Abstract

Multiplexed imaging techniques require identifying different cell types in the tissue. To utilize their potential for cellular and molecular analysis, high throughput and accurate analytical approaches are needed in parsing vast amounts of data, particularly in clinical settings. Nuclear segmentation errors propagate in all downstream steps of cell phenotyping and single-cell spatial analyses. Here, we benchmark and compare the nuclear segmentation tools commonly used in multiplexed immunofluorescence data by evaluating their performance across 7 tissue types encompassing ~20,000 labeled nuclei from human tissue samples. Pre-trained deep learning models outperform classical nuclear segmentation algorithms. Overall, Mesmer is recommended as it exhibits the highest nuclear segmentation accuracy with 0.67 F1-score at an IoU threshold of 0.5 on our composite dataset. Pre-trained StarDist model is recommended in case of limited computational resources, providing ~12x run time improvement with CPU compute and ~4x improvement with the GPU compute over Mesmer, but it struggles in dense nuclear regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiplexed immunofluorescence (mIF) imaging improves on conventional immunohistochemistry (IHC) as a diagnostic tool to facilitate analysis of tissue composition, spatial biomarker distribution, and cell-cell interactions1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, allowing for correlation with diagnostic and prognostic outcomes. There is also the added benefit of applying multiple markers on a single section when tissue samples are scarce13. Cell segmentation is an integral process in mIF workflows14,15 following which spatial molecular analysis is conducted16,17. First, individual nuclei are segmented within a tissue section. This is followed by either a fixed pixel expansion around the nuclei or the use of cytoplasm/cell membrane markers for subsequent whole-cell segmentation.

Classical nuclear segmentation techniques involving thresholding (the most common technique being Otsu thresholding18), morphological operations, and watershed algorithms19,20,21 are easier to implement and well-known to the research and clinical community but can be limiting in the accuracy they provide22 They also involve a large number of user-inputted parameters that vary from algorithm to algorithm making standardized performance difficult. Proprietary software (e.g., inForm® (Akoya Biosciences) or HALO® (Indica Labs)), commonly being used in clinical settings offer a seamless, graphical user interface to implement the entire pipeline of cell segmentation and phenotyping in one platform. However, they are costly and do not provide much room for customization. Deep learning-based open-source algorithms23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 are highly accurate, customizable, and more generalizable but can be non-intuitive to implement without computational expertise. For any given spatial analysis task, nuclear segmentation is an important component of the analytical pipeline and can have significant impacts on the biological insights drawn from the dataset, particularly if cells are erroneously counted or missed at the beginning of the analysis.

Any errors during nuclear segmentation can propagate into downstream analysis steps such as cell phenotyping, immune profiling, and prognosis prediction. In part, it is difficult to achieve accurate and reliable nuclear segmentation due to differences in nuclear size, shape, and density (the number of nuclei per unit area of tissue) across tissue types, imaging conditions of different microscopes, and illumination differences within a whole slide image (WSI)23,34. Classical algorithms suffer from this as they generally require parameter tuning to optimize performance (labor and time-intensive, requires expertise, and operator-dependent results) due to these differences between WSIs or even between different fields within a WSI. Pre-trained deep learning models suffer because their training data only contains a subset of these differences and can tend to underperform when exposed to these alterations, which can often be improved upon by further re-training of these algorithms. It is especially challenging in crowded regions of tissue, where nuclei overlap, making it difficult to demarcate one from another24,35. The challenge of nuclear segmentation has been around for many years and continues to add unreliability to mIF workflows27,36.

Currently, there are no benchmarks in the field to quantitatively evaluate these algorithms for a given task making the mIF analytical pipeline subjective and qualitative. Therefore, it is crucial to be able to quantitatively evaluate the different nuclear segmentation algorithms37, and carefully choose the right platform for a given dataset and task.

In this study, we objectively compare the performance of commonly used nuclear segmentation algorithms/models on different datasets (spanning 7 human tissue types collected at different institutions and ~20,000 nuclei) and provide bounds on both their accuracy and computational efficiency. This provides an expectation for the upper bound of the accuracy of mIF workflows (e.g., single-cell spatial mapping and profiling) when using one of the algorithms discussed in this study. We provide recommendations as to the best algorithms/models to use when working with certain data types (e.g., tissue type, nuclear sparsity/density of the dataset) and constraints (e.g., GPU availability, and computation time). To do this, we curated multiple datasets of spectrally unmixed DAPI signal with paired ground truth nuclear annotations (Fig. 1A). A subset of the datasets was generated in-house (Fig. 1A(ii–vi)), and has been made publicly available via Zenodo repository 1330671438 for benchmark analysis of other algorithms/models not considered in this study, while the rest was obtained from an already publicly available dataset39. We quantitatively evaluated the in-built nuclear segmentation algorithms of GUI-based open-source platforms (Fiji21,40, CellProfiler41,42,43,44, and QuPath45), and one commercial piece of software with a proprietary nuclear segmentation algorithm (inForm® (Akoya Biosciences)) which utilize classical segmentation techniques (Fig. 1B, C). Similarly, we evaluated three pre-trained models of nuclear segmentation deep-learning models (Mesmer23, Cellpose29, and StarDist28) which we implemented in Python (Fig. 1B, C). Largely, this study provides an expectation for and compares (using quantitative metrics, qualitative segmentation results, and two benchmark datasets) the performance of commonly available nuclear segmentation algorithms for use in the analysis of multiplexed immunofluorescence data of human tissue samples in translational workflows. Our work can be used as a guide to select the optimal nuclear segmentation platform given the type and nature of data along with open-source implementation of the chosen algorithm without the need for licensed software. Additionally, all codes and methods released through this manuscript can directly be translated to benchmark any other nuclear/cell segmentation algorithms on a new set of data.

