Abstract

Facial expressions are critical social cues for deciphering others’ emotional states and intentions. While the neural architecture supporting emotional face processing is well established, few studies have examined the developmental trajectory of the underlying oscillatory dynamics. Using magnetoencephalography in a large typically-developing sample (6–17 years-old), we quantified neural oscillations during gender judgments of angry, happy, and neutral faces. Alpha/beta responses to neutral faces increased with age in the posterior superior temporal cortices and decreased in the prefrontal cortex, indicating a shift toward posterior processing. Gamma oscillations increased with age for angry and neutral faces in the temporoparietal junction and fusiform, suggesting enhanced specialization for processing threatening and ambiguous stimuli. Happy faces elicited age-related gamma decreases in attention cortices, implying less attentional demand for positive faces. These findings offer the largest assessment to date of developmental changes in the neural dynamics supporting facial expression processing and mechanisms relevant to emerging psychopathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Facial expressions are important multi-dimensional cues that convey a wealth of information about the emotional states and behavioral intentions of others1,2. The ability to perceive and understand emotions through facial expressions is considered to be evolutionarily essential for guiding interpersonal interactions and behaviors, given their complex social and motivational significance. Building upon the influential framework proposed by Haxby and colleagues, a revised dual face perception model proposes two interactive pathways (i.e., ventral and dorsal; refs. 3,4). The ventral stream is primarily associated with our ability to perceive and distinguish facial expressions through the construction of invariant representations, whereas the dorsal pathway plays a key role in ongoing social interactions by processing rapidly changing aspects of faces, such as expression, gaze, and mouth movement. Neuroimaging studies have also identified face-selective regions along these pathways, including the fusiform gyrus, anterior temporal lobe, anterior and posterior regions of the superior temporal sulcus (STS), lateral occipital cortex (LOC), prefrontal cortex (PFC), and the inferior frontal gyrus5,6,7,8. Among these, the posterior superior temporal sulcus serves as a central hub, integrating form and movement information and projecting to other networks, including limbic and frontoparietal areas9,10. These extended networks function to facilitate social, cognitive, and regulatory processes, such as the evaluation of social feedback, self-regulation, and mentalization9,11,12,13.

The neural architecture supporting face processing is available as early as infancy14,15,16 and continues to develop into adolescence17,18. This protracted developmental trajectory is marked by increased functional connectivity and continued specialization in core and extended face-processing areas19,20,21. Several regions supporting facial expression processing in adults, such as the STS, LOC, and PFC have also been shown to support face processing in early infancy, suggesting the partial activation of most regions of the social brain network from three months onward22,23. Notably, while the PFC is one of the last brain regions to fully mature24,25, it responds early to social stimuli, including emotional faces, underscoring its foundational role in processing social information. Ventromedial regions of the PFC, in particular, have been implicated in social cognitive functions such as mentalizing and self-referential processing, based largely on evidence from adult neuroimaging studies26. Furthermore, through its connections to posterior regions, the PFC helps direct attentional resources and integrate sensory input to help regulate cognitive and emotional responses in both adult27 and pediatric populations28,29. This interaction between social information and attention highlights the PFC’s capacity to prioritize and interpret social cues from the environment, shaping how children learn from and respond to their social experiences.

Facial expressions differ in motivational salience throughout development, contributing to age-related differences in the neural and behavioral processing of happy, angry, and neutral faces. A large body of developmental research demonstrates that an attentional bias toward threatening cues, like angry faces, is normative and emerges early in life30,31,32. Anger conveys goal-directed interpersonal threat and is recognized with above-chance accuracy by children as young as six33, making it developmentally appropriate and socially salient for studies spanning abroad age range. In contrast, happy faces are more easily recognized across all ages, likely due to their familiarity, predictability, and positive valence34,35. Neutral faces, however, are known to pose a challenge for youth to categorize due to their ambiguous nature. In early neuroimaging studies, neutral faces were often used as a control condition to identify the specific neural underpinnings of emotions that were thought to be more arousing (e.g., anger)36,37. However, subsequent studies have shown that neutral faces are not always perceived as emotionally neutral38; they may be seen as cold or threatening due to the expectation of positive social interactions39. Indeed, both children and adults tend to rate neutral faces with negative valence40,41, particularly when presented with other negative faces42. In their motivational relevance framework, Maratos and Pessoa argue that individuals should be motivated to attend to ambiguous stimuli because attention is necessary to determine relevance43. This process of disambiguation may be especially demanding during development, when social-cognitive and regulatory systems are still maturing. Importantly, alterations in the developmental trajectory of these processes have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism), mental health disorders that become increasingly prevalent in adolescence (e.g., anxiety and depression), and adult-onset psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia)42,44,45,46,47. Children’s ability to recognize and understand facial expressions has also been found to predict social success48 and school performance49. Therefore, research on typically developing children is essential as it establishes a baseline for the development of facial expression processing.

While much prior research on emotional face processing has relied on functional MRI (fMRI) and event-related potentials (ERP)29,50,51, these approaches are limited in capturing the full spatiotemporal dynamics of neural activity. Magnetoencephalography (MEG), by contrast, offers a unique combination of millisecond temporal resolution and excellent spatial precision, enabling detailed examination of cortical neural oscillations across spectral bands that are thought to reflect distinct neurocomputational functions. For example, alpha and beta oscillations are commonly linked to top-down processes, including attentional control and inhibition of task-irrelevant information52,53, whereas gamma-band activity is associated with local processing demands and bottom-up prediction error signaling54,55. Developmental changes in oscillatory power are thought to reflect dynamic shifts in cortical excitability, efficiency, and integration of specific computational processes. MEG studies on face processing in children do exist56,57,58, though investigations specifically examining dynamic oscillatory responses to varying emotional expressions remain limited.

In this study, we utilized high-density MEG in a large sample of children and adolescents to investigate the development of oscillatory neural responses across different spectral bands supporting the processing of angry, happy, and neutral facial expressions. We expected age-related alterations in the neural dynamics supporting face processing overall, as well as alterations that vary based on the emotion being processed, given that socio-affective cues are increasingly salient across development as children become more socially motivated, sensitive to peer evaluation, and capable of complex mentalizing59,60. We hypothesized that while fewer neural resources would be required to process happy faces across development, neutral and angry faces would engage stronger neural oscillations and involve more widespread neural representations, as they are more context-dependent. Such stronger neural oscillations may reflect the need to resolve the emotional ambiguity and process the social relevance of these expressions. Specifically, we expected these dynamics to involve a broader network of face-processing areas, including areas involved in emotional interpretation and social cognition.

Results

Demographic and behavioral analyses

Seventeen out of the 186 original participants were excluded due to poor performance, excessively noisy MEG data, or technical issues. The remaining 169 participants (Mage = 10.50 years, SDage = 2.72 years; 93 males; 154 right-handed) included 141 who identified as Caucasian/White, 22 as multiracial, 4 as African American/Black, one as Asian, and one who did not report race. Mean reaction times were 861.79 ms (SD = 161.74 ms) for angry faces, 853.95 ms (SD = 156.08 ms) for happy faces, and 859.88 ms (SD = 160.30) for neutral faces. The average accuracy for the gender of the faces was 92.85% (SD = 5.02%) for angry faces, 93.76% (SD = 4.45%) for happy faces, and 93.14% (SD = 5.47%) for neutral faces. After trimming trials that were 3 SD or more away from the participant’s mean response time, we conducted separate repeated-measures ANCOVAs for the reaction time and accuracy data and found significant effects of age on reaction time (F(1, 163) = 101.80, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.38, 95% CI [0.32, 0.44]) and accuracy (F(1, 162) = 34.20, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.17, 95% CI [0.08, 0.28]; Fig. 1b). We did not observe significant main effects of expression or age-by-expression interaction effects in the behavioral data. All behavioral analyses were completed using SPSS (Version 29).

