Control of the stability of radical ions. The radical cations and anions are stabilized by elevating HOMO and lowering LUMO energies, respectively. Inset, electrostatic potential maps of 6f·+ and 6f·‒. d, Oxidative and reductive quenching cycles of photoredox catalysts (PCs). Upon photoexcitation, the PCs can engage in PET processes, which consequently generates highly reactive radical intermediates from a variety of stable substrates. For closed photoredox catalytic cycle, a subsequent electron transfer regenerates the ground-state PCs. The proper thermodynamics and kinetics for each PET or other electron transfer process are required for the reactions to proceed successfully. Sub, substrate; hv, photon energy. e, Flow chart for the design of OPCs (see the section ‘Flow chart’ in the Methods). ΔGET, Gibbs free energy change for the electron transfer reaction; kET, bimolecular rate constant for electron transfer; Ere, reorganization energy; CV, cyclic voltametry; PL, photoluminescence spectroscopy; QC, quantum chemical.

In any case, OPCs require a few other crucial parameters for high catalytic activity, such as effective light absorption, proper ground- and excited-state redox potentials, reorganization energies and stability of radical ions25,26,27. In fact, ground- and excited-state redox potentials and reorganization energies are very important factors that determine the thermodynamics and/or kinetics of PET and other electron transfer processes (Supplementary Note 1). The stability of the catalysts’ radical ions is also a key parameter, as unstable ions can promote undesirable side reactions and limit the deactivation process in the catalyst cycle. Systematic control of these parameters over a broad range could enable tailored design of catalysts to facilitate the development of new photoredox-mediated reactions. Specifically, the unique intramolecular charge-transfer character of the S1 state in the chosen molecular platform will allow systematic control of these parameters, as HOMO and LUMO can be independently controlled by adjusting the donor and acceptor moieties (Fig. 1b–d).

According to the hypothesis outlined above, a flow chart for the rational design of OPCs is provided in Fig. 1e (see the section ‘Flow chart’ in the Methods for details). Next, we prepared a series of organic molecules as potent OPCs (Fig. 2); among many candidates, we have chosen appropriate donor and acceptor moieties by considering the electron-donating and -accepting ability and synthesis feasibility. Although we prepared 31 molecules, in principle an almost infinite number of molecules can be generated by various combinations of donor and acceptor groups and their arrangements40. A full description of the synthetic approaches, as well as 1H{13C} NMR and mass spectrometric characterizations, are provided in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figs. 44–84.

A series of OPCs is presented, based on the molecular platform of a strongly twisted D–A group. Eleven different acceptor groups were used in combination with six different donor groups (a–f). It should be noted that the OPCs prepared here contain many known compounds, which are mostly used for dopants and host materials of organic LEDs. We properly cite these compounds in the Supplementary Methods.

Experimental validation of the design strategy

We first experimentally obtained adiabatic S1 energies, E00(S1), from the onset of the photoluminescence at 77 K for all molecules and compared them with the corresponding vertical S1 energies (Evert) calculated by time-dependent density functional theory (DFT) to analyse the electronic character of S1 (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). We chose dimethylformamide (DMF) as the solvent as it is most commonly used for photoredox-mediated reactions. The calculated S1 energies reproduced the experimental trends very well. For the vast majority of the molecules, S1 is described by a simple, almost exclusive HOMO → LUMO excitation. According to the DFT results, the HOMOs (LUMOs) are indeed primarily localized in the donor (acceptor) moieties, as exemplified in Fig. 1a; this implies a strong intramolecular charge-transfer character of S1 (for the whole set of molecular orbital topologies, see Supplementary Figs. 35–41, which also prove the strongly twisted geometries of the compounds).

a, Measured (filled diamonds; exp.) and calculated (empty diamonds; calc.) E00(S1), E00(T1) and ΔEST of OPCs. Most of the molecules show an ΔEST value of ~0.2 eV, facilitating ISC and thus promoting efficient T1 generation. Experimental energies of S1 and T1 were measured from photoluminescence onset at 77 K. Vertical energies calculated by DFT were used as theoretical values. Compounds showing no fluorescence (FL), no phosphorescence (PH) or faint PH are indicated by green, red and open red stars, respectively. b,c, Measured (filled diamonds) and calculated (empty diamonds) E00(S1), \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) and \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\) of 6a–f (b) and 1b–11b (c) are plotted in grey, green and red, respectively. A pink circle indicates irreversibility of the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curve. d,e, Measured (filled diamonds) and calculated (empty diamonds) \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast\) and \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^ \ast\) of 6a–f (d) and 1b–11b (e) are plotted in green and red, respectively. Calculated HOMO (LUMO) energies of fragment donor (acceptor) groups are shown in panels b and d (c and e). Values for E00(S1) − 7 eV in b and c are plotted as a visual aid (grey lines) for better comparison with HOMO and LUMO. All energy values (for HOMO, LUMO and E00(S1)) should be read using the scale on the right-hand y axis, as indicated by the arrow in b.

