Abstract

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, with poorly known consequences for wildlife. In December 2021, an atmospheric river brought record-shattering amounts of rain and snow to interior Alaska, creating conditions expected to cause mass mortality in grazing ungulate populations that need to access ground forage. We characterized snowpack conditions following the storm and used a 36-year monitoring dataset to quantify impacts on caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and their primary predator, wolves (Canis lupus). December precipitation was 7.3 SD above the 99-year mean and 2.5-fold higher than the prior record, with a return period of 333 years. However, ice thickness within the snowpack was highly variable across vegetation types, and caribou shifted to use higher elevations that can blow free of snow. Caribou and wolf mortality rates were 1.3–1.8 SD above normal and caribou population growth rates were low but similar to recent years, indicating a surprisingly weak demographic response. These findings indicate that landscape diversity may bolster resistance of wildlife populations to short-term, potentially devastating effects of extreme weather.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global temperatures rise, precipitation regimes are rapidly changing1. These changes are particularly consequential at high latitudes where the dynamics of the snowpack play an outsized role in the global hydrological system and biodiversity conservation2,3,4. Future shifts in snow regimes are difficult to predict due to complex interactions between precipitation and temperature, but extreme weather events are expected to increase in frequency5. These extreme “pulse” events may affect ecosystems and wildlife populations more strongly than gradually shifting mean conditions, or “presses”,5,6,7 but documenting the consequences of pulse events is difficult due to their relative rarity. For example, rain-on-snow events have led to occasional die-offs of large mammalian grazers such as reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) and muskox (Ovibos moschatus) by creating “locked pastures,” where forage is inaccessible below a thick ice layer4,8,9,10. The frequency of these events has been shown to alter population trajectories of well-studied reindeer populations in the high Arctic11, but far less is known about impacts of extreme weather on wildlife in more complex ecosystems. Biodiversity can increase the resistance of communities to changes induced by extreme climate events12, but the role of landscape diversity in buffering the impacts of these events on wildlife populations remains a key source of uncertainty in understanding climate change impacts.

Mountainous ecosystems represent one fifth of the earth’s land surface and harbor unique wildlife communities that contribute substantially to biodiversity and cultural heritage around the world13. These ecosystems are characterized by heterogeneity in topography and vegetation that could buffer the impacts of extreme weather by increasing the spatial variability of meteorological conditions, potentially creating pockets of refugia for resident wildlife14,15,16. If so, wildlife communities in mountainous regions should be more resistant to disturbances like extreme climate events than communities in more homogeneous landscapes.

A climate feature that is increasingly disruptive in a warming world is an atmospheric river, which is a long, narrow band of moisture that funnels water vapor from the tropics. Atmospheric rivers release heavy precipitation when they make landfall, and warmer air temperatures can increase the intensity of these events because greater volumes of moisture can be transported17. Here, we use meteorological models and satellite remote sensing to show how an atmospheric river created extreme weather conditions in interior Alaska during late December 2021, which included record-breaking snowfall and a major rain-on-snow event. We then quantify heterogeneity in resulting snow conditions on the ground using stratigraphy data from hundreds of snow pits in Denali National Park and Preserve (hereafter, “Denali”). Finally, we use a 36-year monitoring dataset to compare the movements and demography of caribou (Rangifer tarandus) and wolves (Canis lupus) after the 2021 storm to typical patterns.

Denali is bisected by the Alaska Range, and this atmospheric river event created an ideal opportunity to document how large mammals were affected by extreme weather conditions in a mountainous region. Caribou are culturally and ecologically important in northern regions, and their ability to access vegetation on the ground during winter is critical to their survival18. If landscape heterogeneity buffers the effects of extreme winter weather on caribou by creating pockets of refugia, we expected the range use by caribou to shift away from areas that received the most rain (which were expected to have thicker ice layers) and towards areas of shallower snow where forage would be easier to access. If so, caribou in Denali could have a relatively weak demographic response compared to ungulate population responses in the high Arctic following extreme rain-on-snow events, where relatively homogenous landscapes can lead to adverse conditions throughout entire herd ranges10,19,20. We would also expect the survival and reproductive rates of wolves, their primary predator, to temporarily increase due to increased prey vulnerability21,22.

Results

Storm characteristics

Storms in late December 2021 brought an unprecedented amount of snow and rain to interior Alaska. The top ten winter (November to April) rainfall events in Fairbanks from 1979-2013 reported in Bieniek et al.23 were all associated with atmospheric rivers, but the December 2021 event occurred much farther west in the Pacific Ocean than prior ones (Fig. 1a). This westerly atmospheric river led to record-breaking winter rainfall in interior Alaska: the Fairbanks airport station reported 49 mm on 26 December 2021, nearly four times greater than the prior record of 12.7 mm on 22 November 2010 (Fig. 1b). The airport’s maximum daily temperature was 5 °C on 26 Dec 2021, representing a 15 °C temperature anomaly and far surpassing the 1.1 °C maximum recorded on 22 Nov 2010. Thus, the magnitude and warmth of the storm were both extreme.

a Precipitable water (kg/m2) over North America on 26 December 2021 shows an atmospheric river (pink) with an extent far west of the typical path, causing the storm to strike northwest of the Alaska Range. b Accumulated precipitation on 26 December 2021 shows the highest precipitation totals occurred in interior Alaska. Daily composite data from the North American Regional Reanalysis was obtained from the NOAA/ESRL Physical Science Division, Boulder Colorado (https://psl.noaa.gov/).

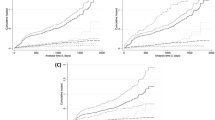

Meteorological records from the Denali Park Headquarters spanning a 99-year period (water years 1924-2022) showed that snow depth on 1 January 2022 (immediately following the storm) was 147 cm, which was four times greater than the average depth of 36.7 cm (SD = 25.6), representing 4.3 standard deviations above the mean (Fig. 2a, b). Using the General Extreme Value distribution, the return period for snow this deep was estimated to be 143 years (Supplementary Fig. 1, Text S1). Total December precipitation (220 mm) shattered previous records at 7.3 SD above the mean (Fig. 2c, d), with a return period of 333 years. The climatological normals (1991–2020) for December snowfall and precipitation totals at this site are 31 cm and 21 mm, respectively (i.e., 6.4 times and 10.5 times lower). This type of precipitation was more characteristic of an extreme rainfall event during summer than a mid-winter rain-on-snow event.

a, b Snow depth on 1 January (cm) and (c, d) total December precipitation (mm) are shown. Water years were ordered from low to high values in a and c, with the top 3 years labeled, and corresponding time series are shown in b and d. For both snow depth and precipitation, water year 2022 (corresponding to the December 2021 storm year) was the most extreme year in the 99-year weather record. Horizontal grey lines show the average (solid) and 1–7 standard deviations (SD, dashed) above the mean.

