Abstract

Lice are obligate ectoparasites that have co-evolved with their hosts, particularly during the transition of mammals from terrestrial to amphibious habits, as sea lions, seals and walruses, and have undergone parallel adaptations to the extreme conditions of the deep sea. By combining morphological, physiological and genomic analyses, we are shedding light on a key process for surviving prolonged submersion: respiration. Under water, lice immobilise, close their spiracles, reduce their oxygen consumption to a minimum and breathe through their tegument. The presence of haemoglobin genes in their genome also strongly suggests the ability to store oxygen during host dives. Remarkably, seal lice have no anatomical features or physiological capabilities that distinguish them from other insects. This reinforces the idea that the absence of insects in the deep sea is not due to any inherent limitations in their form or function, but rather a result of their evolutionary pathways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since their emergence, more than 420 Mya, insects have dispersed and diversified to become the most ecologically and evolutionarily successful group of organisms on Earth. Interestingly, a group that has colonised almost every available terrestrial habitat is virtually absent from the largest available habitat, i.e., the ocean, which makes up more than 99% of our biosphere. The reasons for this rare occurrence in marine ecosystems have led to a number of scientific hypotheses and assumptions (physiological constraints, competition with Crustaceans, oxygen availability, etc)1,2. Still, there is one particular group of insects that have managed to survive underwater for very long periods and at great depths—sucking lice (Psocodea: Phthiraptera)3.

Among insects, lice are the only ectoparasites that live their entire lives in permanent association and co-evolution with their mammalian hosts. The thirteen species of the family Echinophthiriidae are unique in that they infest aquatic mammals such as pinnipeds (walruses, seals, and sea lions) and the northern river otter4,5. Pinnipeds are diving mammals and many of them forage at considerable depths6. The most exceptional diver is the southern elephant seal, which can reach depths of over 2000 m for several minutes7 and spends most of the year in the open ocean during their feeding season, not returning to land for months8,9. Despite the extreme constraints imposed on seal lice by these habits, these insects have managed to adapt to the amphibian biology of their hosts by accompanying them to the sea10. The survival of an originally terrestrial louse in the depths of the ocean implies that this insect has gradually evolved to tolerate the particular physical conditions of extreme environments, such as high hydrostatic pressure, hypoxia, low temperature, and high salinity.

In previous studies in Patagonia, we have shown that lice can survive drowning in seawater for relatively long periods11. However, their survival appeared to depend on the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water, suggesting that seal lice may be able to exchange gases with seawater or even store oxygen reserves in their bodies. A third possibility is that the lice would reduce their metabolism to a minimum during the time they spend in the open sea, as suggested by the reflex immobility they display when in contact with seawater3,11. These three mechanisms are not mutually exclusive alternatives, but they would represent complementary ways of coping with the changing environmental conditions to which they are exposed, from the hot Patagonian summer on land to the cold depths of the Antarctic waters.

All sucking lice (Anoplura) are adapted to a moderate tolerance of water immersion. After all, most mammals go through periods when their fur is soaked for hours or days. All lice have spiracles that prevent water from entering. However, seal lice take this to a greater extreme than other groups because their host’s coat generally does not trap air and they are constantly immersed for long periods12.

The possibility that seal lice could breathe underwater and thus survive submerged for months has been discussed for half a century. Some authors have suggested that the acquisition of oxygen from the water could be by cutaneous exchange13 or by means of a physical gill formed by the scales covering the louse’s body, i.e. a plastron14. However, neither of these possibilities has been demonstrated. More recently, Burgess12 proposed an interesting and provocative hypothesis, suggesting that the oxygen present in the host’s blood may be sufficient to meet the insect’s needs in cold oceanic waters and that underwater breathing may probably not be necessary. To date, none of these hypotheses, i.e. cutaneous respiration, plastron, or apnoea, has been tested experimentally. However, the discovery that lice survive longer in normoxic than in hypoxic seawater suggests that aquatic respiration does occur in these insects11.

Modern respirometric instruments can measure subtle changes in oxygen concentration in both air and water and can provide important information, particularly about two important aspects: aquatic respiration and metabolic rates. Measuring the changes in oxygen concentration in water and air induced by the presence of submerged or air—breathing lice could finally provide quantitative data on both the lice’s ability to extract oxygen from the water and the reduction in their metabolism induced by submersion.

The independent search for evidence of the presence of respiratory pigments should allow the validation or rejection of the idea of oxygen reserves. In recent years, different globin genes (GBs) have been identified in different organisms. Three GB lineages have been described: haemoglobin-like (HbL), globin X (GbX), and globin X-like (GbXL). These types of GBs have previously been observed in protostomes, deuterostomes (including vertebrates), suggesting their bilaterian ancestry15. HbLs are small respiratory proteins that contain a haem group and are able to bind and release oxygen. Based on phylogenetic analysis and their sequence characteristics15, GbX and GbXL have been proposed to have non-respiratory functions and play a role in cell signalling and membrane lipid protection. Haemocyanins (HCs) are another group of respiratory proteins that belong to the type III copper-binding proteins and are completely soluble in haemolymph, where they bind oxygen molecules. However, HCs have not yet been identified in holometabolous and paraneopteran species16,17.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the respiratory adaptations that allow seal lice to cope with the extremely diverse environmental conditions to which they are exposed. We investigated whether seal lice are able to breathe underwater and whether respiratory pigments are present in this group of insects. We have adopted an approach that integrates functional morphology, respirometry, and genomic analysis in order to understand the respiratory physiology of a rather unique group of insects, i.e. seal lice.

We were able to uncover several morphological and physiological mechanisms that allow the lice to survive the depths and long dives of their hosts. These include a robust mechanism for closing the spiracles to prevent water from entering the tracheal system, reflex immobilisation associated with a marked reduction in oxygen consumption induced by submersion and low temperature, cuticular gas exchange, and the probable oxygen reserve associated with haemoglobin.

