Abstract

Ocean acidification from increasing atmospheric CO2 is progressively affecting seawater chemistry, but predicting ongoing and near-future consequences for marine ecosystems is challenging without empirical field data. Here we quantify tropical coral reef benthic communities at 37 stations with varying exposure to submarine volcanic CO2 seeping, and determine the aragonite saturation state (ΩAr) where significant changes occur in situ. With declining ΩAr, reef communities displayed progressive retractions of most reef-building taxa and a proliferation in the biomass and cover of non-calcareous brown and red algae, without clear tipping points. The percent cover of all complex habitat-forming corals, crustose coralline algae (CCA) and articulate coralline Rhodophyta declined by over 50% as ΩAr levels declined from present-day to 2, and importantly, the cover of some of these groups was already significantly altered at an ΩAr of 3.2. The diversity of adult and juvenile coral also rapidly declined. We further quantitatively predict coral reef community metrics for the year 2100 for a range of emissions scenarios, especially shared socio-economic pathways SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0. The response curves show that due to ocean acidification alone, reef states will directly depend on CO2 emissions, with higher emissions causing larger deviations from the reefs of today.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human activities are increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations at a rate unprecedented for at least the last 66 million years1,2. Approximately one quarter of this CO2 is absorbed by the surface waters of the world’s oceans, increasing the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), lowering pH and causing the chemical changes known as ocean acidification3. Oceanic pH is now lower than it has been for over 800,000 years, and this will likely be irreversible for millennia4,5. Ocean acidification is also lowering the saturation state of aragonite (ΩAr), with levels declining in tropical waters at a rate of ~0.1 units per decade6,7. Importantly, ocean acidification is not a future-only problem, and while the ongoing chemical changes are increasingly well documented7,8,9, the present-day and near-future responses of marine communities remain less well understood.

Most ocean acidification studies compare biological responses between present-day control conditions and one or few levels of increased CO2, typically under artificial experimental conditions10. While these studies have formed the basis of our understanding of the effects of ocean acidification, they are unable to investigate any continual changes in the responses11. Biological responses to a changing environment may be gradual and smooth, or abrupt when thresholds are present and a sharp transition or change in the slope of the response curve occurs over a smaller environmental change11,12,13,14. With few treatment levels it is not possible to identify the minimum increase in CO2 that will result in a significant biological response15, as this may be occurring at CO2 levels below those typically used as experimental treatments16. Hence experimental outcomes and the interpretation of effects can depend on the number of experimental treatments, their concentrations and exposure times10,14. Furthermore, laboratory experiments can only approximate in situ environmental conditions and are largely void of species interactions, limiting their extrapolation to communities in natural environments. There is thus a need to study marine communities exposed to multiple levels of ocean acidification in situ, to better understand how this ongoing change is shaping communities today and in the near future.

Coral reefs are particularly vulnerable to ocean acidification because they are built by organisms with calcium carbonate skeletons (CaCO3), and lowered pH and ΩAr can inhibit calcification and accelerate CaCO3 dissolution17. Scleractinian corals have long been considered susceptible to these effects due to their aragonite skeletons10,18,19, and the high-Mg-calcite skeletons of crustose coralline algae (CCA) and other calcareous algae have been repeatedly shown to be particularly sensitive20,21. The reef matrix itself and sediments are largely made of CaCO3 and may be impacted sooner than many organisms as they have large surface-area to volume ratios and are not isolated from the adjacent seawater by tissue layers22. Ocean acidification also increases dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) concentrations, which can stimulate photosynthesis in certain circumstances23,24. Some non-calcareous photosynthetic reef organisms are predicted to benefit from ocean acidification if their photosynthesis is stimulated and calcareous competitors are simultaneously constrained25.

Investigations of the effects of ocean acidification on reef communities have been based on mesocosm experiments26,27,28 and observations at naturally occurring high CO2 analogues, e.g. volcanic CO2 seep sites29,30,31,32 or other oceanographic features affecting carbon chemistry33,34,35. While substantial variation exists between studies, they generally show consensus with the larger existing body of experimental work: that ocean acidification is likely to negatively affect many calcareous taxa (e.g. corals and CCA), while benefiting some non-calcareous groups (e.g. certain algae, sponges and seagrass). However, the magnitude and rate of change to reef communities under progressive ocean acidification remains largely unknown, including whether the changes will be linear or will occur at any abrupt tipping point11.

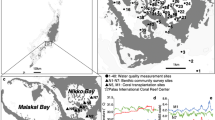

In this study we compare coral reef benthic communities at 37 stations representing a range of long-term ocean acidification conditions around volcanic CO2 seeps where strings of pure CO2 gas bubbles emerge from the sea floor. Except for contrasting levels of CO2 exposure, environmental conditions (e.g. levels of light, temperature, salinity and water flow) were similar across stations in this unique natural laboratory. We examined changes in the cover of common taxa, the density of young corals, and the biomass of different algal groups along the CO2 gradient. For the first time, these response curves allowed us to quantify the minimum CO2 increases that resulted in significant reef functional changes, and to project future changes to key coral reef benthos under different CO2 emission scenarios.