Snowpack characteristics

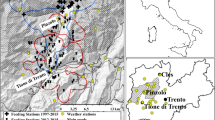

We used land surface modeling and passive-microwave remote sensing observations to delineate the rain-snow boundary and to estimate rainfall amounts throughout interior Alaska (Supplementary Fig. 2, Text S1). To characterize snowpack conditions on the ground following the storm, we excavated snow pits in forest, shrub, and tundra vegetation classes (n = 234 pits; Fig. 3). Rainfall amount during the December storm was a surprisingly poor predictor of ice thickness (Supplementary Table 1), and 36% of pits within the rain-affected area either lacked ice layers completely or had minimal (1 cm) ice present (Fig. 3). Total ice thickness was instead best explained by days since the storm, snow depth, and vegetation type (Supplementary Table 1). Ice thickness declined over time and increased with snow depth (Fig. 3). However, tundra sites had more ice than shrub or forest sites despite having shallower snowpacks (Supplementary Table 2). Tundra sites therefore had nearly double the amount of ice per cm snowpack compared to shrub sites (10.4% vs 5.4% ice) and nearly four times more ice per cm of snowpack than forest sites (10.4% vs 2.7% ice).

a Location of snow pits sampled in the Denali study area, Alaska USA. Color of circles indicates whether ice was present (yellow) or absent (blue), and size corresponds to the total thickness of ice in each pit. b Relationship between days since the peak rain-on-snow event (27 December 2021) and observed ice thickness in forest, shrub, and tundra sites. c Relationship between snow depth and observed ice thickness in forest, shrub, and tundra sites. Predicted effects and 95% confidence limits from a generalized linear mixed model are shown along with raw data points.

Responses of caribou and wolves

Caribou shifted away from heavily rained-on areas following the storm, entirely avoiding the area that received more than 15 cm of rain between 25–30 December (Fig. 4). The shift away from rain-affected areas brought caribou to higher elevations. Historically, caribou used elevations between 700–800 m in all three winter surveys (November, January, and March \(\bar{x}\) = 760 m, 776 m, 761 m, respectively; Fig. 4). Their pre-storm locations reflected this typical range use (November \(\bar{x}\) = 731 m, 95% CI = 692-770), but caribou used markedly higher elevations after the storm than they did historically (January \(\bar{x}\) = 918 m, 95% CI = 868-968; March \(\bar{x}\) = 1106 m, 95% CI = 1058–1154).

Maps show locations of radio-collared caribou (yellow dots) during aerial surveys occurring before the storm (a, Nov-Dec 2021, n = 57) and afterward (b, Jan 2022, n = 56; c, Mar 2022, n = 54). Historical range shows the region typically used by the herd, encompassing 95% of caribou locations from 2009–2021 during each survey period. The blue region received heavy rainfall ( > 15 cm during 25–30 Dec 2021) based on the LIS simulations; thus, in a, the rain had not yet occurred. Violin plots show the December 2021 rainfall amounts (d–f) and elevations (g–i) at caribou locations during the storm year (winter 2021-22, yellow) and in prior years (“historical”, grey), with means and 95% confidence intervals shown in the violin plots. Note the “historical” rainfall indicates the amount of rain from the December 2021 storm associated with locations that were historically used by caribou, as opposed to rainfall amounts in prior years (which were not available, and winter rainfall rarely occurred historically).

The caribou herd size in fall 2022 was estimated to be 1734 individuals, which was the lowest recorded but only 25% (1.3 SD) below the mean herd size of 2,311 (SD = 432, 1987–2022; Fig. 5a, b). The population growth rate (λ) from 2021 – 2022 was 0.84, which was the 3rd lowest on record and 1.6 SD below the mean λ of 1.0 (SD = 0.10, Fig. 5c, d). The annual mortality rate of adult female caribou from October 2021 – September 2022 was 0.22 (n = 43 radio-collared caribou), double the long-term average of 0.11 (SD = 0.07, 1987–2022) but lower than mortality rates during the previous two years (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Caribou calf recruitment in 2022 was the second lowest recorded (0.09) and substantially lower than the long-term average of 0.24 (SD = 0.11), but similar to recent years (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d).

a, b Caribou population size estimates, (c, d) caribou population growth rates, and (e, f) annual mortality rates of wolves from 1987 – 2022 in Denali National Park and Preserve (n = 36 years). Estimates were ranked in a, c, and e, with 2022 highlighted in red, and the corresponding time series are shown in b, d, and f. Horizontal lines show average rates (solid) and 1-2 standard deviations (SD, dashed) from the mean.

The movement rates of wolves decreased from an average of 342 meters per hour (95% CI = 282-403, n = 104 pack-days) before the storm to 221 m*hr-1 (95% CI = 186–256, n = 156) during the storm period, and then nearly doubled to 436 m*hr-1 (95% CI = 366-507, n = 112) after the storm (Fig. 6). Wolf pack sizes and recruitment rates were within the normal range in 2022: average pack size was 7 wolves in 2022 (n = 13 packs), identical to the long-term average of 7 (95% CI = 6.4-7.7), and average recruitment was 2.3 pups per pack in 2022, similar to the long-term average of 2.6 (95% CI = 2.25- 3.02). Contrary to expectations, the adult wolf mortality rate was 0.27 in 2022 (n = 42 radio-collared wolves), which was the highest rate on record and 1.8 SD higher than the long-term average of 0.17 (SD = 0.055; Fig. 5e, f).

Movement rates (meters per hour) of GPS-collared wolves are shown the week before the major storm (12–18 Dec 2021), during the storm (19–31 Dec 2021), and the week after the storm (1–7 Jan 2022). Data points represent average daily movement rates of each pack (n = 28 wolves in 13 packs over 25 days, 372 total pack-days). A smooth (loess) curve was fit to the data (blue line = average, grey ribbon = 95% confidence interval).

