Abstract

Social insects such as ants possess a battery of behavioural mechanisms protecting their colonies against pathogens and toxins. Recently, active abandonment of poisoned food was described in the invasive ant Linepithema humile. During this abandonment, foraging declines by 80% within 6–8 h after baits become toxic—a reduction not due to satiety, diminished motivation, or mortality. Here we explore the mechanisms behind this behaviour, testing two hypotheses: (1) the presence of ‘no entry’ pheromones near toxic food, and (2) the formation of aversive memories linked to the toxic food site. In field trials, we placed bridges leading to sucrose, nothing, or poisoned sucrose on an active trail. Within hours, 80% of ants abandoned poisoned bait bridges. By swapping bridges strategically, we confirmed that aversive memories formed at toxic bait sites, while no evidence of a ‘no entry’ pheromone was found. Then, in the laboratory, we asked how ants may be sensing the toxicity of the bait, hypothesising poison-induced malaise. Motility, used as a proxy for malaise, was 29% lower in toxicant-exposed ants after 3 h, linking malaise to abandonment. Developing toxicants with delayed malaise, not just delayed mortality, may improve toxic bait control protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive insect species pose a major economic and ecological challenge, requiring effective management strategies. Among these approaches, toxic baits are considered one of the safest and most environmentally friendly options. However, their efficacy is often limited. Especially difficult to control are invasive social insects, such as ants1, with less than half of eradication attempts succeeding2. Nonetheless, toxic baiting is considered the gold standard approach for ant management3, as baiting has been shown to strongly reduce ant numbers rapidly, and can be deployed even in environmentally sensitive areas4,5,6. The strong reduction in ant presence after bait application is usually assumed to be caused by population reduction due to mortality. However, recent findings have called this assumption into doubt.

Recently, Zanola, et al.7 demonstrated that toxic baits trigger active abandonment of foraging trails and their surrounding areas by the ants. This abandonment begins within approximately 3 h of toxic bait placement, resulting in a 70–80% decrease in activity (often termed ‘traffic’ in other studies) along the trail leading to the toxic bait within 6 h7. Notably, this decrease seems to remain consistent regardless of the initial size of the forager group, and persists for several days. Interestingly, nearby food sources, such as control sucrose feeders, maintain high activity levels, indicating that abandonment is not due to satiety or lack of foraging motivation. While abandonment began within 3 h and reached its maximum within 6 h, in laboratory studies mortality of ants fed the toxic bait was almost zero after 6 h.

This behavioural strategy of abandonment serves as a protective social mechanism, by minimizing the intrusion of harmful substances into the nest. Remarkably, the diminished activity persists over an extended period with minimal fluctuations, indicating a sustained behavioural change among the ants, and no secondary recruitment to the toxic food despite the large population size and full palatability of the toxic food7.

An alternative hypothesis to abandonment is that the foragers collecting the toxic bait suffer malaise and stop visiting the source of the toxic bait, while all other foragers are busy elsewhere8. In this scenario, ants do not return to the toxic bait, and recruitment of new ants does not occur because all the other foragers are occupied with other food sources, leading to a sustained reduction in ants at the toxic food source. Removing a cohort of foragers from a food source, and observing a rapid return to previous activity levels, could exclude this hypothesis. We ran such an experiment, and indeed find foraging returns to baseline levels within 3 h (see methods and results below).

Understanding the mechanism of how such a sustained response persists, resulting in thousands of ants passing near the bait without resumption of foraging, is critical. Hence, this study aims to investigate potential mechanisms leading to trail abandonment. Knowing that ants can likely sense that they have been poisoned, we then investigate the mechanisms leading to active abandonment, proposing two non-mutually exclusive hypotheses: 1) the use of an abandonment pheromone, denoted as “Mark -“ (negative mark), and 2) an aversive memory, referred to as “Memory -,” associated with the toxic bait’s location. An essential premise for studying the latter mechanism is that ants experience malaise within a few hours. Using motility as a proxy for malaise, we confirm that motility in ants which ingested poison drops within 3 h. Thus, this malaise can act as a negative unconditional stimulus to be associated with a neutral one. Ants are known to form long-term appetitive olfactory memories during foraging9,10. In social contexts, just a brief contact is sufficient to create a robust memory11 that during recruitment often overrides any individual evaluation of the resource12. L. humile is known to rapidly form spatial and olfactory associative memories13,14. A ‘no entry’ pheromone has been reported in the pest ant Monomorium pharaonis, deployed when a once-productive food source becomes non-productive15. This ‘no entry’ signal is apparently deployed at the bifurcation point from the main foraging trail to the newly non-productive feeder. However, to our knowledge such a negative pheromone has not since been reported in other ant species, nor has the finding been replicated elsewhere, with at least one direct replication attempt finding no evidence of such a ‘no entry’ signal16. We test these two hypotheses using a bridge-swapping experiment, in which abandonment is triggered on a bridge in one location, and the bridge is then moved to another location, thus moving any putative ‘no entry’ mark while not moving any putative negative memory.

To test the Mark− and Memory− hypotheses, we conducted bridge swaps to generate different combinations of marks (Mark + ; Mark−; No mark) and memories (Memory + ; Memory−; No memory, see Fig. 1). We designed five treatments using bridges that initially offered sucrose, nothing, or toxic bait. After at least 8 h, foraging persisted on sucrose bridges, occasional exploration occurred on no-bait bridges, and toxic bait bridges were abandoned. Bridges with sucrose were assumed to carry a pheromone trail (Mark + ) and be associated with a positive memory (Memory + ). The no-bait bridge was assumed to have no marks or associated memories. Finally, the abandoned toxic bait bridge was assumed to carry a ‘no entry’ signal (Mark− hypothesis), and ants that foraged there may have formed a negative associative memory with its location (Memory− hypothesis). Then bridges were then swapped, resulting in 5 unique combinations (i.e. treatments).

Experimental swapping plan to test the hypothesis of a “stop pheromone” (Mark−; in red), and the hypothesis of an aversive memory associated with a location (Memory−; in red). The hypotheses were tested by swapping bridges and comparing traffic before and after swapping. Five combinations were performed. Initially, in three situations bridges offered sucrose, so were assumed to be marked by trail pheromone (Mark + ) and an appetitive memory was associated to these sites (Memory + ); one offered nothing, so, we assumed there was no mark and no memory there (in blue). The last situation had the toxic bait offered for 8 h on the bridge, and abandonment was confirmed. Thus, this bridge would have the hypothetical Mark− and the hypothetical Memory− (both in red). After swapping, no sugar or toxic bait was offered in any bridge, and the traffic on the bridges was counted before swapping and 2 min after bridge relocation.

Results

Overall traffic

Before bridge swapping, traffic was as expected: high traffic on sucrose bridges, a decrease of 80% lower traffic on bridges offering toxic bait (relative to 8 h previous, when the bridge offered sugar and changed to the toxic bait), and almost no activity on bridges offering nothing (see Fig. 1).

Pairwise tests for each treatment were performed to examine the effect on a given site comparing the traffic before and after bridge swapping. Three treatments represent relevant controls (Fig. 2):

Traffic was measured as the average number of ants crossing a line on the bridges per minute (mean ± SE), before (pink) and after (blue) the swap. The X-axis is indicated in two ways: (1) Labels under the bars refers to what the bridges offered before the swap, showing first (under the pink bar) what the bridge in that location offered and then (under the blue bar) what the bridge brought to this location had offered previously. (2) Numbered treatment refers to the five combinations achieved after bridge swapping, combining memories (Mem + , Mem− or No Mem) and marks (Mark + , Mark−, or No Mark). Before swapping, 3 treatments offered sucrose (Suc), these sites will generate Memory + . In another treatment, the bridge offered nothing (Noth), so this site will generate No memory; in the last treatment, the bridge had toxic bait (Tox) for 8 h, causing abandonment, so this should generate the hypothetical Memory−. In a similar way, the 3 bridges that offered sucrose would have trail pheromone (Mark + ), the one offered nothing would have No mark, and the one abandoned offering the toxic bait would have the hypothetical Mark−. After swapping, all the bridge offered nothing. Within each treatment, differences between Before and After swapping are shown with asterisks (**p < 0.01; no asterisk means no significant differences). Filled circles are the raw data (N = 6).