A Nuclear segmentation is performed on spectrally unmixed DAPI signal. Two datasets were used in this study- in-house imaged DAPI ROIs (vi) for which binary ground truth nuclei masks were annotated (ii–v) and an external, publicly available dataset which was merged with our in-house dataset (vii) for evaluation of parameter-free deep learning algorithms with enhanced statistical power. B Deep learning algorithms (implemented in Python) and classical algorithms (implemented in various platforms with a GUI) were evaluated. C ROIs were sampled from the fields (which were sampled from WSIs). The segmentation predictions of the different algorithms on the sampled ROIs were compared with the ground truth nuclear masks to compute object-level quantitative metrics for comparison and benchmarking of nuclear segmentation performance. Scalebar in red A(i), C 100 μm, and A(ii–v) 10 μm.

Results

Deep learning generally outperforms classical algorithms with varied performance between tissue types

We investigated the quantitative performance of the seven nuclear segmentation tools averaged over the entire in-house dataset, consisting of thousands of nuclei across three tissue types. Figure 2A(i) shows the average performance along with a 95% confidence interval across all images (three tissue types combined) at an IoU threshold of 0.5. Figure 2A(ii) illustrates the performance of different platforms across a range of IoU threshold values, capturing the efficiency of platforms in localizing the boundaries of nuclei with the area under the curve measured and shown in Fig. 2A(iii). Overall, it is evident that the deep learning platforms (Cellpose, Mesmer, StarDist) perform better than the morphological platforms represented both by a higher F1-score at an IoU of 0.5 and by a higher area under the curve (AUC) across IoU thresholds. Based on the results of the quantitative evaluation of the nuclear segmentation platforms, it is safe to conclude that Fiji and CellProfiler are limited in their accuracy relative to the other platforms. Furthermore, of the tested morphological operations-based platforms, QuPath’s (a freely available source) in-built segmentation tool performs better or is similar to inForm®, which is expensive software to license. Cellpose consistently outperformed other platforms at IoU thresholds greater than 0.5 for our dataset.

A Evaluation results for the composite dataset, with results stratified by tissue type in B tonsil, C melanoma, and D breast. (i) Mean nuclear segmentation F1-score (averaged across the evaluation ROIs) at an intersection over union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 with error bars showing 95% confidence interval. The IoU threshold of 0.5 is the most lenient threshold required to ensure a maximum of one true positive predicted nucleus for each ground truth nucleus. (ii) Mean nuclear segmentation F1-score (averaged across the evaluation ROIs) at varying IoU thresholds. A higher IoU threshold results in a stricter condition for classifying a predicted nucleus as a true positive. (iii) The area under the curve (AUC) in (ii) for each segmentation algorithm. The AUC is an aggregate metric, a higher value of which indicates an algorithm’s ability to better segment nuclei on an object level (F1-score at low IoU thresholds) as well as accurately capturing nuclear morphology (F1-score at high IoU thresholds).

Next, we investigated the performance of segmentation platforms for each individual tissue type in our cohort (Fig. 2B–D). Again, deep learning platforms performed better. However, different models emerged as the best choice for each tissue type. For tonsil tissue, Cellpose outperforms other platforms and QuPath surpasses StarDist in segmentation F1-scores at all IoU thresholds as shown in Fig. 2B(ii). While Mesmer matches the performance of Cellpose at low IoU thresholds for the tonsil dataset, it loses accuracy at stricter/higher thresholds (Fig. 2B(ii)). We noticed that the tonsil samples had more non-specific staining as compared to the other samples making them hard to segment, while Cellpose still performed the segmentation task with high accuracy. For skin, Mesmer outperforms other platforms, however, StarDist performs better at stricter IoU thresholds (>0.75) as evident in Fig. 3C(i) and (ii). Mesmer also gives the best performance in breast tissue not only at an IoU threshold of 0.5 but across all IoU thresholds as evident in Fig. 2D. Cellpose didn’t show a similar level of robustness in segmentation as it showed with the tonsil dataset. We believe it is due to a preprocessing step where Cellpose linearly scales the raw pixel intensities such that the 1 and 99 percentiles correspond to 0 and 129. As a result, pixel intensity data with high variance and/or many outliers will cause Cellpose to perform poorly, as is observed with the breast data. Across all tissue types, the three deep learning models outperform the other morphological operations-based platforms. It is also evident that each platform handled touching nuclei, high or low nuclear density, varying nuclear sizes, and non-specific DAPI staining in intrinsically different ways as described in Table 1. Since the deep learning models have been trained on a large cohort of nuclei spanning different types of images, they are more agnostic to these variations, making them consistently top performers. A brief description of the overall principle of nuclear segmentation for five of the top-performing platforms and ease of implementation is described in Table 1.

