Abstract

Global warming is widely predicted to drive adaptive responses in species’ morphology, yet such responses have rarely been demonstrated to track changing climate through time. We investigated associations between avian bill size and changes in seasonal climate extremes using museum specimens of 57 Australian passerine species (Meliphagides). We employed location-specific climate data from the 4119 sites where specimens were collected to test whether change in the frequencies of summer (≥35 °C) and winter (<5°C) extremes over the preceding 20 years of each specimen’s collection date was associated with bill size variation as predicted by thermoregulatory hypotheses. Rapid warming in summer and winter was associated with bill size variation in accordance with the bill’s role in heat exchange. Our study provides critical evidence that bill size is tracking climate change through time in response to changing thermoregulatory demands. A critical future question is whether such changes facilitate species persistence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is abundant evidence that organisms are responding to contemporary climate change, including by shifting the timing of major life events such as breeding and migration (phenology), and through geographic range shifts1,2,3. Changes in animal morphology, in traits linked to thermal performance, have also been documented4,5,6. Despite the plethora of correlative studies linking responses and climate, demonstrations of underlying mechanisms, the links with selection remain surprisingly rare7. This makes it difficult to predict biodiversity responses to ongoing change and to adapt conservation initiatives.

Recent advances in understanding the role of morphological traits in thermal performance have led to increased interest in this topic. Much work has focussed on animal body size, and recently the appendages of endotherms (avian bills and legs, ears and tails in mammals) have attracted attention because they too have importance in thermoregulation and the maintenance of homoeostasis6,7,8. Of avian appendages, the bill has received most attention because this uninsulated structure provides an ideal surface for heat exchange, in addition to its primary role in foraging9. In hot conditions, birds can increase blood flow to the bill to increase heat loss via radiation while in cold conditions, vasoconstriction facilitates heat retention10,11. Indeed, recent studies have confirmed that a significant portion of body heat is released from the bill surface via radiation at high environmental temperatures, reducing the need for evaporative cooling10,12. The Toco toucan, Ramphastos toco, for example, can shunt up to 60% of its heat load through the bill when air temperatures exceed 28 °C10. Heat loss via the bill can also be important in species with relatively small bills13. For example, the song sparrow, Melospiza melodia, can dissipate up to 10% of its heat load via the bill even though it accounts for only about 2% of total surface area13. Conversely, in cold conditions, vasoconstriction can significantly limit heat loss from bills; in white Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos), >85% of total metabolic heat is released from a vasodilated bill at 0 °C, whereas only 18–25% is lost from a vasoconstricted bill11. The larger the bill, the greater the potential for heat exchange, so larger bills relative to body size may be advantageous in hot conditions but become a liability in cold conditions13. Accordingly, bill morphology has direct significance for thermoregulatory function, helping to maintain body temperature within the narrow operating range that is critical for endotherm survival10.

Indeed, Allen’s and Bergman’s Rule describe spatial patterns of morphological variation4 and increasing availability of fine-scale, location-specific climate data has facilitated studies linking climate and morphological variation across geographic space, thereby permitting specific tests of thermoregulatory hypotheses. For example, recent work shows that larger bill size may be a particularly important adaptation in hot, arid environments where water availability is limited in summer12,13,14 because heat dissipation via the bill does not involve evaporative water loss, thereby improving water conservation15,16,17,18. In extremely hot environments, however, large bill size may be costly due to the risk of heat uptake. Where environmental temperatures exceed body temperature (~40 °C), the bill will absorb heat from the environment rather than dissipate it, so the advantages of large bill size may be reversed in extremely hot climates, becoming maladaptive in climates where summer temperatures regularly exceed body temperature19. Indeed, although relative bill size in song sparrows increased monotonically with ambient temperature across their range, bill size decreased in parts of their range where average summer temperatures exceeded body temperature, above about 36 °C14. This indicates non-linear associations between summer temperatures and optimal bill size. This non-linear response to summer heat has now been demonstrated across multiple species, providing strong support for this hypothesis20,21.

Subasinghe et al.21 provides the best evidence to date for the ecological significance of the avian bill in its role as a thermoregulatory organ. Their study of spatial variation in bill size across a superfamily of Australasian birds (Meliphagides) focussed on climate extremes in contrast to most previous studies focussing only on climate means, which do not reflect thermoregulatory costs experienced over shorter time scales. They argued that it is crucial to clarify associations between bill size and climate extremes, which are known to be associated with physiological performance and fitness, to understand the ecological significance of thermoregulatory mechanisms as drivers of bill size variation. In their continent-wide spatial analysis of 79 species, they demonstrated that exposure to higher frequencies of climate extremes in summer and winter was associated with variation in bill size across geographical space in directions consistent with thermal physiology. Earlier studies have also demonstrated bill size variation across space and suggested thermoregulation underlies such variation13,22. However, failure to account for climate extremes and the non-linear nature of bill size responses to extreme summer heat, in combination with limited morphological sampling, inevitably limits capacity to infer underlying thermoregulatory mechanisms. Based on their study21, Subasinghe et al. concluded that climate extremes have contributed to the evolution of bill morphology and predict that changes in the frequency, intensity and duration of climate extremes, a signature of contemporary climate change, will lead to changes in bill size over time as thermoregulatory demands change.