Treatment 1) Memory + & Mark + (Sham treatment): Manipulation does not cause a significant change in traffic on the bridge (estimate = −0.03; p = 0.55).

Treatment 2) Memory + & No Mark (Site Memory effect): Traffic decreases significantly, as there is no attractive pheromone on the bridge after swapping (estimate = 0.74; p = 0.012). The Memory+ associated with the site, where there was food previously, is enough for the activity to remain at ~54% of initial traffic, even without trail pheromone.

Treatment 3) No Memory & Mark + (Trail Pheromone effect): Here, a bridge presumably marked with an attractive pheromone (Mark + ) was placed in a location which previously offered no food. This triggered immediate recruitment to the bridge (which had no reward), increasing activity by 670% (estimate = −2.09; p = 0.0014). This percentage represented the increase in traffic trigged only by the effect of the trail pheromone on a bridge.

Treatment 4) Memory + and Mark– (Mark− hypothesis): The placement of a bridge that had been previously abandoned due to toxic bait and that could have a negative mark, did not generate a significant decrease in traffic at a site where there was previously a bridge with sucrose (estimate = 0.15; p = 0.31), although we would expect this if a negative mark was present (compare to treatment 2, and see Fig. 3).

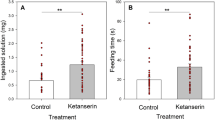

In both panels the horizontal broken line at 1 indicates no change in traffic. Traffic change is expressed as mean ± SE. A Testing the Mark− Hypothesis. Before the swap, both bridges offered sugar solution for one day, so a Memory+ was associated with these two places. When swapping the bridges, if a negative mark exists, the decrease in traffic should be greater when placing a bridge with a negative mark (treatment 4; red bar) than when placing a clean bridge (treatment 2; grey bar). However, there are no significant differences between these two treatments. B Testing the Memory− hypothesis. Before the swapping, nothing was offered on the bridge at one site, so no memory was associated with this site. At the other site, a toxic bait was available for 8 h, resulting in ~80% reduction in activity. A negative memory may thus have been associated with this site. After swapping each of both sites received a bridge with trail pheromone (Mark + ). This should result in a large increase in traffic, unless counteracted by a potential negative memory. Indeed, when a mark+ laden bridge was added to a neutral site (treatment 3, cyan bar), an increase in traffic occurred. Conversely, adding a mark+ laden bridge to a site where toxic bait was previously offered failed to increase traffic (treatment 5, orange bar). This strongly suggests the presence of a negative memory driving, at least partially, the abandonment behaviour described. Differences between treatment are shown with asterisks (***p < 0.001; no symbol: no significant differences). Black circles are the raw data. (N = 6).

Treatment 5) Memory− and Mark + (Memory− hypothesis): Placing a bridge with trail pheromone in a place where a toxic bait was previously present did not generate a change in traffic when compared to the number of ants that were previously on the bridge with the toxic bait (estimate = 0.25; p = 0.56). However, if no Memory− was present we would expect the addition of a Mark+ to cause an increase in the number of ants on the bridge (compare to treatment 3, and see Fig. 3).

Testing the negative memory and pheromone hypotheses

The results presented in Fig. 2 allow us to infer something about our hypotheses since, with respect to the supposed aversive memory, ants from a location without an associated memory willingly entered the bridge with the trail pheromone, thus increasing traffic (p = 0.0014. Figure 2 treatment 3). However, when a bridge with a trail pheromone was placed in a place where a previously abandoned bridge existed, the ants were reluctant to enter it, leaving the activity unchanged (p = 0.56. Figure 2 treatment 5). On the other hand, with respect to the potential Mark−, traffic remained high despite the bridge with the hypothetical Mark− being placed in a location where previously non-toxic sucrose, and so a Memory + , was present (Fig. 2 treatment 4). This already indicates not only that there is no Mark− but that the putative Mark− bridge would possibly even have remnants of the trail pheromone (Mark +).

However, following the logic described in the following rationale, we need to make comparisons of specific treatments to test our hypotheses:

Rationale

It is intuitive to think that replacing a bridge leading to sucrose (Mark+ Memory + ) with a bridge containing the hypothetical Mark− would decrease the traffic on the bridge compared to a sham removal. However, any such decrease could also be caused by a sudden lack of trail pheromone (Mark + ) on the bridge. To demonstrate an active Mark−, the decrease elicited by placing it must be greater than the decrease elicited by placing an unmarked bridge. Therefore, our key comparison for the Mark− hypothesis is

Traffic drop at Memory+ & Mark− > Traffic drop at Memory+ & No Mark

A similar logic holds for a potential Memory−. If a trail that offered toxic bait has been abandoned, and we want to prove that there is some kind of aversive memory involved, placing a bridge with Mark+ at this location should produce no, or a lower, increase in foraging compared to placing a bridge with Mark+ in a location with no associated memory. Thus, the key comparison for the Memory- hypothesis is:

Traffic increase at Memory− & Mark + < Traffic increase at No Memory & Mark+

For the Memory− hypothesis, it is crucial to use Mark+ bridges, not clean bridges, as unmarked bridges would not result in any traffic to compare.

To account for variations in traffic before and after bridge swapping, we calculated the Traffic Change as the ratio of traffic after the swap to traffic before the swap. A Traffic Change value close to 1 indicates no significate change in activity. Values below 1 denote a decrease in traffic, while values above 1 denote an increase (Fig. 3).

To accept the Mark− hypothesis, the decrease in traffic generated by the placement of an abandoned bridge must be greater than the decrease generated by the placement of a clean, i.e. unmarked, bridge. This was not the case (Fig. 3A, estimate = 0.48; p = 0.73). In fact, there is a slight tendency to show a greater reduction when an unmarked bridge is placed than when a bridge with the supposed Mark− is placed. Therefore, we reject the negative mark hypothesis as a mechanism responsible for trail abandonment.

On the other hand, when a bridge marked with trail pheromones is placed where there was no associated memory, and another bridge also marked with Mark+ in a place where abandonment had occurred, indicating that it could have the hypothesized negative memory, we do see a difference in traffic change. An increase in traffic should only occur in the location without a negative memory or, at most, be greater in the place without memory. Indeed, the traffic in the No Memory and Mark+ treatment is significantly higher than in Memory− and Mark+ (Fig. 3B, estimate = −3.78, p < 0.001). This strongly suggests the presence of an aversive or negative memory that at least partially drives the abandonment behaviour described.

Motility assay

The formation of aversive associative memories typically requires the pairing of an unconditioned negative stimulus with an initially neutral one. In this case, malaise caused by the ingestion of toxic bait can act as the negative stimulus. To assess discomfort, we used post-ingestion motility as a proxy in a controlled laboratory assay. If abandonment begins after 3 h post-ingestion, the malaise, and thus reduction in motility, should begin at this time or earlier.

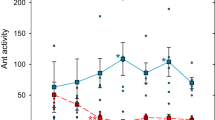

The main analysis (GLM) showed that there was no interaction between treatments and time. However, time itself was significant (p = 0.0017) and a clear tendency (p = 0.058) to lower motility in the treatment with the toxic bait compared to those that consumed sucrose (Fig. 4). We thus chose to go ahead and evaluate the difference at each time using contrasts. Initial motility did not differ between both treatments (estimate: S-T = 0.44; p = 0.16). One hour after ingestion, motility was significantly lower in the toxicant group compared to the sucrose group (S-T = 0.77; p = 0.01). Although a trend was observed after 2 h, the difference was not statistically significant. From the third hour onwards, motility remained consistently lower in the toxic bait group compared to the sucrose group (3 h: S-T = 0.9; p = 0.004; 4 h: S-T = 0.78; p = 0.01; 5 h: S-T = 1.03; p = 0.001; 6 h: S-T = 1.06; p = 0.001. Fig. 4. See Supplementary Section 4 for details)).

