Abstract

Agricultural practices affect soil microbes which are critical to soil health and sustainable agriculture. To understand prokaryotic and fungal assembly under agricultural practices, we use machine learning-based methods. We show that fertility source is the most pronounced factor for microbial assembly especially for fungi, and its effect decreases with soil depths. Fertility source also shapes microbial co-occurrence patterns revealed by machine learning, leading to fungi-dominated modules sensitive to fertility down to 30 cm depth. Tillage affects soil microbiomes at 0-20 cm depth, enhancing dispersal and stochastic processes but potentially jeopardizing microbial interactions. Cover crop effects are less pronounced and lack depth-dependent patterns. Machine learning reveals that the impact of agricultural practices on microbial communities is multifaceted and highlights the role of fertility source over the soil depth. Machine learning overcomes the linear limitations of traditional methods and offers enhanced insights into the mechanisms underlying microbial assembly and distributions in agriculture soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As new technologies emerge that enable the identification of microbial structure and function, soil microbiomes increasingly are explored for their contribution to crop yields and potential for advancing the sustainability of agriculture1. The microbial communities in soils can serve several important economic and ecologic functions, such as enhancing the bioavailability of important nutrients for plants, synthesize hormones that promote crop growth, and boost plant resilience against stresses2,3,4. Thus, knowledge about agricultural soil microorganisms and their interactions among each other and with plants is increasingly sought after for use in new biofertilizer products5. Further, this knowledge can be used to better retain or recruit microbial taxa already present in the soil and support their beneficial functions through agricultural management decisions.

Agricultural management practices like tillage, fertilizers, and cover crops influence the population structure and functional traits of soil microbiomes, yet the complete impact of these factors is not fully understood3,6,7. Recent studies have increasingly concentrated on elucidating how these practices shape microbial communities within the soil7,8. While the deterministic processes captured in part by environmental variables often point to a strong influence of environmental selection on microbial community assembly, stochastic processes may be more influential than previously thought, especially in late soil ecological succession9. Gaining a more comprehensive understanding of how agricultural methods impact soil microbial communities is pivotal for maximizing soil functionality within agricultural ecosystems10.

The relative abundance and composition of microbial taxa found in the soil varies considerably depending on the soil properties and environmental conditions11. Because of its complexity and immense diversity, soil microbiomes remain challenging to interpret. Traditional multivariate statistical methods such as Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) and Redundancy Analysis (RDA) are staples for analyzing soil microbiomes12,13. However, these methods have limitations because they assume that the species’ response to environmental factors is either linear or unimodal. Consequently, the ordination axes and clusters generated by traditional ordination methods may lack ecological relevance for complex ecological data14,15. Furthermore, the absence of interaction terms in linear models prevents them from capturing non-additive effects among environmental factors when study species–environment interactions14. Recently, by harnessing the power of artificial intelligence, researchers are using machine learning (ML) models for analyzing microbiome constituents and their links to environmental conditions16 by enhancing predictive power at the cost of reduced model interpretability17. Various methods recently have been proposed18,19 to interpret the predictions of complex models such as the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) framework, which is currently used in microbiome research20,21.

In addition to responding to environmental gradients (abiotic factors), members of the soil microbiome interact with each other, and these interactions (biotic factors) are essential to ecosystem dynamics. Co-occurrence networks, increasingly used for this purpose, often pose complex interpretation challenges. Traditional topological analysis of these networks can result in ambiguous biological implications and may fail to capture higher-order interactions8,22,23,24. This challenge can be addressed by integrating co-occurrence network analysis with ML models. By aggregating the contributions of individual taxa to the predictions of the relative abundance of other species, this approach quantifies the impact of individual microorganisms on module formation. Recent work has demonstrated the ability of ML to predict microbial composition and revealed putative interaction mechanisms25,26,27. It is worth noting that stochastic processes, which might not be represented by an ML model, also influence how microbial communities are shaped28,29. To account for this, a neutral community model (NCM) can be included and its outcomes can be juxtaposed with those from an ML analysis. Nevertheless, ML models with explanatory frameworks offer promising prospects as new tools to improve the understanding of microbiome interactions, but to date, ML approaches are rarely applied to soil microbiomes.

In this study, we explored microbial assembly, distribution, and networks across depths under different farming practices in one of the oldest organic field trials in North America (FST, Farming Systems Trial, established at the Rodale Institute in 1981). Prior work has demonstrated a strong soil depth signal of microbial community composition with less influence from fertility source, tillage intensity, and cover crop use, and these conclusions, which were drawn from linear approaches, may overlook important patterns30. Here we asked: (1) which abiotic and management components of agricultural systems most strongly affect the assembly of microbial communities in agricultural soils and how can machine learning facilitate this interpretation? and (2) to what extent does the soil microbiome carry a signal that can indicate different agricultural practices? To achieve this, we evaluated the contribution of agricultural management and environmental parameters to explain the variations in prokaryotic (bacteria and archaea) and fungal communities using our newly proposed ML-based canonical analysis. We also applied Random Forest (RF)31 to decipher the microbial distribution and trends under agricultural practices and used SHAP to identify primary biomarkers associated with agricultural practices.

Results

Environment influences microbial assembly

We compared variances between PCoA and t-SNE (t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding)-based ordination methods. In contrast to traditional multivariate PCoA, t-SNE-based ordination methods better captured explained variances in both prokaryote and fungal soil communities, as shown in Shepard diagrams (Supplementary Fig. S1). For the prokaryotic community, PCoA captured significant variations and was on par with t-SNE in terms of explained variance, but it lagged in locality preservation. Conversely, for the fungal community, PCoA performed poorly on both explained variance and degree of locality preservation metrics, but t-SNE was able to recover the community’s nonlinear structure.

The t-SNE plots revealed different patterns of soil microbial communities (Fig. 1a): t-SNE component 1 values represented a gradient of sample depth for both soil prokaryotes and fungi, and t-SNE component 2 separated the fungal samples by fertility sources. Mapped analysis of t-SNE plot indicated that environmental factors and agricultural practices can explain the major variations of ordination coordinates (prokaryote 79.1%, fungi 72.6%) (Fig. 1a). The relative contributions to explaining variations in microbial community composition indicated that fertility source, organic matter, depth, gravimetric water content, bulk density, C:N ratio, total carbon, total nitrogen, and total hydrogen had a significant impact on both prokaryotic and fungal community composition (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b). Fertility source was the dominant factor responsible for fungal community variations, while soil depth and organic matter were the main factors responsible for community variations of prokaryotes. Tillage only significantly affected prokaryotic communities, while cover crops only impacted fungal communities but both factors had low feature importance.

a Separate t-SNE ordinations using Bray–Curtis distance are performed for prokaryotes and fungi. b Feature importance of environmental factors and agricultural practices explain the variations within the prokaryotic and fungal communities, respectively. The x-axis represents the average of SHAP values, reflecting the influence of each feature on the prediction of ordination. Features with SHAP values significantly higher than random variables are marked in khaki (p < 0.05 by t-test, n = 95 soil samples), signaling substantial impact on the community structure.

Tillage enhances stochastic processes in microbial community assembly at shallow depth

The importance of neutral processes in soil microbial communities across depth was evaluated by the NCM, which captured a significant portion of the relationship between microbial taxa as represented by amplicon sequence variants’ (ASV) occurrence frequency and their relative abundance, explaining 83% and 76.5% of the community variance for prokaryotes and fungi, respectively (Fig. 2). The NCM model for microbial communities at each depth category revealed that the immigration rate m (calculated as the probability that an immigrating cell will replace a dead cell) for prokaryotes was significantly higher than for fungi (Table 1). Additionally, the immigration rates for both prokaryotes and fungi changed with soil depth and were higher within the top 0–20 cm and decreased with depth. Overall, microbial dispersal was more pronounced in the shallow soil (0–20 cm) and diminished as the soil depth increased (20–60 cm). The highest estimate of inter-community dispersal nm and overall fit of the NCM model R2 indicates stochastic processes caused by migration dominate microbial community assembly at 10–20 cm. Further, NCM results in tilled soils, especially in the top 20 cm, showed higher m values and R2 coefficients than reduced-till soils (Supplementary Table S1).

