Abstract

Symbiotic relationships shape the evolution of organisms. Fungi in the genus Escovopsis share an evolutionary history with the fungus-growing “attine” ant system and are only found in association with these social insects. Despite this close relationship, there are key aspects of Escovopsis evolution that remain poorly understood. To gain further insight into the evolutionary history of these unique fungi, we delve deeper into Escovopsis’ origin and distribution, considering the largest sampling, so far, across the Americas. Furthermore, we investigate Escovopsis’ trait evolution, and relationship with attine ants. We demonstrate that, while the genus originated approximately 56.9 Mya, it only became associated with 'higher attine' ants in the last 38 My. Our results, however, indicate that it is likely that the ancestor of Escovopsis lived in symbiosis with early-diverging fungus-growing ants. Since then, the fungi have evolved morphological and physiological adaptations that have increased their reproductive efficiency, possibly to overcome barriers mounted by the ants and their other associated microbes. Taken together, these results provide new clues as to how Escovopsis has evolved within the context of this complex symbiosis and shed light on the evolutionary history of the fungus-growing ant system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Symbiosis is a major driver of the evolution of organisms1,2,3,4,5. Although exploring the origin of symbiotic interactions is challenging6, it can provide critical insights into the evolution of symbiotic adaptations7. This is the case of fungus-growing ants (subfamily Myrmicinae, tribe Attini, subtribe Attina, hereafter attines) whose evolutionary success relies on the cultivation of Basidiomycota fungi for food8,9,10. Fungal cultivation in attines originated approximately 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous9. Since then, attines and their cultivated fungi have undergone a long and intricate process of co-diversification, shaping the evolutionary trajectories of both partners8,10,11. While the cultivated fungus is the core of this symbiotic system, attine colonies also harbor a rich and diverse community of other microorganisms12,13,14,15,16. These additional microbes engage in complex interactions within the colony, many of which remain poorly understood17.

Fungi in the genus Escovopsis (Ascomycota: Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae) are also common residents of fungus-growing ant gardens, and while most Escovopsis species may cause opportunistic infections with little impact on attine colony fitness17,18,19, some strains of E. weberi were reported as virulent parasites of the mutualistic fungi cultivated by them20,21,22,23,24,25,26. Because they can have detrimental colony-level effects, parasites living in social insect environments are extremely important to the evolutionary success of social insects27,28,29. Therefore, the discovery of Escovopsis within attine ant colonies fundamentally altered our understanding of the system’s evolution and redirected subsequent research on fungus-growing ants in the way that many researchers drew their conclusions based in the hypothesis that the ant system was influenced by a single highly specialized parasite22,30. Recently, researchers have estimated the origin of Escovopsis31,32; however, when this fungal genus became associated with the ants and how it has evolved since that event remain poorly understood.

The evolutionary history of Escovopsis is based on the underlying assumption that species of this genus co-evolved with attine ants as specialized parasites of their mutualistic fungus, leading to broad-scale co-cladogenesis of Escovopsis, the cultivars, and the ants21,22,23,24,25,33,34. Nonetheless, the data set of the three organisms that make up the tripartite symbiosis is incomplete in the literature, i.e., there are very few cases in which the three organisms (ants, mutualistic fungus, and Escovopsis) were isolated from the same ant colony. Most data sets have ant samples but no Escovopsis strains and cultivar samples, or data sets that have the cultivars but no Escovopsis strains or ant samples, or data sets with Escovopsis strains but no ant or cultivar samples. Furthermore, a recent molecular and taxonomic study demonstrated that what was formerly known as Escovopsis comprises five groups of fungi from the same family: the genera Escovopsis, Luteomyces, and Sympodiorosea, and two unidentified clades35. Consequently, the evolution of Escovopsis in the tripartite fungus growing ant model is a topic that deserves more comprehensive studies.

Escovopsis is a diverse genus with high morphological diversity36 and, unlike its sister clades35, it forms vesicles on the tips of its conidiophore branches (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for further explanation of morphological concepts). Curiously, the shape of these structures is a diagnostic character throughout the Escovopsis phylogeny36 and it is ecologically important because it is directly related to the formation of phialides, which are responsible for producing asexual reproductive structures (conidia) (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition to morphological, physiological, and phylogenetic differences, Escovopsis also differs from its sister clades in terms of gene content35,36,37,38, which may be a result of the genus's interactions with other organisms within the system. There are currently 24 formally described Escovopsis species36,38,39,40,41,42. However, despite the advances in the description of the diversity36 and the genomics31,32 of this fungal genus, little is known about its distribution and patterns of association between Escovopsis spp., the ants, and their cultivars. In light of these facts, it is imperative to evaluate the phylogeographic distribution of Escovopsis, re-evaluate its evolutionary history as well as the history of its co-evolution, if any, with both attine ants and their fungal cultivars.

Beyond evolutionary history and phylogeography, we also know relatively little about how, or whether, Escovopsis spp. have adapted in response to their associations with the fungus-growing ant system. Symbionts, particularly those that are parasites, evolve mechanisms to overcome the defenses of their hosts7,43,44,45 and, in turn, hosts evolve mechanisms to control symbiont populations, often avoiding, repelling, and/or killing those that are parasites46. Reciprocal adaptations of both the hosts and parasites to pressures generated by these interactions promote the evolution of behavioral, physiological, and morphological traits in both organisms47,48,49,50. In the specific case of the fungus-growing ant system, the colonies of these social insects are complex superorganisms that have many defenses against the entry of alien microorganisms51. Considering that Escovopsis species have lived for millions of years as symbionts of the attines' fungus-gardens, it is likely that species in this genus have evolved numerous adaptations to overcome the defenses of the ants, their fungal cultivars, and other associated microbes. However, while genomic analyses have revealed that, despite genome reduction, Escovopsis species have retained the potential to make metabolites that may be key for defense31,32, little else is known about other adaptations that may have influenced the ability of members of the genus to interact with other organisms in the fungus-growing ant system.

In this study, we assembled the largest collection to date of Escovopsis strains isolated from colonies of multiple attine ant species in different biomes across eight countries of the Americas (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, and The United States), to investigate the evolutionary history of this fungal genus. We provide evidence concerning: (i) when, after its origin, Escovopsis became associated with attine ant colonies, (ii) the phylogeographical distribution of Escovopsis, (iii) correlation between the phylogeny of Escovopsis and that of attine ants, and (iv) morphological and physiological adaptations that have arisen in this genus over evolutionary time. Taken together, our results answer key questions related to the evolutionary history of Escovopsis, which in turn will allow researchers to better understand the evolutionary history of the fungus-growing ant system as a whole.

