Abstract

Upgrading biomass feedstock into higher-value chemicals is central to improve the sustainability of the chemical industry and to reduce its dependence on fossil raw materials. Heterogeneous photocatalysts are promising for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), a biomass-derived molecular platform for biopolymers, but their FDCA selectivity is negligible without the aid of a base. Here we present a plasmonic photocatalyst integrating TiN nanocubes and bimetallic RuPt nanoparticles that in base-free conditions exhibits complete HMF conversion and selective FDCA formation due to an unconventional mechanism of molecular oxygen activation. This unique reactivity is enhanced by both photothermal heating and hot electrons, whose contribution is confirmed by kinetic isotopic effect experiments. Density functional theory calculations support a scenario in which the activated nanoparticle–oxygen complex facilitates the rate-determining step and enables an improved FDCA selectivity. Our results demonstrate the potential of plasmonic photocatalysts in the catalytic transformation of biomass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

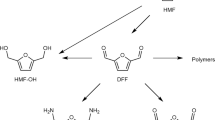

The exponential growth of the global population has prompted a depletion of fossil fuel reserves and a continuous rise in energy demand. This, in turn, has increased the impact of energy-intensive chemical industries, a major contributor to global warming and the associated challenges of climate change. In response to these pressing concerns, there is a compelling need to explore chemical processes powered by light that convert sustainable raw materials, biomass being the most abundant one, into higher-value chemicals1,2,3,4,5,6. The biobased products industry has an enormous potential, supporting four million jobs with a value of US$369 billion to the US economy7. Biomass is composed of 80–90% hemicellulose and cellulose, the hydrolysis of which produces sugars that can be easily transformed into a variety of chemicals via biological or chemical conversions. The US Department of Energy has identified 12 promising sugar-based building blocks that can be used to produce secondary chemicals, intermediates and final products, mirroring the petroleum-based supply chain8. Among these, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is considered a key platform molecule to synthesize commodity chemicals including solvents and polymers. HMF can be readily produced from hexoses by acid-catalysed dehydration (Fig. 1a) and the fully oxidized HMF adduct, 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA), is structurally like terephthalic acid, the monomer used in polyethylene terephthalate plastics. In view of these applications, FDCA synthesis has been extensively studied9,10.

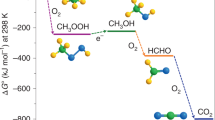

a, Schematics showing the process to obtain HMF from biomass and its two oxidation pathways to FDCA in the presence of O2. TiN–RuPt nanocubes use NIR light, generating plasmonic hot carriers and heating to selectively steer product formation using path 1. FDCA is a versatile molecular platform for the synthesis of biopolymers, solvents and fine chemicals. b, Energy-dispersive spectroscopy elemental map highlighting the atomic distribution of ruthenium and platinum in a representative single TiN–RuPt nanocube. c,d, DRIFT spectra of CO adsorbed on the different photocatalysts after a pretreatment in H2 at 200 °C (c) and after a two-step procedure consisting of H2 at 200 °C and interaction with O2 at room temperature (d).

The selective oxidation of HMF to FDCA involves three oxidation steps and may follow two competing pathways (1 and 2 in Fig. 1a), which differ in the first step by alternatively generating either 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (HMFCA) or 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF). These intermediates are then oxidized to 5-formyl-2-furancarboxylic acid (FFCA) and finally to FDCA. Therefore, selective FDCA synthesis is challenging because it requires catalysts with controlled reactivity to avoid overoxidation or mineralization of HMF. This has been achieved over heterogeneous catalysts with molecular oxygen in water. However, harsh conditions such as a strongly alkaline environment, high temperature (>80–100 °C), and high O2 pressure (>10 bar) are necessary for the reaction to proceed9. In contrast, photocatalysis can unlock milder reaction conditions using only light energy to power the process. HMF oxidation has been performed over semiconducting photocatalysts at near-ambient temperature, base-free and under atmospheric pressure10. Notably, all the reported photocatalysts follow path 2 (Fig. 1a), favouring HMF dehydrogenation and the consequent formation of DFF and H2. Only in a few cases, where semiconductor substrates were functionalized with molecular catalysts controlling O2 activation, were HMFCA (path 1) or FDCA selectively produced11,12. Recently, photocatalysts including plasmonic nanoparticles supported on semiconductors have demonstrated the ability to produce HMFCA and FDCA in alkaline environments13, although they exhibit no activity in base-free conditions. Common to both classes of photocatalysts is the generation of oxygenated radicals in solution, species with strong oxidizing power generated on the semiconductor’s surface. As a consequence, unselective processes often take place, undermining product selectivity. Thus, it is a challenge to achieve high FDCA selectivity in base-free conditions with no external heating and at ambient O2 pressure.

Subwavelength metallic photocatalysts feature enhanced light–matter interaction through localized surface plasmon resonances. This results in highly intense electric fields (hot spots), energetic nonthermal (hot) carriers and local heating that can modify and accelerate catalytic reactions14. However, the most plasmonically active metals such as gold, aluminium, silver and TiN, have modest catalytic activity. Therefore, a more efficient approach to transduce light into chemical energy can be achieved by assembling bimetallic photocatalysts bearing antenna (light collecting) and reactor (catalytic) units15.

We develop antenna–reactor photocatalysts constituted by plasmonic TiN nanocubes functionalized with bimetallic RuPt nanoparticles (NPs). These photocatalysts show a unique mechanism of oxygen activation that enables HMF oxidation with 100% conversion and nearly 100% FDCA selectivity under near-infrared (NIR) light, with no base addition, using O2 flow, aligning with path 1 depicted in Fig. 1a. Such results are achieved by tuning the RuPt composition and using photothermal heating in concert with plasmonic hot carriers. Using electromagnetic simulations, we reveal the optical properties of TiN–RuPt nanocubes and show that hot carriers preferentially form nanoscale patches at precise interface and surface positions. We experimentally investigate thermal and nonthermal plasmonic effects showing that hot electrons (HEs) enable faster HMF conversion kinetics and a remarkable 20% improvement in FDCA selectivity by participating in the rate-determining step, as supported by the observation of a larger kinetic isotopic effect under photocatalytic conditions. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide an atomistic view of the reaction mechanism and suggest a decisive catalytic role of RuPt bimetallic reactors. The interplay between ruthenium and platinum atoms is crucial: the former facilitates O2 dissociation at the photocatalyst surface, while the latter reduces the oxygen adsorption energy on the metal surface. Consequently, protons exhibit a greater affinity for oxygen atoms bonded to platinum atoms over those bonded to ruthenium atoms. This affinity proved to be instrumental in the selective oxidation of HMF. The results show that plasmonic antenna–reactor photocatalysts are promising candidates for performing controlled oxidation of biomass-derivatives into higher-value products.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of plasmonic TiN–RuPt photocatalysts

