Abstract

Sleep is a complex physiological state characterized by synchronized cortical and cardiac oscillations, which reflect dynamic communication and interaction between the central (CNS) and autonomic (ANS) nervous systems, crucial for maintaining homeostasis and overall health. However, the dynamic interplay between CNS and ANS rhythmicities in sleep remains unclear. Here, we present a variational phase-amplitude coupling framework that associates frequency modulations of the electroencephalogram and cardiac R-peak intervals across sleep dynamics. We validate the robustness of our method on spurious couplings by nonlinear or nonstationary simulations. Moreover, delta-range slow cortical oscillations exhibit robust coupling with both the low- (HRV-LF) and high-frequency (HRV-HF) constituents of RR-interval heart-rate variability, thereby constituting a cardinal electrophysiological signature of ANS-CNS modulation. Furthermore, we highlight the significance of the “decoupling phenomenon” in a transitional period from wake to sleep for sleep preparation, and discover stronger couplings between the HRV-LF component and EEG-δ wave, and weaker couplings between the HRV-HF component and EEG-δ activity for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients compared to healthy individuals, and finally uncover the key patterns of brain-heart interaction in both healthy cohorts and OSA patients during sleep.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neural communication between the brain and peripheral subsystems contributes to coordinating information in distributed regions of the body, facilitating to maintenance of homeostasis and adjusting physiological adaptation to external inputs1,2,3. In recent years, considerable efforts have been devoted to exploring the reciprocal brain-body interplay in various physiological conditions, including emotion perception4,5,6, sleep regulation7, and cognition8. Of particular interest is the emerging focus on brain-heart interaction (BHI), which involves estimating the information exchange between heart rate variability (HRV) time series and electroencephalography (EEG)9,10, or investigating the rapid neural response to individual heartbeats directly, commonly referred to as heartbeat evoked potentials (HEPs)11. Evidence suggests that the dynamic interplay between the central nervous system (CNS) and autonomic nervous system (ANS), demonstrated by functional BHI, plays a vital role during state transitions12, but research on their communication formation and extent of mutual-interplay influences over physiological dynamics remains in its nascent stage.

As a fundamental and intricate physiological phenomenon, sleep is distinguished by synchronized cortical and cardiac rhythmicities, highlighting the interconnected relationship between CNS and ANS13. Evidence from studies in humans and animal models suggests that the ANS activities can influence the cortical sleep-wake cycle14,15,16. For instance, prolonged stimulation of carotid sinus baroreceptors has been shown to induce sleep17, and facilitate the emergence of slow-wave activity (δ-oscillation)18. In addition, stimulating the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), a key component in the baroreflex pathway, can facilitate non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and REM sleep in rodents14. The activation of baroreflex triggers a blood pressure regulating procedure by modulating heart rate19, and the heart response in this procedure is partly reflected by the low-frequency (LF) component of the HRV time series20,21. In terms of respiration regulation, the breathing pattern is closely linked to the cortical arousal level. In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients, abnormal breathing leads to cortical arousal response, followed by sleep fragmentation and a reduction in both REM sleep and slow-wave sleep22. The dynamics of respiration were reported to be associated with the high-frequency (HF) component of the HRV time series, reflecting the respiratory effect on heart rate23. The above evidence implicates an indirect linkage between cortical activity and ANS rhythms in sleep. Therefore, the key information of dynamic BHI in sleep is expected to lie in the coupling of intrinsic oscillations between two distributed systems of the body, wherein the precision quantification for the BHI assessment is of significance, in particular.

In recent years, numerous studies have attempted to quantify the dynamic BHI through various perspectives. Early investigations considered the correlations between EEG power at spectral sub-bands and HRV indices as indications of brain-heart coupling strengths24,25. Although this model is straightforward to comprehend, it offers limited insight into the underlying physiological mechanisms between brain and heart dynamics. Subsequent research has introduced methods such as Granger causality26,27, and information-theoretic measures like transfer entropy9,10, maximal information coefficient28,29, joint symbolic analysis30, and convergent cross-mapping31 to explore temporal dependencies between brain and cardiac activities. However, the present methods of BHI assessment suffer from artifacts or spurious couplings elicited by the nonstationary and nonlinear nature of physiological/neural signals32,33, and the brain-heart interplay quantification is not addressed in a waveform modulation fashion. On the other hand, most of the existing pieces of literature have assumed that the ANS is subordinated to the CNS’s regulation in most of the physiological processes9,27,34. Nevertheless, it has also been implied that modulation of the ANS could influence specific aspects of sleep and emotion perception, supported by the evidence that vagal modulation occurs prior to cortical synchronization24. Therefore, to have insights into the effect of ANS on CNS, robust analysis of the brain waveform dynamics as a function of multiple sources of ANS oscillatory modulations is of particular importance.

To address these points, we proposed a heart-brain variational phase-amplitude coupling (HB-VPAC) framework by entangling EEG and RR interval time series, aiming to ensure robustness in quantifying nonlinear couplings between the heart and the brain noninvasively, as well as to provide precise waveform modulation assessment adaptive to irregular oscillations. To validate the reliability and robustness of the proposed HB-VPAC framework, we constructed both nonlinear and nonstationary simulated coupled signals for BHI assessment. Comparisons were also carried out with the other two PAC methods based on ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD) and empirical mode decomposition (EMD). The study seeks to elucidate the moment-to-moment coupling between cortical oscillatory dynamics, most notably slow-wave activity, and ANS control during natural sleep. We focus, first, on how parasympathetic dominance facilitates the progressive neuromuscular quiescence that characterizes deep sleep, and second, on how transient sympathetic activations, such as those elicited by OSA, can erode sympathovagal balance and precipitate cortical arousal. By applying BHI mapping across the entire sleep cycle, we aim to chart the real-time choreography between autonomic tone and cortical state, thereby clarifying the physiological dialog that underlies sleep stability and its disruption.

Results

Heart-brain variational phase-amplitude coupling framework

In this study, we aimed to quantify the modulation between the rhythmicities of the brain and the heart by introducing the variational phase-amplitude coupling framework. This framework measures the phase-amplitude coupling between the intrinsic patterns of RR intervals and EEG signals decomposed by the variational mode decomposition. A brief pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1. Briefly, we decomposed the preprocessed time series of electroencephalography (EEG) and RR intervals (Fig. 1A) into two sets of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) by employing the variational mode decomposition method (Fig. 1B), then calculated the cycle-by-cycle frequency of the two sets of IMFs, and determined the modulation index (MI) of instantaneous phase and amplitude distribution between comparable IMFs from the EEG and RR intervals (Fig. 1C, D). Next, we generated the surrogate data from individual MI-contributed decompositions by implementing a “block shuffle” procedure, followed by testing the statistical significance of the MI. The mean and standard deviation of the permuted MI were then used to determine the z-score of the original MI for each pair of components (Fig. 1E). Measurements that failed to exceed a significance threshold of \(\alpha =0.05\) were excluded from further analysis. Only MIs that survived rigorous statistical correction were retained to populate the comodulogram, with each significant value plotted at the phase-amplitude coordinate defined by the centroid frequencies of its IMF pair (Fig. 1F). It bears emphasis, however, that MI quantifies solely the statistical strength of coupling between RR-interval phase and EEG amplitude; it neither implies causality nor specifies the directionality of information flow between ANS and CNS. Table 1 summarizes the acronyms in this work.

A The data acquisition procedure. EEG and ECG are directly acquired from the polysomnography (PSG) equipment. R-peaks are extracted from ECG signals, and the RR interval time series is constructed from continuous adjacent R-peaks. B Decompose EEG (in blue) and RR intervals (in red) time series into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). EEG oscillations are decomposed into IMFs in several spectral sub-bands, such as δ (0.5 ~ 4 Hz), θ (4 ~ 8 Hz), α (8 ~ 13 Hz), and β (13 ~ 30 Hz); while RR intervals are decomposed into mainly LF (0.04 ~ 0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15 ~ 0.4 Hz) sub-bands of heart rate variability (HRV). C Perform Hilbert transform on IMFs of EEG and RR intervals to obtain instantaneous amplitudes and phases, respectively. D Calculate modulation index between the instantaneous phase and amplitude time series derived from IMFs of EEG and RR intervals. E Generate surrogate data to perform permutation testing on MI. The z-score threshold is set at α < 0.05. F Visualize heart-brain variational phase-amplitude coupling results in a phase-amplitude frequency plane. Figure components incorporate illustrations from Servier Medical Art (CC BY 4.0).