Results

Carbon chemistry

The stations were distributed across a field of patches with contrasting seeping activity, extending from areas unaffected by volcanic CO2 reflecting today’s mean carbon chemistry into patches with dense bubble streams representing predicted mean future conditions (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1). Ambient stations unaffected by the volcanic CO2 recorded total pH (pHT) values averaging 8.02 ± 0.01 SE. Fifteen stations within the seep area were within 0.2 pH units of ambient values, and the remaining seven stations recorded a mean pHT below 7.8 (minimum station mean pHT: 7.27 ± 0.03). At ambient stations, total alkalinity (AT) averaged 2253 ± 1.16 µmol kg-1 seawater, and AT increased along the gradient of seep exposure to 2331 µ mol kg-1 SW (Fig. 1). The calculated saturation state of aragonite (ΩAr) was highly correlated with pHT, but increased relative to pHT at pHT values below ~7.7 due to their elevated AT, likely due to increased CaCO3 dissolution. ΩAr at stations unaffected by volcanic CO2 averaged 3.57 ± 0.02 while stations exposed to volcanic CO2 had ΩAr ranging from 3.39 to 0.79. Due to its significance for calcifying organisms and its high correlation to pH and other carbonate chemistry parameters, ΩAr was chosen as a proxy to characterise the ocean acidification level of each station. Temperature did not change along the carbon chemistry gradient (SeaFET logger data, GLM, p > 0.05), ranging from 27.5 – 28.8 °C across stations (Supplementary Table 1).

Coral communities—benthic cover

A redundancy analysis indicated that changes in the reef communities across the stations were strongly related to ΩAr (PERMANOVA: ΩAr (1, 35), F = 2.594, p = 0.001). In the ordination plot, most stations with the highest ΩAr clustered closely together, with positive RDA1 axis values that were associated with an increased percent cover of many calcareous taxa, including the important reef habitat-building hard corals Acropora, Pocillopora, Seriatopora, Goniastrea and Fungia spp., as well as articulate calcareous Rhodophyta and crustose coralline algae (CCA) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). Station benthic communities with mean ΩAr values < 3.0 typically recorded negative RDA1 values (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). Seep site stations with lower ΩAr were typically associated with higher cover of noncalcareous taxa including brown and red macroalgae, sponges and the soft coral Sarcophyton spp., as well as the hard coral Porites (Fig. 2).

Points represent station means and their colours represent their station mean aragonite saturation state (ΩAr). The top 50% of the most influential vectors are shown. Vector labels for noncalcareous taxa (NCalc) are written in green, for calcareous taxa in black. All vector labels and scores are listed in Supplementary Table 3.

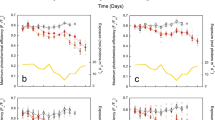

The in situ data documented continual changes in reef benthic communities in response to near-future ocean acidification (Fig.3, Table 1). In general, abrupt thresholds were not detected, but rather we observed continual smooth changes along the ΩAr gradient. Changes were either linear or log-linear, with different slopes or susceptibilities between taxa. The percent cover of all scleractinian corals combined did not change along the ΩAr gradient and averaged 36.15 ± 1.59% across all stations (generalised linear models, Supplementary Table 2). This was largely driven by the cover of massive Porites spp., which was unaffected by ΩAr. However, without massive Porites spp., the cover of all remaining hard corals combined declined compared to ambient values, by 20% at ΩAr 3.0, and by 35% at ΩAr 2.5 (Fig. 3, Table 1). The combined cover of structurally complex hard corals (i.e. branching, corymbose and tabulate growth forms), which are important as habitat for a large proportion of reef-associated organisms, was highly susceptible. Here the no-significant-effect concentration (NSEC), being the ΩAr value where the mean response first occurs outside the 99% confidence intervals of the response at ambient ΩAr values, indicated that complex coral cover became significantly lower than control values with a reduction in ΩAr of <0.4 units (NSEC ΩAr = 3.11). This decline matched patterns in the overall complexity score for each quadrat (Table 1). The cover of the genera Acropora, Seriatopora and Pocillopora were all highly susceptible and reduced by at least 30% by ΩAr 3.0. The combined cover of non-complex hard corals (i.e. massive, submassive and encrusting growth forms) was unaffected by the ΩAr gradient, again driven by massive Porites cover. However, even some robust taxa such as Goniastrea spp., and the Merulinidae and Fungiidae declined along the ΩAr gradient (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2). While no clear threshold was seen, virtually no other corals besides massive Porites spp. were found at stations with a mean ΩAr < 2.0 (Fig. 3). The other hard coral families recorded (Agariciidae, Diploastraeidae, Lobophyllidae and Euphylliidae) averaged <1% cover each and were not analysed individually. Soft coral cover was also low (1.28% ± 0.36) and statistically unaffected by ΩAr, although practically no soft corals were found below ΩAr 2.5. Sponge cover increased along the ΩAr gradient by >150% of control values at ΩAr 2.5.