The predicted occurrence frequencies for prokaryotic and fungal communities across all depths. Solid yellow lines mark the optimal NCM fit, while dashed lines denote the 95% confidence intervals. ASVs deviating from NCM predictions (black) are color-coded differently (blue or red). Nm indicates the metacommunity size multiplied by immigration, and Rsqr (R2) indicates model fitness.

Effect of abiotic and biotic factors on microbial community structure

RF models, which were based on abiotic factors (environmental factors and agricultural practices) and biotic factors (microbial interactions, represented by abundance of other ASVs beyond the target taxa), displayed varied performance in predicting the abundance of common ASVs (defined in the section “Dataset description and preprocessing”) at different soil depths (Table 2). Overall, biotic factors accounted for a greater degree of variations in the relative abundance of prokaryotes and fungi compared to abiotic factors. As depth increased, the overall quantity of predictable ASVs decreased. However, for prokaryotic ASVs between 10–20 cm, the portion predictable by biotic factors was lower than that of 20–30 cm, while the predictable portion by abiotic factors was higher than that of 0–10 cm. Predictions based on biotic factors were significantly more accurate than those based on abiotic factors. In 30–60 cm, the portion of both prokaryotic and fungal communities predictable by biotic factors was much lower than those in 0–30 cm. Furthermore, the relative abundance of prokaryotes across soil depths remained more predictable than that of fungi.

Co-occurrence network properties at different depths

The co-occurrence networks in different soil depths exhibited great heterogeneity: 36.7% of the nodes and 2.06% of the edges were present in more than one network (Fig. 3). The topological properties were highly variable between the networks from different depths (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, the network within the 30–60 cm depth range exhibited the highest average degree (7.85) and edge density (0.00664), which quantify the overall connectivity of a network. Additionally, this depth had the highest average clustering coefficient (0.706), emphasizing the compactness of local structures. These results all indicated that microbes were the most closely associated and correlated in 30–60 cm. In contrast, the numbers of nodes and edges of the network in 10–20 cm were markedly lower than those in other soil depths.

Variations of edge density were explained well by depth (R2 = 0.959, p = 0.020), and with the increase of soil depth, the co-occurrence proportion of the microbial community gradually increased. The variations of bacteria to bacteria edges and fungi to fungi edges could also be explained well by depth (bacteria to bacteria: R2 = 0.971, p = 0.014, fungi to fungi: R2 = 0.980, p = 0.010, Supplementary Table S3). Across all soil depths, bacteria to bacteria connections dominated the soil microbiome co-occurrence networks.

Effect of fertility source and cover crop on microbial co-occurrence patterns

Agricultural practice-sensitive ASVs exhibited distinct distribution patterns in co-occurrence networks at different depths (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S4). Tillage-sensitive ASVs were mostly concentrated in the top 20 cm soil depth (Fig. 3a, b). Fertility source- and cover crop-sensitive ASVs existed across depths, while fertility source-sensitive ASVs were mainly concentrated at in the top 30 cm (Fig. 3a–c), and cover crop-sensitive ASVs were mainly found at 30–60 cm depth.

The degree (number of connections) distribution of sensitive ASVs to different agriculture practices in the co-occurrence network also showed differences (Supplementary Table S5). We established the average degree of all ASVs at each depth as a benchmark. Compared to this benchmark, fertility source- and cover crop-sensitive ASVs exhibited higher average degrees at all depths, suggesting these practices significantly enhance microbial co-occurrences. In contrast, tillage-sensitive ASVs had lower average degrees, potentially indicating fewer associations and less impact of tillage on microbial co-occurrence patterns.

A synthetic fertilizer module and a legume module that contained the highest proportions (>25%) of agriculture practice-sensitive ASVs were identified at 0–10, 10–20, and 20–30 cm soils by using optimization of modularity algorithm (Fig. 4). The synthetic fertilizer modules and legume modules contained ASVs sensitive to the corresponding fertility sources, and these ASVs did not overlap. Manure was excluded because no manure module was identified across soil depths but some manure-sensitive ASVs were found in the legume module. These observations were further supported by the cumulative relative abundance (sum of relative abundances of ASVs in the module) of synthetic fertilizer module and legume module, which differed significantly among the fertility sources (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). The ASVs in the synthetic fertilizer module were enriched when the fertility source was synthetic fertilizer, and the ASVs in the legume module were enriched when the fertility sources were legume or manure.

Fungi dominated the hub taxa in fertility source modules

Based on the RF model, a large fraction of ASVs in fertility modules can be mutually predicted using their relative abundance, with predictable proportions ranging from 69.9% to 86.3%. In contrast, the predictive capacity based on abiotic factors remained limited, ranging from 6.4% to 38.6% (Supplementary Table S6). In general, the predictability from both biotic and abiotic factors was lower in the deeper layer (20–30 cm) than at the surface (0–10 cm).

The SHAP-based framework was used to identify the ASVs that have the greatest impact on other ASVs in the module and the top ten percent of these ASVs were defined as hub taxa. Most ASVs identified as hub taxa were fungi (Supplementary Fig. S4, Supplementary Data 1). Based on the model retrained on hub taxa, over half of ASVs in all fertility-sensitive modules were predictable (ranging from 50.0% to 71.9%) (Supplementary Table S6).

Structural redundancy analysis was used to evaluate the performance of hub taxa identified by the SHAP-based framework and those identified by traditional network topology analysis, specifically comparing their consistency of response pattern to the module. Results from structural redundancy analysis indicated that hub taxa identified by SHAP-based framework have strong consistency with the complete set of taxa within the modules given that the correlation with sample similarities ranged from 0.916 to 0.979 (Supplementary Table S7). This suggested that the response patterns of hub taxa identified by the SHAP-based framework closely matched those of the corresponding fertility source module. In contrast, traditional hub taxa failed to achieve the similar performance, with their correlations ranging from 0.746 to 0.925 (Supplementary Table S7).

In the legume module, archaea and bacteria were also identified as hub ASVs (Supplementary Data 1). Archaea (families Nitrosotaleaceae and Nitrososphaeraceae) occurred in soil depth sections 0–10 cm and 20–30 cm while Bacteria (order Chthoniobacteraceae from phylum Verrucomicrobiota and phylum Planctomycetota WD2101 soil group) were present only from 20–30 cm. Similarly, bacterial hub species (mainly from phyla Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobiota, Myxococcota, and Firmicutes) were also identified in the synthetic fertilizer module at 0–10 cm and 20–30 cm. Only one Archaeon (order Woesearchaeales) occurred at the deeper layer (20–30 cm). Compared to the legume module with no Bacteria in the 0–10 cm soil, the synthetic fertilizer module contained eleven Bacteria hub ASVs at 0–10 cm (Supplementary Table S7).

Identification of indicator microbial taxa under agricultural practices by machine learning

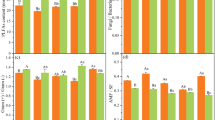

To determine whether each separate agricultural practice could be identified by microbial taxa, we examined the AUC scores. Based on AUC scores, ASVs from all depths (0–10, 10–20, 20–30, and 30–60 cm) contained the power to differentiate fertility sources, but the predictive power decreased quickly after 20 cm depth (Fig. 5). AUC scores were the highest in surface soil (0–10 cm) under fertility sources with an average AUC score of 0.968 for prokaryotes and 0.996 for fungi (Fig. 5). In contrast, only the microbial community taxa at 0–20 cm soil depth indicated different tillage strategies (Fig. 5). The prediction from cover crop type was limited and of lower accuracy, however, AUC scores for prokaryotes and fungi were higher than 0.5 at 0–10 and 10–20 cm (Fig. 5). Thus, we selected 0–60 cm as the depth section where the model could identify different fertility sources and 0–20 cm as the depth section where the model could identify different tillage and cover cropping impacts.

