Abstract

Antibiotic-induced dysbiosis in the fish gut causes significant adverse effects. We use fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to accelerate the restoration of florfenicol-perturbed intestinal microbiota in koi carp, identifying key bacterial populations and metabolites involved in the recovery process through microbiome and metabolome analyses. We demonstrate that florfenicol disrupts intestinal microbiota, reducing beneficial genera such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Romboutsia, and Faecalibacterium, and causing mucosal injuries. Key metabolites, including aromatic amino acids and glutathione-related compounds, are diminished. We show that FMT effectively restores microbial populations, repairs intestinal damage, and normalizes critical metabolites, while natural recovery is less effective. Spearman correlation analyses reveal strong associations between the identified bacterial genera and the levels of aromatic amino acids and glutathione-related metabolites. This study underscores the potential of FMT to counteract antibiotic-induced dysbiosis and maintain fish intestinal health. The restored microbiota and normalized metabolites provide a basis for developing personalized probiotic therapies for fish.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotics are commonly administered to livestock, poultry, and fish for disease treatment and prevention1. This extensive use leads to specific changes in the intestinal microbial diversity, composition, and functionality in these animals, thereby facilitating the post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens2,3. Prior research in mammals and humans has indicated that dysbiosis of intestinal microbiota can induce changes in the generation of metabolic products such as fatty acids and amino acids and is usually accompanied by increased gut permeability and low-grade endotoxemia4. With regard to fish, side effects of antibiotics can occur in both sick and healthy individuals when they are exposed to a therapeutic dosage of the drug in fish farming contexts5. When antibiotics are used for the treatment of fish diseases, these side effects often go unnoticed, thereby frequently resulting in repeated bacterial infections.

Although probiotics are considered a suitable alternative to antibiotics in aquatic animals, they are currently used more as prophylactics than as therapeutic agents6. In aquaculture, probiotics are often used indiscriminately, either through water routines (immersion) or as feed additives. Certain strains that are primarily designed for immersion purposes are occasionally used as feed additives as well7. Probiotic strains from both cultured water environments and mammalian sources are commonly used as feed additives for fish. However, these strains may not survive and colonize the intestines of fish due to the differing composition and function of the intestinal microbiota in fish compared to those in mammals or aquatic environments6. A key reason for the suboptimal use of probiotics in fish farming and the scarcity of specialized commercial products for fish feed additives is the limited understanding of intestinal microbiota, with functional bacterial taxa yet to be identified.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is the transfer of fecal microbiota from a healthy donor into the gastrointestinal tract of a recipient to restore the composition and function of the recipient’s gut microbiota8. Over the past decade, FMT has been used in clinical medicine to treat gastrointestinal diseases such as recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection9, inflammatory bowel disease10, and irritable bowel syndrome11, as well as certain non-gastrointestinal diseases12,13,14. FMT is also used as an experimental treatment for a variety of diseases, exploring the role of intestinal microbiota in disease pathology and providing significant mechanistic insight in humans15,16, laboratory animals17,18, and food animals19,20,21. As an experimental tool, FMT offers interesting opportunities to determine the relationships between intestinal microbiota and certain biological characteristics, such as miRNA expression in the human intestine22, lifespan in African turquoise killifish23, and central nervous system disorder in rats24.

Research has demonstrated that FMT restores the intestinal microbiota in mammals disturbed following antibiotics use25; however, differences between FMT-induced restoration and natural bacterial succession remain unknown. Especially in fish, little is known about the functional bacterial taxa and metabolites associated with the recovery of intestinal microbial communities.

Florfenicol is one of the most widely used antibiotics in fish farming around the world due to its broad-spectrum bacteriostatic efficacy26. A study reported that dietary florfenicol reduced the total intestinal bacterial counts in fish27. The Asian-origin koi carp (Cyprinus carpio var. koi), which is currently listed among the most important ornamental species, can be reared worldwide. Its adaptability to long-term indoor breeding and biological features such as omnivory, long intestines without stomach, and functional differentiation of different intestinal segments make it an ideal subject for studies on intestinal microbiota28.

In this study, we used FMT as an experimental treatment to restore the intestinal microbiota in koi carp, which was disrupted by florfenicol. The objectives of this study were to (1) assess the efficacy of FMT in restoring antibiotic-induced intestinal microbiota dysbiosis in a fish model; and (2) determine the functional bacterial taxa and metabolites that may be associated with the restoration of disturbed intestinal microbiota. To achieve these objectives, we investigated the intestinal microbiome, fecal metabolome, and histological features of koi carp that were administrated with florfenicol or treated with FMT after the discontinuation of florfenicol. These analyses revealed that florfenicol administration in koi carp significantly disrupted the intestinal microbiota, reducing both beneficial and potentially pathogenic bacterial genera. They also showed that, compared to natural recovery, FMT accelerates the restoration of florfenicol-disturbed intestinal microbiota in the fish. The microbial populations and key metabolites associated with this restoration were identified, laying the foundation for developing probiotic cocktails for personalized therapeutic strategies in fish.

Results

Florfenicol alters the composition of intestinal microbiota

Fish in the florfenicol-treated group (FFNC) and the control group (CG-7) were fed diets with and without florfenicol supplementation, respectively, for seven days (Fig. 1; stage 1). The alteration of the composition of intestinal microbiota caused by florfenicol was analyzed using 16S rRNA gene high throughput sequencing. The number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in the CG-7 group was significantly higher than that in the FFNC group, as shown by a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test (p = 0.018; Fig. 2a). Alpha-diversity metrics, specifically Chao 1’s index (p = 0.0053) and Shannon’s index (p = 0.011), analyzed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test, were significantly lower in the FFNC group compared with the CG-7 group (Fig. 2b, c). This indicates a significant decrease in microbial species richness and diversity due to florfenicol intake. Beta-diversity analysis further demonstrated a distinct clustering of microbiota composition between the FFNC and CG-7 groups, as revealed by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the weighted UniFrac distance (Fig. 2d; p = 0.001, AMOVA). Similar results were revealed by hierarchical clustering, where fish in the FFNC group separated from the CG-7 group (Fig. 2e).

Briefly, fish were fed diets either supplemented with florfenicol (FFNC group) or without florfenicol (CG-7 group) for seven days. Following the discontinuation of florfenicol, the remaining florfenicol-treated fish were randomly divided at 1:1 ratio into two groups. One group received fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT; FFNC + FMT group), while the other was allowed to recover naturally (FFNC + PBS; where PBS substituted for donor fecal microbiota). The remaining fish in the CG-7 group continued their original diets for an additional seven days (CG-14 group). The schematic diagram was created with Adobe Illustrator 2023 v27.0.

a Comparison of OTU numbers of intestinal microbiota in the FFNC and CG-7 groups. (b, c) Comparison of alpha-diversity in the intestinal microbiota using the Chao1 index (b) and Shannon’s index (c) between the FFNC and CG-7 groups. d, e Comparison of beta-diversity in the intestinal microbiota using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) (d) and UPGMA hierarchical clustering (e) between the FFNC and CG-7 groups. Statistical significance was determined based on the weighted UniFrac distance and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). Lines in the PCoA plot connect each sample point to the center of gravity of its respective sample group. f Average relative abundance of prevalent microbiota at the phylum level in the intestines of fish from the CG-7 and FFNC groups. Stacked bar plot shows the top five most abundant taxa in the two groups, with each bar representing the average relative abundance of each taxon within each group. See Supplementary Data 1 for the source data used in this panel. g Taxonomic cladogram obtained from LEfSe analysis showing bacterial taxa that were differentially abundant in the CG-7 and FFNC groups; bacterial taxa with an LDA score of 3.5 were selected as biomarker taxa (phylum, genus, and species); red color indicates bacterial taxa with increased abundance in the CG-7 group; blue color indicates those in the FFNC group. For (a–g), there are 11 biological replicates per treatment (n = 11). For panels (a–c), the components of the box plot include a center line representing the median, an upper limit representing the upper quartile, and a lower limit representing the lower quartile. In the box plot, the whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values of the data, and all individual data points are displayed as dots indicating individual values of the tested samples. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test, with comparisons shown as exact p-values.

