Abstract

Habitat transitions in living organisms are key innovations often coupled with species diversification after their successful adaptation to new environment. The Cyrenidae is among the most well-known heterodont bivalve groups that have successfully invaded freshwater systems from brackish water environments and display diverse lineage-specific developmental modes. Phylogenetic and molecular clock-based divergence time analyses using 12 complete mitochondrial genome sequences suggest that Cyrenidae species independently colonized freshwater habitats during three distinct spatial and geological periods: one from the American continents approximately in the Early Jurassic and the two others from Australasian/East Asian continents in the Early/Middle Cretaceous and the Paleogene-Neogene boundary, respectively. This study provides significant insight into the temporal and spatial patterns of multiple freshwater invasions, aligning with ancient vicariance events inferred from different geological timelines of plate tectonics. Additionally, mitogenome phylogeny confirms the earlier hypothesis of the repeated parallel evolution of parental care system within this bivalve group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Habitat transitions in living organisms, such as moving from sea to land (including freshwater), are key innovations that are often coupled with species diversification after their adaptive radiation to new habitat environments1. Nevertheless, evolutionary patterns and timing of such habitat transitions are highly diverse depending on the clade-specific evolutionary histories across the Metazoan tree of life. The family Cyrenidae (previously known as Corbiculidae) is one of the two primary freshwater heterodont bivalve families (along with Sphaeriidae) with independent origins that have successfully colonized inland aquatic systems2,3,4. This family includes more than a hundred species that inhabit diverse aquatic systems worldwide (except for the Antarctic region), from brackish water to lentic and lotic freshwater environments4,5. The genera Polymesoda, Villorita, and Geloina constitute estuarine brackish water members, while Batissa species are euryhaline that inhabit both freshwater river systems and freshwater-estuarine interface. In contrast, all other members, belonging to the genera Corbicula (excluding a brackish water species C. japonica in East Asia) and Cyanocyclas, inhabit freshwater environments in the temperate/tropical regions of Asia, Australia, Africa (Corbicula), and Central and South America (Cyanocyclas)6,7. Of these, Asian freshwater Corbicula species have garnered significant interest because of their invasive potential in many exotic freshwater systems in North America, South America, and Europe8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Cyrenidae species also exhibit a wide spectrum of lineage-specific reproductive modes, ranging from planktotrophic development to parental care system with maternal incubation15,16. The brackish water species belonging to the genera Polymesoda, Villorita, and some Corbicula species exhibit indirect reproduction modes: For instance, C. japonica (the Asian brackish water species) and C. sandai (Lake Biwa endemic in Japan) are sexual species that show gonochoristic, non-brooding, and indirect development with planktotrophic larvae17,18, termed as “oviparity”16. In contrast, most other freshwater Corbicula members and the South American freshwater species Cyanocyclas limosa (hereafter, Cy. limosa) are hermaphroditic and show parental care systems with an internal incubation of their juveniles in maternal gills16. Along with their asexual reproduction (i.e., androgenesis) and high fecundity, these developmental traits provide Corbicula lineages with a remarkable invasive potential in exotic freshwater environments worldwide19,20. Given that a wide array of habitat type and diversity in their reproductive mode among Cyrenidae species, reconstructing a robust phylogeny is key to precisely understand the evolutionary diversification of their reproduction modes and patterns of adaptive radiation in freshwater environments.

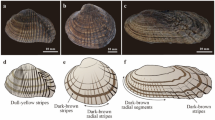

However, notably high degrees of variation in shell morph and color of Cyrenidae species have not only led to a plethora of taxonomic disagreements and nominal species but have also hampered the correct estimation of their phylogenetic relationships7,16,18,21,22,23. In the past decade, the application of molecular markers using the partial mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) cox1 gene fragment has helped in species identification for many regional populations worldwide23,24,25,26,27 and phylogenetic relationships among Corbicula lineages in their native18 and introduced regions28. The most recent phylogenetic analysis of the mtDNA cox1 gene fragment, with a special focus on the genus Corbicula (the most specious and reproductively well-characterized group of the family), highlighted the repeated, independent evolution of viviparity among Corbicula species16. Nevertheless, there are still some unresolved issues regarding sister relationships among Cyanocyclas, Polymesoda, and Corbicula groups, which preclude a comprehensive understanding of the evolutionary patterns related to their habitat transition and reproductive traits across the entire family.

In this study, in order to test hypotheses of the evolutionary origins of habitat transitions and reproductive modes within the phylogenetic context of the Cyrenidae, we performed phylogenetic analysis and estimated molecular clock-based divergence times using 12 complete mitochondrial genome sequences (eight of which were newly determined) representing the New World and Old World taxa that occupy both brackish and fresh waters, with a wide range of reproduction modes. We also reconstructed the ancestral state of habitat types, reproduction modes, and ancestral biogeography across the Cyrenidae species. Our results confirm the hypothesis of multiple, separate freshwater invasions from brackish habitats associated with repeated origins of parental care (i.e., direct development with an internal incubation of their juveniles) from ancestors with external, planktotrophic development. The timing of these radiations into freshwater environments reflects ancient vicariance associated with plate tectonic events from the Early Jurassic to the Pliocene.

