Abstract

Children differ in brain cortical morphometry and microstructure, which together form the structural foundation for cognition. Cortical structure is highly heritable, but whether heritability varies across socioeconomic status (SES) is unknown. In this preregistered study, we estimated single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based heritability of cortical thickness, surface area, sulcal depth, and grey-/white-matter contrast (GWC) among 9,080 US 10-year-olds. We then tested whether genetic and environmental contributions were moderated by parental SES, defined as a composite of income, education, and neighbourhood deprivation. Cortical thickness and surface area showed high heritability, while sulcal depth and GWC exhibited moderate heritability. However, among children from lower-SES backgrounds, cortical differences were less genetically related and more uniquely environmentally related, at times exceeding genetic contributions. These findings suggest that in contexts of socioeconomic disadvantage, children’s brain structure reflect lived experience more strongly than previously recognized.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nearly all human characteristics arise from a combination of genetic and environmental influences. Heritability quantifies the proportion of variation in a trait that is attributable to genetic differences, with estimates based on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) typically being lower than those derived from family studies1. The cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer folded layer, shows individual differences in morphological features such as thickness, surface area, and folding patterns, as well as in microstructural properties reflected in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based signal intensity. These structural variations are closely linked to developmental stage2,3 and relate to cognitive functions4,5,6,7 and mental health8,9.

Neuroimaging studies document that brain structure is highly heritable, with family-based estimates in the range of 60–80%, with age-, metric-, and region-specific variation10,11,12. However, research has largely overlooked the notion that genetic influences may vary across socioeconomic contexts13,14,15,16. While socioeconomic status (SES) is related to cortical structure itself17,18,19,20, it is unknown to what degree its genetic influences also depend on SES. Genetic moderation by SES has mainly been explored in cognitive research.

Twin studies estimate cognitive abilities to be 50–70% heritable, depending on age and the specific ability studied21,22,23,24. Several studies have found that the heritability of cognition is positively moderated by SES. This pattern, known as the “Scarr-Rowe hypothesis”, was first reported in the US in the 1970s16 and later replicated in Sweden25 and again in the US15, though recent findings are mixed26,27,28. A commonly proposed mechanism for this relation is that children from low SES backgrounds have fewer opportunities to develop their predispositions, limiting the expression of their genetic potential. In contrast, genetic influences on cognitive traits may be maximized in high SES-settings, where resources are more readily available29,30. Alternative theoretical frameworks include the “Pareto hypothesis” which posits that the genetic potential of cognitive abilities is most fully expressed in middle-class environments and restricted in both low and high SES groups due to limiting-, and buffering protective factors, respectively31. The “Saunders hypothesis” focuses solely on the protective role of high SES, suggesting that genetic potential is less fully expressed within this stratum31.

Despite extensive research on how the heritability of cognitive abilities varies by socioeconomic standing, no study has examined whether SES similarly moderates the heritability of cortical structure. Addressing this gap could reveal whether children’s brains are shaped differently by their inherited predispositions and lived experience, depending on socioeconomic context.

In this preregistered study, we analysed cross-sectional data from over 9000 children and their parents, including 2544 children with at least one co-enrolled sibling, from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. Genetic effects were assessed via SNP genotypes, child cortical structure via MRI based global and lobar cortical thickness, surface area, sulcal depth, and grey/white-matter contrast (GWC), and SES via a composite of parental income, education, and neighbourhood deprivation. We first estimated the overall heritability (h² = A/(A + C + E)) of cortical structure, where A is the additive genetic variance, C is the environmental variance shared by siblings, and E is the environmental variance unique to the child. Because h² is a proportion of total variance attributable to genetics, it depends on the denominator; for example, increasing environmental variance (C or E) lowers h² even if A is unchanged. Next, we tested whether the absolute variances A, C, and E differed across socioeconomic contexts. Additionally, we examined the genetic and environmental effects on cognitive abilities within the same sample.

Results

Genetic contribution to cortical structure and moderation by parental SES

Cortical thickness

Baseline linear mixed effects modelling without genetic or environmental interaction terms revealed a SNP-based heritability for mean cortical thickness of h2 = 0.82 after controlling for age, sex, and genetic principal components (PC) related to population stratification.

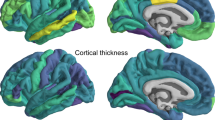

Likelihood ratio tests comparing the baseline main effects-model and the interaction model between the SES index and additive genetic, shared environment, and unique environmental factors yielded a non-significant interaction after multiple comparisons correction (x2 = 8.27, Df = 3, p = 0.04, corrected p = 0.051), thus providing no indication that the heritability of global cortical thickness differs across SES levels. Baseline lobar analyses revealed that the heritability of cortical thickness varied between 0.69 and 0.80, depending on region (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information (SI) Table 1). Further, likelihood ratio tests indicated that the genetic and environmental factors contributing to the heritability of parietal (x2 = 12.56, Df = 3, p = 0.006, corrected p = 0.015) and occipital thickness (x2 = 9.47, Df = 3, p = 0.024, corrected p = 0.04) varied across SES levels (Table 1). Specifically, the heritability of parietal and occipital thickness was higher for children in high SES settings, due to increased additive genetic effects and reduced unique environmental influences, while shared environmental effects remain consistently negligible across SES levels (Fig. 2).

