Abstract

Osteoporosis is a complex skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD). Compared with classical epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone modifications, the participation of chromatin-remodeling complexes in osteoporosis remains less explored. To identify chromatin remodeling factors causally associated with bone mineral density (BMD), here we conducted a systematic analysis of 87 genes encoding components of four major chromatin-remodeling complexes using Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) analysis. Candidate chromatin-remodeling factors were further cross-referenced with publicly available skeletal phenotyping data from the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) database. Functional validation revealed that non-canonical BAF (ncBAF) subunit BRD9 is essential for osteoblast differentiation using both in vitro cell culture and in vivo zebrafish models. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) demonstrated that BRD9 orchestrates osteogenic differentiation by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. Mechanistically, the osteogenic master transcription factor Sp7 was identified as a direct transcriptional target of BRD9, whose expression is coordinately controlled through the synergistic interplay between BRD9 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling during osteogenesis. Collectively, this study established a comprehensive framework for identifying causal genes implicated in osteoporosis and elucidated the previously unrecognized regulatory role of BRD9 in osteogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a complex multifactorial skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and increased fracture risk1. Both genetic alternation and environmental stimuli, including diet, physical activity, and air pollution, collectively influence bone remodeling processes2,3. Epigenetic mechanisms mediate the interplay between genetic factors and environmental stimuli, playing a pivotal role in bone homeostasis4. DNA methylation and histone modifications have been extensively investigated in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis5,6. However, chromatin remodeling, another crucial epigenetic mechanism, has not received as much attention in this context. ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes regulate gene transcription by utilizing ATP hydrolysis to modify chromatin structure7. These complexes are classified into four major families: imitation switch (ISWI), chromodomain helicase DNA-binding (CHD), switch/sucrose non-fermentable (SWI/SNF), and INO808. Each chromatin remodeler processes epigenetic information via distinct mechanisms, yielding specific functional outcomes while maintaining genomic stability and plasticity. A comprehensive understanding of chromatin remodeling in osteoporosis could facilitate the development of innovative therapeutic strategies.

SWI/SNF complex is evolutionarily conserved across higher eukaryotes and exhibits dual functionality in transcriptional activation and repression9. This functional versatility stems, in part, from its capacity to assemble into distinct configurations through the incorporation of alternative subunits, resulting in three specialized complexes: the canonical BAF (cBAF), polybromo-associated BAF (PBAF), and non-canonical BAF (ncBAF)10. Notably, genes encoding SWI/SNF are frequently mutated or dysregulated in various diseases, for example, in approximately 25% of tumors and in various neurodevelopmental disorders11. Bone homeostasis is a dynamic process regulated by the coordinated activity of bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts12,13. Osteoporosis occurs when this balance is disrupted, leading to excessive bone resorption and increased fracture risk14. Previous work demonstrated that SWI/SNF complexes containing the BRG1 ATPase are necessary for osteogenic transcriptional activation and Runx2-mediated skeletal gene transcription15,16. However, a distinct subclass of SWI/SNF, dominated by the BRM ATPase, plays a repressor role in osteoblast differentiation and favors adipogenic lineage commitment17,18. Moreover, emerging evidence highlights significant functional heterogeneity not only among different chromatin remodeling complexes but also among individual subunits within the same complex, each exhibiting unique regulatory specificity19,20. Therefore, unbiased functional prioritization of chromatin remodeling complexes for their roles in bone homeostasis requires thorough investigation.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been utilized to investigate the genetic basis of osteoporosis21, identifying over 1100 genomic loci that contain single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with BMD22,23. However, elucidating the biological mechanisms underlying the identified causal variants remains a significant challenge for GWAS. To address this limitation, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying both cis-acting and trans-regulatory genetic elements that regulate the expression of critical genes correlated with traits of interest24. Notably, bone tissue-specific eQTL studies have revealed genetic variants influencing the expression of critical genes in bone remodeling25. Building on the concept of Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis, Zhu et al. further developed a method called summary data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR), which integrates summary-level data from independent GWAS with eQTL data to prioritize causal genes26. Additionally, the COLOC method employs Bayesian analysis to detect the co-localization of GWAS signals with eQTL effects at known risk loci27. Given the evolutionary conservation of skeletal development, these computational approaches will gain biological relevance through cross-species functional validation. Large-scale phenotyping by the International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) has identified about 200 genes causing both BMD alterations and skeletal abnormalities through systematic analysis of 3,823 mutant mouse strains28. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) model shares many skeletal features and ossification mechanisms with mammals29, including evolutionarily conserved osteogenic regulators such as runx2a and osterix (sp7)30,31. Therefore, to develop an integrative approach combining statistical genetics with cross-species experimental validation will provide a robust framework for unraveling the pathogenesis of osteoporosis, from genetic association to molecular mechanism.

In this study, we first integrated an innovative SMR analysis with skeletal phenotyping data from the IMPC and identified chromatin remodeler BRD9 as a potential regulator of skeletal homeostasis. Next, we conducted functional validation with in vitro cell culture and in vivo zebrafish models, and demonstrated that BRD9 is indispensable for osteoblast differentiation through modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. Mechanistically, BRD9 cooperates with β-catenin to control the transcription of osteogenic master transcription factor Sp7. Collectively, this study provides a scalable cross-species integrative approach to prioritize and identify causal genes associated with osteoporosis, and highlight the epigenetic regulation contributing to skeletal disorders.

Results

Integrative analysis to prioritize chromatin-remodeling factors associated with BMD

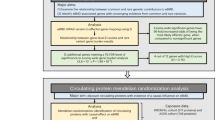

To identify chromatin remodelers associated with BMD, we developed a stepwise analytical framework that integrates SMR analysis with phenotypic screening of the IMPC database, and validated the functional roles of candidate genes using mouse osteoblast cells (in vitro) and zebrafish models (in vivo) (Fig. 1A). First, we systematically analyzed chromatin-remodeling complex subunits from the EpiFactors database32, focusing on four major complexes: ISWI (n = 12), CHD (n = 20), SWI/SNF (n = 26) and INO80 (n = 29) complex (Fig. 1B). To prioritize chromatin-remodelers associated with BMD, SMR was conducted through integrating the largest available BMD GWAS and fibroblasts eQTL study. A total of 14 chromatin-remodeling genes showed significant associations with BMD (PSMR < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2). Among them, seven genes (BRD9, SMARCB1, CFDP1, YEATS4, TFPT, RVB1, and SWC5) passed heterogeneity in dependent instruments tests (PHEIDI > 0.05), indicating minimal heterogeneity in identified variants. Notably, most prioritized genes, such as BRD9, SMARCB1, YEATS4, TFPT, RVB1, and SWC5, were less reported to be associated with BMD or osteoporosis. Intriguingly, we observed divergent effects between ncBAF subunit BRD9 and cBAF subunit SMARCB1, where increased BRD9 expression (β = 0.021, PSMR = 0.040) was associated with higher BMD while SMARCB1 expression (β = -0.021, PSMR = 0.020) was associated with a lower BMD. This opposing pattern aligns with the emerging notion that distinct chromatin remodeling complexes, and even different subunits within the same complex, exhibit specialized functional roles in skeletal biology. Notably, we identified one independent association signal (SNP rs116511572) for eBMD located approximately 500 bp upstream of the BRD9 gene, and cis-eQTL results showed that the SNP rs116511572 allele was significantly associated with expression of BRD9 (P = 4.364×10-20) (Fig. 1C, Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, fine-mapping analysis indicated that rs1697950 and rs60299439 were potential independent causal SNPs influencing eBMD within BRD9 locus (Supplementary Data 1).

A Schematic diagram of stepwise approach to identify chromatin-remodeling factors associated with BMD. SMR analysis was conducted through integrating human BMD GWAS datasets with fibroblasts eQTLs datasets, and cross-referenced with skeletal phenotype from IMPC. Functional roles of candidate genes were validated in mouse osteoblast cell line and zebrafish models (Created in BioRender. Wang, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/d9kgsgi). B Protein-protein interaction networks of four types of chromatin-remodeling complexes, including ISWI, CHD, SWI/SNF and INO80 complex. The relationship for protein-protein interaction was obtained from STRING database and constructed using Cytoscape software. The nodes represent genes, and the edges represent links between genes. C Prioritizing genes at a GWAS locus using SMR analysis. Representative visualization of the Brd9 locus associated with BMD at the GWAS locus. In GWAS layer (top), maroon denotes probes surpassing the SMR threshold (PSMR < 0.05), while navy blue indicates non-significant associations. Solid rhombuses represent probes passing the HEIDI threshold (PHEIDI > 0.05), and hollow rhombuses mark those failing HEIDI. In eQTL layers (middle and bottom), maroon highlights probes meeting the SMR threshold, displaying eQTL P-values for SNPs within BRD9 and RP11-43F13.3. Genes highlighted in red (Brd9 and RP11-43F13.3) passed both the SMR and HEIDI criteria, indicating colocalization of GWAS signals with expression quantitative trait loci. D Box-plot showing BMC/Body weight ratio of male WT (n = 94), male HET (n = 12), female WT (n = 100), and female HET (n = 15) mice according to the IMPC database. Data points represent individual mice, grouped by genotype and sex. WT, wild type, HET, heterozygotes. Data are presented as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, ***P < 0.001.

