Abstract

Microbiologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) is an ecologically vital process where the metabolic activity of microorganisms causes the precipitation of calcium carbonate. In cyanobacteria, MICP is thought to occur primarily due to photosynthesis. During this process, cyanobacteria consume carbon dioxide, raising the local pH, which leads to conditions favorable to calcium carbonate precipitation. However, how individual cells contribute to MICP is poorly understood. Here, we use quantitative microscopy to obtain direct evidence of MICP caused by the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 (hereafter Anabaena) in nitrogen fixing conditions. Anabaena cells differentiate into photosynthetic vegetative cells and nitrogen-fixing heterocysts. Our results show that MICP occurs due to two distinct interactions: Firstly, mechanical stress on vegetative cells can cause leakage and/or lysis, releasing sequestered bicarbonate into the environment, resulting in the formation of new crystals. Secondly, close contact between a heterocyst and a calcite crystal seed appears to cause rapid crystal growth. To our knowledge, the latter interaction has not been reported previously. By providing greater insight into MICP caused by Anabaena, these results increase our understanding of the interplay between cyanobacteria and calcium carbonate precipitation, which plays a role in oceanic buffering and mineral formation around the globe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organisms across all kingdoms of life have been shown to influence minerals, such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3), as part of their growth. In eukaryotes, organisms such as shellfish utilize calcium carbonate present in the aquatic environment to form vital structures1,2. Microorganisms, such as fungi, archaea, and bacteria, have been shown to cause the precipitation of calcium carbonate through different mechanisms, collectively known as microbiologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP)1. Bacteria in particular have been shown to cause MICP through a range of metabolic processes, including urea hydrolysis3, denitrification4, methane oxidation5, sulfate reduction6, iron reduction7, degradation of calcium oxalate8, degradation of amino acids9, and photosynthesis10.

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic microbes found in many environments, including freshwater, marine, and terrestrial regions, and are thought to play an outsized role in CaCO3 precipitation. Geologically, these bacteria appear to have been principally responsible for the production of carbonate rocks, such as stromatolites, which are massive structures formed by layers of calcium carbonate precipitating over cyanobacterial mats11,12.

In recent years, cyanobacteria-induced MICP has received attention as a potential tool to address many engineering and environmental issues13, for instance to stabilize soil14 or as an eco-friendly alternative to traditional cement15,16. Since cyanobacteria can derive energy from sunlight, as well as absorb and store CO2 through MICP and other biological processes, they could also be useful as living building materials to sequester carbon17. These engineering applications rely on the formation of CaCO3 crystals to both solidify sediment and to provide compressive strength. However, MICP mechanisms in cyanobacteria are still poorly understood.

In the ocean and other aquatic environments, cyanobacteria have been observed to influence the precipitation of calcium carbonate during blooms and mass lysis events18,19. Different theories have been proposed to explain the various processes that could contribute to cyanobacterial MICP. For example, during photosynthesis, cyanobacterial cells uptake carbon dioxide and bicarbonate through passive diffusion or through a symporter20,21 The process results in a consumption of protons, which can be replenished by uptake through the cell membrane by various proton transporter proteins. This cyanobacterial metabolic alkalinization of the environment has been previously studied in regard to the dissolution of alternative minerals and is known to play a role in geobiological systems22. In the case of MICP, the consumption of protons increases the speciation of bicarbonate into carbonate ions, leading to the precipitation of calcium carbonate, as described by the equation19,20,21: \({{Ca}}^{2+}+{{HCO}}_{3}^{-}\to {{CaCO}}_{3}+{{{H}}}^{+}\).

Another popular theory is that cyanobacteria can cause CaCO3 precipitation when the cells lyse, for instance, through viral infection19,23. Cyanobacteria sequester carbon in internal organelles called carboxysomes, primarily in the form of bicarbonate, through their carbon concentrating mechanisms to drive the enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) toward reactions which are favorable for carbon fixation. When cells lyse, this stored inorganic carbon is released, and in combination with other metabolic processes which influence MICP, this leads to a microenvironment which is favorable to calcium carbonate precipitation19.