The image displays splines representing heritability (h2 = A/(A + C + E); brown), along with its components: additive genetics (A; green), shared environment (C; dark orange), and unique environment (E; yellow) for cortical thickness across the standardized SES construct. The density distribution of SES is shown as a shaded area below the x-axis. The dotted grey line shows the total phenotypic variance (A + C + E).

Heritability estimates for all imaging metrics, whether derived from a more genetically homogeneous subsample (SI Figs. 5–6, SI Table 5) or obtained using a twin-based method, yielded similar results, are presented in the SI Results (SI Tables 2, 3).

Surface area

SNP-based heritability for total surface area was h² = 0.82 after controlling for age, sex, and population stratification. Likelihood ratio tests yielded a non-significant interaction between the SES index and genetic and environmental factors after correction (x2 = 8.34, Df = 3, p = 0.04, corrected p = 0.051), thus providing no indication that the heritability of global surface area differs across SES levels. Lobar analyses revealed that heritability varied between 0.69 and 0.90 (Fig. 1 and SI Table 1). Moreover, genetic and environmental contributions to 4 out of 5 lobes, namely frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital surface area, varied across SES (Table 1). Specifically, the heritability of surface area was higher for children from high-SES settings due to increased additive genetic effects, while environmental influences generally remained negligible-, or were lower in high SES settings. This was except unique environmental influences, which were slightly higher in high-SES settings for occipital surface area (Fig. 3).

The image displays splines representing heritability (h2 = A/(A + C + E); brown), along with its components: additive genetics (A; green), shared environment (C; dark orange) and unique environment (E; yellow) for cortical surface area across the standardized SES construct. The density distribution of SES is shown as a shaded area below the x-axis. The dotted grey line shows the total phenotypic variance (A + C + E).

Sulcal depth

Mean sulcal depth showed a heritability of h2 = 0.57 after controlling for relevant covariates. There was no significant interaction between the SES-index and the genetic and environmental factors (x2 = 1.08, Df = 3, p = 0.781, corrected p = 0.781), thus providing no indication that the heritability of global sulcal depth differs across SES levels. Lobar heritability varied between 0.34 and 0.61 (Fig. 1 and SI Table 1). Due to the low chi-square value and non-significance before correction, we did not proceed with lobar assessments of sulcal depth.

GWC

SNP-based heritability for GWC was h2 = 0.57 after controlling for age, sex, and population stratification. Likelihood ratio tests revealed an interaction between the SES index and genetic and environmental factors (x2 = 13.59, Df = 3, p = 0.004, corrected p = 0.010). The results indicate that the heritability of global GWC was higher in children from high-SES backgrounds due to increased additive genetic effects and a marked reduction in unique environmental influences, along with a slight decrease in shared environmental effects. In contrast, for children from low-SES backgrounds, unique environmental contributions exceed genetic contributions, accounting for a greater proportion of the variance in GWC under these circumstances (Fig. 4). Lobar analyses showed that the heritability of GWC varied between 0.48 and 0.59 (Fig. 1 and SI Table 1). Genetic and environmental factors varied across SES levels for four out of five lobes, namely the cingulate, frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes (Table 1), with patterns generally resembling the global pattern (Fig. 5), except for a somewhat varying contribution from shared environmental influences.

The image displays splines representing heritability (h2 = A/(A + C + E); brown), along with its components: additive genetics (A; green), shared environment (C; dark orange), and unique environment (E; yellow) for mean GWC across the standardized SES construct. The density distribution of SES is shown as a shaded area below the x-axis. The dotted grey line shows the total phenotypic variance (A + C + E).

The image displays splines representing heritability (h2 = A/(A + C + E); brown), along with its components: additive genetics (A; green), shared environment (C; dark orange), and unique environment (E; yellow) for GWC across the standardized SES construct. The density distribution of SES is shown as a shaded area below the x-axis. The dotted grey line shows the total phenotypic variance (A + C + E).

Genetic and environmental influence on general cognitive ability and moderation by parental SES

Baseline linear mixed effects modelling without genetic or environmental interaction terms revealed a SNP-based heritability for general cognitive ability of h2 = 0.57 after controlling for age, sex, and population stratification. Likelihood ratio tests comparing the baseline main effects-model and the interaction model between the SES index and additive genetic, shared environment, and unique environmental factors yielded a significant interaction (x2 = 29.60, Df = 3, p and corrected p ≤ 0.001), indicating that these factors, which constitute the heritability of general cognition, vary across SES levels. More specifically, the heritability of general cognition was higher for children from high-SES settings, due to increased additive genetic effects and a reduction in unique and, to a lesser extent, shared environmental influences. In contrast, for children from lower SES, genetic and environmental impact appeared similar, with unique environmental influences exceeding genetic contributions (Fig. 6).

The image displays splines representing heritability (h2 = A/ (A + C + E); brown), along with its components: additive genetics (A; green), shared environment (C; dark orange), and unique environment (E; yellow) for general cognitive ability across the standardized SES construct. The density distribution of SES is shown as a shaded area below the x-axis. The dotted grey line shows the total phenotypic variance (A + C + E).