We then investigated the ability of triplet exciton generation of all compounds by gated photoluminescence spectroscopy at 77 K. As expected, most molecules showed noticeable phosphorescence (being indicative of triplet exciton generation), whereas a few molecules exhibited no phosphorescence (5c, 5d, 5e, 7b and 8b) or very faint phosphorescence (5a and 6d) (Fig. 3a). To confirm the origin of efficient T1 generation, the ΔEST values of molecules were evaluated from their spectral onsets; that is, ΔEST = E00(S1) – E00(T1) (Supplementary Note 3). In general, the experimental singlet–triplet energy gaps were quite well reproduced by time-dependent DFT, obtained from vertical ΔEST in DMF (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3), in agreement with previous results on thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials38,39. As stated above, S1 is described by almost exclusive HOMO → LUMO excitation; however, large variations of the charge-transfer character are found, which can be quantified through the oscillator strength f1, taking values between 0 and 1. The amount of charge transfer in S1 largely determines ΔEST as the character of T1 corresponds to that of S1 in most cases; hence, a reasonable correlation between f1 and ΔEST is observed (see Supplementary Fig. 12). Most molecules in the library indeed exhibit relatively small ΔEST values (~0.2 eV), facilitating ISC and thus promoting efficient triplet exciton generation (a few exceptions were observed and these are discussed in Supplementary Note 3).

Ground-state redox potentials of the molecules were measured with cyclic voltammetry (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Table 2). Redox potentials in the triplet excited state \(E_{{\rm{ox/red}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) are estimated by:

Impressively, our molecules show a very broad range of ground- and excited-state redox potentials (Supplementary Fig. 25), enabling the development of wide-ranging photoredox-mediated reactions. The ground- and excited-state redox potentials are related to the ionization potential and electron affinity (vide infra), while the ionization potential and electron affinity are directly correlated with the HOMO and LUMO levels (Fig. 1b)41. Due to the strongly localized characters of the molecules’ frontier molecular orbitals on the donor/acceptor, as discussed above, \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) (\(E_{{\rm{red}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\)) is expected to be determined by the HOMO of the donor, whereas \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\) (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\)) should be determined by the LUMO of the acceptor. Indeed, upon variation of the donor in the series 6a–f (Fig. 3b), the HOMO energies follow the trend of \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\), and variation of the acceptor in the series 1b–11b (Fig. 3c) also shows that the LUMO energies follow the trend of \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\). In contrast, only very small changes were observed for \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\)of 6a–f and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) of 1b–11b. The trends seen for \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\) and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) are also observed for \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) and \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\), respectively (Fig. 3d,e). These results clearly prove that the ground- and excited-state redox potentials can be systematically and easily controlled by independently adjusting the donor and acceptor moieties.

We further explored the possibility of pre-synthetic computational screening of the redox potentials. For this, ionization potential and electron affinity values in DMF were obtained from DFT calculations (Supplementary Table 4). The ground-state redox potentials against the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) were then estimated by41:

where IP is the ionization potential and EA is the electron affinity. We used the calculated vertical T1 energies and evaluated the triplet excited-state redox potentials based on equations (1) and (2). As shown in Fig. 3b–e, the computed redox potentials reproduced the trends observed in the experiment. The calculated \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) agrees quite well with the experiment, whereas \(E_{{\rm{red}}}^0\) is typically underestimated since only the vertical ionization potential and electron affinity were calculated for fast screening (although adiabatic calculations are in better agreement; see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Table 10) and DFT tends to somewhat overestimate electron affinity values42, while for practical purposes, a DFT-directed catalyst development can be safely recommended.

Finally, the radical ion stability was determined from the reversibility of the voltammetric pattern. Most molecules, except carbazole analogues and diphenyl sulfone derivatives, showed reversibility in their oxidation and reduction waves (Supplementary Note 4, Supplementary Figs. 13–21 and Supplementary Table 2), indicating that the electrogenerated radical cations and anions were stable species. Because of the strong charge-transfer character, the stability can be determined by the frontier molecular orbitals of the donor cation and acceptor anion. Electrostatic potential map calculations for the radical cation and anion of 6f (6f·+ and 6f·‒) show that in 6f·+ the positive charge is localized on the donor moiety, while in 6f·‒ the negative charge is localized on the acceptor moiety, clearly supporting this argument (Fig. 1c). However, it should be noted that steric hindrance and electronic structure (for example, resonant forms and electrostatic stabilization) of radical ions can also affect their stability43, although the relative energies of frontier molecular orbitals are the most crucial factor.