To further validate the results of human genetic variation mediated chromatin-remodeling gene expression on BMD, we performed cross-species validation using the IMPC database, in which 1246 gene mutants (14.7% of total) exhibited skeletal abnormalities, including altered bone structure, BMD, and bone mineral content (BMC), with 908 homozygotes, 321 heterozygotes, and 17 hemizygotes identified. Next, we performed intersectional analysis between these skeletal phenotype-associated murine genes and human SMR genetic data, and identified 2 overlapping genes, Brd9 and Smarcb1 (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, murine genetic models recapitulated the opposing skeletal effects between Brd9 and Smarcb1 observed in human genetic studies (Supplementary Table 3). Heterozygous Brd9 mutations caused significant reductions in late-adult bone mineral content, while Smarcb1 heterozygous mutations displayed elevated BMD (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Table 3). Although recent work has demonstrated that BRD9 deficiency enhances osteoclast lineage commitment and bone resorption33, its specific functions in osteoblast-mediated bone formation remain undefined. Therefore, our following functional validation focused on the role of BRD9 in osteogenesis utilizing both in vitro and in vivo approaches.

Brd9 is indispensable for in vitro osteoblast differentiation

To elucidate the functional roles of Brd9 in osteoblastogenesis, we first analyzed its expression changes during osteogenic differentiation of mouse osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. The mRNA levels of Brd9 were gradually upregulated in a time-dependent manner, suggesting that Brd9 may participate in osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 2A). Next, we verified the roles of Brd9 in osteogenesis with a commercial chemical inhibitor, I-BRD9. A range of I-BRD9 concentrations was tested, and BRD9 expression was markedly reduced at 10 μM without any obvious cell death (Fig. S1A and B). In line with the concentration previously used for I-BRD9 in mESCs34, we utilized 10 μM for the subsequent experiments. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining in MC3T3-E1 cells showed that the osteogenic activity was significantly decreased following I-BRD9 treatment, compared with controls (Fig. 2B). RT-qPCR analysis further demonstrated that the transcription of osteoblastic specific genes, including Alkaline phosphatase (Alpl), Collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a), Osteocalcin (Ocn), Osteopontin (Opn), and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), was decreased in MC3T3-E1 cells cultured in normal medium under I-BRD9 treatment (Fig. 2C). Consistently, I-BRD9 treatment downregulated the protein levels of ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN (Fig. 2D). Additionally, we investigated the roles of BRD9 during osteogenic differentiation and found the addition of I-BRD9 significantly suppressed the upregulation of key osteogenic markers, including Alpl, Col1a, Ocn, Opn, and Runx2, following 7 and 10 days of culture in osteogenic differentiation medium (Fig. 2E). Consistently, overexpression of Brd9 induced a modest upregulation of osteogenic markers transcription, including Alpl, Col1a, Ocn, and Runx2 (Fig. S1C). Exogenous BRD9 also upregulated the protein levels of ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN (Fig. S1D and E). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that BRD9 is indispensable for osteoblast differentiation in vitro.

A Temporal expression profile of Brd9 mRNA in MC3T3-E1 cells during osteoblastic differentiation, as determined by RT-qPCR analysis at specified time points. B ALP staining of MC3T3-E1 cells following 7-day osteogenic induction with simultaneous I-BRD9 treatment. Scale bar = 100 um. C Osteogenic marker gene expression by RT-qPCR in control versus I-BRD9 treated MC3T3-E1 cells under basal culture conditions. D Protein levels of osteogenic markers, such as ALPL, RUNX2 and OCN, upon DMSO and I-BRD9 treatment in MC3T3-E1 cells. GAPDH was used as the internal control. Molecular weight is indicated on the right side (kDa). E Temporal expression patterns of key osteogenic markers Alpl, Col1a, Ocn, Opn, and Runx2 in I-BRD9 treated MC3T3-E1 cells during 7- and 10-day differentiation periods. F Alizarin red staining showing the dorsal views of wild type (n = 15) and brd9 knockdown (n = 11) zebrafish larvae at 144 hpf. op, orbitosphenoid, cl, cleithrum, pt, pharyngeal teeth, and n, vertebral column. Scale bar = 0.25 mm. G Quantification of alizarin red staining area in (F). H The mRNA expression of runx2a, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b in zebrafish larvae at 96 hpf with control or brd9 morpholino injection, as measured by RT-qPCR. GAPDH and β-Actin were used as internal reference genes for RT-qPCR in MC3T3-E1 cells and zebrafish, respectively. Replicates are shown as dots. RT-qPCR data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Inhibition of BRD9 results in bone developmental defects in zebrafish

Given that BRD9 protein is highly conserved across various species (Fig. S2), we further investigated the function of brd9 on bone development in zebrafish, a commonly used vertebrate model organism for skeletal research. brd9 was knocked down using morpholino oligonucleotides (MO). The efficiency of brd9 MO was determined by an EGFP reporter construct pCS2+brd9: EGFP. We found that both 2 and 4 ng of brd9 MO completely abolished brd9: EGFP fluorescent intensity (Fig. S3A), and 2 ng brd9 MO was used in the following experiments. Alizarin red staining revealed that brd9 knockdown larvae exhibited defects in bone development, compared to wild-type larvae at 144 hours postfertilization (hpf). The developmental defects were most pronounced in the orbitosphenoid (op), cleithrum (cl), pharyngeal teeth (pt), and the vertebral column (n) (Fig. 2F). Quantitative analysis demonstrated significant differences in the ossification area between wild-type counterparts and brd9 knockdown larvae (Fig. 2G). We further analyzed expression of bone development-related genes in brd9 knockdown zebrafish larvae at 96 hpf. At this developmental stage, key bone development-related genes highly expressed in zebrafish larvae include Runt-related transcription factor 2a (runx2a), Alkaline phosphatase (alpl), Bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (bglap, zebrafish orthologous of mammalian Ocn), Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (spp1, zebrafish orthologous of mammalian Opn), Collagen type I alpha 1a chain (col1a1a), and Collagen type I alpha 1b chain (col1a1b). RT-qPCR results revealed a significant decrease in the mRNA levels of runx2a, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b in brd9 knockdown zebrafish larvae, compared to wild-type controls (Fig. 2H). Consistently, brd9 knockdown by MO led to a marked reduction in ALPL protein expression (Fig. S3B), indicating that BRD9 ablation results in widespread skeletal developmental defects in vivo.

Transcriptomic analysis of mouse osteoblast cells following BRD9 inhibition

To understand the mechanism by which BRD9 regulates osteoblast differentiation, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of MC3T3-E1 cells treated with I-BRD9 under both normal and osteogenic differentiation conditions. Under normal culture conditions, I-BRD9 treatment resulted in 74 downregulated genes and 56 upregulated genes, compared with the control group (Fold change>1.5 and Padj < 0.05) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Data 2). Gene ontology (GO) analysis demonstrated that these differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were predominantly associated with osteogenic processes, such as ossification, bone mineralization, and biomineral tissue development (Fig. 3B). Under osteogenic differentiation conditions, I-BRD9 treatment elicited more pronounced transcriptional alterations, with 456 downregulated and 357 upregulated genes identified (Fold change>1.5 and Padj < 0.05) (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Data 2). GO analysis similarly highlighted ossification as the most significantly enriched biological process among DEGs in differentiating cells (Fig. 3E). Notably, KEGG pathway analysis identified the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway as the top enriched pathway under both normal and differentiation conditions (Fig. 3C, F). Comparative analysis of DEGs between normal and differentiation conditions revealed 89 overlapping genes (Fig. 3G, H), which showed enrichment in key osteogenic processes, including skeletal development, bone morphogenesis, bone mineralization, osteoblast differentiation, and regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Fig. 3I). A protein-protein interaction network, constructed using the STRING database, highlighted Sp7/Osterix as a central node interacting with multiple Wnt signaling components (Wnt10b, Prickle1, and Tcf7) and osteogenic factors (Alpl, Ibsp, and Tnfrsf11b) (Fig. 3J). The expression of three representative genes, Sp7, Alpl, and Ibsp, was significantly reduced upon I-BRD9 treatment under normal conditions. Moreover, their transcriptional induction by the differentiation medium was also markedly suppressed (Fig. 3K–M). Collectively, these findings suggest that BRD9 likely coordinates osteoblast differentiation through modulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and regulation of osteogenic transcription factors.

