Abstract

Dynamic transitions between competition and cooperation are common in real-world intergroup interactions, yet prior research has typically examined competition or cooperation in isolation. This study explored how transitions between competition and cooperation influenced intergroup attitudes and the neural processes involved. Using functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) hyperscanning, we recorded brain activity from 69 dyads during interactions. Results showed that cooperation enhanced neural synchronization in the right temporoparietal junction (rTPJ), leading to more positive outgroup attitudes. In contrast, competition increased synchronization in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (rDLPFC), correlating with decreased outgroup likability. The sequence of interactions was critical, with the first interaction exerting a carryover effect on the next. Cooperation buffered the negative effects of later competition, while competition weakened the positive effects of subsequent cooperation. These findings emphasized the importance of understanding dynamic intergroup interactions and highlighted the potential of cooperation to mitigate biases and improve intergroup relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of intergroup relationships is increasingly important in today’s interconnected world. Intergroup interactions, encompassing both competition and cooperation, play a fundamental role in shaping intergroup attitudes and behaviors. Competition often exacerbates intergroup bias, fostering hostility and prejudice1,2,3, while cooperation fosters trust and mutual understanding, promoting positive intergroup relations4,5,6. Neural synchronization reflects the alignment of brain activity during interactions, facilitating coordinated behavior and serving as a crucial indicator of interpersonal coordination7,8,9. Research has shown that neural synchronization is stronger during cooperative activities compared to competitive ones10 and is also more pronounced in ingroup interactions than in intergroup interactions11. Enhanced synchronization in cooperation is associated with improved mutual understanding and joint decision-making8,12,13, which are critical for promoting positive intergroup evaluations14. Thus, stronger neural synchronization during cooperation may serve as a neural mechanism underlying improved intergroup attitudes.

In many real-world situations, intergroup interactions are not static but shift between competition and cooperation depending on context and goals. For example, while countries may compete economically or politically, they often transition to collaboration when addressing global challenges such as climate change or public health. Historically, rival nations have evolved from adversaries to allies, especially in an era that increasingly emphasizes cooperation for mutual benefit. Despite extensive research on intergroup interactions, much of the focus has been on competition or cooperation in isolation. The effects of transitions between these states—and the order in which they occur—on intergroup attitudes remain largely unexplored.

Dynamic interaction sequences might elicit carryover effects, where initial interactions establish neural and behavioral baselines that influence subsequent encounters. The secondary transfer effect suggests that contact with an outgroup can impact attitudes towards another secondary outgroup15. Similarly, the emotional carryover effect posits that emotional and neural states from one interaction persist, shaping responses to subsequent interactions16,17. Together, these frameworks highlight how initial interactions may set the stage for subsequent dynamics, suggesting that the sequence of competition and cooperation with the same outgroup could leave lasting impacts on intergroup attitudes and neural mechanisms. In this study, we aimed to explore how these transitions affect intergroup attitudes and the underlying neural mechanisms, which are key to understanding intergroup dynamics.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) hyperscanning enables the simultaneous recording of brain activity from multiple individuals, providing valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying real-time social interactions18. Previous studies have identified the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporoparietal junction (TPJ) as key regions involved in social decision-making and interaction13,19,20,21,22. Specifically, the PFC is associated with cognitive control and strategic decision-making23,24, while the TPJ is linked to perspective-taking and social understanding25,26,27. These functions are integral to both cooperative and competitive interactions, making the PFC and TPJ particularly relevant for studying the neural dynamics of intergroup interactions28. Additionally, it has been suggested that the functional connectivity between the rDLPFC and rTPJ plays a critical role in coordinating social behaviors29. By analyzing synchronization patterns in these regions, we aimed to uncover the neural mechanisms during intergroup interactions and how transitions between these interactions influence neural processes and intergroup attitudes.

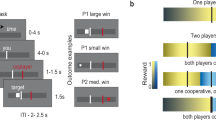

In this study, pairs of participants engaged in both competitive and cooperative tasks. Each pair was randomly assigned to opposing teams, with one participant on the Red Group and the other on the Blue Group, and wore armbands corresponding to their team color to signify group affiliation (Fig. 1b). Thirty-four dyads completed interactions in a competition-to-cooperation sequence, while thirty-five completed them in the opposite order. Each interaction type—competition and cooperation—comprised 12 rounds, simulating real-world scenarios where competing for resources or collaborating to achieve shared objectives. The competitive task was adapted from the intergroup Point Subtraction Aggression Paradigm (IPSAP), and the cooperative task from the intergroup Public Good Game (IPGG)30. After every three rounds, participants rated their liking of two teams, as a measure of intergroup attitudes (see Methods for details). We applied fNIRS hypercanning to record the brain activity of both participants during the interactions (Fig. 1a and Methods).

a Timeline for an experimental session. Before coming to the laboratory, participants completed an online survey that included a personality questionnaire and demographic information. b Participants’ experimental arrangement. Two same-gender participants sat opposite each other with screens blocking their direct view. They wore armbands to indicate group membership and individual neural activity was recorded using fNIRS during the intergroup interaction. c Timeline of a single round. Each round consisted of four phases: an 8-s inter-round interval, a 20-s decision-making phase, an 8-s waiting phase, and a 10-s outcome phase, totaling 46 s per round.

We hypothesized that the relationship between neural processes and intergroup attitudes would differ between cooperation and competition. Specifically, based on findings that cooperation enhances neural synchronization and improves intergroup relations, we expected stronger neural synchronization during cooperation to correlate with more positive intergroup attitudes, compared to competition. Additionally, building on the secondary transfer effect and emotional carryover effect, we hypothesized that the sequence of interactions could modulate these patterns. For example, when cooperation precedes competition, the positive effect of cooperation on intergroup attitudes might weaken the negative effect of subsequent competition. Conversely, if cooperation follows competition, the positive effect of neural synchrony during cooperation on intergroup attitudes might not manifest. In other words, when transitioning from one type of interaction to another, the impact of previous interactions might persist and affect the subsequent one. Understanding these dynamics could provide new insights into human social behavior and inform strategies for resolving intergroup conflicts.

