Abstract

Encapsulin nanocompartments loaded with dedicated cargo proteins via unique targeting peptides, play a key role in stress resistance, iron storage and natural product biosynthesis. Mmp1 and cysteine desulfurase (Enc-CD) have been identified as the most abundant representatives of family 2 encapsulin systems. However, the molecular assembly, catalytic mechanism, and physiological functions of the Mmp1 encapsulin system have not been studied in detail. Here we isolate and characterize an Enc-CD-loaded Mmp1 encapsulin system from Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155. The cryo-EM structure of the Mmp1 encapsulin and the crystal structure of the naked cargo Enc-CD have been determined. The structure shows that the Mmp1 protomer assembles two conformation models, the icosahedron (T = 1) and homodecamer, with the resolution of 2.60 Å and 2.69 Å. The Enc-CD at 2.10 Å resolution is dimeric and loaded into the Mmp1 (T = 1) encapsulin through the N-terminal long disordered region. Mmp1 encapsulin protects Enc-CD against oxidation as well as to maintain structural stability. These studies provide new insights into the mechanism by which Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin stores sulfur and provides a framework for discovery of new anti-mycobacterial therapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prokaryotes possess diverse organelles, including membrane-bound, protein-lipid monolayer, protein-bound and phase-derived membraneless organelles1,2,3,4, that compartmentalize cellular processes thereby providing metabolic and physiological advantages5,6,7. One such protein-bound organelle, the encapsulin nanocompartment has attracted increased amounts of attention as potential nanoscale materials in recent years8. The encapsulin system is composed of a single shell protein and various cargo proteins. The single-shell proteins self-assemble into regular icosahedra with diameters ranging from 20 nm (Triangulation, T = 1) to 42 nm (T = 4), possessing a fold similar to bacteriophage Hong Kong 97 (HK97)9,10. Cargo proteins are typically loaded inside encapsulins via unique terminal targeting peptides (TPs), which have been widely studied for their ability to encapsulate other functional proteins as cargos11. The functions of encapsulins are correlated with packaged cargo enzymes. Diverse cargo proteins including ferritin-like proteins12,13,14, DyP-type peroxidases15,16,17, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase18, cysteine desulfurase19,20 and iron-mineralizing encapsulin-associated Firmicutes21, have been found within the encapsulin cavities. Therefore, encapsulins play critical roles in iron storage, oxidative stress, toxic hydroxylamine stress and sulfur metabolism homeostasis. Due to these distinctive structural and functional features, encapsulins, if used innovatively, can provide a platform for biomedical and bioengineering applications22,23. Bioinformatic analysis has revealed more than 900 putative encapsulin systems across fifteen bacterial and two archaeal phyla21. Based on sequence similarity and genome-neighborhood composition, encapsulins are divided into four families (families 1–4)24. Structural and functional studies of family 1 encapsulins have been studied comprehensively12,13,14,15,16, while other family members have been less well-characterized. Family 2 encapsulin capsids were first reported in 199525 and isolated from the membrane fraction of Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium smegmatis, it is therefore termed MmpI (Major membrane protein I). Mmp1 and cysteine desulfurase have been identified as the most abundant representatives of family 2 encapsulin systems26. The Mmp1 homolog SrpI from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 can encapsulate cysteine desulfurase and is upregulated during sulfur starvation, suggesting that the Mmp1 encapsulin is involved in sulfur metabolism19.

Sulfur metabolism is an essential and regulatory cellular metabolic network that produces functional sulfur-containing metabolites for survival and pathogenesis27,28. Cysteine desulfurase, a pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent protein, is highly conserved across kingdoms of life and liberates sulfur (S0) from L-cysteine to a downstream partner sulfur acceptor, which generates L-alanine and modifies the catalytic cysteine residue to a persulfidic adduct (Cys–S–S–H); in addition, it plays a role in the biosynthesis of sulfur-containing cofactors, such as iron-sulfur (Fe–S) clusters, biotin, thiamin, molybdopterin, lipoic acid and the thio-modification of tRNA29,30,31. Fe-S clusters are metal cofactors necessary for essential biological pathways, including photosynthesis, respiration, nitrogen fixation (NIF) and DNA repair32. Three Fe-S clusters biogenesis systems, including NIF, iron-sulfur cluster assembly (ISC) and sulfur formation (SUF) have been found in bacteria (Fig. 1). Although the components of the three systems are distinct, they all use cysteine desulfurase to initiate the reaction. Based on the contributions of cysteine desulfurase to perform housekeeping activity on thio-cofactor biogenesis, stress-defense, and pathogenicity, the enzyme is a good target for drug discovery33,34. Notably, actinobacteria harbor the most encapsulin members (~47%). The gene coding Mmp1 was found directly upstream of cysteine desulfurase in a two-gene operon that is widely distributed among actinobacteria. The encapsulin-associated cysteine desulfurase is refered as the encapsulin-associated SufS/CsdA-like cysteine desulfurase, abbreviated as “Enc-CD”20. In previous studies, Mmp1 was used as a diagnostic biomarker for the detection of M. leprae25,35. However, the molecular assembly, catalytic mechanism and physiological functions of Enc-CD packaged with the Mmp1 encapsulin system have not been studied in detail.

a Enc-CD gene organization in prokaryotes. b Phylogenetic tree of Mmp1 proteins and homologs in mycobacteria. Pathogenic mycobacteria and M. smegmatis mc2155 are highlighted with the black star and grey star, respectively. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA11 and annotated with iTOL81.

M. smegmatis mc2155 is an important model for studying the general biological properties of mycobacteria. In this work, we isolated and resolved the Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin system from M. smegmatis mc2155. In the three-dimensional structure of encapsulin, the Mmp1 protomer can self-assemble into two different symmetries, an icosahedron (T = 1) or as a decamer. The Enc-CD can be loaded into Mmp1 encapsulin by a unique long N-terminal targeting peptide, and the Mmp1 shell protects Enc-CD against oxidation and increases desulfurase activity in the absence of the sulfur acceptor. The Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin supports a unique spatial environment for sulfur storage, preventing sulfide release. Based on biochemical and structural studies, new insights into the mechanism by which Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin sulfur storage occurs in the model organism, M. smegmatis mc2155, are proposed.