A Volcano plot analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in MC3T3-E1 cells upon I-BRD9 treatment versus control under normal culture condition. X-axis: log₂(Fold change); Y-axis: -log₁₀(FDR adjusted P value). Red and blue points indicate significantly upregulated and downregulated genes (FDR < 0.05, Fold change>1.5), respectively. B GO enrichment analysis of DEGs from I-BRD9-treated cells under normal conditions. Dot size corresponds to gene ratio (number of enriched genes/total DEGs) and color intensity represents -log₁₀(adjusted P-value). Top 10 significant terms shown. C KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs from I-BRD9 treated cells under normal conditions. The visualization parameters are consistent with that in (B), with red color gradient indicating statistical significance. D Differential gene expression profile of I-BRD9 treated cells under differentiation conditions, presented as volcano plot with identical parameters to A. E GO term enrichment and F KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs under differentiation conditions, following the same visualization scheme as B and C respectively. G Venn diagram comparing DEG overlaps between normal and differentiation conditions for I-BRD9 treatment versus control groups. H Hierarchical clustering heatmap illustrating overlapping DEGs in MC3T3-E1 cells under normal medium (NM) versus osteogenic differentiation-conditioned medium (CM). I GO enrichment analysis of consensus DEGs identified in panel H, based on log₂(Fold change) under differentiation conditions. J Protein-protein interaction network of overlapping DEGs constructed using STRING database interactions and visualized with Cytoscape. The nodes represent genes, and the edges represent links between genes. K–M Violin plots demonstrate expression patterns of key osteogenic markers Sp7, Alpl, and Ibsp in RNA-seq data from I-BRD9-treated cells under NM versus CM conditions.

Utility in vitro and in vivo models to validate the involvement of BRD9 in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling

We then validated the regulation of BRD9 on canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in MC3T3-E1 cells. I-BRD9 treatment significantly reduced mRNA levels of Wnt target genes, including Ccnd1, Lef1, Myc, and Tcf7 by RT-qPCR (Fig. 4A) and decreased protein levels of transcriptional coactivator β-catenin by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B, C). To further verify this regulation, we transfected HEK293T cells with Topflash luciferase reporter, which contains a minimal promoter coupled to TCF-binding sites upstream of firefly luciferase gene. As shown in Fig. 4D, β-catenin induced Topflash luciferase activity was suppressed by I-BRD9 treatment. Conversely, BRD9 overexpression enhanced Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity, as evidenced by the upregulation of Wnt target genes (Fig. 4E), elevated β-catenin protein levels in MC3T3-E1 cells (Fig. 4F, G), and increased Topflash reporter activity in HEK293T cells (Fig. 4H). Taken together, our in vitro findings demonstrate that BRD9 plays a critical role in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity.

A Relative mRNA levels of Ccnd1, Lef1, Myc, and Tcf7 in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with I-BRD9 under normal culture conditions, analyzed by RT-qPCR. B Western blot analysis of β-CATENIN protein levels in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with I-BRD9. TUBULIN was used as the internal control. Molecular weight is indicated on the right side (kDa). C Quantification of β-CATENIN band intensity from B. D The activities of Topflash luciferase reporter in HEK293T treated with I-BRD9, with or without β-catenin overexpression. E The mRNA expressions of Ccnd1, Lef1, Myc, and Tcf7 in Brd9 overexpressing MC3T3-E1 cells. F The protein levels of β-CATENIN in MC3T3-E1 cells with Brd9 overexpression under normal culture conditions. TUBULIN was used as the internal control. Molecular weight is indicated on the right side (kDa). G Quantification of β-CATENIN band intensity from F. H Topflash luciferase reporter activity in Brd9 overexpressing MC3T3-E1 cells. I The mRNA expressions of sp5l, ccnd1 and axin2 in zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf with BRD9 knockdown using morpholino oligonucleotide (MO). J The mRNA expression of sp5l, ccnd1, and axin2 in zebrafish larvae upon I-BRD9 or XAV-939 treatment for three days. K Alizarin red staining of mineralized tissue in zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf upon DMSO (n = 15), I-BRD9 (n = 14) and XAV-939 (n = 12) treatment. Scale bar = 0.25 mm. (L) Quantification of alizarin red staining area from K. M mRNA levels of osteogenic markers (runx2a, sp7, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b) in zebrafish larvae upon I-BRD9 or XAV-939 treatment for three days. GAPDH and β-actin were used as internal reference genes for RT-qPCR in MC3T3-E1 cells and zebrafish, respectively. Replicates shown as dots. Luciferase and RT-qPCR data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Next, we want to identify whether BRD9 executes the similar regulation on Wnt/β-catenin signaling in vivo. First, knockdown of brd9 in zebrafish significantly reduced the transcription of Wnt/β-catenin target genes, including sp5l, ccnd1, and axin2 (Fig. 4I). To further confirm these findings, zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf were treated with I-BRD9 or the canonical Wnt inhibitor XAV-939 for three days. 20 μM of I-BRD9 and 10 μM of XAV-939 were selected as the final concentration according to the quantification of Alizarin Red dyeing area (Fig. S3C, D). Consistent with the genetic approach, pharmacological inhibition of BRD9 downregulated Wnt/β-catenin target genes (sp5l, ccnd1, and axin2) in a pattern resembling that observed with XAV-939 (Fig. 4J). Furthermore, phenotypic analysis revealed that zebrafish larvae with brd9 knockdown exhibited morphological abnormalities consistent with impaired Wnt/β-catenin signaling35,36 (Fig. S3E, F), including craniofacial defects observed by Alizarin Red staining. Compared with DMSO treated group, zebrafish larvae treated with XAV-939 exhibited developmental defects in key skeletal structures, parasphenoid (ps), orbitosphenoid (op), cleithrum (cl), and pharyngeal teeth (pt) (Fig. 4K, L), resembling the phenotypes observed in brd9 knockdown and I-BRD9 treated groups (Figs. 2F, 4K, L). At the molecular level, both XAV-939 and I-BRD9 treatments significantly decreased the expression of osteogenic markers, such as runx2a, sp7, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b, compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 4M). Consistently, the protein levels of ALPL were significantly decreased by XAV-939 and I-BRD9 treatments (Fig. S3G, H). These observations support the hypothesis that BRD9 regulates bone development likely through modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The osteogenic transcription factor Sp7 serves as a direct downstream target of BRD9 in the regulation of osteoblastogenesis

SP7, a transcription factor containing three zinc finger motifs and belonging to the speckled protein (SP) family, cooperates with Wnt signaling and RUNX2 to regulate osteoblast differentiation37. Our previous findings demonstrated that pharmacological BRD9 inhibition significantly downregulated osteogenic markers, such as sp7, runx2, ocn and opn, while suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity in both in vitro and in vivo models (Figs. 2–4). To elucidate the temporal transcriptional dynamics underlying these changes, we performed time-course assays with comparative kinetic analysis of key regulatory genes. RT-qPCR experiments were performed to examine the transcriptional changes of osteogenic transcription factors (Runx2 and Sp7), osteogenic markers (Alpl, Col1a, Ocn, and Opn) and Wnt/β-catenin signaling components (Apc, Gsk3β, Myc, Ccnd1, and Tcf7), at multiple time points following I-BRD9 inhibition (Figs. 5A, B and S4). Strikingly, Sp7 transcription exhibited rapid and pronounced suppression, with significant downregulation detectable within 1.5-2 hours post I-BRD9 administration (Fig. 5B, C). Exogenous Brd9 expression upregulates Sp7 transcription (Fig. 5D). Consistently, SP7 protein levels were decreased by I-BRD9 while upregulated by exogeneous BRD9 (Fig. 5E), suggesting that Sp7 may function as a direct downstream target of BRD9 during osteoblastogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we cloned different regions, encompassing a 3000 bp promoter region upstream of the Sp7 TSS into luciferase reporter vectors. The proximal promoter region (-1000 to +1) demonstrated the highest activity, indicating that this region likely harbors the core promoter elements essential for Sp7 transcription (Fig. 5F). As anticipated, BRD9 inhibition significantly reduced, while BRD9 overexpression enhanced, the activity of this proximal promoter luciferase reporter (Fig. 5G, H). Furthermore, ChIP-qPCR experiments demonstrated that BRD9 inhibition impaired the enrichment of BRD9 on the Sp7 proximal promoter (Fig. 5I). Importantly, the downregulation of key osteoblastogenic genes, including Ocn, Runx2, and Col1a, was partially rescued by the ectopic expression of Sp7 (Fig. 5J–M), suggesting that BRD9 regulates osteoblastogenesis through direct transcriptional control of Sp7 expression.