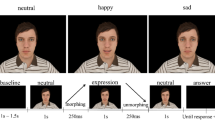

a MEG facial expression viewing task. A total of 169 healthy youth (Mage = 10.50 years, SDage = 2.72 years; 93 males) successfully completed the emotional faces (i.e., angry, happy, neutral) task during MEG. Stimuli were presented on a screen and participants were instructed to respond to the gender of the stimulus. All face stimuli were taken from the RADIATE dataset, with consents from all actors to use their photographs for research and scientific purposes92. b Behavioral performance during the task. Scatterplots with regression lines display the main effects of age on total reaction times (top left) and accuracy (bottom left) across the three facial expression conditions. Violin plots to the right show reaction time (top right) and accuracy (bottom right) data for each condition. Neither the main effect of expression nor the age-by-expression interaction was significant for reaction time or accuracy. n.s. = not significant.

MEG sensor- and source-level analyses

Statistical analysis of time-frequency spectrograms revealed significant alpha/beta (11–20 Hz) and gamma (64–84 Hz) oscillatory responses in sensors near the occipital and parietal cortices across all participants and conditions (all ps < 0.005, corrected). Specifically, we observed a strong decrease in oscillatory power relative to baseline in the alpha/beta frequency range from 150 to 750 ms (Fig. 2a), which was imaged as two non-overlapping time-frequency windows of interest (i.e., early: 150–450, late: 450–750 ms) since the duration of our baseline period was limited to 400 ms (i.e., −400 to 0 ms). Within the gamma frequency band, there was a strong increase in oscillatory power relative to the baseline between 500 to 800 ms (Fig. 2a).

a Time-frequency spectrograms from near the posterior parietal cortex revealed robust changes in alpha/beta (11–20 Hz; early: 150–450 ms; late: 450–750 ms) and gamma (64–84 Hz; 500–800 ms) power relative to the baseline period. Time is shown on the x-axis in (ms) units and frequency (Hz) on the y-axis. The vertical white line represents the onset of the face stimuli at 0 ms. The spectrogram is scaled as a percent change from the baseline, with the color scale bar per spectrogram to the right. b Grand-averaged maps for the functional alpha/beta and gamma windows showing regions exhibiting the strongest responses averaged across all conditions and participants. The color scale bars to the far right show of each column show the units (pseudo-t).

To assess data quality and identify regions exhibiting the strongest oscillatory responses, we grand-averaged the beamformer images across all facial expression conditions and participants, per neural oscillatory response. This revealed robust alpha/beta and gamma oscillatory responses across a broad region of the occipital and posterior temporal cortices, as well as frontal, parietal, and sensorimotor cortical responses in the late alpha/beta and gamma windows (Fig. 2b).

Age-by-facial expression interactions: alpha/beta oscillatory dynamics

The condition-wise functional maps per oscillatory response were examined using whole-brain, voxel-wise, ANCOVAs with facial expression (three levels) and age (continuous) as factors to test for developmental effects in the neural dynamics serving facial expression processing. To assess the direction of all main effects of age and expression and the age-by-expression interaction, we extracted peak values from significant clusters (all ps < 0.005, corrected) and performed post hoc tests. Our whole-brain ANCOVAs on alpha/beta activity revealed age-by-expression interactions in multiple brain regions. In the early alpha/beta window, a significant age-by-expression interaction was found in the right posterior superior temporal cortex (Fig. 3; right pSTC; F(2, 274) = 8.43, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06). Post hoc testing indicated that early alpha/beta oscillatory responses to neutral faces in this region became stronger (i.e., more negative relative to baseline) with increasing age (b = −0.63, 95% CI [−0.91, −0.34], t = −4.30, p < 0.001), and this relationship was significantly different than that of both angry (F(1, 137) = 14.45, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.20]) and happy faces (F(1, 137) = 8.12, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.06, 95% CI [0.01, 0.14]), neither of which exhibited significant relationships with age.

Whole-brain statistical maps showing significant interaction clusters in the early (top) and late (bottom) alpha/beta window. Scatterplots show the associations between age and the strength of neural oscillations in the posterior superior temporal cortex (pSTC) during both time windows (left), as well as in the right anterior prefrontal cortex (PFC) extending ventrally for the late window (right). Pseudo-t values with the number of trials per condition regressed out are displayed on the y-axis and age on the x-axis. Regression lines represent angry (red; A), happy (yellow; H), and neutral faces (green; N). The background colors indicate which facial expressions exhibited a significant relationship between age and neural response strength for each age-by-expression interaction peak. Green backgrounds indicate a significant relationship in the neutral condition, while purple backgrounds indicate a significant relationship between both angry and neutral conditions. Shaded areas around regression lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. To enhance visualization (i.e., data spread), data points that were >3 SD from the mean were excluded from the scatterplots. Note that all data were included in the statistical analyses and that the results remained the same regardless of whether these data points were included or excluded.

This age-by-expression interaction was sustained in the right pSTC during the late alpha/beta window (F(2, 284) = 8.22, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), with neural oscillations to neutral faces again becoming stronger in this region with increasing age (b = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.85, −0.19], t = −3.09, p = 0.002) and this relationship being significantly different compared to both angry (F(1, 142) = 10.63, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.07, 95% CI [0.01, 0.16]) and happy faces (F(1, 142) = 11.90, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]). Notably, no relationships with age were detected for the angry or happy faces during the late alpha/beta windows (ps > 0.05).

In addition, a significant age-by-expression interaction was revealed in the right anterior prefrontal cortex (PFC) extending onto the ventral surface (F(2, 284) = 6.44, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.04) during the late alpha/beta window (Fig. 3). Post hoc analysis revealed that late alpha/beta oscillations became weaker (i.e., less negative relative to baseline) in response to angry (b = 0.51, 95% CI [0.21, 0.81], t = 3.37, p < 0.001) and neutral faces (b = 0.29, 95% CI [0.02, 0.55], t = 2.14, p = 0.03) with increasing age in the right anterior PFC. The association between late alpha/beta responses to happy faces and age significantly differed from that of both angry (F(1, 142) = 11.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]) and neutral faces (F(1, 142) = 4.74, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.03, 95% CI [0, 0.11]). We did not observe any age-related differences between angry and neutral faces (ps > 0.05).

Gamma age-by-facial expression interactions

Age-by-facial expression interactions were also found for gamma oscillations in multiple brain regions (see Fig. 4), including the right posterior parietal cortex (PPC; F(2, 280) = 9.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), the left lateral occipital cortex (LOC; F(2, 280) = 8.47, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), the right temporoparietal junction (TPJ; F(2, 280) = 8.75, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06), the left fusiform gyrus (FG; F(1, 140) = 7.52, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05), the right frontal eye fields (FEF; F(2, 280) = 7.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05), the left parietal cortex (F(2, 280) = 7.02, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.05), and right cerebellum (F(2, 280) = 6.57, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.05).