Discussion

In a sample of over 9000 10-year-old children from the US, we found that differences in cortical thickness and surface area were primarily accounted for by genetic variation, while cortical folding and intensity showed moderate heritability. Across cortical metrics, the frontal lobe was the most heritable region. These estimates align with previous research32,33,34,35, yet our study shows that they do not fully generalize to children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, where regional cortical structure appears to be more related to unique environmental factors, at times exceeding genetic contributions. This parallels findings for cognitive abilities, including our own, and suggests that the balance between genetic and environmental contributions to child brain structure also shifts with socioeconomic context.

We find that cortical thickness and surface area are about 80% heritable in childhood, in line with general heritability estimates for T1-weighted cortical structure across the lifespan33. Our estimates show some discrepancies with those reported in a previous study using twin-based methods on the same sample (n = 1544)36. The study reported global thickness and surface area estimates of 66% and 95%, respectively, but with lower and more varied ROI based estimates. Discrepancies between the studies include their adjustment for self-reported ethnicity and three twin sites, whereas we included SES and genetic PCs in our models and harmonized cortical data across scanners. Leveraging a Canadian dataset of 57 monozygotic and 35 dizygotic 8-year-old twins, Yoon et al.37 reported vertex-wise heritability estimates of cortical thickness ranging from 0 to a maximum of 78% (left) and 67% (right)37. Assessing the twins' surface area in native imaging space resulted in interclass correlations that indicated left-to-right heritability asymmetries of approximately 62% and 46% respectively (Yoon et al.37). However, these studies had a more limited sample size.

We found that sulcal depth and GWC were both moderately heritable, with estimates approaching 60%. As a pure intensity metric, GWC is more susceptible to noise than geometry-based morphometry, potentially lowering the heritability estimate. Still, while no prior study has specifically assessed the heritability of either metric in childhood, our results are generally in line with previous studies of related metrics or in young adulthood. Maes and colleagues36 reported average convexity heritability below 40% across most ROIs. In young adulthood, Pizzagalli et al.11 estimated heritability to be 40% for mean sulcal depth in two separate Australian and American samples11, and Schmitt et al.38 reported heritability estimates of 49% for average convexity and 61% for mean curvature in the same American sample. A study of Vietnamese twins in midlife reported ROI based heritability for GWC ranging from 0 to 66%34, and a US-based twin study found approximately 50% heritability for a related intensity metric, the T1-weighted/T2-weighted (T1w/T2w)-ratio39.

The heritability of cortical morphometry and microstructure is lower in children from lower- compared to higher SES families. This pattern was evident for occipital and parietal thickness, as well as for most of lobar surface area and GWC, but not for cortical folding. While genetic differences accounted for most of cortical variation among children from high-SES backgrounds, in low-SES settings, unique environmental factors appeared to play a larger role, corresponding to-, or even exceeding the contribution of genetics. Shared environment, or specifically, being part of the same family, was minimally associated with cortical structure in our study. Both the inclusion of families with more than two participating siblings and the use of molecular genetic data help to better separate shared genetic from shared environmental effects40. The small shared environment contribution could still reflect limited statistical power, as only 28% of participants had enrolled siblings in the dataset, most of whom were from two-sibling families. The moderating effects of SES on the heritability, or on the genetic and environmental components, of cortical structure have not been previously tested. However, Chiang et al.41 used 705 Australian twins and their siblings to assess whether the heritability and additive genetic contributions on white matter fractional anisotropy were moderated by occupational status. While they found no moderating effect on the heritability estimate, occupational status interacted with the additive genetic component in isolated white matter voxels. Our results suggest that, much like previous (albeit inconsistent) findings for cognitive abilities15,27,28,30, and in line with our own cognitive findings, the genetic and environmental contributions to regional cortical morphometry and microstructure, key structural correlates of cognition, also vary with SES.

Our study cannot determine why unique environmental conditions associated with socioeconomic disadvantage play a greater role in explaining differences in child cortical structure. While our finding of positive SES moderation aligns with the Scarr-Rowe hypothesis, the underlying mechanism proposed by Scarr-Rowe may not. In our data, overall phenotypic variance in most cortical and general cognitive metrics was larger in lower-SES strata, suggesting that children from high-SES backgrounds are more similar to one another. Surface area, however, showed the opposite pattern. Still, if this were to generally reflect greater environmental homogeneity, it might align more closely with the “Saunders hypothesis”31 than with the individualized opportunities posited for high-SES contexts in the Scarr-Rowe framework29,30. Based on the overall pattern observed in our data, although speculative, it is also conceivable that in high SES environments, neurobiological processes, which are under strong genetic control42,43 and assumed to influence MRI based cortical structure, such as dendritic arborization, axon caliber, and cortical myelin3, cause differences in cortical structure. In contrast, in children from low SES families, certain unique environmental events or exposures (adverse or other) are more frequent and have broad non-specific effects on the same neurobiological processes, thus becoming the primary driver of cortical differences in these children. This is somewhat similar to the “social push” hypothesis, which posits that environmental as opposed to genetic factors become more central in explaining outcomes when conditions are extreme or adverse44.

There are several limitations to our study. First, although we aimed to create a broad SES construct, we were unable to reliably model the key subfactor, parental occupation. Occupation shows moderate correlations with income and education17,18, and captures symbolic capital or prestige45 and work-environmental conditions linked to physical and mental health46.