A Relative mRNA levels of osteogenic markers (Alpl, Col1a, Ocn, Opn and Runx2) and Wnt/β-Catenin pathway components (Apc, Gsk3, Myc, Ccnd1 and Tcf7) in MC3T3-E1 treated with I-BRD9 for 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h and 28 h under normal culture conditions, as measured by RT-qPCR. B The change of mRNA levels of Sp7 in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with I-BRD9 for 0-28 h under normal culture conditions. C The change of Sp7 expression in MC3T3-E1 cells treated with I-BRD9 for 0–2 h. D Sp7 transcriptional levels in Brd9 overexpressing MC3T3-E1 cells. E The protein levels of SP7 in I-BRD9 treated and BRD9 overexpressing MC3T3-E1 cells. Molecular weight is indicated on the right side (kDa). GAPDH was used as the internal control. F Schematic of Sp7 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs (−3000~−2000, −2000~−1000, and −1000~+ 1) and their basal luciferase activities in HEK293T cells. G Luciferase activity of the proximal Sp7 promoter (−1000~+1) in HEK293T cells treated with I-BRD9. H Sp7 promoter (−1000~+1) activity in Brd9 overexpressing HEK293T cells. I ChIP-qPCR showing reduced BRD9 binding to Sp7 promoter after I-BRD9 treatment. J–M Rescue of osteogenic marker expression Ocn, Runx2 and Col1a by Sp7 overexpression in I-BRD9 treated MC3T3-E1 cells. N Co-immunoprecipitation with BRD9 or IgG antibodies, demonstrating BRD9-β-CATENIN interaction in MC3T3-E1 cells. Molecular weight is indicated on the right side (kDa). O ChIP-qPCR analysis showing reduced β-CATENIN binding to Sp7 promoter after I-BRD9 treatment. P Luciferase activity of the Sp7 promoter in HEK293T cells treated with I-BRD9, with or without β-catΔN (N-terminally truncated β-catenin) overexpression. GAPDH was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. Replicates shown as dots. Luciferase and RT-qPCR data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

BRD9 collaborates with β-catenin to regulate Sp7 transcription

Several osteogenesis-related transcription factors, including Runx2 and Sp7, have been identified as direct targets of Wnt/β-catenin signaling38. Given the observation that both Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Sp7 are regulated by BRD9, we hypothesized that BRD9 might cooperate with β-catenin to regulate Sp7 transcription. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a series of experiments. First, co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays revealed a physical interaction between endogenous BRD9 and β-catenin proteins (Fig. 5N). Furthermore, ChIP-qPCR analysis demonstrated that BRD9 inhibition impaired β-catenin binding on the Sp7 proximal promoter (Fig. 5O). Consistent with previous report39, we observed the activity of Sp7 proximal promoter luciferase was markedly elevated by the constitutive form of β-catenin (β-catΔN), while this induction was abolished upon BRD9 inhibition (Fig. 5P). Notably, the impaired promoter activity caused by BRD9 inhibition could be rescued through β-catΔN overexpression (Fig. 5P). Taken together, these in vitro findings demonstrate that BRD9 participates in β-catenin-mediated regulation of Sp7 transcription.

To further validate these findings in a physiological context, we employed a transgenic zebrafish model Tg (sp7: EGFP) where EGFP was introduced downstream of the regulatory regions of sp7 to faithfully report the endogenous sp7 expression40. I-BRD9 led to a decreased intensity and areas of EGFP-positive cells (Fig. 6A, B, S5A). Consistently, brd9 knockdown via Morpholino led to significant decrease of sp7 transcription (Fig. S5B). The severe bone developmental defects caused by brd9 morphants were rescued by overexpression of either Sp7 or β-catΔN (Fig. 6C, D). Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that the downregulation of osteogenic markers, runx2a, sp7, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b, was restored to control levels through either sp7 or β-catΔN overexpression in brd9 morphants (Figs. 6E and S5C). Collectively, BRD9 orchestrates bone development through β-catenin-dependent regulation of sp7 expression, revealing functional collaboration between BRD9 and β-catenin in skeletal development.

(A) Effects of I-BRD9 and XAV-939 on opercle (op) and posterior branchiostegal ray (brsp) development in Tg(sp7:EGFP) zebrafish at 144 hpf. Tg(sp7:EGFP) zebrafish treated with DMSO (n = 10), 20 μM I-BRD9 (n = 10) or 10 μM XAV-939 (n = 10) from 72 hpf through 144 hpf. Scale bar = 50 μm. B Quantification of fluorescence intensity of opercle. C Dorsal view alizarin red staining of mineralized tissues in wild type (Control) (n = 14), brd9 morpholino knockdown (brd9 MO) (n = 13), brd9 MO with Sp7 mRNA (brd9 MO+sp7) (n = 18), and brd9 MO with β-catΔN mRNA (brd9 MO+β-catΔN) (n = 18) zebrafish larvae. Scale bar = 0.25 mm. D Quantitative measurement of alizarin red-stained area from C. E RT-qPCR analysis of osteogenic marker genes runx2a, sp7, alpl, bglap, spp1, col1a1a, and col1a1b expression in experimental groups. β-Actin was used as an internal control. F Proposed mechanistic model of the cooperation of BRD9 and β-Catenin in modulating Sp7 expression (Created in BioRender. Wang, L. (2025) https://BioRender.com/d9kgsgi). Under physiological conditions, BRD9 facilitates β-Catenin mediated transcriptional activation of Sp7, promoting osteogenic differentiation and bone mineralization. In the absence of BRD9, β-Catenin binding on Sp7 promoter was decreased, leading to reduced osteogenesis and decreased bone density. Replicates shown as dots. RT-qPCR data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, and statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Human genetics has emerged as a pivotal tool in the process of drug discovery, with the therapeutic targets supported by strong human genetic evidence demonstrating twice the success rate of those lacking such validation41. While GWAS of complex traits typically identifies variants with modest effects, these findings can nevertheless pinpoint highly tractable therapeutic targets. In comparison, Mendelian randomization approaches show more predictive value for drug target validation, which employs SNPs as instrumental variables to assess the causal relationship between gene expression (exposure) and phenotypic outcomes. To identify chromatin remodelers with causal association with BMD, we applied the SMR approach by integrating eBMD GWAS summary statistics with fibroblasts eQTL data. eQTL effects are known to be tissue-specific, while the sample size of eQTL investigations in human osteoblasts is relatively limited ( < 100 samples). Fibroblasts eQTL data (>450 samples) was selected as a proxy for osteoblast regulation based on several lines of evidence: First, fibroblasts and mesenchymal stromal/stem cells are phenotypically indistinguishable and they share similar lineage characteristics with osteoblasts42. Second, these cell types exhibit functional conservation, with bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) induced osteogenic differentiation also conserved in NIH3T3 fibroblasts43. Moreover, fibroblasts can be directly reprogramed into functional osteoblasts via RXOL cocktail (Runx2, Osx, OCT3/4, and L-MYC)44. Utilizing this methodology, we identified 14 chromatin remodeler genes associated with BMD meeting genome-wide significance PSMR < 0.05. Subsequent HEIDI testing refined this list to 7 genes with pleiotropy-resistant associations PHEIDI > 0.05. We applied a P-value threshold of 0.05 for both the SMR and HEIDI tests without correcting for multiple testing. This conservative approach was chosen to retain a broader set of potentially causal genes. Notably, recent studies have shown that relationships below the corrected P-value cutoff, known as sub-thresholds, can be biologically significant45. To further validate our findings, we cross-referenced the SMR statistics with the IMPC database, and revealed SWI/SNF subunit Brd9 as a promising BMD-associated candidate. This integrative approach mirrors a recent study that combined human GWAS data with mouse genetic data to identify Sestrin1 as a cholesterol regulator46. Together, these findings underscore the utility of integrating human genetic data with model organism phenotyping to uncover the genetic mechanisms underlying complex diseases.

