Abstract

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity remains a critical challenge in pharmacological safety evaluation; however, the lack of analytical tools to distinguish cell-type-specific hepatotoxic responses hinders mechanistic understanding of toxicity pathways. Herein, we provide proof-of-principle for using an immunocompetent liver-on-a-chip platform that integrates six distinct cell models with a targeted cell depletion strategy to rapidly assess pharmaceutical candidates’ hepatotoxic profiles. The platform recapitulated immune cell migration dynamics and stress-responsive behaviors under chemokine induction, while integrated fluidic characterization ensured physiologically relevant microenvironmental control. We applied the targeted depletion strategy to resolve cell population-specific contributions to hepatotoxic outcomes using four mechanistically diverse compounds: acetaminophen, ethinyl estradiol, sulfamethoxazole, and abacavir. Our findings reveal coordinated participation of multiple hepatic cell populations in toxicological processes and identify dominant hepatotoxicity-inducing factors. The immune-dependent toxicity resolution was further validated using a known immune-mediated drug-induced liver injury drug, allopurinol. Overall, this study establishes a targeted cell depletion strategy integrated within an immunocompetent liver-on-a-chip platform, enabling rapid identification of hepatotoxic determinants, and represents a significant advancement in predictive toxicology systems, while providing strategic insights for subsequent pathway analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity, clinically recognized as drug-induced liver injury (DILI), represents a critical challenge in pharmaceutical development and post-marketing surveillance1,2. As a predominant cause of drug withdrawal from global markets, DILI accounts for ~20% of post-marketing pharmaceutical withdrawals and 50% of acute liver failure cases. The historical timeline of pharmaceutical withdrawals underscores persistent challenges in hepatotoxicity prediction, with notable examples including lumiracoxib (2007, HLA-associated injury), ximelagatran (2004, alanine aminotransferase elevation), troglitazone (2000, mitochondrial toxicity), bromfenac (1998, COX-mediated apoptosis), alpidem (1995, CYP 2C19 polymorphism-related toxicity), and iproniazid (1959, metabolic activation)3,4,5. These cases highlight the complexity of DILI pathogenesis involving genetic, metabolic, and immunological factors, emphasizing the urgent need for advanced human-relevant predictive models and in vitro systems to address limitations in preclinical hepatotoxicity screening.

Although in vivo experiments remain essential for drug evaluation, in vitro methods are favored due to their high efficiency, low cost, and ability to readily study toxicity mechanisms at the molecular or cellular level (e.g., enzyme activity, gene expression). Primary in vitro hepatotoxicity evaluation approaches include the use of recombinant enzymes6,7, immortalized cell lines, primary hepatocytes8, hepatic microsomes/subcellular fractions9, and 3D liver spheroids. While immortalized cell lines offer low-cost, high-throughput screening, they suffer from deficient metabolic enzyme activity and limited predictive accuracy. Primary hepatocytes retain native metabolic functions but exhibit donor variability and phenotypic instability. Hepatic microsomes are suitable for metabolite toxicity studies yet fail to simulate integrated pathophysiological processes. Although 3D spheroids maintain long-term hepatic functions and enable chronic toxicity detection, their complex construction results in low throughput. Crucially, all these approaches share significant limitations: static cultures neglect critical biomechanical cues; the absence of immune microenvironments is problematic (noting that >80% of DILI cases involve immune mechanisms); and risks associated with species extrapolation persist.

Emerging organ-on-a-chip technology has revolutionized in vitro reconstruction of cellular microenvironments, with successful development of kidney10,11, lung12,13, gut14,15, brain16,17, heart18,19, and skin20,21 chips that recapitulate partial organ functions. Moreover, the U.S. National Institutes of Health recently announced it would no longer fund new projects involving exclusively animal experiments22,23. This milestone marks a significant step toward replacing century-old animal testing with organ chips. Over the past decade, liver-on-a-chip platforms have evolved to incorporate multicellular systems, perfusion, and 3D culture, enabling development of anatomically, physiologically, and functionally realistic models24,25,26. For example, Corrado et al. developed a liver microsphere chip for drug metabolism assessment27; Dey et al. created a 3D-printed physiomimetic model of the human liver acinus for drug-induced liver injury studies28; and Cho et al. engineered a multicellular liver chip to investigate inflammatory responses in fibrosis29. Notably, 3D co-culture systems combining parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells enhance hepatocyte functionality, albumin/urea secretion, and cytochrome P450 activity30, improving hepatotoxicity prediction.

Despite these advances, integrating diverse immune cell populations into liver chips remains challenging31. Since immune cell-hepatocyte communication holds an important role in hepatic function32,33, recent studies have begun exploring immune-integrated liver systems. For example, Liu et al. developed an immune-liver chip and demonstrated that perfused circulating immune cells can reveal acetaminophen (APAP)-induced hepatocyte death and cytokine elevation. Deng et al. established a liver-immune microphysiological system to study troglitazone-induced immune-mediated hepatotoxicity34,35. However, these technologies are insufficient to reproduce the liver’s immune microenvironment due to their inability to mimic the complex in vivo microarchitecture and physiologically relevant fluid flow conditions, or to maintain long-term cellular viability and functionality. Additionally, few reports specifically dissect the critical contributions of distinct cell populations to DILI mechanisms. Accumulating evidence indicates that DILI involves diverse mechanisms, including hepatocellular necrosis, immune-mediated hepatitis, cholestasis, and fibrosis, which are often driven by Kupffer cell activation, inflammatory mediator release, or cholestatic interactions. Crucially, cell-type-specific variations in hepatotoxic responses remain poorly understood.