Results

Escovopsis is associated with only some fungus-growing ant genera

Based on a collection of 309 Escovopsis strains, we found that the fungus is associated with “higher” attine ants in the genera Atta, Acromyrmex, Mycetomoellerius, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex (we were not able to collect colonies of the higher attines Amoimyrmex and Xerolitor), and with the “lower” attine ant genus Apterostigma (Fig. 1A, B). Based on extensive sampling over the course of the last three decades, there is no evidence to date that Escovopsis is associated with the other fungus-growing ant genera, which are instead colonized by its sister clades (e.g., Luteomyces and Sympodiorosea)35. There is no strict co-cladogenesis between Escovopsis and fungus-growing ant species (Fig. 1A, B). However, the most derived Escovopsis clade (clade I) is more often associated with the most derived attine clades, the leaf-cutting ant genera Atta and Acromyrmex (Fig. 1A). Clades II and III are mostly associated with Paratrachymyrmex (Fig. 1A), and the most basally diverging Escovopsis clade (Clade IV) is mostly associated with Apterostigma (Fig. 1A). While no Escovopsis strains from Clade IV were found in association with fungus gardens of Atta and Acromyrmex, some strains isolated from fungus gardens of Apterostigma spp. (NGL075, 080, 081, 083, and LESF 878) are placed in the most derived clade of Escovopsis (Fig. 1A, B). Interestingly, the ant genera Atta, Acromyrmex, and Paratrachymyrmex harbor the greatest diversity of Escovopsis, though this could be based on uneven sampling effort.

A Escovopsis - attine ant co-cladogenesis, with ant phylogeny (based on52) on left and Escovopsis phylogeny on right. Lines indicate the Escovopsis strains associated with Atta (green), Acromyrmex (blue), Apterostigma (red), Mycetomollerius (orange), Paratrachymyrmex (brown), and Sericomyrmex (gray). B Phylogeographic distribution of Escovopsis in Central and South America. The names of each country and region represented on the map are placed in the lower right corner of the figure. Lines plotted on the map indicate the origins of the colonies from which Escovopsis strains were isolated. Percentage values next to each geographic point indicate the percentage of strains isolated from each region with respect to the total number isolated strains (n=309). Mexico (n=2 strains) and the USA (n=1 strain) are not represented in the figure due to scaling. The stars (red = Mexico and blue = USA) at the end of the names of the strains LESF 297, 865, 892 indicate the species isolated from these countries. The Escovopsis phylogeny is divided into clades [Clade I (beige), Clade II (purple), Clade III (yellow), Clade IV (orange)] based on the type of conidiophore and vesicle formed by the species corresponding to each clade: (a) Conidiophore with cylindrical vesicles (Clade I); (b) Conidiophore with clavate vesicles (Clade II); Conidiophore with globose vesicles (Clade III, IV); and Conidiophore with swollen cells (red arrow-Clade IV). Values on tree nodes indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities. Question marks at the end of names in the Escovopsis phylogeny refer to miss data of the collection site or ant species to which said strain is associated. Ant tree topology in A is based on52. Map in B was modified from ©d-maps.com (http://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=1405&lang=es).

Escovopsis is a late-arriving symbiont in the evolution of higher fungus-growing ants

As previously reported31,32, our divergence time analysis indicates that Escovopsis originated approximately 56.9 Mya (Fig. 2, clade 12), soon after the estimated origin of the attine ant-fungus mutualism, 66 Mya10,52. Escovopsis subsequently diversified into four major clades (Fig. 2, nodes 13, 15, 17, and 18). The crown age of the most basally diverging clade is approximately 39.1 Mya (Fig. 2, node 13), while the crown age of the most recent clade (Fig. 2, node 18) is approximately 17.2 Mya. Therefore, considering that Escovopsis is only associated with Atta, Acromyrmex, Apterostigma, Mycetomoellerius, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex, and considering the crown ages of these ant clades8,10,52, it is likely that Escovopsis became associated with colonies of Apterostigma first (approx. 38 Mya), and that it subsequently became associated with colonies of Mycetomoellerius, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex (approx. 28 Mya), and even later with colonies of Atta and Acromyrmex (approx. 18 Mya53).

Chronogram was constructed based on the tree obtained in the maximum likelihood analyses. A Calibration was based on seven nodes (red circles) from Hypocreales previously calibrated by Sung et al. (2008). B Extended region of the Hypocreales. Calibrated nodes in the Hypocreaceae are indicated by blue circles. C Ages in millions of years (Mya) of each calibrated node. Scales of each chronogram in Mya. D Ant phylogeny based on52. Dotted lines indicate the Escovopsis species associated with the ant genera.

Escovopsis is distributed across Central and South America

Our findings reveal that Escovopsis is distributed throughout much of the geographic range of fungus-growing ants (Fig. 1B). There is no clear geographic pattern to the distribution of the genus, but it is important to note that most Escovopsis strains used in our study were isolated from Panama and Brazil, where there have been substantial sampling efforts, while only a few were isolated from Argentina, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago and The United States (USA). The other countries across the Americas are not represented in our collection, making our understanding of the phylogeographic distribution of these fungi fragmentary. Even so, samples from one small locality in Panama contain remarkable phylogenetic diversity, including the most derived Escovopsis clade (Fig. 1). A similar level of diversity is present in samples collected from across all of Brazil, an area much larger than that sampled in Panama (Fig. 1). Consequently, these results are likely influenced by differences in sampling effort.

Morphological and physiological changes of Escovopsis

Morphometric and character-state reconstruction analyses (Fig. 3) reveal that the vesicles of Escovopsis have changed their shape during the diversification of the genus, from globose (least derived Escovopsis clades in gray—Fig. 3A) to cylindrical (the most derived clades in green—Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the most derived clades, containing E.weberi, E. peniculiformis, E. breviramosa, and E. gracilis, form the thinnest and most elongated vesicles, “filiform” vesicles that do not even have the appearance of vesicles and can form phialides, specialized cells that produce conidia, both on the vesicles and on aerial mycelium (See Fig S1 for morphological concepts).

A Ancestral-state reconstruction of the vesicles. Strains in the basal clades have globose vesicles that change into cylindric vesicles in strains of the more derived clades. The asterisk in the tree and the figure next to the tree (gray and green) indicate vesicle shift from globose to cylindrical. (i) Representative drawings of cylindrical (top) and globose (bottom) vesicles, (ii) Microscopy of cylindrical (top) and globose (bottom) vesicles, and (iii) Microscopy of conidiophores with and without swollen cell (red arrow). Scale bars of the microscopic structures (ii) and (iii) = 10 μm. B Ancestral state reconstruction of (i) growth rate, (ii) conidia production, and (iii) conidia viability. The asterisks and the figure next to the tree indicate physiological shifts. More derived clades (green and light-green) grow faster, produce more conidia, and form more viable conidia than less derived clades (green, purple, and orange). The colored circles on the right of each Escovopsis species name indicate the ant genera to which each fungal species is associated: Atta (green), Acromyrmex (blue), Apterostigma (red), Mycetomollerius (orange), and Paratrachymyrmex (brown).

