Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a major global public health burden. The mechanisms through which glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) can be suppressed in individuals with obesity-derived type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have not been elucidated. Compared to normal subjects, the expression of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is upregulated in the islets of patients with obesity and T2DM. However, the role of PEDF in β-cells is unclear. This study employed male PEDF transgenic and knockout mice to assess β-cell function through oral glucose tolerance tests and GSIS assays. Complementary cell line experiments elucidated underlying mechanisms, collectively demonstrating the role of PEDF in regulating insulin secretion. PEDF suppressed GSIS by downregulating the SNARE complex, which suppresses the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Thus, targeting PEDF is a potential therapeutic strategy for treating T2DM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence and fatality rates of diabetes, a major chronic non-communicable disease, are increasing worldwide1. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is estimated to account for 90%-95% of all diabetes cases2. The major pathological mechanisms of T2DM, a complex disease, are peripheral insulin resistance and islet β-cell dysfunction3. Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) is a key characteristic of pancreatic islet β-cell dysfunction and represents a central pathological feature in T2DM4.

GSIS is characterized by a rapid phase, followed by a delayed phase5. Both phases of insulin secretion are impaired in patients with T2DM6, with rapid phase impairments reported to play a prominent role7. The rapid phase of GSIS reflects the secretory ability of readily releasable pool particles that are ready to be released. The main factors influencing the rapid phase are calcium ion influx8 and tSNARE complex (comprising SNAP25, Syntaxin 1 A and VAMP2) formation6,9. Impaired GSIS is considered an early pathological feature of T2DM, contributing to aberrant upregulation of blood glucose levels7,8,10.

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance and T2DM11. Insulin resistance alone is not sufficient to cause T2DM12. The effects of obesity on GSIS and the underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. Therefore, the identification of key molecules associated with insulin secretion will aid in the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies for diabetes.

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), an adipokine that belongs to the serine protease inhibitor (serpin) family13, is expressed in the adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, liver, pancreas, gallbladder, kidney and reproductive tissues14. Elevated plasma PEDF, an anti-angiogenic factor, is strongly associated with the progression of diabetic vascular complications, particularly retinopathy and nephropathy15,16. Previous studies have demonstrated that PEDF is upregulated in metabolic diseases, such as diabetes15,17 and obesity18,19. Additionally, PEDF is associated with the pathogenesis of insulin resistance19,20,21. In obesity, PEDF inhibits insulin signaling and promotes insulin resistance by suppressing the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, the established primary sources of circulating PEDF19. However, the direct inhibitory effects of upregulated PEDF on insulin secretion, and its consequent role in pancreatic islet β-cell dysfunction, have not been elucidated. This study aimed to investigate the regulatory effects of PEDF on insulin secretion using animal and cell models.

Results

PEDF promotes the progression of diabetes

The GSE50398 dataset downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database was used to analyze the differential expression of SERPINF1 (which encodes PEDF). SERPINF1 was among the differentially expressed genes commonly identified in the comparisons between the healthy control and obesity as well as the healthy control vs obesity with T2DM. Gene Ontology enrichment analysis revealed that genes associated with insulin secretion pathways were strongly associated with T2DM (Fig. S1A). SERPINF1 expression was upregulated in patients with obesity and T2DM with obesity compared to the healthy control (Table S3). Sequencing analysis revealed that the islet SERPINF1 levels in patients with obesity and T2DM were increased compared with those in healthy controls (Fig. 1A).

A Relative mRNA levels of SERPINF1 from healthy control (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24), overweight (24 ≤ BMI < 27), obesity (BMI ≥ 27) and obesity with T2DM patients (n = 15, 37, 14 and 10, GSE50398). B Schematic diagram of animal experimental design. C Blood glucose curves of GTT from 9-months-old (9 M) WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 6). D Fasting blood glucose (FBG) from 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 6). E Glucose area under curve (GAUC) from 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 6). F Blood glucose curves of GTT from 12-months-old (12 M) WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 8). G FBG from 12-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 8). H GAUC from 12-months-old (12 M) WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 8). I Blood glucose curves of GTT from WT-KO-CD, WT-KO-HFD and PEDF-KO-HFD mice (n = 8). J FBG from WT-KO-CD, WT-KO-HFD and PEDF-KO-HFD mice (n = 8). K GAUC from WT-KO-CD, WT-KO-HFD and PEDF-KO-HFD mice. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, #p < 0.05, * vs WT-KO-CD, # vs WT-KO-HFD. B images created in BioRender; Gan, X. (2025), https://BioRender.com/l0n1psj.