In the past decades, multiple studies have revealed the epigenetic changes associated with aging, including altered DNA methylation patterns, decreased core histones, and abnormalities in noncoding RNAs, which ultimately affect the expression of downstream signaling or critical factors contributing to osteoporosis development47. Among epigenetic regulators, chromatin remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF play crucial roles in controlling gene accessibility9. BRD9, a unique subunit of ncBAF, has been reported to orchestrate lineage-specific and stimulus-induced gene expression in diverse biological processes, including cancer, cell pluripotency, inflammation, and antiviral responses, in a tissue specific manner48. Recently, Du et al demonstrated that Brd9 deficiency in myeloid lineage enhances osteoclast lineage commitment and bone resorption33. These findings revealed that BRD9 interacts with the transcription factor FOXP1 and promotes Stat1 expression by directly binding to its promoter, thereby activating IFN-β signaling, while osteoblast-mediated bone formation remained unaffected by osteoclast-specific deletion of BRD9. Considering the potential cell-autonomous roles of BRD9 in osteogenesis, we systematically integrated human SMR analysis with mouse IMPC database, and performed functional validation utilizing both in vitro osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 line and in vivo zebrafish models. Our SMR analysis identified a causal SNP (rs116511572) associated with Brd9 expression, contributing to BMD variation in humans. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that BRD9 inhibition impairs osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Based on previously published findings and the current study, we propose that BRD9 is essential for bone homeostasis, coordinating both osteoblast-mediated bone formation and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. This dual role may explain why even a partial loss of BRD9 in heterozygous knockout mice is sufficient to cause significantly lower BMD. Interestingly, our analysis revealed that SMARCB1 exhibits functions opposite to that of BRD9, as indicated by SMR analysis and mouse IMPC database. This finding contrasts with previous reports demonstrating SMARCB1 is required for the osteogenic differentiation potential during replicative senescence of rat mesenchymal stromal cells49. Several factors may account for this discrepancy, including differences in experimental models, species-specific effects, or context-dependent mechanisms. This intriguing observation warrants further functional investigation in the future.

Runx2, Sp7, and canonical Wnt signaling collaboratively regulate the differentiation of preosteoblasts into mature osteoblasts. Runx2 induces the expression of Sp7, and Runx2+ osteoprogenitors become Runx2 + Sp7+ preosteoblasts, characterized by low baseline expression of Col1a1. Subsequent activation of Runx2, Sp7, and canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling is essential for terminal osteoblast maturation, driving the upregulation of Col1a1 and Ocn expression50. As the master regulator of osteoblastogenesis, Sp7 requires precise spatiotemporal activation mediated by transcription factors, signaling cascades, and chromatin remodeling complexes. For example, RUNX2 directly regulates Sp7 transcription through a unique enhancer located about 11 kb upstream of the Sp7 TSS51. SP7 largely mediates β-catenin-dependent osteogenic differentiation in human pre-osteoblastic and bone marrow stromal cells52. While BRM catalytic subunit of the SWI/SNF complexes was reported to facilitate the transcriptional activation of Sp753, more paradoxical findings demonstrated that BRM-specific SWI/SNF complex exhibited repressive roles on osteoblast differentiation, which contrast with the differentiation-promoting roles of the BRG1-containing SWI/SNF complex18,19. Here, we demonstrate that Sp7 serves as a primary downstream target of BRD9 in regulating osteogenic differentiation. I-BRD9 treatment reduced Sp7 mRNA levels by over 90% within 4 hours compared to DMSO-treated MC3T3 controls. Notably, Brd9 expression shows significant upregulation during osteogenic differentiation. Our SMR analysis identified a functional SNP (rs116511572) located approximately 500 bp upstream of the BRD9 TSS within its promoter region. Intriguingly, computational analysis revealed that RUNX2 binding motifs flank the SNP site within a 1 kb window (−500 to +500 bp) (Fig. S6), suggesting that allelic variants at this locus may impair RUNX2-dependent transcriptional activation of BRD9 during osteoblast differentiation. In addition, both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that BRD9 inhibition led to downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling activity. Therefore, we propose one possible model that BRD9 orchestrates osteogenic processes through dual regulatory mechanisms: initiation of Sp7 transcription and potentiation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. These pathways exhibit functional crosstalk, as evidenced by our findings that BRD9 physically interacts with β-catenin and facilitates β-catenin recruitment to the Sp7 proximal promoter, thereby driving the transcription of Sp7. Rescue experiments further revealed that Sp7 overexpression substantially reversed I-BRD9-induced suppression of Ocn, Col1a as well as Runx2, indicating a positive feedback loop between Sp7 and RUNX2 that reinforces osteogenic commitment. This regulatory relationship aligns with previous reports demonstrating Sp7-mediated upregulation of a Runx2 osteoblast-specific enhancer activity54. Together, our results highlight BRD9 as a critical regulator that orchestrates three major pathways controlling osteogenesis: RUNX2-driven transcription, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and Sp7-mediated differentiation. The identified SNP (rs116511572) may serve as a functional genetic variant influencing this regulatory network through modulation of BRD9 expression.

Bone remodeling is a lifelong process orchestrated by osteocytes, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts. Disruption of this skeletal homeostasis resulted in various skeletal disorders, including osteoporosis, heterotopic ossification (HO) and bone sarcoma. Emerging evidence highlights the critical roles of transcription factors and epigenetic regulators in bone dynamics, offering both prognostic insights and therapeutic opportunities for skeletal diseases. Our findings demonstrated that Brd9 represents a BMD associated locus at the GWAS level, with rs116511572 exhibiting diagnostic potential as a susceptibility locus for osteoporosis. In contrast to bone loss pathologies, HO is characterized by pathological ectopic bone formation in soft tissues55. This condition frequently arises following predisposing events such as orthopedic surgeries (particularly hip arthroplasty), fractures, traumatic injuries (including high-energy extremity trauma, traumatic brain and spinal cord injury) and severe burns56. Despite its clinical significance, therapeutic targets for HO remain poorly defined. Notably, Sp7 expression is elevated in human HO samples compared with controls57. Given our observation that BRD9 induces Sp7 expression, we propose that BRD9 may serve as a promising therapeutic target for HO. Selective degrader of BRD9 has just completed phase I study in patients with advanced synovial sarcoma58. Their potential utility in HO prevention or treatment warrants further validation in preclinical models. Furthermore, bone metastases, a frequent complication of advanced malignancies such as breast cancer, are driven in part by Sp7 mediated osteogenic programming. Osteogenic Sp7-dependent gene expression program promotes both bone metastasis and extracellular matrix remodeling59. Intriguingly, bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) inhibitors have shown efficacy in inducing apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer60. These findings suggest that BRD9 inhibition or degradation may offer a dual therapeutic advantage in advanced breast cancer through direct antitumor activity combined with inhibition of osteogenic niche formation.

Our research has several limitations. First, although SMR analysis identified the non-coding SNP rs116511572 as a variant conferring osteoporosis risk by modulating Brd9 expression, the causal relationship between this genetic variant and Brd9 transcription or osteogenic differentiation requires experimental validation. Future experiments employing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing or base editing to precisely modify the rs116511572 locus could address this problem. Second, although zebrafish and mouse models exhibited consistent skeletal abnormalities, these phenotypes cannot definitively distinguish between impaired osteoblast-mediated bone formation as shown by our data and enhanced osteoclast-driven bone resorption reported in prior studies48. Thus, lineage-specific roles of BRD9 during osteogenesis are required to be investigated through conditional knockout models. Third, while our work focused on the role of Brd9 in osteogenic progenitor cells, the temporal specificity of BRD9 in regulating osteogenesis remains unresolved. Further investigation is required to determine whether Brd9 influences earlier stages of skeletal development, particularly the cell fate determination of mesenchymal stem cells.

Our cross-species integrative approach, leveraging complementary mouse and human datasets, demonstrates the utility of multi-species frameworks to define causative genes underlying GWAS signals. We identify the BRD9/β-catenin/Sp7 regulatory axis as a critical driver of osteoblast differentiation, wherein BRD9 facilitates β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation of Sp7 to promote osteogenesis. Mechanistically, Brd9 deficiency disrupts recruitment of β-catenin to the Sp7 promoter, resulting in impaired osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 6F). These findings elucidate how chromatin remodelers coordinate transcriptional programs to regulate skeletal homeostasis, and suggest potential therapeutic applications for BRD9 inhibition or degradation in bone-related disorders.

Methods

Summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR)

The SMR method was initially designed to elucidate the association between gene expression and traits through analysis of shared genetic variation by integrating GWAS summary statistics with eQTL data26. We retrieved the largest publicly available GWAS summary statistics for estimated bone mineral density (eBMD) measured by heel quantitative ultrasound from the Genetic Factors for Osteoporosis (GEFOS) consortium (Data Release 2018)61. This dataset includes 426,824 European participants and integrates large-scale genetic data from the UK Biobank. The meta-GWAS analysis covers nearly 14 million SNPs, meeting stringent quality control criteria: minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05% and interpolation quality score>0.3. From these summary statistics, we extracted key metrics, including SNP rs numbers, allele information, allele frequency, effect size (β), standard error, P-value, and sample size. These metrics were collated into a specific format (.ma file) optimized for SMR analytical workflows.

We utilized cis-eQTLs (within a 2-Mb window from the start and end of the gene) as instrumental variables for gene expression. Since eQTL data from human osteoblast cells were unavailable, we obtained summary-level statistics for fibroblast eQTLs from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project62. This dataset includes 15,201 RNA sequence samples from 49 tissues across 838 participants. Only probes with a P value threshold of 5.0 × 10−8 were included to select the top-associated eQTLs for SMR analysis, based on the assumption that the instrumental variable should have a strong effect on the exposure. GTEx fibroblasts eQTLs summary data were from the website link https://yanglab.westlake.edu.cn/software/smr/#eQTLsummarydata.

