Abstract

Gene duplication and divergence are essential to plant evolution. The Arabidopsis type-A response regulator (ARR) family, negative regulators in cytokinin signaling, exemplifies gene expansion and differential retention. Despite extensive research, the understanding of type-A RR homologs in woody plants remains limited. In this study, the evolution history of type-A RR gene families across four rosids and one monocot has been comprehensively investigated. Focusing on Populus deltoides, a unique pair of dispersed duplicates, PdRR8 and PdFERR, is identified, and their duplication is estimated to have occurred in the common ancestor of the four rosids. The duplication remnants corresponding to PdRR8 have been retained in all rosids but the counterpart of PdFERR has been lost. In poplar, PdRR8 shows the highest expression levels in leaves, while PdFERR is specifically expressed in female floral buds. Among various external stimuli, cold strongly represses PdRR8 promoter activity, whereas 6-BA markedly inhibits that of PdFERR. Overexpression of PdRR8 in the Arabidopsis arr16arr17 double-mutant fully complements the reduced hydrotropic response. In contrast, PdFERR fails to rescue the hydrotropic defects of the mutant. Results of evolutionary, expression and functional analyses indicate that PdRR8, rather than PdFERR, is the true ortholog of the ARR16-ARR17 paralogs. Though PdRR8 and PdFERR originate from a common ancestral gene and evolve under strong negative selection, these two dispersed duplicates have exhibited differential expression and some degree of functional divergence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gene duplication has been viewed as an important driving force for phenotypic diversity and adaptive evolution1,2. Duplicate genes can be generated through either small-scale duplications (SSDs, i.e. tandem duplication, dispersed duplication, or retrotransposition) or large-scale events (i.e. chromosomal or whole genome duplication, WGDs)3,4. Duplicated genes deriving from SSD or WGD may have different evolutionary rates, retention probabilities, and functional categories3,5. Additionally, various subsequent evolutionary possibilities, such as hypofunctionalization, neofunctionalization, subfunctionalization or dosage balance, etc., lead to preferential retention versus loss of duplicated genes6,7.

A high prevalence of duplicate genes has been illustrated in plant genomes8,9. In Arabidopsis thaliana, integrated analysis of WGD-derived duplicated genes and functional annotation data revealed that genes involved in signal transduction and transcription had been preferentially retained10. Moreover, comparisons between gene duplicates produced by small- and large-scale events demonstrated that genes related to signal transduction were more likely to be retained following WGD than SSD11. The cytokinin signaling pathway is one of the best-characterized signal transduction systems in plants, and it involves three components: a plasma membrane-localized histidine kinase (HK), a His phosphotransfer protein (HP), and a response regulator (RR). The Arabidopsis type-A response regulator (ARR) genes act as negative regulators of the cytokinin signaling pathway and represent the youngest subgroup among the three types of ARRs12. The expansion/duplication of the type-A ARR gene family has been demonstrated to be tightly associated with the most recent polyploidy event (α-WGD)13,14. The type-A ARR family consists of 10 typical members that fall into five paralogous pairs (ARR3/4, ARR5/6, ARR7/15, ARR8/9, and ARR16/17). Similar expression patterns and partial functional redundancy have been observed between ARR paralogous genes15,16. For instance, ARR3 and ARR4 act redundantly in the determination of the circadian period in Arabidopsis17; ARR7 and ARR15 redundantly contribute to sustaining the activity of the embryonic root stem-cell niche18; both ARR8 and ARR9 function as negative regulators in osmotic stress response19; ARR16 and ARR17 are redundant genes essential for the responsiveness to hydrostimulation20.

Despite impressive advances in Arabidopsis, relatively little is known about the functional significance of type-A RR genes in woody plants. Notably, recent studies on sex determination in different Populus species discovered the associations between feminization and the same type-A RR gene21,22,23. In P. deltoides, the gene was named as FERR because of its female-specific expression. Complete FERR genes are present in the pseudo-autosomal regions on both X and Y chromosomes, while its partial duplicate gene, FERR-R, is present only in the hemizygous region on Y chromosome and generates siRNAs suppressing FERR function, thereby acting as a femaleness suppressor in males22. Compared with Arabidopsis, which has experienced three WGD events (γ-, β-, and α-duplication), Populus has undergone only two WGDs (γ- and p-duplication)24. However, the number of type-A RR genes was similar between Arabidopsis and Populus14,25. Therefore, differential retention and functional divergence of ancestral type-A RRs occurred in a lineage-specific way. To decipher the gene duplication, divergence, and differential retention, here we performed integrated phylogenomic and collinearity analyses in five plant species (A. thaliana, P. deltoides, Vitis vinifera, Carica papaya, and Oryza sativa) that have experienced at least one round of WGD. We further characterized two type-A PdRR genes, PdRR8 and PdFERR (PdRR9), the closest homologs to the Arabidopsis ARR16/17 genes, with respect to their expression patterns, their abilities to complement the arr16arr17 double-mutant as well as their evolutionary history. The results will present a panoramic view of the lineage-specific retention and loss of type-A RR genes. Comparison of the expression and function of PdRR8 and PdFERR will not only provide functional information on type-A RR genes in woody plants but also improve the understanding of functional conservation or diversification among orthologs and paralogs.

Results and discussion

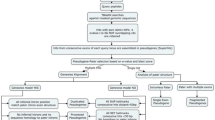

Evolutionary history of the type-A RR genes

In the five examined species, a total of 36 type-A RR genes were identified, including nine PdRRs, seven CpRRs, 11 VvRRs, and nine OsRRs (Supplementary Data 1). Synteny and collinearity analyses, conducted at both the intra-genome and inter-genome levels, uncovered 28 paralogs and 52 collinear orthologs among these genes (Supplementary Data 2). Classification of gene duplication modes indicated that the expansion of type-A RRs in Vitis was primarily attributed to tandem and proximal duplications; however, WGD/segmental duplication predominantly contributed to the expansion in Arabidopsis and Populus (Supplementary Data 2). In order to infer the associated WGD events that have led to the expansion of type-A RRs, the median Ks values were calculated for each of the syntenic chromosomal block (SCB) pairs harboring these genes (Supplementary Data 2). In Populus, the overall median Ks values of p-WGD and γ-WGT duplicates were about 0.27 and 1.54, respectively24. Of the eight PdRR-harboring SCB pairs, three with median Ks values ranging from 0.25 to 0.29, likely originated from the p-WGD. Two pairs, with median Ks values of 1.76 and 1.94 respectively, likely arose from the γ-WGT. The remaining three SCB pairs, showing median Ks values above 2.50, appeared to have a more ancient origin prior to the γ-WGT (Fig. 1a). According to the median Ks values reported previously24,26, the corresponding WGD events associated with the expansion of type-A RRs were also deduced in the other four species. As shown in Fig. 1a, nine SCB pairs displayed a low median Ks value ranging from 0.11 to 0.97, suggesting a relatively recent origin, while seven pairs showed significantly higher Ks values ranging from 1.56 to 2.90, indicating more ancient origins.