Despite strong predictions, direct evidence for temporal, rather than spatial, climate-related change in bill size is rare6,8. Large sample sizes are required to detect relatively small changes in morphology over the previous ca. 50 years when the climate has been changing rapidly, and long-term studies of wild populations at single locations that could provide such data are rare. Accordingly, museum specimens are often used to estimate morphological variation, with adequate sampling relatively available across geographic space. However, the temporal sampling of individual populations required to estimate change over time is limited by the scale of museum sampling. Moreover, testing thermoregulatory hypotheses for size change requires access to daily climate data at biologically meaningful spatial and temporal resolutions, across entire study areas, and such data are only recently becoming freely available for Australia.

Here we used a novel approach, taking advantage of location-specific interpolated climate data, to estimate the change in frequencies of climate extremes experienced over 20 years prior to capture for each of the 4119 birds in our museum-based morphometric dataset. We then tested whether changes in the frequencies of summer (≥35 °C) and winter (<5 °C) extremes were associated with bill size (surface area) variation predicted from the spatial analyses of Subasinghe21, in accordance with thermoregulatory hypotheses. Our aim was to test whether bill size is changing over time, rather than across space, in response to changes in climate-induced thermoregulatory demands, thereby elucidating thermoregulatory mechanisms underlying bill size variation. We included a measure of anthropogenically-driven landscape change using data on conversion from primary vegetation cover at the same capture location and over the same 20-year period for each specimen. Landscape change, which has co-occurred with climate change, may alter the availability of food resources23, nest sites24 and thermal refuges25 as well as affect movement behaviour26,27. It was thus important to distinguish between these potential coincident drivers, although we had no directional a priori expectations for landscape change influencing bill size.

With respect to climate we predicted that:

Bill size, relative to body size, will vary non-linearly with increasing exposure to hot extremes, defined as increases in the frequencies of days with thermal maxima ≥35 °C (Δdays ≥35 °C). Specifically, larger bills will be associated with warming summers, consistent with increased capacity for radiative heat loss. This effect will be more pronounced in dry (low summer precipitation) environments where the capacity for evaporative cooling (via panting) is limited due to the risk of lethal dehydration.

However, in hot climates (where ambient temperatures regularly exceed body temperature) that have experienced high rates of summer warming, the selection pressure acting on bill size will be reversed in favour of smaller bills because large bills will become a heat sink in such conditions.

Larger bill size, relative to body size, will be associated with higher rates of winter warming, defined as decreases in the frequencies of days with thermal minima <5 °C (Δdays <5 °C). Warmer winters reduce the advantage of smaller bills that conserve body heat.

Results

Widespread warming and landscape change

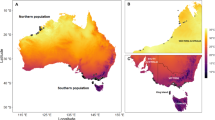

Using the Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s daily gridded spatial climate data (5 km2 resolution)28 and the Land-Use Harmonisation (LUH2) gridded land-use maps at 0.25 × 432 0.25 degree resolution we extracted location-specific climate data from the capture location of each of the 4119 specimens (from 57 species) in our morphometric data set, sampled across the temperate zone of Australia (Fig. 1). Based on characterisation of the change in climate at each site, we show that more than half of the individuals experienced an increase in hot extremes in summer (53.6%) and two-thirds experienced a decrease in cold extremes in winter (67.6%) over the previous 20 years (Fig. 2). About 87% of localities showed reductions in primary vegetation cover (Fig. 2).

Included are 4119 individuals from 57 species of Meliphagides sampled across the temperate zone (shown in yellow) as defined by the Köppen-Geiger climate classification59. The dots are coloured according to the collection year, and dot size represents the bill size of individuals relative to their body size for visual comparison. Boundaries of IBRA regions are shown in grey.

Bill size and warming summers

We employed phylogenetically controlled generalised linear mixed models (using MCMCglmm) to test for the effects on bill size of changing climate over time. The summer extreme model with lowest AICc included effects of Δdays ≥35 °C in interaction with mean maximum summer temperature (Tmax) and summer precipitation on bill size (Table 1). The interaction between Δdays ≥35 °C and summer precipitation was significant, with larger bills associated with warming dry environments where precipitation was <120 mm (Fig. 3a, b; Table 2).

a, b illustrating model predictions for relationship between bill size and Δdays ≥35 °C in interaction with summer rainfall; c, d bill size and Δdays ≥35 °C in interaction with mean maximum summer temperature; e, f bill size and Δdays < 5 °C in interaction with rate of change in primary cover (km2) across 57 species. Regression lines show predicted bill size response to the range of values between the 2nd and 98th percentiles of observed climate values of interacting variables. Black dashed line in (b) shows amount of rainfall below which the birds responded to summer warming by increasing bill size; d mean maximum summer temperature above which bill size starts to decline with increase in rate of summer warming. The y-axis has been truncated to enable visualisation of model predictions. (Supplementary Material Fig. S2 shows responses to the full range of values of variables along the x-axis and includes all data points).