Discussion

Despite declining trends in average snow cover duration worldwide24, some regions of the Arctic are expected to have more precipitation, deeper snow, and more frequent rain-on-snow events in the future5,25. Exceptionally deep snow and major rain-on-snow events can strongly affect the dynamics of wildlife populations10,20, raising concerns that an increase in these extreme events threatens the future viability of large herbivores that are critical to the functioning of northern social-ecological systems26,27. Here, we documented highly heterogeneous snowpack conditions following a December storm that blanketed interior Alaska with record-breaking amounts of rain and snow (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for photos). Our findings support cautious optimism that impacts of extreme winter weather on large mammals are partially buffered by landscape heterogeneity in mountainous ecosystems, leading to pockets of relatively suitable conditions that can increase the resistance of wildlife populations to short-term catastrophic declines.

The December 2021 atmospheric river resulted in a “300-year” winter storm, with snow depths and precipitation levels that were estimated to occur every 150–300 years. For ungulates that need to access vegetation on the ground in winter, such as caribou, rain-on-snow events and deep snowpacks can block access to forage and cause major die-offs. For example, Miller and Gunn20 documented a 98% decline in Peary caribou from 1993 – 1998 in the Canadian high Arctic caused by three consecutive winters with snowfall amounts 2-3 SD above normal. Similarly, snow depth was 2 SD above normal during winter 2018 in Greenland, which led to near-complete reproductive failure in plants, birds, arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus), and muskox28. Effects of winter precipitation on reindeer have been extensively studied on Svalbard in the Norwegian high Arctic11,19, where a doubling of winter precipitation led to a 3.75-fold decrease in calf:cow ratios and a 7-fold increase in mortality rates29. In contrast, snow depth and total precipitation (including record-breaking rainfall) in Denali were 4–7 SD above normal, and although the caribou population size was the lowest in the 36-year record, it was only 25% below the long-term average, corresponding to 1.3 SD from normal. The extreme snow conditions created by the storm likely contributed to the caribou population decline from 2021–2022 via reduced adult survival and calf recruitment, but the population declined even more dramatically from 2019–2021 in the absence of an extreme weather event. Caution should be used when interpreting standard deviations of the precipitation values, since the time series was distributed non-normally. Compared to prior studies reporting these values, however, the December 2021 storm in interior Alaska was more “extreme” than prior cases documented in the Arctic, but the short-term effects on caribou were less dramatic. While numerous differences between these regions may alter the magnitude of effects, the heterogeneity in vegetation and topography in Denali that created surprisingly variable snowpack conditions likely played an important role.

Our ground surveys showed that the total amount of ice within the snowpack varied widely across the landscape and through the winter season. Rainfall amount was a poor predictor of ice thickness, contrary to expectations. Instead, ice thickness declined over time, was lower in areas with shallower snowpacks, and was strongly affected by vegetation type. Most notably, tundra sites had far higher ice content than shrub or forest sites despite generally having shallower snow depths. The physical structure of vegetation can have a major influence on snowpack dynamics through several mechanisms30. For example, canopy cover can reduce snow accumulation via interception, but ablation (loss of snow) is also reduced under canopy due to shading and protection from wind31,32. Open tundra offers little protection and fewer energetic inputs to decompose ice over time, and unimpeded wind tends create hard “wind slabs” that may be relatively difficult for rain to permeate33,34. Snow stratigraphy under vegetation is less wind-affected and far more variable than in the open35,36, leading to greater formation of preferential flow paths that route rain quickly to the ground before it can freeze37. We hypothesize that tree trunks and shrub branches create vertical channels that also facilitate rain percolation directly through the snowpack in forest and shrublands. The more homogeneous, wind-compacted snow cover in the tundra is more likely to allow rainwater time to pool, freeze, and create a continuous ice layer.

Through these diverse mechanisms, boreal forests may play an underappreciated role in mitigating the impacts of extreme winter weather on large grazers such as caribou. For example, the typical winter range of the Central Arctic caribou herd is comprised of tundra habitat north of the Brooks Range, but this herd uses forested habitat on the south side of the range during deep snow years38. Similarly, ice from rain-on-snow events is thicker in flatter low-lying sites on Svalbard19, and reindeer that avoided these sites by foraging at higher elevations had better body condition and higher fecundity and survival39,40. We found that caribou in Denali shifted their range use towards higher elevations, likely taking advantage of wind-swept ridges to access forage (Supplementary Fig. 4d). While the coarse resolution of the caribou location data precluded analysis of habitat selection, caribou may have also foraged in areas of shrub and forest cover that had little ice in the snowpack. Shrub and forest expansion due to climate warming are generally expected to reduce habitat quality for grazers such as caribou and improve habitat quality only for browsing mammals such as moose, Alces alces41,42, but the benefit of these habitats as refuges during harsh winters may offset some of these costs.

Habitat structure can thus buffer the impact of extreme weather on ungulates via altered snow conditions, but predation may also affect their sensitivity to extreme events. Ungulate populations tend to be more sensitive to harsh weather conditions when densities are near carrying capacity (i.e., when food is limiting), which is most likely to occur when predators are absent or rare. For example, a predator control program aiming to increase Dall sheep (Ovis dalli dalli) numbers was initially successful, but the sheep population crashed following a winter with deep, icy snow, whereas sheep did not decline in an adjacent site where predators were unmanipulated43. Likewise, reindeer on Svalbard do not have predators, and their responses to rain-on-snow events are stronger when population densities are high39,44. Caribou in Denali are subject to substantial levels of predation from an intact carnivore guild, and the herd is approximately half of its maximum recorded size in our contemporary time series (Fig. 5b) and far below the earliest estimate of 20,000 – 30,000 caribou recorded by Adolph Murie in 194145. Thus, the Denali herd is well below carrying capacity. By reducing the likelihood that ungulate population densities approach or exceed the nutritional capacity of their ranges, the presence of intact predator guilds may paradoxically help to buffer ungulate populations against severe declines as extreme climate events become increasingly frequent stressors.

