Abstract

Animal age at maturity can be used as a universal and simple predictor of species extinction risk. At present, methods to estimate age at maturity are typically species-specific, limiting comparisons among species, or are infeasible due to practical constraints. To overcome this, here we develop a universal predictor of species-level age at maturity for vertebrates. We show that modelling the frequency of ‘CG’ sequences (CpG sites) in gene promoter regions yields rapid predictions of vertebrate age at maturity. Our models predict age at maturity with remarkable accuracy and generalisability, with median error rates of 30% (less than 1 year) and are robust to genome assemblies of varying quality. We generate predictions for 1912 vertebrate species for which age at maturity estimates were previously absent from public databases. The predictions can be used to help to inform management decisions for the many species for which more detailed population information is currently unavailable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth’s contemporary biodiversity crisis creates, in turn, an environmental management crisis. With more than one-fifth of all vertebrates under threat, efficient approaches to identify the most vulnerable species are urgently required1. Approaches that enable rapid triage of the tens of thousands of species with unknown conservation status will allow for the best use of our limited wildlife management resources2. Animal age at maturity is a universal predictor of extinction risk that could prove to be a tractable and rapid assessment tool for the many species lacking more precise information3,4. Time to reach maturity determines both generation time and reproductive output and, thus, is a major driver of population growth rate in vertebrates3,5,6.

Despite its potential utility in conservation evaluations, age at maturity is difficult to measure in practice, particularly for species that are long-lived, rare, cryptic and/or have complex life histories. As a result, most methods to estimate age at maturity are indirect. Example techniques include predictive modelling based on physiological data in catsharks (Scyliorhinus canicula)7, a combination of mark-recapture, genotypic and geneology analyses in hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata)8, or the measurement of steroid hormones in whale faeces9. To enable the effective use of age at maturity as a comparative estimator of extinction risk among vertebrates, a universally applicable predictor of species age at maturity is required.

The frequency of CpG sites in gene promoters has recently been shown to predict age at maturity in mammals10 as well as lifespan in mammals, fish, and other vertebrates11,12,13. In vertebrates, gene promoters have distinct CpG distribution patterns that are highly predictive of epigenetic regulatory factors, such as DNA methylation and histone modification14,15, and can be used as an indicator of gene expression and regulation16. This ability to signify stable, dynamic, or repressed gene expression may explain CpG content’s remarkable ability to predict species life history parameters.

Here we use promoter CpG content to develop a universal method to predict species-level age at maturity in vertebrates. We include all species with suitable, publicly available genomic and age at maturity data to train and test the model (n = 1359 species). We evaluate improvements in prediction accuracy gained by developing group-specific models; one each for fish (n = 331), mammals (n = 550), and reptiles (including birds; n = 461). Promoter sequences are retrieved using homology to experimentally derived promoter sequences from humans (Homo sapiens) for the all-vertebrate and mammal-specific models, zebrafish (Danio rerio) for the fish-specific model and chicken (Gallus gallus) for the reptile model. Promoter CpG content is measured as CpG observed/expected ratio (CpG O/E; see ref. 17) and modelled with genomic GC percent and species order to account for any inherent differences in GC content. Prediction intervals are estimated using well-established uncertainty quantification methods. We then use genome sequence data to provide predictions and prediction intervals for 1912 species with previously unreported ages at maturity. The method is broadly applicable and will predict age at maturity for any vertebrate species for which whole genome sequence data can be obtained.

Results

Dataset description

We identified 1379 vertebrate species for which both age at maturity and whole genome sequence information were available, as indicated by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information’s (NCBI’s) genome representation category—either ‘full’ or ‘partial’ (see Supplementary Data 1 for NCBI genome accession numbers). For those 1379 species, a total of 7912 reported ages at maturity were obtained from publicly available databases, citing a combined 2261 original data sources (Supplementary Data 2). Three extreme outliers were removed from the dataset as their known age at maturity (calculated as the mean of reported values following data deduplication and species-level outlier removal; see the “Methods” section) resulted in a z-score > 8. These species were the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae; known age at maturity of 52 ± 18 years), the rougheye rockfish (Sebastes aleutianus; known age at maturity of 33 ± 32 years), and the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas; known at maturity of 32 ± 17 years) (Supplementary Data 2). A subset of 17 species did not return any promoter sequence matches during basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches (listed in Supplementary Data 3). Thus, the final dataset consisted of the remaining 1359 vertebrate species (Fig. 1A).

A Chronogram derived from TimeTree.org where each tip represents a single species (n = 1359), branches are coloured by group and shaded by species order (n = 109; shading is for comparison rather than distinction). Mean promoter CpG observed over expected ratio (O/E) is shown in the heatmap, where the inner circle represents data derived using human (Homo sapiens) reference sequences for all species, and the outer circle represents data derived using either zebrafish (Danio rerio), human, or chicken (Gallus gallus) reference sequences, according to the corresponding coloured groups (fish = green, n = 331; mammals = blue, n = 550; reptiles including birds = purple, n = 461; amphibians = yellow, n = 17). The known lifespan for each species, here defined as the mean of all reported lifespans, is shown in the bar plot (range ≈ 0.08–26 years). Species silhouette images were obtained from phylopic.org. B–D Show the distribution of known age at maturity, mean promoter CpG O/E and genomic GC content for each of the four coloured groups. Plots are annotated with the mean (x bar) value for each group, as well as the results letters denoting pair-wise comparisons using Tukey’s honest significant difference with Bonferroni correction following ANOVA. E Shows a peak in CpG O/E in the region surrounding the transcription start site (TSS) in zebrafish, human, and chicken, where the grey dotted lines denote the region used for analysis (±100 bp).

To generate group-specific models that were inclusive of poorly represented clades, we combined aquatic vertebrates with fins and gills to form the polyphyletic group “fish” (n = 331 species from 55 orders) and all species from clade Sauropsida to form the monophyletic group “reptiles” (n = 461 species from 31 orders). We note that the majority of this group comprises birds (n = 403 from 28 orders) (Fig. 1A). Mammals (n = 550 from 21 orders) and amphibians (n = 17 from 2 orders) were each designated their own group. Due to insufficient sample size, lack of appropriate reference promoter sequences, and high sequence divergence from other species, a group-specific model was not generated for or inclusive of amphibians.