Whole-brain statistical maps show significant clusters with age-by-expression interaction effects in the gamma window. Scatterplots show the associations between age and the strength of gamma oscillations in the right cerebellum, left parietal cortex, left lateral occipital cortex (LOC), right temporoparietal junction (TPJ), left fusiform gyrus (FG), right frontal eye fields (FEF), and right posterior parietal cortex (PPC). Pseudo-t values with the number of trials per condition regressed out are displayed on the y-axes, with age shown on the x-axes. Scatterplot colors are consistent with Fig. 3. Regression lines represent angry faces (red; A), happy faces (yellow; H), and neutral faces (green; N). The background colors indicate which facial expressions exhibited a significant relationship between age and neural activity for each age-by-expression interaction peak. Green backgrounds indicate a significant relationship in the neutral condition, while red backgrounds indicate a significant relationship in the angry condition. Blue backgrounds indicate a significant relationship between both angry and happy conditions, while purple backgrounds indicate a significant relationship between both angry and neutral conditions. Shaded areas around regression lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. To enhance visualization (i.e., data spread), data points that were >3 SD from the mean were excluded from the scatterplots. Note that all data were included in the statistical analyses and that the results remained the same regardless of including/excluding these data points.

In the right PPC, gamma oscillations became stronger (i.e., more positive) with increasing age during angry face processing (b = 0.29, 95% CI [0.12, 0.46], t = 3.32, p = 0.001), weaker with increasing age during happy faces (b = −0.24, 95% CI [−0.42, −0.06], t = −2.69, p = 0.008), and there was no relationship with age during neutral face processing (p > 0.05). These relationships between age and gamma oscillations in the right PPC significantly differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 24.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.15, 95% CI [0.06, 0.26]), angry and neutral faces (F(1, 140) = 5.01, p = 0.03, ηp2 = 0.04, 95% CI [0, 0.11]), and happy and neutral faces (F(1, 140) = 6.02, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.04, 95% CI [0.001, 0.12]). A similar pattern of results was found in the right FEF, with gamma power becoming stronger with increasing age for angry faces (b = 0.27, 95% CI [0.07, 0.47], t = 2.64, p = 0.009), decreasing with age for happy faces (b = −0.19, 95% CI [−0.37, −0.001], t = -1.99, p = 0.049), and no age-related changes for neutral faces (ps > 0.05). The association between gamma oscillations and age in the right FEF significantly differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 14.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.20]) and neutral and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 3.90, p = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.03, 95% CI [0, 0.10]), but not between angry and neutral faces (p > 0.05).

In contrast, in the right TPJ, age-related increases in gamma oscillatory power were found during angry (b = 0.31, 95% CI [0.13, 0.48], t = 3.46, p < 0.001) and neutral face processing (b = 0.21, 95% CI [0.01, 0.05], t = 2.52, p = 0.013), with no significant changes for happy faces (p > 0.05). The relationship between age and gamma power in the right TPJ differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 13.43, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18]) and between neutral and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 9.10, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.06, 95% CI [0.01, 0.15]), but not between angry and neutral faces (p > 0.05). Gamma responses in the left FG followed the same pattern, increasing with age during angry (b = 0.31, 95% CI [0.12, 0.51], t = 3.20, p = 0.002) and neutral faces (b = 0.25, 95% CI [0.06, 0.45], t = 2.61, p = 0.01), with no age-related changes when viewing happy faces. The relationship between age and gamma power differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 11.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]) and neutral and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 9.80, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.07, 95% CI [0.01, 0,16]), but not between angry and neutral faces (p > 0.05).

In the left parietal cortex, gamma oscillatory power increased with age during neutral face processing (b = 0.25, 95% CI [0.08, 0.42], t = 2.95, p = 0.004), with no relationship for angry or happy faces (ps > 0.05). The association between age and gamma activity in left parietal cortex significantly differed between happy and angry faces (F(1, 140) = 8.34, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.06, 95% CI [0.01, 0.14]) and between happy and neutral faces (F(1, 140) = 11.70, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.17]), but not between angry and neutral faces (p > 0.05). This overall pattern was also observed in the right cerebellum, with increases in gamma oscillatory power with age during neutral faces (b = 0.28, 95% CI [0.08, 0.47], t = 2.80, p = 0.006) and no relationship for angry or happy faces (p > 0.05). Likewise, the relationship between age and gamma power significantly differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 5.98, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.04, 95% CI [0.001, 0.12]) and neutral and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 12.41, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18]), but not angry and neutral faces (p > 0.05).

Lastly, in the left LOC, gamma power increased with age for angry faces (b = 0.27, 95% CI [0.03, 0.51], t = 2.23, p = 0.03), but not for happy and neutral faces (ps > 0.05). This relationship between age and gamma power significantly differed between angry and happy faces (F(1, 140) = 18.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.12, 95% CI [0.03, 0.22]) and angry and neutral faces (F(1, 140) = 5.90, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.04, 95% CI [0.001, 0.12]), but not between happy and neutral faces (p > 0.05).

Main effects of age

During the early window, stronger alpha/beta oscillatory responses (i.e., more negative relative to baseline) with increasing age were observed in the left sensorimotor cortex (F(1, 137) = 36.72, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 2.11, 95% CI [0.10, 0.32]), right motor cortex (F(1, 137) = 11.87, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.01, 0.18]), and right somatosensory cortex (F(1, 137) = 14.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.10, 95% CI [0.02, 0.19]), likely reflecting motor planning related responses for the task. In the late window, stronger alpha/beta oscillations with increasing age were sustained in the left (Fig. 5; F(1, 142) = 17.94, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.11, 95% CI [0.03, 0.21]) and right sensorimotor cortices (F(1, 142) = 23.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14, 95% CI [0.05, 0.25]), and emerged in the right cerebellum (F(1, 142) = 21.16, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.13, 95% CI [0.04, 0.23]). In contrast, alpha/beta oscillations in the left dorsomedial PFC became significantly weaker with increasing age (F(1, 142) = 22.28, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14, 95% CI [0.05, 0.24]). Lastly, significant age-related increases in gamma power were identified in the left TPJ (Fig. 6; F(1, 140) = 29.29, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.17, 95% CI [0.07, 0.28]) and left anterior superior temporal cortex (aSTC; F(1, 140) = 12.31, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.08, 95% CI [0.02, 0.18]), as well as several other regions that overlapped with the interaction effects and thus are not reported here.

(middle): Whole-brain statistical maps showing the significant main effects of age in the late alpha/beta window. Scatterplots display the associations between age and the strength of neural oscillations at the peak voxel in the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC; top left), left sensorimotor cortex (bottom left), right sensorimotor cortex (top right), and right cerebellum (bottom right) collapsed across the three expressions. Pseudo-t values with the number of trials per condition regressed out are displayed on the y-axis and age in years on the x-axis. Shaded areas around regression lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. To enhance visualization (i.e., data spread), data points that were >3 SD from the mean were excluded from the scatterplots. Note that all data were included in the statistical analyses and that the results remained the same regardless of including/excluding these data.

(middle): Whole-brain statistical map showing the significant main effects of age in the gamma window. Scatterplots display the associations between age and neural oscillatory strength in the left anterior superior temporal cortex (aSTC; left) and the left temporoparietal junction (TPJ; right) collapsed across the three expressions. Pseudo-t values with the number of trials per condition regressed out are displayed on the y-axis and age on the x-axis. Shaded areas around regression lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. To enhance visualization (i.e., data spread), data points that were >3 SD from the mean were excluded from the scatterplots. Note that all data were included in the statistical analyses and that the results remained the same regardless of including/excluding these data.

Main effects of facial expression

Significant main effects of expression were found for early and late alpha/beta oscillations, but these spatially overlapped almost entirely with the interaction effects and thus were not interpreted. Likewise, main effects of expression were found for gamma oscillations across multiple brain regions, including the right anterior PFC, right cerebellum, and other cortical regions, but again these clusters strongly overlapped with the interaction effects shown in Fig. 4 and thus were not further examined.