We expected wolf survival and reproduction to increase following the storm, because their hunting success and population growth tends to increase during winters with deep snow when they have a relative movement advantage over their ungulate prey21,22. Contrary to expectations, wolf reproduction was unaffected, and survival was well below average following the extreme winter. We found that wolves responded to the December storms with a marked reduction in movement rates, but this behavioral response was unlikely to have reduced survival since it persisted for only two weeks. The high mortality rate in 2022 may have been related to the declining trend in caribou numbers that has occurred since 2020 (Fig. 5b), or to other factors; wolf mortality rates were highly stochastic over time (Fig. 5f). Effects of climatic conditions on higher trophic levels remain poorly understood46, but extreme climate events can affect carnivores more strongly than other trophic groups47. While our study focused on the short-term effects of an extreme climatic event, longer-term monitoring is needed to better understand the resilience of carnivore and ungulate populations to these disturbances and the potential for broader cascading effects48.

Conclusion

The climate is changing most rapidly in arctic and boreal regions, which harbor the vast majority of the world’s remaining intact faunal communities49. Thus, understanding climate change impacts in this region is especially important for biodiversity conservation. However, the weather station network is approximately an order of magnitude sparser in these northern regions compared to lower latitudes50, increasing the importance of remote sensing and modeling for quantifying the extent and magnitude of extreme weather events. We found that passive microwave observations overestimated the spatial extent of the rain-on-snow event, whereas the Land Information System (LIS) simulations underestimated its extent (Supplementary Fig. 2). Accurate partitioning of rain and snow is particularly challenging, especially in northern regions where many weather stations are unmanned and gauges can ice over, leading to unreliable measurements of winter precipitation51. Using a combination of approaches, as we did here, may therefore lead to the most accurate characterization of extreme weather events.

Climate projections generally indicate warmer, wetter winters will occur in arctic and boreal regions, which should result in deeper snow and more frequent rain-on-snow events in many regions5,9. The latest Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) climate projection model, CMIP6, projects a 422% increase in rainfall from 2000 – 2100 under a high emissions scenario, which is substantially greater than the 260% increase that was predicted by the prior version (CMIP5)52. Our study highlights the especially strong potential of atmospheric rivers for creating increasingly extreme snowpack conditions in the future, with substantial implications for northern social-ecological systems53. These conditions are especially consequential for wildlife when they occur in the fall, because difficult snowscapes can persist through winter and spring. For example, Cosgrove et al.54 found that fall snow depth was the strongest predictor of Dall sheep lamb survival the following summer (with deep snow reducing survival), and Sami reindeer herders report that warm, wet falls lead to difficult grazing conditions throughout winter and can lead to mass mortality events26,55,56. Because the majority of snowfall occurs prior to January in northern regions57, extreme winter weather is most likely to occur during this impactful early season. Our findings indicate the negative impacts of extreme fall and winter conditions on wildlife may be especially severe in regions with short-statured vegetation (e.g., tundra) and little topographic heterogeneity. Mountainous regions that harbor a diversity of habitat types, terrain, and intact faunal communities may thus be the most resilient and resistant in the face of extreme climate events.

Online methods

Characterizing the storm

General storm characteristics and extremity were derived from time series of precipitation and snow depth from weather stations in Fairbanks and Denali National Park, Alaska. Daily near-surface air temperature and precipitation data from the weather station at Denali Park Headquarters from 1923–2022 (63.7175°N, 148.9692°W, elev. 1923 m) and the Fairbanks International Airport station from 1929–2022 (64.80309°N, -147.87606°W, elev. 131 m) were retrieved from the Global Historical Climatology Network Daily database58. Because water years start October 1 of the prior calendar year, these time series represent water years 1924–2022 (99 years) in Denali and 1930–2022 (93 years) in Fairbanks. We used Matlab to conduct an extreme value distribution analysis of January 1 snow depth and total December precipitation using the 99-year Denali weather station data (Supplementary Data S1). We used the General Extreme Value distribution, which was recommended for analysis of precipitation in Alaska by NOAA59, to calculate probabilities of non-exceedance (i.e., probabilities of obtaining lower values) and corresponding average recurrence intervals, commonly known as return periods. Although the precipitation time series data was skewed, we also reported means and standard deviations to facilitate comparison with other studies of extreme precipitation events and wildlife responses, which typically reported magnitudes in terms of SD from the mean. The storm structure, including water vapor transport magnitude and direction, as well as precipitation extent, was examined using the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR)60, which combines atmospheric modeling with historic data assimilation. Characteristics of the December 2021 storm were compared to those of other heavy winter rainfall events noted by Bieniek et al.23 using NARR to examine water vapor transport and precipitation extent.

To estimate the spatial extent and amount of rainfall that occurred in Denali National Park, we used the NoahMP 4.0.1 land surface model61 driven by Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications V2 (MERRA-2) atmospheric reanalysis data62 in the Land Information System (LIS)63,64. Hereafter, we refer to these model runs as “LIS simulations.” We downscaled the 50 km resolution MERRA-2 forcing data to 3 km resolution in the Land Data Toolkit portion of the LIS framework, which generates the input files for the land surface model. Precipitation phase was determined via the mixed snow-rain partitioning scheme as seen in Jordan65. The partitioning scheme allows for fractional snow-rain amounts in the model as a function of air temperature. A lapse rate correction of 6.5 K*km-1 was enabled during the model run to account for the effect of elevation on air temperature. The initial snow water equivalent (SWE) outputs from the LIS simulations were found to be too high when compared to in-situ records from four weather stations (Fairbanks Airport, Denali Headquarters, Granite Creek SNOTEL, and Kantishna SNOTEL). We therefore scaled the cumulative SWE to match the in-situ SWE records on 1 January 2022. We used the average scaling factor across these weather stations (0.56) to bias-correct the total precipitation (rain + snow) in the subsequent LIS simulations. This was implemented as a direct multiplicative factor on the precipitation variables within NoahMP.

Because accurate partitioning of rain and snow is challenging66, we also mapped rain-on-snow during the December 2021 storm using passive microwave satellite remote sensing to detect liquid water on the snow surface. We used the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer 2 (AMSR2) Calibrated, Enhanced-Resolution Brightness Temperature (CETB) product67 and the algorithm described and calibrated by Pan et al.51 to map rain-on-snow using the Gradient Polarization Ratio, which relies on brightness temperature difference between two AMSR2 channels. We used the highest resolution CETB data: 3.125 km and 6.25 km for the 36.5 GHz and 18.7 GHz channels, respectively, at both polarizations. To compute the gradient polarization ratio at 3.125 km, we downscaled the 18.7 GHz data to match the resolution of the 36.5 GHz data. The downscaling was primarily to ease computations and had minimal impact on the final result when compared with using the 18.7 GHz data at its native 6.25 km resolution.