Subsequently, glucose tolerance and insulin-related parameters were assessed in transgenic mice (Fig. 1B). Glucose tolerance in PEDF transgenic (PEDF-TG) mice aged 6 months was not markedly altered (Fig. S1B–D). However, PEDF-TG mice aged 9 months presented increased fasting glucose levels, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased glucose area under the curve (GAUC) compared to WT-TG mice (Fig. 1C–E). Compared with WT-TG mice, the 12-month-old PEDF-TG mice also exhibited impaired glucose tolerance (Fig. 1F–H). No significant difference in body weight was observed between PEDF-TG mice and WT-TG mice aged 3 to 12 months (Fig. S1E). Thus, PEDF upregulation has a pathogenic role in T2DM compared to healthy control. To further explore whether PEDF plays a role in T2DM, we constructed a PEDF-KO model under a high-fat diet, while WT-KO-CD and WT-KO-HFD served as controls. Prior to HFD feeding, GTT and insulin tolerance test (ITT) experiments demonstrated that PEDF-KO mice showed no significant changes in glucose tolerance or insulin sensitivity at 2 months of age (Fig. S1F–H). Consistent with its role as an adipokine, HFD feeding induced increases in weight, islet PEDF protein and circulating PEDF levels respectively (Fig. S1I–K), establishing systemic and local PEDF upregulation in metabolic dysfunction compared to WT-CD. PEDF-KO-HFD did not significantly affect the fasting glucose level (Fig. 1J) and ITT (Fig. S1L–O) but markedly improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 1I) and GAUC (Fig. 1K). Additionally, administration of a PEDF-neutralizing antibody (PEDF Ab) to high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mice similarly improved glucose tolerance (Fig. S1P–R).

PEDF inhibits insulin secretion in islet β-cells

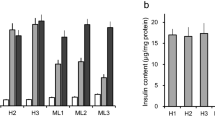

Immunofluorescence staining and quantitative analyses of islets revealed that the expression of insulin was similar between WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice. These results indicate that PEDF does not affect the expression of insulin in islets (Fig. S2A, B). The GSIS assay demonstrated that PEDF-TG mice aged 9 months exhibited impaired insulin secretion in 15 min (Fig. 2A). The insulinogenic index (IGI) is a metric used to measure islet β-cell function. The ratio of changes in insulin and blood glucose significant decreased at 15 min (∆I15/∆G15), suggesting impaired islet β-cell function (Fig. 2B, C). The ∆I30/∆G30 values in the PEDF-KO-HFD-fed mice were greater than those in WT-KO-HFD-fed mice. These findings indicated that PEDF KO improved insulin secretion in HFD-induced T2DM (Fig. 2D–F). Consistently, the secretion of insulin decreased in primary islets isolated from WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (Fig. 2G). Thus, PEDF inhibits insulin secretion by β-cells both in vivo and in vitro.

A Serum insulin, B ΔG15/ΔI15 and C ΔG30/ΔI30 of GSIS 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 6). D Serum insulin, E ΔG15/ΔI15 and F ΔG30/ΔI30 of GSIS from WT-KO-HFD and PEDF-KO-HFD mice (n = 7). G GSIS of primary islets in WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (a minimum of 20 islets were isolated from each mouse, with n = 3 mice per group.). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

PEDF inhibits insulin secretion by downregulating the tSNARE complex

RIN-m5f and Beta-TC-6 cells were treated with recombinant PEDF (rPEDF) for 24 h, incubated with Fluo-4AM (a fluorescent probe for calcium ions), and observed under a fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence intensity did not significantly differ between the control and treatment groups, indicating that PEDF does not affect calcium influx (Fig. S3A, B). Next, this study examined whether PEDF exerts regulatory effects on the tSNARE complex by evaluating the expression of the components of the complex (Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25, and VAMP2). Immunofluorescence analysis of islets revealed that the expression of SNAP25 in PEDF-TG mice was lower than that in WT-TG mice (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analyses of isolated primary islets revealed decreased expression of the tSNARE complex at both the protein and mRNA levels in PEDF-TG mice (Fig. 3B, C). Treatment of β-cells with rPEDF significantly downregulated the expression of these genes (Fig. 3D, E) and proteins (Fig. 3F, G) of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25, and VAMP2. The expression patterns of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25, and VAMP2 in rPEDF-treated cells were similar to those in PEDF-overexpressing β-cells (pET30a +/PEDF-transfected cells) (Fig. 3H–K). The expression of SNAP25 in the PEDF-KO-HFD-fed mice was greater than that in the WT-KO-HFD-fed mice (Fig. 3L), whereas PEDF-neutralizing antibody treatment resulted in a parallel trend (Fig. 3M). These findings suggest that PEDF downregulates the tSNARE components through transcriptional regulation.

