Abstract

A conventional explanation for the existence of species-specific maximum growth temperature (MGT) is the occurrence of irreversible loss of essential cellular functions. Hence the hypothesis that the MGT is the thermal point at which cellular destructive processes outpace constructive processes. For a data-based assessment of this hypothesis, we develop a trait-based model of cellular growth in which key cellular traits are the activation energies of constructive and destructive processes. Using Bayesian inversion on growth curves of archaea, we infer trait values and map them to maximal growth temperatures. We identify the difference between those activation energies as a primary driver of variation in maximum growth temperature. The known yet unexplained correlation between maximal and optimal growth temperatures appears to be underpinned by a linear scaling of these activation energies. This scaling relationship points to the plausibility of adaptation to temperatures exceeding the currently known upper limit (110-120 °C) for microbial growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All organisms stop growing above a certain temperature, and 110–120 °C is about the currently known thermal limit of cellular life1. To explain the existence of upper limits on growth temperature, a conventional argument is that denaturation in the proteome or membrane destabilization occurs, which leads to sudden loss of multiple cellular functions, and ultimately to cell death2. Leuenberger et al.3 have shown that a large fraction of the proteome of Escherichia coli still remained active at the temperature of cellular death, suggesting that denaturation of only a relatively small fraction of the proteome suffices to trigger cell death. Di Bari et al.4 used modeling to show that partial denaturation of the proteome could lead to catastrophic loss of cytoplasmic diffusivity. Even though it is difficult to draw an explicit relation between the death of a cell and the thermal degradation of a specific protein or biomolecule, it appears that the distribution of protein stability, often defined by the free energy of protein unfolding, is key in determining the maximum growth temperature5. It is therefore expected that the evolution of higher maximum growth temperature goes hand-in-hand with increased protein stability5.

Studies of protein stability have led to assume that a tradeoff between enzyme stability at high temperature and enzyme activity at low temperature, mediated by the putatively pleiotropic effect of mutations affecting enzyme flexibility, constrains molecular adaptation to higher environmental temperature6,7. However, this tradeoff hypothesis has been challenged. Elias et al.8 have shown that enzymes found in psychrophiles, mesophiles and thermophiles have indistinguishable rate-temperature dependencies ; and the hypothesis that excess rigidity of thermophilic enzymes would render them inactive at low temperatures has been challenged by the discovery that enzyme stability could be increased without decreasing flexibility9. In addition, properties at the scale of a single-enzyme molecule do not easily scale up to the whole cell. This makes it difficult to causally relate molecular properties to an organism’s maximum growth temperature and to evaluate the existence of a stability-activity tradeoff and its role as an evolutionary constraint at the cellular level. The question is then: how do molecular constraints on high-temperature adaptation of cellular functions translate into life-history constraints on individual cells that shape species adaptation to high temperature?

Here our goal is to relate a species’ maximum growth temperature to cell-scale kinetic parameters and evaluate the hypothesis of a trade-off between the overall kinetics of functional biosynthesis reactions (“constructive” processes), and the kinetics of irreversible thermal degradation of cellular components (“destructive” processes). To this end, we analyze a simplified model of temperature-dependent microbial growth from which the optimal and maximal growth temperatures can be related to within-cell molecular constructive and destructive processes.

Our model of microbial population growth provides a macroscopic description of the kinetics of cellular processes that is structurally similar to Hinshelwood’s model10,11. In the original model by Hinshelwood, the biomass growth rate is assumed to follow first-order kinetics (with respect to biomass) corresponding to the difference between two Arrhenius equations (see ref. 10):

where R = 8.314 J K−1 mol−1) is the ideal gas constant, T (K) is the temperature of the (ectothermic) organism’s medium, E1, E2 are activation energies (J mol−1), and A1, A2 are Arrhenius’s pre-exponential factors, typically related to activation entropy and collision probability for chemical reactions.

Hinshelwood10 observes that A2 must be greater than A1, and proposes that this be explained by A2, linked to the entropy of activation of chemical processes contributing to mortality such as denaturation, being very large owing to the highly ordered state of folded proteins. Here, we contend that this inference focusing on molecular properties omits a crucial element of cellular physiology; the differing scales between the subset of molecules that perform ‘constructive processes’ and the set of molecules which perform functions useful to the cell and that can be degraded, e.g. virtually the entirety of the cell. In addition, the mere rate of the reactions involved in constructive processes does not suffice to determine the effective rate of ‘constructive’ processes (the first term of Eq. (1)) taken as a whole. Different metabolisms may have different degrees of efficiency of coupling between catabolic (energy-yielding) reactions with biomass synthesis (i.e. different metabolic yields)12. For instance, hydrogenotrophic methanogens typically synthesize ≈1 g dry weight of biomass per mole of CH4 produced, while glucose fermenters may synthesize ≈50 g dry weight per mole glucose fermented13. Thus, the rate of constructive processes is function of the product of the rate of catabolic or uptake processes and of their metabolic yield. Last, the entropy of activation of a reaction appears in the pre-exponential factor only if the exponential factor is expressed using the heat (enthalpy) of activation but not the free energy of activation14; whereas the pre-exponential factor otherwise contains only a reaction-independent term relative to collision probability. Hence, we chose in our modeling to add a parameter describing this scaling, and give explicit notations to activation energies, such that the rate of growth of the biomass of a single-species population is given by:

where Ea,c, Ea,m are activation energies (J mol−1) respectively of “constructive” processes with rate \({k}_{c}=A{e}^{-\frac{{E}_{a,c}}{RT}}\) and “destructive” processes with rate \({k}_{m}=A{e}^{-\frac{{E}_{a,m}}{RT}}\) (min−1). Yc is a scaling parameter representing the metabolic coupling that converts the specific constructive kinetic rate kc expressed per mole of active enzymes into a whole-individual biomass specific rate. This scaling parameter encompasses both the conversion of the kinetics of e.g. catabolism into synthesis of new cellular components12 (akin to the growth yield), and the scaling between the mass of the molecular components of the cell that take part in kinetic constructive processes and the mass of the whole cell. While it may be argued that all cellular components perform some function, only a fraction of these functions are “constructive” in nature (e.g. membrane lipids have essential functions which cannot be described as kinetic constructive processes). We assume that both kc and km thermally activated rate constants have the same pre-exponential factor, A, the difference in constructive and destructive (maintenance) kinetics being captured by the metabolic scaling parameter Yc, and by activation energies. This permits us to keep the number of free parameters in our model to be the same as in the original Hinshelwood model, i.e. preserving model structure and complexity while introducing additional mechanistical insight. To permit inference of Yc separately from the pre-exponential factor of kc, the pre-exponential factor of kc is required to be the same as that for km (as substituting \({Y}_{c}{A}_{1}^{{\prime} }\) to A1 would result in under-identifiability of the model). In essence, this is equivalent to setting Yc = A1/A2, and does not change the underlying assumptions of the original Hinshelwood at the condition that the activation energies represent free energies of activation and not enthalpies.

From Eq. (2) one obtains the expression of cardinal temperatures Topt (temperature of maximal growth) and Tmax (maximum temperature of growth) as

In this framework, Tmax appears to be the temperature at which “destructive” processes become faster than “constructive” ones. From the inspection of equations 3a,b, variation in different parameters could lead to increased Tmax: increase in the activation energy of destructive processes Ea,m, decrease of the activation energy of constructive processes Ea,c, and increase in the scaling factor Yc. Based on previous work at the molecular scale, we expect that organisms with a higher maximum growth temperature (that we note MGT when empirically derived, to distinguish it from the model-derived Tmax) would have a higher Ea,m5, reflecting how increased rigidity or stability of proteins might translate into slower overall kinetics of degradation at high temperature9. Additionally, micro-organisms growing at high temperatures are also known to streamline their genome15 and some metabolic pathways16, which may conceivably affect the apparent value of the parameters in our model, yet how this might happen remains elusive.

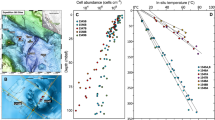

To investigate which of these hypotheses most credibly underlies variation in species-specific maximum growth temperature, and the potential for trade-offs, we estimate the values of the model parameters from a subset of a compiled growth rate database17, comprised of 56 archaea spanning a wide range of growth temperatures, with an empirical maximum growth temperature ranging from 20 to 116 °C. In particular, we analyze the correlations between inferred values of model parameters, and empirical estimates of maximum growth temperature, obtained through standard least mean square fit of the Cardinal Temperature Model with Inflexion (CTMI)18. In order to distinguish between model-calculated Tmax (equation 3b), and the CTMI-empirical estimate of the maximum growth temperature, we refer to the latter as the ‘empirical MGT’.

The model described in Eq. (2) is known to fit microbial growth data quite well11,19, specifically so-called ‘thermal growth curves’ i.e. microbial growth rate in the exponential phase at different temperatures in otherwise ideal growth conditions. An advantage of this model compared to other kinetic models of growth is that it has fewer free parameters2,4,11,20,21. However, obtaining best fit parameter values is known to be difficult11,19. The use of an empirical model (the CTMI) to retrieve empirical cardinal temperatures18 as an intermediate step for parameter inference (as recommended by ref. 19) and state-of-the-art approximate Bayesian methods22 allows us to obtain robust estimation of the model parameters Ea,c, Ea,m, Yc, and A (Methods). Then, we examine correlations between model parameters and the empirical MGT (and empirical optimal growth temperature—OGT) estimated using the CTMI.

