Abstract

The impact of dietary microorganisms on host microbiota is recognized, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. This study examined the effects of bamboo surface microbiota, including virulence factors, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and mobile genetic elements from different bamboo parts (leaves, shoots, and culms), on giant panda gut microbiota using three pairs of twins. Results showed that bamboo and fecal samples shared 1670 microbial species, with shoot surface microbiota contributing the highest proportion (21%, Bayesian source tracking) of contemporaneous gut microbiota, primarily by increasing abundances of Escherichia coli and ARGs. Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella enterica also showed high co-occurrence in both bamboo and fecal samples, indicating potential colonization. Additionally, Streptococcus suis, Acinetobacter, and Mycobacterium progressively declined in fecal samples as bamboo shoot intake increased, suggesting these microbes are likely transient. The findings emphasize the impact of foodborne microorganisms on the host and the importance of conservation management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interactions between the host and its gut microbiota play a pivotal role in mammalian health, nutritional metabolism and ecological function by facilitating food digestion, synthesizing essential metabolites, modulating immune responses and defending against pathogens1,2,3,4,5. Plant surface microbiota are considered a major exogenous source of gut microbes6, yet their specific functions within the host microbe ecological system remain unclear. On one hand, foodborne microorganisms may enter the host gastrointestinal tract directly through ingestion7,8; on the other hand, studies have shown that phyllosphere bacteria can be transferred to the host via skin contact and ultimately influence gut microbial communities9,10. Transient environmental microbes often lack adhesion factors and complex polysaccharide degradation capabilities, rendering them susceptible to clearance by host antimicrobial peptides or resident microbiota and resulting only in transient immune stimulation or limited protection11; in contrast, coevolved symbionts degrade recalcitrant polysaccharides to produce short chain fatty acids, induce regulatory T lymphocytes and suppress excessive inflammation, thereby maintaining microbiota homeostasis11,12. Moreover, foodborne transient taxa may disseminate antibiotic resistance genes to opportunistic pathogens via mobile genetic elements, posing a threat to host health13,14,15,16. However, research on the ecological functions and health impacts of foodborne microorganisms on host gut communities remains scarce17, necessitating systematic investigation of this potential ecological mechanism.

In investigations of how plant derived microbiota affect hosts, bamboo is particularly representative due to its unique characteristics. Serving as the primary dietary resource for species such as the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), the red panda (Ailurus fulgens) and bamboo lemurs (Prolemur and Hapalemur), bamboo exhibits pronounced chemical and morphological heterogeneity among its leaves, shoots and culms18. These differences render each tissue susceptible to colonization by environmental microorganisms from soil, air and water19, potentially resulting in markedly distinct surface microbial community compositions across these parts. Adult giant pandas, as highly specialized herbivores, allocate nearly half of their daily time to foraging20, and frequently rest within bamboo stands, often reclining directly on their bamboo feed under captive conditions21. These foraging behaviors and environmental contacts create extensive opportunities for both direct ingestion of and indirect transfer of microbes22,23. The intrinsic differences among bamboo parts, coupled with the intimate association between the giant panda and its bamboo diet, provide a robust experimental framework and an ideal model for investigating the influence of foodborne microbes on host gut microbiota composition and function24. However, despite the clear advantages of the bamboo model, systematic studies on the influence of bamboo associated microbiota on host gut microecology remain critically limited.

Although previous studies have explored the influence of foodborne microorganisms on host gut microbiota through short-term experiments or single food sources25,26, systematic assessments across diverse and long-term dietary regimes in wild non-model mammals remain scarce, thereby limiting our comprehensive understanding of the dynamic relationships among diet, host, and microbiota within natural ecosystems. To address this gap, we employ the giant panda as a model system, perform metagenomic and ecological analyses, and conduct an incremental bamboo shoot feeding experiment to investigate three key questions: first, to what extent do surface microorganisms from bamboo leaves, shoots, and culms migrate to and colonize the giant panda gut; second, whether microbial communities from different bamboo tissues differentially affect gut microbiota composition and function; and third, whether foodborne microorganisms can profoundly modulate ecological functions and host health through the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and pathogen virulence factors. This study systematically quantifies the migratory contributions and functional impacts of microbial communities associated with different bamboo tissues on the gut microbiota of giant pandas. It elucidates the ecological roles of bamboo-associated microbes and offers critical insights into food safety, species conservation, and health management. Moreover, it provides both theoretical and empirical foundations for understanding the dynamic interactions among diet, host, and microbiota within complex natural ecosystems.

Results

Dietary microbiota shapes host gut microbiota structure

Combined metagenomic analysis of surface microbiota from three bamboo parts and fecal samples from six giant pandas after consuming these parts identified 10870 microbial species, 1670 of which were shared between bamboo and feces, with Escherichia coli as the most abundant (Fig. 1a). Its relative abundance was highest in the Feces of Bamboo Shoot (FS) group (31.2%), followed by the Bamboo Shoot (BS) group (21.9%). The second most abundant species, Streptococcus alactolyticus, was enriched exclusively in three fecal groups, while it was barely detectable in three bamboo groups, except for a trace amount in the Bamboo Culm (BC) group (0.0015%) (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the dominant genera in the fecal groups, Streptococcus and Clostridium, were found in extremely low relative abundances in bamboo groups (Figure S1C). In contrast, Klebsiella, predominantly associated with bamboo, exhibited significantly higher relative abundance in bamboo groups compared to fecal groups (Figure S1C, P < 0.001, t-test). At the phylum level, Pseudomonadota accounted for 69.0% of the relative abundance in the BS group and 71.4% in the FS group. Bacillota was dominant in the Feces of Bamboo Leaf (FL) and Feces of Bamboo Culm (FC) groups, with relative abundances of 80.6% and 77.3%, respectively (Figure S1A). However, in the BL and BC groups, the relative abundance of Bacillota was only 5.6%. In the FS and BS groups, the relative abundances of Bacillota were 17.5% and 11.32%, respectively (Figure S1A). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) analysis at species, genus, and phylum levels revealed that the microbial community composition in bamboo shoot feces was more closely related to that of bamboo shoots (Figs. 1b, S1B and S1D), with no statistically significant differences observed between them (Padj = 0.07, PERMANOVA, Tables S1–S3). The Bray-Curtis distance-based cluster tree showed consistent results (Fig. 1c).

On average, 3.99% of the microbiota detected in the Bamboo Leaf (BL) group was also found in the FL group, as estimated using the SourceTracker2 software based on a Bayesian algorithm. Similarly, 21% of the microbiota identified in the BS group was also observed in the FS group, although this proportion varied considerably among samples (SD = 19.9%, range: 1.07%-58.55%). In contrast, less than 0.1% of microbiota from the BC group was shared, on average, with the FC group (Fig. 2).