Investigating the performance of the OPCs

Next, we examined the photocatalytic activities of the developed compounds under blue light-emitting diode (LED) irradiation conditions. The O-ATRP of MMA was chosen as the model reaction since it is truly photocatalytic (Table 1), and a relatively small photoredox catalyst reducing power is required (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) > ~ −0.9 V and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) < ~ −0.9V, respectively; see Table 1, mechanism)6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. In fact, most OPCs in our library exhibit suitable ground- and excited-state redox potentials and substantial visible-light absorptions (for exceptions, see Supplementary Table 2 and below). OPCs with poor solubility in DMF and no spectral overlap with 450 nm LEDs were excluded from the experiments (Supplementary Note 6). As a negative control experiment, the polymerization of MMA was first conducted in the absence of a catalyst (Table 1, entry 1) and no separable polymers were produced even after 24 h of irradiation, indicating that radicals are not generated from the DBM initiator without an OPC under these reaction conditions. To validate our polymerization set-up, we also performed the same reactions with Ir(ppy)3 and Miyake’s catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Table 5 (entries 3–8), the results obtained are in good agreement with the data from the groups of Hawker and Miyake, clearly demonstrating the reliability of our results. Our polymerization set-up was also highly reproducible under normal reaction conditions, as shown in Supplementary Table 6. The results of the O-ATRP of MMA with our molecules (100 ppm in DMF) are summarized in Table 1 (the entire set of results is shown in Supplementary Table 5). These polymerizations gave poly(methyl methacrylate) in good yields (65–82%) for most of the OPCs, demonstrating that our design platform is effective. Several catalysts (1b, 2a, 2c, 3c, 4d and 6f) facilitated very successful control over the polymerization reaction, with dispersity (Đ) values of 1.28 to 1.45 and initiator efficiencies (I*) of 0.74 to 0.91, even at the low catalyst concentration of 100 ppm (Table 1). Kinetics results and temporal control experiments of O-ATRP of MMA are given in Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34.

Catalyst property–performance relationships

According to the recent results of Matyjaszewski and co-workers8, the activation step of O-ATRP using activated alkyl halides as initiators follows the outer sphere electron transfer mechanism (Table 1, mechanism). This step involves a concerted dissociative electron transfer (DET), whose kinetics is governed by a modified Marcus model developed by Savéant44. The mechanism of C–X bond reductive cleavage strongly depends on the properties of the C–X bond, and the transfer coefficient (α) is commonly used to discriminate between concerted and stepwise DET processes. We evaluated the α value of the diethyl 2-bromo-2-methylmalonate (DBM) initiator from the difference between peak potential and potential in the half of the peak (ΔEp/2) measured by cyclic voltammetry, and the resulting value (α = 0.32) is significantly less than 0.5, clearly indicating that DBM reacts via a concerted DET (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 22)45. According to the modified Marcus model, sufficient light absorption, efficient triplet exciton generation and a highly reducing excited state are essential to promote the activation step. Therefore, the low conversion for some of our OPCs may be variously attributed to limited visible-light absorption (3e, 6a and 6e), inefficient triplet generation (3d, 5c, 5d and 6d) and insufficient reducing power (5c, 5d, 9b, 10b and 11b). See Supplementary Note 6 for a detailed discussion of the OPC trends for the polymerizations.

The deactivation mechanism plays a key role in controlling O-ATRP. A perfect balance of activation and deactivation steps allows the maintenance of a low radical concentration during the polymerization reactions, which leads to narrow Đ and high I*1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Thus, we can conclude that 1b, 2a, 3c, 4d, 4g and 6f may have fairly appropriate deactivation pathways. The catalyst design of 4g and its polymerization results are detailed below. Although the general deactivation mechanism in O-ATRP is still not fully understood, Matyjaszewski and co-workers convincingly suggested that the deactivation step of 10-phenylphenothiazine (Ph-PTZ) follows an associative electron transfer process involving a termolecular species (AET-ter)8. In the AET-ter mechanism, a high ground-state oxidation potential of the catalyst (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) ~ 0.8 V versus the SCE for Ph-PTZ analogues) will be required for efficient deactivation pathways. However, interestingly, 4g shows good control over the polymerization of MMA, although its \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) is only 0.26 V versus the SCE. Recently, Miyake and co-workers reported that OPCs with very low \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) (roughly –0.1 to 0.20 V) showed very good control over the polymerization of MMA, which is in good accordance with our results9,10,11,12,13. They also argued that such OPCs may form strong ion pairs of OPC+Br−, which was supported by the solvent polarity effect on the polymerizations, and thus the deactivation pathways may involve a pseudo-two-body collision event11. Given the large ground-state oxidation potentials of 2b, 3b and 6b (1.30, 1.05 and 1.20 V versus the SCE, respectively), these OPCs should provide better control over the polymerizations compared with 3c, 4d, 4g and 6f. However, the control turned out to be worse for 2b, 3b and 6b. Through screening of our OPC library, we have shown that a large ground-state oxidation potential is not a sufficient condition for achieving good control of polymerization, suggesting that the deactivation process does not always occur via the AET-ter mechanism. This implies that the deactivation step depends greatly on the characteristics of the intermediates formed, which can be guided by the specific molecular structure and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) of OPCs, and the stability of radical cations. To fully understand the deactivation mechanism for each single compound requires combined experimental and theoretical studies on the relationship between the catalysts’ parameters and their performance, which is beyond the scope of this paper. We are currently performing further mechanistic investigations for several OPCs.