Results

Behavioral indicators of intergroup attitudes

Initial likability ratings were measured before the interactions began, showing that participants rated ingroup likability significantly higher compared to outgroup likability at baseline, indicating an initial bias favoring the ingroup (see Supplementary Table 1a, b for full details). As expected, participants consistently rated ingroup likability higher than outgroup likability throughout the interactions (the main effect of Target: F1,136 = 161.469, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.543). Moreover, outgroup likability ratings were significantly higher during cooperative interactions compared to competitive interactions (the interaction effect of Type × Target: F1,136 = 54.405, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.278; Fig. 2; see Supplementary Table 1 for the full statistical analysis of likability ratings). We further investigated whether the outcomes of the interactions influenced outgroup likability. The results indicated that the number of wins before each rating during competition positively correlated with outgroup likability (b = 0.499, t = 4.609, p < 0.001), as did the rewards received during cooperation (b = 0.038, t = 11.571, p < 0.001). However, the order of interactions did not significantly affect the relationship between interaction type and outgroup likability.

a Likeability ratings of ingroup and outgroup across rounds of competition and cooperation. The left panel shows the competition-to-cooperation sequence, and the right panel shows the cooperation-to-competition sequence. Each dot represents an individual rating, with blue dots indicating ingroup ratings and red dots indicating outgroup ratings. The blue solid lines represent the average ingroup ratings, while the red solid lines represent the average outgroup ratings, with shaded areas showing the 95% confidence intervals (CI). b Relationship between the number of wins before each rating and outgroup likability during competition. The orange line shows the linear trend, with the shaded area representing the 95% CI. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is reported as r = 0.193, with p < 0.001. The gray squares inside the boxplots represent the mean values. The boxes indicate 25th and 75th quartiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the hinge, with horizontal lines inside the boxes indicating median values. c Relationship between average payoff during cooperation and outgroup likability. Each point represents an individual’s data, with the green line showing the linear trend and the shaded area representing the 95% CI. Pearson’s correlation coefficient is reported as r = 0.442, with p < 0.001.

Neural synchronization (NS)

NS in our two regions of interest (the rPFC and rTPJ) was measured using wavelet transform coherence. We used 19 channels for examining NS: eleven channels (channels 1–11) for the rPFC and eight channels (channels 12–19) for the rTPJ. To account for multiple comparisons, we applied a 19-channel false discovery rate (FDR) correction.

First, we analyzed the effects of interaction type and interaction order on NS. The results indicated that neither the main effect of order nor its interaction effects were significant. We then focused on the differences in NS across different channels based on interaction type, disregarding interaction order. During the decision-making phase of the competition, NS in the rPFC (channels 1–5, 9–11) was higher than during the cooperation phase. Conversely, during the decision-making phase of cooperation, NS in the rTPJ (channels 13, 16–17) was higher than during the competition phase (these channels survived a 19-channel-wise FDR correction, Supplementary Table 2a).

Next, we compared NS during the decision-making phase with NS during the result-waiting phase to determine whether NS was enhanced or reduced during decision-making. The result-waiting phase was chosen as a baseline because it reflects a task-related but cognitively neutral state, providing a more contextually relevant comparison than resting-state data29. This approach allows us to directly capture neural synchronization changes induced by interaction tasks, minimizing variability unrelated to task engagement. A repeated measures ANOVA with factors of interaction type (competition versus cooperation) × phase (decision-making versus result-waiting) was conducted on eleven channels survived FDR correction. The post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that compared to the waiting phase, NS in rDLPFC (channel 9 and 11) increased during the competitive decision-making phase and NS in rTPJ (channel 13) increased during the cooperative decision-making phase (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 2b).

These channels were selected because they passed the validation analyses. Channel 9 did not pass the validation analyses and was therefore excluded. Each boxplot shows NS during decision-making (green) and results-waiting (orange) phases for competition and cooperation tasks. The gray squares within the boxplots represent the mean values. The boxes indicate 25th and 75th quartiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the hinge, with horizontal lines inside the boxes indicating median values.

To ensure that NS was not merely influenced by participants being in the same environment and performing the same tasks, several validation analyses were conducted. First, 69 within-condition pseudo dyads were generated by randomly pairing two individuals from different original dyads within the same condition (i.e., two conditions of interaction order; 35 pseudo dyads from cooperation to competition, and 34 pseudo dyads from competition to cooperation). The NS of each pseudo dyad was computed using the same method as that applied to the real dyads. To determine whether the interaction type × phase effects on NS were specific to real interacting dyads, a three-way ANOVA on NS was conducted with interaction type (competition versus cooperation), phase (decision-making versus result-waiting), and Dyad (real versus pseudo) as factors. This analysis focused on three channels (9, 11, and 13), which exhibited significant interactions in real dyads. We found significant type × phase interactions on NS in rDLPFC (channel 11) and rTPJ (channel 13) for real dyads but not for pseudo dyads, suggesting the observed type × phase interaction effects were stronger in real interacting dyads compared to randomly paired individuals under the same condition (Supplementary Table 2c).

Second, nonparametric permutation tests31,32 were conducted, generating 1000 permutation samples (each sample contained 69 pseudo dyads) to compare with the observed type × phase interaction effects on NS in the real dyads. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the permutation distribution of the 1000 pseudo-dyad samples was [0.0206, 0.0215] for channel 11 and [−0.0066, −0.0057] for channel 13. In contrast, the type × phase interaction observed in the real group was 0.0266 for channel 11 and −0.0142 for channel 13, both outside the 95% CI of the permutation distribution.

Finally, we investigated whether NS in real groups was merely a reflection of decision similarity between individuals in dyads. If this were the case, we would expect stronger NS when individuals within a dyad made more similar decisions. For cooperative decisions, we calculated the absolute difference between the contribution decisions of the two individuals in each dyad. For competitive decisions, we calculated the absolute difference in the proportion of three actions between the two individuals in each dyad (i.e., for each round: (|xa – ya| + |xb − yb| + |xc – yc|) for competition and (|x − y | ) for cooperation). Using a median split, we categorized all the rounds into ‘similar’ and ‘dissimilar’ decisions and calculated the effect of decision similarity on NS during both the cooperative and competitive decision-making phases. Regardless of the interaction type—cooperation or competition—the effect of decision similarity on NS during the decision-making phase was not significant (Supplementary Table 2d, e).