The results are computed through a ten-fold cross-validation, conducted 10 times. Below the dotted line (score ≤ 0.5) means that the model has no ability to identify agricultural practices. Values with a mean below 0.5 are plotted at 0.5, indicating a complete lack of recognition. The center of each data point represents the mean value, while the error bars are indicative of the standard deviation from the mean.

Specific biomarkers indicative of agricultural practices were then identified by a SHAP-based feature selection approach. Based on these biomarkers, the model’s proficiency was enhanced in recognizing the fertility source, tillage type, and cover crop. Fertility sources were identified with high accuracy for prokaryotes and fungi in 0–60 cm (AUC = 0.905 for prokaryotes and 0.960 for fungi). The AUC scores for tillage also improved for both prokaryotes and fungi (0.896 and 0.917) at 0–20 cm as well as cover cropping (0.778 and 0.750).

The top 50 biomarkers that contributed the most to distinguishing agricultural practices were identified as primary biomarkers (Supplementary Fig. S5). For fertility sources, organic-enriched fungi predominantly exhibited as biomarkers, while the biomarkers for prokaryotes were more evenly distributed among fertility sources (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S5a, b). Primary fungal biomarkers for fertility sources in the 0–60 cm soil depth more often had higher normalized relative abundances associated with legume and manure fertility sources. These included ASVs in the family Nectriaceae (four ASVs), Chaetomiaceae (five ASVs) and Pyronemataceae (three ASVs). ASVs contributing the most to distinguishing among fertility sources were from families Chaetomiaceae, Corynesporascaceae, Hypocreales, Magnaporthaceae, Nectriaceae, and Orbiliaceae and, except for Corynesporascaceae, were enriched in organic fertility sources (Fig. 6). Compared to fungi, prokaryotic biomarkers were more evenly distributed across fertility sources and contained higher normalized relative abundances associated with synthetic fertilizer. Prokaryotic biomarkers of fertility sources in 0–60 cm depth soil were primarily from families Microscillaceae (three ASVs), Nitrosomonadaceae, and Gemmatimonadaceae, (two ASVs each). An ASV in genus Nannocystis was particularly elevated in the legume fertility source and somewhat in the manure fertility source as compared with the synthetic fertilizer treatment (Fig. 6). In fields treated with manure, an ASV in genus Nitrospira was elevated compared with the other fertility sources. For the synthetically fertilized samples, an ASV in the genus Acidibacter was enriched relative to the legume fertility source.

RF models employed to discern tillage practices identified till-enriched taxa (both prokaryotes and fungi) as the primary biomarkers. Primary fungal and prokaryotic biomarkers that contributed the most to distinguishing between tillage types in 0–20 cm soils more often occurred in greater normalized relative abundances under full tillage (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. S5c, d). Primary biomarker ASVs most often occurred in fungal families Lasiosphaeriaceae (five ASVs), Didymellaceae and Nectriaceae (three ASVs each). Two ASVs in the family Didymellaceae were the strongest contributors and occurred at a higher relative abundance in fully tilled soils while ASVs in the family Nectriaceae were better biomarkers of reduced tillage. Prokaryotic families Nitrosomonadaceae (five ASVs), Gemmatimonadaceae and Roseiflexaceae (four ASVs each) were the most common biomarker families. ASVs in the family Nitrosomonadaceae marked both full and reduced tillage: genera MND1 and mle1-7 had greater abundances in full tillage while an unknown genus was elevated in reduced tillage. Three ASV biomarkers in the family Chitinophagaceae had higher relative abundances in full tillage (Fig. 7).

For cover crops, primary prokaryotic and fungal biomarkers of the 0–20 cm sample depth were almost evenly distributed between fields with and without cover crops (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. S5e, f). The primary contributions came from fungal families Bolbitiaceae and Herpotrichiellaceae, which marked soils with cover crops, and Helotiales, Dictyosporiaceae, and Tubeufiaceae which marked fields without cover crops. Primary prokaryotic contributors were from classes Dehalococcoidia, Acidimicrobiia, and Oligoflexia with families unknown, and family Rhizobiaceae. Of these, only the Oligoflexia ASV more strongly indicated fields without cover crops (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Microbial communities in agricultural soil are essential components of crop and soil health, yet interpreting these highly dimensional datasets has proved a challenge and can hinder conceptual and applied advances. The complexity of microbial community data necessitates the application of ML32, and researchers have used ML previously to predict soil health using microorganisms33. Here we enhance our understanding of which abiotic and management components of agricultural systems most strongly affect the assembly of microbial communities in agricultural soils and how can machine learning facilitate this interpretation. We found that ML approaches emphasize the influence of fertility source on fungal communities over soil depth, whereas soil depth is more important for prokaryote communities and was emphasized for both communities when using traditional approaches. Fertility source is also key for shaping microbial co-occurrence patterns, again, especially for fungi-dominated modules. Tillage is influential in surface soils and enhances dispersal and stochastic processes, whereas consequences from cover crops are minimal and only occur for fungal communities. We additionally identified that the soil microbiome caries a signal able to differentiate among agricultural practices using reliable biomarker microbial groups. Building on previous results30, these findings emphasize the ability of machine learning to move beyond traditional analysis constraints to reveal differences in driving factors in some cases and to support non-machine learning results in others.

Compared to traditional methods for the same data30, ML analysis revealed that fertility source was the most pronounced agricultural management factor for microbial assembly, especially for fungal communities, with its effect diminishing with depth. We hypothesize that the disparities between PCoA and t-SNE may be due to the linear association between soil depth and community variance that was strong in the prokaryotic community, whereas the major variance of the fungal community was caused by fertility sources, which are not easily described by a linear model. Consequently, information is lost when reducing the fungal community data to two dimensions using PCoA. During the environmental community modeling stage, according to the SHAP summary, organic matter was the most and second most influential environmental variable for the prokaryotic and fungal communities, respectively. As soil depth increases, organic matter proportions decline, making it a direct cause of significant changes in prokaryotic communities with depth at 0–60 cm. Depth-dependent differences in prokaryotic communities are not always identified30, but sample depth and organic matter have strong collinearity, and variables with strong collinearity can make it difficult to interpret in linear models34. This conclusion differs from that of another study35, which found that depth had a greater impact on bacterial communities than organic matter. We speculate that this discrepancy is due to the different sampling scales. The other study sampled from a depth range of 0–180 cm and observed significant differences between the bacterial communities in the 0–60 cm and 60–180 cm depth ranges35. This means that our conclusions from the 0–60 cm depth range, where changes in organic matter predominantly occurred36, may not be applicable to the 60–180 cm depth range.

Machine learning identified a different emphasis compared with traditional methods for the importance of management and abiotic factors in structuring the microbial community. In management practices, fertility source stands out as the most influential treatment factor for the microbial community, and especially as the most important factor for the fungal community, which was not identified in a previous study30. However, the influence is less pronounced for the prokaryotic community. A recent review identified that specific bacteria responded to inorganic and organic fertilizers differently, but fertilizers had no significant effect on overall richness and diversity37. In soils between 0–60 cm depth, we found tillage and cover crops exhibited minimal influence on the microbial community structure. Tillage only significantly affected prokaryotic communities, while cover crops impacted only fungal communities. This differed somewhat from patterns found with traditional permutational ANOVA where tillage type significantly influenced both prokaryotic and fungal communities but by less than 2%30. This analysis agreed though that the presence of cover crops mildly affected fungal community composition. In contrast with our findings, another long-term study established in 1970 of conventional and no-tillage systems with different fertility sources, found a stronger influence on microbial community structure from tillage than fertility sources (no fertilizer, N-only, or NPK38). This difference may lie in the fertility sources used because we found organic matter to be the primary environmental variable, but it was not included in their fertilizer treatments. One limitation is that our analysis modeled soil properties in conjunction with agricultural practices. Since agricultural practices, directly and indirectly, influence soil properties, this approach could potentially understate the significance of agricultural practices by omitting this relationship39.

