Abstract

The frequency of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups (mtDNA-HG) in humans is known to be shaped by migration and repopulation. Mounting evidence indicates that mtDNA-HG are not phenotypically neutral, and selection may contribute to its distribution. Haplogroup H, the most abundant in Europe, improved survival in sepsis. Here we developed a random forest trained model for mitochondrial haplogroup calling using data procured from GWAS arrays. Our results reveal that in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, HV branch were found to represent protective factors against the development of critical SARS-CoV-2 in an analysis of 14,349 patients. These results highlight the role of mtDNA in the response to infectious diseases and support the proposal that its expansion and population proportion has been influenced by selection through successive pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) discovered in Wuhan, China, in 2019, represented a global pandemic, responsible for around 18.2 million deaths worldwide, considering only a period between Jan 1st, 2020, and Dec 31st, 20211. Although, being SARS-Cov-2 the latest pandemic with severe consequences, throughout history mankind has been confronted with several infectious agents, which have shaped our genotype. By extension this selective process has also shaped the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), and the components encoded by it. From this perspective, mitochondrial haplogroup (HG) markers are variations in mtDNA accumulated in human populations due to matrilineal inheritance, that allows to trace individuals ancestry and the classification of individuals into HGs2. Several of these HG markers determine amino acid changes in subunits encoded by mtDNA of the oxidative phosphorylation system (OxPhos). The OxPhos system represent an actual hub of integration of cell metabolism, that must adapt to several physiological situations3.

Although most genetic studies analyzing susceptibility and severity to human infectious diseases have focused on the immune system4, there is evidence for the influence of mitochondrial HG on survival to sepsis, relative to the degrees of heating that individuals can afford5. It is known that the severity of SARS-CoV-2 is highly correlated with the comorbidities, age and sex of the patients6,7. Therefore, in relation to these known risk factors, in this study we demonstrate the relevance of mitochondrial HV branch (HGs H, V and HV) as protective factor for SARS-CoV-2 severity independent of general genetic background, comorbidities, age or sex, reinforcing the idea that mitochondria play a relevant role in the outcome of infectious disease.

Results

Development of a machine learning model to perform HG calling

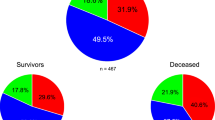

The mitochondrial HGs were identified using a random forest model trained on the genotypes of 189 positions/probes from our GWAS array, as features. These probes were selected based on two criteria: they cover HG markers as defined by MITOMAP, and they demonstrate sufficient probe quality. This model was initially trained on 61,134 sequences from the MITOMAP database. These sequences were pre-labeled using Haplogrep2, which leverages HG markers across the entire mitochondrial genome, rather than just the 189 positions that constituted our training dataset. We subsequently validated our random forest model externally by applying the same 189 positions to individuals from the 1000 Genomes Project8, who were similarly labeled using Haplogrep29, based on full mitochondrial sequence data (Fig. 1, see methods). This approach allowed us to determine mitochondrial HGs with a level of reliability determined by 3-fold cross-validation (3-fold CV) in training data-set by Cohen’s kappa coefficient, κ = 0.98. On the other hand, the accuracy obtained in external validation was κ=0.95. Therefore, this machine learning approach has enough accuracy to determine the HG of our samples. Thus, using this ad hoc tool, we performed mitochondrial HG calling of the 14,349 patients participating in this study obtaining the HG distribution (Table 1).

The left panel shows the strategy for training a random forest model to classify subjects into mitochondrial HGs, while the right panel outlines how to perform external validation of the trained random forest model. *This process of 3-fold cross-validation (3-fold CV) is different from the 3-fold CV fine-tuning search of hyperparameters.