Mean (averaged across 60 ROIs) with error bars showing 95% confidence interval of A F1-score, D precision, E recall, F Jaccard index are evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5. The IoU threshold of 0.5 is the most lenient threshold required to ensure a maximum of one true positive predicted nucleus for each ground truth nucleus. B Boxes show the median and quartiles of the F1-scores (evaluated at 0.5 IoU threshold) across the 60 evaluation ROIs and whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the inter-quartile range with outliers shown. C Mean F1-score (averaged across 60 ROIs) at varying IoU thresholds, with area under the curve shown. A higher IoU threshold results in a stricter condition for classifying a predicted nucleus as a true positive. G Nuclear prediction computation time for each algorithm using CPU and GPU. Boxes show the median and quartiles of the computation time (n = 27 fields) and whiskers extend up to 1.5 times the inter-quartile range with outliers shown.

Evaluation of performance on the composite merged dataset and stratified by tissue type

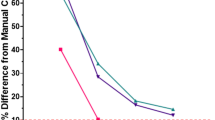

Since the three pre-trained deep learning models outperformed all other platforms across tissue types and IoU thresholds on our in-house benchmarking dataset, we benchmarked their performance on a large, publicly available dataset to achieve higher statistical power. This was efficiently carried out as the deep learning models are parameter-free (no manual optimization required) and our pipeline is batch-operable in Python. We utilized our pipeline to evaluate the performance on the merged dataset of ~20,000 nuclei (Fig. 3A–F), spanning 7 different tissue types. It is evident from Fig. 3A, C that at an IoU threshold of 0.5 and all IoU thresholds, Mesmer outperforms the other algorithms (mean F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold = 0.67, AUC = 0.55). Cellpose (mean F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold = 0.65, AUC = 0.53) was in between Mesmer and StarDist (mean F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold = 0.63, AUC = 0.51) for nuclear segmentation performance (Fig. 3A, C). Figure 3B also illustrates that Mesmer didn’t have any outliers on the box plot suggesting that its performance is consistent irrespective of the nature of the region of interest (ROI). However, Cellpose and StarDist exhibited extremely low performance on some ROIs as shown by their respective outlier points on the box plot.

Figure 4 shows the performance of the three pre-trained models on the individual tissue types using the F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold and the F1-score vs. IoU threshold AUC as the main metrics for evaluation. Mesmer had the highest performance for pancreas, skin, tongue, and breast while Cellpose had the best performance for tonsil and colon tissue types.

A Pancreas, B lung, C skin, D tonsil, E colon, F breast, and G tongue tissue type. (i) Mean F1-score (averaged across ROIs) evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5 with error bars showing 95% confidence interval. The IoU threshold of 0.5 is the most lenient threshold required to ensure a maximum of one true positive predicted nucleus for each ground truth nucleus. (ii) Mean F1-score (averaged across ROIs) at varying IoU thresholds, with area under the curve shown. A higher IoU threshold results in a stricter condition for classifying a predicted nucleus as a true positive.

StarDist accuracy drops in regions of high nuclear density

To investigate whether a model has different performance based on nuclear sparsity/density of a region, we split the merged dataset into groups by a cut-off based on the median (~278 nuclei/105 pixels), upper quartile (~368 nuclei/105 pixels) or lower quartile (~200 nuclei/105 pixels) nuclear density (Fig. 5). The StarDist model has reduced performance above the median nuclear density (Fig. 5C(i),(ii)) than below (Fig. 5B(i),(ii)) shown by the drop in mean F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold from 0.69 to 0.57 and drop in F1-AUC from 0.57 to 0.46. This difference is even more pronounced above the upper quartile nuclear density (Fig. 5D(i),(ii)) than below the lower quartile (Fig. 5A(i),(ii)) with the drop in mean F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold from 0.67 to 0.47 and drop in F1-AUC from 0.56 to 0.39. Another observation to note is that the performance of Cellpose is the most stable/consistent with varying densities even though the absolute performance mostly stays higher for Mesmer.

ROIs that have a nuclear density less than the lower quartile of the merged dataset (A) are regarded as sparse while ROIs that have a nuclear density more than the upper quartile (D) are regarded as dense. ROIs with nuclear density less than the median (B) and more than the median (C) are also analyzed. (i) Mean F1-score (averaged across ROIs) at varying IoU thresholds, with area under the curve shown. A higher IoU threshold results in a stricter condition for classifying a predicted nucleus as a true positive. Mean (averaged across ROIs) with error bars showing 95% confidence interval of (ii) F1-score, (iii) precision, (iv) recall, (v) Jaccard index are evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5. The IoU threshold of 0.5 is the most lenient threshold required to ensure a maximum of one true positive predicted nucleus for each ground truth nucleus.

Pre-trained models exhibit higher precision than recall with varying relative differences affecting performance

In almost all cases, all three pre-trained models exhibit a higher precision than recall (Figs. 5(iii),(iv) and 6(ii),(iii)). This means that the error in nuclear segmentation can be attributed to pre-trained models generally predicting more false negative nuclei (under-segmented or completely missed nuclei) rather than more false positive nuclei (over-segmented or falsely predicted nuclei). This is an interesting bias and one that is observed with all three pre-trained models.

A Pancreas, B lung, C skin, D tonsil, E colon, F breast, and G tongue tissue type. Mean (averaged across ROIs) with error bars showing 95% confidence interval of (i) F1-score, (ii) precision, (iii) recall, (iv) Jaccard index are evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5. The IoU threshold of 0.5 is the most lenient threshold required to ensure a maximum of one true positive predicted nucleus for each ground truth nucleus.