Known ages at maturity ranged from 0.06 ± 0.006 years in the California vole (Microtus californicus) to 25.52 ± 0.87 years in the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) (Supplementary Data 2). Untransformed ages at maturity were right-skewed, and when log-transformed for modelling, followed an approximate normal distribution (Supplementary Fig. S1). Known ages at maturity were highly variable among species groups, but were generally higher in fish, followed by reptiles, mammals, and amphibians (Fig. 1B). Mean promoter CpG O/E was also highest in fish, followed by mammals, amphibians, and reptiles (for data derived using human reference sequences; Fig. 1C). Genomic GC content was similar among groups (Fig. 1D). The number of modelled features (i.e., predictors), mean (±SD) and median [min, max] CpG O/E in the raw, filtered and zero imputed data sets for all model groups (all-vertebrates, fish, mammals and reptiles) using their associated group-specific reference sequences (human, zebrafish and chicken) are provided in Supplementary Data 4. While background CpG O/E levels were elevated in zebrafish compared to human and chicken, there was a distinct peak in CpG O/E around the transcription start site (TSS) for all three species (Fig. 1E).

Ensemble model parameters

Nested cross-validation resulted in a total of 10 outer cross-validation models for each of the group-specific and all-vertebrate models. Each of the outer cross-validation models predicted age at maturity based on a unique combination of features, including promoter CpG O/E, genomic GC proportion and species order. Feature retention during elastic net regression was high for the mammal-specific model (n = 124–15,329; 1–100%), compared to the other models (n = 48–880; 2–21%) (Supplementary Figs. S4, S6, Supplementary Data 5). Greater feature retention is a result of lower optimised values of alpha (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Data 6), which may be attributed to high multicollinearity or dimensionality (p ≫ n) in the mammal-specific data set (Supplementary Data 4). Genomic GC proportion was selected by the elastic net regression for the all-vertebrate and mammal-specific models but not for the reptile and fish models (Supplementary Fig. S6, Supplementary Data 5). Species order was most frequently selected in the all-vertebrate and fish-specific models (median 61% and 57%, respectively) compared to the mammal- and reptile-specific models (median 38% and 20%, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S6, Supplementary Data 5). This is likely a reflection of the wider taxonomic distribution in these two polyphyletic groups.

The Pearson correlation between known and predicted age at maturity remained significant (p < 0.001) and substantial (R ≥ 0.62) for all models (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Data 6). The median Pearson correlation coefficients in the training datasets were above 0.87 (all-vertebrate: R = 0.9, fish-specific: R = 0.89, mammal-specific: R = 0.95 and reptile-specific: R = 0.9) and in the validation data sets above 0.68 (all-vertebrates: R = 0.82, fish-specific: R = 0.66, mammal-specific: R = 0.9 and reptile-specific: R = 0.77) (Supplementary Fig. S2; Supplementary Data 6). Correlations between training and validation datasets for all 10 models in all groups were similar, but there were slight differences in root mean squared error (RMSE) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Models that were potentially overfit were identified using Student’s two-sided unpaired t-tests to compare absolute error between training and validation data sets and were excluded from the final ensembles (Supplementary Fig. S3). The mean and median values for the model hyperparameters (alpha and lambda), number of features and performance measures (mean squared error, train—validate error significance levels and known–predicted correlation results) for all outer cross-validation loop models are included in Supplementary Data 6. The raw values are given in Supplementary Data 7.

Prediction accuracy

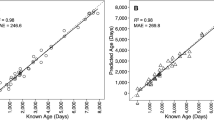

Age at maturity predictions generated by the four ensemble models are presented in Supplementary Data 8. We present both training and test data for completeness in the figures, but here report on metrics for the test dataset as these reflect the model’s likely performance on real-world data. The all-vertebrate model predicted age at maturity with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.78 (p < 0.001), explaining 61% of the total variance between known and predicted ages in the test data set (Fig. 2). Within the all-vertebrate model, group-wise correlations explained just 0.028% of the variance for fish, 84% for mammals and 21% for reptiles (Fig. 2). In contrast, the group-specific models explained 45% of the variance for fish, 86% for mammals and 52% for reptiles, demonstrating a substantial group-specific model improvement for fish and reptiles (Fig. 2). Models for relative age at maturity (age at maturity:lifespan) demonstrated reduced performance, with explained variances of 34% for the all-vertebrate model, 37% for the fish-specific model, 51% for the mammal-specific model and 26% for the reptile-specific model (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Prediction performance for the all-vertebrate model (top panels) and group-specific models (bottom panels). Plots show the relationship between the mean value for reported ages at maturity (known age at maturity) and those predicted by the model (predicted age at maturity) for all vertebrates (black), amphibians (yellow, n = 17), fish (green, n = 331), mammals (blue, n = 550) and reptiles (including birds; purple, n = 461). Results are separated into training and validation data (used for building the model; 85%) and test data (demonstrates the model’s likely performance on real-world data; 15%). The grey images depict which reference species was used to obtain promoter sequences for each model (either Homo sapiens, Danio rerio or Gallus gallus). The grey dashed line represents the identity line, and the solid lines illustrate the linear regression line. Each plot is annotated with performance metrics, including root-mean-squared error (RMSE; top left) as well as the Pearson correlation coefficient R, coefficient of determination R2 and associated p-value (bottom right).

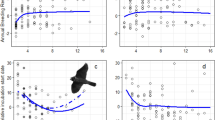

Prediction error followed a similar pattern, where the most substantial improvements were seen for fish and reptiles in the group-specific models (Fig. 3A). Relative error improved for all three group-specific models compared to the all-vertebrate model, but absolute error was similar for mammals in both models (Fig. 3A). Absolute and relative error were the highest for the test data in amphibians, likely owing to the small sample size available for this group (n = 17) leading to insufficient model training. Absolute error increased with divergence from the reference species and decreased with sequence similarity (mean hit identity, length and number of BLAST hits) for the all-vertebrate, fish and reptile models (Fig. 3B). The opposite trend was observed for all four measures in mammals, where the number of hits was far greater for mammals than other groups (Fig. 3B). This suggests that a large number of shared promoter sequences among mammals may have obscured age at maturity predictions compared to cases were only a small number of highly conserved and strongly predictive promoters are modelled.