Results and discussion

Mmp1 can assemble into a nanocompartment with the cymbals shaped structure

The Enc-CD has been proposed to interact with Mmp1 and form a complex, but to date there is no direct experimental data to validate this hypothesis. To investigate the physiological function and assembly mechanism of the Mmp1 nanocompartment, we first overexpressed the Mmp1-Enc-CD operon (MSMEG_4537-4538) in M. smegmatis mc2155. Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) showed that Mmp1 has two polymerization states, one small and one large. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), mass spectrometry (MS) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) confirmed that Mmp1 can assemble into two polymerization particles, one ~20 nm in diameter and the other ~10 nm in diameter. The two particles correspond to the two polymerization states observed in SEC (Supplementary Figs. 1a and 15a). The major polymerization particles (~20 nm) are identical to the previously described encapsulin nanocompartments (T = 1)24. The UV-visible absorbance spectrum of the major polymerization particles (holo-Mmp1) presented characteristic absorption bands 420 nm consistent with naked Enc-CD, indicating the presence of PLP-bound proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1e). The small particles are Mmp1 homodecamers without Enc-CD loaded (Supplementary Fig. 1f). However, the Mmp1 and Enc-CD co-expressions using the pCDFDuet-1 dual-expression plasmid in Escherichia coli exhibited a single peak corresponding to the holo-Mmp1 encapsulin (Supplementary Figs. 1c and 15c). When Mmp1 was expressed alone in M. smegmatis mc2155 and E. coli, apo-Mmp1 was produced (Supplementary Figs. 1b, 1d, 15b and 15d). In enzymatic digestion experiments, Mmp1 (T = 1) couldn’t be digested and Mmp1 (T = 1) protected Enc-CD from trypsin cleavage while the smaller particles itself could be digested. This result revealed that the assembly of Mmp1 (T = 1) is more stable than the smaller particles (Supplementary Figs. 1g and 15e). The small particles may not be physiologically relevant or they could potentially play an alternative functional role. The expression of the Mmp1 (T = 1) significantly increased in proportion to the coexpression pattern for Enc-CD and Enc-CD mediated the assembly of decameric Mmp1 into the large Mmp1 nanocompartments (Supplementary Figs. 1h and 15f). This demonstrates that direct interaction with Enc-CD triggers Mmp1 to preferentially assemble into the icosahedral capsid (T = 1). This is also in agreement with a different study on Myxococcus xanthus EncA encapsulin (T = 3) and (T = 1), which shows a similar assembly formation36.

The structure of the holo-Mmp1 at 3.08 Å resolution is identical with the apo-Mmp1 except that there are additional cargo densities in the cavity (Fig. 2, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). However, this density is unclear after two-dimensional class averaging and the cargo could not be modeled. This suggests that the linkage between the cargo Enc-CD and the Mmp1 shell is flexible. The cryo-EM data at 2.60 Å resolution, showed apo-Mmp1 has the sixty Mmp1 protomers assembled into a 22-nm-diameter icosahedral capsid (T = 1) (Fig. 2c, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). On the other hand, the Mmp1 decamer (at 2.69 Å resolution) assembles into a structure that has the shape of a cymbals (Fig. 2d, Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 4). The Mmp1 protomer traces the HK97-like fold and includes three domains—the axial domain (A-domain), peripheral domain (P-domain) and extended loop (E-loop), and two unique domains—the N-terminal arm domain (N-arm) with an α-helix and extended C-terminal arm (C-arm). Among the superimposed Mmp1 protomers from the large and small assemblies, the P-domain and A-domain are highly conserved while the partial E-loop and N-terminal α-helix could not be traced in the Mmp1 decamer (Fig. 2e), suggesting the E-loop and N-terminal arm has conformational variation (Supplementary Fig. 5). This indicates that E-loop and N-arm is directly correlated with the assembly state. It is remarkable that the rotation angles of E-loop are varied in three representative structures of different encapsulins. In addition, the N-arm and E-loop protrude outward from the Mmp1 (T = 1) protomer in opposite directions. The detailed analysis of inter-protomer interfaces were performed by PDBePISA37 (Supplementary Table 1). In CFP-29 (T = 1) and EncA (T = 1) encapsulin, the intertwined E-loop (EE’-dimer) forming the large interface area is responsible for twofold interactions. However, E-loops rotation of the Mmp1 and EncA (T = 3) disrupts the usual strong contacts (Fig. 2f). At twofold axis of the Mmp1 (T = 1), the intertwined N-terminal arms (NN’-dimer) combined with the interaction E-loop and N-terminal arm (NE’-dimer) connects neighboring protomers into the chainmail-like topology and stabilizes the Mmp1 (T = 1) assembly. Therefore, the classical family 1 encapsulins (T = 1) usually use EE’-dimer as the basic assembly unit38, while Mmp1 (T = 1) encapsulin may simultaneously use AA’-dimer, NN’-dimer and NE’-dimer as assembly units to form two assembly forms with different sizes.

a The cryo-EM map of holo-Mmp1. The 5, 3, and 2-fold axis are identified by the red pentagon, triangle and oval, respectively. b The cargo densities (gold) within the holo-Mmp1 cavity with the threshold 0.1. c Apo-Mmp1 icosahedral shell (T = 1) formed from 60 protomers (purple). d The cymbals-like structures from the decameric assembly (red). e The superimposed structures of Mmp1 protomers from the large and small assemblies, with the same coloring scheme as in (b, c). f The superimposed structures of the protomers from M. smegmatis MsCFP-29 (T = 1), MsMmp1 (T = 1) and M. xanthus MxEncA (T = 3). M. smegmatis MsCFP-29 (PDB 7BOJ), the MsMmp1 and M. xanthus MxEncA (PDB 4PT2) are shown in pink, purple and orange, respectively. g Arrangement of the neighboring protomers as viewed from the 2-fold axis. The interactions networks involved in the 2-fold symmetric interfaces are highlighted in pink, purple and orange, respectively. The CFP-29 forms E-loop interactions networks whereas the Mmp1 (T = 1) and EncA (T = 3) does not form connections between E-loops. Mmp1 (T = 1) uses a chainmail-like topology.

The protomer of Mmp1 (T = 1) and CFP-29 (T = 1) have 22.12% sequence identity. Structural comparison of the protomer from Mmp1 (T = 1) and CFP-29 (T = 1) shows high similarity with an overall root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d) of 1.384 Å over 226 Cα atoms. However, the conformation of the A-domain is obviously different. The A-domain of the Mmp1 (T = 1) protomer contains variable loop regions, Loop1 (T155-T161), Loop2 (V172-A177), Loop3 (R196-P201), Loop4 (T212-P217) and Loop5 (S221-K232), respectively. Structural comparison revealed that Spine helix rotation triggers the overall A-domain motion adjacent to E-loop, causing the vertices of Mmp1 capsids to protrude from fivefold vertices, resulting in the formation of a disordered “spike”. Especially, the protrusion of the extended Loop5 and C-terminal arm contributes to the formation of the “spike” (Fig. 3). It is worth noting that the secondary structure element between Loop3 and Loop4 switches from α-helix in CFP-29 to β-sheet folds in Mmp1. These conformation differences suggest that the fivefold axis of Mmp1 encapsulin adopts a unique conformation differently from family 1 encapsulins. It has previously been suggested that this disordered “spike” endows the protein with a higher level of immunogenicity39,40. These structural studies provide the opportunity to further evaluate Mmp1 encapsulins as potential biomarkers of mycobacterial disease. Furthermore, the pore of the fivefold axis is narrow (7.4 Å), selectively restricting small molecules to pass through. In contrast to S. elongatus SrpI encapsulin which contains a positively charged pore in the fivefold axis, the fivefold axis pore of M. smegmatis Mmp1 contains Tyr195, Glu305 and Gln307 and thus is polar with a slight negative charge (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). At the intracellular pH of 6.1~7.2 in M. smegmatis, the free cysteine substrates for the Enc-CD with intrinsic thiolate (pKa 8.6) will be predominantly protonated41,42, and therefore be able to cross the fivefold axis pore.

a The comparison of A-domain structures from the Mmp1 and CFP-29. b The protomer arrangement around the 5-fold symmetry axis in Mmp1 and MsCFP-29. The 5-fold vertice protrudes from the structure in a disordered “spike” whereas the 5-fold vertex in the classical family 1 encapsulin CFP-29 is relatively flat. Cartoon presentations of the 5-fold vertex from the Mmp1 and CFP-29 encapsulins, in top and side views, respectively. c Cartoon and electrostatic potential surface representations of the 5, 3, 2-fold pores in the Mmp1 (T = 1).