A DAPI (blue), Insulin (green) and SNAP25 (red) immunostaining in islets from 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (a minimum of 5 islets were captured by microscope from each mouse, n = 6). Scale bar = 50 μm. B Western blot analysis of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 in isolated primary islets from 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 3). C Relative mRNA levels of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 in isolated primary islets from 9-months-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (n = 3). Relative mRNA levels in RIN-m5f (D) and Beta-TC-6 (E) treated with PBS and rPEDF (n = 3). Western blot analysis of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 in RIN-m5f (F) and Beta-TC-6 (G) treated with PBS and rPEDF. Relative mRNA levels of SERPINF1, Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 in RIN-m5f (H) and Beta-TC-6 (I) treated with pcDNA and pET30a (+)/PEDF. Western blot analysis of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 in RIN-m5f (J) and Beta-TC-6 (K) treated with pcDNA and pET30a (+)/PEDF. L DAPI (blue) and SNAP25 (red) immunostaining in islets from WT-KO-HFD and PEDF-KO-HFD mice (a minimum of 5 islets were captured by microscope from each mouse, n = 6). M DAPI (blue), Insulin (green) and SNAP25 (red) immunostaining in islets from CD-IgG, HFD-IgG and HFD-PEDF Ab mice (a minimum of 5 islets were captured by microscope from each mouse, n = 6). Scale bar = 50 μm; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

PEDF downregulates Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25, and VAMP2 through FOXO1

FOXO1, a transcription factor22, regulates the tSNARE complex and insulin secretion23,24,25. Staining of mouse pancreas sections revealed that the nuclear accumulation of FOXO1 in PEDF-TG mice was greater than that in WT-TG mice (Fig. 4A). Immunofluorescence analysis of pancreatic sections from HFD-fed mice subjected to PEDF-neutralizing antibody treatment demonstrated suppressed nuclear translocation of FOXO1 (Fig. 4B). Neither rPEDF treatment nor PEDF overexpression significantly affects the mRNA level of Foxo1 in RIN-m5f and Beta-TC-6 cells (Fig. S4A–C). Next, the nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins of rPEDF-treated BTC-6 cells were extracted to examine the FOXO1 levels. Western blot analysis revealed that rPEDF significantly increased the nuclear level of FOXO1 (Fig. 4C). The phosphorylation of FOXO1 prevents its nuclear translocation and inhibits its transcriptional activity. In quantitative analysis of isolated primary islets, PEDF-TG mice exhibited reduced expression of p-FOXO1(S256) compared to WT-TG mice (Fig. 4D). And compared to untreated group, treatment with different concentrations of rPEDF downregulated the levels of p-FOXO1(S256) in RIN-m5f and BTC-6 cells (Fig. 4E, F). Consistently, immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that rPEDF upregulated the nuclear translocation of FOXO1 (Fig. 4G).

A Immunofluorescence staining of islets from 6-month-old WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice (a minimum of 5 islets were captured by microscope from each mouse, n = 6), showing DAPI (blue), FOXO1 (red), and statistical analysis of the nuclear-to-total FOXO1 intensity ratio. B Immunofluorescence staining of islets from CD-IgG, HFD-IgG, and HFD-PEDF Ab mice (a minimum of 5 islets were captured by microscope from each mouse, n = 3), showing DAPI (blue), FOXO1 (red), with statistical analysis of the nuclear-to-total FOXO1 intensity ratio. Scale bar = 50 μm. C Western blot analysis of nuclei and cytoplasmic FOXO1 in Beta-TC-6 treated with PBS and rPEDF. D Western blot analysis of p-FOXO1(S256) expression levels in primary islets of WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice. Western blot analysis of p-FOXO1 (S256) and FOXO1 in RIN-m5f (E) and Beta-TC-6 (F) treated with PBS and rPEDF. G Immunofluorescence staining of Beta-TC-6 cells treated with PBS or rPEDF, showing DAPI (blue), Insulin (green), and FOXO1 (red), with statistical analysis of the nuclear-to-total FOXO1 intensity ratio. Scale bar = 10 μm; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

PEDF inhibits the phosphorylation of FOXO1 through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