Discussion

This study examined developmental changes in the neural oscillatory dynamics underlying the processing of emotional facial expressions, including angry, happy, and neutral faces. Behaviorally, the participants were faster and more accurate in identifying gender with increasing age, which was not surprising. We did not observe any interactions with facial expression. Given the implicit nature of the gender judgment task and the age of our participants, these behavioral results likely reflect general age-related improvements in reacting to stimuli rather than emotion-specific processes, which were less explicitly taxed by this task35,61. The neural results revealed neurodevelopmental changes across a distributed network of visuoperceptual and attention-related regions in both dorsal and ventral perceptual processing streams, with emotion-dependent modulation across an extended age window critical for the refinement of social processing. While some brain regions exhibited broad age-related shifts in emotional expression processing, others showed narrower developmental changes specific to a single emotional expression, suggesting regional and expression specificity. Importantly, these developmental effects had distinct spectral signatures (e.g., alpha/beta or gamma) in different brain regions, likely reflecting different mechanisms, with changes in gamma-band activity reflecting refinement of bottom-up sensory precision and prediction error signaling, whereas alpha/beta-band changes likely indexing shifts in top-down control and attention regulation. Taken together, these findings extend the field’s understanding of emotional face perception, highlighting developmental effects in key brain regions for social cognition, attention, and related functions that undergo significant specialization during childhood and adolescence for face and emotion expression processing4,11.

We identified a distributed network of brain areas exhibiting age-by-expression interactions in the gamma range, reflecting developmental shifts in attention, sensorimotor integration, and socio-emotional processing. Notably, the right PPC and right FEF, critical nodes of the dorsal attention network, exhibited opposing age-related trajectories in neural responses to angry and happy faces. The PPC helps integrate top-down goals with bottom-up sensory input to guide spatial attention and salience mapping62, whereas the FEF is known to be essential for oculomotor control and voluntary attentional orienting toward motivationally salient stimuli63. As children mature, angry expressions may elicit increased sensorimotor and attentional resources to support rapid behavioral responses to salient threats43. The stronger gamma oscillations with increasing age in the right PPC and FEF during angry face processing largely supports this interpretation and aligns with predictive coding models, in which gamma activity is posited to reflect bottom-up signaling of local prediction errors54,55,64. Conversely, the age-related decrease in gamma to happy faces may reflect reduced top-down attention needs, likely because these expressions become more familiar and predictable over time, consistent with developmental tuning of attention and reward systems34,52,65.

In addition, we found that neural populations in the left FG and right TPJ exhibited increased gamma power with increasing age during both angry and neutral face processing, but not during happy face trials. The stronger gamma oscillations for threat-related (angry) and contextually ambiguous (neutral) faces in the FG, a core region in the face-processing network, is consistent with its role in extracting fine-grained visual facial features4 and interacting with extended networks for emotional evaluation2. Prior work in adults using intracranial recordings has shown that gamma oscillations in the FG are associated with the integration of detailed facial features necessary for recognizing expressions and identities66, supporting the idea that gamma activity reflects the perceptual precision required for decoding socially salient cues. Our developmental findings extend this work by showing age-related gamma increases in FG, suggesting that the underlying neural computations involved in decoding complex social signals become more finely tuned and/or less reliant on attention signals across development. Similarly, the TPJ, a region critical for social perception and attentional reorienting67,68 may facilitate threat detection by directing attention toward socially salient cues that demand rapid behavioral responses. Stronger gamma oscillations in the TPJ, especially during neutral faces, may support context-sensitive inference when emotional signals are ambiguous, and likely reflect increasing integration of sensory input with social-contextual experiences68,69. These findings may suggest a dynamic interplay between the FG and TPJ within the core and extended face-processing networks, with the FG refining visual feature extraction and the TPJ guiding attentional and contextual evaluation. The selective increase in gamma oscillations for angry and neutral, but not happy, faces may also suggest that heightened bottom-up prediction error signaling with visual input deviates from internally generated expectations, again supporting predictive coding frameworks54,64.

Neutral faces were also associated with age-related increases in the strength of gamma oscillations within the left parietal cortex and the right cerebellum. These increases may reflect enhanced sensorimotor simulation and embodied interpretation of ambiguous facial cues, processes thought to require precise multisensory integration and error resolution during development70,71. Similarly, angry faces elicited stronger gamma oscillations with increasing age in the left LOC, possibly reflecting greater reliance on bottom-up perceptual systems and less attentional involvement in extracting threat-related visual information as these systems mature. Collectively, these gamma-band findings suggest that with age, children engage perceptual circuits more robustly for processing complex or ambiguous social cues, in line with predictive coding models and developmental refinement of excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance, which is a core mechanism shaping gamma oscillatory dynamics72,73.

Beyond gamma, our findings revealed significant age-by-expression interaction effects in neural alpha/beta oscillations. Across both early and late alpha/beta time windows, the right pSTC exhibited a sustained oscillatory response (i.e., decrease in power relative to baseline) that became stronger with increasing age exclusively for neutral faces. Unlike angry or happy faces, neutral faces generally lack clear emotional cues, making them more challenging to interpret, particularly in a developmental context where social cognition is still maturing38,40,43. This progressive increase in alpha/beta oscillations within the pSTC, a hub for decoding dynamic social cues such as gaze shifts and subtle expression changes10,74, may reflect heightened sensitivity to motivationally relevant ambiguous cues41, with youth increasingly drawing on these posterior temporal resources to resolve uncertainty and perform greater integration of social context as cognitive and affective systems mature. Concurrently, oscillatory responses in the right anterior PFC extending onto the ventral surface became weaker with age (i.e., less negative relative to baseline) during the late alpha/beta window for both neutral and angry faces. This area of the PFC undergoes protracted maturation into early adulthood and is critical for evaluating the motivational relevance and affective salience of social cues, in part through its connectivity with extended face-processing networks involved in emotional appraisal and self-referential processing. The weaker alpha/beta oscillations in this area may reflect decreased reliance on top-down regulatory control as facial expression perception becomes more automatic and perceptually grounded19. Essentially, young children may rely more heavily on the anterior/ventral PFC to regulate and interpret angry face processing, as potential threats or socially salient signals often necessitate more self-referential evaluation75,76, while older youth may increasingly leverage posterior systems that support more efficient and stimulus-driven processing, possibly due to accumulated social experience or regulation maturation77,78. This interpretation aligns with the view that the gender judgment task still requires participants to regulate attention and suppress distractions arising from emotionally salient facial expressions, particularly in younger participants with the maturing frontoparietal control networks79,80,81.

Beyond the interaction effects, our findings also revealed broader age-related patterns of change in emotional face processing across both spectral bands. In the gamma band, social cognition hubs like the left TPJ showed developmental specialization, suggesting a shift from basic visual recognition to socially contextualized processing. Gamma oscillations in the left aSTC also became stronger with age, consistent with a role in the dorsal face-processing pathway for dynamic social cue analysis and complementing fMRI evidence implicating anterior temporal regions in emotional face processing3. Alpha/beta oscillations in motor and cerebellar cortices increased with age, likely reflecting maturation of task-related sensorimotor networks serving the behavioral motor response82,83,84. Lastly, developmental weakening of alpha/beta oscillations in the dmPFC mirror the anterior/ventral PFC effects described above. Together, these findings may suggest a developmental shift from effortful, distributed regulation involving frontal hubs to more specialized posterior networks that can more efficiently encode and interpret facial signals, consistent with the broader developmental maturation of frontoparietal control networks that support goal-directed attention in the face of emotional distraction81,85. Although not examined here, the concurrent developmental changes observed in frontal alpha/beta and posterior gamma activity raise the possibility of coordinated interactions between these signals, such as through dynamic coupling and/or cross-frequency coding, which could provide a mechanistic link between regulatory and perceptual systems.