A Comparison of prediction accuracy among age at-maturity models and species groups (fish = green, n = 331; mammals = blue, n = 550; reptiles including birds = purple, n = 461; amphibians = yellow, n = 17). Error is calculated as the absolute difference between the known and predicted ages. Labels denote the median absolute error (years) and relative error (%), and grey images depict which reference species was used to obtain promoter sequences. B Shows the relationships between prediction error and divergence time (from TimeTree.org) as well as promoter sequence similarity (as percent identity, length and number of BLAST hits). C Variability in predictions for species with multiple genome assemblies and associated non-duplicated NCBI biosamples, where genome contiguity is given as relative n50 (the assembly n50/the mean of all assembly n50s for that species). Black points and bars indicate the median and interquartile range, respectively. D Demonstrates the absence of a relationship between BUSCO genome completeness score and relative prediction error.

Within-species prediction variability

We identified a subset of species with between five and ten genome assemblies available from different individuals (as NCBI biosamples) for within-species prediction variability analysis, with a cumulative total of 98 genome assemblies for 14 species (see Supplementary Data 1 for accession numbers). Age at maturity predictions were highly consistent among different assemblies for a given species, lying close to the median in most cases (Fig. 3C). Those predictions falling outside of the interquartile range were typically associated with lower genome completeness or lower contiguity (as relative n50 score; the assembly n50/the mean of all assembly n50s for a given species) than other assemblies. Examples of this include brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) and goat (Capra hircus) (Fig. 3C). Despite this, low genome completeness score did not correlate with prediction error in the all-vertebrate model (Fig. 3D). These findings suggest that although the best genome sequence available should be used, the predictive method is robust to genome assemblies of varying quality. The results also demonstrate that species-level age at-maturity predictions can be generated from a single individual.

Gene function

We identified the top five genes that were most strongly associated with age at maturity in each of the four ensemble models (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Data 9). Within these 20 genes, five are reported to have a biased expression in testis (CARF, dpf1, map2k7, ZNF646 and RP3-336H9/RPGR), three in the ovary (kmt2a, RRP7A and HSP90AB1) and one in the endometrium and prostate (RP6-170F5/SERTM2) (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Data 9). We also observed three homeobox genes, namely LIM homeobox 8 (LHX8), homeobox C11a (hoxc11a), homeobox C3a (hoxc3a), where LHX8 is also reported to be involved in oogenesis in humans (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Data 9). In mammals, the top two most strongly associated genes were the related paired box 8 (PAX8) as well as FKBP prolyl isomerase 11 (FKBP11), whose activity is inhibited by rapamycin (Fig. 4A; Supplementary Data 9). The total number of gene functions associated with age at maturity-related promoters was 104 for the all-vertebrate model, 10 for the fish-specific model, 727 for the mammal model and 25 for the reptile model (Fig. 4B). Eight of these were shared among at least three groups (Fig. 4B). Most of the shared enriched functions were regulatory (n = 6), related to transcription (n = 3) and/or developmental (n = 2). RNA biosynthetic process was also enriched (Fig. 4C).

A Top five genes most strongly associated with species age at maturity in each model group. B Depicts the number of gene functions identified by enrichment analysis for each of the four model groups, and their relative overlap. C Functional enrichment results of the shared gene function from (B). The number of genes is given as total count (n = x) and the proportion of all queried (bracketed value). Only gene promoters with a significant Pearson correlation were included in the analysis. Further filtering methods are described in-text.

Comparison of mammalian genes whose promoters showed consistent associations between CpG density and age at maturity (present in >50% of bagged models) in this study and whose DNA methylation was found to be associated with age at maturity in a recent study18 revealed 9 common genes (Supplementary Fig. S7). These included genes related to sexual development (Oestrogen related receptor beta; ESRRB), cell death (Fas associated factor 1; FAF1), regulation of RNA processing and/or transcription (RNA binding motif protein 10; RBM10, Zinc finger MIZ-type containing 1; ZMIZ1 and Dicer 1 ribonuclease III; DICER1), immunity (LPS responsive beige-like anchor protein; LRBA), cell signalling (Transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 3; TRPM3), cell–cell interactions (Neuroplastin; NPTN) and cell division (Kinesin family member C3; KIFC3) (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Prediction intervals

The likelihood that the prediction interval covers the reported age at maturity value, indicated by the prediction interval coverage probability (PICP), remained relatively close to the nominal value of 90% for all three prediction interval estimation methods (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S8). Generally, coverage for species with middle-ranged ages at maturity for their respective groups was near complete, while species maturing at either very young or old ages typically showed lower coverage rates (Supplementary Fig. S8). This indicates that the prediction intervals are less likely to encompass the true value for exceptionally early and late-maturing species. PICP for the cross-validation (CV) method exceeded 90% in all cases, suggesting a slight overestimation of prediction error (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S8). The other two methods fell just short of the nominal coverage level, with the jackknife+-after-bootstrap (jackknife + ab) method performing marginally better than the mean and standard deviation (naive) method for the mammal-specific and all-vertebrate models (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S8). The naive and jackknife + ab methods produced similar interval widths, with naive producing a slightly narrower mean prediction interval width (MPIW) than the jackknife + ab method (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S8). The MPIW scores for the CV method were consistently the largest. To optimise the trade-off between narrow prediction width and high coverage probability, we selected the jackknife + ab method to generate the prediction intervals for previously unreported species ages at maturity.

Predicting previously unknown ages at maturity

To demonstrate the utility of our model, we also generated predictions for 1912 species for which genome sequences were available in NCBI, but age at maturity estimates were absent from online databases (see Supplementary Data 10 for predictions for species with previously unknown ages at maturity). Species were assigned conservation status based on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. In our dataset, 369 species were Not Evaluated, 68 Data Deficient, 1117 Least Concern, 97 Near Threatened, 135 Vulnerable, 67 Endangered, 53 Critically Endangered and 6 Extinct (Supplementary Data 10). Predicted ages at maturity for these species typically fell within the range of closely related species with known age at maturity, providing an indication of probable accuracy in the absence of reported values for ground truthing (Fig. 5). Age at maturity exhibited a significant correlation with IUCN Red List categories across fish, mammals and reptiles. The relationships were expectedly less pronounced for the predicted compared to the known values (Fig. 6; Supplementary Data 11). Relative age at maturity (age at maturity:lifespan) showed a much poorer relationship (maximum R = 0.07; Supplementary Fig. S9).