Akt phosphorylates the serine (Ser256, Ser319) and threonine (Thr24) residues of FOXO1 in the cytoplasm of β-cells24,26. Treatment with rPEDF downregulated p-Akt (S473) expression and upregulated total Akt expression (Fig. 5A, B). Next, the RIN-m5f cells were treated with rPEDF for 24 h, followed by treatment with the PI3K activator 740 Y-P. The levels of p-Akt (S473) and p-FOXO1 (S256) in the PEDF + 740 Y-P groups were significantly greater than those in the PEDF group. These findings suggest that 740 Y-P inhibited the regulatory effects of PEDF on FOXO1 (Fig. 5C, D). Thus, PEDF inhibits the phosphorylation of FOXO1 by suppressing the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Western blot analysis of p-Akt (S473) and Akt in RIN-m5f (A) and Beta-TC-6 (B) treated with PBS and rPEDF. Western blot analysis of p-FOXO1 (S256) and p-Akt (S473) in RIN-m5f (C) and Beta-TC-6 (D) treated with PBS, rPEDF and rPEDF + 740 Y-P. Western blot analysis of p-FOXO1 (S256), Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25 and VAMP2 of RIN-m5f (E) and Beta-TC-6 (F) treated with siNC, siNC + rPEDF and siATGL + rPEDF. G Illustration of PEDF suppressing insulin secretion. G images created in BioRender; Zhen, Z. (2025), https://BioRender.com/l9t57c5.

PEDF regulates islet β-cell activity through the receptor ATGL

Adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL, the gene name is PNPLA2) and laminin receptor (LR, the gene name is RPSA) serve as receptors for secreted PEDF27. Immunohistochemical analysis of islets revealed that compared with WT-TG, ATGL expression was downregulated in PEDF-TG mice and that LR expression was not detected (Fig. S5A). RT-PCR was performed to detect the expression levels of PNPLA2 and RPSA in RIN-m5f and BTC-6 cells. Analysis of the Quantification Cycle (Cq) revealed that the Cq value for RPSA was higher than that for PNPLA2, indicating an extremely low expression level of RPSA (gene of LR) (Fig. S5B, C). RIN-m5f and Beta-TC-6 cells were transfected with ATGL-siRNA and treated with rPEDF. Compared with si-NC, transfection with si-ATGL mitigated the rPEDF-induced downregulation of Syntaxin 1A, SNAP25, VAMP2 and p-FOXO1 (S256) in RIN-m5f and Beta-TC-6 cells. These findings indicate that ATGL serves as a receptor for PEDF in β-cells (Fig. 5E, F).

Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that PEDF-TG mice exhibit a diabetic phenotype, which progressively worsens with age. The results of in vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrated that PEDF does not affect insulin synthesis but inhibits insulin secretion. The primary targets for the inhibitory effects of PEDF on rapid-phase GSIS are the components of the SNARE complex. PEDF inhibited the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, promoted FOXO1 nuclear translocation, and downregulated the expression of tSNARE complex components through its receptor ATGL. This study, for the first time, demonstrated that PEDF upregulation inhibits rapid-phase insulin secretion and elucidated the underlying molecular mechanisms, offering new insights and targets for managing impaired GSIS and pancreatic islet β-cell dysfunction in diabetes.

Clinical data and our previous research indicate that PEDF is upregulated in T2DM15,17,28. Hence, this study elucidates an important role for PEDF and its underlying mechanism of action in T2DM. PEDF was reported to increase 24 h insulin secretion levels in the rat β-cell line BRIN-BD1129, which focused on the role of physiological concentrations of PEDF. However, the role of PEDF in β-cell function under pathological conditions remains unclear. In this study, we demonstrated that elevated PEDF significantly impaired GSIS by suppressing the expression of the tSNARE complex, revealing a novel inhibitory role of PEDF in insulin secretion. Therefore, PEDF serves not only as a diagnostic marker but also as a potential therapeutic target in T2DM. PEDF upregulation may lead to islet β-cell dysfunction and induce T2DM. However, the specific mechanisms underlying the upregulation of PEDF in obesity and T2DM have not been elucidated and should be the focus of future studies.

The transcription factor FOXO1 regulates the pathogenesis of diabetes. Under metabolic stress conditions, FOXO1 maintains the function of β-cells24. FOXO1 deficiency leads to the dedifferentiation of β-cells30. The dephosphorylation and nuclear retention of FOXO1 mediate the downregulation of the tSNARE complex in β-cells. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway promotes the phosphorylation of FOXO1, facilitating its entry into the cytoplasm31. Previous studies have reported that PEDF inhibits the Akt signaling pathway32,33. Similarly, sustained activation of the Akt signaling pathway has been reported to maintain both the functionality and survival of pancreatic β-cells34,35. Thus, PEDF exerts regulatory effects on β-cells via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

The known receptors for PEDF are ATGL and LR27. The expression of ATGL, but not that of LR, was upregulated in pancreatic β-cells. Therefore, we hypothesize that ATGL is the primary receptor for PEDF in pancreatic β-cells. PEDF interacts with ATGL to inhibit the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Similar results were achieved with ATGL knockdown. The specific regulatory effects of ATGL on the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway must be elucidated further.

