Abstract

Early life gut microbiota is being increasingly recognized as a major contributor to short and/or long-term human health and diseases. However, little is known about these early-life events in the human microbiome of the lower respiratory tract. This study aims to investigate fungal and bacterial colonization in the lower airways over the first year of life by analyzing lung tissue from autopsied infants. The fungal and bacterial communities of lung tissue samples from 53 autopsied infants were characterized by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), based on universal PCR amplification of the ITS region and the 16S rRNA gene, respectively. Our study highlights a high degree of inter-individual variability in both fungal and bacterial communities inhabiting the infant lung. The lower respiratory tract microbiota is mainly composed of transient microorganisms that likely travel from the upper respiratory tract and do not establish permanent residence. However, it could also contain some genera identified as long-term inhabitants of the lung, which could potentially play a role in lung physiology or disease. At 3–4 months of age, important dynamic changes to the microbial community were observed, which might correspond to a transitional time period in the maturation of the lung microbiome. This timeframe represents a susceptibility period for the colonization of pathogens such as Pneumocystis. The asymptomatic colonization of Pneumocystis was associated with changes in the fungal and bacterial communities. These findings suggest that the period of 2–4 months of age is a “critical window” early in life. Pneumocystis jirovecii could be a potential pivotal ecological driver contributing to shifts in microbial equilibrium during the early-life lower airway microbiome assembly, and to the future health of children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Most human studies have focused on the microbiome of the upper respiratory tract, while little has been investigated about the lower respiratory tract. Lungs have historically been considered as sterile, since the absence of microbial growth from airway samples in clinical examinations was interpreted as an environment free of living microorganisms. However, recent studies using culture-independent approaches such as next-generation sequencing methods (NGS) showed that commensal microbial communities inhabit the lower respiratory tract1,2,3. These studies demonstrated that the lungs of healthy people harbor a microbiota, which is present in low concentration (estimated between 103 to 105 bacteria per gram of tissue), and mainly composed of the genera Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, and Haemophilus4.

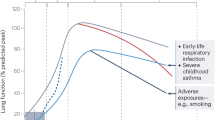

Different epidemiological studies and experimental animal models have associated aberrant development of the upper airways microbiome in early childhood with an increased risk of diverse disease conditions later in life, such as respiratory infections, wheeze, and asthma5,6,7. Commensal microorganisms of the human microbiome play an important role for our health through immune maturation, the development of the mucosal barrier function, and by providing colonization resistance against pathogens8,9. Given the important functions of colonizing microbes, establishing the symbiotic relation between host and microbiota might be crucial for optimal health10. Understanding the assembly of the lower airway microbiome is essential for predicting and directing their future states. The patterns of early-life microbiome colonization of the upper respiratory tract have been thoroughly described11,12,13 but only a single study has investigated its presence in the lower airways, which has mainly been due to the limitations surrounding the invasive sampling procedures in healthy children14.

Studying the lower airway microbiome generally involves the use of bronchoscopic sampling procedures, such as bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchial aspirate, and sputum and lung biopsy. However, these processes require the passage through the upper respiratory tract, which increases the risk of contamination from the pharyngeal microbiome. In addition, healthy control subjects included in these studies were generally patients with respiratory disorders, who don’t always have a healthy microbiome composition. Given this context, it appears difficult to provide the exact structure of the “typical” healthy lung microbiome, which constitutes a state of homeostasis between the microbiome and the host cells. To access the healthy lung microbiome and discard microbial contaminations from the upper respiratory tract, we investigated the microbiome in autopsied lung tissue samples from apparently immunocompetent and healthy infants dying in the community. In previous work, we optimized a DNA extraction method for the characterization of bacterial and fungal communities in lung tissue samples15.

Microbial colonization of mucosal tissues during infancy contributes to the development and education of the host mammalian immune system. Events in early life can have long-standing consequences, such as facilitating environmental exposures or contributing to the development of diseases in later life16. Part of the respiratory microbiome is composed of opportunistic pathogens, but their impact on respiratory health is still underrated. Pneumocystis is an atypical fungus that can be detected in the lungs very early in human life as a mild infection known as colonization17. This fungus is well known for the severe pneumonia that it can provoke in the immunocompromised host18. Interestingly, mild infections by Pneumocystis are capable of inducing airway pathogenic events in small infants and in animal models of primary infection17,19,20,21. However, the early colonization by these opportunist pathogens could have a long-term impact on respiratory health alone, or by conditioning an altered airway microbiome. Bacterial species shifts have been shown to potentially cause disease. Knowledge of the complex interactions among commensal bacteria and primary colonization by opportunistic respiratory pathogens is therefore extremely important, since it could be critical in shaping the airway microbiome composition in early life and respiratory health.

Little is known about lower airway microbiome and the development of this community during the first year of life. We therefore studied the microbiome of lung tissue samples collected from autopsied children by analyzing amplicon sequences of the bacterial 16S rDNA region and the fungal Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region. For the first time, the presence of the fungal communities was characterized in the lung.