a Median Ks values of syntenic chromosomal block pairs harboring the type-A RR paralogs. b Time-scaled phylogenetic tree of 46 type-A RR genes from the five plant species. Bayes posterior probabilities are indicated at each node. Light gray shadows indicate the estimated time ranges of speciation events according to TimeTree61. The gray dashed lines represent the inferred times of WGD or WGT events based on previous studies26,50. The colored circle and square represent a WGD and a WGT event, respectively. Collinear orthologous gene pairs are connected by pink curves. Three COGs are marked with different colors for ease of visualization. Gene structures are shown on the right side. The phylogeny of the five plant species (cartoon created with BioRender.com), with their ancestral polyploidy events indicated on the branches, is displayed in the top left corner.

Tatusov et al.27 utilized the term Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) to denote individual orthologous genes or orthologous sets of paralogs from multiple genomes ( ≥ 3). Based on the above analyses, three distinct COGs were delineated among the identified type-A RR paralogs and collinear orthologs (Supplementary Fig. 1). The first COG, consisting of 11 genes, showed retention of duplicates from their ancestral loci across all five species. The second and third COGs, containing 12 and 5 genes respectively, showed a pattern where duplicates from the ancestral loci were maintained in the four rosids but were absent in rice. Phylogenetic analysis clustered the 36 type-A RR genes into three major clades. The three COGs within type-A RRs were predominantly distributed across Clades II and III (Fig. 1b). Clade III, distinct from the others, contained 20 type-A RR genes exclusive to the four rosids and included two of the three COGs. Within the third COG, PdRR8 was the only collinear ortholog of ARR16 and ARR17 in Populus. In addition, PdRR8 and PdFERR (PdRR9) were paralogs formed by dispersed duplication (Supplementary Data 2). Both of them were located in the pseudoautosomal region of the sex chromosome (Chr. 19 of P. deltoides) and shared 73.81% identity at the amino acid level (Supplementary Fig. 2). No collinear ortholog of PdRR9 had been detected in the other examined species. Since the Ks value for the paralogs PdRR8-PdRR9 was 3.4323, significantly higher than the median Ks associated with γ-WGT (1.54), we speculated that they might originate from a very ancient duplication event.

Divergence time of PdRR8 and PdFERR

Of the nine detected PdRR paralogs, the pair PdRR8-PdFERR was the only one generated via dispersed duplication (Supplementary Data 2). The divergence times of the other eight PdRR paralog pairs have been inferred through the molecular dating method based on median Ks values (Fig. 1a). To estimate the divergence time of PdRR8 and PdFERR, the monocot–dicot separation ( ~ 152 million years ago, Mya) was used to calibrate the root node of the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, the α-WGD event ( ~ 49.27 Mya)28 and the p-WGD event ( ~ 58 Mya)29 were used to calibrate the closest nodes of sister ARR paralogs and PdRR paralogs, respectively. Results of Bayesian inference show that PdRR8 and PdFERR probably arose from the initial duplication of an ancestral gene approximately 118.4 Mya (CI interval 91.5–144.5 Mya) in the Cretaceous period (Fig. 2). This was comparable to the divergence time ( ~ 114.4 Mya) estimated by using the formula Ks/(2 × 1.5 × 10−8)9. The timing of rapid rosid radiation has been dated to 108–91 Mya30. Therefore, the ancestral copy of PdRR8 and PdFERR had been duplicated in the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of the four examined rosids. Intriguingly, homologous genes from all three other rosids phylogenetically clustered with PdRR8. In contrast, the PdFERR branch was represented by only one homolog from papaya. This suggested that the duplication remnant corresponding to PdFERR might have been lost in Arabidopsis and Vitis. Results of the divergence time estimation, combined with the above inter-genomic synteny analysis, strongly suggested that PdRR8, not PdFERR, was the true ortholog of ARR16/ARR17. It is generally believed that orthologs retain the same biological function in different species, whereas paralogs tend to evolve toward functional diversification31,32. In the following sections, we further investigated the expression and functional divergence between the paralogs PdRR8 and PdRR9.

Horizontal blue bars on each node indicate the 95% credible interval of divergence time, and confidence interval values are inside brackets. Numbers above the bars represent the ages of the nodes (million years ago, Mya). The geologic time scale is shown at the bottom, with different periods being separated by different color shadings.

Differential expression patterns of PdRR8 and PdFERR

Expression patterns of PdRR8 and PdFERR were first examined in various vegetative and reproductive organs of P. deltoides, including roots, debarked stems, young leaves, barks, male and female flower buds. Among the examined organs, PdRR8 showed strong expression in roots and leaves and moderate expression in male and female flower buds. In contrast, PdFERR was both specifically and highly expressed in female flower buds sampled at mid-August (Fig. 3a). Results of the qRT-PCR analyses corroborated the earlier finding that PdFERR was expressed only during the early development of female flowers in P. deltoides22.

a qRT-PCR analyses of PdRR8 and PdFERR in different tissues of poplar. Tf1 and Tf2 represent female floral buds sampled at the end of June and mid-August, respectively. Tm1 and Tm2 represent male floral buds sampled at the end of June and mid-August, respectively. Ubiquitin gene was used as an internal control. Error bars indicate the mean values (±SD) of three replicates. Bars with distinct letters are significantly different at P < 0.05 level applying Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test. b Promoter activity analysis in transgenic tobacco. Schematic of the promoter::GUS vectors are shown on the top panel, and GUS histochemical staining of different tissues from the wild type and transgenic tobacco plants are shown on the bottom panel. c and d GUS staining of leaf disks from the wild type and transgenic tobacco plants under various external stimuli. Scale bars represent 5 mm.

