Abstract

Cell movement on surfaces relies on focal adhesion complexes (FAs), which connect cytoskeletal motors to the extracellular matrix to produce traction forces. The soil bacterium Myxococcus xanthus uses a bacterial FA (bFA), for surface movement and predation. The bFA system, known as Agl-Glt, is a complex network of at least 17 proteins spanning the cell envelope. Despite understanding the system dynamics, its molecular structure and protein interactions remain unclear. In this study, we utilize AlphaFold to generate models based on the known interactions and dynamics of gliding motility proteins. This approach provides us with a comprehensive view of the interactions across the entire complex. Our structural insights show the connection of essential functional modules throughout the cell envelope and offer an inspiring view of the force transduction mechanism from the inner molecular motor to the exterior of the cell.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

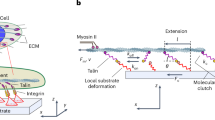

Cell motility on surfaces universally depends on focal adhesion complexes (FAs), where cytoskeletal motors physically connect to the extracellular matrix to generate traction forces. In eukaryotic focal adhesion complexes (eFAs), forces produced by actomyosin motors are transmitted to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through direct connections to surface-exposed proteins, primarily integrins and membrane-associated proteins. eFAs also include signal transduction proteins, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), which enable dynamic regulation of the complexes (for a review, see ref. 1). This complexity reflects the necessity for cells to sense their environment, move directionally (e.g., chemotaxis), and coordinate motility within multicellular assemblies. Remarkably, bacteria also assemble focal adhesion complexes (bFAs) that similarly connect molecular motors to surface adhesins to generate traction forces. However, in bacteria, force transduction is further complicated by the multilayered cell envelope: the motors reside in the bacterial inner membrane (IM), while the adhesins are displayed on the surface of the outer membrane (OM). In this study, we analyze the trans-envelope architecture of bFAs, delineating a possible force transduction pathway across the cell envelope.

Myxococcus xanthus a deltaproteobacterial soil predator uses bFAs to move across surfaces and invade prey colonies2,3. The bFA machinery (Agl-Glt) was genetically identified as a putative complex of at least 17 proteins predicted to span the entire cell envelope4,5. In motile Myxococcus cells, the Agl-Glt complex is assembled at the leading cell pole (Fig. 1). Following activation of the Agl motor, a predicted TolQR-like proton motive force-driven motor, the motility complex moves in a counter clockwise helical trajectory toward the lagging cell pole3,6,7,8. Once the motility complex contacts the underlying substratum it becomes physically tethered via CglB, a surface exposed terminal adhesin, and forms bFAs that propel a clockwise screw-like movement of the cell forward9. Similar to eFAs, Myxococcus bFAs are subject to complex spatial regulations: they are disassembled at the lagging cell pole, allowing persistent directional movements of the Myxococcus cells10,11, as well as when Myxococcus establish contact with prey cells, which allows contact-dependent killing12. The mechanisms underlying these regulations are only partially elucidated (see below).

A The mechanism of propulsion. Following assembly at the leading cell pole via their recruitment to the cytosolic platform, motor complexes (green dot) move toward the lagging cell pole in a counter-clockwise trajectory. When these complexes encounter the surface they connect to an OM complex containing an adhesin (orange triangle) and become fixed relative to the substrate (red rectangle, depicted at a molecular scale in B). As a result the cell is propelled is a clockwise screw-like movement. B Proposed molecular architecture of the Agl-Glt machinery assembled at bFAs, as proposed prior to this study. The main modules are shown. Demonstrated interactions are depicted in orange. Note that all of the proteins shown including those that do not have assigned function (shown in white) are essential for bFA function. How the IM localized motor physically connects to the OM motor through the peptidoglycan is unknown and could be mediated by a periplasmic complex formed by the GltD, E, F proteins. Figure adapted from Attia et al.17 published under the Licence Creative Commons CC BY.

While the cellular basis of propulsion is now well established, our understanding of the molecular mechanism of assembly and propulsion remains largely fragmentary because a limited number of interactions have been established and the structure of the Agl-Glt complex is currently inferred from its similarities to the E. coli Tol-Pal system13. Currently, the Agl-Glt system is thought to regroup three functional modules assembled in each layer of the cell envelope (Fig. 1):

-

(1)

An outer membrane (OM) complex that promotes adhesion to the underlying substratum and connection to the motor system at bFAs9,14. This complex has been purified after heterologous expression in E. coli and it is arguably better defined in terms of protein interactions. It is formed by OM porin-like proteins GltABH, that form beta barrel structures in the OM and connect with GltC, a predicted Tetratrico Peptide Repeat (TPR) protein on the periplasmic side14 and GltK-CglB, the proposed adhesin at the cell surface9. It is currently unclear how CglB is exposed by the OM complex at the surface and how it becomes physically recruited at bFAs.

-

(2)

A putative periplasmic Glt transducer complex assembled from predicted periplasmic proteins, namely GltD, GltE, GltF, possibly in association with the predicted periplasmic domains of GltG and GltJ. There is currently no biochemical evidence for this complex, which is only predicted from genetic and cell biology evidence showing the functional importance and localization of these proteins at bFAs3,4,7. The current motility model requires that forces be transduced from the Agl motor to the OM, which must require periplasmic connections3. Such a transducer system should be able to propagate a mechanical signal through the bacterial cell wall, and thus adopt a compatible structure. While GltD, E and F are obvious candidates, there is also currently no evidence for interaction of these proteins with the IM motor and the OM complex.