To evaluate the spatial accuracy of the modeled and remotely-sensed rain-on-snow maps, we obtained validation points from weather stations and residents who had first-hand knowledge of whether it rained or snowed at their residences during the storm (n = 21 points), and we determined the proportion of points that were correctly classified using each method. To evaluate the accuracy of modeled precipitation amounts, we conducted three validations. First, we compared daily time series from 1 Dec 2021 – 1 March 2022 of total precipitation (water content of rain plus snow) to precipitation from the four weather stations used to initially calibrate the LIS simulations (Supplementary Fig. 5), and we calculated the root mean squared error (RMSE). Second, we compared SWE and snow depth outputs from the LIS simulations to field measurements we obtained using a federal sampler at 7 locations between 4 February – 31 March 2022 (n = 6–75 measurements per site, 186 total). We compared the modeled SWE and snow depth to the averaged measurements at each of the 7 sites and calculated the RMSE. Third, we compared modeled snow depth to measurements from our snow pit sampling (described below; n = 234 pits) and calculated the RMSE. Validation results are reported in Supplementary Text S1.

Measuring snowpack characteristics

We excavated snow pits from 20 January – 25 March 2022 (following the December 2021 storm) as part of a concurrent study to assess snowpack properties associated with ungulate and carnivore tracks in the eastern portion of Denali68. Site selection followed a stratified quasi-random design in which the study area was roughly divided into four quadrants that sampling rotated among. Within each quadrant, the area was further stratified by three major habitat types: (1) open tundra, (2) forest, and (3) riparian areas dominated by tall ( > 1.3 m) shrubs (hereafter, “shrub” habitat). Fresh tracks of ungulates and carnivores were searched for in each habitat type, with the research team traveling by snowmobile or skis. Once fresh tracks were encountered, a pair of sites approximately 10 meters apart was selected for sampling. This paired design increased sampling efficiency and allowed fine-scale heterogeneity in snowpack properties to be quantified.

To characterize the snowpack at each site, a snow pit was excavated to ground level. Snow depth was measured at two ends of the pit face and averaged. Layers of the snowpack that differed in hardness were delineated using craft sticks, and the thickness of each layer was measured to the nearest centimeter. The hardness of each layer was indexed using the hand-hardness scale, which indicates which of five objects can be pushed into the layer with consistent and minimal force (from softest to hardest): a fist, 4 fingers, 1 finger, a pencil, or a knife69. We converted these categories to an ordinal scale ranging from 1 to 5. Knife hardness (5) was selected only for ice layers, allowing each ice layer and its corresponding depth and thickness to be delineated throughout the snowpack. Snow pit data have been archived at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory Distributed Active Archive Center70.

At each site, we recorded landscape covariates including vegetation type (tundra, forest, or shrub), slope, and elevation. We used a 30 m digital elevation model71 and the SpatialEco and terra packages in Program R72,73 to extract the Terrain Ruggedness Index (TRI), Topographic Position Index (TPI), and aspect values at each snow pit site. TRI is a metric of terrain heterogeneity based on relative elevational changes adjacent to a focal location, and it is widely used in species distribution modeling74. TPI uses similar elevation-based, cell-neighborhood computations, but instead indicates relative position of the site within the landscape’s topography75. TPI varies from valley bottom to ridge top, with intermediate values mid-slope. TPI and TRI were extracted at 150 m resolution.

To identify the primary factors affecting total ice layer thickness, we developed a generalized linear mixed model using covariates that measured topographic features (elevation, slope, aspect, TRI, TPI), features of the December 2021 storm (rainfall, snow depth, days since storm), and vegetation type (forest, shrub, or tundra). Aspect was cosine-transformed to convert from a circular distribution to linear along a north-south axis. Total rainfall from 25–30 December 2021 was obtained at 3.125 km resolution using the LIS simulations described above. Snow depth was obtained from the pit data. Days since storm was measured as the number of days elapsed since 27 December 2021, which was the day of heaviest precipitation in Denali (70 mm). Continuous variables were checked for collinearity, and all correlations were <0.7 (max r = −0.63 between elevation and rainfall, Supplementary Fig. 6). Continuous variables were centered and scaled. Nine covariates total were included in the model (Supplementary Table 1), and SiteID was included as a random effect to account for non-independence of paired pits. Because the response variable had a zero-inflated continuous distribution, we used a tweedie distribution and ran the model using the glmmTMB package in Program R76. Marginal effects of significant predictors were obtained while averaging across the other variables using the ggeffects R package77. Supplementary Code S1 and Data S2 provide the code and input data file for this model.

Responses of caribou and wolves to the extreme winter

The movements, survival, and reproductive success of caribou and wolves in Denali were monitored through radio-collaring and aerial tracking flights as part of long-term monitoring programs. Capture and handling of animals was conducted in accordance with approved protocols and permits (AK_DENA_Borg_Caribou_2020.A3, AKR_DENA_Borg_Wolves_2019.A3). Every March, 6–10 female caribou calves were fitted with VHF radio-collars to maintain an age-structured sample of 50–90 collared caribou for long-term monitoring. Aerial tracking surveys were conducted eight times per year, in late January, mid-March, early May, mid-May, early June, late July, late September, and late November. During each survey, locations of collared caribou were recorded along with estimated group sizes. Because VHF collars were located only eight times per year, caribou location data provided information about herd-level range selection rather than fine-scale movement information provided by GPS collars.

We expected areas that received greater amounts of rain would have thicker ice layers in the snowpack, because temperatures were well below freezing both before and after the rainfall (Supplementary Table 3) To understand how caribou movements may have changed after the major rain-on-snow event, we compared the rainfall amounts and elevations at areas used by caribou in winter 2021-22 with their historic use. We defined typical historic range use based on monthly utilization distributions derived from caribou locations in years 2009–2019. To characterize conditions across their typical range, we distributed 20 random locations for each used location in proportion to historic intensity of use, separately for each winter survey month (November, January, and March). We extracted elevation and total rainfall from the 25–30 December 2021 LIS simulations at the used and historic locations. If caribou avoided rained-on areas that they typically used in prior years (which lacked major rain-on-snow events), then average rainfall amounts at locations used after the storm should be lower than rainfall amounts associated with locations they used historically during the same survey months. Such a pattern would indicate that caribou used heavily rained-on areas less than expected based on their historical range selection. Likewise, if caribou used mountainous areas as refuges following the storm, their locations should have been at higher elevations after the storm than their typical range use during January – March (i.e., the post-storm period).

