Abstract

Iron plays a vital role in early brain development, supporting critical processes such as myelination, dendritogenesis, and neurotransmitter synthesis. The perinatal period marks a crucial transition from the intrauterine to the extrauterine environment, requiring significant brain adaptation to new stimuli and metabolic demands. However, tight spatiotemporal resolution capturing the timing and sequence of brain iron changes surrounding this critical transition has yet to be achieved. Leveraging a longitudinal perinatal cohort with 147 multi-echo MRI scans spanning from 25 to 60 post-conceptual gestational weeks, we mapped brain iron growth trajectories with R2* estimation across fetal, newborn and neonatal periods. We also examined whether sex, gestational age at birth, and birth weight influence R2* developmental trajectories. We found that parietal and superior temporal regions predominately show linear growth trajectories throughout the perinatal period across birth, while the occipital cortex, the temporal pole, inferior temporal regions and a subset of frontal regions exhibit non-linear trends. For most of the non-linear trajectories, growth rates peak around 40 weeks, highlighting the critical window of birth transition for brain R2* change. These results provide the first longitudinal insights into R2* development across birth, uncovering distinct regional growth patterns that may align with different phases of neurodevelopment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bioavailability of iron in early human brain development is crucial for supporting the rapid brain growth, even before birth1,2. Key neurodevelopmental processes, including myelination, dendritogenesis, synaptogenesis, and neurotransmission, rely heavily on iron-containing enzymes and hemoproteins3,4,5. In humans, iron deficiency during infancy, or being born to a mother with maternal iron deficiency, is associated with lower sensori-motor, cognitive/language, and social-emotional functions6,7,8,9,10. Early iron deficiency also increases the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, and schizophrenia11,12,13. Unfortunately, post-hoc diet interventions are not consistently effective in preventing neurological deficits resulting from early iron deficiency14,15. Thus, understanding iron development during fetal and neonatal development is important for promoting optimal developmental outcomes. Most existing evidence relies on measurements of serum ferritin, a marker of the body’s iron stores that reflects the amount of iron bound to the protein ferritin. However, only a few studies have examined iron concentrations in the brain during early development. A basic principle of iron biology is that iron is prioritized by red blood cells for hemoglobin synthesis over other organs, including the brain16. Thus, the brain may still be at risk even when iron deficiency or anemia is not evident in standard blood tests17,18. Despite the critical role of iron in early brain development and its direct relevance to long-term neuropsychological health, our understanding of fetal and infant brain iron dynamics remains limited.

Iron may also play a critical role in the transformative event of birth, which is a profound neuroplastic transition. During the transition to extrauterine life, the brain experiences a shift from the sensory input and physiological support of the uterine environment to a world with a vastly expanded sensory repertoire and altered physiological conditions19,20. At the same time, circulatory pathways also change, with the lungs and other organs taking over from the placenta. This circulatory transition disrupts placental iron supply, forcing the newborn to rely on iron stores accumulated during the fetal period—a critical resource for sustaining the brain’s rapid developmental processes. From the late fetal stage through the first few weeks of life, the brain undergoes intensive histogenetic processes that involve iron, including neural aggregation and cytoarchitecture formation, axonal growth and dendritic differentiation, a massive burst of synaptogenesis, and the initiation of myelination in primary cortical areas around the central sulcus2,21,22. This surge in histogenetic activity has been reflected in results from infant in vivo metabolic Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional connectivity imaging. PET studies show that infants under 5 weeks of age exhibit the highest glucose uptake in the sensorimotor cortex, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellar vermis23. A recent study by our group revealed a dramatic increase in functional connectivity at birth within the subcortical network, with the occipital-cerebellum network, between the bilateral sensorimotor networks, and between the bilateral temporal networks24. All of these neurodevelopmental processes require the involvement of iron. However, open questions for the field include how iron levels change in the brain during these processes, whether there is a shift in iron availability that coincides with the event of birth, and whether brain iron development varies over time and across different brain areas.

In this study, we leverage an existing perinatal longitudinal multi-echo (ME) functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) dataset spanning 25–60 post-conceptual gestational weeks, aiming to map the developmental trajectory of brain iron levels inclusive of the birth transition. Our recent work has refined the methodology for assessing iron using ME fMRI data, specifically adapted for fetal and infant brains25,26. This methodology assesses brain iron based on the transverse relaxation rate R2* (1/T2*), a well-established correlate of brain iron levels27,28. It is important to note that, although the current work is motivated by the study of brain iron development and R2* is proportional to iron29, R2* changes are influenced by other factors, including myelin, blood vessels, and local structural orientation30, especially in the fetal brain where total iron levels are relatively low. Nevertheless, documenting R2* changes remains valuable in neurodevelopmental research, as it inform on cortical structural and chemical composition, even if it is not a specific marker of iron.