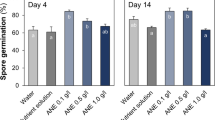

Furthermore, physiological data indicate that growth rate, conidiophore size, number of vesicles per conidiophore, conidia production, and conidia viability of Escovopsis have gradually increased as the genus has diversified (Figs. 3B, 4; see Supplementary Fig. 1 for morphological concepts). Species that form cylindrical vesicles can grow faster than those that form globose vesicles (Fig. 3A). Species that have the thinnest and most elongated cylindrical vesicles exhibit dramatically increased conidia production and viability (E. weberi, E. peniculiformis—Fig. 4) compared to species in the least derived clades (Fig. 4) and especially compared to those with globose vesicles (E. rosisimilis, E. lentecrescens, E. maculosa, E. aspergilloides, E. multiformis, E. clavata—Fig. 3A).

A–C colony growth area on PDA, MEA, and CMD media after four days at 25 °C. D Colony conidia production on PDA medium after four days at 25 °C. E Conidia viability on PDA medium after seven days at 25 °C. F Conidiophore length. G Number of vesicles formed per conidiophore. Measurements of growth area, conidia production, and viability of each Escovopsis species were obtained using 10 different plates (10 replicates). Conidiophore length and the number of vesicles formed per conidiophore were obtained analysing 10 different structures (conidiophores) per each species (Supplementary Data 3). Boxplots for each species are distinguished by different colors. Triangles represent the mean growth ratio, vertical lines the mid-point of the data, and short and long whiskers the lowest and the highest values, respectively (without considering outliers). Boxes marked with the same letter indicate species for which the mean growth rates did not differ significantly according to the Duncan’s Multiple Range Test.

Discussion

We provide insights into the evolutionary history, geographic distribution and adaptations of the fungal genus Escovopsis. Our results indicate that the origin of Escovopsis in the family Hypocreaceae corresponds in time with the origin of the fungus-growing ants, which is consistent with recent studies using genomes9,31,32,37. However, our results demonstrate that unlike what was previously assumed, Escovopsis did not evolve with the entire attina subtribe, but only with the most derived ("higher") ant clades and members of the most basally diverging ("lower") ant genus Apterostigma, over the past 38 My (Figs. 1A, 2). Furthermore, we show that Escovopsis is widely distributed across Central and South America (Fig. 1B), suggesting that, after its origin, this group of fungi dispersed in the same manner as the ants. In addition, our findings indicate that, since its first association with fungus-growing ant colonies, Escovopsis has experienced several morphological and physiological changes. We hypothesize that these changes are adaptations to overcome the defenses of the ant-colony environment and to maximally utilize the fungus gardens as habitats and as a food source.

While Escovopsis has been associated with the “lower” attine genus Apterostigma and the higher attine genera Atta, Acromyrmex, Mycetomoellerius, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex for the last 38 My, the evolutionary history of this genus during the first 18 My after its origin still remains uncertain. Based on our results, the most plausible scenario is that, after its origin and before becoming a symbiont of the ants with which Escovopsis is currently associated, the ancestor of Escovopsis was probably associated with early-diverging clades of attines. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that: (i) the origin of the most basally diverging and oldest Escovopsis clade (Fig. 2, node 13) and Apterostigma, correspond in time and both fungi and ants exhibit almost strict co-cladogenesis (Fig. 1A), and (ii) the sister clades of Escovopsis (i.e., Luteomyces and Sympodiorosea) are only associated with lower attines. The discovery of some living or fossil species of Escovopsis associated with older ant clades would help to confirm this hypothesis.

Because Escovopsis was traditionally considered as the only, specialized and highly virulent mycoparasite of the mutualistic fungus of fungus-growing ants, the ecological role of this genus has long been of interest to scientists that study the attine ant-fungal mutualism22,25,34,54,55,56,57,58,59. Surprisingly, however, to date: (i) very little is known about the biology and ecology, especially on the mycoparasitic mechanisms, of these group fungi; (ii) while E. weberi was reported as virulent parasites of the attine fungus garden21, recent studies have suggested that across the Escovopsis phylogeny, most of this fungal species are opportunists, with low virulence regulated by the ant cultivar18,19; (iii) the negative impacts towards fungal cultivars are observed only in in vitro or in ant colonies in laboratory conditions21,23,25,26,30,54,56,60, but not in in vitro assays that mimic the ants’ natural system complexity19 nor in field colonies (personal observations). Our results reveled that although different ants share some Escovopsis species, the most derived clades of Escovopsis are mostly associated with Atta and Acromyrmex, the most basally diverging clade of Escovopsis is mostly associated with Apterostigma, and the transitional Escovopsis clades are mostly associated with Mycetomoellerius, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex (Fig. 1A). Given this fragmented information, it is difficult to know whether these associations are related to the ecological role of this group of fungi, to the behavior of the ants, or to the type of mutualistic fungus they cultivate. Future studies combining large-scale collections in which both Escovopsis and cultivars are isolated from the same ant colony, with laboratory assays to search for mycoparasitic characteristics and mechanisms, are necessary to fill these gaps.

Considering that species in the Hypocreaceae family (the same family to which Escovopsis belongs), have a wide variety of lifestyles, i.e., mycoparasites, endophytes, and saprotrophs61,62,63; and, that phylogenetically closely related species can exhibit similar traits or behaviors64, it is plausible that species within Escovopsis can also vary in relation to their lifestyle as observed in their sister clades Trichoderma and Hypomyces62,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72. Furthermore, it is also interesting to notice that the closest sister clades of Escovopsis, i.e., Sympodiorosea, Luteomyces, Escovopsioides, and two undescribed phylogenetic clades, are only found in association with the earliest derived ant clades (with exception of Escovopsioides). The genetic, ecological, and morphological diversity of these fungal groups has been little studied to date. Even so, studies have shown a certain degree of attraction to the ant cultivars in Sympodiorosea strains25,34,54, no attraction in Luteomyces73, a certain degree of antagonism in Escovopsioides74,75,76, and no data is available to the two undescribed clades. Our knowledge on the ecology and biology of these attine symbionts are merely few pixels from a large photo. In addition, the knowledge on the geographic distribution of Sympodiorosea, Luteomyces, Escovopsioides, and the two undescribed phylogenetic clades is still fragmented. Future studies unraveling the diversity and ecology of these fungal groups will be of great importance to understand the evolutionary history of the Hypocreaceae fungi associated with attine colonies.