The feces from Bamboo Leaf (a), Bamboo Culm (b), and Bamboo Shoot (c) are presented. Each pie chart represents a predicted sample, with differently colored segments indicating the proportion of microbiota originating from various sources. The section labeled “unknown” represents the proportion of microbiota whose sources could not be attributed to any food sample.

Differential abundance of key metabolic functions

Functionally, genes related to metabolic processes accounted for a substantially higher proportion than those associated with other cellular activities (Fig. 3a). Among these, the top three categories were Carbohydrate metabolism, Amino acid metabolism, and Energy metabolism, collectively comprising 25.98% of all annotated genes. The PCoA analysis at level 3 revealed significant distinctions between FL and FS, FC groups (Padj < 0.05, PERMANOVA, Figure S2A, Table S4). For specific functions, genes associated with Ribosome, ABC transporters, and Two-component systems were ranked in the top three for relative abundance in both the bamboo and fecal groups (Fig. 3b). Functional pathways Ko04112 (Cell cycle - Caulobacter) and Ko04212 (Longevity regulating pathway - worm) showed significantly higher relative abundance in the bamboo culm group compared to other groups in both feces and bamboo samples (Padj < 0.05, MetaGenomeSeq). Additionally, the relative abundance trends of Ko03010 (Ribosome) and Ko00500 (Starch and sucrose metabolism) were consistent across the three groups in both bamboo and fecal samples, with the bamboo leaf group showing the highest abundance and the bamboo shoot group the lowest (Fig. 3c).

Influence of foodborne pathogen virulence genes

At the level 2 of virulence factor database (Virulence factors of bacterial pathogens, VFDB), 726 types of VFs were annotated, with 483 in the BL group, 556 in the FL group, and 430 shared between them. Capsule, Trehalose-recycling ABC transporter (VF0842, a nutritional/metabolic factor), LPS (Lipopolysaccharide), and Pyrimidine biosynthesis ranked among the top five in abundance for both groups. The BS group contained 295 types, the FS group 639 types, and 291 types were shared, with high abundances of Capsule, LOS (Lipo-oligosaccharide), and LPS in both groups. The BC group contained 568 types, the FC group 515 types, and 437 were shared (Fig. 4a). PCoA analysis showed that the three bamboo groups clustered together, while the three fecal groups formed distinct clusters (Padj < 0.05, PERMANOVA, Figure S2B, Table S5). Capsule, LPS, and LOS were consistently abundant in bamboo and fecal samples. Additionally, Flagella ranked first in abundance in both BL and BC groups, but the primary factors potentially interacting with the host were Capsule, LOS, and LPS. Based on the annotation results from VFs unigenes alignment, it shows the distribution of unigenes related to Capsule in different microorganisms. The majority of these unigenes are attributed to E. coli (23.4%), followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae (5.6%). Additionally, unigenes related to LOS and LPS are also predominantly associated with E. coli (Supplementary Data 1).

Among the top 10 VFs in relative abundance, peritrichous flagella, associated with bacterial motility, were significantly more abundant in bamboo culms within the bamboo group (P < 0.01, t-test) but were predominantly found in bamboo shoots within the fecal group (Fig. 4b). The regulatory factor RegX3 showed significantly higher abundance in bamboo culms compared to bamboo shoots in the bamboo group, with a similar significant difference observed in the fecal group. However, for other VFs, such as flagella-associated proteins, trehalose recycling ABC transporter, and polysaccharide capsule-related immune modulation factors, no consistent patterns of variation were observed between bamboo and fecal samples under different dietary changes (Fig. 4b).

Pathogen–host interaction genes in foodborne microbiota

At level 3 of Pathogen–host interaction (PHI) database, 4702 genes were annotated, with 4039 in the BL group, 3432 in the FL group, and 3073 shared between them. The BS group contained 1814 genes, the FS group 2921 genes, and 1759 were shared. The BC group contained 3446 genes, the FC group 2195 genes, and 1978 were shared (Fig. 5a). PCoA analysis showed that the three bamboo groups clustered together, while the three fecal groups formed distinct clusters (Padj < 0.05, PERMANOVA, Figure S2C, Table S6).

The ubiquinol oxidase (complex III cytochrome bc1), ranked first in relative abundance in the BL and BS groups, was detected at extremely low levels in fecal samples, with a relative abundance of less than 0.001%. The atpA (ATP synthase subunit alpha) consistently ranked among the top five in bamboo samples across all three parts and ranked within the top 1% in relative abundance in fecal samples. The potA (ABC transporter ATP-binding protein for spermidine/putrescine transport), RpoB (beta-subunit of RNA polymerase), and rplN (50S ribosomal protein) were among the top 20 most abundant genes in both BL and FL groups. Notably, 9 of the 10 most abundant genes in fecal samples were also detected in bamboo samples. Among these, cab (Cysteine ATP-binding protein), oppD, and oppF (Oligopeptide transporter subunits that hydrolyze ATP to drive transport) ranked within the top 1% in both BC and BL groups. Additionally, clpB (Chaperone protein) ranked third in BC, 11th in BL, and ranked within the top 1% in BS. RpoB ranked first in BC and fifth in BL.

Cab, oppD, clpB, RpoB, and murA exhibited significant differences between bamboo shoots and bamboo culms (Fig. 5b, P < 0.05, t-test), with consistently higher relative abundance in bamboo culms. Furthermore, the phosphate import ATP-binding protein (PstB), rplN, and atpA showed consistent trends of significant differences (P < 0.05, t-test) across bamboo shoots, bamboo leaves, and bamboo culms, in both bamboo surface and fecal microbial communities (Fig. 5b and c).

Foodborne antibiotic resistance genes

Bamboo shoots carried significantly more antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) than bamboo leaves and culms (P < 0.05, t-test). A similar trend was observed in fecal groups, with feces from bamboo shoots showing higher ARG abundance compared to feces from other bamboo parts (P < 0.05, t-test). The bamboo shoot group also exhibited the highest diversity of ARG types, significantly greater than that of bamboo leaves (P < 0.05, t-test, Figure S3).

In the BL and FL groups, the vanY gene in the vanB cluster was more than 10% abundant, while the BS and FS groups had four identical ARGs in the top five by relative abundance, including Escherichia coli EF-Tu mutants and emrR. In the BC and FC groups, qacG gene abundance exceeded 20% (Fig. 6a). E. coli was the dominant contributor to ARGs, particularly in the SF group (31.2%) and FL group (12.1%), while Streptococcus alactolyticus dominated in the FC group (30.1%, Fig. 6b).

a Relative abundance of ARGs among different groups. b Contribution analysis of bamboo-derived ARGs to fecal samples, showing the abundance distribution of ARGs across different samples. Links connect ARGs to corresponding microbes, reflecting species-level microbial contributions. c Co-occurrence of dominant species-level microbes in fecal samples with ARG types and drug classes. d Co-occurrence pattern showing the correlations between ARGs and microbes in bamboo and fecal samples. Higher Person and Weight values indicate stronger correlations. Only significant correlations with P < 0.01 and r > 0.9 are displayed. Weight degree represents the sum of edge weights connected to a node, reflecting the strength of associations between nodes.