Results

Lungs contain a distinct microbiome from microbial contaminant controls

Studies suggested that the presence of microorganisms in the lower respiratory tract might contribute to the course of airway diseases. However, one challenge in working with specimens with low bacterial biomass, such as lung tissue samples, is that some or all the bacterial DNA may derive from contamination in dust or commercial reagents. To investigate this, we compared the microbial composition (fungi and bacteria) of 53 lung tissue samples from infants with a set of contamination controls that were performed in parallel during the DNA extraction process. As shown in Fig. 1, we observed that the lung tissue samples have bacterial and fungal community profiles that are significantly different from those of their respective negative controls (Adonis test P = 0.0017 and P = 0.005 for bacterial and fungal communities, respectively). Regarding the composition of the negative controls (Supplementary Table S1), the genera identified accounted for approximately 25% of the fungal genera and 16% of the total bacterial genera detected in this study, which included both control and lung tissue samples. Although the higher proportion of fungal genera in the negative controls from lung tissue samples raises concerns about potential contamination, it is important to note that the genera present in both controls and samples represented only around 18% of the total fungal genera identified in the lung tissue samples (Supplementary Table S2). Certain fungal genera, such as Aspergillus, Byssochlamys, and Malassezia, which were among the most abundant taxa in the negative controls (comprising up to 20% of the total abundance in control samples), were also present in significantly higher abundance in lung tissue samples, contributing 15%, 6%, and 6% of the total abundance, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). While the presence of these taxa is likely a result of contamination during the DNA extraction process, their relatively higher abundance in lung tissue suggests that they may be biologically relevant to the lung microbiome. These findings underscore the complexity of microbiome studies and the importance of considering contamination sources during DNA extraction. Nevertheless, the separation of control and lung tissue samples in CCA analysis (Fig. 1) suggests that contamination in our study is likely negligible. This supports the robustness and consistency of our approach and further confirms the existence of microbiomes in the human lung.

A small fraction of the total fungal and bacterial communities establishes the core of the Early-Life Lower Airway

For the first time, we characterized the fungal and bacterial community inhabiting the lung tissue of infants (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The analysis of the mycobiome showed that the lung tissue samples were composed of 5.2 ± 2.6 fungal species, ranging from 1 to 16. The lung mycobiome was mainly represented by the phyla Ascomycota (73.8%) and Basidiomycota (12.0%). In total, we identified 38 fungal genera in lung tissue samples. Among them, five (mean abundance ±SD; [prevalence]), identified as Yarrowia (8.6% ± 21.1; [84.9%]), Pneumocystis (29.4% ± 40.9; [60.3%]), Candida (12.9% ± 29.7; [58.5%]), Byssochlamys (6.42% ± 20.6; [39.6%]) and Aspergillus (15.2% ± 31.0; [37.7%]), represented 70% of the total abundance of the fungal community and were retrieved in more than 37% of the lung tissue samples (Fig. 2A, B). On the other hand, 70% of fungal species (27/38) were present in less than 10% of individuals (Supplementary Fig. S1A and Supplementary Table S2). Regarding the bacterial community, 9 distinct phyla were detected in one or more lung tissue samples. The lung tissue samples were mainly colonized by the phyla Firmicutes (51.8% ± 22.0), Proteobacteria (37.5% ± 22.1), Bacteroidetes (7.3% ± 9.3), and Actinobacteria (1.3% ± 2.4); which accounted for 98% of the bacterial community. To a lesser extent, the phylum Fusobacteria (0.5% ± 1.0) was observed in 50% of individuals. Out of the 229 identified genera in lung tissue samples, 9 taxa were present in almost 50% of individuals, entailing 53% of the bacterial community. Among them (mean abundance ±SD; [prevalence]), we retrieved the genera Streptococcus (31.3% ± 25.3; [98%]), Veillonella (2.4% ± 3.3; [77%]), Gemella (5.8% ± 10.0; [74%]), Staphylococcus (1.8% ± 5.2; [70%]), Haemophilus (3.3% ± 8.5; [66%]), Prevotella_7 (1.5% ± 2.9; [62%]), Neisseria (1.0 ± 2.5; [58%]), Pseudomonas (5.3% ± 14.2; [55%]), and Granulicatella (0.8 ± 0.02; [51%]) (Fig. 3A, B). A large proportion, around 70% of genera, was retrieved in fewer than 10% of lung tissue samples, corresponding to 6.8% of the bacterial community (Supplementary Fig. S1B and Table S3). Together, these data reveal that only some microbial species compose the core of the mycobiome and microbiome in the infant lung.

A Relative abundance of the most abundant fungal genera identified in lung tissue samples (present in almost 37% of samples). Sequencing of the ITS region was carried out on 53 lung tissue samples using the Illumina MiSeq platform. A complete list of taxa is provided in the Supplementary Table S2. B Plot of fungal genus prevalence versus relative abundance across samples. Each point corresponds to a different or unique taxon. Red dotted line represents the 30% of prevalence.

A Relative abundance of the most abundant bacterial genera identified in lung tissue samples (present in almost 50% of samples). Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene region was carried out on 53 lung tissue samples using the Illumina MiSeq platform. A complete list of taxa is provided in Supplementary Table S3. B Plot of bacterial genus prevalence versus relative abundance across samples. Each point corresponds to a different or unique taxon. Red dotted line represents the 50% of prevalence.

Changes in the mycobiome and microbiome of the lung occurring at the age of 2–4 months of life

It is well known that age is an important factor influencing the microbial composition of microbiota during infancy. From the microbial sequencing data obtained from our samples, we modeled microbial changes over time of the most prevalent taxa using the edgeR package. For this, we ranged the children by age and grouped infants over 6 months in the same age class. The number of individuals in each age group is shown in the Supplementary Fig. S2. While the fungal and bacterial diversities were not greatly affected (data not shown), changes were observed between 2 and 4 months of age (Fig. 4A, B). The fungal genera Yarrowia, Pneumocystis, and Aspergillus reached an abundance peak before the age of three months, like the bacterial genera Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, and Neisseria. After three months of life, an increasing abundance was observed for the fungal genera Candida and Byssochlamys, but also for the bacterial genera Veillonella, Haemophilus, and Prevotella_7. Nevertheless, some of these most prevalent taxa, such as Gemella and Granulicatella, did not vary during the period of 6 months of age. In general, we note that important changes in the abundance of these main microbial taxa occurred at 2–4 months of age, which could represent a critical period for the lung microbiome assembly.

Dynamic changes of the most abundant fungal (>37% of prevalence) (A) and bacterial (>50% of prevalence) (B) genera during the six months of life. Samples are clustered by age and samples over 6 months of age were ranged in the same age class. The changes of the most prevalent taxa were modeled using the edgeR package in R.