In addition to performing the best on the composite dataset, Mesmer also performed better than Cellpose and StarDist models (as measured by the F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold and the F1-score AUC) when stratified by the tissue type in pancreas (Fig. 6A), skin (Fig. 6C), breast (Fig. 6F), and tongue (Fig. 6G) tissue and in regions of low nuclear density (Fig. 5A). This is generally because Mesmer has the highest recall (sensitivity), especially when its precision is comparable to or lower than that of Cellpose and StarDist (where Cellpose and StarDist under-segment). A representative region of breast tissue and the performance of the three pre-trained models is shown in Fig. 7A.

A Breast tissue type and B tonsil tissue type with high nuclear density. (i) Spectrally unmixed mIF data has the (ii) DAPI channel extracted and (iii) ground truth nuclei annotated. The pre-trained models are applied to the DAPI channels to yield (iv) binary nuclear masks, which are (v) overlayed on the ground truth mask for comparison to visualize the model-derived differences in nuclear segmentation. The differences between the models in the (vi) recall and (vii) precision, which both constitute the F1-score are also visualized. All F1-score, precision, and recall metrics are evaluated at an IoU threshold of 0.5, and nuclei that have IoU lower than the threshold are included as false positives in the precision and false negatives in the recall calculation. Scalebar in yellow, 25 µm.

Cellpose performed better than Mesmer and StarDist models (as measured by F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold and the F1-score AUC) in tonsil (Fig. 6D) and colon (Fig. 6E) tissue types and in regions of extremely high nuclear density (Fig. 5D). This is usually because Cellpose has the highest precision, especially when its recall is comparable to or lower than that of Mesmer and StarDist (where Mesmer and StarDist over segment). A representative region of tonsil tissue (with high nuclear density) and this relative performance gain of Cellpose over Mesmer is shown in Fig. 7B.

Except for lung (Fig. 5B), StarDist performs worse than Mesmer and/or Cellpose models (as measured by the F1-score at 0.5 IoU threshold and the F1-score AUC) in all other tissue types. This is usually because StarDist has the lowest recall, especially when its precision is comparable to or higher than that of Mesmer and Cellpose (StarDist has a bias to under-segment). This can especially be seen with tonsil tissue (Fig. 6D) and in regions of high nuclear density (Fig. 5C, D). A representative region of tonsil tissue (with high nuclear density) and this relative performance drop of StarDist is shown in Fig. 7B.

Another quantitative metric reported in this study to compare the pre-trained models is the Jaccard index (Figs. 5(v) and 6(iv)). It can be seen from their computation formulae (Eqs. (2) and (5)) that the Jaccard index and F1-score are mathematically related. One of the metrics can be calculated simply by knowing the value of the other. While the Jaccard index is objectively a stricter metric (its value will always be lower than the F1-score), the relative differences between the three models have a conserved trend between the Jaccard index and F1-score (Figs. 5 and 6).

StarDist is the most computationally time efficient and Cellpose has the most reliance on GPU usage

Figure 3G shows the computation times for both CPU and GPU usage for the three pre-trained models on the external dataset, which consists of 27 fields sampled from 27 WSIs. One ROI (400 × 400 pixels) is sampled from each segmented field for performance evaluation. Five large fields from the in-house dataset were left out of this analysis because they were significantly larger than those in the external dataset which could confound the computational time analysis.

Figure 3G shows that the StarDist model has the lowest computation time for both GPU (~4x and ~15x shorter median run time than Mesmer and Cellpose respectively) and CPU (~12x and ~89x shorter median run time than Mesmer and Cellpose respectively). As such, StarDist is the recommended choice for nuclear segmentation tool for studies where computational resources are constrained, especially when the data does not contain overly crowded regions of nuclei where it tends to struggle with accuracy. It is worth noting that Cellpose sees the most improvement in processing time with ~12x shorter median run time for GPU over CPU usage. Mesmer’s computation time for both CPU and GPU is in between that of Cellpose and StarDist, with a high level of accuracy for most tissue types and nuclear density levels. As such, Mesmer is the recommended model for general-purpose nuclear segmentation use cases.

Discussion

In this study, we quantitatively evaluated the performance of seven nuclear segmentation tools by comparing their predictions with ground truth nuclear annotations. We performed comparative analyses between the seven segmentation tools on an ROI level. F1-scores were calculated for each tool in each ROI at varying IoU thresholds, in which hundreds of nuclei were compared in the predicted and ground truth nuclear masks for the ROI. Based on the quantitative evaluation results on the in-house dataset, it is safe to conclude that Fiji and CellProfiler are limited in their accuracy relative to the other platforms. Further, we noticed that inForm® and QuPath performed quite well but, in most cases, were outperformed by newer deep-learning platforms.

Even though deep learning platforms performed the best across datasets, they are only slowly being adopted in clinical settings and molecular labs. Reasons for this barrier to applying deep learning models in clinical practice include their non-intuitive implementation and a lack of interpretability, reliability, and transparency. However, studies are being conducted to improve the interpretability aspect46. Another reason for the barrier to deep learning clinical application is the usual need for fine-tuning models on datasets. This could be because the tissue type is different from the dataset the models were originally trained on and/or because differences in institutions and protocols can cause variability in stain quality and appearance47. Deep learning models like Cellpose and StarDist allow the training of custom models on user-obtained data for even better segmentation results28,29. Mesmer was trained on the largest dataset to date for nuclear annotations (TissueNet)23. TissueNet contains 2D nuclear annotations of 1.2 million nuclei from six imaging platforms, nine organs, and three species to allow generalizability.