Analysis of HG as independent risk factors for COVID-19 severity

Then, we evaluated HGs as independent risk/protective factors of COVID-19 severity from comorbidity, genetic background, sex, and age. As we only had comorbidity data for the SCOURGE cohort (cases), the analysis was performed in two ways, first considering the SCOURGE cohort and then including the control patients in the analysis. When analyzing the SCOURGE cohort only 8,778 out of 8,894 have comorbidity information. In a first step, regressors to be considered were filtered out according to their significance in univariate models. This univariate analysis conducted using a logistic regression model as the initial step, revealed that out of all the considered HGs, only the HV branch emerged as a protective factor against severe disease (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, the univariate analysis of comorbidities indicated that a history of vascular, digestive, onco-hematologic, and respiratory diseases were risk factors, while a history of neurological disease appeared protective. Cardiac disease history was not significant in our cohort (Supplementary Table S1). Among the 10 principal components representing genetic background, only PC1 and PC3 were significant (Supplementary Table S1). As expected, age was a risk factor for disease severity, as well as sex also emerged as a risk factor in the same direction to that previously described by other authors7. Then, to generate a more robust global multivariate model, avoiding possible collinearities and problems derived from the excessive complexity of multivariate models, the global model was built based on the evidence collected from partial multivariate models. Therefore, given the significant risk factors identified before, the independence of the HV branch as a protective factor against severe disease was evaluated initially across four different settings, resulting in four distinct multivariate models. These models assessed the HV branch's independence in relation to comorbidities, genetic background, age, and sex (Supplementary Table S2). Firstly, in multivariate model considering significant comorbidities, the HV branch remained a protective factor against vascular or respiratory comorbidities, while neurological comorbidities also remained protective. The multivariate model for genetic background revealed that both the HV branch and PC1 had protective main effects. Interestingly, when examining the HV branch's independent effect concerning sex, the HV branch was not significant, while the risk effect for sex persisted in this population (Supplementary Table S2). However, a significant female bias for the HV branch was observed (Fisher test: OR=0.898, CI=0.825-0.977, p-value=0.0118). Then, we explore the univariate analysis of the interaction between the HV branch and sex, that showed a similar trend (OR=1.965; CI=1.719-2.242), indicating that males with the HV branch had almost twice probability of developing severe COVID-19. Lastly, in the multivariate model with age, the HV branch maintained its protective effect, and the expected increased risk due to aging was observed (Supplementary Table S2).

By combining the findings from all these multivariate models, the global multivariate model confirmed the same effects for all features, with the HV branch being independently protective against SARS-CoV-2 severity (Table 2). Furthermore, we tested the relevance of HV branch, comparing nested models deleting the HV branch from multivariate model, using ANOVA test, confirmed the relevance and strength of mitochondrial HV branch condition as protective factor (p<0.01**).

Once the regressor effects of mitochondrial HGs on the severity of COVID-19 in the SCOURGE cohort were analyzed, we proceeded to their evaluation, also including all the patients (Cases+Controls=14,379 patients), repeating the same strategy. Information on comorbidities is lost in this analysis. Additionally, the models were adjusted to account for potential population stratification arising from the management of different cohorts (with cases represented by the SCOURGE cohort and controls). This was addressed by applying mixed-effects models. These mixed models are crucial for ensuring that the results of HG association are robust, reliable, and accurately reflect true biological relationships rather than being influenced by population structure artifacts. Univariate analysis of all considered features, leave that HGs HV branch, I, U, K and J showed correlation with disease severity, having HV branch and I a protective role, being HGs U, K and J risk factors (Supplementary Table S3). Regarding genetic background as principal components, all PCs were significant but PC2 and PC7, that were discarded for downstream analysis (Supplementary Table S3). Finally, as observed when analyzing SCOURGE cohort, age and sex were risk factors and in the same direction, (Supplementary Table S3). Next, significant HGs were evaluated in multivariate models to check independent effects in 3 frames: regarding sex, age and genetic background, (Supplementary Table S4). Evaluating the independent effects of HGs and sex on disease severity, only the HV branch emerged as a significant protective factor, independent of sex (Supplementary Table S4). Exploring the existence of significant interactions between both features, it was found that there were not significant interactions (ANOVA over nested models: p-value=1). In partial scenario analyzing HGs and age, again only HV branch was selected as protective feature in the multivariate model obtained, not showing interaction with age (ANOVA for nested models: p-value=0.424). Finally, in multivariate model considering genetic background context, again HV branch was the only HG explanatory for SARS-Cov2 severity, joined with PC1 and PC3, showing interaction with PC1 (ANOVA over nested models: p-value<0.01**), as also was observed when analyzing only SCOURGE cohort (Supplementary Table S4). Gathering the performance of regressors in these three frames, a global multivariate model was assembled, confirming protective role of HV branch in this disease, as well as the fact that its effect is different depending on the genetic background, as observed by the significance of the interaction between PC1 and HV branch (Table 3).