Second, the index is not sensitive to family size (“income-to-needs”) or geographic variation in cost of living across the US, and does not capture subjective, relative, or cultural aspects of SES47,48. Third, our study can only capture associations and cannot infer causation. Third, our analyses are based on SNP data within families and therefore do not account for rare genetic variants, which, in some cases, have profound impact on both brain structure and function. Fourth, our ACE model cannot capture non-additive genetic effects such as dominance or epistasis. Finally, unique environmental influences are not specifically modelled, and as such, we cannot probe which experiences or exposures underlie the non-shared environmental variance.

Children differ in their cortical brain architecture. Our findings show that genetic and environmental contributions to regional cortical thickness, most of surface area, and both global and regional microstructure vary between socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged children. Among socioeconomically advantaged children, inherited predispositions appear to play a larger role in brain structural differences, whereas in contexts of socioeconomic disadvantage, structural brain variation may more strongly reflect a child’s lived experience. Our study underscores the importance of considering context when interpreting brain heritability estimates.

Methods and materials

Participants

Data was acquired from the ABCD Study using the annual release 5.1 (https://data-dict.abcdstudy.org/?) and 3.0 for SNP-based information. The ABCD study consists of nearly 12,000 US children, approximately 9–10 years old at the time of study inclusion, as well as their parents, with planned follow-ups for 10 years. The protocol contains comprehensive assessments of demographic information, genetics, behavior, and brain structure and function49. Recruitment was generally conducted through the school system and was informed by sex, ethnicity, SES, and urbanicity. Parental informed consent as well as child assent were obtained for all participants. The Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Diego approved all aspects of the ABCD Study50, and the current study was conducted in line with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK 2019/943). All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed. Exclusion criteria and further details are presented in SI Methods.

The current study focused on baseline assessments from 11,868 participants. 1934 individuals were excluded due to missing data on either initial demographic, socioeconomic, neighborhood, cognitive, genetic ethnicity, family ID, scanner, imaging quality, or cortical macro- or microstructure-based variables of interest (SI Fig. 1). 213 individuals were excluded due to failing imaging-based quality control (QC) (described below), and 641 children were excluded due to missing or poor-quality SNP-based relatedness data. SI Fig. 2 shows the spread of SES and cognitive abilities for excluded individuals. The final sample thus consisted of 9080 children (4266 = females) aged 8.9–11.1 years (mean = 9.9 SD = 0.63). Two individuals who were assigned intersex-male at birth were recoded as male to enhance statistical robustness while ensuring the inclusion of all relevant individuals to our study. The sample comprised 6536 children from singleton families and 2544 children from sibship families, with counts reflecting enrolled siblings rather than the actual household size. Of these, 2428 children came from two-sibling families, 111 from three-sibling families, and five from a five-sibling family. The dataset included 670 twin pairs—261 monozygotic and 409 dizygotic—plus 7 complete triplet sets and 1 incomplete set in which only two of the three siblings met inclusion criteria.

Measurements of socioeconomic status and neighbourhood deprivation

Socioeconomic information was reported by a parent or guardian on behalf of themselves and a partner if relevant. Parental and partner education was assessed by indicating the highest grade level or degree received, on a 22-point scale. We recoded this scale to assimilate years of education (SI Table 4), and parental education was then defined as the highest educational score of either the reporting parent or their partner if applicable.

Parental and partner income was assessed by indicating their earnings before taxes and other deductions over the past 12 months on a 10-point scale. Total combined income was measured using the same scale, reflecting all sources of family income over the past 12 months. We recoded these income brackets to the median point, pragmatically setting the maximum of the top bracket to $350,000 (SI Table 4) based on online reports indicating that the threshold for the top 1% of U.S households in 2018 was $434,454.80 (https://dqydj.com/2018-average-median-top-household-income-percentiles/). Parental income was defined as the highest value reported from parent, partner, or combined income. To account for diminishing marginal utility, we applied a natural logarithm transformation to the income data.

Neighborhood deprivation was assessed using a composite score from the Area Deprivation Index (ADI) in the “Residential History Derived Scores” data file. The ADI is the scaled and weighted sum of 17 US census variables, including measures of poverty, education, housing, and employment, with a higher score indicating greater deprivation51.

In line with our pre-registration, we did not include assessments of occupation in this study. The rationale, detailed in the SI Information, is that the ABCD Occupation Survey does not rank occupations by status but instead provides status-neutral categories.

To create a single overarching SES index, we reduced z-scored parental education, parental income, and neighborhood deprivation by principal component analysis (PCA) in R using the “prcomp” package. PCA was chosen as it is a conventional data driven reduction that avoids a priori assumptions that SES-subfactors contribute equally or with preset weights and maximizes shared variance while remaining sensitive to noise differences. The first component, which explained 65% of the total variance, was extracted as the overarching “SES-index”. It correlated strongly with parental education (r = 0.84), parental income (r = 0.87), and neighborhood deprivation (r = –0.71). Higher values reflect higher income and education, and lower neighborhood deprivation (SI Fig. 3). See SI Fig. 4 for the distribution of SES and neighborhood-related variables in the final sample.