-

(3)

AglRQS, a three-protein molecular motor in the bacterial inner membrane. Based on similarities with TolQ (AglQ) and TolR (AglS and AglR), this motor is proposed to form a channel in the IM and harvest the proton motive force directly to energize a power stroke via conformational transitions of associated IM proteins, possibly GltG and GltJ both of which contain a predicted IM helix that could interact with the channel. However, a direct interaction has only been observed with the putative GltG IM segment in a two-hybrid analysis4.

-

(4)

On the cytoplasmic side, the connections are also quite complex. The evidence supports that the Agl-Glt apparatus interacts with the bacterial MreB actin-like cytoskeleton by a suite of intracellular proteins forming a so-called cytoplasmic platform7,10,11,15,16. This platform ensures spatial activation of the system as well as efficient force transduction. The interaction network is now rather well defined: at the leading cell pole, the Agl-Glt machinery becomes activated by MglA, a Ras-like protein and AglZ, a coiled-coil forming proteins each known to interact with MreB11,15,16. Both proteins bind to two distinct motifs of a cytosolic domain of the GltJ protein17. Specifically, this region contains tandem Zinc Finger (ZnR) and GYF domains separated by a linker region18. Binding of AglZ occurs via the GYF domain while MglA-GTP interacts with a motif of the linker region17. Importantly, MglA-GTP binding to the linker motif is critical for the spatial regulation of the motility complex because it liberates the ZnR from a closed conformation, making it available for interaction. When the motility complex reaches the lagging cell pole, the ZnR recruits the MglB protein, an MglA GTPase-Activating-Protein, which provokes the dissociation of MglA and disassembly of the Motility complex17. Thus, connection with the cytosolic platform control bFAs spatially via MglA and its regulator MglB11,17,19. However, while the interaction network between GltJ, MglA AglZ and MreB is established, how these interactions organize the cytosolic platform remain unknown. In addition, the Agl-Glt system contains other cytosolic proteins/domains that may also engage in the platform, a direct interaction between MglA and AglR has also been observed5 and the N-terminal region of GltG contains a predicted cytoplasmic ForkHead Associated (FHA) domain3,4. Last, the GltI protein a giant 3822 residues long protein containing a large number of TPR domains recruited at bFAs4,5 is also cytoplasmic.

In summary, a deep molecular understanding of the mechanism of propulsion will require:

-

(1)

Elucidating the physical link between the molecular motor and the periplasmic transducer.

-

(2)

Determining how the periplasmic transducer interacts with the OM complex through the peptidoglycan meshwork.

-

(3)

Understanding the basis of directionality and the function of the cytoskeleton.

Resolving these questions cannot be achieved without a deep understanding of the structure-function relationships within the functional modules of the motility machinery. Experimentally, this is a major challenge because the machinery is assembled dynamically at bFAs, a state which could only be captured in live cells3.

The AlphaFold revolution in protein modeling has opened up new possibilities for understanding complex protein assemblages20. AlphaFold can predict the atomic model of these assemblies with high confidence, opening a new era of modeling studies in structural biology. taking advantage of this power, we applied a “reverse modeling approach”: guided by available data, known interactions and localization of proteins within the gliding machinery, we constructed a holistic view of protein interactions at the scale of the entire motility complex. This structural analysis revealed how the terminal adhesin becomes exposed as well as critical periplasmic interactions underlying mechanical transduction in the periplasmic space. From a general perspective, the work paves the way for similar large scale analyses of other complex molecular machines.

Results

The outer membrane (OM) complex

The OM complex can be expressed and purified when expressed in the heterolog host E. coli9. It contains the OM β-barrels GltA,B and H, the OM lipoprotein GltK and the CglB adhesin9. In addition, this OM complex also interacts with the periplasmic protein GltC14. This OM heterocomplex is required for the recruitment and retention of the OM lipoprotein CglB at the bacterial cell surface9. However, it is not clear how it is structurally organized and in particular how it exposes the CglB adhesin at the surface. Based on bioinformatics predictions, it was proposed that GltC and K both localize in the periplasm. GltA and GltB have been shown to interact and each is indispensable to the stable expression of the other9,14. In contrast the role of GltH is elusive in spite of its importance for motility4,5,9.

We therefore predicted the structures of the GltABH complex, the GltABHK-CglB complex (Fig. 2) and finally the GltABHK-CglB-GltC complex (Fig. 3). The Predicted Align Errors (PAE) indicate that the GltABH contacts are significant (Fig. S1). In the three β-barrels complex GltA,B and H, GltA and GltB interact strongly (Fig. 2A): a GltA loop is packed against a GltB α-helix (residues 110–120 and 121–134, respectively) (Fig. 2B), and on the periplasmic side of GltA and GltB, each porin associate a β-hairpin (residues 134–151 and 153–169, respectively) with the other to form a four stranded β-sheet (Fig. 2C). In contrast, such strong contacts are absent between GltAB and GltH. The Buried Surface Area (BSA), a measure of the strength of the interaction between proteins, is large between GltA and GltB and between GltB and GltH (>900 Å2) but smaller between GltA and GltH (>400 Å2, Table S2A). These predictions are highly in line with previous results and suggest that core interactions of the OM complex are maintained by GltA and GltB, with GltH as an accessory component.