Results

The louse respiratory system

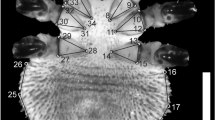

The louse respiratory system consists of a well-developed tracheal tree with two main trunks connected by a transverse trunk at the posterior part of the abdomen. The main trunks give rise to centrifugal tracheal branches that connect the lateral parts of the body and the lateral thoracic and abdominal spiracles (Fig. 1A, B). The respiratory system of seal lice has some remarkable features compared to other Anoplura. The first is the diameter of the main tracheae, which is unusually large compared to other lice, and the second is the large posterior anastomosis, which gives the whole system the aspect of a “U” shape, and is either absent or much thinner in other Anoplura (Fig. 1C, D, cf18).

In seal lice, spiracles are prominent structures protruding from the body wall (Fig. 2A), in contrast to the flat appearance of human lice (Fig. 2B, cf18). The spiracles have internal atria associated with an elaborate closure system. This system consists of a cuticular plug below the spiracle which is heavily sclerotized and fills most of the atrial cavity (Fig. 3A, D, E). It appears to consist of two interdigitating valves (Fig. 3C). The highly sclerotized cuticle of the plug proceeds proximally along the atrial cavity and beyond forming a prominent atrial cuticular ridge (Fig. 3A, B, D, E). Proximally, the atrium enters the trachea, which carries some spinous processes in its initial lining followed by regular prominent taenidia. A prominent, also highly sclerotized cuticular rod attaches to the atrio-tracheal junction (Fig. 3B, D, E). Two occlusor muscles, one extensive and the second smaller, originate from the proximal tip of the rod to insert at the epidermis, laterally of the spiracle (Fig. 3B, D). Their contraction presses the cuticular rod in the axis of the plug, acting as a piston to enable closure of the spiracle. Other Anoplura also have cuticular rods at the atrio-tracheal junction, but in L. macrorhini the closure apparatus is much more elaborate and complex19,20. In general, the cuticle in L. macrorhini shows multiple thick sclerotized patches throughout the cuticle (Fig. 3B).

A Longitudinal section of the atrium showing the prominent cuticular plug. B Section of the cuticular rod involved in closure of the spiracle and associated occlusor muscles. C Detail of the bilayered, interdigitating parts of the cuticular plug. D 3D-reconstruction from dorsal view, with both occlusors displayed. E 3D-reconstruction, lateral view showing the cuticular plug, atrial ridge, and cuticular rod in relation to atrium and trachea. at–atrium, atr atrial cuticular ridge, cp cuticular plug, cr cuticular rod, cu cuticle, ocl occlusor muscles, tr trachea, scu sclerotized cuticle.

Oxygen consumption

The respirometry experiments showed that adult lice consume oxygen when submerged in seawater. Oxygen consumption was higher in air than in water (Table 1; Data availability in ref. 21). Also, the rate of consumption was different in the air and submerged in water at different temperatures (Table 1). We found that adults consumed more oxygen when exposed to 22 °C compared to 13 °C, but this difference was greater in the air than when submerged in water. (Table 2) We then found that oxygen consumption at 22 °C was different for adults or nymphs. (Table 3) Looking at the respiration of adults and nymphs in air and water, our results show that adults consume more oxygen than nymphs, although this difference is greater in air than in water (Table 4). The calculated Q10 in adults was 3.99 in air and 1.99 in water, in line with the observed metabolic reduction when lice are in seawater.

Fig. 4 depicts the metabolic energy expended by resting adults exposed to the two media at two temperatures. Both immersion and temperature reduction had similar effects in drastically reducing the lice’s metabolic rate. These data allowed us to estimate the time required to metabolise 1 mg of blood food, which varied from about 48 h breathing air at 22 °C to 1 week, being similar to air at 13 °C, and water at 22 °C and 13 °C.

The energy expenditure of resting lice differed significantly across treatments (ANOVA, P < 0.001.) This difference is due to the dramatic reduction in lice metabolism caused by immersion and low temperature (Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, P < 0.001 for air at 22 °C vs. each of the remaining conditions, n.s. among them).

Genome assemblies

The average number of contigs per genome was 15,366, ranging from 9716 in A. ogmorhini to 29,393 in L. macrorhini. The average of N50 and L50 values was 22,340 and 3211, respectively. The GC content was very stable and varied between 35.5% and 36.78%. After the annotation step, the average number of predicted proteins per assembled genome was 20,854, with A. microchir and L. macrorhini being the species with the lowest (16,602) and the highest (26,764) number of predicted proteins, respectively (Supplementary Files 1 and 2).

All genome annotations, except L. macrorhini and E. horridus, showed more than 90% of complete BUSCOs from the hemiptera_odb10 lineage, and the proportion of duplicated BUSCOs was less than 5.5% in all cases. (Supplementary File 1).

Globin repertoires are highly conserved

The GB repertoire consisted of five genes (one GbX, one GbXL, and three HbL genes) in all species except L. macrorhini, where no GbX sequence was identified (Supplementary file 1). The GB phylogenetic tree showed three separate clades: one formed by GbXs (blue), another with GbXLs (green), and the third one containing the HbL lineages (red) (Fig. 5). A few GB sequences from other insects, probably too short and/or partial, were not correctly placed in the tree.

The maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using IQ-Tree, and support values shown in branches are aLRT-SH values (ranging from 85 to 100.) The tree was rooted at the midpoint. Seal lice identifiers are in bold. The HbL, GbX, and GbXL clades are marked in red, blue, and green, respectively. All sequences used to build the GB phylogenetic tree are in fasta format in Supplementary Data 1.