The plots show percent cover of the resilient massive Porites spp. coral (a), all hard corals excluding massive Porites spp. b the important habitat-forming corals Acropora spp. c and Pocilloporidae (d), and important algal groups: crustose coralline algae (CCA) (e), articulate calcareous Rhodophyta (Red) (f), non-calcareous Rhodophyta (g), and non-calcareous Phaeophyta (Brown) (h). Point colour represents station mean ΩAr (legend as per Fig. 2). The black line is the modelled mean, and the grey lines are 95% confidence intervals (CI). The red vertical line is the no-significant-effect concentration (NSEC). * denotes statistical significance in generalised linear models at p < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 2).

Coral diversity and juvenile densities

Hard coral diversity, and hard and soft coral juvenile densities and diversity, all declined along the ΩAr gradient (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 2). Adult and juvenile hard coral diversity were highly correlated (Pearson’s correlation: t = 7.91, df = 31, p < 0.001), and both reduced significantly from ambient values as ΩAr declined by as little as 0.3 units (NSEC ΩAr = 3.20). Adult soft coral diversity was low, averaging 0.04 ± 0.16 genera m-2 across all sites, and was statistically similar along the ΩAr gradient. Soft coral juveniles were also sparse, but more sensitive to ΩAr declines than the hard corals. The diversity and density of soft coral juveniles declined by 50% between ΩAr 3.5 to 3.0, and none were found below ΩAr ~ 2.6. This was approximately the same ΩAr value at which adult soft coral percent cover was reduced to zero.

The diversity of adult hard corals (HC) (a), juvenile hard corals (b), adult soft corals (SC) (c), juvenile soft corals (d), and the density of juvenile hard (e) and soft corals (f) in relation to station aragonite saturation state (ΩAr). See Fig. 3 legend for plot description.

Macroalgal cover and biomass

The cover of algal communities also changed along the ΩAr gradient, with a general shift from calcareous to non-calcareous taxa from ambient ΩAr into the seeps (Fig. 3). The percent cover of all calcareous algae combined at control sites declined by 20% and 35% at ΩAr 3.0 and 2.5, however susceptibility differed between taxa. The abundant heavily calcified articulate Rhodophyta were the most affected, their cover was significantly reduced between ambient ΩAr and 3.25, and none were found at <2.4. Crustose coralline algae (CCA) were also highly sensitive, and cover declined by 40% between ambient and ΩAr 3.0. Both algal groups were virtually non-existent at ΩAr ≤ 2.5. In contrast, turf algae and the weakly calcified red algae Peyssonnelia spp. were unaffected by ΩAr. Total non-calcareous macroalgal cover increased as ΩAr declined. This was due to non-calcareous brown and red algae, which similarly increased cover by 65% and 85% from ambient values to ΩAr 2.5. Halimeda spp. and Padina spp. (the only calcareous green and brown algae recorded), and non-calcareous green algae each had <0.5% cover and were too low to analyse individually.

The biomass (dry weight) of all collected macroalgae combined was highest at ΩAr 3.5 and declined 15% and 30% by ΩAr 3.0 and ΩAr 2.5. This was due to high calcareous macroalgal biomass at controls, which declined by 25% at ΩAr 3.0, and by 50% at ΩAr 2.5 (Fig. 5). Calcareous algae made up 50% of total macroalgal biomass at the controls, but this ratio declined to <25% at ΩAr 2.5. Total non-calcareous macroalgal biomass was unaffected by ΩAr, averaging 49.41 ± 6.08 g m-2 across all stations. This was due to a replacement of high Turbinaria spp. at ambient CO2 by Melanamansia spp. as CO2 increased: at ΩAr 2.5 Turbinaria spp. were almost completely absent, while Melanamansia spp. more than doubled. Total non-calcareous algal biomass, without Turbinaria spp., greatly increased along the ΩAr gradient (Fig. 5).

The biomass of all macroalgae (a), calcareous macroalgae (b), total non-calcareous macroalgae without Turbinaria spp. c and the ratio of calcareous (Calc) to total macroalgal biomass (d) in relation to station aragonite saturation state (ΩAr). See Fig.3 legend for plot description.

Discussion

Our empirical data from this unique natural laboratory demonstrate the drastic rates of change in coral reef benthic communities along a gradient of declining ΩAr. At present-day CO2, these coral reefs support a diverse community of scleractinian corals and calcareous algae. These are increasingly replaced by some non-calcareous algae, massive Porites spp. corals and sponges as CO2 concentrations increase. High-CO2 communities are also increasingly less diverse and less structurally complex. Our study uniquely served to quantify near-future changes in reef communities from ocean acidification, and to define the ΩAr values that result in a significant deviation from the reefs of today. The results add to a large body of work predicting fundamental changes to coral reef communities and functions by the end of the century, with the magnitude of change dependent on the atmospheric CO2 emissions pathway realised. Alarmingly, these results also show that reef community changes are likely already occurring within the range of dissolved CO2 levels observed on contemporary reefs16,36.

