Abstract

We present MINT (Multilayer Integration of Networks Toolbox), a Python package for multimodal data integration and community detection. MINT includes data standardization, Similarity Network Fusion, Generalized Louvain clustering, visualization, cross-validation, and modality selection optimization, capturing complex relationships among disease markers. We applied MINT to two multimodal datasets spanning the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) spectrum: a primary cohort of 206 participants and a validation cohort of 143 participants, including structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), amyloid positron emission tomography (PET), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), cognition, and genetics. We hypothesized that modeling intra- and inter-modality associations would improve AD prediction and identify preclinical cases. Across both datasets, MINT identified PET and CSF as optimal modalities and detected two communities: one AD-dominant and one cognitively normal-dominant (CN). Sensitivity and specificity for CN and AD were 84.38% (95% CI: 73.14–92.24) and 92.65% (95% CI: 83.67–97.57). The AD-dominant community exhibited poorer cognition and higher genetic risk and AD pathology (p < 0.001). CN individuals in this group showed elevated amyloid (p=0.009), tau (p=0.004), and ptau (p < 0.001) compared to AD individuals in the CN-dominant group. MINT can identify biologically relevant subgroups, predict disease progression, and serves as a powerful tool for uncovering complex relationships across heterogeneous and multifactorial disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most psychiatric and neurological conditions are heterogeneously manifested by a broad multifactorial spectrum of complex interactions where various biomarkers represent different aspects of the disorder1. Unraveling the heterogeneity of such diseases allows for effective diagnostics and treatment2. Therefore, capturing interactions among different aspects of a disease, including biology, pathology, and behavior, requires tools able to explore the relationships between biomarkers. This can be done through a model that identifies biologically coherent subtypes in a population. Although studying biomarkers independently provides important insights, it does not account for the impact of possible links between them. A single biomarker is a suboptimal individual predictor but increases the ability to detect disease by interacting with other biomarkers. Such interactions enhance the predictability of early diagnoses. Over the past decades, multimodal data has enabled scientists to explore a multitude of biomarkers, such as imaging, clinical, and biological, to decipher the heterogeneity within clinically defined disorders. Translation of findings from a multimodal approach using a single model has been of interest to many researchers, as it may allow for the identification of conditions using a single modality but also allow us to consider inter-modality relations through a single model.

From a modeling perspective, multimodality focuses on three major categories3 (a) multimodal representation learning4, (b) multimodal transformation and alignment5, and (c) multimodal fusion and collaborative learning6. All these categories offer a broad range of models, such as supervised deep learning methods7 and unsupervised graph-based modeling, and require multimodal data collection, including imaging, demographic, cognition, and genomics data. Supervised methods using deep learning algorithms mainly focus on medical imaging data and their clinical labels to train models, and such models require an enormous amount of multimodal data, which is considered a limitation. In graph-based approaches, a model explores inter- or intra-connectivity between modules or communities built in a graph using similarity features extracted from multimodal data. In this approach, nodes of the graph represent individuals, and the strength of the connections between nodes represents the similarity of individuals on a biomarker of interest. Network-based community detection algorithms are then applied to cluster nodes in each network that are strongly connected within a cluster but poorly connected to the nodes of other clusters. This framework offers the ability to utilize various features with different scales, such as demographics or cognitive data, to capture heterogeneity in a disease. This capability allows community detection based on network topology and shared features across nodes beyond their connectivity patterns8.

Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) and Generalized Louvain (GenLouvain) are two graph-based approaches able to fuse multimodal data. GenLouvain can handle networks that have multiple layers, where each layer represents a different type of relationship (or modality) between the same nodes. SNF is an advanced community detection method that utilizes multimodal data to construct an individual sample-similarity network for each modality and fuses the similarity networks into one single similarity network by applying a nonlinear combination method9. Overall, SNF aims at increasing signals in underlying data by efficiently integrating each data type similarity network into one representing a full spectrum of all modalities9. Unlike the GenLouvain community detection algorithm10, which uses multimodal networks to identify communities within the network using modularity optimization, multilayer SNF generates a unified network from multimodal data by calculating pairwise similarities among data points9.

This manuscript presents MINT, an open-source Python package (https://code.stanford.edu/cbrain/mint) designed to facilitate multilayer network integration and community detection utilizing multimodal data at scale (see “Code availability” for more details). MINT comprises several modules crafted to (a) standardize input data, (b) execute GenLouvain or multilayer SNF algorithms, (c) visualize intermediate results, (d) perform cross-validation techniques, and (e) optimize identified communities by selecting an optimal combination of modalities, maximizing silhouette scores. MINT offers an extensive array of parameters with predefined default values, augmenting the flexibility for advanced community detection while ensuring users can obtain standard outcomes utilizing base parameters. Furthermore, we propose a post-processing mechanism integrated within MINT, which systematically assigns predefined labels to community constituents, thereby delineating subgroups within communities to facilitate statistical analyses. Implementing MINT enables rapid scalability to accommodate diverse multimodal datasets across various domains.