Herein, we engineered an immunocompetent liver-on-a-chip platform integrating six distinct cell types (HepG2, LX-2, EA.hy926, U937, HuT-78, and HL-60 cell lines) to dissect cell-type-specific hepatotoxic profiles of pharmaceutical candidates. This chip builds upon our previous development of biomimetic liver sinusoid-on-a-chip platforms24,25,26, which reconstructed hepatic architecture with four hepatocyte subtypes and dual blood-bile circulation. The bioengineered system replicates chemokine-mediated immune recruitment and pathophysiological stress signaling, with computational fluid dynamics ensuring physiological hemodynamics. Inspired by gene-knockout cells (a powerful tool for identifying signaling pathways) and immune-compromised nude mice (widely used in immunology studies), we propose a targeted cellular depletion strategy to rapidly assess pharmaceutical candidates’ hepatotoxic profiles within this biomimetic chip platform. This approach compares responses in the intact chip with those in the targeted cell-depleted chip to investigate the role of specific cell types. For proof-of-concept validation, we applied this strategy to resolve cell population-specific contributions to hepatotoxicity using four mechanistically diverse compounds: APAP, ethinyl estradiol (EE), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and abacavir (ABC). Our results revealed distinct mechanisms. We further validated the detection of immune-dependent toxicity through targeted cellular depletion using allopurinol (ALP), a known immune-mediated DILI drug. This study establishes a targeted cell depletion strategy integrated within an immunocompetent liver-on-a-chip platform. This approach not only enables the rapid identification of hepatotoxic determinants but also represents a significant advancement in predictive toxicology systems, while providing strategic insights for subsequent pathway analysis.

Results

Establishment of the immune- liver-on-a-chip platform

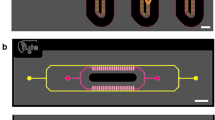

The immuno-liver chip was constructed by integrating immune components (T-cell and neutrophil systems) into a liver sinusoid chip optimized from our previous work24,25,26. The core structure retains the original tri-layer Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) design with dual porous membranes and perfusion channels (Fig. 1A). To accommodate immune cells, two lateral chambers (1.5 mm × 10 mm) were added to the upper layer for culturing T lymphocytes (left) and neutrophils (right). These chambers are interconnected with the central region via 20-μm-wide microbarriers to enable cellular communication and chemotaxis. The functional microfluidic interfaces (Fig. 1B) feature three parallel chambers: a central blood-polarity channel (1.5 mm × 15 mm) matching our previous liver sinusoid chip, flanked by immune cell chambers. These side chambers connect to 1.6-mm-diameter inlet/outlet ports through 500-μm-wide channels, fabricated using a 200-μm-height template.

A Illustrating the bioinspired liver sinusoid microenvironment and engineered chip design. Hepatic plates composed of hepatocytes are interspersed between sinusoidal capillaries containing immune cells. Polarized hepatocytes form bile canaliculi connected to bile ducts, while the perisinusoidal Space of Disse contains extracellular matrix and hepatic stellate cells. The chip replicates this architecture through three PDMS layers: a perfused top layer (featuring a central artificial blood channel flanked by immune cell chambers), a static middle layer (for hepatocyte culture), and a perfused bottom layer (for reverse-flow bile drainage). B Depicting functional microfluidic interfaces. The device incorporates inlet/outlet ports for blood and bile perfusion, cell-loading wells, and interlayer connectors. Perfusion media maintain cellular viability. C Demonstrating functional zonation mapping. The system establishes two dynamic processes: (1) physiological multicellular arrangement in liver sinusoids, and (2) chemokine-triggered recruitment of T cells and neutrophils through microfences into hepatic regions. This image and every element of this image was created by the authors.

The device comprises a vertical assembly of three patterned PDMS layers (Fig. 1C). The top layer contains two lateral chambers (for HuT-78 and HL-60 cells) connected by 20-μm-wide microchannels (1 mm length, 50 μm spacing) and a central perfusion channel for artificial liver blood. The middle layer houses a chamber for HepG2 cells, while the bottom layer features a perfusion channel for artificial bile flow directed opposite to the overlying blood flow. A Polycarbonate (PC) porous membrane between the top and middle layers supports EA.hy926 and U937 cells on its upper surface and LX-2 cells on its lower surface. A second PC membrane between the middle and bottom layers supports HepG2 cells on its top surface. After cell seeding, lateral ports were sealed, and bidirectional perfusion (1 μL min−1) was applied to the blood and biliary channels for co-culture. The entire device measures 3 cm × 5 cm × 1.5 cm (Supplementary Fig. S1). Minimal adsorption by the chip was confirmed for drug delivery and detection applications, ensuring detection accuracy (Supplementary Fig. S2). This liver chip integrates an artificial liver sinusoid and an immune system incorporating U937 Kupffer cells, HuT-78 T cells, and HL-60 neutrophils. Under xenobiotic stimulation, HuT 78 and HL-60 cells from the lateral chambers can migrate into the central artificial sinusoid via chemotaxis as part of the hepatotoxicity process.

Biological characterization and dynamic immune cell chemotaxis of the immune- liver-on-a-chip

We first evaluated the chip’s ability to simulate hepatic sinusoid physiology. In vivo, hepatocytes form complex polarized structures to facilitate substance transport between blood and bile. We characterized the polarization of 3D HepG2 clusters within the chip, focusing on multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) and bile salt export pump (BSEP) expressions. MRP2, localized at intercellular junctions with minor punctate cytoplasmic signals, while BSEP localized to the perinuclear membrane region, co-mediates toxic compound transport and bile secretion. Our analysis showed abundant MRP2 and BSEP expressions in the 3D HepG2 clusters (Fig. 2A). To assess bile acid dynamics, we perfused the upper channel with 2 μg mL−1 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CDFDA) (1 μL/min for 2 h) followed by standard medium. Retrieved HepG2 clusters exhibited canaliculus-like fluorescence at cell junctions (Fig. 2B), indicating CDFDA metabolism and apical transport. We quantified active transport using cholyl-lysyl-fluorescein (CLF), observing significant higher (p < 0.0001) accumulation in HepG2(+) bile channels versus HepG2(-) controls (Fig. 2C). This process was inhibited by 250 μM benzbromarone, confirming HepG2-dependent transport. These results demonstrate that the 3D HepG2 clusters in the chip recapitulate in vivo-like tissue architecture and drug metabolism capabilities, with distinct polarization characteristics.