TiN–RuPt nanocubes were loaded with 10 wt% total metal content (nominal), including reference monometallic TiN–Pt and TiN–Ru, as confirmed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Figure 1b and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 show the microscopic characterization of a representative TiN nanocube with average size of 50 ± 10 nm where each facet is decorated with a multitude of RuPt nanocrystals. The TiN core retained a stoichiometric atomic distribution of titanium and nitrogen after metal deposition. The oxygen map shows the presence of a thin layer rich in oxygen due to TiN passivation upon exposure to air and chemicals during the synthesis16. The nanoscale elemental maps of ruthenium and platinum evidence the formation of bimetallic RuPt nanocrystals having an average size of 5.5 nm and mostly assuming an alloyed or Janus configuration, with sparse monometallic NPs separated probably due to the high metal loading on TiN (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. 3–5). To experimentally confirm frequent atomic contacts between the two metals, we carried out synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements at the Pt L3 edge for TiN–RuPt and analysed the extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS). The data confirmed the presence of a notable amount of Ru–Pt contacts in the sample (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements revealed that ruthenium is composed by two species peaking at 280.4 and 281.0 eV and assigned to the presence of Ru0 and Ru4+, respectively. Ru0 is the dominant species (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7), but interestingly, the concentration of ionic ruthenium increased in TiN–RuPt (35% ± 8%) in comparison to TiN–Ru (27% ± 6%). The same trend was observed for platinum, which however presented a higher content of Pt0 and a more modest increase in ionic species (Pt2+). These results suggest that the formation of positive ionic species is a feature of TiN–metal nanocatalysts that is enhanced by Ru–Pt electrostatic interactions. These aspects can favour the HE transfer from the TiN antenna to the RuPt reactors, and tune the reaction mechanism over TiN–RuPt, as will be discussed in detail later. The deconvolution of the titanium 2p region (Supplementary Fig. 8) highlights the presence of three surface species, assigned namely to TiN (454.8 eV), TiNxOy (456.4 eV) and TiO2 (458.4 eV), confirming the oxidation of the outer layer of TiN nanocubes, in agreement with elemental mapping16,17.

Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectroscopy was used to obtain deeper insights into the surface active sites, using CO as probe molecule since it can provide information on the coordination and oxidation state of the metal species. Figure 1c shows that no CO adsorption was detected on pure TiN. Conversely, the TiN–Pt spectrum shows a band at ∼2,050 cm−1, which can be ascribed to linear carbonyls on metallic platinum17. The TiN–Ru spectrum features instead a complex absorption with the main components centred at ∼2,030 and ∼1,980 cm−1, which are assigned to carbonyls on Ru0 sites with different coordination. Moreover, a broad tail extending below 1,900 cm−1 can be associated with bridged CO species18. In the TiN–RuPt spectrum we can recognize both components as arising from Pt–CO interactions, namely, a shoulder around 2,070 cm−1 (previously observed for Pt(111)/Ru bimetallic electrodes)19, and signals due to Ru–CO interactions at lower wavenumbers. The latter are more perturbed with respect to the TiN–Ru spectrum, in agreement with the more pronounced charge relocation on the ruthenium atoms than on the platinum ones observed from XPS data. We hypothesize that activated molecular oxygen is involved in the selective oxidation of HMF to FDCA over TiN-based photocatalysts. To verify this interaction, we performed CO DRIFT spectroscopy after contacting the samples with O2 (Fig. 1d). The CO band position in the spectrum of TiN–Pt was not substantially modified and only its intensity was reduced. The spectrum of TiN–Ru shows, instead, an evident shift of the main absorption band to 2,050 cm−1, suggesting a dominant role of ruthenium atoms in O2 binding. Notably, the TiN–RuPt spectrum is quite similar to the TiN–Ru one, but we note the presence of an additional band at 2,130 cm−1, which can be ascribed to CO interacting with ruthenium sites bearing a positive charge and influenced by the presence of neighbouring oxygen atoms18. This spectral feature can be considered a fingerprint of a peculiar O2 activation in the bimetallic system.

As such, the system was modelled as a TiO2 surface supporting the metallic NPs (Supplementary Fig. 9). The mean Pt–Ru distance in our DFT model is 2.707 Å at the RuPt–TiO2 interface and 2.699 Å within the RuPt NP. The average Pt–Ru spacing is therefore 2.703 Å, which closely matches the experimental value of 2.7 Å found from EXAFS analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Regarding the coordination geometry, in the experimental structure, one platinum atom is reported to bind two ruthenium atoms and five–six other platinum neighbours. Our DFT analysis suggests a similar geometry, with each platinum atom coordinating two–four ruthenium atoms and around two nearest-neighbour platinum atoms. This excellent agreement suggests that the interfacial and bulk bonding environments are well represented in our computational framework. Calculated Bader charge analysis (Supplementary Table 4) using a hybrid-DFT method confirmed the formation of a positive total charge on the bimetallic NP that was bound to the TiO2 surface mostly via ruthenium atoms (TiO2–Ru7Pt7up). The differential electron density (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11) shows a more pronounced charge relocation on the ruthenium atoms than on the platinum ones. The average charge on the surface ruthenium atoms increased from +0.98e in TiO2–Ru to +1.35e in TiO2–RuPt. The theoretical charge increase was less important on platinum atoms, rising from +0.41e in TiO2–Pt to +0.53e in TiO2–RuPt, in agreement with XPS findings.

To investigate the optical properties of the prepared plasmonic photocatalysts, we measured the extinction spectra of functionalized TiN nanocubes (Fig. 2a). All the spectra show the typical peak at 300 nm due to interband transitions in TiN and a localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) in between the visible and NIR spectral regions. The bare TiN nanocubes show a LSPR peak at 670 nm, which redshifted to 710 nm (TiN–Ru), 760 nm (TiN–Pt) and 800 nm (TiN–RuPt) as the result of the dielectric environment change at the surface of TiN after functionalization16. The light extinction properties were disentangled by means of finite-element method (FEM) simulations using a geometrical model including a TiN cubic core (40 nm), a TiO2 shell (1.5 nm) and bearing 16 RuPt NPs on each side (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 5). As expected, most of the incoming light is absorbed by the plasmonic TiN–RuPt nanocubes, while the scattering cross-section is minimal (Supplementary Fig. 13)16. By analysing the calculated absorption cross-section at visible and NIR wavelengths for each component forming the photocatalysts (Fig. 2b) we confirmed that TiN nanocube is the antenna dominating light absorption, RuPt NPs provide a minor contribution in comparison to TiN, and the TiO2 surface layer does not absorb any red light, that is, it will not contribute to generation of energetic carriers during photocatalysis.

a, Experimental extinction spectra of TiN-based photocatalysts in water. b, Simulated optical cross-sections of a TiN–RuPt nanocube showing the contribution from the material components. c, Theoretical HE generation rates (rateHE) in TiN and all RuPt NPs. d, HE generation rate map at the TiN–TiO2 interface in a TiN–RuPt nanocube. e, HEover-barrier generation rate map at the surface of RuPt NPs in a TiN–RuPt nanocube. Red and blue shading show the most and least intense hot spots, respectively. f, HEover-barrier generation rate spectra of representative RuPt NPs on facet 2 of TiN nanocube. g, HEover-barrier generation rate maps for representative RuPt NPs on facet 1 and 2 of TiN nanocube. For each pair of numbers x–y, x is the TiN nanocube facet and y is the RuPt NP shown in e. Maps are for λ = 751 nm and all theoretical results were obtained using (k║z, E0║x).