The microbiota in bamboo was annotated with ARGs from 9 phyla, 42 genera, and 43 species (Figure S4). Proteobacteria dominated at the phylum level, while Acinetobacter baumannii was the most abundant species, annotating 48 antibiotic resistance ontologys (AROs) (Supplementary Data 2). Major resistance mechanisms included antibiotic efflux, inactivation, and target alteration. Among the top 10 species-level microbiota in bamboo-derived fecal samples, 5 species coexisted with AROs (Fig. 6c). These ARGs were linked to 17 drug classes, with E. coli covering 14 classes. Klebsiella pneumoniae and Clostridium cuniculi were associated with aminoglycoside and glycopeptide antibiotics, respectively.

A correlation analysis revealed that Serratia marcescens and Escherichia albertii were the highest-weighted nodes in the ARG-microbiota network, while FosA2 and oqxA ranked highest in closeness centrality (Fig. 6d). The most abundant microorganisms, including E. coli, Streptococcus alactolyticus, and van genes, showed strong correlations, with vanY and vanT genes highly associated with Streptococcus species and vanW gene in Clostridium species, demonstrating their significant role in the microbiota network.

Impact of mobile genetic elements on gut microbiota dynamics

In the integron analysis, class 1 integrase genes (intI1) accounted for 91.69% of the total, while class 2 integrase genes (intI2) represented 3.53%. The primary source was Leclercia adecarboxylata (CP060824.1), contributing 4.11%, with a total of 273 intestinal microbial species involved. Among these, E. coli had the highest relative abundance (10.77%). In the FC group, E. coli (CP033158.1) was predominant (19.31%), while its proportion in the BC group was less than 1%. Integrons in the FS group were mainly derived from Enterobacter cloacae (14.19%), whereas E. coli dominated the FL group (46.23%) (Figure S5). For insertion sequences (ISs), 866 types were annotated, with ISSen9, ISKpn26, and TnAs3 being the most abundant, each with a relative abundance exceeding 1% (Figure S6). The primary source of IS was E. coli (13.34%). In the FC group, IS elements were mainly derived from E. coli and Streptococcus suis, while in the BC group, Acinetobacter baumannii and Acinetobacter lwoffii were the major contributors. Plasmid analysis revealed a total of 7320 annotated plasmids. Among them, Shinella sp. PSBB067 plasmid unnamed1 was the most abundant (4.78%, Figure S7). The plasmids in the FC group were primarily sourced from E. coli, showing significant differences compared to the BC group. In the FS and BS groups, plasmids from Klebsiella aerogenes and Klebsiella pneumoniae both had relative abundances exceeding 1%. In the FL and BL groups, Nocardia farcinica plasmid 2, Shinella sp. PSBB067, and Methylobacterium aquaticum plasmid pMaq22A were ranked as the top three contributors.

Verification of gut microbiota changes induced by bamboo shoot intake

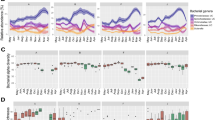

To verify the ecological shifts in gut microbiota and pathogen interactions mediated by microbes originating from bamboo, we conducted a feeding trial in which bamboo shoot supplementation gradually increased across four stages (FS1 to FS4). The relative abundance of Bacillota (Firmicutes) decreased from 57% to 16%, while Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria) increased from 17% to 56% (P < 0.05, t-test) (Figs. 7a, S8A). Random-forest analysis ranked this shift as the third most important change (Fig. 8a). The most notable transition occurred during the FS2 stage, when bamboo shoot supplementation began, characterized by a significant decrease in Streptococcus (P < 0.05) (Figs. 7b, S8B), and a significant increase in Escherichia and Lactococcus (P < 0.05) (Figure S8B). At the species level, E. coli increased significantly from FS1 to FS4 (P < 0.05), while Streptococcus alactolyticus and Streptococcus lutetiensis decreased (P < 0.05) (Figs. 7c, S8C). PCoA based on unigenes showed a clear transition pattern, except in the FS2 group (Fig. 7d), with significant differences in sample distribution confirmed by Bray-Curtis-based PERMANOVA (P = 0.001). Specifically, significant differences were observed between F1 and F2, as well as F4 (Padj < 0.05, Table S7).

Species that most represent the changes in microbiota at phylum level (a), genus level (b), and species level (c), identified by random forest analysis under different bamboo shoot intake levels. d Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Level 3 functional categories, (e) Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) Level 2 functional categories, (f) Pathogen-Host Interaction (PHI) Level 3 functional categories, (g) Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD). The x-axis represents the decrease in prediction accuracy of the random forest model, with larger values indicating higher variable importance.

Random-forest analysis also highlighted changes in microbial functions due to bamboo shoot intake. In the KEGG database, Cell cycle –Caulobacter was the most important function (Fig. 8d). In the VFDB, Urease and LOS ranked as the top two functions (Fig. 8e), with the latter also more abundant in bamboo surface microbiota. PHI database analysis showed that UreA, fruA1, and cspE were the most important functions (Fig. 8f). Moreover, bamboo shoot intake significantly increased both the diversity and abundance of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), particularly E. coli EF-Tu mutants (Pulvomycin-resistant) and emrR (Fig. 8g). These ARGs were enriched on the bamboo surface, with ISs, particularly ISSen9, were most abundant in the FS4 group (Figures S9, and S10).

Discussion

This study elucidates the significant impact of foodborne microorganisms from different bamboo parts (shoots, leaves, and culms) on the gut microbiota of giant pandas through metagenomic analysis. Among the microbial taxa, Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibited the highest co-occurrence between bamboo samples and the corresponding fecal samples. Notably, the surface microbiota of bamboo shoots showed the greatest compositional similarity to the fecal microbiota, compared with leaves and culms. Moreover, the relative abundances of E. coli and Salmonella enterica in feces increased significantly with higher bamboo shoot intake, suggesting that these species may have colonized the host gut and possess the capacity for long-term persistence. In contrast, genera such as Dechloromonas, Aeromonas, Streptomyces, and Robertmurraya, which were abundant in bamboo but nearly undetectable in fecal samples, as well as Streptococcus suis, Acinetobacter baylyi, Acinetobacter, Mycobacterium, and Limosilactobacillus, which were progressively depleted in the gut with increasing bamboo shoot consumption, may represent typical transient microbes. Bamboo shoots also harbored significantly higher levels of pathogen virulence factors (VFs) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) compared to other bamboo parts, and these patterns were mirrored in the fecal microbiome. Furthermore, consistent patterns of pathogen–host interaction (PHI) genes observed in both bamboo shoots and feces suggest a direct influence of shoot-derived microorganisms on the host gut microbiota. Collectively, these findings highlight the contribution of bamboo surface microbiota to the composition of panda gut microbiota and offer insights into the interaction between diet and host microbial ecology.