A Fluorescence staining of MRP2 and BSEP in HepG2 cells. MRP2 (green) is primarily localized at intercellular junctions with minor punctate cytoplasmic signals. BSEP (red) shows no nuclear overlap (DAPI, blue) and localizes to the perinuclear membrane region. Scale bar: 50 μm. B Visualization of bile canaliculi formation via CDFDA metabolism: lactase-mediated conversion to fluorescent CDF and apical transport confirm functional tubule networks. Scale bar: 30 μm. C Hepatocyte transport activity quantification (n = 5). Using cholyl-lysyl-fluorescein (CLF, bile-analog substrate): HepG2(+) shows significantly higher fluorescence intensity than HepG2(−) (p < 0.0001); 250 μM benzbromarone (BEN) causes significant decrease (p < 0.05), Indicates active CLF transport to “artificial bile flow”. D HL-60 neutrophil chemotaxis toward fMLP gradients. Demonstrates migration into hepatocyte chambers. Scale bar: 10 μm. E Dose/time-dependent HL-60 recruitment (n = 5). Through microfabricated barriers in response to fMLP stimulation. Error bars represent the median ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA or Dunnett’s test was performed for analysis of multiple groups. Student’s t test was used to compare the two groups. P value < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***); p < 0.0001 (****); NS no significant difference.

We next evaluated immune responses through N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP)-stimulated HL-60 migration. HL-60 cell migration through microbarriers was quantified following stimulation with the chemotactic peptide fMLP (Fig. 2D). Our analysis revealed time- and concentration-dependent increases in HL-60 cell accumulation within microbarriers, with 0 nM fMLP serving as the negative control. As demonstrated in Fig. 2E, a 6-hour exposure to 100 nM fMLP induced an average of 7 HL-60 cells per microbarrier, representing a 7-fold increase compared to the control group (1 cell/microbarrier). These findings suggest that immune cells within the chip exhibit chemotaxis-directed migration toward hepatic zones, effectively recapitulating in vivo immune cell infiltration patterns during inflammatory processes. The observed migratory behavior validates the platform’s ability to model inflammation-mediated immune cell trafficking. Notably, the graded response to increasing fMLP concentrations and prolonged exposure durations mirrors physiological chemotaxis dynamics, thereby confirming the system’s capacity to process differential chemotactic signals (Supplementary Fig. S3). To characterize single-cell migration kinetics, real-time tracking of HL-60 cells was implemented during 100 nM fMLP stimulation over a 10-minute interval (Supplementary Fig. S4). Quantitative trajectory analysis demonstrated polarized cell movement from microbarrier entry points into the central channel, establishing definitive chemotactic responsiveness.

Biomechanical analysis of fluid dynamics inside the liver chip

To better understand and quantify fluid flow within the liver-on-a-chip system, a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model was constructed based on the chip geometry for numerical simulations (Fig. 3A). Numerical results demonstrate that the flow remains steady, with fluid velocities in the upper and lower channels significantly exceeding those in the middle channel. Velocity profiles in the upper and lower channels exhibit parabolic distributions, while streamlines align parallel to the channel substrates, originating from the inlet and terminating at the outlet (Fig. 3B). In contrast, fluid motion in the middle channel is driven by flows from the upper or lower channels penetrating through the porous PC membranes. The larger viscous forces near the inlet regions of the upper and lower channels induce transverse flow within the middle channel toward the opposing side. This convective mechanism generates weak recirculation patterns in the central region of the middle microchannel (Fig. 3C). Velocity components along (x-direction) and perpendicular to (y-direction) the flow were calculated to characterize flow field evolution. At positions closer to the inlet, x-direction velocities peak and display axisymmetric profiles (Fig. 3C), indicating enhanced seepage velocity near the porous membranes at the channel periphery. Conversely, y-direction velocities follow analogous trends but evolve inversely (Fig. 3D). These analyses provide critical insights into the internal flow field topology of the chip, which is essential for understanding mass transfer under dynamic fluid conditions.

A Geometry of the computational model (not proportional to the actual size). B Flow field and stream line distribution in microchannels. C, D The x-direction and y-direction velocity along the chip at 100 μm below the membrane. E Shear stress distribution perpendicular to the flow velocity. F Mean shear stress of membrane surface at different flow rates. This image and every element of this image was created by the authors.

Subsequently, we calculated the shear stress distribution perpendicular to the flow interface (Fig. 3E). In the upper and lower microchannels, pronounced shear stress distributions were observed near the walls due to wall-induced resistance effects. However, in the middle channel, negligible shear stress was detected owing to the substantially lower flow velocities. A systematic quantification of the average stress across the membrane surfaces revealed a linear correlation with the channel flow velocity (Fig. 3F), providing critical guidance for selecting optimal operational parameters in practical applications.

Targeted cellular depletion strategy for detecting drug-induced hepatotoxicity heterogeneity

Building upon this immune-liver-chip platform, we developed a targeted cellular depletion strategy to rapidly identify drug-induced hepatotoxicity heterogeneity. Inspired by gene knockout technology, this approach was adapted for functional characterization of specific cellular components rather than genes or signaling pathways. Cell-type-specific liver chips were generated by omitting target cells during assembly, and toxicity changes were assessed by comparing depleted versus intact systems (Fig. 4A). Specifically, we sequentially depleted individual components of the immuno-liver-chip to generate four functionally impaired models: (i) bile transport-blockaded, (ii) stellate cell-depleted, (iii) Kupffer cell-depleted, and (iv) T lymphocyte-depleted. Using these modified platforms alongside the intact immune-competent chip as a control, we systematically investigated hepatotoxicity mechanisms of four clinical drugs: APAP, EE, SMX, and ABC. These compounds were selected based on their well-established liver injury mechanisms in clinical practice, which involve distinct processes including hepatocyte damage, cholestasis, and immune activation. Testing drugs with clearly defined toxicity mechanisms enabled direct evaluation of the chip’s capability in toxicity assessment.