To demonstrate the capabilities of the MINT package, we applied it to a multimodal dataset of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD is a neurodegenerative disorder resulting in progressive cognitive decline and behavioral changes. It primarily affects older individuals and is the leading cause of dementia worldwide. Pathologically, AD is characterized by the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates in the brain, including beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles, which disrupt neuronal function and communication11. As the disease advances, these protein deposits lead to widespread neuronal damage and death, particularly in regions crucial for memory and other cognitive functions, such as the medial temporal lobe and the neocortex. The exact etiology of AD remains unclear, but genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors are thought to contribute to its development12.

Community detection using multimodal data plays a crucial role in AD prediction due to its capacity to capture the comprehensive and heterogeneous nature of the disease. AD pathology involves complex interactions across multiple levels of brain structure and function, including alterations in neuronal connectivity, protein aggregation, and neuroinflammation. Utilizing multimodal data, such as pathological, structural and functional neuroimaging, genetics, fluid biomarkers, and clinical assessments, enables a holistic understanding of these underlying mechanisms. Our MINT package integrates diverse data sources and community detection methods, including GenLouvain and SNF, followed by an optimization step that can identify distinct subnetworks or communities that exhibit coordinated changes across modalities in individuals along the AD spectrum. MINT identifies these communities, which may correspond to functional networks, genetic profiles, or clinical phenotypes, providing valuable insights into disease progression and heterogeneity. Moreover, multimodal community detection facilitates the development of predictive models that leverage complementary information from different data modalities, enhancing the accuracy and robustness of AD prediction.

Results

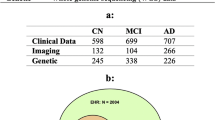

MINT successfully predicts future AD

To test the effectiveness of our package, we applied it to data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI, http://adni.loni.usc.edu). ADNI is a large-scale longitudinal multicenter project developed with the goal of creating and validating biomarkers for the detection of AD. Details on the inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found elsewhere13, and informed consent was obtained from all participants or their authorized representatives. The sample used in our study consists of 206 participants (age 71.75 ± 7.08, 55–90.3, 95 women), shown in Table 1, who had complete data across five modalities: genetics, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, cognition, FreeSurfer-derived (FS) structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) at baseline (for details on specific modalities see Supplementary Information). The sample included cognitively healthy (CN), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD individuals. Individuals with MCI or dementia unrelated to AD were excluded from statistical analyses. MCI was diagnosed following the Petersen criteria, which includes a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) between 24 and 3014, subjective memory concerns, abnormal memory function15, a clinical dementia rating of 0.516, absence of significant impairment in other cognitive domains, and absence of dementia. A participant was considered to have AD if they met the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable dementia17. To further understand the clinical relevance of the identified communities, we examined longitudinal diagnostic conversion trends among community members. Notably, several CN individuals grouped into AD-dominant communities exhibited higher-than-expected rates of progression to MCI or AD at follow-up, while some AD-diagnosed subjects in CN-dominant communities showed relatively stable trajectories. These findings suggest that community membership may reflect latent phenotypic patterns not fully captured by baseline clinical labels and support the potential of MINT to identify at-risk sub-populations in an unsupervised, data-driven manner. A detailed breakdown for each community is provided in Supplementary Table 1 as well as Supplementary Fig. 1. See Table 2 for group comparisons between CN and AD individuals.

In order to obtain our SNF results, the data were first normalized (with the exception of genetics), and covariates were regressed out. For MRI and PET, covariates included age, gender, and total intracranial volume (ICV); for CSF and cognition, these included age and gender, and for genetics, only gender was used. Spearman correlations between measures across subjects were then calculated for each modality to extract similarity matrices. Next, the toolbox extracted communities using a multimodal SNF approach, followed by 10-fold cross-validation. Finally, the most optimized set of modalities was identified using our enhanced Silhouette score-based algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Figure 1 demonstrates five modalities and communities detected by SNF for the original SNF as well as optimized with and without cross-validation.

This figure visualizes the communities detected using the SNF algorithm across five modalities. It compares original SNF, optimized SNF without cross-validation, and optimized SNF with cross-validation. The latter, which maximized silhouette scores, produced the most cohesive clustering, identifying two clinically meaningful communities representing AD-dominant and CN-dominant subgroups.