Promoter activities of the PdRR8 and PdFERR were further compared by analyzing the expression patterns of the GUS reporter gene in transgenic tobacco plants. No GUS activity was observed in wild-type plants, whereas strong activity was detected in all tissues and organs of the 35S::GUS transgenic tobaccos, with the exception of the roots and filaments (Fig. 3b). In vegetative tissues and organs, the expression of GUS driven by the PdRR8 promoter was weak in callus, but relatively abundant in leaf buds, leaves, and at the bottom side of stems (Fig. 3b). By contrast, the PdFERR::GUS expression was high in leaves but relatively lower in callus, leaf buds, and at the bottom side of stems. Compared to their expression in shoots, much lower blue staining was observed in roots for all three promoters (Fig. 3b). Although PdRR8 was highly expressed in P. deltoides roots, GUS activity was nearly undetectable in transgenic tobacco roots. This differential expression between endogenous and heterologous systems could potentially be attributed to different transcription factors present in the roots of poplar and tobacco, or it might alternatively be influenced by differences in developmental stages. In flowers of transgenic tobaccos, the activity of PdRR8 promoter was detected only in anthers, but the activity of PdFERR promoter was observed exclusively in stigmas (Fig. 3b). Previously, PdRR8 and PdFERR were found to be preferentially expressed in male and female flowers of P. deltoides, respectively14. Therefore, the distinct GUS activities observed in transgenic tobacco flowers were consistent with the sexually dimorphic expression of these genes in P. deltoides.

The promoter sequences of PdRR8 and PdFERR were characterized using the online software PlantCARE, and a series of putative cis-regulatory elements were detected (Supplementary Data 3). To assess the role of the identified regulatory elements, transgenic tobacco plants harboring 35S::GUS, PdRR8::GUS, or PdFERR::GUS were treated with various signaling molecules followed by histochemical staining. A reduced GUS staining was observed for the PdRR8 promoter treated with salicylic acid (SA), while the GUS activity driven by the PdFERR promoter was apparently reduced in response to 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA) treatment. Thus, the promoter region of PdRR8 and PdFERR might contain different repressor elements that negatively responded to SA and abscisic acid (ABA) treatment respectively (Fig. 3c). The type-A ARRs of A. thaliana have been established as cytokinin primary-response genes, and expressions of almost all the type-A ARRs (ARR4-ARR9, ARR15, ARR16) were enhanced upon exogenous cytokinin treatment13,33. However, the PdRR8 promoter seemed nonresponsive to 6-BA treatment, while the PdFERR promoter was negatively regulated by 6-BA (Fig. 3c). Expression differences in response to cytokinin treatment between the PdRRs and ARRs might be due to species divergence in either cis-regulatory elements or trans-regulatory factors. Moreover, variations in the duration of the treatment and other effectors might also contribute to the expression differences.

We also exposed the transgenic tobacco plants to a variety of abiotic stresses, including salinity, drought, high and low temperatures, darkness, and mechanical wounding. In response to osmotic stress (NaCl or PEG), only the PdRR8 promoter was evidently increased by the PEG-simulated drought stress (Fig. 3d). With regard to the other four kinds of abiotic stresses, histochemical staining showed that the promoter activity of PdRR8 was completely blocked by cold treatment and significantly reduced by darkness and wounding; the PdFERR promoter was apparently enhanced by high temperature, but more or less decreased by low temperature, darkness, and wounding. While the analyses of promoter activity in transgenic tobacco plants provided informative insights into the expression regulation of PdRR8 and PdFERR, caution should be taken in interpreting these results. Further studies in the native system of P. deltoides are warranted to validate these findings.

Functional divergence between PdRR8 and PdFERR

The Arabidopsis ARR16 and ARR17 were closely related sister genes originating from the α-WGD (Fig. 1a). Young gene duplicates are generally assumed to share a higher degree of functional redundancy compared to older pairs34. Indeed, both ARR16 and ARR17 were asymmetrically expressed at the lower water potential side during root hydrotropic response. Asymmetric expression of either ARR16 or ARR17 could effectively induce root tip bending. Moreover, the Arabidopsis arr16arr17 double-mutant was characterized by significantly reduced root hydrotropism20. Although orthologs of ARR16 or ARR17 have been identified in other plant species35,36, for none of these genes has a function in root hydrotropism been discovered yet. To reveal the biological function of PdRR8 and PdFERR, the CDS region of each gene was separately cloned into a binary vector under the control of 35S promoter (Fig. 4a) and transformed into the Arabidopsis arr16arr17 double-mutant. The resulting transgenic plants for each construct were designated as PdRR8_arr16/17 and PdFERR_arr16/17 respectively. To test for the ability of PdRR8 and PdFERR to complement the phenotype of arr16arr17 double-mutant, three independent representative lines (PdRR8_arr16/17: line 8, 43, and 53; PdFERR_arr16/17: line 13, 37, and 41) with relatively higher expression of the transgene were selected for root hydrotropism assays (Fig. 4b). As shown in Fig. 4c and d, the root tips of wild-type (WT) seedlings exhibited hydrotropic bending on a hydrostimulating medium, while such a phenomenon was not observed in the arr16arr17 double-mutant. The average root growth curvature of the arr16arr17 mutant in response to hydrostimulation treatment was decreased by about 55% compared with WT (Fig. 4e). The arr16arr17 double-mutant overexpressing PdRR8 showed hydrotropic root bending in response to hydrostimulation treatment, resembling the WT phenotype (Fig. 4c–e). However, the reduction in root hydrotropism of the arr16arr17 double-mutant was not affected by overexpressing PdFERR (Fig. 4c and d). Levels of hydrotropism in PdFERR_arr16/17 seedlings were similar to those in arr16arr17 mutant seedlings (Fig. 4e). Therefore, the reduction in hydrotropism of the arr16arr17 double-mutant could be restored by the poplar PdRR8 gene but not by the PdFERR gene, indicating that PdRR8 was a functional ortholog of Arabidopsis ARR16 and ARR17 involved in the regulation of root hydrotropism.

a Schematics of the PdRR8 and PdFERR overexpression vectors. b Relative expressions of PdRR8 and PdFERR in different complementary transgenic lines. Error bars indicate the standard deviations (SDs) of three replicates. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the wild-type (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; two-sided Student’s t-test). c Hydrotropic responses of representative wild-type (WT), arr16/17 double-mutant, PdRR8_arr16/17 (line 43) and PdFERR_arr16/17 (line 37) seedlings. WT-ck indicates WT seedlings grown on split agar medium with both sides made by 1/2 MS medium without D-sorbitol. The arr16arr17 double-mutant is abbreviated as “arr16/17”. PdRR8_arr16/17 and PdFERR_arr16/17 represent complementary transgenic plants overexpressing PdRR8 and PdFERR in the arr16arr17 background, respectively. The letters “hyd” represent seedlings grown on split agar medium with 1/2 MS at the up left side and 1/2 MS supplemented with 800 mM D-sorbitol at the bottom right side. Scale bars represent 2.5 mm. d Propidium iodide-stained root tips of four-day-old seedlings after being transferred to the hydrostimulating medium for 2 h. Scale bars represent 100 µm. e Measurements of root growth curvatures after hydrostimulation treatment for 16 h. Each circle represents the measurement of one seedling and 53 seedlings (n = 53) were used for control or each experimental group. Box plots span the first to the third quartiles of the data. A black line and a red line in the box represent the median and mean, respectively. Different letters above the box plot indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05, Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test).