In conclusion, this study revealed the mechanisms through which PEDF inhibits GSIS. PEDF inhibits the expression of essential proteins in the tSNARE complex by promoting FOXO1 nuclear translocation and retention, inhibiting vesicle fusion, and impairing rapid-phase GSIS. Additionally, PEDF regulates FOXO1 through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway by suppressing Akt activity and downregulating FOXO1 phosphorylation. This leads to the nuclear translocation and retention of FOXO1. Thus, this study elucidated the key regulatory molecules and mechanisms through which PEDF inhibits GSIS and disrupts pancreatic β-cell function. The findings of this study improve our understanding of the role of PEDF as an adipokine in the development of T2DM and offer novel insights and targets for the prevention and treatment of diabetes.

Methods

Animal studies

All animal experiment procedures were carried out in an environment without specific pathogens (Specific pathogen free, SPF) with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (approval ID: SYXK 2019-0209). All of the animal experiment procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Sun Yat-Sen University. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Homozygous mice and their littermate wild-type (WT) controls were generated and genotyped from heterozygous breeders. Male C57BL/6J mice (eight-weeks-old) were obtained from the Center of Experimental Animals, Sun Yat-sen University. A PEDF-KO mouse strain was provided as a generous gift by Dr. Jianxing Ma (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center)36,37. A PEDF-ROSA26 Knock-in (PEDF-TG) mouse strain was purchased from Cyagen Biosciences (Jiangsu, China). Validation results for both pancreatic islet and peripheral PEDF are provided in the Supplementary Figs. (Fig. S6A–C).

In vivo, we investigated the impact of elevated PEDF on the progression T2DM. PEDF knockout mice with high-fat diet (HFD), compared to WT with chow-diet (CD) and WT with HFD, we aimed to determine whether PEDF plays a critical role in this process. At 8weeks of age, the mice were categorized into 3 groups and fed for 12weeks as follows: WT with chow-diet (WT-CD, 13.5% kcal fat, n = 8), WT-KO with HFD (WT-KO-HFD, 60% kcal fat; D12492, ReadyDietech, n = 7) and PEDF-KO with HFD (PEDF-KO-HFD, n = 7). For PEDF neutralizing antibodies (PEDF Ab) therapy, the C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with the PEDF Ab (GenScript China) 0.4 mg/kg/day, for 15 days, and the control group was injected with the same concentration of nonspecific IgG (n = 6-8 per group/time point). As PEDF-TG mouse strain, experimental groups (WT-TG and PEDF-TG mice) were examined at three time points: 6, 9, and 12 months (n = 6-8 per group/time point). All mice experimented in this study were male.

Isolation of primary mouse islets and in vitro glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS)

Pancreatic islets were isolated from adult C57BL/6 mice using a collagenase-based digestion protocol. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the common bile duct was cannulated for retrograde injection of 1.5-2 mL ice-cold Collagenase P solution (1 mg/mL in HBSS). The distended pancreas was excised and digested at 37 °C for 15-20 min with gentle agitation. The digested tissue was washed three times with HBSS containing 0.1% BSA and centrifuged (800×g, 2 min, 4 °C).

To purify islets, the pellet was resuspended and filtered using a 70 μm strainer, then washed three times with HBSS, after which the strainer was inverted and rinsed into a new 60 mm dish using RPMI-1640 medium and hand-picked under a stereomicroscope based on morphology (diameter: 50-300 μm), a minimum of 20 islets were isolated per mouse. Islets were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO₂ for subsequent experiments.

For in vitro GSIS, after maintained overnight, the isolated mice primary islets were washed three times with KRBH buffer without glucose, then transferred to 1 mL 2.8 mM glucose KRBH buffer for incubation for 30 minutes and 100 μL of supernatant was taken. The primary islets were then transferred to 1 mL 16.7 mM KRBH buffer for incubation for 30 minutes. 100 μL of supernatant was taken at 15 and 30 minutes. The insulin concentration at the corresponding time point was detected by an ELISA assay kit and the average release rate was calculated as an assessment of insulin release capacity. The collected supernatant was measured using an ELISA assay kit to measure insulin content.

Oral glucose test and in vivo GSIS

After overnight fasting, experimental mice were administered a glucose solution (2 g/kg) by oral gavage, which was prepared at a concentration of 0.2 g/mL. Blood glucose levels in the mice were then measured using blood glucose test strips and a glucose meter (Johnson & Johnson, USA) at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after gavage by tail vein blood samples.