Analysis of energy changes in in silico models determined by major haplogroup markers

Next, to assess the potential structural impact of missense variants identified by major HG markers, we analyzed the energy variations they cause within in silico models following rosetta Flex-ddG protocol10. Regarding these in silico results calculated with respect to the reference mtDNA sequence11, in HGs J and T respiratory complex I (CI) showed a significant stabilization, while HG K presented a significant destabilization, remaining HV branch HG U and T unaltered (Fig. 2, left panel). All analyzed HGs presented significant levels of destabilization for complex III (CIII2), except for HV branch (Fig. 2, middle panel). Finally, in complex V (CV), only HG K presented a significant destabilization (Fig. 2, right panel). No major HG markers causing missense variations are affecting complex IV genes.

All HGs are compared to a reference model determined according to the Cambridge reference sequence (NC_012920). Only mitochondrial HGs that were significant risk modulators for SARS-Cov2 severity are represented. According to the developers of the rosetta Flex.ddG protocol, significant energetic changes can be considered above or below ± 1 Kcal/mol (red lines). Although CIV also contains three subunits encoded by mtDNA, this respiratory complex is not represented, as none of the described mitochondrial HG markers produce amino acidic changes.

Discussion

Since 2019, the global pandemic caused by the SARS-Cov-2 virus (COVID-19) spread rapidly with serious implications all around the world. However, humans have faced numerous pandemics and epidemics, which likely acted as a selective force in human evolution. By the same token, HG H (largest representation of the HV branch) is the most frequent HG in European population, representing 37–58%12. However, in a study performed in 54 individuals from Upper Paleolithic and Early Neolithic from Northern Spain, ancient hunter-gatherer samples were mainly from HG U (50-80%), while later Neolithic samples resulted more heterogeneous differing on their proportions in HGs J, U and H13. Viewed in this way, since the HG H arrived in Europe from the Near East (22,000 BP), HG H increased its proportion, being almost 19% in Linear Pottery Culture (Neolithic), increasing the frequency to a 44% during Neolithic as observed in samples from the Basque Country and Navarre13,14. Nevertheless, the HG H has undergone a multifaceted and dynamic history in Europe, shaped by migrations, demographic shifts, and possibly selective pressures such diseases. In this study we explore the hypothetical contribution of disease linked selective pressures. Thus, in Europe, HG H has become in a relatively short evolutionary period, the most frequent one. To preserve such a high frequency, HG H may provide some evolutionary advantage, constituting a clear example of evolutionary selection during historical time in human evolution. In this process of selective sweep, pandemic/epidemic events must have been an important keystone. In this context, Yersinia pestis is one of the deadliest pathogens for humans. During the second pandemic (Black Death) alone, it wiped out at least 30% of the European population, illustrating how a pandemic can influence the genetic landscape related to immune response. However, to date, there is no consistent evidence linking this to mitochondrial HGs4.

In this regard, although survival to infectious diseases is a multi-factorial issue, the advantage conferred by HG H in pandemics/epidemics could be a relevant factor. As an example, Chinnery et al, described an overcome in survival to sepsis event in ICU patients by HG H patients compared against remaining HGs5. They reported that HG H patients could withstand a higher core temperature than the rest of the HGs, so they proposed fever as a possible cause of the survival differences.