The microbiome of fish in the CG-7 group was dominated by the phyla Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes, similar to that in the FFNC group (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 1a, Supplementary data 1). However, their abundances differed between these two groups (Supplementary Fig. 1b–e). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) determination (with an LDA score > 3.5) revealed that florfenicol decreased the relative abundances of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Cyanobacteria in the intestines (Fig. 2g). At the genus level, florfenicol caused a notable reduction in Romboutsia, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium, all of which are benign to fish29. Additionally, it decreased Stenotrophomonas, Aeromonas, Vibrio, Chryseobacterium, and Acinetobacter, all of which are potentially pathogenic to fish30 (Fig. 2g).

Florfenicol causes intestinal mucosa injuries

To investigate the intestinal mucosa injuries caused by florfenicol, the histomorphological characteristics and gene expression of tight junction proteins in the fish intestines were studied. Observations with a scanning electron microscope showed fractured and shed mucosal surfaces with many irregularly round-shaped sunken pits in the foregut and hindgut of fish from the FFNC group, in contrast to the CG-7 group (Fig. 3a). Histological examination showed that the fish in the FFNC group exhibited a higher histopathological score (Fig. 3b, c) and a lower muscle thickness (Fig. 3d; foregut, p = 0.31; hindgut, p = 0.012; two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test) in the intestine tissues, compared with the normal fish. The gene expressions of ZO-1 (p = 0.038) and occludin (p = 0.50), which are two tight junction proteins essential for the integrity of the intestinal barrier31, were lower in the FFNC group compared to the CG-7 group (Fig. 3e; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test), suggesting a decrease in intestinal barrier integrity after florfenicol intake.

a Morphology of the foregut and hindgut observed under a scanning electron microscope. Scale bar = 500 μm. b Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the foregut and hindgut. Scale bar = 200 μm. c Histological scores of the foregut and hindgut (n = 27/group). d Comparison of muscle layer thickness in the foregut and hindgut between the FFNC and CG-7 groups (n = 27/group). Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the corresponding p-values are indicated. e Relative mRNA expression levels of ZO-1 and occludin throughout the intestine (n = 3/group). Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test and the corresponding p-values are indicated. For (c–e), dots represent the values of individual measurements, and the data are presented as means ± standard deviations.

Florfenicol causes changes in the fecal metabolome

Using mass spectrometry-based untargeted metabolomics, we analyzed fecal metabolic profiles for fish in the FFNC and CG-7 groups. Orthogonal partial least-squares discrimination analysis (OPLS-DA) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b) and univariate statistical analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2c) revealed 147 differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) that distinguished the two groups (Supplementary data 2). A hierarchical clustering heat map also showed similar clustering patterns of detected molecular features within each group (Supplementary Fig. 2d). These metabolites were significantly altered in KEGG metabolic pathways including nucleotides, amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids, and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites (p < 0.05, Fig. 4a, Supplementary data 3).

a A heatmap displays significant changes in metabolites within pathways categorized by the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). b A heatmap illustrates variations in the relative concentrations of carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids in the fecal metabolome of koi carp treated with or without florfenicol. c A heat map of Spearman’s rank correlations demonstrates the associations between metabolites and bacterial genera, both of which had different abundances between the FFNC and CG-7 groups. Pink squares indicate positive associations, blue squares indicate negative associations, and statistical significance is marked directly on the squares (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001). See Supplementary Data 4 for the source data used in this panel. In (a–c), both CG-7 and FFNC groups included 11 samples each.

Florfenicol intake modified lipid metabolism by reducing primary bile acids like taurocholate, glycocholic acid, and taurochenodeoxycholate (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 2e). Carbohydrate metabolism was affected by increased levels of stachyose, raffinose, and the metabolic intermediate 2-Dehydro-3-deoxy-D-gluconate (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 2e). It also led to reduced concentrations of aromatic amino acids (L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, L-phenylalanine, and L-histidine) and their metabolic intermediates including phenyllactic acid, indole, dopamine, tyramine, trans-cinnamate, and 1-methylhistamine. Additionally, amino acids such as L-citrulline, L-arginine, L-glutamine, L-asparagine, and D-proline were also decreased in the FFNC group compared to the control group (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Spearman correlation analysis revealed strong associations between the altered bacterial genera in the FFNC and CG-7 groups (Fig. 2g) and the identified DEMs (Fig. 4b). Genera such as Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, and an unidentified Ruminococcaceae genus correlated positively with both aromatic amino acids and their metabolic intermediates, as well as with other amino acids like L-citrulline, L-arginine, L-glutamine, L-asparagine, and D-proline. The decreased bacterial genera were positively associated with primary bile acids and negatively with 2-Dehydro-3-deoxy-D-gluconate (Fig. 4c, Supplementary data 4).

FMT accelerates restoration of the disturbed intestinal microbiota

We investigated the efficacy of FMT and its absence on the restoration of disturbed intestinal microbiota caused by florfenicol (Fig. 1; stage 2). After discontinuation of florfenicol intake, the remaining florfenicol-treated fish in the FFNC group were randomized at 1:1 into two groups. One group (FFNC + FMT) received FMT administration, while the other (FFNC + PBS) was allowed to recover naturally using PBS instead of FMT. The remaining fish in the CG-7 group continued the previous treatment, now referred to as the CG-14 group. Eighteen fecal samples from each of the three groups (FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS, and CG-14 groups) were subjected to microbiome analysis. The OTU numbers were similar between the FFNC + FMT and CG-14 groups (Fig. 5a; p > 0.99, Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons). The FFNC + PBS group harbored significantly more OTUs than the FFNC + FMT group but did not show significantly more OTUs compared to the CG-14 group (Fig. 5a; FFNC + FMT vs FFNC + PBS, p = 0.02; CG-14 vs FFNC + PBS, p = 0.86; Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons). Alpha-diversity analysis showed that the FFNC + FMT and CG-14 groups were similar in terms of bacterial richness (Fig. 5b; Chao 1 index, p > 0.99; Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons) and diversity (Fig. 5c; Shannon index, p > 0.99; Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons). Compared with the FFNC + PBS group (Fig. 5b, c; Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons), the FFNC + FMT group had a lower bacterial richness (Chao 1 index, p = 0.019) and diversity (Shannon index, p = 0.0021), while the CG-14 group had slightly lower bacterial richness with a non-significant difference (Chao 1 index, p = 0.12) and significantly lower diversity (Shannon index, p = 0.046).

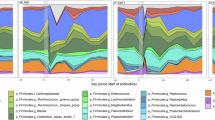

a Comparison of the number of OTUs in the intestinal microbiota among the CG-14, FFNC + PBS, and FFNC + FMT groups. Comparison of the alpha-diversity indices, Chao1 (b) and Shannon’s index (c), of intestinal microbiota among the CG-14, FFNC + PBS, and FFNC + FMT groups. d Comparison of beta-diversity of intestinal microbiota using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA), with statistical significance based on the weighted UniFrac distance and analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA). Lines in the PCoA plot connect each sample point to the center of gravity of its respective sample group. e Average relative abundance of predominant microbiota at the phylum level in the intestines of fish from the CG-14, FFNC + PBS, and FFNC + FMT groups. The FFNC + PBS group was subdivided into FFNC + PBS-S (6 samples) and FFNC + PBS-T (12 samples). Stacked bar plot shows the top six most abundant taxa in the CG-14, FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS, FFNC + PBS-S, and FFNC + PBS-T groups, with each bar representing the average relative abundance of each taxon within the specified group. See Supplementary Data 5 for the source data used in this panel. Results from a LEfSe analysis identifying intestinal bacteria taxa with significant differences in relative abundance between CG-14 and FFNC + FMT (f), FFNC + PBS-S and CG-14 (g), FFNC + PBS-S and FFNC + FMT (h), FFNC + PBS-T and FFNC + FMT (i), CG-14 and FFNC + PBS-T (j), and FFNC + PBS-S and FFNC + PBS-T (k), respectively. Bacterial taxa with an LDA score of 3.5 were selected as biomarker taxa (phylum, genus, and species). Red, blue, grey, and green colors indicate bacterial taxa with increased abundances in the CG-14, FFNC + PBS-T, FFNC + PBS-S, and FFNC + FMT groups, respectively. In (a–k), n = 18 for CG-14, FFNC + PBS, and FFNC + FMT, n = 12 for FFNC + PBS-T, and n = 6 for FFNC + PBS-S. In (a–c), the components of the box plot include a center line representing the median, an upper limit representing the upper quartile, and a lower limit representing the lower quartile. In the box plot, the whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values of the data, and all individual data points are displayed as dots indicating individual sample values. Statistical analyses were performed using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons, with the results shown as exact p-values.