In shallow soil (0–20 cm), both stochastic processes and community immigration rate are more pronounced than in deep soil (20–60 cm). This phenomenon can relate directly to tillage practices because soils typically are only tilled above 25 cm depth, resulting in greater microhabitat heterogeneity among microbial communities below this layer40. Soil tillage can disrupt physical and chemical soil structure41 and change soil moisture content and depth-associated environmental parameters which are influential for deterministic processes in community assembly42. Furthermore, the disturbance of soil macroaggregates and pore networks homogenizes ecological niches, thereby increasing the influence of stochastic processes on shaping microbial communities in shallow soil layers7,43. Consistent with previous studies, our results indicate that cultivation tends to amplify the influence of stochastic processes more in shaping prokaryotic communities than fungi43,44.

Tillage practices can mix soil layers and increase soil erosion potential and runoff45, thereby physically relocating microbes and enhancing their migration capabilities by reducing dispersal limitations. Within the tillage layer, prior research has found that tillage increased microbial dispersal and thus, the homogeneity of soil bacterial communities across microhabitats46. Further, wind and water flows are more likely to facilitate dispersal at shallow depths47,48 especially if agricultural soils are compacted and infiltrated poorly. Therefore, the hydrological connectivity inherent in shallow soil could be another key factor contributing to this enhanced dispersal ability28. Additionally, we found that prokaryotes have greater dispersal ability than fungi, which is consistent with previous work and attributed to their smaller dispersal limitations due to their smaller body and unicellular growth44,49,50. Dispersal limitation can intensify the priority effect in assembly44,51. This implies that species arriving earlier alter resources or conditions, affecting the establishment of subsequent species52. As a result, heterogeneity increases in fungal53 and prokaryotic communities in deeper soil layers (20–60 cm)30.

Our results demonstrated that variations in cover crops and fertility sources contribute to the co-occurrence of specific microbial groups, whereas tillage does not exhibit such an effect. This may be more evidence that tilling practices damage microbial community networks54 although it is important to remember that the scale of these studies occurs from samples collected meters apart and homogenized, thus, co-occurrence does not indicate interactions. The reason for differences in fertility source, cover crops, and tillage effects on microbial co-occurrence networks may be the input of organic matter. Fertilizer applications enhance soil nutrient levels55. Similarly, cover crops benefit soil health by adding organic carbon through roots, root exudates, and above-ground residues56,57. These specific forms of organic matter inputs recruited diverse microbial communities, which in turn influence patterns of microbial interactions. Unlike fertility sources and cover crops, tillage does not introduce additional organic matter into the soil although it does expose deeper layers to the organic matter remaining on the surface from crop residues. Ultimately though, tillage accelerates organic matter decomposition, causing a faster and more uniform release of nutrients throughout the tilled soil layers, which promotes fast-growing microorganisms7,58. In our study, we observed little variation in microbial co-occurrence patterns between fully tilled and reduced-till treatments, suggesting that reduced tillage frequency mainly influences the stochasticity of microbial processes and alters dispersal capabilities within the 0–20 cm soil layer.

Modules containing high proportions of ASVs responding to fertility sources were identified8, but not for tillage intensity or cover crops, suggesting the impact of tillage and cover crops is less pronounced, and thus, insufficient to form modules in microbial co-occurrence networks across depth. In the SHAP-based framework, we can consider the task of using a set of ASVs to predict the relative abundance of individual ASVs as a cooperative game, thus quantifying the impact of a single taxa while considering a coalition of taxa. This approach allows us to break through the limitations of traditional methods that only model pairwise relationships. Additionally, as an additive explanation method, SHAP assigns higher feature importance when predicting other taxa with higher abundance. This strategy helps ensure that the final sum of SHAP values approximates the effect of taxa on the entire module. Compared to traditional topological analysis based on networks, hub taxa identified by SHAP-based framework align more closely with the module’s response pattern, which is more consistent with the definition that changes in hub taxa may lead to changes in the entire module59. Further, hub species contain microbial taxa identified by SHAP-based framework that demonstrate strong interconnections and exert a significant community impact. We found a substantial proportion of the relative abundance of ASVs within the fertility source-sensitive module can be predicted by other ASVs. This observation underscores fungi’s pivotal role in driving the distinct contribution patterns resulting from fertility source differences. Similar to a previously discussed concept60, we hypothesize that the initial impact of fertility sources likely influences specific fungi, the effects of which subsequently cascade onto a broader microbial community.

Because an ML model may not identify stochastic processes, yet these processes are important to shaping microbial communities, interpretations of ML models should be considered in conjunction with NCM. The NCM postulates all community members have equal chances of birth, death, and relocation, regardless of species61. Such a notion might be seen as counterintuitive because the ability to grow, reproduce, and disperse varies across biotic and abiotic gradients62,63. In contrast, it is well-recognized that microbial survival and growth in soils face challenges from persistent abiotic stressors, including limited and fluctuating water availability, a dearth of organic carbon substrates, and acidic conditions11. Furthermore, microorganisms are always entwined in complex ecological interaction webs, with interactions that can affect involved species64. To compensate for the neutral model limitations, we applied the RF model based on both biotic and abiotic factors65 and used a co-occurrence network for further analysis.

Our results indicated that the roles of deterministic and stochastic processes for community assembly varied across depth, consistent with previous observations66. Reduced goodness of fit of the NCM indicated that the explanatory power of neutral theory declined in deeper layers. This observation contrasts with the finding from a 15-year field experiment67, which can be attributed to the absence of tillage in their experimental setup. However, the diminished predictive power of the RF model at greater depth does not necessarily imply a reduced influence of the deterministic process. As soil depth increases, both prokaryotic and fungal communities exhibited increasing community heterogeneity30, although bacterial taxa were more highly and consistently connected compared to fungi68. The expanded state space at depths challenges the ability of ML to discern patterns in limited samples and merits future investigation.

The proportion of predicted ASVs based on abiotic factors is limited for both prokaryotes and fungi, which might be because the abiotic factors we measured contained low heterogeneity at the local scale69. Our previous analysis emphasized that soil depth is the primary driver of microbial community changes, and the environmental variables we considered are closely associated with soil depth30. Therefore, when we conducted models for individual soil layers, these environmental variables exhibited minimal fluctuations, complicating our ability to discern their environmental filtering effects on microbial communities. Additionally, our study may have limitations due to the scope of the environmental variables measured, as acknowledged in previous studies29,70, since we focused primarily on soil bulk physical and chemical properties, which may not sufficiently address the intricate spatial heterogeneity observed in soil microbial communities at the centimeter scale11,71.

Machine learning showed that the soil microbiome can carry a strong signal to indicate fertility source, tillage, and, to a lesser degree, cover crops that were detected with RF models and these signals differed somewhat from signals determined using traditional methods such as indicator species analysis. The organic-based fertilizers were most strongly associated with the fungal family Chaetomiaceae, the majority of which are saprotrophs (decomposers), and some species are used to decompose plant biomass (reviewed in ref. 72). Family Magnaporthaceae was also strongly associated with organic fertilizers and this family contains species found in plant tissues including roots and have a nectrotroph lifestyle73. These taxa may contribute to the decomposition of greater organic residues occurring from manure and legume fertility sources. While Chaetomiaceae and Magnaporthaceae were also identified as indicators for manure using traditional methods, they were weaker indicators not in the top 10 for that fertility source. Using ML, we found a prokaryotic biomarker in the genus Nitrospira was more often found in fields fertilized with manure which could benefit the nitrite-oxidation metabolism of these bacteria74. The fungal taxon Corynespora cassiicola was both a hub taxa and biomarker of synthetic fertilization and is a well-known plant pathogen that is associated with target spot disease in several plant species including soybeans (Glycine max) (reviewed in ref. 75), suggesting greater susceptibility of species in synthetically fertilized fields in conventional agriculture.