The Arabidopsis type-A ARRs play critical roles in various aspects of plant growth and development16,17,18. Overexpression of several type-A ARR genes (ARR3, ARR4, ARR6, ARR7, ARR8, ARR9, ARR16, and ARR17) may cause an early flowering phenotype in Arabidopsis15. Additionally, some type-A RR genes regulating flowering time have been reported in other plants, such as the rice OsRR137 and the rose RhRR1 gene38. We also compared the flowering time of WT, arr16arr17, and two complementary lines (line 43 for PdRR8_arr16/17 and line 37 for PdFERR_arr16/17) grown in long days (16 h/8 h light/dark). The arr16arr17 double-mutant seedlings flowered at the same time as WT (Fig. 5a). Overexpression of either PdRR8 or PdFERR in arr16arr17 resulted in an early-flowering phenotype. The number of rosette leaves at bolting in the PdRR8- and the PdFERR-complemented line was 14 and 15, respectively, which were all less than that of the arr16arr17 (Fig. 5b). The number of days from germination to flowering was also significantly different between the arr16arr17 and the complementary lines. Most of the WT and arr16arr17 plants set flowers at 31–40 days after germination, while the majority of the complemented lines flowered between 26 and 30 days after germination (Fig. 5c). PdRR8 had a more profound effect on promoting early flowering compared with PdFERR. A previous study reported that overexpression of PdFERR in A. thaliana led to stigma exsertion22, and this phenotype was also observed in the PdFERR_arr16/17 seedlings but not in the PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings. Moreover, overexpression of PdRR8 in the arr16/17 double-mutant resulted in a reduction in stamen numbers (Fig. 5d). While both complementary lines exhibited early flowering, the differential effects on stigma exsertion and stamen numbers suggested that PdRR8 and PdFERR might modulate flowering through different regulatory pathways.

a Early flowering phenotypes of PdRR8_arr16/17 (line 43) and PdFERR_arr16/17 (line 37). Scale bars represent 10 mm. b The number of rosette leaves at bolting. c Days from germination to flowering. Asterisks indicate a significant difference from the wild-type (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; two-sided Student’s t-test). d Representative floral phenotypes. The top two rows show the stigma exsertion observed in PdFERR_arr16/17 seedlings. Floral stages were defined according to Smyth et al.81. The bottom two rows display dissected flowers of WT, arr16arr17 double-mutant, and complementary transgenic seedlings. The line number in the bottom left corner indicates an independent transgenic line. Scale bars represent 500 µm.

Effects of PdRR8 on root global transcriptome in response to hydrostimulation

To investigate the global effects of PdRR8 on gene expression, root transcriptomic changes induced by hydrostimulation were analyzed for WT, arr16arr17, and PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings. With respect to the hydrotropic response, 2,500 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 872 up-regulated genes and 1,628 down-regulated genes, were discovered in WT (Fig. 6a and b); only 1,053 DEGs were identified in arr16/17, of which 329 were up-regulated and 724 were down-regulated (Fig. 6a and b); a total of 1,651 DEGs were detected in PdRR8-complementary line, of which 437 were up-regulated, 1,214 were down-regulated (Fig. 6a and b). Among the three comparison groups, DEGs of WT and PdRR8-complementary line shared the most genes in common (733), followed by that of WT and arr16arr17 (536) (Fig. 6a). Detailed information of the identified DEGs was listed in Supplementary Data 4.

a Venn diagram depicting the number of DEGs that response to hydrostimulation. b The total number of up- and down-regulated genes. c Gene ontology (GO) terms analysis of DEGs in three categories. d Enriched bubble chart showing the enrichment of the KEGG pathway. The size and color of each bubble represent the number of DEGs enriched in a particular pathway and Q-value, respectively. e Heatmap of MIZU-KUSSEI-like, MIZ1, and MIZ2 gene expressions. Each row represents a gene. Gene ID and annotation of each gene are shown at the right side.

To gain insights into their potential functions, GO and KEGG analyses were conducted for DEGs derived from each comparison. DEGs with annotated GO terms were classified into three major categories: cellular component, molecular function, and biological process. The statistically enriched (P < 0.05) GO terms in each category were shown in Fig. 6c. The three groups of DEGs exhibited overall similar distributions among the various GO terms. For all three comparisons, the top two terms were cell and cell part in the cellular component; the top two enriched terms were binding and catalytic activity in the molecular function category; and in the biological process category, DEGs were primarily enriched in cellular process, metabolic process, response to stimulus and biological regulation. Under each GO term, the number of DEGs in the PdRR8-complementary line was intermediate between those of the WT and the arr16arr17 double-mutant. Although enriched GO terms were fairly similar across the three groups of DEGs, different enrichment patterns of these DEGs were revealed by the KEGG enrichment analysis. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis was the most significantly enriched pathway of DEGs in WT. This was consistent with a previous study revealing that pathways involved in antioxidant metabolism, such as phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and glutathione metabolism, were vital for the hydrotropic response in Arabidopsis39. Compared with the WT, plant hormone signal transduction ranked first in both the arr16arr17 and the PdRR8-complementary lines, suggesting that genes related to phytohormone signal transduction were most affected by loss or gain of function of these type-A RR genes. Except for the MAPK signaling pathway, which was significantly enriched in all three comparisons, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes were the second most enriched pathway in the PdRR8-complementary line and the arr16arr17, respectively (Fig. 6d). To our knowledge, four hydrotropic mutants, namely mizu-kussei 1 (miz1), miz2, altered hydrotropic response 1 (ahr1), and no hydrotropic response 1 (nhr1) have been identified in Arabidopsis. MIZ1, which contains an uncharacterized DUF617 domain, is quite specific in regulating root hydrotropism40. MIZ2 encodes a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for ADP ribosylation factor and is also essential for positive hydrotropism41. Genes corresponding to the ahr1 and nhr1 mutants have not been cloned42. We characterized the expression of MIZ1, MIZ1-like proteins, and MIZ2 across the three comparisons. Under normal conditions, MIZ1 was weakly expressed in roots of WT, arr16arr17, and PdRR8_arr16/17 plants, while under hydrostimulation conditions, it was significantly up-regulated in WT and PdRR8_arr16/17 but maintained in arr16arr17 (Fig. 6e). Previous studies have revealed that MIZ1 can be dramatically induced by hydrostimulation41,43 and cytokinin treatment44. Therefore, we speculated that PdRR8 was able to rescue the expression level of MIZ1 in arr16arr17 mutants via partial or complete restoration of the cytokinin signaling pathway. Additionally, two MIZ1-like genes (AT5G65340 and AT1G76610) were specifically up-regulated in WT and arr16arr17, respectively. Meanwhile, MIZ2 was only slightly up-regulated in PdRR8_arr16/17.