To connect the optical properties to the photocatalytic reactivity, we used a consolidated quantum mechanical formalism coupled to the FEM model to disclose the nanoscale distribution of computed HE generation rate (rateHE) within a TiN–RuPt nanocube. As expected, the peak of rateHE is redshifted (745 nm) in comparison to absorption (681 nm)20. Notably, the rateHE integrated within the TiN nanocube is 103 times higher than rateHE integrated over all RuPt NPs (Fig. 2c). The rateHE is proportional to the square of the electric field generated on the surface of the plasmonic nanostructures and the regions where it is maximized are the photocatalytic hot spots. In the case of bare TiN nanocubes, the field is mainly localized at the edges (Supplementary Fig. 14). In contrast, for a TiN–RuPt nanocube (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16), the rateHE pattern at the TiN–TiO2 interface is modified by the presence of RuPt reactors, whose presence induces HE hot spots on those areas where they are sitting. This site-selective HE generation enhances the probability of HE transfer from TiN antenna to RuPt reactors, making them available for the photocatalytic reaction. The RuPt reactors are also able to generate HEs by themselves, whose amount and dispersion depend on their specific positioning onto the TiN surface (Supplementary Figs. 17–19). Figure 2e,f highlights that both the predicted nanoscale distribution of rateHE and its wavelength-dependency vary when considering both different nanocube facets and specific position within them. At a given direction of light propagation, some RuPt reactors will produce more HEs (Fig. 2e, red shaded areas), and therefore will possess higher reactivity than others (Fig. 2e, blue shaded area). Furthermore, each NP will exhibit its own peculiar nanoscale rateHE patch forming unique HE hot spots depending on their location within a facet (Fig. 2g).

The optical generation of HEs in plasmonic nanostructures is followed by their thermalization and a rise in local temperature, which in turn affects photocatalytic rates. The evaluation of the temperature increase observed under illumination is at the centre of a vibrant debate due to its relevance in properly addressing thermal versus nonthermal reactivity21,22,23,24. It is accepted that precisely measuring the catalyst temperature is especially challenging in systems where large temperature gradients can occur, such as in three-dimensional powder beds for gas-phase catalysis and for NPs deposited on a substrate and studied by optical microscopy25. Both approaches use focused light and higher light powers (for the latter case they can easily be 106 times higher than ours). For three-dimensional systems in aqueous solution, which use homogeneous illumination and low intensity, instead, the phototemperature due to collective effects can be precisely estimated using a thermocouple16,23,26. To support this hypothesis, we analytically computed the photoinduced temperature gradient generated by one nanocube at the TiN–RuPt/water interface under the highest light intensity used. Temperature gradients exist only at the NP–water interface, while the TiN antenna and the RuPt NPs can be considered to be at the same temperature because of their high thermal conductivities and the high electronic thermal conductance of the TiN–RuPt interface that allows efficient heat transfer through electron–electron scattering (Supplementary Fig. 20)25. A single TiN–RuPt nanocube can generate a theoretical temperature gradient of 4.5 × 10−5 K. Even considering that our NPs undergo aggregation (Supplementary Fig. 21) and give rise to hot spots between touching nanocubes, the surface temperature remains a fraction of a kelvin (Supplementary Note 1). To further support our calculations, we use the photothermal coefficient experimentally determined through anti-Stokes photoluminescence single-particle thermometry for antenna–reactor systems comparable to ours25, and we find that the thermal gradient generated at the TiN–RuPt/water interface is 1.0 × 10−4 K (Supplementary Note 1). Interestingly, this value is just two times higher than the theoretical one, but still smaller by several orders of magnitude than the macroscopic increase in temperature measured with the thermocouple in the reaction suspension (ΔTphoto = 36 °C). The final macroscopic temperature is given by the sum of the temperature gradients produced at each particle–water interface at steady state, that is, once thermal equilibrium among the NPs, the solvent and the environment is reached. This means that under our reaction conditions such tiny temperature gradients cannot provide alone for a substantial reaction kinetics enhancement, and that the macroscopic temperature of the solution is a collective heating effect and as such influences the reaction mechanism. For these reasons, the control experiments under dark conditions shown in the next section were carried out by using the temperature measured with a thermocouple immersed in the reaction suspension during the photocatalytic runs.

Photocatalysis

The photocatalysts were tested in the oxidation of HMF using optimized amounts of substrate and catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 22), base-free conditions, an oxygen flow rate of 5 mL min−1 and a reaction time of 24 h, and using NIR light (740 nm, 0.222 W cm−2) to excite the LSPR of TiN-based nanohybrids. The transformation of HMF under reaction conditions without catalyst was negligible, while with bare TiN, a 49% ± 2% HMF conversion was achieved (Fig. 3a), although no oxidation products from both pathways 1 and 2 were detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). This product residue (degradation products, DP) consists of molecules formed during HMF overoxidation eventually leading to carbon dioxide. Under dark conditions, TiN nanocubes did not catalyse any HMF conversion, suggesting that their uncontrolled oxidation activity is triggered by plasmonic hot carriers (migrating on the TiO2 outer layer) and accelerated by the photothermal temperature increase.

a,b, Photocatalytic activity (a) and selectivity (b) of studied photocatalysts. c, Kinetics of HMF photocatalytic performance. d, Stability tests over five catalytic cycles. e,f, Photocatalytic performance under varying power density (e) and in dark conditions at the temperature generated under the corresponding light conditions (f). When not specified in the plots, data refer to the best-performing TiN–RuPt (1:1) sample after 24 h of reaction under NIR irradiation at 0.222 W cm−2. Data are presented as the mean values of at least three independent measurements. Error bars represent the s.d.

The reactivity strikingly changed once ruthenium, platinum or bimetallic RuPt NPs were deposited on TiN nanocubes. These photocatalysts selectively formed products from oxidation path 1, both under dark and light conditions, namely HMFCA and FDCA, along with minor amounts of DP (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 23). This result confirmed that ruthenium and platinum atoms act as the reactor components in the antenna–reactor photocatalyst assembly. Figure 3a shows that TiN–Pt exhibited better photocatalytic performance (Supplementary Note 2) than TiN–Ru, with the former achieving complete HMF conversion and an FDCA selectivity of 77% ± 4%, and the latter 70% ± 2% HMF conversion and 25% ± 1% FDCA selectivity. Notably, TiN–RuPt (1:1 wt% ratio) demonstrated exceptional activity by fully converting HMF with an enhanced FDCA selectivity of 98% ± 5%. The optimal Ru:Pt weight ratio was 1:1; indeed, for TiN–RuPt with 3:1 and 1:3 metal ratios, the platinum or ruthenium enrichment produced worse performance (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 6) with photocatalytic behaviour approaching that of TiN–Pt or TiN–Ru, respectively. The photocatalytic kinetics of HMF oxidations for the best-performing TiN–RuPt catalyst (Fig. 3c) shows that 77% ± 4% HMF conversion was reached after only 3 h of reaction. Subsequently, the reaction kinetics slowed down and needed an additional 14 h to reach full conversion. Moreover, product selectivity kinetics highlights that HMFCA was formed as an intermediate of FDCA, with the latter dominating at longer reaction times. The catalyst recyclability was tested over five cycles, during which TiN–RuPt showed remarkable performance, retaining 100% HMF conversion and showing only a minor decrease in FDCA selectivity after the fifth run (Fig. 3d). The pronounced reactivity of TiN–RuPt is further highlighted by considering that most heterogeneous catalysts based on platinum on carbon/oxide supports show similar performance in base-free conditions only at high temperature and high O2 pressure (Supplementary Table 7).