The few studies with sufficient levels of CO2 to investigate continual changes to reef communities under increasing ocean acidification have shown both linear and threshold responses. Laboratory experiments on individual organisms have shown mostly linear effects11, while results of community-based studies or those in situ suggest tipping points may also occur13,16. For example, Smith et al.16 and Kleypas et al.37 both suggest that there will be a threshold in coral and algal community change between ΩAr 3.4 and 3.6, and ΩAr 3.0 has been suggested as the limit for global reef development37,38. We also previously deployed standardised settlement substrate along a gradient of increasing CO2 at this and other seep sites in Papua New Guinea, and found newly recruited CCA communities were almost absent on these surfaces at mean ΩAr < 2.513. In the present study, we found linear or log-linear changes in most parameters measured along the CO2 gradient, beginning immediately as ΩAr declined from ambient values, and although CCA and several complex coral taxa reached very low values at 2.5 ΩAr, there was little evidence of a firm tipping point or threshold for the reef communities. Here communities began to significantly change from the present-day as ΩAr values declined by as little as 0.25 units. This immediate progressive response without thresholds highlights two important considerations. Firstly, any coral reef community thresholds in response to ΩAr declines may have already been exceeded, as global ΩAr values are now 0.5 units lower than at the advent of the Industrial Revolution9,39. Yet we are using present-day values as our baseline and cannot infer the shape of response curves at higher ΩAr values. Secondly, the lack of thresholds indicates that even small deviations in seawater ΩAr from present-day ambient values will continue to alter coral reef communities, and the magnitude of change that communities experience into the future will likely directly depend on the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere.

We documented a range of contrasting susceptibilities between taxa along the ΩAr gradient. The NSEC values indicated habitat complexity was the most sensitive metric, followed by the cover of articulate calcareous red algae, the ratio of calcareous to total algal biomass, coral diversity and juvenile coral density, then the cover of several complex habitat-forming corals and CCA. The percent cover of all hard coral taxa abundant enough for analyses, except for massive Porites spp., was shown to be negatively affected by the increasing ΩAr gradient. Importantly, hard coral diversity, in both adult and juvenile life-stages, significantly declined with a ΩAr reduction of 0.3 units. At the present rate of change, these mean ΩAr values will be reached in the tropics by the year ~20606,7,39. Reef communities continued to change below this ΩAr level, and a reduction of 0.5 ΩAr units from ambient values, as expected throughout the tropics by 2100 under the emissions scenario SSP2-4.56,39, was associated with considerable community change. By ΩAr 3.0, the percent cover of the highly susceptible calcareous red algae (both CCA and articulate calcareous Rhodophyta) halved, and the cover of structurally complex coral species (e.g. the Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae) reduced by 30%. These more sensitive corals were then almost absent from communities by ΩAr levels of 2.5, as predicted for the end of the century under emissions scenario SSP3-7.0. The mean ΩAr of contemporary reefs in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef ranges by 0.5 units, and reefs at the lower end of this gradient similarly record reduced CCA and coral juvenile abundances16,36. Hence the effects of reduced ΩAr are already manifest in some present-day reefs, and these patterns will strengthen as atmospheric CO2 increases.

Previous studies examining changes to reef communities exposed to elevated CO2 have also largely shown declines in calcareous taxa and concomitant increases in the non-calcareous29,31,32,40. The mechanisms responsible for community changes are not fully understood, as the response of communities to high CO2 is often greater than the direct physiological responses seen for individual taxa. For example, metanalyses from Kornder et al.19 report calcification rates are reduced by an average of 18% at ΩAr < 2.5 for all corals combined. In contrast, in the present study, communities at ΩAr 2.5 exhibited a > 30% reduction in hard coral diversity and a decline of >50% cover of the more sensitive taxa compared to ambient values. Here high CO2 communities were dominated by massive Porites, which can be important components of the reef framework41, but lack the structural complexity to provide shelter for many habitat-associated species42,43,44. The observed declines in CCA and proliferation of Melanamansia spp. and other non-calcareous macroalgae at low ΩAr also likely impacted coral communities, as CCA facilitates coral recruitment while macroalgae hinders it45,46. The differential responses of certain algae, for example the decline in the non-calcareous Turbinaria spp. and relative robustness of the lightly calcareous Peyssonnelia spp. at high CO2, require further investigation. The seep communities are likely shaped not only by the direct physiological effects of elevated CO2 on certain taxa, but also by indirect ecological effects that can have substantial impact and are difficult to predict based on physiological studies alone42,43,47.

Our empirical data show that the magnitude of change to coral reef communities attributable to ocean acidification by 2100 will strongly depend on CO2 emissions. By 2050, ΩAr will likely be 0.2 units lower than at present7, but by 2100, levels will vary greatly depending on the SSP scenario realised6,39. Under the most optimistic IPCC scenario (SSP1–1.9), where CO2 emissions are cut to net zero by 2050 and atmospheric CO2 will have slightly eased, coral reefs in 2100 will not be altered greatly by ocean acidification in comparison to the present day (Fig. 6). Alternatively, the most pessimistic scenario (SSP5–8.5), where present-day annual CO2 emissions triple by 2100, would result in drastic changes to reef communities. It is becoming increasingly unlikely that either of these extreme scenarios will occur, with more recent estimates suggesting that SSP3-7.0 may be most appropriate in impact assessment studies48. Under this scenario, 2100 coral reefs would see considerable declines in hard coral diversity (40%), the percent cover of CCA (70%) and complex coral species (60%), and drastic increases in the cover of non-calcareous macroalgae (80%) (Fig. 6). If emissions are limited to the more conservative SSP2–4.5, we may still see a 50% loss in CCA cover and a 40% increase in the cover of non-calcareous macroalgae by 2100. Importantly, these predictions consider the effects of ocean acidification in isolation, and coral reefs are under increasing pressure from a range of sources. Global mass coral bleaching events from marine heat waves, also driven by anthropogenic CO2 emissions, and other forms of disturbances from climate change, are increasing in frequency and intensity and are increasingly impacting the world’s coral reefs49.