Predictions for 24 randomly selected species from 1912 whose age at maturity was not reported in public databases, ordered by model group (columns) and IUCN red-list category (rows). Age at maturity predictions are presented as point estimates (circles) with prediction intervals as upper and lower bounds (lines). Each species prediction is presented adjacent to reported age at maturity values (crosses) for the four closest relatives for which these data were available in our data set. Trees were derived from TimeTree.org.

Pearson correlations (R) and corresponding p-value (p) between age at maturity and species extinction risk, as International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List category, for IUCN-listed species whose age at maturity was not reported in public databases (‘Predicted’; fish: n = 645, mammals: n = 136, reptiles including birds: n = 687) and those with previously reported ages at maturity (‘Known’; fish: n = 231, mammals: n = 514, reptiles including birds: n = 435).

Discussion

We present a universal method to predict species age at maturity in vertebrates from genomic data. Specifically, we have developed four ensemble elastic net regression models: an all-vertebrate model, and three group-specific models, one each for fish, mammals, and reptiles. These models primarily use CpG content to predict species age at maturity. Group-specific models generally performed better than the all-vertebrate model, with median error rates of 25–34%, which correspond to 0.4–0.9 years. We used these models to generate predictions for 1912 species for which age at maturity estimates were previously unavailable in public databases. The method requires a moderate-quality genome assembly from a single individual, making it applicable to any vertebrate species for which an appropriate tissue sample can be obtained. Expensive, high-resolution assemblies or pangenome characterisation are not necessary, allowing for age at maturity to be estimated rapidly and cost-effectively.

Group-specific models generally outperformed the all-vertebrate model. This trend was most evident in fish, which may be an artefact of the fish-specific genome duplication event and/or the early divergence of ray-finned fish from tetrapods over 400 million years ago19. Conversely, for mammals, prediction error was similar in the all-vertebrate model compared to the group-specific model, likely owing to the use of human promoters as reference sequences in both models. Prediction accuracy was greatest for the mammal-specific model, followed by the reptile and fish models. This may be a result of a more recent divergence of a last common ancestor for mammals compared to fish and reptiles as defined here. Indeed, our results indicated that sequence divergence from the reference species led to greater prediction error and wider prediction intervals for the fish and reptile-specific models. Poorer model performance in fish may also reflect the polyphyletic nature of this group. Exponential increases in genome sequence availability and the release of experimentally derived promoter sequences for non-model species will, in the future, enable the development of models for more defined taxonomic groups and result in more accurate predictions of species age at maturity. This includes poorly represented groups such as amphibians, for which we were not able to generate a group-specific model here.

Here, we use promoter CpG content to predict age at maturity in vertebrates. However, age at maturity is also associated with other measures, including metabolic rate, body size, lifespan and number of cortical neurons20,21. The strongest predictor of age at maturity studied so far is DNA methylation, explaining 72% of the variation in known vs. predicted age at maturity in mammals18. These results are encouraging and highly comparable to the 90% and 86% variance explained for our mammal training and test data, respectively. We have further demonstrated that promoter CpG content is also predictive of age at maturity for reptiles (including birds), amphibians, and fish—the largest and most speciose vertebrate group. Thus, our promoter CpG content models are comparatively explanatory and more broadly applicable than other methods. Additional variables (e.g., lifespan and/or body size) could be added to the model in an attempt to improve prediction accuracy. However, the lack of available data for many of these measures would restrict the number of species that the model could be trained with, and substantially limit its application to novel species. At present, our age-at-maturity predictor has only two requirements: (1) that the species has a complete genome sequence available and (2) that the species order (taxonomic rank) is known.

Functional analysis of gene promoters predictive of age at maturity revealed enrichment for developmental and regulatory functions, as well as RNA biosynthetic processes. This is a likely reflection that a species' age at maturity is determined by the precise regulation of tissue transdifferentiation in reproductive organs and significant endocrinological changes to allow the development of secondary sexual characteristics22. In mammals, it has recently been shown that methyl-CpG-DNA binding protein 3 and DNA demethylase TET2 activate gonadotropin-releasing hormone 1 (GNRH1) expression in the hypothalamus leading to the onset of sexual maturation23. Modifications to the poly(A) tail of GNRH1 mRNA can prevent translation and result in delayed sexual maturity23. This suggests that RNA processing mechanisms may be driving the timing or onset of sexual maturation, at least in mammals. Identification of genes predictive of age at maturity in both DNA methylation18 and promoter CpG density models here showed that one-third of these genes have known roles in RNA processing and/or transcription in humans. Furthermore, our functional results suggest that transcriptional and RNA processing mechanisms may be common to all vertebrates, although the regulation of sexual maturity has been much less studied in other groups (i.e., birds and reptiles24).

Identification of the genes most strongly correlated with age at maturity revealed several homeobox genes—well-known master developmental control genes, some of which have roles in mammalian reproduction25. These developmental genes may be targets of polycomb-mediated H3K27me3 silencing, which commonly occurs in GC-rich regions and mediates aging and cellular identity26. We also identified the FBKP11 gene, a negative regulator of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway thought to play an important role in the onset of sexual maturation22. Over half of the genes most strongly associated with species age at maturity are known to be upregulated in reproductive tissues (testis, ovaries or endometrium and prostate) or are involved in germ cell formation27. This evidence indicates that our age-at-maturity model is not simply measuring general changes associated with ageing or lifespan but instead captures biological processes specifically related to reproductive maturation. These processes will have been subject to differing selection pressures among species, leading to different life history phenotypic adaptations and leaving traceable signals in the DNA.