Considering the early flowering phenomenon in PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings, we also compared the expression levels of floral organ development-related genes among WT, arr16arr17, and PdRR8_arr16/17 under normal conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4). Based on the above transcriptome data generated from root tissues, 12 genes were annotated as involved in the regulation of a variety of flower developmental processes. Intriguingly, all of these genes showed a significant increase in PdRR8_arr16/17 (Supplementary Fig. 4). The role of type-A RR genes in flowering time regulation remains largely unclear. The floral regulatory genes identified here may provide some information to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the promotion of flowering by overexpressing type-A RRs.

Conclusion

Tracking the evolutionary history of gene families can provide important information for understanding functional conservation or divergence among duplicated genes. Based on phylogenetic analysis, genome collinearity, and Ks-based molecular dating, we identified the type-A RR gene families and characterized their expansion manners, retention, and loss in five plant species (Arabidopsis, Populus, Carica, Vitis, and Oryza). Duplication of the type-A ARR members was associated only with the α-WGD event in Arabidopsis, while expansion of this gene family in Populus, Vitis, and Oryza occurred via both WGD and SSD events. By contrast, no paralogous type-A RR duplicates were detected in Carica. Biased retention and loss of type-A RR gene duplicates were observed in different lineages, with 10, 8, 5, 3, and 5 type-A RR genes derived from ancient WGDs being retained in Arabidopsis, Populus, Vitis, Carica, and Oryza, respectively. In Populus, two paralogous type-A RRs, PdRR8 and PdFERR, were identified to have originated from a dispersed duplication event that had occurred in the most recent common ancestor of the four modern rosids (Arabidopsis, Populus, Carica, and Vitis). The PdRR8 gene was highly expressed in the roots and leaves of poplar, while PdFERR was specifically expressed in the female floral buds. Additionally, the promoter activities of PdRR8 and PdFERR were most significantly decreased after cold and 6-BA treatment, respectively. Overexpression of either PdRR8 or PdFERR in the Arabidopsis arr16arr17 double-mutant indicated that only PdRR8 could complement the root hydrotropism deficiency of the mutant. Therefore, PdRR8, but not PdFERR, was a true functional ortholog of ARR16 and ARR17. These findings suggested that PdRR8 and PdFERR had exhibited differential expression patterns and might have, if not entirely, at least partially undergone functional divergence following the SSD event. Given the importance of PdFERR in poplar sex determination identified by previous studies, we speculated that its specialized roles may have been either lost in the other three analyzed rosid species or gained after their divergence from the last common ancestor.

Materials and methods

Identification of type-A RR gene family

The genome and protein sequences of Carica papaya v0.4, Vitis vinifera Genoscope 12X, and Oryza sativa v7.0 were obtained from Phytozome v1345, and the Populus deltoides genome and protein sequences were retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/GCA_014885025.1#/def22. To identify type-A RR genes in each genome, the protein sequences of 10 type-A ARR in A. thaliana46 were used as queries to perform BLASTP searches with an E-value cut-off <1e−10. Meanwhile, HMMER3.047 was also employed to find all potential type-A RR candidates containing the REC domain (PF00072). HMMER3.0 and BLASTP hits were combined and redundant sequences were removed. The remaining sequences were further filtered by Pfam48 and NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD)49, retaining only proteins featuring the REC domain, but lacking a DNA-binding domain. Finally, the obtained sequences were used to construct a phylogenetic tree with all three types of ARR proteins from A. thaliana46 using MEGA750. The genes clustered with the type-A ARR genes were defined as type-A RR homologs. The type-A RR homologous genes identified from the genome of P. deltoides, C. papaya, V. vinifera, and O. sativa were designated as type-A PdRRs, CpRRs, VvRRs, and OsRRs, respectively.

Gene duplication analysis and Ka/Ks calculation

Genome synteny and collinearity analyses within and between species were performed using MCScanX51. Intra- and inter-species collinear blocks containing the type-A RR genes were extracted from the ‘.collinearity’ files generated by MCScanX, and type-A RR paralogs and collinear orthologs were obtained. Duplication modes of the type-A RR paralogs were identified by the duplicate gene classifier within the MCScanX toolkit.

The MAFFT v752 and ParaAT2.053 were employed to perform sequence alignments of homologous genes (paralogs and orthologs). Then non-synonymous substitutions (Ka), synonymous substitutions (Ks), and Ka/Ks (ω) were calculated with KaKs_Calculator 2.054 based on the YN model55. To visualize the gene retention and expansion of the ancestral type-A RR genes associated with paleopolyploidy in the five plant species, a panoramic picture was established using the method described by Guo et al.56 with some modifications. Briefly, the type-A RR collinear orthologs and WGD/WGT-derived paralogs were classified into different COGs by integrating the gene-collinearity analyses within and between species, along with the Ks-based molecular dating of paleopolyploidy events. Members in each COG were arranged in a row on the diagram.

Phylogenetic relationship analysis and divergence time estimation

In order to generate a Bayesian time-scaled phylogenetic tree, a gene-species reconciled tree was first inferred according to the method developed by Song et al.57 with slight modifications. Briefly, all of the type-A RR genes from five species were aligned using two integrated sequence alignment tools, GUIDANCE 258 and TranslatorX59. After format conversion, the alignment was added to the configuration file for BEAST v2.560, which was used to produce a sample of gene family trees (20,000,000 generations, sampling every 1,000 generations). The GTR + I + G substitution model, the relaxed clock log-normal, and the Yule tree prior were used in the BEAST v2.5 analysis. Two independent runs were combined with 10% discarded as burn-in using the LogCombiner program in the BEAST v2.5 package. The inferred tree sample set and a dated species tree, which was downloaded from TimeTree61, were used as inputs for Amalgamated Likelihood Estimation (ALE)62. A type-A RR gene family tree embedded in the species tree was inferred with the ALE approach.

Estimation of gene divergence times was performed using the Bayesian relaxed clock method in BEAST v1.10.463. The sequence alignment file and the ALE-generated tree file were jointly imported into BEAST v1.10.4. The substitution model, the molecular clock model, the tree prior, the chain length, and the sampling frequency were set the same as those used for running BEAST v2.5. The aforementioned gene-species reconciled tree was employed as a user-specified starting tree. According to TimeTree61, the O. sativa diverged from the other four species approximately 159.6 Mya with a 95% confidence interval of 142.1-163.5 Mya. The time of monocot–dicot divergence was used to calibrate the root node, and a normal prior was chosen with the mean set to 152.8 Mya, the SD to 5.45, and offset 0. The ucld.mean was set to 0.000001–10 with a uniform prior64. Performance and accuracy of the beast output were analyzed by Tracer v1.7.2, ensuring that the effective sample size (ESS) of key parameters was more than 200. Finally, a maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree was summarized using TreeAnnotator v1.10.4 with a burn-in percentage of 10%. Phylogenetic analyses were also conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) algorithm with IQ-TREE65. All phylogenic trees were visualized using FigTree v1.4.366.