Shown are the percent cover of complex hard corals (HC, light grey), crustose coralline algae (CCA, magenta), non-calcareous (NCalc) macroalgae (blue), and hard coral diversity (black). The vertical lines represent the ΩAr values predicted for much of the tropics for the year 2100 by Jiang et al.39 for the five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways emission scenarios: SSP1–1.9 (blue), SSP1–2.6 (yellow), SSP2–4.5 (orange), SSP3–7.0 (brown) and SSP5–8.5 (red)6,39.

These CO2 seep sites are not perfect representations of future coral reefs. They are small in size and lack the co-occurring elevated temperature stress expected under climate change. Seep CO2 levels are also characteristically variable, especially within areas with low mean pH29 (Supplementary Fig. 1), and effects of this variability are largely unknown for most coral reef organisms50. Hence extrapolating the results seen here to the future of coral reefs globally will attract some uncertainty. However, studies in situ at CO2 seeps have advantages over laboratory studies (e.g. organisms grow under natural conditions of ecological interactions and have life-time acclimation) and hence provide unique insights into the effects of ongoing ocean acidification on marine communities.

Anthropogenic ocean acidification has been ongoing since the start of the Industrial Revolution, and global CO2 emissions continue to rise largely unabated6. Reliable in situ data are essential to validate observed changes from ocean acidification that have likely already occurred (but are not usually factored into models or debates), and to predict how they will continue to impact coral reefs6,16,51. Our data clearly show that these changes will intensify in the coming decades, with reef communities shifting away from dominance by many scleractinian corals towards less diverse and structurally complex communities characterised by fewer tolerant species and non-calcareous taxa, with a raft of flow-on effects on reef-associated organisms42,43. The magnitude of this change will depend on our CO2 emissions pathway, with more emissions resulting in a greater change to present-day coral reefs. Reef resilience and recovery following disturbances will also decline, as ocean acidification reduces rates of coral recruitment52. Reductions in atmospheric CO2 levels are urgently needed to prevent further deviations from the reefs of today.

Methods

This study was conducted at the volcanic CO2 seep at Upa-Upasina, Normanby Island, Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea (PNG). The CO2 seep site has been described in detail by Fabricius et al.29. It is characterised by a mosaic of nearly pure CO2 gas seeping through the sea floor in patches of varying intensity in the shallow waters along several hundred metres of coastline. This CO2 locally alters the carbon chemistry of the seawater without altering the temperature or salinity24,44. Seeping intensity is characteristically variable over short timeframes (minutes to hours), but mean CO2 levels around the seep site have remained relatively constant over 6 years of sampling (e.g. Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3 from29 and the present study). To reach areas unaffected by the volcanic CO2, stations were spread well beyond the area of visible seeping, up to ~500 m to the south and north of the seep along the same island fringing reef. Sampling stations were established at ~3 m depth, each marked with a small sub-surface float (n = 37). Stations were spread widely across and along the seep seascape, to capture varying seep intensities.

The carbon chemistry of each of the 37 stations was characterised in two ways. Firstly, bottle samples were collected ~twice-daily for 2 weeks at each station for pH and total alkalinity (AT). Where CO2 was elevated, one sample per station was taken during each sample period (pH n = 17–18, AT n = 3–4 per station). Of the fifteen stations unaffected by volcanic CO2, six were investigated for their carbon chemistry (pH n = 11 – 17, AT = 3–4), and the remaining nine stations were given the average carbon chemistry values of the adjacent ambient stations in further analyses. All pH samples were measured within 1 h of collection using a benchtop pH electrode (Eutech) and meter (Oakton, USA), with mV converted to pHTotal (hereafter pHT) by comparison to readings from a certified TRIS pH buffer (A.G. Dickson lab, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, USA) following standard procedures53. Samples for AT were preserved with saturated HgCl2 and processed at the laboratories of the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) within 1 month of collection using open cell potentiometric titration (855 robotic titrosampler, Metrohm) following Dickson et al.53. AT values were calculated using a Gran function and comparisons to certified reference materials were <5 µmol kg-1 (CRM batch 141, A.G. Dickson lab, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, USA). Secondly, pH loggers (SeaFET, Seabird USA) were deployed for ~24 h at each station, sampling every 10 min. The two pH loggers rotated through all but three of the CO2 affected stations (n = 19), and two of the stations unaffected by volcanic CO2. The pH loggers were also deployed side-by-side away from the seep in ambient seawater three times throughout the sampling period, and an offset was applied to one instrument to account for differences between loggers (~0.07 pHT) after comparisons with parallel bottle pH samples (n = 3). Estimates of station pH derived from the bottle measurements and SeaFET loggers were highly correlated (Supplementary Fig. 1) and subsequently combined for further analyses. To do so, pH data were averaged for each method after being standardised by the square root of their sample size. Here sample size was either the number of bottle samples, or the number of 10 min readings the SeaFET took over the ~24 h deployment at each station. This weighted approach avoided either dataset obscuring the other. Measured pHT and AT values were used to calculate the remaining carbon chemistry variables for each station using the CO2SYS macro54 with the constants of Dickson and Milero55 (Supplementary Table 1).