Seal lice genomes lack haemocyanin genes

Our phylogenetic analysis classified all HC candidate genes as hexamerins (HXs) and prophenoloxidase (PPO.) (Supplementary Fig. 1). All species have one HX and one PPO, except P. humanus, E. horridus, and L. macrorhini, which have two HX genes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Sequence and structural analyses

A total of 25 out of 39 GB sequences are complete, i.e. including the initial methionine and STOP codon, and their length varied between 130 and 353 amino acids. (Supplementary Data 1) DeepLoc 2.0 predictions showed that the GBs were distributed in the cytoplasm (20), cytoplasmic membrane (17), and plasma membrane (2.) All HbL3 proteins would be located in the cytoplasm. (Supplementary Data 1) According to PSIPRED predictions, most of the GBs (36) had between 6 and 8 alpha-helix segments (Supplementary File 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), which is consistent with the secondary structure described for GBs22. Concerning key residues in the alpha-helix segments, positions A12, CD1, E7, and F8 were highly conserved (Supplementary Fig. 1). A12 was a tryptophan (W) in 85% of GB sequences, while all GBs had a phenylalanine (P), a histidine (H), and a histidine (H) in positions CD1, E7, and F8, respectively. Position B10 was phenylalanine in almost half of the GBs (19 sequences); however, HbL2 and HbL3 sequences had a cysteine (C) and an alanine (A), respectively. At position E10, GbXL, and HbL1 sequences had an asparagine (N), HbL2 and HbL3 sequences had an alanine, and GbX sequences had an arginine (R). Finally, position E11 was occupied by a valine (V) in 23 sequences (including all GbX, GbXL, and HbL3, except Ehor_g10336.t1) and an isoleucine in 16 sequences, including all HbL1 and HbL2, except PhumHbL2, which had a valine. The comparison of these key residues between P. humanus and seal lice showed that the HbL2 sequence from P. humanus had differences at positions B10 (F instead of C) and E11 (V instead of I); and in the HbL3 sequence, the human lice had a glutamic acid (E) at position B10 instead of an alanine like the seal lice (Supplementary File 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

The glycine at position 2 found on the GbXL and HbL1 sequences underwent an N-myristoylation reaction according to the three programmes (Supplementary Data 2). Except for the EhorGbX sequence, the rest of the GbX and the HbL1 and HbL2 lineages did not show a conserved myristoylation site in the N-terminal region. Only the GbXL sequences had a palmitoylation site on the cysteine at position 3 (Supplementary File 1).

Discussion

We have shown experimentally that a marine air-breathing insect can also breathe underwater. The present study shows that both adults and nymphs were able to obtain enough oxygen from seawater to ensure their survival.

A previous study11 raised the question about the potential ability of seal lice to recover oxygen from the surrounding medium and/or to conserve oxygen from the air. In the present work, we show that lice actively consume dissolved oxygen from seawater. Underwater respiration has been reported for several groups of aquatic insects, including heteropterans, coleopterans, dipteran larvae of Culicidae, Chironomidae, and Ceratopogonidae, and some trichopteran larvae23. In these cases, however, the insects remain in contact with the surface or a few centimetres below the surface. Some species remain submerged indefinitely by drawing dissolved oxygen directly from the water through their cuticle (with or without tracheal gills) and at depths of many metres. What is unusual about seal lice is that the oxygen they consume appears to be sufficient to ensure their survival during the long feeding journeys of their hosts.

Pinnipeds are diving mammals that spend several months at sea foraging, usually at considerable depths7,9. During the feeding season, which lasts for most of the year, most pinnipeds remain at sea. Whilst, during the rest of the year, they alternate periods of rest, moult, and reproduction ashore. Thus, seal lice have had to adapt to the amphibian biology of their hosts3,10. Previously, prolonged tolerance to immersion was thought to depend on a reduction in metabolic activity11. In his seminal studies, Kim20 proposed that lice enter a state of quiescence upon contact with water. Quiescence is defined as an immediate response to a decrease in any limiting environmental factor (e.g. temperature, oxygen concentration, humidity) below a physiological threshold22 and it is usually associated with a decrease in the metabolic rate of the animal. This idea was also been supported by previous observations11. Leonardi and Lazzari11 described that once Antarctophthirus microchir came in contact with the seawater, no movement of the legs or antennae could be detected. In this sense, temperature, wetting, and low oxygen availability could then trigger akinesis, and probably low metabolic activity, reducing the lice’s need for nutrients and oxygen. We observed that L. macrorhini could remain active for a few minutes after submersion and then remain inactive until they were exposed to air again. These observations suggest that akinesis is indeed a response to submersion, but also that the reduction in the metabolic rate could also be a response to hydrostatic pressure.

The internal tissues of any insect are composed mainly of water and are therefore incompressible. Consequently, when seal lice are exposed to great depths, only the air-filled organs are affected by the pressure. The collapse of the tracheal system would mean that gas exchange would not be possible at high hydrostatic pressure. Breathing would therefore only be possible if the seal remained in the first few metres of the water column. The assumption that the tracheal system collapses underwater also implies that the sophisticated closing device present in the spiracles prevents seawater from entering and keeps them both airless and waterless. Seal lice, as expected, have specialised spiracles that are unique to Anoplura. So far, spiracle structure and its closing mechanism have been studied in the echinophthiriids E. horridus19, A. microchir24, and A. callorhini and P. fluctus20. In the latter species, the atrial cavity is described as elongated (with sclerotized and membranous parts in A. microchir and E. horridus), whereas L. macrorhini has a prominent, highly sclerotized cuticular plug in a comparatively short atrial cavity. A so-called triangular plate was reported at the atrio-tracheal junction and is supposedly involved in the closure of the spiracles in echinophthiriids. At the same location the cuticular rod, operated by an occlusor muscle, is also present in E. horridus and A. microchir, similar to L. macrorhini. In A. callorhini and P. fluctus, a supposed apodeme is present involved in spiracle opening20. Topologically, the ‘triangular plate’ and supposed apodeme resemble the sclerotized atrial ridge of L. macrorhini that extends in the direction of the cuticular rod. From the current data, there seem to be at least two different closure mechanisms in echinophthiriids, the cuticular-plug type as found in L. macrorhini and the type with elongated atrial tube and triangular plate in other species. The particular elaborate closure mechanism might be a specific adaption of L. macrorhini.