The interaction between Δdays ≥35 °C and Tmax was marginally significant (pMCMC = 0.054), indicating a trend toward declining bill size in environments experiencing higher rates of summer warming and where Tmax was already high (Table 2, Fig. 2c). Conversely, larger bills were associated with higher rates of summer warming, but only in cooler environments where Tmax was less than 28 °C, otherwise high rates of warming were associated with smaller bill sizes (Fig. 2d).

We found no evidence for an effect of Δprimary land cover, either as a main effect or in interaction with climate variables, as including these terms did not improve the model [m3], Table 1).

Diet can be an important factor influencing the way birds respond to high temperatures because foods differ in water content29; accordingly, we controlled for feeding guild in our analyses. Although nectarivores had larger bills than insectivores, interactions between feeding guild and climate variables did not improve the model, suggesting that there is no detectable difference in responses to climate warming between the two feeding guilds (m5; Table 1).

Bill size and warming winters

The model [m4] with Δdays < 5 °C, its interactions with mean minimum winter temperature, winter precipitation and Δprimary cover showed the lowest AICc value among winter extreme models (Table 1). However, m4 was only marginally better at predicting the data than was m2, with only a small improvement in AIC (AICc = −1.901). This indicates weak support for landscape change as a primary driver of bill size variation, reflected in the non-significant main effect for Δprimary cover (Table 2).

There was a trend toward larger bills in environments that had experienced higher rates of winter warming (fewer cold extremes) (Δdays < 5 °C, Table 2). Moreover, this effect of winter warming was more pronounced in areas with greater reductions in primary land cover, as indicated by the significant interaction between Δdays < 5 °C and Δprimary cover (Table 2, Fig. 3e, f). Bill size was also associated with mean minimum winter temperature (Tmin) with larger bills in environments with higher Tmin.

Discussion

We investigated whether recent rapid changes in climate were associated with changes in bill morphology across a large and diverse radiation of Australasian passerines, Meliphagides. We found that rapid rates of warming over the previous 20 years – involving changes in the frequencies of climate extremes in summer and to a lesser extent in winter – were associated with bill size variation in accordance with the bill’s role in heat exchange and thermoregulation. We found little support for landscape change as a primary driver of bill size variation, although the effects of winter extremes were more pronounced in regions with greater loss of primary land cover. Our results are robust to the inclusion of the correlated effects of mean winter and mean summer temperatures, are based on comprehensive specimen sampling and match climate and morphology at appropriate temporal and spatial scales.

Our study provides broadscale evidence, across multiple species and over large geographic areas, that changing climate is driving changes in avian bill size over time and this result is consistent with changing thermoregulatory demands. The extent and direction (increase/decrease) of bill size responses varied with the location-specific nature of climate change and given the pre-existing climate regime to which species were adapted. This suggests that birds are tracking climate change across time via shifts in bill morphology. Observed reversals in the direction of size change were associated with particular temperature thresholds, as predicted both broadly13 and based on detailed spatial analysis of this same group of birds21. Thus, responses were not consistent across species or even populations of the same species yet were consistent with thermoregulatory predictions.

Two previous studies that tested for climate-related, temporal changes in bill size, focussed primarily on evaluating mean change in bill size over time, and were limited in their capacity to test underlying causes. Van Gils et al.30 reported a decline in mean bill length over 33 years in migratory red knots (Calidris canutus canutus) and this was likely the result of a trophic mismatch between predator and prey. Campbell-Tennant et al.31 reported mean increases in the bill size of four parrot species over a century in association with rising mean maximum summer temperatures across each species’ range. They attributed the pattern to multiple drivers, not limited to changing thermoregulatory demands. Unlike these previous reports, our study did not attempt to define an overall direction (increase/decrease) and mean value of bill size change across time but was designed to test whether bills track climate change through time because of changing thermoregulatory pressures. Our study is unique in relating bill morphology to rates of change in seasonal climate extremes which mediate the effects of climate on viability. Such studies are rare, and this lack of knowledge limits our ability to project population trends in coming decades and adapt conservation initiatives accordingly32.

We found little support for landscape change as a primary driver of bill size variation. In summer, the best model for the effects of summer extremes on bill size did not include changes in primary vegetation cover. In winter, including changes in primary cover produced a model that was marginally better at predicting the data, but the improvement was so small that it could occur by chance. It seems unlikely that changes in primary cover might underlie broadscale, morphological change at a continental level because land use change is spatially highly variable in its effects on the resources that birds rely on, although marked effects may be apparent at smaller spatial scales (source data for primary land conversions were available at coarser spatial and temporal resolutions than climate and specimen data). Nevertheless, land use change will inevitably affect traits that are linked to fitness and can interact with climate as shown here (see below) and elsewhere33. We suggest that the effects of landscape change may become more important in future decades as both climate and landscape change compound.