Results

Phylogenetic relationships among Cyrenidae species

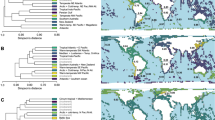

The mitochondrial genome trees reconstructed with the ML and BI methods using a concatenated dataset (12,909 nucleotide sequences) of the 13 PCGs were identical with respect to their tree topology, and almost all internal branches were strongly supported by high supporting values (Fig. 1). The resulting phylogenetic trees identified the Cyrenidae species as monophyletic (1.00 BPP in BI and 100% BP in ML) and subsequently subdivided them into two well-supported clades, i.e., the New World clade (clade I) and the Old World clade (clade II), each receiving high branch supports (1.00 BPP in BI and 88% BP in ML for clade I, and 1.00 BPP in BI and 98% BP in ML for clade II). Within the New World clade, the South American freshwater species Cy. limosa is the sister group of the North/Central American salt marsh clams, Polymesoda species (P. floridana and P. caroliniana) (1.00 BPP in BI and 97% BP in ML analysis). In the Old World clade, two strongly supported monophyletic groups were found: (1) Geloina species group (G. coaxans and G. erosa) representing East Asian/Australasian/Indian species and (2) the remaining group contains V. cyprinoides (brackish water species endemic to India), B. violacea (euryhaline species that are found in rivers and freshwater-estuarine interface in East Asia, Australasia and India), and the Asian Corbicula group. Within the genus Corbicula, the brackish water species C. japonica was positioned at the basal position to the Asian freshwater species C. sandai (Lake Biwa endemic in Japan) and C. fluminea, C. leana (including the African C. madagascariensis and the Australian C. australis, when only cox1 and 16S partial sequences were used for the analysis; Supplementary Fig. 1). The inferred relationships among Corbicula members are generally consistent with previous analyses of partial sequences of the mtDNA cox1 gene fragment16,18.

Estimation of divergence time among major cyrenid lineages

Separation between the New and Old World Cyrenidae clades was estimated at approximately 200.7 MYA during the Triassic-Jurassic boundary (Fig. 2) and was almost immediately followed by lineage splitting of Cy. limosa from the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) of Polymesoda species (P. floridana and P. caroliniana) within the New World clade, dating back to ~186.7 MYA. Within the Old World clade, separation of the clade II members of Villorita and Batissa+Corbicula from the genus Geloina was estimated near the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (142.5 MYA) in the Mesozoic Era, followed by separation of V. cyprinoides from the common ancestor of Batissa+Corbicula species group in the Middle of Cretaceous period (102 MYA). The divergence between B. violacea and the genus Corbicula was estimated to occur shortly after the separation of V. cyprinoides from their common ancestor, approximately 90.3 MYA. The molecular-clock-based divergence time analysis estimated that the brackish water Asian clam C. japonica split first from the most common ancestor of the freshwater Corbicula assemblages of C. sandai + C. fluminea + C. leana at the Paleogene-Neogene boundary (24.7 MYA) and followed by the separation of C. sandai from their freshwater congeners C. leana and C. fluminea at the beginning of Pliocene epoch, approximately 5.7 MYA.

Reconstruction of ancestral character state of habitat types and reproduction modes across the Cyrenidae species

We employed a maximum likelihood approach to reconstruct the most probable ancestral states of habitat types across the phylogeny of Cyrenidae species. The results revealed that all ancestral nodes within both the New World and Old World clades were initially inhabited by brackish water species, which subsequently gave rise to descendant species that independently invaded freshwater environments (Fig. 3a). This suggests multiple independent invasions from brackish water environments to freshwater habitats within the family Cyrenidae. Additionally, we estimated the ancestral reproduction mode of Cyrenidae species using maximum likelihood analysis. The reconstructed ancestral mode for all cyrenid species was most likely represented by indirect, planktotrophic species, except for three species at the terminal tips of the phylogenetic tree (Cy. limosa in the New World clade and C. fluminea and C. leana in the Old World clade, respectively; Fig. 3b), which exhibited direct development with parental care. This result indicates that the parental care system (i.e., direct development with internal incubation of juveniles) is an independently derived state within the family Cyrenidae.

Ancestral state reconstruction for habitat types (a) and reproduction modes (b) using maximum likelihood approach. A pie chart at each node indicates the relative likelihoods for their corresponding ancestral characters. Details of relative likelihood ratios for each node are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Historical biogeography of the Cyrenidae species

Our analysis for ancestral biogeographic history suggested that the ancestor of Cyrenidae species was estimated to have had a wide distribution spanning East Asia, India, and Australasia (A, B, and C in Fig. 4). After a cladogenesis from the Old World clade, North and Central America (E) were estimated to serve as the most likely biogeographic origin for the New World clade species, with the common ancestor of Cy. limosa later occupying freshwater environments in the South American continent (D) during the early Jurassic period. It was also revealed that the most recent common ancestor of the Old World Cyrenidae species had a widespread distribution across Australasia, India, and East Asia. Meanwhile, V. cyprinoides remained in India after their lineage split from their nearest common ancestor, which gave rise to the group of B. violacea and East Asian Corbicula species. Although our analysis of ancestral area reconstruction suggested the Old World regions as a biogeographic origin for major Cyrenidae lineages, uncertainty still remains regarding the origin of the genus Corbicula, mainly due to insufficient taxon sampling from their native ranges (see further details in the Discussion section). Our analysis was based on the geographic distribution of extant species rather than fossil records, and thus further confirmation from fossil records is required.

Colored rectangles along the internal and terminal branches represent the ancestral biogeographic ranges and contemporary distribution of their native populations, respectively, corresponding to a world map categorized into five divisions of the continents: A East Asia, B India, C Australasia, D South America, and E North/Central America. For instance, the “ABC” at each internal node indicates that the ancestral biogeography includes East Asia (A), India (B), and Australasia (C).