Under the applied illumination conditions, TiN–RuPt produced substantial photothermal heating in the reaction solution, reaching a temperature of 58 °C. To clarify to the role played by plasmon-induced thermal and nonthermal effects, HMF oxidation was carried out both using different light intensities (Fig. 3e) and in dark at the corresponding photoinduced temperatures (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 24). Photocatalytic experiments enabled a 100% HMF conversion using as little as 0.111 W cm−2, while for the dark equivalent at 40 °C, conversion was limited to 83% ± 4%. Dark conditions needed a further 10 °C temperature increase to complete the HMF transformation. At the highest employed light intensity (0.222 W cm−2), a 20% gain in FDCA selectivity was also reached in comparison to the pure thermal case. More generally, a given photocatalytic condition ensured better performance, in particular providing enhanced FDCA selectivity. These experiments suggest that the photocatalytic HMF oxidation with TiN–RuPt nanocubes was driven by the photothermal heating, with plasmonic HEs enhancing the oxidation rate of HMFCA to FDCA.

Reaction mechanism

All reported semiconductor photocatalysts catalyse HMF dehydrogenation to DFF (path 2); with reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide species (O2·−), hydroxyl radical (OH·) and singlet oxygen (1O2) always detected and being suggested to be responsible for the reactivity (Supplementary Table 8). To test if the reaction mechanism on TiN–RuPt was affected by ROS, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy with various spin-trapping molecules was performed (Supplementary Methods). Notably, no ROS signal was observed in all explored conditions, probably due to the different hot carrier lifetimes and oxygen reactivity of metal surfaces in comparison to metal oxide ones. To clarify the role of O2, we performed an experiment under photocatalytic conditions (740 nm, 0.222 W cm−2) and argon flow to completely eliminate the dissolved O2 in the suspension during the reaction. Notably, in an inert atmosphere HMF conversion was nearly zero (∼1%) and no HPLC peaks related to oxidation products were observed (Supplementary Fig. 25a). This observation clearly demonstrated that the presence of O2 is essential for the HMF oxidation to occur and that the plasmonic hot holes did not participate to the reaction mechanism. In another experiment, a reaction was carried out using a balloon to provide O2 to the suspension, yielding 70% DP, 9% HMFCA and 1% FDCA (Supplementary Fig. 25b,c). Using this set-up, the O2 concentration in the suspension is higher than in the case when O2 flow is applied, as the balloon works thanks to a slight gas overpressure. This shows that an excess of O2 resulted in HMF overoxidation. Relevant insights can also be retrieved by comparing the selectivity branching of TiN–RuPt under light (98% FDCA, 2% DP) and dark conditions at room temperature (61% HMFCA, 25% FDCA, 14% DP) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 23.

The crucial role of light (and heat) in driving FDCA formation is clear, while it can be argued that the rate-determining step (RDS) of HMF oxidation on TiN–RuPt is the transformation of HMFCA to FFCA (Fig. 4a, step 4). This conclusion is supported by the fact that FFCA was never observed during reaction kinetics, which implies that once it is formed, it is rapidly oxidized to FDCA. The activation energy (Ea) relative to the RDS was experimentally determined by using an Arrhenius plot for both the thermally activated (\({E}_{{\rm{a}}}^{\mathrm{thermal}}\)) and the purely photocatalytic reactions, driven by plasmonic HEs (\({E}_{{\rm{a}}}^{\mathrm{HE}}\)). For the former, we obtained \({E}_{{\rm{a}}}^{\mathrm{thermal}}\) = 80.9 ± 8.2 kJ mol−1 and for the latter it was decreased to \({E}_{{\rm{a}}}^{\mathrm{HE}}\) = 65.4 ± 7.3 kJ mol−1 (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 26). We propose that O2 dissociation may occur on the TiN–RuPt surface (NP), forming a NP–O complex that is the base acting in the various oxidation steps. By producing local heat and HEs, the RDS energy requirements are relaxed and FDCA formation rate enhanced. The Ea analysis suggests that plasmonic HEs negatively charged the NP–O catalyst, improving its Lewis base character, thus facilitating hydrogen abstraction during the RDS and eventually resulting in a 20% gain in FDCA selectivity in comparison to the thermal process (Fig. 3e,f). This hypothesis was confirmed by zeta-potential (ζ) measurements carried out under comparable conditions to those employed during catalysis. The surface of TiN–RuPt is negatively charged in aqueous suspension showing at room temperature ζr.t. = –22.2 ± 4.0 mV. At 58 °C in the dark ζthermal = –29.9 ± 5.2 mV, while under illumination ζlight = –38.5 ± 4.7 mV (Supplementary Fig. 27). Notably, ζlight is higher than ζthermal, thus showing that HEs increased the Lewis basicity of the NP–O complex. Further experimental insights on the reaction mechanism were obtained determining the kinetic isotopic effect (KIE) as the ratio of FDCA formation rate for 16O2 and 18O2 isotopes (Supplementary Note 4) both in dark thermal conditions (at T = 58 °C) and under irradiation (0.222 W cm−2). The KIEthermal obtained for the thermal process (light off) was 2.8, a value that supports the participation of O2 to the RDS of the reaction. For the photocatalytic HMF oxidation, KIElight was instead 4.2. The observation of a larger KIElight than KIEthermal confirmed that HEs mediated to some extent the HMF (HMFCA) oxidation to FDCA27,28.

a, Schematics of the proposed HMF oxidation mechanism highlighting the role of the TiN–RuPt photocatalysts during the RDS. B− stands for a generic base that in this case is the TiN–RuPt NP with the activated oxygen adsorbed. b, Adsorption energy profiles calculated using the hybrid-DFT method for molecular oxygen dissociation on TiO2–RuPt. The adsorption energies are plotted at selected geometries (reaction coordinates), which are colour-coded to match the energy profiles, with TS structures highlighted in yellow. c, Hybrid-DFT adsorption energy of O2 on TiO2–RuPt forming a NP–O complex and the adsorption energy of hydrogen on the NP–O complex along with the most favourable adsorption sites for the first and second adsorbed hydrogen atom. Bader charges corresponding to specific atoms are provided alongside the structures.