A Targeted depletion methodology. Cell-type-specific liver chips were generated by omitting target cells during assembly. Example: For T cell-depleted chips, T cell-free culture media were used during assembly. Toxicity changes are assessed by comparing depleted vs. intact systems. B Dose-dependent LDH secretion in response to acetaminophen (APAP), ethinyl estradiol (EE), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and abacavir (ABC) on multi cell-depleted liver chips. LDH release increased dose-dependently in all chip models following treatment with APAP, EE, SMX, or ABC (n = 6). This aligns with the established dose-response relationship of drug-induced liver injury. Error bars represent the median ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA or Dunnett’s test was performed for analysis of multiple groups. Student’s t test was used to compare the two groups. P value < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***); p < 0.0001 (****); NS no significant difference. This image and every element of this image was created by the authors.

Comparative analysis of Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) release levels across the five models revealed the critical role of specific cellular components in drug-specific hepatotoxicity. As shown in Fig. 4B, dose-dependent LDH secretion in response to APAP, EE, SMX, and ABC was observed across the multi cell-depleted liver chips, consistent with established dose-response relationships for drug-induced liver injury. Divergent hepatotoxicity profiles across experimental platforms were also observed. Notably, toxicity results for each drug consistently differed between deficient models and intact immune-competent chips, though the magnitude of changes varied. This confirms that diverse hepatic cell populations collectively mediate toxicological outcomes in the immune-competent liver chip. Furthermore, due to the relatively weak immune activity of HuT 78 and HL-60 cells, and because LDH release does not comprehensively reflect hepatotoxicity, we conducted parallel experiments using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) instead of the chip’s immune components (Supplementary Fig. S5). As expected, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) secretion levels in all chip models also showed dose-dependent increases. This strategy of using deficient liver chip models not only enables rapid identification of key hepatotoxicity factors but also provides critical guidance for subsequent mechanistic elucidation.

Cell-type-specific heterogeneity of drug-induced hepatotoxicity

We then analyzed the test results of these four drugs across different liver-on-a-chip models to reveal their differences in liver toxicity. First, we plotted heat maps of hepatotoxicity for these four drugs in different models (Fig. 5A). We found that the four drugs showed significant consistency in the release of toxicity indicators LDH and ALT, indicating the feasibility of using LDH and ALT as liver toxicity detection indicators. Interestingly, we found that SMX and ABC have more similar toxicity profiles, while APAP shows significant toxicity differences from other drugs. This might relate to the fact that hepatotoxicity of SMX and ABC tends to be immune-mediated, whereas APAP is mainly mediated by hepatocyte damage.

A Comparative toxicity analysis across depletion models. Heat map showing toxicity profiles of acetaminophen (APAP), ethinyl estradiol (EE), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and abacavir (ABC) in: Intact: Full cell complement; N-S: stellate cell-depleted; N-B: bile transport-blockaded; N-K: Kupffer cell-depleted; N-T: T lymphocyte-depleted. Color coding: blue = LDH release; red = ALT release. B, C Model-specific toxicity changes (LDH/ALT): APAP: No significant inter-model variation; EE: ↑14.8% (p < 0.0001) in LDH and ↑24.2% (p < 0.0001) in ALT toxicity enhancement in bile transport blockade model; SMX: Toxicity reduction in Kupffer cell-depleted (LDH: ↓16.9%, p < 0.0001; ALT: ↓8.2%, p < 0.01) and T lymphocyte-depleted models (LDH: ↓13.1%; p < 0.0001; ALT: ↓8.3%, p < 0.01); ABC: ↓7.7% (LDH) and ↓21.8% (ALT) toxicity reduction in T lymphocyte-depleted model (p < 0.001) (n = 6 and n = 4). Error bars represent the median ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA or Dunnett’s test was performed for analysis of multiple groups. Student’s t test was used to compare the two groups. P value < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***); p < 0.0001 (****); NS no significant difference.

To further identify the hepatotoxic determinants of each drug, we plotted model-specific toxicity histograms. From these (Fig. 5B and C for LDH and ALT, respectively): For APAP, we observed no significant differences in dose-dependent LDH release curves between the four depleted models and the intact immune-competent liver-on-a-chip under identical exposure conditions. This indicates that Kupffer cell, stellate cell, or T lymphocyte depletion, as well as bile duct obstruction, did not markedly affect APAP-induced hepatotoxicity, consistent with its known mechanism where reactive metabolites directly damage hepatocytes. For EE, the bile transport-blockaded model exhibited substantially elevated hepatotoxicity (14.8% increase in LDH (p < 0.0001) and 24.2% increase in ALT (p < 0.0001) versus the intact model), while other depleted models (T lymphocyte-, stellate cell-, or Kupffer cell-depleted) showed negligible variation. This suggests a synergistic toxic interaction between bile accumulation from cholestasis and EE, though we acknowledge the precise mechanism remains undetermined due to current limitations in cholestatic hepatotoxicity models. While we cannot conclusively determine whether bile components exacerbate EE toxicity or vice versa, our findings align with clinical evidence of EE-induced hepatotoxicity through cholestasis. For SMX, we detected markedly reduced hepatotoxicity in Kupffer cell-depleted models (LDH: ↓16.9%, p < 0.0001; ALT: ↓8.2%, p < 0.01) and T lymphocyte-depleted models (LDH: ↓13.1%, p < 0.0001; ALT: ↓8.3%, p < 0.01) compared to the intact model, with minimal changes (p > 0.05) in stellate cell-depleted or bile transport-blockaded models. These results support reported mechanisms of SMX-induced immune-mediated hepatotoxicity. For ABC, while sharing similarities with SMX, we identified distinct hepatotoxic mechanisms. Our data demonstrate that T lymphocyte depletion significantly attenuated ABC-induced hepatotoxicity (LDH: ↓7.7%, p < 0.001; ALT: ↓21.8%, p < 0.001), whereas Kupffer cell depletion had negligible effects. This corresponds to ABC’s mechanism involving covalent binding to hepatocyte HLA domains that triggers T cell-mediated immune attacks, conclusively establishing its T cell-dependent hepatotoxicity.