Expression pattern analysis of PdRR8 and PdFERR in poplar

Dormant branches were sampled from a 15-year-old Populus deltoides cultivated on the campus of Nanjing Forestry University (12932′69″N, 5632′06″E). Cuttings were prepared 15–20 cm long with at least two buds and further cultivated in water for 10 weeks in a greenhouse (22 °C, 40%–50% humidity, and 16-h light/8-h dark). Young leaves, barks, debarked stems, and roots were collected and immersed in liquid nitrogen. Flower buds were separately sampled from a male and a female P. deltoides at two time points: June 30 and August 15. The floral bract scales were removed before being frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were stored at −80 °C for further use.

For each sample, total RNA was extracted by using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (TIANGEN, China), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized by using the FastKing gDNA Dispelling RT SuperMix (TIANGEN, China). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, United States) on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, United States). The ubiquitin gene was chosen as an internal control67, and primers were listed in Supplementary Data 5. Three independent replicates were performed for each sample, and relative expression levels were calculated with the 2−ΔCT method68. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 26 software (IBM Corp., United States).

Promoter activity analysis of the PdRR8 and PdFERR

A 2-kb fragment upstream of the first exon of PdRR8 or PdFERR was amplified from the P. deltoides genome and fused to the GUS gene of the pKGWFS7.1 vector to generate pPdRR8::GUS or pPdFERR::GUS. The 35S dual promoter cloned from pBI121 was used as the positive control. The resultant constructs were separately transformed into N. tabaccum using the Agrobacterium-mediated method, and T1 transgenic tobacco seedlings were screened on solid media containing 100 mg/L kanamycin in combination with GUS staining.

To examine the promoter activities of the PdRR8 and PdFERR in response to signaling molecules and environmental stress, 4-week-old transgenic tobacco plants harboring the PdRR8::GUS or PdFERR::GUS construct were subjected to four different phytohormone treatments and six different abiotic stress treatments. Transgenic tobacco harboring 35S::GUS (positive control) and wild-type (negative control) plants were also treated in parallel. For signaling molecule treatments, transgenic tobacco plants were sprayed with 100 μM abscisic acid (ABA), 100 μM gibberellic acid (GA3), 100 μM salicylic acid (SA), and 100 μM 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA), respectively, and control plants were sprayed with distilled water. The salinity and drought treatments were conducted according to the methods described by Zhang et al.69. Whole transgenic tobacco seedlings were incubated in liquid 1/2 MS containing 200 mM NaCl, or 20% (w/v) PEG 6000, respectively. In addition, transgenic tobacco leaves were sprayed with 200 mM NaCl, or 20% (w/v) PEG 6000, respectively. The control plants were grown in liquid 1/2 MS and leaves were sprayed with 1/2 MS. For the low and high temperature treatments, tobacco seedlings were maintained in a growth cabinet at 4 °C or 42 °C, respectively. For the dark treatment, tobacco seedlings grown under 16 h/8 h (light/dark) were transferred to continuous darkness. For the mechanical wounding treatment, the tobacco leaves were pricked 15 times with a sterile scalpel. The leaves of transgenic tobacco and WT plants were used for GUS histochemical staining after 24 h treatment. All experiments were repeated three times.

GUS staining was performed following the procedure described by Jefferson et al.70. Tobacco leaf discs were obtained using a hole punch (1 cm in diameter) and were immediately incubated with GUS staining solution (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mM X-Gluc and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 37 °C for 24 h. All samples were then decolorized with 70% ethanol and photographed using an SZX10 stereomicroscope (Olympus, Japan).

Complementation of the Arabidopsis arr16arr17 double-mutant

The HindIII-SmaI and EcoRI-SacI fragments of pBI121 (AF485783.1), containing the CMV35S promoter and Nos terminator respectively, were sequentially cloned into the corresponding sites of pCAMBIA2301 (AF234316), and the resulting expression vector was named as p2301-35S plus. The ORFs of PdRR8 (EVM0036439) and PdFERR (EVM0009215) were cloned and separately inserted between the BamHI and KpnI sites of the p2301-35S plus by using pEASY-Uni Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (Transgen Biotech, China). All PCR reactions were performed using PrimeSTAR® GXL Premix (Takara, China) according to the user manual and primers were listed in Supplementary Data 5. The obtained constructs, designated as 35S::PdFERR_p2301-35Splus and 35S::PdRR8_p2301-35Splus respectively, were separately introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using the freeze-thaw method71. Wild-type plants of Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia-0 and Arabidopsis arr16/17 double-mutant (kindly provided by Prof. Jianru Zuo, the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Science) were transformed using the flower dipping method72. Transgenic plants were screened by kanamycin (50 mg/L) and further propagated by self-pollination to obtain T4 generation homozygous lines. The obtained transgenic seedlings overexpressing PdRR8 or PdFERR in arr16arr17 background were named as PdRR8_arr16/17 or PdFERR_arr16/17, respectively.

Root hydrotropism assay

A. thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as wild-type (WT). Seeds of WT, arr16arr17 double-mutant and six T4 transgenic lines (three PdRR8_arr16/17 lines and three PdFERR_arr16/17 lines) were surface-sterilized using 70% ethanol for 30 s and 4% NaClO solution for 10 min, and germinated on a half-strength Murashige and Skoog media (1/2 MS) agar (1% w/v) plates supplemented with 1% (w/v) sucrose (pH 5.8). All seeds were vernalized in a 4 °C refrigerator for 3 days to ensure uniform germination.