Finally, while further research is needed to better understand the evolution of the lifestyles of these fungi, morphological and physiological evidence are consistent with the hypothesis that Escovopsis has undergone several adaptations since its origin. Our results demonstrate that as Escovopsis diversified, swollen conidiophore cells were lost (Fig.3A c) and the shape of the vesicles changed (Fig.3A, a, b). In addition, conidiophore length (Fig.3A, a, b), the number of the vesicles per conidiophore (Fig.4G), conidia production, and conidia viability gradually increased (Figs.3B, 4D, E). By avoiding swollen cells, these fungi are able to produce more branches per conidiophore, which in turn increases the number of vesicles per conidiophore (Fig. 4G). Because phialides (cells responsible for producing conidia) are formed on vesicles (Supplementary Fig. 1), the number of these structures is directly related to the number of conidia produced. Thus, the larger the vesicles, the greater the number of phialides and the greater the amount of conidia produced. Furthermore, physiological tests showed that the growth velocity of the genus also increased as it diversified (Figs.3B, 4A–C). The combination of these trait changes suggests that Escovopsis is evolving in such a way as to increase its asexual reproductive efficiency. Parasites develop specialized organs, chemical compounds, and other mechanisms to adhere to, penetrate, and avoid host immune systems77,78,79, yet the development of these mechanisms is still poorly understood in Escovopsis58. On the other hand, environmental pressures can influence or shape the morphology, physiology, and lifestyles of fungi80,81. Therefore, considering the complexity of the attine ants’ system, we hypothesize that these traits may have evolved specifically to facilitate persistence in attine gardens, and particularly in the presence of the higher attine ants, which employ suppression strategies such as mechanically weeding out Escovopsis in laboratory infections51,82 and employing antibiotic-producing bacteria that can suppress Escovopsis growth83,84.

Methods

Isolates and isolation procedure

This study includes a total of 309 isolates (Supplementary Data 1) from over 400 sampled ant colonies representing 11 out of 20 attine genera (Atta, Acromyrmex, Apterostigma, Cyphomyrmex, Mycetarotes, Mycetomoellerius, Mycetophylax, Mycetosoritis, Myrmicocrypta, Paratrachymyrmex, and Sericomyrmex). Ant colonies were collected in six different countries (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and Trinidad and Tobago) spanning different biomes. A total of 64 out of the 309 strains were isolated in this study, and the remaining were obtained from the Laboratory of Fungal Ecology and Systematics (LESF–São Paulo State University, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil) and a collection at Emory University, Atlanta, USA.

For Escovopsis isolation, we followed methods described by Montoya et al. (2019)38. Briefly, seven fungus-garden fragments (varying 0.5–1 mm3) were inoculated on plates containing potato dextrose agar (PDA, Neogen® Culture Media, Lansing, MI, USA) supplemented with 150 µg mL–1 chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Three plates were inoculated per each ant colony. Once Escovopsis was isolated, axenic cultures were prepared and stored in sterile distilled water (Castellani 1963) at 8–10 °C, in 10% glycerol at –80 °C (cryopreservation), and freeze-drying. All strains were deposited at LESF and at the Microbial Resources Center (CRM-UNESP).

DNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using a modified CTAB method85. Briefly, fungal aerial mycelia, grown for seven days at 25 °C on PDA, were crushed with the aid of glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in lysis solution and incubated at 65 °C for 30 min. The organic phase was separated using a solution of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Then, the material was centrifuged (10,000 g for 10 minutes), and the supernatant with the genomic DNA was collected. This extract was precipitated with 3M sodium acetate and isopropanol and purified with two successive washes of 70% ethanol. The DNA was suspended in 30 µL of Tris-EDTA solution and stored at -20 °C.

Five molecular markers were amplified for all Escovopsis strains isolated in this study: the internal transcribed spacer (ITS: ITS4—5’TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC3’, ITS5—5’GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG3’)86,87, the large subunit ribosomal RNA (LSU: CLA-F—5’GCATATCAATAAGCGGAGGA3’, CLA-R—5’GACTCCTTGGTCCGTGTTTCA3’)22, the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1: EF6–20F—5’AAGAACATGATCACTGGTACCT3’, EF6–1000R - 5’CGCATGTCRCGGACGGC3’)88, the RNA polymerase II protein-coding gene rpb1 (rpb1: RPB1-Af, RPB1Ac—5’GARTGYCCDGGDCAYTTYGG3’, RPB1-Cr—5’CCNGCDATNTCRTTRTCCATRTA3’)89, and the RNA polymerase II protein-coding gene rpb2 (rpb2: fRPB2-5F (F)—5’GA(T/C)GA(T/C)(A/C)G(A/T)GATCA(T/C)TT(T/C)GG-3’, fRPB2-7cR (R)—5’CCCAT(A/G)GCTTG(T/C)TT(A/G)CCCAT3’89, source of all oligos: Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, USA). For the strains obtained from the Gerardo Laboratory and the LESF collections, we used previously published ITS, LSU and tef1 sequences, when available, and generated the missing sequences, when possible. In the end, we gathered a total of 309 sequences of ITS, 307 sequences of LSU, 298 sequences of rpb1, 296 sequences of rpb2, and 305 sequences of tef1.

PCR reactions for ITS, LSU and tef1 were performed in a final volume of 25 µL [4 µL of dNTPs (1.25 mM each); 5 µL of 5X buffer; 1 µL of BSA (1 mg mL–1); 2 µL of MgCl2 (25 mM); 1 µL of each primer (10 µM); 0.5 µL of Taq polymerase (5 U µL–1), 2 µL of diluted genomic DNA (1:100) and 8.5 µL of sterile ultrapure water]; and in the case of rpb1 and rpb2, we added 1.5 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and adjusted the volume of sterile ultrapure water to 7.0 µL. PCR conditions for ITS and LSU were: 96 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 2 min22,86,87. For tef1, the conditions were: 96 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles at 96 °C for 30 s, 61 °C for 45 s and a final extension step at 72 °C for 1 min55. For rpb1 and rpb2, a touchdown PCR was used: 96 °C for 5 min; 15 cycles of 94 °C for 30s, 65 °C for 1.5 min for rpb1 and for 1 min for rpb2 (the annealing temperature gradually decreased 1 °C per cycle), and 72 °C for 1.5 min for rpb1 and for 1 min for rpb2; and then 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30s, 50 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min36.

Final amplicons were purified with the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequences (forward and reverse) were generated on an ABI3500 (Life Technologies), and the consensus sequences were assembled in BioEdit v. 7.1.390 and Geneious91. All sequences are deposited in GenBank (Supplementary Data 1 for accessions).

Phylogenetic analysis

We reconstructed the Escovopsis phylogeny to evaluate putative Escovopsis – ant co-cladogenesis and geographic distribution of the genus. A concatenated multilocus analysis was carried out for this purpose. The final dataset contained 314 sequences of 3709 bp in length [314 ITS (587 bp in length), 312 LSU (591 bp), 310 tef1 (758 bp), 305 rpb1 (607 bp), and 301 rpb2 (1045 bp)]. Sympodiorosea kreiselii CBS 139320ET (Ex-type strain) was used as the outgroup.