Motility is expressed as the number of line crossings per minute per ant, before solution ingestion (baseline, grey violins) and every hour after ingestion. In half of the containers, a sucrose solution was offered (yellow violins), while in the other half, a sucrose + boric acid bait was provided (red violins) immediately after baseline recording. The width of the violins represents the density of the data points at different values, indicating the distribution of motility measurements. Black points represent each container, and square with deviation lines represent mean ± SE. Significant differences are shown between the treatments (Sucrose vs. Toxic bait) within each time. N = 62 containers with 5 ants each (i.e., 31 containers per treatment). (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

Traffic recovery assay

An alternative hypothesis to active abandonment is that malaise stops active foragers returning to a food source, and that all other foragers are occupied, so do not replace the ants missing due to malaise8. Here, we test this hypothesis by removing the cohort of active foragers from a bridge offering a non-toxic feeder, and quantifying traffic on the bridge over time to see if activity resumes previous levels, and if so, how long this takes. To test this, we removed all ants present on the bridge six to seven times at approximately 7-min intervals. While activity initially rebounded after each removal, successive extractions gradually reduced traffic until it reached levels comparable to those of an abandoned bridge.

After 6 or 7 min following the last removal, traffic had significantly decreased by 80% compared to the initial activity, as shown by the 0-time point in Fig. 5. This substantial reduction indicates that the majority of the foraging group was removed and unable to return to the food source. One hour later, traffic increased to about 60% of the initial level but remained significantly lower. After 2 h, traffic on the bridge reached baseline levels. Therefore, foraging activity was fully restored, indicating the recruitment of a new forager group.

Traffic as a percentage of the baseline measurement (100%) over time after the removal of the forager cohort (mean ± SE). Vertical dashed line indicates the repeated ant removal events. Time points are as follows: 0 (a few minutes after the last removal), 1 (1 h later), 2 (2 h later), and 3 (3 h later). Filled circles indicate individual data points, color-coded by replicate. Significant differences relative to initial (baseline) activity are indicated as ***p < 0.001; no symbol: no significant differences). N = 4.

Discussion

In our previous study, we established that ants can collectively abandon areas where toxic baits are present7. Here we tested potential mechanisms for this behaviour. We demonstrated that ants display behavioural changes—specifically a reduction in motility—within an hour of ingesting toxic food. We assume that this reflects the onset of malaise. Such malaise could act as an unconditioned negative stimulus (punishment), and be associated with aspects of the toxic food, such as its location. Indeed, the location in which a bridge leading to toxic bait is situated is avoided by ants. This supports our hypothesis that memory plays a role in driving the abandonment behaviour. Conversely, we found no evidence for a ‘no entry’ pheromone signal (sensu Robinson et al. 2005) driving abandonment: bridges which had led to a toxic bait did not deter ants once they were moved away from a location in which toxic bait was added. Finally, we demonstrate that colonies can replace an entire cohort of foragers if removed. Thus, the sustained abandonment of poisoned baits is unlikely to be due to no new ants being available to replace those which fed on toxic bait – there are always sufficient ants to resume foraging.

Rejecting alternative hypotheses for abandonment

Firstly, let us work through the various alternative hypotheses for the sustained reduction in ant traffic to toxic baits we observe:

Population decline

Under this hypothesis, ants feeding on the toxic bait all die, killing off so many ants that the entire population declines. We ruled this out previously and here by demonstrating that non-toxic baits maintain high forager traffic. Traffic also declines by 80% at the toxic bait bridge within 6 h, whereas barely any mortality occurs within this timeframe7.

Satiation

Under this hypothesis, the decline observed is simply since the colony is no longer interested in foraging, as it is satiated. This can be ruled out as foraging on neighbouring non-toxic sucrose solution is maintained for days7.

Poison unpalatability

Under this hypothesis, the toxic bait is unpalatable, causing ants to stop feeding on it, and thus stop traffic and recruitment. However, palatability tests show that sucrose solution with 3% boric acid shows identical palatability to unpoisoned sucrose solution7, in line with previous studies on this ant species that show identical immediate feeding responses for boric acid sucrose solutions and pure sucrose solutions17,18. If consumption is measured beyond 1 or 2 h, the results will reflect both palatability and abandonment. Indeed, over 8 h twice as much solution was consumed on the sucrose bridge than on the toxic-solution bridge (see Supplementary Section 6).

Malaise coupled with lack of replacement

Under this hypothesis (articulated by Rust8), ants consuming toxic bait suffer malaise and do not return to foraging. A reduction in foraging is sustained because no other ants are available to replace the ants which had ingested poison, either as the population is too small, or because all other ants are specialized on other foraging locations, and essentially ‘busy elsewhere’. We rule this out by demonstrating that, even if we remove the vast majority of active foragers from a feeder by sustained removal until an 80% reduction in forager traffic is achieved, this reduction is not sustained, as within 2 h traffic returns to the original level. Additionally, we note that the abandonment behaviour also involves a significant decrease of traffic on the trunk trail in the broad area around the abandoned location, with detour trails being formed avoiding the entrance to the bridges offering toxic bait7.

Rejection of harmful food in ants

The abandonment behaviour we describe is not the first description of ants avoiding food which is harmful or risky to them, but which cannot immediately be detected as such.

Leafcutter ants cut leaves, which they return to the nest to use a substrate for a fungus garden, which in turn provides food for the ants. Various species of leafcutter ants have been observed to reject even highly palatable food sources when it is tainted with fungicide19,20, although the fungicide is undetectable to the ants19, and not directly harmful to them21. In laboratory settings, this rejection behaviour becomes apparent after the ants are offered pieces of fungicide-laced food for just two days, leading to complete avoidance of the bait, regardless of whether the fungicide is still present21. This rejection behaviour began approximately 10 h after contaminated leaves were introduced into the fungus garden, and persisted for at least nine weeks20. Remarkably, this aversion can persist for up to 30 weeks, indicating a long-lasting effect, likely beyond the lifetime of a single ant. Even naive workers, who have not directly participated in foraging or placing the treated bait in the fungus garden, can develop a delayed rejection response simply through interaction with the affected fungus20,22 or the content of refuse chambers from colonies offered fungicidal leaves23,24. Contact with the damaged fungus, either in the fungus chamber or the garbage dump, is the source of information that a particular food source is detrimental to the fungus25,26. Field studies have corroborated these findings, showing that once the rejection response is triggered, ants will not accept the previously tainted plant variety until 18 weeks have passed without exposure to the fungicide27. This prolonged aversion seems to be largely driven by olfactory memory, though other cues from the plant variety may also be memorized19,28.

While this emerging rejection behaviour shares clear similarities with the abandonment we describe, key distinctions must be made. The delayed rejection typically involves the refusal to handle previously acceptable food, primarily due to aversive olfactory learned cues28. In contrast, the abandonment behaviour we observed encompasses not just food avoidance but also an association between the area and the negative effects of the toxic bait. As a result, the ants can avoid the site where the harmful food was encountered7. Furthermore, since we intentionally avoided adding any odour to the toxic bait, we demonstrated that no odour cue from the harmful food is necessary to achieve abandonment.

The delayed rejection describes the rejection of specific food sources, but it does not refer to what happened on the area where the food was found. The abandonment behaviour we describe involves the animals associating the area where toxic food was found and then avoiding this area.