Tillage-enriched taxa that were identified through RF models as the primary biomarkers for both prokaryotes and fungi included pathogenic taxa and decomposition specialists. For example, the fungal family Didymellaceae, which was associated with full tillage both in the ML analysis and with traditional methods, is a broad group populated with many species and occurs in diverse ecosystems, but most taxa are plant pathogens76. Nectriaceae, a fungal family associated with reduced tillage in this analysis but not with traditional methods, has around 900 species that use saprotrophic or plant pathogenic lifestyles77, suggesting an important connection with decomposition and plant health under reduced tillage. Prokaryotic families associated with full tillage included Chitinophagaceae, some species of which can decompose chitin78 which is available in the soil from organisms including fungi and insects and is potentially enhanced by tillage-associated mortality of these groups. Given that both full and reduced tillage were associated with families that have similar broad pathogenic and decomposition classifications, gaining more in-depth knowledge of each family’s unique capabilities (e.g., mode of pathogenicity or nutrient requirements) could yield hypotheses for the associations between families and tillage intensity.

Although traditional methods identified some stronger indicators than those for tillage types, the results from ML suggested that the signal from the soil microbiome to indicate the presence of cover crops was weak. In the fungal family Herpotrichiellaceae, the species Exophiala equina was associated with cover crops and previously has been found with root mycorrhizae79. In traditional methods, this family was the fifth strongest indicator of cover crops. Fungal family Dictyosporiaceae was a biomarker for fields without cover crops only as identified through ML and contains globally distributed saprotrophs80. Prokaryotic biomarker from class Dehalococcoidia that was associated with cover crops increases in previous agricultural fields after afforestation81. The genus of the family Rhizobiaceae which was a marker for cover crops, Pseudaminobacter, is commonly found in agricultural soils and is related to bacteria that form root nodules; this genus also contains atrazine-degrading species82. Family Oligoflexia which indicated fields without cover crops, includes many predatory bacteria83 that may be enhanced when root exudate sources of carbon are limited. Traditional methods only identified two prokaryotic orders indicating no cover crops and neither contained Oligoflexia, highlighting the importance of using multiple approaches to identify taxonomy signals.

The ML approach provided several benefits that enabled different types of analyses and assumptions beyond what is available with traditional approaches, but it also has some limitations which we emphasize below. One major benefit of ML is that it overcame limitations due to linear assumptions and algebraic constraints. Without these limitations, ML was better able to capture variances (particularly for the fungal community) and retain a high degree of locality preservation compared with PCoA. Although ML results can be difficult to interpret, the SHAP framework allowed a simpler linear function to explore the relationship between community structure and environmental factors from the RF models. This approach integrated environmental and agricultural management practices to demonstrate the relative influence of those factors. The SHAP framework also enabled the prediction of biomarker groups that could move beyond pairwise models and did not rely on linear correlation measures using point biserial coefficients such as that for indicator species analysis. ML approaches can handle complex datasets, yet one constraint is the requirement for large sample numbers to allow adequate model training and testing. When examining microbial interactions, though, the number of ASVs in each sample can still be overwhelming for ML as for traditional network analysis. Thus, a subset of ASVs can be used with ML approaches and SHAP to predict agricultural practices and vice versa. Another constraint, as mentioned previously, is that ML may not consider stochastic processes for shaping microbial communities and so NCM can be used in tandem to support a holistic interpretation of factors driving assembly. While the ML approaches taken with this study generally supported those patterns identified using traditional approaches, ML revealed nuanced novel information and enabled a better understanding of community assembly including biotic interactions which were not studied in the previous analysis30.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by incorporating ML models we expanded on previously identified patterns30 that used traditional approaches to determine that the diverse agricultural microbial community was shaped by deterministic factors stemming from the effects of fertility source, tillage, and cover crops. Here we also identified that the community structure was strongly a result of stochasticity. Similar to traditional methods, we found fertility source had the greatest impact on microbial communities, but ML revealed that influence diminished with depth, recruiting specific microbial modules dominated by fungi. Traditional methods identified soil depth as the strongest factor explaining both prokaryotic and fungal community composition variance, but in this study, ML enabled a more nuanced interpretation where for fungi, fertility source was a far more important factor. In traditional approaches, cover crops only explained the community variance of fungi when the full-depth profile was considered, but in this study, we found cover crops exerted an influence on both prokaryote and fungi co-occurrence patterns and that, like with traditional approaches, it was smaller than fertility source and was not consistently depth dependent. In contrast, we found the effect of tillage on the microbial community was concentrated in 0–20 cm, which intensified the importance of the stochastic process while reducing dispersal limitations and potentially destroying microbial interactions. With traditional approaches, tillage was also only influential in the surface soils, but without machine learning, the overall influence with regard to assembly could have been minimized as tillage explained almost negligible (~1.7%) variance. Collectively, our results showed that in a long-term agricultural field trial, highly diverse soil microbial communities differentiate with agricultural practices, but that stochasticity is a fundamental driver of community structure especially in surface soils. Further, we demonstrated that ML models can break through certain linear limitations of traditional methods, providing a better understanding of co-occurrence patterns, assembly processes, and mechanisms underlying the microbial community at different soil depths under different agricultural practices.

Methods

Dataset description and preprocessing

Soil samples were collected on January 28 and 29, 2019 from Rodale Institute’s Farming Systems Trial in Kutztown, PA, USA which was initiated in 1981. The soil type is Clarksburg silt loam, which is an Alfisol. Fields have an average slope of 3%. Agricultural treatments were fertility source (organic legume, organic manure, or synthetic inorganic fertilizer), tillage type (full or reduced tillage), and winter cover (cover crops or fallow (only for synthetic fertilizer)) for a total of eight different agricultural treatments. Each agricultural treatment was used for three replicate fields each with an area of 0.05 ha.

Soil cores were collected to 1 m depth using a hydraulic soil probe (Giddings, Windsor, CO, USA) that was 4.58 cm in diameter. Four soil cores were collected from each of the three replicate fields per agricultural treatment and soil was divided into 0–10 cm, 10–20 cm, 20–30 cm, and 30–60 cm. Depth sections were homogenized to combine the same depth section for all four soil cores from a replicate field resulting in a total of 96 soil samples. The soil was subsampled and stored at −80 °C until nucleic acid extraction. The remaining soil was used for analyzing physicochemical parameters by Rodale Institute (gravimetric water content, bulk density, whole soil stability index), Penn State Agricultural Analytical Services Laboratory (University Park, PA, USA) (cation exchange capacity, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, copper, sulfur, zinc, iron, manganese, aluminum, sodium, and acidity), Cornell Nutrient Analysis Laboratory (Ithaca, NY, USA) (loss-on-ignition soil organic matter, total carbon, total nitrogen, total hydrogen), and Soil Fertility Lab at the Ohio State University (Wooster, OH, USA) (mineralizable carbon, permanganate-oxidizable carbon, autoclaved-citrate extractable protein).

Total DNA was extracted from 0.25 g soil subsamples using the DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen) and amplified and sequenced by Magigene Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). Sequencing included three negative controls that were empty tubes processed alongside samples starting with DNA extraction. Amplicons for prokaryotes targeted the 16S rRNA gene using primers 515F84 and 806R85. Amplicons for fungi targeted the ITS2 region using primers ITS3 Forward and ITS4 Reverse86. Amplified samples were sequenced using NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina). High throughput sequencing data for amplicons of both bacteria/archaea and fungi have been deposited to the NCBI Sequencing Read Archive (SRA) with accession number PRJNA635685.