A Ribbon side-view of the interactions between three outer membrane porins GltA, B and H complex. B View from top with respect to (A). C View from bottom with respect to (A). D Surface side-view of the three outer membrane porins complex. Same orientation as in (A). E Ribbon side-view of the three outer membrane porins complex GltA, B, H to which GltK and CglB are attached, providing a complex view of the complex that can be purified from E. coli. Inset i1: close-up view of the β-sheet formed by β-strands from GltK and CglB. Inset i2: close-up view of the β-sheet formed by insertion of a CglB β-strand between β-strands from GltA and GltB porins. F Surface side-view of the GltA, B, H, GltK and CglB complex. The porins GltABH have been colored by hydrophobicity (brown color) indicating the porin/OM contact zone. The OM has been schematically represented (gray). The N-terminal end of CglB forms a N-Acyl bond with a phospholipid schematically represented in red. A–F: OM outer membrane, ext exterior.

A Ribbon side-view of the interactions between the OM complex GltA, B, H, K, CglB and the periplasmic GltC protein. Inset: close-up view of the β-sheet formed by insertion of a GltB β-strand between two β-strands from GltC. B Surface side-view, same orientation as in (A). C Surface side-view, rotated 180° with respect to (B). D Surface side-view of the GltA, B, H, K, C and CglB complex. The porins GltABH have been colored by hydrophobicity (brown color) indicating the porin/OM contact zone. The OM has been schematically represented (gray). E Surface side-view of the OM complex GltA, B, H, K and CglB in interaction with GltC and the GltF C-terminal segment nested within a GltC crevice, viewed from bottom with respect to (C). A–C: OM outer membrane, ext exterior.

The GltABHK-CglB complex also exhibits good PAE, with strong interactions of GltK with the three porins, and of CglB N- and C-termini with GltK and the three porins (Fig. S1). Importantly, the complex reveals the localization of GltK which, contrarily to the original assumption of its periplasmic localization, is observed to cover the external face of GltAB porins, exposing a large surface contact with CglB (Fig. 2E and Table S1A). CglB is a predicted three-domain protein, containing a Lipoprotein sorting signal at the N-terminus, followed by a β-propeller domain, followed by an extracellular VWA domain9. Interaction with GltK occurs largely via the β-propeller domain: the second N-terminal β-strand (residues 12–24) interacts with a GltK β-sheet, which together with three additional N-terminal β-strands from CglB form a seven stranded β-sheet (Fig. 2E, inset i1). CglB also interacts directly with the GltAB complex via its very first N-terminal β-strand (residues 4–9), on one side with a β-hairpin from GltA and on the other side with a β-strand of GltB (Fig. 2E, inset i2). As a result, the Cys N-terminal residue of the mature CglB is in the proper position for aminoacylation to a phospholipid moiety and insertion in the membrane21 (Fig. 2F).

In the GltABHK-CglB-GltC complex, GltC is prominently situated on the periplasmic face of the porin trio (Fig. 3A), and this interaction is also substantiated by good PAE data (Fig. S1A). Consequently, GltC shares interaction surfaces with the three porins (Table S1A). Critically, while the folds adopted by the N-termini of the mature porins are poorly predicted in absence of GltC (Fig. 2), they become structured via their interaction with GltC (Fig. 3A–D).

In this context, a particularly interesting feature is the insertion of the N-terminal β-strand of GltB between two β-strands of GltC, forming a distinctive three-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 3A, inset). Furthermore, a conspicuous elongated crevice is discernible in the central part of GltC. This characteristic prompted further investigations with various putative Glt periplasmic proteins. Among them, GltF (Fig. S1) stands out as it inserts its C-terminal helix into this crevice, a feature that will be explored in greater detail below (Fig. 3E).

The periplasmic complex

Various pivotal motility proteins are anticipated to reside in the periplasm. These include GltD, GltE, GltF, and, as elucidated earlier, GltC3,4,5,7. In contrast, GltG and GltJ feature a trans-membrane helix (TMH) with their N-terminal segments located in the cytoplasm and the C-terminal segments extending into the periplasm. According to TMHMM server predictions, the TMH helices encompass residues 330–348 and 385–405 for GltG and GltJ, respectively. Isolated protein/domain structures were predicted for each (Fig. S2). In accordance with previous findings3,14, GltD harbors a central tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain, flanked at its N- and C-termini by non-TPR helical domains (Fig. S2A). Both the N- and C-termini segments are predicted to be disordered (residues Cys1-76 and 1104-1197). Similarly, GltE possesses a central TPR domain followed by a lengthy helix and is flanked by disordered segments (residues Cys1-27 and 400-455) (Fig. S2B). Conversely, GltF is largely predicted to be disordered (Fig. S2C), with the exception of two helices between residues 55–70 and at the C-terminus (133-147), as mentioned earlier. GltG reveals extensive disordered segments connecting three folded domains (Fig. S2D): a previously predicted N-terminal forkhead-associated domain (FHA; residues 1–114), a newly identified central FHA domain just before the TMH (Residues 190–329; FoldSeek E-value 1.12 10-2; PDB ID 7zc8), and a C-terminal domain resembling a TonB C-terminal domain (Residues 544–640; FoldSeek E-value 1.28 10-2; PDB ID 3gqs22). Finally, GltJ also displays lengthy disordered segments connecting three folded domains (Fig. S2E): a N-terminal zinc-finger (ZnR) domain with a recently described structure (PDB ID 7zok18), a central glycine-tyrosine-phenylalanine domain (GYF) also described recently (PDB ID 7z3c18), and, in the periplasm, a TonB-CTD-like C-terminal domain (Residues 584–674; FoldSeek E-value 2.89 10-2; PDB ID 6sly).