Other studies have shown contradicting evidence that calcium carbonate precipitation occurs even in the absence or inhibition of photosynthesis24 and theorize instead that adsorption of Ca2+ ions by cell-surface proteins are responsible for crystal nucleation25,26,27. Additionally, some species of cyanobacteria have been observed to induce calcium carbonate nucleation and growth intracellularly, although it is currently unclear how the mechanisms which drive intracellular and extracellular calcium carbonate precipitation are related28.

Within the diversity of proposed cyanobacteria-mediated MICP pathways, the exact mechanisms remain unclear, and it is likely that different models play a role depending on environmental conditions and the specific organism. To shed light on this matter, we utilize time-lapse and multispectral microscopy to film the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 (hereafter Anabaena). Anabaena filaments are typically composed of two main cell types: vegetative cells, which carry out photosynthesis, and heterocysts, which fix nitrogen. By using time-lapse microscopy, we observe unique MICP caused separately by vegetative cells and heterocysts. Compared to traditional bulk culture or environmental assays, time-lapse microscopy allows single cells and crystals to be tracked, thereby providing greater insight into the roles of individual cells in MICP.

Results

Time-lapse fluorescence microscopy enables individual cells to be tracked

To demonstrate the feasibility of our approach, Anabaena was first grown in BG11 media without supplemental nitrogen (denoted BG11-N) and filmed under typical laboratory culturing conditions. Cells were grown under a soft agar pad, which constrains cell growth to a 2-dimensional plane. Figure 1a–c and Supplementary Movie S1 shows representative frames of an Anabaena filament. Brightfield and chlorophyll fluorescence images were recorded (see “Methods”). As the filament grows, some cells differentiate into heterocysts (indicated by carets), which can be identified both by their size and the loss of chlorophyll fluorescence over time. In this initial movie, no MICP was observed.

a–c Representative frames showing Anabaena growing on the microscope in BG-11 media without supplemental nitrogen (BG11-N). Images were collected in the brightfield and chlorophyll fluorescence channels. A merged image is also shown (chlorophyll fluorescence shown in red). The carets indicate heterocysts, which are identified both by their increased size and the loss of chlorophyll fluorescence. The magenta caret indicates a cell in the early stages of differentiation, and the yellow caret indicates a previously differentiated heterocyst. Scale bars are 10 µm. d–g Representative frames showing cells growing in BG11-N-Buffer media supplemented with calcium chloride and bicarbonate (BG11-N-Buffer + Ca). Initial seed crystals were observed (indicated by carets). We observed initial crystal growth (seen in frame e), likely due to temperature change as the sample was placed in the growth chamber. Some crystals (yellow caret) showed increased growth due to interaction with the cells. Scale bars are 20 µm. h, i Crystal growth was tracked over time (Full timelapse shown in Supplementary Movie S3). Scale bar is 50 µm. h shows the merged frame after 50.5 h and i shows the mask labeling the crystals. j Crystal area over time. The zoomed-in region shown in (d–g) is indicated in magenta.

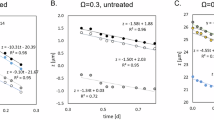

To observe calcium carbonate crystal growth, we then grew and filmed cells in separate experiments using BG11-N medium without buffer, supplemented with 25 mM of calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate (denoted BG11-N-Buffer + Ca). Frames from a representative movie (Supplementary Movie S2) are shown in Fig. 1d–g. We note that the initial concentration of calcium chloride and sodium bicarbonate caused small seed crystals to form at the start of the movie. We then filmed the cells over time and utilized computational software to track individual crystal growth, as shown in Fig. 1h–j.

As shown in Fig. 1j, we found that all initial seed crystals grew slightly in the first 2 h of the movie, likely due to the temperature change when the room temperature pad was placed in the 37 °C growth chamber. Similar growth was observed in experimental replicates. However, after this initial growth, crystal sizes stayed constant for approximately 20 h. Since Anabaena cells continued to grow during this time, this suggests that at these time scales, photosynthesis alone is not sufficient to cause crystal growth. However, some crystals showed growth upon interaction with cyanobacterial cells, as will be shown in the following sections.

As a control, we filmed cells with the same BG11-N-Buffer + Ca medium but without light, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Under those conditions, we found the same initial appearance of seed crystals with no further crystal growth during the remaining 120 h of imaging. This indicates that while the initial concentration of calcium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate in the growth medium does cause seed crystal formation, the solute concentrations on their own were insufficient to cause further crystal growth without cell activity.