Sequences were processed using R (version 4.0.3) with the package dada2 (version 1.18.0) to identify amplicon sequence variants (ASVs). Prokaryote ASVs were annotated for taxonomy using the SILVA database87,88 (version 138.1) and fungi were annotated with the UNITE database89 (version 8.3). Microbial datasets were curated using R package decontam90 (version 1.2.0) to remove contaminant ASVs based on the negative controls using (16S threshold = 0.52, ITS threshold = 0.1), and ASVs identified as chloroplasts and mitochondria were removed. See Bier et al.30 for additional environmental and biotic data collection and preprocessing details. All amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) excluding contaminants, chloroplasts, and mitochondria were included in the canonical analysis and the NCM model tests because the Bray–Curtis distance used can address the issue of double zeros arising from infrequent ASVs. Additionally, the NCM model requires a comprehensive species abundance distribution to accurately fit the correlation between frequency and relative abundance in a community61.

For co-occurrence network analysis and the construction of RF models (including using the relative abundance of ASV as input model features and as prediction targets), we used a subset of ASVs. When constructing co-occurrence network, only ASVs present in at least half of the samples within the selected depth range were used to ensure the reliability of the correlation calculation91. When building an RF model and using the relative abundance of ASVs as prediction targets, the same ASVs used in co-occurrence network analysis were used for two reasons. Firstly, when employing the relative abundance of ASVs as the target variable, the model struggles to discern underlying data patterns if the target predominantly consists of zeros. Secondly, when using the relative abundance of ASVs as features, the issue of high dimensionality and low sample size arises, leading to overfitting of the ML model.

Given the specific requirements of these models, the ASVs present in at least half of the samples within the selected depth range were defined as common ASVs for clarity of the analysis below. These common ASVs were then employed in the construction of co-occurrence network, the factors-based RF model for predicting abundance profiles, and the RF model for discerning agricultural practices.

To assess the influence of biotic and abiotic factors on specific taxa, we categorized the abundance profile of other taxa as biotic factors. In contrast, environmental factors and agricultural practices were classified as abiotic factors65 and included soil protein, sulfur, carbon exchange capacity (CEC), K% saturation of CEC, total mineralized carbon, potassium, gravimetric water content, permanganate-oxidizable carbon, Ca% saturation of CEC, sodium, organic matter, acidity, pH, calcium, total carbon, bulk density, carbon:nitrogen ratio, zinc, total nitrogen, Mg% saturation of CEC, manganese, aluminum, iron, copper, total hydrogen, whole soil stability index, phosphorus and magnesium30.

Interpretation of machine learning model based on SHAP values

Due to the black-box nature of ML models, interpreting them can be challenging. To address this problem, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)18 framework to get insights from the fitted ML model. SHAP is a popular interpretation method based on Shapley values92 from cooperative games, which is a unique solution to satisfy with a set of desirable properties. SHAP assign each explanatory variable (i.e., feature, such as depth in abiotic factors or relative abundance of a specific taxon in biotic factors) a SHAP value as feature importance to quantify its influence on a prediction target (e.g., relative abundance of a specific taxon or the probability of being associated with certain agricultural practices) for a certain sample. By evaluating the marginal contribution of features on different feature subsets, SHAP can capture possible interactions between features. And by summing the marginal contribution using unique Shapley kernel weights, SHAP can ensure that the sum of all feature importances is equal to the output of the model. SHAP focus on local interpretability, which explains a model’s individual predictions. For example, when we use the relative abundances of microbiome taxa to identify the type of fertility source for a sample if the SHAP value for a specific taxon related to legumes is 0.02, we can interpret this as the abundance of that taxon increasing the probability that the machine learning model will identify the fertility source as legume by 2%. To understand how much models rely on each feature at the scale of the entire dataset, the absolute sum of the SHAP values for all samples was calculated as global feature importance. Due to its efficiency in explaining tree-based models, we employed the TreeExplainer algorithm to estimate SHAP values from all fitted RF model using TreeExplainer in shap Python module93.

Machine learning-based canonical analysis

To understand the relationships between soil microbial communities and environmental factors under agricultural practices, a ML-based canonical analysis was proposed. Like db-RDA94, our method relies on a matrix of distances. Since traditional ordination methods such as Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA)95 and Multidimensional Scaling (MDS)96 fall short in capturing complex nonlinear structures97, we applied manifold learning to effectively uncover composite patterns and enhance the cluster structures of microbial communities98. t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE)99 is a manifold learning technique that minimizes the Kullback-Leibler divergence to represent high-dimensional data in a lower-dimensional space. This technique has been proven to outperform traditional ordination methods on the more complex ecological datasets, effectively extracting meaningful ecological drivers of variability in community composition100. t-SNE was used as an ordination method to discern ordered relationships and reveal the degree of preservation of the distance between closer or further samples (T-SNE function in scikit-learn Python module101). Perplexity is a critical hyperparameter that balances the preservation of both local and global structures within the dataset. Since t-SNE is not an eigenvector-based method, explained variance score was used to quantify the effect of ordination, which is calculated by the distance in the original and reduced space after z-score normalization. To achieve the optimal dimension reduction effect, the perplexity was fine-tuned with the goal of maximizing the explained variance score. The final selected perplexity parameter values were 83 for prokaryotes and 90 for fungi. To further comparing the performance of PCoA and t-SNE, the degree of locality preservation (DLP)102 was employed to estimate the degree of structure retention following dimensionality reduction. The explained variance score of each axis was calculated by the explained variance score of each axis after PCA rotation. The t-SNE-derived ordination was rescaled to the range [−1,1] using Min-Max Scaling (MinMaxScaler function in scikit-learn Python module) for mapped analyses.

Then the RF model was performed with a tenfold cross-validation for estimation of the t-SNE-derived ordination (RandomForestRegressor and KFold in scikit-learn Python module)103. We took four categorical features (depth, fertility source, tillage type, and winter cover) and seven numerical features (organic matter, C:N ratio, total carbon, total hydrogen, total nitrogen, and bulk density, other soil properties at 30–60 cm were not collected) to explain the variability of microbial community structure. To measure the impact of individual environmental factors and agricultural practices on the structure of the microbial community, the SHAP interpretability framework was introduced. For each of the ten iterations of cross-validation, SHAP values of environmental factors and agricultural practices were calculated on the corresponding test set. The final SHAP value was derived by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of the SHAP values from the two axes, which quantified the importance of environmental features for explaining the variability in community composition. To validate the effectiveness of the features, random variables were introduced into the feature table. A t-test (ttest_ind function in scipy Python module104) was then conducted to compare the SHAP values of the actual features with the random variables. Features that exhibited SHAP values significantly higher than those of the random variables (using a t-test with a significance level of p < 0.05) were considered to have a meaningful impact on the microbial community structure.