Similar to how fruit and vegetable associated microbes contribute to human gut diversity and metabolism6, bamboo-derived microorganisms in giant pandas are associated with starch and sucrose metabolism, which are crucial for food digestion. Host factors such as age, diet, and plant diversity also affect microbial abundance, highlighting diet as a major driver of gut microbiome composition25,26. Previous studies have demonstrated that factors like season and altitude influence microbial communities in bamboo leaves, affecting the gut microbiomes of both insects and herbivores8,22,27,28. Consistent with these findings, our study revealed significant differences in microbial communities across different bamboo parts, with notable shifts in antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and pathogen virulence genes.

Bamboo shoots play a critical role in the spread of ARGs, with significantly higher levels of ARGs compared to bamboo leaves and culms. Fecal samples also show a correlation with bamboo shoot intake, suggesting bamboo shoots influence the gut microbiota’s resistance characteristics. Co-occurrence analysis revealed a strong relationship between microbial species like E. coli and Streptococcus alactolyticus in bamboo shoots and feces, particularly with ARGs related to fluoroquinolones and glycopeptides. This suggests that bamboo surface microorganisms, especially from bamboo shoots, contribute to ARG dissemination within the gut microbiota and participate actively in microbial network interactions29. Additionally, the soil’s microbial composition, which interacts with plant roots, impacts the above-ground plant microbiome and, consequently, the herbivore gut microbiota30. Substrate selection by plant roots alters the microbial and metabolic content of above-ground tissues, influencing herbivore gut microbiomes8. Therefore, bamboo shoot microorganisms significantly affect panda gut microbiota structure and function, with implications for panda health and resistance characteristics.

We observed significant variations in mobile genetic elements (MGEs) between different bamboo parts and their corresponding fecal samples. MGEs, encoding ecologically important traits, facilitate the horizontal transfer of ARGs and may compromise antibiotic efficacy31,32. In all samples, the integron integrase gene (intI) was predominantly intI1, with E. coli constituting the primary source in the FL group and Enterobacter cloacae in the FS group. This suggests that the consumption of different bamboo parts may influence the types and functions of MGEs by altering gut microbiota composition. In contrast, minimal insertion sequences (ISs) were found in the BS group, possibly reflecting lower selective pressure on MGE mobility from bamboo shoots33. Plasmid analysis revealed that plasmids in the FL and BL groups were primarily associated with Shinella sp. and Methylobacterium aquaticum, while the FC group harbored plasmids mainly originating from E. coli. The transfer of ARGs via plasmids is typically mediated by MGEs, which can facilitate the replication or transfer of ARGs between DNA molecules34. These findings suggest that bamboo leaves may harbor a more stable microbial and plasmid composition, while bamboo culms are more susceptible to environmental or host influences.

Bamboo-derived pathogen virulence genes, including capsules, lipooligosaccharide (LOS) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), profoundly influence the gut microbiota of giant pandas. Capsules facilitate bacterial adhesion to abiotic surfaces and to other bacteria, enhancing colonization across diverse ecological niches and promoting biofilm formation35. In invasive infections, capsule–host immune interactions are pivotal in determining disease outcomes36. Beyond passively resisting host defenses, bacterial capsules actively modulate immune responses by directly influencing cytokine release and disrupting coordinated cell-mediated immunity37. The principal virulence factor of Klebsiella pneumoniae is the capsular polysaccharide (CPS), which enhances bacterial resistance to phagocytosis and serum-mediated killing38,39,40. LOS, a major immunogen, promotes invasion and inflammatory signaling via the platelet activating factor receptor, with phase variable expression facilitating immune evasion and host adaptation41. LPS, an essential outer membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria, mediates serum killing and phagocytosis and may enhance invasion through CFTR binding, potentially leading to chronic infection if clearance fails42. Furthermore, functional genes such as PstB, rplN and atpA exhibited consistent differential abundance between bamboo parts and fecal samples, implicating roles in phosphate transport, protein synthesis and energy metabolism43,44. In this study, we observed that both E. coli and K. pneumoniae from bamboo shoots-whose surface microbiota closely mirror that of panda feces-were significantly enriched in capsule-related genes, suggesting that these species may leverage capsule-mediated mechanisms to enhance colonization and immune evasion in the panda gut, thereby exerting a lasting influence on host intestinal ecosystem stability.

We validated our hypothesis through a bamboo shoot feeding experiment, demonstrating that dietary intake significantly reshapes the gut microbiota composition of giant pandas. Bamboo shoot consumption increased the relative abundance of E. coli expanded the diversity and abundance of ARGs, particularly those associated with E. coli, such as EF-Tu mutants. These ARGs were enriched on bamboo shoot surfaces, indicating their contribution to the gut microbiota’s ARG pool. Additionally, bamboo shoot intake altered the functional characteristics of the gut microbiota, with random forest analysis revealing urease and LOS as key VFs. PHI analysis identified UreA, fruA1, and cspE as key functional genes associated with gut microbiota adaptability. KEGG analysis revealed alterations in cell cycle-related pathways, suggesting that bamboo shoot consumption may influence gut microbial proliferation and division. The feeding experiment revealed that dietary shifts in gut microbial ecology and host-microbe interactions drive the adaptive evolution of the giant panda gut microbiota, impacting health, adaptability, and resistance gene transmission.

Although this study indicates that dietary microbiota may modulate host health and adaptability through ARGs and MGEs, the relatively limited sample size might constrain the statistical power to detect subtle dietary effects. To address this limitation, we pooled multiple bamboo subsamples for each bamboo part at every feeding stage, mixing batches of shoots, leaves, or culms before sampling to improve representativeness. In addition, we collected four additional sets of samples during the bamboo shoot feeding phase to facilitate comparative analyses and enhance the reliability of our results. Nevertheless, future studies are needed to validate these findings in larger populations across multiple conservation centers. Furthermore, more experimental research is necessary to elucidate the mechanisms by which dietary microbiota influence host health, particularly regarding immune regulation and horizontal gene transfer45,46,47. This highlights the importance of food sources on host gut health. Future studies should combine functional experiments with long-term field observations to examine dietary microbiota’s role in host adaptive evolution. This research bridges gaps in understanding dietary microbiota in non-model mammals and provides insights into how bamboo microbiota regulate giant panda gut microbiota and resistance genes, offering perspectives on diet–microbiota–host health relationships and laying a foundation for wildlife conservation and microbiota-based health interventions48,49.