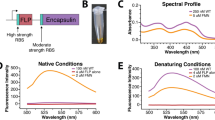

The cargo Enc-CD is more resistant to oxidation

There are three cysteine desulfurase homologs (IscS, SufS and CsdA) in the gram-negative bacterium E. coli and two homologs (YrvO and SufS) in the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis43. According to a sequence alignment, the cargo Enc-CD is a type II cysteine desulfurase (Supplementary Fig. 8). However, no structural information for the Enc-CD is currently available. AlphaFold44 and DISOPRED345 predicted that the Enc-CD can be divided into separate N and C-terminal domains. An intrinsically disordered region (IDR) is in the N-terminal domain (NTD, M1-I155) while the C-terminal domain (CTD F156-V559) is well-folded cysteine desulfurase domain (Fig. 4a). Owing to the IDR having flexible structures46,47, we did not obtain crystals for full-length construct. Instead, we digested the Enc-CD with trypsin in anticipation to cleave the IDR, resulting in successful crystallization (Supplementary Figs. 9b and 16b). The structure of ∆NTD-Enc-CD was subsequently determined at 2.10 Å resolution (Table 2). The ∆NTD-Enc-CD shows the canonical homodimeric structure (~54 × 85 Å) (Fig. 4b). Each of the two subunits has a larger N-domain (F156-V449) where the covalently attached PLP cofactor is located and a smaller C-domain (G450-V559). The N-domain consists of a central 7-strand parallel β-sheet (β1-β7), sandwiched by several short α-helices (α6-α11). The two subunits latch on to each other using an α-hinge (N204-L214) and a β-hook structure (I409-F426) (Supplementary Fig. 9a). In contrast, the C-domain being more compact has only four β-strands and four α-helices. The conserved catalytic residues His276, Lys379 and Cys517 are buried in the active site cavity located in the center of the protein (Fig. 4c). His276 interacts PLP through the polar-π interactions that are favorable for acquiring sulfur from the substrate. Lys379 covalently binds to the PLP cofactor via an internal Schiff base. Cys517 located in the Cys catalytic loop is the Cys that is converted to the persulfide intermediate (Cys–S–S–H). The structure of the Enc-CD is very similar to EcSufS, MtbSufS and BsSufS, with root-mean-square deviations (r.m.s.d) of 0.936, 0.839 and 0.781 Å for all Cα atoms, respectively. We analyzed cysteine desulfurase activity via the methylene blue assay by quantifying the amount of sulfide (S2−) produced. Enc-CD and ∆NTD-Enc-CD have similar basal levels of desulfurization with kcat values of 3.15 ± 0.40 min–1 and 2.98 ± 0.01 min–1, respectively, showing that the N-terminal disordered regions of the Enc-CD have no detectable influence on catalytic activity (Supplementary Fig. 9d). Compared to other desulfurases, Enc-CD shows a greater basal desulfurase activity. The superimposition of the four structures shows that they have a major difference, being that the α-hinge is in different conformations in all four structures (Supplementary Fig. 10). As previously reported, the α-hinge and C-terminus of Enc-CD are responsible for binding the acceptor48. Previous experiments showed that EcSufS H55A mutant, which is homologous to His208 in the α-hinge region of the Enc-CD, increased PLP occupancy and transpersulfuration activity49. Therefore, the outward protrusion of the α-hinge region may be favorable for substrate entry or persulfide delivery to the acceptor. Furthermore, extra continuous electron density adjacent to the sulfur atom of the Cys517 residue in the 2Fo-Fc density map, suggests that the Enc-CD was covalently modified (Fig. 4d). Mass spectrometry of the modified peptides revealed Cys517 with additional masses of +31.97, +79.96, +111.93 and +143.90 Da (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that various sulfur species of Cys517 were present, which include sulfur (–SH), sulfite (–SO3H), thiosulfate (–S2O3H) and thioperoxomonosulfate (–S3O3H) in occupancies similar to that observed in CsdA crystals (PDB:5FT6)50. In addition, MS analysis revealed that compared to encapsulated Enc-CD, naked Enc-CD is more susceptible to thiosulfate oxidation modifications (Cys–S–SO3–). Moreover, in the coupled-enzyme assay the encapsulated Enc-CD showed greater desulfurization capacity than that of naked Enc-CD, with kcat values of 1.34 ± 0.15 min−1 and 0.20 ± 0.03 min−1 respectively, suggesting that Mmp1 shells can enhance desulfurase activity in the absence of a sulfur acceptor (Supplementary Fig. 9e). This result demonstrates that the Cys517 is oxidized by oxygen or reactive oxygen species during purification, potentially forming dead-end sulfonic acid species that further block sulfur release49,51,52. All the data indicate that Mmp1 provides a special local environment to protect Cys517 from oxidation.

a Analysis of the sequences of the Enc-CD using DISOPRED3. The N-terminal domains of the Enc-CD show a strong disorder potential (average disorder scores>0.5). b Cartoon representation of the Enc-CD (top and side view). N terminus, C terminus, Cys catalytic loop (H515-A518, orange), β-hook (yellow) and α-hinge (red) are highlighted. c Surface representation of the active site of Enc-CD with key residues (H276, K379, C517 and R532) and PLP cofactor in the active site pocket represented as sticks models. d 2Fo-Fc density map for Cys517.

The N-terminal disordered regions direct in vivo loading of the cargo protein

Based on motif-based sequence analysis (MEME)53, the IDR of the Enc-CD contain multiple short conserved motifs (Fig. 5a). To determine the role of the IDR and motifs in encapsulation, we expressed Mmp1-1-21-CTD, Mmp1-35-55-CTD, Mmp1-107-121-CTD and Mmp1-∆1-155-CTD operon in M. smegmatis mc2155. The results showed that Enc-CD without the N-terminal disordered regions cannot be encapsulated (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Figs. 11a and 16c). Interesting, individual motif was not sufficient to sequester cargo within the compartment, consistent with the SrpI19, suggesting multiple motifs are required for the packaging of cargo protein. According to the distribution of these motifs, the disordered region was split into LR (leading region, M1-R50) and MR (middle region, G51-I155). The two regions can be used for Enc-CD packaging, respectively. In a subsequent experiment, we fused the IDR and the two regions to the N-terminus of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and co-expressed it with Mmp1 in E. coli, respectively. In addition, we also co-expressed Mmp1 and GFP as a negative control. We showed that GFP with the IDR, LR or MR could pack into Mmp1 nanocompartment, but naked GFP could not (Supplementary Figs. 11b and 16d). Consequently, these regions play essential roles in native and heterologous cargo loading. Unlike the short TPs at the C-terminus12, Enc-CD uses the long TP at the N-terminus of the cargo protein. The LR is rich in hydrophobic amino acids (e.g., alanine, leucine and proline) that are frequently present in TPs of family 1 encapsulins, as well polar amino acids (serine, aspartate, glutamate and arginine), suggesting that both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions participate in TP targeting. Fluorescence confocal microscopy shows that encapsulated GFP typically aggregates around both ends of M. smegmatis mc2155 along the longitudinal axis while free GFP is distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 11c and 16e), suggesting that the Mmp1 shell is essential for the subcellular spatial localization of this encapsulin system.