Cyanobacterial cell lysis or leakage results in crystal growth

From our movies, we identified two cellular interactions which lead to MICP. First, cyanobacteria cells can lyse if mechanically trapped against a hard object. Figure 2a and Supplementary Movie S4 shows an instance in which a vegetative cell appears to be trapped within or above/below a seed crystal. The cell continues to grow, eventually dividing ~16 h into the movie. One of the daughter cells then appears to lyse, identified by a sudden loss of chlorophyll fluorescence, at ~19 h, while the remaining daughter cell lyses around 30 h, likely due to mechanical confinement. A new crystal appears to form near the site of the cell, growing quickly and engulfing the original seed crystal. Shortly before cell lysis and crystal growth, an increase in chlorophyll fluorescence is observed, which is consistent with our previous observations of the effect of mechanical confinement on individual cells29.

a Time-lapse images showing crystal growth as a result of Anabaena cell lysis within a crystal. Individual cells which were identified within the crystal are shown in blue outline. The yellow outline indicates the last frame the cell was observed before lysis. b The average chlorophyll intensity of the two cells tracked and the corresponding growth of crystal area. Dotted lines indicate the time when the individual cells lysed. c Time-lapse images showing nucleation and growth of a crystal at a sharp bend of a filament. The crystal growth appeared to be caused by cellular leakage due to mechanical stress at the bend. d, e Representative frames and plot showing that crystal growth does not occur due to proximity or contact with a vegetative cell. f Representative frames showing growth of a crystal after contact with a heterocyst (indicated by a caret). g Plot showing crystal area over time. Dotted line indicates the time of heterocyst contact at 37 h. All plots show the brightfield image in grayscale and chlorophyll fluorescence in red. All scale bars are 20 μm. h Model showing hypothesized mechanism behind vegetative cell leakage or lysis-based calcite precipitation. i Model showing hypothesized mechanism behind heterocyst contact-mediated calcite growth.

In a second instance, shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Movie S5, a filament is stressed at a bend. A new crystal nucleates at the bend and grows extracellularly at the junction. Individual Anabaena cells within a filament share a continuous outer membrane30,31. Therefore, it is likely that the mechanical stress at the bending site allowed cell material to leak out of the cell.

These CaCO3 precipitation events are likely caused by mechanical confinement or stress to cells, resulting in the leakage or entire release of their contents into the surrounding media. Since cyanobacterial cells sequester carbon as carbonate ions, the release of these ions, along with other cellular metabolites, is likely the cause of crystal growth. We note that both these events appear to occur extracellularly, and we did not observe intracellular MICP.

Heterocyst contact can result in calcium carbonate crystal growth

We also observed crystal growth when a seed crystal makes physical contact with a heterocyst cell. A representative example is shown in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Movie S6. Here, a vegetative cell differentiates into a heterocyst, which then physically contacts a seed crystal, causing rapid growth within 5 h of the initial contact. To our knowledge, this observation of heterocyst-mediated MICP has not been previously reported.

Interestingly, we found that this form of MICP only occurred through interactions with heterocysts and were not caused by proximity to vegetative cells. Figure 2d and Supplementary Movie S7 shows examples of vegetative cells growing close to or against a seed crystal. The crystal does not increase in size despite ~26 h of cellular growth.

To better characterize these events, we analyzed our datasets by visually identifying cases where a heterocyst cell contacts a seed crystal. In two out of the seven datasets collected, we clearly observed at least 16 instances when at least one heterocyst contacted a seed crystal. Only instances where we could clearly observe both heterocyst and seed crystal were included in this count. Cases where there was ambiguity, for instance, if there were overlapping cells, or if the seed crystals or cells were out of the plane of focus, were ignored. We did not observe heterocyst contact in three replicate movies. However, we note that in our current experiments, these events occurred entirely by chance. More controlled experiments could be carried out in the future, for instance, by using optical tweezers to manipulate the crystals or heterocysts into contact.

While the exact mechanism is currently unknown, whether heterocyst contact causes a crystal to grow appears to depend on when heterocyst contact was made. From all identified events, we found that nine did not show crystal growth (as can be seen in Supplementary Movie S2), while the remainder did. However, we note that the contact events which did not result in crystal growth occurred in the early portion of the videos, between 8 and 51 h. The remaining examples, occurring 37 h or later, resulted in crystal growth.