Conclusions

This study systematically explores the influence of bamboo surface microbiota on the composition and functionality of the giant panda gut microbiota, revealing how dietary microbes, carrying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), contribute to host health and adaptability. Our findings demonstrate significant differences in microbial community composition, functional properties, and MGE diversity across bamboo parts (leaves, shoots, and culms) and their corresponding fecal samples. MGEs in bamboo leaves were predominantly derived from Shinella sp. and Methylobacterium aquaticum, indicating high stability, whereas microbial communities and plasmid compositions in bamboo culms were more susceptible to environmental or host factors. Furthermore, bamboo shoot intake notably altered gut microbiota structure, increasing the abundance of E. coli and its associated ARGs, emphasizing bamboo shoots as an external reservoir for resistance genes. Importantly, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella enterica—three species showing high co-occurrence between bamboo and fecal samples and exhibiting increased abundance with higher bamboo shoot intake - are likely candidates for successful colonization in the panda gut, with potential for long-term persistence. Pathogen VFs (e.g., capsule, LOS, and LPS) on bamboo surfaces and key functional genes in the gut (e.g., urease and cspE) were closely linked to host immune modulation and metabolic processes. In summary, this study offers a comprehensive view of the relationship between bamboo surface microbiota and giant panda gut ecology, clarifies the interactions among diet, microbes, and host health, and establishes a scientific basis for wildlife conservation and microbiota-based health interventions.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and ethical approval

This study was conducted at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding using three pairs of healthy, non-estrous, non-pregnant, and non-lactating giant pandas (two females and four males). No antibiotics were administered in the two months prior to the study. Fecal samples were collected after 30 days of feeding on bamboo shoots (Phyllostachys violascens, FS group), bamboo culms (Pleioblastus amarus, FC group), and bamboo leaves (Phyllostachys bissetii, FL group). All fecal samples were collected within 10 minutes of defecation, placed into sterile sampling bags, and a total of 18 fecal samples were obtained.

During the same feeding periods, bamboo samples were collected three times for each diet: bamboo shoots (BS group, corresponding to FS), bamboo culms (BC group, corresponding to FC), and bamboo leaves (BL group, corresponding to FL). Sterile cotton swabs were used to wipe the surface of the bamboo. Each swab was bent at a 45-degree angle and gently swiped across the bamboo surface with consistent pressure, ensuring that sampling areas did not overlap. For each sampling event, 2–3 swabs were collected, placed into separate sterile tubes, and tightly sealed. In total, nine bamboo samples were obtained. All collected samples were stored at -80°C until further processing.

The study followed ethical guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (Approval No. 2018019). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Fecal sample processing, DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

Fecal samples were processed according to previous studies23,24. Each fecal sample was suspended in 500 mL of sterile 0.05 M PBS (pH 7.4) and thoroughly mixed by vortexing. Large plant particles were removed by filtration, and the suspension was centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min to pellet coarse debris. This step was repeated twice, and the resulting supernatant was collected. The supernatant was then washed three times with 20 mL of sterile PBS by centrifugation at 9000 × g for 4 minutes each time. After the final wash, the pellet was resuspended in 10 mL PBS, aliquoted into 1 mL portions, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. DNA extraction was performed using the QIAamp® DNA Stool Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was assessed using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the concentration was adjusted to 50 ng/μL for downstream sequencing.

For shotgun metagenomic sequencing, 1 μg of genomic DNA from each sample was fragmented to approximately 350 bp using a Covaris ultrasonicator. Library preparation included end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, purification, and PCR amplification. The constructed libraries were preliminarily quantified using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer and diluted to 2 ng/μL. Library insert sizes were evaluated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Once the insert sizes met the expected range, the effective concentrations of the libraries were accurately quantified using quantitative PCR (qPCR), ensuring that only libraries with effective concentrations above 3 nM were used. Libraries that passed quality control were pooled according to their concentrations and required sequencing depth. Paired-end 150 bp sequencing (PE150) was then performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform.

Sequence processing and metagenome assembly

The raw sequencing data were preprocessed to obtain the effective data (clean data) for subsequent analysis. Data preprocessing was performed using the fastp tool (v.0.23.1), with the following steps: a) If any sequencing reads contained adapter sequences, the corresponding paired reads were removed; b) If the number of low-quality bases (Q ≤ 5) in any sequencing read exceeded 50% of the total bases in that read, the corresponding paired reads were removed; c) If the N base content in any sequencing read exceeded 10% of the total bases, the corresponding paired reads were removed. Additionally, if host contamination was present in the samples, reads originating from the host were filtered by aligning with the host sequences using Bowtie2 software (v.2.2.4). The Bowtie2 alignment parameters were: --end-to-end, --sensitive, -I 200, -X 40050.

The preprocessed clean data were assembled using MEGAHIT software (v.1.2.9) with the preset parameter --presets meta-large. During the assembly process, scaffolds were broken at N positions to generate N-free scaftigs51.

Through metagenomic sequencing, an average of 1,326,881 genes (SD = 121,043) were obtained from the bamboo samples, with no significant differences between the different parts (bamboo culm, bamboo shoot, bamboo leaf) (Figure S11). In contrast, the fecal samples yielded an average of 447,431 genes (SD = 395,046), with a significantly higher number of genes in the bamboo shoot feces compared to the other two groups (P < 0.01).

Gene prediction and abundance analysis

Open Reading Frame (ORF) prediction was carried out using MetaGeneMark (http://topaz.gatech.edu/GeneMark/) on scaftigs (≥500 bp) from each sample. Results with predicted ORF lengths shorter than 100 nt were filtered out, and the analysis was performed with the default parameters50,52. Subsequently, the predicted ORFs were dereplicated using CD-HIT software (v. 4.5.8) to generate a non-redundant initial gene catalogue53. The parameters used were: -T 6 -G 0 -aS 0.9 -g 1 -d 0 -c 0.95 -n 5 -M 8000. The non-redundant genes were defined as contiguous gene coding sequences with the following parameters: -c 0.95, -G 0, -aS 0.9, -g 1, -d 054,55.

Next, the clean data from each sample were aligned to the initial gene catalogue using Bowtie2 software (v. 2.2.4). The number of reads aligned to each gene was counted using the parameters: --end-to-end, --sensitive, -I 200, -X 40056. Genes with ≤2 reads in any sample were filtered out54, generating the final gene catalogue (unigenes) for further analysis. Gene abundance in each sample was calculated based on the number of reads aligned to each gene and gene length57.