Results and discussion

Organisms with higher empirical MGT are found to have both larger activation energy of thermal degradation, Ea,m (Fig. 1A), and larger activation energy of cellular synthesis, Ea,c (Fig. 1B). Both correlations are supported at the significance threshold of 99% (two-sided Wald test with t-distribution p-value). They leave a substantial fraction of variance unexplained in the sample (37% for Ea,m and 62% in Ea,c; Fig. 1A, B; calculated from the squared Pearson correlation coefficient). The maximum growth temperature also correlates with Ea,m − Ea,c at the 99% significance threshold, with a very high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.95; Fig. 2A). In other words, the variance in MGT is better explained by the statistical model in which both activation energies increase with temperature than the model with increasing Ea,m and constant Ea,c. No clear correlation between Yc and empirical MGT is found (Fig. 2B). These observations indicate that variation in the empirical MGT is essentially driven by Ea,m − Ea,c in our model. A linear correlation between Ea,c and Ea,m, whereby Ea,c increases with Ea,m with a slope smaller than one, is found at the 99% significance threshold, leaving only 7% of the sample variance unexplained (R2 = 0.93; Fig. 3). This linear relation corresponds to hyperthermophiles (red circles in Fig. 3) having in general higher values of Ea,c and Ea,m than thermophiles and mesophiles while also having a larger value of Ea,m − Ea,c. In sum, these correlations suggest that increased values of MGT are supported by an increase in Ea,m that is sufficient to compensate the increase in Ea,c.

A Correlation between empirical maximum growth temperature (MGT, K, y-axis, CTMI inference) and the difference between activation energies of destructive and constructive processes (Ea,m − Ea,c, kJ mol−1, x-axis, ABC inference). B Correlation between empirical maximum growth temperature (MGT, K, y-axis, CTMI inference) and the metabolic scaling parameter (Yc, no unit, x-axis, ABC inference). The horizontal error bars are the 95% confidence interval obtained with the ABC inference (not visible when smaller than circle radius).

Correlation between the inferred activation energy of constructive processes (y-axis, kJ mol−1) and the activation energy of destructive processes (x-axis, kJ mol−1). Inferred data points are colored according to the thermophily status of each strain. Green: mesophiles (empirical optimal growth temperature OGT < 45 °C), orange: thermophiles (45 °C < OGT < 80 °C), and red: hyperthermophiles (OGT > 80 °C). The dotted lines are visual aids of slope 1. The solid dark line is the linear regression line, the slope of which is given at the bottom (the 95% confidence interval is calculated using the standard error and the Student’s t-distribution).

Our mechanistic model predicts theoretical cardinal temperatures (as defined in ref. 19) as functions of a small number of parameters (Eqs. (3a, 3b)). This includes the theoretical maximum growth temperature, Tmax (different from the empirical maximum temperature, MGT). Thus we can compare the empirical correlations described above with the predicted correlations between Tmax and the model parameters. The observed correlation between Ea,m and MGT (Fig. 1A) agrees with analysis of Eq. (3b) and with the conventional expectation that organisms adapted to high temperature would have biomolecules more resistant to thermal degradation than organisms living at lower temperature (e.g. ref. 5). Indeed, Ea,m corresponds to a coarse-grained description of the kinetic resistance of biomolecules to thermal degradation. The correlation was thus expected, but this seems to be the first demonstration based on an extensive microbiological dataset. However, the variance left unexplained by the statistical model MGT ~Ea,m (Fig. 1A) suggests that other model parameters interact to influence the maximum growth temperature.

The positive scaling relation between the empirical MGT and Ea,c is intriguing as it contradicts the expectation set by Eq. (3b) that Tmax and Ea,c should correlate negatively. This suggests that adaptation to high temperature might involve a slow-down of destructive processes, more than the acceleration of constructive processes. In addition, the joint increase of Ea,m and Ea,c in organisms with higher MGT might signal a trade-off similar to, and rooted in the stability-activity trade-off hypothesized for enzymes9. However, the processes whose overall rate is scaled by the cellular-level parameter Ea,c may not be limited strictly to enzyme activity. In addition to increased enzymatic activity, physiological determinants of Ea,c may include metabolic network restructuration or membrane plasticity23,24,25.

Beyond the separate analysis of the effect of the activation energies of destructive and constructive processes, our results show that it is, in fact, the difference between Ea,m and Ea,c that sets the maximum growth temperature. This suggests that changes in the kinetics of destructive and constructive processes are both important in the adaptive process that determines a species’ MGT—a finding consistent with the kinetic data on activity and deactivation of individual enzymes26. For the difference Ea,m − Ea,c to increase with temperature when a correlation exists between Ea,m and Ea,c, the rate of increase of Ea,c with Ea,m must be less than one, as evidenced here (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the observed strong linear component with less-than-one slope suggests no upper limit on the difference Ea,m − Ea,c, and thus no theoretical upper limit on MGT (whereas no organism is known to grow above ≈122 °C1). In contrast, one could have expected a physiological tradeoff to constrain Ea,m − Ea,c by forcing a diminishing increase in Ea,m − Ea,c as Ea,m increases. Species-level data like ours do not reveal such a tradeoff. The investigation of physiological constraints on the joint evolution of Ea,m and Ea,c, viewed as individual adaptive traits, that might impose an absolute temperature limit on adaptation, would require finer molecular description of the mechanisms that shape individual variation in the parameters Ea,m and Ea,c.