Comparisons of robustness assessments in simulated nonlinear and nonstationary coupled signals

To assess the robustness of our HB-VPAC framework against nonlinearity and nonstationarity, we applied the proposed framework to analyse simulated coupled signals under nonlinear and nonstationary scenarios, respectively, and compared them against PACs decomposed by EEMD and EMD. The simulated nonlinear or nonstationary coupled signal was designed by a phase-giving oscillation (simulated RR intervals) modulating an amplitude-giving oscillation (simulated nonlinear or nonstationary signal) with a 600 Hz sampling rate, and a 50-s total duration (Fig. S1). White noise with a variance of 0.5 was also added to the simulated coupled signal for all simulations.

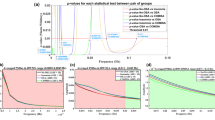

Figure 2 depicts the performance of PAC analyses in nonlinear coupled signals with existing methods. In general, results demonstrated that both EEMD and EMD methods suffered from spurious couplings at 0.1–0.6 Hz and 0.24–0.6 Hz (phase-amplitude frequency bin) brought by nonlinearity, whereas the VMD framework presented a stable coupling either at LF- or HF-modulated region, as per the nonlinearity distributions of the phase and amplitude frequencies with a maximum MI (Fig. 2A), indicating the proposed variational framework is more suitable for quantifying PAC in a nonlinear scenario compared to EMD- and EEMD-based PACs. Furthermore, we quantitatively analyzed the average deviation of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI from the pre-set 3 Hz in 20 realizations. As the degree of nonlinearity increased, the average deviation in both EEMD and EMD-based PACs also enlarged, while the deviation of VMD-based PAC remained almost the smallest across all levels of nonlinearity (Fig. 2B, C), suggesting the proposed HB-VPAC framework is more capable in nonlinear PAC assessment.

A The PAC results of VMD, EEMD, and EMD methods in the anti-nonlinearity experiment. The upper panel demonstrates the average comodulogram from 20 realizations of a signal with amplitude-giving oscillation having a degree of nonlinearity of 9, obtained with the three methods. The lower panel shows histograms of the phase and amplitude frequency bins at which the maximum PAC is observed, at all levels of nonlinearity, in both LF (0.04 ~ 0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15 ~ 0.4 Hz) phase-modulated regions of comodulogram, and for all three methods. B The average deviation of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI from the pre-set 3 Hz in the LF-phase-modulated region of comodulogram. C The average deviation of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI from the pre-set 3 Hz in the HF-phase-modulated region of comodulogram.

As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the averaged comodulograms of the three methods in the upper panel exhibit a certain degree of amplitude-frequency broadening. The histograms of nonstationarity in the lower panel illustrate a broadening and extension of the preferred amplitude frequency as the level of nonstationarity rises. This effect is likely attributed to random variations around the preset center frequency of the nonstationary amplitude-giving oscillation. The nonstationary amplitude-modulated signal had a considerable effect on both EMD and EEMD, causing the amplitude frequencies to scatter more widely around the central frequency. In addition, the variance of the amplitude-frequency of the maximum MI was employed to quantitatively assess the frequency scattering due to nonstationarity. Figs. 3B, C depict the comparisons of the three algorithms under varying degrees of nonstationarity. Compared to the EEMD method (black track) and EMD method (blue track), VMD (red track) was the lowest for almost all degrees of nonstationarities. As shown in Figs. 3B, C, the proposed method appears to be more effective in handling nonstationarity, offering clear advantages over the other approaches.

A The PAC results of VMD, EEMD, and EMD methods in the anti-nonstationarity experiment. The upper panel demonstrates the average comodulogram from 20 realizations of a signal with amplitude-giving oscillation having a degree of nonstationarity of 0.5, obtained with the three methods. The lower panel shows histograms of the phase and amplitude frequency bins at which the maximum PAC is observed, at all levels of nonstationarity, in both LF (0.04 ~ 0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15 ~ 0.4 Hz) phase-modulated regions of comodulogram, and for all three methods. B The variance of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI in the LF-phase-modulated region of comodulogram from 20 realizations. C The variance of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI in the HF-phase-modulated region of comodulogram from 20 realizations.

Validation of IMF-based time-resolved HRV-LF and HRV-HF markers

Prior to investigating whether HRV-LF and HRV-HF oscillations’ phases modulate EEG amplitudes, we employed VMD to adaptively decompose RR interval time series into multiple oscillations with varying center frequencies, or IMFs. Unlike the traditional time-frequency analyses, VMD eliminates the need for predefined basis functions, allowing for more adaptive analysis of irregular oscillations35. A previous study with a decomposition-like method has also achieved precise estimations of HRV-LF and HRV-HF markers by assessing their center frequencies with the changes in LF/HF markers after atropine injection captured36, suggesting the potential of VMD in time-resolved LF and HF markers estimation.

To validate the effectiveness of IMF-based time-resolved LF and HF components derived from VMD, twenty synthetic RR interval time series were generated based on the model from the previous section, followed by the performance of our method being compared with the state-of-the-art RR time-frequency analysis: Pseudo-smoothed Wigner-Ville distribution (WVD)37. A well-validated, robust time-resolved sympathetic and parasympathetic estimation38 served as the ground truth to validate whether our markers correlated with the actual sympathetic and parasympathetic activities. This method extracts the information of cardiac cycle duration and Poincaré plot to describe sympathetic and parasympathetic activities, deriving cardiac sympathetic index (CSI) and cardiac parasympathetic index (CPI), respectively38. Of note, the synthetic RR-interval generator retained all nonlinear and nonstationary design parameters from the preceding simulation (see preceding section), save for a fixed heart-rate standard deviation of 5 bpm. Following decomposition, the Hilbert spectrum was employed to derive the time-resolved power trajectories of each IMF-based autonomic marker.

In Fig. 4, we demonstrate the performance of WVD and our method in extracting time-resolved HRV-LF and HRV-HF markers. Fig. 4A demonstrates a simulated RR interval time series generated by the synthetic model. Similar trends were shown in both time-resolved LF and HF markers between WVD and our method (Fig. 4B, C). High correlations were also found between these time-resolved markers derived from the two methods (Table S1). Concerning autonomic inference, IMF-based HRV surrogates exhibited markedly weaker concordance with the synthetic ground truth than their PWVD-derived counterparts (Fig. 4D, E). Although this under-performance underscores a trade-off between interpretable, mode-resolved decomposition and absolute numerical fidelity, it was anticipated: our principal rationale for adopting VMD was never to eclipse PWVD in temporal–spectral precision, but rather to yield oscillatory constituents (IMFs) whose instantaneous phase and amplitude can be recovered unambiguously via the Hilbert transform—a convenience energy-based representation such as PWVD does not afford. Equally revealing is the systematic divergence of both methods from the ground-truth sympathetic drive. LF indices displayed pronounced deviations (Fig. 4B) and only modest correlations with the synthetic CSI (Fig. 4D), collectively suggesting that the conventional LF marker is ill-suited for capturing the fast, non-stationary fluctuations of sympathetic outflow.

A An example of the simulated RR interval time series. B Comparisons between time-resolved HRV-LF markers derived from WVD and VMD methods. CSI serves as the ground truth of sympathetic activity. The indices of CSI, WVD-LF, and VMD-LF were z-score normalized at the time level. C Comparisons between time-resolved HRV-HF markers derived from WVD and VMD methods. CPI serves as the ground truth of parasympathetic activity. The indices of CPI, WVD-HF, and VMD-HF were z-score normalized at the time level. D Spearman correlations between CSI and WVD-LF, as well as CSI and VMD-LF. Two-pair Wilcoxon signed-rank test was implemented on the VMD and WVD groups. (n = 20; Z = −1.1760; P = 0.2455). E Spearman correlations between CPI and WVD-HF, as well as CPI and VMD-HF. Two-pair Wilcoxon signed-rank test was implemented on the VMD and WVD groups. (n = 20; Z = −3.7893; ***P < 0.0001).

Quantifying BHI under the variational phase-amplitude coupling framework in healthy subjects

To investigate the BHI dynamics in sleep, we implemented the proposed framework to quantify the BHI strengths across sleep stages in healthy subjects. We first presented an example of the proposed framework, which included a sleep recording of one subject and the corresponding decomposed modes. Subsequently, a phase-amplitude comodulogram was constructed to visualize the modulation result (Fig. S2). We reviewed the comodulogram results from all subjects and channels to identify the specific frequency bands of PAC associated with sleep dynamics. Only the EEG δ-oscillatory amplitude is coupled with RR LF and HF oscillatory phases. The rest frequency bands of EEGs show no or few significant couplings after the surrogate testing over the comodulogram. Thus, MIs of the two frequency pairs (LF-δ and HF-δ) were selected for further analyses. Next, a comodulogram per subject, channel, and sleep stage was constructed. The maximum MIs for these two frequency pairs in these comodulograms were then used to quantify the coupling strength of BHI.