These validation results suggested that the observed interaction effects on NS in the rPFC and rTPJ in real dyads were unlikely to be solely due to similar decisions or exposure to the same experimental environment and tasks. Therefore, we proceeded to examine the relationship between NS and intergroup attitude during competition and cooperation. Given that outgroup likability was the only behavioral measure influenced by interaction type, and that both members of each dyad rated outgroup liking, we used the average outgroup likability score of both participants in the dyad as the dependent variable. The coherence values for channels 11 (rDLPFC) and 13 (rTPJ) were averaged across every three rounds to serve as the independent variables. Linear regressions were performed separately for each channel and each interaction order.

The results showed that when competition preceded cooperation, NS in the rDLPFC (channel 11) during the competitive decision-making phase negatively predicted outgroup likability (b = −8.442, SE = 2.744, t = −3.077, p < 0.01), while NS during the cooperative decision-making did not significantly relate to outgroup likability. Conversely, when cooperation preceded competition, NS in the rTPJ (channel 13) during the cooperative decision-making positively predicted outgroup likability (b = 8.488, SE = 3.699, t = 2.295, p < 0.05), with no significant relationship observed during the competitive phase (Fig.4 and Supplementary Table 3). These findings confirmed that NS in different interactions had distinct effects on intergroup attitudes, with NS during cooperation enhancing outgroup likability and NS during competition reducing it. Moreover, it revealed that the order of interactions modulated the relationship between NS and outgroup likability.

a NS in the rDLPFC during competition as the first interaction (competition-to-cooperation condition) negatively correlates with outgroup likability (Pearson’s r = −0.257, p = 0.003, n = 34 dyads). b NS in the rTPJ during cooperation as the second interaction (competition-to-cooperation condition) does not significantly correlate with outgroup likability. c NS in the during cooperation as the first interaction (cooperation-to-competition condition) positively correlates with outgroup likability (Pearson’s r = 0.192, p = 0.023, n = 35 dyads). d NS in the rDLPFC during competition as the second interaction (cooperation-to-competition condition) does not significantly correlate with outgroup likability. Correlations were performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Each circle represents the averaged outgroup likability within a dyad (y-axis) and NS in the rDLPFC or rTPJ (x-axis). The solid line indicates the least squares fit, with shading showing the 95% confidence interval.

Neural activity of single brain

To further understand the relationship between neural processes and outgroup likability, we analyzed individual brain activity by assessing changes in oxy-Hb concentration. Linear regression analyses were performed separately for each channel, each interaction type, and each interaction order, with outgroup likability as the dependent variable and the average neural activities during the three rounds before ratings as the independent variable.

The results indicated that in the competition-to-cooperation sequence, rTPJ activity during competition negatively predicted outgroup likability. However, neural activities during the cooperation did not significantly predict outgroup likability. In the cooperation-to-competition sequence, rTPJ activity during cooperation positively predicted outgroup likability. In contrast, rTPJ activity during the subsequent competition no longer significantly predicted outgroup likability, while rDLPFC activity during competition negatively predicted outgroup likability (Supplementary Table 4).

Finally, we explored functional connectivity between the rPFC and the rTPJ to further illustrate the differences in neural processes underlying competitive and cooperative interactions. Wavelet coherence analyses between the rPFC and the rTPJ were conducted for each individual, and the coherence values indexed the rPFC-rTPJ functional connectivity. The analyses showed that cooperation, compared to competition, increased functional connectivity between these regions, regardless of interaction order (the main effect of interaction type: F1,136 = 41.741, p <0.001, η2p = 0.235) (Fig. 5 for the grand mean rPFC–rTPJ connectivity; 67 rPFC–rTPJ channel pairs survived FDR correction for 88 rPFC–rTPJ channel pairs, Supplementary Table 5).

The gray squares represent the mean FC values. The gray squares inside the boxplots represent the mean values. The boxes indicate 25th and 75th quartiles, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the hinge, with horizontal lines inside the boxes indicating median values.

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that competition and cooperation have distinct effects on intergroup attitudes, with competition often exacerbating biases and cooperation mitigating them6,33,34. Consistent with prior findings, our results indicate that outgroup likability is lower during competition compared to cooperation. Our findings also reveal differences in the underlying cognitive processes of cooperation and competition, as reflected in neural synchronization and functional connectivity. Specifically, neural synchronization in the rDLPFC was more pronounced during competition, while rTPJ synchronization was stronger during cooperation. Additionally, functional connectivity between the rPFC and rTPJ was generally stronger during cooperation than during competition.

Moreover, our study sheds light on the effects of neural mechanisms on intergroup attitudes. During competition, both neural synchronization and neural activities in rDLPFC negatively predicted outgroup likability, while during cooperation, both in rTPJ positively predicted it. This suggests that competition and cooperation engage different neural processes that either exacerbate or alleviate intergroup biases. Furthermore, by examining the dynamic transitions between competition and cooperation, we found that the effects of neural processes on intergroup attitude were most pronounced during the first interaction, with these effects diminishing in the second. This indicates a carryover effect, where the initial interaction influences subsequent ones.

Our results demonstrate that different brain regions play distinct roles in shaping the effect of interactions on intergroup attitudes. The DLPFC is involved in conflict monitoring and strategic decision-making, which is crucial during competition35,36. Increased synchronization and activation of the rDLPFC during competition may reflect a focus on differences and conflicts, reinforcing competitive and antagonistic mindsets that reduce outgroup likability. Conversely, neural synchronization and activity in TPJ during cooperation, which is linked to considering others’ perspectives25, achieving consensus37, and fostering emotional alignment38 likely facilitate mutual understanding and acceptance, thus enhancing outgroup likability. These findings align with previous research that cooperative interactions reduce intergroup bias, while competitive interactions undermine prosocial conduct39. More importantly, we extend this line of research by exploring the dynamic effects of sequential interactions on intergroup attitudes and their underlying neural correlates.