Area abandonment in ants

Previous studies report trail or area abandonment in ants. Linepithema ants abandons food sources and stop activity in the presence of parasitoids, and return only when the parasitoid is inactive or absent29. Similar observations have been made in other species: Fire ants, Solenopsis richteri, reduce the number of ants at food sources, as well as foraging activity, in the presence of parasitoid phorid flies on trails30. A similar behaviour was observed with Atta vollenweideri, where the presence of phorids on the trails reduced activity, the amount of plant material transported, and the proportion of workers with a preferable size range for parasitoids31. Ants avoid foraging at locations where another ant colony is present32,33,34. Finally, bull ants (Myrmecia midas) and desert ants (Melophorus bagoti and Cataglyphis fortis) have been shown to learn to avoid pitfall traps and areas in which they are repeatedly caught, and develop routes which detour around such areas35,36,37. Similarly, Tetramorium ants are reported to form a generalizable aversive memory of predators’ pit traps after a single capture experience38. However, unlike in the abandonment we describe, these cases involve an immediate detection of risk. While avoidance of trapping is driven by aversive learning, the specific mechanisms underlying area abandonment in response to parasitoids—such as potential learning processes, memory formation, or sensory modulation—have not been thoroughly investigated.

Malaise and Conditioned taste aversion

Post-ingestion aversion is the most plausible explanation for our findings. Given that ants that consumed toxic bait exhibited reduced motility within an hour, and sustained reduced motility within 3 h, it is reasonable to assume they are experiencing malaise. This rapid post-ingestion effect aligns with the well-documented phenomenon of conditioned taste aversion (CTA), where an animal rejects the taste of a specific food after associating it with discomfort following consumption39. Such discomfort may occur even hours after ingestion40,41. The malaise or discomfort acts as a negative unconditioned stimulus to be associated with an initially neutral food. CTA is a widespread adaptive behaviour observed across a variety of species, from humans to invertebrates42,43.

In contrast to solitary species, which typically learn through direct and independent interactions with their environment, animals in social groups often acquire knowledge through observation and interaction with conspecifics44,45. For instance, rats demonstrate the ability to acquire aversions indirectly through social learning46,47. Rats can learn to avoid a particular taste after drinking a liquid in the presence of a poisoned partner, with the ill conspecific serving as a negative unconditioned stimulus48.

While CTA has been demonstrated in some insect species, there is no evidence of its occurrence in others49,50,51,52, with honeybees being a notable example where CTA has been observed53,54, and one study on Argentine ants failing to find evidence of CTA55. However, Argentine ants have been shown to avoid odours associated with nestmate corpses56. While this suggests a potential mechanism for aversion, feeding preferences were not significantly affected56. Additionally, since abandonment begins roughly 3 h after exposure—before any toxic bait-induced mortality occurs—it’s clear that while corpses at the nest might play a role, they are not the primary driver of the observed abandonment.

We acknowledge that the discomfort effect was demonstrated in captive ants in the laboratory, which has inherent limitations. Factors such as dilution through trophallaxis in a large colony could potentially mitigate or eliminate the reduction in motility observed in a natural setting. However, even when reduced motility does not occur, we believe that some form of discomfort must be detected, in order to establish the observed memories. It is important to note that we did not directly test individual memory formation. Further controlled experiments would be valuable to explore the nature and persistence of aversive memories formed in response to toxic bait ingestion, particularly at the individual level (see for example56).

The two tested abandonment mechanisms: rejecting the negative mark hypothesis, supporting the memory hypothesis

We found no evidence for a negative mark—a ‘no entry’ pheromone—in driving abandonment behaviour. Placing a bridge which had previously led to toxic food in a location where non-toxic food was previously available resulted in an indistinguishable response from placing a bridge which led to no food at a similar location (Fig. 3A), whereas if a negative mark was present, we would have expected a significantly larger negative change in traffic when the bridge with that mark was put in place.

Various bee species have been reported to leave negative marks on flowers to signal that a flower has been recently visited, and is thus depleted and not worth revisiting57,58,59,60,61,62. However, later studies have demonstrated that while bees do indeed leave cuticular hydrocarbon marks on flowers, and that other bees attend to these, these marks are not signals, but rather cues. Since flowers bearing these marks tend to be depleted, bees learn to avoid them. However, if these marks are experimentally associated with rewarding flowers, bees readily learn to approach them63,64. In ants, only one instance of a ‘no entry’ has been reported, in Monomorium pharaonis15. This finding has never to our knowledge been positively replicated, but one replication study failed to find evidence for a ‘no entry’ signal16. There is limited evidence for such ‘avoid’ or ‘no entry’ pheromones in social insects, which might be due to insufficient research efforts or the difficulty of observing inhibitory signals compared to positive ones. Alternatively, explicit chemical inhibition might indeed be uncommon in social insect decision-making65.

However, we found good support for a negative memory in driving the abandonment behaviour: Bridges once leading to a non-toxic food source, and so carrying trail pheromone, caused a large increase in ant traffic when placed in a location where previously no food was available. However, they failed to cause an increase in traffic in locations which previously offered poisoned food. Ants, including the Argentine ant, are extremely good learners of both olfactory13,14 and spatial or navigational memories13, see also our findings in Treatment 2,66.

Given this, the finding that toxic food likely results in malaise, and the previously reported area abandonment abilities of ants in response to natural enemies, perhaps it is not surprising that learning plays a role in abandonment. However, major mechanistic puzzles still remain; specifically, how is this memory communicated to other ants?

Given the sustained abandonment of the poisoned feeder and the surrounding area, direct experience of the poison alone cannot explain the abandonment phenomenon. However, we rule out a physical mark on the bridge communicating abandonment. How then do ants without direct experience of the poison know to avoid the area in which poison was found? There is an information disconnection in the system that remains to be clarified. Could ants be transmitting this information symbolically in the nest, much as honeybees transmit food or nest locations using the waggle dance? This seems unlikely, given the information content which would have to be transmitted. Could ants be stationing themselves at the relevant part of the trunk trail and performing a motor display or releasing an avoidance pheromone? This is possible, although we have not noticed such behaviours. Potentially, a negative mark is placed, but only on the trunk trail and not on the bridge, though this also seems unlikely: how would ants know where the trunk trail ends and the foraging trail begins? Similar information disconnections have been reported in ants previously. For example, leafcutter ants carrying leaves overhead can be blocked by low-hanging obstacles over the path. Such obstacles are pruned away, while visual obstacles which do not obstruct laden ants are not67. However, there is an information asymmetry, in that only laden ants can sense that the obstacle is an obstacle, but only unladen ants are free to clear the obstacle. It is clear that there are still great depths to the organization of ant collective behaviour to be explored.

Potential role of malaise-induced reduced recruitment in maintaining abandonment

While our bridge-swapping experiment rules out a pheromonal basis for abandonment initiation, abandonment may be maintained in part by a reduction in recruitment by poisoned ants. Ants are well known to modulate recruitment pheromone deposition in response to a wide range of factors, including but not limited to the (perceived) value of the food source68,69, crowding on the food source and the trail70,71, the distance of the food source from the nest72,73, and more (reviewed in74). It seems reasonable, even likely, that ants experiencing malaise would reduce recruitment, regardless of whether or not their motility is reduced. Unfortunately, while in some ants pheromone deposition is a stereotyped behaviour easily quantified by eye75, this is not the case in L. humile. The quantities of recruitment pheromone deposited are such that quantifying the pheromone, rather than merely detecting it, remains extremely challenging with current technologies76. While this makes chemical quantification difficult, behavioural assays could still provide insights into its role. We thus flag recruitment as potentially playing a major role in abandonment maintenance, but one that remains technically challenging to investigate.

Implications of memory-driven abandonment for Ant Control

Recognizing that ants deploy active abandonment has large implications for the control of invasive and pest ants. Firstly, it is critical to recognize that a drastic reduction in local ant traffic does not necessarily imply high mortality: it could just imply abandonment. Secondly, given that abandonment begins within 3 h of toxic bait presentation, reaching its maximum at 6 h post presentation, maximizing toxic bait intake in the first 3 h is critical to success. These points are discussed in more detail in Zanola et al.7.

The current study strongly suggests that abandonment is driven by an aversive memory linking malaise caused by ingesting a toxicant. This malaise certainly begins within 3 h post-ingestion, and likely within 1 h post-ingestion. It is widely recognized that deploying toxicants with delayed mortality is critical for successful ant control77,78. We argue that searching for toxicants which cause delayed toxicity and malaise would be extremely valuable. Malaise assays are straightforward, cheap, and extremely rapid, and should perhaps be deployed as standard when assessing toxicants or toxic bait formulations.