While these findings are exciting and add to the field’s understanding of the developmental trajectory of emotional face processing, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our multimodal neuroimaging approach, combining the high temporal resolution of MEG with anatomical MRI, allows us to identify age-related changes in neural oscillations, but the cross-sectional design limits our ability to infer how these processes unfold over time within individuals. Longitudinal studies avoid this limitation and are needed to more precisely map individual developmental trajectories and establish a normative range of variability. Second, while our implicit task was appropriate for a wide age range and effectively elicited developmental changes in behavior and neural activity, it may not fully capture higher-order processes involved in explicit emotion recognition or social decision-making. Future research would benefit from incorporating both implicit and explicit paradigms to improve ecological validity and clarify how task demands influence developmental trajectories of emotional processing. Third, although MEG provides excellent temporal resolution, its limited sensitivity to deep brain structures should be acknowledged86. Fourth, although beyond the scope of the current study, our findings of concurrent age-related changes in frontal alpha/beta and posterior gamma oscillations highlight the potential of future interregional and/or cross-frequency coupling analyses to probe mechanisms of frontal–posterior communication during emotion processing. As developmental increases in resting-state alpha frequency have been well documented87,88, incorporating individual alpha frequency estimates in future task-based studies may also improve the precision of oscillatory analyses across development. Fifth, given its well-documented role in shaping higher-order cortices subserving social-emotional processing89,90, variability in pubertal development and associated hormonal changes, which were not directly investigated in this study, could influence the observed neurological and behavioral differences in our sample. Finally, our study focused on three static facial expressions. Expanding to include dynamic or socially complex expressions, as well as examining individual differences (e.g., anxiety traits), would help capture the full heterogeneity in emotional processing during development. Addressing these gaps in future studies may further enhance our understanding of the subtle mechanisms underlying changes in the development of emotional face processing.

Taken together, our findings support established face perception models3,91, revealing sophisticated and distinct developmental trajectories underlying the processing of emotional facial expressions, with notable differences across expressions (angry, happy, neutral) and spectral bands (alpha/beta and gamma). Overall, we found that gamma oscillations appear to track the refinement of perceptual prediction and encoding for socially salient inputs, while the strength of alpha/beta oscillations reflect developmental changes in top-down attentional and regulatory mechanisms. These distinct and complementary developmental trajectories of alpha/beta and gamma oscillations help highlight MEG’s strength in disentangling the spectral dynamics underlying social cognition across childhood and adolescence. As children mature, neural responses to emotionally salient angry faces increase across distributed brain regions, particularly in dorsal attention (PPC/FEF), visual salience (occipital cortex), and social cognition (PFC/TPJ) networks, suggesting the prioritization of threat-related stimuli for faster interpretation and potential action preparation. Neutral faces, in contrast, due to their ambiguous nature, engage regions like the right TPJ, core face-processing areas (pSTC/FG), and sensorimotor regions (parietal cortex/cerebellum), reflecting deeper processing and interpretation and context-dependencies in resolving uncertainty (i.e., motivational relevance theory). Happy faces elicited reduced gamma oscillations in the dorsal attention (PPC/FEF) areas, reflecting automatized processing of rewarding stimuli with increasing age. These findings are consistent with our hypothesis that happy faces require fewer cognitive resources, while angry and neutral faces require more extensive neural involvement due to their emotionally salient or ambiguous nature. Given the significant socio-affective face processing differences observed across multiple mental health disorders in youth, it is critical to establish a baseline for identifying altered neural signatures in future clinical investigations.

Methods

Participants

A total of 186 healthy children and adolescents (rangeage: 6 to 17 years; Mage = 10.46 years, SDage = 2.77 years; 102 males; 167 right-handed) were enrolled in this study. All were recruited from the greater Omaha metropolitan area as part of the Developmental Multimodal Imaging of Neurocognitive Dynamics (DevMIND) study (R01-MH121101). Of the 186 participants, 155 identified as Caucasian, 24 as multiracial, 5 as African American, one as Asian, and one did not report their race. Across all races, 8 identified as Hispanic. This distribution corresponds closely to the racial/ethnic demographics of the greater Omaha metropolitan area. Exclusionary criteria included a diagnosis of neurological or psychiatric disorders, history of head trauma, and current substance use, as well as the standard exclusion criteria (e.g., ferromagnetic implants) for MEG/MRI studies. Informed assent and consent were obtained from the participants and their guardians, respectively, following a comprehensive description of the study. The Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this investigation. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

MEG experimental paradigm

All participants completed a facial expression viewing task while seated in the MEG. Stimuli consisted of facial expressions from 40 different adult actors (aged 18–30 years), balanced by sex (20 male, 20 female) and race/ethnicity (Caucasian, African American, Asian, and Hispanic), taken from the RADIATE face stimulus dataset92. Consents were obtained from all actors to use their photographs for research and scientific purposes92. The experiment consisted of 240 trials, which were equally split and pseudo-randomized by the sex of the actor (120 trials for each sex) and by three facial expressions (neutral, angry, and happy; 80 trials for each condition). For each trial, a face was presented at 0 ms and remained on screen for 1500 ms. Participants were instructed to fixate on a central crosshair and use their right hand to respond whether the stimulus was male or female as quickly and accurately as possible, using an index or middle finger button press, regardless of the facial expression (Fig. 1a). After the face disappeared at 1500 ms, the screen remained white with a centrally located black crosshair for 1600 ± 100 ms before the next trial began. The total task time was approximately 13 min and was programmed in Matlab (Mathworks, Inc., Massachusetts, USA) using the Psychophysics Toolbox Version 393 and presented using a PROPixx DLP projector (VPixx Technologies, Saint Bruno, Canada).

MEG data acquisition

All MEG recordings were conducted in a two-layer VACOSHIELD magnetically shielded room (Vacuumschmelze, Hanau, Germany). Participants were seated in a non-magnetic chair, with their head positioned within the sensor array. A 306-sensor MEGIN Neo MEG system (Helsinki, Finland) equipped with 204 planar gradiometers and 102 magnetometers was used to sample neuromagnetic responses continuously at 1 kHz with an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1–330 Hz. Participants were monitored by a real-time audio-video feed from inside the shielded room throughout the recording. Each participant’s data were individually corrected for head movement and noise reduced using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension94,95. Our analyses were based on the 204 planar gradiometer data.

MRI acquisition and MEG-MRI coregistration

Prior to MEG measurement, five head-position indicator (HPI) coils were attached to the participant’s head and localized with three fiducial points and the scalp surface using a 3-D digitizer (FASTRAK, Polhemus Navigator Sciences, Colchester, VT, USA). Once the participant was positioned for MEG recording, an electric current with a unique frequency label (e.g., 322 Hz) was fed to each of the coils. This induced a measurable magnetic field and allowed each coil to be localized in reference to the sensors throughout the recording session. Since coil locations were also known in head coordinates, all MEG measurements could be transformed into a common coordinate system. With this coordinate system, each participant’s movement-corrected MEG data was co-registered with their structural MRI data prior to source space analyses using the Brain Electrical Source Analysis (BESA) MRI software (Version 3.0; BESA GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany). High-resolution T1-weighted structural MRI data were acquired using a 3 T Siemens Prisma magnet with a 32-channel head coil and the following parameters: TR: 2400 ms; TE: 2.05 ms; field of view: 256 mm; matrix: 256 × 256; slice thickness: 1 mm with no gap; voxel size: 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm; acquisition plane: sagittal; flip angle: 8 degrees. These anatomical images were aligned parallel to the anterior/posterior commissures and transformed into standard space. Following source analysis (i.e., beamforming), each participant’s 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm MEG functional images were also transformed into standardized space using the transform that was previously applied to the structural MRI volume and spatially resampled.