The assembly of a GltCDEFGJ complex was successfully predicted in two sequential steps using AlphaFold, supported by excellent values of Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT), a per-residue measure of local confidence, and of Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) values (Figs. S3 and 4; see “Methods” for additional details). GltD serves as the central pillar, multiply plugged to the other components (Fig. 4). Notably, a remarkable interaction unfolds as GltG binds into a crevice on GltD: the previously non-ordered GltG segment (residues 428–543) undergoes a structural transformation, encircling GltD in a half-turn. Simultaneously, the C-terminal TonB-CTD like domain nestles close to the GltD N-terminal domain (Fig. 4A, B). Consequently, a large surface of GltD is covered by GltG (Table S1B). Contrastingly, the post-TMH domain of GltJ shows a distinct interaction pattern. In this instance, the extensive periplasmic segment remains unordered and no interaction could be assigned. However, the GltJ C-terminal TonB-CTD-like domain also binds to the GltD N-terminal domain but on the side opposite to the GltD TonB-CTD (Fig. 4C, D and Table S1B). GltE binds to the C-terminal domain of GltD and also, to some extent, to GltG (Fig. 4A–D and Table S1B).

GltC also establishes a number of interesting interactions. An interaction is predicted between GltC and GltD. This interaction is confined to contacts between the GltC helix 481-517 and the GltD helix 67-97, with no additional predicted interactions beyond these two helices (Table S1B). As mentioned earlier, the GltF C-terminus (133-147) forms a α-helix that binds into a GltC crevice. This interaction is confirmed in the complex. Remarkably, GltF also bridges GltC with GltD and GltG: a GltF β-strand (94-111) inserts in a crevice formed by the GltG N-terminal β-strand 623-640 and α-helix 544-568, aligning parallel to the GltG β-strand (Fig. 4A, inset and Table S1B). GltF also interacts with GltD on its path between GltC and GltG (Table S1B). The rest of GltF, its N-terminus residues 1–132, is predicted as unstructured and an interaction with GltJ is not structurally predicted.

The inner membrane (IM) complex

The Inner Membrane AglRQS complex is predicted to adopt a structural organization that is similar to the recently described structure of the TolQR system23. In the predicted structure (Figs. 5A, B and S5), AglQ and AglS insert their N-terminal segments into a pentameric channel formed by AglR (Fig. 5C), mirroring the insertion of TolR in a channel formed by a TolQ5 pentamer complex23. A major difference however is that TolR forms a homodimeric insertion in the TolQ channel whereas here this insertion is formed by an AglQS heterodimer. Indeed, a discernible structural similarity is observed between TolR and AglQ or AglS: The root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) between TolR superimposed (PDB ID 5by4) on AglQ and AglS is 2.8 Å and 2.3 Å, respectively, despite a low sequence identity (8.5% and 21.4%, respectively).

A Ribbon view of AglR5, AglQ, AglS and GltG. GltJ is not part of the complex. AglQ and S are deeply nested within the central pentameric channel of AglR. B Surface view, same complex and orientation as in (A). C Slabbed surface view showing the presence of the AglQS N-termini inside the AglR5 channel. D Surface view of the AglR5, AglQ, S and GltG complex. AglR5, AglQ, AglS and GltG have been colored by hydrophobicity (brown color) indicating their contact zone with the IM. The IM has been schematically represented (gray). IM inner membrane.

The interactions within the AglR5QS complex exhibit notable strength, evident in the substantial interaction surfaces (Table S1C). Notably, the AglS N-terminal tail crosses the channel to its cytoplasmic end (Fig. 5C).

Two hybrid experiments indicate an interaction of the TMH of GltG with AglR4. Intrigued by the proximity of the central FHA domain to the TMH of GltG, we ventured to predict the structure of a complex consisting of AglR, AglQ, and AglS, adding the region encompassing the FHA and TMH domains of GltG. There is no evidence for an interaction with GltJ but we also included the putative TMH helix of GltJ as it could potentially interact with the AglQRS complex. The prediction only yielded favorable PAE values with GltG and involved both the TMH domain and its flanking FHA domain (Figs. 5 and S5). The strength of the interaction is validated by the PAE values and a large GltG interaction surface covering three AglR monomers (Table S1). Despite GltJ TMH being positioned near the AglR pentamer in the prediction, the PAE values indicate that GltJ does not interact with the AglR complex.

GltI potentially forms a molecular scaffold in the cytoplasm

Although, several protein interactions have been described on the cytoplasmic side, the structure of this complex is rather ill-defined. It comprises at least four components: GltI, another sizable TPR protein; AglZ, a hypothesized elongated coiled protein featuring a N-terminal phosphor-acceptor receiver (REC) domain, MreB and MglA. We recently published that docking of this complex to the Agl-Glt system occurs via interactions between AglZ and the GltG GYF domain and MglA-GTP and the unfolded linker motif situated between the ZnR and the GYF domains17 (Fig. S2D).