To demonstrate an atlas of overall phase-amplitude coupling distributions across sleep stages and brain regions, topoplots presenting average maximum MIs in six channels (F3, F4, C3, C4, O1, O2) driven by the two phase-frequency given modulations (LF-δ and HF-δ) were drawn meticulously (Fig. 5A). From the topoplot, the coupling strength of HF-δ is stronger in the deep sleep state (N3 stage), whereas that of LF-δ in the wakefulness state generally displays the strongest coupling strength compared to sleep. A tendency of increasing coupling strength was observed as sleep deepened, and reached its second-highest coupling strength at the REM stage. Interestingly, both coupling strengths of the two frequency pairs exhibited a dramatic decrease from wakefulness to the N1 stage, which is the transitional state from awake to sleep.

A Topoplots of the average MI of the two frequency pairs across sleep stages. B The LF-δ MIs of six channels across five sleep stages. (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: P = 0.6656, stage: ***P < 0.0001, channel: P = 0.2856) C The HF-δ MIs of six channels across five sleep stages. (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: *P = 0.0342, stage: ***P < 0.0001, channel: ***P = 0.0007) D–E Comparisons of LF-δ and HF-δ MIs of six channels across five sleep stages in healthy subjects (n = 72). D One-way ART-ANOVA was implemented in each channel subgroup with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons tests on LF-δ MIs. E Two-way ART-ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons tests on HF-δ MIs. F Variational heart-brain phase-amplitude coupling characterizes evolving modalities in the transition of sleep for healthy individuals. During the awake state, sympathetic activity plays a dominant role in sympathovagal balance, which potentially leads to increases in LF power. During the transitional state (N1 stage), the fluctuations of ANS and CNS break the connection between brain and heart, resulting in a decoupling phenomenon (both LF-δ and HF-δ coupling strength stay at low levels). During the sleep state, a dominant vagal tone and stronger EEG δ power emerge, which leads to a stronger coupling of HF-δ. All error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Figure components incorporate illustrations from Servier Medical Art (CC BY 4.0).

Next, the maximum MIs of LF-δ and HF-δ PACs were examined to compare expressions among sleep stages and EEG channels. Comparisons of LF-δ PAC among sleep stages grouped by channel were conducted. An aligned-rank transform ANOVA (ART-ANOVA) test was performed with channel and sleep stage as factors. The analysis highlighted a significant main effect of the sleep stage factor (Fig. 5B). The post-hoc analysis revealed that LF-δ PAC was significantly stronger in the awake and REM stages compared to other stages, while the N1 stage showed the weakest PAC across all six channels (Fig. 5C and Supplementary Data 1). It is noteworthy that the REM stage exhibited the second-highest PAC. An ART-ANOVA test on HF-δ MI with sleep stage and channel set as the fixed factors revealed that both sleep stage, channels, and their interaction reached significant levels (Fig. 5D). Post-hoc analyses revealed that, for all six channels, the N3 stage showed a significantly stronger HF-δ PAC than the other four sleep stages, especially referenced to the N1 stage (Fig. 5E and Supplementary Data 1). As ART-ANOVA suggested a significant interacting effect, a post-hoc test on channels, grouped by sleep stages, was implemented as well. Mainly, the coupling strength of HF-δ in the F3 channel was significantly stronger than the O2 channel in the wakefulness (Fig. 5E; \(P=0.0156\ast\)).

The above results suggest that the MIs derived from the variational framework can elucidate the BHI dynamics during sleep and help to identify evolving sleep stages. Furthermore, the behaviors of LF-δ and HF-δ across sleep stages partly reflect the dynamics of sympathovagal balance during sleep, which implies the ANS-modulated nature of the HB-VPAC framework. Moreover, previous studies have reported reduced connectivity between two systems in the physiology network in a transitional state, which aligns with our findings that both LF-δ and HF-δ MIs remained the lowest in the N1 stage9,12. The transitions in BHI-modulated modalities in sleep are summarized in Fig. 5F.

Variational phase-amplitude coupling framework discloses BHI patterns in OSA patients

We hypothesized that BHI indices derived from the variational phase-amplitude framework reflect intrinsic modulation dynamics in obstructive sleep-breathing patients. Thus, the comodulograms of the OSA patients at each channel and sleep stage (with or without sleep-disordered breathing events) were constructed. To investigate the dynamical changes of LF-δ and HF-δ couplings in OSA patients across sleep stages, two-way ART-ANOVA tests with channel and sleep stage as factors for the two frequency pairs were carried out (Fig. 6A, B). Results only revealed a significant main effect of sleep stage for both LF-δ and HF-δ PACs (Fig. 6C, D). In the post-hoc tests, statistically stronger LF-δ PACs were observed in the awake, N1, and REM stages, while HF-δ displayed a similar trend, with a stronger coupling was shown in awake and gradually decreased as sleep deepened (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Data 1). The topoplot also demonstrates such a tendency for both LF-δ and HF-δ PACs (Fig. 6E).

A The LF-δ MIs of six channels across five sleep stages were examined in OSA subjects (n = 61). (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: P = 0.9466, stage: ***P < 0.0001, channel: P = 0.7754) B The HF-δ MIs of six channels across five sleep stages were examined in OSA subjects (n = 61). (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: P = 0.9894, stage: ***P < 0.0001, channel: P = 0.4586) C One-way ART-ANOVA on LF-δ MIs implemented in each channel subgroup with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons tests. D One-way ART-ANOVA on HF-δ MIs implemented in each channel subgroup with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons tests. E Topoplots of the average MI of the two frequency pairs across sleep stages. F The HF-δ MIs of three obstructive sleep event subtypes across four sleep stages were examined in OSA subjects. (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: P = 0.2658, stage: ***P < 0.0001, subtype: *P = 0.0307) G, H Comparisons of HF-δ MIs at four sleep stages across three obstructive sleep event subtypes in OSA subjects. One-way ART-ANOVA on HF-δ MIs was implemented in each Subtype/Stage subgroup with Scheffe’s post-hoc comparisons. I The LF-δ MIs of three obstructive sleep event subtypes across four sleep stages were examined. (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: P = 0.6736, stage: P = 0.8887, subtype: **P = 0.0015) J, K Comparisons of LF-δ MIs of four sleep stages across three obstructive sleep event subtypes in OSA subjects. One-way ART-ANOVA on LF-δ MIs was implemented in each Subtype/Stage subgroup with Scheffe’s post-hoc comparisons. OA/N1 (n = 30), OA/N2 (n = 50), OA/N3 (n = 10), OA/REM (n = 35), OH/N1 (n = 49), OH/N2 (n = 50), OH/N3 (n = 27), OH/REM (n = 46), MH/N1 (n = 42), MH/N2 (n = 35), MH/N3 (n = 20), MH/REM (n = 33). All error bars indicate the mean ± SEM.

Sleep disordered breathing events manifest central, obstructive, and mixed subtypes, and can be categorized into apnea and hypopnea based on airway openness. We hypothesized a possible association between event subtypes and BHI, reflected in the PAC of the two frequency pairs. Therefore, we statistically examined both LF-δ and HF-δ PACs among sleep stages and sleep disorder breathing event subtypes (OA: obstructive apnea; OH: obstructive hypopnea; MH: mixed hypopnea). Since no significant effects were found for the channel factor or its interactions with sleep stages and event subtypes (Stage × Channel × Subtype, \(P > 0.05\)) in the three-way ART-ANOVA test, PAC values were averaged over the six channels (F3, F4, C3, C4, O1, O2) for further analysis. A two-way ART-ANOVA revealed significant main effects of both stage and subtype for HF-δ PAC (Fig. 6F). Post-hoc analysis revealed that, for OH and MH events, the coupling strength of HF-δ in the awake stage was statistically weaker compared to that in N3 stages (Fig. 6G and Supplementary Data 1). As ART-ANOVA also suggested a significant main effect of subtype, a post-hoc test was implemented accordingly. Mainly, the coupling strength of HF-δ in the MH event was significantly stronger than the OH event in the N2 stage (Fig. 6H, \(P=0.0279\ast\)). Next, an ART-ANOVA test on the LF-δ frequency pair was conducted, revealing only a significant main effect of subtype (Fig. 6I). Post-hoc exploration revealed that the LF-δ coupling magnitude remained invariant across sleep stages (Fig. 6J). In REM sleep, however, this coupling was markedly potentiated during OA relative to OH events (Fig. 6K; \(P=0.0149\ast\)).