Taxonomic and functional annotation with gene count analysis

We used DIAMOND software (v. 2.1.6) to align unigenes against the Micro_NR database (Version: 2023.03) to identify microbial sequences, with parameters set as -p 4 -e 1e-5 -k 5058. For each sequence, alignments with e-values ≤ the minimum e-value × 10 were selected. Since each sequence may have multiple hits, the Lowest Common Ancestor (LCA) algorithm (integrated into MEGAN software) was applied to determine the taxonomic annotation59. Based on LCA annotations and gene abundance tables, we calculated the abundance and gene counts at various taxonomic levels for each sample. Species abundance was computed as the sum of the abundances of all genes annotated to that species, while the gene count was the number of genes with non-zero abundance annotated to the species50.

Additionally, unigenes were aligned against the KEGG database (Version: 2023.02)60 for functional categorization using DIAMOND with parameters -p 4 -e 1e-5 -k 50 --id 30 -sensitive61. The virulence factor database (VFDB; Virulence Factors of Bacterial Pathogens), originally developed for predicting VFs associated with human diseases62, has in recent years also been applied to studies in dairy cattle63, golden snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana)64, giant pandas65, and various other animal and plant species66,67. In this study, the VFDB (http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) was employed to preliminarily identify bacterial VFs present on bamboo surfaces and in panda fecal samples. In addition, we used the Pathogen–Host Interactions Database (PHI-base; http://www.phi-base.org/index.jsp) to analyze pathogen–host interactions and assess the effects of gene mutations on pathogenicity and resistance. PHI-base provides manually curated genes from fungal, bacterial, and protist pathogens that have been experimentally verified to possess important roles in pathogenicity, virulence, and/or effector functions across diverse host species, including animals and plants68. For each sequence, the best alignment based on the highest score was used for downstream analyses69. Using the annotation results and gene abundance tables, we determined relative abundances across functional levels and compiled gene count tables at different functional categories50. Functional gene counts were calculated as the number of genes with non-zero abundance associated with a specific function. Finally, gene abundance tables at various taxonomic and functional levels were used for gene count statistics and Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA).

Antibiotic resistance gene annotation and mobile genetic element analysis

To investigate the genetic basis of antibiotic resistance and how bacteria resist antibiotics, we utilized the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD, https://card.mcmaster.ca/). The Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) software (v.6.0.2) was used to align unigenes to the CARD database (https://card.mcmaster.ca/) with its built-in BLAST, using a default e-value threshold of <1e-3070,71. Based on RGI alignment results and unigene abundance data, the relative abundance of each antibiotic resistance ontology (ARO) was calculated. ARO abundance data were further visualized through bar charts, heatmaps, and circle plots. Differential abundance analysis, ARO taxonomic assignments, and resistance mechanisms were analyzed among groups.

To explore the correlation between resistance genes and microbes, we performed network analyses using Pearson correlation coefficients and centrality indices. Co-occurrence networks were visualized, and centrality metrics were calculated, including closeness centrality (average inverse shortest path to other nodes), betweenness centrality (frequency of a node acting as a bridge), and eigenvector centrality (node connectivity to high-centrality nodes).

For horizontal gene transfer and its role in resistance gene dissemination, we annotated Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) using the Mobile Genetic Elements Database. Unigenes were aligned against databases for insertion sequences (ISfinder), integrons (Integrall), and plasmids. The abundance and functions of annotated genes were visualized using circos and bar charts72.

Assessing species contributions to panda fecal resistance genes

To assess the contributions of bamboo-associated species to resistance genes in panda fecal samples, we first calculated the relative abundance of resistance genes in each sample based on unigene abundance data. Using the R package reshape2 (v.1.4.3), resistance gene abundance and species data were integrated for further analysis. Associations between resistance genes and microbial species were examined using the R package vegan (v.2.6.4) to determine the contribution of each species to the abundance of resistance genes. The relationships between species and functional categories were analyzed to quantify the specific contributions of species to antibiotic resistance functions. Visualizations of species contributions and their roles in resistance functions were generated using the R package ggplot2 (v.3.5.1).

Panda fecal microbial source tracking

To investigate the microbial origins in panda fecal samples, we used the Bayesian-based tool SourceTracker2 (v. 2.0.1) for microbial source tracking. The SourceTracker model infers the proportional contributions of bacterial sources from multiple known environments to a given recipient environment using deep-sequencing marker gene libraries (e.g., 16S rRNA genes)73. Recent advances have extended SourceTracker’s applicability to shotgun metagenomic libraries for predicting source composition74. This method estimates the contribution of each source to the recipient samples by matching microbial community data between sources and sinks. Each predicted sample (sink) is visualized as a pie chart, with different colored segments representing microbial contributions from various sources. Known source samples contribute relative proportions expressed as percentages, while the “unknown” source reflects the unassignable portion.

Bamboo shoot increment feeding validation experiment

To validate the bamboo-derived microbiota-mediated changes in gut microbial ecology and pathogen interactions, we conducted a food overload experiment with sampling during the annual overfeeding period. Given the giant panda’s pronounced preference for bamboo shoots, which are prioritized when available, bamboo shoots were selected as the focus of this study. Six adult giant pandas (1:1 sex ratio) were subjected to a four-phase feeding regimen with incremental bamboo shoot supplementation. The actual feeding amounts were set at 0 kg, 20 kg, 40 kg, and ad libitum (>40 kg) per day, with each phase lasting 15 days. Throughout the experiment, standard dietary components, including panda cakes and apples, were maintained. A total of 24 fecal samples were collected for metagenomic sequencing, functional species analysis, and resistance gene analysis, employing the same methods as previously described. This experiment aimed to validate the impact of bamboo components, particularly bamboo shoots, on the gut microbiota of pandas, with a focus on changes in microbial community structure, functional dynamics, and pathogen interactions.

Statistics and reproducibility

To visualize changes in microbial abundance, the top 20 species were selected and their abundances normalized. ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to analyze differences in unigenes across groups. Bray-Curtis distance clustering was applied to construct sample dendrograms, and PCoA was performed on abundance tables using the ade4 (v.1.7-22) package in R (v.4.4.2). Differences among groups were assessed using PERMANOVA (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities, implemented in the adonis2 function of the vegan R package (v.2.6.8). Both global and pairwise PERMANOVA tests were conducted to evaluate overall group effects and pairwise differences, respectively. Pairwise comparisons were carried out using a custom R function, with significance determined by 999 permutations. Further, differences were evaluated using ANOSIM analysis and intergroup differential species analysis via the MetaGenomeSeq package (v.1.48.1) in R. To explore the relationships between microbes and resistance genes, gut microbiota, antibiotic resistance genes, and drug class categories were annotated and visualized using the NetworkD3 package (v.0.4) in R to generate Sankey diagrams. Differential abundance of VFDB Level 2 and Level 3 pathogen–host interaction (PHI) genes was assessed using t-tests between bamboo parts and their corresponding fecal samples. Similarly, microbial composition differences in the bamboo shoot increment experiment were analyzed using t-tests. P values for all multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method75.