Human head lice can survive submerged for several hours without moving25. They close their spiracles25,26 and the hydrophobic surface of the spiracle atria also prevents water from entering. Eventually, however, water enters the body and the louse dies by drowning25. In this sense, seal lice must have developed an efficient closure system to keep the spiracles closed for several days or even months, despite pressure fluctuations in the tracheal cavity, due to the extremely rapid changes in hydrostatic pressure acting on the louse body during rapid descents and ascents of hundreds of metres below the surface. As can be seen from microscopic analysis, the spiracles of L. macrorhini do not have a hydrophobic structure. Instead, they have a well-developed sealing system.

Given these considerations, aquatic respiration should be possible by two main mechanisms. One possibility is gas exchange through the cuticle. The abdominal cuticle of seal lice is membranous and considerably thicker than the typical anopluran abdomen27. Yet, some species have a ventral cuticle that is at least half as thin as the dorsal cuticle, which would facilitate gas diffusion27. The second option has been widely discussed over the last 50 years and raises the possibility of the existence of a plastron14. Hinton14 proposed that the scales, the specialised and modified spines characteristic of seal lice, could form a ‘plastron’. A plastron is a physical gill formed by a thin layer of air held in place by hydrophobic structures, allowing underwater breathing. Although Hinton himself recognised how difficult it was to create. However, it is likely that the layer of air would probably collapse completely due to the high hydrostatic pressure experienced during dives, even shallow ones.

For a long time, it was thought that the tracheal system was sufficient to distribute oxygen throughout the body. The tracheae deliver oxygen directly to the cells without the need for respiratory proteins such as haemoglobin. Until recently, the presence of haemoglobin was thought to be restricted to insects exposed to hypoxic conditions. However, Burmester28 demonstrated its presence in species that do not have limited access to oxygen. Subsequently, Herhold et al.29 showed that genes encoding haemoglobin were present in the genomes of all insect orders. These authors suggest that this protein was acquired independently of neuroglobin precursors through gene duplication.

We found that seal lice are no exception. The analysis of the complete genomes allowed us to study the GB gene repertoire and to characterise the evolution and diversity of this protein superfamily in the seal lice. The GB phylogeny was consistent with those previously reported, showing two major clades separating GbX and GbXL groups from the HbL lineages. (Fig. 5) The HbL clade is divided into two groups. (Fig. 5) The group with the red coloured tree branches contains, among others, the seal lice sequences and the DmelGlob1 gene. Burmester et al.30 proposed that DmelGlob1 is involved in respiratory functions as it is evolutionarily related to the respiratory haemoglobins of Gasterophilus intestinalis and those of chironomids31,32, and its expression in the D. melanogaster SL2 cell line is affected by hypoxia33. The close evolutionary relationship of the seal lice HbL genes, especially the HbL1 genes, to DmelGlob1, suggests that these genes would also have a respiratory role. Detection of HbL transcripts in the tracheal cells and fat body would be crucial to confirm the role of these genes in seal lice respiration30.

Seal lice HbL presented the three highly conserved amino acids in the alpha-helix regions, i.e. phenylalanine at position CD1 and the distal and proximal histidines at positions E7 and F8. (revised by Burmester and Hankeln17) These amino acids are directly required for ligand binding and haem coordination34,35,36. The conservation of these amino acids in key positions of the GB chain suggests that seal lice HbLs are functional in oxygen binding. HCs have been described in Collembola, Diplura, Archaeognatha, Zygentoma, Plecoptera, Orthoptera, Phasmida, Dermaptera, Isoptera, and Blattodea, but not yet found in holomeabolous and paraneopteran insects16,17. These genes are also absent from seal lice genomes, reinforcing this evolutionary pattern. To date, no environmental, morphological, or physiological traits are known to explain the presence or absence of HC in insects17. Despite the thorough analysis of the GB and HC sequences in the seal lice species conducted in our study, their roles remain speculative and further studies are needed to confirm their functions.

In conclusion, it is hard to think of another organism that faces the extraordinary challenges of seal lice. Adults reproduce and transmit on land during the hot or Antarctic summers, depending on the species. Once the host’s reproductive season is over, they leave the land for the rest of the year, accompanying their deep-diving hosts thousands of miles into the open ocean. Among the many constraints on lice survival, the availability of sufficient oxygen appears to be one of the most challenging. The variety of situations and environments that a louse experiences throughout its life require respiration to adapt to the conditions of the moment, i.e. atmospheric air, oxygen-rich water near the surface, and hypoxia in the minimum oxygen zone (200–1500 m depth).

On land, like any other terrestrial insect, lice can breathe atmospheric air through their spiracles and diffuse gases through their well-developed tracheal system. When submerged, their elaborate closure system can prevent water from entering the tracheal system20, which maintains a certain reserve of oxygen. Our oxygen consumption measurements indicate that lice do consume oxygen from the water. We do not know whether this uptake requires a plastron or not. The possible existence of a plastron was proposed by Hinton14 to explain the possible role of the scales that cover the louse’s body. However, no plastron has been observed in seal lice. On the other hand, even if present, the plastron, like the entire tracheal system, would only be functional near the water surface because it would collapse under high hydrostatic pressure. Regardless of the presence of a plastron, a tegumentary gas exchange could only occur near the surface, where the concentration gradient favours the entry of oxygen into the louse’s body. The low level of available oxygen at great depths could affect the uptake of oxygen from the water. Lice may use haemoglobin-bound oxygen when their hosts dive. Insect haemoglobins have a much higher affinity for oxygen than vertebrate haemoglobins. Oxygen is rapidly and tightly bound and only released when the surrounding tissues have very low levels. This property allows insects exposed to hypoxia, such as benthic chironomids, parasitic botflies, or bubble diving bugs, to tolerate the absence of oxygen for relatively long periods. In the case of lice, this can occur when hosts dive to depths of hundreds or thousands of metres.