Interferon release by virus infected cells is part of the innate immune response, that promotes several pathways to control virus replication/infection15. Bearing this in mind, it is known that fever enhances the immune response against virus infection, boosting both innate and adaptive immune response to virus16,17,18,19,20. In the same direction, it is known that the use of antipyretics is associated with increased mortality21,22,23. The fever produces shivering as part of the strategy of increasing core temperature, that increases metabolic rate sixfold above basal levels24, where mitochondria have a key role in heat production. It is known, that sustained high temperature above the physiological threshold (heat stress) can induce permanent mitochondrial dysfunction that leads to cytotoxic ROS production triggering cell death25,26. Furthermore, it has been described recently, that respiratory complexes, especially complex I and structures derived from respiratory complexes assembly called supercomplexes are unstable at temperatures above 43ºC, both in intact cells and isolated mitochondria27. As a result, greater resilience to sustained high temperatures could be evolutionarily favored for combating infectious diseases, particularly through changes that reduce OxPhos capacity fatigue, such as mutations in OxPhos structures associated with certain HG markers. In this context, a recent study has shown that elevated temperature (39 ºC) significantly influences the metabolism of the electron transport chain (ETC), particularly impacting complex I. This leads to increased ROS production and the activation of selective apoptosis in TH1 lymphocytes28. TH1 cells play a critical role in cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens, especially through the production of INF-γ in response to viral infections. As a result, variations in tolerance to hyperthermia, caused by small structural differences determined by mitochondrial HGs, could directly affect the effectiveness of TH1-mediated antiviral responses.

In this study, we confirmed that HGs significantly influence the severity of SARS-CoV-2, with the HV branch specifically having a protective role. This remains relevant today, as its effects are still evident, despite significant medical advances in combating infectious diseases that have reduced the correlation between susceptibility, severity, and survival.

Regarding the flex-ddG analysis, it is important to note that the HG markers analyzed are highly prevalent in human populations, so that under normal physiological conditions they would not represent any decrease in OxPhos fitness. However, under extreme conditions such as hyperthermia, tolerable differences in RCs’ stability under normal physiological conditions, could represent a real decrease in stability and a key role in disease outcome. Interestingly, only the HV branch shows no significant destabilization in any RC induced by top-level HG markers. It is important to notice that Flex-ddG in silico analysis has the limitation that the same genetic background is used, making it impossible to rule out that the observed effects are due to specific mito-nuclear interaction with this nuclear environment of the OxPhos system. However, this same limitation is accepted for the use of cybrid models, a technology widely used to precisely determine mitonuclear interactions. However, the goal of our Flex-ddG modeling was to generate in silico mechanistic hypotheses based on observations of the analyzed population.

In the same line of our outcomes, it has been described that HG markers linked to HG H as 7028C is protective against severe COVID-19 disease29. The results provided by our multivariate model, based on data drawn from such a large cohort of patients, provide important evidence for the role of mitochondrial HGs as modulating factors in the risk of developing the severe form of the disease, regardless of the genetic background, comorbidities, age or sex of the patients. In addition, from an evolutionary perspective, these outcomes confirm the relevance of H30 and furthermore OxPhos genotype in the defense to an infectious pathogen.

Methods

Sample processing and genotyping

Data from a total of 11,977 COVID-19-positive cases were recruited as part of the SCOURGE study (https://www.scourge-covid.org) from 34 hospital or research centers across Spain between March and December 2020. Samples and data were collected by the participating centers through their respective biobanks after informed consent. The whole project was approved by the Galician Ethical Committee, ref.: 2020/197. Additionally, 5,943 people with unknown COVID-19 status were included as population controls: 3,437 samples from the Spanish DNA biobank (https://www.bancoadn.org) and 2,506 samples from the GR@CE consortium. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

Genomic DNA was obtained from peripheral blood and isolated using the Chemagic DNA blood100 kit (PerkinElmer Chemagen Technologies GmbH), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Genotyping was performed using the Axiom Spain Biobank Array (Thermo Fisher scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions in the Santiago de Compostela Node of the National Genotyping Center (CeGen-ISCIII). This array contains 757,836 markers and is enriched in rare variants selected in the Spanish population.

Details concerning the sample processing and quality control can be found in the first report describing the European GWAS of this consortium31. All individuals included in the analysis were of European ancestry. Ancestry was inferred with Admixture32 using defined 1KGP superpopulations. Those individuals with an estimated probability >80% of pertaining to European ancestry were defined as European (N=15,571)31. After down-sampling individuals with missing values for disease severity, sex or age, we obtained an effective dataset of 14,349 individuals (8,894 COVID-19 positive cases and 5,455 population controls). In these individuals’ genomic principal components (PCs) were computed using a LD-pruned (r2 < 0.1 with a window size of 1000 markers) subset of genotyped SNPs passing quality check for controlling the population structure in the posterior analyses (Fig. 3).