We found no differences between dietary guilds (nectarivores and insectivores) in responses to changing summer or winter extremes. Diet is an important factor influencing the way birds respond to high temperatures because foods differ in water content, potentially making nectarivores more vulnerable to rising temperatures29, being dependent on surface water to process diets high in sugar34,35. By contrast, insectivores drink infrequently, if at all, instead relying on water from their prey36, hence the suggestion that drinkers could be more vulnerable to mortality in hot conditions when surface water is unavailable36,37. One reason we may not have observed differences between guilds relates to the varying mobility of honeyeaters which comprise all the nectarivore species in our dataset. Most honeyeaters in our study are partial migrants (i.e., some populations are nomadic, some are sedentary while others consist of individuals that are nomadic or sedentary), while all insectivorous species we included are sedentary. Locally nomadic honeyeaters may have been able to avoid temperature extremes, and accordingly selection pressures acting on bill morphology might be minimised for nectarivores, thereby masking the influence of dietary guild.

The consequences for fitness of increasing frequencies of hot extremes are better understood than are reductions in cold extremes, given recent attention on biodiversity loss in arid and semi-arid desert ecosystems where high temperatures are already close to thermal limits. Heat waves can cause mass mortality events38,39,40 when animals succumb to heat stress as environmental temperatures exceed lethal limits; body temperatures of about 46 °C are lethal in birds41. A recent demographic study quantified patterns of adult survival for two bird communities in south-eastern Australia as a function of exposure to temperature extremes, using data from 37 species that had been the subject of continuous ringing programmes over 30 years42. Survival probability declined strongly with increasing exposure to days >38 °C with temperature extremes explaining 43% of temporal variation in survival among years. Given recent increases in the frequency, intensity and duration of extreme heat events43 we expected strong selection on the bill in its role in heat exchange, even over a 20-year period of exposure to changing climate.

Subasinghe et al.21 showed that bill size responses to high summer temperatures were non-linear, using the same dataset as the present study, albeit encompassing 79 species. Their study focussed on bill size variation across geographic space, not over time, and found a positive association between bill size and increasing frequency of days >35 °C, but only in dry environments where summer rainfall was <100 mm. They attributed this pattern to the adaptive advantage of larger bills in hot, arid environments where use of evaporative cooling is constrained due to limited water availability (see 13).

Our results of bill size variation across time are consistent with those observed across space and provide support for the thermoregulatory hypotheses21. We show that the same rate of warming in summer had different effects in dry versus wet environments. Larger bills were associated with increases in the frequencies of days with maxima ≥35 °C in environments where precipitation was <120 mm, where the advantage of non-evaporative, radiative cooling is expected to be high. Further, we show that in environments where mean maximum summer temperatures were already high, exceeding 28 °C, higher rates of summer warming tended to be associated with smaller bills instead of larger. Although this result was relatively weak (a statistical trend, pMCMC = 0.054) we suspect it underestimates the true effects of rising summer temperatures because our dataset comprise specimens collected before the series of hottest summer temperatures on record began in 201644.

Exposure to cold extremes can impose thermoregulatory and energetic challenges for birds, although it is uncertain how birds will respond to reductions in cold extremes that are expected to be beneficial for fitness as the climate warms. Cold stress and energetic constraints can drive reductions in both survival and reproduction and evidence for such effects is widespread45 including in Australian birds42. Thus, individuals with morphological traits that reduce fitness costs should have a selective advantage. Indeed, recent work on Meliphagides demonstrates that smaller bills are associated with colder climates across space, an adaptation which is likely to aid heat conservation, reflecting the role of the bill in heat exchange and thermoregulation21,22 Here we report, conversely and as predicted, a trend toward larger bill sizes in environments that have experienced higher rates of winter warming, defined as a decline in the frequencies of cold days <5 °C, although the effect was relatively weak (a statistical trend pMCMC=0.058). This response is consistent with a relaxation in selection pressure for smaller bills that reduce heat loss in cold conditions.

Differences in the nature of bill size responses that we observed in winter and summer suggest that it is rising summer temperatures that impose the most acute pressure, driving an increase in selection pressure rather than a relaxation. Our results are consistent with an earlier study of this same radiation of birds that found that structural body size is also tracking climate change and is likely the result of changing selection pressures46. We suspect that changes in morphological traits linked to heat exchange and thermoregulation will become more pronounced as seasonal climate extremes become more frequent, intense and sustained.

We provide critical evidence, across multiple species, that contemporary climate change is driving changes in avian bill size as thermoregulatory demands vary. Our study suggests that birds are tracking climate change across time via morphological shifts, and that such shifts are likely to be widespread given the spatial, phylogenetic and ecological scale of our study. Given the short timeframe of changing climate we considered, just 20 years, together with evidence that changing thermoregulatory demands are likely to underlie bill size variation, our study highlights the ecological significance of bill morphology in helping to mediate the effects of climate on viability. Three mechanisms are likely to underlie the climate-driven changes in bill size we observed: (1) increased selection for larger bills that maximise resistance to dehydration in dry climates experiencing warming summers; (2) increased selection against larger bills to minimise heat gain in already hot climates experiencing warming summers; 3) reduced selection pressure for smaller bills that maximise heat retention in climates experiencing warming winters. A critical question for future investigation is the degree to which these and other adaptations facilitate species’ persistence.