Biotic calcium carbonate crystals are calcite

To further characterize the crystals, we grew and filmed cells using the same brightfield microscope for 117 h. After this time, we transferred and imaged the same sample using a Raman-capable microscope. A zoomed in region from the final fame of the full movie (Supplementary Movie S8) is shown in Fig. 3a. An area Raman scan was then performed, as shown in Fig. 3b. The fluorescence image was then manually registered to the Raman scan to identify the crystals tracked in the movie. The images are shown overlaid in Fig. 3c to show overlap of crystal location from Raman microscope data with the end of the live growth experiment.

a–c Area Raman scan with calcite intensity in gray and chlorophyl fluorescence from final frame of live growth experiment in red and an overlay of the two channels. Scale bar is 20 μm. d Raman scan of this crystal showing calcite and carotenoid presence. e Image of crystals in final frame of time lapse experiment, and f, g two corresponding Raman scans of seed crystals formed distantly from cellular growth, showing calcite and vaterite with no carotenoid presence. All scale bars are 20 μm.

Based on the Raman spectra, we found that the Anabaena-mediated crystals consisted primarily of calcite and contained carotenoids (Fig. 3d), indicating the presence of cells or cellular debris trapped within the expanding crystal32. In comparison, seed crystals from a different region without nearby cells were much smaller and appeared to be composed of either calcite or vaterite (Fig. 3d, f, g)33,34. Additional Raman scans of crystals with and without nearby cells are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

We also analyzed crystals in regions where Anabaena were present, but there was no cell growth, as shown in Fig. 3e and Supplementary Movie S9. In these regions, no crystal growth was observed beyond the initial seed crystal formation as previously mentioned. The Raman signature for these crystals also appeared to be a mix of vaterite and calcite.

The formation of vaterite and calcite was previously reported as an indication of CaCO3 formation within low supersaturation conditions in abiotic environments35. Which polymorph of CaCO3 forms likely follows Ostwald’s Rule, which states that the less stable polymorph crystallizes first. Thus, in low supersaturation conditions, calcium carbonate naturally forms short-lived amorphous crystals, which then rapidly transform into vaterite and finally into the stable calcite isoforms. In contrast, crystals formed through MICP appear to be primarily calcite, as previously reported36.

Discussion

A recent study of calcium precipitation by a different strain of Anabaena (A. variabilis) concluded that MICP could be caused by two distinct mechanisms: (1) A. variabilis could produce a precipitating alkaline environment within 24 h due photosynthetic activity, and (2) A. variabilis showed high capacity for adsorbing calcium ions, which could turn the cells into a nucleation agent for crystal formation37. While it is probable that these mechanisms of MICP play some role in our system, neither of these mechanisms fully explain our observations, as discussed below. While it is additionally possible that the differences are unique to the species of Anabaena studied here, we believe that our results provide a different insight by showing how individual cells cause MICP.

By using time-lapse microscopy, we were able to monitor the size of individual crystals. In our experiments, we did not measure global crystal growth, which likely indicates that at the timescale and cell densities of our experiments, photosynthetic processes did not sufficiently change the medium to cause MICP. We note that our observations do not discount these cyanobacteria from being capable of driving MICP by photosynthesis. However, our samples were grown at a relatively low density compared to typical bulk cultures (cells imaged on the microscope were diluted by 1000x from liquid culture in order to obtain a single layer of cells). This lower cell density likely reduces the overall impact of photosynthesis on media pH within the time scale of this experiment.

Additionally, we did not observe crystal nucleation outside of cell lysis, or, more uniquely, by leakage of cellular contents at the junction of mechanically stressed Anabaena cells. This suggests that adsorption of ions on the cell surface was not the cause of the new crystals in our experiments. This stress appears to occur naturally due to bending of the filament and is likely influenced by both cell growth and surface friction of the growth medium29. Careful modulation of these conditions could allow MICP to be induced in a controllable manner and should be a target of future studies.

Finally, we found that MICP was induced by proximity or contact of a heterocyst cell with an existing crystal seed. To our knowledge, this phenomenon has not previously been reported. Interestingly, MICP did not appear to be caused by contact with vegetative cells. The dependence of MICP on cell type suggests that ion adsorption on the cell surface might not play a key role here, or that calcium might be preferentially bound to heterocysts. However, no preferential calcium carbonate nucleation was observed at the surface of heterocysts, which suggests against this as the primary mechanism of heterocyst contact-mediated MICP.