According to the model (Eq. (3b)), the evolution of MGT might also be shaped by adaptive variation in the scaling parameter Yc. However, there is no significant correlation between Yc and MGT (Fig. 2), suggesting that the overall scaling of metabolic coupling is not directly involved in adaptation to high temperature. This does not mean that the underlying cellular processes compounded in the Yc parameter would remain invariant with MGT. For instance, the growth energy yield may to some extent depend on the Gibbs free energy of reaction, itself a function of temperature12. Similarly, the energy synthesis cost of building biomass, as well as the homeostatic energy expenditure are allegedly sensitive to temperature. Progress on these questions warrants experiments to quantify these costs and their variation with growth temperature.

The scaling parameter Yc also compounds the scaling between the molecular components of the cell that perform constructive chemistry, e.g. ribosomal or ‘metabolism’ proteins and the cell components that increase their maintenance demand (e.g. demand for chaperone proteins) with temperature. Others have used modeling of the dynamics of allocation of biomass to different cellular components to show that optimal growth strategies at high temperature correspond to prioritizing chaperone proteins which mitigate protein unfolding27. We contend that in Hinshelwood-type model such as ours, increased synthesis of chaperones at high temperatures contribute the the maintenance Arrhenius term (i.e. km corresponds to the rate that constructive processes need to match in order to mitigate temperature stresses), consistent with our finding that Yc remains relatively constant over a wide range of MGTs. As a consequence, this hinders thermodynamic interpretation of Ea,m.

The relative constancy of Yc in our inference dataset sets an unexpected expectation for the original Hinshelwood model (Eq. (1)). Our model maps to the Hinshelwood model via Yc = A1/A2. Thus, our finding that Yc is relatively constant over our dataset (or rather exhibit no or weak correlation with other parameters as well as with MGT) may set the expectation that a correlation be found between A1 and A2 when performing inference of the parameters of the original Hinshelwood model. This is indeed observed if we replicate our inference pipeline for the parameters of the original Hinshelwood model (Eq. (1)) rather than of our model (Methods; Supplementary Fig. 8). Our addition of Yc in the Hinshelwood model, with the assumption of equal pre-exponential factor for kc and km implies that parameter A may not be related to activation entropy. Thus, we should not expect to observe a correlation between A and Ea,m in our model, whereas the original Hinshelwood model sets the expectation of a correlation between A2 and E2, known as the ‘entropy–enthalpy compensation’ and observed by others10,28,29. Indeed no linear correlation is found in our inferred set of A and Ea,m (\({E}_{a,m}\propto \log A\): p = 0.26; two sided Wald test), while being present (albeit with low correlation coefficient) in our pipeline replication for the original Hinshelwood model (\({E}_{2}\propto \log {A}_{2}\): p = 0.02, R2 = 0.11; two sided Wald test). Together, these results support the consistency and mechanistical advantage in our choice of adding parameter Yc and setting the same pre-exponential factor for kc and km in our model relative to the original Hinshelwood formulation.

Our model also sheds light on the apparent correlation18 between the cardinal temperatures MGT and OGT (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for archaea and Supplementary Fig. 5 for the dataset from ref. 17). From Eq. (3b) we have

For microbial populations with positive growth, Eq. (1) implies \(({\ln}\,({E}_{a,c}/{E}_{a,m}))/(R\,{\ln}\,({Y}_{c})) > 0\). Therefore Tmax − Topt should increase with Topt, as verified with empirical OGT and MGT, see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 6, with the caveat of high residual variance. Because Ea,c, Ea,m, and Yc vary across organisms growing at different temperatures, it is not straightforward that Eq. (4) should result in an apparent linear correlation between MGT and OGT. However, the typical value of \(({\ln}\,({E}_{a,c}/{E}_{a,m}))/({\ln}\,({Y}_{c}))\) being very small compared to one (approximately 0.03 with standard deviation ≈ 0.002, as calculated from the values reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), a dominant linear component with a slope around one is observed (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 5). Moreover, Ea,m and Ea,c are correlated and the ratio Ea,c/Ea,m varies little across the range of MGT in our sample (the ratio changes by ≈ 3% over the range of MGT). This reinforces the expectation of a linear correlation between the Topt and Tmax, and consequently between empirical MGT and OGT. Thus the origin of the correlation between MGT and OGT that puzzled others18 can be traced back to the correlation between Ea,c and Ea,m.