Discussion

To fully understand the evolutionary patterns of habitat transitions and developmental modes across the family, we reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships among Cyrenidae members (covering almost all genera) based on complete mitochondrial genome information. The distribution patterns of freshwater species across the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1) provide valuable information on the evolutionary scenarios of habitat shifts. The resulting mitochondrial genome tree uncovered two well-supported clades (clades I and II), each showing their own distinct geographic distribution of the New World American continent and the Old World Australasian/East Asian continents (including the Indian subcontinent). Each of these clades includes a mixture of both freshwater and brackish water species. Within the New World clade (clade I), the South American freshwater species Cy. limosa is sister to the North/Central American brackish water Polymesoda species (P. floridana and P. caroliniana). On the other hand, in the Old World clade (clade II), the Australasian/Indian/East Asian brackish water species (G. coaxans and G. erosa) were sister to the remaining group that contained V. cyprinoides (Indian brackish water species), B. violacea (inhabits freshwater river systems and are also found in freshwater-estuarine interface in East Asia, Australasia, and India), and Asian Corbicula species assemblage (a mixture of brackish water and freshwater species). Note that the freshwater members of Cyrenidae (i.e., Cy. limosa, B. violacea, C. sandai, C. fluminea, and C. leana) were split into two different clades (I and II) and independently grouped with brackish water species as their respective sisters. These results indicate that the Cyrenidae species independently invaded freshwater habitats in different continents at least at three geological intervals, i.e., one in the American continent and the other two in the Australasia-India and East Asian continents (Figs. 1 and 2). Our analysis for ancestral state reconstruction of the habitat types revealed that all ancestral nodes within both the New World and Old World clades were initially inhabited by brackish water species, giving rise to descendant species (Cy. limosa in New World and C. sandai, C. fluminea, and C. leana in Old World clades, respectively) that independently invaded freshwater environments (Fig. 3a). This finding supports our hypothesis of multiple independent freshwater invasions within the family Cyrenidae. In the American continent, Cy. limosa was estimated to have diverged from the common ancestor of the North/Central American brackish water Polymesoda species at approximately 186.7 MYA (Fig. 2) and assumed to have invaded freshwater environments in South American continent since that time. The timing of the lineage splitting and the subsequent freshwater invasion achieved by Cy. limosa approximates the Early Jurassic period when the western part of Gondwana (containing South America and Africa) began to separate from the rest of the supercontinent (containing North America) alongside the opening of the Central American Seaway, which later became the North Atlantic Ocean, including the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea.

In the Old World clade, our phylogenetic tree also showed that each of the freshwater Corbicula species (C. sandai, C. fluminea, and C. leana) and euryhaline B. violacea species nested within the brackish water species Geloina species (distributed in Australasia including the Indo-Pacific islands and some East Asian countries), V. cyprinoides (endemic to India), and C. japonica (native to East Asia), respectively (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the two separate habitat shifts to freshwater environments might have occurred independently by Batissa and Corbicula species across Australasia, India, and East Asia) after each of their common ancestors diverged from the Australasian/Indian/East Asian brackish water species (represented by Geloina species and V. cyprinoides, respectively) and East Asian brackish Corbicula species (i.e., C. japonica) (Fig. 3a). Molecular clock analysis estimated that the separation between V. cyprinoides and Geloina species occurred at approximately 142.5 MYA, followed by the first freshwater invasion of Batissa species in the Old World after their common ancestor diverged from the Indian brackish water species V. cyprinoides, approximately 102 MYA (Figs. 1, 2, and 3a).

According to the plate tectonics theory, the Indian plate remained bound with the Antarctica/Australian landmass as a part of the supercontinent Gondwana until approximately 150 MYA, separating from the remaining in the Early Cretaceous (130 MYA29). Paleogeographic evidence of initiating the separation of India approximates the divergence time of the Indian V. cyprinoides from Geloina species in Australasia, India, and East Asia (142.5 MYA), however, it is unclear whether V. cyprinoides (endemic to India) was the immediate origin of the freshwater invasion of Batissa species, as the internal branch giving rise to B. violacea from V. cyprinoides was not robustly supported in our phylogenetic tree (0.91 BPP in BI and 67% BP in ML; Fig. 1). The Batissa species are euryhaline (capable of surviving in a wide range of salinity) and are mainly found in freshwater river systems and freshwater/brackish interface in Indian/Australasian/East Asian regions. Results from our ancestral state reconstruction analysis suggest that the most likely habitat type for the ancestral node of B. violacea + V. cyprinoides was a brackish water environment (Fig. 3a). Considering their habitat ecology and distribution range, it is also conceivable that the ancestral stenohaline brackish Batissa species, or undocumented extinct lineages of marine/brackish water cyrenid species (not clearly defined in this study), which were formerly distributed in the Gondwana land (excluding Antarctica), might have invaded freshwater environments near the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary (142.5 MYA) after a direct divergence from Geloina species, rather than through an immediate transition from the Indian brackish water species V. cyprinoides. Nevertheless, we remain uncertain about the exact timing and direct origin of the freshwater invasion in the Indian/Australasian continents based on this mitochondrial genome phylogeny, thereby necessitating further investigation using different molecular markers based on extensive taxon sampling for unsampled cyrenid species from these continents.