We hypothesize that R2* developmental trajectories will exhibit regional variation, as the timing of histogenetic processes and functional development differ across brain regions. Specifically, we anticipate significant R2* increase throughout the birth transition in primary cortices such as the visual, auditory, and sensorimotor regions, reflecting the brain’s preparation for external stimuli before birth and its adaptation afterward. In contrast, we infer frontal regions to show relatively lower R2* levels or slower accumulation, as neural processes like synaptogenesis progress more slowly in the frontal lobe and do not peak until well after the first year of life21. Additionally, we investigate the effects of sex and birth outcomes, including gestational age (GA) and weight at birth, on brain R2* development during this critical window. This is driven by documented sex differences in plasma ferritin levels and the prevalence of iron deficiency in infants31,32, as well as the association between maternal prenatal anemia and an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes33.

Results

Sample characteristics

Eighty-five fetal brain scans (post-conceptual GA: 30.99 ± 4.15 weeks) and 62 infant brain scans (post-conceptual GA: 48.33 ± 4.14 weeks) from 73 unique participants are included in the present analysis. Table 1 enumerates study sample demographic data. A lollipop plot for scan ages is provided in Fig. 1. All MRI data were acquired with ME Echo-planar imaging (EPI) on a single Siemens Verio 3T system between 2013 and 2018, as part of the Perinatal Imaging of Neural Connectivity (PINC) project at Wayne State University (WSU)34. Eligibility criteria included singleton pregnancy, maternal age 18 to 40, no suspected central nervous system abnormality as determined by 20-week ultrasound, and no contraindication for MRI. The study procedures were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board, and informed written consent was obtained from all participants. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

R2* growth trajectories vary across regions

As the first step, we modeled the growth trajectory of R2* values across 88 brain anatomical gray matter regions of interest (ROIs) during the birth transition using generalized additive mixed-effects models (GAMMs), following the equation: R2* ~ 1 + s(GA) + (1|subject). R2* corresponds to the rate at which a voxel’s signal decays over echoes (see details in “Methods” section). The majority of ROIs (76 out of 88 regions) demonstrated a significant association between changes in R2* and GA (p < 0.00056, Bonferroni-corrected for 88 tests). The average R2* and the R2* change rate across the brain are provided in Fig. 2. R2* growth trajectories by regions can be found in the Supplementary Materials Appendix II.

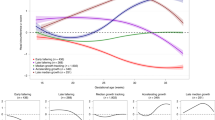

Based on the developmental trajectories and rate of change (first derivative) in R2*, we next categorized trajectories into three patterns (Fig. 3): (1) minimum change, where age had no significant effect or the absolute change rate <0.2 (1/week*s) (13 regions); (2) near-linear change, with a rate variance of <0.02 (1/week*s) (52 regions); and (3) non-linear change, characterized by varying rates (23 regions).

Notable patterns observed include non-linear changes in R2* in the posterior part of the brain, particularly the occipital lobe, inferior temporal regions, and temporal pole, as well as select frontal areas (Fig. 3). This non-linear trend in the posterior part of the brain is also apparent in Fig. 2B, with the most yellow color in the occipital lobe during the 30–40 weeks window, indicating accelerated growth. In contrast, the majority of parietal regions and bilateral superior temporal regions, including the Heschl’s gyrus, demonstrate a near-linear growth trend. Regions with minimal R2* changes included the bilateral superior frontal cortex, the right inferior and medial orbital frontal cortex, bilateral caudate, and the left parahippocampus. Notably, many symmetric bilateral counterparts demonstrated similar growth patterns.

Peak non-linear change observed around the birth transition

We then identified the peak developmental window by averaging the first derivative within a 10-week sliding window. The window with the maximum rate of change was observed around 40 weeks in most of the non-linear trajectories, as shown with shaded areas in Fig. 4.

We also calculated the average rates of development during the prenatal (<40 weeks) and postnatal (>40 weeks) periods, based on which we organized the plots in Fig. 4 into prenatal >postnatal and prenatal <postnatal groups. Notably, the bilateral occipital regions, extending into the occipitoparietal area, and the bilateral temporal poles exhibit faster development during the prenatal period. In contrast, accelerated postnatal growth was observed in the left orbital frontal cortex, bilateral inferior temporal cortex, bilateral fusiform gyrus, right putamen, right precuneus, and right Rolandic operculum.

Nominal effects of sex and birth outcomes on R2* development

We extended the main GAMM model R2* ~ 1 + s(GA) + (1|subject), by individually incorporating the main effects of sex, GA at birth, and birth weight, along with their respective interaction terms with age in separate models. We also explored the impact of a binary variable—preterm (GA at birth ≤ 37 weeks) versus full-term (GA at birth > 37 weeks)—in an additional regression model. After applying multiple comparison corrections, none of these additions showed significant effects on R2* changes. Sex-specific R2* fitted curves for all brain regions are provided in the Supplementary Materials Appendix III. For regions showing a marginal effect (p < 0.01) of the interaction between preterm status and GA, plots highlighting preterm cases are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. In a final step, we performed an additional sensitivity analysis controlling for maternal diet and alcohol/tobacco use in above models; these are reported in the Supplementary Materials Fig. 3.

Discussion

The perinatal period marks a crucial transition from the intrauterine to the extrauterine environment, which requires significant brain adaptation with multi-level changes in both structure and function. Previous studies to date have examined R2* change within either the fetal25 or postnatal period26 separately. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on brain R2* changes across birth using a sizable longitudinal ME MRI data cohort. Our findings highlight both continuity in the motor and auditory systems and discontinuity in the visual system regarding R2* development at birth. This supports the notion that the brain is in a preparatory stage for delivery in terms of iron availability.