O-ATRP of MMA at extremely low catalyst loading

We further optimized the polymerization conditions for several catalysts by changing the catalyst loading. Surprisingly, among the catalysts, 2c exhibited successful polymerization control, even at a catalyst concentration of 0.5 ppm (Table 1, entries 9 and 10), which is two to three orders of magnitude lower than those reported for organic/organometallic photoredox catalysts (Supplementary Table 7). Other OPCs, including Miyake’s catalysts, were examined under the same conditions for comparison, but showed low conversion with very poor control (Supplementary Table 8). Catalyst loadings of less than 1 ppm are very meaningful, as they would result in the direct use of polymers without the need for a catalyst removal process for industrial and biomedical applications. In fact, signals of catalyst residues in the resulting polymers were not observed at all in ultraviolet-visible photoluminescence and 1H NMR.

In contrast, very strong visible-light absorption (ε458nm = 13,900 M–1 cm–1), suitable \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) = 1.04 V and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) = –1.41 V), efficient generation of long-lived triplet excited states (τ = 28 μs) and a highly stable radical cation (perfectly reversible waves even after 20 repeated cyclic voltammetry cycles) were observed for 2c (Fig. 4a–d). These observations clearly support the outstanding catalytic performance of 2c. In particular, the visible-light absorption and triplet lifetime of 2c are approximately one order of magnitude higher than those of Ir(ppy)3 (ε458nm = 2,450 M–1 cm–1 and τ = 1 μs), which is a commonly used organometallic photoredox catalyst in many photoredox reactions.

a, Molecular structure (left) and calculated HOMO and LUMO topologies (right) of 4DP-IPN (2c). Experimentally evaluated \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast\) values are also shown. b, Ultraviolet-visible absorption (grey line), photoluminescence (PL) at room temperature (dark grey line), gated PL at 77 K (red line) and PL at 77 K spectra (green line) in DMF (2 × 10–5 M). τFL and τPH are fluorescence and phosphorescence lifetime, respectively. c, Cyclic voltammetry of 2.0 mM 2c in acetonitrile containing 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 on a glassy carbon working electrode at variable scan rates from 20 to 100 mVs–1. Inset, corresponding linear relationship between the anodic peak current (Ia) and square root of the scan rate (V1/2). d, Transient-absorption dynamics of 2c at a probe energy of 2.47 eV (triplet–triplet absorption band) after pumping with 300 ps pulses at 355 nm (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 8 for details).

Designing highly reducing OPCs

One of the greatest challenges in photoredox-mediated ATRP is the ability to polymerize non-acrylic monomers such as styrene3,4,5,6. As for the photoredox-mediated ATRP of styrene, the success of this reaction can be necessarily limited by the rather high photoredox catalyst reducing power required to activate the α-alkyl bromobenzyl moiety (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) > ~ –1.5 V and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) < ~ –1.5 V; see Table 1, mechanism), the slow propagation rate of styrene monomers and the quenching of triplet states by styrene monomers46 (originating from the rather low triplet energy of styrene, ~2.95 eV47,48). Consequently, only two polystyrene syntheses have been attempted to date7,49. A reported perylene dye resulted in a 17% conversion; in this case, I* was 0.02 and Đ was 1.39. In addition, Ph-PTZ was used to activate styrene under ultraviolet irradiation (380 nm LED) during co-polymer synthesis with a small styrene-feeding ratio of 10 mol%.

To address these issues, we designed a catalyst with a very high \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) while maintaining its visible-light absorption properties. Diphenylsulfone and phenylphenazine were chosen as the acceptor and donor units, respectively, based on our general strategy (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Note 7); the very weak acceptor was required to have high \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) and the strong donor was required to absorb visible light and produce a highly stable radical cation (Fig. 5b,d). The photophysical and electrochemical properties of the designed catalyst, 4g, were investigated. As expected, 4g exhibited very high reducing power in its excited state (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast \left( {{\rm{T}}_1} \right)\) = –2.30 V) and also broadly absorbed visible light, in good agreement with the DFT results. Furthermore, the ground-state oxidation potential of 4g was appropriate (\(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) = 0.26 V) for the reduction of the radical cation.

a, Molecular structure (left) and calculated HOMO and LUMO topologies (right) of 2DHPZ-DPS (4g). Experimentally evaluated \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^0\) and \(E_{{\rm{ox}}}^ \ast\) values are also shown. b, Ultraviolet-visible absorption (grey line), gated photoluminescence (PL) at 77 K (red line) and PL at 77 K spectra (green line) in DMF (2 × 10–5 M). τFL and τPH are fluorescence and phosphorescence lifetime, respectively. c, Calculation of structural reorganization energies (Ere = Evert – E00) of 4g for the processes 3PC*(T1) → PC·+(D+0) and PC·+(D+0) → P(S0) (left), where PC is the photoredox catalyst. Right, electrostatic potential maps of 4g·+(D+0) and 4g(S0). d, Cyclic voltammetry of 2.0 mM 4g in DMF containing 0.1 M nBu4NPF6 on a glassy carbon working electrode at variable scan rates from 10 to 100 mVs–1. Inset, corresponding linear relationship between the anodic peak current (Ia) and square root of the scan rate (V1/2). e, Transient-absorption dynamics of 4g at a probe energy of 2.7 eV (triplet–triplet absorption band) after pumping with 300 ps pulses at 355 nm (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. 8 for details).