Here, we show the results for the optimized SNF with cross-validation (Fig. 1), as this analysis yielded the most cohesive communities as indicated by the silhouette score as the goodness metric for clustering (for results using GenLouvain, see Supplementary Fig. 1). The optimization module of MINT identified CSF and PET as the best-performing modality combination in this dataset. Two different communities were identified, one including the majority of CN and stable MCI participants (community 1) and the other including the majority of present and future AD cases (community 2) (see Table 2 for final diagnosis details and Supplementary Table 2 for baseline diagnosis). Sensitivity and specificity for CN and AD individuals were 84.38% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 73.14–92.24) and 92.65% (95% CI: 83.67–97.57), respectively. We further examined the dimensions in which communities differed from one another (Bonferroni corrected p = 0.0036). Firstly, there were no differences between communities in age (t(204) = −1.134, p = 0.129) or sex (χ(1) = 0.257, p = 0.612). APOEϵ4 status differed between groups, with those in community 2 including more individuals with one or two ϵ4 allele(s) (χ(4) = 44.203, p < 5.82 × 10−9). Those in community 2 were also less educated (t(204) = 2.255, p = 0.013). Importantly, the communities differed in a range of clinical and cognitive assessments, with community 2 showing worse performance in the MMSE (t(101.636) = 6.571, p < 0.001), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; t(203) = 6.483, p < 0.001), Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS13; t(111.827) = −7.082, p < 0.001), and clinical dementia rating (CDR; t(92.399) = −6.721, p < 0.001). Likewise, the communities differed in measures of AD pathology (see Fig. 1) such as amyloid PET (t(204) = −18.882, p < 0.001), CSF amyloid (t(199.485) = 17.077, p < 0.001), tau (t(80.451) = −9.735, p < 0.001), ptau (t(88.589) = −12.359, p < 0.001), and hippocampal volume (t(187) = 4.391, p < 0.001). Based on these findings illustrated in Fig. 2, we refer to community 1 and 2 as CN- and AD-dominant, respectively.

Furthermore, when comparing MCI individuals between communities, we found a significant difference in amyloid PET (U = 132, p < 0.001), with those in the AD-dominant community having higher amyloid load than those in the CN-dominant community (Fig. 1). The communities were also significantly different in CSF amyloid (U = 90, p < 0.001), tau (U = 274.50, p < 0.001), and ptau (U = 87.50, p < 0.001). These results suggest that MCI cases in community 2 are more likely to have AD-related MCI, compared to those in community 1, or to be at a more advanced stage of the disease.

MINT is able to capture pathology regardless of mismatches between diagnosis and community allocation

Next, we investigated subjects whose diagnosis did not match their community allocation. CN subjects who were placed in community 2, the AD-dominant community, correspond to only 7.4% of all individuals who developed AD at final available diagnosis. In addition, we compared CN and AD participants within the AD-dominant community in regard to amyloid load, but found no significant differences (U = 106, p = 0.895), suggesting that CN individuals allocated to the AD-dominant community had an equivalent amount of amyloid in the brain compared to those already diagnosed with AD.

In addition, we compared AD individuals between community 1 and 2, and found that AD cases in the CN-dominant community had significantly less AD-related pathology as measured by amyloid PET (U = 52.5, p < 0.001), CSF tau (U = 32.5, p < 0.001) and CSF ptau (U = 34.5, p < 0.001) when compared with AD subjects in the AD-dominant community. Similarly, CN individuals in community 1 and 2 differed in the same measures of pathology (amyloid PET: U = 4, p < 0.001; CSF tau: U = 17, p < 0.001; CSF ptau: U = 15, p < 0.001), with CN individuals in the AD-dominant community showing a higher load of amyloid and tau. Finally, we compared CN individuals in the AD-dominant and AD individuals in CN-dominant communities. These yielded interesting findings, since healthy individuals allocated to the AD-dominant community showing higher pathology than AD individuals allocated to the CN-dominant community (amyloid PET: t(13) = −2.686, p = 0.009; CSF tau: t(13) = −3.138, p = 0.004; CSF ptau: t(13) = −4.309, p < 0.001). This is noteworthy, suggesting that our methodology was able to identify participants who were labeled as cognitively normal but who still displayed higher pathology levels than individuals already formally diagnosed with AD. Our findings also indicate that the identified communities capture meaningful variation in glucose metabolism, as evidenced by significant differences in FDG uptake between groups shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4.

MINT captures amyloid positivity

We also investigated whether our methodology was successful in identifying amyloid-positive individuals regardless of diagnosis. As visible in Fig. 3, the AD-dominant community was composed exclusively of amyloid-positive individuals, whereas the CN-dominant community included all amyloid-negative and 37 amyloid-positive participants. Importantly, individuals in the AD-dominant community had significantly higher amyloid load (t(105) = −4.095, p < 0.001), as well as lower hippocampal volume (t(96) = 2.795, p = 0.003). Interestingly, the amyloid positive individuals in the two communities also differed in other AD pathological measures such as CSF amyloid (t(105) = 8.359, p < 0.001), CSF tau (t(105) = −5.865, p < 0.001) and CSF ptau (t(105) = −7.744, p < 0.001). Overall, these findings suggest that amyloid-positive individuals in the AD-dominant community have a significantly higher level of pathology compared to amyloid-positive individuals in the CN-dominant community and are at a more advanced stage of the disease.

Amyloid positivity, showing both the number of individuals who are amyloid positive in each community as well as PET amyloid load in amyloid-positive individuals. Boxplot centerline: median; box limits: upper and lower quartiles; whiskers: 1.5× interquartile range (IQR); outliers: beyond 1.5 the IQR.