Materials and methods

Study species

We used data from 57 species from the infraorder Meliphagides inhabiting, but not confined to, the temperate zone of Australia for this study (Supplementary Data 1). Meliphagides is the largest radiation of Australian passerines (formerly known as Meliphagoidea) consisting of a diverse range of species from five families and some 276 species of which 145 are Australian; they comprise almost one-third of Australia’s passerines: fairy-wrens and grasswrens, honeyeaters, thornbills, gerygones and allies, pardalotes and bristlebirds. The group displays great diversity in life history, ecology and morphology, spanning a wide range of body sizes (6–260 g), bill sizes (bill surface area ranged between 18.11 mm2 in the weebill Smicrornis brevirostris and 508.18 mm2 in the blue-faced honeyeater Entomyzon cyanotis) and climatic regions (from desert to tropics), and comprise both nectarivores and insectivores. Together with several well-resolved, species-level phylogenies47,48, they make an ideal group for investigating responses to environmental change.

The sampling strategy for the dataset used in this study is described in Gardner et al.46 and in Subasinghe et al.21. In brief, we selected species that are relatively well represented in museum collections so that we could adequately sample across space (the distribution of each species) and over time (the past ca. 79 years when the climate has been changing rapidly). This is an important part of the study design. The large sample sizes are necessary to test our hypotheses because they involve non-linear responses and interactions among climate variables as is predicted by thermal physiology.

Data collection

Bird data

We collected bill measurements (bill length, width and depth) from 4119 museum specimens captured between 1956 and 2015. We chose adult individuals, excluded known juveniles and immatures based on skull ossification recorded during specimen preparation and available from the associated metadata. Full details of the collections used and measurements follow Subasinghe et al.21. In brief, bill length was measured as the distance from the feathering at the base of the upper mandible to the bill tip; bill width was measured from the posterior edge of the nares on one side of the bill to the same on the other side; and bill depth from the upper mandible to the lower mandible at the posterior edge of the nares at right angles to the tomia. Bill surface area was then estimated using the following formula11,14.

where, BL is the bill length; BW is the bill width; BD is the depth.

Wing length, measured as length of the flattened wing chord from the carpal joint to the tip of the longest primary feather, was used as a proxy for structural body size and obtained for most specimens from Gardner et al.46; 52 specimens housed in South Australian Museums were measured later in 2018 by KS and Jesse Smith. Sex and capture information (latitude, longitude and date of capture) for each specimen were obtained from Gardner et al.46 and the Atlas of Living Australia database (https://www.ala.org.au/) and feeding guild was classified based on primary source of food (nectarivores and insectivores) following Subasinghe et al.21.

Climate data

We used the Australian Bureau of Meteorology’s daily gridded spatial climate data at a resolution of 5 km2 to extract location-specific climate data for 20 years prior to the capture date of each specimen (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/austmaps/metadata-daily-temperature.shtml; http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/climatology/daily-rainfall-metadata.shtml28). We assumed that temporally-resolved climate data over 20 years would provide a better estimate for the rate of change compared to estimates using shorter timescales (e.g., 5 years) which are highly likely to be impacted by climate variability and stochasticity. We calculated the total number of extreme days with daily maxima ≥35 °C for each summer (December, January and February) and daily minima <5 °C for each winter (June, July and August) for a period of 20 years for the collection location for each specimen. Temperature thresholds (i.e. ≥35 °C, <5 °C) were chosen as these are associated with variation in bill size across space21. Then, we estimated the rate of change in the number of extreme summer days (Δdays ≥35 °C) and extreme winter days (Δdays < 5 °C) for the 20 years prior to date of collection of each specimen, by fitting a simple linear model between number of days and year using the lm function in R. We found no significant improvement in model strength, in terms of AIC values, when compared to an equivalent non-linear model. Further, we calculated the mean maximum summer temperature (by averaging maximum daily temperatures of summer months) and mean minimum winter temperature (by averaging the minimum daily temperature of winter months) over the 20-year period. Likewise, we calculated the mean total precipitation for both summer and winter seasons and mean vapour pressure for summer from the monthly data.

Non-climatic environmental data

We used Land-Use Harmonisation (LUH2) gridded land-use maps49,50 developed for use in global Earth System Models to extract location specific land cover information at 0.25 × 0.25 degree resolution for each of the 20 years preceding capture year. LUH2 provides information annually between 850 to 2100 for 10 land use classes, one of which is primary land defined as natural vegetation (either forest or non-forest) that has never been impacted by human activities (e.g., agriculture or wood harvesting). We extracted the proportion of primary forest and the proportion of primary non-forest cover for every location and estimated the proportion of total primary cover within the grid cell. Then, the rate of change in primary cover (Δprimary cover) was calculated to show the transformation of natural cover in the landscape by fitting a simple linear model against year as described earlier for temperature extremes.

We gathered data on IBRA7 (classification of Australian ecoregions known as bioregions51, corresponding to capture locations, which define 85 geographically distinct regions based on similarity in climate, geology, landforms, and vegetation52 relevant to this study. The total area of the study region (Australian temperate zone) is 21118 km2, based on the Köppen climate classification and the area from which specimens were sampled is 17925 km2 (area based on the number of 25 km2 grid cells).