Differences in BHI dynamics between OSA patients and healthy subjects

To verify whether the BHI dynamics are associated with OSA syndrome, we compared the modulation indices of OSA patients and healthy subjects across five sleep stages. Since no significant effects were found for the channel factor or its interactions with sleep stages and subject groups (Stage × Channel × Group, \(P > 0.05\)) in the three-way ART-ANOVA test, PAC values were averaged over the six channels (F3, F4, C3, C4, O1, O2) for further analysis. A Two-way ART-ANOVA on HF-δ demonstrated significant main effects of stage and interaction effects. Post-hoc test revealed significantly stronger coupling in healthy subjects at the N3 stage, indicating a relatively weaker parasympathetic activity for OSA patients during deep sleep (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Data 1). Similarly, when applying the same pipeline to LF-δ coupling, significant differences in coupling strength in the AW stage, N1 stage, and REM stage were observed between the two groups (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Data 1). Interestingly, unlike the healthy subjects, the connectivity between heart and brain in OSA patients at the transitional stage (N1 stage) remained relatively strong level compared to other stages, and did not show a “decoupling” phenomenon. This result indicates a blurred boundary established between awake and sleep states for OSA patients from the perspective of BHI, which emphasizes the significance of this disappearance and recurrence in brain-body interaction for sleep preparation. In addition, the decrease of HF-δ in deep sleep and the increase of LF-δ across sleep stages suggest a compromised regulatory ability to maintain sympathovagal balance for OSA patients during sleep, causing a weaker parasympathetic activity and stronger sympathetic activity, and thus a shallow sleep.

A The HF-δ MIs between two groups across five sleep stages were examined (Healthy: n = 72; OSA: n = 61). (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: ***P < 0.0001, stage: ***P < 0.0001, group: P = 0.5203; Scheffe’s post-hoc test, Healthy/N3 vs. OSA/N3, **P = 0.0027) B The LF-δ MIs between two groups across five sleep stages were examined (Healthy: n = 72; OSA: n = 61). (Two-way ART-ANOVA, interaction: ***P < 0.0001, stage: ***P < 0.0001, group: ***P < 0.0001; Scheffe’s post-hoc test, Healthy/AW vs. OSA/AW, ***P < 0.0001, Healthy/N1 vs. OSA/N1, ***P < 0.0001, Healthy/REM vs. OSA/REM, ***P < 0.0001).

Discussion

In this study, we focused on mechanisms that underlie cross-frequency interactions between brain (EEGs) and heart (RR intervals) rhythmicities, targeting specific frequency pairs, namely, LF-δ and HF-δ couplings, across sleep stages and pathological micro-events, proposing a variational phase-amplitude coupling framework. Phase-amplitude coupling quantifies the strength of modulation between the phase of one oscillatory component and the amplitude of another39,40,41, and it has emerged as a promising biomarker in cognitive processes42,43 and diseased states44,45. Such entangling modulations have proven to reflect long-range neuronal communication and coordination in the brain46, providing new insights into the nesting structure of physiological signals. In terms of BHI, current studies employed heartbeat-EEG time interval or heartbeat-related EEG amplitude to investigate the phase modulation of R-peaks on slow-wave EEGs, reflecting the phase-phase coupling relation between the brain and heart47,48. However, the phase-amplitude coupling mechanism between brain and heart rhythmicities remains unknown. In this work, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first proposal of PAC specifically for BHI in healthy and pathological sleep states. Meanwhile, BHI studies reported nonlinear interactions between EEG and HRV in sleep, especially involving the EEG δ band49,50. Linear approaches to BHI assessment, like Granger Causality, do not fully disclose the nonlinear BHI51. To provide precise and robust BHI assessments, our framework integrates the merits of VMD in handling the nonlinearity and nonstationarity52, plus the surrogate testing for the PACs quantification. Surrogate testing serves to validate the significance of brain-heart PAC and reduce the risk of spurious linkages due to nonstationarity or noise, improving precision in feature extractions for downstream group comparisons, which indirectly enhances group discrimination in this study (Fig. S3). Of note, surrogate testing itself was not designed to enhance group separability. Rather, it acts as a statistical filter to ensure that only genuine PAC interactions contribute to subsequent analyses. The proposed framework was validated by synthetic and real-world data.

In simulations, we validated the proposed framework with synthetic nonlinear and nonstationary brain-heart coupled modulations, and compared its performance with other baseline methods. Experimental results show that the framework presented fewer spurious couplings under both scenarios compared to EMD and EEMD methods, revealing that our framework holds promise in PAC assessment for nonlinear and nonstationary signals. Although IMF-derived, time-resolved HRV-LF and HRV-HF indices fall short of the WVD-based proxies in their concordance with the autonomic metrics, the present framework confers a constellation of compensatory strengths. This under-performance underscores a trade-off between interpretable, mode-resolved decomposition and absolute numerical fidelity. By dispensing with fixed basis functions, VMD performs data-adaptive decomposition; by isolating individual modes, it delivers targeted physiological insight; and by preserving phase and amplitude fidelity, it yields interpretability unattainable through conventional transforms. These virtues render the technique especially apt for dissecting the subtle, non-stationary signatures of autonomic control under analytically adverse conditions, positioning it as a resilient and physiologically grounded instrument for brain-heart interaction research. In real-world data, our overall results suggest that the BHI PACs with EEG δ-amplitude serve a significant role in the sleep processing pathway, which is in line with past reports showing that slow wave, characterized by high-amplitude δ-oscillations, is linked with deep sleep53,54. The δ-oscillation is commonly regarded as a hallmark of unconsciousness55, and it is a major element in most of the studies that involve sleep and reduced awareness in brain-heart interplay9,25,47,56. For example, evidence suggests a correlation and information transfer between cardiac vagal activity and EEG δ power in sleep9,25. In a comatose state, phase synchronization was also shown between EEG slow waves (especially the δ-oscillations) and heartbeats47, revealing a sleep-like time interval where a heartbeat is most likely to precede the slow-wave onset by about 450 ms48. In addition, severe hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, a brain injury induced by cardiac arrest, is reflected by aberrant lower couplings between the HRV-LF component and EEG δ power in comatose patients56. In terms of the cardiac aspect of BHI, our results demonstrate that HRV-LF and -HF components of RR intervals serve as important contributors in BHI, reflecting sympathovagal and parasympathetic activities of the ANS, respectively57,58. Early investigation also reported that the higher-order interactions between ANS components and EEGs reveal functional connectivities in the central-autonomic network, a brain network that governs the top-down regulation of the ANS, in slow-wave sleep59.

Being an intricate physiological state, sleep involves time-varying multi-organ and multi-system interactions throughout sleep cycles1,12, the brain-heart interactions in particular13. Thus, evolving BHIs across sleep phases were accessed by our framework. Our results in healthy subjects showed that LF-δ PAC is stronger in the awake and REM stages and weaker in the N1 stage, whereas HF-δ presents a stronger coupling in the N3 stage than in the other four stages (Fig. 5). These observations could be attributed to the dynamics of dominant components in EEGs associated either with sympathetic activity or vagal tone in RR intervals depending on the varying sleep stages. For instance, wakefulness (awake stage) typically exhibits dominant sympathetic activity of ANS, while deep sleep (N3 stage) is characterized by predominant parasympathetic activity60. Consequently, LF-δ PAC is stronger in sleep stages dominated by sympathetic activity (awake and REM stages), whereas HF-δ PAC is stronger in those dominated by parasympathetic activity (N3 stage). These findings suggest that BHI quantified by the proposed two PACs could, to some extent, reflect the sympathetic and parasympathetic dynamics in sleep, albeit the LF power as a marker of sympathetic activity is debatable61.

An interesting observation was also revealed in healthy subjects that both LF-δ and HF-δ PACs display nearly the weakest coupling in the N1 stage compared to the other four stages (Fig. 5). As the N1 stage represents a transitional period from wakefulness (awake stage) to light sleep (N2 stage), investigating physiological characteristics in this stage could provide better insights into the mechanism of the wake-sleep cycle. In recent years, numerous studies have reported dramatic alterations in the topology of the brain network during transitional periods within the internal system. For example, it has been shown that the breakdown or decoupling of the brain-periphery network occurred during the sleep transitional period, indicating linkages between brain network interaction and physiological states12. A previous study also observed a “vanishing” information transfer during stage-specific analysis using transfer entropy9. Considering that internal alterations in a dynamic physiological system can modify its interactions with other systems, the dissipation of such brain-heart connectivity or coupling, occurring in the long-range communication of the cortical and cardiac dynamics during the transitional period from awake to sleep, helps to explain the observed decoupling of HRV-LF and -HF components and EEG δ-oscillations in the N1 stage.

