Abstract

TGFβ1 and ferroptosis are key drivers of organ fibrosis, but their crosstalk remains unclear. This study aims to identify the key regulatory ubiquitin-specific protease (USP) in organ fibrosis, TGFβ signaling transduction, and ferroptosis. Here, we show that global or renal tubule-specific deletion of Usp2 ameliorates kidney fibrosis in UUO models of male mice, while kidney tubule-specific Usp2 overexpression exacerbates fibrosis and reverses the protective effect conferred by global Usp2 deletion. Mechanistically, USP2 deubiquitinates TXNDC5, an ER protein that stabilizes TGFβR1 to activate TGFβ signaling. USP2 also deubiquitinates the transferrin receptor (TFRC), enhancing TFRC’s role in promoting ferroptosis. TGFβ1 lactylates USP2 at Lys447 to facilitate deubiquitination of TXNDC5 and TFRC, whereas SIRT2 delactylates USP2 at Lys447 to suppress its activity. Notably, the USP2 inhibitor ML364 alleviates fibrosis in male mouse models of kidney, liver, and lung mouse models. Our findings establish USP2 as a key regulator of the TGFβ pathway and ferroptosis, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for fibrosis

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organ fibrosis may be triggered by diverse stimuli, including hypoxia, oxidative stress, growth factors, ferroptosis, and inflammatory cytokines1,2,3,4,5,6. Among these, TGFβ1 is recognized as the pivotal fibrogenic trigger, which transduces the fibrotic signals of multiple stimuli such as inflammatory factors, Ang-II, endothelin 1, ischemia, and high glucose1,7,8. TGFβ1 exerts its biological functions via binding to the TGFβ1 receptor localized on the cell membrane. This receptor is a heterodimer composed of TGFβ type I receptor (TGFBR1) and type II receptor (TGFBR2) subunits. TGFBR2 is responsible for recognizing extracellular TGFβ1; upon binding to TGFβ1, it recruits TGFBR1 and induces its phosphorylation, thereby activating downstream canonical (SMAD-dependent) and non-canonical (non-SMAD-dependent) intracellular signaling cascades. The profibrotic effects of TGFβ1 rely on both the alteration of its own expression and the sequential activation of downstream signaling pathways9,10,11,12. In contrast to the well-documented changes in TGFβ1 expression, the regulatory mechanisms governing individual downstream signaling molecules under pathological conditions remain poorly understood13.

In the downstream signaling pathway of TGFβ1, the stability of numerous molecules is subject to regulation through various mechanisms, with the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) being a key player14,15,16,17,18. The UPS is the primary intracellular non-lysosomal pathway for protein degradation, consisting of substrates, ubiquitin molecules, ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), ubiquitin-ligase enzymes (E3), 26S proteasomes, and deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs)15,19,20,21. DUBs are enzymes that cleave ubiquitin from target proteins and other molecules by hydrolyzing the ester, peptide, or isopeptide bonds at the carboxyl terminus of ubiquitin, thus counteracting ubiquitination-driven protein degradation19,22,23. USP11 belongs to the ubiquitin-specific protease subfamily of DUBs24. Previous studies have shown that USP11 can modulate the ubiquitination status of TGFBR2 and participate in the progression of pulmonary fibrosis25. However, the key USP family members involved in the TGFβ1-mediated profibrotic signaling pathway have not been fully clarified.

Regulatory cell death modalities include classical apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis and ferroptosis, with ferroptosis as a novel regulatory cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, is regulated by intracellular iron metabolism, lipid metabolism, the GSH/GPX4 repair system, coenzyme Q10, and other genes26,27,28,29. Lipid peroxidation, GPX4 inhibition, and iron accumulation lead to ferroptosis, resulting in an abnormal accumulation of fibrotic lesions in the tissues, which promotes tissue and organ fibrosis30. The specific ferroptosis marker transferrin receptor (TFRC) plays a crucial role in cellular iron transport31. The extracellular complex formed by transferrin and Fe³⁺ binds to the TFRC, allowing Fe³⁺ to be converted to Fe²⁺, which is subsequently translocated to the cytoplasm for utilization32. It has been shown that pulmonary fibrosis symptoms in mice can be significantly attenuated by specifically knocking down TFRC expression in mouse fibroblasts33. TGFβ and ferroptosis have been widely studied in a variety of fibrosis models. Increased ferroptosis is usually accompanied by increased fibrosis, suggesting that there may be a link between TGFβ and ferroptosis. The mechanisms by which TGFβ affects ferroptosis is still not fully understood and requires further research.

In this study, we set out to elucidate the pivotal role of USP2 in the regulation of the TGFβ signaling pathway and ferroptosis. Our initial observations indicated that USP2 significantly influences the stability of TGFBR1 and TFRC. With TGFBR1 being a critical component of TGFβ signaling and TFRC playing a central role in the regulation of ferroptosis, we aimed to dissect the intricate mechanisms by which USP2 modulates the stability of these proteins, thereby impacting their respective pathways. This exploration is crucial for understanding how USP2 acts as a regulatory hub in the context of fibrosis and cellular iron homeostasis.

Methods

Studies in animals

All animal care and experimental protocols for in vivo studies conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; NIH publication no.:85–23, revised 2011). The sample size for the animal studies was calculated based on a survey of data from published research or preliminary studies. Usp2−/− (C57BL/6JGpt-Usp2em7Cd1220d392in5/Gpt; Strain ID: T052377; MGI ID: 1858178) mice on a C57BL/6J background were purchased from Gempharmatech Co. Ltd (Jiangsu, Nanjing, China). Usp2flox/flox (C57BL/6JCya-Usp2em1flox/Cya; Strain ID: S-CKO-11600) mice on the C57BL/6J background were purchased from Cyagen Biosciences (Guangzhou, Guangdong, China). Ksp-Cre (C57BL/6Smoc-Cdh16em(Kozak-CreERT2)1Smoc; Strain ID: NM-KI-225084; MGI ID: 106671) were purchased from Shanghai Southern Model Organism Science and Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Male mice aged 8–10 weeks were used in all experiments.

The Ksp-Cre recombinase is paternally transmitted (with the cross combination of Usp2flox/flox females × Ksp-Cre males). These mice were maintained in SPF units of the Animal Center of Shenzhen People’s Hospital with a 12 h light cycle from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., 23 ± 1 °C, 60–70% humidity. Mice were allowed to acclimatize to their housing environment for 7 days before the experiments. At the end of the experiments, all mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2–3% in oxygen for induction and maintenance) and euthanized in a CO2 chamber, followed by the collection of kidney tissues. All animals were randomized before treatment. Mice were treated in a blinded fashion, as the drugs used for treating animals were prepared by researchers who did not carry out the treatments. No mice were excluded from the statistical analysis. Studies were performed in accordance with the German Animal Welfare Act, and reporting follows the ARRIVE guidelines34.