The study of seal lice may help to better understand the reason for the absence of insects in the deep sea. The most obvious conclusion is that the popular idea that insect morphology and physiology are incompatible with marine conditions is no longer valid. Seal lice are not very different from other insects, nor do they have special structures or physiological characteristics that make them different from other insects. They have simply adapted gradually over a long co-evolution to live in close association with their hosts. These findings also highlight our limited knowledge of key aspects of insect respiratory physiology. For example, the exact physiological role of respiratory pigments or how hydrostatic pressure and trachea compression affect gas exchange inside the insect body.

Methods

Lice samples

We collected seal lice, Lepidophthirus macrorhini, from weaning pups of southern elephant seals Mirounga leonina. Samples were collected in the Península Valdés Nature Reserve (42°45′S, 63°38′W), Chubut Province, Argentina, during the 2022 seal breeding season. We collected lice from 19 pups, which were caught and handled manually to minimise animal stress. Lice were removed from flippers with tweezers and transferred from the field to the laboratory in fresh seawater. They were kept in aquaria at 13 ± 1 °C with UV-sterilised and aerated seawater until use in the experiments. The weight of the insects used for experiments were 1.71 ± 0.10 mg and 0.91 ± 0.13 mg (mean ± s.e.m.), in adults and nymphs, respectively.

Anatomy of the lice respiratory system

The general anatomy of the tracheal system was analysed using X-ray micro-CT and scanning electron microscopy. For X-ray micro-CT, an adult L. macrorhini was dehydrated in a graded ethanol series to 100% ethanol, critical point dried using a Leica CPD300 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), mounted, and observed in a XRadia MicroXCT-400 (Carl Zeiss X-ray Microscopy, Pleasanton, CA, USA). Two scans of the individual were taken at different resolutions for an overview scan and a more detailed scan of spiracles. Stacks were analysed and reconstructed with the visualisation software Amira 2020.2 (ThermoFisher). Segmentation was done manually for the tracheal system, sometimes with interpolations between sections. Segmented structures were visualised as surface rendering, whereas surrounding tissues were visualized as volume rendering.

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), individual lice were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, 70%, 80%, 90%, 96%, and 100% ethanol concentration, for 15 min each. The insects were then immersed in hexamethyldisilazane for 5 min and left at room temperature for ~3 min. The dried samples were observed with an environmental scanning electron microscope (ZEISS EVO 10, 10 kV) at IBIOMAR-CONICET.

For histological analyses, specimens were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series to 100% ethanol before being infiltrated in Agar Low Viscosity resin (Agar, Stansted UK) using acetone as an intermediate. Cured resin blocks were serially sectioned on a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with a Diatome HistoJumbo diamond knife (Diatome, Nidau, Switzerland) at a thickness of 1 µm. Sections were stained with toluidine blue for 10 s and afterwards sealed with resin. Sections were analysed and documented with a Nikon NiU (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) compound microscope with a DsRi2 microscope camera. Serial sections of spiracles were photographed, afterwards converted into grey-scale with FIJI and then imported into the 3D visualisation software Amira 2020.2 (ThermoFisher). First, consecutive images of the stack were aligned and afterwards structures of interest (muscles, trachea, atrium, cuticular structures) were manually segmented and rendered as surface models.

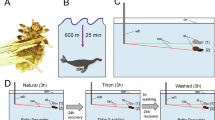

Oxygen consumption

The oxygen consumption of L. macrorhini adults and nymphs was measured using oxygen optodes21. An optode or optrode is an optical sensing device that measures a specific substance optically, usually by means of a chemical transducer. In this case, we used a 4-channel Firesting O2 metre (Pyro Science, Aachen, Germany) with 4 ml vials containing an integrated optical oxygen transducer (OXVIAL 4.) In brief, the light of specific wavelength flashes at the interface and passes through an optical fibre to excite a transducer inside the vial from the outside. The luminescence of the substance, which is proportional to the oxygen concentration in the medium (air or water), is collected by the same optical fibre and analysed at the interface. A temperature sensor from the oxygen meter measures the temperature inside an empty vial and its signal allows the system to adjust the values of the measured O2 concentrations.

In order to study if lice are able to consume oxygen while being submerged, we exposed adult lice to different conditions: vials were filled either with air or seawater (no bubbles allowed) and kept either at 22 °C or at 13 °C in a thermo-stated chamber. Lice were put into vials in pools (N = 192, adults n = 126, nymphs = 66), which were tightly closed, and the O2 concentration was recorded for 5 h. Then, we studied whether oxygen consumption was different for adults or nymphs lice. We exposed the lice to either seawater or air at 22 °C, as this was expected to result in the highest levels of oxygen consumed. Oxygen consumption was then calculated by subtracting each experimental measurement from the control vial on each round. The oxygen consumption rate was then modelled with a general linear mixed model with a Gaussian distribution. Predictor variables included continuous time, individual stage (two-level factor, adult and nymph), vial condition (two-level factor, submerged or in the air), and temperature (two-level factor, high and low.) Post hoc comparisons were made by comparing the slopes for each level of the predictor factors. The linear model was performed with the function lmer from the “lme” library37. Post hoc comparisons were performed with the function emmtrends from the “emmeans” library38. Graphs were generated using the ggplot2 library39. Finally, the oxygen consumption measured under each condition we converted into metabolic energy, and the time required to consume the 3.91 joules of energy content in 1 mg of blood food was estimated, following the procedures employed by Leis and Lazzari40 for another paraneopteran haematophagous insect, Rhodnius prolixus.