On the other hand, the genus Corbicula is the most specious cyrenid group that inhabits various aquatic ecosystems ranging from estuarine brackish water to lentic and lotic freshwater environments4,5. In addition to East Asian brackish water species C. japonica Prime, 1864 and C. fluminalis (O. F. Müller, 1774), all other Corbicula members inhabit lakes and rivers in many Asian countries, Australia, the Middle East, Africa, and Madagascar, as their native ranges6,16,30. In our phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), C. japonica was positioned basal to C. sandai (endemic to Lake Biwa in Japan), C. fluminea and C. leana (the most widely distributed lineages in Asian freshwater environments18). Results from the ancestral state reconstruction analysis revealed the brackish water habitat as likely the most ancestral habitat type for Corbicula species (Fig. 3a). The molecular clock-based analysis estimated that the divergence time of TMRCA (the most recent common ancestor) of these Asian freshwater Corbicula species from C. japonica was at the Paleogene-Neogene boundary (24.7 MYA), which was followed by lineage splitting of C. sandai and C. fluminea + C. leana at the beginning of Pliocene epoch (approximately 5.7 MYA). Based on this inferred chronology (Fig. 2), the freshwater invasion into Lake Biwa achieved by the ancestor of C. sandai approximates to the age of the Lake Biwa formation dating back to at least 4 MYA estimated from stratigraphic studies31,32. The inferred divergence time of C. sandai from its congeneric species predates the age of the Lake Biwa, but it falls within the range of a 95% HPD (highest posterior density) credible interval (3.98-7.42 MYA). Lake Biwa is one of the most ancient lakes in temperate Asia, maintaining a high species richness (harboring more than 1000 plant and animal species) and endemism (including approximately 60 endemic species33,34). Owing to its long-term environmental stability, Lake Biwa was once considered a potential driver of species diversification in some biota, including freshwater fishes35. However, it is uncertain whether C. sandai serves as a potential origin for many other Asian freshwater Corbicula species. This uncertainty arises from our limited taxon sampling in mitochondrial genome phylogeny, which covers only a few Asian Corbicula species and lacks many other representatives distributed outside East Asia, such as those found in their native range of Australasia, India, and Africa, including Madagascar. Consequently, the present study is unable to elucidate the timing and evolutionary origin of freshwater invasion outside East Asia, particularly for the African species, including the Madagascar endemic C. madagascariensis. Indeed, the African Cyrenidae is solely represented by a couple of limnic Corbicula species, with no brackish water species discovered to date. Furthermore, previous studies have not thoroughly investigated the taxonomy and phylogeny of African Corbicula species. Only a few exceptions have included certain African forms (such as C. africana and C. madagascariensis) in their taxonomic and phylogenetic analyses16,24,30 (see also Supplementary Fig. 1 in this study). This limitation emphasizes the necessity for an in-depth analysis of shell morphology, soft body anatomy, and reproductive traits (including sperm morphology and brooding/non-brooding developmental modes) of African Corbicula species based on an extensive taxon sampling throughout the African continent, along with further validation using molecular analysis. A comprehensive analysis based on an extensive taxon sampling throughout their native ranges, particularly from non-East Asian Corbicula species including C. madagascariensis (Madagascar) and C. australis (Australia) will provide compelling insights into the evolutionary history of their freshwater invasion and ancestral biogeographic origin for the genus Corbicula. Nonetheless, the present study confirms multiple independent invasions into freshwater environments on different continents (the New World and Old World continents) at different geological intervals (from the Early Jurassic to the Pliocene) among major Cyrenidae species.

In the great majority of invertebrate groups, including mollusk species, oviparous reproduction modes (indirect development via free-swimming planktotrophic larva) are predominant, with a small exception of viviparous species (direct development with parental care), which are considered to have evolved from an oviparous mode36,37. In freshwater bivalves, evolutionary changes in reproductive modes and life history traits are believed to be relevant to their invasive success and increased colonization potential in newly introduced environments19,38,39. Likewise, Cyrenidae species show a wide spectrum of diversity in their reproductive modes: Non-brooding indirect development via planktotrophic larvae is found in all brackish water members (Polymesoda, Geloina, V. cyprinoides, and C. japonica species) and some freshwater species C. sandai (Lake Biwa endemic) and B. violacea (Australasia and India). Contrarily, parental care system (i.e., direct development with an internal incubation of their juveniles in maternal gills) is widely found in many other freshwater Corbicula and South American Cyanocyclas species15. Glaubrecht et al.16 subdivided this parental care system of Cyrenidae species into two types of viviparity depending on the duration of maternal incubation: ovoviviparity (short-term incubation found in the majority of freshwater Corbicula species) and euviviparity (relatively prolonged incubation found in C. madagascariensis and South American Cy. limosa species). In most cases of clonal reproduction (i.e., androgenesis), maternal DNA is discarded after an oocyte is fertilized by an unreduced sperm, resulting in diploid progeny with no maternal nuclear DNA (see Vastrade et al.,39 for details of androgenesis in freshwater Corbicula lineages). Previous studies16,18,24, utilizing molecular analyses of mtDNA cox1 partial sequences compiled from diverse Corbicula species revealed that the estuarine C. japonica species with indirect development mode occupied a basal position relative to the freshwater Corbicula clade, where majority of freshwater species with parental care system sampled from different geographic origins (e.g., Madagascar, Australia, Indonesia, and Asia) were mixed with the indirect, planktotrophic species C. sandai (see Glaubrecht et al.,16 for details). Nevertheless, phylogenetic relationships among Cyanocyclas, Polymesoda, and Corbicula groups were not fully resolved, and the phylogenetic position of C. sandai within the diverse freshwater Corbicula assemblages was not confirmed (<50% bootstrap value). In our mitochondrial genome tree (Fig. 1), the cyrenid species with parental care system (C. fluminea, C. leana, and Cy. limosa) were split into different clades (clades I and II), each containing indirectly developing planktotrophic brackish/freshwater species as their sisters. The ancestral state reconstruction analysis for reproduction mode revealed an indirect development with a planktotrophic stage as the ancestral state in both New World and Old World clades (Fig. 3b). Subsequently, within each clade, a parental care system was independently derived from Cy. limosa (in the New World clade), and C. fluminea and C. leana (in the Old World clade). Taken together, the emergence of a parental care system in the South American freshwater species Cy. limosa (euviviparous), independently from the East Asian freshwater Corbicula lineages (ovoviviparous) potentially including African C. madagascariensis (euviviparous) and C. australis (ovoviviparous) (see Glaubrecht et al.,16 and Supplementary Fig. 1) supports the earlier hypothesis of repeated evolution of parental care system in freshwater Cyrenidae species.