Additionally, we found that cooperation increased functional connectivity between the rPFC and rTPJ. The collaborative roles of TPJ and DLPFC have been proved in flexible social behaviors, such as moral and economic21. In more cohesive groups, stronger rPFC-rTPJ connectivity has also been observed, suggesting that increased connectivity between rPFC and rTPJ during cooperation promotes a unified group mindset, enabling better alignment of intentions and actions29,40. Such rPFC-rTPJ connectivity facilitates the integration of social information into the process of making collective decisions29, supporting coordinated collective decision-making37 and positive intergroup attitudes. These findings demonstrate that the effects of interaction type on intergroup attitudes and neural mechanisms are robust across different interaction sequences. This indicates that the neural mechanisms underlying these interaction types are relatively stable and not significantly influenced by the sequence in which they occur. While interaction order did not significantly influence these results, it is possible that its effects are more subtle and may require larger sample sizes or more sensitive paradigms to detect.

Moreover, by adopting a dynamic perspective that considers the transitions between different types of intergroup interactions, our study reveals that the order in which competition and cooperation occur significantly influences the relationship between neural processes and intergroup attitudes. Neural synchronization and rTPJ activity predicted outgroup likability only during the initial interaction, with these effects diminishing if other interactions have occurred previously. This carryover effect suggests that the initial neural patterns established during the initial interaction exert a lasting influence that continues to affect the effect of neural patterns on outgroup attitudes in subsequent interactions. Specifically, in the competition-to-cooperation sequence, the negative impact of neural synchronization and rTPJ activity on outgroup likability during competition carried over into the subsequent cooperative interaction, diminishing the positive effects that these neural processes typically have during cooperation. Similarly, when cooperation occurred first, the positive effects of neural synchronization during cooperation buffered against the negative effects of later competition, though this buffering effect may be incomplete, as indicated by the negative impact of rDLPFC activity during the competition. This phenomenon is consistent with research showing that initial positive contact with an outgroup can lead to a secondary transfer effect, where positive attitudes extend beyond the immediate interaction to influence perceptions of other outgroups41,42. These findings highlight how the neural patterns formed during initial interactions set a precedent for future encounters, emphasizing the importance of initial neural synchronization and rTPJ activity in establishing a framework for understanding and relating to outgroups.

Interestingly, although neural synchronization did not significantly predict outgroup attitudes during the second interaction, behavioral changes in outgroup attitudes were still observed. Given that the strength of neural synchronization was not affected by the order of interactions, as indicated by our results, it is plausible to assume that changes in outgroup attitudes during the second interaction may be driven more by individual neural activity or other unmeasured factors. The absence of a significant neural synchronization effect in the second interaction does not diminish its importance but rather indicates that the mechanisms influencing attitude changes may shift as interactions progress. For example, when competition occurs after cooperation, although rDLPFC synchronization no longer predicts outgroup attitudes, rDLPFC neural activity still negatively predicts them. This result may indicate that different cognitive mechanisms operate at different stages of interaction to influence intergroup attitudes. Neural synchronization likely reflects shared attention and resonance between members, while individual brain activity is more related to conflict monitoring and decision control at the individual level. These processes represent distinct psychological mechanisms that may impact intergroup attitudes differently, depending on the stage of interaction.

By examining the real-time social encounters in a truly interactive manner43,44, our study provides critical insights into the neural mechanisms underlying intergroup interactions and demonstrates that the sequence of competition and cooperation significantly shapes intergroup attitudes. The carryover effect highlights the potential benefits of prioritizing cooperation to activate neural pathways that foster positive intergroup attitudes and buffer against the negative effects of subsequent competition.

From a practical perspective, educational institutions and workplace training programs could integrate this sequence into multicultural education or interdepartmental collaboration to improve mutual understanding and acceptance among diverse groups. For example, structured team-building activities that prioritize cooperative tasks before competitive ones may strengthen intergroup relationships and reduce prejudice. From a neural perspective, the DLPFC and TPJ play distinct yet complementary roles in regulating intergroup attitudes, depending on the interaction context. Specifically, the DLPFC is crucial in reinforcing negative attitudes during competition, while the TPJ plays a key role in fostering positive attitudes during cooperation. These findings suggest potential avenues for targeted interventions. Non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), could be explored to modulate neural activity in these regions, potentially reducing intergroup hostility and promoting social cohesion. Furthermore, understanding the long-term effects of interaction sequences on intergroup attitudes and applying these findings across different populations and contexts could further enhance efforts to improve social harmony.

However, some limitations exist in this study. While we observed that prior interactions have lasting effects on subsequent ones and suggest that different cognitive processes may be involved at each stage, our study did not explicitly explore the specific cognitive processes underlying these interactions, warranting further investigation. Moreover, individual-level factors, such as personality traits, were not measured or analyzed, despite their potential influence on how individuals engage in cooperative and competitive interactions. Future research could incorporate assessments of personality traits to better understand how individual differences shape neural and behavioral responses to intergroup dynamics. While the IPSAP and IPGG effectively represent intergroup competition and cooperation, respectively, their differing task structures may introduce variability in dependent measures. Future studies could explore paradigms that integrate both competitive and cooperative elements within a unified framework to further validate and extend these findings. Additionally, although the minimal group paradigm that we used to create virtual groups in a laboratory was widely used and validated45,46, caution is needed when generalizing these results to real-world groups. Unlike laboratory settings, real-world intergroup interactions often occur in contexts with pre-existing tensions, such as cultural divides, historical conflicts, or socioeconomic disparities, which may significantly influence intergroup attitudes and neural dynamics. Future research should validate these findings in settings with pre-existing intergroup tensions to enhance ecological validity and better understand the broader application of these results in diverse real-world scenarios, such as cross-cultural interactions or long-term group conflicts. Furthermore, while our study focused on immediate interactions and their neural and behavioral effects, the persistence of these effects over time remains unclear. Longitudinal designs could help investigate whether the observed effects of neural synchronization and intergroup attitudes endure beyond immediate interactions and how they are influenced by contextual factors such as interaction frequency, duration, and type. Understanding these long-term dynamics would provide deeper insights into the stability and generalizability of these neural and behavioral changes. Finally, the gender imbalance in our sample, characterized by a significant predominance of female participants, presents a potential limitation to the generalizability of our findings. While previous studies29 suggest that gender may not significantly influence the neural mechanisms of cooperation and competition, caution is still warranted when extending these results to broader populations. Future research should strive for a more balanced gender distribution to ensure broader applicability of the findings.