Each locus was aligned separately using the BLOSUM62 scoring matrix with 1,53 gap opening penalty and 0.0 of offset value in MAFFT92, and the nucleotide substitution model of each alignment was calculated in jModeltest 293. Then, all files were concatenated using Winclada v.1.00.0894 and the phylogenetic tree was inferred using a Bayesian approach in MrBayes v. 3.2.195. The analysis was carried out with twelve separate runs (each consisting of eleven hot chains and one cold chain) in CIPRES (http://www.phylo.org/). We used GTR model for all genes separately. Five million generations of the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) were necessary to reach convergence (standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01). The first 25% of the generations of MCMC sampling were discarded as burn-in to generate a consensus tree, and the final tree was edited in FigTree v.1.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and Adobe Illustrator CC v.17.1.

Divergence time analysis

To estimate the origin of Escovopsis, we reconstructed a phylogenetic tree combining the sequences of representative strains of each clade in Escovopsis (n=35), Escovopsioides (n=10), Luteomyces (n=10), and Sympodiorosea (n=12) with the sequences of the Hypocreales provided by Sung et al. (2008) (Supplementary Data 2). Thus, 172 sequences of LSU (594 bp), tef1 (776 bp), rpb1 (820 bp), and rpb2 (998 bp) were aligned separately using the BLOSUM62 scoring matrix with 1,53 gap opening penalty and 0.0 of offset value in MAFFT92 and concatenated in Winclada v.1.00.0894. The final phylogenetic tree was inferred under a Bayesian approach95 using the GTR model (calculated in jModeltest 2)93. Then, we carried out a divergence time analysis based on the calibration of the Hypocreales tree reconstructed by Sung et al. (2008)96. To do so, we uploaded the alignments of LSU, tef1, rpb1, and rpb2 separately into BEAUti91 to create the xml file with the partitions [LSU (594 bp), tef1 (776 bp), rpb1 (820 bp), and rpb2 (998 bp)], the clock model, and the priors. We used the nodes of the previous inferred tree as priors of monophyletic clades and the calibration of the tree was based on seven nodes previously calibrated by Sung et al. (2008)96 [node 1 (193 Mya), node 2 (176 Mya), node 3 (178 Mya), node 4 (170 Mya), node 5 (173 Mya), node 6 (165Mya) and node 7 (158 Mya)]. The analysis was performed in BEAST 2.597. We used the uncorrelated relaxed clock site model98 with a JC69 substitution model to accommodate the rate heterogeneity across the branches of the tree. The clock model was the relaxed clock log normal with the priors specifying a Birth Death model process, with the origin height of 193 (158, 232) Mya. We conducted four independent analyses with an MCMC length of 50,000,000 generations each, with sampling of every 100th generation and removing 300,000 of generations as burn in. Finally, 750,000 trees where summarised using TreeAnotator 2.6 in BEAST91, and the final tree was manually edited using FigTree v.1.4 and Adobe Illustrator.

Trait evolution analysis

The vesicle shape is one of the most diagnostic characters throughout Escovopsis phylogeny. These structures are ecologically important because they are directly related to the formation of phialides (conidiogenous cells), which in turn are responsible of the conidia formation (Supplementary Fig. S1). On the other hand, physiological characters, i.e., the growth rate, amount of conidia produced, and conidia viability, are directly related with the evolutionary success of these fungi99. Consequently, the evaluation of those morphological and physiological characters in Escovopsis were of great importance for understanding the evolutionary adaptations of this genus. In this sense, we selected the type strains representing the main clades throughout the Escovopsis phylogeny (n=14) to evaluate morphological (vesicle shape, conidiophore shape and size, and number of vesicles per conidiophore), and physiological (growth rate, amount of conidia produced, and conidia viability) variations of the genus.

To assess microscopic structures such as vesicles and conidiophores (Supplementary Fig. S1), we carried out slide culture preparations. Each type strains were inoculated on a 0.5 mm3 block piece of PDA medium, covered with a coverslip and incubated at 25 °C for five days in darkness (Montoya et al. 2021). Then, the coverslips were removed and placed on slides with a drop of lactophenol. The slides were examined under a light microscope (DM750, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and the conidiophores and vesicles were photographed using LAS EZ v.4.0 (Leica Application Suite). Ten photos were randomly chosen to access the length and number of vesicles per conidiophore (Supplementary Data 3).

To evaluate growth rate variation across the Escovopsis phylogeny, we followed the growth method described in Montoya et al.35,36. Briefly, 200 μL of a suspension of 106 conidia per 1 μL were surface spread on Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) containing water-agar (WA) and incubated for seven days at 25 °C in darkness. Then, we obtained fragments of 0.5 cm diameter × 5 mm height of WA with mycelium and inoculated at the center of Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) PDA. This experiment was performed using ten replicates for each media and for each strain. The plates were incubated at 25 °C for four days in darkness and then we measured area of growth (Supplementary Data 3) using ImageJ2 v.2.3.0 in Fiji100. Statistical analysis was performed in R Studio using standard one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test; differences were considered significant when P≤ 0.05.

To evaluate conidia production, fragments of 0.5 cm diameter× 5 mm height of WA with mycelium (prepared as above) were inoculated at the center of Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) containing PDA, and incubated at 25 °C for seven days in darkness. The experiment was performed using ten replicates for each strain. After seven days, mycelial mass and conidia were removed from colonies using 5–40 ml of 0.5% Tween 80 (the volume depended on the size of the colony). Then, conidia were separated from hyphal fragments in the suspension using Cell strainer filters of 40 µm (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the number of conidia in the suspension was calculated using a Neubauer chamber (Supplementary Data 3). Statistical analysis of the data obtained was performed in R Studio using standard one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test; differences were considered significant when P≤ 0.05.

To evaluate the viability of the conidia, we first adjusted the inoculum to a concentration in which the germinated conidia could be counted both in slow and fast-growing species. The inoculum of 200 µL of 104 conidia mL–1 was the most ideal for this purpose. Thus, to obtain the inoculum, the strains were cultivated on PDA, at 25 °C, for seven days, in the dark. Then, 200 µL of 104 conidia mL–1 was inoculated on 10 plates containing PDA, for each strain, and incubated at 25 °C, for four days, in the dark. Germination of the conidia was marked daily on the base of the plate to avoid overlapping of germinated conidia and loss of count by the mycelium growth of conidia that germinated first. The germinated conidia marked on the plates were counted on the last day of the experiment (Supplementary Data 3). We then calculated the germination percentage (conidia viability) and performed statistical analysis in R Studio using standard one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple range test; differences were considered significant when P≤ 0.05.