In this study, we benchmark the performance of three pre-trained deep learning models of Cellpose, Mesmer, and StarDist, which are trained for the specific purpose of segmentation of nuclei in fluorescence imaging. It is important to note that there are newly developed foundation models that can perform segmentation on multiple different imaging modalities, which boast higher nuclear segmentation accuracies. These foundation models can be applied for nuclear segmentation in H&E-stained data48, as well as fluorescence data49. Another benchmark study also compares different multimodality cell segmentation approaches with Cellpose50. There is also a novel embedding-based nucleus and cell segmentation approach that performs with high accuracy and low processing time51, with a separate channel invariant architecture to specifically deal with the multi-channel nature of mIF data52. In this work, we have shown the increased nuclear segmentation accuracy that deep learning models provide compared to platforms using classical segmentation techniques. We evaluated the segmentation results on 60 ROIs and ~20000 nuclei in a high throughput manner. The developed pipeline provides all of the quantitative metrics in this study within 2 minutes. Additionally, we have benchmarked the nuclear segmentation accuracy of the pre-trained models of Cellpose, Mesmer, and StarDist for use in scalable studies with human tissue samples.

We primarily use an object-level F1-score, evaluated at multiple IoU thresholds to compare the different algorithms and models. For density, counts, and whole slide-level single-cell spatial analysis, the F1-score at an IoU threshold of 0.5 is a good metric as it captures the accuracy of the object detection task. For spatial profiling of mIF data using nuclear and membrane markers, it is important to accurately segment the boundaries of the nuclei as well as to capture the staining of markers in and around the nuclei so that the cell phenotype classifiers can accurately assign phenotypes to the cells. For studies where the morphology of individual nuclei is being studied, the F1-score at high IoU thresholds is a better metric. Therefore, we also define another composite metric: the area under the curve (AUC) of the F1-score across all IoU thresholds, providing a collective measure of both the accuracy of the object detection task and the segmented morphology.

From the results of this study, it is clear that Cellpose model performance can be improved by re-annotating false negative predictions and Memser’s can be improved by removing/editing false positive predictions. This can be done via a human-in-the-loop approach to improve model performance on specific datasets. In line with this, our lab has worked extensively with Cellpose on other datasets and has seen significant improvement in nuclear segmentation accuracy by providing fine-tuning annotations for the nuclei that the base Cellpose model misses/under segments. However, the need for extensive training data in deep learning models is a challenge in their customization and evaluation. There is research being conducted to use a combination of classical segmentation techniques (Otsu thresholding and watershed algorithms) to automate and fast-track dataset annotation for deep learning segmentation model training and testing53,54, enabling their widespread use.

It is important to note that even though we are only considering nuclei in this study as we utilize the DAPI channel, the same pipeline can be extended for cell segmentation. Directly segmenting whole cells is difficult because whole cell morphologies are more variable than that of nuclei alone55, and ensuring adequate cytoplasm/membrane markers for mIF with a limited number of markers can be challenging. When cell membrane or cytoplasm markers are not available for every cell type in a dataset, a commonly used procedure to approximate the whole cell boundary from the DAPI channel is to have the cytoplasm be an area within a fixed radius from the nucleus56. Additionally, we benchmark and compare the nuclear segmentation performance of algorithms and pre-trained models on Vectra Polaris data. Future studies can translate our pipeline to other mIF technologies like CODEX and other imaging platforms.

Methods

Datasets

-

(1)

In-house datasets: formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections were used to acquire 6-plex multispectral images, aka “multiplexed immunofluorescence images,” using the PhenoImager HT (Akoya Biosciences) and the 7-color opal reagent kit. The data used in this study was collected at two different sites (University of Washington and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center). Multiplexed immunofluorescence (mIF) whole slide images (WSIs) at ×20 magnification from 3 human tissue types (tonsil, melanoma, and breast) comprised this dataset. These were imaged with 5 different imaging runs. One multispectral field of view was chosen from each WSI using Phenochart™ whole slide viewer software (Akoya Biosciences), and 4 subregions were sampled from each field. We also developed code in Python to sample and extract the field from the WSI given coordinates, which is provided in the GitHub repository and eliminates the need for Phenochart based on reviewer suggestion. Therefore, we used a total of 20 images (256 × 256 pixels) for our nuclear segmentation performance analysis (3967 total ground truth nuclei). This sampling strategy was selected to incorporate heterogeneity across tissue samples and account for intra-tissue heterogeneity. We also attempted to sample the subregions across a range of nuclear densities. This curated dataset is freely available via the Zenodo repository 1330671438 for use by other developers and labs.

-

(2)

Public datasets for benchmarking: the external, benchmarking dataset is hosted in Synapse39. We included data from 6 human tissue types (Fig. 4B) spanning a total of 16,197 nuclei extracted from 40 images (400 × 400 pixels) sampled from 27 WSIs at ×20 magnification. The whole external dataset has data from three multiplex fluorescence imaging technologies: (1) sequential multiplex IF unmixing via Akoya Vectra/PhenoImager HT, (2) sequential multiplex IF narrowband capture via Ultivue InSituPlex with Zeiss Axioscan image capture, and (3) cyclic multiplex IF narrowband capture via Akoya CODEX. We incorporated 16197 nuclei from the 40 ROIs imaged using the Akoya PhenoImager HT system that had paired DAPI intensity signal with the ground truth data. While being compatible with our pipeline, the Akoya CODEX and Ultivue InSituPlex data did not have enough nuclear annotations (as opposed to whole-cell annotations) to yield meaningful benchmarking using this pipeline.