Methods

Participants and ethics

A total of 142 healthy individuals (124 females, age 18–28 years, mean ± sd = 20.99 ± 2.02 years) were recruited as paid volunteers. To minimize the potential influence of gender and familiarity, dyads were composed of two strangers of the same gender. Due to technical issues, fNIRS data from one dyad was not collected, and another dyad was excluded because one participant did not arrive at the laboratory on time. As a result, data from 138 participants, forming 69 dyads (61 of which were female), were included in the final analysis.

Based on the within (interaction type: competition versus cooperation) by between (interaction order: competition-to-cooperation versus cooperation-to-competition) design, we used G*Power 3.147 to determine the sample size to ensure 80% statistical power. Assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), it was calculated that 24 dyads would be required to detect significant effects with α = 0.05 and β = 0.80. To account for potential dropouts or technical failures, 71 dyads were recruited.

All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. The study was approved by a local research ethics committee at the Department of Psychology, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China (protocol 2023-1220-0318). Before participating, all individuals provided written informed consent after the experimental procedures were fully explained to them. Participants were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Upon completion of the experiment, participants received monetary compensation, consisting of a basic attendance fee plus a bonus based on their performance in the experimental tasks.

Experimental procedures and tasks

Before coming to the laboratory, participants completed an online survey including demographic information and a personality trait questionnaire. Upon arrival at the laboratory for the main experiment, participants were informed that they were assigned to ‘Red Group’ or ‘Blue Group’ according to their responses on online survey. However, the group assignments were actually made randomly. Participants were then given red and blue armbands to indicate their group membership.

The two participants in each dyad were seated in front of separate computers in the same room. Although they faced each other, screens were positioned between them to block their view of one another. This setup allowed them to be aware of each other’s presence without engaging in any verbal or eye contact. Each participant used the keyboard and mouse in front of them to complete computer-based interactive tasks (see Fig. 1b). The experiment consisted of 24 rounds of interactive tasks—12 rounds each of competition and cooperation—conducted while their brain activity was monitored using fNIRS hyperscanning. After every three rounds, participants rated the likability of their ingroup and the outgroup on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much), to capture dynamic changes in intergroup attitudes during competition and cooperation. While participants did not directly interact with ingroup members, comparing ingroup and outgroup ratings provides a relative measure of intergroup bias, which is key to understanding how competition and cooperation influence intergroup relations. Participants rested for one minute every six rounds.

We selected the Intergroup Point Subtraction Aggression Paradigm (IPSAP) and the Intergroup Public Good Game (IPGG) to represent competition and cooperation, respectively. These paradigms were chosen due to their wide validation in social interaction research and their ability to evoke distinct behavioral responses associated with competitive and cooperative contexts. Specifically, the IPSAP effectively elicits competitive behaviors by simulating resource contention, aligning closely with intergroup competition scenarios. Conversely, the IPGG fosters cooperative behaviors by emphasizing collective resource contribution and reciprocity. A critical factor in our selection of these paradigms was their ability to create a strong sense of group identity and realistic interaction dynamics. IPSAP and IPGG provide a more engaging and socially relevant experience, which is essential for studying neural mechanisms and intergroup attitudes within realistic group contexts. While IPSAP and IPGG differ in task structure, this was balanced by prioritizing ecological validity, ensuring that the paradigms simulate intergroup dynamics in a meaningful way. By leveraging these paradigms, our study aims to capture the unique neural synchronization and activity patterns underlying these two contrasting interaction types and explore how transitions between them influence intergroup attitudes.

The interactive tasks were dynamic, fully incentivized games with real-time feedback. Each trial followed the same sequence (Fig. 1c): participants had 20 s to make their decisions (competitive or cooperative), followed by an 8-s waiting screen and a 10-s outcome screen providing feedback based on the task. An 8-s inter-round interval followed the outcome screen, signaling the start of the next round. Each round lasted for 46 s in total, allowing ample time for decision-making and processing of outcome feedback. Before the tasks began, participants received an introduction to the rules and completed two practice trials. The experimenters remained present during the rule explanation and practice trials to ensure participants fully understood the procedures.

The competition task, adapted from intergroup Point Subtraction Aggression30, consisted of 12 rounds with full reset and real-time feedback between rounds. During the 20-s decision-making phase, participants could click on three buttons on the screen to perform three actions: (a) Labor: Increases their own action points, with ten labor clicks adding one action point; (b) Attack: Reduces the opponent’s action points, with one attack click decreasing the opponent’s points by one; (c) Defense: Prevent the opponent’s attack, with one defense click blocking one attack. Participants needed to make their decisions by clicking the buttons within the 20-s timeframe. The side with more action points at the end of the round won and received all the reward points for that round. The reward points varied between 50 and 150, with the specific amount displayed at the beginning of each round. Following the decision-making phase, participants saw a waiting screen for 8 s, followed by a 10-s outcome screen presenting feedback on (1) the action points of both the participant and the opponent and (2) the result of the round, indicating the winner.

The cooperation task, adapted from intergroup Public Good Game30, consisted of 12 rounds with full reset and real-time feedback between rounds. In the decision-making phase, each round began with 100 points available. Participants had 20 s to decide how much they would contribute to a public pool to earn a return. The return was determined by the total contribution to the pool: (a) if the total contribution in the public pool was less than 50, there was no return; (b) if the total contribution was between 50 and 99, it was increased by 1.3 times and divided equally between both participants; (c) if the total contribution was between 100 and 199, it was increased by 1.5 times and divided equally between both participants; (d) if the total contribution in the public pool was 200, it was doubled and divided equally between both participants. In other words, higher contributions to the public pool resulted in greater returns. After the decision-making phase, participants saw a waiting screen for 8 s, followed by a 10-s outcome screen presenting feedback on (1) the contribution of their own; (2) the total contribution in the public pool and the corresponding return rate; (3) their own payoff for that round.

fNIRS data acquisition

NIRScout (NIRx Medical Technologies, New York) was used to record changes in each participant’s oxy-hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HbR) concentrations during the experimental task. In each dyad, both participants had two probe sets positioned on their head: a 5*4 probe set on the right forehead, forming a total of 11 measurement channels and a 3*4 probe set on the right temporal-parietal joint area, forming a total of 8 measurement channels. The probes were placed according to the 10-10 international system. The distribution of the probes was determined using fOLD48 based on the regions of interest. Specifically, the emitters on the right forehead were located at Fp2, AFz, F2 and F6, with detectors at Fpz, AF8, AF4, Fz, and F4. The emitters on the right temporal-parietal joint area were located at CP4, P6, TP8, and C6, with detectors at CP6, P4, and P8. The positions of the probes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The anatomical positions for each channel are shown in Supplementary Table 6. In the signal calibration phase prior to starting the experiment, we adjusted the optodes to ensure optimal contact with the scalp, thereby guaranteeing that the signal quality of each channel reached an acceptable or excellent standard.