In vivo GSIS test: during the OGTT, blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital plexus at 15 minutes and 30 minutes for insulin measurement using the ELISA assay kit. The insulinogenic index (IGI) was calculated by following formula:

Cell culture and treatment

Beta-TC-6 cells were purchased from Cell Bank/Stem Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and RIN-m5f cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. recombinant His-PEDF protein (rPEDF) were obtained as previously describe17.

Plasmids and small-interfering RNA transfection

The over expression plasmids and small interfering RNAs were synthesized in RiboBio (Guangzhou, China), and more than three sets of sequences were designed. The interference efficiency was validated, and the knockdown effect was confirmed at the mRNA levels. The transfection reagents (Lipofectamine 3000, #L3000015, Invitrogen) were used for transfecting the plasmid/siRNA. DNA premix was prepared by diluting Lipofectamine 3000 reagent with Opti-MEM medium (#31985-070, Gibco) without extra serum, plasmid was diluted with Opti-MEM medium to prepare DNA premix, then P3000 reagent was added (siRNA was diluted without P3000), and diluted plasmid/siRNA (1:1 ratio) was added to each tube of diluted Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. The mixture was gently mixed and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The mixture was added drop by drop to the cell culture wells, gently mixed, and incubated in a cell incubator. The validation of siRNA knockdown efficiency is provided in the Supplementary Figs. (Fig. S6D).

Purification of the recombinant His-PEDF protein

The recombinant His-PEDF (rPEDF) protein was expressed using the pcDNA3.1 plasmid in DH5α Escherichia coli and subsequently purified. Protein purification was performed using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, with target proteins eluted by imidazole gradient. The eluted fraction was concentrated and buffer-exchanged, yielding >98% purity as quantified by BCA assay.

Insulin ELISA assay

Mouse serum and cell supernatant were collected for insulin detection using the Mouse Insulin ELISA Kit (Mercodia, USA). Samples and standards were diluted according to the instructions and incubated at room temperature with Enzyme Conjugate for 2 hours. After discarding the liquid, the wells were washed 6 times with Wash buffer. Substrate TMB was then added and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. Finally, a Stop Solution was added, and the absorbance was measured at OD450 nm to calculate the insulin content in the samples.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells with an RNA Extraction Kit (EZB-RN001-plus, EZBioscience). First, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, mRNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with 4×Reverse Transcription Master Mix (A0010GQ, EZBioscience). Next, mRNA expression was quantified using Color SYBR Green qPCR Mix (A0012, EZBioscience). Finally, mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. The following specific primers can be found in Table S1.

Western Blot analysis

Tissues and cells were lysed in total protein lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The supernatant was quantified by a BCA kit (KeyGen BioTECH, China). The sample was denatured at 95 °C for 5 min before loaded. Equal amounts of protein were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked in a 5% milk solution for 1 h, incubated with the primary antibodies overnight, and a secondary antibody for 4 h at 4 °C. Chemiluminescence was developed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate. The antibodies used can be found in Table S2.

Nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were extracted using a commercial extraction kit (#P0028, Beyotime Biotechnology). Briefly, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS in culture dishes and incubated on ice for 15 min, then scraped off using a cell scraper. The cell pellet was collected by centrifugation.

For cytoplasmic protein extraction, the cell pellet was resuspended in Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Reagent A containing PMSF, vortexed for 5 sec, and incubated on ice for 10-15 min. Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Reagent B was then added, followed by vortexing for 5 sec. The supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was collected after centrifugation. For nuclear protein extraction, the remaining pellet was resuspended in Nuclear Protein Extraction Reagent containing PMSF. The suspension was vortexed and returned to ice, with repeated vortexing every 1-2 min for a total of 20 cycles. The supernatant (nuclear fraction) was collected after centrifugation.

Immunofluorescence staining and immunohistochemistry

Mouse pancreas tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis and then frozen and sectioned. Four-micrometer thick sections were washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS at 37 °C for 1 h. The tissues were incubated with the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, washed three times with PBS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (SA00006-4, Proteintech) at 37 °C for 1 h. After additional PBS washes, the tissues were counterstained with the nuclear stain 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (C1006, Beyotime) at room temperature for 10 min. A fluorescence microscope (BX63, Olympus, Japan) was used to acquire immunofluorescence images. The antibodies used can be found in Table S2.