The minimum growth temperature, mGT, under which growth is no longer observed, also appears to correlate with the OGT18 (see Supplementary Fig. 6). Could our model shed light on this correlation like it does on the one between OGT and MGT? The mGT is not a growth temperature limit of the same nature as the MGT (Rosso et al.18, define the mGT as the temperature below which growth is no longer ‘observed’, and the MGT as the temperature above which growth no longer ‘occurs’). Indeed, the MGT delineates an irreversible limit, whereas microbes exposed to temperatures below their mGT may grow again if cultured at higher temperatures. In the terms of Hinshelwood-type models, vanishingly slow growth due to the asymptotic behavior of constructive processes should explain the mGT, while exponential increase of irreversible degradation explains the MGT. Hinshelwood-type models such as ours do not explicitly predict a minimum growth temperature, instead Tmin is defined as the temperature at which growth is slower than an arbitrary threshold ϵ (in units of min−1), e.g. such that kg(Tmin) < ϵ (or kg(Tmin) < ϵkg(Topt), refs. 19,28). To solve kg(Tmin) = ϵ for Tmin, one assumes that Yckc(Tmin) ≫ km(Tmin), resulting in

Equation (5) shows that mGT might be expected to be correlated to MGT (and OGT) via Tmin being a linear function of Ea,c (itself correlated to MGT; Fig. 1B), while at the same time A and Yc being not or weakly correlated with cardinal temperatures. The coefficient of correlation between mGT and MGT is smaller than between OGT and MGT (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6; see also ref. 18), consistent with our finding that the difference Ea,m − Ea,c more strongly determines MGT than Ea,c alone, of which Tmin is a linear function.

An important limit of analyzing models of thermal growth curves to tackle adaptation of organisms to their environmental temperature, is that laboratory conditions used to obtain growth data markedly differ from environmental conditions under which natural selection may occur. Indeed, thermal growth curves represent maximal growth rates at different temperatures and are as such well represented using first order kinetics as in our model. However, fitness is formally relative to the steady-state between the microbial population and its environment30. Thus, rigorously, tackling the question of adaptation requires considering second-order kinetics relative to biomass via an environmental trade-off. Hence, analyses such as ours cannot explicitly relate changes in parameter ‘trait’ values to fitness, and future studies may build up on simple Hinshelwood-type models to bridge the gap between thermal growth curves and natural selection.

Our quantitative analysis is limited to 56 archaeal species, yet the correlations between Ea,m and Ea,c and the relative constancy of Yc extend across organisms belonging to the different domains of life (Supplementary Fig. 7). Applications of microbial growth models often struggle with the estimation of kinetic parameters and of their dependency to temperature. The point was made emphatically in the context of biogeochemical modeling31, and extends to models aimed at assessing the potential for extreme (and extraterrestrial) environments to support microbial life32,33. Our results provide constraints on the parameter space that is effectively explored by known organisms. They show that parameters that determine the temperature range for organismal growth, and the actual growth rate as a function of temperature, do not vary independently, but are instead tightly correlated. The correlations reported here improve our capacity to constrain mechanistic models that include microbial processes for the analysis and prediction of biogeochemical responses to temperature change.

Methods

Model equations

Here, we recall the model equations from the main text. Growth rate (min−1) is given by34:

with R = 8.314 J K−1 mol−1 the ideal gas constant, T (K) the environmental growth temperature, and Ea,c, Ea,m are activation energies (J/mol) of ‘constructive’ processes and ‘destructive’ processes respectively. Yc scales the enzyme-specific rate \(A{e}^{-\frac{{E}_{a,c}}{RT}}\) with the whole organism’s biomass specific rate kg. Cardinal temperatures are determined by solving kg = 0 and \({k}_{g}^{{\prime} }=0\):

Inference of model parameters from experimental data

The main dataset used in this study is a compilation of population growth rates measured at different temperatures by Corkrey et al.17. Following recommendations in Grimaud et al.19, a first fit is made using the empirical Cardinal Temperature Model with Inflexion (CTMI)18 on the growth rate versus temperature data for each strain

with

under the condition35

such that Φ is positive. mGT, OGT, and MGT are the cardinal temperatures, respectively the minimum growth temperature, the optimal growth temperature, and the maximum growth temperature. Fitting the CTMI is done using standard least mean square optimization with Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm implemented in python’s SciPy package36. In doing so we obtain estimates of the cardinal temperatures OGT and MGT as well as the maximal growth rate μopt.

The parameters of the growth rate model, Eq. (12), are notoriously difficult to estimate from fitting the model to the data11,18,19, due mainly to intrinsic correlations between the parameters, which hampers the convergence of traditional optimization approaches. Here, we combine estimates of cardinal temperatures and growth rate, as well as the data arrays \({\{{T}_{i},{k}_{g,i}\}}_{j}\) (where j is the studied strain) to fit the parameters of Eq. (12) through an Approximate Bayesian Computation-Sequential Monte Carlo (ABC-SMC) procedure implemented in python’s pyABC package22. This allows us to bypass the need for an explicitly-defined likelihood and thus to use of a combination of growth data (\({\{{T}_{i},{\mu }_{i}\}}_{j}\)) and cardinal quantities (\({\{{\mbox{OGT}},{\mbox{MGT}},{\mu }_{{\rm{opt}}}\}}_{j}\)). Standard approaches such as Monte-Carlo Markov chains (MCMC) require the definition of a tractable likelihood \(P({\{{T}_{i},{\mu }_{i}\}}_{j}| {{{\mathbf{\theta }}}}_{j})\) (where θj is the vector containing parameter values), which may be challenging (or even impossible) when using quantities that are themselves point estimates (\({\{{\mbox{OGT}},{\mbox{MGT}},{\mu }_{opt}\}}_{j}\)).