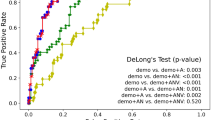

Validation and early signs of Alzheimer’s pathology

We validated our findings using an independent sample of 143 ADNI individuals (age 71.54 ± 6.80, 55–89, 65 women) who had baseline genetics, CSF biomarkers, cognition, MRI, and amyloid PET. The validation sample showed similar results to the main analyses (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Similar to the previous internal validation, the optimization module of MINT selected CSF and PET as the optimal combination of modalities in this external validation dataset (Silhoutte scores shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). Community 1 had 96.1% of CN individuals and community 2 had 78.3% of AD individuals at final diagnosis. We further compared groups using non-parametric tests and a Bonferroni corrected p-value of 0.0063. Communities differed in cognitive performance, with community 2 displaying worse cognition in the MMSE (U = 1134.5, p < 0.001), MoCA (U = 1144.5, p < 0.001), ADAS13 (U = 927.5, p < 0.001), and CDR (U = 1065, p < 0.001) scale. Moreover, community 2 had higher levels of AD-related pathology (Fig. 4) as measured by amyloid PET (U = 88, p < 0.001) CSF tau (U = 667, p < 0.001), ptau (U = 707, p < 0.001), and hippocampal volume (U = 557.5, p < 0.001). Amyloid PET (U = 5, p = 0.001), CSF tau (U = 13, p = 0.025), and ptau (U = 17.5, p = 0.037) were also significantly higher in AD individuals of community 2 compared to AD individuals of community 1. Importantly, the high degree of similarity between the main results and validation findings displays the robustness of MINT as a predictor of AD diagnosis.

Discussion

We implemented a scalable community detection toolbox in Python called MINT that allows researchers to (1) prepare a wide range of multimodal data, (2) apply GenLouvain or SNF, (3) enhance the robustness of communities detected through a cross-validation step, and (4) clarify what is the optimal combination of modalities by employing an enhanced Silhouette score-based optimization algorithm. The optimization technique developed in this toolbox is a unique capability based on evaluating the performance of communities and demonstrating the improvement in communities’ quality. Moreover, our toolbox addresses gaps in already existing tools, as it includes scalability, ease of use for non-technical users, customizable hyper-parameters for technical users, as well as cross-validation. The MINT optimization module is integral to enhancing community detection, as it selects the optimal combination of modalities based on the silhouette score, thereby strengthening community segregation and enabling more precise statistical analyses between communities. This approach significantly improves the silhouette score compared to the original SNF across all validations, highlighting its effectiveness. Moreover, a rigorous external validation process was implemented, benchmarking it against ADNI-optimized and cross-validated results. The validation sample displayed consistent patterns with the primary dataset, validating the robustness and reliability of the MINT framework in refining modality selection and advancing community-based analyses. In addition, we replicated the main findings of SNF using GenLouvain, which speaks to the generalizability and capabilities of our toolbox.

Our findings build on and extend prior research using multimodal approaches to understand heterogeneity in AD. While amyloid PET is often used to define amyloid positivity, we did not treat it as a simple binary label. Instead, we integrated it alongside other modalities within an unsupervised framework. This does not assume any prior diagnostic labels or cut-offs. These findings have been further validated using GenLouvain (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The fact that our method revealed distinct communities strongly aligned with known pathological signatures—including amyloid and tau levels, hippocampal atrophy, and cognitive decline—demonstrates that MINT can identify biologically coherent subgroups.

In particular, when applying our toolbox to a sample of participants across the AD spectrum, we were able to predict future AD cases with high accuracy. Our study shows that MINT is a promising tool for detecting future diseases by using a combination of multimodal data. This can be extrapolated to the identification and prediction of a myriad of outcome variables, such as cancer or psychiatric disorders9,18. In our specific case, the method was successful in identifying present and future AD in a group of 206 individuals. Individuals labeled as AD in our toolbox had a higher genetic risk, showed worse cognitive performance across a wide range of domains and tests, and displayed biological signs of AD pathology such as increased amyloid and tau and lower hippocampal volume. The AD-dominant community exclusively included individuals who were amyloid positive, regardless of their diagnostic label, suggesting that we are able to identify CN individuals who are at risk of developing AD as well as those with MCI due to dementia, as opposed to other etiologies. Of note, CN individuals in the AD-dominant community had significantly higher amyloid load than CN individuals in community 1, but also higher amyloid burden compared to AD participants within that same community. This suggests that our methodology is highly sensitive in predicting AD-related pathology, regardless of whether an individual is classified as cognitively healthy or not.

Importantly, we further compared AD participants between community 1 and 2, as well as CN participants, and found significant differences in AD-related pathology as measured by amyloid and tau. Specifically, AD and CN individuals in community 2 had higher levels of amyloid PET and CSF tau when compared to individuals with the same diagnosis in community 1. This suggests that, by exploring the composition of the identified communities using our methodology, we could identify individuals, regardless of whether they meet the standard criteria for probable AD.