Here, we propose an alternative hypothesis that MICP occurs due to the nitrogen-fixing activity of the heterocysts. These cells rapidly catalyze the fixation of nitrogen gas into ammonia38, described by the reaction \({{{N}}}_{2}+16{ATP}+8{{{e}}}^{-}+8{{{H}}}^{+}\rightleftharpoons 2{{NH}}_{3}+{{{H}}}_{2}+16{ADP}+16{{{P}}}_{i}\). The resulting ammonia is then converted into ammonium ions, \(2{{NH}}_{3}+2{{{H}}}^{+}\rightleftharpoons 2{{NH}}_{4}^{{{{\boldsymbol{+}}}}}\). Thus, ten protons are consumed per molecule of nitrogen fixed into two molecules of ammonium. It has been previously observed that heterocysts maintain an internal pH gradient formed by cytochrome b6f to drive ATP synthesis39,40. This would suggest that heterocysts must therefore maintain a relatively stable internal pH level, requiring a net influx of protons. This influx is likely driven by the number of known proton transport proteins which are found within Anabaena, many of which are known to play a role in maintaining internal cellular pH, however, the specific role within heterocysts has not been fully investigated. We hypothesize that this results in proton consumption at the heterocyst cell membrane, which would cause local proton depletion at the cell surface. This in turn could increase the pH, leading to increased precipitation. Further work is required to determine whether this or some other mechanism is responsible for this phenomenon.

Our results require cells to be grown in a medium which at least initially causes precipitation of crystal seeds. As was previously shown, the presence of these seeds could affect the starting pH of the solution36. We note that while additional calcium and bicarbonate were added to the growth media before the start of the experiment, the resulting concentration is not entirely implausible and could be found in nature. Existing reports place the average calcium ion concentration in seawater at ~10.28 mM41, with significant variance depending on the specific location. With the additional calcium chloride, we estimate that our growth media contains ~26.24 mM, which is roughly a factor of 2.

In conclusion, our time-lapse microscopy data provides new insight into the mechanism of MICP by individual cyanobacteria cells. While further work is needed to confirm the chemical reactions causing crystal growth, we found that physical interactions, specifically cellular and filament stress and heterocyst contact, can trigger MICP. These results suggest that individual cell types within a differentiating cyanobacterial species should be considered separately, not as a single population, which could have wider implications for understanding how these cells affect their local microenvironment.

Methods

Strain and culturing

Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 was grown at 37 °C in BG11 media. All preculturing occurring in 25 mL liquid cultures with 100 rpm orbital shaking in 125 ml baffled flasks with foam stoppers. Liquid and agar cultures were grown in an AL-41 L4 Environmental Chamber (Percival Scientific, Perry, IA) at 37 °C under continuous illumination at 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 from cool white fluorescent lamps in air (0.04% CO2).

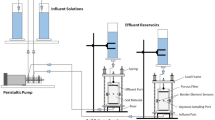

Time-lapse microscopy

All long-term observation images and videos were obtained using a Nikon TiE inverted wide-field microscope with Perfect Focus System, controlled using NIS Elements AR software (version 5.11.00; 64-bits) with Jobs package. Images were acquired using a digital sCMOS camera (Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash4.0 V2+) with a 20× air objective (Nikon CFI Plan Apochromat Lambda D). Temperature during cell growth in all images was maintained at 37 °C using an Okolab cage Incubator (Okolab). Growth light and trans-illuminating imaging light were supplied from a light-emitting diode (LED) light source (LIDA Light Engine, Lumencor, Beaverton, OR). Epifluorescence imaging light was supplied from a custom-filtered LED light source (Spectra X Light Engine, Lumencor, Beaverton, OR) and delivery was controlled using a synchronized hardware-triggered shutter. Cells for imaging were grown in liquid culture to ~1.00 OD at 730 nm. Precultures were grown in BG11 media. 25 μL of 1 M CaCl2 was added to the sample side of a 1% agarose imaging pad (1 mL) BG11-N-Buffer (BG11 media without fixed nitrogen or buffer, pH 7.8) and allowed to fully dry/dissolve (for non-MICP condition movies, the imaging pad was made with BG11-N (BG11 media without fixed nitrogen) media and no CaCl2 or sodium bicarbonate were added). Three to five 2 μL drops of cells were added to the imaging side of the pad and allowed to dry. The pad was flipped into the imaging dish, and an additional 25 μL of 1 M sodium bicarbonate was added to the top of the pad. The imaging dish (Ibidi μ-dish 35 mm glass) was immediately sealed with parafilm, and placed into the microscope environmental chamber at 37 °C. Cells were grown under 37 °C and 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 640 nm light; this light was on at all times except during fluorescence imaging.