ABC-SMC parameter inference, while being likelihood-free, requires the definition of a distance function, which is here constructed to facilitate convergence:

In this equation, kg,θ is the vector of simulated growth rates with parameters θ and μ is the vector of the observed growth rates. \({\hat{\mu }}_{opt},\,\hat{\,{\mbox{OGT}}\,},\,\hat{\,{\mbox{MGT}}\,}\) are cardinal points obtained by fitting the CTMI to model outputs kg,θ. μopt, OGT, MGT are the CTMI cardinal points fitted on the observations. \({\bar{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}\) is the mean of the observed μ.

ABC-SMC parameter inference was performed for each of the 56 selected strains using the same prior distribution (Supplementary Table 1). ABC-SMC runs were performed in parallel on 12 cpu-cores, using pyABC. For each ABC-SMC step, we set the goal of accepted particles (parameter vector proposal) to 50. Stopping conditions for the inference were that the mean distance of accepted particles is less than 0.5 or the 101nth step is reached or the run time exceeds 15 min.

Using ABC-SMC for inference requires having an a priori range of credible values for the parameters of the model. Conveniently, these values can be somewhat constrained. For example, one might draw a range of credible values of Ea,m from enzyme activity experiments in e.g. Daniel et al.26 constrain the activation energy for enzyme activity below 70 kJ mol−1. The empirical estimate of the maintenance energy in Tijhuis et al.37 has an Arrhenius-like form with activation energy also around this value, while others report values of the activation energy of protein denaturation greater than ≈130 kJ mol−1[38] and estimates in Daniel et al.26 also fall around 130 kJ mol−1. The values of A and Yc can also be constrained from fitting the CTMI model on the data combined with (Eqs. (7a, 7b)) and fitting a line to the data when T < OGT in the \({\ln}\,{k}_{g}\propto 1/T\) space. Not all experiments compiled in Corkrey et al.17 have sufficient data to do so, but a ballpark estimate is obtained and used as a prior. Another route is to use A = kBT/h, with kB = 1.38 × 10−23 J K−1 the Boltzmann constant and h = 6.626 × 10−34 J s the Planck constant, which is of the order of 1012 s−1 at room temperature, roughly of the same order of what is obtained by fitting data at low temperatures. Note that here, inference is performed assuming that A is independent of temperature for computational tractability. This assumption affects how the model fits the data at low temperatures but not the cardinal temperatures (see Eqs. (7a, 7b)). The parameter Yc can be constrained from other sources, by considering the two general phenomenons that it encompasses: metabolic energy coupling (or growth yield), and the scaling of kinetic functional enzymes. The sample that we examine is composed of Archaea, many of which are chemolithoautotrophs (reduce carbon dioxide into biomolecules by sourcing chemical energy from mineral reactions). For instance, Kleerebezem and Van Loosdrecht12 estimate the growth yield of hydrogenotrophic methanogens to be ≈0.03 (per mole dihydrogen). The scaling of enzymes to the whole cell is perhaps more difficult to come by, however ref. 32 estimated that the ratio of catabolic enzyme to whole cell biomass was ≈2 × 10−5 from growth data of Methanococcus villosus39. From this, it appears that for Archaeas, Yc should generally if not systematically less than unity (Yc < 1). The adopted priors are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Datasets

We use the dataset published by Corkrey et al.17, consisting in growth rates measured at different temperatures for 1627 strains of ectothermic Eukaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea. Our focus is on the adaptation of organisms living at very high temperatures. From this dataset, we select experiments that contain 5 or more data points to attempt for fit the empirical CTMI model using standard least squares regression. This reduced the data set to 948 strains. Then, we discard cases where the inference of cardinal temperatures revealed that the species-specific data contained only 2 points or fewer above the temperature optimum OGT, reducing the dataset to 419 strains. Additionally, we removed cases where the condition OGT > (MGT + mGT)/2 (ref. 35) is not met, corresponding to failure of the CTMI to fit the growth curve. As a redundant measure, we also tracked cases where the least square regression could not yield a full-rank jacobian matrix at the solution, as well as cases where the solution converged to an obviously wrong minimum as determined by the criterion MGT − OGT ≤ 0.1 K. This resulted in a ‘total’ dataset (containing Eukaryotes, Bacteria and Archaea) of 317 strains. Since the hyperthermophiles (OGT > 80 °C) reported in Corkrey et al.17 are essentially Archaea, we limited our study to the archean domain. This resulted in a subset of 56 archaeal strains (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Fit quality