The fundamental principle of SMR is to test the causal chain Z → X → Y, where an instrumental variable (Z) influences a phenotypic trait (Y) through its effect on gene expression levels (X). In this study, eBMD was selected as the phenotypic trait (Y), gene expression level as the exposure factor (X), and top cis-eQTLs, which are closely related to gene expression, as the instrumental variable (Z). During data analysis, we accounted for multiple factors that might affect the results. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between genetic loci was corrected to eliminate potential biases due to genetic locus correlation. LD estimates were derived from individual-level SNP genotype data from the 1000 Genomes Project. For probes that reached genome-wide false discovery rate (FDR) significance (PSMR < 0.05), we further performed the heterozygosity-independent instrumental (HEIDI) test to distinguish between pleiotropy and linkage. We retained only those probes with non-significant evidence of heterogeneity (PHEIDI > 0.05) and generated SMR locus plots for significant probes. SMR software was downloaded from http://cnsgenomics.com/software/smr/.

Statistical fine-mapping with FINEMAP

To identify credible causal variants identified in SMR, statistical fine-mapping was performed using FINEMAP v1.4.2 with default parameters63. The analysis was based on GWAS summary statistics and utilized a shotgun stochastic search algorithm to efficiently evaluate the most probable combinations of causal variants under a Bayesian framework. In FINEMAP, a log10-transformed Bayes factors (log10BF) for the individual SNPs greater than 2 is considered evidence for a credible risk variant64, while a value exceeding 6.1 indicates strong genome-wide significance in the GWAS, suggesting the variant is potentially causal for eBMD. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was generated from a reference panel consisting of 100,000 unrelated individuals of European ancestry from the UK Biobank, processed using LDstore65. For each risk locus, SNPs were ranked in descending order based on their posterior probability of being causal.

Analysis of Potential Binding Motifs of RUNX2

The JASPAR database was employed to predict potential RUNX2 transcription factor binding sites within a 1,000 bp genomic region centered on the lead SNP locus (chr5: 892,837-893,837; GRCh38.p14). Briefly, the RUNX2 binding motif was retrieved from JASPAR 2024 (http://jaspar.genereg.net) in the form of a position frequency matrix (PFM), along with the corresponding sequence logo depicting nucleotide conservation across known binding sites. Using the TFBSTools66 and Biostrings67 R packages, the PFM was converted into a position weight matrix (PWM). Potential binding sites were predicted by scanning the target sequence with the PWM using a relative score threshold of ≥0.8.

International Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (IMPC) data analysis

The IMPC was a global initiative aimed at identifying the function of every protein-coding gene in the mouse genome. This project systematically characterizes mice with single-gene knockout (KO) mutations, focusing on homozygous mutants or heterozygous mutants when homozygotes are lethal or sub-viable. The goal is to create a comprehensive map linking genes to phenotypes through multidimensional phenotyping data. The IMPC employs a comprehensive phenotyping process that covers a wide range of assessments, including appearance, behavior, and the function of various organs and tissues. For skeletal phenotyping, assessments are conducted using radiographic imaging and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to evaluate bone morphology, BMD, and bone mineral content. Bone mineral data generated by the IMPC are analyzed using PhenStat, a statistical tool that employs linear mixed models to account for factors such as sex and body weight. All phenotyping data generated by the IMPC are publicly available on the IMPC website. A systematic search of the IMPC database was conducted up to May 9, 2023 including 8,481 phenotyped genes (Data Release 19.0). In this study, a total of 1,258 genes related with skeletal phenotype were included and analyzed.

Experimental animals

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) of wild-type AB strain and Tg(sp7:EGFP) were raised under standard laboratory conditions with 14-h light/10-h dark cycle at a temperature of 28.5 ± 1°C. Embryos were obtained by natural crosses and fertilized eggs were raised at 28.5°C. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Soochow University, protocol number SUDA20251104A01. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Zebrafish embryo microinjection

The night prior to injection, zebrafish were set up in breeding tanks with dividers in place. The following morning, after the room lights turned on, the dividers were removed from selected tanks to allow for approximately 20–30 minutes of undisturbed mating. Eggs were collected from the breeding cages using a strainer and rinsed with egg water. After randomization, the pooled eggs were transferred onto a microinjection plate using a transfer pipette. Brd9 Morpholinos (brd9 MO: 5’-TGTATTTCTTGTGTTTCTTCCCCAT-3’, Gene tools) targeting zebrafish brd9 were re-suspended in distilled water as a 16 μg/μl stock solution and diluted to the appropriate concentrations for microinjections in 0.2% PhenolRed and 0.1 M KCl. A standard control MO (cMO: 5’-CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA-3’, Gene tools) was used as a negative control. mRNA of sp7 and β-catΔN (a constitutively active form of β-catenin) were synthesized by mMESSAGE mMACHINE kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). The efficiency of brd9 MO was determined by an EGFP reporter construct pCS2+brd9: EGFP. Briefly, a 181-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the 5’-untranslated region (93 bp) and partial coding sequence (88 bp containing the MO target regions) of the zebrafish brd9 gene was generated by PCR primers brd9 MOF and brd9 MOR (Supplementary table 1). The amplified DNA was subcloned in frame into pCS2EGFP using the BmaHI and EcoRI sites to fuse the brd9 partial sequence N-terminally of EGFP. Zebrafish embryos at the one-two cell stage were microinjected with 1 nl of solution using a microinjector (MPPI-3, ASI) and a micromanipulator (Narishige) with an injection pressure of 20 psi. To evaluate MO efficiency, embryos received injections of pCS2+brd9: EGFP along with either cMO or brd9 MO at varying doses (1, 2, or 4 ng). For rescue assays, 1 nl of cMO, brd9 MO with or without sp7 or β-catΔN mRNA were injected. After microinjection, embryos were raised in Petri dishes with embryo medium at 28.5 °C. Following tricaine anesthesia on ice, zebrafish larvae for each group were collected for morphological examination, RNA extraction, western blotting, BRD9:EGFP detection or fixed with parformaldehyde (PFA) for alizarin red staining at the indicated time, respectively.

Drug treatment of zebrafish

I-BRD9 (Cayman chemical, USA) and XAV-939 (MCE, China) were first dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in embryo media. Wild-type or Tg (Sp7:EGFP) zebrafish larvae at 3 dpf (days post-fertilization) were placed into a 6-well plate with 20 larvae per well and washed three times. For initial concentration screening, wild-type larvae were exposed to a range of concentrations (10, 20, and 40 μM) for I-BRD9, XAV-939 or a DMSO control. Based on these results, the definitive experiments employed 20 μM I-BRD9, 10 μM XAV-939, or a DMSO control in treating wild-type or Tg (Sp7:EGFP) zebrafish larvae. The drug-containing media were changed daily throughout the treatment period. Three days later, the samples were collected for EGFP detection, RNA extraction, western blotting or alizarin red staining, respectively.

Plasmid construction

To generate Brd9, Sp7, and β-catenin overexpression plasmids, the coding region of respective genes were amplified by PCR, and then cloned into pCMV vector digested by BamH1/XhoI enzymes with ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, c112-01-AB). For the construction of luciferase vectors, different regions of putative 3000 bp promoter upstream of the Sp7 transcription start site (TSS) (−3000~−2000, −2000~−1000, and −1000~+1) were cloned into pGL3-enhancer luciferase vector via KpnI/NheI enzyme digestion. All the constructed plasmids were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Cell culture and transfection

Both human HEK293T cells and mouse osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 cells were purchased from the Institute of Cell Bank/Institutes for Biological Sciences (Shanghai, China). HEK293T and MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) and MEM Alpha Modification (Cytiva) respectively, with addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biological Industries) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The cell passage number between 5 and 20 were used for all experiments. For in vitro osteogenic differentiation, MC3T3-E1 cell line was maintained in basic medium supplemented with 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 0.05 mM ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (all from Sigma-Aldrich, USA)68. For the BRD9 inhibition assays, cells were treated with either DMSO or I-BRD9 at the final concentrations of 10 μM. The osteogenic media was changed every three days, and I-BRD9 was added each time the media was changed. ALP staining was performed via the TRACP & ALP double-stain Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). Transfections were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA). Briefly, cells were seeded to reach approximately 70–90% confluency at the time of transfection. For each well, plasmid DNA was mixed with P3000 enhancer in Opti-MEM. In a separate tube, Lipofectamine 3000 was diluted in Opti-MEM. The two solutions were combined, incubated for 15 min at room temperature, and added drop-wise to the cells. Cells were harvested for analysis 48 hours later.