All time lapse imaging performed on Nikon Plan Apo (wavelength) 20× Brightfield illuminated by Lida at ExW: 450 nm, power 2.0, ExW: 550 nm, power 2.0, ExW: 640 nm, power 2.0. Cy5 excited at 640 nm, power 5.0. When present, CFP excited at 440 nm, power 50.0. RFP excited at 555 nm, power 10.0. Frames were captured either every 20 or 30 min. A total of seven experimental replicates were acquired over the course of two years (see Supplementary Table S1).

Correlated live-cell and Raman microscopy

To obtain the correlated light and Raman microscopy images shown in Fig. 3, cells were initially filmed using a light microscope, as described above. A large image was taken at the end of the time course. The sample was then transferred to the Raman microscope (Horiba LabRAM HR Evolution confocal Raman spectrometer with 532/785 nm lasers). Scans of the Raman spectrum across the sample were with either a 100× or 50× objective. Raman scans were performed using a 532 nm laser and scanning from 84 to 1786 cm−1. All Raman scans were performed the same day as live growth microscopy and samples were stored in the dark during transfer. Additional Raman scans shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The resulting Raman scan was then manually correlated with the light microscopy image to identify the mineral identity of each crystal. Raman scans were processed with the Horiba Labspec 6 (Version 6.7.1.10 64-bit) software using a 6° iterative polynomial fit. Raman scan was analyzed using a least squared fit using n-member regions within the spectra. The resulting Raman map was colored based on pixel scan similarity to known calcite spectra.

Image analysis

Crystals and cells were segmented using image processing functions in MATLAB to create an initial binary masks. The binary masks were then manually corrected using Fiji/ImageJ (version 1.53t) to obtain the final masks. The masks were then used with a tracking algorithm to obtain time-series data of crystal area, cell lengths, and fluorescence intensities42. All computational analysis was performed with MATLAB version R2020b (Mathworks). All MATLAB scripts, along with the cell and crystal masks are available online in the project’s GitHub repository, as described in the Code Availability statement below.

Statistics and reproducibility

A total of nine experimental movies were acquired for this work. Seven replicates were acquired under calcite-precipitating conditions, as well as one movie with no growth light, and one movie under typical laboratory growth conditions (BG-11) as controls. Experimental replicates are defined as separate time-lapse microscopy experiments, which were performed with different cell cultures on separate days (see Supplementary Table 1 for more details). Note that a single time-lapse experiment may contain more than one field-of-view. However, these were not counted as separate experimental replicates. Other statistical details, such as the number of observed occurrences of crystal growth, are listed under the corresponding section of the methods or results.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data for all graphs, including Raman spectra in the paper and Supplementary Information are provided in Supplementary Data. Manually annotated cell and crystal masks are available on Zenodo43. Raw microscopy datasets and other materials are available upon reasonable request to CMB (brininger@wisc.edu) or JWT (jian.tay@colorado.edu).

Code availability

All custom code as well as instructions to analyze the data presented in this paper is available via GitHub at https://github.com/cameronlab/anabaena-micp. Additionally, an archived version of the code, including custom toolboxes, is available via Zenodo44.

References

Schroer, L., Boon, N., De Kock, T. & Cnudde, V. The capabilities of bacteria and archaea to alter natural building stones—a review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 165, 105329 (2021).

Ismail, R. et al. Synthesis and characterization of calcium carbonate obtained from green mussel and crab shells as a biomaterials candidate. Materials 15, 5712 (2022).

Hammes, F., Boon, N., De Villiers, J., Verstraete, W. & Siciliano, S. D. Strain-specific ureolytic microbial calcium carbonate precipitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4901–4909 (2003).