Study approval

Only de-identified tissue samples were used, which do not classify as human subjects and did not require a separate IRB approval.

Hardware environment

The algorithms were run using two different hardware environments, as described below:

-

(1)

CPU:

-

System: Windows 11 Enterprise

-

CPU: 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700K 3.60 GHz

-

RAM: 64 GB

-

(2)

GPU:

-

System: Windows 11 Enterprise

-

GPU: NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 12 GB

-

RAM: 64 GB

-

CPU: 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-12700K 3.60 GHz

-

CUDA: version 12.7

Preprocessing

We do not perform any pre-processing of the DAPI intensity signal before nuclear segmentation with any algorithm. However, the deep learning frameworks of Mesmer23, StarDist28, and Cellpose29 all perform some in-built normalization before implementing their respective segmentation algorithms.

Nuclear segmentation

Seven algorithms were compared in this study for their nuclear segmentation performance. Cellpose29 (pre-trained “nuclei” model), Mesmer23, and StarDist28 (pre-trained “2D_versatile_fluo” model) employ emerging pre-trained deep learning frameworks. The in-built nuclear segmentation tools of platforms that utilize classical morphological segmentation techniques were also implemented: Fiji21,40, CellProfiler41,42,43,44, inForm® (Akoya Biosciences), and QuPath45. inForm® and QuPath are two of the commonly used segmentation platforms, particularly for mIF data in labs and clinical settings14,57. An overview of our analysis pipeline is given in Fig. 1. The guidelines for implementing algorithms and the associated Python code are available through the Supplementary Note 1 and GitHub repository. Once the segmented masks were predicted from each algorithm, one-pixel erosion post-processing on connecting parts of distinct nuclei was implemented to visualize the overlaid segmented masks and ground truth masks for qualitative comparisons.

Ground truth nuclei annotation

Nuclei were annotated in this study for the generation of the in-house dataset (Fig. 1A(vi)). In our evaluation of 2D nuclear segmentation, all the algorithms predict non-overlapping nuclei. To preserve this in the ground truth masks, we annotated the ground truth nuclei and split the overlapping nuclei such that the nucleus on the top (determined observationally) incorporated the overlapping region while truncating the nucleus on the bottom so that the resulting two nuclei do not have any overlap. GIMP image editor (https://www.gimp.org/) was used to create ground truth annotations. Boundaries of the nuclei were annotated using a 1 × 1 pixel square brush (Fig. 1A(iii)). The annotations were then filled with white (foreground) using a bucket fill tool and touching regions of nuclei were separated by a 2-pixel gap (Fig. 1C(iv)). The opacity of the annotated binary mask layer was then turned up to 100% before exporting the ground truth binary mask as a .TIFF file (Fig. 1A(v)).

Ground truth nuclei were used in this study from both the in-house and external datasets. Representative ground truth annotations are shown in Fig. 7 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Evaluation

Nuclear segmentation performed by the different algorithms was evaluated in this study by measuring the difference between the nuclei mask output from the algorithms and a reference ground truth nuclei (annotated) mask. The primary evaluation metric in this study was an object-based F1-score. A higher F1-score indicates an algorithm’s ability to more accurately segment nuclei on an object level. F1-scores are a commonly used metric for the evaluation of nuclear segmentation performance in mIF workflows36,58. The F1-scores in this study were computed as described by Caicedo et al.22, using a threshold of the overlapping area between the predicted and ground truth nuclei masks22. Intersection-over-union (IoU) between ground truth nuclei (T) and predicted nuclei by the individual algorithms (P) was first calculated as:

For n ground truth nuclei and m predicted nuclei, an n × m matrix was computed with all IoU values between ground truth and predicted nuclei. The resulting matrix was sparse in nature because few prediction-ground truth nuclei pairs had overlapping areas to have non-zero IoU scores22. A true positive predicted nucleus was identified if it had an IoU greater than a pre-set threshold with a ground truth nucleus. Predicted nuclei that did not have IoU with any ground truth nucleus greater than the threshold were identified as false positives, and ground truth nuclei that did not have IoU with any predicted nucleus greater than the threshold were identified as false negatives. Overlapping nuclei were treated as distinct nuclei separated by a dividing line that was two pixels in width. The two-pixel gap was added both in ground truth annotations as well as in the post-processing of binary nuclei masks output from the various digital segmentation tools for consistency. Setting the IoU threshold at 0.5 or above ensures that only one true positive predicted nucleus could be assigned to a ground truth nucleus. We computed the F1-scores across a varying range of IoU thresholds to capture the holistic performance of the different segmentation algorithms. For IoU thresholds less than 0.5, there is a possibility of multiple matches of (true positive) predicted nuclei with one ground truth nucleus. In this case, the prediction with the highest IoU is assigned as the true positive while the others are assigned as false positives. We also generated three other object-level quantitative metrics: precision, recall, and Jaccard index. It is worth noting that the F1-score is the harmonic mean of the precision and recall metrics. Precision measures the ratio of predicted nuclei that are true positives and recall measures the ratio of ground truth nuclei that have a corresponding true positive prediction. The Jaccard index is the ratio of the number of true positive nuclei (intersection of predictions and ground truth) to the number of nuclei in the union of the predictions and ground truth. Using the computed IoU matrix and defined IoU threshold, the number of true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN) can be counted. The object-level metrics are calculated as:

The protocol and code used to generate quantitative metrics and subsequent visualization are in Supplementary Note 1 and the GitHub repository, respectively.