Figure 4a shows the proposed reaction pathway for the aerobic oxidation of HMF in base-free aqueous solution in the presence of a TiN–RuPt photocatalyst. The oxidation of HMF to HMFCA (path 1, Fig. 1a) proceeded rapidly through the following steps: (1) reversible hydration of the starting aldehyde to form the germinal (gem) diol, (2) hydrogen abstraction by a mild base and (3) β elimination of a hydrogen atom. In contrast, the conversion of HMFCA to FFCA (step 4) was more challenging because it required a stronger base to occur. The further oxidation of FFCA to FDCA (steps 5–7) was again very fast and proceeded similarly to steps 1–3. Several experimental studies on aerobic alcohol oxidation on ruthenium and gold on oxide supports confirmed that the release of hydride anions (as in steps 3, 4 and 7) is feasible and may occur through a direct transfer to the metallic NPs29,30,31. The required base strengths in the various steps involved in HMF oxidation were suggested by theoretical results obtained with a hybrid-DFT method studying the isolated molecules in the gas phase. Defining charged reference systems within the DFT framework under periodic boundary conditions presents challenges in accurately calculating the energy of H+ abstraction. Nonetheless, the model detailed in the Supplementary Methods addressed these obstacles by facilitating direct energy comparisons of analogous processes involving the dissociation of a hydroxyl group (–OH) to R–O− and H+, occurring in steps 2, 4 and 6. Step 6, involving H+ release from FFCA gem-diol, exhibited the lowest energy, consistent with experimental observations that did not detect FFCA in the mixture, indicating rapid progress of subsequent steps. Abstraction of H+ from the HMF gem-diol (step 2) required an additional 0.48 eV, while releasing H+ from HMFCA (half of step 4) demanded 0.60 eV more energy than step 6, implicitly suggesting the need of a stronger base to occur. The HMF structure partially stabilized the charge on carbon atoms neighbouring the aromatic ring (labelled as β-C in Fig. 4a), thereby enabling easier abstraction of a hydrogen atom bound to β-C (Supplementary Note 5).

To further support the proposed reaction mechanism, we investigated O2 adsorption on TiO2(001) supporting bimetallic NPs (see Supplementary Fig. 9 for the geometrical models and an explanation of the nomenclature) using a hybrid-DFT method. The calculated O2 potential-energy profile on TiO2–Ru7upPt7 shows an activated dissociation process with a barrier of 0.23 eV (Fig. 4b). In the transition state (TS), O2 adopted a peroxo state, in agreement with electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) experiments. While O2 splitting is more favourable than on TiO2–Pt14, the oxygen adsorption energy (\({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{O}}}\) = –2.6 eV) per oxygen atom remained similar to that on TiO2–Ru14 (\({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{O}}}\) = –2.7 eV) due to the dominant role of ruthenium atoms in oxygen binding (Supplementary Figs. 28–34 and Supplementary Table 9), in agreement with CO DRIFT spectroscopy after O2 exposure (Fig. 1c). In the case of TiO2–Ru7Pt7up (Supplementary Fig. 29), a comparable barrier of 0.20 eV emerged. However, \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{O}}}\) per oxygen atom was reduced to –1.0 eV. In the mixed NP, one would expect \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{O}}}\) of both oxygen atoms to be the sum of \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{O}}}\) of a single oxygen atom on TiO2–Ru14 and of a single oxygen atom on TiO2–Pt14 (−0.9 eV), totalling −3.6 eV. The calculated value in TiO2–Ru7Pt7up is notably smaller (−2.0 eV). Consequently, oxygen is less strongly bound to the ruthenium atom that is accompanied by platinum atoms in TiO2–RuPt. This set of computational results correlates well with the observed photocatalytic activity (Fig. 3a) as the stronger binding of oxygen to ruthenium atoms may induce a surface poisoning and explain why TiN–Ru was not able to fully transform HMF, while its product selectivity was mainly oriented toward HMFCA formation. The opposite situation was observed for TiN–Pt. The intermediate oxygen-binding strength provided by TiN–RuPt results in the best performance, in accordance with the Sabatier principle.

To deepen our understanding of the role of NP–O in hydrogen abstraction (both H+ and H−) during the RDS, the hydrogen adsorption energy (\({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{H}}}\)) on the catalyst surface was investigated using a hybrid-DFT approach (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Figs. 35–43 and Supplementary Tables 10–17). Ideally, the catalyst should possess two active sites, one for adsorbing H+ to facilitate steps 2, 4 and 6 of the reaction (Fig. 4a), and another for accepting H− to enable steps 3, 4 and 7. Both processes involved the –CH2OH group of HMFCA or the –CH(OH)2 group of gem-diols, necessitating close proximity of these active sites. The catalyst’s ability to capture H+, or its basicity, was assessed by modelling the adsorption energy of a hydrogen atom on the catalyst surface, resulting in an adsorbed proton. An enhanced basicity was crucial for facilitating all oxidation steps, while subsequent release of hydride anions was essential to complete the oxidation reaction. The catalyst’s potential to accept hydride anions was evaluated similarly to its basicity, with particular attention to configurations in which hydrogen acquired a negative charge after adsorption. Due to computational constraints and the challenges of accurately modelling charged systems, all calculations of hydrogen adsorption on NP surfaces were conducted under neutral conditions (Supplementary Note 5). Nevertheless, these provided valuable insights into the reaction mechanism. In the case of TiO2–Ru14, a hydrogen atom adsorbed as anion onto a ruthenium atom bound to oxygen resulted in \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{H}}}\) = –1.1 eV, which is crucial for the H− elimination process. The second hydrogen tended to adsorb as cation at the oxygen strongly bonded to ruthenium (–0.7 eV), which makes the oxygen atoms adsorbed on this NP a weak base. When considering TiO2–Pt14, hydrogen adsorbed as a cation on oxygen with a large \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{H}}}\) of –1.6 eV. This oxygen exhibited a Brønsted base character and was relatively weakly bound to platinum, as elucidated above. The large \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{H}}}\) of a second H+ on another oxygen atom was reduced to –1.2 eV, which is still higher than that on the oxygen atoms bound to the TiO2–Ru14. This stronger base behaviour may underlie the superior performance of the photocatalysts containing platinum rather than only ruthenium to steer product selectivity toward FDCA. The TiO2–RuPt model combines elements from the two monometallic scenarios. Hydrogen cations exhibited the strongest binding affinity to the oxygen atoms bound to the platinum atoms, while the binding on the oxygen atom bound to the ruthenium atom was less favourable. Interestingly, in some instances, the presence of ruthenium atoms also enhanced the \({E}_{\mathrm{ads}}^{{\rm{H}}}\) of H− in proximity to platinum atoms, a factor that may be crucial for the oxidation of HMFCA to FFCA. This accounted for the better performance of TiN–RuPt nanocubes, whose Brønsted base character may be further enhanced by plasmonic HEs as supported by zeta-potential measurements and KIE experiments.