PCoA analysis based on the weighted UniFrac distance (Fig. 5d) showed that the distribution of 18 fecal samples from the FFNC + PBS group was rather dispersed compared to the other two groups. Specifically, six samples clustered together and were labeled as subgroup FFNC + PBS-S, while the other 12 samples in the FFNC + PBS group were more dispersed and labeled subgroup FFNC + PBS-T. All samples from the CG-14, FFNC + FMT, and FFNC + PBS-S groups clustered together and separated from the 12 samples in the FFNC + PBS-T group (CG-14 vs FFNC + FMT, p = 0.62; CG-14 vs FFNC + PBS-T, p < 0.001; CG-14 vs FFNC + PBS-S, p = 0.48; FFNC + FMT vs FFNC + PBS-T, p < 0.001; FFNC + FMT vs FFNC + PBS-S, p = 0.69; FFNC + PBS-T vs FFNC + PBS-S, p = 0.007; AMOVA). Consistent with the PCoA analysis, hierarchical clustering showed that the 12 samples in the FFNC + PBS-T group segregated from all other samples (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Similar intestinal microbiota profiles were found in the CG-14, FFNC + FMT, and FFNC + PBS-S groups (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Fig. 3b, Supplementary data 5). A LEfSe analysis (LDA > 3.5) showed that microbial abundances did not differentiate between the FFNC + FMT and CG-14 groups or between the FFNC + PBS-S and CG-14 groups at any taxonomic level, except for a decline in two potentially pathogenic genera (Vibrio and Shewanella) in the FFNC + FMT group (Fig. 5f) and an increment in the genus Bradyrhizobium in the FFNC + PBS-S group (Fig. 5g). The divergences between the FFNC + FMT and FFNC + PBS-S groups were profound, showing differential abundances in two phyla (Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria) and three genera (Bradyrhizobium, Vibrio, and Cetobacterium) (Fig. 5h). Notably, the bacterial genera that had clearly declined after FFNC intake, namely, Romboutsia, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Stenotrophomonas (Fig. 2g), were similarly abundant among the FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS-S, and CG-14 groups.

By comparing the microbial communities in the FFNC + FMT and CG-14 groups with those in the FFNC + PBS-T group, we observed distinct microbial profiles. Fish in the FFNC + PBS-T group exhibited a higher relative abundance of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria, but a lower relative abundance of Fusobacteria. The genera Alistipes, Alloprevotella, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Bradyrhizobium, Enterococcus, Faecalibacterium, Helicobacter, Lactobacillus, Sphingomonas, and Stenotrophomonas were more abundant in this group. Conversely, the genus Cetobacterium showed a lower abundance (Fig. 5i, j). Notably, only the genus Cetobacterium was found at higher levels in the FFNC + FMT, CG-14, and FFNC + PBS-S groups compared to the FFNC + PBS-T group (Fig. 5i–k).

FMT repairs florfenicol-induced intestinal mucosa injuries

Scanning electron microscope observations showed that fish in the FFNC + PBS group had minor damage in the intestines, characterized by irregularly arranged and inflammatory swollen villi. In contrast, there were no obvious injuries in the intestines of fish from the CG-14 and FFNC + FMT groups (Fig. 6a). The histopathological scores of the foregut and hindgut of the fish in the FFNC + FMT group were significantly lower than those in the FFNC + PBS group (Fig. 6b, c; p < 0.001; two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

a Morphology of the foregut and hindgut observed under a scanning electron microscope. Scale bar = 500 μm. b Representative sections of foregut and hindgut stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Scale bar = 200 μm. c Histological scores for the foregut and hindgut (n = 27/group). Statistical significance was assessed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and the corresponding p-values are indicated. d Comparison of muscle layer thickness in the foregut and hindgut (n = 27/group). Statistical significance was determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons, and the corresponding p-values are indicated. e Relative mRNA expression levels of ZO-1 and occludin in the intestines (n = 3/group). Statistical significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, and the corresponding p-values are indicated. In (c–e), Dots represent individual measurements, and the data are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

In the FFNC + FMT group, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons revealed that muscle thickness in both the foregut and hindgut was significantly greater compared to the CG-14 group (Fig. 6d; foregut, p = 0.007; hindgut, p < 0.001). However, in the FFNC + PBS group, the same comparisons indicated similar muscle thickness in the foregut (Fig. 6d; p > 0.99) but a significantly increased thickness in the hindgut (Fig. 6d; p = 0.0057). The gene expression levels of ZO-1 and occludin in the intestines of fish in the FFNC + PBS group were lower compared to those in the CG-14 group, although these differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 6e; ZO-1, p > 0.99; occludin, p = 0.52). In contrast, the expressions of these genes in the FFNC + FMT group were significantly higher than those in both the CG-14 and FFNC + PBS groups, as determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons (Fig. 6e; ZO-1, CG-14 vs FFNC + FMT, p = 0.025; FFNC + PBS vs FFNC + FMT, p = 0.023; occludin, CG-14 vs FFNC + FMT, p = 0.0022; FFNC + PBS vs FFNC + FMT, p = 0.0063).

Restoration of altered fecal metabolome following FMT administration

Based on OPLS-DA loadings (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c) and univariate statistical analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4d–f), differential metabolic profiles were demonstrated, and DEMs were identified among the FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS and CG-14 groups. Tested samples from the FFNC + FMT or CG-14 group showed more similar clustering patterns of detected metabolites compared to those from the FFNC + PBS group (Supplementary Fig. 4g–i). In total, 95 DEMs were identified between the FFNC + FMT and FFNC + PBS groups (Supplementary Fig. 4g, Supplementary data 6). Additionally, 190 DEMs were identified between the FFNC + FMT and CG-14 groups (Supplementary Fig. 4h, Supplementary data 7), while 86 DEMs were found between the FFNC + PBS and CG-14 groups (Supplementary Fig. 4i, Supplementary data 8). Most of these DEMs were enriched in the KEGG pathways associated with nucleotide, lipid, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism (Supplementary data 9).

Between the FFNC + FMT and FFNC + PBS groups, 29 DEMs, which were involved in 15 statistically enriched KEGG pathways, were identified (Supplementary data 10). Within these, the FMT group exhibited 24 DEMs with higher abundance, listed from high to low as follows: glutathione, cysteine-S-sulfate, N-acetyl-L-glutamate, L-leucine, L-glutamine, cis-9-palmitoleic acid, N,N’-diacetylchitobiose, N-acetylmannosamine, alpha-D-glucose, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, L-pyroglutamic acid, L-histidine, L-tryptophan, L-cystine, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, L-methionine, L-tyrosine, L-phenylalanine, dopamine, N-acetyl-L-aspartic acid, trans-cinnamate, phenyllactic acid, tyramine, and uracil. Additionally, five DEMs were found at lower levels in the FMT group, namely (listed from low to high): linoleic acid, 2,3-dihydroxy-3-methylbutyric acid, histamine, 5-L-glutamyl-L-alanin, and gamma-L-glutamyl-L-valine.