To our knowledge, the models developed here are the most rapid means of estimating age at maturity in vertebrates. Predictions, along with their uncertainties, can be generated in under an hour given an appropriate genome sequence. Although our models could be tuned to select fewer features (gene promoters) to enable the generation of a more specific and affordable molecular assay, the loss in predictive power is unlikely to outweigh the potential benefits. We expect full-length genome sequences to become increasingly accessible with time, given steep declines in cost (<$5000 USD for contig-level assemblies) and the advancement of major genome sequencing efforts such as the Earth BioGenome Project and Beijing Genome Institute’s Fish10K28,29. We also expect that increases in the availability of ground truthing (training) data, and the potential ability to incorporate sex-based differences will mean that the accuracy and certainty of future predictive models will improve. At present, the use of genomic data to predict age at maturity offers a highly applicable and generalisable method that is universal to all vertebrate species. The novel incorporation of well-established methods to estimate prediction intervals here allows for adequate interpretation of the certainty of individual predictions. We hope that the release of nearly 2000 age-at-maturity predictions provides a useful resource for the management of those species for which age-at-maturity estimates are otherwise impractical to obtain.

The predictions of species age at maturity that we have developed are directly correlated with IUCN Red List status and can be applied or combined with other data types to model extinction risk in data-deficient populations. Extinction results from sustained or abrupt and extreme negative population growth rates30 and population growth rates depend on the aggregate effects of mortality and fecundity rates across the age classes in a population31, which vary extensively among species32. The mean age at maturity for a species that we predict here corresponds to the age class at which fecundity abruptly becomes positive. It also represents the generation time in many species, which is a strong predictor of extinction risk33. Assessments of life history pace and population growth potential from genomic data may be the only option for many species where resources for full-scale demographic studies are unavailable.

Genome analyses have been expected to produce a wide range of conservation benefits for animals since technologies for de novo genome assembly were revolutionised by high throughput DNA sequencing2,34. To date, genome analysis has produced valuable information on inbreeding, migration rates, community species composition, and functional adaptations35. Genomics has not, until recently, provided estimates of life history parameters. Accurate animal life history models are valuable for ensuring effective conservation actions. The model we present here builds on previous work in estimating animal lifespans11,13,36 so that estimates of the reproductive period (age at maturity to lifespan) of any vertebrate species can be estimated from genome sequences. These are the first steps in using the vast trove of genomic data that is now available to determine the life history parameters that are most valuable for conserving global animal biodiversity.

Methods

Data collection

Age at maturity estimates

Vertebrate age at maturity data were obtained from the AnAge database37, FishBase (fishbase.se; accessed 28/01/2024), the Amniote Life History Database38, PanTHERIA39, Animal Diversity Web (animaldiversity.org; accessed 11/11/2023) and directly from the literature (Supplementary Data 2). Because a single value is likely to be reported in multiple databases, any duplicated values were removed from the dataset. Outliers were detected using the interquartile range method, removing any data point falling 1.5 times below the first quartile or above the third quartile for a given species. Following deduplication and outlier removal, the mean of all reported values was calculated to obtain a single value for age at maturity for each species (‘known’ age at maturity herein). We chose to combine male and female estimates because (1) the reported value for age at maturity in males and females is the same or is only available for one sex for the majority of species and (2) few species have genome sequences available for both sexes, and the sex of the sequenced sample is frequently unavailable.

Promoter sequences

Vertebrate genomes for species with known ages at maturity were downloaded from NCBI (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/; accessed 28/01/2024) and ‘partial’ genome representations were excluded from the analysis. If multiple genome assemblies were available for a single species, NCBI’s ‘representative’ and ‘reference’ genome classes were used to select the most appropriate assembly for downstream analyses. Taxonomy was obtained from NCBI taxon IDs using the R package Taxonomizr. Where a given species had between five and ten genome assemblies derived from different individuals available, all assemblies were downloaded and used to assess within-species variability in the model predictions. Genome completeness was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO; version 5.2.2) using Augustus gene prediction. Gene promoter sequences for human, chicken and zebrafish were downloaded from the Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD) using the EPDnew selection tool to use as reference sequences40,41. For each gene, the region ± 100 nucleotides surrounding the TSS of the most representative gene promoter was extracted. This region was selected as it most likely encompasses the core promoter, the sequence immediately surrounding the TSS that functions in controlling the activity of RNA polymerase II, and therefore gene transcription42 and has demonstrated superior performance in our previous work11. To retrieve orthologous promoter sequences from each vertebrate genome, BLAST+ (version 2.12.0) was first used to create a database for each genome. Following this, the EPD promoter sequences were used to query each genome database specifying a minimum sequence identity of 70% according to their model groups (i.e., chicken promoters for the reptile model, human promoters for the mammal-specific and all-vertebrate models and zebrafish promoters for the fish model). The single top hit for each promoter in each species was used to calculate CpG content. At present, there are no experimentally derived promoter sequences available for an amphibian species on the EPD.

Measurement of CpG content

The observed/expected ratio of CpGs in gene promoter regions was used as a measure of normalised CpG density. CpG O/E was first developed by Gardiner-Garden and Frommer17 to identify genomic regions with higher-than-expected densities of CpG sites, known as CpG islands. CpG O/E is calculated by first obtaining the CpG content [i.e., the total number of CpG dinucleotides (CpG) divided by the sequence length (N)] and dividing it by the expected CpG content, or the C density [i.e., total number of cytosines (C) divided by N] multiplied by the G density [i.e., total number of guanines (G) divided by N]. Using this equation, values for CpG O/E were calculated for each promoter sequence in each species.

Model development and validation

To predict age at maturity from promoter CpG O/E, elastic net regression models were developed using 10-fold nested cross-validation implemented in R version 4.4.043. A total of four models were developed, one for all vertebrate species, and one for each of the three designated groups: reptiles, mammals, and fish. The models use promoter CpG O/E, species order and genomic GC proportion to predict species age at maturity. Known ages at maturity for all vertebrates with promoter sequence data available were natural log transformed to enable linear modelling. Based on the percentiles of the transformed age at maturity values and species order, the data was split into 70% training, 15% validation and 15% testing. The training and validation data were filtered to remove promoters with <10% coverage across all species to reduce overfitting and enhance feature selection. The remaining missing values (indicating no matching promoter sequence was obtained during BLAST searches) were imputed as zero to enable elastic net regression. Consequently, modelled CpG densities of zero largely reflect promoter absence. Species order was transformed from categorical to numeric using one hot-encoding (i.e., adding dummy variables) and along with genomic GC proportion, were added to the CpG O/E data to create a feature matrix. All training and validation data were standardised using z-score normalisation prior to elastic net regression. For each model, the training and validation split was performed 10 times to create 10 outer cross-validation folds, while the test set was fixed.