Genotype Data Processing and Relatedness Estimation. Genotype data were based on Data Release 3.0 and derived from saliva and blood samples52. Genotyping was conducted using the Affymetrix NIDA SmokeScreen Array53, containing 733,293 SNPs, with samples processed at Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (RUCDR). Initial DNA-based QC was performed by RUCDR, followed by further QC by the ABCD Data Analysis and Informatics Resource Center (DAIRC) using the Ricopili pipeline54. Pre-imputation steps followed TOPMed documentation and included identifying rare and common variants with PLINK v1.9, ensuring format consistency, converting to VCF format, and uploading to the TOPMed Imputation Server55. Data was then imputed, with mixed ancestry references to improve accuracy for diverse populations, and phased with Eagle v2.4 to determine allele arrangement on each chromosome.

Genetic relatedness among participants was estimated from the imputed genotype data55. The matrix of all pairwise genetic relatedness coefficients is referred to as the GRM, with each cell representing genetic similarity between pairs and self-relatedness along the diagonal. In samples of unrelated individuals, this matrix can be used to estimate the additive genetic contribution of all tagged and imputed SNPs1. When applied to samples of related individuals, Smith and colleagues24 suggested that all relatedness coefficients in the GRM could be set to zero between non-family members, such that the additive genetic effect is only correlated among members of the same family. The method was suggested to perform well when applied to cognitive phenotypes in the ABCD study, and was implemented in the current application.

For validation, we additionally calculated heritability using Falconer’s formula (see SI Methods). This traditional twin-based analysis was not pre-registered and used only as a supplementary check.

MRI acquisition, quality control, preprocessing, and scanner harmonization

Imaging data was acquired on 29 separate 3T scanners from Siemens Prisma, General Electric (GE) 750, and Philips. The T1w image was an inversion-prepared RF-spoiled gradient echo scan, with prospective motion correction when available, and a 1 mm isotropic voxel resolution. Detailed descriptions of acquisition parameters and child-friendly MRI practices are presented elsewhere56.

Raw QC of the T1w sequences was performed by the ABCD Data Analysis and Informatics Core. They used a standardized pipeline of automated and manual procedures that yielded a binary code for images recommended for inclusion57.

We relied on FreeSurfer version 7.1.1 runs provided by the ABCD consortium to perform volumetric segmentations and cortical surface reconstructions. This process includes defining the “white” and “pial” surface, which is the grey/white matter boundary and the grey/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) boundary, respectively58,59. Cortical thickness is then computed as the shortest vertex-wise distance between the white and pial surface, while vertex-wise surface area is calculated by summing the triangle areas converging at each particular vertex on the white surface. Vertex-wise-sulcal depth is calculated as the mm signed distance a vertex moves during an inflation operation from the white- to the inflated surface. Values are median-standardized and scaled based on variance, so that a positive value indicates outward motion more than the median of all vertices, indicating a deeper sulcus, whereas a negative value indicates inward motion and shallower sulci. GWC is calculated using intensity sampling from “rawavg.mgz”, where white matter is sampled 1 mm below-, and grey matter is sampled 30% above the white surface. The vertex-wise percentage is then computed as:

In this way, lower GWC reflects more similar grey and white matter, a blurring that is documented across youth development9. We used the global surface metrics from the tabulated files provided by the ABCD consortium, which are derived by averaging the values across all vertices, except for surface area, where values are summed into a total.

To examine the spatial variability of interactions between the SES index and h², we also performed analyses at lobal granularity (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and cingulate), reducing the Desikan atlas across hemispheres following FreeSurfer recommendations60. The fusiform gyrus, which spans both the occipital and temporal lobes, was assigned to the temporal lobe due to its stronger association with higher-order visual functions. The insula, which does not map cleanly to any conventional lobe and was represented by single values per hemisphere, was not included in lobar analyses. Surface area was summed, while the remaining metrics were averaged using a weighted-mean approach based on surface area.

In addition to raw image QC, we excluded individuals whose original surface showed extreme topological defects (i.e., holes, bumps, or handles), defined as exceeding 4 standard deviations from the mean on the “defect topology” variable for the left and right hemispheres.

To adjust for systematic and unwanted scanner-related variance, imaging metrics were subsequently imported to R, and the package neuroCombat61 was employed to harmonize data across each of the 29 scanners. We included relevant covariates to our model, namely age, sex, parental education, parental income, neighborhood deprivation, general cognitive ability, family ID, and 32 genetic PCs, to preserve such variance during the harmonization procedure. Box plots of global MRI measures pre- and post-neuroCombat adjustments are presented in SI Fig. 7–10.

Measurement of general cognitive ability

Cognitive abilities were assessed using the neurocognitive battery “the NIH toolbox”62,63,64, administered on an iPad while monitored by a research assistant. The battery comprises seven tasks, covering episodic memory, executive function, attention, working memory, processing speed, and language65,66. As a measure of general cognitive ability, we used the uncorrected total composite score of cognition. Figure 7 shows correlations between age, the SES-index, general cognitive ability, and global imaging metrics.