Ethical statement

All animal care and experimental protocols for in vivo studies were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; NIH publication no.: 85–23, revised 1996), and were approved by the Animal Care Committees of the First Affiliated Hospital of Southern University of Science and Technology (Approval No.: AUP-240226-YS-0014-01). This study complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal experimentation. All experiments were reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines34.

Mouse kidneys were transfected with an adeno-associated virus vector (AAV)

Eight-week-old mice received in situ kidney injection with adeno-associated virus vector (AAV). After the mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg body weight). Prior to surgery, the abdominal area was shaved and disinfected with 75% ethanol, followed by povidone-iodine to ensure sterile conditions. A midline incision was made to gently exteriorize the kidney (kept moist with pre-warmed PBS), and injections were delivered via a 30-gauge insulin syringe. Three independent points were selected in the renal cortex (≈1 mm below the capsule, targeting tubule-rich regions to enhance Ksp promoter-mediated specificity), with 10–15 μl virus (2.5 × 10¹¹ v.g.) injected slowly over 10–15 s per point to avoid excessive pressure; the needle was retained for 5 s post-injection to minimize backflow and ensure viral retention. Mice were divided into groups (n = 6 per group) receiving AAV9-empty vector (AAV9-Ctrl), AAV9-Ksp-Usp2 (Usp2 OE group), AAV9-Ksp-Usp2 K447R (mutant group), and AAV9-Ksp-short hairpin RNA targeting Usp2 (AAV-shUsp2); all AAV constructs were provided by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). After injection, the kidney was carefully repositioned into the abdominal cavity, and the incision was closed with 4-0 absorbable sutures for the muscle layer and skin clips for the epidermis. Postoperatively, mice were placed on a heating pad maintained at 37 °C until full recovery from anesthesia to prevent hypothermia. Mice were monitored for 24 h post-surgery for signs of distress (e.g., reduced activity, abnormal grooming, or labored breathing). During the 2-week housing period under standard conditions to allow transgene expression, mice had free access to food and water, and skin clips were removed 7 days post-surgery.

Mice kidney fibrotic models

Male mice (~8 to 10 weeks old) were subjected to various kidney injury models to induce renal fibrosis. To establish the UUO model, male C57BL/6 mice (Strain ID: N000013; Gempharmatech Co., Ltd., Jiangsu, Nanjing, China) were given general anesthesia by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight). The left ureter was exposed via a left flank incision, ligated with 4-0 silk at two points, and cut between the two ligation points. The Sham-operated group underwent the same surgical procedure without ureter ligation. Mice were sacrificed, and the left kidneys were collected 10 days after surgery.

Liver and pulmonary fibrosis models

Liver fibrosis models were established using CCl4. In the CCl4 (Macklin, Shanghai, China; Cat.No.C805329)(1:4 diluted in corn oil)-induced mouse liver fibrosis model, mice were administered CCl4 by i.p. injection at a dose of 5 μL/g body weight every 3 days for 6 weeks (corn oil i.p. injection was used as the control group).

Pulmonary fibrosis models were established using bleomycin (BLM; MedChemExpress, USA, Cat. No. HY-17565). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (inhalation, 2–3% for induction) and fixed in a supine position with the neck extended. Using a 100-μL microsyringe, BLM (2 U/kg BW, 50 μL/mouse) was slowly instilled into the trachea under direct visualization of the airway opening; mice in the Ctrl group received 50 μL of 0.9% NaCl via the same procedure. After instillation, mice were held upright for 30 s to facilitate uniform distribution of the solution in the lungs, then placed in a warm cage to recover. On day 21, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized in a CO2 chamber, followed by the collection of lung tissues.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Cytoplasmic or nuclear extracts were prepared from cells using a cytoplasmic and nuclear protein isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 78833). Briefly, the tube was vortexed vigorously in the highest setting for 15 s to fully suspend the cell pellet. The tubes were incubated on ice for 10 min. Next, ice-cold cytoplasmic extraction reagent II solution was added to the tubes. The tube was vortexed and incubated on ice. The tube was centrifuged for 5 min at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge (~16,000 × g), and the supernatant (cytoplasmic extract) was transferred to a tube. The insoluble (pellet) fraction, which contains nuclei, was suspended in ice-cold nuclear extraction reagent and then vortexed at the highest setting for 15 s. The sample was placed on ice and vortexed for 15 s every 10 min for 40 min. The tube was centrifuged at maximum speed (~16,000 × g) in a microcentrifuge for 10 min, and the supernatant (nuclear extract) fraction was transferred to a tube. For total protein extraction, tissues or cells were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (containing 1% protease and phosphatase inhibitors) using a mechanical homogenizer. The lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA assay (Pierce™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Samples were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until further analysis.

For western blot analysis, 50 µg of lysate was loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Proteins were analyzed with their corresponding specific antibodies (dilution ratio: 1:1000). Details of antibody suppliers and catalog numbers are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Densitometry analysis was performed using Quantity One® Software and quantified relative to the loading control, Tubulin.

Histological analysis

Kidney, liver, and pulmonary tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced into 5-μm-thick serial sections using a paraffin slicer. For kidney, liver, and lung histology, the paraffin sections were stained using Masson’s trichrome (Solarbio & Technology, Beijing, Cat. No. G1345, China) and Sirius red staining kit (Solarbio & Technology, Beijing, Cat. No. G1472, China).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted by Trizol (Invitrogen) and dissolved in an appropriate amount of RNase-free water. cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (Cat. No. AT101-02, TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed on an ABI StepOnePlusTM Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green I-based fluorescence chemistry (SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, Cat. No. RR820Q, Takara, Dalian, China). The 20 μL reaction system contained 10 μL SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, 0.4 μL forward primer (10 μM), 0.4 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 2 μL cDNA template (50 ng/μL), and 7.2 μL RNase-free water. The qPCR program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 5 s and annealing-extension at 60°C for 30 s (two-step method). Specific primers for target genes are listed in Table S2. The relative mRNA levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, with β-actin as the housekeeping gene.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

After treatment, the cells were lysed in an ice-cold co-IP buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% NP-40, supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Cat. No. 04693132001), for 30 min. The cell homogenates were then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min, and the resulting supernatant was incubated overnight at 4 °C on a shaker with primary antibodies [anti-Flag (dilution ratio: 1:50; Abcam; Cat. No. ab205606), anti- USP2 (dilution ratio: 1:50; Proteintech; Cat. No. 10392-1-AP), anti-HA (dilution ratio: 1:50; Cell Signaling Technology; Cat. No. 3724), anti-SIRT2 (dilution ratio: 1:50; Abcam; Cat. No. ab211033), anti-TXNDC5 (dilution ratio: 1:50; Proteintech; Cat. No. 19834-1-AP), anti-TGFBR1 (dilution ratio: 1:50; Abcam; Cat. No. ab235578) or anti-IgG]. To ensure complete saturation of the primary antibodies, sufficient cell lysates were cultured and collected for IP. The mixture of antibodies and proteins was subsequently incubated with protein A/G-agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 78610) at 4 °C for 3 h. The beads were washed five to six times with cold IP buffer and resuspended in loading buffer. The cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were denatured in loading buffer at 95 °C for 5 min, and western blotting analysis was performed.