a Predicted structural organization of the Enc-CD. The leading region (LR), middle region (MR) and C-terminal cysteine desulfurase domain (CTD) are indicated by the pink, grey and light green box, respectively. b SEC and SDS-PAGE analysis of the operon Mmp1-∆1-155-CTD, Mmp1-1-50-CTD, Mmp1-51-155-CTD and Mmp1-Enc-CD expression in M. smegmatis mc2155. c The subcellular distribution of encapsulated GFP and naked GFP in M. smegmatis mc2155 (scale bar = 2.5 μm).

The proposed model for sulfur storage and deployment

For the type II cysteine desulfurase, a specific acceptor (such as CsdE and SufU/E) accepts sulfur and modulates cysteine desulfurase activity in vivo. However, the sulfur receptor of the Enc-CD protein has not been identified. Here, we used a methylene blue assay to analyze desulfurase activity to produce sulfide and a coupled-enzyme assay for the production of L-alanine. In both assays, Mmp1 shells alone exhibited no catalytic activity, further confirming that the physiological function of Mmp1 encapsulin is closely related to the Enc-CD. Adding dithiothreitol (DTT), as a reductant, can regenerate the desulfurase persulfide site, allowing the reaction to proceed to subsequent cycles54. Under nonreducing conditions, the desulfurase homologs undergoes multiple turnovers, producing the reactive polysulfide (Cys-S-Sn–) on the conserved Cys residues and then spontaneously releasing elemental sulfur54,55,56. There was no obvious electron-dense core within the purified holo-Mmp1 from M. smegmatis mc2155 after induction for 3 days. However, with prolongation of the culture period for up to 10 days the electron-dense cores of the holo-Mmp1 were more predominant (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Transmission electron microscopy energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM-EDS) showed the electron-dense cores are rich in sulfur, suggesting that Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin facilitates bacterial sulfur storage in formation of sulfur puncta. In sulfur accumulation assay in vitro, we incubated the purified holo-Mmp1 with different concentrations of the substrate cysteine for 3 days, and then observed the samples by cryo-EM (Supplementary Fig. 12b). The result showed that the number of the sulfur puncta increased with the cysteine concentration. In addition, due to the mutation (C517A) in the active site of the Enc-CD, no obvious sulfur puncta were observed at even high substrate concentration, suggesting that the sulfur accumulation is Enc-CD-dependent biological process. Two-dimensional classification of the holo-Mmp1 with sulfur puncta showed that the obvious electron densities in the cavity of the Mmp1 (Supplementary Fig. 12c). High-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) imaging revealed that the sulfur puncta with different dimensions were highly crystalline based on clear lattice fringes. X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) showed that in holo-Mmp1 the sulfur has intermediate chemical valences –1 and 0 (S2p3/2 binding energy: 163.8 eV and 165.0 eV), while in apo-Mmp1 the sulfur is present in the reduced state with a valency of –2 (S2p3/2 binding energy: 163.4 eV and 164.2 eV) mainly from cysteine and methionine residues (Supplementary Fig. 13). All data show that sulfur puncta contain elemental sulfur (S0) and polysulfides (Sn2–).

Sulfur, which has a wide range of redox states (–2 to +6) is an essential chemical element for microbial growth. Microbial sulfur utilization is usually mediated through redox reactions, usually coupled with biochemical cycling of other elements, such as carbon, hydrogen and various metals57,58. The storage and remobilization of the sulfur stored inside encapsulins among mycobacteria is poorly understood. Notably, in vitro holo-Mmp1 has significant background sulfide levels in the presence of DTT, suggesting that elemental sulfur (S0) and polysulfides (Sn2–) is vulnerable to reduction to sulfide (S2-) (Supplementary Fig. 14). H2S is reportedly the most common reduced product of the diverse physiologically relevant polymeric sulfurs59. H2S serves as a double-edged sword. In the cytoplasmic environment, H2S is an endogenous antioxidant against oxidative stress60, and is inherently toxic and reactive to the cell at high concentrations (20–160 μΜ)55. Any sulfide released in an uncontrolled manner could react with the labile iron pool to form iron sulfides, which are more efficient than ferrous iron in catalyzing the Fenton reaction to form highly damaging hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide61. However, due to the small size of the pores, the primary reducing agent ergothioneine (EGT) and glutathione (GSH) in the cytoplasm cannot access to reduce sulfur puncta. Therefore, Enc-CD-loaded encapsulins store hydrophobic elemental sulfur (S0) and reactive intermediates (Sn2–) within a special relatively independent cavity, preventing sulfur reduction and limiting H2S to reach toxic levels (Fig. 6). Furthermore, numerous studies have shown that polysulfide is the direct sulfur source for rhodanese catalysis in biosynthesis of the EGT62 and serves as an electron acceptor for polysulfide:quinone oxidoreductase coupling to energy conservation for many microorganisms growth63,64. This situation is related to that of encapsulated ferritin which has an ability to store more Fe than naked ferritin65,66. Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin enhances desulfurization activity and accumulates sulfur within the lumen.

In addition to cysteine desulfurase from the SUF and ISC system in M. smegmatis mc2155, Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin is another cysteine desulfurase for sulfur mobilization. The Mmp1 encapsulin provides a special environment for this to occur. The substrate cysteine enter the lumen of the Mmp1 through the pore of the five-fold axis. The cargo Enc-CD catalyzes the formation of poorly soluble polysulfides bound to hydrophobic sites in the protein and are stored as stable sulfur puncta. In the presence of the reductant, the Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin can release sulfur from sulfur puncta (yellow circles) for sulfur metabolism.