The strong intramolecular charge-transfer character of the lowest excited states of 4g (Fig. 5a) greatly reduces the singlet–triplet energy gap (ΔEST = 0 eV), facilitating the generation of T1. Remarkably, a long-lived triplet excited state with a lifetime in excess of 1 ms was identified by transient-absorption spectroscopy (Fig. 5e), which is at least three orders of magnitude longer than the reported values for iridium and ruthenium complexes. These long triplet lifetimes may originate from weak SOC due to the lack of a heavy atom, which is in good agreement with the very long phosphorescence lifetime of 4g at 77 K (τPH = 0.68 s; Fig. 5b).

The strong donating power of the donor moiety in 4g gives rise to pronounced charge-transfer character, which facilitates the high stability of the radical cation, thereby ensuring high redox stability. This can be directly seen in an electrostatic potential map of the radical cation of 4g (4g·+), which shows that the positive charge is localized on the donor moiety in 4g·+ (Fig. 5c). Indeed, 4g exhibits almost perfectly reversible voltammetric cycles, even over 20 repeated cyclic voltammetry runs; the ratio of the anodic current peak (Ipa) to the cathodic current peak (Ipc) is 1.01 (Fig. 5d). In addition, the linear relationship between Ipa and the square root of the scan rate (V1/2) indicates that single-electron transfer between 4g and the electrode is faster than the diffusion limit. Relatively fast single-electron transfer is probably due to the small structural reorganization energy required to go from 4g·+ to 4g. In fact, the calculated reorganization energy was only 0.05 eV, which supports our hypothesis (Fig. 5c).

O-ATRP of styrene

Finally, we investigated the performance of compound 4g in polymerization reactions, starting with the O-ATRP of MMA. The optimized conditions provided for a very successful polymerization control, with a conversion of 78%, Đ = 1.46 and an I* = 0.70 at 100 ppm (Table 1, entry 7). Furthermore, 4g also successfully controlled the polymerization of styrene. In fact, the outcome (conversion of 63%, Đ = 1.51 and I* = 0.72 at 50 ppm; Table 1, entry 13) is exceptional compared with the other catalysts in our library, as well as the previously developed Ir(ppy)3 and Miyake’s catalyst (Supplementary Table 9). The results were further improved by increasing the temperature from 25 to 40 °C (conversion of 73%, Đ = 1.40 and I* = 0.90 at 50 ppm; Table 1, entry 14), which may be ascribable to the fact that the propagation rate of styrene greatly increases with increasing temperature, even at low radical concentrations. 4d showed insufficient performance despite having appropriate catalysts properties, and we are further investigating the origin of this phenomenon.

Conclusions

In summary, highly efficient visible-light OPCs were identified by a systematic computer-aided-design strategy, which successfully addresses the important challenges in O-ATRP. Catalyst loadings for O-ATRP were greatly reduced to the sub-ppm range, allowing for the direct use of polymers without further purification. Furthermore, the monomer scope was successfully expanded to styrene, which is one of the most important polymers for industrial applications. As a general platform for the design of OPCs, strongly twisted D–A structures are proposed in which the strong intramolecular charge-transfer character of its lowest excited state is crucial for triplet generation, as well as for the control of crucial catalyst parameters. In-depth combined experimental and theoretical investigations revealed that the unique combination of efficient generation of long-lived triplet excited states, strong reducing power of T1, high stability of radical cations and broad, strong visible-light absorption are the origins of the outstanding photocatalytic activities of our optimized compounds, namely 2c and 4g. We believe that our work on ATRP will help to resolve a variety of challenging issues relating to organic/polymer synthesis, light harvesting, water splitting and artificial photosynthesis.

Methods

Flow chart

In Fig. 1e, we suggest a flow chart for the rational design of OPCs for new photoredox-mediated reactions. As a first step, the mechanistic scheme (that is, oxidative and reductive quenching cycles) was determined (Fig. 1d). Depending on the mechanism, an acceptor (oxidative) or donor (reductive) is chosen since it determines the excited-state redox potential of the photoredox catalyst, which is an essential factor to open the catalytic cycle via PET. In this step, the property of the substrate should be carefully considered because the PET mechanism is strongly affected by the substrate24,25,26,27,50,51,52,53,54,55. Then, the donor (oxidative) or acceptor (reductive) can be decided as it determines the ground-state redox potential, which is essential to close the cycle via electron transfer. Having chosen the donor and acceptor, the light absorption should be considered using a suitable light source. After confirming the desired absorption, the stability of the radical ions and structural reorganization energies should be considered because they will govern the photoredox catalyst’s catalytic efficiency. A detailed discussion of the light absorption, radical ion stabilities and reorganization energies is provided in the Supplementary Information (see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Figs. 11, 24 and 43). All of these parameters can be precisely estimated through DFT and time-dependent DFT calculations, allowing for computationally directed design of photoredox catalysts. All parameters can be precisely tuned in a systematic way, enabling very effective feedback.