To further validate the resolution of immune-dependent toxicity through targeted cellular depletion within our immune-liver-chip platform, we tested ALP (a known immune-mediated DILI drug) (Supplementary Fig. S6). As expected, allopurinol-induced toxicity was significantly attenuated in the Kupffer cell-depleted configuration. This reduction aligns with clinically observed immune-mediated liver toxicity and demonstrates our system’s capability to discern immune-specific mechanisms, thereby strengthening the mechanistic validation of our approach.

Discussion

Drug-induced hepatotoxicity remains a primary cause of pharmaceutical withdrawal throughout drug development stages, from preclinical testing to post-marketing surveillance36,37. Given that each compound exhibits distinct hepatotoxic mechanisms, elucidating these pathways serves multiple critical purposes: informing clinical decision-making for drug/dose selection, preventing severe liver injury, guiding structural optimization to mitigate toxicity risks, and identifying therapeutic interventions. Preclinical identification of hepatotoxic mechanisms not only enhances safety assessment but also reduces developmental costs, particularly crucial as drug-induced liver injuries have incurred huge direct economic losses2. Current reliance on extensive experimental testing for mechanistic identification, however, creates a resource-intensive bottleneck. This often forces preclinical studies to prioritize limited “critical” experiments for accelerated drug development, inadvertently increasing clinical trial risks. Consequently, developing efficient preclinical strategies for hepatotoxicity mechanism identification becomes imperative.

Over the past decade, liver-on-a-chip technology has evolved to incorporate multicellular systems, perfusion, and 3D culture methods, creating increasingly anatomically, physiologically, and functionally realistic liver chips24,25,26,38. These platforms have consequently emerged as promising candidates for drug screening. However, the liver contains not only parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells but also diverse immune cell types, making the construction of liver chips incorporating relevant immune microenvironments an ongoing challenge. For example, Takeda Pharmaceuticals’ GPR40 agonist TAK-875 was withdrawn globally following phase III clinical trials due to unpredictable, dose-independent liver injury39. Conventional preclinical models often fail to detect such immune-mediated liver toxicity, suggesting that assessment using immune-competent liver chips could provide a valuable solution. In another case, the JNJ-1 demonstrated an endotoxin-driven, macrophage-dependent liver toxicity mechanism. Consequently, immune modulation strategies such as Kupffer cell depletion significantly increased its hepatotoxic risk. Additionally, although some studies have begun exploring immune-integrated liver chips, significant heterogeneity exists in hepatotoxicity mechanisms across different drugs, and how specific hepatic cell types influence drug-induced hepatotoxicity remains poorly understood.

To address these challenges, we engineered an immune-competent liver-on-a-chip platform by integrating HuT-78 T-lymphocytic and HL-60 granulocytic leukemia cells into a hepatic sinusoid chip. This system successfully recapitulates immune cell migration and stress responses under chemokine induction. We performed CFD simulations to analyze flow patterns, pressure distribution, and cellular shear stress profiles, ensuring the physiological relevance of the chip microenvironment. Building upon this platform, we propose a “targeted cellular depletion” strategy to systematically eliminate specific cell populations and dissect their contributions to drug toxicity. Using APAP, SMX, EE, and ABC as model compounds, comparative assessments between cell-depleted chips and the full immune-liver chip revealed cell-type-specific toxicological dependencies. Our findings demonstrate that different hepatic cell populations collectively mediate toxicological outcomes, and that different drugs exhibit significant differences in their mechanisms of causing liver toxicity. For example, comparing APAP and SMX revealed significant differences in their toxicity profiles. APAP induced significant hepatotoxicity across all chip models, with no significant difference in toxicity degree among them. This suggests APAP primarily causes hepatocyte apoptosis with relatively minimal involvement of non-parenchymal cells. In contrast, SMX toxicity was significantly reduced in models lacking hepatocytes or T cells. This indicates that SMX likely causes liver damage largely by triggering an immune response. These findings highlight our strategy’s utility in accelerating mechanistic identification during preclinical drug safety evaluation, which could not be readily distinguished using previous methods. Furthermore, the targeted cellular depletion strategy within our immune-liver-on-a-chip platform not only enables rapid identification of hepatotoxic determinants but also represents a significant advancement in predictive toxicology systems. Additionally, it provides strategic insights for subsequent pathway analysis.

Moreover, the targeted depletion strategy capitalizes on precise microenvironment manipulation in biomimetic organ chips to isolate specific cellular roles within complex pharmacological processes. Beyond hepatotoxicity assessment, this approach holds transformative potential for investigating cell-cell communication across organ chip systems. By observing physiological changes upon selective cell removal, we can systematically map intercellular networks in human-relevant models. As organ chip technology advances toward higher biological fidelity, future applications could include gene-edited organ models and multi-organ systems with targeted deletions (e.g., thymus-deficient body-on-a-chip), potentially accelerating breakthroughs in drug development and precision medicine.

However, there are also several technical limitations worth discussing. The primary drawback of this study is the use of cell lines rather than primary cells for chip construction, which limits physiological relevance. Cell lines cannot match primary cells in many aspects; for instance, HepG2 cells exhibit significantly reduced metabolic and detoxification capabilities. Cell lines are typically homogeneous monoclonal populations with low heterogeneity, unable to reflect the diverse cell types within tissues. Additionally, batch variations introduce further uncertainty regarding their effects on experimental outcomes. Utilizing primary hepatocytes and immune cells would yield more accurate results. The bile excretion system in our designed liver chip is relatively rudimentary. Incorporating cholangiocytes to establish functional bile duct units would more accurately model complete biliary transport pathways and better represent phenomena like drug-induced cholestasis involving bile accumulation. The chip’s throughput is relatively low, and its operation is complex. Further development should couple the chip with automated liquid handling systems (e.g., robotic pipettors) for cell seeding, medium changes, and compound dosing to enhance efficiency and reproducibility. Furthermore, integrated online monitoring, utilizing embedded optical sensors for key metabolites (glucose, lactate, urea) and liver-specific biomarkers (e.g., alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase via fluorogenic substrates), alongside compatibility with automated high-content imaging systems would enable real-time, non-destructive assessment of cell morphology, viability, and functional endpoints. These improvements would facilitate rapid integration of the liver chip into pharmaceutical industry workflows.