To identify the most important microbes and resistance genes in the bamboo shoot increment experiment, random forest analysis was conducted using the randomForest package in R (v.4.7-1.2). Prior to analysis, leave-one-out 10-fold cross-validation was performed using the caret package in R to determine the number of features considered at each split. Optimal mtry parameters were selected based on accuracy and Kappa values. To optimize the ntree parameter of the random forest model, the impact of tree number on model error (misclassification rate) was evaluated, with convergence trends assessed. The maximum tree number was set at 5000, and cumulative error was recorded for each tree. Error rate trends were plotted against ntree increases, with the tree number at convergence selected as the final parameter value76.

We collected samples from three bamboo parts: shoots, leaves, and stems, with n = 3 biological replicates for each part. During each bamboo feeding period, fecal samples were collected from 6 giant pandas. In the bamboo shoot increment experiment, samples were collected at 4 stages, with fecal samples from 6 giant pandas at each stage.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw data and analysis code for this study are available on GitHub at https://github.com/yanyanyanyanyan1/Bamboo-Diet-Alters-Panda-Microbiota and in the supplementary files. The source data for each figure can be identified and downloaded based on the file names indicated on GitHub. The metagenomic datasets generated in this study are publicly available in the NCBI database. Specifically, the metagenomic data of surface-associated microorganisms from nine different bamboo parts, comprising nine samples, are accessible under BioProject accession number PRJNA1218279. Additionally, the raw metagenomic sequencing data of 18 fecal samples collected from giant pandas after feeding on different bamboo parts have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA1218280. Furthermore, the metagenomic data of 24 samples collected across four stages of bamboo shoot consumption are available under BioProject accession number PRJNA1218281. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for the random forest analysis and PERMANOVA analysis is available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1544160677.

References

Shapira, M. Gut microbiotas and host evolution: scaling up symbiosis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 539–549 (2016).

Weiss, A. S. et al. Nutritional and host environments determine community ecology and keystone species in a synthetic gut bacterial community. Nat. Commun. 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40372-0 (2023).

Samulenaite, S. et al. Gut microbiota signatures of vulnerability to food addiction in mice and humans. Gut 73, 1799–1815 (2024).

Dethlefsen, L., McFall-Ngai, M. & Relman, D. A. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature 449, 811–818 (2007).

Robinson, J. M., Wissel, E. F. & Breed, M. F. Policy implications of the microbiota-gut- brain axis. Trends Microbiol 32, 107–110 (2024).

Wicaksono, W. A. et al. The edible plant microbiome: evidence for the occurrence of fruit and vegetable bacteria in the human gut. Gut Microbes 15, 2258565 (2023).

Li, J. et al. The functional microbiota of on- and off-year moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) influences the development of the bamboo pest Pantana phyllostachysae. BMC Plant Biol. 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03680-z (2022).

Yuan, J. et al. Growth substrates alter aboveground plant microbial and metabolic properties thereby influencing insect herbivore performance. Science China Life Sci. 66, 1728–1741 (2023).

Mhuireach, G. Á. et al. Temporary establishment of bacteria from indoor plant leaves and soil on human skin. Environ. Microbiome 17, 61 (2022).

Chen, Y. E., Fischbach, M. A. & Belkaid, Y. Skin microbiota–host interactions. Nature 553, 427–436 (2018).

Ballal, S. A., Gallini, C. A., Segata, N., Huttenhower, C. & Garrett, W. S. Host and gut microbiota symbiotic factors: lessons from inflammatory bowel disease and successful symbionts. Cell. Microbiol. 13, 508–517 (2011).

Zhang, C. et al. Ecological robustness of the gut microbiota in response to ingestion of transient food-borne microbes. ISME J. 10, 2235–2245 (2016).

Guo, W. et al. The carnivorous digestive system and bamboo diet of giant pandas may shape their low gut bacterial diversity. Conserv. Physiol. 8. https://doi.org/10.1093/conphys/coz104 (2020).

Kumar, K., Gupta, S. C., Baidoo, S. K., Chander, Y. & Rosen, C. J. Antibiotic Uptake by Plants from Soil Fertilized with Animal Manure. J. Environ. Qual. 34, 2082–2085 (2005).

Karkman, A., Pärnänen, K. & Larsson, D. G. J. Fecal pollution can explain antibiotic resistance gene abundances in anthropogenically impacted environments. Nat. Commun. 10, 80 (2019).

Devirgiliis, C., Barile, S. & Perozzi, G. Antibiotic resistance determinants in the interplay between food and gut microbiota. GENES NUTRITION 6, 275–284 (2011).

Serrano, K. & Bezrutcyzk, M. Genome to gut: crop engineering for human microbiomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 132–132 (2023).

Zhao, W. Q. et al. Anatomical mechanisms of leaf blade morphogenesis in Sasaella kogasensis ‘Aureostriatus’. Plants 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13030332 (2024).

Yan, Z. et al. The impact of bamboo consumption on the spread of antibiotic resistance genes in giant pandas. Vet. Sci. 10, 630 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. A diet diverse in bamboo parts is important for Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) metabolism and health. Sci. Rep. 7, 3377 (2017).

Nie, Y. et al. Giant pandas are macronutritional carnivores. Curr. Biol. 29, 1677–1682.e1672 (2019).

Long, J. et al. Environmental factors influencing phyllosphere bacterial communities in giant pandas’ staple food bamboos. Front. Microbiol. 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.748141 (2021).

Yan, Z. et al. Consuming different structural parts of bamboo induce gut microbiome changes in captive giant pandas. Curr. Microbiol. 78, 2998–3009 (2021).

Yan, Z. et al. Functional responses of giant panda gut microbiota to high-fiber diets. Ursus 2024, 1–9 (2024).

David, L. A. et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014).

Johnson, A. J. et al. Daily sampling reveals personalized diet-microbiome associations in humans. Cell Host Microbe 25, 789–802.e785 (2019).

Kang, L. et al. Giant pandas’ staple food bamboo phyllosphere fungal community and its influencing factors. Front. Microbiol. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1009588 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Diversity, functions, and antibiotic resistance genes of bacteria and fungi are examined in the bamboo plant phyllosphere that serve as food for the giant pandas. Int. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10123-024-00583-x (2024).