Protein–protein docking simulation

Protein-protein docking simulations between USP2 and TXNDC5, as well as USP2 and SIRT2, were performed using the HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). Protein sequences and their corresponding 3D structures (retrieved from UniProt; https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/) were preprocessed to remove water molecules and non-protein ligands; USP2 was set as the receptor, and TXNDC5/SIRT2 as ligands. Docking was run with default parameters (ab initio mode, generating the top 100 conformations), and the top ten models (ranked by binding energy) were selected.

Analysis of the conservation of lysine 447 in USP2

A gene panel of the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/) was used to download amino acid sequences of proteins from multiple species and subsequently compare sequence conservation between species using the UGENE software (version 39; the software can be downloaded from the following website: http://ugene.net/).

Bioinformatics methods predict lactylation of Lys447 in USP2

A DeepKla online tool (http://lin-group.cn/server/DeepKla/Serve.html) was used to predict which Lys site in USP2 could be lactylated, with low score values suggesting better results. The amino acid sequence of the protein in FASTA format was downloaded from UniProt and uploaded to the GPS website.

Promoter reporters and dual-luciferase assay

For TGF-β1-induced transcriptional reporter assays, HEK293T cells were transfected with one of the SBE4-Luc reporter plasmids. The SBE4-Luc reporter plasmid is a synthetic construct designed to monitor SMAD3-dependent transcriptional activity. It contains four tandem repeats of the SMAD3 binding element (SBE; consensus sequence: GTC TAGAC) upstream of the firefly luciferase gene, allowing quantification of SMAD3 signaling via luciferase enzyme activity. Transfection efficiency was normalized by cotransfection with the pRL-TK plasmid. Luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Cat. No. E1960, Madison, Wisconsin, USA).

Cell culture, transfection

The human proximal tubular epithelial cell line (HK2 cells) (Cat. No. CRL-2190) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (Cat. No. 10373017, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China). Mouse podocytes (MPC) (Cat. No. BNCC342021) and mouse renal glomerular endothelial cells (GEC) (Cat. No. BNCC360313) were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China), cultured in DMEM-H complete medium (Cat. No. BNCC338068, BeNa Culture Collection). Mouse renal fibroblasts (MF) (Cat. No. CP-M069, Procell Life Science&Technology, Wuhan, China) were cultured in mouse kidney fibroblast complete culture medium (Procell, Cat. No. CM-M069). All kinds of media were supplemented with 10% FBS (Cat. No. 10099158, Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 100 U·mL−1 of penicillin (Cat. No. 15140122, Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 100 mg•mL−1 of streptomycin (Cat. No. 15140122, Gibco, Grand Island, NY). All cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubator containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. Human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293) were purchased from ATCC and maintained in HyClone Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Cat. No. SH30022, Cytiva) with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution in a humidified incubator supplemented with 95% air/5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were regularly checked for mycoplasma in a standardized manner, by a qPCR test, performed under ISO17025 accreditation to ensure work was conducted in mycoplasma-negative cells.

Adenovirus particles used in the article were provided by GeneChem Company (Shanghai, China). Adenovirus overexpression vector plasmids used in this study were provided by Shandong Weizhen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., including two categories. The first category included adenovirus overexpression plasmids for wild-type and mutant human TXNDC5 and USP2 genes, with restriction enzyme sites AsisI/MluI, a 3Flag tag fused at the C-terminus of the vector, and an Amp resistance gene (resistance concentration: 100 μg/ml); for sequencing verification, the 5’-end primer (sequence: CGCAAATGGGCGGTAGGCGTG) and 3’-end primer (sequence: GGAAAGGACAGTGGGAGTG) were used. The second category was an adenovirus overexpression plasmid for the mouse Usp2 gene, with restriction enzyme sites AsisI/RsrII, a 3Flag tag fused at the C-terminus, and an Amp resistance gene (resistance concentration: 100 μg/ml); its sequencing verification used the 5’-end primer (sequence: TGAGCCAAGCAGACTTCCATGG) and 3’-end primer (sequence: TCGCCGGACACGCTGAACT). All plasmids were validated by next-generation full-length sequencing, with a concentration of 100–200 ng/μl, and stored at −20 °C. Adenovirus particles constructed from the above plasmids (adenovirus particles containing empty vectors served as controls) were used to transfect HK2 cells or renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs); after 6 h of transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium for continuous culture. Adenovirus was used to transfect HK2 cells or TECs for 6 h (adenovirus particles containing empty vectors were used as controls), and then the fresh medium was replaced for continued culture. The siRNA sequences targeting the respective genes were designed using siDirect 2.1 software (https://sidirect2.rnai.jp/), synthesized by Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), and contained standard chemical modifications: 2 phosphorothioate linkages at both the 5’ and 3’ ends of the sense and antisense strands. siRNA sequences are listed in Table S3. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Cat. No. L3000150, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Isolation of primary renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs)

Primary mouse renal tubular epithelial cells were isolated using an established protocol we previously published9. Briefly, the cortex of the kidneys from male mice was carefully dissected and chopped into small pieces. Then, 1 mg/ml of collagenase solution was applied and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min with gentle agitation. The digestion was terminated by FBS and then filtered sequentially. Fragmented tubules were collected and maintained in a renal epithelial cell basal medium using a growth kit. The medium was changed for the first time, after 72 h. The purity of the primary mouse renal tubular epithelial cells was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of SGLT1 (dilution ratio: 1:500; Cat. No. NBP2-20338, Novus).

Fe2+ Detection

To detect intracellular Fe(II), FerroOrange (Cat. No. F374, Dojindo, Japan) was used based on the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the harvested cells were washed with HBSS three times after removing the culture medium under treatment conditions and then co-incubated with 1 μmol/L FerroOrange working solution at 37 °C for 30 min. Fluorescence images were captured by a fluorospectrophotometer at a 543 nm excitation wavelength and a 580 nm emission wavelength. Analysis of Fe(II) was performed by measuring the intensity of fluorescence for each treatment condition.