Ersan, Y. C., De Belie, N. & Boon, N. Microbially induced CaCO3 precipitation through denitrification: an optimization study in minimal nutrient environment. Biochem. Eng. J. 101, 108–118 (2015).

Luff, R., Wallmann, K. & Aloisi, G. Numerical modeling of carbonate crust formation at cold vent sites: significance for fluid and methane budgets and chemosynthetic biological communities. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 221, 337–353 (2004).

Baumgartner, L. K. et al. Sulfate reducing bacteria in microbial mats: changing paradigms, new discoveries. Sediment. Geol. 185, 131–145 (2006).

DeJong, J. T., Mortensen, B. M., Martinez, B. C. & Nelson, D. C. Bio-mediated soil improvement. Ecol. Eng. 30, 197–210 (2010).

Braissant, O., Verrecchia, E. & Aragno, M. Is the contribution of bacteria to terrestrial carbon budget greatly underestimated? Naturwissenschaften 89, 366–370 (2002).

Rodriguez-Navarro, C., Rodriguez-Gallego, M., Ben Chekroun, K. & Gonzalez-Muñoz, M. T. Conservation of ornamental stone by Myxococcus xanthus-induced carbonate biomineralization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 2182–2193 (2003).

Dupraz, C. et al. Processes of carbonate precipitation in modern microbial mats. Earth Sci. Rev. 96, 141–162 (2009).

Allwood, A. C., Walter, M. R., Burch, I. W. & Kamber, B. S. 3.43 billion-year-old stromatolite reef from the Pilbara craton of Western Australia: ecosystem-scale insights to early life on Earth. Precambr. Res. 158, 198–227 (2007).

Allwood, A. C., Walter, M. R., Kamber, B. S., Marshall, C. P. & Burch, I. W. Stromatolite reef from the Early Archaean era of Australia. Nature 441, 714–718 (2006).

Seifan, M. & Berenjian, A. Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation: a widespread phenomenon in the biological world. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 4693–4708 (2019).

Wang, Z., Zhang, N., Ding, J., Lu, C. & Jin, Y. Experimental study on wind erosion resistance and strength of sands treated with microbial-induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 1–10 (2018).

De Muynck, W., De Belie, N. & Verstraete, W. Microbial carbonate precipitation in construction materials: a review. Ecol. Eng. 36, 118–136 (2010).

Dhami, N. K., Reddy, M. S. & Mukherjee, A. Bacillus megaterium mediated mineralization of calcium carbonate as biogenic surface treatment of green building materials. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 2397–2406 (2013).

Qiu, J. et al. Engineering living building materials for enhanced bacterial viability and mechanical properties. iScience 24, 102083 (2021).

Zhang, J.-Z. Cyanobacteria blooms induced precipitation of calcium carbonate and dissolution of silica in a subtropical lagoon, Florida Bay, USA. Sci. Rep. 13, 4071 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Precipitation of calcium carbonate mineral induced by viral lysis of cyanobacteria: evidence from laboratory experiments. Biogeosciences 16, 949–960 (2019).

Zhu, T. & Dittrich, M. Carbonate precipitation through microbial activities in natural environment, and their potential in biotechnology: a review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 4, 4 (2016).

Martinez, R. E., Weber, S. & Grimm, C. Effects of freshwater Synechococcus sp. cyanobacteria pH buffering on CaCO3 precipitation: implications for CO2 sequestration. Appl. Geochem. 75, 76–89 (2016).

Olsson-Francis, K., Simpson, A., Wolff-Boenisch, D. & Cockell, C. The effect of rock composition on cyanobacterial weathering of crystalline basalt and rhyolite. Geobiology 10, 434–444 (2012).

Lisle, J. T. & Robbins, L. L. Viral lysis of photosynthesizing microbes as a mechanism for calcium carbonate nucleation in seawater. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1958 (2016).

Jiang, H.-B., Cheng, H.-M., Gao, K.-S. & Qiu, B.-S. Inactivation of Ca2+/H+ exchanger in Synechocystis sp. Strain PCC 6803 promotes cyanobacterial calcification by upregulating CO2-concentrating mechanisms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4048–4055 (2013).

Dittrich, M. & Sibler, S. Calcium carbonate precipitation by cyanobacterial polysaccharides. Geol. Soc. 336, 51–63 (2010).