Wolf packs were monitored using satellite-linked GPS collars that recorded locations every 4 h of 1-2 wolves in each pack. Wolf activity may be sensitive to storms78, so we examined movement rates of wolves before, during, and after the December 2021 storm. Movement rates (meters per hour) were calculated for each collared wolf by measuring the Euclidean distance between successive locations and dividing by the 4-hour time interval79. Movement rates were averaged per wolf pack per day during the 27-day time period for this analysis, which included 7 days prior to the storm (12–18 Dec), the 13-day storm period of heavy snow and rain (19–31 Dec), and 7 days after the storm (1–7 Jan 2022). Supplementary Code S2 and Data S3 provide the code and input data file for these calculations.

Aerial surveys and data from radio-collared animals were used to estimate demographic rates of caribou and wolves. We estimated adult mortality rates of caribou and wolves, caribou calf recruitment and wolf reproduction, and caribou population sizes and growth rates. Wolf population sizes and growth rates were not estimated, because shifts in pack territories along the park boundary leads to a highly variable area monitored from year to year, resulting in variability in counts that are not likely due to actual population changes22. Caribou and wolf collars transmitted a mortality signal if the collar did not move for 8 or more hours, and annual mortality rates were estimated from the radio-collared sample as the proportion of collared animals that died from October in year t-1 through September in year t. Wolf mortality rates may be biased low because resident breeders are typically collared22, but this bias should be consistent across years. Collared caribou are a representative age-structured sample that should limit bias in estimates of mortality rates. Wolf packs were located by aerial tracking flights throughout the year, and the size of packs and number of pups were recorded. During the caribou tracking surveys in mid-May, early June, and late September, composition data was collected in addition to locations of collared caribou, whereby individuals in each group were classified as calves ( < 1 year old), cows (females ≥ 1 year old), or bulls (males ≥ 1 year old). The number of calves born each year were estimated from the mid-May survey during the peak of calving, and calf recruitment was calculated as the calf estimate from the late September survey (after most calf mortality has occurred) divided by the number born. The total number of caribou in the herd each fall was estimated using survey data adjusted for detectability and survival of radio-collared animals as follows:

where Cowtotal = total number of cows (collared and uncollared) detected in the June survey, Surv = proportion of collared cows surviving from June to September, Pdet = proportion of collared cows detected in the June survey, and Ppop = proportion of the total caribou count from the September survey comprised of cows. Additional details about caribou and wolf monitoring procedures are available in published protocols80,81. Demographic time series data for caribou and wolves are provided in Supplementary Data S4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Numerical source data underling the graphs shown in the manuscript is provided in the Supplementary Materials. Time series data for precipitation (Fig. 2) are available in Supplementary Data S1. Snow pit data (Fig. 3) are available in Supplementary Data S2 and here: https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/2188. Time series data for wildlife demography (Fig. 5) are available in Supplementary Data S4. Wolf movement data (Fig. 6) are available in Supplementary Data S3. Daily meteorological data from the Denali Headquarters weather station is publicly available for download here: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/cdo-web/datasets/GHCND/stations/GHCND:USC00505778/detail.

Code availability

Custom R code for the snow pit data analysis is available as Supplementary Code S1, and code for the wolf movement rate calculations is available as Supplementary Code S2. Code and associated input files are also available on GitHub: https://github.com/bsullender/DenaliStorm/ .

References

Bormann, K. J., Brown, R. D., Derksen, C. & Painter, T. H. Estimating snow-cover trends from space. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 924–928 (2018).

Niittynen, P., Heikkinen, R. K. & Luoto, M. Snow cover is a neglected driver of Arctic biodiversity loss. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 997–1001 (2018).

Wrzesien, M. L. et al. A new estimate of North American mountain snow accumulation from regional climate model simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1423–1432 (2018).

Descamps, S. et al. Climate change impacts on wildlife in a High Arctic archipelago - Svalbard, Norway. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 490–502 (2017).

Walsh, J. E. et al. Extreme weather and climate events in northern areas: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 209, 103324 (2020).

Harris, R. M. B. et al. Biological responses to the press and pulse of climate trends and extreme events. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 579–587 (2018).

Greenville, A. C., Wardle, G. M. & Dickman, C. R. Extreme climatic events drive mammal irruptions: regression analysis of 100-year trends in desert rainfall and temperature. Ecol. Evol. 2, 2645–2658 (2012).

Stien, A. et al. Icing events trigger range displacement in a high-arctic ungulate. Ecology 91, 915–920 (2010).

Hansen, B. B. et al. Warmer and wetter winters: characteristics and implications of an extreme weather event in the High Arctic. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 114021 (2014).

Putkonen, J. et al. Rain on snow: little understood killer in the north. Eos, Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 90, 221–222 (2009).

Hansen, B. B. et al. Spatial heterogeneity in climate change effects decouples the long-term dynamics of wild reindeer populations in the high Arctic. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3656–3668 (2019).

Isbell, F. et al. Biodiversity increases the resistance of ecosystem productivity to climate extremes. Nature 526, 574–U263 (2015).

Price, M. Mountains: globally important ecosystems. Unasylva 49, 3–10 (1998).

Nellemann, C. & Thomsen, M. G. Terrain ruggedness and caribou forage availability during snowmelt on the Arctic Coastal Plain, Alaska. Arctic 47, 361–367 (1994).

Nellemann, C. & Reynolds, P. E. Predicting late winter distribution of muskoxen using an index of terrain ruggedness. Arct. Alp. Res. 29, 334–338 (1997).

Poley, L. G., Magoun, A. J., Robards, M. D. & Klimstra, R. L. Distribution and occupancy of wolverines on tundra, northwestern Alaska. J. Wildl. Manag. 82, 991–1002 (2018).

Ralph, F. M. et al. Atmospheric rivers emerge as a global science and applications focus. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 98, 1969–1973 (2017).