This study provides the first complete mitochondrial genome phylogeny of the family Cyrenidae, which is one of the two major heterodont bivalve groups that have successfully invaded lentic and/or lotic freshwater environments. Along with the findings from the ancestral state reconstruction analyses for habitat types, reproduction modes, and biogeographic origins, the inferred phylogenetic relationships and estimated divergence times among the major cyrenid lineages strongly confirm the hypothesis of multiple freshwater invasions and repeated parallel evolution of the parental care system during the evolutionary diversification of Cyrenidae species. The biogeographic patterning and timing of freshwater invasion advocated in this study are concordant with ancient vicariance events that reflect ancient plate tectonics. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the present study was based on a single molecular marker (the mitochondrial genome) and limited taxon sampling for Corbicula species, particularly from outside East Asia. Therefore, our findings require further clarification using additional genetic (nuclear) markers, along with an extensive taxon sampling from throughout their native ranges in future studies.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

For mitochondrial genome sequencing, samples of the target species were directly collected or obtained from museum loans (see Table 1 for detailed information). Genomic DNA was extracted from mantle tissues using an E.Z.N.A. Mollusc DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mitochondrial genome sequence assembly

For mitochondrial genome sequencing of C. japonica, C. sandai, B. violacea, G. erosa, P. floridana and P. caroliniana species, NGS libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq DNA library preparation kit and sequenced using a 151 bp paired-end run on the Illumina HiSeq X sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Low-quality reads and adapter sequences were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.3940, and the clean reads (C. japonica [397,026,361]; C. sandai [389,195,610]; B. violacea [9,575,886]; G. erosa [267,407,231]; P. floridana [191,693,515]; P. caroliniana [13,845,308]) were de novo assembled into circular DNAs using NOVOPlasty v4.241. Trimmed reads were re-mapped to the constructed mitochondrial genome using Bowtie2 v2.4.142 and polished using Pilon v.1.2343.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and mitochondrial genome sequencing

For mitochondrial genomes of C. fluminea and Cy. limosa, we used the conventional long PCR method. Initially, four partial gene fragments, cox1, cox3, cob, rrnS, and rrnL were individually amplified by PCR using the primer sets LCO1490/HCO219844, cox3F/cox3R45, UCYTB144F/UCYTB272R46, 12SF/12SR47, and 16SarL/16SbrH48, respectively. PCR amplification was conducted with Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Japan) in a reaction mixture of 50 μl containing 3 μl of template DNA, 5 μl of 10X Taq buffer, 4 μl of dNTP mixture, 2 μl of each for forward and reverse primers, 0.25 μl of TaKaRa Ex Taq polymerase, and 33.75 μl of distilled water. Amplification conditions comprised one cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 46–60°C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. Species-specific primer sets for long PCR amplification were designed from nucleotide sequences of the four partial gene fragments (see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed information of primer sequences). Long PCR products (size: 2–6 Kb) were obtained in reaction mixture of 50 μL containing 1 μL of template DNA, 5 μL of 10x Taq buffer, 1 μL of each primer, 8 μL of dNTP, 4 μL of MgCl2, 0.5 μL of LA Taq DNA polymerase, and 29.5 μL of distilled water. The following amplification conditions were used: one cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing using a gradient of temperatures in the range of 55–65°C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min per kb, and a final extension at 72 °C for 15 min. The amplified PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels using a QIAquick gel extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) following standard protocols and sequenced directly using an ABI PRISM 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the same primers used for PCR or by primer walking. Nucleotide sequences of the PCR-amplified fragments were analyzed using Geneious Prime 2021.0.1 (Biomatters, New Zealand).

Mitochondrial genome annotation

Complete mitochondrial genomes were annotated using the MITOS webserver49. Protein-coding genes (PCGs) were identified using the Find ORF function in Geneious Prime and confirmed by comparison with other the sequences of Cyrenidae species available in GenBank (C. leana, V. cyprinoides, G. coaxans, and G. erosa). Two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes (rrnL and rrnS) were identified by sequence comparison with the previously reported rRNA genes from other cyrenid species. Transfer RNA (tRNA) genes were identified using the tRNAscan-SE search server v. 2.050 and confirmed by manually inspecting potential cloverleaf secondary structures and anticodon sequences.