For completing this study, we conducted structure predictions for GltI, AglZ, MreB, and MglA. GltI, a lengthy (~1100 Å) TPR-containing protein, features a substantial helical C-terminal domain (Figs. 6A, B and S6). To elucidate the function of GltI, we conducted structure predictions for GltI, incorporating cytoplasmic domains of the Agl-Glt machinery, both the GltG FHA N-terminal domain and the GltJ GYF domain (Figs. S2E and 6A, B). Our analysis revealed six binding sites for the GltG FHA N-terminal domain on GltI, along with two sites for the GltJ GYF (see Fig. 6A, B). These six binding sites of the GltG FHA domain demonstrate favorable PAE values (Fig. S5 and Table S1D) and exhibit good superimposition with each other (Fig. 6C). The PAE values support for the GltJ GYF binding sites is weaker (Table S1D), and thus these interactions should be considered more cautiously.

A Ribbon view of GltI in complex with GltG N-terminal FHA domain and GltJ GYF domain. Note the presence of six binding sites of GltG FHA on Glti (G1–6) and of two GltJ GYF binding sited (J1, J2). B Surface view, same orientation as in (A). C Close up view of the binding of GltG FHA on GltI. D Superposition of the GltG FHA domains on their GltI binding sites.

A structural view of the motility complex

The four identified modules above must seamlessly integrate to enable gliding. First, by combining the GltABHK-CglB-GltC (OM) complex with the GltCDEFGJ (Periplasmic) complex, along with other intermediate predictions (see “Methods”), we observe the respective orientation of these two modules, suggesting that when it is connected to the OM complex the periplasmic complex runs underneath the OM and parallel to it (Fig. 7).

From bottom to top: the adhesin OM complex, the periplasmic complex, the inner membrane complex followed by the GltI-GltG-FHA and the GltI-GltJ-GYF cytoplasmic complexes. The N-termini of GltG and GltJ are identified (Nt). GltJ N-terminus interacts with other proteins bot shown here. Overall distances are given in Å. IM inner membrane, OM outer membrane.

On the IM side, the periplasmic complex is evidently tethered to the Inner Membrane (IM) complex through GltG. However, the structure of the junction between these two components was not predicted as a singular structure but rather as an elongated, potentially disordered linker. This disordered section of GltG (residues 371–494), is long enough to extend across most of the periplasmic space (Fig. 7, see “Discussion”) and could thus explain how the system transduces forces across the PG layer (see “Discussion”).

Discussion

In this study, we leveraged Alphafold at a very large scale to predict key structural features of a bFA. This work, a true modeling approach, required thousands of in silico experiments and days of calculation. In the process, we tested a very large number of potential associations and stochiometries and only the interactions that were predicted with sufficiently high PAE are reported here. In fact, these PAE scores fall into the range of scores associated with predictions considered to report the actual structure of protein complexes with the highest probability20. Indeed, there are many hints that the predictions reported here are accurate as they correctly capture published experimental works and explain several unusual features reported by the experiments (for example, the surface exposure of CglB, and the presence of the two TolR orthologs, AglS and AglQ, see below). Crucially, the structural predictions reveal the potential path for force transduction across the cell envelope in a bFA, from the cytosolic platform to the cell surface which we discuss below.

The OM complex model provides key explanations to the mechanism of CglB exposure at the cell surface. The model first explains reciprocal dependency of GltA and GltB for OM insertion9,14, which arises from their strong linkage, including the formation of a β-sheet (shown in Fig. 1b, c). GltH is also observed to form surface contacts with GltA and GltB, partially covering their extra barrel elements (and thus explaining partial protection from proteolysis9). although its exact function in the OM complex remains unclear. Since GltH is also observed to interact with GltC it could reinforce this interaction. Alternatively GltH could bridge other proteins unexplored in this study and probably yet to be discovered.

A key contribution of the model is that it reveals how the insertion of GltK into the OM complex provokes exposure of CglB at the cell surface, which had remained mysterious. Indeed, being lipoproteins, both GltK and CglB are expected to be located on the inner side of the OM. But it was shown experimentally that CglB interacts with the OM complex at the cell surface9. The model predicts this topology correctly and shows that such positioning is promoted by strong interactions, on one side with GltK, covering an important surface on the external face of the GltA-B complex; and on the other side with the GltA-B complex itself.

Perhaps, the most important contribution of the model is the prediction of the composition and structure of the periplasmic complex connecting both the IM motor OM and the OM complex. There are a number of remarkable features: (1) At the base of the OM complex, GltC acts as a scaffold engaging strong interactions with extended periplasmic segments of GltA and GltB, which become remarkably organized making anti-parallel β-strands (Fig. 3). This explains why GltC cannot be stably expressed in the absence of GltA and GltB9,14. These interactions are fully compatible with the interactions that GltC makes with the periplasmic complex, supporting a central role for GltC as a connector in the force transduction pathway. Hence, GltC serves as the crucial contact domain bridging the outer membrane (OM) complex to the periplasmic complex. While the interaction between GltC and GltD only involves a relatively small contact surface formed by two helices from each component, it is strengthened and perhaps modulated by a third partner, GltF. GltF acts as bridge, inserting a helix in GltC on one side, and making a strong contact with the GltG TonB-CTD domain, itself bound to GltD, on the other side. (2) GltD connects OM, IM and cytosolic components. GltD connects with GltG and J, both IM proteins and GltC at the OM. The interaction between GltG and GltD is strongly stabilized by a long GltG domain that runs into a GltD crevice spanning ~two-thirds of the protein. This conformation is strictly conserved among all our structural predictions involving different partners. Interestingly, the interaction of the GltG TonB-CTD with GltD is predicted at two distinct close positions. This suggests that this contact might be modulated, perhaps via motor activity. The GltG transmembrane helix and GltD are linked by a long unstructured GltG stretch of ~124 amino-acids. This protein segment is sufficiently long to cross the peptidoglycan layer and thus transduce motor activity to the other side, at the OM. The function of the GltJ TonB-CTD is less clear, it interacts at the same position with GltD in all predictions. However, the rest of the GltJ chain is predicted as unstructured, and no other interactions could be predicted in the periplasm. Interestingly, since GlJ is a critical contact point with the cytosolic platform, it bridges it directly to the OM via GltD. GltD also interacts with GltE but the function of this interaction is also unclear.