Genome assembly and annotation

Raw reads for each species were downloaded from SRA. (details in Supplementary Data 2) All sequencing experiments were generated by Leonardi et al.41, except for Echinophthirius horridus, and have more than 39 M of paired-end reads. (Supplementary File 1) The FASTQC software (https://bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) was used to analyse the read quality and the presence of Illumina sequencing adaptors. After that, adaptors and those bases from 5′ and 3′ ends with quality scores lower than 5 (TRAILING: 5 and LEADING: 5 parameters) were eliminated from the reads through Trimmomatic v.0.32 in the paired-end mode42. The SLIDING-WINDOW parameter was fixed at 4:20. Trimmed and cleaned reads were mapped using STAR v.2.6.043 in paired-end mode against the bacterial sequences from the NCBI Reference Sequence Database to eliminate contaminants. The unmapped reads were used to generate genome assemblies with SPAdes Assembler v.3.15.444,45 in default mode. The quality metrics and statistics of the genomes were evaluated using QUAST v.5 at https://quast.sourceforge.net/ (Mikheenko et al.46. BRAKER47 was used to generate gene predictions for each assembly using Arthropod protein sequences from OrthoDB v.1048 as a reference. The quality of these annotations was evaluated using BUSCO v4.1.449 in protein mode against the hemiptera_odb10 lineage data set. (Supplementary File 1).

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of globin and haemocyanin sequences

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool in protein mode (BLASTp) searches on the predicted peptide databases for each species were performed using the following queries: (1) Pediculus humanus globin (GB) sequences previously described by (Prothmann et al.50); (2) Globin sequences from other insects29,50 and HCs sequences from Burmester16 and Burmester and Hankeln17; (3) the PFAM seed sequences (PFAM00042 for GBs and PF03722, PF03723, and PF00372 for HC) in fasta format (unaligned) for each family. BLAST results were filtered by sequence identity >30% and e-value < 1 × 10–7. In addition, HMMscan searches51 using Hidden Markov Model (HMM) PFAM profiles for each target family were performed on the predicted protein databases to identify additional candidates. This final set of protein sequences was manually curated using reference sequences from P. humanus and D. melanogaster. Globin seal lice candidates and GB sequences of several insect orders (in addition to those from Ixodes scapularis) from Prothmann et al.50 were used for the phylogenetic analysis. Haemocyanin, HX, and PPO sequences from Burmester16 and Burmester and Hankeln17 were included in the phylogenetic analysis in order to annotate and study HC candidates.

The protein sequences belonging to each gene family were aligned using the MAFFT v7.5 tool with the G-INS-i strategy and the following settings: unaligned level = 0.1; offset value = 0.12; maxiterate = 1000, and the option 'leave gappy regions'. After trimming (using the trimAl v1.2 programme by default except for the gap threshold = 0.3), the alignments were used to create phylogenetic trees on IQ-tree v1.6.12. The branch support was calculated using the approximate Likelihood Ratio tests based on the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (aLRT-SH) approximation. The ModelFinder tool was used to determine the best-fit amino acid substitution models and was chosen according to the Bayesian Information Criterion. The LG + R9 and LG + F + R4 models were used to build the GB and HC trees, respectively. Finally, the phylogenetic trees were edited with the iTool software. Gene candidates were annotated based on their orthology relationships with those of P. humanus. All seal lice sequences identified and those used to build the phylogenetic trees are in Supplementary Data 1 in fasta format.

Sequence analysis

Protein secondary structure predictions for GBs were obtained using PSIPRED v4.052. Following, the number and location of alpha-helix (designated A through H) were determined. Only those alpha-helix predicted by PSIPRED programme longer than 5 amino acids were considered. Functionally important amino acid residues found at key helical positions were identified based on17,53. The subcellular location of GBs was estimated using DeepLoc v2.054. Finally, sequences were analysed for N-terminal posttranslational acylation (addition of an acyl group) motifs, which have been previously observed in GBs15,50. Globins undergo myristoylation (attachment of a myristate to the glycine residue at the N-terminus) and palmitoylation (addition of a palmitate) reactions. Myristoylator55, PROSITE56, SVMyr57, and NMT-Predictor58 tools were used to predict N-myristoylation at the glycine at position 2. The presence of palmitoylation motifs at the cysteine at position 3 was determined using pCysMod59 and GPS-Palm60 tools, both with medium thresholds.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in NCBI and are associated with the following BioProjects and respective accession numbers: for Antarctophthirus microchir, BioProject PRJNA389900 with SRA accession SRX2987922 and genome submission SUB13574901; for Antarctophthirus carlinii, BioProject PRJNA389901 with SRA accession SRX2987923 and genome submission SUB13693101; for Antarctophthirus ogmorhini, BioProject PRJNA389903 with SRA accession SRX2987925 and genome submission SUB13693121; for Antarctophthirus lobodontis, BioProject PRJNA389902 with SRA accession SRX2987924 and genome submission SUB13693158; for Lepidophthirus macrorhini, BioProject PRJNA389904 with SRA accession SRX2987926 and genome submission SUB13693186; for Proechinophthirus fluctus, BioProject PRJNA349478 with SRA accession SRX2609263 and genome submission SUB13716064; and for Echinophthirius horridus, BioProject PRJNA490904 with SRA accession SRX4966507 and genome submission SUB1369336821.

References

Ruxton, G. D. & Humphries, S. Can ecological and evolutionary arguments solve the riddle of the missing marine insects? Mar. Ecol. 29, 72–75 (2008).

Reynolds, S. Minute exceptions: insects that live in the sea. Antenna 45, 7–15 (2023).

Leonardi, M. S., Crespo, J. E., Soto, F. & Lazzari, C. R. How did seal lice turn into the only truly marine insects? Insects 13, 46 (2021).

Durden, L. & Musser, G. The sucking lice (Insecta, Anoplura) of the world: a taxonomic checklist with records of mammalian hosts and geographical distributions. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 218, 1–90 (1994).