Statistics and reproducibility

This study was pre-registered, where full statistical code is also available67. For the final sample (n = 9080), we fit a mixed effects “baseline model” for each imaging metric (cortical thickness, surface area, sulcal depth, and grey/white-matter contrast) and for general cognitive ability, using the svcm package in R68. These models, for individual \(i\) in family \(j\), include all main effects but no interaction terms and were specified as:

In this linear model, (\(y\)) represented the cortical or cognitive metric, \(\gamma\) was the fixed effects of the covariates (e.g., age, se,x and 32 genetic PCs derived by Fan et al.55, related to minimizing population stratification), and \(\beta\) was the fixed effect of the SES index (s). The term \(a\) was a person-varying random additive genetic effect, distributed across individuals according to the GRM with variance \({\sigma }_{a}^{2}.\) For example, for siblings k and l, the GRM at position kl has a value of ≈½, reflecting their estimated sharing of genetic material. If the siblings are monozygotic twins, the value is ≈1. These values represent the expected correlation in phenotypes that arise because of additive genetic effects. Of note, other sources of variation may lead to similar patterns, for example, if monozygotic twins are treated more similar by their parents. The term \(c\) was a family-varying random effect, independent across families with variance \({\sigma }_{c}^{2}\). However, other sources that increase resemblance among relatives may lead to similar patterns, for example, non-additive genetic effects or assortative mating. The term \(e\) was a person-varying random environmental/residual effect independent across individuals with variance \({\sigma }_{e}^{2}\). This term has the same structure as the residual in other linear models and captures other sources of variability that are not correlated across individuals, such as classical measurement error. Under this model, the genetic and environmental components of variance do not depend on the SES index. Of note, the preregistration detailed a genetic (a) + non-genetic (e) model, but with extensive family membership data available, we chose to further parse the non-genetic signal by also modelling the variance shared between family members (c). Heritability (h2) was calculated as the proportion of total variance, conditional on the fixed effects, explained by genetics:

In a secondary set of “interaction models”, we expanded the baseline model to include interaction terms between the SES index and random effects:

The three new terms \({s}_{j}{a}_{2{ij}}+{s}_{j}{c}_{2j}+{s}_{j}{e}_{2{ij}}\) were random slopes of \({s}_{j}\) regarding the genetic and environmental background factors, which had the consequence of inducing heteroscedastic variance. The random slope terms had similar distributions across individuals as in the baseline model, but with variances \({\sigma }_{a2}^{2}\), \({\sigma }_{c2}^{2}\), and \({\sigma }_{e2}^{2}\). Importantly, the genetic and environmental components of variance are now quadratic functions of SES. For the additive genetic variance, the function was:

The shared and unique environmental variance had similar functions with respect to the SES-index. This specification of the models is similar to what Purcell69 referred to as “quantitative interactions”. Consequently, the heritability cannot be evaluated without reference to the SES-index:

The baseline models were nested in the interaction models, and we obtained joint tests for interaction terms with likelihood ratio tests. All hypothesis tests were two-sided. Adjustments for multiple comparisons were performed using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for false discovery rate (FDR), separately for global and lobar analyses. Statistical significance was defined as FDR-adjusted p ≤ 0.05. Of note, we left factors associated with SES and brain structure (e.g., pubertal timing, early-life trauma, and pre-/perinatal risk) unadjusted by design, as they relate to the SES context of interest. Future mechanism-focused studies should model them explicitly.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process: The manuscript was written by the corresponding author in collaboration with the co-authors. ChatGPT 4.0 was used to refine the English language and improve readability. After using this tool, the corresponding author reviewed and edited the content as needed takes full responsibility for all content within the manuscript.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data were acquired from the ABCD Study via the NIMH Data Archive (NDA) using annual release 5.1 (https://data-dict.abcdstudy.org/) and release 3.0 for SNP-based information, under controlled access (Data Use Certification). Individual-level data are not publicly available; eligible researchers can apply for access through the NDA.

Code availability

This study was pre-registered at https://osf.io/azucp, where the full statistical code is also available.

References

Yang, J., Zeng, J., Goddard, M. E., Wray, N. R. & Visscher, P. M. Concepts, estimation and interpretation of SNP-based heritability. Nat. Genet. 49, 1304–1310 (2017).

Bethlehem, R. A. I. et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 604, 525–533 (2022).

Norbom, L. B. et al. New insights into the dynamic development of the cerebral cortex in childhood and adolescence: integrating macro- and microstructural MRI findings. Prog. Neurobiol. 204, 102109 (2021).

Girault, J. B. et al. Cortical Structure and cognition in infants and toddlers. Cereb. Cortex 30, 786–800 (2020).

Grydeland, H., Walhovd, K. B., Tamnes, C. K., Westlye, L. T. & Fjell, A. M. Intracortical myelin links with performance variability across the human lifespan: results from T1- and T2-Weighted MRI myelin mapping and diffusion tensor imaging. J. Neurosci. 33, 18618–18630 (2013).

Norbom, L. B. et al. Maturation of cortical microstructure and cognitive development in childhood and adolescence: a T1w/T2w ratio MRI study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 4676–4690 (2020).

Oschwald, J. et al. Brain structure and cognitive ability in healthy aging: a review on longitudinal correlated change. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 1–57 (2019).

Boedhoe, P. S. W. et al. Subcortical brain volume, regional cortical thickness, and cortical surface area across disorders: findings from the ENIGMA ADHD, ASD, and OCD working groups. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 834–843 (2020).

Norbom, L. B. et al. Probing brain developmental patterns of myelination and associations with psychopathology in youths using gray/white matter contrast. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 389–398 (2019).