HG calling using machine learning

We developed an ad hoc method to perform mitochondrial HG calling from GWAS array data, based in machine learning (Fig. 1). The Axiom Spain Biobank Array covers up to 231 mitochondrial confident positions. Around 189 out of these 231 positions were positions linked to HG markers and the probes that define the genotype in our array have enough quality. Our goal was to train a random forest classifier using 189 positions (which define the variables for the random forest) from 61,134 HG-labeled sequences obtained from the Mitomap database. We employed 3-fold cross-validation to fine-tune the model's hyperparameters (Fig. 1, left panel). The hyperparameters were restricted to the number of variables randomly sampled as candidates at each split (5, 10, 20, 40, or 60). Model error was first assessed using a 3-fold cross-validation loop on the training dataset, with hyperparameter fine-tuning conducted within each cycle (obtained by nested cycles of 3-fold CV, mentioned before). Thus, the error was measured as the mean of Cohen’s kappa calculated for each cross-validation cycle. Next, external validation of this model was undertook using Publicly available data from the third phase of 1,000 genome project8. In this samples, the SNPs collected from full length mtDNA were used to call HG using haplogrep29. Finally, we use our model to predict HGs in our 14,749 patients, based on genotype information for the 189 positions. (Fig. 1, right panel). An app powered by shiny (https://shiny.posit.co/) will be available at https://github.com/Cabrera-alarcon/GENOXPHOS.

Analysis of HGs as independent risk factors

To assess the value of HGs as independent risk factor for the severity of SARS-CoV-2, we analyzed only HGs with frequencies >1% (H, HV, V, J, T, U, K, I, W and X). Severe disease development was considered for patients with fatal outcome, admission to the ICU or the need for mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive). Additionally, HGs were connected by branches based on top-level MITOMAP HG markers (present in ≥80% of HGs) that result in amino acid changes in mitochondrial DNA encoded OxPhos subunits. The missense status of these top-level HG markers was predicted using the variant effect predictor33 (Supplementary Data 1). As a result, HGs H, V, and HV were grouped together under the HV branch.

Then we assessed explanatory meaning of HGs for SARS-Cov2 severity in two groups, the SCOURGE cohort (those are our case group, for which we have comorbidity information for 8,778 out of 8,894) and the global group of patients represented by the SCOURGE+Control patients (8,894+5,455).

Initially, we examined the impact of potential explanatory variables by fitting a univariate logistic regression model to study these effects in the SCOURGE cohort. For the analysis across all patients, we employed a mixed-effects logistic regression model to account for the population stratification into cases and controls as a random effect. To fit such mixed-effects models we used lme4 v-1.-35.3 R-package34. Five groups of features were considered, HGs, comorbidities, genetic background, sex and age. The comorbidities were represented by the patient's cardiac history (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia or peripheral vascular disease), vascular history (arterial hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, uncomplicated diabetes mellitus, diabetes mellitus with visceral repercussions, obesity), digestive antecedents (Peptide ulcer, Chronic liver disease without portal hypertension, Chronic liver disease with portal hypertension), nervous system antecedents (Cerebrovascular disease such as infarction or hemorrhage without sequelae or minimal sequelae, with hemiplegia or paraplegia, dementia or other neurological disease), respiratory history (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or other chronic respiratory disease) and oncological or oncohematological history (localized solid tumor, metastatic solid tumor, leukemia, lymphoma or bone marrow/hematopoietic precursor transplant). The genetic background was estimated as to summarize genetic variability as the 10 principal components determined from genotype matrix. Since many of these variables were dichotomous and the quantitative variables (genetic background and age) were on very different scales, a min-max normalization of the data was performed.

Next, the regressors that were significant in univariate models were evaluated by assembling multivariate models. Initially, we assessed the significant HGs from the univariate models across four different scenarios, resulting in four distinct multivariate models. These models tested the independent effects of the HGs: one considering only comorbidities (in the SCOURGE cohort), one accounting for genetic background, another checking for independent effects with sex and age. During this process, feature selection was conducted using a stepwise backward strategy, reducing the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for the main effects. Once the features were selected, potential interactions between HGs and other features were explored by analyzing the relevance of their inclusion in the model through ANOVA tests comparing nested models. The same strategy was applied to evaluate the importance of including HGs in the final models. Finally, based on the information obtained from these partial multivariate models, a global model was fitted, both when considering only SCOURGE cohort and when studying SCOURGE+Controls. In these models, stratification of analyzed population was considered as aleatory effect. In all models a threshold for significance of 0.05 was adopted.