Hydrotropism assays were performed using a combination of methods described by Miao et al.39 and Chang et al.20. Agar-based medium containing 1/2 MS was poured onto a plastic square dish (90 × 90 mm2). After solidification, one-half of the medium was cut with a sterile scalpel at an angle of 54°. The right bottom part was removed and replaced with 1/2 MS supplemented with 800 mM D-sorbitol. Four-day-old sterile seedlings with 5-mm long roots were transferred to the hydrostimulating medium with root tips located 5 mm above the junction. The plates were placed vertically with the root tips pointing down and kept in a growth chamber at 22 °C with 24 h light. After 16 h of hydrostimulation, the root tips were imaged using a stereomicroscope), and the root growth curvatures (Supplementary Fig. 5) were measured using Image-Pro® Plus v 6.073. In addition, root tips were stained with 25 ng/mL propidium iodide (PI) solution for 2 min at room temperature and imaged using an LSM710 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). WT seedlings placed on split-agar medium with 1/2 MS-1/2 MS and WT seedlings placed on the hydrostimulating medium were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and analysis

The 5-mm-long root tips of wild-type, arr16arr17 double-mutant, and PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings under both normal and hydrostimulation conditions were separately harvested for transcriptomic analysis. Total RNA was isolated and cDNA was synthesized according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Six cDNA libraries were prepared, including WT-ck (wild-type seedlings grown in the control system), arr16/17-ck (arr16arr17 double-mutants grown in the control system), PdRR8_arr16/17-ck (PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings grown in the control system), WT-hyd (wild-type seedlings grown in the hydrotropic experimental system), arr16/17-hyd (arr16/17 double-mutants grown in the hydrotropic experimental system), and PdRR8_arr16/17-hyd (PdRR8_arr16/17 seedlings grown in the hydrotropic experimental system). All libraries were sequenced using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform with paired-end mode performed by Genepioneer Biotechnologies Company. Raw reads were firstly filtered through in-house Perl scripts to remove adapters and low-quality reads, and high-quality clean reads were mapped to the A. thaliana TAIR10 reference genome using HISAT274. Transcript abundance levels were estimated by FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) method75. Differential expression analysis was performed using the R Bioconductor package DESeq76. Gene annotations were obtained from Swiss-Prot (http://www.expasy.ch/sprot), GO (http://www.geeontology.org), KEGG, COG/KOG (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and NR (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Gene Ontology (GO) classifications were implemented by the GOseq R packages based on hypergeometric distribution77. KEGG pathways were extracted by KOBAS software78. All heat maps were generated by using Cluster 3.0 software79 and viewed using Java Treeview80.

Statistics and reproducibility

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test (Fig. 3a and Fig. 4e) and two-sided Student’s t-test (Fig. 4b, Fig. 5b and Fig. 5c). To ensure reproducibility, each experiment included a minimum of three biological replicates, with detailed descriptions of these replicates provided in the corresponding figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

RNA-seq data have been archived in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the study accession number PRJNA1168070. The source data underlying graphs and analytical data are available on Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27174795. Other data are provided in the manuscript or Supplementary Data.

References

Kondrashov, F. A. Gene duplication as a mechanism of genomic adaptation to a changing environment. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 5048–5057 (2012).

Magadum, S. et al. Gene duplication as a major force in evolution. J. Genet. 92, 155–161 (2013).

Hakes, L. et al. All duplicates are not equal: the difference between small-scale and genome duplication. Genome Biol. 8, R209 (2007).

Panchy, N., Lehti-Shiu, M. & Shiu, S. H. Evolution of gene duplication in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 2294–2316 (2016).

Carretero-Paulet, L. & Fares, M. A. Evolutionary dynamics and functional specialization of plant paralogs formed by whole and small-scale genome duplications. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 3541–3551 (2012).

Kuzmin, E., Taylor, J. S. & Boone, C. Retention of duplicated genes in evolution. Trends Genet 38, 59–72 (2022).

Birchler, J. A. & Yang, H. The multiple fates of gene duplications: Deletion, hypofunctionalization, subfunctionalization, neofunctionalization, dosage balance constraints, and neutral variation. Plant Cell 34, 2466–2474 (2022).

Qiao, X. et al. Gene duplication and evolution in recurring polyploidization–diploidization cycles in plants. Genome Biol. 20, 38 (2019).

Lee, T. H., Tang, H., Wang, X. & Paterson, A. H. PGDD: a database of gene and genome duplication in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D1152–D1158 (2013).

Blanc, G. & Wolfe, K. H. Widespread paleopolyploidy in model plant species inferred from age distributions of duplicate genes. Plant Cell 16, 1667–1678 (2004).

Maere, S. et al. Modeling gene and genome duplications in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 102, 5454–5459 (2005).

Pils, B. & Heyl, A. Unraveling the evolution of cytokinin signaling. Plant Physiol. 151, 782–791 (2009).

D’Agostino, I. B., Deruère, J. & Kieber, J. J. Characterization of the response of the Arabidopsis response regulator gene family to cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 124, 1706–1717 (2000).

Lu, J., Wei, S., Yin, T. & Chen, Y. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the molecular evolution and expression of type-A response regulator genes in Populus deltoides. Ind. Crop Prod. 194, 116336 (2023).

Ren, B. et al. Genome-wide comparative analysis of type-A Arabidopsis response regulator genes by overexpression studies reveals their diverse roles and regulatory mechanisms in cytokinin signaling. Cell Res. 19, 1178–1190 (2009).

To, J. P. et al. Type-A Arabidopsis response regulators are partially redundant negative regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 16, 658–671 (2004).

Salomé, P. A., To, J. P., Kieber, J. J. & McClung, C. R. Arabidopsis response regulators ARR3 and ARR4 play cytokinin-independent roles in the control of circadian period. Plant Cell 18, 55–69 (2006).

Müller, B. & Sheen, J. Cytokinin and auxin interaction in root stem-cell specification during early embryogenesis. Nature 453, 1094–1097 (2008).

Wohlbach, D. J., Quirino, B. F. & Sussman, M. R. Analysis of the Arabidopsis histidine kinase ATHK1 reveals a connection between vegetative osmotic stress sensing and seed maturation. Plant Cell 2, 1101–1117 (2008).

Chang, J. et al. Asymmetric distribution of cytokinins determines root hydrotropism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Res. 29, 984–993 (2019).

Müller, N. A. et al. A single gene underlies the dynamic evolution of poplar sex determination. Nat. Plants 6, 630–637 (2020).

Xue, L. et al. Evidences for a role of two Y-specific genes in sex determination in Populus deltoides. Nat. Commun. 11, 5893 (2020).

Yang, W. et al. A general model to explain repeated turnovers of sex determination in the Salicaceae. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 968–980 (2021).

Tang, H. et al. Unraveling ancient hexaploidy through multiply-aligned angiosperm gene maps. Genome Res. 18, 1944–1954 (2008).

Ramírez-Carvajal, G. A., Morse, A. M. & Davis, J. M. Transcript profiles of the cytokinin response regulator gene family in Populus imply diverse roles in plant development. N. Phytol. 177, 77–89 (2008).

Jiao, Y., Li, J., Tang, H. & Paterson, A. H. Integrated syntenic and phylogenomic analyses reveal an ancient genome duplication in monocots. Plant Cell 26, 2792–2802 (2014).