The accurate diagnosis and treatment of OSA rely on precise estimation of sleep status and the reliable identification of sleep-disordered breathing events. Past reports detected sleep-disordered breathing events mainly by nasal pressure signal62 or pulse oximetry signal63, but the dynamic BHI in these events is not yet known. In addition, the pathophysiology of OSA is featured by repeated collapses of the pharyngeal airway during sleep, resulting in unstable respiration, which subsequently triggers arousal responses64. This process involves the activity of ANS modulating the behavior of CNS7. Therefore, we hypothesized that the BHI indices derived from our framework offer supportive and subtle information on sleep-disordered breathing events. In the current study, we applied the proposed framework to quantitatively analyze BHI in OSA patients across sleep stages and pathological obstructive breathing event subtypes. Our results revealed stronger HF-δ coupling in the MH event compared to the OA event in the N2 stage, whereas stronger LF-δ coupling was observed in the OA event compared to the OH event in the REM stage (Fig. 6). MH events exhibit features of both central (no discernible respiratory effort) and obstructive (blocked upper airway) hypopnea, characterized by partial airway collapse rather than the complete collapse seen in pure OA65. This partial collapse may preserve stronger parasympathetic modulation, reflected in the HRV-HF component, which could synchronize with cortical slow-wave activity observed in EEG recordings. This suggests a compensatory mechanism where vagal activity stabilizes cortical function during less severe respiratory disturbances. In contrast, complete airway collapse during OA events induces greater inspiratory efforts than in OH event66, triggering a more pronounced autonomic stress response and increasing LF power67. These findings indicate that, in REM sleep, the brain’s response to severe respiratory disturbances is mediated by heightened autonomic fluctuations, which underlie the observed differences in BHI results between OA and OH events. These findings suggest the existence of changing coupling states between autonomic components and slow-wave EEG activity, among different sleep disorder breathing event subtypes in specific sleep stages. Nevertheless, the precise relationship between event subtypes and BHI remains unclear.

Additionally, we compared BHI dynamics between OSA patients and healthy subjects across sleep phases. Our results showed that OSA patients exhibited significantly stronger LF-δ couplings across wake and light sleep, and weaker HF-δ couplings in deep sleep, compared to healthy subjects (Fig. 7). Prior studies reported elevated sympathetic activity and reduced cardiac parasympathetic modulation in OSA patients68,69, with ANS dysregulation quantified via time-resolved HRV analyses70. As HRV-LF represents sympathovagal tone and HRV-HF indexes parasympathetic activity, our results suggest that OSA-related ANS dysfunction manifests through LF and HF dynamics coupled with EEG δ-oscillations. Additionally, EEG δ-oscillations significantly contribute to distinguishing OSA patients from healthy individuals in BHI analyses, aligning with prior findings71. For example, sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) patients show reduced causal predictability between EEG δ and cardiac dynamics compared to healthy subjects, with normalization post-continuous positive airway pressure treatment71. Furthermore, our BHI results indicate preserved brain-heart coupling (without the “decoupling” phase) in OSA patients during wake-sleep transitions, a period of marked ANS and CNS fluctuations. These findings suggest that the dis-connect and re-connect of brain-heart coupling during sleep onset reflect a compensatory mechanism crucial for sleep preparation.

The underlying mechanism of ANS-CNS modulation during sleep has drawn much attention in recent studies, and primary investigations mainly focused on how the components that regulate cardiac cycles affect brain activities14,72,73. In this study, the phase of HRV frequency components (LF and HF) of RR intervals was found to modulate the amplitude of EEG δ-oscillation. Since the HRV-LF and -HF represented the cardiac components in BHI in the current study, exploring the physiological meaning and involved neural linkages of LF and HF helps to provide further insights into how exactly the heart rhythm modulates brain dynamics during sleep.

The HRV-LF component (0.04 ~ 0.15 Hz) in RR intervals represents the so-called Mayer wave (around 0.1 Hz) elicited by baroreflex (about 10 s to complete the feedback loop)20,21, a negative feedback loop that modulates cardiovascular activity. The baroreflex mainly consists of peripheral baroreceptors, the NTS, and the medulla. Baroreflex function is governed by two primary pathways. The first pathway involves glutamatergic projection from NTS to the nucleus ambiguous, where it activates cholinergic preganglionic parasympathetic neurons. The second pathway involves the NTS projection to the caudal ventrolateral medulla, where it activates GABAergic neurons that inhibit sympathetic adrenergic neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla14,19. Baroreflex function is known to be modulated by neural activity during sleep-wake cycles19. For instance, studies have demonstrated that the baroreflex set point is reduced significantly during NREM sleep compared to wakefulness, leading to blood pressure reduction during sleep. This resetting phenomenon causes transient changes in ANS activity during the sleep preparation period74,75, and could be the reason for the decoupling of ANS-CNS that occurred in this study, reflected by the reduction of LF-δ PAC in the N1 stage. In addition, the baroreflex was also proven to affect sleep-wake brain states reversely. Previous studies involving electrical stimulation, lesion, and pharmacological intervention experiments have also highlighted the role of baroreflex in promoting sleep-like EEG synchronization, particularly the δ-oscillation76,77,78. However, the underlying neural mechanism of baroreflex influences sleep-wake brain states remained unknown. Nevertheless, prior findings on the reciprocal influence between baroreflex activity and sleep-wake brain states, along with evidence from electrical stimulation experiments, suggest that HRV-LF and EEG δ-wave activity may exhibit a modulated relationship, mediated by baroreflex mechanisms linked to blood pressure fluctuations. While our current methodology does not permit directional inference, we hypothesize that the observed LF-δ MI may reflect an interaction in which cardiovascular oscillations modulate cortical activity via autonomic pathways. We note that surface EEG cannot capture subcortical structures such as the brainstem, which are central to baroreflex function. Future studies incorporating subcortical recordings and source localization techniques would be necessary to more accurately characterize the direction and mechanisms of such interactions.

The HRV-HF component (0.15 ~ 0.4 Hz) in RR intervals, closely related to respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA)79, reflects the effect of cardiac rhythm modulation, where the heart rate increases during inspiration and decreases during expiration, in synchrony with the respiratory cycle. This rhythmic fluctuation in heart rate represents a physiological manifestation of respiratory gating, wherein the ANS adjusts the heart rate in response to the respiratory phases23. Respiratory gating plays a critical role in regulating multiple brain regions involved in the sleep-wake circuit that respond to CO2 levels. For instance, parasympathetic preganglionic neurons in the medullary nucleus are modulated by respiratory activity80, which regulates input from nasopharyngeal receptors, chemoreceptors, and baroreceptor81. Therefore, changes in respiratory rhythm during sleep may affect the sleep-wake circuit and lead to alterations in CNS activity reflected by brain oscillations. In addition, studies on rodents have shown that respiration plays an essential role in modulating neural activity, particularly in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)82,83, a region associated with emotional regulation. Current studies also reported that alternating breathing patterns (which induce changes in HRV-HF frequency component) alter functional connectivity of the brain network (EEG oscillatory patterns) in human individuals5, indicating linkages between RR intervals and EEG oscillations matter in respiration. Taken together, the data lend credence to the view that HF-δ PAC indexes a bona-fide physiological dialog in which respiratory-linked autonomic outflow momentarily sculpts cortical excitability. Nevertheless, the present design precludes any inference regarding the direction—afferent, efferent, or bidirectional—of this coupling, let alone its causal structure. Moreover, because scalp EEG is blind to brainstem and other subcortical respiratory nuclei that orchestrate autonomic control, the neural circuitry underpinning this relationship remains, at best, a matter of informed speculation.

The proposed heart-brain variational phase-amplitude coupling framework unveils the structure of sleep by extracting crucial insights into ANS-CNS interactions during sleep, offering a new perspective on ANS modulation. Although the proposed framework demonstrates its effectiveness and robustness in exploring sleep dynamics, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, our method captures statistical associations rather than causality between RR phase and EEG amplitude due to the nature of MI measurement, necessitating further research into heart-brain phase-amplitude coupling directionality. Second, while our approach quantifies brain-heart dynamic coordination beyond simple activity changes, autonomic and cortical variations themselves may modulate the underlying dynamics of BHI, requiring additional experiments for confirmation. Finally, although we established an indirect BHI-neural pathways link, further research is needed to comprehensively clarify the CNS-ANS top-down and bottom-up mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Materials and preprocessing

This study employed three publicly available cohorts: (1) The ISRUC-S3 dataset84 includes overnight sleep recordings of 10 healthy subjects (gender: 9 males and 1 female; age: 40 ± 10 years). Each subject’s recording encompasses 6 EEG channels, 1 ECG channel, 3 EMG channels, and 2 EOG channels (all sampled at 200 Hz). (2) The MASS-SS3 dataset85 includes 62 healthy subjects (gender: 28 males and 34 females; age: 42.5 ± 18.9 years). Each subject’s recording contains 20 EEG channels, 1 ECG channel, 3 EMG channels, and 2 EOG channels (all sampled at 256 Hz). (3) The ISRUC-S1 dataset84 includes 100 patients with various types of sleep disorders, of which 62 patients have OSA syndrome. Each subject contains 6 EEG channels, 1 ECG channel, 2 EOG channels, and 3 EMG channels (all sampled at 256 Hz). Among the 62 OSA patients, one subject’s EEG recording only had four channels, which were not considered for further analysis. In this study, recordings of the rest of the 61 OSA subjects (gender: 32 males and 29 females; age: 54.6 ± 14.3 years) were used for analysis (Supplementary Data 2). Polysomnography (PSG) recordings of the three cohorts were first segmented into multiple 30-s epochs. Then, each epoch was manually inspected into five sleep stages, including Awake (AW stage), NREM sleep (N1, N2, N3 stage), and REM sleep (REM stage) by sleep experts, following the guidelines of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM)86. Written informed consent was obtained from every participant across all datasets. All experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Research Ethics Boards of Hôpital Sacré-Coeur de Montréal (RC-HSCM) and Coimbra University Hospital (CHUC). The study was conducted in full compliance with all ethical standards governing research involving human participants.