Fernandez-Cabello, S. et al. Associations between brain imaging and polygenic scores of mental health and educational attainment in children aged 9–11. NeuroImage 263, 119611 (2022).

Pizzagalli, F. et al. The reliability and heritability of cortical folds and their genetic correlations across hemispheres. Commun. Biol. 3, 510 (2020).

Strike, L. T. et al. Genetic complexity of cortical structure: differences in genetic and environmental factors influencing cortical surface area and thickness. Cereb. Cortex 29, 952–962 (2019).

De Zeeuw, E. L. et al. The moderating role of SES on genetic differences in educational achievement in the Netherlands. npj Sci. Learn. 4, 13 (2019).

Marees, A. T. et al. Genetic correlates of socio-economic status influence the pattern of shared heritability across mental health traits. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 1065–1073 (2021).

Rowe, D. C., Jacobson, K. C. & Van Den Oord, E. J. C. G. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Vocabulary IQ: oarental Education Level as Moderator. Child Dev. 70, 1151–1162 (1999).

Scarr-Salapatek, S. Race, Social Class, and IQ: oopulation differences in heritability of IQ scores were found for racial and social class groups. Science 174, 1285–1295 (1971).

Farah, M. J. The neuroscience of socioeconomic status: correlates, causes, and consequences. Neuron 96, 56–71 (2017).

Norbom, L. B. et al. Parental socioeconomic status is linked to cortical microstructure and language abilities in children and adolescents. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 56, 101132 (2022).

Norbom, L. B. et al. Parental education and income are linked to offspring cortical brain structure and psychopathology at 9–11 years. JCPP Adv. e12220 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12220 (2024).

Rakesh, D. & Whittle, S. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain – a systematic review of neuroimaging findings in youth. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 130, 379–407 (2021).

Bergen, S. E., Gardner, C. O. & Kendler, K. S. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 10, 423–433 (2007).

Briley, D. A. & Tucker-Drob, E. M. Explaining the increasing heritability of cognitive ability across development: a meta-analysis of longitudinal twin and adoption studies. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1704–1713 (2013).

Haworth, C. M. A. et al. The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Mol. Psychiatry 15, 1112–1120 (2010).

Smith, D. M. et al. Heritability estimation of cognitive phenotypes in the ABCD study® using mixed models. Behav. Genet. 53, 169–188 (2023).

Fischbein, S. IQ and social class. Intelligence 4, 51–63 (1980).

Figlio, D. N., Freese, J., Karbownik, K. & Roth, J. Socioeconomic status and genetic influences on cognitive development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13441–13446 (2017).

Gottschling, J. et al. Socioeconomic status amplifies genetic effects in middle childhood in a large German twin sample. Intelligence 72, 20–27 (2019).

Tucker-Drob, E. M. & Bates, T. C. Large cross-national differences in gene × socioeconomic status interaction on intelligence. Psychol. Sci. 27, 138–149 (2016).

Harden, K. P., Turkheimer, E. & Loehlin, J. C. Genotype by environment interaction in adolescents’ cognitive aptitude. Behav. Genet. 37, 273–283 (2007).

Tucker-Drob, E. M., Rhemtulla, M., Harden, K. P., Turkheimer, E. & Fask, D. Emergence of a gene × socioeconomic status interaction on infant mental ability between 10 months and 2 years. Psychol. Sci. 22, 125–133 (2011).

Lin, M.-J. The social and genetic inheritance of educational attainment: genes, parental education, and educational expansion. Soc. Sci. Res. 86, 102387 (2020).

Eyler, L. T. et al. A comparison of heritability maps of cortical surface area and thickness and the influence of adjustment for whole brain measures: a magnetic resonance imaging twin study. Twin Res. Hum. Genet 15, 304–314 (2012).

Jansen, A. G., Mous, S. E., White, T., Posthuma, D. & Polderman, T. J. C. What twin studies tell us about the heritability of brain development, morphology, and function: a review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 25, 27–46 (2015).

Panizzon, M. S. et al. Genetic and environmental influences of white and gray matter signal contrast: a new phenotype for imaging genetics?. NeuroImage 60, 1686–1695 (2012).

Zhao, B. et al. Heritability of regional brain volumes in large-scale neuroimaging and genetic studies. Cereb. Cortex 29, 2904–2914 (2019).

Maes, H. H. M. et al. Genetic and environmental variation in continuous phenotypes in the ABCD study®. Behav. Genet. 53, 1–24 (2023).

Yoon, U., Fahim, C., Perusse, D. & Evans, A. C. Lateralized genetic and environmental influences on human brain morphology of 8-year-old twins. NeuroImage 53, 1117–1125 (2010).

Schmitt, J. E., Raznahan, A., Liu, S. & Neale, M. C. The heritability of cortical folding: evidence from the human connectome project. Cereb. Cortex 31, 702–715 (2021).

Schmitt, J. E., Raznahan, A., Liu, S. & Neale, M. C. The genetics of cortical myelination in young adults and its relationships to cerebral surface area, cortical thickness, and intelligence: a magnetic resonance imaging study of twins and families. NeuroImage 206, 116319 (2020).

Williams, C. J. On the covariance between parameter estimates in models of twin data. Biometrics 49, 557–568 (1993).