Statistics and reproducibility

We investigated the association between bill size and the rate of change in climate extremes (Δdays ≥35 °C, Δdays <5 °C) using phylogenetically controlled generalised linear mixed models. Analysis was carried out using MCMCglmm in R version 4.0.353. We downloaded 1000 trees with the “Hackett backbone”54 using the Global Phylogeny of Birds website (www.birdtree.org)55 and produced a majority rule consensus phylogeny using the consensus function of the ape package in R56. We used inverseA function in MCMCglmm package to convert the tree into a relatedness matrix for incorporating into the models to control for phylogeny.

To test the association between bill size and summer warming, we fitted a model [m1] with bill size as the response with rate of change in days ≥35 °C (Δdays ≥35 °C), mean maximum summer temperature, summer precipitation and interaction terms between Δdays ≥35 °C with mean maximum summer temperature and summer precipitation as explanatory variables while controlling for body size (wing length), feeding guild (nectarivore or insectivore), sex, season and year of capture as fixed effects, and IBRA region, species and year of capture again as random intercepts using using MCMCglmm in R. Several covariates were included in all analyses: body size was included as we are only interested in bill size relative to body size; feeding guild to account for any differences in bill size between guilds; sex to account for sexual dimorphism in bill size and season to control for differences in the rate of bill wear caused by seasonal differences in foraging behaviour57. We included year of capture as a fixed term to account for temporal trends in bill size not particularly related to climate change and, as a random variable to account for differences in sample sizes among collection years. IBRA region was included to account for similarities in morphology among individuals from the same geographic regions, and species, to account for the inter-specific differences in bill size and effects of repeated sampling within species20.

To test the associations between bill size and winter warming, we fitted a separate model [m2] with bill size as the response, with rate of change in days <5 °C (Δdays <5 °C), mean minimum winter temperature, winter precipitation, interaction terms between days <5 °C with mean minimum winter temperature and winter precipitation as explanatory variables. We included all control variables that were in m1 in this model.

Then, we fitted two separate models, [m3] and [m4], adding change in primary cover and an interaction between change in extreme days and change in primary cover as explanatory variables to m1 and m2 respectively. The structure of m3 is shown below.

Finally, to explore whether the feeding guild has an impact on bill size response to climate warming, we ran a separate model [m5] adding three-way interactions between (1) feeding guild, Δdays ≥35 °C and mean maximum summer temperature and (2) feeding guild, Δdays ≥35 °C and summer precipitation, to the summer extreme model that had lowest AICc (from m1 and m3).

In all models, bill size and structural body size were log transformed to achieve normality of residuals; we ensured that response and predictor variables of interest were back-transformed when plotting the effects. They were then z-score standardised along with all climate and landscape variables before fitting models. The year of capture (fixed effect) in all models was centred on its mean which is 1985. Models were performed with 2,020,000 iterations with a burn-in of 20,000 and thinning interval of 2000, with weakly informative priors. We applied default broad Gaussian priors for fixed effects and inverse-Wishart priors, with parameter V = 1 and nu = 0.002, for random effects. From the model sets described above, the best model with the lowest AICc was selected, and the parameter estimates with 95% credible intervals were extracted. The correlation matrix of climate variables is given in Supplementary Material Fig. S1. We calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to test for multicollinearity among predictors in each model; all values are below 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity (see Table S1).

No data were excluded from the analyses. Importantly, we did not reformulate our hypotheses, post-hoc, or re-run the analyses. All relevant climate variables and interaction terms required to test the predictions were included in two separate models representing winter and summer conditions. We did not use a model selection approach to identify which set of climate variables best predicts the response. Rather, we used the AICc values to identify whether the additional variables related to land-use change (i.e., the conversion from primary cover) and feeding guild, improved the strength of models that included only climate variables. We used the estimates of the model with the highest AICc to explore the shapes of responses and the significance of predictors. We assessed the significance of predictors using the credible intervals from the MCMCglmm model output. We can consider that a fixed effect is significant if the credible intervals do not span zero.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

The code is available at https://figshare.com/s/db16260cb8ab3e48aa70.

References

Parmesan, C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37, 637–669 (2006).

Thomas, C. D. Climate, climate change and range boundaries. Divers. Distrib. 16, 488–495 (2010).

Iler, A. M., CaraDonna, P. J., Forrest, J. R. K. & Post, E. Demographic consequences of phenological shifts in response to climate change. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 52, 221–245 (2021).

Millien, V., Lyons, S. K., Smith, F. A., Wilson, A. B. & Yom-Tov, Y. Ecotypic variation in the context of global climate change: revisiting the rules. Ecol. Lett. 9, 853–869 (2006).

Gardner, J. L., Peters, A., Kearney, M. R., Joseph, L. & Heinsohn, R. Declining body size: a third universal response to warming?. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 285–291 (2011).

Ryding, S., Klaassen, M., Tattersall, G. J., Gardner, J. L. & Symonds, M. R. E. Shape-shifting: changing animal morphologies as a response to climatic warming. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 1036–1048 (2021).