At each station, a series of 1 m2 quadrats were sampled on SCUBA to characterise benthic communities. Four quadrats were sampled at each station, however five stations unaffected by volcanic CO2 had only two quadrats sampled. Quadrats were placed immediately around the sub-surface floats, to ensure the measured carbon chemistry parameters from the floats were representative of the quadrat area. Quadrat placement avoided areas completely occupied by single large coral colonies, likely underrepresenting large table Acropora corals commonly found at the sites unaffected by volcanic CO2, as well as massive Porites spp. which dominate the seep29. Photographs were taken of each quadrat for analysis of benthic cover and community composition56. To do so photographs were overlaid with 28 evenly spaced points and the benthos underneath each was recorded to the highest taxonomic level possible (a total of 4004 observations). This was genus level for hard corals and soft corals, while macroalgae and other taxa were classified into phyla. Organisms were also categorised as being calcareous or not; calcareous being those with solid calcium carbonate supporting structures (e.g. the scleractinian corals and CCA), while non-calcareous lack these heavy deposits but includes some organisms that contain small amounts of CaCO3 (e.g. Peyssonnelia and Padina spp. algae and Sarcophyton soft corals). The morphology of hard corals was also recorded (e.g. branching Acropora spp., tabular Acropora spp. etc.). Visual in situ surveys were conducted in each quadrat for juvenile (<5 cm diameter) hard and soft coral density and diversity56. Each quadrat was further visually classified for structural complexity on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being least complex and 5 being highly complex43. Each type of survey was conducted by a single observer to minimise bias.

All macroalgae occurring within one quarter (i.e. 0.25 m2) of two of the quadrats per station were hand-collected by divers using a scraping tool. Larger areas were not sampled due to time constraints in the field. Much of the macroalgae were cryptic, occurring within the crevices of the reef where they were protected from grazing, and hence unlikely to be documented in the photo-surveys. Collections did not sample encrusting algal taxa, such as crustose coralline algae (CCA) and Peyssonnelia spp., nor turfs. Macroalgae samples were sundried, transported to AIMS, sorted into calcareous and non-calcareous taxa, and after 3 days in a drying oven at 60°C, weighed to the nearest 0.1 mg (Shimadzu AW220, Japan). The two most dominant genera (Melanamansia and Turbinaria) were also separated and weighed.

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistics were conducted in R (version 4.4.0)57. ΩAr values calculated from pHT and AT were chosen as predictors as they can strongly influence the physiology of corals and other calcareous reef taxa and were highly correlated with other carbon chemistry variables (Fig. 1). All benthic data (i.e. benthos percent cover, coral juvenile abundance and diversity, algal biomass etc.) were averaged across quadrats by station, prior to statistical analyses, as each station was represented by a single ΩAr value in models. Changes in the cover of the communities were first examined via redundancy analysis (RDA). This allowed the visualisation of multi-dimensional community data in two-dimensional space, and to test the significance of mean station ΩAr (continuous variable) on community changes via PERMANOVA.

Generalised linear models (GLM) were used to examine the changes in the percent cover of different taxa from the photo surveys, the density and diversity of hard and soft coral adult and juvenile corals, and biomass of the algal communities in relation to mean ΩAr from each of the stations. Different link functions were used in models depending on data type (Supplementary Table 2): quasibinomial for percent cover, quasipoisson for juvenile abundance and diversity counts, and gaussian for algal biomass weights. Algal weights were square-root transformed to better fit the assumed distribution, with the final model chosen based on lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC). The “Predict” function in R was used to estimate response values at ΩAr 3.5, 3.0 and 2.5, approximately representing ΩAr ambient values away from the seeps, and what is projected for tropical coral reefs in the region by the year 2100 under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) shared socio-economic pathways SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.06,39. No-significant-effect concentration (NSEC) values were also calculated for each GLM following Fisher and Fox15. Here the NSEC is the ΩAr where the predicted response first significantly deviates above or below (depending on the shape of the response curve) the response at an ambient ΩAr of 3.5.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Numerical source data underlying the main and Supplementary Figs. are included in Supplementary Data files1–4 and are available via the Australian Institute of Marine Science data repository: https://apps.aims.gov.au/metadata/view/76c40b3c-8535-43b6-bf5f-ad26d6e1ad92.