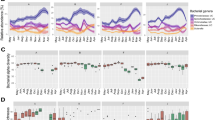

The fish in the FFNC + PBS-T group diverged from the CG-14 group, while those in the FFNC + FMT group clustered closely with the CG-14 group. Consequently, we further explored the DEMs among the FFNC + PBS-T, FFNC + FMT, and CG-14 groups. Notably, 80 DEMs were identified between the fish in the FFNC + FMT group and those in the FFNC + PBS-T group (Supplementary Fig. 5a–d, Supplementary data 11). Metabolite set enrichment analysis revealed 13 statistically significant KEGG pathways enriched with 28 DEMs. These pathways are associated with the metabolism of amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. 5e, Supplementary Data 12).

a The heatmap displays differentially abundant metabolites from significantly enriched KEGG pathways between the FFNC + PBS-T and FFNC + FMT groups. These metabolites are identified in all samples from the CG-14, FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS-T, and FFNC + PBS-S groups. b The heatmap of Spearman’s rank correlation shows associations of metabolites and bacterial genera, both of which had different abundances between the FFNC + PBS-T and FFNC + FMT groups. Pink squares indicate positive associations, blue squares indicate negative associations, and statistical significance is denoted on the squares (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001). See Supplementary Data 13 for the source data used in this panel. In (a) and (b), n = 18 for CG-14 and FFNC + FMT, n = 12 for FFNC + PBS-T, and n = 6 for FFNC + PBS-S.

In terms of amino acid metabolism, the FFNC + FMT group exhibited higher levels of aromatic amino acids, including L-histidine, L-tryptophan, L-phenylalanine, and L-tyrosine, as well as higher concentrations of their metabolic intermediates, namely phenyllactic acid and dopamine, compared to the FFNC + PBS-T group (Fig. 7a). The concentrations of these metabolites in the CG-14 group were also higher than those in the FFNC + PBS-T group, except for phenyllactic acid, which had similar levels (Fig. 7a). Additionally, the FFNC + FMT group had the highest level of metabolites, which were associated with glutathione synthesis, including L-glutamine, L-cystine, cysteine-S-sulfate, and L-pyroglutamic acid, among the FFNC + PBS-T, FFNC + FMT, and CG-14 groups (Fig. 7a, Supplementary data 11). In terms of carbohydrate metabolism, compared with the FFNC + PBS-T group, the FFNC + FMT group had higher levels of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, N-acetylmannosamine, N, N’-diacetylchitobiose, and alpha-D-glucose, all of which were involved in amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism. The concentrations of these four carbohydrate metabolites in the CG-14 group were also higher than those in the FFNC + PBS-T group (Fig. 7a). Regarding lipid metabolism, among the FFNC + PBS-T, FFNC + FMT, and CG-14 groups, the FFNC + PBS-T group exhibited the highest levels of metabolites involved in the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. These included arachidic acid, erucic acid, linoleic acid, and arachidonic acid (peroxide-free) (Fig. 7a, Supplementary data 11).

Spearman correlation analysis identified significant associations between metabolite concentrations and bacterial genera with significantly different abundances between the FFNC + PBS-T and FFNC + FMT groups (Fig. 7b, Supplementary data 13). Specifically, the bacterial genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Bacteroides were negatively associated with aromatic amino acids (L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine, L-histidine) and their metabolic intermediates (phenyllactic acid and dopamine), as well as key metabolites associated with glutathione synthesis (glutathione, L-pyroglutamic acid, and L-glutamine). No significant associations were found between these bacterial genera and lipid or carbohydrate metabolites. Notably, only the bacterial genus Cetobacterium showed a positive association with these metabolites.

Discussion

Antibiotics can perturb the microbiota composition and cause gut dysbiosis, but their effects can be more complex32,33. Many studies have demonstrated that therapeutic doses of antibiotics can directly disrupt the physical and secretory barriers of the gut34,35, and can also indirectly destroy these barriers by disturbing the intestinal microbiota36. This disruption renders the intestinal epithelium more susceptible to damage37. Florfenicol is widely used in aquaculture to treat infections in fish caused by bacterial pathogens, such as Flavobacterium psychrophilium, F. columnare, Aeromonas salmonicida, Edwardsiella ictaluri, and Streptococcus iniae, typically at a dosage of 10 mg per kg of fish body weight per day38. For this study, we chose a dosage of 9 mg per kg of fish body weight per day, closely aligning with practical strategies and existing treatment protocols, to disturb the intestinal microbiota in koi carp. Furthermore, we applied FMT to restore the florfenicol-perturbed intestinal microbiota in the fish.

In our study, the administration of florfenicol in koi carp profoundly affected the intestinal microbiome, leading to a notable decrease in microbial diversity and richness. This alteration was characterized by a reduction in benign bacterial genera, such as Romboutsia, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium, along with a decrease in potentially pathogenic genera, including Acinetobacter, Aeromonas, and Vibrio. These shifts in microbiota composition could probably disrupt gut homeostasis, impair immune responses, and increase susceptibility to infections.

The efficacy of FMT in countering the adverse effects of florfenicol was evident within a short period (7 days), in contrast to natural recovery, which did not achieve similar results. FMT facilitated the recovery of microbial species richness and diversity, reinstating the populations of beneficial bacteria decreased by florfenicol, such as Romboutsia, Bacteroides, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Faecalibacterium. The restoration of these beneficial microbes is crucial for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, synthesizing essential nutrients, and modulating the immune system39,40. The recovery of these bacterial taxa post-FMT underscores the potential of microbial therapies in aquaculture, especially as a countermeasure to antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. Further investigations into long-term impacts of FMT on fish health and resistance to pathogens are warranted to establish its efficacy and safety.

The activity of the microbiome and its metabolic products directly influence various aspects of host physiology41. Bioactive microbial metabolites found in feces primarily originate from compounds produced by gut microbes or from the transformation of host substances by these microbes. These metabolites can be considered as an intermediate phenotype that mediates host–microbiome interactions42. Analyzing the fecal metabolome provides a functional readout of the activity of intestinal microbiota43. In this study, high throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene was employed to analyze changes in the intestinal microbiota of fish treated with florfenicol or FMT. Additionally, fecal metabolome analysis was performed to reflect metabolic processes of the gut microbiome.

The classification of fish from the FFNC + PBS group with uncovered intestinal microbiota as a phenotypic subtype (FFNC + PBS-T group) prompts an interest in comparing their metabolic profiles with those in the FFNC + FMT group. This comparison is anticipated to further shed light on functional metabolites that may be linked to FMT efficacy. Interestingly, the majority of the significantly enriched KEGG pathways and associated DEMs between the FFNC + FMT and FFNC + PBS-T groups (Fig. 7a; Supplementary data 12) align closely with those found in the comparison between the FFNC + FMT and the FFNC + PBS groups (Supplementary data 10). These findings highlight the importance of FMT in restoring not just the microbial diversity but also the functional metabolic landscape that supports gut health.

The analysis of the fecal metabolome provided valuable insights into the metabolic alterations induced by florfenicol and the potential for FMT to reverse these changes. Florfenicol treatment resulted in significant perturbations across various metabolic pathways, with DEMs involved in nucleotide, amino acid, carbohydrate, and lipid metabolism. Notably, the reduction in primary bile acids such as taurocholate and glycocholic acid highlighted an impairment in lipid digestion and absorption, which could lead to altered energy homeostasis and metabolic health in fish44. The decreased levels of aromatic amino acids (e.g., L-tryptophan, L-tyrosine) and their intermediates (e.g., indole, dopamine) in the FFNC group indicated disruptions in neurotransmitter synthesis and immune function45. The reduction in arginine family amino acids like L-citrulline and L-arginine further suggested that florfenicol might impair nitrogen balance and protein metabolism, which are critical for growth and maintenance in aquatic organisms46.

FMT was shown to restore the fecal metabolome closer to the baseline levels observed in the control group (CG-14). The clustering of metabolite profiles and significant differences in DEMs between the FFNC + FMT and FFNC + PBS groups underscored the therapeutic potential of FMT in mitigating the metabolic disturbances induced by antibiotics. The increased levels of aromatic amino acids and their metabolites (e.g., L-phenylalanine, L-tyrosine, dopamine) in the FFNC + FMT group suggested a restoration of pathways associated with neurotransmitter synthesis and immune modulation45. The elevation of metabolites involved in glutathione synthesis (e.g., L-glutamine, cysteine-S-sulfate) in the FMT group indicated enhanced antioxidant capacity, which is crucial for counteracting oxidative stress and maintaining cellular homeostasis47,48. Notably, the increased abundance of L-histidine post-FMT contributed to the restoration of acid-base balance and the recovery of disturbed intestinal microbiota49.