Paniw, M. et al. The myriad of complex demographic responses of terrestrial mammals to climate change and gaps of knowledge: a global analysis. J. Anim. Ecol. 90, 1398–1407 (2021).

Tian, L. & Benton, M. J. Predicting biotic responses to future climate warming with classic ecogeographic rules. Curr. Biol. 30, R744–R749 (2020).

Tattersall, G. J., Arnaout, B. & Symonds, M. R. E. The evolution of the avian bill as a thermoregulatory organ. Biol. Rev. 92, 1630–1656 (2017).

Tattersall, G. J., Andrade, D. V. & Abe, A. S. Heat exchange from the Toucan bill reveals a controllable vascular thermal radiator. Science 325, 468–470 (2009).

Hagan, A. A. & Heath, J. E. Regulation of heat loss in the duck by vasomotion in the bill. J. Therm. Biol. 5, 95–101 (1980).

van de Ven, T. M. F. N., Martin, R. O., Vink, T. J. F., McKechnie, A. E. & Cunningham, S. J. Regulation of heat exchange across the hornbill beak: functional similarities with toucans?. PLoS ONE 11, e0154768 (2016).

Greenberg, R., Cadena, V., Danner, R. M. & Tattersall, G. J. Heat loss may explain bill size differences between birds occupying different habitats. PLoS ONE 7, e40933 (2012).

Greenberg, R. & Danner, R. M. The influence of the California marine layer on bill size in a generalist songbird. Evolution 66, 3825–3835 (2012).

Dawson, W. R. Evaporative losses of water by birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Comp. Physiol. 71, 495–509 (1982).

Bartholomew, G. A. & Cade, T. J. The water economy of land birds. Auk 80, 504–539 (1963).

Scholander, P. F., Hock, R., Walters, V., Johnson, F. & Irving, L. Heat regulation in some arctic and tropical mammals and birds. Biol. Bull. 99, 237–258 (1950).

James, F. C. Geographic size variation in birds and its relationship to climate. Ecology 1, 365–390 (1970).

Marder, J. & Arad, Z. Panting and acid-base regulation in heat stressed birds. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 94, 395–400 (1989).

Gardner, J. L. et al. Spatial variation in avian bill size is associated with humidity in summer among Australian passerines. Clim. Change Resp. 3, 11 (2016).

Subasinghe, K., et al. Spatial variation in avian bill size is associated with temperature extremes in a major radiation of Australian passerines. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 291, 20232480 (2024).

Friedman, N. R., Harmáčková, L., Economo, E. P. & Remeš, V. Smaller beaks for colder winters: thermoregulation drives beak size evolution in Australasian songbirds. Evolution 71, 2120–2129 (2017).

Hallmann, C. A. et al. More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas. PLoS ONE 12, e0185809 (2017).

Reynolds, S. J., Ibáñez-Álamo, J. D., Sumasgutner, P. & Mainwaring, M. C. Urbanisation and nest building in birds: a review of threats and opportunities. J. Ornithol. 160, 841–860 (2019).

Tomecek, J. M., Pierce, B. L., Reyna, K. S. & Peterson, M. J. Inadequate thermal refuge constrains landscape habitability for a grassland bird species. PeerJ 5, e3709–e3709 (2017).

Gillies, C. S., Beyer, H. L. & St. Clair, C. C. Finescale movement decisions of tropical forest birds in a fragmented landscape. Ecol. Appl. 21, 944–954 (2011).

Knowlton, J. L. et al. Movements of four native Hawaiian birds across a naturally fragmented landscape. J. Avian Biol. 48, 921–931 (2017).

D. A. Jones, W. Wang, R. Fawcett. High-quality spatial climate data-sets for Australia. Aust. Meteorol. Oceanogr. J. 58, 233 (2009).

Albright, T. P. et al. Mapping evaporative water loss in desert passerines reveals an expanding threat of lethal dehydration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2283–2288 (2017).

van Gils, J. A. et al. Body shrinkage due to Arctic warming reduces red knot fitness in tropical wintering range. Science 352, 819–821 (2016).

Campbell-Tennant, D. J. E., Gardner, J. L., Kearney, M. R. & Symonds, M. R. E. Climate-related spatial and temporal variation in bill morphology over the past century in Australian parrots. J. Biogeogr. 42, 1163–1175 (2015).

Prober, S. M., Doerr, V. A. J., Broadhurst, L. M., Williams, K. J. & Dickson, F. Shifting the conservation paradigm - a synthesis of options for renovating nature under climate change. Ecol. Monogr. 89, e01333:01331–01323 (2019).

Guo, F., Lenoir, J. & Bonebrake, T. C. Land-use change interacts with climate to determine elevational species redistribution. Nat. Commun. 9, 1315 (2018).

Fisher, C. D., Lindgren, E. & Dawson, W. R. Drinking patterns and behavior of Australian desert birds in relation to their ecology and abundance. Condor 74, 111–136 (1972).

Fleming, P. A., Xie, S., Napier, K., McWhorter, T. J. & Nicolson, S. W. Nectar concentration affects sugar preferences in two Australian honeyeaters and a lorikeet. Funct. Ecol. 22, 599–605 (2008).