Total RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR)

The harvested MC3T3-E1 cells were lysed in 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) at room temperature for 5 minutes. Zebrafish were collected in a 1.5 ml microfuge tube, and the water was removed as much as possible. The samples were then homogenized in 250 μL of TRIzol reagent. Subsequently, an additional 750 μL of TRIzol was added to achieve a final volume of 1 mL. Subsequently, 200 μL of chloroform was added to the lysate, followed by vigorous vortexing and incubation at room temperature for 5 minutes. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C and the RNA was exclusively localized in the colorless upper aqueous phase. Then, the aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a fresh tube, and mixed with an equal volume of isopropanol. After incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatant was discarded and the RNA pellet was washed with 1 mL of 75% ethanol. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 minutes at 4 °C, the RNA pellet was air-dried and resuspended in RNase-free water. The concentration and purity of the isolated RNA were assessed using a Nanodrop2000 spectrophotometer. The obtained RNA was suitable for subsequent reverse-transcription and RNA-Sequencing experiments.

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed using HiScript III SuperMix (Vazyme, China). Then, the relative amounts of each mRNA transcript were analyzed by ABI Q6 Flex system (ABI, USA) with SYBR Green mix (Vazyme, China). In the RT-qPCR experiments involving MC3T3-E1 cells, GAPDH was used as the internal control. For zebrafish samples, β-actin served as the internal reference gene. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Primer sequences used in RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary table 1.

RNA-sequencing analysis

For RNA-sequencing analysis, libraries were prepared using NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit and then sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Sequence quality was first surveyed with FastQC (version 0.12.1). Pair-end raw reads were trimmed by Trimmomatic and mapped to the mouse genome assembly mm10.GRCm38 reference genome obtained from the UCSC genome browser database using Bowtie2 (version 2.7.11b). mRNA expression was quantified using featureCounts (version 2.0.3). Differentially expressed mRNA was calculated by the DESeq2R package (version 1.38.3) with the cutoff Fold change >1.5 and adjusted P value < 0.05. The KEGG and GO enrichment analyses were performed using the function “enrichKEGG” and “enrichGO” from the R package clusterProfiler (version 4.6.2). GO enrichment analyses of chord plots were performed using the functions “circle_dat” and “chord_dat” in the R package GOplot (version 1.0.2). We performed heatmap visualization using the pheatmap package in R (version 2.22.0) to illustrate differential expression profiles. Protein interaction data were obtained from the STRING database and imported into Cytoscape (version 3.10.2), with nodes representing proteins and edges representing interactions.

Dual luciferase reporter assays

The Sp7-promoter luciferase reporters (−3000~−2000, −2000 ~−1000, and −1000~+ 1) or Topflash luciferase reporter were transfected into HEK-293T cells using Lipofectamine 3000 alone or with simultaneous cotransfection of brd9, β-catenin expression plasmids or I-BRD9 treatment. After 48 h incubation, transfected HEK-293T cells were assayed with dual luciferase reporter gene assay kit (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control to correct transfection efficiency variation.

Alizarin red staining

Bone mineralized matrix deposition, an important indicator of bone formation, was evaluated using alizarin red staining. At 6 dpf, zebrafish larvae were collected and fixed for 2 hours in a 4% PFA solution, then stained with 0.1% alizarin red (BBI, China) in 0.5% potassium hydroxide69. Larval were placed on a slide and images of the dorsal aspect head bone of zebrafish larvae were photographed using a SMZ18 stereo microscope (Nikon, Japan) equipped with a DS-Ri2 camera (Nikon, Japan). The area of alizarin red staining was determined using ImageJ image analysis software (National Institutes of Health, USA). More than nine pieces of zebrafish were used in each group.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments

Approximately 1×107 MC3T3-E1 cells were lysed in 600 μL of lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and protein inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete Mini, Roche). After 30 min incubation at 4 °C, the lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet cellular debris. Supernatants were collected and pre-cleared, then incubated with 1 μg of BRD9 primary antibody (Active motif, 61537) or IgG primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, I8140) for 1–2 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking. Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Thermo Scientific, 88803) were then added to the antibody-antigen complexes and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Beads-bound complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer to remove non-specific interactions. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by boiling in 1× Laemmli loading buffer by heating at 100 °C for 5 min. The eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by western blotting.

Western blotting

Total protein from cells and zebrafish larvae was extracted and homogenized in RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, 9806S) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete Mini, Roche). Cell lysate was quantified using a BCA kit (Vazyme, E112-01) and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were loaded into the wells of SDS-PAGE gel, along with molecular weight markers (Vazyme, MP102-01). Run the gel in Running buffer (25 mM Tris, 190 mM Glycine, 0.1% SDS) for 5 min at 80 V and then increase the voltage to 130 V to finish the run in about 1 hour. Next, the protein was electrotransferred from the gel to the PVDF membranes (Millipore, IPVH00010) in 1×Transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 190 mM Glycine and 20% methanol) at 200 mA for 2 hours. Rinse the blots with TBST (TBS, 0.1% Tween-20) three times. After block with 5% milk (Biofroxx) in TBST for 1 h, the blots were incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibodies, including BRD9 antibody (Active motif, 61537, 1:1000), β-CATENIN antibody (Cell signaling, D10A8, 1:1000), TUBULIN (Proteintech, 11224-1-AP, 1:20000), OCN (Affinity Biosciences, DF12303, 1:2000), RUNX2 (Proteintech, 20700-1-AP, 1:1000), ALPL (Affinity Biosciences, DF6225, 1:1000), SP7 (Affinity Biosciences, DF7731, 1:2000), GAPDH (abcam, ab128915, 1:20000). After rinsing 3 times for 10 min with TBST, the blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated Affinipure Goat Anti-Mouse lgG (H + L) (Proteintech, SA00001-1, 1:5000) and HRP-conjugated Affinipure Goat Anti-Rabbit lgG (H + L) (Proteintech, SA00001-2, 1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature. After rinsing 3 times for 10 min with TBST, the blots were applied with SuperPico ECL Chemiluminescence Kit (Vazyme, E422-C1). Chemiluminescent signals were captured using ChemiDoc XRS system (Bio-Rad). The protein band intensity was quantified using Image J software.

ChIP-qPCR assay

Approximately 1 × 107 MC3T3-E1 cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde solution for 10 minutes at room temperature and Glycine was used to stop reaction. Collected cell pellet was lysed in lysis buffer (1.2% SDS, 10 mM EDTA PH8.0, 50 mM Tris-HCl PH8.0), chromatin was sheared to an average size of 200-500 bp using a Bioruptor Plus (Diagenode). The sheared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with 2 μg of indicated antibodies, including BRD9 antibody (Active motif, 61537) and β-CATENIN antibody (Cell signaling, D10A8), coupled to Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Thermo Scientific, 88803) overnight at 4°C. After washing the beads with low-salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA PH8.0, 20 mM Tris-HCl PH8.0, 150 mM NaCl), high-salt wash buffer (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA PH8.0, 20 mM Tris-HCl PH8.0, 500 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 M LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% Sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA PH8.0, 10 mM Tris-HCl PH8.0) and TE wash buffer (1 mM EDTA PH8.0, 10 mM Tris-HCl PH8.0). The chromatin was de-crosslinked with elution buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, 1% SDS) shaking in 1300 rpm at 65 °C for 6 hours. DNA was purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification and subjected to qPCR analysis. Data were normalized to input values and calculated as percent input recovery. The primers used for ChIP-qPCR are listed in Supplementary table 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test for mean comparisons of two groups. For each experiment, a minimum of three independent biological replicates were performed, each with three technical replicates. All statistical plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

L.F.W., Y.B.Z. and W.Y.R. conceptualized the work and supervised the overall experiments. L.F.W., L.W., Q.Y.Z., Y.L.L., X.R.S., M.J.L. and Q.A.L. performed the cell culture experiments for functional assays and mechanistic analyses. Y.Z., Y.L. and M.M. conducted the zebrafish experiments. L.F.W., Y.F.W. and Z.J.C. performed bioinformatic analyses. X.Y.J., S.F.L. and X.H.L. helped with supervision of the project. L.F.W., Y.B.Z. and W.Y.R. were responsible for manuscript writing, reviewing, and editing.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Fine-mapping results are available in Supplementary Data 1, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified from the RNA-seq analysis are provided in Supplementary Data 2. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data 3. Uncropped and unedited blot images are provided in Supplementary Fig. 7. The raw RNA-Seq data are uploaded in the NCBI GEO database under accession number GSE308048. Seven generated plasmids have been deposited in Addgene under ID numbers #248780 to #248787. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

All analysis code used in this study are available on Github at https://github.com/Wanglei3125/BRD9_Communications-Biology_20251014/blame/main/README.md.

References

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, D. & Therapy. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285, 785–795 (2001).