The observed increases in carbohydrate metabolites such as N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and alpha-D-glucose in the FFNC + FMT group highlighted a recovery in energy metabolism and the reestablishment of a functional gut microbiota capable of fermenting complex polysaccharides50. The higher levels of these metabolites compared to the FFNC + PBS group suggested that FMT not only restores the microbial community but also reactivates metabolic pathways crucial for the host’s energy balance. In terms of lipid metabolism, the reduction in metabolites associated with the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in the FFNC + FMT group indicated a normalization of lipid profiles. This reduction likely reflects the rebalancing of fatty acid metabolism, which is essential for maintaining cell membrane integrity and signaling processes51.

Gut microbiota dysbiosis may persist for a long time after antibiotic treatment, and certain native bacteria may not recover52. During natural recovery, the high levels of beneficial bacterial genera and potential pathogens in the fish indicate they are recovering from a dysbiotic state. This instability was validated by significant differences in gut microbiota between the FFNC + PBS group and normal fish (CG-14 group), indicating that antibiotic selection pressure influenced microbial diversity during recovery. Beneficial bacteria may contribute to the natural recovery process. However, the high abundance of beneficial bacterial genera and low amino acid levels in the FFNC + PBS-T group may suggest bacterial overgrowth, leading to an imbalance between the utilization and synthesis of amino acids.

There is a strong link among gut microbiota, their metabolites, and various physiological aspects in the gut of hosts53. Florfenicol caused notable injuries to the intestinal mucosa, marked by histomorphological changes and lower levels of tight junction proteins like ZO-1 and occludin. Scanning electron microscopy showed significant mucosal damage, such as fractured surfaces and irregular pits in the foregut and hindgut. Histopathological analysis confirmed structural damage, indicated by higher tissue damage scores and reduced muscle thickness. The decreased ZO-1 expression points to a weakened intestinal barrier, increasing the risk of infections and gastrointestinal issues31. Conversely, FMT exhibited significant therapeutic benefits, as evidenced by the intact mucosal structures and normal villi arrangement in the treated fish. The significantly lower histopathological scores indicated reduced tissue damage and inflammation, while muscle thickness in both the foregut and hindgut showed notable recovery, suggesting enhanced muscle regeneration. Gene expression analysis revealed that FMT elevated ZO-1 and occludin levels, restoring the intestinal barrier’s integrity compromised by florfenicol. These results underscore the adverse histomorphological effects of florfenicol on gut health and demonstrate FMT’s effectiveness in repairing mucosal damage and enhancing gut integrity.

The findings from Spearman correlation analyses provide deeper insights into the relationships between gut microbiota and the fecal metabolome in fish, elucidating how shifts in microbiota composition, influenced by florfenicol and subsequent recovery processes via FMT, can significantly affect metabolic profiles. In the FFNC and CG-7 groups, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus were positively correlated with aromatic and other amino acids (L-citrulline, L-arginine, L-glutamine, L-asparagine), and primary bile acids, but negatively with 2-Dehydro-3-deoxy-D-gluconate. In the FFNC + PBS-T and FFNC + FMT groups, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Bacteroides showed negative associations with aromatic amino acids and glutathione-related metabolites.

The divergent correlations between bacterial genera and metabolites across the different groups underscore the pivotal role of microbial communities in regulating metabolism, particularly in the context of aromatic amino acid, bile acid, glutathione metabolism pathways. Genera such as Romboutsia, Bacteroides, and Streptococcus play crucial roles in metabolizing aromatic amino acids to produce phenolic and indolic compounds54,55,56,57. These microbial metabolites play important roles in regulating biological processes such as intestinal epithelial cell homeostasis, immune cell responses, and neuronal excitability58,59. Bacteroides species rely on glutamate and glutamine to produce ammonia, which serves as the sole nitrogen source essential for their growth60. Faecalibacterium primarily ferments complex carbohydrates and amino acids to produce short-chain fatty acids, especially butyrate and is involved in bile acid metabolism61. Lactobacillus ferments sugars and amino acids to produce lactic acid, bioactive peptides, and vitamins, and it also participates in bile acid transformation62. Previous studies have reported that a reduction in Faecalibacterium and Lactobacillus may impair lipid metabolism and is associated with intestinal inflammation63,64,65.

Research on Cetobacterium, a genus established in 2003, has primarily focused on its role in the gut microbiota of freshwater fish, where it metabolizes proteins and amino acids and produces short-chain fatty acids like acetate66. Cetobacterium is notably abundant in the intestines of several freshwater fish species, including Oreochromis niloticus67, Arapaima gigas68, Cyprinus carpio69, Lepomis macrochirus, Micropterus salmoides, and Ictalurus punctatus70. In this study, Cetobacterium was found to be more prevalent in stable gut microbiomes compared to unstable ones. Furthermore, a unique positive correlation was observed between Cetobacterium and aromatic amino acids, as well as glutathione-related metabolites, in the FFNC + FMT group. This indicates that, despite its variable abundance in distinct microbial environments, Cetobacterium plays an essential and integral role in enhancing key metabolic pathways for gut health, making it a potential biomarker for assessing the health status of freshwater fish.

The observed differences in correlations can be attributed to the distinct microbial environments and recovery states across the experimental groups. The FFNC group, which underwent florfenicol treatment, likely experienced significant alterations in its bacterial community structure, leading to changes in metabolic activities related to amino acids and bile acids. In contrast, the CG-7 group, serving as a PBS control, maintained a relatively stable microbial composition, thus providing a baseline for comparison. The positive correlations observed in the FFNC group may reflect a compensatory metabolic response to florfenicol-induced perturbations, where certain bacteria enhance amino acid metabolism to maintain homeostasis.

In the FFNC + PBS-T group, which represents a state of microbiota dysbiosis following natural recovery over seven days, the negative correlations with aromatic amino acids and glutathione-related metabolites indicate disrupted metabolic pathways. The dysbiotic microbiota may exhibit reduced functional capacity to synthesize or degrade these key metabolites, leading to their altered abundances. This highlights the ongoing stress and imbalance within the microbial community, which continues to affect host metabolism despite the cessation of antibiotic treatment. On the other hand, the FFNC + FMT group, which underwent FMT, showed negative correlations with the same metabolites, reflecting a restoration of normal microbial function and structure. FMT likely facilitated the re-establishment of a balanced microbiota, capable of efficiently metabolizing aromatic amino acids and supporting glutathione synthesis. This restored functionality underscores the role of FMT in mitigating the adverse effects of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis and enhancing the metabolic resilience of the host microbiome.

Florfenicol treatment disrupts the microbial ecosystem, leading to altered metabolic interactions that can impact amino acid and bile acid metabolism. In contrast, the restoration of microbial balance through FMT supports normal metabolic function, highlighting the potential of microbiota-based therapies in correcting dysbiotic states and enhancing metabolic health. Further research is warranted to explore the specific mechanisms through which these bacterial taxa influence host metabolism and to develop targeted interventions to modulate these interactions for improved health outcomes.

In summary, florfenicol administration in fish led to significant disruptions in the intestinal microbiota, reducing beneficial genera such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Romboutsia, Faecalibacterium, and Streptococcus, and causing mucosal injuries. Key metabolites like aromatic amino acids and glutathione-related metabolites were also diminished. FMT effectively restored these microbial populations, repaired intestinal damage, and normalized levels of critical metabolites. This highlights the therapeutic potential of FMT in counteracting antibiotic-induced dysbiosis and underscores its importance for maintaining intestinal health in farmed fish. The recovered microbial populations and normalized critical metabolites lay the foundation for developing probiotic cocktails to achieve personalized therapeutic strategies in fish.