Lower airway mycobiome assembly driven by Pneumocystis

To further describe the compositional differences in the microbial populations, we performed an unbiased partitioning around medoids (PAM) clustering of all lung tissue samples. Based on the highest silhouette coefficient (Supplementary Fig. S3A), we identified six clusters (referred to as microbiota profiles, MPs) in the fungal community, which could be differentiated by the relative abundance of Pneumocystis sp. (Fig. 5A). The abundance of Pneumocystis was lower in the MPs 1 and 2, while it was higher in the MPs 5 and 6. The MPs 3 and 4 had an intermediate abundance of Pneumocystis. All six MPs were detected within the first 2 postnatal months (Fig. 5B). However, the intermediate and high Pneumocystis colonized MPs (MPs 3, 4 and 6) were absent in infants older than 3.5 months of postnatal age. The high Pneumocystis-colonized MP 5 was also identified in the lung tissue of children younger than 3.5 months of age, except for one 6-month-old child. In contrast, the low colonized MPs (MP 1 and 2) were detectable in samples from infants across the whole first year of life. The prevalence and relative abundance of Pneumocystis sp. were statistically higher at the 2-4 months of age period (Fig. 5C, D). Based on the highest silhouette coefficient (Supplementary Fig. S3B), the clustering of bacterial community samples identified two microbiota profiles (MPs) that were mainly distinguished by the abundance of the genera Veillonella and Gemella (Fig. 6A). Both MPs were detectable in samples from infants across the whole first year of life (Fig. 6B). As such, these PAM clusters likely represent the age-related maturation of the lower airway microbial populations. In consequence, Pneumocystis colonization could potentially be an important ecological driver in the assembly of the lung mycobiome between 2 and 4 months of age.

A Composition of fungal profiles (MPs) identified by PAM clustering in the total cohort (n = 53), based on the most abundant fungal genera (present in almost 37% of samples). B Cumulative distribution of samples over the first year of life, stratified by MPs. C Prevalence of Pneumocystis at [0–2], [2–4] and [>4] months life. D Relative abundance of Pneumocystis at [0–2], [2–4] and [>4] months life. Pneumocystis detection was confirmed by qPCR.

Pneumocystis colonization alters the fungal community and to a lesser extent the bacterial community

We observed previously that the MPs composed of high and intermediate abundance of Pneumocystis were detected in infants under 3.5 months of age, suggesting that the presence of Pneumocystis could drive the assembly of the lower airway microbiome during infancy. To evaluate the impact of Pneumocystis colonization on the microbial communities’ structure in infant lungs, we compared the fungal and bacterial composition of infant lung tissue samples according to the relative load of Pneumocystis. For Pneumocystis quantification, the real-time qPCR has been recommended using the Ct values for interpretation of results, although it is a relative measure of the concentration and not a real quantification of fungal load, a standard curve using reference materials being necessary for this purpose22,23,24. In this sense, some authors, using bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) specimens, proposed that patients with mean Ct values of 28 should be categorized as having active pneumonia, while those with a mean Ct value of 35 and above should be considered as colonized22,23,25,26,27. Likewise, another study showed that median Ct values ≥ 36 could be categorized as colonization24. However, a gray area exists between these two cut-off values, for which the patient’s Pneumocystis status (infection or colonization) remains undetermined. Whether the Pneumocystis load impacts the host’s health, it may also have varying effects on the microbiome. Although the Ct threshold has been established for adults and no data exist for infants, we categorized the Pneumocystis-colonized samples into two groups: low Pneumocystis-colonized (Ct values ≥ 36) and highly Pneumocystis-colonized (Ct values < 36). After quantifying the Pneumocystis load in the lung tissue samples by qPCR, these were clustered into 3 groups: Low-PositiveCt≥36 (Ct values ≥ 36), High-PositiveCt<36 (Ct values < 36) and not-colonized by Pneumocystis (No-Pc). The alpha diversity of fungi, using the observed and Shannon index, did not differ among the three groups. Subsequently, beta diversity was measured to evaluate the difference in taxonomic composition between samples, using compositional Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices. The canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) plots, representing taxonomic distances between samples, showed that the microbial composition of the lung tissue samples clustered separately according to the abundance level of Pneumocystis (Fig. 7A). This difference was supported by the significant result of the Adonis test (P = 0.001). While no statistical difference was observed between the microbial profiles of the infants not-colonized and colonized by Pneumocystis, PositiveCt≥36 (Adonis test, P = 0.058), the microbiota profiles of High-PositiveCt<36 infants were significantly different from those of not-colonized (Adonis test, P = 0.001) and Low-PositiveCt≥36 (Adonis test, P = 0.001) colonized. To ensure that the preceding observed differences were not dependent on the presence of Pneumocystis in the samples, data were reanalyzed by subtracting the Pneumocystis reads from the dataset (Fig. 7B). Despite being smaller, a significant difference was still observed between the three groups (Adonis test, P = 0.02). Although the microbiota profile between High-PositiveCt<36 and not-colonized infants remained statistically different (Adonis test, P = 0.045), differences between those of Low-PositiveCt≥36 colonized infants with High-PositiveCt<36 and not-colonized infants were attenuated (Adonis test, P = 0.12 and P = 0.055, respectively). Nevertheless, we cannot discard that this difference might instead be due to the age of infants, as our work previously showed that the colonization of the lung microbiome is age dependent. To assess this, we evaluated the contribution of clinical co-variables, including “age,” “age categories” (as defined in Fig. 4), and “Pneumocystis load” (as defined in Fig. 7: low-positive≥36, high-positive<36, and not colonized by Pneumocystis), to the differences in fungal communities between individuals. We then performed an “envfit” analysis that consists in performing multiple regression of co-variables with ordination axes (Supplementary Fig. S4). We found that fungal composition correlated indeed significantly with the Pneumocystis load (R2 = 0.480, p = 0.003), but not with the co-variables of “age” (R2 = 0.039 p = 1.0) and “age categories” (R2 = 0.156, p = 0.252). Similar results were observed in the analysis considering fungal communities that were depleted in Pneumocystis reads for the Pneumocystis load (R2 = 0.11, p = 0.039), the co-variables “age” (R2 = 0.01, p = 1.0), and for the “age categories”(R2 = 0.13, p = 0.43). To identify specific fungal signatures of infants with Pneumocystis colonization, we compared the relative abundance of taxa between the distinct groups after removing all Pneumocystis sequencing reads (Fig. 7C). Using linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LefSe), taxonomic differences were observed: No-Pc lung tissue samples were enriched with related taxa of Aspergillus penicillioides and Cladosporium genus, whereas High-PositiveCt<36 samples were dominated by Yarrowia bubula. The LefSe analysis revealed that no specific taxa were associated with Low-PositiveCt≥36, although the fungal profile seemed distinct from the No-Pc and High-PositiveCt<36. Similarly, the impact of Pneumocystis colonization on the bacterial community inhabiting the lung of infants was analyzed. The CCA plots revealed that the sample groups clustered separately (Fig. 8A). However, the difference was not significant when using the Adonis test (P = 0.33), which could be attributed to the low diversity and microbial biomass in lung tissue samples, favoring higher inter-individual variations. There was also no difference when the separate groups were analyzed in pairs. By measuring the alpha diversity using the observed diversity and Shannon index, no statistical differences between colonized and not-colonized infants were detected (data not shown). Nevertheless, the comparison of the relative abundance of taxa between the different groups through linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LefSe) revealed that the level of Pneumocystsis colonization affected the composition of the lung microbiome differently (Fig. 8B). PositiveCt<36 tissue samples had an over-representation of Lactobacillus johnsonii whereas PositiveCt≥36 samples were enriched with L. salivarius, Trophomonas maltophilia, Neisseria flavescens, Acinetobacter haemolyticus, and Phyllobacterium myrsinacearum. On the other hand, the microbial signature of No-Pc was composed of the genera Bifidobacterium, Cutibacterium acnes, Ruminococcus bromii, Agathobacter sp., Ruminococcus bicirculans, and Bacteroides vulgatus.

A Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) plots of lung mycobiome according to the load of Pneumocystis. B Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) plots of lung mycobiome in the three groups after removing the Pneumocystis sequencing reads. C LEfSe analysis of lung mycobiome composition (after release of Pneumocystis sequencing reads). Histogram of the LDA scores reveals the most differentially abundant taxa among different level of Pneumocystis colonization.

Discussion

In this present study, the microbial colonization patterns (fungi and bacteria) in lung tissue samples collected from autopsied infants were characterized. A high inter-individual variability in fungal and bacterial communities was observed, as a high proportion of taxa (around 70% of genera) were retrieved in less than 10% of individuals. This lack of ubiquitous microbes shared among samples reveals that the lung microbiome could largely consist of transient microorganisms. It has been hypothesized that these microorganisms could result from microbial migration driven by inhalation, microaspiration, and/or mucosal dispersion4,28,29. This complex microbial–host interface in the lung is mainly determined by microbial elimination through cough, mucociliary transport, and immune mechanisms30. Although these microorganisms colonize the lung only transiently, they should not be underestimated, as they might play an important role in host health. In bladder infection, transient microbiota exposure to Gardnerella vaginalis has been shown to activate dormant Escherichia coli31. Generally, they are missed in clinical diagnosis as they occur before the appearance of disease symptoms, and they have a short-lived exposure. Similarly, the role of this transient microbiome in triggering lung infections should be investigated.

However, our study revealed that a healthy lung microbiome is also composed of a common set of stable microorganisms, as commonly observed in chronic respiratory diseases4,28,29,32. Indeed, five fungal genera (Yarrowia, Pneumocystis, Candida, Byssochlamys and Aspergillus) and nine bacterial genera (Streptococcus, Veillonella, Gemella, Staphylococcus, Haemophilus, Prevotella_7, Neisseria, Pseudomonas, and Granulicatella) were retrieved in the majority of lung samples. These microorganisms were also identified in other studies on the microbiome of the upper respiratory tract and proximal gastrointestinal tract, suggesting that the aspiration of oropharyngeal or gastro-oesophageal contents is the predominant pathway by which microorganisms reach the lower airways. Nevertheless, the detection of these microorganisms in most individuals suggests that they are not just transiting but may correspond to microorganisms colonizing the lung mucosa. These inter-individual shared microorganisms could exert important functions for their host, and their impaired functionality could disrupt the homeostasis in the lung mucosa, leading to disease states. From an ecological perspective, some of these microorganisms could also contribute to the stability of the lung microbiome through nutrient processing or metabolite synthesis. Future studies should aim at studying the ability of these microorganisms to colonize the lung and their contribution to the lung physiology and diseases.