Statistics and reproducibility

Confidence intervals, the number of evaluation regions, and the number of nuclei in each evaluation region are reported where relevant. Quantitative comparison between the nuclear segmentation tools was performed on a region-level. Quantitative metrics for each region were computed to assess the object-level segmentation performance of all nuclei in the respective regions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The DAPI intensity signal of ROIs from our in-house generated dataset, along with paired nuclear ground truth and segmentation binary masks used for evaluating the different algorithms/models are available in Zenodo repository 13306714 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1330671438. In our Zenodo repository 1330671438 we have a spreadsheet directly identifying the specific ROIs that we used to curate the merged dataset in this study from the external dataset in the Synapse repository at https://doi.org/10.7303/SYN2762481239. Source data for figures can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The guidance and code for nuclear segmentation with various platform GUIs and python-based models and visualization/evaluation of segmentations are available in Supplementary Note 1 and the GitHub repository at https://github.com/Shachi-Mittal-Lab/nuclear_segmentation. All code is available under an open-source MIT license.

References

Lim, J. C. T. et al. An automated staining protocol for seven-colour immunofluorescence of human tissue sections for diagnostic and prognostic use. Pathology 50, 333–341 (2018).

Almekinders, M. M. et al. Comprehensive multiplexed immune profiling of the ductal carcinoma in situ immune microenvironment regarding subsequent ipsilateral invasive breast cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 127, 1201–1213 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Multiplexed immunofluorescence identifies high stromal CD68+PD-L1+ macrophages as a predictor of improved survival in triple negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep.11, 1–12 (2021).

Vanguri, R. S. et al. Tumor immune microenvironment and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in hormone receptor/HER2+ early stage breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 22, 538–546 (2022).

Yaseen, Z. et al. Validation of an accurate automated multiplex immunofluorescence method for immuno-profiling melanoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 810858 (2022).

Huang, Y. K. et al. Macrophage spatial heterogeneity in gastric cancer defined by multiplex immunohistochemistry. Nat. Commun.10, 1–15 (2019).

Taube, J. M. et al. The Society for Immunotherapy in Cancer statement on best practices for multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF) staining and validation. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, 155 (2020).

Wortman, J. C. et al. Spatial distribution of B cells and lymphocyte clusters as a predictor of triple-negative breast cancer outcome. npj Breast Cancer 7, 1–13 (2021).

Hoyt, C. C. Multiplex immunofluorescence and multispectral imaging: forming the basis of a clinical test platform for immuno-oncology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 674747 (2021).

Wilson, C. M. et al. Challenges and opportunities in the statistical analysis of multiplex immunofluorescence data. Cancers13, 3031 (2021).

Tzoras, E. et al. Dissecting tumor-immune microenvironment in breast cancer at a spatial and multiplex resolution. Cancers 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14081999 (2022).

Tomimatsu, K. et al. Precise immunofluorescence canceling for highly multiplexed imaging to capture specific cell states. Nat. Commun.15, 1–16 (2024).

Tan, W. C. C. et al. Overview of multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence techniques in the era of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 40, 135–153 (2020).

Rojas, F., Hernandez, S., Lazcano, R., Laberiano-Fernandez, C. & Parra, E. R. Multiplex immunofluorescence and the digital image analysis workflow for evaluation of the tumor immune environment in translational research. Front. Oncol. 12, 1 (2022).

Parra, E. R. et al. Procedural requirements and recommendations for multiplex immunofluorescence tyramide signal amplification assays to support translational oncology studies. Cancers12, 255 (2020).

Liu, C. C. et al. Robust phenotyping of highly multiplexed tissue imaging data using pixel-level clustering. Nat. Commun.14, 1–16 (2023).

Bortolomeazzi, M. et al. A SIMPLI (Single-cell Identification from MultiPLexed Images) approach for spatially-resolved tissue phenotyping at single-cell resolution. Nat. Commun.13, 1–14 (2022).

Otsu, N. Threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cyber. SMC-9, 62–66 (1979).

Roerdink, J. B. T. M. & Meijster, A. The watershed transform: definitions, algorithms and parallelization strategies. Fundam. Inf. 41, 187–228 (2000).

Irshad, H., Veillard, A., Roux, L. & Racoceanu, D. Methods for nuclei detection, segmentation, and classification in digital histopathology: a review-current status and future potential. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 7, 97–114 (2014).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods9, 676–682 (2012).

Caicedo, J. C. et al. Evaluation of deep learning strategies for nucleus segmentation in fluorescence images. Cytometry 95, 952 (2019).

Greenwald, N. F. et al. Whole-cell segmentation of tissue images with human-level performance using large-scale data annotation and deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 555 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. NuSeT: a deep learning tool for reliably separating and analyzing crowded cells. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008193 (2020).

Caicedo, J. C. et al. Nucleus segmentation across imaging experiments: the 2018 Data Science Bowl. Nat. Methods16, 1247–1253 (2019).

Hollandi, R. et al. nucleAIzer: a parameter-free deep learning framework for nucleus segmentation using image style transfer. Cell Syst. 10, 453–458.e6 (2020).

Han, W., Cheung, A. M., Yaffe, M. J. & Martel, A. L. Cell segmentation for immunofluorescence multiplexed images using two-stage domain adaptation and weakly labeled data for pre-training. Sci. Rep.12, 1–14 (2022).