In conclusion, we have investigated the structure and function of native mycobacterial Enc-CD-loaded Mmp1 encapsulin system, a family 2 encapsulin system distinct from previously reported encapsulin systems. We have shown that the Mmp1 protomer can assemble into two different polymeric arrangements, one as icosahedral capsid (T = 1) and the other as decameric. The Enc-CD assembles into a homodimer and gains access the interior of encapsulin (T = 1) via the N-terminal disordered region. The direct interaction between the Enc-CD and Mmp1 modulates the assembly state of Mmp1 encapsulin. The fivefold pores of Mmp1 are narrow and weakly negatively charged, restricting the passage of substrates and products. Mmp1 (T = 1) can protect the Enc-CD from oxidation and enhance desulfurase activity. This encapsulin can protect the cell from excessive free sulfide by storing sulfur within the central cavity. As a representative of mycobacteria, M. smegmatis mc2155 contains three conserved ISC, SUF and Enc-CD-loaded encapsulin systems. As a result, the encapsulin system provides new insights into sulfur metabolism in an organism that exploits redundancy to metabolic adaptation. These structures or modified versions have potential application for use as protein-based nanoparticles in the fields of drug delivery, vaccine development and nano reaction chambers.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

The coding sequence of The Mmp1 (MSMEG_4357), Enc-CD (MSMEG_4358) and the Mmp1-Enc-CD operon (MSMEG_4357-4358) was from Mycobrowser (https://mycobrowser.epfl.ch). The genes were amplified from the genomic DNA of M. smegmatis mc2155 (ATCC 700084) and inserted in the frame between ATG start codon and SalI site of the shuttle vector pMV-261 with C-terminal Flag tag fusions to Enc-CD (pMV-261-Enc-CD) or N-terminal Flag tag fusions to Mmp1 (pMV-261-Mmp1-Enc-CD, pMV-261-Mmp1, pMV-261-Mmp1-1-21-CTD, pMV-261-Mmp1-35-55-CTD, pMV-261-Mmp1-107-121-CTD, pMV-261-Mmp1-1-50-CTD, pMV-261-Mmp1-51-155-CTD, and pMV-261-Mmp1-∆1-155-CTD). The plasmids were expressed and proteins purified based on the following protocols. First, the plasmids were electrotransformed into M. smegmatis mc2155 for expression. Cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani culture supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 40 μg/mL carbenicillin and 0.1% Tween 80 until OD600 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.2% w/v acetamide and 0.2 mM PLP for 3~10 days at 16 °C. Cells were harvested and lysed in a binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl). The cell lysate was subsequently centrifuged at 39,200 × g at 4 °C for 40 min. The supernatant was collected and loaded onto an Anti-DYKDDDDK G1 Affinity Resin column (GenScript). After washing the proteins were eluted with elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 200 μg/mL DYKDDDDK) and then concentrated. The proteins were loaded onto a Superose 6 Increase 10/300GL column (Cytiva) and eluted with the binding buffer. Fractions were concentrated for SDS-PAGE, crystallography and Cryo-EM analysis. The genes of the Enc-CD (MSMEG_4358) or GFP (GenBank: QJR97841.1) and Mmp1 (MSMEG_4357) were inserted into the MCS1 NcoI site and MCS2 NdeI site of pCDFDuet-1 (Novagen), respectively, with C-terminal Flag tag fusions to Mmp1 (pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-Enc-CD, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-1-155-GFP, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-1-21-GFP, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-35-55-GFP, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-107-121-GFP, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-1-50-GFP, pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-51-155-GFP or pCDFDuet-1-Mmp1-GFP). All the plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Vazyme C504-02) respectively for protein expression. Cells were grown at 37 °C in LB culture supplemented with 40 μg/mL streptomycin until the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. Expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and 0.2 mM PLP for 18~20 h at 16 °C. Proteins from E. coli. were purified using the same method above.

UV-vis absorbance spectroscopy

The PLP occupancy of Enc-CD was determined using a previously reported method67. The Enc-CD was diluted to 30–60 μM in 160 μL samples containing binding buffer. 40 μL of 5 M NaOH was added into the protein samples and these were incubated at 75 °C for 10 min. Then 17 μL of 12 M HCl was added to the protein samples which were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was measured at 390 nm on a GeneQuant 1300 spectrophotometer. The PLP concentration was calculated using the standard curve of free PLP (Sigma-Aldrich P9255) absorbance at 390 nm under identical conditions. By comparing molar ratios of monomeric Enc-CD and PLP, the PLP occupancy could be calculated.

Trypsin digestion

The holo-Mmp1, apo-Mmp1 and decamer Mmp1 prepared from M. smegmatis mc2155 were digested with a trypsin/protein ratio of 1/50 (w/w) overnight at 16 °C. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed before and after digestion.

Re-assembly of the Mmp1 and Enc-CD

The proteins were prepared from M. smegmatis mc2155 expression system using the pMV-261-Enc-CD and pMV-261-Mmp1. The concentration of the Mmp1 decamer and Enc-CD are 9.5 mg/mL and 7 mg/mL in the final volume incubated overnight at 4 °C. Then the samples were analyzed by SEC and SDS-PAGE.

Methylene blue assay

Sulfide release was determined by the methylene blue assay51,68. Enzymatic reactions were performed in assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT) with 3 μM holo-Mmp1, apo-Mmp1, Enc-CD, ∆NTD-Enc-CD and varying L-cysteine (BBI A600132-0500) concentrations. After incubation at 25 °C for 5 min, the reaction was quenched by the addition of N, N-Dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DMPD, Sigma-Aldrich 193992-5G) in 7.2 M HCl and FeCl3 in 1.2 M HCl. The quenched mixture was incubated for 30 min in the dark to allow methylene blue formation. After centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 5 min, the methylene blue concentration was measured at 670 nm using a Thermo Varioskan Flash. Experiments were pursued with at least triplicate biological replicates (n = 3) and were reproducible. Kinetic parameters were fitted using Michaelis–Menten equation in Graphpad Prism 8.0.2.

Coupled enzyme assay

Cysteine desulfurase activity was carried out in an enzyme-coupled assay with alanine dehydrogenase. Enzyme reactions were performed at 25 °C in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM NAD+, 1 μ/mL alanine dehydrogenase (Sigma-Aldrich 73063), 400 nM Enc-CD, ∆NTD-Enc-CD and encapsulated Enc-CD and varying L-cysteine concentrations. NADH production was monitored at 340 nm (excitation)/460 nm (emission) using BMG CLARIOstar Plus. Activity data is reported as a function of initial rate of alanine formation and cysteines concentration. Experiments were pursued with at least triplicate biological replicates (n = 4). Kinetic parameters were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2.

Sulfur accumulation in vitro

The holo-Mmp1 and encapsulated Enc-CD (C517A) purified from M. smegmatis mc2155 harboring pMV-261-Mmp1-Enc-CD or pMV-261-Mmp1-Enc-CD (C517A) after induction 3 days. We performed sulfur accumulation assay in vitro in assay buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl). 5 mg/mL Holo-Mmp1 and encapsulated Enc-CD (C517A) reacted with varying concentrations of L-cysteine at 16°C for 3 days. The protein samples (0.5 mg/mL) for cryo-EM were prepared in the same way as the following cryo-EM data collection.