Smit, B. et al. Behavioural responses to heat in desert birds: implications for predicting vulnerability to climate warming. Clim. Chang. Responses 3, 9 (2016).

Riddell, E. A., Iknayan, K. J., Wolf, B. O., Sinervo, B. & Beissinger, S. R. Cooling requirements fueled the collapse of a desert bird community from climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21609–21615 (2019).

Welbergen, J. A. et al. Climate change and the effects of temperature extremes on Australian flying foxes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 275, 419–425 (2008).

Saunders, D. A., Mawson, P. & Dawson, R. The impact of two extreme weather events and other causes of death on Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo: a promise of things to come for a threatened species?. Pac. Conserv. Biol. 17, 141–148 (2011).

McKechnie, A. E., Rushworth, I. A., Myburgh, F. & Cunningham, S. J. Mortality among birds and bats during an extreme heat event in eastern South Africa. Austral Ecol. 46, 687–691 (2021).

Boyles, J. G. et al. Adaptive thermoregulation in endotherms may alter responses to climate change. Integr. Comp. Biol. 51, 676–690 (2011).

Gardner, J. L., Clayton, M., Allen, R., Stein, J. & Bonnet, T. The effects of temperature extremes on survival in two semi-arid Australian bird communities over three decades, with projections to 2104. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 31, 2498–2509 (2022).

Stillman, J. H. Heat waves, the new normal: summertime temperature extremes will impact animals, ecosystems, and human communities. Physiol 34, 86–100 (2019).

CSIRO and Australian Bureau of Meteorology, State of the Climate 2020. www.bom.gov.au/state-of-the-climate/ | www.csiro.au/state-of-the-climate (2020).

Williams, C. M., Henry, H. A. L. & Sinclair, B. J. Cold truths: how winter drives responses of terrestrial organisms to climate change. Biol. Rev. 90, 214–235 (2014).

Gardner, J. L. et al. Australian songbird body size tracks climate variation: 82 species over 50 years. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 286, 20192258 (2019).

Gardner, J. L., Trueman, J. W., Ebert, D., Joseph, L. & Magrath, R. D. Phylogeny and evolution of the Meliphagoidea, the largest radiation of Australasian songbirds. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 55, 1087–1102 (2010).

Marki, P. Z. et al. Supermatrix phylogeny and biogeography of the Australasian Meliphagides radiation (Aves: Passeriformes). Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 107, 516–529 (2017).

Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of global land use change and management for the period 850–2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5425–5464 (2020).

Chini, L. et al. Land-use harmonization datasets for annual global carbon budgets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4175–4189 (2021).

Thackway, R. & Cresswell, I. D. (Eds). An interim biogeographic regionalisation for Australia: a framework for setting priorities in the national reserves system cooperative program, version 4.0. Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Canberra (1995).

SEWPaC, Interim biogeographic regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Australian Government Department of Sustainability Environment Water Population and Communities, 10, 813567 https://www.environment.gov.au/land/nrs/science/ibra#ibra (2012).

Hadfield J. D. MCMC Generalised Linear Mixed Models. R package version 2.27. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MCMCglmm/index.html (2019).

Hackett, S. J. et al. Phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history. Science 320, 1763–1768 (2008).

Jetz, W., Thomas, G. H., Joy, J. B., Hartmann, K. & Mooers, A. O. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature 491, 444–448 (2012).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. Ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2019).

Matthysen, E. Season variation in bill morphology of nuthatches Sitta europaea: dietary adaptations or consequences?. Ardea 77, 117–125 (1989).

Hadfield, J. D., Heap, E. A., Bayer, F., Mittell, E. A. & Crouch, N. M. A. Intraclutch differences in egg characteristics mitigate the consequences of age-related hierarchies in a wild passerine. Evolution 67, 2688–2700 (2013).

Köppen W. Das geographischesystem der Klimate. in Handbuch der klimatologie, Vol. 1, Part C (eds W. Köppen, R. Geiger) 1–44 (1936).

Acknowledgements

We thank staff at The Australian National Wildlife Collection, Australian Museum, Museum Victoria, Queensland Museum, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, South Australian Museum, Western Australian Museum, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery for providing access to specimens, Jesse Smith for assistance measuring specimens and Matthew Symonds and Timothée Bonnet for statistical advice. This work was partly funded by The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (PHD17-27) and the Recent Ecological Change in Australia (RECA) project through the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW). K.S. was supported by ANU HDR Fee Merit Scholarship, University Research Scholarship and CSIRO top-up scholarship (PHD17-27); J.L.G. by a Future Fellowship from the Australian Research Council [FT150100139]; K.J.W., S.M.P., and C.W. through DCCEEW funding on the RECA project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, visualisation, writing original draft; S.M.P.: funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing; K.J.W.: funding acquisition, project administration, resources, writing—review and editing; C.W.: data curation; J.L.G.: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—drafting, review and editing. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Borja Figueirido and Dario Ummarino. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Subasinghe, K., Prober, S.M., Williams, K.J. et al. Australian birds track climate warming over decades via shifts in bill morphology. Commun Biol 8, 633 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08042-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08042-7