Analysis of energy changes in in silico models determined by major HG markers

Further analyses were performed to evaluate in our in-silico models (Cabrera-Alarcon & Enriquez, manuscript submitted), to assess whether observed results of significant HGs from multivariate mixed effect logistic regression correlate with changes in OxPhos complexes stability by analyzing residue changes determined by major HG markers gathered from MITOMAP. Structural consequences oh HG markers were determined using Variant Effect Predictor33. For this purpose, changes in the strength that bind subunits assembled in OxPhos complexes due to residue changes were studied following the rosetta Flex-ddG protocol10. According to developers of this tool significant energy changes can be considered from ±1 Kcal/mol.

Data availability

All data used to develop machine learning models are publicly available in Mitomap: (https://www.mitomap.org/foswiki/bin/view/Main/WebHome) and The International Genome Sample Resource (https://www.internationalgenome.org), and materials that are not available in the main text, the supplementary materials or github repository will be available upon request. Summary statistics from the SCOURGE Latin-American GWAS will be available at https://github.com/CIBERER/Scourge-COVID19. Raw genotype or phenotype data cannot be made available due to restrictions imposed by the ethics approval.

Code availability

Code use in this study will be available at https://github.com/Cabrera-alarcon/GENOXPHOS.

References

Collaborators, C.-E. M. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020-21. Lancet 399, 1513–1536 (2022).

Cann, R. L., Stoneking, M. & Wilson, A. C. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature 325, 31–36 (1987).

Cogliati, S., Cabrera-Alarcon, J. L. & Enriquez, J. A. Regulation and functional role of the electron transport chain supercomplexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 49, 2655–2668 (2021).

Klunk, J. et al. Evolution of immune genes is associated with the Black Death. Nature 611, 312–319 (2022).

Baudouin, S. V. et al. Mitochondrial DNA and survival after sepsis: a prospective study. Lancet 366, 2118–2121 (2005).

Marusic, J., Haskovic, E., Mujezinovic, A. & Dido, V. Correlation of pre-existing comorbidities with disease severity in individuals infected with SARS-COV-2 virus. BMC Public Health 24, 1053 (2024).

Pijls, B. G. et al. Demographic risk factors for COVID-19 infection, severity, ICU admission and death: a meta-analysis of 59 studies. BMJ Open 11, e044640 (2021).

Genomes Project, C. et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).

Weissensteiner, H. et al. HaploGrep 2: mitochondrial haplogroup classification in the era of high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W58–W63 (2016).

Barlow, K. A. et al. Flex ddG: Rosetta ensemble-based estimation of changes in protein-protein binding affinity upon mutation. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 5389–5399 (2018).

Andrews, R. M. et al. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147 (1999).

Rishishwar, L. & Jordan, I. K. Implications of human evolution and admixture for mitochondrial replacement therapy. BMC Genomics 18, 140 (2017).

Hervella, M. et al. Ancient DNA from hunter-gatherer and farmer groups from Northern Spain supports a random dispersion model for the Neolithic expansion into Europe. PLoS ONE 7, e34417 (2012).

Brotherton, P. et al. Neolithic mitochondrial haplogroup H genomes and the genetic origins of Europeans. Nat. Commun. 4, 1764 (2013).

Fensterl, V. & Sen, G. C. Interferons and viral infections. Biofactors 35, 14–20 (2009).

Evans, S. S., Repasky, E. A. & Fisher, D. T. Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 335–349 (2015).

Kluger, M. J., Ringler, D. H. & Anver, M. R. Fever and survival. Science 188, 166–168 (1975).

Lane, W. C. et al. The efficacy of the interferon alpha/beta response versus arboviruses is temperature dependent. mBio 9, e00535-18 (2018).

Prow, N. A. et al. Lower temperatures reduce type I interferon activity and promote alphaviral arthritis. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006788 (2017).