Cryo-EM data collection

For Mmp1 and Mmp1 decamer, 3 μL protein sample (0.5 mg/mL) was applied to QuantifoilTM R1.2/1.3 300 gold mesh grid after a 30 s H2/O2 glow discharge. The grids were blotted with a blot force of 0 for 3 s at 4 °C and 100% humidity, and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using Thermo Scientific Vitrobot Mark IV. The cryo-EM data were collected using a Thermo Scientific 300 kV Titan Krios microscope, equipped with a K3 direct electron detector. For Mmp1, the movie stacks were recorded at 29k× magnification with calibrated pixel size of 0.82 Å/pixel. The exposure time was set to 2.4 s, and the total cumulative dose was 60e−/ Å2. SerialEM 4.1.0 was used to automatically record all images and the defocus range was set from –1.8 to –1.2 μm. In total, 2614 movies were captured for this dataset. For Mmp1 decamer, the movie stacks were recorded at 105k× magnification with calibrated pixel size of 0.832 Å/pixel. The exposure time was set to 2 s, and the total cumulative dose was 60 e−/ Å2. SerialEM 4.1.0 was used to automatically record all images and the defocus range was set from –1.8 to –1.2 μm. In total, 3032 movies were captured for this dataset.

Cryo-EM data processing

For Mmp1 (T = 1), all movie stacks were motion-corrected using Relion3.0.3 with a 5 × 4 patch and twofold binning69. The contrast transfer functions (CTF) were estimated by cryoSPARC Patch CTF Estimation70. All particles were blob-picked with a range of 250–350 Å and extracted with a box size of 512 pixels. After 2D classification, classes were selected as the references for template picking. For Mmp1, a total of 114,361 particles were extracted to conduct the following 2D classification. Classes with obvious characteristics and clear morphology were selected (83,659 particles in total) for the initial 3D reconstructing into four classes. The four classes were used as a template for the heterogeneous refinement. The class with distinct shape and dimer characteristics contained 83,655 particles. All 3D classifications and refinements were accomplished in cryoSPARC71. With Non-uniform refinements72, the final resolution was 2.60 Å. According to the golden-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) with threshold of 0.143, the local resolution ranges were analyzed by cryoSPARC v4.0.1. For Mmp1 decamer, image processing was performed with a similar pipeline with the box size of 360 pixels, allowing final resolution of 2.69 Å to be obtained.

Cryo-EM model building and refinement

The atomic models were built in Coot73 with the Mmp1 homolog (PDB 6X8M) from Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 as a model. Real-space refinements and validation were all perfomed in Phenix74.

Crystallization and data collection

Duet to the flexibility of the polypeptide, we did not obtain crystals of Enc-CD. Therefore, we used trypsin to cleave the disordered region, allowing crystals growth. The Enc-CD was digested with trypsin (1:200) at 4 °C for 2 h, then repurified using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300GL column (Cytiva) and concentrated to 6 mg/mL with a 50 kDa MWCO ultrafiltration device. Subsequently, the narrower absorbance peak of SEC is indicative of improved homogeneity. Then analytical ultracentrifugation and peptide fingerprinting show Enc-CD as a homodimer state in solution without the N-terminal disordered regions. Crystallization trials were set up in 48-well sitting drop plates by dispensing 1 μL of reservoir solution and 1 μL of the protein solution. Crystals grew at 16 °C by vapor diffusion in the reservoir solution 0.1 mM Bis-Tris pH 6.5 and 9–24% w/v PEG10000. Yellow hexagonal crystals grew to full size in 5–7 days. Crystals were cryo-protected with a mixture solution in a 1:1 ratio ethylene glycol:glycerol at 20% of the drop volume. All the datasets were collected on beamline BL18U1 at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) and were processed with HKL200075.

Structure determination and refinement

The structure of ∆NTD-Enc-CD was determined by molecular replacement using PHASER in CCP4 7.0 with the coordinates of Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia 1 cysteine desulfurase (PDB 6C9E) as the initial model. Model building and refinement was performed within Coot 0.8.9.2 and Phenix 1.14, respectively. The final refined models were validated by MolProbity76. All the structural models were visualized in Chimera77, ChimeraX78 and Pymol79.

LC-MS/MS analysis

Sample preparation. A fivefold volume of pre-cold acetone was added to each sample solution to precipitate the proteins at −20 °C for 12 h. After centrifugation the supernatant was removed and the precipitate was washed three times with pre-cold acetone. 0.1 mL of lysis buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 8 M urea) was added to dissolve the precipitate. The proteins were trypsin digested at 37 °C for 16 h. After tryptic digestion, the peptides were desalted and quantified. For each sample, 200 ng of peptides were analyzed by Orbitrap eclipse Tribrid mass spectrometer with a nano-spray ion source, connected to an easyLC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For each injection, peptides were loaded to a homemade C18 column and separated with a 60 min gradient. Phase A consisted in 0.1% formic acid in water while phase B was 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile. The LC flow rate was 300 nL/min and the column temperature was 60 °C. DDA mode was selected for MS data acquisition. The parameters were set as follow: scan range (m/z) = 350–2000, MS1 resolution = 60,000, charge range = 2–7, MS2 resolution = 30,000, collision energy = 30%.

LC-MS/MS data analysis

The raw data of MS were analyzed using PEAKS Studio (version 11, Bioinformatics Solutions Inc., Waterloo, Canada). The parameters were set as follow: Precursor Mass Error Tolerance at 10.00ppm, Fragment Mass Error Tolerance at 0.02 Da, enzyme as trypsin, Max Missed Cleavage at 2, Digest Mode as Specific, Peptide Length Range at 4–45, Max Variable PTM per Peptide at 6, Variable Modifications as methionine oxidation (+15.99), Enc-CD-S (+31.97), Enc-CD-SO3 (+79.96), Enc-CD-S2O3 (+111.93) and Enc-CD-S3O3 (+143.90).

Motifs analysis

The motifs analysis of the disordered region of Enc-CD was performed in Motif Discovery-MEME by MEME server53 (https://meme-suite.org/), based on 94 available encapsulin-associated desulfurase sequences from mycobacteria. Three short conserved motifs (residues M1-E21, R35-G55 and V107-G121) were found at various positions across the disordered regions. Meantime, disorders motifs analysis was performed in Motif Discovery-STREME, based the same sequences. Eight shorter motifs (residues M1-S8, L9-I17, S18-A32, P36-Q43, V47-G55, S75-A88, D101-G109 and V112-G121) were found.

Confocal microscopy

The plasmids pMV-261-Mmp1-GFP and pMV-261-Mmp1-1-155-GFP were electrotransformed into M. smegmatis mc2155. Protein expression was induced by 0.2 mM PLP and 0.2% w/v acetamide for three days at 16 °C. Bacterial cell membranes were stained with 5 μM FM4-64 fluorescent dye (MedChemExpress HY-103466) for 15 min at 4 °C. Then fluorescence strains were examined using a super-resolution imaging system structured illumination microscopy with a 63× oil-immersion objective and excitation at 488 and 561 nm, respectively.

TEM-EDS analysis

Holo-Mmp1 solution was applied to carbon film of 200-mesh Cu grid for completely dry. STEM was carried out using an aberration Corrected Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL Ltd) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (TEM-EDS) detection system and operated at 200 kV. High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images were collected in a range of 56 to 200 mrad, with a beam convergence angle of 10.5 mrad.