Near-infrared light absorption was measured at two wavelengths (785 and 830 nm) with a sampling rate of 7.8125 Hz. Using the modified Beer-Lambert law49, changes in HbO and HbR concentrations were calculated by measuring the absorption of fNIRS light as it passed through tissue. This study focused only on HbO concentration changes, as previous research has identified HbO as the most sensitive indicator of changes in regional cerebral blood flow50. Increases in HbO are recognized as the outcome of neural activity, which correspond to the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal detected by fMRI51,52,53.

Behavioral data analysis

We used R (version 4.4.0)54 to conduct an analysis of variance (ANOVA) at the individual level to explore the effects of interaction on group likability. The dependent variable was group likability, with interaction order (competition-to-cooperation, cooperation-to-competition) served as the between-subjects variable. The within-subjects variables included interaction type (competition, cooperation), evaluation round (3rd, 6th, 9th, 12th), and evaluation target (ingroup, outgroup). The inclusion of the evaluation target in the analysis was to capture the relative measure of intergroup bias, which is critical for understanding how competition and cooperation influence intergroup relations. By comparing ingroup and outgroup likability ratings, we could assess how the likability of the outgroup changes relative to the ingroup, providing insights into shifts in intergroup bias and attitude. Additionally, we used linear regression models to separately examine the influence of interaction outcomes on outgroup likability during competition and cooperation. In the competition condition, the dependent variable was outgroup likability, with the number of wins before each rating as the independent variable. In the cooperation condition, the dependent variable was outgroup likability, with the rewards obtained during cooperation as the independent variable.

fNIRS data analysis

We used MATLAB R2023b to calculate three neural indices for this study: neural synchronization (NS), neural activity of a single brain and rPFC–rTPJ function connectivity. Prior to analysis, we visually inspected the raw fNIRS signals from all channels for each participant to identify artifacts or poor-quality signals. No obviously bad channels were observed in the dataset.

First, we used Homer255 for preprocessing and denoising. We began by using principal component analyses (PCA) to remove the global physiological noise. This was implemented with the enPCAFilter function with nSV = 0.8, meaning 80% of the covariance of the data was removed. Then, we applied the correlation-based signal improvement method (CBSI) to remove head motion artifacts, using the hmrMotionCorrect_Cbsi function. The modified Beer-Lembert law was then used to convert the processed optical density into HbO and HbR values, implemented with the hmrOD2Conc function. After noise removal, we calculated the NS and individual neural activity.

We estimated NS using wavelet transform coherence (WTC) analysis, performed with a Matlab package56, which assesses the cross-correlation between two fNIRS time series generated by each pair of participants over time and frequency57. For each dyad, HbO values were obtained in two time series of equal length and aligned. WTC was applied to these two aligned time series to find regions in the time frequency space where the two time series co-varied.

In our interactive game, each round was divided into three time segments: the 20-s decision-making phase, the 8-s waiting screen phase and the 10-s outcome screen phase. The total length of one round was 46 s, with the shortest event duration being 8 s. Following similar methods from previous studies29, we focused on a frequency band of interest from 0.0217 Hz to 0.125 Hz, which corresponded to the period between 8 s and 46 s of each round. This approach aligns with prior studies that determined the frequency band for wavelet coherence analysis based on the inverse of the time interval between two continuous trials or task-related events12,58. Visual inspection of the wavelet transform coherence graph, confirmed higher coherence values within this frequency band. This frequency band also excluded high- and low-frequency noise such as respiration (around 0.2–0.3 Hz) and cardiac pulsation (around 1 Hz) that could cause artificial coherence. For each round and each channel, the coherence values were calculated within the specific frequency band (0.0217–0.125 Hz).

NS was averaged across all rounds for each channel and submitted to a mixed-model ANOVA with factors of interaction order (competition-to-cooperation versus cooperation-to-competition) × interaction (competition versus cooperation). Significant effects were thresholded at p < 0.05, and FDR corrected for multiple comparisons for all channels to control for type I errors59,60,61. FDR correction was applied whenever multiple tests were conducted. After computing NS, we tested whether applying a Fisher z-transformation would affect the results. The Fisher z-transformation did not change the significance or direction of the results but only slightly altered the magnitude of the values. Therefore, the original NS values were used in all analyses to ensure simplicity and interpretability.

To ensure that the observed differences in NS were specific to the interaction, a set of validation analyses was performed. Within-condition pseudo dyads were generated by randomly pairing two individuals from different original real dyads under the same experimental condition. The permutation process was repeated 1000 times, with each permutation sample consisting of 69 pseudo dyads, to yield a distribution of interactive effects on NS. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the permutation distribution of the 1000 pseudo-dyad samples was then compared with original data. This permutation testing approach31,32 helped determine whether NS was influenced by similar experimental environment or tasks. Additionally, we tested the effect of decision similarity on NS to rule out the possibility that NS was simply a result of participants making similar decisions.

Next, we examined the relationship between neural synchronization and behavioral ratings by conducting regression analyses between NS and the behavioral ratings. Since likability ratings were collected every three rounds, NS values were averaged across every three rounds to serve as the independent variables, while the average likability ratings of the two participants in each dyad served as the dependent variable. Linear regressions were performed separately for each channel, interaction type and interaction order.