Phylogenetic analyses

We used the nucleotide sequences of 13 PCGs derived from 12 complete mitochondrial genomes of cyrenid species for phylogenetic analyses, including two venerid species, Mercenaria mercenaria, and Ruditapes decussatus as outgroups (Table 2). The nucleotide sequences of 13 PGCs were individually translated into amino acid sequences, multiple-aligned by ‘reverse translation’ of the aligned protein sequences using the RevTrans 2.0 webserver51, and concatenated using MEGA v1152. The best-fit substitution models for the nucleotide sequences of each of the 13 PCGs were identified (Table 3) using jModelTest53 on the CIPRES webserver54. Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) method with RAxML 8.2.955 and Bayesian inference (BI) with MrBayes 3.2.656 using the CIPRES portal54. Bootstrap analysis was performed with 1000 pseudo-replicates to estimate the bootstrap percentage (BP) in the ML tree. BI analysis was performed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, with two independent runs of 1×106 generations with four chains, sampled every 100 generations. Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) values were estimated after discarding the initial 5% as burn-in, confirming the MCMC chains reached full stationarity.

Estimation of divergence times among major cyrenid lineages

Divergence times among major lineages of Cyrenidae were estimated using the nucleotide sequences of 13 PCGs with a relaxed clock log-normal model, random starting trees, and a calibrated Yule model in BEAST v.2.6.757. To estimate divergence time calibration, we set three calibration points based on the maximum and minimum ages of the stem group fossils of Venerida (445.6–452.0 MYA)58, Cyrenidae (182.8–190.8 MYA)59, and Geloina (61.6–66.0 MYA)60 respectively, that were referenced from their corresponding literature and Paleobiology Database (http://paleodb.org). The calibration points were implemented as log-normal prior distributions for the node age in BEAST. The Markov chain was run three times, each run comprising 1 × 108 generations, sampling every 1000 generations, with the first 10% of samples discarded as burn-in with Tracer v.1.7.261. The results were combined using a log combiner and tree annotator in the BEAST package. The maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree is shown in FigTree 1.4.4.

Reconstruction of ancestral state for habitat types and reproduction modes

We employed Phytools in the R package62 to reconstruct the ancestral states of habitat and reproductive mode for selected nodes across the phylogenetic tree of Cyrenidae species. Utilizing a time-calibrated maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree derived from BEAST analysis, we reconstructed the ancestral character states using a maximum likelihood approach. In reconstructing the ancestral states for the binary character states in their habitats (i.e., brackish water vs. freshwater habitats) and reproduction modes (planktotrophic vs. parental care), we used the equal rates (ER) model to ensure equal probability of all character changes. The traits used for these analyses (habitat types and reproduction modes) are shown in Table 2.

Reconstruction of historical biogeography

The ancestral biogeographic distributions of the Cyrenidae species were inferred using BioGeoBEARS in R package63, a model-based approach that implements likelihood statistics. The biogeographic analysis utilized the MCC tree resulting from BEAST analysis. To reconstruct ancestral biogeographic distributions, we categorized the biogeographical data of individual species examined in this study into five geographic areas representing their native populations (excluding introduced ranges). These regions were defined as (A) East Asia, (B) India, (C) Australasia, (D) South America, and (E) North/Central America, referencing distribution records from both the corresponding literature and the MUSELp Database (https://mussel-project.uwsp.edu/index.html). To perform BioGeoBEARS, we used three different models: Dispersal Extinction Cladogenesis (DEC)64, a likelihood version of the Dispersal–Vicariance (DIVALIKE)65, and BayArea-like (BAYAREALIKE)66. These models were further modified by incorporating a founder-event speciation parameter (+J), which allows for jump dispersal events during cladogenesis. This allows new lineages to disperse outside the region(s) where their ancestor occupied. The BAYAREALIKE+J was selected as best fit mode for our data from the likelihood ratio test (LRT) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC).

Statistics and reproducibility

As mentioned above, phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed using the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The bootstrap analysis of the ML tree was performed with 1000 pseudo-replicates using RaxML 8.2.9. For BI analysis, Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods were conducted with two independent runs of 1 × 106 generations using four chains sampled every 100 generations and discarded the initial 5% as burn-in. The ancestral state of habitat types and reproduction modes were reconstructed with a maximum likelihood approach using Phytools in R package. BioGeoBEARS in the R package was also used to infer the historical geographic distributions of the Cyrenidae species through a model-based approach that incorporates likelihood statistics.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mitochondrial genome sequence data newly determined in this study is deposited in the NCBI database under the accession numbers (see Table 2). The raw NGS data generated in this study were deposited in the NCBI database under the BioProject numbers (PRJNA1146340, PRJNA1146343-PRJNA1146345, PRJNA1146354, and PRJNA1146356). The concatenated nucleotide sequence dataset of the 13 PGCs used for phylogenetic analysis is available in the figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25992553).

Code availability

The input files and R codes used for ancestral state and historical biogeography reconstruction are available in the figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25990843).

References

Jamy, M. et al. Global patterns and rates of habitat transitions across the eukaryotic tree of life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 1458–1470 (2022).

Park, J. K. & Foighil, D. O. Sphaeriid and corbiculid clams represent separate heterodont bivalve radiations into freshwater environments. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 14, 75–88 (2000).

Taylor, J. D., Williams, S. T., Glover, E. A. & Dyal, P. A molecular phylogeny of heterodont bivalves (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Heterodonta): new analyses of 18S and 28S rRNA genes. Zool. Scr. 36, 587–606 (2007).

Graf, D. L. Patterns of freshwater bivalve global diversity and the state of phylogenetic studies on the Unionoida, Sphaeriidae, and Cyrenidae. Am. Malacol. Bull. 31, 135–153 (2013).

Bogan, A. E. Freshwater bivalve extinctions (Mollusca: Unionoida): a search for causes. Am. Zool. 33, 599–609 (1993).

McMahon, R. F. Ecology of an invasive pest bivalve, Corbicula. in The Mollusca (eds Russell-Hunter, W. D.) Vol. 6, 505–561 (Ecology Academic Press, 1983).