Computational details

DFT and time-dependent DFT calculations were performed with the B3LYP functional and 6–311G* basis set using the Gaussian09 suite of programmes56. The choice of the functional to properly calculate charge-transfer states is still a matter of debate40, but it has been shown in the past that singlet–triplet energy gaps in D–A systems with pronounced charge-transfer character (as in the current case) are well reproduced by B3LYP39, which was confirmed in the current case. Moreover, as many different properties had to be calculated at the same time and the mixing of different methods should be avoided for fast screening, B3LYP seems to be a good compromise (compared with specially designed functionals, which perform well for one purpose, but may fail for others). The geometries in the ground states (S0) were optimized in a vacuum, imposing the highest possible symmetry, which, at the same time, allowed for full conformational freedom (for example, bending of the donor/acceptor moieties). S0 energies and vertical energies for excited states (Si and Ti, where i = 1–20), as well as for radical cations and anions (D+0 and D−0), were obtained by single-point calculations on the vacuum ground-state geometries in DMF and/or acetonitrile, employing the polarizable continuum model. Adiabatic energies were obtained by full optimizations of the respective states (S1, T1 and D+0) in a vacuum, and the energies in DMF and acetonitrile were obtained by single-point calculations in the respective solvents. Reorganization energies are obtained as energy differences of the vertical and adiabatic energies for a given process, Ere = Evert – E00. Electrostatic surface potentials were obtained by the default procedure employed in Gaussian and plotted with GaussView 5.0. Molecular orbitals were plotted with ChemCraft 1.8.

General procedure for O-ATRP of MMA

A typical ATRP procedure for the standard reaction conditions [MMA]:[DBM]:[photoredox catalyst] = [200]:[1]:[0.02], [200]:[1]:[0.002] and [200]:[1]:[0.0001] was carried out as follows. A 20 ml glass vial equipped with a stirring bar was charged with MMA (1.0 ml, 9.29 mmol), DBM (9.07 μl, 0.046 mmol) and photoredox catalyst (0.000929 mmol), and anhydrous DMF (1 ml) as the solvent, inside a glove box, for reaction condition [MMA]:[DBM]:[photoredox catalyst] = [200]:[1]:[0.02]. For the reaction condition [MMA]:[DBM]:[2c] = [200]:[1]:[0.0001]; 2c (4.64 × 10−6 mmol) in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (2.5 ml) was used. Pre-prepared stock solution of the photoredox catalysts and initiator was used for higher reproducibility of the results. Afterwards, the vial was capped with a rubber septum, sealed with parafilm and bubbled with argon for 30 min outside the glove box. Subsequently, the polymerization was carried out for 12 h under 455 nm LED irradiation at room temperature. To isolate the polymers, the reaction mixture was first diluted with 3 ml of tetrahydrofuran and dissolved completely, then poured into a beaker containing methanol (75 ml), which caused the polymer to precipitate. Subsequent stirring for 30 min, followed by vacuum filtration, resulted in dried polymers.

General procedure for O-ATRP of styrene

A typical ATRP procedure for the standard reaction condition [styrene]:[DBM]:[photoredox catalyst] = [100]:[1]:[0.005] was carried out as follows. A 20 ml glass vial equipped with a stirring bar was charged with styrene (1.0 ml, 8.612 mmol), DBM (16.8 μl, 0.086 mmol) and photoredox catalyst (0.000431 mmol), and anhydrous DMF (0.5 ml) as the solvent, inside a glove box. Pre-prepared stock solution of the photoredox catalysts and initiator was used for higher reproducibility of the results. The styrene:DMF ratio was maintained at 1:0.5 for all of the reactions. Then, the vial was capped with a rubber septum, sealed with parafilm and bubbled with argon for 30 min outside the glove box. Subsequently, the polymerization was carried out for 36 h under 455 nm LED irradiation at room temperature. To isolate the polymers, the reaction mixture was first diluted with 4 ml of DMF and dissolved completely, then poured into a beaker containing methanol (75 ml), which caused the polymer to precipitate. Subsequent stirring for 1 h, followed by vacuum filtration, resulted in dried polymers.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, and from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Matyjaszewski, K. Advanced materials by atom transfer radical polymerization. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706441 (2018).

Matyjaszewski, K. & Tsarevsky, N. V. Macromolecular engineering by atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6513–6533 (2014).

Corrigan, N., Shamugam, S., Xu, J. & Boyer, C. Photocatalysis in organic polymer synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 6165–6212 (2016).

Pan, X. et al. Photomediated controlled radical polymerization. Prog. Polymer Sci. 62, 73–125 (2016).

Shanmugam, S. & Boyer, C. Organic photocatalysts for cleaner polymer synthesis. Science 352, 1053–1054 (2016).

Theriot, J. C., McCarthy, B. G., Lim, C. H. & Miyake, G. M. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization: perspectives on catalyst design and performance. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 38, 1700040 (2017).

Treat, N. J. et al. Metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16096–16101 (2014).

Pan, X. et al. Mechanism of photoinduced metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization: experimental and computational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2411–2425 (2016).

Theriot, J. C. et al. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization driven by visible light. Science 352, 1082–1086 (2016).

Pearson, R. M., Lim, C. H., McCarthy, B. G., Musgrave, C. B. & Miyake, G. M. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization using N-aryl phenoxazines as photoredox catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11399–11407 (2016).