Conclusions

Here we ruled out alternative hypotheses to abandonment behaviour of invasive ants. We showed that a robust abandonment to toxic bait is probably not based on a repellent pheromone, but is likely driven at least in part by aversive memories associated with toxicant-induced malaise. The mechanism by which spatial information about the location of toxic bait is transmitted to naïve ants is a mystery. However, even at this stage of our mechanistic understanding of this phenomenon, our findings provide concrete suggestions for control of invasive and pest ants: a focus on rapid toxicant uptake, and working towards delayed toxicant malaise.

Methods

Sampling area and times

The field experiment was carried out on the campus of the University of Buenos Aires. This area is heavily infested by Linepithema humile, with many active trunk trails. The experiments were conducted during the warmer months of December – April 2022 and 2023, when ants are most active and many trunk trails can be located around the perimeter of buildings.

A motility assay was conducted in the laboratory as a proxy for malaise. This assay was performed with 4 colonies maintained in the laboratory for at least 6 months.

Solution and toxicant

A 20% (w/w) sucrose solution was used, as this is well accepted by ants and is the most commonly used bait for this species79,80,81. The toxic bait was prepared by adding 3% w/w boric acid to the sucrose solution. Boric acid was chosen because Argentine ants respond well to this bait17,18, and show equal willingness to feed on sucrose solution with 3% boric acid as on pure sucrose solution (Zanola et al. 2024). Additionally, it causes delayed mortality, which is critical for effective control82. The solutions were made with common sugar and tap water.

Experimental design and setup

First, we selected trunk trails with high ant activity. Only trunk trails at least 12 m long and with bi-directional traffic of more than 100 ants/min, measured by counting ants crossing a fixed point on the trail, were used in the experiments.

The experiments involve first offering trunk trails of the ant Linepithema humile an unadulterated sucrose solution via a bridge to a set of feeders. This resulted in a new foraging trail leading from the trunk trail to the feeders. We define Foraging trails as newly established paths that branch off from trunk trails towards a food source we provide at the end of the wooden bridges (sensu Flanagan et al.83).

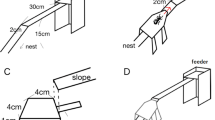

Foraging trails were established by providing a food source (20% w/w sucrose in 4 cotton-plugged 9 ml tubes, henceforth: feeder tubes) on a foraging platform (8 × 5.5 cm) at the end of a bridge (for details see ref. 7). Each bridge was composed of two slats (30 cm each, 60 in total), one horizontal, and one articulated, angling downwards to allow access from the trunk trail. The bridge was raised on vertical posts (c. 25 cm high) surrounded by a water-and-detergent moat, to ensure that access to the platform was exclusively via the bridge entrance. The bridge was covered with painters’ tape which was replaced when starting each experiment and replicate. Feeder tubes were renewed at the beginning and at the end of each day of the experiments.

We allowed the ants to forage on the sucrose feeders for a couple of days to achieve a large number of actively foraging ants. To trigger abandonment, we exchanged the feeder for a new one containing the toxic bait, leaving it for 8 h (abandonment was confirmed in all cases). Then, strategic bridge swapping was performed depending on the desired treatments (see next section).

Experimental procedure

Procedure terminology

We hypothesized two non-mutually exclusive mechanisms for the abandonment response: 1) a chemical ‘no entry‘ signal” (sensu Robinson et al. 2005), which we will refer to as Mark−, and 2) an aversive memory (Memory−) associated with the location of the toxic bait.

Many ants, including L. humile, leave recruitment trail pheromone (“Mark + “ in our terminology) while foraging on sugary solutions76, forming positive memories (“Memory + “) associating the reward with its location13. Thus, while testing the proposed hypotheses, we also need to confirm that offering a sugar solution on a bridge results in a “Mark + “ (the known trail pheromone) on the bridge and a “Memory +“ associated with the bridge’s location. Any potential mechanism for abandonment effect (“Memory−“ or “Mark−“) would counter these positive influences; thus, we also intend to quantify the attractive effects of Memory+ and Mark + . The presence of Mark− or Memory− can be inferred from a reduced number of ants compared to a comparator situation where the negative information is not present.

Procedure

To test the Mark− and Memory− hypotheses, we conducted bridge swaps to create combinations of different marks (Mark + ; Mark−; No mark) with different memories (Memory + ; Memory−; No memory). Thus, we designed five different treatments consisting of distinct combinations of bridges and sites. We set up bridges offering sucrose, nothing, or toxic bait. After a minimum of 8 h, active foraging continued on the sucrose bridges, a few individuals explored the bridge with no bait, and abandonment was confirmed at the toxic bait bridge. The bridges with sucrose were assumed to be marked by a pheromone trail (Mark + ) and their locations associated with a positive associative memory (Memory + ). The bridge with no bait was considered to have no marks and no memories associated with it. Note that L. humile are known to deposit attractive pheromones even during exploration (e.g84.), and thus for the ‘No mark’ treatment the painters’ tape was replaced when switching the bridge location (see below). Finally, the abandoned bridge offering toxic bait was potentially marked with a ‘no entry‘ signal, “Mark−“ (Mark− hypothesis), and the ants that had foraged there potentially formed a negative associative memory with its location (Memory− hypothesis); (see Fig. 1).

We measured the traffic (which was termed ‘ant activity‘ in the previous paper7) on the bridges before and after swapping, i.e., in their original positions and the new positions. To measure traffic, we recorded the ants crossing an imaginary line towards the foraging arena for 7 min, and calculated the mean number of ants per minute.

To swap the bridges, the feeders were first gently removed, and all the ants were knocked off the bridge with a quick blow. The bridge was then placed in the new location. This procedure was developed through preliminary tests evaluating different ways of emptying the bridge. This method results in the same traffic or activity level after 1 min of replacing the bridge back in the original location. In addition, a handling control (sham treatment) was also performed where bridges were replaced in their original locations.

After swapping, foraging was allowed to stabilize for 1 or 2 min, and the same measurements were repeated. Traffic measurements were associated with the same site, not the same bridge: the first measurement is with the original bridge, and after swapping the second measurement is with the new bridge. There were no feeders present after the swapping, and an alternative exit, in the form of a strip of paper leading to the ground, was offered to prevent the platform from filling with ants.

The combinations tested, i.e., the treatments, were as follows.

1) One bridge that offered sucrose was removed and then replaced in the same location after identical manipulation. This acted as a sham manipulation to control for the effects of bridge replacement (“Memory + & Mark + ”).

2) The bridge that offered nothing (No mark) was placed at the site of a sucrose bridge (“Memory + & no Mark”). To ensure that absolutely no trail pheromone was present, the painters’ tape covering the bridge was also replaced. Memory+ associated with a location should be sufficient to sustain some activity on a bridge even if the pheromone trail is removed (by putting a clean bridge)85. So, this treatment allows us to measure the Site Memory effect.

3) The other bridge that offered sucrose was placed in the site that offered nothing, to produce the treatment “No memory & Mark + “. The presence of a Mark+ should be sufficient to trigger activity at the site which previously had the unmarked bridge offering nothing. This allows us to measure the increase in traffic generated by only the presence of the trail pheromone (Trail pheromone effect).

4) The bridge with the hypothetical Mark−, which had offered the toxic bait, was place in the location of a bridge which offered sucrose solution, resulting in the combination “Memory + & Mark−“.

5) A bridge that offered sucrose solution was placed in the site that had offered the toxic bait, resulting in the combination: “Memory− & Mark + “.

This experiment was replicated 6 times on different trunk trails.

Motility test

The formation of an aversive associative memory requires the existence of an unconditioned negative stimulus to be associated with an initially neutral stimulus. Post-ingestion aversion of foods which cause malaise or sickness is well documented in animals, including insects40,49,50,54,86, although tests with a different toxicant (Spinosad) failed to demonstrate conditioned taste aversion in L. humile55. To confirm that ingesting the toxic bait results in malaise, we studied post-ingestion motility as a proxy for discomfort. If abandonment begins after 3 h post-ingestion, the malaise, and thus the reduction in motility, should begin at this time or earlier.