Ancestral state reconstruction of vesicles

Microscopic images of each strain were used to randomly extract vesicles (30 vesicles per strain, 450 vesicles in total). The vesicle images were converted into black silhouettes, placed on white backgrounds and saved as jpeg files using GIMP 2.8101. The outlines were then imported into R as a list of coordinates and four landmarks placed on the widest points of each vesicle (top, bottom, and sides), to avoid unexpected twisting of specimens and improve their alignment. Then we extracted the vesicles shape information using the morphometric technique of Elliptic Fourier analysis (eFa) as implemented in the library Momocs v1.3.2102 for the R statistical environment103. eFa is widely used by morphologists to quantify variation in shapes from outline data and has been used with all kinds of structures, including leaves104, fossil bivalves105, and fish106. The coefficients were summarized using principal components analysis (PCA), and morphospaces were drawn to visualize and interpret the results. We estimated with Momocs that 32 harmonics were more than enough to achieve 99% of harmonic power102. Finally, we conducted an ancestral state reconstruction of this structure as a continuous variable, to understand the evolution of vesicle shape. We exported the first principal component from the eFa, calculated a mean value for each strain, matched the strains to the chronogram and used the function contMap of the library phytools v0.7-70107 to reconstruct overall vesicle shape. This approach takes as input the phylogenetic tree and data for each tip and estimates the ancestral states at internal nodes using Maximum Likelihood under a standard Brownian motion model and then interpolates the states along each edge108,109.

Ancestral state reconstruction of physiological traits

We estimated the ancestral state of multivariate traits using the l1ou R package110 for the four traits (vesicle shape, growth, conidia production, conidia viability) allowing for shifts in trait values as in the univariate case. We assume that the traits arose from independent OU processes, each with its own adaptation rate (α) variance (σ2), but with shifts that happen on the same shared set of branches. We use phylogenetic BIC criterion (pBIC) for model selection on the number of shifts, and we use a random root with stationary distribution.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Sequences generated in this study are deposited at NCBI-GenBank under accessions ITS (PV563201—PV563367), LSU (PV566955—PV567125), tef1 (PV567889—PV568051), rpb1 (PV588284—PV588290, PV588291—PV588292, PV588293—PV588295, PV588296—PV588303, PV588304—PV588311, PV588312—PV588327, PV588328—PV588329, PV588330—PV588450), rpb2 (PV588451—PV588611).

References

Poulin, R. Evolution of parasite life history traits: myths and reality. Parasitol. Today 11, 342–345 (1995).

Thomas, F. et al. Manipulation of host behaviour by parasites: ecosystem engineering in the intertidal zone. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 265, 1091–1096 (1998).

Thomas, F. et al. Parasites and ecosystem engineering: what roles could they play. Oikos 84, 167 (1999).

Feis, M. E. et al. Biological invasions and host – parasite coevolution: different coevolutionary trajectories along separate parasite invasion fronts. Zoology 119, 366–374 (2016).

Papkou, A. et al. Host – parasite coevolution: why changing population size matters. Zoology 119, 330–338 (2016).

Filipiak, A. et al. Coevolution of host-parasite associations and methods for studying their cophylogeny. Invertebr. Survival J. 13, 56–65 (2016).

Aleuy, O. A. & Kutz, S. Adaptations, life-history traits and ecological mechanisms of parasites to survive extremes and environmental unpredictability in the face of climate change. Int J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 12, 308–317 (2020).

Schultz, T. R. & Brady, S. G. Major evolutionary transitions in ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5435–5440 (2008).

Schultz, T. R. et al. The coevolution of fungus-ant agriculture. Science 386, 105–110 (2024).

Branstetter, M. G. et al. Dry habitats were crucibles of domestication in the evolution of agriculture in ants. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 284, 20170095 (2017).

Mueller, U. G. Symbiont recruitment versus ant-symbiont co-evolution in the attine ant-microbe symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15, 269–277 (2012).

Rodrigues, A. et al. Variability of non-mutualistic filamentous fungi associated with Atta sexdens rubropilosa nests. Folia Microbiol. 50, 421–425 (2005).

Rodrigues, A. Microfungal “weeds” in the leafcutter ant symbiosis. Microb. Ecol. 56, 604–614 (2008).

Rodrigues, A. et al. Ecology of microfungal communities in gardens of fungus-growing ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): A year-long survey of three species of attine ants in Central Texas. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 78, 244–255 (2011).

Barcoto, M. O. Fungus-growing insects host a distinctive microbiota apparently adapted to the fungiculture environment. Sci. Rep. 10, 12384 (2020).

Montoya, Q. V. et al. Unraveling Trichoderma species in the attine ant environment: description of three new taxa. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109, 633–651 (2016).

Elliot, S. L. et al. The fungus Escovopsis (Ascomycota: Hypocreales): a critical review of its biology and parasitism of attine ant colonies. Front. Fungal Biol. 5, 1486601 (2025).

Mendonça, D. M. F. Low Virulence of the fungi Escovopsis and Escovopsioides to a leaf-cutting ant-fungus symbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 12, 673445 (2021).

Jiménez-Gómez, I. et al. Host susceptibility modulates Escovopsis pathogenic potential in the fungiculture of higher attine ants. Front. Microbiol. 12, 673444 (2021).

Currie, C. R. et al. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature 398, 701–704 (1999).

Currie, C. R. Prevalence and impact of a virulent parasite on a tripartite mutualism. Oecologia 128, 99–106 (2001).

Currie, C. R. et al. Ancient tripartite coevolution in the attine ant-microbe symbiosis. Science 299, 386–388 (2003).

Reynolds, H. T. & Currie, C. R. Pathogenicity of Escovopsis weberi: the parasite of the attine ant-microbe symbiosis directly consumes the ant-cultivated fungus. Mycologia 96, 955–959 (2004).

Gerardo, N. M. et al. Exploiting a mutualism: parasite specialization on cultivars within the fungus-growing ant symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 271, 1791–1798 (2004).

Gerardo, N. M., Mueller, U. G. & Currie, C. R. Complex host-pathogen coevolution in the Apterostigma fungus-growing ant-microbe symbiosis. BMC Evolut. Biol. 6, 88 (2006).

Taerum, S. J., Cafaro, M. J. & Currie, C. R. Presence of multiparasite infections within individual colonies of leaf-cutter Ants. Environ. Entomol. 39, 105–113 (2010).

Boomsma, J. J., Schmid-Hempel, P. & Hughes, W. O. H. Life histories and parasite pressure across the major groups of social insects. Insect Evolut. Ecol. 211, 139–175 (2005).

Schmid-Hempel, P. Parasitism and life history in social insects. Life Cycles in Social Insects: Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution. 37–48 (2006).