EEG data were preprocessed with a 4th-order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.5–40 Hz) to remove high-frequency artifacts. Single-point outliers were identified and interpolated using cubic splines based on a manually predetermined threshold from visual inspection of abrupt amplitude changes. Artifacts related to eye movements and other sources were removed by independent component analysis (ICA).

ECG signals underwent similar preprocessing with a 4th-order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.5–30 Hz), followed by baseline correction. R-peaks were detected using the Pan-Tompkins algorithm87, with ectopic beats and misdetections manually corrected against raw ECG recordings. RR intervals were calculated as consecutive R-peak differences. RR interval time series (RR signals) were resampled to 200 Hz (ISRUC-S3 and ISRUC-S1 datasets) or 256 Hz (MASS-SS3 dataset) to maintain temporal synchronization with EEG recordings.

Variational phase-amplitude coupling framework

The variational phase-amplitude coupling framework integrates two key components: variational mode decomposition and phase-amplitude coupling. Variational mode decomposition decomposes EEG signals and RR intervals into intrinsic mode functions, while phase-amplitude coupling quantifies the modulation between corresponding functions derived from these two signals. An overview of the framework is provided in Fig. 1, with technical details elaborated below.

Variational mode decomposition: Variational Mode Decomposition, or VMD, is an advanced signal decomposition approach that utilizes the principles from the Hilbert transform and Wiener filter, which can decompose a real-valued signal \(f(t)\) into intrinsic sub-components, or modes, \({u}_{k}(k=1,2,{\mathrm{..}}.,K)\)35. These modes that are generated by VMD feature limited bandwidth, with their formations following the amplitude-modulated-frequency-modulated signal. To acquire the bandwidth of a mode, the unilateral frequency spectrum was first obtained from its analytic form through the Hilbert transform. Then, the signal was multiplied by an exponential factor to shift the spectrum of each sub-component to the “baseband”, ensuring that the decompositions were aligned with the estimated center frequencies. Finally, the L2-norm of the frequency-shifted signal was calculated to determine the bandwidth of each mode. This process resulted in a constrained variational optimization problem, which can be mathematically stated as

where \(\{{u}_{k}\}:=\{{u}_{1},{\mathrm{..}}.,{u}_{K}\}\) represents the collection of all the decomposed modes, \(\{{\omega }_{k}\}:=\{{\omega }_{1},{\mathrm{..}}.,{\omega }_{K}\}\) refers to the collection of their corresponding center frequencies, \(\delta (t)\) is the Dirichlet function, and * is the convolution operator symbol. To solve the variational optimization problem, and to identify the mode with minimum bandwidth, a quadratic penalty factor α and a Lagrangian multiplier λ were introduced. The penalty factor α helps preserve the reconstruction quality of a signal, especially when there is significant noise interference, while the Lagrangian multiplier λ relaxes the constraints, allowing the optimization to proceed in an unconstrained manner. This approach leads to the formulation of an augmented Lagrangian function:

The alternating direction method of multipliers (ADMM) was then applied to solve the augmented Lagrangian function, and the optimal solution was directly updated in the Fourier domain using Wiener filtering, leveraging Parseval isometry. The intrinsic mode functions (IMF) \(\{{u}_{k},k=1,{\mathrm{..}}.,K\}\) derived from VMD are arranged in descending order of their frequencies and possess the characteristic of quasi-orthogonality.

Cycle-by-cycle frequency framework: For each of the extracted IMF, we computed and utilized its cycle-by-cycle frequencies rather than instantaneous frequencies to prevent the widely varying frequency problem caused by sharp intra-wave modulations. The goal was to provide a more stable representation of the signal’s frequency characteristics. To assess the cycle frequencies of the Jth IMF, where \(j=1,2,{\mathrm{..}}.,L\), and L is the total number of IMFs, we only allowed increments smaller than \(\pi /4\) for the phase time series \({\varphi }_{j}(t)\) to decrease, ensuring its monotonicity and the unwrapped phase. Cycle conversions were defined as the time points where the unwound phase time series crossed an \(2\pi\) integer increment. The cycle-by-cycle frequency time series \(f(s,t)\) of an input signal \(f(t)\) with a sampling frequency \({f}_{s}\), which spans from time point s and ends at time point t, can be expressed as:

We set \({F}_{j}(u)=f(s,t)\) for all u between s and t. This enables the cycle-by-cycle frequency to effectively serve as a secant approximation to the instantaneous frequency, or the derivative of the instantaneous phase. In this context, the cycle-by-cycle frequencies strike an effective balance between instantaneous frequencies and a simple smoothing method, allowing an adaptive, irregular, meanwhile concentrated inter-wave modulation.

Modulation index: The modulation index is an ideal quantification method for cross-frequency coupling (for PAC quantification) among other methods like phase-locking values, the correlation coefficients, and mean vector length, etc.39. The MI calculation rests on Shannon entropy and its inverse entropy measure, featuring its flexibility and sensitivity to the dependence of amplitudes over phases. The MI algorithm is illustrated as follows. The process begins by dividing the phase domain \((0,2\pi ]\) into N bins (N = 20 in this study). Then, the high-frequency amplitudes are binned according to the low-frequency phases. The high-frequency amplitudes within each bin are summed and then divided by the total amplitude to obtain a distribution, denoted as P, which represents the proportion of high-frequency amplitudes occurring within each phase bin. Next, the Shannon entropy is formulated as: \(H(P)=-{\sum }_{j=1}^{N}p(j)\log [p(j)]\). The Kullback-Leibler (KL) distance is computed as \({D}_{KL}(P,U)=\,\log (N)-H(P)\), where U is the uniform distribution. The KL distance is then normalized by the maximum possible entropy \(\log (N)\), yielding a quantity between 0 and 1, defined as MI:

The MI index of 1 indicates all amplitude occurs within a single-phase bin, corresponding to a Bernoulli distribution, while a value of 0 reflects a uniform distribution across all phase bins.

Surrogate testing: To maintain consistency within the cycle-by-cycle framework, a “block shuffle” process was carried out, where cycles (treated as blocks) were manipulated based on their corresponding phase and amplitude modulations. Following this, the blocks were randomly reordered and permuted. To derive the empirical distribution for both the amplitude- and phase-giving components, the phase and amplitude blocks or cycles were shuffled33. In this approach, each cycle in the phase and amplitude time series was assigned a unique index, assuming that the cycles were independent of one another. These cycle indices were then permuted randomly to produce a rearrangement of the cycles. Next, the cycles (potentially of unequal lengths) were concatenated based on the newly shuffled indices. This process led to the damage of the temporal structure between low-frequency phases and high-frequency amplitudes, while the inherent characteristics of the individual cycle remained intact. The disruption in PAC meant that the MI between the shuffled components no longer reflected any meaningful phase-amplitude interaction. In this study, the “block shuffle” procedure was repeated 100 times for each pair of IMFs. The mean and standard deviation of the resulting MI distribution were then computed to calculate the z-score for the observed MI for each component pair. MI measurements that did not surpass a predefined significance threshold of \(\alpha =0.05\) were excluded from the analysis. Only statistically significant modulation indices were retained for the comodulogram; from these, the peak values within the LF-δ and HF-δ bands were extracted as summary coupling metrics for subsequent group-level analyses.

Visualization of CFC frequency plane: The comodulogram provides a visual representation that highlights specific frequency pairs exhibiting strong couplings. To achieve a higher frequency resolution, we projected the MIs of IMF pairs onto a phase-amplitude frequency plane, using the cycle-by-cycle frequencies of the IMFs for the mapping. For each sample point, the MI associated with a pair of components was positioned in the frequency plane, with its coordinates determined by the cycle frequencies of the phase and amplitude modulations. The redistributed MIs were then averaged within the rectangular patches corresponding to specific frequency coordinates. In this study, we computed the average MI within each 0.01-Hz low-frequency bin and 0.5-Hz high-frequency bin (phase frequency amplitude frequency), with phase frequency (RR intervals) spanning from 0 to 0.5 Hz, and amplitude frequency (EEG) spanning from 0 to 60 Hz. For the simulations, the high-frequency bin was set to 0.2 Hz, along the low-frequency bin was adjusted to 0.02 Hz.