We conducted a laboratory test evaluating groups of 5 ants from three laboratory nests of L. humile after depriving them of carbohydrates for 48 h. The 5 workers were placed in 5 cm diameter plastic containers with fluon-coated walls. The bottom of the container was covered by a paper with a cross drawn in black pencil that divided the surface into quarters.

Data recording began by placing the ants in the container and letting them acclimatize for at least 15 min. Basal motility (t0) was then measured; To do this, two containers were filmed for 1 min simultaneously. Then, half of the groups received a droplet of sugar solution on a small plastic sheet, while the other half received sugar-containing boric acid as used in the field trials; in total 62 containers were filmed (31 containers per treatment). We left the drop for 10–15 min, verifying that all ants ingested the solution. Thereafter the sheet with the drop was carefully removed. We then allowed an hour to elapse and measured motility every hour for 6 h. Motility was quantified from the videos as the number of line crossings performed by the ants in each container over 1 min.

Traffic recovery assay

An alternative hypothesis to active abandonment suggests that discomfort prevents foragers from returning to the food source, and that the absence of these foragers is not compensated by others engaged in different tasks8. We tested this hypothesis by removing active foragers from a bridge with a sucrose feeder and measuring the traffic to assess recovery over time. To this end, a bridge offering sucrose was placed on a trunk trail as above and left in place for one day to establish a consistent flow of ants. Baseline traffic was measured by filming the bridge for 1 min from above for later quantification. Immediately thereafter, the first removal of ants from the bridge was conducted similarly to previous tests, except that ants were collected in a large plastic container with internal walls coated with fluon to prevent escape. The bridge was also brushed with a soft brush to remove any remaining ants. Thereafter, the bridge was returned to the same position with the same sucrose solution feeders. Activity quickly resumed, and after allowing 6 to 7 min, another removal was performed in the same manner. This procedure was repeated 6 to 7 times until a point was reached where, after 6 or 7 min of removal, no further immediate resumption of activity on the bridge was observed. At this juncture, activity was measured again (Activity at time 0: 6 or 7 min after the last removal). The bridge was then left undisturbed, and activity on the bridge was measured hourly. From the video recordings, the number of ants crossing an imaginary line in the direction of the food source within 1 min was counted.

In the first replicate, baseline activity was measured followed by three additional time points (0, 1, and 2). Starting with the second replicate, an additional measurement time was introduced, resulting in time 3 having one less data point. In total, 4 replicates were performed.

Statistics and Reproducibility

For the field assay, the response variable was the traffic measured as the average number of ants crossing a line over 1 min in the direction of the foraging arena. Each replicate corresponded to a trunk trail where the bridges were placed (N = 6).

Statistical analyses were performed in R Studio using the glmTMB, nlme, and multcomp packages87,88, using two-tailed tests. Model assumptions (GLMM) were tested to assess the dispersion and distribution of residuals. Homoscedasticity assumption was assessed using a standardized residuals vs predicted values plot. Normality assumption was evaluated using the Normal QQ Plot. Additionally, normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. If any of the assumptions were not met, alternative probability distributions were explored to find the best fit for the data and/or variance, modelled using a variance function. Pairwise comparisons of activity were conducted using the emmeans package89, and effect sizes were assessed when significant differences were found.

To test the Mark− and Memory− hypotheses, we compared traffic before and after swapping for specific treatments (see Rationale in Results section). As traffic before swapping was not the same in all the sites, we standardized traffic according to the initial traffic at each site. Thus, the response variable was the ratio of the ants’ traffic after the bridge swapping to the initial traffic at that same site. We call this ratio: traffic change.

Two models were constructed: one for comparing the traffic before and after the bridge swapping for each of the 5 situations (treatments) generated (Supplementary Section 2). The other for comparing the traffic change, between pairs of treatments to test the hypotheses (Supplementary Section 3).

Model 1) comparing the traffic before and after swapping in each location

The response variable was the traffic on the bridges, and the best-fitting distribution for the data was a negative binomial distribution. The fixed explanatory variables included the treatments (5 levels: (Mem+ & Mark + ), (Mem+ & No mark), (Mem+ & Mark−), (No mem & Mark + ), (Mem− & Mark + ), and the time point (2 levels: before and after the bridge swap). The random explanatory variables were the replicates (n = 6) and the bridges (18 levels: three bridges per replicate). To perform this analysis, a linear mixed-effects model with an interaction between Time Point and Treatment was used.

Ant traffic ~ Treatment * Time + (random effect: bridge nested within replicate), distribution family: negative binomial (log link function).

Lastly, pairwise comparisons of traffic between treatments were conducted using the emmeans function.

Model 2) comparing traffic change between two treatments

The response variable was the ratio between the final and initial traffic in each trial, to allow trials to be compared. To perform this analysis, a linear mixed effects model was used and it was adjusted to a gamma distribution, which was the most appropriate for the distribution of the data.

The fixed explanatory variable was the treatments: (Mem+ & Mark + ), (Mem+ & No mark), (Mem+ & Mark−), (No mem & Mark + ), (Mem− & Mark + ), (5 levels). The random explanatory variable was the replicates (n = 6). The following model formulae was used (Traffic_change ~ Treatment + (1|Replicate), dispformula = ~ Treatment, data = model2, family = Gamma(link = “log”))

Motility assay

The response variable was motility (number of times the ants -no matter which one- crossed a line of the cross on bottom of the container per minute), and the best-fitting distribution for the data was a negative binomial distribution. The fixed explanatory variables included the treatments (2 levels: Toxic bait and Sucrose) and the time as a continuous variable for the main analysis and as a factor (1–6 h after the toxic bait ingestion) for the contrasts analysis. The random explanatory variables were the replicates (n = 31 containers per treatment) and the time as it continues again. Each replicate consisted of two simultaneous containers, one per treatment, with 5 ants each. To perform this analysis, the model used to analyse the results was the general linear mixed model (GLMM). To evaluate the significance at each time between the treatments, a posteriori contrast was used using the emmeans function87. (See Supplementary Section 5 for details).

Traffic recovery assay

Given the small sample size (n = 4) for this assay, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were employed to analyse the data. GEE is particularly suitable due to its robustness with small sample sizes and its ability to handle correlated data across repeated measures. Additionally, it effectively accommodates the normalized data, where traffic levels are expressed relative to the baseline set at 100% for each replicate. Each replicate corresponded to a trunk trail where the bridges were placed; (N = 4). The explanatory variable was the time point (4 levels: 0 (after forager group extraction), 1 (1 h later), 2 (2 h later) and 3 (3 h later). (See Supplementary Section 5 for details).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from https://figshare.com/s/beb4b8d6a6986794460790.

References

Howse, M. W. F., Haywood, J. & Lester, P. J. Sociality reduces the probability of eradication success of arthropod pests. Insectes Soc. 70, 285–294 (2023).

Hoffmann, B. D., Luque, G. M., Bellard, C., Holmes, N. D. & Donlan, C. J. Improving invasive ant eradication as a conservation tool: a review. Biol. Conserv. 198, 37–49 (2016).

Rust, M. K., Reierson, D. A. & Klotz, J. H. Pest management of Argentine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 38, 159–169 (2003).

Merrill, K. C. et al. Argentine ant (Linepithema humile, Mayr) eradication efforts on San Clemente Island, California, USA. West. North Am. Naturalist 78, 829–836 (2018).

Boser, C. L. et al. Argentine ant management in conservation areas: results of a pilot study. Monogr. West. North Am. Naturalist 7, 518–530 (2014).

Boser, C. L. et al. Protocols for Argentine ant eradication in conservation areas. J. Appl. Entomol. 141, 540–550 (2017).

Zanola, D., Czaczkes, T. J. & Josens, R. Ants evade harmful food by active abandonment. Commun. Biol. 7, 1–12 (2024).