We also analyzed individual neural activity to understand its relationship with intergroup attitudes, as group likability were rated by individuals. For individual neural activity, we followed the method used in previous research29. We used the MATLAB-based functions derived from the NIRS-SPM toolbox62 to conduct the pre-processing on the fNIRS de-noised HbO data, following procedures outlined by Yang et al.29. To remove longitudinal signal drift, motion artifacts, and oscillations from respiration and cardiac activity, discrete cosine transforms with a 128-second cutoff period were applied, along with pre-coloring based on the hemodynamic response function. Following data preprocessing, the HbO time series of each channel were then segmented into three phases (the decision-making phase, the waiting screen phase and the outcome screen phase), consistent with the NS analysis. The neural activation during decision-making phase was calculated by converting the HbO during this phase to z-scores, using the mean and standard deviation of the waiting phase, which is in line with Yang et al.29. Neural responses were averaged across every three rounds and submitted to linear regressions, with likability ratings as dependent variables. Linear regressions were performed separately for each channel, interaction type and interaction order.

Moreover, wavelet transform coherence analyses between rTPJ and rPFC were performed for each individual to index the rPFC–rTPJ functional connectivity, which reflects the dynamic coordination between these two brain regions29. For each participant, we computed coherence values for all possible channel pairs between the rPFC (11 channels) and rTPJ (8 channels), resulting in 88 channel pairs. We submitted this rPFC–rTPJ functional connectivity index to order-by-type ANOVA at the channel-pairwise level (each channel pair’s coherence) and at the grand mean level (i.e., the averaged coherence value across the 88 channel pairs).

Statistics and reproducibility

Sample size estimation was performed a priori. Neural data was processed using MATLAB R2023b, while statistical analyses and visualizations were conducted using RStudio with R 4.4.0. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, exact p-values are reported for all significant and non-significant results. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons. The alpha level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests, and all were two-tailed unless otherwise specified. Descriptive statistics include means ± standard deviations (s.d.), as indicated in the tables. Graphs display full data distributions with individual data points, means, and error bars representing 95% CI, while box-and-whisker plots were used to illustrate the range, interquartile range, and median values.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Due to privacy restrictions, data are not publicly available but can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The custom routines for data analysis written in MATLAB and R are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

25 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07945-9

References

Brewer, M. B. In-group bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychol. Bull. 86, 307–324 (1979).

Cikara, M., Bruneau, E., Bavel, J. & Saxe, R. Their pain gives us pleasure: how intergroup dynamics shape empathic failures and counter-empathic responses. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 55, 110–125 (2014).

Maxwell-Smith, M. et al. Competition and intergroup bias: toward a new construal process framework distinguishing competitive perceptions from competitive motivations. Group Process. Interg. 19, 808–832 (2016).

Cikara, M. & Van Bavel, J. J. The Neuroscience of Intergroup Relations: An Integrative Review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9, 245–274 (2014).

Dovidio, J. F. & Banfield, J. C. Intergroup Cooperation (Oxford University Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399813.013.002.

Gaertner, S., Mann, J., Dovidio, J. & Murrell, A. How does cooperation reduce intergroup bias? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59, 692–704 (1990).

Dikker, S. et al. Brain-to-Brain Synchrony Tracks Real-World Dynamic Group Interactions in the Classroom. Curr. Biol. 27, 1375–1380 (2017).

Liu, N. et al. NIRS-Based Hyperscanning Reveals Inter-brain Neural Synchronization during Cooperative Jenga Game with Face-to-Face Communication. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 082 (2016).

Ma, Y. & Tan, H. Representation of intergroup conflict in the human brain. Neuron 111, 1692–1696 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Dyad sex composition effect on inter-brain synchronization in face-to-face cooperation. Brain Imaging Behav 15, 1667–1675 (2021).

Gamliel, H. N. et al. Inter-group conflict affects inter-brain synchrony during synchronized movements. NeuroImage 245, 118661 (2021).

Cui, X., Bryant, D. M. & Reiss, A. L. NIRS-based hyperscanning reveals increased interpersonal coherence in superior frontal cortex during cooperation. NeuroImage 59, 2430–2437 (2012).

Czeszumski, A. et al. Cooperative Behavior Evokes Interbrain Synchrony in the Prefrontal and Temporoparietal Cortex: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of fNIRS Hyperscanning Studies. eNeuro 9, ENEURO.0268-21.2022 (2022).

Todd, A. R. & Burgmer, P. Perspective taking and automatic intergroup evaluation change: Testing an associative self-anchoring account. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 786–802 (2013).

Henschel, N. T. & Derksen, C. The negative secondary transfer effect: Comparing proposed mediation theories. Group Process. Interg. 26, 1271–1288 (2023).

Masters, N., Lloyd, T. & Starmer, C. Do emotional carryover effects carry over? J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 114, 102312 (2025).

Tambini, A., Rimmele, U., Phelps, E. A. & Davachi, L. Emotional brain states carry over and enhance future memory formation. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 271–278 (2017).

Liu, T. & Pelowski, M. Clarifying the interaction types in two-person neuroscience research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, (2014).

Cheng, X., Liu, M. & Pan, Y. Shared responsibility promotes the benefit of interactive decision-making in novices: A hyperscanning study. Acta Psychologica Sinica 54, 1391 (2022).

Piva, M., Zhang, X., Noah, J. A., Chang, S. W. C. & Hirsch, J. Distributed Neural Activity Patterns during Human-to-Human Competition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 571 (2017).

Tei, S. et al. Collaborative roles of Temporoparietal Junction and Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Different Types of Behavioural Flexibility. Sci. Rep. 7, 6415 (2017).

Zhao, H. et al. Acute stress makes women’s group decisions more rational: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fnirs)–based hyperscanning study. J. Neurosci. Psychol. Econ. 14, 20–35 (2021).

Gläscher, J. et al. Lesion mapping of cognitive control and value-based decision making in the prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14681–14686 (2012).

Lantos, D. & Molenberghs, P. The neuroscience of intergroup threat and violence. Neurosci. Biobehav. R. 131, 77–87 (2021).

Carter, R. M. & Huettel, S. A. A nexus model of the temporal–parietal junction. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 328–336 (2013).

Molenberghs, P., Johnson, H., Henry, J. & Mattingley, J. Understanding the minds of others: a neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. R. 65, 276–291 (2016).