Finally, nudged-elastic band (NEB) calculations were performed to investigate HMFCA to FFCA oxidation (the RDS) on TiO2–Ru7upPt7, using explicit models of the molecules (Fig. 5). The reaction initiated with the HMFCA molecule adsorbing on the NP, exhibiting an adsorption energy of –1.12 eV, predominantly due to the van der Waals interactions. The –CH2OH group, prior to oxidation, bonded to a ruthenium atom, thereby positioning the β-H atoms closer to other ruthenium atoms. The transfer of one of these hydrogen atoms in the form of a hydride anion to the NP surface required an energy of 1.52 eV, which is relatively modest, given that it leaves behind a positively charged molecule (Bader charge, 0.37e) as an intermediate. A substantial reduction in this energy requirement arose from the formation of a hydrogen bond between the –OH group in HMFCA and an oxygen atom/ion adsorbed on the NP surface. If the HMFCA molecule utilized all the energy gained during its adsorption, it would need an additional energy of only 0.39 eV to reach the TS. Once it was reached, H+ from the –OH group was transferred to the oxygen atom adsorbed on the NP surface, neutralizing the HMFCA-H− intermediate, and forming the FFCA molecule, which released an energy of 1.51 eV. It is expected that the energy of the TS could be lowered if the H− and H+ transfer occurred simultaneously. However, the complex nature of the TS calculations currently prevents deeper investigations of this aspect. The last step of the reaction involved FFCA desorption. Although its adsorption energy was smaller than that of HMFCA due to fewer hydrogen bonds being involved, it needed to overcome a barrier of 0.72 eV caused by the van der Waals interactions. After overcoming this barrier, the FFCA molecule was released and the NP relaxed, reaching a total energy only 0.07 eV higher than before the FFCA desorption. A total of 1.04 eV of energy was released once the entire reaction was complete.

a, Adsorption energy profiles extracted from NEB calculations describing the various steps involved in the RDS of HMF oxidation, that is, HMFCA oxidation to FFCA, in the presence of molecular oxygen and TiO2–RuPt. b, The corresponding structures for each predicted step, with the TS highlighted in red. All energy values are relative to the initial state with the HMFCA molecule in the gas phase and a relaxed TiO2–Ru7upPt7 catalyst with two adsorbed oxygen atoms.

Overall, both experimental and theoretical results support the picture that molecular oxygen is activated through a unique mechanism on the surface of TiN–RuPt and it is crucial for FDCA formation. This is further confirmed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis of the reaction mixture obtained from KIE experiments under illumination (Supplementary Fig. 44). The mass spectrum shows that the most prominent peak has m/z = 160, corresponding to the FDCA molecule bearing two 18O deriving from the 18O2 used as a reactant. This underlies a dynamic exchange between the light-activated 18O atom present on the surface of the NP–18O complex, water and HMF, via gem-diol formation, which leads to 18O atom incorporation in the FDCA molecule32.

Conclusions

In this study, we introduce a plasmonic antenna–reactor photocatalyst consisting of TiN and RuPt NPs that under NIR light and base-free conditions exhibits the full and selective conversion of HMF to FDCA. By using electromagnetic simulations, we disclose the formation of plasmonic photocatalytic hot spots, in which nanoscale patches of hot electrons are formed in various key components of the photocatalyst such as on the reactor surface and at the antenna–reactor interface. We show that our plasmonic photocatalyst shows a distinct reactivity in comparison to semiconductors and metal–semiconductor hybrids. In contrast to these systems, the hot electrons generated by the photoexcitation of TiN–RuPt nanocubes do not favour the formation of radical species, but rather enhance the basic character of the photocatalyst–oxygen complex. An atomistic model of the molecular mechanism, including oxygen dissociation at the photocatalyst surface and hydrogen removal during the RDS, is provided by DFT calculations. We critically examine the thermal and nonthermal catalytic activity, highlighting that the action of plasmonic hot electrons ensures a marked increase in FDCA selectivity and a faster HMF conversion in comparison to the temperature rise alone.

Methods

Photocatalyst preparation

In a typical synthesis of photocatalysts, 100 mg of commercial TiN nanocubes (PlasmaChem, ∼50 nm average size) was suspended in 20 mL of ethylene glycol anhydrous (99.8%) and sonicated for 20 min. An appropriate amount of metal precursors, namely, potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (K2PtCl4, Sigma-Aldrich) for the preparation of TiN–Pt, ruthenium(III) chloride (RuCl3, Sigma-Aldrich) for TiN–Ru, and both for TiN–RuPt, were dissolved in 2.5 mL ethylene glycol and added dropwise to the aforementioned suspension of TiN nanocubes under vigorous stirring and stirred for 30 min in an ice bath. Subsequently, 1 mL of 0.2 M NaOH aqueous solution (Alfa Aesar) was added dropwise to adjust the solution pH to ∼12, followed by stirring for 10 min. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 5 min under a continuous nitrogen flow to remove the dissolved O2 and then placed in a preheated water bath at 150 °C for 3 h under sealed conditions. Upon completion of the reaction, the TiN nanocubes were washed once with 1:1 water/ethanol mixture and twice more with anhydrous ethanol. Centrifuged samples were then concentrated in 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol and were treated with 10 vol% HCl to clean the TiN surface stirring overnight at room temperature. Next day the samples were centrifuged three times with a 1:1 water/ethanol mixture. The as-synthesized metal-loaded TiN nanocubes were concentrated in 5 mL of anhydrous ethanol and dried in an oven at 80 °C. The so-obtained powders were reduced in a furnace under a H2/N2 flow (10:90 vol%, 200 sccm) for 1 h at 200 °C. A similar synthesis procedure was applied but varying the platinum and ruthenium loading amount. The Ru/Pt ratios indicated in the manuscript are based on nominal metal loading.

Characterization

The structures of catalyst samples were determined by powder X-ray diffraction analysis performed on an X’Pert PRO MPD diffractometer (PANalytical) equipped with iron-filtered cobalt Kα radiation (40 kV, 30 mA, λ = 0.1789 nm). The XPS measurements were taken in three different locations on the investigated samples using a PHI 5000 VersaProbe II XPS system (Physical Electronics) with a monochromatized aluminium Kα source (15 kV, 50 W) and a photon energy of 1,486.7 eV. The low-resolution imaging of catalyst morphology was obtained with a JEOL transmission electron microscope equipped with a LaB6 emission gun and operating at 160 kV. High-resolution micrographs and scanning transmission electron microscope elemental mapping were acquired using a FEI Titan HRTEM microscope equipped with an X-FEG electron gun operating at 80 kV. Absorption spectra were measured using an ultraviolet−visible spectrophotometer (SPECORDS 600, Analytik Jena). The metal loading was determined using ICP−MS (Agilent Technologies 7900). ICP-MS analysis of platinum- and ruthenium-supported TiN catalysts involved digesting the catalysts (20 mg) in a 1:3 mixture of concentrated HNO3 (65%) and HCl (36%) using a microwave oven for 20 min. Calibration solutions with a series of platinum and ruthenium concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2 ppm) were prepared by diluting a 50-ppm standard solution. The catalyst solutions for platinum and ruthenium determination were prepared by heating the catalysts in 4.0 mL of the acid mixture at 100 °C, transferring the mixture to a 50-mL flask, and adding deionized water to reach a total volume of 50 mL. XAS measurements at the platinum L3 edge in both transmission (for platinum foil) and fluorescence (for TiN–RuPt) mode were performed at the BL14W1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (see details in Supplementary Methods). Infrared spectra were collected in diffuse reflectance mode using a Bruker Equinox 55 spectrometer equipped with a Spectra Tech DRIFT accessory (model 0030-011) and a mercury cadmium telluride detector, averaging 128 interferograms. The reflectance data were successively converted in pseudoabsorbance: A = −log R, where R is the measured reflectance. The catalysts were diluted in silicon powder. Before performing CO adsorption experiments, the samples were always reduced at 200 °C for 1 h in H2 at 50 mbar. Then, after cooling to room temperature, CO at 50 mbar was dosed and the excess of CO in the gas phase was subsequently outgassed. For the experiments studying the O2 effect, O2 at 50 mbar was dosed at room temperature after the reduction step and then outgassed before CO adsorption. Spin-trapping experiments were carried out on an X-band EPR benchtop instrument (ADANI). Instrument settings: microwave power, 5 mW; modulation amplitude, 0.1 mT; sweep time, 40 s; time constant, 0.031 s; three scans. Measurements of the hydrodynamic diameters of nanocrystals and the zeta potentials were carried out using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern) instrument.