In summary, this work establishes a high-mimetic immune-liver-on-a-chip platform and demonstrates the utility of cellular depletion strategies for mechanism-driven toxicity assessment. As a proof-of-principle, our methodology enables rapid identification of critical hepatotoxic factors while providing mechanistic insights to guide subsequent investigations. The modular nature of this approach promises broad applicability in toxicological research and beyond, particularly as organ chip systems evolve to better recapitulate human physiology.

Methods

Cell culture

The human cell lines HepG2, LX-2, EA.hy926, U937, HuT-78, and HL-60 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, United States). HepG2 hepatocytes were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (HyClone™) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco™), 1× non-essential amino acids (Gibco™), and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U mL⁻¹ each) under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂), with medium replacement every 48 h. LX-2 hepatic stellate cells, EA.hy926 endothelial cells, and U937 monocytes, modeling hepatic stellate, liver sinusoidal endothelial, and Kupffer cell functions, respectively, were maintained in DME/F-12 (1:1) medium (HyClone™) containing equivalent serum and antibiotic concentrations. Immune cell lines HuT-78 (T lymphocytic leukemia) and HL-60 (myeloid leukemia) were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 20% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, respectively. All cell lines were subcultured twice daily using either 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (HepG2, LX-2, EA.hy926, HuT-78, HL-60) or centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min (U937). These cells were chosen based on their sufficient phenotypes relevant to hepatotoxicity and high-quality control standards, resulting in experiments that were more reproducible.

Fabrication of liver chip

The microfluidic chip was constructed through integration of two polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) structural frames, three PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) layers fabricated via SU8-3035 photolithography (Microchem Corp.), and two long polycarbonate membranes (1-μm pore). Prior to assembly, PDMS components underwent oxygen plasma activation (Harrick Plasma, 100 W, 1 min) to enhance surface biocompatibility. Cellular components were prepared as follows: EA.hy926 endothelial cells and LX-2 hepatic stellate cells were cultured to 80% confluence on PC membranes under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂), while U937 monocytes were differentiated into macrophages using 50 ng mL⁻¹ PMA (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI-1640 medium over 48 hr. HepG2 hepatocytes were suspended in ice-cold growth factor-reduced Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences) at 1 × 10⁷ cells mL⁻¹ (1:1 v/v ratio). Device assembly involved sequential stacking of cell-seeded membranes with sterilized PDMS layers to establish tri-chamber architecture, followed by injection of 20 μL HepG2/Matrigel mixture into the central chamber and U937 monocytes into the top chamber. HuT-78 and HL-60 cells were syringe-inoculated via designated ports, immediately sealed with plugs. The complete 5 × 3 × 1.5 cm device was secured with M3 stainless steel screws and integrated with a Watson Marlow 205S/CA12 peristaltic pump, establishing continuous perfusion (1 μL min⁻¹) of DMEM/HG medium (HyClone™) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco™), 1× NEAA, and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U mL⁻¹ each). Fluid dynamics featured laminar flow through microchannels, with trans-membrane diffusion enabled by the porous PC membranes, creating a physiologically relevant recirculation system maintained for 72 h under controlled culture conditions.

Polarization of HepG2 and visualization of bile canaliculus

Bile canalicular networks were fluorescently labeled with 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (CF) following 3-h perfusion of microfluidic devices with artificial blood containing 2 μg mL−1 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (CDFDA) and subsequent disassembly. Three-dimensional HepG2 cell/basement membrane extract (BME) constructs were prepared through PBS washing (×3), 1-hour culture in complete medium, and fluorescence microscopy imaging. For functional quantification, complete HepG2 models (HepG2+) and HepG2-deficient controls (HepG2−) were incubated with 2 μM cholyl-lysyl-fluorescein (CLF) ± 250 μM benzbromarone (BEN), a multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) inhibitor40, followed by microplate reader measurement of artificial bile fluorescence at 485 nm excitation/520 nm emission.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis of the flow field in the liver chip

A three-dimensional computational model was developed using COMSOL Multiphysics® software to analyze the flow fields within multiple microfluidic channels of the liver-on-a-chip system. Owing to the periodicity of the model, a quarter-symmetry computational domain was adopted to minimize computational costs. During the computation of the flow field within the microchips, we adopted the assumption that the fluid behaves as an incompressible Newtonian fluid under steady-state conditions. The dynamics of the fluid were governed by the continuity equation and the Navier–Stokes (N-S) equation, as shown in Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

Where \(\overrightarrow{{U}}\) is the flow velocity vector, ρ is the buffer density, P is the pressure, \({\xi }\,\) is the fluid viscosity. Here ρ is 1 × 103 kg m−3 and is 1 × 10−3 Pa s.

Porous media assumptions were implemented to simulate the two porous membranes. The void fraction \(\chi\) was determined by the following equation:

Where d is the pore diameter, and ρ0 denotes the pore density. Since the flow within the chip can be modeled as laminar flow through a packed bed, the pressure drop is linearly proportional to the velocity, while the inertial resistance term is negligible. By neglecting convective acceleration and diffusion effects, the governing equations satisfy Darcy’s law:

Where \(\delta\) represents the permeability. When simulating laminar flow through a packed bed, the semi-empirical Blake-Kozeny equation—applicable across a wide range of Reynolds numbers—is employed:

where L is the packed bed thickness, DP is the average particle diameter, and U∞ represents the far-field velocity. By comparing Eqs. (4) and (5), the permeability \(\delta\) can be derived as follows:

Since Eq. (6) is a semi-empirical formulation and the porosity of the PC membrane cannot be experimentally determined, we first calculated the theoretical permeability using Eq. (6) and subsequently calibrated the permeability to 2.5 × 10⁻¹⁶ m⁻² to align with experimental constraints41.