In this study, we observed that developmental patterns of R2* vary across regions. This aligns with the well-established understanding that brain growth from birth is not uniform across the brain21,35. For example, neonatal brain volume grows most rapidly in the cerebellum, while the hippocampus experiences the slowest growth within the first 90 days36. Regional and temporal heterogeneity is also evident in metabolic imaging. In neonates, glucose metabolism activity is highest in the primary sensory and motor cortex, medial temporal regions, thalamus, brainstem, and cerebellar vermis. However, by 2–3 months of age, peak activity shifts to the parietal, temporal, cingulate, and primary visual cortices, as well as the basal ganglia and cerebellar hemispheres37. Similarly, with a broader age range, cerebral blood flow imaging shows higher blood flow in the primary sensorimotor, auditory, and visual cortices in 0–3-month-old infants, while increased blood flow is observed in association cortices in infants older than 12 months38. Although these studies focus exclusively on the postnatal period, it is widely recognized that different brain regions develop at varying rates during early life, corresponding to the shifting priorities in behavioral development over time. Given that iron is fundamental to neurogenesis and metabolism, the regional heterogeneity in R2* observed in our study provides new insight into the mechanisms underlying the regional and temporal variations observed in these neural developmental processes.

The non-linear growth patterns observed in the occipital and inferior temporal lobes may reflect the brain’s preparation and adaptation for the substantial visual sensory shift experienced at birth39. Visual input from the outside world represents a dramatic change for fetuses compared to the limited light within the in-utero environment40. The fetus’s eyes open by the second trimester (around week 26 of gestation). During the third trimester, the retino-thalamic tracts for sensory processing of visual stimuli become sufficiently developed to respond to light outside the womb, enabling abilities such as focusing on objects, tracking motion, and detecting warm colors39. Upon birth, newborns as young as 0–3 days old can already display a preference for looking at faces with direct gaze, suggesting the importance of facial recognition for establishing communication and anticipating the coincidence of faces with physical contact41. The accelerated growth rate of R2* levels observed in the occipital lobe from ~35 to 45 weeks of gestation may reflect the rapid development of visual systems. Specifically, the sharp R2* increase in the bilateral fusiform gyrus, temporal pole, and inferior temporal cortex may play a crucial role in the functional development of object and facial recognition, as these regions are critically involved in processing complex visual information42,43,44.

Linear growth trajectories in the occipital, parietal and superior temporal lobe may signal the onset of developmental shifts in these regions prior to birth. The occipital lobe and parietal lobe support visual and motor function, respectively. The superior temporal lobe, including the Heschl’s gyrus, is responsible for auditory processing. Linear changes in these regions appear to result from steady growth that begins before birth. This pattern coincides with behavioral and developmental processes that have prenatal onset. For example, fetal motor activity emerges early and matures rapidly; during the first trimester, movements are primarily jerky, whole-body actions, while by the second and third trimesters, they become more complex and directed45,46. Although overall fetal movement decreases toward term due to physical constraints, the nature of these movement become more fluid and targeted, such as responding to stimuli (e.g., maternal movement) and coordinating with other sensory systems46,47. After birth, movements refine within the first hour to resemble crawling, with more leg steps and arm actions, indicating that the brain is sufficiently developed for such behavior at birth40,48. This progression is in line with our observation that R2* in the motor cortex continues to accumulate across birth without an influx point. Similarly, the auditory system begins developing early before birth and continues through post birth. Unlike the limited visual stimuli available prenatally, the fetus is exposed to a rich array of auditory sensations. These include the dominant, thrumming noise of the amniotic environment (~28 dB) during early gestation, as well as sounds ranging from conversations at typical volume (60 dB) to louder noises like a car horn (105 dB) by the third trimester49. In fact, the fetus can display the ability to differentiate unexpected auditory stimuli, as evidenced by changes in heart rate and motor activity, indicating that the auditory system is functional before birth50,51. Such perinatal continuity of auditory learning aligns with the linear growth pattern of R2* we observed in the superior temporal region.

In this study, we did not observe any significant effect of sex on R2* development during the birth transition. However, in an earlier study by our group focusing on the fetal period within the same data cohort25, we observed that females exhibited a faster rate of R2* increase compared to males. When the observational window was extended to include early infancy in the current study, sex effect was no longer significant. Additionally, we did not find significant interactions between birth outcomes or preterm status with R2* development. We attribute this, in part, to the limited number of preterm cases in our sample (n = 6), which likely reduced the statistical power to detect such effects. Nevertheless, we maintain that R2* is a sensitive marker of neurodevelopment, and we anticipate that future studies with larger sample sizes will better detect robust interaction effects between iron development, sex, and birth outcomes.