Simulated data

Simulated RR intervals: The simulated RR interval time series (RR signals) was generated by the dynamical synthetic model proposed by McSharry et al.88 The simulated RR signals generation procedure was described as follows. A combination of the two Gaussian distributions that lie in LF (0.04 ~ 0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15 ~ 0.4 Hz) bands, respectively, generated the power spectrum \(S(f)\) of the RR interval, which can be mathematically stated as

where \({f}_{1},{f}_{2}\) and \({c}_{1},{c}_{2}\) refer to the center frequency and bandwidth in the LF and HF bands, respectively. The power in the LF and HF bands was denoted by \({\sigma }_{1}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{2}^{2}\), with the LF/HF ratio expressed as \({\sigma }_{1}^{2}/{\sigma }_{2}^{2}\). The Gaussian distribution was designed to reflect the power spectrum of the real RR interval time series, with the LF component representing Mayer waves, and the HF component modeling respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Then, the designed RR intervals with a specific power spectrum \(S(f)\) can be constructed by performing an inverse Fourier transform on a complex sequence. This sequence is characterized by an amplitude of \(\sqrt{S(f)}\), and its phase is randomly distributed between 0 and 2π. To obtain the desired statistical properties, the resulting time series was appropriately scaled by a constant, and adjusted by an offset value, ensuring the designed mean and standard deviation were achieved.

Simulated nonlinear/asymmetric signal: To replicate the effects of non-sinusoidal and nonlinear modulations, a common source of artifacts in brain activity, we simulated the nonlinear signal in our experiment. The simulated nonlinear or asymmetrical oscillation was generated by combining two half-cycle sinusoidal patterns with identical amplitudes but potentially different periods. The extent of nonlinearity was quantified by the ratio of the periods of the two sine functions32.

Simulated nonstationary signal: To replicate the effects of frequency modulation in the brain signal, the cycle-by-cycle jitter was introduced into the amplitude-giving signal, resulting in a nonstationary oscillation. The simulated signal was constructed by multiplying the input by a piecewise constant amplitude vector. The frequencies or amplitudes of the signal were drawn uniformly from a given interval that centered at a pre-set frequency or amplitude, with a certain degree of variability. The degree of nonstationarity was naturally defined as the variability of the frequency and amplitude of the signal. The detailed implementation procedure was introduced by Pittman-Poletta et al.33.

Simulated coupled nonlinear/nonstationary signal: The simulated coupled signal was generated, with a 600 Hz sampling rate and a 50-s total duration, by combining a phase-giving oscillation \({S}_{p}\) and an amplitude-giving oscillation \({S}_{a}\). White noise N with a variance of 0.5 was also added to the coupled signal for all simulations. The simulated coupled nonlinear or nonstationary signal used in our study is mathematically stated as

In simulations, the amplitude-giving oscillation \({S}_{a}\) was either the nonlinear or nonstationary simulated signal. The phase-giving oscillation was the simulated RR intervals \({S}_{p}\) generated by the dynamical ECG synthesis model mentioned above. Of note, the DC component of RR intervals was removed by subtracting the median value of the time series to guarantee a precise phase extraction. The parameters of the model remain the same across simulations, and are described as follows: \({f}_{1}=0.1,{f}_{2}=0.25,{c}_{1}=0.01,{c}_{2}=0.01,{\sigma }_{1}^{2}/{\sigma }_{2}^{2}=1.\) In addition, the center frequency of the simulated nonlinear or nonstationary signal was set at 3 Hz. The degree of nonlinearity was varied from 1 to 9, with a step of 2, while the degree of nonstationarity was varied from 0.1 to 0.5, with a step of 0.1.

Comparison with other decomposition methods

We compared HB-VPAC to nonstationary and nonlinear simulated signals modulated by simulated RR intervals against PACs decomposed with EEMD and EMD. The details of the calculation of EEMD89 and EMD90 have been documented in the literature. In the experiments, VMD, EEMD, and EMD were used for nonlinear or nonstationary coupled signal decomposition, while VMD was implemented to decompose RR intervals \({S}_{p}\). To conduct the quantitative analysis for anti-nonlinearity evaluation, the average absolute deviation of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI from the pre-set center frequency of the amplitude (3 Hz) was calculated in both LF- and HF-modulated regions (LF: phase frequency from 0.04–0.15 Hz; HF: phase frequency from 0.15–0.4 Hz). For the simulation against nonstationarity, the variance of the amplitude frequency of the maximum MI was used to quantitatively assess the frequency scattering brought by nonstationarity.

Statistics and reproducibility

To evaluate the performance of the HB-VPAC framework in distinguishing sleep stages, sleep-disordered breathing event subtypes, and EEG channels across pairwise frequencies, Aligned-Rank Transform Analysis of Variance (ART-ANOVA) was applied. In the analysis, the subject was treated as a random factor. Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed P-values, with values below 0.05 indicating significance. ART-ANOVA is a nonparametric factorial analysis that allows for multiple variables, interactions, and repeated measures, which is comparable to a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM)91. The normality of the data was evaluated using the Jarque-Bera test. To examine pairwise differences in means, the Student’s t-test was employed for multiple comparisons. Tukey’s or Scheffe’s adjustment for P value was applied in the post-hoc test procedure. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.1), a language and environment for statistical computing, and the package ARTool was used to conduct ART-ANOVA92. Detailed descriptions of the statistical tests and corresponding P-values for each experiment are provided in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Anonymized physiological data have been deposited in ISRUC and MASS (https://sleeptight.isr.uc.pt/ and https://borealisdata.ca/dataverse/MASS). Numerical source data for all manuscript graphs are provided in Supplementary Data 3. Requests for other resources will be directed to and fulfilled by the corresponding author.

Code availability

Code to run the HBVPAC is available at the GitHub repository: https://github.com/dkanklda123/HBVPAC.

References

Engelen, T., Solcà, M. & Tallon-Baudry, C. Interoceptive rhythms in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1670–1684 (2023).

Critchley, H. D. & Harrison, N. A. Visceral influences on brain and behavior. Neuron 77, 624–638 (2013).

Jin, H., Li, M., Jeong, E., Castro-Martinez, F. & Zuker, C. S. A body–brain circuit that regulates body inflammatory responses. Nature 630, 695–703 (2024).

Candia-Rivera, D., Catrambone, V., Thayer, J. F., Gentili, C. & Valenza, G. Cardiac sympathetic-vagal activity initiates a functional brain–body response to emotional arousal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119599119 (2022).

Mather, M. & Thayer, J. F. How heart rate variability affects emotion regulation brain networks. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 19, 98–104 (2018).

Margolis, K. G., Cryan, J. F. & Mayer, E. A. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: from motility to mood. Gastroenterology 160, 1486–1501 (2021).

Silvani, A., Calandra-Buonaura, G., Dampney, R. A. & Cortelli, P. Brain–heart interactions: physiology and clinical implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 374, 20150181 (2016).

Varga, S. & Heck, D. H. Rhythms of the body, rhythms of the brain: Respiration, neural oscillations, and embodied cognition. Conscious. Cogn. 56, 77–90 (2017).

Faes, L., Nollo, G., Jurysta, F. & Marinazzo, D. Information dynamics of brain–heart physiological networks during sleep. N. J. Phys. 16, 105005 (2014).

Catrambone, V., Talebi, A., Barbieri, R. & Valenza, G. Time-resolved brain-to-heart probabilistic information transfer estimation using inhomogeneous point-process models. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 3366–3374 (2021).

Park, H.-D. & Blanke, O. Heartbeat-evoked cortical responses: Underlying mechanisms, functional roles, and methodological considerations. Neuroimage 197, 502–511 (2019).

Bashan, A., Bartsch, R. P., Kantelhardt, J. W., Havlin, S. & Ivanov, P. C. Network physiology reveals relations between network topology and physiological function. Nat. Commun. 3, 9 (2012).

de Zambotti, M., Trinder, J., Silvani, A., Colrain, I. M. & Baker, F. C. Dynamic coupling between the central and autonomic nervous systems during sleep: a review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 90, 84–103 (2018).

Yao, Y. et al. Cardiovascular baroreflex circuit moonlights in sleep control. Neuron 110, 3986–3999. e3986 (2022).

Narkiewicz, K. & Somers, V. Sympathetic nerve activity in obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Physiol. Scand. 177, 385–390 (2003).

Kanki, M. et al. Poor sleep and shift work associate with increased blood pressure and inflammation in UK Biobank participants. Nat. Commun. 14, 7096 (2023).

Koch, E. Die irradiation der pressoreceptorischen kreislaufreflexe. Klin. Woche. 11, 225–227 (1932).

Bonvallet, M., Dell, P. & Hiebel, G. Tonus sympathique et activité électrique corticale. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 6, 119–144 (1954).