Prochazkova, E. et al. Pupil mimicry promotes trust through the theory-of-mind network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E7265–E7274 (2018).

Xue, H., Lu, K. & Hao, N. Cooperation makes two less-creative individuals turn into a highly-creative pair. NeuroImage 172, 527–537 (2018).

Yang, J., Zhang, H., Ni, J., De Dreu, C. K. W. & Ma, Y. Within-group synchronization in the prefrontal cortex associates with intergroup conflict. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 754–760 (2020).

Muñoz-Reyes, J. A. et al. The Male Warrior Hypothesis: Testosterone-related Cooperation and Aggression in the Context of Intergroup Conflict. Sci. Rep. 10, 375 (2020).

Holmes, A. P., Blair, R. C., Watson, J. D. G. & Ford, I. Nonparametric Analysis of Statistic Images from Functional Mapping Experiments. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 16, 7–22 (1996).

Nichols, T. E. & Holmes, A. P. Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: A primer with examples. Hum. Brain Mapp. 15, 1–25 (2002).

Bornstein, G. Intergroup conflict: individual, group, and collective interests. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 7, 129–145 (2003).

Rabbie, J., Benoist, F., Oosterbaan, H. & Visser, L. Differential power and effects of expected competitive and cooperative intergroup interaction on intragroup and outgroup attitudes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 30, 46–56 (1974).

Steinbeis, N., Bernhardt, B. C. & Singer, T. Impulse Control and Underlying Functions of the Left DLPFC Mediate Age-Related and Age-Independent Individual Differences in Strategic Social Behavior. Neuron 73, 1040–1051 (2012).

Yamagishi, T. et al. Cortical thickness of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex predicts strategic choices in economic games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5582–5587 (2016).

Suzuki, S., Adachi, R., Dunne, S., Bossaerts, P. & O’Doherty, J. P. Neural Mechanisms Underlying Human Consensus Decision-Making. Neuron 86, 591–602 (2015).

Lin, L. C., Qu, Y. & Telzer, E. H. Intergroup social influence on emotion processing in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa. 115, 10630–10635 (2018).

Xu, X., Potters, J. & Suetens, S. Cooperative versus competitive interactions and in-group bias. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 179, 69–79 (2020).

Yu, H., Li, J. & Zhou, X. Neural Substrates of Intention–Consequence Integration and Its Impact on Reactive Punishment in Interpersonal Transgression. J. Neurosci. 35, 4917–4925 (2015).

Tausch, N. et al. Secondary transfer effects of intergroup contact: Alternative accounts and underlying processes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 99, 282–302 (2010).

Vezzali, L., Pagliaro, S., Bernardo, G. & Cocco, V. Solidarity across group lines: secondary transfer effect of intergroup contact, perceived moral distance, and collective action. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 53, 450–470 (2022).

Redcay, E. & Schilbach, L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 495–505 (2019).

Schilbach, L. et al. Toward a second-person neuroscience. Behav. Brain Sci. 36, 393–414 (2013).

Otten, S. The Minimal Group Paradigm and its maximal impact in research on social categorization. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 85–89 (2016).

Tajfel, H. Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination. Sci. Am. 223, 96–102 (1970).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Zimeo Morais, G. A., Balardin, J. B. & Sato, J. R. fNIRS Optodes’ Location Decider (fOLD): a toolbox for probe arrangement guided by brain regions-of-interest. Sci. Rep. 8, 3341 (2018).

Obrig, H. & Villringer, A. Beyond the Visible—Imaging the Human Brain with Light. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 23, 1–18 (2003).

Zheng, L. et al. Enhancement of teaching outcome through neural prediction of the students’ knowledge state. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 3046–3057 (2018).

Cui, X., Bray, S., Bryant, D. M., Glover, G. H. & Reiss, A. L. A quantitative comparison of NIRS and fMRI across multiple cognitive tasks. NeuroImage 54, 2808–2821 (2011).

Huppert, T. J., Hoge, R. D., Diamond, S. G., Franceschini, M. A. & Boas, D. A. A temporal comparison of BOLD, ASL, and NIRS hemodynamic responses to motor stimuli in adult humans. NeuroImage 29, 368–382 (2006).

Strangman, G., Culver, J. P., Thompson, J. H. & Boas, D. A. A Quantitative Comparison of Simultaneous BOLD fMRI and NIRS Recordings during Functional Brain Activation. NeuroImage 17, 719–731 (2002).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2024).

Huppert, T. J., Diamond, S. G., Franceschini, M. A. & Boas, D. A. HomER: a review of time-series analysis methods for near-infrared spectroscopy of the brain. Appl. Opt. 48, D280 (2009).

Grinsted, A., Moore, J. C. & Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlin. Processes Geophys. 11, 561–566 (2004).

Torrence, C. & Compo, G. P. A Practical Guide to Wavelet Analysis. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 79, 61–78 (1998).

Osaka, N. et al. How Two Brains Make One Synchronized Mind in the Inferior Frontal Cortex: fNIRS-Based Hyperscanning During Cooperative Singing. Front. Psychol. 6, 1811 (2015).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. Stat. Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Singh, A. K. & Dan, I. Exploring the false discovery rate in multichannel NIRS. NeuroImage 33, 542–549 (2006).

Tak, S. & Ye, J. C. Statistical analysis of fNIRS data: A comprehensive review. NeuroImage 85, 72–91 (2014).

Ye, J., Tak, S., Jang, K., Jung, J. & Jang, J. NIRS-SPM: Statistical parametric mapping for near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage 44, 428–447 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Major Program of National Social Science Foundation of China (18ZDA331 to B.Z.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271128; 32471125 to F.W.). We truly thank Dr. Xia Xiaokai for the important discussions that helped us to improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceived of the project and designed the experiments. Y.L., S.L., and X.G. implemented the experiment and collected data. Y.L. pre-processed the data and performed analyses. Y.L., F.W. and B.Z. discussed results. Y.L. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Artur Czeszumski and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Alizee Lopez-Persem and Jasmine Pan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, Y., Liu, S., Guo, X. et al. Neural synchronization and its impact on intergroup attitudes in dynamic interactions. Commun Biol 8, 312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07776-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07776-8