MEG data preprocessing

The continuous magnetic time series was divided into 3000 ms epochs (−1500, 1500), with a baseline period of –400 to 0 ms. Cardiac and eyeblink artifacts were removed using signal-space projection (SSP)96. Notch filters were set at 60 Hz to minimize contributions from the North American power main frequency. Epochs with remaining artifacts were rejected per participant using a fixed threshold method, supplemented with visual inspection. Specifically, the amplitude and gradient distributions were computed across all trials per participant to account for variance related to differences in head size, differences in the distances between the brain and the MEG sensor array, and other person-specific factors that can have a major impact on the overall signal amplitude across all trials. Using these individual distributions, thresholds were set to reject trials with the highest amplitude and/or gradient values per participant. Following artifact rejection, participants with lower than 60% accepted trials were excluded and an average of 200.51 trials (SD = 16.15, min = 144, max = 228) per participant were available for final analyses. To ensure the number of trials per condition was equal across the sample, we conducted a repeated-measures ANCOVA analysis to examine the effect of expressions, the effect of age, and age-by-expression interaction. The results indicated that the effect of facial expression and the age-by-expression interaction were not significant (ps > 0.05), but that the effect of age was significant (F (1, 165) = 30.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14), revealing that older participants tended to have more accepted trials than younger participants. Since the number of trials can affect the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and thus bias developmental effects, we covaried out the square root of the number of trials per person in all functional mapping analyses97. This helped mitigate the impact of SNR differences in developmental changes in the amplitude of neural responses (see “MEG source imaging and statistics”). All MEG pre-processing steps completed using the BESA Research (Version 7.1) software.

Sensor level statistics

The remaining artifact-free epochs were transformed into the time-frequency domain using complex demodulation with a time-frequency resolution of 1 Hz 50 ms98. The resulting spectral power estimates per sensor were averaged across trials to generate time-frequency plots of mean spectral density, and these sensor-level data were then normalized by the baseline power per frequency bin during the –400 to 0 ms window. The time-frequency windows used for beamforming analysis were identified using a data-driven approach that involved statistical analyses of the sensor-level spectrograms across the array of gradiometers using the BESA Statistical software (Version 2.1; BESA GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany). Specifically, to minimize false-positive results, paired-sample t-tests against baseline were performed per spectrogram pixel per sensor at stage one to identify potentially significant pixels (p < 0.05) across the array. In stage two, the pixels that survived the threshold were clustered with temporally, spectrally, and/or spatially neighboring pixels that were also above the (p < 0.05) threshold and a cluster value was derived by summing all the t-values of all data points in the cluster. Nonparametric permutation testing was then used to derive a distribution of cluster values, and the significance level of the observed clusters (from stage 1) was tested directly using this distribution99,100. For each comparison, 10,000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values. By applying this data-driven method, we were able to focus our beamforming analyses on the time-frequency windows containing significant oscillatory events relative to baseline across all participants and facial expression conditions.

MEG source imaging and statistics

Using the time-frequency windows identified through the sensor-level analysis, cortical oscillatory responses were imaged using the dynamic imaging of coherent sources (DICS) beamformer101,102, which uses the sensor-level cross-spectral densities to calculate voxel-wise estimates of neural power. Each task condition (i.e., emotional expression) was imaged separately per participant. Following convention, the source power in these images was normalized per participant using a pre-stimulus period (i.e., baseline) of equal duration and bandwidth103. Such images are typically referred to as pseudo-t maps, with units (pseudo-t) that reflect noise-normalized power differences (i.e., active vs. baseline) per voxel. This approach generated three-dimensional, participant-level pseudo-t maps per emotional face condition (i.e., angry, happy, neutral faces) for each time-frequency cluster identified in the sensor-level analysis. MEG imaging used the BESA Research (Version 7.1) software.

Statistics and reproducibility

To investigate potential developmental differences in neural oscillatory responses during emotional face processing, we first obtained whole-brain residual maps by regressing the number of accepted trials as a covariate of no interest to control for any SNR differences related to this parameter97. To assess data quality and the origins of the strongest contributors to each significant oscillatory response identified at the sensor level, the facial expression maps were first averaged together for each participant, per time-frequency component, and then grand-averaged across all participants. For our primary analyses, we conducted a whole-brain ANCOVAs with the three facial expressions (i.e., happy, angry, neutral) as within-subject factors and age as a covariate of interest in R Studio (Version 4.4.0). To account for multiple comparisons, we implemented a stringent two-tailed p-value threshold of 0.005 and a cluster threshold (k-threshold) minimum of 8 contiguous voxels (i.e., >500 mm3). Pseudo-t values were extracted from the peak voxel of each significant cluster from the whole-brain residual maps and subjected to post hoc testing in SPSS (Version 29) to examine directionality and origin of observed main effects of age, main effects of facial expression, and age-by-expression interactions.

Inclusion & ethics

All collaborators of this study have fulfilled the criteria for authorship required by Nature Portfolio journals and been included as authors, and their contributions were essential for the design and implementation of the study. Roles and responsibilities were agreed among collaborators ahead of the research. This research was not severely restricted or prohibited in the setting of the researchers, and does not result in stigmatization, incrimination, discrimination or personal risk to participants. Local and regional research relevant to our study was considered in citations.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The numerical source data for graphs has been provided in Supplementary Data 1. De-identified MEG and MRI data are publicly available via the Collaborative Informatics and Neuroimaging Suite (COINS; https://coins.trendscenter.org/) upon request.

Code availability

The MEG and MRI analyses reported herein utilized the Brain Electrical Source Analysis software (BESA Research: version 7.1; BESA MRI: version 3.0; BESA Statistics: version 2.1). We also used R studio version 4.4.0 and IBM SPSS version 29 for statistical analyses. Any requests for code or batch functions used in these analyses are available upon request.

References

Izard, C. E. Facial expressions and the regulation of emotions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 58, 487–498 (1990).

Vuilleumier, P. & Pourtois, G. Distributed and interactive brain mechanisms during emotion face perception: evidence from functional neuroimaging. Neuropsychologia 45, 174–194 (2007).

Duchaine, B. & Yovel, G. A revised neural framework for face processing. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 1, 393–416 (2015).

Haxby, J. V., Hoffman, E. A. & Gobbini, M. I. The distributed human neural system for face perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 223–233 (2000).

Axelrod, V. & Yovel, G. The challenge of localizing the anterior temporal face area: a possible solution. NeuroImage 81, 371–380 (2013).

Dubois, J., de Berker, A. O. & Tsao, D. Y. Single-unit recordings in the macaque face patch system reveal limitations of fMRI MVPA. J. Neurosci. 35, 2791–2802 (2015).

Nasr, S. & Tootell, R. B. Role of fusiform and anterior temporal cortical areas in facial recognition. Neuroimage 63, 1743–1753 (2012).

Pinsk, M. A. et al. Neural representations of faces and body parts in macaque and human cortex: a comparative fMRI study. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 2581–2600 (2009).

Adolphs, R. Investigating the cognitive neuroscience of social behavior. Neuropsychologia 41, 119–126 (2003).

Allison, T., Puce, A. & McCarthy, G. Social perception from visual cues: role of the STS region. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 267–278 (2000).

Blair, R. J. R., Morris, J. S., Frith, C. D., Perrett, D. I. & Dolan, R. J. Dissociable neural responses to facial expressions of sadness and anger. Brain 122, 883–893 (1999).