Within each of the 10 outer folds, the elastic net regression is performed with 10-fold inner cross-validation using the glmnet44 and glmnetUtils45 packages to determine the optimal values for alpha and lambda (hyperparameter optimisation). Using the minimum value of alpha, the model was fit to the training data for 100 values of lambda. The model was then used to predict age at maturity for the training and validation data, specifying the optimal lambda.1se (lambda “one standard error”: the largest value of lambda within one standard error of the minimum lambda value) from the previous cross-validation step. To detect signs of overfitting, Pearson correlation coefficients between known and predicted ages at maturity were calculated and the model absolute errors (i.e., the residuals) were compared between the training and validation datasets using a Student’s two-sided unpaired t-test. To avoid potential overfitting of the final ensemble models, we retained only those models for which the difference between the two means was not significant. Using the parameters from the remaining models, the models were re-fit to the combined training and validation dataset and the results were then bagged to improve prediction accuracy46. During all model development steps, the training (including training and validation) data was processed in isolation from the test data set to avoid data leakage and ensure that the model’s performance evaluation (on the test dataset) reflects its ability to generalise to new, unseen data. To explore the potential of developing a measure of age at maturity that is more readily comparable across species, we repeated the model development process for relative age at maturity (i.e., the ratio between age at maturity and species' maximum lifespan). Where lifespan data were unavailable, it was imputed using the mean of the closest available taxonomic rank. A model information sheet for detecting and preventing data leakage is provided in the supplementary material47,48.

Prediction intervals

Age at maturity prediction intervals were estimated using the open-source Python package model agnostic prediction interval estimator (MAPIE)49. Using the hyperparameters optimised with glmnet in R (see the section “Model development and validation”), the elastic net regression was rerun in Python on the combined training and validation data set to generate age-at-maturity predictions with the corresponding prediction intervals using MAPIE. As per the workflow in R, z-score normalisation was applied to the age at maturity values as well as all features (including promoter CpG densities, genomic GC content and one-hot-encoded species order) on the training and validation data separately to the test data, to prevent leakage. We explored three methods to estimate prediction intervals offered in the MAPIE package, namely mean and standard deviation (naive), jackknife + ab50 and cross-validation (reviewed in Yong and Ong51). These methods were selected as they are less compute-intensive compared to other methods (e.g., jackknife)52. The resulting prediction intervals were bagged using the same method as the predictions, i.e., by taking the median value of all models passing our overfitting test. The performance of the prediction intervals on the test data was assessed using coverage (as PICP) and width (as MPIW)53. Where coverage should be close to the nominal confidence level (here, 90%) and narrow widths indicate higher certainty.

Age at maturity predictions

The optimised age-at-maturity predictor was applied to species either absent from our age-at-maturity database or otherwise unseen by the model during development (unknown age-at-maturity predictions, test data, or those assemblies used for within-species variability analyses). Promoter sequence retrieval, measurement of CpG content and feature matrix generation were carried out as described above, with some exceptions for pre-processing steps necessary to avoid data leakage. Specifically, we filtered the promoter data for unseen samples based on those promoters present in the training data matrix. We also added one-hot-encoded variables for species order that were present in the training data but missing from the unseen data. Additionally, target (age at maturity) and feature variables (promoter CpG content, GC proportion, species order) for the unseen observations were standardised based on metrics from the training data. Following these pre-processing steps, age at maturity values were predicted using the four ensemble models (all-vertebrate, fish-specific, mammal-specific and reptile-specific). Predictions of age at maturity for species for which data were previously unavailable were generated using only the group-specific models, as their performance was typically superior. Species were assigned to IUCN red list categories based on data provided by iucnredlist.org (accessed 05/08/2023). Any species not listed were assigned to the category ‘Not Evaluated’.

Final model evaluation

To assess the performance of the ensemble models, Pearson correlations between known and predicted ages at maturity were calculated for each of the four ensembles and within the all-vertebrate model for each of the four groups (amphibians, fish, mammals and reptiles). Prediction error was assessed in the same manner, using RMSE as well as median and percentage absolute error in years. Correlations and calculations of prediction error were performed separately for the training (including training and validation) and testing data. Prediction error was correlated against the number of BLAST hits, mean hit length, mean hit identity and BUSCO genome completeness score to assess the effects of similarity to reference sequences and assembly completeness on the final predictions.

Promoter analyses

For each ensemble, promoters most strongly associated with age at maturity were identified by filtering for those that (1) were selected for during cross-validation in all of the bagged models; (2) had significant Pearson correlations with age at maturity and (3) ranked in the top five for highest mean modelled weight. Gene IDs for these promoters were retrieved from the EPD and further investigated using gene summary and expression information from ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/ (accessed 06/02/2023). We also compared significantly correlated gene promoters that were selected in at least 50% of the bagged models with those genes whose DNA methylation was recently associated with age at maturity in mammals18. For functional enrichment analysis, we also selected promoters based on significant Pearson correlations with age at maturity, but here included promoters that were predictive in any of the bagged models. The mean weight for each promoter across the ensemble was used to categorise that promoter as negatively or positively associated with age at maturity, and those with inconsistent relationships (e.g., positively associated in the ensemble but negatively associated in the Pearson correlation) were removed. These categories were used to perform gene ontology (GO) enrichment with gprofiler254 using ordered queries (based on the average coefficient values) to produce GSEA style p-values. Gene IDs were obtained from the EPD and the reference species was specified as either human, chicken or zebrafish.