The limitations of this study warrant discussion. First, R2* is not a direct measure of iron; it rather reflects a combined effect of iron accumulation, myelination, blood oxygenation, and other sources of magnetic field inhomogeneity52,53. Further, while there is direct histological demonstration of the relationship between iron and MRI R2* in the adult brain, particularly in iron-rich nuclei27, there is no comparable evidence for the human fetus. In the fetus, myelin and iron levels are lower than in adults, and characteristics of the MR gradient field differ, which raises the possibility that a different combination of factors give rise to R2* signal measurements. Therefore, we approach the current study as descriptive, addressing early human R2* maturation patterns, rather than representing a narrow iron developmental process. It is most likely that a combination of underlying biological processes give rise to our R2* effects. More detailed discussion of this topic is also addressed in our prior work25. Another approach consideration in this study is potential methodological differences in obtaining fetal versus infant R2* estimates. Most notably, it is not possible to eliminate different properties of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the two datasets. This is nominally addressed in our region-wise approach and data harmonization methods applied in this study, but it remains an influence to be considered in interpreting the results.

Alternative approaches to R2* mapping for iron assessment in early human development merit discussion. For future studies, one can consider techniques like Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) or Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI). However, their application to fetal imaging remains limited due to unique challenges, such as the small size of the fetal brain, reduced SNR, and extensive motion artifacts arising from both spontaneous fetal movement and maternal motion54. Unfortunately, at present, standardized protocols for data acquisition and processing using QSM or SWI in the fetal brain are not yet fully established. One advantage of our R2*-based method for indexing iron is its compatibility with rapid acquisition using fast ME EPI sequences. Our approach captures whole-brain data at three echo times in 2 s (TR = 2 s). Data are collected and reconstructed as a series that lends itself to separating periods of fetal motion from fetal quiescence and effectively “cleaning” the data. In fact, data from the current study were required as part of a project that sought to measure functional network development in the fetal brain. Prior publications in this cohort have addressed how patterns in functional connectivity that relate to conditions of pregnancy34, advancing age55, and future individual developmental outcomes47,56. A strength of this sequence design is that it provides a unique opportunity to investigate both Blood-Oxygen-Level Dependent (BOLD) signals and R2* values simultaneously within a single acquisition. The spatial resolution of the fetal brain data (3.5 mm isotropic) is not ideal but was optimized by balancing spatial resolution, SNR, and temporal resolution in our sequence. This trade-off is necessary in fetal fMRI, where maintaining an acceptable TR is critical for both BOLD analysis and R2* estimation in reducing intra-TR motion artifacts. Similarly, the choice of TE also reflects a trade-off between minimizing fetal motion and ensuring accurate R2* estimation. Longer TEs capture a more complete decay curve but also increase the risk of motion between echoes. Another study57 that focused on T2* measurement as the primary objective reported better anatomical validity and reliability of T2* fits using 5 echoes ranging from 27 to 199.8 ms, along with in-plane registration. Future work may explore how to optimize more current R2* and QSM approaches to further advance understanding of the role of brain iron during early human neurodevelopment around birth.

Notably, in our non-linear R2* developmental trajectories, we observe some variations—for instance, a decrease in R2* before 30 weeks and after 50 weeks in certain trajectories shown in Fig. 4. These patterns are intriguing, as they may reflect the brain’s adaptive strategies for optimal development. However, we are cautious about overinterpreting these findings, as the fluctuations may also stem from imbalances in the distribution of observations across age—a characteristic inherent to the accelerated longitudinal design. To account for this uneven age density, we included a smoothed age term in all regression analyses. Future studies with larger and more evenly distributed samples will be important for validating the non-linear variations observed here. While our study is motivated on measuring fetal and neonatal brain iron levels, we acknowledge the absence of direct measures of maternal iron deficiency as a limitation. Maternal peripheral iron measures were not obtained in this study sample, nor reliably available in medical records. The relationship between brain and peripheral iron is likely to be a complex association, as many physiological and psychological factors can influence iron absorption and regulation58. It will be important for future studies to evaluate further the relationships between central and peripheral iron and their interactive physiological and psychosocial functions, even in experimental animal models. Studies such as these are likely to build foundational mechanistic knowledge while also providing new avenues for intervention. Despite these limitations, the findings of this study represent novel insights and provide a critical foundation for exploring the mechanisms underlying neurodevelopmental conditions associated with iron deficiency. Iron deficiency is common in pregnant women and children under 4 years, particularly in developing countries, and can have long-lasting effects on developmental outcomes4,59,60. The birth transition is a sensitive developmental window, making it important to understand iron dynamics during this time. Building on this study, deeper exploration of the environmental factors influencing brain iron development could inform future studies aimed at preventing iron deficiency-related developmental disorders through early interventions.

Methods

MRI data acquisition

Fetal data was acquired using a 3T Siemens Verio 70 cm open-bore system with an abdominal 4-channel Siemens Flex coil, with the following scanning parameters: 12-min ME fMRI sequence, TR = 2000 ms; TE = 18, 34, 50 ms (3 echoes); flip angle: 83 degrees; voxel size: 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm3.

Infants were scanned on the same scanner with a 32-channel head coil, using one of three sets of acquisition parameters, as detailed below. (i) 12-min ME fMRI: TR = 2000 ms; TE = 13, 26, 39 ms; flip-angle: 83 degrees; slice-gap: none; voxel-size: 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm3; matrix-size: 64 × 64 × 39 voxels. (ii) 12-min multi-band (MB) ME fMRI scan: TR = 1500 ms; TE = 15, 31, 46 ms; flip-angle: 83 degrees; slice-gap: none; voxel-size: 2.9 × 2.9 × 2.9 mm3; matrix-size: 64 × 64 × 48 voxels, multi-band factor = 2. (iii) 7-min MB ME fMRI scan: TR = 1000 ms; TE = 14.6, 36.68, 58.76 ms; flip-angle: 52; slice-gap: none; voxel-size: 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm3; matrix- size: 80 × 80 × 44 voxels, multi-band factor = 4.