Overall, AD is highly heterogeneous and multifactorial and includes subtypes that display different cognitive outcomes. As such, it cannot be captured by any single modality19,20,21. The MINT toolbox enables researchers to perform community detection on a wide range of distinct types of data by combining them in a way that increases the signal in each underlying modality and integrates it into one network that represents the entirety of the data. Our study simultaneously includes cognitive, brain, CSF, and genetics information and, using MINT, we were able to account for relationships between these AD markers. This is important because some modalities might have weak contributions to AD diagnosis individually18,19 but, when integrated into a joint network, they can increase their predictive ability.

Clinically, MINT provides a valuable tool for identifying at-risk individuals with subclinical pathology. Namely, MINT can identify those who appear cognitively normal but share biomarker similarities with AD individuals. This has implications for early intervention, clinical trials, and personalized monitoring of progression risk. The flexibility and scalability of MINT also make it applicable to other multifactorial neurological and psychiatric disorders, where multimodal integration is essential.

Understanding how these markers interact over time at a multidomain level is paramount for AD diagnosis and prediction. Future studies should focus on examining relationships between these domains at a longitudinal level, accounting for change in these variables. In addition, future work should attempt to use this framework to disentangle different kinds of dementia, such as frontotemporal, mixed, or vascular dementia. Lastly, a limitation of our work is that a confirmed diagnosis of AD can only be achieved through post-mortem identification of amyloid and tau. However, our participants did not have this information available. Still, it is important to highlight the highly consistent results across different types of comparisons that were carried out, both in regard to neuropsychological as well as brain measures of pathology19,22,23,24: (1) CN and AD individuals within the AD-dominant community displayed similar levels of brain pathology, (2) AD and CN individuals in the AD-dominant community had higher levels of amyloid and tau compared to those with the same diagnosis in the CN-dominant community, and (3) CN individuals in the AD-dominant community were worse off in regard to brain pathology compared to those with AD in the CN-dominant community. This clearly shows that using MINT yields highly accurate predictions of brain damage and behavioral outcomes, which can be used in a variety of disorders. In this example, by accurately predicting AD with high sensitivity and specificity, our results show that MINT is a valuable tool to capture complex relations between different markers of a given disease. This adds crucial knowledge to the implementation of better diagnostic and therapeutic tools for AD.

Methods

Purpose and overview

MINT is an open-source toolbox developed in Python that allows users to perform community detection on multimodal data through two approaches: (a) multi-layer GenLouvain and (b) SNF, with exhaustive pre- and post-processing capabilities. MINT offers three major post-processing steps after community detection to stabilize the outcomes and increase the robustness of the results. These include cross-validation, modality optimization, and cross-label phenotyping, allowing enhanced statistical analyses. The optimization step, based on evaluating the performance of communities, is a unique capability offered by this tool. Additionally, the MINT system design allows for rapid scaling on-premises or on cloud-based infrastructure, along with straightforward integration with web-based applications and visualization tools. Current tools available for community detection often lack scalability, ease of use for non-technical users, customizable hyper-parameters for technical users, cross-validation, and, importantly, robust optimization methods. MINT addresses these gaps with its simple interface while producing robust results. Further details on the practical toolbox command lines and execution can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

The MINT toolbox is data-type-agnostic, streamlining community detection using multimodal data and allowing a wide range of users, including non-technical individuals, to explore their data through unsupervised methods. MINT architecture shown in Fig. 5 includes (a) preprocessing, (b) GenLouvain community detection, (c) SNF, (d) cross-validation, (e) optimization, and (f) cross-label phenotyping. Users define parameter values for 31 toolbox arguments by creating or updating a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file available in Supplementary Table 3. Using this JSON configuration file, users can call the sole command line application programming interface (API), which initiates the process of community detection according to the user’s study design. The MINT toolbox offers default parameter values to enable non-technical users to build their baselines and adjust the parameters in subsequent iterations. According to user preference, the MINT toolbox generates and stores intermediate and final results in specified paths, which can be used for further analysis or visualization. In the next section, we introduce MINT step by step and provide details of the algorithms used in the toolbox.

Users execute the command line API, which activates the preprocessing module to read the pre-prepared JSON configuration file based on the study design. MINT preprocesses the multimodal data and directs the data to either GenLouvain or SNF (preferred method). After the algorithm detects communities, MINT performs cross-validation and an optimization step, if configured. The results are stored for cross-label phenotyping, if needed. A comprehensive description of each step illustrated in this figure is provided in the MINT Steps section.

MINT steps

Preprocessing

Preprocessing constitutes a critical initial step in the MINT toolbox. Upon execution of the command line API, the preprocessing module receives the request and extracts design parameters from the JSON configuration file. This module sequentially employs the following techniques: (a) outlier removal, (b) data normalization, and (c) affinity (similarity) matrix creation. Removing outliers is essential for community detection as they can disproportionately skew results, leading to inaccurate representations of underlying relationships and trends, thereby compromising the validity and reliability of the analytical conclusions25. MINT provides an optional outlier removal technique that detects outliers using a standard statistical approach, removing those that fall outside a specified standard deviation. MINT can replace outliers with the column median, mean, or missing values.