Immunofluorescent staining of cells

After treatment, cells was fixed for 15 min using fresh, methanol-free 4% formaldehyde, and then, rinsed thrice with PBS for 5 min each. After blocking with goat serum for 30 min, the cells were incubated with primary antibody against SMAD3 (dilution ratio: 1:500; Cat. No. F374, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight. Alexa Fluor®488 Rabbit anti-Goat antibodies against murine IgG (dilution ratio: 1:400; Cat# A-11078, Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) were included as secondary antibodies. As negative controls, the primary antibodies were exchanged for nonimmune serum from the same species. The samples were counterstained with DAPI for 15 min. The sections were sealed with a cover glass, and the specimens were examined using the appropriate excitation wavelength. Images were captured and processed with a Leica microscope (Wetzlar, Germany).

Ubiquitin-rhodamine G (Ub-RhoG) cleavage assay

For the ubiquitin-rhodamine G (Ub-RhoG) cleavage assay, recombinant Ub-RhoG was used as the fluorogenic substrate at a final concentration of 50 nM. Purified recombinant USP2 wild-type (WT), USP2 K447R (novel mutant), and USP2 C276A (catalytically inactive mutant) were each added to the reaction system at an identical final concentration of 200 nM to ensure comparative validity. The assay was conducted at 37 °C, and fluorescence intensity (reflecting the release of free rhodamine G upon Ub-RhoG cleavage by active DUBs) was measured at an excitation wavelength of 492 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm at 20-min intervals over a total of 1 h (0, 20, 40, and 60 min). Technical triplicates were performed for each group, and a no-enzyme control was included to correct for background fluorescence.

ROS and ferroptosis analyses

The researchers employed several commercially available kits and probes, meticulously following the manufacturers’ instructions. The MDA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. MAK568-1KT) was utilized to measure malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined using the SOD kit (Cat. No. 19160-1KT-F, Sigma-Aldrich). The intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels were quantified using a commercial Glutathione Assay Kit (Cat. NO. CS0260, Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocol. For detecting intracellular iron levels, the FerroOrange probe (Cat. No. F374, Dojindo, Shanghai, China) was implemented. Lipid peroxidation was evaluated with the BODIPY™ 581/591 C11 probe (Cat. No. M7514, Thermo Fisher Scientific). These kits are all commercially available products with clear instructions and are widely used in the relevant research field. We have strictly adhered to the manufacturer’s instructions during the experiment process and have also ensured that all necessary controls were in place.

Iron content

The tissue iron assay kit (Cat. No. A039-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China) was used for iron content measurement. In accordance with the protocol, the kidney tissues were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by the addition of the iron color-developing agent. After the vortex, the mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 1500 ×g for 10 min. Finally, the absorbance was determined at a wavelength of 520 nm.

Proteomics analysis

The protein analysis methods in this project involved several key steps. First, samples were processed by adding lysis buffer (1.5% SDS/100 mM Tris-Cl), homogenized, and centrifuged to obtain supernatants. Proteins were precipitated with acetone, then resuspended in 8 M urea/100 mM Tris-Cl. Reduction was conducted with DTT at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by alkylation with IAA in the dark. After determining protein concentration via Bradford assay, samples were diluted to <2 M urea, digested with trypsin (enzyme:protein = 1:50) overnight, and enzyme digestion was terminated with TFA. Peptides were desalted using Sep-Pak C18 and freeze-stored. For TMT labeling, equal protein amounts were labeled according to the manufacturer’s instructions, mixed, desalted, and fractionated into 15 components by high pH reverse-phase chromatography. Mass spectrometry was performed on a Q Exactive HF coupled with UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano, using a 90-min gradient (Mobile Phase A: 0.1% formic acid, 3% DMSO; Mobile Phase B: 0.1% formic acid, 3% DMSO, 80% ACN) at 300 nL/min. Data were acquired in DDA mode (MS1: R = 60 K, 350–1500 m/z; MS/MS: R = 45 K, 20 scans). MaxQuant (V1.6.6) was used for database searching (Uniprot Mouse), with FDR < 1% for filtering. Functional annotations (GO, KEGG, COG) and enrichment analyses were conducted via eggNOG-mapper, and protein–protein interaction networks were analyzed using STRING.

IPA analysis

ENRICHR, an enrichment analysis web tool, was used for gene signaling pathways and ontology analysis (https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr/)35. The ggplot2 and ggpubr package of R software were used for visualization of enrichment results36,37, including terms, gene ratio, gene counts, P value, etc.

The analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing of the human kidney

To analyze the expression of USP2 in the Healthy Human Adult Kidney using the Kidney Interactive Transcriptomics (KIT) website, first visit [https://humphreyslab.com/SingleCell/]. Locate the gene search bar on the homepage, enter “USP2”, and select the “Healthy Adult Human Kidney - Epithelia” or “Healthy Adult Human Kidney—Complete” dataset from the dropdown menu, ensuring the correct study by Wu and colleagues (JASN 2018 or Cell Stem Cell 2018) is chosen. Once the dataset is selected, the platform will generate visualizations such as violin plots or dot plots displaying USP2 expression across various cell types, including proximal tubule, podocyte, and endothelia. Users can further explore cell-type-specific expression by filtering on specific populations and downloading the data or images for documentation, remembering to cite the relevant original publication for the dataset used.

Statistics and reproducibility

For animal experiments, the sample size was 6 independent mice per group. For in vitro cellular experiments, all analyses were independently repeated at least three times, with each treatment group including at least three independent culture wells. Reproducibility, including biological independent sample sizes and replicates, is stated in each figure legend. Each value was presented as the mean ± SD. All raw data were initially subjected to a normal distribution and analysis by one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) nonparametric test using SPSS 22.0 software, and results confirmed that all data conformed to a normal distribution, thus parametric tests were applied. For animal and cellular experiments, a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test was performed to compare the two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to compare more than two groups. To avoid bias, all statistical analyses were performed blindly. Qualitative experiments (e.g., representative immunofluorescence images and Western blot bands) were independently repeated at least three times with consistent results. Statistical significance was indicated at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

SIRT2 regulates TGFBR1 ubiquitination and degradation through USP2

In our prior publications, we established that SIRT2 exerts inhibitory effects on the TGFβ signaling cascade, chiefly through the deacetylation and subsequent inactivation of SMAD2/3 in renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs), which play a pivotal role in the progression of renal fibrosis11,38. Expanding upon these insights, our current research delves deeper into the multifaceted roles of SIRT2. With the treatment of protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) and TGF-β1, Sirt2 overexpression (S2OE) promoted the degradation of TGFBR1, but not TGFBR2 (Fig. S1A). To investigate the role of proteasome-, lysosome-, or autophagosome-dependent pathways in the reduction of TGFBR1 protein induced by SIRT2, the inhibitory effects were evaluated using proteasome inhibitor MG132, lysosome inhibitor NH4Cl, and autophagosome inhibitor 3-MA. Only MG132 repressed the downregulation of TGFBR1 protein mediated by S2OE (Fig. S1B). Consistently, S2OE diminished TGFBR1 expression, while S2KO elevated it, in response to TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. S1C). However, there is no direct interaction between SIRT2 and TGFBR1 with or without TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. S1D), suggesting that other molecules are involved in the regulation of TGFBR1 protein ubiquitination and stability mediated by SIRT2.