Fetal MRI data preprocessing

Details on fetal fMRI data preprocessing and R2* estimation have been described in our previous study25. Scans with poor image quality have been excluded from this study. Briefly, preprocessing began with automatic fetal brain extraction using a deep-learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm61 to create a rough 4D mask, enabling motion estimation via FSL mcflirt62. We then applied the inverted transformation matrices estimated by FSL mcflirt to a manually drawn mask iteratively to generate a precise, individualized 4D mask. The 4D masks were quality-checked for accuracy, and manual edited as needed. Following this, the isolated fetal brain underwent a final round of motion correction in preparation for subsequent analysis. We identified and averaged 10 consecutive volumes with the lowest root-mean-square of voxel-wise differentiated signal (DVARS63) from this motion-corrected fetal brain data, resulting in a single volume for each of the three echoes for T2* estimation. We chose to use the average of 10 stable fMRI volumes to achieve a higher SNR compared to a single volume, while mitigating the risk of motion-related artifacts introduced by more volumes. T2* maps were generated by fitting a monoexponential decay model to the data collected across echoes. Code for fetal fMRI preprocessing and T2* estimation is available at: https://zenodo.org/records/14051966.

Infant MRI data preprocessing and T2* estimation

Details on infant fMRI data preprocessing and R2* estimation is described in an earlier study26. The infant brain was extracted using FSL’s Brain Extraction Tool BET,64, and motion correction was estimated based on the first echo via “FSL mcflirt”62. The resulting alignment parameters were applied to the remaining echoes. The root-mean-square of voxel-wise differentiated signal (DVARS)63 were estimated based on alignment parameters using fsl_motion_outliers62. Volumes with DVARS greater than 50 were marked as outliers (censored frames). One frame before and two frames after these volumes were flagged as censored frames as recommended in prior literature65. FMRI runs with more than half of the volumes labeled as censored frames were excluded. Finally, echo combination and T2* estimation were performed using TE-Dependent Analysis (Tedana)66,67. Within Tedana toolbox, the estimation of T2* involves fitting a monoexponential decay model to the data collected across echoes. T2* maps were quality checked with visual inspection by author L.J. and B.C.

Regional R2* calculation and quality control

Fetal and infant T2* maps were then normalized to a 32-week fetal template68 and a neonatal template69, using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs)70 and SPM71, respectively. In fetal data, the mapping between an individual space and the template space is constructed as a concatenation of several intermediate transformations: (1) a non-linear registration between the fMRI BOLD data and the age-matched fetal template68, (2) a series of nonlinear transformations between templates of adjacent ages (e.g., 24 and 23 weeks, 25 and 24 weeks, etc.) estimated using ANTs70. This gradual alignment approach can minimize the risk of gross misalignments due to differences in brain topology across GA. In infant data, T2* maps were transformed to the template space using the transformation estimated from fMRI BOLD data and the template, as describe in a prior report26.

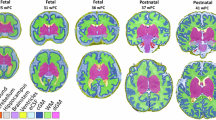

According to existing literature, T2* estimation can be affected by macroscopic field gradients, such as those at air–tissue interfaces72. In our dataset, we also observed voxels with T2* values out of the expected physiological range. To exclude these non-biologically meaningful R2* values, we set voxels with T2* outside the accepted range (50–400 ms) to zero. R2* values were derived as the inverse of T2* (1/T2*). We then extract mean R2* values from 88 anatomical brain regions of interest (ROIs, Fig. 5) using fslstats, considering only non-zero voxels. We selected these parcellation atlases because they are both widely used anatomical references with highly consistent and reliable labeling, ensuring comparability and reproducibility in our analyses. Representative fetal and infant T2* images at each processing step are provided in Fig. 6. Source data of R2* for all subjects across ROIs, both before and after harmonization, are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

The fetal brain atlas is sourced from Gholipour et al. (2017, see detailed description of ROIs in Supplementary Materials, Appendix I)68 and can be accessed at: http://crl.med.harvard.edu/research/fetal_brain_atlas/. The infant atlas is provided by Shi et al. (2011)69 and is available at: https://www.nitrc.org/projects/pediatricatlas. Corresponding regions across the templates are represented using the same colors for consistency.

T2* maps were first estimated using three echo images and manually reoriented to align with the template (left column). In Step 1, the maps were normalized to a standard space (middle column). In Step 2, thresholding was applied to exclude voxels with values outside the range of 50–400 ms, setting them to zero. Based on these thresholded maps (right column), R2* values were calculated as the inverse of T2* (1/T2*). In Step 3, mean R2* values within each ROI were computed considering only non-zero voxels. In Step 4, a longitudinal harmonization technique was applied to the regional R2* values to account for differences in MRI quality across scans. The harmonized R2* values for each region were then used in Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs) for statistical analysis.