Joly, K., Wasser, S. K. & Booth, R. Non-invasive assessment of the interrelationships of diet, pregnancy rate, group composition, and physiological and nutritional stress of barren-ground caribou in late winter. PLoS One 10, e0127586 (2015).

Hansen, B. B., Aanes, R., Herfindal, I., Kohler, J. & Saether, B.-E. Climate, icing, and wild arctic reindeer: past relationships and future prospects. Ecology 92, 1917–1923 (2011).

Miller, F. L. & Gunn, A. Catastrophic die-off of Peary caribou on the western Queen Elizabeth Islands, Canadian high arctic. Arctic 56, 381–390 (2003).

Nelson, M. E. & Mech, L. D. Relationship between snow depth and gray wolf predation on white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Manag. 50, 471–474 (1986).

Borg, B. L. & Schirokauer, D. W. The role of weather and long-term prey dynamics as drivers of wolf population dynamics in a multi-prey system. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.791161 (2022).

Bieniek, P. A. et al. Assessment of Alaska rain-on-snow events using dynamical downscaling. J. Appl. Met. Clim. 57, 1847–1863 (2018).

Liston, G. E. & Hiemstra, C. A. The changing cryosphere: Pan-Arctic snow trends (1979-2009). J. Clim. 24, 5691–5712 (2011).

Winski, D. et al. Industrial-age doubling of snow accumulation in the Alaska Range linked to tropical ocean warming. Sci. Rep. 7, 17869 (2017).

Forbes, B. C. et al. Sea ice, rain-on-snow and tundra reindeer nomadism in Arctic Russia. Biol. Lett. 12, 20160466 (2016).

Chapin, F. S. et al. Resilience and vulnerability of northern regions to social and environmental change. Ambio 33, 344–349 (2004).

Schmidt, N. M., Reneerkens, J., Christensen, J. H., Olesen, M. & Roslin, T. An ecosystem-wide reproductive failure with more snow in the Arctic. PLOS Biol. 17, e3000392 (2019).

Solberg, E. J. et al. Effects of density-dependence and climate on the dynamics of a Svalbard reindeer population. Ecography 24, 441–451 (2001).

Dickerson-Lange, S. E. et al. Snow disappearance timing is dominated by forest effects on snow accumulation in warm winter climates of the Pacific Northwest, United States. Hydrological Process. 31, 1846–1862 (2017).

Molotch, N. P. et al. Ecohydrological controls on snowmelt partitioning in mixed-conifer sub-alpine forests. Ecohydrology 2, 129–142 (2009).

Lundquist, J. D., Dickerson-Lange, S. E., Lutz, J. A. & Cristea, N. C. Lower forest density enhances snow retention in regions with warmer winters: A global framework developed from plot-scale observations and modeling. Water Resour. Res. 49, 6356–6370 (2013).

Pinzner, A., Sturm, M., Delamere, J. S. & Mahoney, A. R. An examination of water-related melt processes in arctic snow on tundra and sea-ice. Water Resour. Res. 60, e2022WR033440 (2024).

Sturm, M., Holmgren, J. & Liston, G. E. A seasonal snow cover classification system for local to global applications. J. Clim. 8, 1261–1283 (1995).

Sturm, M. Snow distribution and heat flow in the taiga. Arct. Alp. Res. 24, 145–152 (1992).

Sturm, M. & Benson, C. Scales of spatial heterogeneity for perennial and seasonal snow layers. Ann. Glaciol. 38, 253–260 (2017).

Singh, P., Spitzbart, G., Hübl, H. & Weinmeister, H. W. Hydrological response of snowpack under rain-on-snow events: a field study. J. Hydrol. 202, 1–20 (1997).

Pedersen, S. H. et al. Quantifying effects of snow depth on caribou winter range selection and movement in Arctic Alaska. Mov. Ecol. 9, 48 (2021).

Pedersen, A. O., Beumer, L. T., Aanes, R. & Hansen, B. B. Sea or summit? Wild reindeer spatial responses to changing high-arctic winters. Ecosphere 12 (2021).

Loe, L. E. et al. Behavioral buffering of extreme weather events in a high-Arctic herbivore. Ecosphere 7, e01374 (2016).

Tape, K. D., Gustine, D. D., Ruess, R. W., Adams, L. G. & Clark, J. A. Range expansion of moose in Arctic Alaska linked to warming and increased shrub habitat. PLoS One 11, e0152636 (2016).

Fauchald, P., Park, T., Tømmervik, H., Myneni, R. & Hausner, V. H. Arctic greening from warming promotes declines in caribou populations. Sci. Adv. 3, e1601365 (2017).

Mitchell, C. D., Chaney, R., Aho, K., Kie, J. G. & Bowyer, R. T. Population density of Dall’s sheep in Alaska: effects of predator harvest? Mammal. Res. 60, 21–28 (2015).

Aanes, R. et al. Synchrony in Svalbard reindeer population dynamics. Can. J. Zool. 81, 103–110 (2003).

Murie, A. The wolves of Mount McKinley. Vol. 5 (United States Government Printing Office, 1944).

Mahoney, P. J. et al. Denning phenology and reproductive success of wolves in response to climate signals. Environ. Res. Lett., https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/abc1080ba (2020).

Prugh, L. R. et al. Ecological winners and losers of extreme drought in California. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 819–824 (2018).

Layton-Matthews, K. et al. Extreme events, trophic chain reactions, and shifts in phenotypic selection. Sci. Rep. 13, 15181 (2023).

Plumptre, A. J. et al. Where might we find ecologically intact communities? Front. Forests Global Change 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2021.626635 (2021).

Boelman, N. et al. Integrating snow science and wildlife ecology in Arctic-boreal North America. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 010401 (2018).

Pan, C. G., Kirchner, P. B., Kimball, J. S., Kim, Y. & Du, J. Rain-on-snow events in Alaska, their frequency and distribution from satellite observations. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 075004 (2018).

McCrystall, M. R., Stroeve, J., Serreze, M., Forbes, B. C. & Screen, J. A. New climate models reveal faster and larger increases in Arctic precipitation than previously projected. Nat. Comm. 12, 6765 (2021).

Serreze, M. C. et al. Arctic rain on snow events: bridging observations to understand environmental and livelihood impacts. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 105009 (2021).