Methods

Fish

Healthy koi carp, C. carpio var. koi (weight: 200 ± 5 g; length: 29 ± 2 cm), were sourced from Tianjin Longjin Aquaculture Co. Ltd, Tianjin, China. Prior to the experiments, none of the fish had ingested any antibiotics, probiotics, or prebiotics. The fish were transported to Tianjin Agricultural University and acclimatized for three weeks in freshwater at 23 °C, pH 7.5, with aeration to maintain appropriate dissolved oxygen levels. During acclimatization, the fish were fed twice daily with a formula feed constituting 3% of their body weight. The commercial feed from Chenhui Feed Co., Ltd., containing 30% crude protein, 3% crude fat, 12% crude fiber, 1.5% lysine, 12% crude ash, 1.5% total phosphorus, and 2% calcium, served as the basal feed. All procedures involving the use and care of the fish adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Animal Research (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NIH Publication No.8023, revised 1978) and were approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee at Tianjin Agricultural University. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Donor fecal microbiota and experimental feeds

Healthy koi carp of similar size to the recipient fish were selected for the preparation of donor fecal microbiota. Four hours after the final feeding, the fish were euthanized by immersion in ice-cold water. Their surfaces were first wiped clean with 70% ethanol. Then, their abdomens were opened along the ventral midline and the whole intestines were aseptically removed from the abdominal cavity. The external surface of the intestine was washed with sterile PBS, and residual water was dried using filter paper. The intestine was transversely cut at the middle part, and intestinal contents were squeezed out and collected into a 50 ml tube. The two intestine parts were then split longitudinally, and the residual intestinal content was slightly scraped and collected into the same tube. Intestinal contents from each fish were diluted in one-third volume of sterile PBS, homogenized using a magnetic stirrer, and filtered three times to remove undigested particulate matter. The sample was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min and the precipitate was resuspended with equal volume of sterile PBS. Glycerol was then added to the resulting suspension to achieve a final concentration of 10%. All samples from 30 koi carp were pooled together and stored at −80 °C until use.

To prepare experimental feeds, the frozen fecal microbiota suspension was thawed at 37 °C in a water bath, as this condition ensured good viability of the microbiota71. The concentrations of fecal microbiota suspension before freezing and after thawing were roughly estimated respectively as 2.11 × 107 CFU ml−1 and 1.49 × 107 CFU ml−1 using the conventional plate count method with Luria–Bertani agar. After thawing, the suspension was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 min, and the precipitate was re-suspended in fresh sterile PBS. The donor microbiota suspension was evenly sprayed on the basal feed at a ratio of 66.7 ml kg−1, allotting 200 μL of bacterial suspension for each meal of each fish. Similarly, the same ratio of sterile PBS was sprayed on the basal feed for a control feed. Florfenicol was supplemented in the basal feed at a ratio of 300 mg/kg and used for florfenicol administration in the fish, with its dosage calculated as 9 mg/kg fish weight per day, according to the feed strategy.

Experimental design and sample collection

There were two stages to the experimentation, and the detailed experimental process is shown in Fig. 1. In the first stage, the experimental fish were randomly and evenly distributed into two groups. One group (FFNC) fed with florfenicol-supplemented feed and another group (CG-7) fed with the basal feed for seven days. To determine if intestinal dysbacteriosis was induced by florfenicol, 11 koi carp from each of these two groups were sacrificed seven days after florfenicol intake, and a fecal sample from each fish was collected.

After the first stage, the second phase began with the discontinuation of florfenicol treatment (Fig. 1). The remaining florfenicol-treated fish were divided equally into two groups. One group was fed the basal feed supplemented with donor fecal microbiota at each meal (FFNC + FMT) for seven consecutive days, while the other received the basal feed supplemented with sterile PBS (FFNC + PBS). Serving as the control, the remaining fish in the CG-7 group continued on the basal feed and were re-designated as the CG-14 group. Each group was maintained in three tank replicates. After seven days, six fish from each tank, across all groups, were selected for feces sampling using the same procedures as those used for collecting the donor microbiota. Eighteen fecal samples from each group (FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS, CG-14) were then frozen at −80 °C for subsequent microbiome and metabolome analyses.

For qPCR analyses, intestine tissues were sampled from the fish. Specifically, the entire intestine was removed from the abdominal cavity, and the lumen was rinsed with sterile PBS to eliminate the food residues and feces. Any residual blood and fat on the intestine surface were gently removed. The intestine was then divided into six equal segments, and approximately 20 milligrams of tissues were sampled from each segment for each fish. All sampled tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction. Eighteen fish from each of three groups (FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS, CG-14) were included. The intestine tissues from six corresponding fish in each group were pooled together as one sample.

For histopathological and morphological studies, three fish were randomly selected from the triplicate tanks of each group. The foregut and hindgut were sampled based on their anatomical and functional characteristics28, then fixed in Bouin’s fixative for histological sectioning, or in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution at 4 °C for scanning electron microscopy.

Microbiome analysis

Microbiome analysis was conducted using 16S rRNA gene high throughput sequencing. Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from all the fecal samples using a QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR using a pair of primers (341 F: 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′ and 806R: 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′), each containing a barcode sequence for unique identification of each DNA sample72. Amplicons were extracted from 2% agarose gels and purified using a Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). DNA libraries were constructed a TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). Library quality was assessed using a Qubit@ 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific) and Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq platform by Tianjin Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. (China), generating 250 bp paired-end reads. Paired-end reads were merged using FLASH (V1.2.7)73, filtered by QIIME E (V1.9.1)74, and checked for chimeras using the UCHIME algorithm against the Silva database (https://www.arb-silva.de/). Effective reads were then clustered into OTUs at 97% similarity using UPARSE software, and each representative sequence was taxonomically annotated using the Silva database through the Mothur algorithm.

To study the phylogenetic relationships of different OTUs and the variations in dominant species across samples (groups), multiple sequence alignment was conducted using MUSCLE software (V3.8.31). OTUs abundance was normalized to the sample with the fewest sequences. From these normalized data, alpha-diversity indices (Chao1 and Shannon) and beta-diversity indices (both weighted and unweighted UniFrac) were calculated using QIIME (V1.7.0). The weighted UniFrac distance matrices were used to assess differences in microbiota composition. The results were visualized through Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) and Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic mean (UPGMA) Clustering. Differences in phylogenetic composition among groups were analyzed using the weighted UniFrac distances. Additionally, the characteristics of intestinal microbiota were explored through LEfSe for biomarker discovery, with LDA scores estimating the impact of each differentially abundant feature.

Untargeted metabolomic analysis

Metabolites were extracted from lyophilized and homogenized fecal samples using a methanol-based method. First, 100 mg of the fecal samples were thawed in 200 μL of water, disrupted using a FastPrep®-24 Instrument (MP Biomedicals), and then mixed with 400 μL of cold methanol/acetonitrile (1:1, v/v) to precipitate proteins. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was dried in a vacuum centrifuge and subsequently re-dissolved in 100 μL of acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v) for analysis.

Untargeted fecal metabolomic analysis was performed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). For this analysis, an Agilent 1290 Infinity ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with a TripleTOF 6600 quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was utilized. For hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) separation, samples were analyzed on an ACQUITY UPLC BEH column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 µm; Waters, UK) in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes (ESI, RP+ and RP−). The column compartment was maintained at 25 °C. The flow rate was set at 0.3 mL per min, using a mobile phase of solvent A (water + 25 mmol ammonium acetate + 25 mmol ammonium hydroxide) and solvent B (acetonitrile). The elution gradient was established as follows: 85% B for 1 min; 85–65% over 11 min, 65%-40% in 0.1 min and held for 4 min; 40–85% in 0.1 min, followed by a 5 min re-equilibration period. The ESI source conditions were set with Ion Source Gas1 at 60, Ion Source Gas2 at 60, curtain gas at 30, source temperature at 600 °C, and IonSpray Voltage Floating (ISVF) at ± 5500 V. In MS only acquisition, the range was set from m/z 60–1000 Da, with an accumulation time for TOF MS scanning at 0.20 s per spectra. In auto MS/MS acquisition, the range was from m/z 25-1000 Da, with an accumulation time for product ion scanning set at 0.05 s per spectra. Product ion scans were acquired using information-dependent acquisition in high sensitivity mode, with collision energy set at 35 V ( ± 15 eV), declustering potential at ± 60 V, excluding isotopes within 4 Da, and monitoring up to 10 candidate ions per cycle.