Harmonization on MRI condition effects

To account for non-biological variance introduced by different MRI conditions (i.e., in-utero vs. ex-utero effects) and acquisition protocols, we applied a longitudinal harmonization technique to regional R2* values using the R package LongComBat73. LongComBat enhances the traditional ComBat harmonization method by incorporating scanner effects into a linear mixed effects model. This model includes subject-specific random intercepts and biological factors (e.g., age and sex), making it possible to separate true longitudinal changes from technical artifacts. The method breaks down non-biological variation into two types of scanner-level batch effects: additive (shifts in baseline) and multiplicative (changes in scale). These effects are estimated using empirical Bayes shrinkage to create stable parameters across scanners. After correction, the residuals are rescaled and combined with the biological effects, creating harmonized measurements that maintain true developmental or disease-related patterns while removing scanner-related interference. This technique is especially useful when merging fetal and neonatal MRI data from different protocols, as it reduces bias from different coils, noise levels, and contrast settings while preserving the underlying biological information.

Since the harmonization is performed on model residuals, the longitudinal ComBat model matches the model in the final regression analysis. Distribution of GA at scan across MRI sequences is provided in the Supplementary Materials Fig 1. The same figure also presents a side-by-side comparison of R2* growth trajectories before and after applying LongCombat in three example ROIs.

Statistical and reproducibility

Subsequently, we examined the developmental trajectory of regional R2* modeled with generalized addictive mixed-effect models (GAMMs) using R (Version 2023.06.1 + 524), following the equation R2* ~ 1 + Age + (1|Subject). Model comparison between the linear model and GAMMs was conducted using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC values), with GAMMs demonstrating better AIC scores across all regions. At the regional and subject levels, R2* outliers were identified and excluded from the statistical analyses using the rosnerTest package74, to ensure the data approximated a normal distribution. To quantify periods of developmental differences, we analyzed the local slope (first derivative) of age-related changes at 1/4th-week intervals for all non-linear GAMMs. We then examined the effects of sex, birth week, and birth weight by incorporating interaction terms into the GAMMs. Significance was determined using a threshold of p < 0.00056, adjusted for multiple comparisons with a Bonferroni correction across 88 regions.

We further extended the main GAMM model R2* ~ 1 + s(GA) + (1|subject), by individually incorporating the main effects of sex, GA at birth, and birth weight, along with their respective interaction terms with age in separate models. We also explored the impact of a binary variable—preterm (GA at birth ≤ 37 weeks) versus full-term (GA at birth > 37 weeks)—in an additional regression model. See Table 2 for a summary of our regression models. Although we did not observe any significant results with these additional effects, we provided the R2* curve for regions showing a marginal effect (p < 0.01) of the preterm and GA interaction in Supplementary Fig 2, where preterm cases are highlighted in red.

Ethics

The Wayne State University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures of the Perinatal Imaging of Neural Connectivity (PINC) project (IRB number: IRB-21-08-3875). Informed written consent was provided by participating pregnant people. This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All analyses conducted in this work were approved by NYU Langone Health IRB (IRB number: i18-00960_MOD04).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

This paper analyzes existing available data from the Perinatal Imaging of Neural Connectivity (PINC) project. The R2* datasets underlying the results in this work are provided in the Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The codes for fetal R2* estimation, data harmonization, and longitudinal modeling is available on Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17109779.

References

McCann, S., Perapoch Amadó, M. & Moore, S. E. The role of iron in brain development: a systematic review. Nutrients 12, 2001 (2020).

Kostović, I., Sedmak, G. & Judaš, M. Neural histology and neurogenesis of the human fetal and infant brain. Neuroimage 188, 743–773 (2019).

Wigglesworth, J. Iron dependent enzymes in the brain. Brain iron: neurochemical and behavioral aspects, 25–66 (1988).

Lozoff, B. & Georgieff, M. K. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 13, 158–165 (2006).

Ward, K. L. et al. Gestational and lactational iron deficiency alters the developing striatal metabolome and associated behaviors in young rats1. J. Nutr. 137, 1043–1049 (2007).

Riggins, T., Miller, N. C., Bauer, P. J., Georgieff, M. K. & Nelson, C. A. Consequences of low neonatal iron status due to maternal diabetes mellitus on explicit memory performance in childhood. Dev. Neuropsychol. 34, 762–779 (2009).

Burden, M. J. et al. An event-related potential study of attention and recognition memory in infants with iron-deficiency anemia. Pediatrics 120, e336–e345 (2007).

Tamura, T. et al. Cord serum ferritin concentrations and mental and psychomotor development of children at five years of age. J. Pediatr. 140, 165–170 (2002).

Congdon, E. L. et al. Iron deficiency in infancy is associated with altered neural correlates of recognition memory at 10 years. J. Pediatr. 160, 1027–1033 (2012).

Lozoff, B. et al. Dose-response relationships between iron deficiency with or without anemia and infant social-emotional behavior. J. Pediatr. 152, 696–702.e693 (2008).

Schmidt, R. J., Tancredi, D. J., Krakowiak, P., Hansen, R. L. & Ozonoff, S. Maternal intake of supplemental iron and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180, 890–900 (2014).