Leonardi, M. S. & Palma, R. L. Review of the systematics, biology and ecology of lice from pinnipeds and river otters (Insecta: Phthiraptera: Anoplura: Echinophthiriidae). Zootaxa 3630, 445–466 (2013).

Stewart, B. Diving Behavior (Academic Press, 2018).

McIntyre, T. et al. A lifetime at depth: vertical distribution of southern elephant seals in the water column. Polar Biol. 33, 1037–1048 (2010).

Teilmann, J., Born, E. W. & Acquarone, M. Behaviour of ringed seals tagged with satellite transmitters in the North Water polynya during fast-ice formation. Can. J. Zool. 77, 1934–1946 (1999).

Kendall-Bar, J. M. et al. Brain activity of diving seals reveals short sleep cycles at depth. Science 380, 260–265 (2023).

Leonardi, M. S., D’Amico, V. L., Márquez, M. E., Rogers, T. L. & Negrete, J. Leukocyte counts in three sympatric pack-ice seal species from the western Antarctic peninsula. Polar Biol. 42, 1801–1809 (2019).

Leonardi, M. S. & Lazzari, C. R. Uncovering deep mysteries: the underwater life of an amphibious louse. J. Insect Physiol. 71, 164–169 (2014).

Burgess, I. F. How do Echinophthiriidae on Seals Survive Months of Immersion–a Hypothesis for Debate. In: Proc. 4th International Conference on Phthiraptera (ICP4, 2010).

Murray, M. Insect Parasites of Marine Birds and Mammals. In Marine Insects (ed. Cheng, L.) 78–96 (American Elsevier Publishing Company, 1976).

Hinton, H. E. Respiratory Adaptations of Marine Insects. In Marine Insects (ed. Cheng, L.) 43–78 (American Elsevier Publishing Company, 1976).

Blank, M. & Burmester, T. Widespread occurrence of N-terminal acylation in animal globins and possible origin of respiratory globins from a membrane-bound ancestor. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 3553–3561 (2012).

Burmester, T. Molecular evolution of the arthropod hemocyanin superfamily. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 184–195 (2001).

Burmester, T. & Hankeln, T. The respiratory proteins of insects. J. Insect Physiol. 53, 285–294 (2007).

Candy, K. et al. Do drowning and anoxia kill head lice? Parasite 25, 8 (2018).

Webb, J. E. Spiracle structure as a guide to the phylogenetic relationships of the Anoplura (biting and sucking lice), with notes on the affinities of the mammalian hosts. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 116, 49–119 (1946).

Kim. Ecology and morphological adaptation of the sucking lice (Anoplura, Echinophthiriidae) on the northern fur seal. Rapp. P.-v. Réun. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer 169, 504–515 (1975).

Leonardi, M. S. et al. Host-parasite coevolution leads to underwater respiratory adaptations in extreme diving insects, seal lice (Lepidophthirus macrorhini) [Data set]. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28805981 (2024)

Koštál, V. Eco-physiological phases of insect diapause. J. Insect Physiol. 52, 113–127 (2006).

Cheng, L. Marine Insects (American Elsevier Publishing Company, 1976).

Murray, M. D. & Nicholls, D. G. Studies on the ectoparasites of seals and penguins. 1. The ecology of the louse Lepidophthirus macrorhini Enderlein on the southern elephant seal, Mirounga leonina (L). Aust. J. Zool. 13, 437–454 (1965).

Burgess, I. F. Physically acting treatments for head lice—can we still claim they are ‘resistance proof’? Pharmaceutics 14, 2430 (2022).

Mumcuoglu, K. Y., Meinking, T. A., Burkhart, C. N. & Burkhart, C. G. Head louse infestations: the ‘no nit’ policy and its consequences. Int. J. Dermatol. 45, 891–896 (2006).

Mehlhorn, B., Mehlhorn, H. & Plötz, J. Light and scanning electron microscopical study on Antarctophthirus ogmorhini lice from the Antarctic seal Leptonychotes weddellii. Parasitol. Res. 88, 651–660 (2002).

Burmester, T. Evolution of respiratory proteins across the Pancrustacea. Integr. Comp. Biol. 55, 792–801 (2015).

Herhold, H. W., Davis, S. R. & Grimaldi, D. A. Transcriptomes reveal expression of hemoglobins throughout insects and other Hexapoda. PLoS ONE 15, e0234272 (2020).

Burmester, T., Storf, J., Hasenjager, A., Klawitter, S. & Hankeln, T. The hemoglobin genes of Drosophila. FEBS J. 273, 468–480 (2006).

Ewer, R. F. On the function of haemoglobin in Chironomus. J. Exp. Biol. 18, 197–205 (1942).

Keilin, D. & Wang, Y. L. Haemoglobin of Gastrophilus larvae. Purification and properties. Biochem. J. 40, 855 (1946).

Gorr, T. A., Tomita, T., Wappner, P. & Bunn, H. F. Regulation of Drosophila hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) activity in SL2 cells: identification of a hypoxia-induced variant isoform of the HIFα homolog gene similar. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36048–36058 (2004).

Dickerson, R. E. & Geis, I. Hemoglobin: Structure, Function, Evolution, and Pathology (Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company, 1983).

Berg, J. M., Tymoczko, J. L. & Stryer, L. Biochemistry (WH Freeman & Co., 2002).

Nys, K. et al. Surprising differences in the respiratory protein of insects: A spectroscopic study of haemoglobin from the European honeybee and the malaria mosquito. Biochim. Biophys. Acta- Proteins Proteom. 1868, 140413 (2020).

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Soft. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Lenth, R., Singmann, H., Love, J., Buerkner, P. & Herve, M. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means. (2021).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2016).

Leis, M. & Lazzari, C. R. Blood as fuel: the metabolic cost of pedestrian locomotion in Rhodnius prolixus. J. Exp. Biol. 223, jeb227264 (2020).