Given the substantially larger size of the E3 ubiquitin-ligase family (over 600 members) compared to the more manageable number of USPs (~50 members), we focused on USPs to explore their involvement in regulating TGFBR1 in Sirt2 knockout (S2KO) cells. To investigate the involvement of USPs in TGFBR1 in Sirt2 knockout (S2KO) cells, we selected 26 representative USPs and conducted unbiased siRNA screening by monitoring the levels of TGFBR1 (mRNA knockdown efficiencies are shown in Table S4). Among those tested, we focused on USP2 because its siRNA-mediated depletion markedly reduced the abundance of TGFBR1 that was induced by S2KO (Fig. S1E). We, therefore, determine whether USP2 could regulate the protein level of TGFBR1 in TECs. In Usp2 KO TECs, there is less TGFBR1 protein when compared to those in WT TECs under TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. S1F upper panel), while USP2 OE increased the protein level of TGFBR1 in TECs (Fig. S1F bottom panel). Notably, we found the regulatory effect of USP2 on TGFBR1 to be very weak under conditions without TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. S1F), suggesting that the presence of TGFβ1 is essential for the USP2-mediated stabilization of TGFBR1. Furthermore, MG132 blocked Usp2 KO-mediated downregulation of the TGFBR1 protein level in TECs (Fig. S1G). Consistent with this, the TGFBR1 was downregulated following the knockdown of USP2 (Fig. S1H). Next, we found that ML364, a small molecule inhibitor of USP2, decreased the protein level of TGFBR1 in TECs (Fig. S1I). WT USP2 OE, but not USP2 C276A (an enzyme activity dead mutation), increased the protein level of TGFBR1 (Fig. S1J).

To determine whether USP2 is required for SIRT2 to regulate the protein level of TGFBR1, Usp2 siRNA (siUsp2) or control siRNA was used to transfect WT or S2KO TECs. USP2 knockdown dramatically repressed the upregulation induced by S2KO of TGFBR1 protein (Fig. S1K). Consistent with this, transfection with adeno-associated virus expressing short hairpin RNA of Usp2 (AAV-shUsp2) decreased the protein level of TGFBR1 in the kidney of WT mice compared to those transfected with AAV-Ctrl (Fig. S1L). Additionally, S2KO increased the protein level of TGFBR1 in the kidney of mice transfected with AAV-Ctrl, but not with AAV-shUsp2 (Fig. S1L). Taken together, these results suggest that USP2 is required for the regulation of SIRT2 on the degradation of TGFBR1.

USP2 deubiquitinates and stabilizes TXNDC5 to regulate TGFβ/SMAD3-induced transcriptional activity and gene expression

USP2 is responsible for the deubiquitination of proteins. Hence, proteomics sequencing was performed in the kidney from WT and Usp2 KO mice following UUO surgery. Differential protein expression analyses identified 226 significantly upregulated and 129 significantly downregulated proteins in the kidneys of Usp2 KO mice compared to WT mice. Notably, ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of downregulated protein revealed that the “TGFβ signaling” and “epithelial- mesenchymal transition” were the top pathway affected by Usp2 KO (Fig. 1A). A recent study identified that thioredoxin domain containing 5 (TXNDC5) mediated its profibrogenic effects by enforcing TGFβ signaling activity through posttranslational stabilization and upregulation of TGFBR1 in kidney fibroblasts39. Among all DEGs in the “TGFβ signaling” pathway, TXNDC5 showed the most significant downregulation in the kidneys of Usp2 KO mice compared to WT mice, as determined by RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 1B). Next, we determined whether Usp2 KO regulated the half-life of TXNDC5 in TECs. The half-life of TXNDC5 was shortened in Usp2 KO TECs compared to WT TECs (Fig. 1C). Moreover, MG132 remarkably inhibited the degradation of TXNDC5 in Usp2 KO TECs (Fig. 1D). USP2 failed to bind TXNDC5 without TGF-β1 treatment (Fig. S1M), whereas their interaction was evident upon TGF-β stimulation (Fig. 1E, F). WT USP2 transfection, but not USP2 C276A, induced the protein level of TXNDC5 and decreased the TXNDC5 ubiquitination (Fig. 1G). On the basis of the GPS database (http://cplm.biocuckoo.cn/), TXNDC5 has four ubiquitination sites, including K118, K143, K150, and K244. Hence, we mutated all 4 K to arginine (R), which mimicked the deubiquitination of the protein. We found that only the K150R mutation evident upregulated the protein level of TXNDC5 (Fig. 1I). In line with this, TXNDC5 K150R mutation remarkably reduced the TXNDC5 ubiquitination, and USP2 knockdown did not increase TXNDC5 ubiquitination (Fig. 1J). Molecular docking simulations showed TXNDC5 K150 at the contact surface between USP2 and TXNDC5 (Fig. 1K). These results implied that the K150 at TXNDC5 may be a major site for deubiquitination regulated by USP2. Next, we aimed to investigate whether TXNDC5 is necessary for USP2 regulated the ubiquitination of TGFBR1. When TXNDC5 was already knocked down, USP2 overexpression did not induce the protein level of TGFBR1 or the phosphorylation of SMAD3, nor did it reduce the ubiquitination of TGFBR1 (Fig. 1L). Consistently, when TXNDC5 was overexpressed, USP2 knockout failed to reduce the protein level of TGFBR1 and the phosphorylation of SMAD3, nor did it lead to an increase in the ubiquitination level of TGFBR1 (Fig. 1M upper and S2A). To verify the consistency of our results in vivo, we used AAV expressing Txndc5 (AAV-Txndc5) to transfect WT or Usp2 KO mice. Usp2 KO reduced the protein of TGFBR1 in the kidney compared to those in WT mice, and this downregulation was blocked by AAV-Txndc5 transfection (Fig. 1M bottom and S2A). TXNDC5 truncation mutants revealed that the A1-A169, which contains the Thioredoxin 1 (T1) domain, predominantly interacts with USP2, whereas the T2 and T3 regions exhibit minimal binding affinity (Fig. 1N).