Raw MS data were converted to MzXML format using the MSConvert tool from ProteoWizard and then processed with the XCMS R-package for peak detection and matching. Metabolites were identified by comparison with the METLIN database and further analyzed against the KEGG database for metabolic pathway insights. Multivariate data analysis was performed using SIMCA-P software (V14.1, Umetrics, Umea, Sweden), including Pareto-scaled principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA). The variable importance in the projection (VIP) values from the OPLS-DA model indicated the contribution of each variable to the classification. Metabolites wit scores greater than 1 were subjected to Student’s t-tests at the univariate level to assess significance, with p values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Total RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated from the intestinal tissue samples using the RNAiso Plus kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Genomic DNA was removed by performing two digestions with amplification-grade DNAse 1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quality of RNA was assessed using a Nano Drop and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Real-time PCR

The mRNA levels of two tight junction proteins, ZO-1 and occludin, in fish intestine tissues were determined by real-time PCR (qPCR). Primers were designed based on gene sequences available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The occludin primers were: forward 5′-TCCACAAACCGTCCACCTC-3′ and reverse 5′-TCGTCAAAATCATTGGCAGTC-3′; The ZO-1 primers were forward 5′-GTCACCCTCAGATGCGAAAT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCTGTTGTGGTTGAGTGTAGGC-3′. Beta-actin (β-actin) was used as an internal control, with primers: forward 5′-TCTGCTATGTGGCTCTTGACTT-3′ and reverse 5′-TACCGCAAGACTCCATACCC-3′. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA samples using a Bio-Rad iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Hercules, CA, USA). qPCR was performed on a StepOne Plus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with conditions set at an initial denaturation of 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. All reactions were performed in triplicate. Relative gene expression was statistically analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle method (2−ΔΔCT) with β-actin as the reference. A melting curve analysis was conducted at the end of the assay to ensure amplification specificity.

Histological analysis and scanning electron microscopy observations

Foregut and hindgut intestinal tissues were fixed in Bouin’s fixative for 24 h, then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 μm slices using a Thermo microtome (Waltham, MA, USA). The sections were then mounted on slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and observed under a Leica light microscope (Wetzlar, Germany). Intestinal histological changes were graded on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates no lesion; 1, a focal lesion; 2, multifocal mild lesions; 3, multifocal moderate lesions; and 4, diffuse moderate or severe damage. For scoring, three fields from each of three slides per fish were randomly selected. The foregut and hindgut tissues fixed in glutaraldehyde were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, subjected to critical point drying, coated with a thin layer of gold, and examined using a TM1000 Hitachi scanning electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Statistics and reproducibility

To establish a consistent fish model of antibiotic-induced intestinal microbiota dysbiosis, the fish in the FFNC and CG-7 groups were maintained in a continuous water system, respectively, during the first stage of the experiment. Eleven samples (fish) from each group were collected for analysis of the intestinal microbiome and fecal metabolome. In the second stage, each of the groups, FFNC + FMT, FFNC + PBS, and CG-14, included three tank replicates, and 18 samples (fish) were collected from each group. This study also differentiated the PBS-treated group (FFNC + PBS) into subsets: fish with recovered gut microbiota (FFNC + PBS-S) and those unrecovered (FFNC + PBS-T) for statistical analysis to further explore potential functional bacterial taxa and metabolites.

The GraphPad Prism 7.0 package (San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform significance tests on continuous variables, including bacterial α-diversity and histological scores. Datasets with unique values were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and those containing tied values (two or more identical values) were tested using the D’Agostino-Pearson test, respectively. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviations (SD) unless otherwise indicated. For data comparison, the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for normally distributed data between two groups, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post-test for multiple groups. For nonparametric datasets, the two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons were used for two groups and multiple groups, respectively. Analyses of enriched KEGG pathways in the fecal metabolites, intestinal microbiota, and Spearman correlation analyses of fecal metabolites and intestinal microbiota, were performed using R version 3.4.2. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 levels. Sample sizes and details about other software and statistical methods are described in the Methods section and figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw 16S rRNA sequencing data supporting the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA656713. The source data for the relevant figures are available in Supplementary Data Files 14 and 15. The authors declare that all additional data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

Details of publicly available software used in the study are provided in the “Methods” section. No custom code or mathematical algorithms that are deemed central to the conclusions were used.

References

Looft, T. et al. In-feed antibiotic effects on the swine intestinal microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 1691–1696 (2012).

Sekirov, I. et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 76, 4726–4736 (2008).

Theriot, C. M. et al. Antibiotic-induced shifts in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome increase susceptibility to Clostridium difficile infection. Nat. Commun. 5, 3114 (2014).

Utzschneider, K. M. et al. Mechanisms linking the gut microbiome and glucose metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 1445–1454 (2016).

Cabello, F. C. Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: a growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 1137–1144 (2006).

Irianto, A. & Austin, B. Probiotics in aquaculture. J. Fish Dis. 25, 633–642 (2002).

Balcázar, J. L. et al. The role of probiotics in aquaculture. Vet. Microbiol. 114, 173–186 (2006).

Brandt, L. J. & Aroniadis, O. C. An overview of fecal microbiota transplantation: techniques, indications, and outcomes. Gastrointest. Endosc. 78, 240–249 (2013).

Quraishi, M. N. et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and refractory Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 46, 479–493 (2017).

Kim, K. O. & Gluck, M. Fecal microbiota transplantation: an update on clinical practice. Clin. Endosc. 52, 137–143 (2019).

Holvoet, T. et al. Assessment of faecal microbial transfer in irritable bowel syndrome with severe bloating. Gut 66, 980–982 (2016).

Bajaj, J. S. et al. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy. A randomized clinical trial. Hepatology 66, 1727–1738 (2017).

Kootte, R. S. et al. Improvement of insulin sensitivity after lean donor feces in metabolic syndrome is driven by baseline intestinal microbiota composition. Cell Metab. 26, 611–619 (2017).

Vrieze, A. et al. Transfer of intestinal microbiota from lean donors increases insulin sensitivity in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Gastroenterology 143, 913–916 (2012).

Hanssen, N. M. J., de Vos, W. M. & Nieuwdorp, M. Fecal microbiota transplantation in human metabolic diseases: From a murky past to a bright future? Cell Metab. 33, 1098–1110 (2021).

Wortelboer, K., Nieuwdorp, M. & Herrema, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation beyond Clostridioides difficile infections. EBioMedicine 44, 716–729 (2019).

Burrello, C. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation controls murine chronic intestinal inflammation by modulating immune cell functions and gut microbiota composition. Cells 8, 517 (2019).

Hu, X. F. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates myocardial damage in myocarditis by restoring the microbiota composition. Pharmacol. Res. 139, 412–421 (2019).

Brunse, A. et al. Enteral broad-spectrum antibiotics antagonize the effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in preterm pigs. Gut Microbes 13, 1–16 (2021).

Cheng, S. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation beneficially regulates intestinal mucosal autophagy and alleviates gut barrier injury. mSystems 9, e00137–18 (2018).

Huang, Z. et al. Microecological Koch’s postulates reveal that intestinal microbiota dysbiosis contributes to shrimp white feces syndrome. Microbiome 8, 32 (2020).

Wortelboer, K. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation as tool to study the interrelation between microbiota composition and miRNA expression. Microbiol. Res. 257, 126972 (2022).

Smith, P. et al. Regulation of life span by the gut microbiota in the short-lived African turquoise killifish. Elife 6, e27014 (2017).

Rao, J. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation ameliorates gut microbiota imbalance and intestinal barrier damage in rats with stress-induced depressive-like behavior. Eur. J. Neurosci. 53, 3598–3611 (2021).