As seen in gut microbiome, we reported a pattern of microbial succession in lung during the first year of life. The modeling of microbial changes over time reveals a transitional time point in the fungal and bacterial colonization of the lower airway at 2–4 months of age. We observed that proportion of the most retrieved fungal and bacterial genera was inverted between 2 and 4 months of age. In parallel, it was shown that the lung microbiome clustered in various MPs whose presence is associated with child age. The composition of early life microbial exposures shapes the maturation of the immune system, with differences in the composition of the microbial community being associated with different changes in the host immune tone14. Only four of the fungal MPs were detected within the 2–4 postnatal months, which differed from others by the higher abundance of Pneumocystis. In effect, the colonization and relative abundance of Pneumocystis were significantly higher during 2–4 months of age. This observation confirms the existence of a critical early-life window of susceptibility for Pneumocystis colonization of the lung. Indeed study documented an incidence peak of Pneumocystis between 3 and 5 months of age in autopsied lungs of Chilean and US infants, using immunofluorescence and molecular methods17. Furthermore, serology studies using MSG, Kexin, or other Pneumocystis antigens document that this colonization induces potent antibody responses, which are frequently detected in infants in the general population33. Changes associated with Pneumocystis colonization could highlight the importance of this fungus in the assembly of the lung microbiome. Additionally, the colonization of Pneumocystis may be influenced by the composition of the microbiome or other factors (e.g., host immune status, environmental conditions) that precede its colonization. Addressing this question would require a longitudinal study, which is not feasible in the context of lung microbiome research. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether Pneumocystis could serve as a marker or driver of lung homeostasis.

Although lung colonization by Pneumocystis in children is generally considered as asymptomatic, studies have shown that it affects the host by inducing a strong, predominantly Th2 immune response in the lung, and enhancing the secretion of mucus that is rich in glycans utilizable by bacteria34,35,36. Moreover, Pneumocystis triggers innate immune responses in the lungs by activating the NF-κB pathway through mannose receptors37. The STAT6 pathway, which is highly dependent on the host, is also strongly activated in response to Pneumocystis38. These immune responses blur the distinction between colonization and infection, underscoring the need for further research to determine whether P. jirovecii should be classified solely as a colonizer or as a transient infectious agent. This immune activation may also contribute to the microbial shifts observed during Pneumocystis colonization. Furthermore, by stimulating other innate immune pathways, microbial organisms within the microbiome could either amplify or suppress the host’s response to Pneumocystis, thereby modulating its overall impact on the lung microbiome. It would be of interest to investigate whether other microbial factors can synergize with, or conversely, counteract the host response to Pneumocystis. Our results reveal that Pneumocystis colonization may mainly affect the fungal community and, to a lesser extent, the bacterial community. More particularly, PositiveCt<36 samples were enriched with Yarrowia bubula and Lactobacillus johnsonii, a commensal bacterium from the small intestine. L. johnsonii supplementation has been shown to reduce airway Th2 cytokines and dendritic cell (DC) function, but also to increase regulatory T cells25. Furthermore, we also observed that these changes correlated with the load of Pneumocystis. In effect, PositiveCt≥36 samples were enriched mainly with L. salivarius, Trophomonas maltophilia, Neisseria flavescens, Acinetobacter haemolyticus and Phyllobacterium myrsinacearum. Consequently, the load of Pneumocystis may determine the alterations in the lung microbiome, which in turn could support the Pneumocystis-induced host changes. Taken together, these observations suggest that Pneumocystis colonization affects the lung microbiome assembly that, directly or indirectly, could influence the host lung physiology through mechanisms, which have not been fully identified. Additionally, integrating mycobiome analysis with serological and T-cell response assessments in future studies could provide a clearer understanding of the immunological footprint of P. jirovecii exposure, helping to differentiate whether observed antibody responses are a result of transient infections or sustained colonization events.

This study has several limitations, notably that recruitment was conducted at a single geographical site, which limits the generalizability of the results to other regions or populations. Environmental, genetic, and socio-economic factors can all influence the microbiome of the lower respiratory tract, although no data are available to date to fully assess these potential impacts. Moreover, the scarcity of clinical data and the inability to collect longitudinal samples limit the interpretation of data. These limitations are inevitable due to the source of lung samples, from legally autopsied infants. Nevertheless, these tissue samples represent a valuable resource to elucidate host–microbe interactions in the lower respiratory tract at early age. Bronchoscopy samples are usually used for accessing the lower respiratory tract microbiome, but they involve risks of contamination with the pharyngeal microbiota, and lung biopsies are not ethical in healthy subjects, limiting the characterization of healthy microbiome in the lower respiratory tract. The access to lung tissue is therefore difficult, and sample collection from autopsied subjects represents an interesting way to characterize their lower airway microbiome, without contamination. Postmortem biological changes, however, could possibly affect our results. Studies comparing microbiomes from various body habitats have reported that the structure of these microbial communities persists during the first 48 h postmortem, suggesting that our samples were not yet contaminated by postmortem bacterial transmigration39. This stability might be attributed to the microcirculation that remains functional for some time after death, more particularly in tissues with abundant vascularization such as those from the brain and lung. Our study does not provide information on the immune status of either the mother or the infant, factors that likely contribute to shaping the infant’s early-life microbiome, particularly with respect to Pneumocystis colonization. Maternal antibodies, transferred during pregnancy, provide passive immunity to the infant and may play a critical role in modulating early microbial exposure. Additionally, the lack of virome characterization could represent an important gap, given the prevalence of viral infections. The presence of viruses may influence microbiome composition through their effects on the host’s immune status. However, the autopsy lung samples analyzed in this study were from infants who died in the community. Our previous work has shown that viral infections, including RSV, influenza, parainfluenza, echovirus, cytomegalovirus, and adenovirus, are rare in samples from infants who die outside of the hospital setting40. Furthermore, while virome characterization through whole shotgun sequencing could offer valuable insights, viruses are generally present at low concentrations in these samples. Achieving sufficient sensitivity for virus detection would require higher sequencing depth, which may not guarantee a complete characterization of the virome.

Conclusions

Our study brings several insights to the field. Although transient microorganisms constitute a large portion of the infant lung microbiome, we identified some genera that could inhabit the lung. We have identified that dynamic changes in the microbiome appear at 3–4 months of age, suggesting that this period could be a “critical window” early in life during which the microbiota can be disrupted in a way that may favor the development of disease later in life. During this period, the colonization by Pneumocystis impacts the composition of the fungal and bacterial communities. Together, these data suggest that the early colonization by Pneumocystis could affect the assembly of the lung microbiome, contributing to the future health of children.