To solve the above control equation, we set the following boundary conditions: at the inlet position, the fully developed flow was applied, and its flow rate was 1 μL min⁻¹; at the outlet position, the pressure was set to zero; in the middle of the model, a symmetrical boundary condition was used. The numerical model was solved using the laminar flow module in COMSOL, with a porous medium domain incorporated to represent the PC membrane. The relative tolerance of the steady-state solver was set to 1 × 10−3. The characterization and processing of simulation results such as flow fields were implemented in the COMSOL post-processing module.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) cytotoxicity assessments

Effluent from the blood-mimetic channel was analyzed for: (1) cytotoxicity via lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release using the CytoTox 96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, USA), and (2) hepatotoxicity through alanine aminotransferase (ALT) quantification with a commercial kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), according to manufacturers’ protocols; absorbances at 490 nm and 340 nm were measured on a unified microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x, Molecular Devices), with both analyte concentrations derived from standard calibration curves.

Targeted cell-depletion liver chip and cell-type-specific hepatotoxic responses assessment

The targeted cell-depletion liver chip was constructed by eliminating target cells during assembly, meaning it was assembled using a medium lacking the targeted cells. Specifically, for the Kupffer cell-depleted liver chip, after preparing all cell types in advance, device assembly involved sequential stacking of cell-seeded membranes with sterilized PDMS layers to establish the tri-chamber architecture. This was followed by injection of 20 μL HepG2/Matrigel mixture into the central chamber and U937 cell culture medium (without U937 monocytes) into the top chamber. HuT-78 and HL-60 cells were then syringe-inoculated through designated ports and immediately sealed with plugs. Using the same method, stellate cell-depleted and T lymphocyte-depleted chips were fabricated by replacing the corresponding targeted cells with cell-free medium. Separately, the bile transport-blocked model was fabricated by substituting a non-porous polycarbonate membrane for the bottom porous membrane. Pharmaceutical candidates’ hepatotoxic profiles were assessed using the targeted cell-depletion liver chips, with the intact liver chip serving as a control. Cell-type-specific hepatotoxic responses were identified by comparing the hepatotoxicity measured in the depleted liver chips against the control, indicating whether the depleted cell population played a key role in the drug’s hepatotoxic process.

Immune cell migration assay

Following microfluidic device assembly, the upper blood-mimetic channel was perfused with culture medium (DMEM-HG [Hyclone] containing 10% FBS [Gibco™], 1% non-essential amino acids [NEAA; Gibco], 100 U mL-1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL-1 streptomycin) supplemented with graded concentrations of N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP; chemoattractant). HL-60 cell migration was quantified by enumerating cells within predefined microfluidic compartments using automated image analysis.

Immunofluorescence protocol

Cells underwent sequential processing: three 5-min phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washes, 10-min fixation with ice-cold methanol, permeabilization with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min and blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST). Primary antibodies against MRP2 (ab221547, Abcam) or BSEP (67512-1-Ig, Proteintech) were applied overnight at 4 °C, followed by 2-h incubation with Alexa Fluor®-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; Abcam) at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg mL−1 DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min.

Whole blood sample collection and PBMCs isolation

Whole blood samples were obtained from the Qingdao Central Hospital of the University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. The Ethics Committee of the University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences approved the collection and use of human samples. In all cases, samples were deidentified prior to use in our study. PBMCs were isolated through density gradient centrifugation using lymphocyte separation solution. The detailed procedure was as follows: Whole blood was carefully added to centrifuge tubes containing the separation solution and centrifuged at 500 × g for 25 min. After centrifugation, the opaque white ring at the interface (mononuclear cell layer) was collected, washed three times with PBS, and resuspended in culture medium.

Quantitative imaging

Fluorescence imaging was performed using an IX71 inverted epifluorescence microscope (Olympus) with a mercury lamp and 20×/0.75 NA objective. ImageJ v1.53 (NIH) facilitated image quantification.

Statistics and reproducibility

The sample size (N, representing biological replicates per group) is provided in all figure legends. For key experiments, independent replication was performed a minimum of three times. Statistics were performed on GraphPad Prism 8.3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical differences between groups were determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. Student’s t test was used to compare the two groups. The data are presented as the mean ± standard error of three independent replicates’ mean (SEM). Statistical significance: P value < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***); p < 0.0001 (****); NS no significant difference.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All relevant data are included in the manuscript or the Supporting Information. Numerical source data for graphs and charts are provided in Supplementary Data 1, and data for computational fluid dynamics analysis are available in Supplementary Data 2. All other data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vernetti, L. A. et al. Evolution of experimental models of the liver to predict human drug hepatotoxicity and efficacy. Clin. Liver Dis. 21, 197–214 (2017).

Reuben, A., Koch, D. G. & Lee, W. M. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology 52, 2065–2076 (2010).

Suda, T. et al. Quantitation of telomerase activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: a possible aid for a prediction of recurrent diseases in the remnant liver. Hepatology 27, 402–406 (1998).

Shimamura, M. & Ohta, S. Germ-line transcription of the T cell receptor δ gene in mouse hematopoietic cell lines. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 1541–1546 (1995).

Shafritz, D. A. et al. Liver stem cells and prospects for liver reconstitution by transplanted cells. Hepatology 43, s89–s98 (2006).

Kwon, S. J. et al. High-throughput and combinatorial gene expression on a chip for metabolism-induced toxicology screening. Nat. Commun. 5, 3739 (2014).

Yu, K. et al. Prediction of metabolism-induced hepatotoxicity on three-dimensional hepatic cell culture and enzyme microarrays. Arch. Toxicol. 92, 1295–1310 (2018).

Zhuo, Y. et al. Strategy for hepatotoxicity prediction induced by drug reactive metabolites using human liver microsome and online 2D-Nano-LC-MS analysis. Anal. Chem. 89, 13167–13175 (2017).