A The ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA). Analysis of proteomics in the kidney of WT and U2KO mice. B Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in the kidney from the kidneys of U2KO and WT mice (P < 0.05). Genes related to the TGFβ signaling pathways are labeled. C, D WT or U2KO TECs incubated with CHX (C) or MG132 (D) as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting was performed using the indicated antibodies. E Co-IP assays were performed using lysates from WT TECs stimulated with TGF-β1, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. F WT TECs transfected with Ad HA-Txndc5 and/or Ad-Flag Usp2 as indicated, and then subjected to TGF-β1 stimulation. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. G HK2 cells transfected with Ad-Flag USP2 WT (Flag-WT) or Ad-Flag USP2 C276A. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-TXNDC5 antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. H, I The database provides TXNDC5 posttranslational modification of individual sites (H). HK2 or shUSP2 cells transfected with Ad-Flag TXNDC5 WT, K118R, K143R, K150R, and K244R as indicated, and the total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies (I). J HK2 transfected with siRNA USP2 (siUSP2), Ad-Flag TXNDC5 WT, or Ad-Flag TXNDC5 K150R as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. K USP2-TXNDC5 docking with the HDOCK server. High magnification of the boxed areas is presented on the left. The arrow indicates K150 of the TXNDC5 protein. L WT TECs were transfected with Ad-Usp2 and/or siTxndc5 as indicated, and the total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. M HK2 transfected with Ad-Tnxdc5 and/or siUsp2 as indicated, and the total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies (left). WT or S2KO mice were transfected with AAV-ctrl or AAV-shTxndc5, and then subjected to UUO surgery. Total cell lysates from the kidney of mice were prepared, and western blotting was performed using the indicated antibodies (right). N Schematic illustration of TXNDC5 deletion mutants (left). The numbers indicate the amino acid positions. HA- TXNDC5 deletion mutants were coexpressed with Flag-USP2 in HEK293T cells. O–S HK2 cells were transfected with Ad-Null or Ad-USP2 for 24 h, and treated with or without 2 ng/ml TGFβ1 for the indicated times. Representative images of SMAD3 immunofluorescence staining are shown in (O; Scale bar = 25 μm), and densitometry quantification of nuclear levels of SMAD3 are shown in (P; elements in this figure were created with BioRender.com). Q Western blot analyses of SMAD3 in the fractions extracted from TECs. R 3TP-Lux luciferase activity assay in HEK293T cells after transfection of the 3TP-Lux plasmid, a renilla plasmid, and Ad-null or Ad-USP2 for 24 h, followed by the treatment with or without 2 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 16 h. Relative luciferase activity is presented as folds of that in the cells with transfection of Ad-null (n = 5). S HK2 were transfected with Ad-null or AdUSP2 for 24 h, and treated with or without 2 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 24 h. Western blot analysis of TGFBR1, USP2, SMAD3, pSMAD3, and Tubulin in HK2 cells (left). For all panels, data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction test.

Next, we investigated whether USP2 modulates TGFβ signaling. Altered expression of USP2 did not change the expression levels of SMAD3, a key signaling molecule for TGFβ signaling (Fig. S2C, F). USP2 OE in HK2 cells (human TECs) promoted the TGFβ1-induced nucleus accumulation and transcriptional activity of SMAD3 (Fig. 1O–R). In agreement with this, USP2 OE enhanced the protein level of TGFBR1 and phospho-SMAD3 (pSMAD3), and the expression of COL1A1, COL1A2, SERPINE1, and SMAD7, the prototypic TGFβ signaling target genes, under TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. 1S and S2B). Furthermore, Usp2 OE in WT TECs resulted in increased protein levels of TGFBR1, pSMAD3, CTGF, and α-SMA, and induced mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling target genes (Col3a1, Col1a1, Col1a2, Serpine1, Smad7, and Smurf1) (Fig. S2C–E). Consistently, Usp2 KO TECs decreased the protein level of TGFBR1 and pSMAD3, and repressed mRNA levels of TGFβ signaling target genes compared to WT TECs (Fig. S2F). Thus, we demonstrated that USP2 promotes TGFβ/SMAD3 signaling transduction. We also found that knocking down Txndc5 inhibited the nuclear accumulation and phosphorylation of SMAD3, as well as the expression of TGFβ target genes, which were induced by USP2 overexpression (Fig. S2G–K). Together, our findings suggested that TXNDC5 is a vital downstream target for the degradation of TGFBR1, regulated by USP2.

USP2 deubiquitinates and stabilizes TFRC to promote TGFβ-induced ferroptosis

Except “TGFβ signaling”, IPA also revealed that the “mTORC1 signaling” was among the top pathways affected by Usp2 knockout (Fig. 2A). Among these genes enriched in this pathway, TFRC ranked second in fold change (fold change = −0.32, P < 0.05), implying its notable role in response to Usp2 deletion. Notably, while TFRC is not a direct component of the mTORC1 core complex, its dysregulation may indirectly impact pathway activity through iron-dependent mechanisms. Additionally, we observed that the ferroptosis-related signaling pathways “reactive oxygen species” and “fatty acid metabolism” are both present in the IPA analysis. Next, we carried out experiments in vitro to further corroborate the role of USP2 in the progression of TGFβ1-induced ferroptosis. The results showed that the protein levels of ACSL4 and HMOX1 were significantly increased with TGFβ1 stimulation, whereas GPX4 was decreased (Fig. 2B). In addition, TGFβ1 suppressed cell viability, upregulated malondialdehyde (MDA), but decreased superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and Fe2+ levels (Fig. 2C). Notably, these changes induced by TGFβ1 were restrained by Usp2 knockdown and aggravated by Usp2 OE (Fig. 2B–E). Furthermore, to conduct lipid ROS staining, BODIPY 581/591 C11, a lipid peroxidation probe recognized as the gold standard for the presence of ferroptosis, was performed in TECs. The results showed that TGFβ1 stimulation increased the level of oxidized lipids, as indicated by intensified green fluorescence (Fig. 2F). This effect was counteracted by knockdown of Usp2, while Usp2 OE further intensified the fluorescence, indicating a heightened level of lipid oxidation. Notably, DFO treatment effectively blocked USP2-mediated changes in these ferroptosis indicators under TGF-β1 stimulation, regardless of whether Usp2 was overexpressed or knocked down (Fig. S3A–D). These results strongly support that USP2 regulates ferroptosis under TGF-β1 stimulation. Collectively, these findings revealed that USP2 exacerbates TGFβ1-induced ferroptosis.