Fréderic, T. &François, R. Ecology and evolution of parasitism first edit. F. R. Fréderic Thomas, Jean-François Guenan, ed. (Oxford University Press). (2009).

Currie, C. R., Mueller, U. G. & Malloch, D. The agricultural pathology of ant fungus gardens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 7998–8002 (1999).

De Man, T. J. B. et al. Small genome of the fungus Escovopsis weberi, a specialized disease agent of ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3567–3572 (2016).

Gotting, K. et al. Genomic diversification of the specialized parasite of the fungus-growing ant symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2213096119 (2022).

Cafaro, M. J. et al. Specificity in the symbiotic association between fungus-growing ants and protective Pseudonocardia bacteria. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 278, 1814–1822 (2011).

Birnbaum, S. S. L. & Gerardo, N. M. Patterns of specificity of the pathogen Escovopsis across the fungus-growing ant symbiosis. Am. Nat 188, 52–65 (2016).

Montoya, Q. V. Fungi inhabiting attine ant colonies: reassessment of the genus Escovopsis and description of Luteomyces and Sympodiorosea gens. nov. IMA Fungus 12, 23 (2021).

Montoya, Q. V., Martiarena, M. J. S. & Rodrigues, A. Taxonomy and systematics of the fungus-growing ant associate Escovopsis (Hypocreaceae). Stud. Mycol. 106, 349–397 (2023).

Berasategui, A. et al. Genomic insights into the evolution of secondary metabolism of Escovopsis and its allies, specialized fungal symbionts of fungus-farming ants. mSystems 9, 7 (2024).

Montoya, Q. V. et al. More pieces to a huge puzzle: two new Escovopsis species from fungus gardens of attine ants. MycoKeys 46, 97–118 (2019).

Muchovej, J. J. & Della Lucia, T. M. C. Escovopsis. A new genus from leaf-cutting ants nests to replace Phailocladus nomem invalidum. Mycotaxon 37, 191–195 (1990).

Marfetán, J. A. et al. Five new Escovopsis species from Argentina. Mycotaxon 133, 569–589 (2018).

Augustin, J. O. Yet more “weeds” in the garden: Fungal novelties from nests of leaf-cutting ants. PLoS One 8, e82265 (2013).

Seifert, K. A. et al. Escovopsis aspergilloides, a rediscovered hyphomycete from leaf-cutting ant nests. Mycologia 87, 407–413 (1995).

Camus, D. et al. The art of parasite survival. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 28, 399–413 (1995).

Libersat, F., Kaiser, M. & Emanuel, S. Mind control: how parasites manipulate cognitive functions in their insect hosts. Front. Psychol. 9, 572 (2018).

Schmid-Hempel, P. Immune defence, parasite evasion strategies and their relevance for “macroscopic phenomena” such as virulence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 364, 85–98 (2009).

Hughes, D. P., Brodeur, J., and Thomas, F. (2015). Host manipulation by parasites First edition. (Oxford University Press).

Gandon, S., Agnew, P. & Michalakis, Y. Coevolution between parasite virulence and host life-history traits. Am. Soc. Naturalis 160, 374–388 (2002).

Arriero, E. & Møller, A. Host ecology and life-history traits associated with blood parasite species richness in birds. J. Evolut. Biol. 21, 1504–1513 (2008).

Martinsen, E. S., Perkins, S. L. & Schall, J. J. A three-genome phylogeny of malaria parasites (Plasmodium and closely related genera): evolution of life-history traits and host switches. Mol. Phylogenetics Evolut.47, 261–273 (2008).

Andersen, S. B. et al. Disease dynamics in a specialized parasite of ant societies. PLoS One 7, e36352 (2012).

Goes, A. C. et al. How do leaf-cutting ants recognize antagonistic microbes in their fungal crops. Front. Ecol. Evolut. 8, 1–12 (2020).

Hanisch, P. E., Sosa-Calvo, J. & Schultz, T. R. The last piece of the puzzle? Phylogenetic position and natural history of the monotypic fungus-farming ant genus Paramycetophylax (Formicidae: Attini). Insect Syst. Diversity 6, 11 (2022).

Barrera, C. A. et al. Phylogenomic reconstruction reveals new insights into the evolution and biogeography of Atta leaf-cutting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Syst. Entomol. 47, 13–35 (2022).

Gerardo, N. M. et al. Ancient host-pathogen associations maintained by specificity of chemotaxis and antibiosis. PLoS Biol. 4, 1358–1363 (2006).

Taerum, S. J. et al. Low host-pathogen specificity in the leaf-cutting ant-microbe symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 274, 1971–1978 (2007).

Folgarait, P. et al. Preliminary in vitro insights into the use of natural fungal pathogens of leaf-cutting ants as biocontrol agents. Curr. Microbiol. 63, 250–258 (2011).

ElizondoWallace, D. E., Vargas-Asensio, J. G. & Pinto-Tomás, A. A. Correlation between virulence and genetic structure of Escovopsis strains from leaf-cutting ant colonies in Costa Rica. Microbiology 160, 1727–1736 (2014).

Marfetán, J. A., Romero, A. I. & Folgarait, P. J. Pathogenic interaction between Escovopsis weberi and Leucoagaricus sp.: mechanisms involved and virulence levels. Fungal Ecol. 17, 52–61 (2015).

Heine, D. et al. Chemical warfare between leafcutter ant symbionts and a co-evolved pathogen. Nat. Commun. 9, 2208 (2018).

Little, A. E. F. et al. Defending against parasites: fungus-growing ants combine specialized behaviours and microbial symbionts to protect their fungus gardens. Biol. Lett. 2, 12–16 (2006).

Põldmaa, K. Tropical species of Cladobotryum and Hypomyces producing red pigments. Stud. Mycol. 68, 1–34 (2011).

Bailey, B. A. & Melnick, R. L. (2013) The endophytic Trichoderma. In: Mukherjee, P. K.et al. (eds) Trichoderma: Biology and Applications 152–172.

Chaverri, P. et al. Systematics of the Trichoderma harzianum species complex and the re-identification of commercial biocontrol strains. Mycologia 107, 558–590 (2015).

Mitchell, E. et al. Behavioural traits propagate across generations via segregated iterative-somatic and gametic epigenetic mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 7, 11492 (2016).

Põldmaa, K. Generic delimitation of the fungicolous Hypocreaceae. Stud. Mycol. 45, 83–94 (2000).

Druzhinina, I. & Kubicek, C. P. Species concepts and biodiversity in Trichoderma and Hypocrea: From aggregate species to species clusters. J. Zhejiang Univ. -Sci. B 6, 100–112 (2005).

Druzhinina, I. S. et al. Trichoderma: the genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 749–759 (2011).