The percent residual error ε of the ABC inferred model compared to the CTMI inference results is calculated following for cardinal value ω (OGT,MGT or μopt):

The fit quality is overall variable, but the cardinal temperatures are well retrieved, as confirmed by analysis of residuals (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). The maximum growth rate μopt on the other hand is often poorly retrieved in our model even with intermediary step of using the CTMI model to extract cardinal temperatures and use them for inference, as noted by previous authors18,19. The details of the growth curves are not well captured by such so-called “coarse-grained” models with a low number of parameters. The fit quality is noticeably poorer for growth rates at temperatures lower than the optimum (Supplementary Fig. 1), which indicates that the model Eq. (12) adopted here is not best suited for the T < OGT regime. It is worth noting that Hinshelwood-type models do not predict the existence of a minimal temperature of growth stricto sensu as kg decreases asymptotically to 0 as T decreases (Eq. (12)). The general trends of the growth curves, especially regarding the predicted OGT and MGT and growth rates at temperatures between these two values are however robust and allow for a discussion of the model parameters (Eqs. (7a, 7b)). With these limitations in mind, we focus our analyses on growth in the T > OGT regime and discuss the relation between the inferred parameter values and the upper temperature limit for growth. Our focus on the relationship between model parameters and the maximum and optimal growth temperatures guarantees that the parameter inference is informative and robust.

Inference of parameters of the original Hinshelwood model

We also replicated our inference pipeline using the original Hinshelwood model (Eq. (1) in Main Text, recalled below):

Thus, we inferred A1, A2, E1 and E2 instead of our Yc, A, Ea,c and Ea,m. To this end, we amended our prior distributions such that the one used for A2 is the same as the one we used for A (Supplementary Table 1); and the prior for A1 is obtained by multiplying the bounds for the priors of A with those for Yc, i.e \({A}_{1} \sim {\log }_{10}U[4,10]\). We verified that the correlations that we found for the activation energies as inferred using our model were equivalently found in the inferred parameters of the original Hinshelwood model (see Supplementary Table 4).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Growth data used in this article, originally compiled and made public by Corkrey et al.17 is available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153343.s004. Estimated parameter value data used in the figures of this paper are available in Supplementary Table 3.

Code availability

The code supporting ABC inference (Klinger et al.22) is publically available at https://github.com/icb-dcm/pyabc. Custom code for analysis and figure plotting, as well as machine-readable data table containing our inference results is archived on Zenodo.

Change history

28 November 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09197-z

References

Takai, K. et al. Cell proliferation at 122 °C and isotopically heavy CH4 production by a hyperthermophilic methanogen under high-pressure cultivation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10949–10954 (2008).

Dill, K. A., Ghosh, K. & Schmit, J. D. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17876–17882 (2011).

Leuenberger, P. et al. Cell-wide analysis of protein thermal unfolding reveals determinants of thermostability. Science 355, eaai7825 (2017).

Di Bari, D. et al. Diffusive dynamics of bacterial proteome as a proxy of cell death. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 93–102 (2023).

Somero, G. N. Proteins and temperature. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 43–68 (1995).

Wang, X., Minasov, G. & Shoichet, B. K. Evolution of an antibiotic resistance enzyme constrained by stability and activity trade-offs. J. Mol. Biol. 320, 85–95 (2002).

DePristo, M. A., Weinreich, D. M. & Hartl, D. L. Missense meanderings in sequence space: a biophysical view of protein evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 678–687 (2005).

Elias, M., Wieczorek, G., Rosenne, S. & Tawfik, D. S. The universality of enzymatic rate–temperature dependency. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 1–7 (2014).

Miller, S. R. An appraisal of the enzyme stability-activity trade-off. Evolution 71, 1876–1887 (2017).

Hinshelwood, C. N. The chemical kinetics of the bacterial cell. Oxford Press. 1, 255 (1946).

Noll, P., Lilge, L., Hausmann, R. & Henkel, M. Modeling and exploiting microbial temperature response. Processes 8, 121 (2020).

Kleerebezem, R. & Van Loosdrecht, M. C. A generalized method for thermodynamic state analysis of environmental systems. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 1–54 (2010).

Thauer, R. K., Jungermann, K. & Decker, K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41, 100–180 (1977).

Glasstone, S., Laidler, K. J. & Eyring, H. The Theory of Rate Processes, The Kinetics of Chemical Reactions, Viscosity, Diffusion and Electrochemical Phenomena. (McGRaw-Hill Book Co., New York and London, 1941).

Sabath, N., Ferrada, E., Barve, A. & Wagner, A. Growth temperature and genome size in bacteria are negatively correlated, suggesting genomic streamlining during thermal adaptation. Genome Biol. Evolut. 5, 966–977 (2013).