East, P. L. et al. Iron deficiency in infancy and sluggish cognitive tempo and ADHD symptoms in childhood and adolescence. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 52, 259–270 (2023).

Insel, B. J., Schaefer, C. A., McKeague, I. W., Susser, E. S. & Brown, A. S. Maternal iron deficiency and the risk of schizophrenia in offspring. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65, 1136–1144 (2008).

Algarín, C., Peirano, P., Garrido, M., Pizarro, F. & Lozoff, B. Iron deficiency anemia in infancy: long-lasting effects on auditory and visual system functioning. Pediatr. Res. 53, 217–223 (2003).

Brunette, K. E., Tran, P. V., Wobken, J. D., Carlson, E. S. & Georgieff, M. K. Gestational and neonatal iron deficiency alters apical dendrite structure of CA1 pyramidal neurons in adult rat hippocampus. Dev. Neurosci. 32, 238–248 (2010).

Zamora, T. G., Guiang, S. F., Widness, J. A. & Georgieff, M. K. Iron is prioritized to red blood cells over the brain in phlebotomized anemic newborn lambs. Pediatr. Res. 79, 922–928 (2016).

Georgieff, M. K. Iron assessment to protect the developing brain. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106, 1588S–1593S (2017).

Georgieff, M. K. The importance of iron deficiency in pregnancy on fetal, neonatal, and infant neurodevelopmental outcomes. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 162, 83–88 (2023).

Polese, D., Fagioli, M., Virgili, F. & Fiori Nastro, P. Something must happen before first breath. BMC Med. Ethics 22, 57 (2021).

Polese, D. & Fagioli, F. A primer on human birth theory. Psychodyn. Psychiatry 52, 276–282 (2024).

Johnson, M. H. Functional brain development in humans. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 475–483 (2001).

Counsell, S. J. et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the brain in preterm infants with focal and diffuse white matter abnormality. Pediatrics 112, 1–7 (2003).

Chugani, H. T., Phelps, M. E. & Mazziotta, J. C. Positron emission tomography study of human brain functional development. Ann. Neurol. 22, 487–497 (1987).

Ji, L. et al. Trajectories of human brain functional connectome maturation across the birth transition. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002909 (2024).

Ji, L. et al. Whole brain MRI assessment of age and sex-related R2* changes in the human fetal brain. Hum. Brain Mapp. 46, e70073 (2025).

Ji, L. et al. Developmental coupling of brain iron and intrinsic activity in infants during the first 150 days. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 64, 101326 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Methods for quantitative susceptibility and R2* mapping in whole post-mortem brains at 7T applied to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroimage 222, 117216 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. Phenotypic and genetic associations of quantitative magnetic susceptibility in UK Biobank brain imaging. Nat. Neurosci. 25, 818–831 (2022).

Haacke, E. M. et al. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging 23, 1–25 (2005).

Cohen-Adad, J. What can we learn from T2* maps of the cortex?. NeuroImage 93, 189–200 (2014).

Yang, Z. et al. Prevalence and predictors of iron deficiency in fully breastfed infants at 6 mo of age: comparison of data from 6 studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89, 1433–1440 (2009).

Domellöf, M. et al. Sex differences in iron status during infancy. Pediatrics 110, 545–552 (2002).

Haider, B. A. et al. Anaemia, prenatal iron use, and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 346, f3443 (2013).

Thomason, M. E. et al. Prenatal lead exposure impacts cross-hemispheric and long-range connectivity in the human fetal brain. Neuroimage 191, 186–192 (2019).

Huttenlocher, P. R. & Dabholkar, A. S. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 387, 167–178 (1997).

Holland, D. et al. Structural growth trajectories and rates of change in the first 3 months of infant brain development. JAMA Neurol. 71, 1266–1274 (2014).

Chugani, H. T. Imaging brain metabolism in the newborn. J. Child Neurol. 33, 851–860 (2018).

Ouyang, M. et al. Spatiotemporal cerebral blood flow dynamics underlies emergence of the limbic-sensorimotor-association cortical gradient in human infancy. Nat. Commun. 15, 8944 (2024).

Meredith Weiss, S., Aydin, E., Lloyd-Fox, S. & Johnson, M. H. Trajectories of brain and behaviour development in the womb, at birth and through infancy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1251–1262 (2024).

Polese, D. et al. The Newborn’s reaction to light as the determinant of the Brain’s activation at human birth. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 16, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2022.933426 (2022).

Farroni, T. et al. Infant cortex responds to other humans from shortly after birth. Sci. Rep. 3, 2851 (2013).

Weiner, K. S. & Zilles, K. The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia 83, 48–62 (2016).

Herlin, B., Navarro, V. & Dupont, S. The temporal pole: from anatomy to function—a literature appraisal. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 113, 101925 (2021).

Conway, B. R. The organization and operation of inferior temporal cortex. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 4, 381–402 (2018).

Lüchinger, A. B., Hadders-Algra, M., Van Kan, C. M. & De Vries, J. I. Fetal onset of general movements. Pediatr. Res. 63, 191–195 (2008).