Cosgrove, C. L., Wells, J., Nolin, A. W., Putera, J. & Prugh, L. R. Seasonal influence of snow conditions on Dall’s sheep productivity in Wrangell-St Elias National Park and Preserve. PLoS One 16, e0244787 (2021).

Riseth, J. A. et al. Sami traditional ecological knowledge as a guide to science: snow, ice and reindeer pasture facing climate change. Polar Rec. 47, 202–217 (2011).

Laptander, R. et al. Critical seasonal conditions in the reindeer-herding year: A synopsis of factors and events in Fennoscandia and northwestern Russia. Polar Sci. 39, 101016 (2024).

Lundquist, J. D., Kim, R. S., Durand, M. & Prugh, L. R. Seasonal peak snow predictability derived from early-season snow in North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103802 (2023).

NOAA. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) Global Historical Climatology Network Daily (GHCN-D) database. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/land-based-station/global-historical-climatology-network-daily (accessed on 14 March 2023). (2023).

Perica, S. et al. NOAA Atlas 14 Volume 7 Version 2.0, Precipitation frequency atlas of the United States, Alaska. NOAA, National Weather Service, Silver Spring, MD. https://www.weather.gov/media/owp/oh/hdsc/docs/Atlas14_Volume17.pdf (2012).

Mesinger, F. et al. North American Regional Reanalysis. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 87, 343–360 (2006).

Niu, G.-Y. et al. The community Noah land surface model with multiparameterization options (Noah-MP): 1. Model description and evaluation with local-scale measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 116, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD015139 (2011).

GMAO. Global Modeling and Assimilation Office MERRA-2 Meteorology Instantaneous 3-hourly version 5.12.4. Greenbelt, MD, USA: Goddard Space Flight Center Distributed Active Archive Center (GSFC DAAC) https://doi.org/10.5067/VJAFPLI1CSIV (2015).

Peters-Lidard, C. D. et al. High-performance Earth system modeling with NASA/GSFC’s Land Information System. Innov. Syst. Softw. Eng. 3, 157–165 (2007).

Kumar, S. V. et al. Land information system: An interoperable framework for high resolution land surface modeling. Environ. Model. Softw. 21, 1402–1415 (2006).

Jordan, R. A one-dimensional temperature model for a snow cover. Technical documentation for SNTHERM.89, Special Report 91-16, US Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research & Engineering Laboratory (1991).

Jennings, K. S., Winchell, T. S., Livneh, B. & Molotch, N. P. Spatial variation of the rain–snow temperature threshold across the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Comm. 9, 1148 (2018).

Brodzik, M. J., Long, D. G. & Hardman, M. A. Calibrated Enhanced-Resolution Passive Microwave Daily EASE-Grid 2.0 Brightness Temperatures Derived from Level 1C FCDR. Version 1.1. Boulder, Colorado USA: NASA DAAC at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (2021).

Sullender, B. K., Cunningham, C. X., Lundquist, J. D. & Prugh, L. R. Defining the danger zone: critical snow properties for predator–prey interactions. Oikos, e09925 (2023).

Fierz, C. et al. The international classification for seasonal snow on the ground. IHP-VII Technical Documents in Hydrology No. 83, IACS Contribution No. 1, UNESCO-IHP, Paris (2009).

Sullender, B. K., Cunningham, C. X., Lundquist, J. D. & Prugh, L. R. Snow properties and wildlife tracks in Washington and Alaska. ORNL DAAC (2023).

U.S. Geological Survey. 1 Arc-second Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) USGS National Map 3DEP Downloadable Data Collection, U.S. Geological Survey (2017).

Hijmans, R. J. et al. Terra. R package version 1.6-7, https://rspatial.org/terra/ (2022).

Evans, J. S. spatialEco. R package version 1.3-6, https://github.com/jeffreyevans/spatialEco (2021).

Riley, S. J., DeGloria, S. D. & Elliot, R. A terrain ruggedness index that quantifies topographic heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 5, 23–27 (1999).

De Reu, J. et al. Application of the topographic position index to heterogeneous landscapes. Geomorphology 186, 39–49 (2013).

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R. J. 9, 378–400 (2017).

Lüdecke, D. ggeffects: tidy data Frames of marginal effects from regression models. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 772 (2018).

Droghini, A. & Boutin, S. The calm during the storm: Snowfall events decrease the movement rates of grey wolves (Canis lupus). PLoS One 13, e0205742 (2018).

Thurfjell, H., Ciuti, S. & Boyce, M. S. Applications of step-selection functions in ecology and conservation. Mov. Ecol. 2, 4 (2014).

Adams, L. G. & Meier, T. J. Monitoring protocol for the Denali caribou herd, Denali National Park and Preserve, Alaska: Central Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Program. Natural Resource Report NPS/CAKN/NRR—2018/1754. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/607249. (2018).

Meier, T. J. & Burch, J. Wolf monitoring protocol for Denali National Park and Preserve, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve and Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska. Natural Resource Report NPS/CAKN /NRR—2009/168. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available at: https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/447349. (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NASA Interdisciplinary Science grants 80NSSC20K1291 (LRP, JDL) and 80NSSC20K1292 (MTD). Jake Gaposchkin provided invaluable field assistance. MJ Brodzik (NASA NSIDC) assisted with the passive microwave data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LR Prugh: Conceptualization (equal); Funding Acquisition (lead); Investigation (equal); Analysis (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing (lead). JD Lundquist: Conceptualization (equal); Funding Acquisition (supporting); Investigation (supporting); Visualization (equal); Writing (supporting). BK Sullender: Investigation (equal); Analysis (supporting); Visualization (equal); Writing (supporting). CX Cunningham: Analysis (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing (supporting). J Dechow: Analysis (equal); Writing (supporting). BL Borg: Investigation (supporting); Analysis (supporting); Writing (supporting). PJ Sousanes: Analysis (supporting); Writing (supporting). S Stehn: Investigation (supporting); Writing (supporting). MT Durand: Funding Acquisition (supporting); Analysis (equal); Writing (supporting).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Bruce Forbes, Nigel Yoccoz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Eoin O’Gorman, Luke Grinham, and Dario Ummarino. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prugh, L.R., Lundquist, J.D., Sullender, B.K. et al. Landscape heterogeneity buffers the impact of an extreme weather event on wildlife. Commun Biol 7, 1515 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07195-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07195-1