In the subsequent step, the toolbox normalizes multimodal data using the MinMax method, subtracting the minimum value from each data point and then dividing by the difference between the maximum and minimum values, or Max, only dividing values by the max value for each attribute (column) and observation (row) as specified in the configuration file. Data normalization ensures that variations in data scale do not distort the identification of communities, thereby enabling more accurate and meaningful clustering of nodes26. The toolbox allows users to select a subset of modalities and to determine whether column-based, row-based, or combined column-row normalization is required.

The final major step in the preprocessing module is the creation of a correlation matrix for each modality used during community detection by GenLouvain or SNF. The toolbox quantifies the similarity matrix using (a) Pearson correlation, (b) Kendall rank correlation, or (c) Spearman correlation methods and includes a threshold parameter to filter out correlation scores below the specified threshold. The selection of an appropriate correlation method directly impacts the quality of detected communities, with our investigations indicating that the Spearman method often yields more reliable results than the Pearson method because it measures the strength and direction of monotonic relationships using rank-ordering, making it less sensitive to outliers and non-linearities in the data. The outputs of the preprocessing step are cached in memory and can also be stored locally for use in subsequent community detection steps.

GenLouvain

MINT offers a classic approach to multi-dimensional networks using the multilayer GenLouvain algorithm10, which extends the basic Louvain algorithm to address complex scenarios such as multilayer networks27. If configured in the JSON file by users, MINT performs the community detection using the preprocessed multimodal data in a sequence of steps and generates subject-level community labels. In this context, subjects in a study are represented as the nodes of the network, while the connections between subjects, derived from correlations, form the edges. GenLouvain aims to optimize (maximize) the modularity metric, which measures the density of edges within communities compared to edges between communities. The algorithm operates through an iterative process that includes (a) local movement, where the nodes are relocated between communities to increase modularity, and (b) aggregation, in which each community is aggregated into a single node once no further improvements are achieved by relocating individual nodes, and the process continues the reduced graph. MINT incorporates the ω and γ parameters in the modularity equation in multilayer networks expressed as follows:

Where \(\frac{1}{2\mu }\) is a fraction representing the normalization factor, \(\sum _{ijl}\) denotes summation over all nodes i, j, and layers l and \({A}_{ij}^{l}\) represents the weight of the edge between nodes i and j in layer l. In this equation, γl is the resolution parameter for layer l that allows users to control the trade-off between maintaining consistent communities across layers and variability in community structure. The expected edge weight in a random graph is defined by \(\frac{{k}_{i}^{l}{k}_{j}^{l}}{2{m}^{l}}\). \(\delta ({c}_{i}^{l},{c}_{j}^{l})\) represents Kronecker delta function (equal to 1 if nodes i and j are in the same community in layer l) and \(\sum _{{l}^{{\prime} }\ne l}\) is the summation over different layers \({l}^{{\prime} }\). The inter-layer coupling parameter is denoted by ω, which influences the extent of consistency in community structure across different layers. δij represents the Kronecker delta function (equal to 1 if i = j), whereas \(\delta ({c}_{i}^{l},{c}_{i}^{{l}^{{\prime} }})\) is the Kronecker delta function (equal to 1 if node i is in the same community across layers l and \({l}^{{\prime} }\)).

SNF

MINT provides a comprehensive and customizable implementation of SNF, allowing users to explore community detection against multimodal data while overcoming certain challenges of previous approaches. SNF, the primary focus of our Python toolbox, is a sophisticated data integration technique that constructs a unified similarity network from multiple heterogeneous data sources. SNF offers significant advantages over classical community detection methods, such as GenLouvain, in terms of its ability to integrate multimodal data, capture complex relationships, and provide robust community detection in the presence of noise and missing data28,29. SNF employs an iterative process of message passing and update rules to transform the data into a similarity network by capturing intrinsic relationships among data points. These networks (communities) are then fused through a nonlinear combination of similarity matrices and refined iteratively. This process leverages techniques from spectral clustering to effectively integrate multimodal data, thereby improving the robustness and accuracy of the detected communities.

In the first step, the SNF module computes the initial similarity networks by measuring the pairwise similarity matrix, followed by normalization. Next, the similarity matrices are updated through an iterative process expressed as follows:

Where S(m, t+1) is the updated similarity matrix for data type m at iteration t + 1, P(m) represents the normalized similarity matrix, W denotes the initial similarity matrix, M represents the number of modalities, and α is a parameter controlling the influence of other data types. This iterative process continues until convergence, resulting in a final fused similarity matrix S. The SNF technique employs the spectral clustering method to identify and extract the underlying cluster structure from the fused similarity network. The spectral clustering utilized by SNF in this framework encompasses the following capabilities: (a) capturing non-linear relationships across multimodal data, (b) managing arbitrary shapes of clusters, (c) reducing data dimensionality, and (d) providing a global overview of the data structure. In the final stage of this process, the SNF module rearranges the communities based on their size (number of subjects in each community) and assigns subject-level community labels to the final fused network and each modality, facilitating further analysis.