References

Lan, X., Tans, P. & Thoning. K.W. Trends in globally-averaged CO2 determined from NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory measurements. Version 2024-06 https://doi.org/10.15138/9N0H-ZH07 (2024).

Zeebe, R. E., Ridgwell, A. & Zachos, J. C. Anthropogenic carbon release rate unprecedented during the past 66 million years. Nat. Geosci. 9, 325–329 (2016).

Doney, S. C., Fabry, V. J., Feely, R. A. & Kleypas, J. A. Ocean acidification: the other CO2 problem. Annu Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 169–192 (2009).

Honisch, B., Hemming, N. G., Archer, D., Siddall, M. & McManus, J. F. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations across the mid-Pleistocene transition. Science 324, 1551–1554 (2009).

Hönisch, B. et al. The geological record of ocean acidification. Science 335, 1058–1063 (2012).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/ (2021).

Fabricius, K. E., Neill, C., Van Ooijen, E., Smith, J. N. & Tilbrook, B. Progressive seawater acidification on the great barrier reef continental shelf. Sci. Rep. 10, 18602 (2020).

Sutton, A. J. et al. Autonomous seawater pCO2 and pH time series from 40 surface buoys and the emergence of anthropogenic trends. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 421–439 (2019).

Findlay, H. S., Feely, R. A., Jiang, L., Pelletier, G. & Bednaršek, N. Ocean acidification: another planetary boundary crossed. Glob Change Biol 31, e70238 (2025).

Leung, J. Y. S., Zhang, S. & Connell, S. D. Is ocean acidification really a threat to marine calcifiers? a systematic review and meta-analysis of 980+ studies spanning two decades. Small 18, 2107407 (2022).

Cornwall, C. E., Comeau, S. & Harvey, B. P. Are physiological and ecosystem-level tipping points caused by ocean acidification? a critical evaluation. Earth Syst. Dynam 15, 671–687 (2024).

Comeau, S., Edmunds, P. J., Spindel, N. B. & Carpenter, R. C. The responses of eight coral reef calcifiers to increasing partial pressure of CO2 do not exhibit a tipping point. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 388–398 (2013).

Fabricius, K. E., Kluibenschedl, A., Harrington, L., Noonan, S. & De’ath, G. In situ changes of tropical crustose coralline algae along carbon dioxide gradients. Sci. Rep. 5, 9537 (2015).

Spake, R. et al. Detecting thresholds of ecological change in the Anthropocene. Annu Rev. Env Resour. 47, 797–821 (2024).

Fisher, R. & Fox, D. R. Introducing the no-significant-effect concentration. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 42, 2019–2028 (2023).

Smith, J. N. et al. Shifts in coralline algae, macroalgae, and coral juveniles in the great barrier reef associated with present-day ocean acidification. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 2149–2160 (2020).

Gattuso, J.-P., Frankignoulle, M., Bourge, I., Romaine, S. & Buddemeier, R. Effect of calcium carbonate saturation of seawater on coral calcification. Glob. Planet Change 18, 37–46 (1998).

Chan, N. C. S. & Connolly, S. R. Sensitivity of coral calcification to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 282–290 (2013).

Kornder, N. A., Riegl, B. M. & Figueiredo, J. Thresholds and drivers of coral calcification responses to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 5084–5095 (2018).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Understanding coralline algal responses to ocean acidification: meta-analysis and synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 362–374 (2022).

Peña, V. et al. Major loss of coralline algal diversity in response to ocean acidification. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 4785–4798 (2021).

Eyre, B. D. et al. Coral reefs will transition to net dissolving before end of century. Science 911, 908–911 (2018).

Suggett, D. J. et al. Sea anemones may thrive in a high CO2 world. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 3015–3025 (2012).

Noonan, S. H. C. & Fabricius, K. E. Ocean acidification affects productivity but not the severity of thermal bleaching in some tropical corals. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 715–726 (2016).

Connell, S. D., Kroeker, K. J., Fabricius, K. E., Kline, D. I. & Russell, B. D. The other ocean acidification problem: CO2 as a resource among competitors for ecosystem dominance. Philos. T R. Soc. Lon B 368, 20120442 (2013).

Langdon, C., Takahashi, T., Sweeney, C., Chipman, D. & Atkinson, J. Effect of calcium carbonate saturation state on the calcification rate of an experimental coral reef. Glob. Biogeochem. Cy 14, 639–654 (2000).

Dove, S. G. et al. Future reef decalcification under a business-as-usual CO2 emission scenario. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15342–15347 (2013).

Comeau, S., Carpenter, R. C. & Lantz, C. a. & Edmunds, P. J. Ocean acidification accelerates dissolution of experimental coral reef communities. Biogeosciences 12, 365–372 (2015).

Fabricius, K. E. et al. Losers and winners in coral reefs acclimatized to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Clim. Change 1, 165–169 (2011).

Inoue, S., Kayanne, H., Yamamoto, S. & Kurihara, H. Spatial community shift from hard to soft corals in acidified water. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 683–687 (2013).

Enochs, I. C. et al. Shift from coral to macroalgae dominance on a volcanically acidified reef. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1083–1088 (2015).