Rust, M. Why don’t ants always fall for toxic bait? They may learn to avoid it. (Interview by Darren Incorvaia). Sci. N.: N./Plants Anim. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.z0e65dj (2024).

Dupuy, F., Sandoz, J.-C., Giurfa, M. & Josens, R. Individual olfactory learning in Camponotus ants. Anim. Behav. 72, 1081–1091 (2006).

Josens, R., Eschbach, C. & Giurfa, M. Differential conditioning and long-term olfactory memory in individual Camponotus fellah ants. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1904–1911 (2009).

Provecho, Y. & Josens, R. Olfactory memory established during trophallaxis affects food search behaviour in ants. J. Exp. Biol. 212, 3221–3227 (2009).

Josens, R., Mattiacci, A., Lois-Milevicich, J. & Giacometti, A. Food information acquired socially overrides individual food assessment in ants. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 70, 2127–2138 (2016).

Wagner, T., Galante, H., Josens, R. & Czaczkes, T. J. Systematic examination of learning in the invasive ant Linepithema humile reveals fast learning and long-lasting memory. Anim. Behav. 203, 41–52 (2023).

Rossi, N. et al. Trail pheromone modulates subjective reward evaluation in Argentine ants. J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb230532 (2020).

Robinson, E. J. H., Jackson, D. E., Holcombe, M. & Ratnieks, F. L. W. ‘No entry’ signal in ant foraging. Nature 438, 442–442 (2005).

Troitino, L. C. Feromônio ‘No entry’ em Monomorium pharaonis: réplica experimental. Master thesis, University of São Paulo (2017).

Sola, F., Falibene, A. & Josens, R. Asymmetrical behavioral response towards two boron toxicants depends on the ant species (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Economic Entomol. 106, 929–938 (2013).

Moauro, M. & Josens, R. Differential feeding responses in two species of nectivorous ants: Understanding bait palatability preferences of Argentine ants. J. Appl. Entomol. 147, 520–529 (2023).

Arêdes, A. et al. Aversive learning as a behavioural mechanism of plant selection in the leaf-cutting ant Atta sexdens (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecol. N. 32, 65–73 (2022).

Herz, H., Hoelldobler, B. & Roces, F. Delayed rejection in a leaf-cutting ant after foraging on plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus. Behav. Ecol. 19, 575–582 (2008).

Ridley, P., Howse, P. E. & Jackson, C. W. Control of the behaviour of leaf-cutting ants by their ‘symbiotic’ fungus. Experientia 52, 631–635 (1996).

North, R. D., Jackson, C. W. & Howse, P. E. Communication between the fungus garden and workers of the leaf-cutting ant, Atta sexdens rubropilosa, regarding choice of substrate for the fungus. Physiol. Entomol. 24, 127–133 (1999).

Arenas, A. & Roces, F. Avoidance of plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus in leaf-cutting ants: learning can take place entirely at the colony dump. PLoS ONE12, e0171388 (2017).

Arenas, A. & Roces, F. Appetitive and aversive learning of plants odors inside different nest compartments by foraging leaf-cutting ants. J. insect Physiol. 109, 85–92 (2018).

Arenas, A. & Roces, F. Gardeners and midden workers in leaf-cutting ants learn to avoid plants unsuitable for the fungus at their worksites. Anim. Behav. 115, 167–174 (2016).

Alma, A. M., Arenas, A., Fernandez, P. C. & Buteler, M. The refuse dump provides information that influences the foraging preferences of leaf-cutting ants. Ecol. Entomol. 50, 1–9 (2024).

Saverschek, N., Herz, H., Wagner, M. & Roces, F. Avoiding plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus: learning and long-term memory in leaf-cutting ants. Anim. Behav. 79, 689–698 (2010).

Saverschek, N. & Roces, F. Foraging leafcutter ants: olfactory memory underlies delayed avoidance of plants unsuitable for the symbiotic fungus. Anim. Behav. 82, 453–458 (2011).

Orr, M. R. & Seike, S. H. Parasitoids deter foraging by Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) in their native habitat in Brazil. Oecologia 117, 420–425 (1998).

Folgarait, P. J. & Gilbert, L. E. Phorid parasitoids affect foraging activity of Solenopsis richteri under different availability of food in Argentina. Ecol. Entomol. 24, 163–173 (1999).

Guillade, A. C. & Folgarait, P. J. Effect of phorid fly density on the foraging of Atta vollenweideri leafcutter ants in the field. Entomologia Experimentalis Applicata 154, 53–61 (2015).

Nonacs, P. & Dill, L. M. Foraging response of the ant Lasius pallitarsis to food sources with associated mortality risk. Insectes Sociaux 35, 293–303 (1988).

Nonacs, P. & Dill, L. M. Mortality risk vs. food quality trade-offs in a common currency: ant patch preferences. Ecology 71, 1886–1892 (1990).

Nonacs, P. & Dill, L. M. Mortality risk versus food quality trade-offs in ants: patch use over time. Ecol. Entomol. 16, 73–80 (1991).

Lionetti, V. A. G., Deeti, S., Murray, T. & Cheng, K. Resolving conflict between aversive and appetitive learning of views: how ants shift to a new route during navigation. Learn. Behav. 51, 446–457 (2023).

Wystrach, A., Buehlmann, C., Schwarz, S., Cheng, K. & Graham, P. Rapid aversive and memory trace learning during route navigation in Desert ants. Curr. Biol. 30, 1927–1933.e1922 (2020).

Freas, C. A., Wystrach, A., Schwarz, S. & Spetch, M. L. Aversive view memories and risk perception in navigating ants. Sci. Rep. 12, 2899 (2022).

Hollis, K. L., McNew, K., Sosa, T., Harrsch, F. A. & Nowbahari, E. Natural aversive learning in Tetramorium ants reveals ability to form a generalizable memory of predators’ pit traps. Behav. Process. 139, 19–25 (2017).

Garcia, J., Kimeldorf, D. J. & Koelling, R. A. Conditioned aversion to saccharin resulting from exposure to gamma radiation. Science 122, 157–158 (1955).

Garcia, J., Ervin, F. R. & Koelling, R. A. Learning with prolonged delay of reinforcement. Psychonomic Sci. 5, 121–122 (1966).

Etscorn, F. & Stephens, R. Establishment of conditioned taste aversions with a 24-hour CS-US interval. Physiol. Psychol. 1, 251–253 (1973).

Chambers, K. C. Conditioned taste aversions. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. - Head. Neck Surg. 4, 92–100 (2018).

Nakai, J., Totani, Y., Kojima, S., Sakakibara, M. & Ito, E. Features of behavioral changes underlying conditioned taste aversion in the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis. Invertebr. Neurosci. 20, 8 (2020).

Marchesini, R. in The Creative Animal: How Every Animal Builds its Own Existence 211–243 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Danchin, É., Giraldeau, L.-A., Valone, T. J. & Wagner, R. H. Public information: From nosy neighbors to cultural evolution. Science 305, 487–491 (2004).

Galef, B. G. Jr. Direct and indirect behavioral pathways to social transmission of food avoidance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 443, 203–215 (1985).

Bond, N. W. Transferred odor aversions in adult rats. Behav. Neural Biol. 35, 417–421 (1982).

Lavin, M. J., Freise, B. & Coombes, S. Transferred flavor aversions in adult rats. Behav. Neural Biol. 28, 15–33 (1980).

Bernays, E. A. & Lee, J. C. Food aversion learning in the polyphagous grasshopper Schistocerca americana. Physiol. Entomol. 13, 131–137 (1988).

Behmer, S. T., Elias, D. O. & Bernays, E. A. Post-ingestive feedbacks and associative learning regulate the intake of unsuitable sterols in a generalist grasshopper. J. Exp. Biol. 202, 739–748 (1999).

Ghumare, S. S. & Mukherjee, S. N. Absence of food aversion learning in the polyphagous noctuid, Spodoptera litura (F.) following intoxication by deleterious chemicals. J. Insect Behav. 18, 105–114 (2005).