When we analyzed the IM motor complex, we only obtained a robust prediction for a stoichiometry corresponding to an AglR5QS-GltG complex. Remarkably, this complex is very similar to the TolQ5R2-TolA complex: R5 and Q5 form the trans-IM pore, while QS and R2 form the plug, respecively23. GltG may be compared to TolA, as they both possess a trans-membrane helix (TMH) associated to the pore complex and a long periplasmic extension (EF). GltG, however, possess a FHA domain before the TMH, strongly attached to the cytoplasmic part of the pore. In the TolQ5R2-TolA complex, it is believed that the activation of the proton pump initiates the disengagement of TolR2 from the lumen of TolQ5 channel. This event is followed by the recruitment of TolA via TMH binding, inducing a structural alteration in the EF region, and facilitating the passage of the TolA C-terminus through the peptidoglycan layer to ultimately engage with the TolB-Pal complex13,23,24. Hence, TolA oscillates between two states, unbound to the pore at rest with R2 plugging the pore, and bound when the system is activated, with R2 unplugged and TolA bound to TolB. To note, a transient state was suggested in which TolA is bound to the pore, but with R2 still plugged and TolA not extended24. Our predicted model of the IM complex is thus comparable to the transient state proposed in the TolQ5R2-TolA system.

In another similar system, the ExbBD-TonB system, the channel formed by ExbB is also closed by an ExbD dimer plug in the resting state25. In the open state, the periplasmic domain of ExbD adopts an extended conformation which interacts with PG, opening the channel which becomes active25. Similarly, TolR dimers organize a periplasmic domain that plugs the TolQ5 channel and it is also suggested that TolR binds to PG when the system becomes active26. Considering this, we contemplated whether a similar mechanism might apply to AglRQS. AglQ and AglS also associate a periplasmic plug domain, rich in charged residues featuring numerous Glu/Asp residues and Lys/Arg residues. Intriguingly, AglQ possesses a long linker, whereas AglS does not. Furthermore, AglS is more deeply inserted into the AglR5 channel, suggesting that it can only be unplugged once AglQ is lifted. Therefore, it is plausible that a mechanism akin to the one proposed for ExbD/TolR/PG binding also operates here, such that unfolding of the AglQ linker opens the AglR5 channel, clipping the system to PG when forces are generated.

Contrarily to the other bFA modules, our analysis failed to predict the structure of the cytoplasmic platform. This is perhaps because the cytosolic platform may rely on higher order interactions, for example regrouping several Agl-Glt complexes within a single bFA. Indeed, we find that the extensive cytosolic protein GltI encompasses multiple sites capable of binding to the GltG N-terminal FHA domain. Additionally, there is a likelihood that the GltJ GYF domain interacts with two potential sites on GltI. Despite efforts, interactions of GltI with other components such as AlgZ or MglA were not discernible. Nonetheless, drawing from prior findings, it is conceivable that the GltJ GYF domain serves as a bridge between GltI and AlgZ. The abundance of GltG-binding sites within GltI thus suggests a propensity for this protein to spatially organize several motor complexes. A cytosolic platform containing MreB, MglA and AglZ might further organize such clustering within active bFAs.

The new structural view of the motility complex underscores key contact points, and reveals that GltD and GltC act as major connectors in the system. Remarkably, docking of the OM and periplasmic proteins orients the periplasmic complex parallel to the OM, conspicuously positioned as a potential mechanical shaft. Based on their similarity with the flagellar motor, the Tol/Exb/Agl systems are also expected to function as rotary motors23. This suggests that the Agl motor could rotate the OM complex via the periplasmic shaft, bringing the OM complex in register for force transduction (Fig. 8). If the OM complex were organized along a track (which is suggested by the rotation of the cell), repetition of this mechanical cycle would propel the cell directionally, flowing OM complexes one by one into bFAs (Fig. 8).

For simplicity, the motility complex is represented as three functional modules: an adhesive outer membrane (OM) complex (shown in orange) bound to a putative track (represented by a dotted black line), a fixed motor complex (bound to PG when active) that includes the inner membrane (IM) force-generating unit and a periplasmic shaft (in yellow), and a cytosolic platform (in light yellow). Proton flow through the motor is proposed to rotate a flexible periplasmic extension of the GltG protein, which connects to a shaft formed by the GltD complex. This rotation would move the OM complex in coordination with the motor, allowing force transduction to the substrate. The cycle then repeats, with the OM complex capturing the next adhesin associated with the track, thus moving the cell in a screw-like motion. IM inner membrane, OM outer membrane.