Reissland, N., Francis, B., Buttanshaw, L., Austen, J. M. & Reid, V. Do fetuses move their lips to the sound that they hear? An observational feasibility study on auditory stimulation in the womb. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2, 1–7 (2016).

Ji, L., Majbri, A., Hendrix, C. L. & Thomason, M. E. Fetal behavior during MRI changes with age and relates to network dynamics. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 1683–1694 (2023).

Hym, C. et al. Newborns modulate their crawling in response to their native language but not another language. Dev. Sci. 26, e13248 (2023).

Moore, J. K. & Linthicum, F. H. Jr The human auditory system: a timeline of development. Int. J. Audiol. 46, 460–478 (2007).

Groome, L. J. et al. Behavioral state affects heart rate response to low-intensity sound in human fetuses. Early Hum. Dev. 54, 39–54 (1999).

Morokuma, S. et al. Developmental change in fetal response to repeated low-intensity sound. Dev. Sci. 11, 47–52 (2008).

Daugherty, A. M. & Raz, N. Appraising the role of iron in brain aging and cognition: promises and limitations of MRI methods. Neuropsychol. Rev. 25, 272–287 (2015).

Lao, G. et al. Sub-voxel quantitative susceptibility mapping for assessing whole-brain magnetic susceptibility from ages 4 to 80. Hum. Brain Mapp. 44, 5953–5971 (2023).

Rajagopalan, V., Deoni, S., Panigrahy, A. & Thomason, M. E. Is fetal MRI ready for neuroimaging prime time? An examination of progress and remaining areas for development. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 51, 100999 (2021).

Thomason, M. E. et al. Age-related increases in long-range connectivity in fetal functional neural connectivity networks in utero. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 11, 96–104 (2015).

Thomason, M. E. et al. Prenatal neural origins of infant motor development: Associations between fetal brain and infant motor development. Dev. Psychopathol. 30, 763–772 (2018).

Vasylechko, S. et al. T2* relaxometry of fetal brain at 1.5 Tesla using a motion tolerant method. Magn. Reson. Med. 73, 1795–1802 (2015).

Reid, B. M. & Georgieff, M. K. The interaction between psychological stress and iron status on early-life neurodevelopmental outcomes. Nutrients 15, 3798 (2023).

De Onis, M., Blossner, M. & Organization, W. H. WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition (World Health Organization, 1997).

Stoltzfus, R. J., Mullany, L. & Black, R. E. Iron deficiency anaemia. Comparative quantification of health risks: global and regional burden of disease attributable to selected major risk factors 1, 163–209 (2004).

Rutherford, S. et al. Automated brain masking of fetal functional MRI with open data. Neuroinformatics 20, 173–185 (2022).

Jenkinson, M., Bannister, P., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17, 825–841 (2002).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59, 2142–2154 (2012).

Smith, S. M. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 17, 143–155 (2002).

Li, J. et al. Global signal regression strengthens association between resting-state functional connectivity and behavior. NeuroImage 196, 126–141 (2019).

Kundu, P., Inati, S. J., Evans, J. W., Luh, W.-M. & Bandettini, P. A. Differentiating BOLD and non-BOLD signals in fMRI time series using multi-echo EPI. Neuroimage 60, 1759–1770 (2012).

DuPre, E. et al. TE-dependent analysis of multi-echo fMRI with* tedana. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3669 (2021).

Gholipour, A. et al. A normative spatiotemporal MRI atlas of the fetal brain for automatic segmentation and analysis of early brain growth. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Shi, F. et al. Infant brain atlases from neonates to 1-and 2-year-olds. PloS one. 6, e18746 (2011).

Avants, B. B., Tustison, N. & Song, G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight j. 2, 1–35 (2009).

Friston, K. J. Statistical parametric mapping. Neuroscience Databases: A Practical Guide 237–250 (Springer US, 2003).

Hernando, D., Vigen, K. K., Shimakawa, A. & Reeder, S. B. R. mapping in the presence of macroscopic B0 field variations. Magn. Reson. Med. 68, 830–840 (2012).

Beer, J. C. et al. Longitudinal ComBat: a method for harmonizing longitudinal multi-scanner imaging data. NeuroImage 220, 117129 (2020).

Rosner, B. On the detection of many outliers. Technometrics 17, 221–227 (1975).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/) grant MH122447 and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, https://www.niehs.nih.gov/) grant ES032294 for M.E.T. and C.J.T., NIMH grants MH126468, MH110793 and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA, https://nida.nih.gov/) grant DA055338 for M.E.T., and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, https://www.nichd.nih.gov/) grant K99HD113873 for L.J. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank all the families who took part in this project for their participation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.T., L.J., and C.J.T.; Methodology, L.J. and M.E.T.; Data collection, C.J.T. and M.E.T.; Formal analysis, L.J. and B.C.; Writing—original draft, L.J.; Writing—review and editing, M.E.T., B.C., I.M., and C.J.T.; Funding acquisition, M.E.T and C.J.T; Resources, M.E.T.; Visualization, L.J.; Supervision, M.E.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Yuyao Zhang, Aylin Rosberg and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Sahar Ahmad and Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, L., Chen, B., Menu, I. et al. Human brain R2* transitions across birth from the womb to early infancy. Commun Biol 8, 1567 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08932-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08932-w