Morton, B. A review of Polymesoda (Geloina) Gray 1842 (Bivalvia: Corbiculacea) from Indo-Pacific mangroves. Asian Mar. Biol. 1, 77–86 (1984).

McMahon, R. F. The occurrence and spread of the introduced Asiatic freshwater clam, Corbicula fluminea (Muller), in North America 1924-1982. Nautilus 96, 134–141 (1982).

Araujo Armero, R., Moreno, D. & Ramos, M. A. The Asiatic Clam Corbicula fluminea (Muller, 1774) (Bivalvia, Corbiculidae) in Europe. Am. Malacol. Bull. 10, 39–49 (1993).

Lee, T., Siripattrawan, S., Ituarte, C. F. & Foighil, O. D. Invasion of the clonal clams: lineages in the New World. Am. Malacol. Bull. 20, 113–122 (2005).

Marescaux, J., Pigneur, L.-M. & Doninck, K. V. New records of Corbicula clams in French rivers. Aquat. Invasions 5, 35–39 (2010).

Cao, L., Damborenea, C., Penchaszadeh, P. E. & Darrigran, G. Gonadal cycle of (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae) in Pampean streams (Southern Neotropical Region). PLoS One 12, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186850 (2017).

Sheehan, R., Etoundi, E., Minchin, D., Van Doninck, K. & Lucy, F. Identification of the invasive form of clams in Ireland. Water 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/w11081652 (2019).

Bespalaya, Y. V., Aksenova, O. V., Kropotin, A. V., Shevchenko, A. R. & Travina, O. V. Reproduction of the androgenetic population of the Asian Clam (Bivalvia: Cyrenidae) in the Northern Dvina River Basin, Russia. Diversity 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/d13070316 (2021).

Korniushin, A. V. & Glaubrecht, M. Novel reproductive modes in freshwater clams: brooding and larval morphology in Southeast Asian taxa of (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Corbiculidae). Acta Zool. Stockh. 84, 293–315 (2003).

Glaubrecht, M., Fehér, Z. & von Rintelen, T. Brooding in (Bivalvia, Corbiculidae) and the repeated evolution of viviparity in corbiculids. Zool. Scr. 35, 641–654 (2006).

Furukawa, M. & Mizumoto, S. An ecological study on the bivalve ‘Seta-shijimi’, Corbicula sandai Reinhardt on the Lake Biwa. II. On the development. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish. 19, 91–94 (1953).

Park, J. K. & Kim, W. Two (Corbiculidae: Bivalvia) mitochondrial lineages are widely distributed in Asian freshwater environment. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 529–539 (2003).

Byrne, M. et al. Reproduction and development of the freshwater clam Corbicula australis in southeast Australia. Hydrobiologia 418, 185–197 (2000).

Pigneur, L. M. et al. Genetic uniformity and long-distance clonal dispersal in the invasive androgenetic clams. Mol. Ecol. 23, 5102–5116 (2014).

Britton, J. C. & Morton, B. A dissection guide, field and laboratory manual for the introduced bivalve Corbicula fluminea. Malacol. Rev. 15, 82 (1982).

Kijviriya, V., Upatham, E. S., Viyanant, V. & Woodruff, D. S. Genetic studies of Asiatic clams, Corbicula, in Thailand: allozymes of 21 nominal species are identical. Am. Malacol. Bull. 8, 97–106 (1991).

Sousa, R. et al. Genetic and shell morphological variability of the invasive bivalve (Muller, 1774) in two Portuguese estuaries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 74, 166–174 (2007).

Siripattrawan, S., Park, J. K. & Foighil, O. D. Two lineages of the introduced Asian freshwater clam occur in North America. J. Mollus Stud. 66, 423–429 (2000).

Renard, E., Bachmann, V., Cariou, M. L. & Moreteau, J. C. Morphological and molecular differentiation of invasive freshwater species of the genus Corbicula (Bivalvia, Corbiculidea) suggest the presence of three taxa in French rivers. Mol. Ecol. 9, 2009–2016 (2000).

Pfenninger, M., Reinhardt, F. & Streit, B. Evidence for cryptic hybridization between different evolutionary lineages of the invasive clam genus Corbicula (Veneroida, Bivalvia). J. Evol. Biol. 15, 818–829 (2002).

Park, J. K., Lee, J. S. & Kim, W. A single mitochondrial lineage is shared by morphologically and allozymatically distinct freshwater clones. Mol. Cells 14, 318–322 (2002).

Pigneur, L. M. et al. Phylogeny and androgenesis in the invasive Corbicula clams (Bivalvia, Corbiculidae) in Western Europe. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-147 (2011).

Veevers, J. J. & McElhinny, M. W. The separation of Australia from other continents. Earth Sci. Rev. 12, 139–143 (1976).

Korniushin, A. V. A revision of some Asian and African freshwater clams assigned to Corbicula fluminalis (Müller, 1774) (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Corbiculidae), with a review of anatomical characters and reproductive features based on museum collections. Hydrobiologia 529, 251–270 (2004).

Yokoyama, T. Stratigraphy of the Quaternary system around Lake Biwa and geohistory of the ancient Lake Biwa. in Lake Biwa, Monographiae Biologicae (ed Horie, S.) Vol. 54, 43–128 (1980).

Kawabe, T. Stratigraphy of the lower part of the Kobiwako group. J. Geosci. Osaka City Univ. 32, 39–90 (1989).