Ochsner, K. et al. For better or for worse: neural systems supporting the cognitive down- and up-regulation of negative emotion. NeuroImage 23, 483–499 (2004).

Takahashi, H. K. et al. Brain networks of affective mentalizing revealed by the tear effect: the integrative role of the medial prefrontal cortex and precuneus. Neurosci. Res. 101, 32–43 (2015).

Johnson, M. H., Dziurawiec, S., Ellis, H. & Morton, J. Newborns’ preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition 40, 1–19 (1991).

Maurer, D. & Young, R. E. Newborn’s following of natural and distorted arrangements of facial features. Infant Behav. Dev. 6, 127–131 (1983).

Scott, L. S. & Arcaro, M. J. A domain-relevant framework for the development of face processing. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2, 183–195 (2023).

Diamond, R. & Carey, S. Developmental changes in the representation of faces. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 23, 1–22 (1977).

Wu, M. et al. Age-related changes in amygdala–frontal connectivity during emotional face processing from childhood into young adulthood. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 1684–1695 (2016).

Cohen Kadosh, K., Cohen Kadosh, R., Dick, F. & Johnson, M. H. Developmental changes in effective connectivity in the emerging core face network. Cereb. Cortex 21, 1389–1394 (2011).

Joseph, J. E. et al. The changing landscape of functional brain networks for face processing in typical development. NeuroImage 63, 1223–1236 (2012).

Song, Y., Zhu, Q., Li, J., Wang, X. & Liu, J. Typical and atypical development of functional connectivity in the face network. J. Neurosci. 35, 14624–14635 (2015).

Grossmann, T. & Johnson, M. H. The development of the social brain in human infancy. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 909–919 (2007).

Lobaugh, N. J., Gibson, E. & Taylor, M. J. Children recruit distinct neural systems for implicit emotional face processing. NeuroReport 17, 215–219 (2006).

Kolb, B., Wilson, B. & Taylor, L. Developmental changes in the recognition and comprehension of facial expression: Implications for frontal lobe function. Brain Cogn. 20, 74–84 (1992).

Nelson, E. E. & Guyer, A. E. The development of the ventral prefrontal cortex and social flexibility. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 1, 233–245 (2011).

Mitchell, J. P., Banaji, M. R. & Macrae, C. N. The link between social cognition and self-referential thought in the medial prefrontal cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 17, 1306–1315 (2005).

Berboth, S. & Morawetz, C. Amygdala-prefrontal connectivity during emotion regulation: a meta-analysis of psychophysiological interactions. Neuropsychologia 153, 107767 (2021).

Keil, V. et al. Children with social anxiety disorder show blunted pupillary reactivity and altered eye contact processing in response to emotional faces: Insights from pupillometry and eye movements. J. Anxiety Disord. 58, 61–69 (2018).

MacNamara, A. et al. Age-related changes in emotional face processing across childhood and into young adulthood: evidence from event-related potentials. Dev. Psychobiol. 58, 27–38 (2016).

LoBue, V. More than just another face in the crowd: Superior detection of threatening facial expressions in children and adults. Dev. Sci. 12, 305–313 (2009).

Dodd, H. F. et al. Trajectories of anxiety when children start school: The role of behavioral inhibition and attention bias to angry and happy faces. J. Abnorm Psychol. 129, 701–712 (2020).

Pérez-Edgar, K. et al. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion 10, 349–357 (2010).

Lawrence, K., Campbell, R. & Skuse, D. Age, gender, and puberty influence the development of facial emotion recognition. Front Psychol. 6, 761 (2015).

Adolphs, R., Damasio, H., Tranel, D. & Damasio, A. R. Cortical systems for the recognition of emotion in facial expressions. J. Neurosci. 16, 7678–7687 (1996).

Gao, X. & Maurer, D. A happy story: developmental changes in children’s sensitivity to facial expressions of varying intensities. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 107, 67–86 (2010).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Functional atlas of emotional faces processing: a voxel-based meta-analysis of 105 functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 34, 418–432 (2009).

Pessoa, L., McKenna, M., Gutierrez, E. & Ungerleider, L. G. Neural processing of emotional faces requires attention. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 11458–11463 (2002).

Lee, E., Kang, J. I., Park, I. H., Kim, J.-J. & An, S. K. Is a neutral face really evaluated as being emotionally neutral?. Psychiatry Res. 157, 77–85 (2008).

Phillips, M. L. et al. Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. NeuroImage 21, 1484–1496 (2004).

Rollins, L., Bertero, E. & Hunter, L. Developmental differences in the visual processing of emotionally ambiguous neutral faces based on perceived valence. PLoS ONE 16, e0256109 (2021).

Tottenham, N., Phuong, J., Flannery, J., Gabard-Durnam, L. & Goff, B. A negativity bias for ambiguous facial-expression valence during childhood: converging evidence from behavior and facial corrugator muscle responses. Emotion 13, 92–103 (2013).

Herba, C. M. & Phillips, M. L. Annotation: development of facial expression recognition from childhood to adolescence: behavioural and neurological perspectives. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 45, 1185–1198 (2004).

Maratos, F. A. & Pessoa, L. What drives prioritized visual processing? A motivational relevance account. Prog. Brain Res. 247, 111–148 (2019).

Doucet, G. E. et al. Anxiety symptoms are differentially associated with facial expression processing in boys and girls. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 19, nsae085 (2024).

Green, M. F., Kern, R. S., Robertson, M. J., Sergi, M. J. & Kee, K. S. In Cognition in Schizophrenia (eds Sharma, T. & Harvey, P.) Vol. 92, 178–192 (Oxford University Press, 2000).

Leung, R. C., Pang, E. W., Brian, J. A. & Taylor, M. J. Happy and angry faces elicit atypical neural activation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Biol. Psychiatry.: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 1021–1030 (2019).

Phillips, M. L., Drevets, W. C., Rauch, S. L. & Lane, R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 515–528 (2003).

Miller, L. D., Martinez, Y. J., Shumka, E. & Baker, H. Multiple informant agreement of child, parent, and teacher ratings of child anxiety within community samples. Can. J. Psychiatry 59, 34–39 (2014).

Agnoli, S. et al. The interaction between emotional intelligence and cognitive ability in predicting scholastic performance in school-aged children. Personal. Individ. Diff. 53, 660–665 (2012).

de Haan, M., Johnson, M. H. & Halit, H. Development of face-sensitive event-related potentials during infancy: a review. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 51, 45–58 (2003).

Leppänen, J. M. & Nelson, C. A. Tuning the developing brain to social signals of emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 37–47 (2009).

Bauer, M., Stenner, M.-P., Friston, K. J. & Dolan, R. J. Attentional modulation of alpha/beta and gamma oscillations reflect functionally distinct processes. J. Neurosci. 34, 16117–16125 (2014).

Jensen, O. & Mazaheri, A. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 4, (2010).

Bastos, A. M. et al. Canonical microcircuits for predictive coding. Neuron 76, 695–711 (2012).

Fries, P. Neuronal gamma-band synchronization as a fundamental process in cortical computation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 32, 209–224 (2009).

He, W., Brock, J. & Johnson, B. W. Face processing in the brains of pre-school aged children measured with MEG. NeuroImage 106, 317–327 (2015).

Kylliäinen, A., Braeutigam, S., Hietanen, J. K., Swithenby, S. J. & Bailey, A. J. Face and gaze processing in normally developing children: a magnetoencephalographic study. Eur. J. Neurosci. 23, 801–810 (2006).