Neutral community model

NCM61 was used to explore the potential role of stochastic processes in microbial community assembly. This model has been widely applied to interpret data from environmental samples at various scales28,29. Stochastic process suggests that stochastic, births, deaths, and immigration play a key role in shaping microbial communities. Under this assumption, soil microbial communities are considered as local communities that are 100% stochastically assembled. Then we can assume that at the metacommunity level (in the experiment, we regarded the metacommunity as the community of all samples including samples from different depths and samples under different tillage intensities), all individuals originated from a source community and stochastic processes caused all variation in the community composition. The NCM proposed a method of parameterization using a beta cumulative distribution function to describe the relationship between the detection frequency of each ASV and its relative abundance in the broader metacommunity. Within the model’s framework, N denotes the local community size, which can be calculated from average reads per sample. The immigration rate, denoted by m, represents the probability that a dead individual is replaced by an immigrant from a source community. This parameter can be used to reflect the dispersal ability of taxa, and Nm gives the estimated dispersal between communities29. The parameter m was estimated through nonlinear least squares. Under a given immigration rate, the abundance of a taxon in this source community dictates both the frequency and the abundance at which it is observed in the local community. The R2 value, derived from the predicted abundance frequency and the experimentally measured abundance frequency, reflects the model’s overall fit to the neutral theory, which can be interpreted as the importance of stochastic processes in shaping communities. Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated for a binomial distribution using the binconf function in Hmisc R package105. The stochastic models were run three times for each community (prokaryotic or fungal): across all depths, at each depth, and under different tillage intensities. Sample sizes of different groups were comparable, ensuring that sample size did not affect the comparisons. All computations were performed in R106.

Random forest model to predict community structure

In the NCM model, the neutral assumption ignores the innate difference between species and their response to environmental factors61,107. To further analyze the impact of abiotic and biotic selection on microbial communities, RF models were constructed based on abiotic factors (including 24 soil properties as numerical features and 3 agricultural practices as categorical features), and biotic factors (including from hundreds to thousands in the abundance of other ASVs beyond the target taxa as numerical features) to predict the abundance of ASVs65. Since we built models separately for each soil layer, soil depth was not used as a feature to train the model. To ensure the validity of the RF model, only common ASVs were used. Regressions were conducted with relative abundance of common ASVs as the dependent variable, and the biotic factors or abiotic factors as independent variables. A ten-fold cross-validation was employed to validate the model across the entire dataset, and R² was chosen to assess the regression (RandomForestRegressor and KFold in scikit-learn Python module). The proportion of predictable ASVs was used as a metric to evaluate the RF model108, and ASVs with a predicted R² score greater than 0.2 were defined as predictable ASVs. Based on 1000 simulations of random inputs, the threshold of 0.2 is established with a 95% confidence interval. This suggests that the likelihood of obtaining an R² value from the RF, when using random input, that exceeds 0.2 is less than 5%.

Co-occurrence networks and network inference

Given the intricate high-dimensional nature and limited sample size of microbiome data, direct modeling using machine learning poses challenges. By leveraging co-occurrence networks and identifying sensitive ASVs proposed by Hartman et al.8, which was described below, a subset of ASVs was pre-identified that are responsive to agricultural practices and exhibit potential interactive dynamics. The co-occurrence patterns of the microbiome were studied across the unique depth environments by building microbial networks at each soil depth. The nodes in networks represented ASVs, and the edge represented a strong and significant correlation between nodes. To ensure the reliability of the correlation calculation, only common ASVs were included for the correlation calculation. The Spearman correlation cut-off value was set at 0.76, determined with random matrix theory method109. The p-value adjusted by the FDR cut-off value was 0.005. Topological features were calculated using the igraph package110 in R. The number of edges was determined with the ecount function, while the diameter was ascertained using the diameter function. Modularity, a metric indicating how isolated portions of the network are such that they can be separated into distinct modules was estimated with the modularity function.

The identification of sensitive ASVs has been described previously in the literature8. Correlation-based indicator species analysis was used with the R package indicspecies111 to calculate the correlation coefficient of an ASV’s positive association with various agricultural practices. This analysis involved 1000 permutations and was considered significant at p < 0.05. Furthermore, differential ASV abundance was assessed under differing agricultural practices using likelihood ratio tests (LRT) with the edgeR R package112. ASVs with abundances identified as varying between agricultural practices, at a false discovery rate (FDR) corrected value of p < 0.05, were deemed responsive to those practices. ASVs that were validated by both indicator species analysis and LRT were categorized as sensitive taxa to agricultural practices.

To investigate the community structure within co-occurrence networks at various depths, network modules were identified, which are substructures consisting of nodes with a higher density of edges. A greedy optimization of modularity algorithm was applied113 as implemented in the igraph R package for this purpose. Fertility source-sensitive modules were defined according to two criteria: (1) the number of ASVs in the module must exceed 5% of the node number of the network, and (2) the proportion of sensitive ASVs in the module must be greater than 25%. Modules satisfying both criteria were identified as fertility source sensitive and were named accordingly, with the prefix being the fertilizer associated with the highest proportion of sensitive ASVs within the module. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to examine cumulative relative abundance differences of samples under different fertility sources.

To evaluate the importance of abiotic factors and biotic factors, the RF model outlined in the section “Random forest model to predict community structure” was employed. The prediction target of the RF model is the relative abundance of ASVs in the module, while abiotic factors are unchanged but biotic factors are replaced by the abundance of other ASVs in the module, including dozens to hundreds of numerical features, depending on the size of the module. Given the high mutual predictability of taxa in modules, the SHAP framework was used to interpret the biological interactions of specific taxa. While traditional approaches identify hub taxa primarily based on node degree8,22, it is important to note that microbial interactions can exhibit asymmetry or extend across multiple species, posing significant constraints on the efficacy of this method under such circumstances23,114. To overcome these limitations, a hub taxa identification method based on SHAP values was proposed. In the SHAP-based framework, the SHAP value was used to quantify the impact of specific taxon to predict others in the module, and the SHAP values of specific taxon on the corresponding test set were calculated. In this application scenario, the SHAP value of a specific taxon can be interpreted as the expected change in the relative abundance of a different target taxon caused by the presence of this specific taxon. By summing the absolute SHAP values of prediction of all other taxa, the impact of this specific taxon on the entire module can be gauged. This strategy involved assessing the influence of these hub taxa on the abundance profiles of other species within the community115. To ensure the reliability of the assessment of influence, only the SHAP values associated with predictable ASVs (R2 > 0.2) were used in the summation. The top ten percent of ASVs that affect the module were defined as hub taxa. These hub taxa were then employed to retrain the RF model, used to predict the taxa in the whole module, and were compared with the RF model trained on the full set of taxa in the module.

To further compare hub taxa identified by SHAP-based frameworks with those identified by traditional degree-based approaches, the top ten percent of ASVs with the highest degree in the modules were identified as traditional hub taxa. Hub taxa are considered to have a significant influence on the composition of community59, therefore, changes in hub taxa could potentially lead to shifts in the composition of the fertility source module. We employed structural redundancy analysis116 to evaluate the consistency of variation of the module and hub taxa identified by two approaches. In structural redundancy analysis, the full set of taxa in the module and hub taxa were converted to a triangular matrix of similarities between all pairs of samples using the Bray–Curtis distance. Pearson correlations were then computed between the corresponding entries in the two underlying triangular matrices as a metric of consistency. A higher Pearson correlation coefficient indicated a more consistent response pattern between the module and hub taxa.

Random forest model to identify agricultural practices and biomarker selections

For the RF model to distinguish between different agricultural practices, the agricultural practices were set as the target variable (including three classification targets: three types of fertility source, cover crop or not, and two tillage types), while using the relative abundances of common ASVs (including hundreds to thousands of numeric variables) as independent variables for classification of three agricultural practices. Ten-fold cross-validation was used to validate the model at each depth103, and the model was established using RandomForestClassifier with n_estimators = 1000 and KFold in scikit-learn Python module. To solve the problem of sample imbalance, the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) was selected to evaluate the classification of agricultural practices117. AUC value ranges between 0 and 1 where the score of 1 means a perfect predictor, which means that the model can successfully identify the corresponding agricultural practices using relative abundance of microbial taxa. The threshold of 0.5 serves as a critical point of reference in evaluating the model’s effectiveness, and AUC below 0.5 suggests the model has no capacity to discern agricultural practices. AUC was calculated using roc_auc_score with multi_class = ‘ovo’ in scikit-learn Python module.