Deng, F. et al. A comprehensive analysis of antibiotic resistance genes in the giant panda gut. Imeta 3. https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.171 (2024).

Sessitsch, A. et al. Microbiome interconnectedness throughout environments with major consequences for healthy people and a healthy planet. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 87, e00212–e00222 (2023).

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O. & Toussaint, A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Gu, A. Z., He, M., Li, D. & Chen, J. Subinhibitory concentrations of disinfectants promote the horizontal transfer of multidrug resistance genes within and across genera. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 570–580 (2017).

Noel, H. R., Petrey, J. R. & Palmer, L. D. Mobile genetic elements in Acinetobacter antibiotic-resistance acquisition and dissemination. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1518, 166–182 (2022).

Wang, Y. & Dagan, T. The evolution of antibiotic resistance islands occurs within the framework of plasmid lineages. Nat. Commun. 15, 4555 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Paeoniflorin reduce luxS/AI-2 system-controlled biofilm formation and virulence in Streptococcus suis. Virulence 12, 3062–3073 (2021).

An, H. et al. Functional vulnerability of liver macrophages to capsules defines virulence of blood-borne bacteria. J. Exp. Med. 219. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20212032 (2022).

Cress, B. F. et al. Masquerading microbial pathogens: capsular polysaccharides mimic host-tissue molecules. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 38, 660–697 (2014).

Rendueles, O. Deciphering the role of the capsule of Klebsiella pneumoniae during pathogenesis: a cautionary tale. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 883–888 (2020).

Opoku-Temeng, C., Kobayashi, S. D. & DeLeo, F. R. Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule polysaccharide as a target for therapeutics and vaccines. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 17, 1360–1366 (2019).

Paczosa, M. K. & Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: going on the offense with a strong defense. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 629–661 (2016).

Mandrell, R. E. & Apicella, M. A. Lipo-oligosaccharides (LOS) of mucosal pathogens: molecular mimicry and host-modification of LOS. Immunobiology 187, 382–402 (1993).

Wang, X. & Quinn, P. J. Lipopolysaccharide: biosynthetic pathway and structure modification. Prog. Lipid Res. 49, 97–107 (2010).

Schurdell, M. S., Woodbury, G. M. & McCleary, W. R. Genetic evidence suggests that the intergenic region between pstA and pstB plays a role in the regulation of rpoS translation during phosphate limitation. J. Bacteriol. 189, 1150–1153 (2007).

Sirichoat, A. et al. Phenotypic characteristics and comparative proteomics of Staphylococcus aureus strains with different vancomycin-resistance levels. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 86, 340–344 (2016).

Hehemann, J.-H. et al. Transfer of carbohydrate-active enzymes from marine bacteria to Japanese gut microbiota. Nature 464, 908–912 (2010).

Sommer, F. & Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota — masters of host development and physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 227–238 (2013).

Larsson, D. G. J. & Flach, C.-F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 257–269 (2022).

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K. & Knight, R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220–230 (2012).

Foster, K. R., Schluter, J., Coyte, K. Z. & Rakoff-Nahoum, S. The evolution of the host microbiome as an ecosystem on a leash. Nature 548, 43–51 (2017).

Karlsson, F. H. et al. Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat. Commun. 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2266 (2012).

Nielsen, H. B. et al. Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 822 (2014).

Sunagawa, S. et al. Ocean plankton. Structure and function of the global ocean microbiome. Science 348, 1261359 (2015).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Zeller, G. et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10, 766 (2014).

Qin, N. et al. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 513, 59–64 (2014).

Qin, J. et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 (2010).

Cotillard, A. et al. Dietary intervention impact on gut microbial gene richness. Nature 500, 585–588 (2013).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59 (2015).

Huson, D. H., Mitra, S., Ruscheweyh, H. J., Weber, N. & Schuster, S. C. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 21, 1552–1560 (2011).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 457–462 (2016).

Feng, Q. et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Nat. Commun. 6, 6528 (2015).

Yang, J., Chen, L., Sun, L., Yu, J. & Jin, Q. VFDB 2008 release: an enhanced web-based resource for comparative pathogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D539–D542 (2008).

Zhuang, Y. et al. Metagenomics reveals the characteristics and potential spread of microbiomes and virulence factor genes in the dairy cattle production system. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 136005 (2024).

Shidan, Z. et al. First report of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from a healthy captive sichuan golden snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in China. Microb. Pathog. 195, 106907 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. The giant panda gut harbors a high diversity of lactic acid bacteria revealed by a novel culturomics pipeline. mSystems 9, e00520–e00524 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Characterization and the first complete genome sequence of a novel strain of Bergeyella porcorum isolated from pigs in China. BMC Microbiol 24, 214 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Fermentation broth from fruit and vegetable waste works: Reducing the risk of human bacterial pathogens in soil by inhibiting quorum sensing. Environ. Int. 188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108753 (2024).

Urban, M. et al. PHI-base - the multi-species pathogen-host interaction database in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D826–d838 (2025).

Backhed, F. et al. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 17, 852 (2015).

Jia, B. et al. CARD 2017: Expansion and Model-centric Curation of the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (Oxford University Press, 2017).

McArthur, A. G. et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357 (2013).

Arkhipova, I. R. & Rice, P. A. Mobile genetic elements: in silico, in vitro, in vivo. Mol. Ecol. 25, 1027–1031 (2016).

Knights, D. et al. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat. Methods 8, 761–763 (2011).

McGhee, J. J. et al. Meta-SourceTracker: application of Bayesian source tracking to shotgun metagenomics. PeerJ 8. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8783 (2020).

Benjamin, B. et al. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Knierim, K. J. et al. Evaluation of the lithium resource in the Smackover formation brines of southern Arkansas using machine learning. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp8149 (2024).

Yan, Z. The impact of bamboo surface microbiota on the gut microbiota of giant pandas. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15441606 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Independent Project of Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (2021CPB-C14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H., Y.Y., X.Q., H.X., and Y.Z. conceptualized and designed the study; Y.Y., X.Q., H.X., and Z.X. contributed to sample collection and experimental implementation; Y.Z. performed data analysis, interpreted the results, and conducted statistical analysis; Y.Z. drafted the manuscript and designed the figures; W.H. supervised the study, provided critical feedback, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Karen Peralta and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Z., Yao, Y., Xu, Q. et al. Dietary microbiota-mediated shifts in gut microbial ecology and pathogen interactions in giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Commun Biol 8, 864 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08270-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08270-x

This article is cited by

-

Molecular mechanisms of bamboo-derived miRNA-mediated gene regulation and dietary adaptation in giant pandas

BMC Genomics (2025)

-

Lignocellulose degradation capabilities and distribution of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors in Clostridium from the gut of giant pandas

Communications Biology (2025)