Cattano, C. et al. Changes in fish communities due to benthic habitat shifts under ocean acidification conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 725, 138501 (2020).

Manzello, D. Ocean acidification hot spots: Spatiotemporal dynamics of the seawater CO2 system of eastern Pacific coral reefs. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 239–248 (2010).

Crook, E. D., Potts, D., Rebolledo-Vieyra, M. & Hernandez, L. & Paytan, a. Calcifying coral abundance near low-pH springs: implications for future ocean acidification. Coral Reefs 31, 239–245 (2012).

Barkley, H. C. et al. Changes in coral reef communities across a natural gradient in seawater pH. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500328 (2015).

Mongin, M. et al. The exposure of the Great Barrier Reef to ocean acidification. Nat. Commun. 7, 10732 (2016).

Kleypas, J. A., McManus, J. W. & Menez, L. A. B. Environmental limits to coral reef development: where do we draw the line? Am. Zool. 39, 146–159 (1999).

Guinotte, J. M., Buddemeier, R. W. & Kleypas, J. A. Future coral reef habitat marginality: temporal and spatial effects of climate change in the Pacific basin. Coral Reefs 22, 551–558 (2003).

Jiang, L. Q. et al. Global surface ocean acidification indicators from 1750 to 2100. J. Adv. Model Earth Sy 15, e2022MS003563 (2023).

Agostini, S. et al. Ocean acidification drives community shifts towards simplified non-calcified habitats in a subtropical−temperate transition zone. Sci. Rep. 8, 11354 (2018).

Riegl, B. & Piller, W. E. Coral frameworks revisited-reefs and coral carpets in the northern Red Sea. Coral Reefs 18, 241–253 (1999).

Smith, J. N. et al. Ocean acidification reduces demersal zooplankton that reside in tropical coral reefs. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1124–1129 (2016).

Fabricius, K. E., De’ath, G., Noonan, S. & Uthicke, S. Ecological effects of ocean acidification and habitat complexity on reef-associated macroinvertebrate communities. P R. Soc. Lond. B Bio 281, 20132479 (2014).

Priest, J. et al. Out of shape: ocean acidification simplifies coral reef architecture and reshuffles fish assemblages. J. Anim. Ecol. 93, 1097–1107 (2024).

Harrington, L., Fabricius, K., De’ath, G. & Negri, A. Recognition and selection of settlement substrata determine post-settlement survival in corals. Ecology 85, 3428–3437 (2010).

Randall, C. J. et al. Larval precompetency and settlement behaviour in 25 Indo-Pacific coral species. Commun. Biol. 7, 142 (2024).

Hill, T. S. & Hoogenboom, M. O. The indirect effects of ocean acidification on corals and coral communities. Coral Reefs 41, 1557–1583 (2022).

Shiogama, H. et al. Important distinctiveness of SSP3–7.0 for use in impact assessments. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1276–1278 (2023).

Fabricius, K. E. et al. The seven sins of climate change: a review of rates of change, and quantitative impacts on ecosystems and water quality in the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 219, 118267 (2025).

Rivest, E. B., Comeau, S. & Cornwall, C. E. The role of natural variability in shaping the response of coral reef organisms to climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 3, 271–281 (2017).

Guo, W. et al. Ocean acidification has impacted coral growth on the great barrier reef. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2019GL086761 (2020).

Fabricius, K. E., Noonan, S. H. C., Abrego, D., Harrington, L. & De’ath, G. Low recruitment due to altered settlement substrata as primary constraint for coral communities under ocean acidification. P R. Soc. Lond. B Bio 284, 20171536 (2017).

Dickson, A. G. Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/ocean-carbon-acidification-data-system/oceans/Handbook_2007/Guide_all_in_one.pdf (2007).

Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/ocean-carbon-acidification-data-system/oceans/CO2SYS/co2rprt.html (1998).

Dickson, A. G. & Millero, F. J. A comparison of the equilibrium constants for the dissociation of carbonic acid in seawater media. Deep-Sea Res I. Oceanogr. Res Pap. 34, 1733–1743 (1987).

Jonker, M. J., Johns, K. & Osborne, K. Surveys Of Benthic Reef Communities Using Underwater Digital Photography And Counts Of Juvenile Corals. https://www.aims.gov.au/sites/default/files/Sop%20No%2010.pdf (2008).

R Development Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Riccardo Rodolfo-Metalpa, L’Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Noumea, New Caledonia, for co-funding the fieldwork through a grant by L’Agence nationale de la recherche, for collaboration and logistic support. We thank the community of Illi Illi Bwa Bwa (Upa Upasina) for allowing us access to their unique reefs, and the crew of the MV Chertan for supporting the field work. This project was funded by the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SN and KF conceived the study and conducted the fieldwork. SN and CB completed the lab work and image analyses. SN and RF conducted statistical analyses. SN wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided input to the writing of later manuscript drafts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Chris Langdon and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Linn Hoffmann and Michele Repetto. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noonan, S.H.C., Birrell, C., Fisher, R. et al. Progressive changes in coral reef communities with increasing ocean acidification. Commun Biol 8, 1518 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08889-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08889-w