Nishino, M. Biwako no koyushu wo meguru mondai. koyushu list no ichibu shusei ni tsuite (The problem of endemics in Lake Biwa). Oumia 76, 3–4 (2003).

Nishino, M. & Hamabata, E. Naiko karano message (The message from “Naiko (lagoon around Lake Biwa)”). Sunrise Press, Shiga (in Japanese) (2005).

Tabata, R., Kakioka, R., Tominaga, K., Komiya, T. & Watanabe, K. Phylogeny and historical demography of endemic fishes in Lake Biwa: the ancient lake as a promoter of evolution and diversification of freshwater fishes in western Japan. Ecol. Evol. 6, 2601–2623 (2016).

Blackburn, D. G. Viviparity and oviparity: evolution and reproductive strategies. Encycl. Reprod. 4, 994–1003 (1999).

Lodé, T. Oviparity or viviparity? That is the question. Reprod. Biol. 12, 259–264 (2012).

Pigneur, L. M., Hedtke, S. M., Etoundi, E. & Van Doninck, K. Androgenesis: a review through the study of the selfish shellfish Corbicula spp. Heredity 108, 581–591 (2012).

Vastrade, M. et al. Substantial genetic mixing among sexual and androgenetic lineages within the clam genus Corbicula. Peer Community J. 2, e73 (2022).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Dierckxsens, N., Mardulyn, P. & Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw955 (2017).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–U354 (2012).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 9, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014).

Folmer, O., Black, M., Hoeh, W., Lutz, R. & Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 3, 294–299 (1994).

Boore, J. L., Macey, J. R. & Medina, M. Sequencing and comparing whole mitochondrial genomes of animals. Method Enzymol. 395, 311–348 (2005).

Merritt, T. J. et al. Universal cytochrome b primers facilitate intraspecific studies in molluscan taxa. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 7, 7–11 (1998).

Machida, R. J., Kweskin, M. & Knowlton, N. PCR primers for metazoan mitochondrial 12S ribosomal DNA sequences. PLoS One. 7, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035887 (2012).

Palumbi, S. R. et al. The simple fool’s guide to PCR, version 2.0. Univ. Hawaii, Honol. 45, 26–28 (1991).

Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: Improved metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 313–319 (2013).

Lowe, T. M. & Chan, P. P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W54–W57 (2016).

Wernersson, R. & Pedersen, A. G. RevTrans: multiple alignment of coding DNA from aligned amino acid sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3537–3539 (2003).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11 molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Darriba, D., Taboada, G. L., Doallo, R. & Posada, D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772–772 (2012).

Miller, M. A., Pfeiffer, W. & Schwartz, T. ‘Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees’. In 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE) 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/GCE.2010.5676129 (2010).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Bouckaert, R. et al. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006650 (2019).

Schmidt, F. Revision der ostbaltischen silurischen Trilobiten. Abtheilung I: Phacopiden, Cheiruriden und Encrinuriden. Mémoires de. L’Acad.émie Imp. ériale des. Sci. de. St. -Petersbourg, Ser. 7 30, 1–237 (1881).

Rosenkrantz, A. The Lower Jurassic Rocks of East Greenland Part 1. Medd. Om. Gronland 110, 4–122 (1934).

Glibert, M. Revision des Gastropoda du Danien et du Montien de la Belgique. I, Les Gastropoda du Calcaire de Mons. Inst. R. des. Sci. Naturelles de. Belgique, Mémoire 173, 1–115 (1973).

Rambaut, A., Drummond, A. J., Xie, D., Baele, G. & Suchard, M. A. Posterior summarization in Bayesian phylogenetics using tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 67, 901–904 (2018).

Revell, L. J. phytools 2.0: an updated R ecosystem for phylogenetic comparative methods (and other things). PeerJ 12, e16505 (2024).

Matzke, N. J. BioGeoBEARS: BioGeography with Bayesian (and likelihood) evolutionary analysis in R Scripts. R. Package Version 0. 2 1, 2013 (2013).

Ree, R. H. & Smith, S. A. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst. Biol. 57, 4–14 (2008).

Ronquist, F. Dispersal-vicariance analysis: a new approach to the quantification of historical biogeography. Syst. Biol. 46, 195–203 (1997).

Landis, M. J., Matzke, N. J., Moore, B. R. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. Bayesian analysis of biogeography when the number of areas is large. Syst. Biol. 62, 789–804 (2013).

Rahuman, S., Jeena, N. S., Asokan, P. K., Vidya, R. & Vijayagopal, P. Mitogenomic architecture of the multivalent endemic black clam (Villorita cyprinoides) and its phylogenetic implications. Sci. Rep. 10, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72194-1 (2020).

Hu, Z. et al. Complete mitochondrial genome of the hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4, 3738–3739 (2019).

Ghiselli, F. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of the grooved carpet shell, Ruditapes decussatus (Bivalvia, Veneridae). PeerJ 5, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3692 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Gazi Mihiuddin, and Taeho Kim for their help in mitochondrial genome sequencing. We also appreciate Danial Graf (University of Wisconsin) for his reading the manuscript with constructive feedback. This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A2C2005393).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K.P conceived and designed the study. H.K., A.T.S.H., J.K., and T.N. collected samples. H.K. and Y.L. designed the experiments and performed data analyses. J.K.P. and H.K. drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Katie Davis and David Favero.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwak, H., Lee, Y., Hwai, A.T.S. et al. Multiple origins of freshwater invasion and parental care reflecting ancient vicariances in the bivalve family Cyrenidae (Mollusca). Commun Biol 7, 1212 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06871-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06871-6