Electromagnetic and photophysical simulations

The simulations were carried out using classical electrodynamic formalism implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics, with the aim of studying the optoelectronic and photothermal properties of our photocatalytic plasmonic hybrids. Our model included a 40-nm TiN nanocube with a corner radius of 8 nm in water; the TiO2 shell of the TiN nanocube was 1.5 nm. Additionally, 16 RuPt semispheres, each with a diameter of 5.5 nm (taken from experimental measurements), were evenly distributed on each nanocube facet. The calculations assumed an average over all six orientations of the nanocube for the incident electromagnetic beam propagating in the +z direction; the computations were done for a single NP. Using these conditions, the calculations produced the absorption, scattering and extinction cross-sections, the surface field maps, the surface T-maps, and the HE generation rates at the interfaces of our nanostructure. The local dielectric functions ε for the components (TiN, TiO2, Ru and Pt) were taken from the literature33,34,35,36. For the RuPt, we took the average εRuPt = (εRu + εPt)/2; for local thermal parameters of the RuPt, we used the same averaging approach. The matrix’s dielectric constant was taken as 1.8 (water) as commonly used in optical calculations of a solution. For the HE generation rates at the interfaces we used our self-consistent quantum-electromagnetic formalism20,37. For the T-surface maps, we utilized the thermal-diffusion module of COMSOL fed with the experimental numbers for the local heat capacity and heat conductivity (Supplementary Table 5).

Photocatalytic experiments

The photoreactor used was a double-neck quartz tube (10 mL) in which 2 mg of plasmonic photocatalyst was sonicated in water and then added to the reaction solution (HMF and water) under stirring. The tube was then closed with a rubber cap and a needle was used to vent the reactor under an O2 flow rate of 5 mL min−1. The light source was a red light-emitting diode (LED) (Thorlabs SOLIS-740C, λ = 740 nm) kept at 5 cm from the centre of the reaction solution. The initial HMF concentration and volume of suspension were 2.5 mM and 3.1 mL, respectively. Before switching the LED on, the reaction suspension was stirred for 15 min in the dark to reach adsorption/desorption equilibrium. The dark reactions were carried out using a black box to prevent ambient light penetration, while a thermostatic water bath was used to conduct dark thermal experiments. The quantitative analysis of reactants and products was performed on a HPLC system (Thermo Scientific Dionex UltiMate 3000; Waters 2487) equipped with a C18 AQ column using an eluent consisting of 5 mM H2SO4 in ultrapure water at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1 at 50 °C. Prior to HPLC analysis, the reaction suspensions were filtered using 0.2-mm PTFE filters. KIE experiments were carried for 2 h in the presence of isotope labelled 18O2 (97 at.% 18O, Sigma-Aldrich) or normal 16O2 flow, keeping the other reaction parameters fixed. The temperature for dark thermal experiments was set at 58 °C, while the photocatalytic reactions were carried out using the 740-nm LED at a power density of 0.222 W cm−2.

DFT calculations

DFT calculations were carried out using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)38,39,40,41, which uses the projected augmented wave method42,43 to describe the electron–ion interactions. The exchange and correlation energy of electrons was treated within a generalized-gradient approximation using the revised Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional44. Dispersion energies were accounted for using the DFT-D3 method45. An on-site Hubbard U correction was applied to the d electrons of specific elements: titanium, 6 eV; oxygen, 6 eV; ruthenium, 2 eV; platinum, 2 eV. For the final geometries of TiO2-based systems, including adsorbed oxygen molecules and atoms, and hydrogen atoms, static calculations were executed using a hybrid functional of Heyd, Scuseria and Ernzerhof (HSE03)46, motivated by its correct predictions of the properties of TiO2 without the need for an empirical parameter such as U. The basis set of plane waves was limited to 415 eV. Symmetry was switched off in all calculations.

Our computational models are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9 and described in Supplementary Note 5. Ionic relaxations were executed using the conjugate gradient algorithm (initial steps) and the RMM-DIIS algorithm (final steps), until the forces acting on atoms dropped below 0.025 eV Å−1. Electron relaxations in metal-based reference systems were performed using a combination of Davidson and RMM-DIIS algorithms. For relaxation in TiO2 systems, a preconditioned conjugated gradient algorithm was used, continuing until the change in total energy between two consecutive self-consistent steps was smaller than 10−6 eV. To sample the Brillouin zone, a Γ-point-centred 6 × 6 × 1 k-point mesh was used for metal-based systems, while a 2 × 2 × 1 k-point mesh was used for TiO2-based systems. Due to their high computational demands the HSE03 calculations were performed only for the Γ-point.

The NEB method, compiled with the Transition State Tools for VASP (VTST)47, was used to determine the potential energy profile for the dissociation of the O2 molecule and of the HMFCA to FFCA oxidation. The limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (LBFGS)48 algorithm was utilized for the NEB calculations.

Gibbs binding energy assessments were performed by inspecting the vibrational modes of O2 in vacuum as well as in the TiO2–NP and TiO2–NP + O2 systems. These evaluations were conducted at a fixed total supercell magnetic moment, whose value was selected by comparing the total energies of different spin isomers, with total magnetic moments ranging from 0 to 16μB.

Data availability

All data in the manuscript and the Supplementary Information are available from Zenodo via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17256929 (ref. 49).

References

Lee, K., Jing, Y., Wang, Y. & Yan, N. A unified view on catalytic conversion of biomass and waste plastics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 635–652 (2022).

Kawai, T. & Sakata, T. Conversion of carbohydrate into hydrogen fuel by a photocatalytic process. Nature 286, 474–476 (1980).

Wu, X. et al. Solar energy-driven lignin-first approach to full utilization of lignocellulosic biomass under mild conditions. Nat. Catal. 1, 772–780 (2018).

Wakerley, D. W. et al. Solar-driven reforming of lignocellulose to H2 with a CdS/CdOx photocatalyst. Nat. Energy 2, 17021 (2017).

Luo, N. et al. Visible-light-driven coproduction of diesel precursors and hydrogen from lignocellulose-derived methylfurans. Nat. Energy 4, 575–584 (2019).

Ren, P. et al. Stepwise photoassisted decomposition of carbohydrates to H2. Joule 7, 333–349 (2023).