Distance-based cross-validation: internal and external

MINT provides a distance-based cross-validation module designed to ensure the reproducibility and accuracy of community detection outcomes. We employed our technique for our cross-validation and external validation (within and between community validation). The core concept behind the implementation of cross-validation enhanced for MINT’s unsupervised community detection is the reassignment of observations to a community with higher similarity, characterized by a lower error distance30. Our primary approach involves a modified and iterative K-fold cross-validation technique applicable to the results from GenLouvain or SNF obtained in the previous step. Upon generating the communities for observations, and if configured by the users, MINT divides the observations into two subsets: training and testing. The training set is further divided into sub-training and validation samples, and the algorithm iteratively updates the community assignment of each observation. The following section elucidates the steps of the algorithm:

-

The community detection results are divided into training and testing sets based on the standard K-fold cross-validation concept.

-

The training set is divided into sub-training and validation sets according to the K-fold method.

-

The mean squared error (MSE) is calculated between each observation in the validation and sub-training sets. This step generates a set of scores along with labels (communities) from training samples for each observation in the validation set.

-

The label associated with the minimal MSE score is assigned to the corresponding observation in the validation set.

-

The algorithm iterates K times, producing updated labels for the validation set, which subsequently updates the sub-training samples.

-

The algorithm iterates K times to generate updated labels for the testing set, resulting in an updated version of all samples after K iterations.

We apply the above algorithm for external validation, using the results from the original dataset as the training set and the samples from the external validation dataset as the testing set. MINT assigns communities to the testing samples based on the labels generated from the original dataset. The time complexity of this iterative algorithm is O(K) = K2 * n2 where K and n represent the value of K-fold and the number of observations (samples), respectively. Our cross-validation method, like other standard methods, may increase the processing time for K>> and n>>, where the default K = 10 may. However, it stabilizes the outcome of community detection by reassigning marginal observations or outliers to more relevant communities, which can significantly impact the accuracy and interpretation of statistical analysis.

Modalities optimization

Community detection using multimodal data reveals complex patterns from heterogeneous sources. However, the contribution of each modality to forming communities may vary, suggesting that a subset of modalities can maximize the quality of communities detected. Our toolbox offers the capability of optimizing the modalities by maximizing the silhouette score, a metric used to demonstrate the goodness of a clustering technique. The silhouette score evaluates the quality of clusters in unsupervised learning, specifically in clustering algorithms. It quantifies the degree of similarity of an object to its own cluster (cohesion) compared to other clusters (separation). Formally, for a given data point i, the silhouette score s(i) is defined as

where a(i) denotes the average distance between i and all other points within the same cluster, and b(i) represents the minimum average distance from i to points in a different cluster. The overall silhouette score is the mean of individual scores, ranging from −1 (indicating incorrect clustering) to 1 (indicating well-defined clusters), with values close to 0 signifying overlapping clusters.

The optimization module of MINT generates a list of all possible combinations of modalities. Subsequently, one of the community detection modules (e.g., SNF) is employed to detect communities in the data for each combination of modalities. The silhouette score for each combination is then calculated, where the attributes are derived from the combined multimodal data for the given modalities, and the labels are the communities assigned by the algorithm (e.g., SNF). The scores from all combinations are stored in an array and normalized, and the combination maximizing the silhouette score is proposed as the optimal set of modalities. MINT offers a unique optimization module that is implemented as a component in the community detection pipeline.

Statistics and reproducibility

In this study, independent-sample t-tests, chi-square tests and Whitney–Mann U tests were used to compute differences between communities in the variables of interest. These included age, sex, education, and APOE status, but also cognitive measurements such as the MMSE, MoCA, CDRSB, and ADAS13. In addition, subjects were compared in brain volume in the hippocampus, amyloid load using PET, and tau, ptau, and amyloid using CSF. These tests were carried out in MATLAB R2022b (MathWorks), R Studio (version 4.4.3), and SPSS 28 (IBM). Analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (p-corrected < 0.05).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

Multilayer Integration of Networks Toolbox (MINT) is a Python package developed by the C-BRAIN Lab at Stanford University. It streamlines the integration of multilayer networks for multimodal community detection, facilitating the identification of subtypes in complex datasets. MINT includes modules for data standardization, execution of SNF and GenLouvain algorithms, visualization of intermediate results, cross-validation techniques, and optimization of identified communities by selecting an optimal combination of modalities that maximizes the silhouette score. The MINT package is openly available at https://code.stanford.edu/cbrain/mint.

References

Wen, J. et al. Characterizing heterogeneity in neuroimaging, cognition, clinical symptoms, and genetics among patients with late-life depression. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 464–474 (2022).

García-Gutiérrez, M. S. et al. Biomarkers in psychiatry: concept, definition, types and relevance to the clinical reality. Front. Psychiatry 11, 527209 (2020).