Methods

Lung tissue collection

Autopsied lung tissue samples were obtained from Chilean infants (under one-year-old), whose autopsies were legally requested from the Servicio Médico Legal (Chilean coroner’s office) in Santiago. The Ethics Commission for Studies in Human Subjects of the University of Chile’s School of Medicine approved this study under protocol CEISH #092-2013. Autopsy diagnosis was established on the basis of clinical history, results of post-mortem laboratory tests, and gross findings. Subjects were selected on the basis of unexpected death at home. Additionally, we only included infants that had not previously been admitted to the hospital, those who had no known immunocompromising conditions, and those who showed absence of obvious pulmonary disease on macroscopic examination. Medical information (including age, date of death, autopsy findings, and autopsy diagnoses) was collected from the coroner’s report. Lung tissue samples were collected during the first 24 h postmortem. Out of a total of 128 lung autopsy tissue samples, 53 were randomly selected by an operator blinded to the diagnosis. These included 46 cases of unexplained death, 5 cases of non-pulmonary explained death, and 2 cases of explained deaths diagnosed as bronchopneumonia. The recruited infants died at an average age of 3.1 months (range: 1–12 months; median: 3 months), with 29 males and 24 females. The unexpected and asymptomatic deaths of the infants in this study make these samples non-comparable to the results of the PERCH study on the etiology of pneumonia41. Only one case in this series, histologically diagnosed postmortem as pneumonia, showed no macroscopic evidence of infection but tested positive for Pneumocystis. For each autopsied infant, the right upper lobe was removed using sterile equipment and stored at −80 °C in a sterile plastic bag until processing for analysis. In a biosafety cabinet, the pleurae were carefully removed to access untouched tissue using separate sterile equipment. Briefly, the pleura from lung tissue was removed using sterile tools, followed by cleaning with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Small samples (0.4 g) were then obtained from deep lung tissue, which had been pre-cut into small pieces using separate sterile equipment to minimize contamination. These samples were stored at −80°C for subsequent DNA extraction.

DNA extraction protocol

To avoid airway contamination, lung tissue samples were handled under a laminar flow hood using sterile equipment. Moreover, blank samples comprising the buffer supplied by the QIAamp DNA mini kit were processed together with the lung tissue samples at each DNA extraction series. Microbial DNA was isolated from 0.4 g of lung tissue following the QIAamp DNA mini kit protocol (Qiagen) with modifications that were previously validated15. Briefly, a pre-treatment step was applied consisting of homogenizing the small pieces of lung tissue by magnetic stirrer agitation in 20 mL of sterile PBS (pH 7.2) on ice pack–covered screw-capped flasks for 30 min. The homogenate was filtered using sterile gauze and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min (2900 × g). From the pellet reconstituted in 200 μL of sterile PBS (pH 7.2), total DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) supplemented with a phenol-chloroform and bead-beating steps. DNA concentration was measured using fluorometric quantitation with a Qubit 2 and the Qubit dsDNA high-sensitivity kit. For further analysis, the extracted DNA was stored at −80 °C.

Pneumocystis detection

Pneumocystis-colonized samples were identified through the amplification of the major surface glycoprotein (Msg) by qPCR, following the procedure described previously42. To assess contamination, sterile water was used as a negative control.

16S rRNA gene and ITS amplification, library construction, and sequencing

Bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplification was carried out using primers 5′ -TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′- GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′ (reverse) spanning the V3/V4 hypervariable regions43. PCR conditions used were as follows: 3 min of initial denaturation at 95 °C followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 95 °C), annealing (30 s at 55 °C) and elongation (30 s at 72 °C); with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. As for fungi, an internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, comprising ITS1, 5.8S and ITS2 of the rRNA operon, was amplified using a pre-amplification step with primers44 ITS1-F 5’- TAGAGGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAA-3’ and ITS2-R_KYO2 5’-TTYRCTRCGTTCTTCATC-3’, followed by a second amplification with internal primers44 (ITS1-FInt 5’-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3’, and ITS2_RInt: 5’-CTRYGTTCTTCATCGDT-3’) on 10.5 μl of the primary PCR. PCR conditions for the pre-amplification were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 30 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 95 °C), annealing (30 s at 56 °C) and elongation 20 s at 72 °C; with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The second amplification was conducted according to the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 28 cycles of denaturation (30 s at 95 °C), annealing (30 s at 58 °C) and elongation 30 s at 72 °C; with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. While the bacterial and fungal primers are widely used for microbiome characterization, they do have limitations. Specifically, some fungal or bacterial species may be missed due to slight divergences in their sequences from the primer regions. Internal controls of extraction and amplification were analyzed together with the samples. Amplicons were confirmed by a 1.4% agarose gel, cleaned up and quantified using a Qubit® Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Next, dual indices were attached to both ends of the PCR products using Nextera XT Index Kit (Illumina), and samples were pooled in equimolar ratios for sequencing on a MiSeq desktop sequencer (2 ×300 bp paired-end reads, Illumina).