Statistics and reproducibility

All analyses were performed using R43 (version 4.4.0) and Python (version 3.12.0). Statistical comparisons between groups were carried out using Student’s two-sided t-test unless otherwise stated. Non-normal data were log-transformed using the base R function log and variance tests were applied using the stats package function var.test before each t-test was carried out using t.test. Means were calculated using the base R mean function and medians using the median function from the stats package. All plots were drawn using ggplot255 (version 3.5.1) and tree figures using ggtree56 (version 3.12.0) and ggtreeExtra57 (version 1.14.0). Correlation coefficients, coefficients of determination and their associated p-values were estimated using the stat_cor function from ggpubr, specifying the method as Pearson. Violin plots, including inner box plots, were plotted using functions geom_violin and geom_boxplot and sina points were drawn using the ggforce (version 0.4.2) function geom_sina. The centre line of the box plots indicates the median and whiskers are extended to the third quartile + 1.5 × IQR (interquartile range) and the first quartile − 1.5 × IQR. General data manipulation and processing analyses were performed using tidyverse58 packages dplyr (version 1.1.4), purrr (version 1.0.2), stringr (version 1.5.1), tibble (version 3.2.1) and tidyr (version 1.3.1). To create predictive models, data were partitioned using the createDataPartition from the caret59 package as described in the text. The random seed was set to 1234 to enable reproducibility. The glmnetUtils45 function cva.glmnet was used to optimise alpha and lambda. The glmnet function was used to generate the models, where both features and target variables were scaled using z-score normalisation prior to modelling and standardise was set to false. Total sample sizes were determined based on the amount of publicly available data and are given in the results. Additional data manipulation and analyses to perform uncertainty estimation were conducted using the Python packages MAPIE49 (version 0.7.0), NumPy60 (version 1.26.2), pandas61 (version 2.1.3), SciPy62 (version 1.11.3), and scikit-learn63 (version 1.3.2).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

All code is available on GitHub (version 1.0)64. For uncertainty estimation, the code is additionally available on BitBucket (version 0.0.1).

References

Hoffmann, M. et al. The impact of conservation on the status of the world’s vertebrates. Science (1979) 330, 1503–1509 (2010).

Wilder, A. P. et al. The contribution of historical processes to contemporary extinction risk in placental mammals. Science (1979) 380, eabn5856 (2023).

Hutchings, J. A., Myers, R. A., García, V. B., Lucifora, L. O. & Kuparinen, A. Life-history correlates of extinction risk and recovery potential. Ecol. Appl. 22, 1061–1067 (2012).

Reynolds, J. D., Dulvy, N. K., Goodwin, N. B. & Hutchings, J. A. Biology of extinction risk in marine fishes. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 272, 2337–2344 (2005).

Oli, M. K. & Dobson, F. S. The relative importance of life‐history variables to population growth rate in Mammals: Cole’s prediction revisited. Am. Nat. 161, 422–440 (2003).

Healy, K., Ezard, T. H. G., Jones, O. R., Salguero-Gómez, R. & Buckley, Y. M. Animal life history is shaped by the pace of life and the distribution of age-specific mortality and reproduction. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1217–1224 (2019).

Rogers, T. D., Cambiè, G. & Kaiser, M. J. Determination of size, sex and maturity stage of free swimming catsharks using laser photogrammetry. Mar. Biol. 164, 213 (2017).

Levasseur, K. E., Stapleton, S. P. & Quattro, J. M. Precise natal homing and an estimate of age at sexual maturity in hawksbill turtles. Anim. Conserv. 24, 523–535 (2021).

Valenzuela-Molina, M., Atkinson, S., Mashburn, K., Gendron, D. & Brownell, R. L. Fecal steroid hormones reveal reproductive state in female blue whales sampled in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 261, 127–135 (2018).

Heydenrych, M. J., Budd, A. M., Mayne, B. & Jarman, S. A genomic predictor for age at sexual maturity for mammalian species. Evol. Appl. 17, e13635 (2024).

Budd, A. M., Mayne, B., Berry, O. & Jarman, S. Fish species lifespan prediction from promoter cytosine-phosphate-guanine density. Mol. Ecol. Resour. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.13774, 1–14 (2023).

Mayne, B., Berry, O. & Jarman, S. Redefining life expectancy and maximum lifespan for wildlife management. Austral Ecol. 45, 855–857 (2020).

McLain, A. T. & Faulk, C. The evolution of CpG density and lifespan in conserved primate and mammalian promoters. Aging (Albany, NY) 10, 561 (2018).

Weber, M. et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 39, 457–466 (2007).

Saxonov, S., Berg, P. & Brutlag, D. L. A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 1412–1417 (2006).

Tian, H., He, Y., Xue, Y. & Gao, Y. Q. Expression regulation of genes is linked to their CpG density distributions around transcription start sites. Life Sci. Alliance 5, e202101302 (2022).

Gardiner-Garden, M. & Frommer, M. CpG Islands in vertebrate genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 196, 261–282 (1987).

Li, C. Z. et al. Epigenetic predictors of species maximum life span and other life-history traits in mammals. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm7273 (2024).

Bergeron, L. A. et al. Evolution of the germline mutation rate across vertebrates. Nature 615, 285–291 (2023).

Herculano-Houzel, S. Longevity and sexual maturity vary across species with number of cortical neurons, and humans are no exception. J. Comp. Neurol. 527, 1689–1705 (2019).

de Magalhães, J. P., Costa, J. & Church, G. M. An analysis of the relationship between metabolism, developmental schedules, and longevity using phylogenetic independent contrasts. J. Gerontology: Ser. A 62, 149–160 (2007).

Aylwin, C. F., Toro, C. A., Shirtcliff, E. & Lomniczi, A. Emerging genetic and epigenetic mechanisms underlying pubertal maturation in adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 29, 54–79 (2019).

Li, C. et al. MKRN3 regulates the epigenetic switch of mammalian puberty via ubiquitination of MBD3. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 671–685 (2020).

Ball, G. F. & Wade, J. The value of comparative approaches to our understanding of puberty as illustrated by investigations in birds and reptiles. Horm. Behav. 64, 211–214 (2013).

MacLean, J. A. et al. Rhox: a new homeobox gene cluster. Cell 120, 369–382 (2005).