A The IPA Analysis of proteomics in the kidney of WT and U2KO mice. B, C WT TECs transfected with siCtrl or siUsp2 as indicated in the present with or without TGFβ1. B The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting was performed using the indicated antibodies. C MDA, SOD, GSH, and Fe2+ levels in cell homogenates were detected by a commercial kit (n = 5). D, E WT TECs transfected with Ad-null or AdUsp2 as indicated in the presence or absence of TGFβ1. D The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. E MDA, SOD, GSH, and Fe2+ levels in cell homogenates were detected by commercial kit (n = 5). F Representative images of BODIPY 581/591 C11 staining. Scale bar = 50 μm. G WT TECs transfected with AdUsp2 and siTfrc as indicated upon TGFβ1 stimulation. (Left) The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (Right) MDA, SOD, GSH, and Fe2+ levels in cell homogenates were detected by a commercial kit (n = 5). H WT TECs transfected with siUsp2 and AdTfrc as indicated upon TGFβ1 stimulation. (Left) The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (Right) MDA, SOD, GSH, and Fe2+ levels in cell homogenates were detected by a commercial kit (n = 5). I, J WT or U2KO TECs incubated with CHX (I) or MG132 (J) as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. K Co-IP assays were performed using lysates from WT TECs stimulated with TGF-β1, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. L WT TECs transfected with Ad HA-Tfrc and/or Ad-Flag Usp2 as indicated, and then subjected to TGF-β1 stimulation. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. M HK2 cells transfected with Ad-Flag USP2 WT (Flag-WT) or Ad-Flag USP2 C276A. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-TFRC antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. N The database provides TXNDC5 posttranslational modification of individual sites (left). HK2 cells transfected with shUSP2, Ad-Flag TFRC WT, K39R and K160R as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). O HK2 cells transfected with siRNA USP2 (siUSP2), Ad-Flag TFRC WT, or Ad-Flag TFRC K39R as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. P Schematic illustration of TFRC deletion mutants (left). The numbers indicate the amino acid positions. HA- TFRC deletion mutants were coexpressed with Flag-USP2 in HEK293T cells (right). For all panels, data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction test.

Next, we aimed to explore the role of TFRC in USP2-mediated regulation of TGFβ1-induced ferroptosis. Under TGFβ1 stimulation, the impact of USP2 OE on ferroptosis-related markers was almost blocked by TFRC knockdown (Fig. 2G). Consistently, knockdown of Usp2 did not mitigate the alterations in ferroptosis-related markers induced by TFRC OE upon TGFβ1 (Fig. 2H). Next, we found that Usp2 KO shortened the half-life of TFRC (Fig. 2I). MG132 remarkably inhibited the degradation of TFRC in Usp2 KO TECs (Fig. 2J). Analogous to TXNDC5, USP2 failed to bind TFRC without TGF-β1 treatment, whereas their interaction was evident upon TGF-β stimulation (Fig. 2K, L). HK2 cells transfected with WT USP2, but not the catalytically inactive USP2 C276A mutant, increased the protein level of TFRC and decreased TFRC ubiquitination (Fig. 2M). Previous studies have indicated that K39 and K160 on TFRC may be targets for deubiquitination by USP240 (Fig. 2N left panel). Hence, we mutated these 2K to R, which mimicked the deubiquitination of the protein. We found that only the K39R mutation evident upregulated TFRC protein level (Fig. 2N right panel). In line with this, the TXNDC5 K39R mutation remarkably reduced TFRC ubiquitination, and USP2 knockdown did not increase TFRC K39R ubiquitination (Fig. 2O). TFRC truncation mutants revealed that the A1-A200 region interacts with USP2 (Fig. 2P). These results implied that the K39 at TFRC may be a major site for deubiquitination regulated by USP2.

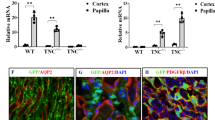

Targeted TECs USP2 OE aggravates kidney fibrosis and ferroptosis in male UUO mice

To identify the cellular localization of USP2 in the kidney, we analyzed its expression in primary renal parenchymal cells (mouse podocytes [MPCs], glomerular endothelial cells [GECs], kidney fibroblasts [KFs], and TECs) using RT-PCR and Western blotting. USP2 was predominantly expressed in TECs, with significantly lower basal levels detected in MPCs, GECs, and KFs (Fig. 3A). This TEC-specific expression pattern was further corroborated by single-cell RNA sequencing data from human kidneys, which localized USP2 to proximal tubule (PT), loop of Henle (LH), and distal convoluted tubule (DCT) cells41 (Fig. 3B). To directly assess the functional impact of TEC-specific Usp2 OE in vivo, we delivered Usp2 to WT mice via an AAV9 vector under the control of the tubule-specific Ksp-cadherin promoter (AAV9-Ksp-Usp2), with AAV9-Ksp-null as control. In the UUO model, Usp2 OE in TECs led to upregulation of TFRC and TXNDC5 protein levels, concomitant with reduced ubiquitination of these targets (Fig. 3C). This was associated with a marked exacerbation of UUO-induced renal fibrosis (Fig. 3D). Molecular analysis revealed that, compared to controls, Usp2 OE mice exhibited enhanced induction of fibrotic (CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, and COL3A1) and ferroptotic (HMOX1) markers, alongside further suppression of GPX4 following UUO (Fig. 3E). Consistently, the more pronounced transcriptional upregulation of profibrotic genes (Col1a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, Acta2, Col3a1) and kidney injury markers (Ngal, Kim-1) was observed in Usp2 OE kidneys post-injury (Fig. 3F). Usp2 OE also accentuated UUO-induced iron accumulation and disrupted redox homeostasis, as evidenced by increased MDA levels, reduced SOD activity, and a diminished GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 3G, H). Finally, TUNEL staining confirmed a significant increase in renal cell death in Usp2 OE mice compared to controls (Fig. 3I). Collectively, these data demonstrate that targeted Usp2 OE in TECs exacerbates UUO-induced renal fibrosis and ferroptosis, likely through the dysregulation of TFRC and TXNDC5 ubiquitination and subsequent impairment of iron and redox metabolism.

A RT-PCR (n = 5) and western blot analysis (n = 3) of the expression of USP2 in selected mouse renal cells, including mouse podocytes (MPC), rat glomerular endothelial cells (GEC), mouse TECs, and mouse fibroblast (MF). B Single-cell sequencing results show that USP2 is predominantly expressed in renal tubular cells. C–I Control (AAV-Ctrl) or Usp2 OE (AAV-Ksp-Usp2) mice were randomly assigned to sham or UUO surgery according to an established protocol (n = 6). C Total cell lysates from the kidney of mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-TFRC or anti-TXNDC5 antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. D Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining and Sirius red in kidneys from mice (scale bar, 100 μm). E Western blot analysis of the expression of CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, GPX4, HMOX1, and Tubulin. F The mRNA level of Col1a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, Acta2, Col3a1, Ngal, and Kim-1 in the kidney of mice. G, H The level of Iron, MDA, SOD, GSH, and the ratio of GSSG in renal homogenate. I Representative TUNEL staining and quantification (three field per mice; n = 6) of apoptotic cells in kidney sections from mice (Scale bar = 20 μm). For all panels, data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction test.