Wright, G. A. et al. Parallel reinforcement pathways for conditioned food aversions in the honeybee. Curr. Biol. 20, 2234–2240 (2010).

Ayestarán, A., Giurfa, M. & de Brito Sanchez, M. G. Toxic but drank: gustatory aversive compounds induce post-ingestional malaise in harnessed honeybees. PLoS ONE5, e15000 (2010).

Hurst, V., Stevenson, P. C. & Wright, G. A. Toxins induce ‘malaise’ behaviour in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). J. Comp. Physiol. A 200, 881–890 (2014).

Galante, H., Forster, M., Werneke, C. & Czaczkes, T. J. Invasive ants fed spinosad collectively recruit to known food faster yet individually abandon food earlier. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.06.20.599949 (2024).

Wagner, T. & Czaczkes, T. J. Corpse-associated odours elicit avoidance in invasive ants. Pest Manag. Sci. 80, 1859–1867 (2024).

Giurfa, M. & Núñez, J. A. Honeybees mark with scent and reject recently visited flowers. Oecologia 89, 113–117 (1992).

Corbet, S. A., Kerslake, J., Brown, D. & Morland, N. Can bees select nectar-rich flowers in a patch. J. Apicultural Res. 23, 234–242 (1984).

Wetherwax, P. B. Why do honeybees reject certain flowers? Oecologia 69, 567–570 (1986).

Frankie, W. & Vinson, S. B. Scent marking of passion flowers in Texas by females of Xylocopa virginica texana (Hymenoptera: Anthophoridae). J. Kans. Entomol. Soc. 50, 613–635 (1977).

Cameron, S. A. Chemical signals in bumble bee foraging. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 9, 257–260 (1981).

Kato, M. Bumblebee visits to Impatiens spp.: pattern and efficiency. Oecologia 76, 364–370 (1988).

Saleh, N. & Chittka, L. The importance of experience in the interpretation of conspecific chemical signals. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61, 215–220 (2006).

Leadbeater, E. & Chittka, L. Do inexperienced bumblebee foragers use scent marks as social information? Anim. cognition 14, 915–919 (2011).

Goldberg, T. S. & Bloch, G. Inhibitory signaling in collective social insect networks, is it indeed uncommon? Curr. Opin. insect Sci. 59, 101107 (2023).

Galante, H. & Czaczkes, T. J. Invasive ant learning is not affected by seven potential neuroactive chemicals. Curr. Zool. 70, 87–97 (2023).

Bruce, A. I., Czaczkes, T. J. & Burd, M. Tall trails: ants resolve an asymmetry of information and capacity in collective maintenance of infrastructure. Anim. Behav. 127, 179–185 (2017).

Wendt, S., Strunk, K. S., Heinze, J., Roider, A. & Czaczkes, T. J. Positive and negative incentive contrasts lead to relative value perception in ants. eLife 8, e45450 (2019).

Beckers, R., Deneubourg, J. L. & Goss, S. Modulation of trail laying in the ant Lasius niger (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and its role in the collective selection of a food source. J. Insect Behav. 6, 751–759 (1993).

Czaczkes, T. J., Grüter, C. & Ratnieks, F. L. W. Negative feedback in ants: crowding results in less trail pheromone deposition. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20121009 (2013).

Wendt, S., Kleinhoelting, N. & Czaczkes, T. J. Negative feedback: ants choose unoccupied over occupied food sources and lay more pheromone to them. J. R. Soc. Interface 17, 20190661 (2020).

Devigne, C. & Detrain, C. How does food distance influence foraging in the ant Lasius niger: the importance of home-range marking. Insectes Soc. 53, 46–55 (2006).

Czaczkes, T. J., Olivera-Rodriguez, F.-J. & Poissonnier, L.-A. Ants (Lasius niger) deposit more pheromone close to food sources and further from the nest but do not attempt to update erroneous pheromone trails. Insectes Soc. 71, 367–376 (2024).

Czaczkes, T. J., Grüter, C. & Ratnieks, F. L. W. Trail Pheromones: An Integrative View of Their Role in Social Insect Colony Organization. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60, 581–599 (2015).

Beckers, R., Deneubourg, J. L. & Goss, S. Trail laying behavior during food recruitment in the ant Lasius niger (L). Insectes Soc. 39, 59–72 (1992).

Choe, D.-H., Villafuerte, D. B. & Tsutsui, N. D. Trail pheromone of the Argentine ant, Linepithema humile (Mayr) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). PLoS ONE7, e45016 (2012).

Stringer, C. E. Jr., Lofgren, C. S. & Bartlett, F. J. Imported fire ant toxic bait studies: evaluation of toxicants. J. Economic Entomol. 57, 941–945 (1964).

Klotz, J. H., Vail, K. M. & Willams, D. F. Toxicity of a boric acid-sucrose water bait to Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Economic Entomol. 90, 488–491 (1997).

Sola, F. J. & Josens, R. Feeding behavior and social interactions of the Argentine ant Linepithema humile change with sucrose concentration. Bull. Entomol. Res. 106, 522–529 (2016).

McCalla, K. A., Tay, J.-W., Mulchandani, A., Choe, D.-H. & Hoddle, M. S. Biodegradable alginate hydrogel bait delivery system effectively controls high-density populations of Argentine ant in commercial citrus. J. Pest Sci. 93, 1031–1042 (2020).

Silverman, J. & Brightwell, R. J. The Argentine ant: challenges in managing an invasive unicolonial pest. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 53, 231–252 (2008).

Rust, M. K., Reierson, D. A. & Klotz, J. H. Delayed toxicity as a critical factor in the efficacy of aqueous baits for controlling Argentine ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Economic Entomol. 97, 1017–1024 (2004).

Flanagan, T. P., Pinter-Wollman, N. M., Moses, M. E. & Gordon, D. M. Fast and flexible: argentine ants recruit from nearby trails. PLoS One 8, e70888 (2013).

Reid, C. R., Sumpter, D. J. T. & Beekman, M. Optimisation in a natural system: Argentine ants solve the Towers of Hanoi. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 50–58 (2011).

Czaczkes, T. J., Salmane, A. K., Klampfleuthner, F. A. M. & Heinze, J. Private information alone can trigger trapping of ant colonies in local feeding optima. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 744–751 (2016).

Garcia, J. & Koelling, R. A. Relation of cue to consequence in avoidance learning. Psychonomic Sci. 4, 123–124 (1966).

Brooks, M. et al. Package ‘glmmTMB’. Generalized Linear Mixed Models using Template Model Builder. R Core Team V. 1.1.7, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmmTMB/glmmTMB.pdf (2023).

Pinheiro, J. et al. Package ‘nlme’. Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R Core Team. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.nlme (2023).

Lenth, R. V. et al. Package ‘emmeans’. Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeans (2023).

Zanola, D., Czaczkes, T. J. & Josens, R. Dataset for “Toxic bait abandonment by an invasive ant is driven by aversive memories”. Figshare, https://figshare.com/s/beb4b8d6a69867944607 (2025).

Acknowledgements

RJ was supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (Argentina. PIP 2021: 11220200102201CO) and the National Agency for the Promotion of Research, Technological Development and Innovation (PICT 2016-1676; PICT S-up 2017-9). TJC was supported by a Starter grant from the European Research Council (Cognitive Control: 948181) and a Heisenberg grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Projektnummer 462101190.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J. and T.J.C. conceived the study, supervised the project, and acquired funding. R.J., T.J.C. and D.Z. designed the experiment. D.Z. collected and analysed the data, and wrote the preliminary manuscript. R.J. and T.J.C. jointly wrote the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

: Communications Biology thanks Chris Reid, Karina Amaral, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors Richard Holland and Jasmine Pan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanola, D., Czaczkes, T.J. & Josens, R. Toxic bait abandonment by an invasive ant is driven by aversive memories. Commun Biol 8, 486 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07818-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07818-1

This article is cited by

-

Toxic bait abandonment by an invasive ant is driven by aversive memories

Communications Biology (2025)