Liang, A., Paulo, C., Zhu, Y. & Dittrich, M. CaCO3 biomineralization on cyanobacterial surfaces: insights from experiments with three Synechococcus strains. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 111, 600–608 (2013).

Son, Y. et al. Enhanced mechanical properties of living and regenerative building materials by filamentous Leptolyngbya boryana. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 102098 (2024).

Benzerara, K. et al. Intracellular Ca-carbonate biomineralization is widespread in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10933–10938 (2014).

Moore, K. A. et al. Mechanical regulation of photosynthesis in cyanobacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 757–767 (2020).

Burnat, M., Schleiff, E. & Flores, E. Cell envelope components influencing filament length in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 196, 4026–4035 (2014).

Kumar, K., Mella-Herrera, R. A. & Golden, J. W. Cyanobacterial heterocysts. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000315 (2010).

Jehlička, J. et al. Potential and limits of Raman spectroscopy for carotenoid detection in microorganisms: implications for astrobiology. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 372, 20140199 (2014).

Gabrielli, C., Jaouhari, R., Joiret, S. & Maurin, G. In situ Raman spectroscopy applied to electrochemical scaling. Determination of the structure of vaterite. J. Raman Spectrosc. 31, 497–501 (2000).

Buzgar, N. & Apopei, A. I. The Raman study of certain carbonates. Geologie 55, 97–112 (2009).

Fu, T., Saracho, A. C. & Haigh, S. K. Microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) for soil strengthening: a comprehensive review. Biogeotechnics 1, 100002 (2023).

Zehner, J., Røyne, A. & Sikorski, P. Calcite seed-assisted microbial induced carbonate precipitation (MICP). PLoS ONE 16, e0240763 (2021).

Zúñiga-Barra, H. et al. Use of photosynthetic MICP to induce calcium carbonate precipitation: prospecting the role of the microorganism in the formation of CaCO3 crystals. Algal Res. 80, 103499 (2024).

Burris, R. H. & Roberts, G. P. Biological nitrogen fixation. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 13, 317–335 (1993).

Almon, H. & Böhme, H. Photophosphorylation in isolated heterocysts from the blue-green alga Nostoc muscorum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 679, 279–286 (1982).

Janaki, S. & Wolk, C. P. Synthesis of nitrogenase by isolated heterocysts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 696, 187–192 (1982).

He, H., Li, Y., Wang, S., Ma, Q. & Pan, Y. A high precision method for calcium determination in seawater using ion chromatography. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 231 (2020).

Tay, J. W. & Cameron, J. C. Computational and biochemical methods to measure the activity of carboxysomes and protein organelles in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 683, 81–100 (2023).

Tay, J. W. & Brininger, C. Masks for calcite precipitation by the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17298681 (2025).

Tay, J. W. & Brininger, C. Code for calcite precipitation by the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17297769 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this publication to the memory of Prof. Jeffrey Cameron, who was the principal investigator through most of this study. Jeffrey Cameron was a passionate scientist and incredible mentor, and his guidance on this and many other projects made these discoveries possible. We also thank Dr. Hamadri Pakrasi for the Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047 strain and to Eric Ellison for training and correspondence on microscope use and data treatment. This work was supported in part by the NIH Biophysics Training Grant T32 GM145437, and the Department of Energy under grants DOE DE-SC0018368 and DE-SC0020361 to J.C.C. Raman spectroscopic analyses were performed at the Raman Microspectroscopy Lab, Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder (RRID: SCR_019305).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.C., C.M.B., and E.E. conceptualized the study. J.C.C. and C.M.B. designed the experiments. C.M.B. and E.B.J. ran and acquired the fluorescence microscopy data. C.M.B. performed the Raman microscopy experiments. C.M.B. and J.W.T. analyzed the resulting imaging datasets. C.M.B., J.W.T., and J.C.C. wrote the initial manuscript. C.M.B., J.W.T., E.J.B., and E.E. revised and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.C.C. was a co-founder and held equity in Prometheus Materials Inc. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Yongjun Son and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Haichun Gao and Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brininger, C.M., Tay, J.W., Johnson, E.B. et al. Calcite precipitation by the nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. ATCC 33047. Commun Biol 8, 1728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09065-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09065-w