Torres, A. R. Is fever suppression involved in the etiology of autism and neurodevelopmental disorders? BMC Pediatr. 3, 9 (2003).

Kurosawa, S., Kobune, F., Okuyama, K. & Sugiura, A. Effects of antipyretics in rinderpest virus infection in rabbits. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 991–997 (1987).

Ryan, M. & Levy, M. M. Clinical review: fever in intensive care unit patients. Crit. Care 7, 221–225 (2003).

Schulman, C. I. et al. The effect of antipyretic therapy upon outcomes in critically ill patients: a randomized, prospective study. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt.) 6, 369–375 (2005).

Horvath, S. M., Spurr, G. B., Hutt, B. K. & Hamilton, L. H. Metabolic cost of shivering. J. Appl Physiol. 8, 595–602 (1956).

Slimen, I. B. et al. Reactive oxygen species, heat stress and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. A review. Int J. Hyperth. 30, 513–523 (2014).

Zhao, Q. L., Fujiwara, Y. & Kondo, T. Mechanism of cell death induction by nitroxide and hyperthermia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40, 1131–1143 (2006).

Moreno-Loshuertos, R. et al. How hot can mitochondria be? Incubation at temperatures above 43 degrees C induces the degradation of respiratory complexes and supercomplexes in intact cells and isolated mitochondria. Mitochondrion 69, 83–94 (2023).

Heintzman, D. R. et al. Subset-specific mitochondrial stress and DNA damage shape T cell responses to fever and inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 9, eadp3475 (2024).

Vazquez-Coto, D. et al. Common mitochondrial haplogroups as modifiers of the onset-age for critical COVID-19. Mitochondrion 67, 1–5 (2022).

Wallace, D. C. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human radiation and disease. Cell 163, 33–38 (2015).

Cruz, R. et al. Novel genes and sex differences in COVID-19 severity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 31, 3789–3806 (2022).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19, 1655–1664 (2009).

McLaren, W. et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. M. Muñoz-Hernandez, R. Martínez de Mena and E.R. Martínez Jiménez, for technical assistance. Scheme figures were made with BioRender. We particularly acknowledge all the patients, Banco Nacional de ADN, Biobanco del Sistema de Salud de Aragón, Biobanc Fundació Institut d'Investigació Sanitària Illes Balears, Biobanco del Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago, Biobanco Vasco, for their collaboration and providing materials. JAE laboratory is supported by: RTI2018-099357-B-I00 and PID2021-1279880B-and TED2021-131611B-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the, and CIBERFES (CB16/10/00282), Human Frontier Science Program (grant RGP0016/2018), and Leducq Transatlantic Networks (17CVD04). MR-M is supported by a FPI/PRE2021-097721 fellowship. JAE and FSC are supported by TED2021-131611B-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union “NextGenerationEU”/Plan de Recuperación Transformación y Resiliencia -PRTR. FSC received funding [grant no. PID2022-141527OB-I00] by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and by FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa. This work was supported by Fundación Amancio Ortega Gaona, Banco de Santander S.A. and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (COV20/00622) and the European Regional Development Fund. Genotyping service was carried out at CEGEN-PRB3-ISCIII, supported by grant PT17/0019, of the PE I+D+i 2013-2016, funded by ISCIII and ERDF. The CNIC is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN) and the Pro CNIC Foundation) and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (grant CEX2020-001041-S funded by MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.L.C.-A., R.C., F.S.-C., A.C., J.A.E. Methodology: J.L.C.-A., M.R.-M., R.C., A.L.-P. Investigation: J.L.C.-A., M.R.-M. Visualization: J.L.C.-A., J.A.E. Funding acquisition: F.S.-C., J.A.E. Project administration: S.D.A., J.A.R., A.R.M., C.F., P.L. Sample Providers: S.C.G. Supervision: A.C., J.A.E. Writing—original draft: J.L.C.-A., F.S.-C., J.A.E. Writing—review and editing: All Authors

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Ani Manichaikul and Tobias Goris. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cabrera-Alarcon, J.L., Cruz, R., Rosa-Moreno, M. et al. Shaping current European mitochondrial haplogroup frequency in response to infection: the case of SARS-CoV-2 severity. Commun Biol 8, 33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07314-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-07314-y