Li, J., Xu, H., Yu, H., Jiang, Z. & Zhu, L. Multi-modal feature selection with anchor graph for alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 16, 1036244 (2022).

Zhang, C., Song, J., Zhu, X., Zhu, L. & Zhang, S. Hcmsl: Hybrid cross-modal similarity learning for cross-modal retrieval. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 17, 1–22 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Multi-graph based hierarchical semantic fusion for cross-modal representation. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), 1–6 (IEEE, 2021).

Li, J., Wu, L., Wen, G. & Li, Z. Exclusive feature selection and multi-view learning for alzheimer’s disease. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 64, 102605 (2019).

Sarraf, S. et al. Ovitad: Optimized vision transformer to predict various stages of alzheimer’s disease using resting-state fmri and structural mri data. Brain Sci. 13, 260 (2023).

Oliver, L. D. et al. Social cognitive networks and social cognitive performance across individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and healthy control participants. Biol. Psychiatry 6, 1202–1214 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 11, 333–337 (2014).

De Meo, P., Ferrara, E., Fiumara, G. & Provetti, A. Generalized Louvain method for community detection in large networks. In 2011 11th International Conference on Intelligent Systems Design and Applications, 88–93 (IEEE, 2011).

Rajmohan, R. & Reddy, P. H. Amyloid-beta and phosphorylated tau accumulations cause abnormalities at synapses of alzheimer’s disease neurons. J. Alzheimer’s. Dis. 57, 975–999 (2017).

Lambert, J.-C., Ramirez, A., Grenier-Boley, B. & Bellenguez, C. Step by step: towards a better understanding of the genetic architecture of alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2716–2727 (2023).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI) clinical characterization. Neurology 74, 201–209 (2010).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Wechsler, D. Wechsler memory scale-revised. Psychol. Corp. (1987).

Hughes, C. P., Berg, L., Danziger, W., Coben, L. A. & Martin, R. L. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry 140, 566–572 (1982).

Dubois, B. et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS–ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 6, 734–746 (2007).

Avelar-Pereira, B., Belloy, M. E., O’Hara, R., Hosseini, S. H. & Initiative, A. D. N. Decoding the heterogeneity of alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and progression using multilayer networks. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 2423–2432 (2023).

Perrin, R. J., Fagan, A. M. & Holtzman, D. M. Multimodal techniques for diagnosis and prognosis of alzheimer’s disease. Nature 461, 916–922 (2009).

Jones, D. et al. A computational model of neurodegeneration in alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 13, 1643 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Multimodal classification of alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage 55, 856–867 (2011).

Balsis, S., Benge, J. F., Lowe, D. A., Geraci, L. & Doody, R. S. How do scores on the adas-cog, mmse, and cdr-sob correspond? Clin. Neuropsychol. 29, 1002–1009 (2015).

Vogel, J. W. et al. Four distinct trajectories of tau deposition identified in alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 27, 871–881 (2021).

Killiany, R. J. et al. Use of structural magnetic resonance imaging to predict who will get alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 47, 430–439 (2000).

Ferreira, L. N. et al. Spatiotemporal data analysis with chronological networks. Nat. Commun. 11, 4036 (2020).

Genova, V. G., Giordano, G., Ragozini, G. & Vitale, M. P. An analytic strategy for data processing of multimode networks. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 18, 745–767 (2023).

Mucha, P. J., Richardson, T., Macon, K., Porter, M. A. & Onnela, J.-P. Community structure in time-dependent, multiscale, and multiplex networks. Science 328, 876–878 (2010).

Motschnig, N., Ramharter, A., Schweiger, O., Zabka, P. & Foerster, K.-T. On comparing and enhancing two common approaches to network community detection. In 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), 1–6 (IEEE, 2021).

Dao, V. L., Bothorel, C. & Lenca, P. Community structure: a comparative evaluation of community detection methods. Netw. Sci. 8, 1–41 (2020).

Jin, D. et al. A survey of community detection approaches: from statistical modeling to deep learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35, 1149–1170 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peter J. Mucha (Dartmouth College) for valuable discussions and feedback related to this work. This study was partly funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG073362 and R21AG064263). SMHH’s effort was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG073362, R01AG072470, R21AG064263, and R21AG073973). Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/ how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf. ADNI data collection and sharing was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: S.S. and B.A.-P. Formal analysis: S.S. and B.A.-P. Methodology: all authors. Funding acquisition: S.M.H.H. Investigation: S.S. and B.A.-P. Software: S.S. Visualization: S.S. and B.A.-P. Validation: S.S. and B.A.-P. Writing—original draft: S.S. and B.A.-P. Writing—review and editing: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Aaron P. Schultz and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Jasmine Pan and Aylin Bircan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarraf, S., Avelar-Pereira, B., Hosseini, S.M.H. et al. Multilayer Integration of Networks Toolbox (MINT). Commun Biol 8, 894 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08269-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08269-4