Lim, C. H. et al. Intramolecular charge transfer and ion pairing in N,N-diaryl dihydrophenazine photoredox catalysts for efficient organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 348–355 (2017).

McCarthy, B. G. et al. Structure–property relationships for tailoring phenoxazines as reducing photoredox catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5088–5101 (2018).

Sartor, S. M., McCarthy, B. G., Pearson, R. M., Miyake, G. M. & Damrauer, N. H. Exploiting charge-transfer states for maximizing intersystem crossing yields in organic photoredox catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4778–4781 (2018).

Ghosh, I., Ghosh, T., Bardagi, J. I. & Konig, B. Reduction of aryl halides by consecutive visible light-induced electron transfer processes. Science 346, 725–728 (2014).

Murphy, J. J. et al. Asymmetric catalytic formation of quaternary carbons by iminium ion trapping of radicals. Nature 532, 218–222 (2016).

Silvi, M., Verrier, C., Rey, Y. P., Buzzetti, L. & Melchiorre, P. Visible-light excitation of iminium ions enables the enantioselective catalytic β-alylation of enals. Nat. Chem. 9, 868–873 (2017).

Pandey, G. & Laha, R. Visible-light-catalyzed direct benzylic C(sp 3)–H amination reaction by cross-dehydrogenative coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14875–14879 (2015).

Rybicka-Jasinska, K., Shan, W., Zawada, K., Kadish, K. M. & Gryko, D. Porphyrins as photoredox catalysts: experimental and theoretical studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15451–15458 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Structural design principle of small-molecule organic semiconductors for metal-free, visible-light-promoted photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9783–9787 (2016).

Luo, J. & Zhang, J. Donor–acceptor fluorophores for visible-light-promoted organic synthesis: photoredox/Ni dual catalytic C(sp 3)–C(sp 2) cross-coupling. ACS Catal. 6, 873–877 (2016).

Poelma, S. O. et al. Chemoselective radical dehalogenation and C–C bond formation on aryl halide substrates using organic photoredox catalysts. J. Org. Chem. 81, 7155–7160 (2016).

Kottisch, V., Michaudel, Q. & Fors, B. P. Cationic polymerization of vinyl ethers controlled by visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15535–15538 (2016).

Kottisch, V., Supej, M. J. & Fors, B. P. Enhancing temporal control and enabling chain‐end modification in photoregulated cationic polymerizations by using Ir‐based catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8260–8264 (2018).

Arias-Rotondo, D. M. & McCusker, J. K. The photophysics of photoredox catalysis: a roadmap for catalyst design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5803–5820 (2016).

Dumur, F., Gigmes, D., Fouassier, J. & Lalevee, J. Organic electronics: an El Dorado in the quest of new photocatalysts for polymerization reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1980–1989 (2016).

Majek, M. & Wangelin, A. J. Mechanistic perspectives on organic photoredox catalysis for aromatic substitutions. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 2316–2327 (2016).

Romero, N. A. & Nicewicz, D. A. Organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 116, 10075–10166 (2016).

Hirata, S. Recent advances in materials with room-temperature phosphorescence: photophysics for triplet exciton stabilization. Adv. Opt. Mater. 5, 1700116 (2017).

El-Sayed, M. A. The triplet state: its radiative and non-radiative properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 1, 8–16 (1968).

Turro, N. J. The triplet state. J. Chem. Educ. 46, 2–6 (1969).

Bolton, O., Lee, K., Kim, H. J., Lin, K. Y. & Kim, J. Activating efficient phosphorescence from purely organic materials by crystal design. Nat. Chem. 3, 205–210 (2011).

Kwon, M. S. et al. Suppressing molecular motions for enhanced room-temperature phosphorescence of metal-free organic materials. Nat. Commun. 6, 8947 (2015).

Zhang, G., Palmer, G. M., Dewhirst, M. W. & Fraser, C. L. A dual-emissive-materials design concept enables tumour hypoxia imaging. Nat. Mater. 8, 747–751 (2009).

El-Sayed, M. A. Spin–orbit coupling and the radiationless processes in nitrogen heterocyclics. J. Chem. Phys. 38, 2834–2838 (1963).

Flamigni, L. et al. Photochemistry and photophysics of coordination compounds: iridium. Top. Curr. Chem. 21, 143–203 (2007).

Kalyanasundaram, K. Photophysics, photochemistry and solar energy conversion with tris(bipyridyl)ruthenium(ii) and its analogues. Coord. Chem. Rev. 46, 159–244 (1982).

Fukuzumi, S. et al. Electron-transfer state of 9-mesityl-10-methylacridinium ion with a much longer lifetime and higher energy than that of the natural photosynthetic reaction center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1600–1601 (2004).

Uoyama, H., Goushi, K., Shizu, K., Nomura, H. & Adachi, C. Highly efficient organic light emitting diodes from delayed fluorescence. Nature 492, 234–238 (2012).

Milián-Medina, B. & Gierschner, J. Computational design of low singlet–triplet gap all organic molecules for OLED application. Org. Elec. 13, 985–991 (2012).

Bombarelli, R. G. et al. Design of efficient molecular organic light-emitting diodes by a high-throughput virtual screening and experimental approach. Nat. Mater. 15, 1120–1127 (2016).