Yang, N. et al. A hyper-quiescent chromatin state formed during aging is reversed by regeneration. Mol. Cell 83, 1659–1676.e11 (2023).

Choi, Y., Ballow, D. J., Xin, Y. & Rajkovic, A. Lim homeobox gene, Lhx8, is essential for mouse oocyte differentiation and survival1. Biol. Reprod. 79, 442–449 (2008).

Fan, G. et al. Initial data release and announcement of the 10,000 Fish Genomes Project (Fish10K). Gigascience 9, giaa080 (2020).

Lewin, H. A. et al. The Earth BioGenome Project 2020: starting the clock. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115635118 (2022).

Dennis, B., Munholland, P. L. & Scott, J. M. Estimation of growth and extinction parameters for endangered species. Ecol. Monogr. 61, 115–143 (1991).

Reid, J. M., Bignal, E. M., Bignal, S., McCracken, D. I. & Monaghan, P. Identifying the demographic determinants of population growth rate: a case study of red-billed choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax. J. Anim. Ecol. 73, 777–788 (2004).

Jones, O. R. et al. Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Nature 505, 169–173 (2014).

Staerk, J. et al. Performance of generation time approximations for extinction risk assessments. J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 1436–1446 (2019).

Supple, M. A. & Shapiro, B. Conservation of biodiversity in the genomics era. Genome Biol. 19, 131 (2018).

Theissinger, K. et al. How genomics can help biodiversity conservation. Trends Genet. 39, 545–559 (2023).

Mayne, B., Berry, O., Davies, C., Farley, J. & Jarman, S. A genomic predictor of lifespan in vertebrates. Sci. Rep. 9, 17866 (2019).

De Magalhães, J. P. & Costa, J. A database of vertebrate longevity records and their relation to other life-history traits. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1770–1774 (2009).

Myhrvold, N. P. et al. An amniote life-history database to perform comparative analyses with birds, mammals, and reptiles. Ecology 96, 3109 (2015).

Jones, K. E. et al. PanTHERIA: a species-level database of life history, ecology, and geography of extant and recently extinct mammals. Ecology 90, 2648 (2009).

Périer, R. C., Praz, V., Junier, T., Bonnard, C. & Bucher, P. The Eukaryotic Promoter Database (EPD). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 302–303 (2000).

Dreos, R., Ambrosini, G., Périer, R. C. & Bucher, P. The Eukaryotic Promoter Database: expansion of EPDnew and new promoter analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D92–D96 (2015).

Lenhard, B., Sandelin, A. & Carninci, P. Metazoan promoters: emerging characteristics and insights into transcriptional regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 233–245 (2012).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, 2013).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softw. 33, 1 (2010).

Ooi, H. glmnetUtils: utilities for’Glmnet’. R package version 1.1. 5. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnetUtils/glmnetUtils.pdf (2020).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 24, 123–140 (1996).

Stock, A., Gregr, E. J. & Chan, K. M. A. Data leakage jeopardizes ecological applications of machine learning. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1743–1745 (2023).

Kapoor, S. & Narayanan, A. Leakage and the reproducibility crisis in machine-learning-based science. Patterns 4, 100804 (2023).

Taquet, V., Blot, V., Morzadec, T., Lacombe, L. & Brunel, N. MAPIE: an open-source library for distribution-free uncertainty quantification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12274 (2022).

Kim, B., Xu, C. & Barber, R. Predictive inference is free with the jackknife+-after-bootstrap. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 4138–4149 (2020).

Yong, S. Y. & Ong, C. S. Uncertainty quantification of the virial black hole mass with conformal prediction. Mon. Not. R. Astron Soc. 524, 3116–3129 (2023).

Quenouille, M. H. Problems in plane sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 20, 355–375 (1949).

Khosravi, A., Nahavandi, S. & Creighton, D. Construction of optimal prediction intervals for load forecasting problems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 25, 1496–1503 (2010).

Kolberg, L., Raudvere, U., Kuzmin, I., Vilo, J. & Peterson, H. gprofiler2—an R package for gene list functional enrichment analysis and namespace conversion toolset g: Profiler. F1000Res 9, ELIXIR–709 (2020).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 3, 180–185 (2011).

Yu, G., Smith, D. K., Zhu, H., Guan, Y. & Lam, T. T.-Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 28–36 (2017).

Xu, S. et al. ggtreeExtra: compact visualization of richly annotated phylogenetic data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4039–4042 (2021).

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Kuhn, M. et al. Package ‘caret’. R. J. 223, 7 (2020).

Harris et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. SciPy 445, 51–56 (2010).

Virtanen, P. et al. Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python and SciPy 1.0 contributors. SciPy 1.0. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Budd, A. M. & Yong, S. Y. Code and Data for ‘Universal Prediction of Vertebrate Species Age at Maturity’ https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13637779 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the CSIRO Environomics Future Science Platform. The authors would like to thank members of the epigenetics discussion group for their helpful feedback on the manuscript, including Livia Gerber, Yi Jin Liew and Sam Andrew. Special thanks to Clare Holleley for additionally reviewing the manuscript. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the immense effort from all those who were involved in the creation, submission and curation of publicly available data that enabled this work to be carried out.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alyssa Budd: Data curation (lead), formal analysis (lead), investigation (lead), methodology (lead), project administration (equal), validation (lead), visualisation (lead), writing—original draft preparation (lead), writing—review and editing (lead). Suk Yee Yong: Formal analysis (supporting), methodology (supporting), validation (supporting), visualisation (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). Matthew Heydenrych: Methodology (supporting), validation (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). Benjamin Mayne: Conceptualisation (supporting), methodology (supporting), validation (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). Oliver Berry: Conceptualisation (supporting), funding acquisition (lead), project administration (equal), resources (lead), supervision (equal), writing—review and editing (supporting). Simon Jarman: Conceptualisation (lead), methodology (supporting), supervision (equal), writing—review and editing (supporting).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Christopher Faulk and Philipp Antczak for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Aylin Bircan and Christina Karlsson Rosenthal. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Budd, A.M., Yong, S.Y., Heydenrych, M.J. et al. Universal prediction of vertebrate species age at maturity. Commun Biol 7, 1414 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07046-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07046-z