Weng, Y. et al. Scaffold-free liver-on-a-chip with multiscale organotypic cultures. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701545 (2017).

Qu, Y. et al. A nephron model for study of drug-induced acute kidney injury and assessment of drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Biomaterials 155, 41–53 (2018).

Musah, S. et al. Mature induced-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived human podocytes reconstitute kidney glomerular-capillary-wall function on a chip. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0069 (2017).

Wang, P. et al. Blood-brain barrier injury and neuroinflammation induced by SARS-CoV-2 in a lung-brain microphysiological system. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 1053–1068 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Assessment of air pollutant PM2.5 pulmonary exposure using a 3D lung-on-chip model. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6, 3081–3090 (2020).

Haan, P. D. et al. Digestion-on-a-chip: a continuous-flow modular microsystem recreating enzymatic digestion in the gastrointestinal tract. Lab. Chip 19, 1599–1609 (2019).

Jalili-Firoozinezhad, S. et al. A complex human gut microbiome cultured in an anaerobic intestine-on-a-chip. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3, 520–531 (2019).

Lyu, Z. et al. A neurovascular-unit-on-a-chip for the evaluation of the restorative potential of stem cell therapies for ischaemic stroke. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 847–863 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Multiscale brain research on a microfluidic chip. Lab. Chip 20, 1531–1543 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Continuous contractile force and electrical signal recordings of 3D cardiac tissue utilizing conductive hydrogel pillars on a chip. Mater. Today Bio. 20, 100626 (2023).

Lee, J. et al. A heart-breast cancer-on-a-chip platform for disease modeling and monitoring of cardiotoxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. Small 17, 2004258 (2021).

Mori, N., Morimoto, Y. & Takeuchi, S. Skin integrated with perfusable vascular channels on a chip. Biomaterials 116, 48–56 (2017).

Lee, S. et al. Construction of 3D multicellular microfluidic chip for an in vitro skin model. Biomed. Microdevices 19, 22 (2017).

Buntz, B. Drug Discovery & Development. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/nih-announces-end-to-funding-for-animal-only-studies/ (2025).

Zushin, P. et al. FDA Modernization Act 2.0: transitioning beyond animal models with human cells, organoids, and AI/ML-based approaches. J. Clin. Invest 133, e175824 (2023).

Deng, J. et al. A liver-chip-based alcoholic liver disease model featuring multi-non-parenchymal cells. Biomed. Microdevices 21, 57 (2019).

Deng, J. et al. A cell lines derived microfluidic liver model for investigation of hepatotoxicity induced by drug-drug interaction. Biomicrofluidics 13, 024101 (2019).

Deng, J. et al. A liver-on-a-chip for hepatoprotective activity assessment. Biomicrofluidics 14, 064107 (2020).

Corrado, B. et al. A three-dimensional microfluidized liver system to assess hepatic drug metabolism and hepatotoxicity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 116, 1152–1163 (2019).

Dey, S. et al. Microfluidic human physiomimetic liver model as a screening platform for drug induced liver injury. Biomaterials 310, 122627 (2024).

Cho, H. J. et al. Bioengineered multicellular liver microtissues for modeling advanced hepatic fibrosis driven through non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Small 17, e2007425 (2021).

Pyzik, M. et al. Hepatic FcRn regulates albumin homeostasis and susceptibility to liver injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 114, E2862–E2871 (2017).

Ju, C. & Reilly, T. Role of immune reactions in drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Drug Metab. Rev. 44, 107–115 (2012).

Deng, J. et al. Mapping secretome-mediated interaction between paired neuron-macrophage single cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200944119 (2022).

Deng, J. et al. Dissecting cellular diversity in paracrine signaling with single-cell secretion profiling. ACS Sens. 10, 5714–5723 (2025).

Deng, Q. et al. Assessing immune hepatotoxicity of troglitazone with a versatile liver-immune-microphysiological-system. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1335836 (2024).

Deng, Q. et al. An immune-liver microphysiological system method for evaluation and quality control of hepatotoxicity induced by polygonum multiflorum thunb. extract. J. Ethnopharmaco. 345, 119633 (2025).

Mosedale, M. & Watkins, P. B. Drug-induced liver injury: advances in mechanistic understanding that will inform risk management. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 101, 469–480 (2017).

Lauschke, V. M. et al. Novel 3D culture systems for studies of human liver function and assessments of the hepatotoxicity of drugs and drug candidates. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 1936–1955 (2016).

Deng, J. et al. Engineered liver-on-a-chip platform to mimic liver functions and its biomedical applications: a review. Micromachines 10, 676 (2019).

Marcinak, J. F. et al. Liver safety of fasiglifam (TAK-875) in patients with type 2 diabetes: review of the global clinical trial experience. Drug Saf. 41, 625–640 (2018).

Saab, L. et al. Implication of hepatic transporters (MDR1 and MRP2) in inflammation-associated idiosyncratic drug-induced hepatotoxicity investigated by microvolume cytometry. Cytom. Part A. 83, 403–408 (2013).

Du, Y. et al. Mimicking liver sinusoidal structures and functions using a 3D-configured microfluidic chip. Lab. Chip 17, 782–794 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82201638), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant Nos. ZR2024QH638, ZR2025MS827 and ZR2024QE212), Shandong Youth Innovation and Technology Support Program (Grant No. 2024KJJ040), and the Qingdao Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 24-4-4-zrjj-99-jch).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Yuan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing-original draft. P.Z.: Formal analysis, Investigation. S.Yang: Data curation, Formal analysis. J.C.: Data curation, Investigation. X.M.: Data curation, Investigation. C.W.: Conceptualization. J.D.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-original draft & editing. All authors reviewed and agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Ophelia Bu. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, S., Zhang, P., Yang, S. et al. Targeted cellular depletion in an immune-liver-on-a-chip platform elucidates cell-type-specific heterogeneity in drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Commun Biol 8, 1560 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08928-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08928-6