When the number of features substantially outweighs the number of samples, machine learning models tend to overfit. This means they unintentionally capture noise from the training data, leading to poor generalization and performance on new, unseen data, such as test set data or samples from different datasets, like those from other farms. To ameliorate this obstacle, a SHAP-based feature selection was proposed to improve the prediction of marker taxa for agricultural practices. After selecting the soil depth range, the RF model was first trained on the training set during each of the ten iterations of cross-validation, with the absolute sum of the SHAP values of all features was calculated. The 50 features with the highest values were selected as biomarker ASVs. The model was re-established on the training data with the selected biomarkers, which means that we only use the relative abundance of selected biomarkers as features and disregard the relative abundance of other ASVs. After that, the predictions of all ten iterations were combined to calculate the AUC score, and the absolute sum of SHAP was calculated as the basis for evaluating the primary biomarkers, which quantify the contribution of biomarkers to identify agricultural practices. Finally, the top 50 ASVs with the highest accumulated SHAP values calculated in the test set were selected as primary biomarkers. The abundance of fertility source primary biomarkers under different fertility sources was visualized using Ternary R package118.

Statistics and reproducibility

The details of statistical tests and ML models are described in each relevant section of the “Methods” section. The algorithmic nature of the ML models does not inherently possess the distributional assumptions required for calculating p-values and confidence intervals. Consequently, non-parametric methods, such as cross-validation119, are essential for estimating model uncertainty in ML120.

All computations, except for sequence processing which was conducted using R106 (version 4.0.3), were performed in R (version 4.2.1) and Python (version 3.7.13).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information, are deposited in a publicly available repository or are referenced in another publication. High throughput sequencing data for amplicons of both bacteria/archaea and fungi have been deposited to the NCBI Sequencing Read Archive (SRA) with accession number PRJNA635685. Hub taxa for Fig. 4 can be found in Supplementary Data 1. Detailed information for Figs. 6 and 7 is provided in Fig. S5a–e. Additional data sources have been uploaded to https://github.com/moyujie999/FST_ML including ordination data and SHAP values for Fig. 1, and network data for Figs. 3 and 4.

Code availability

The source code and package versions used in this study are available at https://github.com/moyujie999/FST_ML and are also archived at Zenodo121: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13910588.

References

Suman, J. et al. Microbiome as a key player in sustainable agriculture and human health. Front. Soil Sci. 2, 821589 (2022).

Rai, S. et al. Crop microbiome: their role and advances in molecular and omic techniques for the sustenance of agriculture. Planta 257, 27 (2023).

Pagano, M. et al. Advances in eco-efficient agriculture: the plant-soil mycobiome. Agriculture 7, 14 (2017).

Santos, L. F. & Olivares, F. L. Plant microbiome structure and benefits for sustainable agriculture. Curr. Plant Biol. 26, 100198 (2021).

Alexandridis, T. K. et al. An integrated approach to promote precision farming as a measure toward reduced-input agriculture in Northern Greece using a spatial decision support system. In Comprehensive Geographic Information Systems 315–352 (Elsevier, 2017).

Compant, S., Samad, A., Faist, H. & Sessitsch, A. A review on the plant microbiome: Ecology, functions, and emerging trends in microbial application. J. Adv. Res. 19, 29–37 (2019).

Desoignies, N. Plant microbiota beyond farming practices: a review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 14 (2021).

Hartman, K. et al. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome 6, 14 (2018).

Dini-Andreote, F., Stegen, J. C., Van Elsas, J. D. & Salles, J. F. Disentangling mechanisms that mediate the balance between stochastic and deterministic processes in microbial succession. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E1326–E1332 (2015).

Postma-Blaauw, M. B., De Goede, R. G. M., Bloem, J., Faber, J. H. & Brussaard, L. Soil biota community structure and abundance under agricultural intensification and extensification. Ecology 91, 460–473 (2010).

Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 579–590 (2017).

Xi, H. et al. Effects of cotton–maize rotation on soil microbiome structure. Mol. Plant Pathol. 22, 673–682 (2021).

Carbonetto, B., Rascovan, N., Álvarez, R., Mentaberry, A. & Vázquez, M. P. Structure, composition and metagenomic profile of soil microbiomes associated to agricultural land use and tillage systems in Argentine Pampas. PLoS ONE 9, e99949 (2014).

Paliy, O. & Shankar, V. Application of multivariate statistical techniques in microbial ecology. Mol. Ecol. 25, 1032–1057 (2016).

Legendre, P. & Legendre, L. Numerical Ecology (Elsevier, 2012).

Hernández Medina, R. et al. Machine learning and deep learning applications in microbiome research. ISME Commun. 2, 98 (2022).

Zhao, X., Wu, Y., Lee, D. L. & Cui, W. iForest: interpreting random forests via visual analytics. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 25, 407–416 (2019).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Neural Information Processing Systems 4768–4777 (2017).

Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S. & Guestrin, C. ‘Why should I trust you?’ Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proc. 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 1135–1144 (ACM, 2016).

Rynazal, R. et al. Leveraging explainable AI for gut microbiome-based colorectal cancer classification. Genome Biol. 24, 21 (2023).

Talmor-Barkan, Y. et al. Metabolomic and microbiome profiling reveals personalized risk factors for coronary artery disease. Nat. Med. 28, 295–302 (2022).

Ma, B. et al. Earth microbial co-occurrence network reveals interconnection pattern across microbiomes. Microbiome 8, 82 (2020).

Faust, K. Open challenges for microbial network construction and analysis. ISME J. 15, 3111–3118 (2021).

Berry, D. & Widder, S. Deciphering microbial interactions and detecting keystone species with co-occurrence networks. Front. Microbiol. 5, 219 (2014).

Michel-Mata, S., Wang, X.-W., Liu, Y.-Y. & Angulo, M. T. Predicting microbiome compositions from species assemblages through deep learning. iMeta 1, e3 (2022).

García-Jiménez, B., Muñoz, J., Cabello, S., Medina, J. & Wilkinson, M. D. Predicting microbiomes through a deep latent space. Bioinformatics 37, 1444–1451 (2021).

DiMucci, D., Kon, M. & Segrè, D. Machine learning reveals missing edges and putative interaction mechanisms in microbial ecosystem networks. mSystems 3, e00181–18 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Stochastic processes drive bacterial and fungal community assembly in sustainable intensive agricultural soils of Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 778, 146021 (2021).

Chen, W. et al. Stochastic processes shape microeukaryotic community assembly in a subtropical river across wet and dry seasons. Microbiome 7, 138 (2019).

Bier, R. L. et al. Agricultural soil microbiomes differentiate in soil profiles with fertility source, tillage, and cover crops. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 368, 109002 (2024).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Asnicar, F., Thomas, A. M., Passerini, A., Waldron, L. & Segata, N. Machine learning for microbiologists. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 22, 191–205 (2024).

Wilhelm, R. C., van Es, H. M. & Buckley, D. H. Predicting measures of soil health using the microbiome and supervised machine learning. Soil Biol. Biochem. 164, 108472 (2022).

Dormann, C. F. et al. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 36, 27–46 (2013).

Hao, J. et al. The effects of soil depth on the structure of microbial communities in agricultural soils in Iowa (United States). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e02673-20 (2021).

Rumpel, C. & Kögel-Knabner, I. Deep soil organic matter—a key but poorly understood component of terrestrial C cycle. Plant Soil 338, 143–158 (2011).

Dincă, L. C., Grenni, P., Onet, C. & Onet, A. Fertilization and soil microbial community: a review. Appl. Sci. 12, 1198 (2022).

Srour, A. Y. et al. Microbial communities associated with long-term tillage and fertility treatments in a corn-soybean cropping system. Front. Microbiol. 11, 522658 (2020).

Aas, K., Jullum, M. & Løland, A. Explaining individual predictions when features are dependent: more accurate approximations to Shapley values. Artif. Intell. 298, 103502 (2021).