Chiang, M.-C. et al. Genetics of white matter development: a DTI study of 705 twins and their siblings aged 12 to 29. NeuroImage 54, 2308–2317 (2011).

Jan, Y.-N. & Jan, L. Y. The control of dendrite development. Neuron 40, 229–242 (2003).

Liu, S., Li, A., Zhu, M., Li, J. & Liu, B. Genetic influences on cortical myelination in the human brain. Genes Brain Behav. 18, e12537 (2019).

Raine, A. Biosocial studies of antisocial and violent behavior in children and adults: a review. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 30, 311–326 (2002).

Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital (1986). Cult. Theory. Anthol. 1, 949 (2011).

Fujishiro, K., Xu, J. & Gong, F. What does “occupation” represent as an indicator of socioeconomic status?: exploring occupational prestige and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 71, 2100–2107 (2010).

Liu, W. M. et al. Using social class in counseling psychology research. J. Counsel. Psychol. 51, 3–18 (2004).

Yosso, T. Whose cultural has capital. A Critical Race Theory Discussion Of Community Cultural Wealth (Taylor & Francis, 2005).

Feldstein Ewing, S. W., Bjork, J. M. & Luciana, M. Implications of the ABCD study for developmental neuroscience. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 161–164 (2018).

Auchter, A. M. et al. A description of the ABCD organizational structure and communication framework. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 8–15 (2018).

Kind, A. J. H. et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intern Med. 161, 765 (2014).

Uban, K. A. et al. Biospecimens and the ABCD study: rationale, methods of collection, measurement and early data. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 97–106 (2018).

Baurley, J. W., Edlund, C. K., Pardamean, C. I., Conti, D. V. & Bergen, A. W. Smokescreen: a targeted genotyping array for addiction research. BMC Genom. 17, 145 (2016).

Lam, M. et al. RICOPILI: rapid Imputation for COnsortias PIpeLIne. Bioinformatics 36, 930–933 (2020).

Fan, C. C. et al. Genotype data and derived genetic instruments of Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study® for better understanding of human brain development. Behav. Genet. 53, 159–168 (2023).

Casey, B. J. et al. The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 43–54 (2018).

Hagler, D. J. et al. Image processing and analysis methods for the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. NeuroImage 202, 116091 (2019).

Dale, A. M., Fischl, B. & Sereno, M. I. Cortical surface-based analysis. NeuroImage 9, 179–194 (1999).

Fischl, B., Sereno, M. I. & Dale, A. M. Cortical surface-based analysis. NeuroImage 9, 195–207 (1999).

Klein, A. & Tourville, J. 101 labeled brain images and a consistent human cortical labeling protocol. Front. Neurosci. 6, 33392 (2012).

Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. NeuroImage 167, 104–120 (2018).

Bleck, T. P., Nowinski, C. J., Gershon, R. & Koroshetz, W. J. What is the NIH Toolbox, and what will it mean to neurology?. Neurology 80, 874–875 (2013).

Gershon, R. C. et al. NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology 80, S2-6 (2013).

Hodes, R. J., Insel, T. R., Landis, S. C. & On behalf of the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research. The NIH toolbox: setting a standard for biomedical research. Neurology 80, S1 (2013).

Luciana, M. et al. Adolescent neurocognitive development and impacts of substance use: overview of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) baseline neurocognition battery. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 32, 67–79 (2018).

Thompson, W. K. et al. The structure of cognition in 9 and 10 year-old children and associations with problem behaviors: findings from the ABCD study’s baseline neurocognitive battery. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 36, 100606 (2019).

Norbom, L. B. Searching for hidden socioeconomic layers in the heritability of child cortical structure. Preregistration at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AZUCP (2024).

Eilertsen, E. moen. svcm - Fit structured variance component models with sparse relationship matrices. (2021).

Purcell, S. Variance components models for gene–environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Res. 5, 554–571 (2002).

Acknowledgements

Data was obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), which is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers: U01DA041048,U01DA050989, U01DA051016,U01DA041022,U01DA051018,U01DA051037, U01DA050987,U01DA041174,U01DA041106,U01DA041117, U01DA041028,U01DA041134,U01DA050988,U01DA051039, U01DA041156,U01DA041025,U01DA041120,U01DA051038, U01DA041148,U01DA041093,U01DA041089,U24DA041123, U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https:// abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/ consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and Innovation program (802998), the Research Council of Norway (#288083, #300767, #323951), and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (#2021070, #2023012, #500189).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Linn B. Norbom led the project as first author and was central to all stages. Espen M. Eilertsen consulted on genetics, set up the initial heritability and ACE analyses and code, drafted the genetic-modelling methods, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Andreas Dahl consulted on genetic modelling in the ABCD sample, guided variable selection based on ABCD literacy, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Valerie Karl contributed ABCD expertise, advised on SES and variables related to population stratification, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Lars T. Westlye provided access to the ABCD dataset, advised on study framing and key considerations, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Christian K. Tamnes, project PI, co-conceived the study, defined the scope and analytic strategy, oversaw the work, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Lu Zhao and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Norbom, L.B., Eilertsen, E.M., Dahl, A. et al. Socioeconomic context influences the heritability of child cortical structure. Commun Biol 8, 1607 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09022-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09022-7