XPS analysis

XPS spectra were carried out using Axis Ultra DLD instrument (Kratos Analytical Ltd). Holo and apo-Mmp1 sample in ddH2O after freeze-drying were pressed, pasted on the sample tray, and put into the chamber. The sample surface was excited with monochromatic Al kα radiation (1486.7 eV). The source voltage and emission current were 15 keV and 10 mA, respectively. The charge correction and peak fitting were performed in CasaXPS. The sulfur chemical state was determined using the binding energy and intensity of the photoelectron peaks (count per second, CPS).

Statistics and reproducibility

The cysteine desulfurase activity was performed in the methylene blue assay and coupled enzyme assay. Experiments data were pursued with at least triplicate biological replicates (n ≥ 3) and were reproducible. Kinetic parameters were fitted to the Michaelis–Menten equation using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. LS-MS/MS experiments for the oxidative modification analysis on Cys residues were repeated three times. Data represent mean values and standard deviation calculated by Graphpad Prism 8.0.2. Source data are are available on Zenodo80.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Biological constructs for this paper are available in Supplementary Data 1. The source data for the graphs presented in the figures of this paper are available in Supplementary Data 2. Results of the oxidative modification analysis for Supplementary Table 2 are available in Supplementary Data 3. Peptide Mass Fingerprinting for Mmp1 and Enc-CD are available in Supplementary Data 4. The cryo-EM density maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession code EMD-60569 (holo-Mmp1), EMD-37691 (apo-Mmp1) and EMD-37693 (Mmp1 decamer). The coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession code 8WOL (apo-Mmp1), 8WON (Mmp1 decamer) and 8KG1 (Enc-CD). These PDB files can be found in Supplementary Data 5, 6 and 7. Source data for uncropped SDS-PAGE images, LC-MS/MS, density map and PDB files are deposited to repository Zenodo80 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14015422).

References

Jin, X. et al. Membraneless organelles formed by liquid-liquid phase separation increase bacterial fitness. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2929 (2020).

Janissen, R. et al. Global DNA compaction in stationary-phase bacteria does not affect transcription. Cell 174, 1188–1199 (2018).

Hondele, M. et al. DEAD-box ATPases are global regulators of phase-separated organelles. Nature 573, 144–148 (2019).

Racki, L. R. et al. Polyphosphate granule biogenesis is temporally and functionally tied to cell cycle exit during starvation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E2440–E2449 (2017).

Cornejo, E., Abreu, N. & Komeili, A. Compartmentalization and organelle formation in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 26, 132–138 (2014).

Greening, C. & Lithgow, T. Formation and function of bacterial organelles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 677–689 (2020).

Volland, J. M. et al. A centimeter-long bacterium with DNA contained in metabolically active, membrane-bound organelles. Science 376, 1453–1458 (2022).

Nichols, R. J., Cassidy-Amstutz, C., Chaijarasphong, T. & Savage, D. F. Encapsulins: molecular biology of the shell. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 52, 583–594 (2017).

Duda, R. L. & Teschke, C. M. The amazing HK97 fold: versatile results of modest differences. Curr. Opin. Virol. 36, 9–16 (2019).

Hua, J. F. et al. Capsids and genomes of jumbo-sized bacteriophages reveal the evolutionary reach of the HK97 fold. mBio 8, e01579-17 (2017).

Cassidy-Amstutz, C. et al. Identification of a minimal peptide tag for in vivo and in vitro loading of encapsulin. Biochemistry 55, 3461–3468 (2016).

Sutter, M. et al. Structural basis of enzyme encapsulation into a bacterial nanocompartment. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 939–947 (2008).

McHugh, C. et al. A virus capsid-like nanocompartment that stores iron and protects bacteria from oxidative stress. EMBO J. 33, 1896–1911 (2014).

Giessen, T. W. et al. Large protein organelles form a new iron sequestration system with high storage capacity. eLife 8, e46070 (2019).

Lien, K. et al. A nanocompartment system contributes to defense against oxidative stress in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eLife 10, e74358 (2021).

Tang, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structure of Mycobacterium smegmatis DyP-loaded encapsulin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025658118 (2021).

Jones, J. A., Andreas, M. P. & Giessen, T. W. Structural basis for peroxidase encapsulation inside the encapsulin from the Gram-negative pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nat. Commun. 15, 2558 (2024).

Xing, C. et al. A self-assembled nanocompartment in anammox bacteria for resisting intracelluar hydroxylamine stress. Sci. Total Environ. 717, 137030 (2020).

Nichols, R. et al. Discovery and characterization of a novel family of prokaryotic nanocompartments involved in sulfur metabolism. eLife 10, e59288 (2021).

Benisch, R., Andreas, M. P. & Giessen, T. W. A widespread bacterial protein compartment sequesters and stores elemental sulfur. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk9345 (2024).

Giessen, T. & Silver, P. Widespread distribution of encapsulin nanocompartments reveals functional diversity. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17029 (2017).

Rodríguez, J., Allende-Ballestero, C., Cornelissen, J. & Castón, J. Nanotechnological applications based on Bacterial Encapsulins. Nanomaterials 11, 1407 (2021).

Kennedy, N. W., Mills, C. E., Nichols, T. M., Abrahamson, C. H. & Tullman-Ercek, D. Bacterial microcompartments: tiny organelles with big potential. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 63, 36–42 (2021).

Giessen, T. Encapsulins. Annu Rev. Biochem. 91, 353–380 (2022).

Winter, N. et al. Characterization of the gene encoding the immunodominant 35 kDa protein of Mycobacterium leprae. Mol. Microbiol. 16, 865–876 (1995).

Andreas, M. P. & Giessen, T. W. Large-scale computational discovery and analysis of virus-derived microbial nanocompartments. Nat. Commun. 12, 4748 (2021).

Hatzios, S. K. & Bertozzi, C. R. The regulation of sulfur metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002036 (2011).

Bhave, D., Muse, W. & Carroll, K. Drug targets in mycobacterial sulfur metabolism. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 7, 140–158 (2007).

Singh, H., Dai, Y. Y., Outten, F. W. & Busenlehner, L. S. Escherichia coli SufE sulfur transfer protein modulates the SufS cysteine desulfurase through allosteric conformational dynamics. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 36189–36200 (2013).

Lill, R. Function and biogenesis of iron-sulphur proteins. Nature 460, 831–838 (2009).

Roche, B. et al. Iron/sulfur proteins biogenesis in prokaryotes: formation, regulation and diversity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 455–469 (2013).

Blahut, M., Sanchez, E., Fisher, C. E. & Outten, F. W. Fe-S cluster biogenesis by the bacterial Suf pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1867, 118829 (2020).

Das, M., Dewan, A., Shee, S. & Singh, A. The multifaceted bacterial cysteine desulfurases: from metabolism to pathogenesis. Antioxidants 10, 997 (2021).

Elchennawi, I., Carpentier, P., Caux, C., Ponge, M. & Ollagnier de Choudens, S. Structural and biochemical characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Zinc SufU-SufS complex. Biomolecules 13, 732 (2023).

Leite, F., Reinhardt, T., Bannantine, J. & Stabel, J. Envelope protein complexes of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and their antigenicity. Vet. Microbiol. 175, 275–285 (2015).