Le Bastard, Q. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation reverses antibiotic and chemotherapy-induced gut dysbiosis in mice. Sci. Rep. 8, 6219 (2018).

Barreto, F. M. et al. Evaluation of the leaching of florfenicol from coated medicated fish feed into water. Environ. Pollut 242, 1245–1252 (2018).

He, S. et al. Effects of the antibiotic growth promoters flavomycin and florfenicol on the autochthonous intestinal microbiota of hybrid tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus ♀×O. aureus ♂). Arch. Microbiol. 192, 985–994 (2010).

Sun, J. et al. Histochemical distribution of four types of enzymes and mucous cells in the intestine of koi carp (Cyprinus carpio var. koi). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 45, 1367–1376 (2019).

Butt, R. L. & Volkoff, H. Gut microbiota and energy homeostasis in fish. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 9 (2019).

Pękala-Safińska, A. Contemporary threats of bacterial infections in freshwater fish. J. Vet. Res. 62, 261–267 (2018).

Zihni, C., Mills, C., Matter, K. & Balda, M. S. Tight junctions: from simple barriers to multifunctional molecular gates. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 564–580 (2016).

Morgun, A. et al. Uncovering effects of antibiotics on the host and microbiota using transkingdom gene networks. Gut 64, 1732–1743 (2015).

Lange, K., Buerger, M., Stallmach, A. & Bruns, T. Effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota. Digest. Dis. 34, 260–268 (2016).

Shi, Y. et al. Structural and functional alterations in the microbial community and immunological consequences in a mouse model of antibiotic-induced dysbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1948 (2018).

Tulstrup, M. V. et al. Antibiotic treatment affects intestinal permeability and gut microbial composition in Wistar rats dependent on antibiotic class. PLoS One 10, e0144854 (2015).

Duan, H. et al. Antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis and barrier disruption and the potential protective strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 1427–1452 (2022).

Ramirez, J. et al. Antibiotics as major disruptors of gut microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10, 572912 (2020).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved aquaculture drugs. FDA https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/aquaculture/approved-aquaculture-drugs (2024).

Nayak, S. K. Role of gastrointestinal microbiota in fish. Aquac. Res. 41, 1553–1573 (2010).

Hills, R. D. et al. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients 11, 1613 (2019).

Lee, W. J. & Hase, K. Gut microbiota-generated metabolites in animal health and disease. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 416–424 (2014).

Marcobal, A. et al. A metabolomic view of how the human gut microbiota impacts the host metabolome using humanized and gnotobiotic mice. ISME J 7, 1933–1943 (2013).

Zierer, J. et al. The fecal metabolome as a functional readout of the gut microbiome. Nat. Genet. 50, 790–795 (2018).

Romano, N. et al. Bile acid metabolism in fish: disturbances caused by fishmeal alternatives and some mitigating effects from dietary bile inclusions. Rev. Aquacult 12, 1792–1817 (2020).

Beaumont, M. & Blachier, F. Amino acids in intestinal physiology and health. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1265, 1–20 (2020).

Wu, G. et al. Arginine metabolism and nutrition in growth, health and disease. Amino Acids 37, 153–168 (2009).

Cao, Y., Feng, Z., Hoos, A. & Klimberg, V. S. Glutamine enhances gut glutathione production. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 22, 224–227 (1998).

Belmonte, L. et al. Effects of glutamine supplementation on gut barrier, glutathione content and acute phase response in malnourished rats during inflammatory shock. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 2833–2840 (2007).

Rojas, D. B. et al. Administration of histidine to female rats induces changes in oxidative status in cortex and hippocampus of the offspring. Neurochem. Res. 37, 1031–1036 (2012).

Ma, J. L. et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the glycolipid metabolism response mechanism in the liver of genetically improved farmed Tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) under hypoxia stress. BMC Genomics 22, 105 (2021).

Huyben, D., Roehe, B. K., Bekaert, M., Ruyter, B. & Glencross, B. Dietary lipid: protein ratio and n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids alters the gut microbiome of Atlantic salmon under hypoxic and normoxic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 11, 589898 (2020).

d’Humières, C. et al. Perturbation and resilience of the gut microbiome up to 3 months after β-lactams exposure in healthy volunteers suggest an important role of microbial β-lactamases. Microbiome 12, 50 (2024).

Rooks, M. G. & Garrett, W. S. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 341 (2016).

Saito, Y., Sato, T., Nomoto, K. & Tsuji, H. Identification of phenol- and p-cresol producing intestinal bacteria by using media supplemented with tyrosine and its metabolites. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy125 (2018).

Russell, W. R. et al. Major phenylpropanoid-derived metabolites in the human gut can arise from microbial fermentation of protein. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 57, 523–535 (2013).

Pugin, B. et al. A wide diversity of bacteria from the human gut produces and degrades biogenic amines. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 28, 1353881 (2017).

Gerritsen, J. et al. Genomic and functional analysis of Romboutsia ilealis CRIBT reveals adaptation to the small intestine. Peer J. 5, e3698 (2017).

Nyangale, E. P., Mottram, D. S. & Gibson, G. R. Gut microbial activity, implications for health and disease: the potential role of metabolite analysis. J. Proteome Res. 11, 5573–5585 (2012).

Smith, E. A. & Macfarlane, G. T. Enumeration of human colonic bacteria producing phenolic and indolic compounds: effects of pH, carbohydrate availability and retention time on dissimilatory aromatic amino acid metabolism. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 81, 288–302 (1996).

Fischbach, M. A. & Sonnenburg, J. L. Eating for two: how metabolism establishes interspecies interactions in the gut. Cell Host Microbe 10, 336–347 (2011).

Fellows, R. et al. Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat. Commun. 9, 105 (2018).

Raveschot, C. et al. Production of bioactive peptides by Lactobacillus species: from gene to application. Front. Microbiol. 9, 2354 (2018).

von Schillde, M. A. et al. Lactocepin secreted by Lactobacillus exerts anti-inflammatory effects by selectively degrading proinflammatory chemokines. Cell Host Microbe 11, 387–396 (2012).

Yu, J., Raka, F. & Adeli, K. The role of the gut microbiota in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. J. Clin. Med. 8, 2227 (2019).

Lavelle, A. & Sokol, H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastro. Hepat 17, 223–237 (2020).

Finegold, S. M. et al. Cetobacterium somerae sp. nov. from human feces and emended description of the genus Cetobacterium. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 26, 177–181 (2003).

Tsuchiya, C., Sakata, T. & Sugita, H. Novel ecological niche of Cetobacterium somerae, an anaerobic bacterium in the intestinal tracts of freshwater fish. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46, 43–48 (2008).

Ramírez, C., Coronado, J., Silva, A. & Romero, J. Cetobacterium is a major component of the microbiome of giant amazonian fish (Arapaima gigas) in Ecuador. Animals 8, 189 (2018).

Van Kessel, M. A. et al. Pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons to study the microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract of carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). AMB Express 1, 41 (2011).

Larsen, A., Mohammed, H. & Arias, C. Characterization of the gut microbiota of three commercially valuable warmwater fish species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 1396–1404 (2014).

Cammarota, G. et al. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 66, 569–580 (2017).

Golloso-Gubat, M. J. et al. Gut microbiota and dietary intake of normal-weight and overweight Filipino children. Microorganisms 8, 1015 (2020).

Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Smart Breeding (Co-construction by Ministry and Province), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affair (2023-TJAULSBF-2105), and the Innovation Team of the Tianjin Mariculture Research System (ITTMRS2021007). Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data and metagenomic analysis were conducted using the Novomagic Platform, a free online service. Meanwhile, metabolomic data were analyzed using the APT-BioCloud platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, made the figures, and wrote the paper; J.S. conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript; B.J., K.C., L.G. and Z.S. assisted in performing the experiments; A.W. was responsible for the execution and quality control of the laboratory work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Teresa Nogueira and Zhigang Zhou the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joao Valente.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Z., Sun, J., Jiang, B. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation accelerates restoration of florfenicol-disturbed intestinal microbiota in a fish model. Commun Biol 7, 1006 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06727-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published: