Abstract

Cyanobacteria, considered responsible for the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) that shaped the Earth for the evolution of complex life, are among the most morphologically diverse prokaryotic phyla. Their morphotypes range from unicellular to multicellular filaments and, additionally, many filamentous cyanobacteria exhibit cellular differentiation processes. However, mechanisms underlying the evolution of filamentous morphologies remain unknown. Here, we implement phylogenomic, Bayesian molecular clock and gene-tree-species-tree reconciliation analyses to estimate when genes encoding cell-cell joining structures—involved in multicellularity—and cellular differentiation regulators first evolved. Our results suggest that genes encoding septal proteins (namely sepJ and sepI) and proteins potentially involved in the formation of patterns of distinct cells (hetR) evolved in the Neoarchaean ~2.6-2.7 billion years ago (Ga). Later, at the start of the GOE ~2.5 Ga, genes involved in cellular differentiation (namely hetZ, patU3) and increased septal complexity (hglK) appeared. We also characterise septal structures and measure intercellular molecular transfer in non-model and early-branching filamentous strains, finding intercellular molecular exchange in phylogenetically distant filamentous cyanobacteria. Our results predict that early-branching lineages like Pseudanabaena were capable of intercellular exchange in the lead up to the GOE, despite having fewer septal pores than more-recently-evolving heterocystous strains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyanobacteria diverged from their closest non-photosynthetic relatives (the Vampirovibrionia1,2) ~ 3.3 billion years ago (Ga)3,4,5, but their photosynthetic activity did not oxygenate the global atmosphere until the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) of ~2.45 to ~2.2 Ga6,7. What caused this delay between the origin of photosynthetic cyanobacteria and the GOE remains unclear8. Geochemical processes, such as mantle cooling and buffering reactions would have contributed7,9, but biological changes driving Cyanobacteria to become more abundant and photosynthetically active may also have played a role.

Phylogenetic and molecular clock analyses estimate that early Cyanobacteria were unicellular with the first filamentous lineages emerging shortly before the GOE10,11,12,13. This corresponded with the evolution of nitrogen fixation (in cyanobacteria)14 and a period of increased lineage diversification10 which has been hypothesized to have contributed to the GOE by enabling the formation of thick laminated microbial mats and the colonization of shallow marine coastal habitats13. The evolution of thylakoids could also have contributed to the oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere by increasing photosynthetic capacity prior to the GOE15, but a deeper biological understanding of the genetic mechanisms driving these changes is required to unravel the interplay between life and environments on early Earth.

Cyanobacteria are among the most morphologically diverse prokaryotic phyla16. They encompass a range of unicellular and filamentous strains and some of these filamentous strains develop specialised cells termed ‘heterocysts’ to fix atmospheric nitrogen under nitrogen-depleted conditions. Other, so-called ‘undifferentiated filamentous strains’ do not fix nitrogen in heterocysts, and are instead composed of a single cell type termed ‘vegetative cells’. Strains with undifferentiated filaments that lack heterocysts (although some produce hormogonia, motile filaments made of small cells) have been classified into morphological section III, whilst filamentous strains which do develop heterocysts are classified into sections IV and V depending on the presence or absence of branches17. The remaining unicellular strains belong to sections I and II.

Although it is tempting to assume that each section is evolutionarily unique, some are not. Undifferentiated filamentous strains from section III are often more closely-related to unicellular strains in sections I and II than they are to other filamentous strains with similar morphology10,11,12,18. For example, the cyanobacterial tree of life can be divided into three distinct groups, each encompassing a mixture of related strains from sections I and III. These groups are the Macrocyanobacteria, the Microcyanobacteria, and the early-branching lineages19. Early-branching lineages evolved first (and are paraphyletic because they do not include relatively recently-emerging descendants of the group’s common ancestor), followed by Micro- and Macro-cyanobacteria (which are both monophyletic). Microcyanobacteria are characterised by small cell diameters (<3 μm) and include some of the most abundant photosynthetic organisms on Earth (i.e., the marine Synechococcus spp. and Prochlorococcus spp.)20, whereas Macrocyanobacteria have large cell diameters (3 μm to 50 μm19) and include strains which are characteristic of marine microbial mats (e.g., Microcoleus spp. from section III). Pseudanabaena spp. from section III belong to the group termed ‘early-branching lineages’10,11,12,19 and represent the most ancient of extant filamentous cyanobacteria.

Molecular biology studies have provided key insights into the structure and genetic mechanisms of achieving multicellularity. For example, cyanobacterial filaments consisting of hundreds of connected cells are maintained by a unique form of cell division characterized by the absence of peptidoglycan (PG) splitting and outer membrane invagination21. Thus, within each filament, cells are enclosed by a continuous outer membrane and each cell is surrounded by PG21. Cell division is mediated by the divisome, a protein complex that includes some proteins common to different bacterial phyla and others that seem specific to cyanobacteria such as CyDiv21. However, most of this knowledge has come from studies on the heterocyst-forming strain Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (hereafter Anabaena 7120) from section IV. As a result, relatively little is known about filamentous cyanobacteria that lack specialised cells. This is important because heterocyst-forming strains like Anabaena 7120 represent a small portion of the total diversity of filamentous cyanobacteria10,11,12,13. The majority of the diversity of filamentous cyanobacteria is found in non-heterocystous strains from section III which include representatives of Microcyanobacteria and early-branching lineages as well as Macrocyanobacteria.

Intercellular molecular exchange (sometimes referred to as intercellular communication22) is known to occur along the filaments of several heterocyst-forming strains from sections IV and V, but limited studies have looked for this ability in the undifferentiated and more evolutionarily diverse filaments of strains from section III. In section IV and V filaments with specialised cells, intercellular molecular exchange allows vegetative cells to provide carbon compounds to heterocysts and heterocysts to provide N2 fixation products to the vegetative cells22,23,24. This occurs via transmission through large multi-protein complexes termed septal junctions located at intercellular septa between neighbouring cells25,26,27. These septal complexes are analogous to the “connexons” of gap junctions in large multicellular eukaryotes28,29. They traverse the septal PG layers through perforations termed nanopores which allow the transfer of metabolites such as glutamine, glutamate, β-aspartyl-arginine, and sucrose along the filament (reviewed in ref. 21). Several septal proteins are part of the septal junctions of Anabaena 7120, such as FraCD29,30,31. Others, such as HglK32 and SepI33 are needed for the formation of mature septa. FraE, encoded in the fraCDE operon of Anabaena 712030, is similar to ABC transporter permeases and is needed for heterocyst maturation31,34. Additionally, SepJ is a protein that stands out because of the strong phenotypic alterations of the sepJ mutants, including strong filament fragmentation, an early block in heterocyst differentiation, and a defect in nanopore formation and intercellular molecular exchange35,36,37,38,39. The genes encoding some of these proteins appear to be conserved in non-heterocystous filamentous strains from section III and in the unicellular Gloeocapsopsis sp. UTEX B3054, but studies have been limited to few strains (namely four)18,40,41 and their timing of evolution remains unknown.

In addition to these septal proteins, other genes have been characterised for their involvement in heterocyst differentiation from vegetative cells. These include hetR, encoding a transcriptional regulator needed for heterocyst differentiation to take place42,43,44, as well as the products of patU3 and hetZ which control the frequency of heterocysts along filaments44,45. Some of these are conserved in non-heterocystous cyanobacteria with filaments from section III40,44,46,47,48. Therefore, genes associated with the development of specialised cells may also function in other multicellular processes associated with the growth of undifferentiated filaments and clusters. Interestingly, through its association to the PatS polypeptide and other related morphogens, HetR is involved in cell patterning44,46.

Phylogenetic studies of genes encoding the septal protein SepJ and the transcription factor HetR have found that key genes for filament development evolved before heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria like Anabaena 7120 emerged18,46. Here, we implement large-scale phylogenomic analyses and microscopy with three broad aims: (i) To investigate how section III filaments are formed (e.g., are the genes characterised in complex section IV filaments of Anabaena 7120 conserved in other species with section III undifferentiated filaments?); (ii) to characterise the septal structures and kinetics of intercellular molecular exchange across section III strains from diverse positions in the cyanobacterial tree of life; (iii) to estimate when several genetic mechanisms of creating filaments evolved (namely the mechanisms involving genes sepJ, sepI, fraE, hglK, cydiv, hetR, hetZ and patU3). The results show that early-diverging filamentous cyanobacteria in section III contain nanopores and are capable of intercellular molecular exchange, albeit at slower rates than those of the model heterocyst-forming strain Anabaena 7120. Furthermore, comparative genomic analyses across 173 cyanobacterial genomes reveal that genes underlying intercellular molecular exchange and cell differentiation are widespread among filamentous cyanobacteria regardless of whether they make specialised cells or not. Genomic mechanisms of achieving multicellularity likely evolved in photosynthetic prokaryotes shortly before and during the start of the Great Oxidation Event of 2.45 to 2.2 Ga.

Results

Evolution of Cyanobacteria

To investigate whether genes characterised in the complex section IV organism Anabaena 7120 are conserved in strains with undifferentiated filaments, we began by reconstructing a global cyanobacterial phylogeny including strains from all five morphological sections and three newly-sequenced genomes. Most of the genomes used for this analysis are uncontaminated (93% lack chimeras) and highly complete (91% are more than 75% complete) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). Furthermore, the relatedness between all except two strains (namely Phormidium laminosum Gom OH1pC11 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903 which were placed based on 16S rRNA) were reconstructed based on information from at least 47 of the 141 marker genes used to reconstruct the cyanobacterial phylogeny (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Data 1). The resulting relationships between strains are broadly consistent with the families and orders identified by Strunecký et al.49, although Wilmottiaceae are not monophyletic (UFBoot 100) and Chroococcales are split into two phylogenetically distinct groups separated by Spirulinales (Supplementary Fig. 2). Importantly, deep-branching relationships between early-branching lineages, Macrocyanobacteria and Microcyanobacteria are consistent with other phylogenomic analyses4,49. For example, Anabaena 7120 shares more recent common ancestry with Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 than it does with Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 73673,4,11,19,49,50,51,52,53. Furthermore, the recently-sequenced Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261 (also known as Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-26 cyanobac1) is estimated to be an early-branching filamentous relative of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 736752,54 (UFBoot 100, red line in Fig. 1). This expands the diversity of early-branching filamentous lineages in comparison to previous studies on the evolution of cyanobacterial filaments10,11,12,13.

Homologs of genes encoding proteins required to form normal filaments (detailed in the main text) are marked with coloured squares. These are blurred to reflect a possible extraneous source of the genes if the genome is estimated to contain chimeras (defined as a GUNC fail)111. Squares with bold outlines indicate genes involved in cellular differentiation. The evolutionary tree was estimated from SSU rRNA, LSU rRNA and 139 cyanobacterial proteins using IQ-TREE v1.6.1 and rooted with Vampirovibrionia. Numerical values on bifurcating branches represent ultrafast bootstrap support values < 95. Coloured circles on branch tips represent strains whose morphological section has previously been defined (Supplementary Table 1). Black circles denote strains whose genomes were sequenced for this study. Grey bars and numbers on the outside of the tree represent percent completeness of the relevant strain’s genome, as measured by BUSCO version 3.0.2 using lineage data from Cyanobacteria110. Two strains (namely Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903 and Phormidium laminosum Gom OH1pC11) whose genomes have not been sequenced were included based on ribosomal RNA because they showed potential for FRAP and septal peptidoglycan disk visualisation, which later proved unsuccessful. Genus names represent strains whose septal structures were investigated. Pseudanabaena marks Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367, Nodosilinea marks Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 and Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298, Phormidesmis marks Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC007 and Anabaena marks Anabaena 7120. Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261 is highlighted in red with an arrow. Numerical source data underlying completeness plots in this figure are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

We also find that some branching filamentous cyanobacteria in section V (including Fischerella sp. PCC 9605, Mastigocoleus testarum BC008 and Mastigocladopsis repens PCC 10914) are more closely related to non-branching filamentous cyanobacteria from section IV than they are to other branching strains (Fig. 1). This implies that there have been transitions between branching (section V) and non-branching (section IV) phenotypes during the course of their evolution. This could be due to alterations in cell division-related genes such as mre55 because branches are created in Mastigocladus laminosus by randomized directions of cell growth56.

Distribution of multicellularity genes in the Cyanobacterial tree of life

Homologs of genes encoding key septal proteins (i.e., fraC, fraD, fraE, hglK, sepJ and sepI) and regulators of cellular differentiation and pattern formation (i.e., hetR, hetZ and patU3) originally identified in heterocyst-forming strains including Anabaena 7120 (see introduction for details) were found in several filamentous strains which lack heterocysts (section III) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). These non-heterocystous filamentous strains are taxonomically diverse with cell sizes ranging from < 2 μm to > 5 μm in diameter19. They include early-branching lineages (such as Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 and Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261), Microcyanobacteria (such as Prochlorothrix hollandica PCC 9006, Limnothrix sp. PR1529 and Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330) and Macrocyanobacteria (including Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC007, Trichodesmium erythreaum IMS101, Oscillatoria sp. PCC 10802, Spirulina subsalsa PCC 9445, Crinalium epipsammum PCC 9333 and Microcoleus chthonoplastes PCC 7420). The genomes of most of these strains contain homologs of fraC, fraD, fraE, hglK, sepJ, sepI, hetR, hetZ, patU3 and an uncharacterised gene named all2344 (see supplementary text for further details). Three of these genes (namely fraC, fraD and fraE) tend to be co-localised in the genomes (Supplementary Table 3, further detail in supplementary text) potentially to facilitate joint expression. However, early-branching filamentous lineages are unique because most of them (all Pseudanabaena spp. but not Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261) lack genes encoding some of the septal junction proteins, namely fraC, fraD and hglK, which encode proteins involved in intercellular molecular exchange and nanopore formation in Anabaena 7120. The same early-branching filamentous lineages also lack genes involved in heterocyst differentiation and pattern formation (namely hetR, hetZ, patU3) (Fig. 1).

Unlike filamentous cyanobacteria, most unicellular cyanobacteria lack sepJ, fraC, fraD, hetR, hetZ and patU3, supporting these gene’s relevance for filamentous phenotypes. Other genes required to maintain and develop filaments in Anabaena 7120 are present in several unicellular strains (Fig. 1). These include fraE encoding a permease, cyDiv encoding a cyanobacterial division protein originally described in filamentous cyanobacteria, hglK encoding a pentapeptide-repeat-containing protein, and sepI encoding a septal protein containing a large coiled-coil domain.

Intercellular molecular exchange and septal structures

Given the propensity of genes encoding septal proteins in non-heterocystous cyanobacterial genomes, we tested directly for intercellular molecular exchange in four non-heterocystous filamentous cyanobacteria (section III) from diverse positions in the cyanobacterial tree of life. In these strains, we tested for intercellular molecular transfer of two fluorescent markers, calcein and 5-carboxyfluorescein (5-CF) (622.5 Da and 376 Da respectively, both negatively charged but to different extents57), by means of FRAP analyses31,36. In these analyses, hydrophobic, non-fluorescent forms of the markers diffuse into the cytoplasm of the cells where they are processed to hydrophilic and fluorescent forms. The fluorescence is bleached out in a single cell by an increased laser intensity, and recovery of fluorescence resulting from transfer of the marker from adjacent cells by diffusion is followed for a short time. The recovery rate constant (R) describes how quickly each marker is transferred from adjacent cells through their septal junctions31.

FRAP analyses of an early-branching filamentous strain, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367, and the filamentous Microcyanobacterium Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330, confirm fluorescence recovery of 5-CF in bleached cells (Fig. 2), despite the lack of the septal junction genes fraC and fraD in Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 (Fig. 1). Intercellular molecular transfer of at least one marker was also observed in another filamentous Microcyanobacterium, Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298, and a Macrocyanobacterium which lacks differentiated cells, Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC007, albeit at slower rates than those of the model strain, Anabaena 7120 (Table 1). Notably, with some strains and markers, two populations of cells could be discerned regarding intercellular molecular exchange; communicating cells (typically, R values > 0.01 s−1) and non-communicating cells. The latter exhibit very low or null R values, suggesting regulation of the process as described in Anabaena 712058. These two populations were found in the Macrocyanobacterium Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 with calcein; in the two Microcyanobacteria, Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 with 5-CF and Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 with calcein and 5-CF; and in the early-branching cyanobacterium Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 with 5-CF. Therefore, our results indicate that regulated intercellular molecular exchange occurs beyond the heterocyst-forming strains in filamentous Macro-, Micro- and early-branching cyanobacteria that lack specialised cells. Only the early-branching lineage, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 was able to transfer 5-CF but not calcein (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Examples of FRAP analysis for filaments from independent cultures of Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 (A) and one filament of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 (B) grown in BG11 and ASW medium, respectively. Filaments were labelled with 5-carboxyfluorescein (5-CF) or calcein as indicated, and subjected to FRAP analysis. No calcein recovery was observed for Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367. Images are shown at the times indicated after bleaching. The plots show the recovery of fluorescence intensity in the bleached cell over time after the bleaching event (note the different scales). The line is an exponential curve fitted to the data points as described in Materials and Methods. Scale bars, 5 µm. Note the different magnifications in the 5-CF and calcein experiments for PCC 9330. Numerical data underlying the plots are available in Supplementary data 3 and 4.

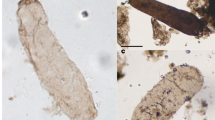

In Anabaena 7120, intercellular molecular transfer takes place through proteinaceous septal junction structures that traverse the septal PG through holes termed nanopores29,34,58. Nanopores can be conveniently visualized in septal PG disks that are observed in murein sacculi preparations of filamentous cyanobacteria59. We therefore looked for the presence of nanopores in septal disks from some of the strains for which we observed intercellular molecular exchange. Nanopores were observed in Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007, the two Nodosilinea strains, PCC 9330 and LEGE 07298, and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7376 (Fig. 3). Interestingly, the septal disks of Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 (Macrocyanobacteria) were large, about 2.36-fold larger than those of Anabaena 7120, whereas the disks of Nodosilinea spp. (Microcyanobacteria) were smaller than those of Anabaena 7120, and the septal disks of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7376 (an early-branching cyanobacterium) were even smaller (Table 1). The number of nanopores in Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 and the two Nodosilinea strains was about 17% and 7-13%, respectively, of the number found in Anabaena 7120, although nanopore size was not very different (about ±20% the size in Anabaena 7120). In contrast, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7376 had a single hole at the centre of the disk that was larger than the nanopores of any other cyanobacterium; we denote it a “central pore”. Together, FRAP analysis and visualization of septal PG disk nanopores indicate that structures for intercellular molecular exchange are present in filamentous Macrocyanobacteria, Microcyanobacteria and early-branching Pseudanabaena, although the structures of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7376 display unique characteristics.

Panels indicate the murein sacculus, septal disks and nanopores of Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 (A), Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 (B), Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 (C) or the murein sacculus, septal disk and single central pore of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 (D). The PG was isolated and visualized by transmission electron microscopy as described in Materials and Methods.

Timing the origin of genes underlying filamentous morphology

Relaxed molecular clock analyses were implemented to estimate when genetic mechanisms of creating filaments emerged. The timing of origin for relevant genes was estimated by testing two hypotheses (Fig. 4) using information derived from reconciliations between the evolutionary history of each gene (Supplementary Figs. 3–S12) and the cyanobacterial tree of life (i.e., genome phylogeny; Fig. 1). These hypotheses state that either the gene arose in the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all filamentous cyanobacteria (Node 3), or that the gene arose in the MRCA of filamentous Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria (Node 5), excluding early-branching lineages such as Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 and Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261.

Phylogenetic evidence suggests that key genes for maturation of septal structures in filaments appeared in ancestral cyanobacteria prior to hetZ, patU3 and hglK. These include sepJ and sepI genes encoding septal proteins, as well as the permease encoded by fraE and a cyanobacterial cell division protein encoded by cyDiv. This is because the sepJ and sepI homologs present in early-branching strains are more basal than those of later-branching Micro- and Macro-cyanobacteria (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6), consistent with vertical inheritance from the MRCA of all filamentous species (Figs. 4 and 5, node 3). As a result, sepI and sepJ must have first emerged somewhere on the lineage between nodes two and three (Figs. 4, 5). Molecular clock analyses estimate that these genes existed in the Neoarchaean from ~2.70 to ~2.60 Ga (95% credibility intervals (CI), span 2.875 to 2.384 Ga (Table 2). Two additional genes, namely hetR encoding the heterocyst master regulator and an uncharacterised paralog of hetZ termed the ‘hetZ relative’, may also have appeared on this lineage despite their absence from all early-branching lineages except Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261. This early-branching strain encodes hetR and a hetZ-relative homologs which are basal to those of other cyanobacteria (Supplementary Fig. 4, Posterior Probability 85 and Supplementary Fig. 7 PP 100), consistent with vertical inheritance from node three (Figs. 4, 5) and a subsequent loss of the gene in Pseudanabaena spp. (Fig. 6).

A Molecular clock timeline estimates for genes highlighted in boxes of matching colour in (B). The oldest microfossil of filamentous cyanobacteria is either not applied (top panel) or constrains the MRCA of all filamentous cyanobacteria (node 3) to more than 1.9 Ga (bottom panel). B Simplified evolutionary tree of Cyanobacteria with estimated origins of genes associated with filament development annotated in coloured boxes. Black triangles and labelled lineages indicate predominantly filamentous clades, whereas white triangles and unlabelled lineages indicate predominantly unicellular clades. Some of the cartoon images are adapted from ref. 119. The number of strains in each clade are presented in parentheses alongside the clade names. Node numbers are the same as in Fig. 4. Macro. refers to Macrocyanobacteria, Micro. to Microcyanobacteria and EBL to Early-branching lineages.

Genes inherited from the MRCA of Cyanobacteria (yellow), the MRCA of all filamentous strains (orange) or the MRCA of Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria (pink) are denoted on a simplified cyanobacterial phylogeny (black lines) and with coloured squares beneath each strain or clade name. Some genes have appeared in Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB261 following horizontal gene transfer from other cyanobacteria (dark grey background), whereas others have been inherited vertically (plain white background) or have unknown origins (light grey background). Branch lengths are arbitrary and some lineages have been removed for simplicity.

Further genes guiding the development of differentiated cells (namely hetZ and patU3) and architecture of the intercellular septa (hglK) show evolutionary patterns which are consistent with vertical inheritance from the MRCA of Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria (Fig. 5, node 5, Supplementary Figs. 7, 9, 10). This is because the patU3 and hglK of most Macrocyanobacteria are monophyletic (Supplementary Fig. 9 PP 89 and Supplementary Fig. 10 PP 95) with strains of Microcyanobacteria forming an outgroup. Similarly, the earliest-branching hetZ homologs are found in strains of Microcyanobacteria (namely Limnothrix spp.) with Macrocyanobacterial hetZ homologs diverging later (Supplementary Fig. 7). Although the early-branching strain Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB-261 also hosts homologs of hetZ and patU3, they do not occupy basal positions in their respective protein phylogenies, so the most parsimonious explanation for their evolutionary trajectories involves a horizontal gene transfer from other cyanobacteria. Taking this into account, we posit that hetZ, patU3 and hglK evolved somewhere on the lineage between nodes four and five (Fig. 5), which existed at the onset of the GOE from ~2.52 to ~2.47 Ga (95% CI span 2.700 to 2.289 Ga) (Fig. 5, Table 2). Results for fraC and fraD were inconclusive because their phylogenies include many polytomies and low support values which hinder inferences about their origins (Supplementary Figs. 11, 12).

Two genes, cyDiv which is involved in cell division to maintain straight filaments60 and fraE which encodes a permease30, probably pre-date other genes involved in cell differentiation and the production of septal junctions because they are encoded in the genomes of many unicellular strains, including one of the earliest-branching cyanobacteria, Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421. As a result, their presence alone is not a good marker of filamentous morphology; indeed, they exhibit evolutionary trajectories indicative of vertical inheritance from the most recent common ancestor of all cyanobacteria (Fig. 5, node 1, Supplementary Figs. 3, 8). This observation places a younger bound on the origin of cyDiv and fraE in the Mesoarchaean, 2.95 Ga (95% CI span 3.047 to 2.769 Ga) (Fig. 5, Table 2).

Several unicellular lineages have emerged from ancestors with genes encoding components of septal junctions and cell patterning (Fig. 5). These include Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (model strains in many experimental analyses) as well as Dactylococcopsis salina PCC 8305, Geminocystis hermanii PCC 6308, Pleurocapsa sp. PCC 7319 and Prochloron didemni (which is a symbiont61). Many have retained sepI and hglK, which evolved in or after, respectively, the most recent common ancestor of filamentous strains (Fig. 1). Furthermore, protein phylogenies are consistent with a backward transition from filamentous to unicellular phenotypes in these organisms because they have lost sepJ, fraC and fraD during the course of their evolution (Supplementary Fig. 13).

Calibrating the origin of filamentous cyanobacteria

The ages of origin of these multicellularity genes were estimated by running molecular clock analyses with several microfossil-based calibrations (Supplementary Text) that have been applied in previous studies62,63,64. One of these is a microfossil of a filamentous cyanobacterium which constrains node 3 of Figs. 4 and 5 (the MRCA of all filamentous species, including early-branching lineages) to more than 1.9 Ga (Supplementary Text). We tried removing this calibration to reflect an unknown origin of filamentous morphology and found similar estimated timings for the emergence of multicellularity genes in our molecular clock (Table 2). Other calibrations have been tested in previous studies65.

Discussion

Timing of evolutionary events and geological records

The evolution of cyanobacterial filaments from primitive unicellular morphologies has fundamentally changed the landscape on Earth. Here, we have provided insight into how cyanobacterial filaments evolved, finding that it began with genes encoding septal proteins which localise at the septa between cells, and was followed by genes associated with cell patterning. The timing of emergence of these multicellularity genes also coincides broadly with atmospheric oxygenation, lending support to the hypothesis that the evolution of filaments in Cyanobacteria contributed to the GOE11.

It has previously been hypothesized that the evolution of filaments caused the GOE by facilitating the formation of robust microbial mats11,13 which are documented in geological records from the late Archean66. Various factors contribute to the ability to form microbial mats, including the presence of sheaths, motility, and large cell diameters13,67. Large cell size is characteristic of Macrocyanobacteria and here we find that the Crown group of this clade emerged shortly after the evolution of genes (such as hglK, patU3 and hetZ) involved in septal maturation and cellular differentiation in filaments at the start of the GOE ~ 2.45 Ga (Fig. 5, node 6, Table 2). However, it is important to note that other factors could also have contributed to the rapid diversification of Cyanobacteria across land and marine coastal environments in the lead up to the GOE. These include phosphorus availability68,69, competition for light70, UV-absorbing pigments, nitrogen fixation and changes in arrangement of the photosynthetic machinery13,71,72.

Intercellular molecular exchange is not limited to heterocystous strains

Our phylogenetic reconstructions reveal that genes required to build septal junctions and create cell patterning are not restricted to heterocyst-formers, but widespread among most filamentous cyanobacteria which lack specialised cells. Although some non-heterocystous filamentous cyanobacteria have been reported not to exchange fluorescent markers between cells in laboratory conditions36,73, others such as Microcoleus vaginatus have been found to exchange markers at rates similar to Anabaena 7120 despite its lack of differentiated cells73. Our study expands the diversity of strains known to exhibit intercellular exchange via septal pores and shows that they also regulate septal junction function since both communicating and non-communicating cells are observed in all cases. Given the broad distribution of these traits and the early evolution of septal genes, it is possible that regulated intercellular exchange was a feature of filamentous cyanobacteria since they first evolved in the Archean. The widespread distribution of these traits (intercellular molecular exchange and, potentially, cell patterning) in filamentous cyanobacteria implies that the formation of heterocysts could have evolved in a cyanobacterial branch that had the necessary “pre-requisites” for the heterocyst-containing filament to work efficiently. In this context, it is important to note that N2 fixation is also widespread in non-heterocystous cyanobacteria17.

The role of heterocyst differentiation- and pattern formation-like genes and of intercellular molecular exchange in non-heterocystous strains from section III remains unknown. It is possible that hetR, hetZ and patU3 help to locate places of filament breakage (i.e., formation of necridia) to facilitate filament dissemination in the environment74. Intercellular molecular exchange, on the other hand, appears to synchronize circadian rhythms throughout the filaments. Under N-sufficient conditions, in which Anabaena 7120 filaments are composed only of vegetative cells, intercellular molecular exchange enables the cells to synchronize their behaviour so that circadian gene expression remains spatially-coherent along each filament75. In doing so, they enable all cells in the filament to function together as a single organismal unit. Given the distribution of these genes and traits throughout the filaments of Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria, circadian rhythm synchronization and necridia localization could be general properties of all filamentous cyanobacteria, except potentially of the early-branching lineages.

Early-branching lineages emerged before all other filamentous cyanobacteria (Fig. 6) and several of them (namely the Pseudanabaena spp.) are unique because they lack several septal junction proteins and cell differentiation genes found in filamentous Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria, including Anabaena 7120 (Fig. 1). Perhaps as a result, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 has a unique septal disk with a single pore, while filamentous Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria in sections III, IV and V, including Anabaena 7120 have numerous smaller pores (Table 2). Oscillatoria lutea also has a single central pore, but it is smaller than that of Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 (i.e., 23.32 ± 0.52 nm73 instead of 40.10 ± 20 nm) (Table 1). Neither strain can transfer calcein along their filaments, but we have shown that Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 can transfer 5-CF which is significantly smaller than calcein (about 376 vs. 622 Da)57. This raises the possibility that Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 (and perhaps other early branching filamentous lineages) might not be capable of exchanging some of the larger compounds that might be transferred in filamentous Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria.

Conclusions

Overall, our phylogenomic analyses and laboratory studies help explain how one of life’s major transitions - from single isolated cells to interconnected filaments – occurred to cyanobacteria in the lead-up to the GOE. We find that key physiological features, including intercellular molecular exchange and septal pores are widespread in both early-branching and more diverged filamentous lineages throughout the cyanobacterial tree of life. Furthermore, genes encoding key components of septal structures (namely sepJ, sepI, and fraE) and cell patterning (namely hetR) evolved in the Neoarchaean ~2.6–2.7 billion years ago (Ga), shortly before Earth’s atmosphere first became oxygenated during the GOE.

Methods

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenomic analyses were performed using data from 173 cyanobacterial genomes chosen to encompass all five morphological sections (Supplementary Table 1), including at least one representative from all major clades of strains with unicellular or filamentous morphologies11,17,52,76. All were downloaded from the NCBI except the genomes of Phormidium sp. CCY1219 (synonymous with DSM 101373), Lyngbya sp. CCY1209 (synonymous to DSM 101363) and Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330, which were sequenced de novo and uploaded to GenBank to improve the representation of filamentous strains from section III. An explanation of how these genomes were sequenced is presented below in the subsection entitled ‘Genome Sequencing and Assembly’.

A phylogenomic tree of Cyanobacteria was estimated with 139 orthologous protein-coding genes and 2 ribosomal RNAs that have been used previously for this purpose because they are universally present in cyanobacterial taxa, evolutionarily conserved and rarely duplicated64. Orthologs of these proteins and ribosomal RNAs were collected with BLASTP or BLASTN respectively using nine query sequences from diverse cyanobacteria (Supplementary Table 4) and an e-value cut-off ≤ 1 × 10−25. Hits for each ribosomal RNA and orthologous protein were aligned with the L-INS-i strategy in MAFFT v7.42777, resulting in 141 alignments, each of a separate protein or rRNA. Each alignment was then trimmed to remove positions with ≥85% gaps using AlignmentViewer (available at http://sdsssdfd.altervista.org/arklumpus/AlignmentViewer/AlignmentViewer.html). Abnormally short and phylogenetically distant sequences (totalling 273 out of 23,315, just 1.2%, Supplementary Data 5) were manually removed to minimise the inclusion of paralogs and laterally transferred genes. The best substitution model for each protein and rRNA was then chosen using ModelFinder78 and the cyanobacterial tree topology was reconstructed in IQ-TREE v1.6.779 using a partitioned analyses where each partition represents the alignment of a different protein-coding gene or ribosomal RNA. Strains which lacked some of the protein-coding genes (either as a result of incomplete sequencing or genome reduction, Supplementary Data 1) were therefore absent from some partitions, and placed in the tree based on a more limited dataset. The -sp option was applied to account for heterotachy80 by allowing each partition to evolve under its own set of branch lengths. Branch supports were estimated by calculating 1000 replicates of ultrafast bootstrap analyses81 and the SH-like approximate likelihood ratio test82. The tree was rooted using four Vampirovibrionia, the sister Phylum of Cyanobacteria2.

A sensitivity test was conducted to test whether data from incomplete genomes impacted the relationships estimated between strains. This was conducted by removing sequence data from all three free-living cyanobacterial strains with less than 50% completeness (namely Phormidium laminosum Gom OH1pC11, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903 and Pseudanabaena sp. CRU210), and all three cyanobacterial strains which fail GUNC contamination checks due to having more than 5% contamination (namely genome JTJD00000000.1 from Aphanocapsa montana BDHKU210001, genome RSCK01000001.1 from Chroococcidiopsis cubana SAG39.79, and genome NC_014501.1 from Cyanothece sp. PCC 7822). We then reconstructed the cyanobacterial phylogeny from the remaining strains (using the same methods as above), all of which are at least medium-quality according to the genome reporting standards for SAGs and MAGs83. The resulting topology was the same as that in Fig. 1, except for one slight change to the relationship between Leptolyngbya sp. hensonii and Neosynechococcus sphagnicola sy1 (Trichocoleusaceae and Neosynechococcaceae families, Supplementary Fig. 14). No changes were found in the relationships between Macrocyanobacteria, Microcyanobacteria and early-branching lineages. Furthermore, Leptolyngbya sp. FACHB261 remained sister to Pseudanabaena spp. This indicates that deep branching relationships of cyanobacteria including those used to estimate when genes enabling the transition from unicellular to filamentous morphologies evolved are robust to the inclusion of a minority of incomplete genomes when partitioned analyses are applied.

To study filament formation, homologs of eight proteins involved in filament development (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Table 5) were identified in BLASTP with a permissive e-value cut-off ≤ 1 × 10−5 to ensure that no homologs were missed. Further stringency criteria (based on alignment length, presence of transmembrane helices, and coiled-coils) were applied to identify SepI, to distinguish HglK from other proteins with pentapeptide repeat regions and different functions32,84 and to distinguish SepJ from homologous DMT permeases with no known role in filament formation18,35,37. Whilst SepJ contains N-terminal coiled-coils and C-terminal transmembrane helices, related DMT permeases do not18,35,37,85, so homologs which lacked coiled-coils (estimated in ncoils86 with default parameters) and transmembrane helices (estimated in TMHMM v.2.087 with default parameters) were removed. Similarly, SepI is characterised by the presence of N-terminal coiled-coils33, so homologs of SepI which lacked coiled-coils (estimated in ncoils86 with default parameters) were removed. HglK contains a pentapeptide repeat region of 192 amino acids32 and similar pentapeptide repeat regions are present in other proteins with different functions84. To ensure these weren’t considered, homologs which aligned to less than 96% of the length of the experimentally-characterized protein required for long filaments in Anabaena 712032 were removed. This 96% was informed by the distribution of alignment lengths in our hits, which varied from 41 to 767 amino acids with a noticeable drop-off below 700 (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Phylogenies of each protein were then estimated by aligning the retained homologs for each enzyme in MAFFT v.7.42777 using an accurate iterative local alignment strategy (L-INS-i). Phylogenetically uninformative columns containing ≥ 85% gaps were removed, and the evolutionary histories of each protein were reconstructed in one of two softwares depending on which took the least time to converge: Either MrBayes v3.2.7a88 with a mixed amino acid substitution model prior, invariant sites and gamma distributed rates (all proteins except HglK), or Phylobayes v4.189 (HglK) with the GTR-CAT + G substitution model. Convergence was tested in different ways depending on the software, but at least two replicate independent chains were always compared and the first 25% of iterations were discarded as burn-in. Protein trees reconstructed in MrBayes were considered converged when their average standard deviation of split frequencies (ASDSF) were ≤ 0.01 and potential scale reduction factors (PSRF) between 1.00 and 1.02. Whereas protein trees reconstructed in Phylobayes were considered converged when all effective sample sizes and relative differences (assessed with tracecomp implemented in Phylobayes) were > 50 and < 0.3 respectively. The resulting phylogenies were rooted on nodes with low ancestor deviation values predicted by MAD v2.290 with default parameters and the -t option to retain short branches (Supplementary Table 6). All trees were visualised in TreeViewer v. 2.2.091.

Chronology

To determine when filament-associated proteins emerged in Cyanobacteria, we manually compared their evolutionary histories with a time-calibrated species tree of the cyanobacterial phylum to look for evidence of vertical inheritance from one of three ancestors: Namely the MRCA of all Cyanobacteria, the MRCA of filamentous lineages, or the MRCA of Macro- and Micro-cyanobacteria. The time-calibrated species tree was estimated by implementing a Bayesian relaxed molecular clock in Phylobayes 4.189 using the topology described above (Fig. 1), the CAT-GTR substitution model, uncorrelated gamma multipliers51,92, a birth-death prior on divergence times, a trimmed alignment of SSU and LSU rRNA and five to six calibration points which have been applied and tested previously3,50,62. These include the following: (1) cyanobacteria with akinetes were constrained to arise 1.600 to 1.888 Ga and cyanobacteria with apical cells between 1.700 and 1.888 Ga based on fossil evidence93,94,95; (2) Endosymbionts were constrained to arise before their hosts, specifically Richelia intracellularis HM01 and R. intracellularis HH01 before Hemiaulus fossils formed 110 Ma96,97; (3) UCYN-A was constrained to diversify from UCYN-A2 before their host Braarudosphaera begelowii appeared 91 Ma98,99; (4) Geochemical evidence of the Great Oxygenation Event is applied such that Cyanobacteria first diversify prior to 2.32 Ga100, but after molybdenum isotopes document ‘whiffs’ of atmospheric oxygen101 and stromatolites with structures indicative of oxygenic photosynthesizers appear 3 Ga102. Soft bounds were applied to each calibration to allow 5 % of the prior probability density to fall outside of the specified bounds. An additional calibration constrains the origin of filamentous cyanobacteria to ≥ 1.9 Ga based on filamentous microfossils found in the Belcher Islands103. Simulations were run with and without this calibration to reflect a range of views on where filamentous morphology arose in the cyanobacterial tree. Further explanation of why these microfossils were chosen are present in the supplementary text. Convergence was assessed with tracecomp and consensus trees generated with readdiv (both implemented in Phylobayes) when all effective sizes ≥ 50 and all relative differences ≤ 0.3, after the first 25% of iterations were discarded as burn-in.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Cultures of Phormidium sp. CCY1219 (synonymous to DSM 101373) and Lyngbya sp. CCY1209 (synonymous to DSM 101363) were obtained from Culture Collection Yerseke, having been originally isolated from sediments present in salt beds of Olhao, Portugal. Their mono-phototrophic cultures were isolated by plating and grown in ASN3 medium at 20 °C on a 16 h:8 h light:dark cycle with 10–20 μmol m−2 s−1 of white light. Genomic DNA was extracted from 1.8 ml of culture with a DNeasy ultraclean microbial kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and stored in 10 mM Tris buffer at pH 8 and −80 °C until paired-end reads of 2 ×150 bp were sequenced on a NextSeq 500/550 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at the University of Bristol Genomics Facility, UK.

Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 was obtained from the Pasteur Culture Collection. It was grown in BG11 medium (see above) at 30 °C in the light (ca. 25–30 μmol photons m−2 s−1) in shaken (100 rpm) liquid cultures. Its genomic DNA was extracted from an axenic 50 ml of culture using the Molecular Biology Kit (Bio Basic) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (3000 × g, 5 min), resuspended in 50 ml of distilled water and the protocol was modified to include 0.1 mm glass beads (Qiagen, Germany) to increase DNA extraction by mechanical lysis. Purified genomic DNA from this culture was stored in nuclease-free water at 4 °C until paired-end reads of 2 × 150 bp were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq500 at the Centro Andaluz de Biología Molecular y Medicina Regenerativa, Seville, Spain.

All reads were trimmed and assembled into draft genomes using the methods described in ref. 104. Briefly, this included trimming sequences of poor quality base pairs with Trimmomatic v. 0.39105 and assembling the resulting reads into contigs using SPAdes v3.14.0106. Any non-cyanobacterial contigs were identified and removed using a combination of BLAST and a de bruijn graph visualisation approach developed for the de novo assembly of Phormidesmis priestleyi BC1401107. Briefly, this included discarding contigs which either did not contain hits to one of 1054 core cyanobacterial sequences108(identified using BLAST with an e-value less than ≤1 × 10−10) or had different read depths to contigs containing hits to these sequences. The resulting draft genomes were submitted to JGI IMG/ER109 for annotation (GOLD Analysis Project IDs: Ga0436897, Ga0436900 and Ga0591443) and deposited in DDBJ/ENA/Genbank repositories within BioProject PRJNA1053249 with BioSample accessions SAMN38850749, SAMN38850750 and SAMN38850751. Assembly statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 7.

Completeness and contamination estimates were generated for the genomes with BUSCO version 3.0.2110 using lineage data from Cyanobacteria and GUNC version 1.0.6111 with default parameters.

Septal structures and intercellular molecular exchange

Septal structures and intercellular molecular transfer were investigated in four cyanobacteria from previously understudied groups (morphological section III): Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 9330 (here renamed Nodosilinea), Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367. Other strains attempted include an additional early-branching strain (Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903), two Macrocyanobacteria (Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106 and Phormidium laminosum Gom OH-1-pC11) and one Microcyanobacterium (Prochlorothrix hollandica PCC 9006). For the Macrocyanobacteria, isolation of clean murein sacculi failed for Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106 and no clear micrographs of septal disks nor any staining for FRAP analysis could be obtained from Phormidium laminosum Gom OH-1-pC11. For the Microcyanobacterium Prochlorothrix hollandica PCC 9006, not enough biomass for murein isolation was obtained. For the early branching strain, Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903, no clear micrographs of septal disks were obtained and FRAP analysis was difficult because of very small, motile filaments.

Culturing conditions

Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330, Lyngbya sp. PCC 8106, Phormidium laminosum Gom OH-1-pC11 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 6903 were grown in BG11 medium with NaNO3 as the nitrogen source and ammonium citrate instead of ferric ammonium citrate used in the original recipe17 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 was grown in artificial seawater medium112,113, modified to lack NaSiO3 and vitamins, at 30 °C in the light (ca. 25–30 μmol photons m−2 s−1) in shaken (100 rpm) liquid cultures. Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 was grown in BG11 medium17 at 20 °C in the light (20 μmol photons m−2 s−1) without agitation. Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 was grown in DSMZ medium 1678 (BA + 50 + B + N/2) at 28 °C in the light (30 μmol photons m−2 s−1) and constant agitation (110 rpm). Prochlorothrix hollandica PCC 9006 was grown in BG110 + 2 mM NaNO3 at 20 °C in the light (20 μmol photons m−2 s−1) without agitation.

Peptidoglycan sacculi isolation and visualization

Peptidoglycan (murein) sacculi were isolated and visualized by first harvesting the filaments of each strain using centrifugation (3000 × g, 5 min, room temperature). Cells of Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 and Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 were frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 °C and shipped on dry ice to Seville for further analysis. Murein sacculi were isolated using a method modified from that of114: Pellets from each strain were resuspended in 1 ml PBS buffer and homogenized by sonication using a sonicator bath. The resulting broken filaments were added dropwise to boiling 6% (w/v) SDS and kept in this boiling condition for 2 h, whilst carefully adding distilled water to avoid desiccation. Samples were incubated overnight at 37 °C with gentle stirring. Subsequently four additional boiling steps were carried out: (i) 1 h of boiling and ultracentrifugation (Beckmann 90 Ti rotor, 320,000 × g, 25 °C, 35 min) followed by sample resuspension in 3 ml of 3% (w/v) SDS, (ii) 2 h of boiling, centrifugation as previously described, and pellet resuspension in 2 ml distilled water and 0.2 ml of 6% (w/v) SDS, (iii) 2 hours of boiling, washing procedure by centrifugation, resuspension in 1.5 ml of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.8) and chymotrypsin or trypsin treatment (100 μg/ml) overnight at 37 °C. The incubation was terminated by adding 0.5 ml distilled water and 0.75 ml 6% (w/v) SDS. Finally (iv) 2 h boiling, sedimentation by centrifugation as previously described, washing with distilled water several times to remove SDS by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 5 min at 25 °C), resuspension in 100 μl of distilled water. The resulting samples were stored at 4 °C. Samples of Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 and Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 were further washed twice with 1% (v/v) PBS and subsequently with distilled water. The purified sacculi were deposited on Formvar-carbon film-coated copper grids and stained with 1% (w/v) uranyl acetate. All the samples were examined with a Zeiss LIBRA 120 PLUS electron microscope at 120 kV (Servicio de Microscopía, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain).

5-CF and calcein staining

The kinetics of intercellular exchange were measured by staining cyanobacterial cells with calcein or 5-carboxyfluorescein (5-CF) and visualising them by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The AM (acetoxymethyl) ester derivatives of calcein and 5-CF were loaded into the cytoplasm of cyanobacterial cells using protocols modified from those described by Mullineaux et al.36 and Merino-Puerto et al.31, respectively. To load calcein into the cytoplasm of Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367, a total of 0.5 ml of each cell culture were harvested by gentle centrifugation (3000 × g, 5 min) washed three times in the respective growth medium as described above, resuspended in 0.5 ml fresh medium, and mixed with 20 μl of calcein AM solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1 mg ml−1). The cells were incubated in dim light at 30 °C for 90 min before harvesting and washing 3 times in fresh BG11 or artificial seawater medium, respectively. Calcein staining of Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 and Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 was performed in the same way with the following modifications: After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in double the volume (1 ml) of the respective growth media. A smaller volume (namely 12 μl) of calcein AM (Cayman Chemical; 1 mg ml−1) was added. The suspension was incubated in darkness for 90 min at 28 °C or 20 °C respectively, and further treated as described above. To stain Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330 and Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367 with 5-CF, a total of 1 ml of each cell culture were harvested by gentle centrifugation (3000 × g, 5 min), washed three times in the respective growth medium, resuspended in 1 ml fresh medium, and mixed with 12 μl of 5-CF AM solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 5 mg ml−1). The cells were incubated in dim light at 30 °C for 30 min before harvesting and washing 3 times in fresh medium. 5-CF staining of Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 and Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 was performed as described above but using 5-CF AM from Thermo Fisher Scientific at a lower concentration of 1 mg ml−1 and incubating the cells in complete darkness for longer (specifically 60 min) at lower temperatures (28 °C or 20 °C respectively). For both markers, filament suspensions were spotted onto BG11-agar (filaments were allowed to settle down by drying off excess liquid) and small agar blocks with labelled filaments were transferred to a custom-built temperature-controlled sample holder. The temperature was kept at the respective growth temperatures during subsequent FRAP assays.

FRAP analyses

After bleaching a single cell, we measured fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). Subsequent imaging can reveal recovery of fluorescent 5-CF or calcein in the bleached cell due to simple diffusion from adjacent cells through septal junctions57,115. For 5-CF in Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330, filaments were imaged with a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser-scanning microscope with a 488-nm line argon laser as the excitation source; fluorescence emission was monitored from 500 to 541 nm with a 150-µm pinhole. For 5-CF and calcein in Pseudanabaena sp. PCC 7367, and calcein in Nodosilinea sp. PCC 9330, filaments were imaged with an Olympus Fluoview FV300 microscope with a 488-nm line argon laser as the excitation source; fluorescence emission was monitored from 500 to 527 nm with a 150-µm pinhole. After an initial image was recorded, bleaching was carried out by an automated FRAP routine as previously reported36. Post-bleach images were taken in XY-mode approximately every two seconds for up to 1 to 2 min.

Fluorescence images of Nodosilinea sp. LEGE 07298 and Phormidesmis priestleyi ULC 007 stained with either calcein or 5-CF were acquired with an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM; Leica SP8) using a HC PL APO x63/1.40 oil objective. Cells were excited at 488 nm and fluorescence emission collected from 500 to 540 nm with a 600-μm pinhole. After the bleach, images were recorded every second for 35 s (5-CF) or every two seconds for up to 1 min (calcein). Images were analysed with Leica LAS X (version 3.7.4) and FIJI116.

For FRAP data analysis, kinetics of fluorescent marker transfer between cells located in the middle of filaments was quantified by determining the recovery rate constant R from the formula CB = C0 + CR (1 – e-2Rt), where CB is fluorescence in the bleached cell, C0 is fluorescence immediately after the bleach and tending towards (C0 + CR) after fluorescence recovery, t is time, and R is the recovery rate constant due to transfer of the marker from the neighbouring cells117. Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel and OriginPro 2019 (OriginLab) of the GraphPad Prism.

Statistics and reproducibility

Bayesian statistical analyses for the evolutionary biology aspects of this work were performed with Phylobayes version 4.1, and MrBayes version 3.2.7a using parameters and priors described in the methods section. FRAP data analyses, used to visualise intercellular molecular transfer in phylogenetically distant filamentous cyanobacteria, were performed following the procedure described in the Methods section, using Microsoft Excel, OriginPro 2019 (OriginLab), and GraphPad Prism. Raw data are provided in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Data 4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data is available in the supplementary materials and in our Open Science Framework repository at the following https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8BXAR. This includes newick formats of the protein phylogenies, species tree of Cyanobacteria and molecular clocks used to present Fig. 1 and Fig. 5. Numerical source data underlying Fig. 2 is presented in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Data 4. Numerical source data underlying Fig. 3 is present in Supplementary Data 2. The three genomes sequenced in this study are available in DDBJ/ENA/Genbank repositories within BioProject PRJNA1053249 with BioSample accessions SAMN38850749, SAMN38850750 and SAMN38850751.

Code availability

Custom code, including key command lines for conducting BLAST searches, predicting the presence of coiled-coil domains, aligning sequences, reconstructing phylogenies, rooting phylogenies, assessing convergences, and implementing relaxed bayesian molecular clocks are available in a file called ‘CodesAndCommandLineUsed.sh’ in our Open Science Framework repository at the following https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8BXAR118.

References

Di Rienzi, S. C. et al. The human gut and groundwater harbor non-photosynthetic bacteria belonging to a new candidate phylum sibling to cyanobacteria. Elife 2, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.01102 (2013).

Soo, R. M. et al. An expanded genomic representation of the phylum cyanobacteria. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1031–1045 (2014).

Boden, J. S., Konhauser, K. O., Robbins, L. J. & Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. Timing the evolution of antioxidant enzymes in cyanobacteria. Nat. Commun. 12, 4742 (2021).

Fournier, G. P. et al. The Archean origin of oxygenic photosynthesis and extant cyanobacterial lineages. Proc. Biol. Sci. 288, 20210675 (2021).

Wang, C. L. et al. Archean to early Paleoproterozoic iron formations document a transition in iron oxidation mechanisms. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 343, 286–303 (2023).

Kump, L. R. The rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 451, 277–278 (2008).

Chen, G. et al. Reconstructing Earth’s atmospheric oxygenation history using machine learning. Nat. Commun. 13, 5862 (2022).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Evolution of the structure and impact of Earth’s biosphere. Nat. Rev. Earth Env. 2, 123–139 (2021).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Schirrmeister, B. E., de Vos, J. M., Antonelli, A. & Bagheri, H. C. Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1791–1796 (2013).

Schirrmeister, B. E., Gugger, M. & Donoghue, P. C. J. Cyanobacteria and the great oxidation event: evidence from genes and fossils. Palaeontology 58, 769–785 (2015).

Schirrmeister, B. E., Antonelli, A. & Bagheri, H. C. The origin of multicellularity in cyanobacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 45 (2011).

Blank, C. E. & Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. Timing of morphological and ecological innovations in the cyanobacteria - a key to understanding the rise in atmospheric oxygen. Geobiology 8, 1–23 (2010).

Hammerschmidt, K., Landan, G., Domingues Kümmel Tria, F., Alcorta, J. & Dagan, T. The order of trait emergence in the evolution of cyanobacterial multicellularity. Genome Biol. Evol. 13, https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evaa249 (2021).

Guéguen, N. & Maréchal, E. Origin of cyanobacterial thylakoids via a non-vesicular glycolipid phase transition and their impact on the Great Oxygenation Event. J. Exp. Bot. 73, 2721–2734 (2022).

Castenholz, R. W. Cyanobacteria. Oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, (eds, Garrity, G., Boone, D. R. & Castenholz, R. W.) 473–599 (Springer-Verlag, 2001).

Rippka, R., Deruelles, J., Waterbury, J. B., Herdman, M. & Stanier, R. Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111, 1–61 (1979).

Urrejola, C. et al. Loss of filamentous multicellularity in Cyanobacteria: the extremophile Gloeocapsopsis sp. Strain UTEX B3054 retained multicellular features at the genomic and behavioral levels. J. Bacteriol. 202, https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00514-19 (2020).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. Origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria. Sci. Rep. 5, 17418 (2015).

Flombaum, P. et al. Present and future global distributions of the marine cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9824–9829 (2013).

Herrero, A., Stavans, J. & Flores, E. The multicellular nature of filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 40, 831–854 (2016).

Nieves-Morión, M., Flores, E. Whitehouse, M. J., Thomen, A. & Foster, R. A. Single-cell measurements of fixation and intercellular exchange of C and N in the filaments of the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mbio. 12, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01314-21 (2021).

Wolk, C. P. Movement of carbon from vegetative cells to heterocysts in Anabaena cylindrica. J. Bacteriol. 96, 2138–2143 (1968).

Wolk, C. P., Austin, S. M., Bortins, J. & Galonsky, A. Autoradiographic localization of 13N after fixation of 13N-labeled nitrogen gas by a heterocyst-forming blue-green alga. J. Cell Biol. 61, 440–453 (1974).

Mariscal, V. Cell-cell joining proteins in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. In The Cell Biology of Cyanobacteria, (eds, Flores, E., Herrero, A.) 293–304 (Caister Academic Press, 2014).

Mullineaux, C. W. & Nürnberg, D. J. Tracing the path of a prokaryotic paracrine signal. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 1208–1212 (2014).

Flores, E., Herrero, A., Forchhammer, K. & Maldener, I. Septal junctions in filamentous heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Trends Microbiol. 24, 79–82 (2016).

Kieninger, A. K., Forchhammer, K. & Maldener, I. A nanopore array in the septal peptidoglycan hosts gated septal junctions for cell-cell communication in multicellular cyanobacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 309, 151303 (2019).

Weiss, G. L., Kieninger, A. K., Maldener, I., Forchhammer, K. & Pilhofer, M. Structure and function of a bacterial gap junction analog. Cell 178, 374–384.e315 (2019).

Merino-Puerto, V., Mariscal, V., Mullineaux, C. W., Herrero, A. & Flores, E. Fra proteins influencing filament integrity, diazotrophy and localization of septal protein SepJ in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 1159–1170 (2010).

Merino-Puerto, V. et al. FraC/FraD-dependent intercellular molecular exchange in the filaments of a heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium, Anabaena sp. Mol. Microbiol. 82, 87–98 (2011).

Arévalo, S. & Flores, E. Pentapeptide-repeat, cytoplasmic-membrane protein HglK influences the septal junctions in the heterocystous cyanobacterium Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 794–806 (2020).

Springstein, B. L. et al. A novel septal protein of multicellular heterocystous cyanobacteria is associated with the divisome. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 1140–1154 (2020).

Arévalo, S. & Flores, E. Heterocyst septa contain large nanopores that are influenced by the Fra proteins in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. Strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 203, https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00081-21 (2021).

Flores, E. et al. Septum-localized protein required for filament integrity and diazotrophy in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3884–3890 (2007).

Mullineaux, C. W. et al. Mechanism of intercellular molecular exchange in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 27, 1299–1308 (2008).

Mariscal, V., Herrero, A., Nenninger, A., Mullineaux, C. W. & Flores, E. Functional dissection of the three-domain SepJ protein joining the cells in cyanobacterial trichomes. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 1077–1088 (2011).

Mariscal, V., Nürnberg, D. J., Herrero, A., Mullineaux, C. W. & Flores, E. Overexpression of sepJ alters septal morphology and heterocyst pattern regulated by diffusible signals in Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 101, 968–981 (2016).

Omairi-Nasser, A., Mariscal, V., Austin, J. R. 2nd & Haselkorn, R. Requirement of Fra proteins for communication channels between cells in the filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, E4458–E4464 (2015).

Stucken, K. et al. The smallest known genomes of multicellular and toxic cyanobacteria: Comparison, minimal gene sets for linked traits and the evolutionary implications. PLoS One 5, e9235 (2010).

Springstein, B. L. et al. Identification and characterization of novel filament-forming proteins in cyanobacteria. Sci. Rep. 10, 1894 (2020).

Black, T. A., Cai, Y. & Wolk, C. P. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 77–84 (1993).

Kim, Y. et al. Structure of transcription factor HetR required for heterocyst differentiation in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 10109–10114 (2011).

Zhang, J. Y., Chen, W. L. & Zhang, C. C. hetR and patS, two genes necessary for heterocyst pattern formation, are widespread in filamentous non-heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Microbiology 155, 1418–1426 (2009).

Zhang, W. et al. A gene cluster that regulates both heterocyst differentiation and pattern formation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 1429–1443 (2007).

Elhai, J. & Khudyakov, I. Ancient association of cyanobacterial multicellularity with the regulator hetR and an RGSGR pentapeptide-containing protein (PatX). Mol. Microbiol. 110, 931–954 (2018).

Antonaru, L. A. & Nürnberg, D. J. Role of PatS and cell type on the heterocyst spacing pattern in a filamentous branching cyanobacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnx154 (2017).

Tomitani, A., Knoll, A. H., Cavanaugh, C. M. & Ohno, T. The evolutionary diversification of cyanobacteria: Molecular-phylogenetic and paleontological perspectives. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5442–5447 (2006).

Strunecký, O., Ivanova, A. P. & Mareš, J. An updated classification of cyanobacterial orders and families based on phylogenomic and polyphasic analysis. J. Phycol. 59, 12–51 (2023).

Enzingmuller-Bleyl, T. C. et al. On the trail of iron uptake in ancestral cyanobacteria on early Earth. Geobiology 20, 776–789 (2022).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Ridgwell, A. & Raven, J. A. A Neoproterozoic transition in the marine nitrogen cycle. Curr. Biol. 24, 652–657 (2014).

Chen, M. Y. et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into cyanobacterial evolution and habitat adaptation. ISME J. 15, 211–227 (2020).

Alcorta, J., Alarcón-Schumacher, T., Salgado, O. & Díez, B. Taxonomic novelty and distinctive genomic features of hot spring cyanobacteria. Front. Genet. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.568223 (2020).

Rockwell, N. C. & Lagarias, J. C. Cyanobacteriochromes from Gloeobacterales provide new insight into the diversification of cyanobacterial photoreceptors. J. Mol. Biol. 168313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2023.168313 (2023).

Velázquez-Suárez, C., Valladares, A., Luque, I. & Herrero, A. The role of Mre Factors and cell division in peptidoglycan growth in the multicellular cyanobacterium. Mbio 13, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.01165-22 (2022).

Nürnberg, D. J. et al. Branching and intercellular communication in the section V cyanobacterium Mastigocladus laminosus, a complex multicellular prokaryote. Mol. Microbiol. 91, 935–949 (2014).

Nürnberg, D. J. et al. Intercellular diffusion of a fluorescent sucrose analog via the septal junctions in a filamentous cyanobacterium. Mbio 6. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02109-14 (2015).

Arévalo, S. et al. Coexistence of communicating and non-communicating cells in the filamentous cyanobacterium. Msphere 6. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.01091-20 (2021).

Lehner, J. et al. Prokaryotic multicellularity: a nanopore array for bacterial cell communication. FASEB J. 27, 2293–2300 (2013).

Mandakovic, D. et al. CyDiv, a conserved and novel filamentous cyanobacterial cell division protein involved in septum localization. Front. Microbiol. 7, 94 (2016).

Donia, M. S. et al. Complex microbiome underlying secondary and primary metabolism in the tunicate-Prochloron symbiosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1423–E1432 (2011).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Bianchini, G., Di Cesare, A., Callieri, C. & Chrismas, N. A. M. Insights into the evolution of Picocyanobacteria and phycoerythrin genes (mpeBA and cpeBA). Front. Microbiol. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00045 (2019).

Boden, J. S., Zhong, J., Anderson, R. E. & Stüeken, E. E. Timing the evolution of phosphorus-cycling enzymes through geological time using phylogenomics. Nat. Commun. 15, 3703 (2024).

Bianchini, G., Hagemann, M. & Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. Stochastic character mapping, bayesian model selection, and biosynthetic pathways shed new light on the evolution of habitat preference in cyanobacteria. Syst. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syae025 (2024).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Raven, J. A., Pisani, D. & Knoll, A. H. Early photosynthetic eukaryotes inhabited low-salinity habitats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7737–E7745 (2017).

Tice, M. M., Thornton, D. C. O., Pope, M. C., Olszewski, T. D. & Gong, J. Archean microbial mat communities. Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 39, 297–319 (2011).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Hayes, P. K. & Blank, C. E. Morphological and habitat evolution in the cyanobacteria using a compartmentalization approach. Geobiology 3, 145–165 (2005).

Bjerrum, C. J. & Canfield, D. E. Ocean productivity before about 1.9 Gyr ago limited by phosphorus adsorption onto iron oxides. Nature 417, 159–162 (2002).

Konhauser, K. O., Lalonde, S. V., Amskold, L. & Holland, H. D. Was there really an Archean phosphate crisis? Science 315, 1234 (2007).

Ozaki, K., Thompson, K. J., Simister, R. L., Crowe, S. A. & Reinhard, C. T. Anoxygenic photosynthesis and the delayed oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 10, 3026 (2019).

Schad, M., Konhauser, K. O., Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Kappler, A. & Bryce, C. How did the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis influence the temporal and spatial development of the microbial iron cycle on ancient earth? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 140, 154–166 (2019).

Garcia-Pichel, F. et al. Timing the evolutionary advent of cyanobacteria and the later Great Oxidation Event using gene phylogenies of a sunscreen. Mbio. 10, https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00561-19 (2019).

Zheng, Z. et al. An amidase is required for proper intercellular communication in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1405–E1412 (2017).

Khudyakov, I., Gladkov, G. & Elhai, J. Inactivation of three RG(S/T)GR pentapeptide-containing negative regulators of HetR results in lethal differentiation of PCC 7120. Life 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/life10120326 (2020).

Arbel-Goren, R. et al. Robust, coherent, and synchronized circadian clock-controlled oscillations along filaments. Elife 10. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.64348 (2021).

Shih, P. M. et al. Improving the coverage of the Cyanobacterial phylum using diversity-driven genome sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1053–1058 (2013).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–591 (2017).

Trifinopoulos, J., Nguyen, L. T., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W232–W235 (2016).

Lopez-Maury, L., Florencio, F. J. & Reyes, J. C. Arsenic sensing and resistance system in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5363–5371 (2003).

Hoang, D. T. C. O., Haeseler, A. V., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2017).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 725–731 (2017).

Black, K., Buikema, W. J. & Haselkorn, R. The hglK gene is required for localization of heterocyst-specific glycolipids in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 177, 6440–6448 (1995).

Escudero, L., Mariscal, V. & Flores, E. Functional dependence between septal protein SepJ from Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 and an amino acid ABC-type uptake transporter. J. Bacteriol. 197, 2721–2730 (2015).

Lupas, A., Van Dyke, M. & Stock, J. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252, 1162–1164 (1991).

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 (2001).

Ronquist, F. et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542 (2012).

Lartillot, N., Lepage, T. & Blanquart, S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics 25, 2286–2288 (2009).

Tria, F. D. K., Landan, G. & Dagan, T. Phylogenetic rooting using minimal ancestor deviation. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0193 (2017).

Bianchini, G. & Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. TreeViewer: flexible, modular software to visualise and manipulate phylogenetic trees. Ecol. Evol. 14, e10873 (2024).

Drummond, A. J., Ho, S. Y. W., Phillips, M. J. & Rambaut, A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLOS Biol. 4, 699–710 (2006).

Golubic, S. & Lee, S. J. Early Cyanobacterial fossil record: preservation, palaeoenvironments and identification. Eur. J. Phycol. 34, 339–348 (1999).

Sergeev, V. N., Gerasimenko, L. M. & Zavarzin, G. A. The Proterozoic history and present state of cyanobacteria. Microbiol 71, 623–637 (2002).

Golubic, S., Sergeev, V. N. & Knoll, A. H. Mesoproterozoic Archaeoellipsoides: akinetes of heterocystous cyanobacteria. Lethaia 28, 285–298 (1995).

Sims, A. P., Mann, D. G. & Medlin, L. K. Evolution of the diatoms: insights from fossil, biological and molecular data. Phycologia 45, 361–402 (2006).

Foster, R. A. et al. Nitrogen fixation and transfer in open ocean diatom-cyanobacterial symbioses. ISME J. 5, 1484–1493 (2011).

Cornejo-Castillo, F. M. et al. Cyanobacterial symbionts diverged in the late Cretaceous towards lineage-specific nitrogen fixation factories in single-celled phytoplankton. Nat. Commun. 7, 11071 (2016).

Bown, P. R. & Young, J. R. Techniques. In: Calcareous nannofossil biostratigraphy (ed.Bown, P. R.) 16–28 (Chapman and Hall, London, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4902-0_2.

Bekker, A. et al. Dating the rise of atmospheric oxygen. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac 68, A780–A780 (2004).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis half a billiion years before the Great Oxidation Event. Nat. Geosci. 7, 283–286 (2014).

Bosak, T., Knoll, A. H. & Petroff, A. P. The meaning of stromatolites. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 41, 21–44 (2013).

Hofmann, H. J. Precambrian microflora, Belcher Islands, Canada - significance and systematics. J. Paleontol. 50, 1040–1073 (1976).

Boden, J. S., Grego, M., Bolhuis, H. & Sanchez-Baracaldo, P. Draft genome sequences of three filamentous cyanobacteria isolated from brackish habitats. J. Genomics 9, 20–25 (2021).