One significant constraint of the current model is that it depicts a singular configuration of the gliding machinery, which is constructed from predicted complexes that may exist in distinct dynamic states. For example as discussed above, the structure of the inner membrane (IM) complex does not to capture opening of the AglR5QS channel, removal of the plug, and interactions with the peptidoglycan. Similarly, binding of the GltG C-terminus to GltD must correspond to an active state, comparable to the binding of TolA to TolB in the TolQR-TolA system. Both GltG and GltJ must also break their interactions in order for the motor to move directionally along the cell axis. In addition, the model does not account for potential multimerization and other layers of complexity are likely at work. This is certainly suggested by the presence of GltI and its multiple GltG-binding sites, suggesting the possibility that multiple Agl-Glt machinery could be scaffolded by a single GltI protein in a bFA.

Despite its limitations, it is important to consider that this structural model is built on a wealth of experimental evidence, and accordingly, it is supported by good pLDDT and PAE values. Such modeling is arguably an immense leap forward as it would have taken years of structural explorations to possibly obtain the structure of the predicted complexes experimentally. It is now structurally evident how the motor physically contacts the OM complex which has been long controversial27. The next challenge will be to elucidate the mechanism underlying directionality of the motor. The reason is not currently apparent from the model, there is evidence that it is linked to connection between the motor and the cytoplasmic platform8,10 as well the supramolecular organization of the OM complexes (which could create the missing track)3,9. Therefore, we will need a higher order structural understanding of an active bFA, which as mentioned above likely corresponds to a supramolecular aggregate of Agl-Glt systems acting in coordination. The objective is ambitious, yet potentially more attainable than one might think, considering the computational revolution unfolding before us.

In conclusion, the comparison between the Agl system and the Tol system reveals that these evolutionarily related motors both consume energy to dynamically link proteins across the peptidoglycan layer from the inner membrane (IM) to the outer membrane (OM). In both cases, the IM motor is tethered—at the bacterial septum for TolQR and at the cytoplasmic platform for AglRQS—acting as a stator to align OM proteins and locally concentrate them at the motor site. For the Tol-Pal system, this enables the final step of cytokinesis, while for AglRQS, it results in localized adhesion and propulsion. Furthermore, beyond these specific systems, we foresee that this reverse-modeling approach could be broadly applied to predict complex structure-function relationships in large molecular machines across various cell types. As with other modeling approaches in biology, this method is not intended to replace experimental determination of complex structures, but rather to prioritize critical complexes for in-depth study. Such an approach could significantly accelerate our understanding of molecular processes at the deepest levels.

Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT), a per-residue measure of local confidence, and of Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) values.

Methods

For conducting AlphaFold2 version 2.3.120 structure predictions of protein monomers and multimers, we utilized access to the Institut du développement et des ressources en informatique scientifique (IDRIS) Jean-Zay multi-GPU server equipped with Nvidia A100 GPUs and 80 GB RAM. The AlphaFold Predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) and Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) output are provided in the supplementary material (Figs. S1, S2–S6). pLDDT is a per-residue measure of local confidence scaled from 1 to 100 and PAE is a measure of how confident AlphaFold2 is in the relative position of two residues within the predicted structure. The pLDDT values of the predicted structures and PAE were visualized using AlphaPickle on the IDRIS server. Additionally, pLDDT values were stored in the PDB files as B-factors. Concerning the reliability of the data, we only present predictions with pLDDT values higher to 70% or 80%, which—according to Jumper et al.20—should be comparable to X-ray medium resolution structures (2.0 to 3.0 Å). We always took into consideration the PAE which indicate the validity of the interactions predicted. All predictions that did not satisfy the pLDDT and PAE criteria were discarded.

Visual inspection and analysis of the structures were carried out using either Coot28 or ChimeraX29. Final predicted protein or domain structures were subjected to analysis on the Dali30 or FoldSeek22 servers to identify the closest structural homologs in the PDB. Visual representations of these structures were generated using ChimeraX29. Buried Surface Areas (BSA) within the complexes were calculated utilizing the PISA server31.

The prediction of the GltA/GltB/GltH/GltK/GltC/CglB complex was performed as a whole, but we also predicted several sub-complexes to assess the coherence and robustness of the predictions. Due to technical constraints, complexes involving GltD were predicted in two overlapping halves, namely GltDnt/GltC/GltFct/GltGct/GltJct and GltDct/GltGmedium/GltE, which were subsequently reassembled using Coot28. The prediction of the AglR5QS/GltG/GltJ complex was conducted as a whole. Similarly, the GltI/GltG(FHA)/GltJ(GYF) complex was predicted in seven overlapping segments, each including a GltG(FHA) and a GltJ(GYF). The entire structure was then reassembled using Coot28. For disordered segments, we use a strategy described by Bret et al.32 by delineating the interaction region into fragments of decreasing size. To note, the predictions were not followed by molecular mechanics relaxation (an Alphafold option) as structural details of side-chain interactions and precise loops conformation were not the scope of this topological study (for discussions by Terwiliger et al. on this issue see ref. 33). Coordinates files have been deposited at Zenodo.org under ref. 34.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Coordinates files have been deposited at Zenodo.org under ref. 34. All other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Legerstee, K. & Houtsmuller, A. B. A layered view on focal adhesions. Biology 10, 1189 (2021).

Mignot, T., Shaevitz, J. W., Hartzell, P. L. & Zusman, D. R. Evidence that focal adhesion complexes power bacterial gliding motility. Science 315, 853–856 (2007).

Faure, L. M. et al. The mechanism of force transmission at bacterial focal adhesion complexes. Nature 539, 530–535 (2016).

Luciano, J. et al. Emergence and modular evolution of a novel motility machinery in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002268 (2011).

Nan, B., Mauriello, E. M. F., Sun, I.-H., Wong, A. & Zusman, D. R. A multi-protein complex from Myxococcus xanthus required for bacterial gliding motility. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1539–1554 (2010).

Sun, M., Wartel, M., Cascales, E., Shaevitz, J. W. & Mignot, T. Motor-driven intracellular transport powers bacterial gliding motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 7559–7564 (2011).

Nan, B. et al. Myxobacteria gliding motility requires cytoskeleton rotation powered by proton motive force. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2498–2503 (2011).

Nan, B. et al. Flagella stator homologs function as motors for myxobacterial gliding motility by moving in helical trajectories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E1508–E1513 (2013).

Islam, S. T. et al. Unmasking of the von Willebrand A-domain surface adhesin CglB at bacterial focal adhesions mediates myxobacterial gliding motility. Sci. Adv. 9, eabq0619 (2023).

Nan, B. et al. The polarity of myxobacterial gliding is regulated by direct interactions between the gliding motors and the Ras homolog MglA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, E186–E193 (2015).

Treuner-Lange, A. et al. The small G-protein MglA connects to the MreB actin cytoskeleton at bacterial focal adhesions. J. Cell Biol. 210, 243–256 (2015).

Seef, S. et al. A Tad-like apparatus is required for contact-dependent prey killing in predatory social bacteria. Elife 10, e72409 (2021).

Webby, M. N., Williams-Jones, D. P., Press, C. & Kleanthous, C. Force-generation by the trans-envelope Tol-Pal system. Front. Microbiol. 13, 852176 (2022).

Jakobczak, B., Keilberg, D., Wuichet, K. & Søgaard-Andersen, L. Contact- and protein transfer-dependent stimulation of assembly of the gliding motility machinery in Myxococcus xanthus. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005341 (2015).

Mauriello, E. M. F. et al. Bacterial motility complexes require the actin-like protein, MreB and the Ras homologue, MglA. EMBO J. 29, 315–326 (2010).

Fu, G. et al. MotAB-like machinery drives the movement of MreB filaments during bacterial gliding motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2484–2489 (2018).

Attia, B. et al. A molecular switch controls assembly of bacterial focal adhesions. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn2789 (2024).

Attia, B. et al. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift assignments of the ZnR and GYF cytoplasmic domains of the GltJ protein from Myxococcus xanthus. Biomol. NMR Assign. 16, 219–223 (2022).

Szadkowski, D. et al. Spatial control of the GTPase MglA by localized RomR-RomX GEF and MglB GAP activities enables Myxococcus xanthus motility. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1344–1355 (2019).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Fukuda, A. et al. Aminoacylation of the N-terminal cysteine is essential for Lol-dependent release of lipoproteins from membranes but does not depend on lipoprotein sorting signals. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43512–43518 (2002).

van Kempen, M. et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 243–246 (2024).

Williams-Jones, D. P. et al. Tunable force transduction through the Escherichia coli cell envelope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2306707120 (2023).

Szczepaniak, J. et al. The lipoprotein Pal stabilises the bacterial outer membrane during constriction by a mobilisation-and-capture mechanism. Nat. Commun. 11, 1305 (2020).

Zinke, M. et al. Ton motor conformational switch and peptidoglycan role in bacterial nutrient uptake. Nat. Commun. 15, 331 (2024).

Boags, A. T., Samsudin, F. & Khalid, S. Binding from both sides: TolR and full-length OmpA bind and maintain the local structure of the E. coli cell wall. Structure 27, 713–724.e2 (2019).

Nan, B. & Zusman, D. R. Novel mechanisms power bacterial gliding motility. Mol. Microbiol. 101, 186–193 (2016).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Meng, E. C. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 32, e4792 (2023).

Holm, L., Laiho, A., Törönen, P. & Salgado, M. DALI shines a light on remote homologs: one hundred discoveries. Protein Sci. 32, e4519 (2023).

Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007).

Bret, H., Gao, J., Zea, D. J., Andreani, J. & Guerois, R. From interaction networks to interfaces, scanning intrinsically disordered regions using AlphaFold2. Nat. Commun. 15, 597 (2024).

Terwilliger, T. C. et al. AlphaFold predictions are valuable hypotheses and accelerate but do not replace experimental structure determination. Nat. Methods 21, 110–116 (2024).

Cambillau, C. & Mignot, T. Structural model of a bacterial focal adhesion complex from Myxococcus xanthus. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13923821 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by ERC JAWS 885145. This work was performed using HPC resources from GENCI-IDRIS (Grant 2023-AD010714075). We acknowledge UCSF ChimeraX for molecular graphics that is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from National Institutes of Health R01-GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. led the study. C.C. performed the AlphaFold2 predictions and analysis. The initial manuscript was written by C.C. and T.M. C.C. and T.M. have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Xiaohui Zhang and Laura Rodríguez Pérez.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cambillau, C., Mignot, T. Structural model of a bacterial focal adhesion complex. Commun Biol 8, 119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07550-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07550-w