Leonardi, M. S., Virrueta Herrera, S., Sweet, A., Negrete, J. & Johnson, K. P. Phylogenomic analysis of seal lice reveals codivergence with their hosts. Syst. Entomol. 44, 699–708 (2019).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Honarbakhsh, S. et al. Ablation in persistent atrial fibrillation using stochastic trajectory analysis of ranked signals (STAR) mapping method. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 5, 817–829 (2019).

Prjibelski, A. D. et al. ExSPAnder: a universal repeat resolver for DNA fragment assembly. Bioinformatics 30, i293–i301 (2014).

Vasilinetc, I., Prjibelski, A. D., Gurevich, A., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembling short reads from jumping libraries with large insert sizes. Bioinformatics 31, 3262–3268 (2015).

Mikheenko, A., Prjibelski, A., Saveliev, V., Antipov, D. & Gurevich, A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 34, i142–i150 (2018).

Hoff, K. J., Lomsadze, A., Borodovsky, M. & Stanke, M. Whole-genome annotation with BRAKER. Gene Predict. 65, 95 (2019).

Kriventseva, E. V. et al. OrthoDB v10: sampling the diversity of animal, plant, fungal, protist, bacterial and viral genomes for evolutionary and functional annotations of orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D807–D811 (2019).

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simão, F. A. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654 (2021).

Prothmann, A. et al. The Globin gene family in arthropods: evolution and functional diversity. Front. Genet. 11, 858 (2020).

Johnson, L. S., Eddy, S. R. & Portugaly, E. Hidden Markov model speed heuristic and iterative HMM search procedure. BMC Bioinform. 11, 1–8 (2010).

Jones, D. T. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 195–202 (1999).

Burmester, T., Klawitter, S. & Hankeln, T. Characterization of two globin genes from the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae: divergent origin of nematoceran haemoglobins. Insect. Mol. Biol. 16, 133–142 (2007).

Thumuluri, V., Almagro Armenteros, J. J., Johansen, A. R., Nielsen, H. & Winther, O. DeepLoc 2.0: multi-label subcellular localization prediction using protein language models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, W228–W234 (2022).

Bologna, G., Yvon, C., Duvaud, S. & Veuthey, A.-L. N-Terminal myristoylation predictions by ensembles of neural networks. Proteomics 4, 1626–1632 (2004).

Sigrist, C. J. A. PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief. Bioinform. 3, 265–274 (2002).

Madeo, G., Savojardo, C., Martelli, P. L. & Casadio, R. SVMyr: a web server detecting co-and post-translational myristoylation in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 434, 167605 (2022).

Maurer-Stroh, S. et al. MYRbase: analysis of genome-wide glycine myristoylation enlarges the functional spectrum of eukaryotic myristoylated proteins. Genome Biol. 5, 1–16 (2004).

Li, S. et al. pCysMod: prediction of multiple cysteine modifications based on deep learning framework. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 617366 (2021).

Ning, W. et al. GPS-Palm: a deep learning-based graphic presentation system for the prediction of S-palmitoylation sites in proteins. Brief Bioinform. 22, 1836–1847 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación [PICT 2018-0537 and PICT 2020-0400], PIBBA CONICET [2022-2024], the Lerner-Grey Fund for Marine Research [2021], the PEPS INEE “Apnoea” (CNRS, France) [2021], and PADI Foundation [2023]. We would like to thank the following people for their help with fieldwork: Bebote Vera, Bocha Rua, Lorna Eder, Carla Di Russo, Iara Safronchik, Juan Pablo Livore, Nuria Vazquez, and Alejandro Cannizzaro. We are particularly grateful to Le Studium Award for Visiting Research, Loire Valley Institute for Advanced Studies, and the “Programa de Becas Externas para Jóvenes Investigadores”- CONICET. We also thank Norberto de Garin for his assistance with SEM. MSL dedicates this work to Simona Albanese for making this and all things possible. This research was the result of several years of Argentine investment in science and technology. Argentine science is now being defunded and dismantled, threatening the continuity of this and many other lines of research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.S.L., C.R.L; methodology, M.S.L, C.R.L, J.M.L.E, J.E.C, G.dR.F., T.S., V.B., D.E., F.S., P.O.; software, J.M.L.E, J.E.C., G.dR.F., T.S., V.B., D.E, P.O.; validation, M.S.L., C.R.L, D.E.; formal analysis, J.M.L.E, J.E.C., G.dR.F., T.S., V.B., D.E., C.R.L.; investigation, M.S.L., C.R.L., J.M.L.E., D.E.; resources, M.S.L., C.R.L, D.E.; data curation, M.S.L, C.R.L, J.M.L.E, J.E.C, G.dR.F., T.S., V.B., D.E.; writing-original draft preparation, M.S.L, C.R.L, J.M.L.E, J.E.C, G.dR.F., T.S., V.B., D.E., F.S., P.O.; writing-review and editing, M.S.L., C.R.L, F.S., P.O.; visualisation, M.S.L., C.R.L., J.M.L.E., J.E.C., T.S., V.B., D.E.; supervision, M.S.L., C.R.L.; project administration, M.S.L., C.R.L.; funding acquisition, M.S.L., C.R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. All necessary permits for the field campaigns and studies were obtained from Subsecretaría de Turismo y Áreas Protegidas and Dirección de Fauna y Flora Silvestre, Chubut Province, and the Administración de Parques Nacionales, Argentina. Seal pups were manually restrained in order to avoid the use of anaesthesia.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Philip Matthews, Sara M. Wilmsen, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michele Repetto. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leonardi, M.S., Latorre-Estivalis, J.M., Crespo, J.E. et al. Host-parasite coevolution leads to underwater respiratory adaptations in extreme diving insects, seal lice (Lepidophthirus macrorhini). Commun Biol 8, 861 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08306-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08306-2