Kucur, E., Riegler, J., Urban, G. A. & Nann, T. Determination of quantum confinement in CdSe nanocrystals by cyclic voltammetry. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 2333–2337 (2003).

Zhang, G. & Musgrave, C. B. Comparison of DFT methods for molecular orbital eigenvalue calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 1554–1561 (2007).

Coote, M. L., Lin, C. Y., Beckwith, A. L. J. & Zavitsas, A. A. A comparison of methods for measuring relative radical stabilities of carbon-centered radicals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 9597–9610 (2010).

Savéant, J. M. A simple model for the kinetics of dissociative electron transfer in polar solvents. Application to the homogeneous and heterogeneous reduction of alkyl halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109, 6788–6795 (1987).

Isse, A. A. et al. Mechanism of carbon–halogen bond reductive cleavage in activated alkyl halide initiators relevant to living radical polymerization: theoretical and experimental study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6254–6264 (2011).

Kuhlmann, R. & Schnablel, W. Laser flash photolysis investigations on primary processes of the sensitized polymerization of vinyl monomers: 1. Experiments with benzophenone. Polymer 17, 419–422 (1976).

Wan, J. & Nakatsuji, H. Theoretical study of the singlet and triplet vertical electronic transitions of styrene by the symmetry adapted cluster–configuration interaction method. Chem. Phys. 302, 125–134 (2004).

Saltiel, J., Charlton, J. L. & Mueller, W. B. Nonvertical excitation transfer. Activation parameters for endothermic triplet–triplet energy transfer to the stilbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 1347–1348 (1979).

Miyake, G. M. & Theriot, J. C. Perylene as organic photocatalyst for the radical polymerization of functionalized vinyl monomers through oxidative quenching with alkyl bromides and visible light. Macromolecules 47, 8255–8261 (2014).

Pier, C. K., Rankic, D. A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Visible light photoredox catalysis with transition metal complexes: application in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 113, 5322–5363 (2013).

Narayanam, J. M. R. & Stephenson, C. R. J. Visible light photoredox catalysis: applications in organic synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 102–113 (2011).

Yoon, T. P., Ischay, M. A. & Du, J. Visible light photocatalysis as a greener approach to photochemical synthesis. Nat. Chem. 2, 527–532 (2010).

Fagnoni, M., Dondi, D., Ravelli, D. & Albini, A. Photocatalysis for the formation of the C–C bond. Chem. Rev. 107, 2725–2756 (2007).

Marin, M. L., Santos-Juanes, L., Arques, A., Amat, A. M. & Miranda, M. A. Organic photocatalysts for the oxidation of pollutants and model compounds. Chem. Rev. 112, 1710–1750 (2012).

Fukuzumi, S. & Ohkubo, K. Selective photocatalytic reactions with organic photocatalysts. Chem. Sci. 4, 561–574 (2013).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09 Revision D.01 (Gaussian, 2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 2018 Research Fund (1.180067.01) of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology, and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), which was funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF–2016R1D1A1B03936002) and National Honor Scientist Program (2010–0020414) of the NRF. The work at IMDEA was supported by the ‘Severo Ochoa’ programme for Centers of Excellence in Research and Development (MINECO; grant SEV–2016–0686), European Union structural funds and Comunidad de Madrid MAD2D-CM Program (S2013/MIT–3007), and Campus of International Excellence UAM + CSIC. Financial support at IMDEA and the University of Valencia was further provided by the Spanish Ministry for Science (MINECO–FEDER projects CTQ2014–58801 and CTQ2017–87054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.K. conceived and supervised the project. K.S.K. and J.G. supported and assisted in supervising the project. V.K.S. and M.S.K. designed the experiments and analysed the data. V.K.S. and C.Y. performed most of the experiments. S.B., Y.Kim, Y.Kwon, D.K., J.L., T.A. and G.T. helped with the synthesis of OPCs and polymerization studies. P.C.N., R.W. and L.L. performed advanced photophysical measurements. B.M.-M. and J.G. carried out the quantum chemical calculations. L.S.P. and J.L. advised on the experiments. V.K.S., K.S.K., J.G. and M.S.K. prepared the manuscript, with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Notes 1–7, Supplementary Figures 1–86, Supplementary Tables 1–10 and Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, V.K., Yu, C., Badgujar, S. et al. Highly efficient organic photocatalysts discovered via a computer-aided-design strategy for visible-light-driven atom transfer radical polymerization. Nat Catal 1, 794–804 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0156-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-018-0156-8

This article is cited by

-

Photoredox-controlled alternating copolymerization enables highly crystalline structures and block copolymers from thermoplastic to elastomer

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Elucidating the molecular structural origin of efficient emission across solid and solution phases of single benzene fluorophores

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Ultraviolet light blocking optically clear adhesives for foldable displays via highly efficient visible-light curing

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Highly efficient dual photoredox/copper catalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization achieved through mechanism-driven photocatalyst design

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Sequential closed-loop Bayesian optimization as a guide for organic molecular metallophotocatalyst formulation discovery

Nature Chemistry (2024)