Paraffin section was deparaffinized with xylene and ethanol and hydrated in gradient alcohol. Antigens were retrieved by heating in 10 mM citric acid (pH 6.0). 3% H2O2 was added to the tissue section to block endogenous peroxidase. Goat serum blocking working solution (#ZLI-9056, ZSGB Bio) was used to block the tissue sections. Then, the sections were incubated with relevant primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Finally, the sections were incubated with diaminobenzidine (DAB) to develop color, and the samples were counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were acquired using KF-FL-400 imaging system (KonFoong Bioinfo Tech). The antibodies used can be found in Table S2.

Intracellular calcium ion fluorescent staining

Cells were seeded in a 12-well plate at a density of 80,000 cells per well. After experimental treatments, the supernatant was removed, and the culture medium was discarded. The cells were washed three times with HBSS. Then, Fluo 4-AM (40704ES, Yeasen, 1 μM) was added, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator for 30 minutes. After removing the Fluo 4-AM, the cells were washed three times with HBSS solution and then covered with HBSS solution. Subsequently, the cells were placed back into the 37 °C incubator for 30 minutes to ensure complete de-esterification of the AM dye within the cells. The fluorescence signal was detected at an emission wavelength of 510 nm using a Leica DM6B fluorescence microscope, with fluorescence intensity analyzed by Image-Pro Plus software.

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis

Download the GSE50398 dataset and select differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2FC | ≥1, p < 0.05)38. Use clusterProfiler to map these genes to GO terms (Biological Process, Molecular Function, Cellular Component). Enrichment is calculated via hypergeometric/Fisher’s exact test using all detected genes as the background, with multiple testing correction (FDR < 0.05). Significant terms are ranked by adjusted p-value and visualized as dot/bar plots.

Statistics and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Prism Software, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis and graphing. All values are expressed as the mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). For comparisons between two independent groups, an unpaired Student’s t-test was applied. When comparing three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Two-way ANOVA combined with Tukey’s or Bonferroni’s multiple comparison method was used to perform pairwise comparisons among multiple groups with two factors. Data was presented as mean ± Standard Error of the Mean (SEM). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All experiments were performed in at least three independent replicates to ensure the reproducibility of the findings. The results were consistent across these replicates, including qualitative observations that did not undergo statistical analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The main data and materials supporting these findings appear in the main manuscript. The Supplementary Figs., tables, and uncropped blots can be found in a single PDF named “Supplementary information”. The source data behind the graphs in the main manuscript can be found in the “Supplementary Data file”. Additional information is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Federation, I. D. IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edn (International Diabetes Federation, 2021).

Rao Kondapally Seshasai, S. et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 829–841 (2011).

Yang, M., Wei, Y., Liu, J., Wang, Y. & Wang, G. Contributions of hepatic insulin resistance and islet β-cell dysfunction to the blood glucose spectrum in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 49, 883–892 (2025).

Seino, S., Shibasaki, T. & Minami, K. Dynamics of insulin secretion and the clinical implications for obesity and diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 2118–2125 (2011).

Kalwat, M. A. & Cobb, M. H. Mechanisms of the amplifying pathway of insulin secretion in the β cell. Pharmacol. Ther. 179, 17–30 (2017).

Merovci, A. et al. Effect of mild physiologic hyperglycemia on insulin secretion, insulin clearance, and insulin sensitivity in healthy glucose-tolerant subjects. Diabetes 70, 204–213 (2021).

Henquin, J. C. Regulation of insulin secretion: a matter of phase control and amplitude modulation. Diabetologia 52, 739–751 (2009).

Gandasi, N. R. et al. Ca2+ channel clustering with insulin-containing granules is disturbed in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 127, 2353–2364 (2017).

Röder, P. V., Wu, B., Liu, Y. & Han, W. Pancreatic regulation of glucose homeostasis. Exp. Mol. Med. 48, e219 (2016).

Campbell, J. E. & Newgard, C. B. Mechanisms controlling pancreatic islet cell function in insulin secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 142–158 (2021).

Kahn, S. E., Hull, R. L. & Utzschneider, K. M. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 444, 840–846 (2006).

Hudish, L. I., Reusch, J. E. & Sussel, L. Β cell dysfunction during progression of metabolic syndrome to type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 129, 4001–4008 (2019).

Tombran-Tink, J. & Barnstable, C. J. PEDF: a multifaceted neurotrophic factor. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 628–636 (2003).

Lyu, J. et al. The comparison of pathogenic role and mechanism of kallistatin and PEDF in tumors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1880, 189273 (2025).

Qi, W. et al. High levels of pigment epithelium-derived factor in diabetes impair wound healing through suppression of wnt signaling. Diabetes 64, 1407–1419 (2015).