Suarez-Roca, H., Mamoun, N., Sigurdson, M. I. & Maixner, W. Baroreceptor modulation of the cardiovascular system, pain, consciousness, and cognition. Compr. Physiol. 11, 1373 (2021).

Laborde, S., Mosley, E. & Mertgen, A. A unifying conceptual framework of factors associated to cardiac vagal control. Heliyon 4, e01002 (2018).

Rosenbaum, M. & Race, D. Frequency-response characteristics of vascular resistance vessels. Am. J. Physiol. 215, 1397–1402 (1968).

Deegan, P. & McNicholas, W. Pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur. Resp. J. 8, 1161–1178 (1995).

Eckberg, D. L. Topical review: the human respiratory gate. J. Physiol. 548, 339–352 (2003).

Ako, M. et al. Correlation between electroencephalography and heart rate variability during sleep. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 57, 59–65 (2003).

Jurysta, F. et al. A study of the dynamic interactions between sleep EEG and heart rate variability in healthy young men. Clin. Neurophysiol. 114, 2146–2155 (2003).

Faes, L., Kugiumtzis, D., Nollo, G., Jurysta, F. & Marinazzo, D. Estimating the decomposition of predictive information in multivariate systems. Phys. Rev. E 91, 032904 (2015).

Orjuela-Cañón, A. D., Cerquera, A., Freund, J. A., Juliá-Serdá, G. & Ravelo-García, A. G. Sleep apnea: tracking effects of a first session of CPAP therapy by means of Granger causality. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 187, 105235 (2020).

Valenza, G. et al. Combining electroencephalographic activity and instantaneous heart rate for assessing brain–heart dynamics during visual emotional elicitation in healthy subjects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 374, 20150176 (2016).

Catrambone, V., Greco, A., Scilingo, E. P. & Valenza, G. Functional linear and nonlinear brain–heart interplay during emotional video elicitation: A maximum information coefficient study. Entropy 21, 892 (2019).

Schulz, S., Haueisen, J., Bär, K.-J. & Voss, A. Altered causal coupling pathways within the central-autonomic-network in patients suffering from schizophrenia. Entropy 21, 733 (2019).

Schiecke, K. et al. Brain–heart interactions considering complex physiological data: processing schemes for time-variant, frequency-dependent, topographical and statistical examination of directed interactions by convergent cross mapping. Physiol. Meas. 40, 114001 (2019).

Yeh, C.-H., Lo, M.-T. & Hu, K. Spurious cross-frequency amplitude–amplitude coupling in nonstationary, nonlinear signals. Phys. A 454, 143–150 (2016).

Pittman-Polletta, B., Hsieh, W.-H., Kaur, S., Lo, M.-T. & Hu, K. Detecting phase-amplitude coupling with high frequency resolution using adaptive decompositions. J. Neurosci. Methods 226, 15–32 (2014).

Catrambone, V. & Valenza, G. Microstates of the cortical brain-heart axis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 5846–5857 (2023).

Dragomiretskiy, K. & Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 62, 531–544 (2013).

Li, H., Kwong, S., Yang, L., Huang, D. & Xiao, D. Hilbert-Huang transform for analysis of heart rate variability in cardiac health. IEEE-ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 8, 1557–1567 (2011).

Orini, M., Bailón, R., Mainardi, L. T., Laguna, P. & Flandrin, P. Characterization of dynamic interactions between cardiovascular signals by time-frequency coherence. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 59, 663–673 (2011).

Candia-Rivera, D., de Vico Fallani, F. & Chavez, M. Robust and time-resolved estimation of cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic indices. R. Soc. Open Sci. 12, 240750 (2025).

Tort, A. B., Komorowski, R., Eichenbaum, H. & Kopell, N. Measuring phase-amplitude coupling between neuronal oscillations of different frequencies. J. Neurophysiol. 104, 1195–1210 (2010).

Aru, J. et al. Untangling cross-frequency coupling in neuroscience. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 31, 51–61 (2015).

Yeh, C.-H. et al. Cross-frequency coupling and intelligent neuromodulation. Cyborg. Bionic. Syst. 4, 0034 (2023).

Tort, A. B. et al. Dynamic cross-frequency couplings of local field potential oscillations in rat striatum and hippocampus during performance of a T-maze task. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20517–20522 (2008).

Takeuchi, S. et al. Gamma oscillations and their cross-frequency coupling in the primate hippocampus during sleep. Sleep 38, 1085–1091 (2015).

Muthuraman, M. et al. Cross-frequency coupling between gamma oscillations and deep brain stimulation frequency in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 143, 3393–3407 (2020).

Motoi, H. et al. Phase-amplitude coupling between interictal high-frequency activity and slow waves in epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia 59, 1954–1965 (2018).

Hyafil, A., Giraud, A.-L., Fontolan, L. & Gutkin, B. Neural cross-frequency coupling: connecting architectures, mechanisms, and functions. Trends Neurosci. 38, 725–740 (2015).

Fabus, M. S., Sleigh, J. W. & Warnaby, C. E. Effect of propofol on heart rate and its coupling to cortical slow waves in humans. Anesthesiology 140, 62 (2024).

Lechinger, J., Heib, D. P. J., Gruber, W., Schabus, M. & Klimesch, W. Heartbeat-related EEG amplitude and phase modulations from wakefulness to deep sleep: interactions with sleep spindles and slow oscillations. Psychophysiology 52, 1441–1450 (2015).

Faes, L., Marinazzo, D., Jurysta, F. & Nollo, G. Linear and non-linear brain–heart and brain–brain interactions during sleep. Physiol. Meas. 36, 683 (2015).

Dumont, M. et al. Interdependency between heart rate variability and sleep EEG: linear/non-linear?. Clin. Neurophysiol. 115, 2031–2040 (2004).

Candia-Rivera, D., Faes, L., de Vico Fallani, F. & Chavez, M. Measures and Models of Brain-Heart Interactions. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 14, 1–17 (2025).

Zhang, C., Yeh, C.-H. & Shi, W. Variational phase-amplitude coupling characterizes signatures of anterior cortex under emotional processing. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 1935–1945 (2023).

Dang-Vu, T. T. et al. Spontaneous neural activity during human slow wave sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 15160–15165 (2008).

Svanborg, E. & Guilleminault, C. EEG frequency changes during sleep apneas. Sleep 19, 248–254 (1996).

Simon, C. W. & Emmons, W. H. EEG, consciousness, and sleep. Science 124, 1066–1069 (1956).

Hermann, B. et al. Aberrant brain–heart coupling is associated with the severity of post cardiac arrest brain injury. Ann. Clin. Transal. Neurol. 11, 866–882 (2024).

Stein, P. K. & Pu, Y. Heart rate variability, sleep and sleep disorders. Sleep. Med. Rev. 16, 47–66 (2012).

Lyu, J., Shi, W., Zhang, C. & Yeh, C.-H. A novel sleep staging method based on EEG and ECG multimodal features combination. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 4073–4084 (2023).

Kong, S. D. et al. Heart rate variability during slow wave sleep is linked to functional connectivity in the central autonomic network. Brain Commun. 5, fcad129 (2023).

Zoccoli, G. & Amici, R. Sleep and autonomic nervous system. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 15, 128–133 (2020).

Reyes del Paso, G. A., Langewitz, W., Mulder, L. J., Van Roon, A. & Duschek, S. The utility of low frequency heart rate variability as an index of sympathetic cardiac tone: a review with emphasis on a reanalysis of previous studies. Psychophysiology 50, 477–487 (2013).

Lee, H., Park, J., Kim, H. & Lee, K.-J. New rule-based algorithm for real-time detecting sleep apnea and hypopnea events using a nasal pressure signal. J. Med. Syst. 40, 1–12 (2016).

Rolón, R. E. et al. Automatic scoring of apnea and hypopnea events using blood oxygen saturation signals. Biomed. Signal Process. 62, 102062 (2020).

Eckert, D. J. & Malhotra, A. Pathophysiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 5, 144–153 (2008).

De Chazal, P., Heneghan, C. & McNicholas, W. T. Multimodal detection of sleep apnoea using electrocardiogram and oximetry signals. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 367, 369–389 (2009).

Berry, R. B. et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: deliberations of the sleep apnea definitions task force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 8, 597–619 (2012).

Dingli, K. et al. Spectral oscillations of RR intervals in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome patients. Eur. Resp. J. 22, 943–950 (2003).

Dissanayake, H. U. et al. Association between autonomic function and obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 57, 101470 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Interaction effect of obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movements during sleep on heart rate variability. J. Sleep. Res. 28, e12861 (2019).

Candia-Rivera, D. & Cnrs, M. C. In 13th Conference of the European Study Group on Cardiovascular Oscillations https://hal.science/hal-04813786v1/file/2024205034.pdf (ESGCO, 2024).