Data processing

For bacterial and fungal sequences, Dada2 pipeline45 was used to analyze the quality profiles, filter and trim Ns, expected errors and low-quality tails, dereplicate, merge denoised forward and reverse reads, and construct the amplicon sequence variant table to identify and remove chimeric sequences. Human sequences were removed using Bowtie2-2.3.4.2, against the reference human genome database GRCh38.p11, with very sensitive parameters (--very-sensitive: -D20-R3-N0-L20-iS,1,0.50). For taxonomy assignment, the Silva reference database for bacteria and the Unite database for fungi were used, respectively. Finally, counts were obtained for amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) and collapsed to different taxonomic levels. To minimize the effects of contamination by bacteria and fungi from the lab environment, those ASVs found to be identical in negative extraction controls, as well as in the subset of six samples co-extracted with each control, were subtracted from reads of that subset. In the case of fungal community, analyses were carried out using the whole community, as well as after removal of Pneumocystis reads from all samples, in order to assess the remaining fungal community without the influence of this taxon in the downstream analyses. The ASV tables were converted into Biom format, using the QIIME pipeline version 1.9.046 for composition and absolute and relative abundance analyses, as well as for ecological diversity. For comparing groups of samples, ‘normalized’ datasets were generated with the single_rarefaction.py command, which subsamples a subset of sequences containing equal number or total reads per sample. In addition to the initial classification of the individuals as negative or positive, based on the diagnostic PCR for Pneumocystis colonization, positive samples were divided into two subgroups based on the degree of colonization by Pneumocystis, according to the Ct values in the qPCR reactions (Ct < 36 and Ct ≥ 36). Therefore, three groups of samples were established: Negative, PositiveCt≥36 (Ct values ≥ 36), and PositiveCt<36 (Ct values < 36).

Statistics

For alpha diversity, 1000 rarefactions with replacement were carried out and the Shannon diversity index was calculated using the qiime script alpha_diversity.py. Statistical differences in Shannon index between pairs of groups of samples were analyzed using the qiime script compare_alpha_diversity.py, which also generated the corresponding boxplots. As for beta diversity, variation was assessed using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) including the calculation of their corresponding Adonis values for groups using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix created using the vegan package in R version 4.4.047. To identify microbiota profiles in fungal and bacterial communities, we performed unbiased clustering using the Partitioning Around Medoids (PAM) algorithm with Bray-Curtis distance. In this method, each cluster is defined by a central point, the ‘medoid’, which minimizes the distance between samples within the cluster. The optimal number of clusters was determined based on the average silhouette score. The clustering solution with the highest silhouette coefficient was considered the best approach. We also evaluated the contribution of clinical variables linked to the load of Pneumocystis and the age of infants on the differences observed in microbial communities between individuals. For this analysis, we related the sample scores on axes of unconstrained ordination (PCoA) to the clinical variables. This relationship was assessed by correlating the clinical variables with the first two ordination axes and regressing the clinical variables onto the sample scores of selected ordination axes using multiple regression. The significance of the multiple regression was calculated using a permutation test. For this, the function envfit from vegan package was used to calculate multiple regression of clinical co-variable with PCoA axes. Only co-variables showing a significant correlation with PCoA axes (p < 0.05) were considered as drivers of the microbial community. Univariate Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney non-parametrical tests for pairwise comparisons of groups of samples and multivariate feature selection with the Boruta algorithm were also conducted using R version 4.4.047, to sort the most relevant bacteria and fungi in terms of their contribution to the observed differences among sample groups.

Data availability

The sequence data are deposited in EBI Short Read Archive repository (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under the study accession number PRJEB36322 with accession numbers for bacteria from ERS4259937 to ERS4259990 and for fungi from ERS4259991 to ERS4260044, in addition to their respective extraction and amplification negative controls for bacteria (ERS4260045-ERS4260054) and fungi (ERS4260055-ERS4260064).

References

Dickson, R. P. & Huffnagle, G. B. The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and Disease. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004923 (2015).

Segal, L. N. et al. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with oral taxa is associated with lung inflammation of a Th17 phenotype. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16031 (2016).

Yu, G. et al. Characterizing human lung tissue microbiota and its relationship to epidemiological and clinical features. Genome Biol. 17, 163 (2016).

Man, W. H., de Steenhuijsen Piters, W. A. A. & Bogaert, D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 259–270 (2017).

Teo, S. M. et al. Airway Microbiota Dynamics Uncover a Critical Window for Interplay of Pathogenic Bacteria and Allergy in Childhood Respiratory Disease. Cell Host Microbe 24, 341–352.e5 (2018).

de Steenhuijsen Piters, W. A. A., Binkowska, J. & Bogaert, D. Early Life Microbiota and Respiratory Tract Infections. Cell Host Microbe 28, 223–232 (2020).

Ta, L. D. H. et al. Establishment of the nasal microbiota in the first 18 months of life: Correlation with early-onset rhinitis and wheezing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 86–95 (2018).

Turnbaugh, P. J. et al. The human microbiome project. Nature 449, 804–810 (2007).

Cho, I. & Blaser, M. J. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 260–270 (2012).

Scholtens, P. A. M. J. et al. The early settlers: intestinal microbiology in early life. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 3, 425–447 (2012).

Biesbroek, G. et al. Early respiratory microbiota composition determines bacterial succession patterns and respiratory health in children. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190, 1283–1292 (2014).

Teo, S. M. et al. The infant nasopharyngeal microbiome impacts severity of lower respiratory infection and risk of asthma development. Cell Host Microbe 17, 704–715 (2015).

Bosch, A. A. T. M. et al. Maturation of the Infant Respiratory Microbiota, Environmental Drivers, and Health Consequences. A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 1582–1590 (2017).

Pattaroni, C. et al. Early-Life Formation of the Microbial and Immunological Environment of the Human Airways. Cell Host Microbe 24, 857–865.e4 (2018).

Pérez-Brocal, V. et al. Optimized DNA extraction and purification method for characterization of bacterial and fungal communities in lung tissue samples. Sci. Rep. 10, 17377 (2020).

Gensollen, T., Iyer, S. S., Kasper, D. L. & Blumberg, R. S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 352, 539–544 (2016).

Vargas, S. L. et al. Near-universal prevalence of Pneumocystis and associated increase in mucus in the lungs of infants with sudden unexpected death. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56, 171–179 (2013).

Morris, A., Wei, K., Afshar, K. & Huang, L. Epidemiology and clinical significance of pneumocystis colonization. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 10–17 (2008).