Schmidt, U., Weigert, M., Broaddus, C. & Myers, G. Cell detection with star-convex polygons. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinforma.11071 LNCS, 265–273 (2018).

Stringer, C., Wang, T., Michaelos, M. & Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat. Methods18, 100–106 (2020).

Al-Kofahi, Y., Zaltsman, A., Graves, R., Marshall, W. & Rusu, M. A deep learning-based algorithm for 2-D cell segmentation in microscopy images. BMC Bioinforma. 19, 1–11 (2018).

Vahadane, A. et al. Development of an automated combined positive score prediction pipeline using artificial intelligence on multiplexed immunofluorescence images. Comput. Biol. Med. 152, 106337 (2023).

Falk, T. et al. U-Net: deep learning for cell counting, detection, and morphometry. Nat. Methods16, 67–70 (2018).

Maric, D. et al. Whole-brain tissue mapping toolkit using large-scale highly multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging and deep neural networks. Nat. Commun.12, 1–12 (2021).

Meijering, E. Cell segmentation: 50 years down the road [life Sciences]. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 29, 140–145 (2012).

Kumar, N. et al. A dataset and a technique for generalized nuclear segmentation for computational pathology. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 36, 1550–1560 (2017).

Kromp, F. et al. Evaluation of deep learning architectures for complex immunofluorescence nuclear image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 1934–1949 (2021).

Chen, H. & Murphy, R. F. Evaluation of cell segmentation methods without reference segmentations. Mol. Biol. Cell 34, ar50 (2023).

Sankaranarayanan, A., Khachaturov, G., Smythe, K. S. & Mittal, S. Standardized framework and quantitative benchmarking: nuclear segmentation platforms for multiplexed immunofluorescence data in translational studies. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12775616 (2024).

Aleynick, N. et al. Cross-platform dataset of multiplex fluorescent cellular object image annotations. Sci. Data 10, 1–6 (2023).

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S. & Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

McQuin, C. et al. CellProfiler 3.0: next-generation image processing for biology. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005970 (2018).

Lamprecht, M. R., Sabatini, D. M. & Carpenter, A. E. CellProfiler: free, versatile software for automated biological image analysis. Biotechniques 42, 71–75 (2007).

Carpenter, A. E. et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7, 1–11 (2006).

Jones, T. R. et al. CellProfiler analyst: data exploration and analysis software for complex image-based screens. BMC Bioinforma. 9, 1–16 (2008).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep.7, 1–7 (2017).

Teng, Q., Liu, Z., Song, Y., Han, K. & Lu, Y. A survey on the interpretability of deep learning in medical diagnosis. Multimed. Syst. 28, 2335 (2022).

Durkee, M. S., Abraham, R., Clark, M. R. & Giger, M. L. Artificial intelligence and cellular segmentation in tissue microscopy images. Am. J. Pathol. 191, 1693–1701 (2021).

Zhao, T. et al. A foundation model for joint segmentation, detection and recognition of biomedical objects across nine modalities. Nat. Methods 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-024-02499-w (2024).

Israel, U. et al. A foundation model for cell segmentation. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.17.567630 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. The multimodality cell segmentation challenge: toward universal solutions. Nat. Methods21, 1103–1113 (2024).

Goldsborough, T. et al. InstanSeg: an embedding-based instance segmentation algorithm optimized for accurate, efficient and portable cell segmentation. arXiv:2408.15954 (2024).

Goldsborough, T. et al. A novel channel invariant architecture for the segmentation of cells and nuclei in multiplexed images using InstanSeg. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.04.611150. (2024).

Englbrecht, F., Ruider, I. E. & Bausch, A. R. Automatic image annotation for fluorescent cell nuclei segmentation. PLoS ONE 16, e0250093 (2021).

Helmbrecht, H., Lin, T. J., Janakiraman, S., Decker, K. & Nance, E. Prevalence and practices of immunofluorescent cell image processing: a systematic review. Front. Cell Neurosci. 17, 1188858 (2023).

Bosisio, F. M. et al. Next-generation pathology using multiplexed immunohistochemistry: mapping tissue architecture at single-cell level. Front. Oncol. 12, 918900 (2022).

Harms, P. W. et al. Multiplex immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence: a practical update for pathologists. Mod. Pathol. 36, 100197 (2023).

Parra, E. R., Francisco-Cruz, A. & Wistuba, I. I. State-of-the-art of profiling immune contexture in the era of multiplexed staining and digital analysis to study paraffin tumor tissues. Cancers11, 247 (2019).

De León Rodríguez, S. G. et al. A machine learning workflow of multiplexed immunofluorescence images to interrogate activator and tolerogenic profiles of conventional type 1 dendritic cells infiltrating melanomas of disease-free and metastatic patients. J. Oncol. 2022, 9775736 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the startup grant provided by the Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Washington. The multispectral imaging system was jointly funded by the Department of Chemical Engineering and the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at the University of Washington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. and A.S. conceptualized and designed the research. A.S. and K.S. acquired, processed, and analyzed multispectral imaging data. A.S. and G.K. performed the nuclear segmentation across platforms and annotated data for ground truth nuclei segmentation masks. A.S. created the standardized postprocessing and evaluation scheme. S.M., A.S. and G.K. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ophelia Bu.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sankaranarayanan, A., Khachaturov, G., Smythe, K.S. et al. Quantitative benchmarking of nuclear segmentation algorithms in multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging for translational studies. Commun Biol 8, 836 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08184-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08184-8