Engqvist, M. K. M. Correlating enzyme annotations with a large set of microbial growth temperatures reveals metabolic adaptations to growth at diverse temperatures. BMC Microbiol. 18, 177 (2018).

Corkrey, R. et al. The biokinetic spectrum for temperature. PLoS ONE 11, e0153343 (2016).

Rosso, L., Lobry, J. & Flandrois, J.-P. An unexpected correlation between cardinal temperatures of microbial growth highlighted by a new model. J. Theor. Biol. 162, 447–463 (1993).

Grimaud, G. M., Mairet, F., Sciandra, A. & Bernard, O. Modeling the temperature effect on the specific growth rate of phytoplankton: a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 16, 625–645 (2017).

Corkrey, R. et al. Protein thermodynamics can be predicted directly from biological growth rates. PLoS ONE 9, e96100 (2014).

Sawle, L. & Ghosh, K. How do thermophilic proteins and proteomes withstand high temperature? Biophys. J. 101, 217–227 (2011).

Klinger, E., Rickert, D. & Hasenauer, J. pyABC: distributed, likelihood-free inference. Bioinformatics 34, 3591–3593 (2018).

Angilletta, M. J. Thermal Adaptation a Theoretical and Empirical Synthesis. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009).

Kontopoulos, D., Smith, T. P., Barraclough, T. G. & Pawar, S. Adaptive evolution shapes the present-day distribution of the thermal sensitivity of population growth rate. PLOS Biol. 18, e3000894 (2020).

Flamholz, A., Noor, E., Bar-Even, A., Liebermeister, W. & Milo, R. Glycolytic strategy as a tradeoff between energy yield and protein cost. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10039–10044 (2013).

Daniel, R. M. et al. The molecular basis of the effect of temperature on enzyme activity. Biochem. J. 425, 353–360 (2010).

Mairet, F., Gouzé, J.-L. & de Jong, H. Optimal proteome allocation and the temperature dependence of microbial growth laws. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 7, 14 (2021).

Grimaud, G. M. Modelling the Temperature Effect on Phytoplankton: From Acclimation to Adaptation. Theses (Université Nice Sophia Antipolis, 2016) https://theses.hal.science/tel-01383294.

Liu, L., Yang, C. & Guo, Q.-X. A study on the enthalpy–entropy compensation in protein unfolding. Biophys. Chem. 84, 239–251 (2000).

Metz, J., Nisbet, R. & Geritz, S. How should we define ‘fitness’ for general ecological scenarios? Trends Ecol. Evolut. 7, 198–202 (1992).

Louca, S. et al. Circumventing kinetics in biogeochemical modeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 11329–11338 (2019).

Affholder, A., Guyot, F., Sauterey, B., Ferrière, R. & Mazevet, S. Bayesian analysis of Enceladus’s plume data to assess methanogenesis. Nat. Astron. 5, 1–10 (2021).

Higgins, P. M. & Cockell, C. S. A bioenergetic model to predict habitability, biomass and biosignatures in astrobiology and extreme conditions. J. R. Soc. Interface 17, 20200588 (2020).

Affholder, A. Coupling Biological, Interior and Atmosphere Models to Infer Habitability and Biosignatures. Theses, (Sorbonne Université, 2022).

Bernard, O. & Rémond, B. Validation of a simple model accounting for light and temperature effect on microalgal growth. Bioresour. Technol. 123, 520–527 (2012).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Tijhuis, L., Van Loosdrecht, M. C. & Heijnen, J. A thermodynamically based correlation for maintenance Gibbs energy requirements in aerobic and anaerobic chemotrophic growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 42, 509–519 (1993).

Maffucci, I., Laage, D., Sterpone, F. & Stirnemann, G. Thermal adaptation of enzymes: impacts of conformational shifts on catalytic activation energy and optimum temperature. Chemistry 26, 10045–10056 (2020).

Taubner, R.-S. et al. Biological methane production under putative enceladus-like conditions. Nat. Commun. 9, 748 (2018).

Acknowledgements

A.A. and R.F. acknowledge support from France Investissements d’Avenir programme (grant numbers ANR-10-LABX-54 MemoLife and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL) through PSL-University of Arizona Mobility Program, and from the US National Science Foundation, Dimensions of Biodiversity (DEB-1831493), Biology Integration Institute-Implementation (DBI-2022070), Growing Convergence in Research (OIA-2121155), and National Research Traineeship (DGE-2022055) programmes. We thank Mruthyunjay Kubendran-Sumathi for fruitful discussion and sharing of relevant bibliographical references.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A., F.G. and R.F. designed the model and the statistical study. A.A. performed the parameter inference, analyzed the model and inference outputs and. The paper was written through contributions of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Ghjuvan Micaelu Grimaud, Alessandro Paciaroni, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Affholder, A., Ferrière, R. & Guyot, F. Activation energies of both constructive and destructive cellular biochemistry determine maximum growth temperature in archaea. Commun Biol 8, 1507 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08389-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08389-x