Pérez, F. J. et al. Fungal colonization with Pneumocystis correlates to increasing chloride channel accessory 1 (hCLCA1) suggesting a pathway for up-regulation of airway mucus responses, in infant lungs. Results Immunol. 4, 58–61 (2014).

Rojas, D. A. et al. Increase in secreted airway mucins and partial Muc5b STAT6/FoxA2 regulation during Pneumocystis primary infection. Sci. Rep. 9, 2078 (2019).

Méndez, A. et al. Primary infection by Pneumocystis induces Notch-independent Clara cell mucin production in rat distal airways. PLoS One 14, e0217684 (2019).

Fauchier, T. et al. Detection of Pneumocystis jirovecii by Quantitative PCR To Differentiate Colonization and Pneumonia in Immunocompromised HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 1487–1495 (2016).

Alanio, A. et al. Real-time PCR assay-based strategy for differentiation between active Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and colonization in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17, 1531–1537 (2011).

Veintimilla, C. et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia Diagnostic Approach: Real-Life Experience in a Tertiary Centre. J. Fungi 9, 414 (2023).

Robert-Gangneux, F. et al. Diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in immunocompromised patients by real-time PCR: a 4-year prospective study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 3370–3376 (2014).

Alvarez-Martínez, M. J. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of nested and real-time PCR for the detection of Pneumocystis jiroveci in clinical specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 56, 153–160 (2006).

Fan, L.-C., Lu, H.-W., Cheng, K.-B., Li, H.-P. & Xu, J.-F. Evaluation of PCR in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: a bivariate meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One 8, e73099 (2013).

Dickson, R. P. et al. Spatial Variation in the Healthy Human Lung Microbiome and the Adapted Island Model of Lung Biogeography. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 12, 821–830 (2015).

Willner, D. et al. Spatial distribution of microbial communities in the cystic fibrosis lung. ISME J. 6, 471–474 (2012).

Natalini, J. G., Singh, S. & Segal, L. N. The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 222–235 (2023).

Gilbert, N. M., O’Brien, V. P. & Lewis, A. L. Transient microbiota exposures activate dormant Escherichia coli infection in the bladder and drive severe outcomes of recurrent disease. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006238 (2017).

Venkataraman, A. et al. Application of a neutral community model to assess structuring of the human lung microbiome. MBio 6, e02284-14 (2015).

Djawe, K. et al. Seroepidemiological study of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection in healthy infants in Chile using recombinant fragments of the P. jirovecii major surface glycoprotein. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14, e1060-6 (2010).

Morris, A. & Norris, K. A. Colonization by Pneumocystis jirovecii and its role in disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25, 297–317 (2012).

Pérez, F. J. et al. Niflumic Acid Reverses Airway Mucus Excess and Improves Survival in the Rat Model of Steroid-Induced Pneumocystis Pneumonia. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1522 (2019).

Iturra, P. A. et al. Progression of Type 2 Helper T Cell–Type Inflammation and Airway Remodeling in a Rodent Model of Naturally Acquired Subclinical Primary Pneumocystis Infection. Am. J. Pathol. 188, 417–431 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Pneumocystis activates human alveolar macrophage NF-kappaB signaling through mannose receptors. Infect. Immun. 72, 3147–3160 (2004).

Swain, S. D., Meissner, N. N., Siemsen, D. W., McInnerney, K. & Harmsen, A. G. Pneumocystis elicits a STAT6-dependent, strain-specific innate immune response and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 46, 290–298 (2012).

Pechal, J. L., Schmidt, C. J., Jordan, H. R. & Benbow, M. E. A large-scale survey of the postmortem human microbiome, and its potential to provide insight into the living health condition. Sci. Rep. 8, 5724 (2018).

Vargas, S. L. et al. Detection of Pneumocystis carinii f. sp. hominis and viruses in presumably immunocompetent infants who died in the hospital or in the community. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 122–126 (2005).

O’Brien, K. L. et al. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet 394, 757 (2019).

Ruiz-Ruiz, S. et al. A Real-Time PCR Assay for Detection of Low Pneumocystis jirovecii Levels. Front. Microbiol. 12, 787554 (2021).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2012).

Bokulich, N. A. & Mills, D. A. Improved selection of internal transcribed spacer-specific primers enables quantitative, ultra-high-throughput profiling of fungal communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2519–2526 (2013).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010).

R. Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Found. Stat. Comput. Vienna, Austria, 2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Vialaneix N. from the UR875 “Mathématiques et Informatique Appliquées” (INRAE, Toulouse, France) for her advice on the modeling of microbial colonization using the edgeR package. This project has received funding from ERANet LAC (ELAC2014/HID-0254) lead by S.L.V. This project was also supported by a grant from the National Fund for Science and Technology (Fondecyt, Chile) Grant number 1140412 and 1240684 to S.L.V. and Grant number 1231596 to F.M. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection or interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M., S.R.R. and V.P.B. contributed equally to this work. V.S.M., G.G., and M.G. recruited autopsied subjects and collected the lung tissue samples. F.M. and C.P. conducted the experimental work. V.P.B. and F.M. performed the bioinformatics and statistical analyses. F.M., R.B. and C.P. extracted the DNA of lung tissue samples. S.R.R. quantified pneumocystis load by qPCR. F.M. wrote the first draft of the manuscript that was corrected by S.R.R. and V.P.B. A.M. and S.L.V. recruited funding, designed the experimental framework and supervised the work. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Commission for Studies in Human Subjects of the University of Chile´s School of Medicine approved this study under protocol CEISH #092-2013.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks George Smulian and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Magne, F., Ruiz-Ruiz, S., Pérez-Brocal, V. et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii is a potential pivotal ecological driver contributing to shifts in microbial equilibrium during the early-life lower airway microbiome assembly. Commun Biol 8, 609 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07810-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07810-9