Taylor, M. J., Mills, T., Zhang, L. & Pang, E. W. Face processing in children: novel MEG findings. In 17th International Conference on Biomagnetism Advances in Biomagnetism—Biomag2010 (eds Supek, S. & Sušac, A.) 314–317 (Springer, 2010).

Blakemore, S.-J. & Mills, K. L. Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing?. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 65, 187–207 (2014).

Somerville, L. H. The Teenage Brain: Sensitivity to Social Evaluation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 121–127 (2013).

Boyatzis, C. J., Chazan, E. & Ting, C. Z. Preschool Children’s Decoding of Facial Emotions. J. Genet. Psychol. 154, 375–382 (1993).

Ptak, R. The Frontoparietal Attention Network of the Human Brain: Action, Saliency, and a Priority Map of the Environment. Neuroscientist 18, 502–515 (2012).

Moore, T., Armstrong, K. M. & Fallah, M. Visuomotor Origins of Covert Spatial Attention. Neuron 40, 671–683 (2003).

Friston, K. A theory of cortical responses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 360, 815–836 (2005).

Womelsdorf, T. & Fries, P. The role of neuronal synchronization in selective attention. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 154–160 (2007).

Engell, A. D. & McCarthy, G. Selective Attention Modulates Face-Specific Induced Gamma Oscillations Recorded from Ventral Occipitotemporal Cortex. J. Neurosci. 30, 8780–8786 (2010).

Corbetta, M., Patel, G. & Shulman, G. L. The Reorienting System of the Human Brain: From Environment to Theory of Mind. Neuron 58, 306–324 (2008).

Saxe, R. & Kanwisher, N. People thinking about thinking people. The role of the temporo-parietal junction in ‘theory of mind. Neuroimage 19, 1835–1842 (2003).

Schurz, M., Radua, J., Aichhorn, M., Richlan, F. & Perner, J. Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 42, 9–34 (2014).

Gallese, V., Keysers, C. & Rizzolatti, G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 396–403 (2004).

Van Overwalle, F. et al. Consensus Paper: Cerebellum and Social Cognition. Cerebellum 19, 833–868 (2020).

Gao, R., Peterson, E. J. & Voytek, B. Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials. NeuroImage 158, 70–78 (2017).

Uhlhaas, P. J. & Singer, W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 100–113 (2010).

Deen, B., Koldewyn, K., Kanwisher, N. & Saxe, R. Functional Organization of Social Perception and Cognition in the Superior Temporal Sulcus. Cereb. Cortex 25, 4596–4609 (2015).

Heatherton, T. F. Neuroscience of Self and Self-Regulation. Annu Rev. Psychol. 62, 363–390 (2011).

Schilbach, L. et al. Being with virtual others: Neural correlates of social interaction. Neuropsychologia 44, 718–730 (2006).

Deeley, Q. et al. Changes in male brain responses to emotional faces from adolescence to middle age. Neuroimage 40, 389–397 (2008).

Nejati, V., Majdi, R., Salehinejad, M. A. & Nitsche, M. A. The role of dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the processing of emotional dimensions. Sci. Rep. 11, 1971 (2021).

Booth, J. R. et al. Neural development of selective attention and response inhibition. NeuroImage 20, 737–751 (2003).

Crone, E. A. & Dahl, R. E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 636–650 (2012).

Velanova, K., Wheeler, M. E. & Luna, B. Maturational Changes in Anterior Cingulate and Frontoparietal Recruitment Support the Development of Error Processing and Inhibitory Control. Cereb. Cortex 18, 2505–2522 (2008).

Fung, M. H. et al. The development of sensorimotor cortical oscillations is mediated by pubertal testosterone. NeuroImage 264, 119745 (2022).

Heinrichs-Graham, E. et al. The lifespan trajectory of neural oscillatory activity in the motor system. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 30, 159–168 (2018).

Wilson, T. W. et al. An extended motor network generates beta and gamma oscillatory perturbations during development. Brain Cogn. 73, 75–84 (2010).

Erb, C. D., Moher, J. & Marcovitch, S. Attentional capture in goal-directed action during childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 214, 105273 (2022).

Hillebrand, A. & Barnes, G. R. A quantitative assessment of the sensitivity of whole-head MEG to activity in the adult human cortex. Neuroimage 16, 638–650 (2002).

Freschl, J., Azizi, L. A., Balboa, L., Kaldy, Z. & Blaser, E. The development of peak alpha frequency from infancy to adolescence and its role in visual temporal processing: A meta-analysis. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 57, 101146 (2022).

McSweeney, M. et al. Age-related trends in aperiodic EEG activity and alpha oscillations during early- to middle-childhood. NeuroImage 269, 119925 (2023).

Fung, M. H. et al. The impact of pubertal DHEA on the development of visuospatial oscillatory dynamics. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 5154–5166 (2022).

Picci, G. et al. Developmental changes in endogenous testosterone have sexually-dimorphic effects on spontaneous cortical dynamics. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 6043–6054 (2023).

Haxby, J. V., Hoffman, E. A. & Gobbini, M. I. Human neural systems for face recognition and social communication. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 59–67 (2002).

Conley, M. I. et al. The racially diverse affective expression (RADIATE) face stimulus set. Psychiatry Res. 270, 1059–1067 (2018).

Brainard, D. H. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10, 433–436 (1997).

Taulu, S., Simola, J. & Kajola, M. Applications of the signal space separation method. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 53, 3359–3372 (2005).

Taulu, S. & Simola, J. Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in MEG measurements. Phys. Med. Biol. 51, 1759–1768 (2006).

Uusitalo, M. A. & Ilmoniemi, R. J. Signal-space projection method for separating MEG or EEG into components. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 35, 135–140 (1997).

Pulliam, H. R. et al. Neurotoxic effects of home radon exposure on oscillatory dynamics serving attentional orienting in children and adolescents. NeuroImage 292, 120606 (2024).

Kovach, C. K. & Gander, P. E. The demodulated band transform. J. Neurosci. Methods 261, 135–154 (2016).

Ernst, M. D. Permutation Methods: A Basis for Exact Inference. Stat. Sci. 19, 676–685 (2004).

Maris, E. & Oostenveld, R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J. Neurosci. Methods 164, 177–190 (2007).

Gross, J. et al. Dynamic imaging of coherent sources: Studying neural interactions in the human brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 98, 694–699 (2001).

Van Veen, B. D., Van Drongelen, W., Yuchtman, M. & Suzuki, A. Localization of brain electrical activity via linearly constrained minimum variance spatial filtering. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 44, 867–880 (1997).

Hillebrand, A., Singh, K. D., Holliday, I. E., Furlong, P. L. & Barnes, G. R. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum. Brain Mapp. 25, 199–211 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants R01-MH121101 (T.W.W.), P20-GM144641 (T.W.W.), F30-MH134713 (J.J.S.), and S10-OD028751 (T.W.W.) from the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The data presented in this manuscript have not been published or presented elsewhere.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W.W., G.P. and B.K.T. conceived and designed the task. T.W.W. obtained funding. D.L.R., G.C.E., R.J.G., H.J.O., J.A.J, A.T.C. and E.L.S. collected the data. H.B., J.J.S., N.M.P., V.D.C., Y.P.W., L.M.S., T.W.W., B.K.T. and G.P. developed methodology and software. H.B. and J.J.S preprocessed the data. H.B., J.J.S., N.M.P., B.K.T., G.P. and T.W.W. performed statistical analyses. H.B., J.J.S. and T.W.W. wrote the original manuscript. All authors reviewed, provided feedback on, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Helen Blank and Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, H., Son, J.J., Petro, N.M. et al. Dynamic developmental signatures of facial expression processing differ by emotion. Commun Biol 8, 1395 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08808-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08808-z