Chaverri, P. & Samuels, G. J. Evolution of habitat preference and nutrition mode in a cosmopolitan fungal genus with evidence of interkingdom host jumps and major shifts in ecology. Evolution 67, 2823–2837 (2013).

Mukherjee, M. et al. Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions: advances in genetics of biological control. Indian J. Microbiol. 52, 522–529 (2012).

Jaklitsch, W. M. European species of Hypocrea Part I. The green-spored species. Stud. Mycol. 63, 1–91 (2009).

Jaklitsch, W. M. & Samuels, G. J. Reconsideration of Protocrea (Hypocreales, Hypocreaceae). Mycologia 100, 962–984 (2011).

Guzmán-Guzmán, P. et al. Trichoderma species: Versatile plant symbionts. Phytopathology 109, 6–16 (2019).

Bizarria, R., Nagamoto, N. S. & Rodrigues, A. Lack of fungal cultivar fidelity and low virulence of Escovopsis trichodermoides. Fungal Ecol. 45, 100944 (2020).

Varanda-Haifig, S. S. et al. Nature of the interactions between hypocrealean fungi and the mutualistic fungus of leaf-cutter ants. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 110, 593–605 (2017).

Osti, J. F. & Rodrigues, A. Escovopsioides as a fungal antagonist of the fungus cultivated by leafcutter ants. BMC Microbiol. 18, 130 (2018).

Pietrobon, T. C. et al. Escovopsioides nivea is a non-specific antagonistic symbiont of ant-fungal crops. Fungal Ecol. 56, 101140 (2022).

Szabo, L. J. & Bushnell, W. R. Hidden robbers: the role of fungal haustoria in parasitism of plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 7654–7655 (2001).

Howell, C. R. Mechanisms employed by Trichoderma species in the biological control of plant diseases: The history and evolution of current concepts. Plant Dis. 87, 4–10 (2003).

Shimizu, K. & Aoki, K. Development of parasitic organs of a stem holoparasitic plant in genus Cuscuta. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1–11 (2019).

Brown, A. J. P. et al. Stress adaptation. Microbiol Spectr. 5, 1–23 (2017).

Lin, X. et al. Fungal morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 5, 1–25 (2015).

Mangone, D. M. & Currie, C. R. Garden substrate preparation behaviours in fungus-growing ants. Can. J. Entomol. 139, 841–849 (2007).

Fernández-Marín, H. et al. Functional role of phenylacetic acid from metapleural gland secretions in controlling fungal pathogens in evolutionarily derived leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 282, 20150212 (2015).

Fernández-Marín, H. et al. Active use of the metapleural glands by ants in controlling fungal infection. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 273, 1689–1695 (2006).

Möller, E. M. et al. A simple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 6115–6116 (1992).

White, T. J. et al. (1990) Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In: Innis, M. A. et al. (eds) PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, Academic Press, New York, 315-322.

Schoch, C. L. et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 6241–6246 (2012).

Meirelles, L. A. et al. New light on the systematics of fungi associated with attine ant gardens and the description of Escovopsis kreiselii sp. nov. PLoS One 10, 1–14 (2015).

Liu, Y. J., Whelen, S. & Hall, B. D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evolut.16, 1799–1808 (1999).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649 (2012).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evolut.30, 772–780 (2013).

Darriba, D. et al. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772–772 (2012).

Nixon, K. C. WinClada ver. 1.0000. Ithaca, New York, USA (2002).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Sung, G. H., Poinar, G. O. & Spatafora, J. W. The oldest fossil evidence of animal parasitism by fungi supports a Cretaceous diversification of fungal-arthropod symbioses. Mol. Phyl. Evol. 49, 495–502 (2008).

Drummond, A. J. & Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolut. Biol. 7, 1–8 (2007).

Drummond, A. J. et al. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 4, 699–710 (2006).

Nagy, L. G. et al. Six Key Traits of Fungi: their evolutionary origins and genetic bases. Microbiol. Spectr. 5, 4 (2017).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). Preprint.

Solomon, R. W. Free and open source software for the manipulation of digital images. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 192, 330–334 (2009).

Bonhomme, V. et al. Momocs: outline analysis using R. J. Stat. Softw. 56, 1–24 (2014).

R Core, T. (2004). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

Kincaid, D. T. & Schneider, R. B. Quantification of leaf shape with a microcomputer and Fourier transform. Can. J. Bot. 61, 2333–2342 (1983).

Crampton, J. S. Elliptic Fourier shape analysis of fossil bivalves: some practical considerations. Lethaia 28, 179–186 (1995).

Caillon, F. et al. A morphometric dive into fish diversity. Ecosphere 9, e02220 (2018).

Revell, L. J. phytools: An R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things. Methods Ecol. Evolut.3, 217–223 (2012).

Felsenstein, J. Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am. Naturalist 125, 1–15 (1985).

Revell, L. J. Two new graphical methods for mapping trait evolution on phylogenies. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 754–759 (2013).

Khabbazian, M. et al. Fast and accurate detection of evolutionary shifts in Ornstein–Uhlenbeck models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 811–824 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Laboratory of Fungal Ecology and Systematics (LESF—São Paulo State University, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil) and the Gerardo Laboratory (Emory University, Atlanta, USA) research teams, especially Aileen Berasategui Lopez and Caitlin Conn, for valuable comments and discussions on this study. We thank Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) for issuing collecting permits (# 31534, 46555, 74585, and 97566-1). This study was conducted under the permit issued by Conselho de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético (CGen) for the access of Brazilian genetic heritage (SISGen # A6041D0, AF813CD, AA39A6D, and A2EE1CD). A.R. and Q.V.M. received funding from the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP, grants 2014/24298-1, 2017/12689-4, and 2019/03746-0; and scholarships 2016/04955-3, 2018/07931-3, and 2021/04706-1, respectively. AR also received funding from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development—CNPq, grant 305269/2018-6. NMG received funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF DEB-1754595 and DEB-1927161). C.S.L. received funding from the National Science Foundation (DEB-2144367). T.R.S. and J.S.C. received funding from the National Science Foundation (DEB-1927161).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.V.M., M.J.S.M., N.M.G., and A.R. designed the study. Q.V.M. and M.J.S.M. carried out the laboratory assays and statistical analysis. Q.V.M. carried out the phylogenetic and divergence time analyses. Q.V.M., C.S.L., and R.K. carried out the morphometric and ancestral state reconstruction analyses. T.R.S. and J.S.C. carried out ants’ identification and phylogenetic analysis. A.R. acquired funding and supervised the study. Q.V.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, proofread, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Veronika Mayer, Priscila Hanisch and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Michele Repetto. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Montoya, Q.V., Gerardo, N.M., Martiarena, M.J.S. et al. Digging into the evolutionary history of the fungus-growing-ant symbiont, Escovopsis (Hypocreaceae). Commun Biol 8, 1340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08654-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08654-z