Hui, E. et al. Elevated circulating pigment epithelium-derived factor predicts the progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, E2169–E2177 (2014).

Che, D. et al. Elevated pigment epithelium-derived factor induces diabetic erectile dysfunction via interruption of the akt/hsp90β/eNOS complex. Diabetologia 63, 1857–1871 (2020).

Dai, Z. et al. Dual regulation of adipose triglyceride lipase by pigment epithelium-derived factor: a novel mechanistic insight into progressive obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 377, 123–134 (2013).

Crowe, S. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor contributes to insulin resistance in obesity. Cell Metab. 10, 40–47 (2009).

Moreno-Navarrete, J. M. et al. Liver, but not adipose tissue PEDF gene expression is associated with insulin resistance. Int. J. Obes. 37, 1230–1237 (2013).

Gattu, A. K. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) suppresses IL-1β-mediated c-jun n-terminal kinase (JNK) activation to improve hepatocyte insulin signaling. Endocrinology 155, 1373–1385 (2014).

Motta, M. C. et al. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell 116, 551–563 (2004).

Kitamura, T. & Ido Kitamura, Y. Role of FoxO proteins in pancreatic beta cells. Endocr. J. 54, 507–515 (2007).

Kitamura, T. The role of FOXO1 in β-cell failure and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 9, 615–623 (2013).

Yu, J. et al. Enhanced expression of β cell ca(v)3.1 channels impairs insulin release and glucose homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 448–453 (2020).

Matsuzaki, H., Daitoku, H., Hatta, M., Tanaka, K. & Fukamizu, A. Insulin-induced phosphorylation of FKHR (foxo1) targets to proteasomal degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11285–11290 (2003).

He, T. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor regulates microvascular permeability through adipose triglyceride lipase in sepsis. Clin. Sci. 129, 49–61 (2015).

Tryggestad, J. B., Wang, J. J., Zhang, S. X., Thompson, D. M. & Short, K. R. Elevated plasma pigment epithelium-derived factor in children with type 2 diabetes mellitus is attributable to obesity. Pediatr. Diabetes 16, 600–605 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) regulates metabolism and insulin secretion from a clonal rat pancreatic beta cell line BRIN-BD11 and mouse islets. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 426, 50–60 (2016).

Talchai, C., Xuan, S., Lin, H. V., Sussel, L. & Accili, D. Pancreatic β cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic β cell failure. Cell 150, 1223–1234 (2012).

Xing, Y. et al. The regulation of FOXO1 and its role in disease progression. Life Sci. 193, 124–131 (2018).

Hong, H. et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) inhibits breast cancer metastasis by down-regulating fibronectin. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 148, 61–72 (2014).

Carnagarin, R., Dharmarajan, A. M. & Dass, C. R. PEDF attenuates insulin-dependent molecular pathways of glucose homeostasis in skeletal myocytes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 422, 115–124 (2016).

Wente, W. et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 improves pancreatic beta-cell function and survival by activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and akt signaling pathways. Diabetes 55, 2470–2478 (2006).

Krishnamurthy, M. et al. Integrin {alpha}3, but not {beta}1, regulates islet cell survival and function via PI3k/akt signaling pathways. Endocrinology 152, 424–435 (2011).

Huang, Q., Wang, S., Sorenson, C. M. & Sheibani, N. PEDF-deficient mice exhibit an enhanced rate of retinal vascular expansion and are more sensitive to hyperoxia-mediated vessel obliteration. Exp. Eye Res. 87, 226–241 (2008).

Park, K. et al. Identification of a novel inhibitor of the canonical wnt pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 3038–3051 (2011).

Fadista, J. et al. Global genomic and transcriptomic analysis of human pancreatic islets reveals novel genes influencing glucose metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13924–13929 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhen Zhao and Yandan Tan: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft; Jie Fang: methodology and investigation; Gan Xia: methodology, investigation, and writing—review & editing; Junchen Li: methodology, writing—review & editing; Qilong Tang: investigation; Wanting Xie: investigation; Tianxiao Gao: methodology & funding acquisition; Zhenzhen Fang: investigation and visualization; Ti Zhou: methodology and project administration; Xia Yang: methodology, funding acquisition, data curation; Guoquan Gao: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing—review & editing; Weiwei Qi: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing—review & editing. All authors have approved the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Kohjiro Ueki and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Christina Karlsson Rosenthal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Z., Tan, Y., Fang, J. et al. Elevated PEDF promotes the occurrence of diabetes mellitus via suppressing GSIS by downregulating the SNARE complex. Commun Biol 8, 1664 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09061-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09061-0