Biddy, M. J., Scarlata, C. & Kinchin, C. Chemicals from Biomass: A Market Assessment of Bioproducts with Near-Term Potential (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2016); https://doi.org/10.2172/1244312

Werpy, T. & Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass: Vol. I—Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas (Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2004); https://doi.org/10.2172/15008859

Zhang, Z. & Deng, K. Recent advances in the catalytic synthesis of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid and its derivatives. ACS Catal. 5, 6529–6544 (2015).

Meng, Y., Yang, S. & Li, H. Electro- and photocatalytic oxidative upgrading of bio-based 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemSusChem 15, e202102581 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid using O2 and a photocatalyst of Co-thioporphyrazine bonded to g-C3N4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 14775–14782 (2017).

Xia, T. et al. Sunlight-driven highly selective catalytic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural towards tunable products. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204225 (2022).

Yu, W. et al. Mechanistic insights into the selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over Au/TiO2 catalysts under photoexcited and dark states. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 13116–13125 (2023).

Cortés, E. et al. Challenges in plasmonic catalysis. ACS Nano 14, 16202–16219 (2020).

Swearer, D. F. et al. Heterometallic antenna−reactor complexes for photocatalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8916–8920 (2016).

Rej, S. et al. Determining plasmonic hot electrons and photothermal effects during H2 evolution with TiN–Pt nanohybrids. ACS Catal. 10, 5261–5271 (2020).

Pecoraro, C. M. et al. Pt–TiO2 catalysts for glycerol photoreforming: comparison of anatase, brookite and rutile polymorphs. Chem. Commun. 60, 3782–3785 (2024).

Chin, S. Y., Williams, C. T. & Amiridis, M. D. FTIR studies of CO adsorption on Al2O3- and SiO2-supported Ru catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 871–882 (2006).

Lu, G.-Q., White, J. O. & Wieckowski, A. Vibrational analysis of chemisorbed CO on the Pt(111)/Ru bimetallic electrode. Surf. Sci. 564, 131–140 (2004).

Santiago, E. Y. et al. Efficiency of hot-electron generation in plasmonic nanocrystals with complex shapes: surface-induced scattering, hot spots, and interband transitions. ACS Photonics 7, 2807–2824 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. Quantifying hot carrier and thermal contributions in plasmonic photocatalysis. Science 362, 69–72 (2018).

Sivan, Y., Baraban, J., Un, I. W. & Dubi, Y. Comment on ‘Quantifying hot carrier and thermal contributions in plasmonic photocatalysis’. Science 364, eaaw9367 (2019).

Baffou, G., Bordacchini, I., Baldi, A. & Quidant, R. Simple experimental procedures to distinguish photothermal from hot-carrier processes in plasmonics. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 108 (2020).

Mascaretti, L. et al. Challenges in temperature measurements in gas-phase photothermal catalysis. Joule 6, 1727–1732 (2022).

Gargiulo, J. et al. Impact of bimetallic interface design on heat generation in plasmonic Au/Pd nanostructures studied by single-particle thermometry. Nat. Commun. 14, 3813 (2023).

Rej, S. et al. Colloidal titanium nitride nanobars for broadband inexpensive plasmonics and photochemistry from visible to mid-IR wavelengths. Nano Energy 104, 107989 (2022).

Bonn, M. et al. Phonon- versus electron-mediated desorption and oxidation of CO on Ru(0001). Science 285, 1042–1045 (1999).

Christopher, P., Xin, H., Marimuthu, A. & Linic, S. Singular characteristics and unique chemical bond activation mechanisms of photocatalytic reactions on plasmonic nanostructures. Nat. Mater. 11, 1044–1050 (2012).

Yamaguchi, K., Kim, J. W., He, J. & Mizuno, N. Aerobic alcohol oxidation catalyzed by supported ruthenium hydroxides. J. Catal. 268, 343–349 (2009).

Fristrup, P., Johansen, L. B. & Christensen, C. H. Mechanistic investigation of the gold-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols. Catal. Lett. 120, 184–190 (2008).

Kantam, M. L. et al. Aerobic alcohol oxidation by ruthenium species stabilized on nanocrystalline magnesium oxide by basic ionic liquids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 350, 1225–1229 (2008).

Siankevich, S. et al. A novel platinum nanocatalyst for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid under mild conditions. J. Catal. 315, 67–74 (2014).

Guler, U., Kildishev, A. V., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Plasmonics on the slope of enlightenment: the role of transition metal nitrides. Faraday Discuss. 178, 71–86 (2015).

Siefke, T. et al. Materials pushing the application limits of wire grid polarizers further into the deep ultraviolet spectral range. Adv. Opt. Mater. 4, 1780–1786 (2016).

Choi, W. S. et al. Dielectric constants of Ir, Ru, Pt, IrO2: contributions from bound charges. Phys. Rev. B 74, 205117 (2006).

Rakić, A. D., Djurišić, A. B., Elazar, J. M. & Majewski, M. L. Optical properties of metallic films for vertical-cavity optoelectronic devices. Appl. Opt. 37, 5271–5283 (1998).

Movsesyan, A. et al. Plasmonic nanocrystals with complex shapes for photocatalysis and growth: contrasting anisotropic hot-electron generation with the photothermal effect. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102663 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H–Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Liu, D. C. & Nocedal, J. On the limited memory BFGS method for large scale optimization. Math. Program. 45, 503–528 (1989).

Naldoni, A. Near-infrared plasmonic activation of molecular oxygen for selective oxidation of biomass derivatives. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17256929 (2025).

Acknowledgements

A.N. acknowledges the support from Project CH4.0 under the MIUR programme Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023–2027 (CUP D13C2200352001) and from the European Union-NextGeneration EU Programme, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.1 PRIN 2022 PNRR, Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR), CUP D53D23017090001, ID P2022J5NAN ‘Refractory plasmonic metasurfaces for solar thermal catalytic CO2 conversion’ (RESOLCAT). P.B., J.N. and M.O. acknowledge the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic through the e-INFRA CZ (ID 90254). J.N. acknowledges support by Palacký University Olomouc (project IGA_PrF_2025_003). Š.K. acknowledges support by the European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence for Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition from the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic. Š.K., M.O. and P.B. acknowledge the ERDF/ESF project TECHSCALE (CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004587). S. M. H. Hejazi is acknowledged for XPS measurements. E.Y.S. and A.O.G. thank the Nanoscale and Quantum Phenomena Institute at Ohio University for continuous support via generous graduate fellowships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and coordination: A.N. Photocatalyst synthesis: M.K. and S.R. Catalytic experiments: M.K. and S.R. XAS/EXAFS measurements and data interpretation: Z.X., H.Z. and P.F. CO DRIFT spectroscopy: L.M. Electromagnetic simulations: E.Y.S. and A.O.G. DFT calculations: J.N., M.O. and P.B. EPR spectroscopy: S.L. Data analysis and discussion: all authors. Supervision and funding: M.O., Š.K., A.O.G., P.B. and A.N. Writing: M.K., S.R. and A.N. Reviewing and editing: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Catalysis thanks Moritz Kühnel and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–44, Notes 1–5, Tables 1–17 and Methods.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, M., Rej, S., Navrátil, J. et al. Near-infrared plasmonic activation of molecular oxygen for selective oxidation of biomass derivatives. Nat Catal 8, 1370–1381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-025-01454-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41929-025-01454-y