Tatusov, R. L., Koonin, E. V. & Lipman, D. J. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278, 631–637 (1997).

Vanneste, K., Baele, G., Maere, S. & Van de Peer, Y. Analysis of 41 plant genomes supports a wave of successful genome duplications in association with the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. Genome Res. 24, 1334–1347 (2014).

Dai, X. et al. The willow genome and divergent evolution from poplar after the common genome duplication. Cell Res. 24, 1274–1277 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 106, 3853–3858 (2009).

Dolinski, K. & Botstein, D. Orthology and functional conservation in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 465–507 (2007).

Altenhoff, A. M., Studer, R. A., Robinson-Rechavi, M. & Dessimoz, C. Resolving the ortholog conjecture: orthologs tend to be weakly, but significantly, more similar in function than paralogs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002514 (2012).

Kiba, T., Yamada, H. & Mizuno, T. Characterization of the ARR15 and ARR16 response regulators with special reference to the cytokinin signaling pathway mediated by the AHK4 histidine kinase in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 1059–1066 (2002).

Lynch, M. & Conery, J. S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science 290, 1151–1155 (2000).

Kaltenegger, E., Leng, S. & Heyl, A. The effects of repeated whole genome duplication events on the evolution of cytokinin signaling pathway. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 76 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. FRUITFULL-like genes regulate flowering time and inflorescence architecture in tomato. Plant Cell 34, 1002–1019 (2022).

Cho, L. H., Yoon, J., Pasriga, R. & An, G. Homodimerization of Ehd1 is required to induce flowering in rice. Plant Physiol. 170, 2159–2171 (2016).

Wu, L. et al. Involvement of cytokinin response regulator RhRR1 in the control of flowering. Acta Physiol. Plant 41, 121 (2019).

Miao, R. et al. Comparative analysis of Arabidopsis ecotypes reveals a role for brassinosteroids in root hydrotropism. Plant Physiol. 176, 2720–2736 (2018).

Kobayashi, A. et al. A gene essential for hydrotropism in roots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 4724–4729 (2007).

Miyazawa, Y. et al. A molecular mechanism unique to hydrotropism in roots. Plant Sci. 177, 297–301 (2009).

Miyazawa, Y. & Takahashi, H. Molecular mechanisms mediating root hydrotropism: what we have observed since the rediscovery of hydrotropism. J. Plant Res. 133, 3–14 (2020).

Yuan, W. et al. The asymmetric ABA response on both sides of root tip is important for tomato root hydrotropism by mediating proton efflux and cell elongation. bioRxiv 14, 2022–03 (2022).

Moriwaki, T. et al. Hormonal regulation of lateral root development in Arabidopsis modulated by MIZ1 and requirement of GNOM activity for MIZ1 function. Plant Physiol. 57, 1209–1220 (2011).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1178–D1186 (2012).

Schaller, G. E., Kieber, J. J. & Shiu, S. H. Two-component signaling elements and histidyl-aspartyl phosphorelays. Arabidopsis Book 6, e0112 (2008).

Finn, R. D., Clements, J. & Eddy, S. R. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W29–W37 (2011).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: the protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D412–D419 (2021).

Marchler-Bauer, A. et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D225–D229 (2011).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, e49 (2012).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Zhang, Z. et al. ParaAT: a parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 419, 779–781 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinf. 8, 77–80 (2010).

Yang, Z. & Nielsen, R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 32–43 (2000).

Guo, L. et al. Differential retention and expansion of the ancestral genes associated with the paleopolyploidies in modern rosid plants, as revealed by analysis of the extensins super-gene family. BMC Genomics 15, 612 (2014).

Song, J. et al. Integrated pipeline for inferring the evolutionary history of a gene family embedded in the species tree: a case study on the STIMATE gene family. BMC Bioinforma. 18, 439 (2017).

Sela, I., Ashkenazy, H., Katoh, K. & Pupko, T. GUIDANCE2: accurate detection of unreliable alignment regions accounting for the uncertainty of multiple parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W7–W14 (2015).

Abascal, F., Zardoya, R. & Telford, M. J. TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W7–W13 (2010).

Bouckaert, R. et al. BEAST 2.5: An advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006650 (2019).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Suleski, M. & Hedges, S. B. TimeTree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812–1819 (2017).

Szöllõsi, G. J. et al. Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Syst. Biol. 62, 901–912 (2013).

Baele, G. et al. Improving the accuracy of demographic and molecular clock model comparison while accommodating phylogenetic uncertainty. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 2157–2167 (2012).

Schuster, T. M., Setaro, S. D. & Kron, K. A. Age estimates for the buckwheat family Polygonaceae based on sequence data calibrated by fossils and with a focus on the amphi-pacific Muehlenbeckia. PLoS One 8, e61261 (2013).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Rambaut, A. FigTree 1.4.3—a graphical viewer of phylogenetic trees and a program for producing publication-ready Fig.s. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (2006).

Brunner, A. M., Yakovlev, I. A. & Strauss, S. H. Validating internal controls for quantitative plant gene expression studies. BMC Plant Biol. 4, 14 (2004).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Zhang, H. et al. Identification of a 467 bp promoter of maize phosphatidylinositol synthase gene (ZmPIS) which confers high-level gene expression and salinity or osmotic stress inducibility in transgenic tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 42 (2016).

Jefferson, R. A., Kavanagh, T. A. & Bevan, M. W. GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6, 3901–3907 (1987).

Chen, H., Nelson, R. S. & Sherwood, J. L. Enhanced recovery of transformants of Agrobacterium tumefaciens after freeze-thaw transformation and drug selection. Biotechniques 16, 664–668, 670 (1994).

Zhang, X. et al. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 1, 641–646 (2006).

Abràmoff, M. D., Magalhães, P. J. & Ram, S. J. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int 11, 36–42 (2004).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14 (2010).

Mao, X., Cai, T., Olyarchuk, J. G. & Wei, L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21, 3787–3793 (2005).

de Hoon, M. J., Imoto, S., Nolan, J. & Miyano, S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics 20, 1453–1454 (2004).

Page, R. D. TreeView: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12, 357–358 (1996).

Smyth, D. R., Bowman, J. L. & Meyerowitz, E. M. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2, 755–767 (1990).

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD2201100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32071795), and the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (21KJA220001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M.Y., Y.N.C. and J.L. conceived and designed the research. J.L. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. J.L., Y.N.C. and T.M.Y. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Ethan Baldwin and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jose Estevez and Aylin Bircan, David Favero. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, J., Chen, Yn. & Yin, Tm. Expression and functional divergence of a type-A response regulator paralog pair formed by dispersed duplication during Populus deltoides evolution. Commun Biol 7, 1367 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07091-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07091-8