Bonjour, J. P., Chevalley, T., Rizzoli, R. & Ferrari, S. Gene-environment interactions in the skeletal response to nutrition and exercise during growth. Med. Sport Sci. 51, 64–80 (2007).

Xie, G. et al. Smoking and osteoimmunology: Understanding the interplay between bone metabolism and immune homeostasis. J. Orthop. Transl. 46, 33–45 (2024).

Yalaev, B. I. & Khusainova, R. I. Epigenetic regulation of bone remodeling and its role in the pathogenesis of primary osteoporosis. Vavilovskii Zh. Genet Selektsii 27, 401–410 (2023).

Huo, S. et al. Epigenetic regulations of cellular senescence in osteoporosis. Ageing Res. Rev. 99, 102235 (2024).

Yang, C., Chen, L., Guo, X., Sun, H. & Miao, D. The Vitamin D-Sirt1/PGC1alpha Axis regulates bone metabolism and counteracts osteoporosis. J. Orthop. Transl. 50, 211–222 (2025).

Cho, K. S., Elizondo, L. I. & Boerkoel, C. F. Advances in chromatin remodeling and human disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 308–315 (2004).

Wendegatz, E. C., Engelhardt, M. & Schuller, H. J. Transcriptional activation domains interact with ATPase subunits of yeast chromatin remodelling complexes SWI/SNF, RSC and INO80. Curr. Genet. 70, 15 (2024).

Maassen, A. et al. SWI/SNF-type complexes-transcription factor interplay: a key regulatory interaction. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 30, 30 (2025).

Laubscher, D. et al. BAF complexes drive proliferation and block myogenic differentiation in fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 12, 6924 (2021).

Orlando, K. A., Nguyen, V., Raab, J. R., Walhart, T. & Weissman, B. E. Remodeling the cancer epigenome: mutations in the SWI/SNF complex offer new therapeutic opportunities. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 19, 375–391 (2019).

Kim, J. M., Lin, C., Stavre, Z., Greenblatt, M. B. & Shim, J. H. Osteoblast-Osteoclast Communication and Bone Homeostasis. Cells 9, 2073 (2020).

Shi, F. et al. Identification and function of periosteal skeletal stem cells in skeletal development, homeostasis, and disease. J. Orthop. Transl. 51, 177–186 (2025).

Wang, L., You, X., Zhang, L., Zhang, C. & Zou, W. Mechanical regulation of bone remodeling. Bone Res. 10, 16 (2022).

Young, D. W. et al. SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex is obligatory for BMP2-induced, Runx2-dependent skeletal gene expression that controls osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell Biochem. 94, 720–730 (2005).

Busby, T. et al. Baf45a Mediated Chromatin Remodeling Promotes Transcriptional Activation for Osteogenesis and Odontogenesis. Front Endocrinol. 12, 763392 (2021).

Pico, M. J. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor-mediated cis-repression of osteogenic genes requires BRM-SWI/SNF. Bone Rep. 5, 222–227 (2016).

Nguyen, K. H. et al. SWI/SNF-Mediated Lineage Determination in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Confers Resistance to Osteoporosis. Stem Cells 33, 3028–3038 (2015).

Giles, K. A. et al. Integrated epigenomic analysis stratifies chromatin remodellers into distinct functional groups. Epigenet. Chromatin 12, 12 (2019).

Rawal, Y., Qiu, H. & Hinnebusch, A. G. Distinct functions of three chromatin remodelers in activator binding and preinitiation complex assembly. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010277 (2022).

Zhu, X., Bai, W. & Zheng, H. Twelve years of GWAS discoveries for osteoporosis and related traits: advances, challenges and applications. Bone Res. 9, 23 (2021).

Lin, Y. J. et al. Genetic predisposition to bone mineral density and their health conditions in East Asians. J. Bone Min. Res. 39, 929–941 (2024).

Greenbaum, J. et al. A multiethnic whole genome sequencing study to identify novel loci for bone mineral density. Hum. Mol. Genet. 31, 1067–1081 (2022).

Nica, A. C. & Dermitzakis, E. T. Expression quantitative trait loci: present and future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20120362 (2013).

Al-Barghouthi, B. M. et al. Transcriptome-wide association study and eQTL colocalization identify potentially causal genes responsible for human bone mineral density GWAS associations. Elife 11, e77285 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Integration of summary data from GWAS and eQTL studies predicts complex trait gene targets. Nat. Genet. 48, 481–487 (2016).

Foley, C. N. et al. A fast and efficient colocalization algorithm for identifying shared genetic risk factors across multiple traits. Nat. Commun. 12, 764 (2021).

Swan, A. L. et al. Mouse mutant phenotyping at scale reveals novel genes controlling bone mineral density. PLoS Genet. 16, e1009190 (2020).

Dietrich, K. et al. Skeletal Biology and Disease Modeling in Zebrafish. J. Bone Min. Res. 36, 436–458 (2021).

Kague, E. et al. Osterix/Sp7 limits cranial bone initiation sites and is required for formation of sutures. Dev. Biol. 413, 160–172 (2016).

Flores, M. V., Lam, E. Y., Crosier, P. & Crosier, K. A hierarchy of Runx transcription factors modulate the onset of chondrogenesis in craniofacial endochondral bones in zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 235, 3166–3176 (2006).

Marakulina, D. et al. EpiFactors 2022: expansion and enhancement of a curated database of human epigenetic factors and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D564–D570 (2023).

Du, J. et al. BRD9-mediated chromatin remodeling suppresses osteoclastogenesis through negative feedback mechanism. Nat. Commun. 14, 1413 (2023).

Gatchalian, J. et al. A non-canonical BRD9-containing BAF chromatin remodeling complex regulates naive pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 9, 5139 (2018).

Shimizu, T., Bae, Y. K., Muraoka, O. & Hibi, M. Interaction of Wnt and caudal-related genes in zebrafish posterior body formation. Dev. Biol. 279, 125–141 (2005).

Weidinger, G., Thorpe, C. J., Wuennenberg-Stapleton, K., Ngai, J. & Moon, R. T. The Sp1-related transcription factors sp5 and sp5-like act downstream of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Curr. Biol. 15, 489–500 (2005).

Jiang, Q. et al. Roles of Sp7 in osteoblasts for the proliferation, differentiation, and osteocyte process formation. J. Orthop. Transl. 47, 161–175 (2024).

Gaur, T. et al. Canonical WNT signaling promotes osteogenesis by directly stimulating Runx2 gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 33132–33140 (2005).

Felber, K., Elks, P. M., Lecca, M. & Roehl, H. H. Expression of osterix Is Regulated by FGF and Wnt/beta-Catenin Signalling during Osteoblast Differentiation. PLoS One 10, e0144982 (2015).

DeLaurier, A. et al. Zebrafish sp7:EGFP: a transgenic for studying otic vesicle formation, skeletogenesis, and bone regeneration. Genesis 48, 505–511 (2010).

Nelson, M. R. et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet. 47, 856–860 (2015).

Denu, R. A. et al. Fibroblasts and Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells Are Phenotypically Indistinguishable. Acta Haematol. 136, 85–97 (2016).

Zhou, N. et al. BMP2 induces chondrogenic differentiation, osteogenic differentiation and endochondral ossification in stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 366, 101–111 (2016).

Fallah, A., Beke, A., Oborn, C., Soltys, C. L. & Kannu, P. Direct Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Osteoblasts: Techniques and Methodologies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 13, 362–370 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Discovery and validation of sub-threshold genome-wide association study loci using epigenomic signatures. Elife 5, e10557 (2016).

Li, Z. et al. Integrating mouse and human genetic data to move beyond GWAS and identify causal genes in cholesterol metabolism. Cell Metab. 31, 741–754.e5 (2020).

Yu, W., Wang, H. L., Zhang, J. & Yin, C. The effects of epigenetic modifications on bone remodeling in age-related osteoporosis. Connect Tissue Res. 64, 105–116 (2023).

Xiao, M. et al. BRD9 determines the cell fate of hematopoietic stem cells by regulating chromatin state. Nat. Commun. 14, 8372 (2023).

Wu, S., Han, N., Zheng, Y., Hu, C. & Lei, Y. The role of Snf5 in the osteogenic differentiation potential during replicative senescence of rat mesenchymal stromal cells. Mech. Ageing Dev. 171, 1–6 (2018).

Rodda, S. J. & McMahon, A. P. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development 133, 3231–3244 (2006).

Hojo, H. et al. Runx2 regulates chromatin accessibility to direct the osteoblast program at neonatal stages. Cell Rep. 40, 111315 (2022).

Liu, B., Wu, S., Han, L. & Zhang, C. beta-catenin signaling induces the osteoblastogenic differentiation of human pre-osteoblastic and bone marrow stromal cells mainly through the upregulation of osterix expression. Int J. Mol. Med. 36, 1572–1582 (2015).