Eren, E. et al. Structural characterization of the Myxococcus xanthus encapsulin and ferritin-like cargo system gives insight into its iron storage mechanism. Structure 30, 551–563 (2022).

Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007).

Snijder, J. et al. Assembly and mechanical properties of the cargo-free and cargo-loaded bacterial nanocompartment encapsulin. Biomacromolecules 17, 2522–2529 (2016).

Almeida, A. V., Carvalho, A. J. & Pereira, A. S. Encapsulin nanocages: protein encapsulation and iron sequestration. Chem. Soc. Rev. 448, 214188 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. PNMA2 forms immunogenic non-enveloped virus-like capsids associated with paraneoplastic neurological syndrome. Cell 187, 831–845 (2024).

Roos, G., Foloppe, N. & Messens, J. Understanding the pK(a) of redox cysteines: the key role of hydrogen bonding. Antioxid. Redox Signal 18, 94–127 (2013).

Rao, M., Streur, T., Aldwell, F. & Cook, G. Intracellular pH regulation by Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Microbiology 147, 1017–1024 (2001).

Loiseau, L. et al. Analysis of the heteromeric CsdA-CsdE cysteine desulfurase, assisting Fe-S cluster biogenesis in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26760–26769 (2005).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Jones, D. & Cozzetto, D. DISOPRED3: precise disordered region predictions with annotated protein-binding activity. Bioinformatics 31, 857–863 (2015).

Mu, J., Pan, Z. & Chen, H. Balanced solvent model for intrinsically disordered and ordered proteins. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 5141–5151 (2021).

Brodsky, S. et al. Intrinsically disordered regions direct transcription factor in vivo binding specificity. Mol. Cell 79, 459–471 (2020).

Blauenburg, B. et al. Crystal structure of bacillus subtilis cysteine desulfurase SufS and its dynamic interaction with Frataxin and Scaffold Protein SufU. PLoS ONE 11, e0158749 (2016).

Dunkle, J., Bruno, M., Outten, F. & Frantom, P. Structural evidence for dimer-interface-driven regulation of the type II cysteine desulfurase, SufS. Biochemistry 58, 687–696 (2019).

Fernández, F. J. et al. Mechanism of sulfur transfer across protein–protein interfaces: the cysteine desulfurase model system. ACS Catal. 6, 3975–3984 (2016).

Dai, Y. & Outten, F. W. The E. coli SufS-SufE sulfur transfer system is more resistant to oxidative stress than IscS-IscU. FEBS Lett. 586, 4016–4022 (2012).

Imlay, J. A. Iron-sulphur clusters and the problem with oxygen. Mol. Microbiol. 59, 1073–1082 (2006).

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E. & Noble, W. S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49 (2015).

Addo, M. A., Edwards, A. M. & Dos Santos, P. C. Methods to investigate the kinetic profile of cysteine desulfurases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2353, 173–189 (2021).

Kessler, D. Enzymatic activation of sulfur for incorporation into biomolecules in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 825–840 (2006).

Bailey, T., Zakharov, L. & Pluth, M. Understanding hydrogen sulfide storage: probing conditions for sulfide release from hydrodisulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 10573–10576 (2014).

Han, S., Li, Y. & Gao, H. Generation and physiology of hydrogen sulfide and reactive sulfur species in bacteria. Antioxidants 11, 2487 (2022).

Adamson, L. et al. Pore structure controls stability and molecular flux in engineered protein cages. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl7346 (2022).

Ogata, S. et al. Persulfide biosynthesis conserved evolutionarily in all organisms. Antioxid. Redox Signal 39, 983–999 (2023).

Mironov, A. et al. Mechanism of H2S-mediated protection against oxidative stress in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6022–6027 (2017).

Berglin, E. H. & Carlsson, J. Potentiation by sulfide of hydrogen peroxide-induced killing of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 49, 538–543 (1985).

Cheng, R. et al. Single-step replacement of an unreactive C-H Bond by a C-S bond using polysulfide as the direct sulfur source in anaerobic ergothioneine biosynthesis. ACS Catal. 10, 8981–8994 (2020).

Olson, K. R. Reactive oxygen species or reactive sulfur species: why we should consider the latter. J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb196352 (2020).

Jormakka, M. et al. Molecular mechanism of energy conservation in polysulfide respiration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 730–737 (2008).

He, D. D. et al. Structural characterization of encapsulated ferritin provides insight into iron storage in bacterial nanocompartments. eLife 5, e18972 (2016).

Pi, H. et al. Clostridioides difficile ferrosome organelles combat nutritional immunity. Nature 623, 1009–1016 (2023).

Hudspeth, J. et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of Staphylococcus aureus cysteine desulfurase complex SufSU. ACS Omega 7, 44124–44133 (2022).

Siegel, L. M. A direct microdetermination for sulfide. Anal. Biochem. 11, 126–132 (1965).

Scheres, S. H. W. A Bayesian view on cryo-EM structure determination. J. Mol. Biol. 415, 406–418 (2012).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Grigorieff, N. Frealign: an exploratory tool for single-particle cryo-EM. Methods Enzymol. 579, 191–226 (2016).

Punjani, A., Zhang, H. W. & Fleet, D. J. Non-uniform refinement: adaptive regularization improves single-particle cryo-EM reconstruction. Nat. Methods 17, 1214–1221 (2020).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010).

Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 (1997).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Goddard, T. D. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018).

The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, PyMOL, Schrodinger, LLC; https://pymol.org. (2015)

Tang, Y. et al. The structural and functional analysis of mycobacteria cysteine desulfurase-loaded encapsulin [Data set]. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14015422 (2024).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bio-Electron Microscopy Facility of ShanghaiTech University and Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. We also thank Jinzhi Zhao and Chao Peng of Shanghai Baizhen Biotechnologies for mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201033 to Y.T. and 32171259 to X.L.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M711703 to Y.T.), Major Project of Guangzhou National Laboratory (GZNL2024A01024 to X.L.) and Shanghai Rising-Star Program (23QA1406400 to Y.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zihe Rao supervised the study. Yanting Tang, Xiang Liu, and Yan Gao designed the study. Yanting Tang, Yanyan Liu, and Mingjing Zhang performed the biochemical experiments. Xiang Liu, Yanting Tang, Yanyan Liu, Mengyuan Ma, Cheng Chen, and Saibin Wu collected and processed crystal data. Mingjing Zhang, Weiqi Lan, Yanting Tang, and Yan Gao collected and processed cryo-EM data. Yanting Tang, Xiang Liu, Yanyan Liu, Mingjing Zhang, Rong Chen, Yiran Yan, Lu Feng, and Ying Li analyzed the data. Yanting Tang, Xiang Liu, Yan Gao, and Luke W Guddat wrote and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Jon Marles-Wright and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Janesh Kumar and Laura Rodríguez Pérez. [A peer review file is available.]

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, M. et al. The structural and functional analysis of mycobacteria cysteine desulfurase-loaded encapsulin. Commun Biol 7, 1656 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07299-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07299-8