Globally and TECs-specific deletion of Usp2 alleviates the kidney fibrosis and ferroptosis of male mice

To determine the role of USP2 in kidney fibrosis, we subjected WT and global Usp2 KO mice to UUO. Histological analysis using Sirius Red and Masson’s Trichrome staining revealed extensive fibrosis in WT kidneys post-UUO, which was significantly attenuated in Usp2 KO mice (Fig. S4A). Corroborating these findings, immunoblot analysis of whole-kidney lysates demonstrated that UUO-induced upregulation of fibrotic (CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, and COL3A1) and ferroptotic (HMOX1) markers, alongside downregulation of GPX4, was more prominent in WT mice relative to KO littermates (Fig. S4B). Consistently, the induction of profibrotic genes (Col1a1, Col3a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, and Acta2) and kidney injury markers (Ngal, Kim-1) following UUO was blunted in Usp2 KO mice (Fig. S4C, D). At the molecular level, Usp2 deletion mitigated UUO-induced iron accumulation (Fig. S4E). It also rescued the UUO-mediated reduction in GSH levels and GSH/GSSG ratio, while decreasing MDA levels and increasing SOD activity, indicating a suppressed ferroptotic response (Fig. S4E). Furthermore, TUNEL staining revealed a significant reduction in kidney cell death in Usp2 KO mice compared to WT controls after UUO (Fig. S4F). Mechanistically, we found that Usp2 deletion was associated with decreased protein levels of TFRC and TXNDC5, alongside enhanced ubiquitination of these targets in the kidneys post-UUO (Fig. S4G, H). Notably, USP2 lactylation was induced in the kidneys following injury (Fig. S4H). To dissect the cell-type specificity of these effects, we generated TEC-specific Usp2 knockout (U2TKO) mice by crossing Usp2flox/flox with Ksp-Cre mice. U2TKO mice phenocopied the global KO mice, showing attenuated renal fibrosis and ferroptosis, as well as increased ubiquitination of TFRC and TXNDC5 in response to UUO (Fig. 4A–H). Collectively, these results demonstrate that USP2 deletion, either globally or specifically in TECs, protects against UUO-induced renal fibrosis and ferroptosis, likely through regulating the ubiquitination of TFRC and TXNDC5, and possibly via its own lactylation.

A–G WT or U2TKO mice were randomly assigned to sham or UUO surgery according to an established protocol. Kidney samples were obtained from mice on day 10 post-UUO or sham surgery (n = 6 per group). A Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining and Sirius red in kidneys from mice (scale bar = 100 μm). B Western blot analysis of the expression of USP2, CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, GPX4, HMOX1, and Tubulin. C, D The mRNA level of Col1a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, Acta2, Col3a1, Ngal, and Kim-1. E The level of Iron, MDA, SOD, GSH, and the ratio of GSSG in renal homogenate (n = 6). F Representative TUNEL staining and quantification (3 field per mice; n = 6) of apoptotic cells in kidney sections from mice (Scale bar = 20 μm). G, H Total cells lysates from kidney of mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-USP2, anti-TFRC, or anti-TXNDC5 antibody, and western blotting using indicated antibodies. For all panels, data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction test.

USP2 is lactylated at K447 under TGFβ1 stimulation and which is required for the activation of USP2-mediated TGFβ1

We found that the interaction between SIRT2 and USP2, as determined by both endogenous and exogenous co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), was present under TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. 5A). Since SIRT2 is a deacetylation and delactylation11,42 enzyme, we then measured changes in the posttranslational modification (PTM) of USP2. The analysis revealed that the lactylation level of USP2 was significantly downregulated after SIRT2 OE under TGFβ1 stimulation, but not the acetylation level (Fig. 5B). DeepKla, an attention mechanism-based deep neural network for protein lysine lactylation site prediction (http://lin-group.cn/server/DeepKla/Serve.html), was used to predict the lactylation site of USP2, and the results showed that there are eight major lactylation sites on USP2. We mutated all eight lysine (K) to arginine (R), mimicking the delactylation of protein. The K447R evident mutation significantly reduced the lactylation of USP2 under TGFβ1 stimulation compared to USP2 WT, USP2 K139R, USP2 K205R, USP2 K241R, K340R, K420R, K464R, and K473R (Fig. 5C). Conservation analysis of USP2 indicated that K447 is a highly conserved site, ranging from Canis lupus familiaris to Homo sapiens (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, K447 is located in the Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolase (UCH) domain of USP2, which is the core catalytic region of USP2. Lactic acid content was upregulated in the TECs under TGFβ1 stimulation10. Theoretically, the higher the lactate content, the more lactic acid is available for protein lactylation43. We then confirmed a lactylation response to TGFβ1. TGFβ1 treatment markedly increased the lactylation level of USP2 (Fig. 5E). Consistently, the lactylation level of USP2 was increased in the kidney of mice following injury (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, USP2 K447R blocked the TGFβ1-mediated upregulation of USP2 lactylation level (Fig. 5G), suggesting that K447 is an essential lactylation site in TGFβ1 stimulation. Next, we analyzed the potential impact of K447 lactylation on USP2. USP2 WT transfection promoted TGFβ1-induced nuclear localization of SMAD3, and increased SMAD3-mediated transcriptional activity, the protein level of TGFBR1, and the mRNA level of TGFβ signaling target genes (COL1A1, COL1A2, SERPINE1, and SMAD7), while USP2 K447R abolished these effects (Fig. 5H–L). Moreover, we discovered that USP2 OE, but not its K447R mutant, led to a decrease in GPX4 mRNA level and a reduction in both GSH and SOD levels, while simultaneously causing an upregulation in ACSL4 mRNA levels and an increase in MDA content under TGF-β1 stimulation (Fig. S3E, F). Together, TGFβ1 induced lactylation of USP2 at K447.

A Total cell lysates from WT TECs subjected to Co-IP with anti-SIRT2 or anti-USP2 antibody, and western blotting using indicated antibodies (left). HK2 cells were transfected with Ad HA-SIRT2 and/or Ad-Flag USP2 as indicated. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies (right). B WT TECs transfected with Ad-null or Ad-Sirt2 as indicated, followed by TGF-β1 stimulation. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-USP2 antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. C HK2 cells transfected with Ad-Flag Usp2 WT, K139R, K205R, K241R, K340R, K420R, K447R, K464R, or K473R as indicated. The total cell lysates were prepared and western blotting using indicated antibodies. D The conservation of USP2 K447 in different species. E WT TECs transfected with Ad-Flag Usp2 WT and then incubated with TGFβ1 for the indicated time. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. F Total cells lysates from the kidney of UUO or FA-treated mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. G WT TECs transfected with Ad-Flag Usp2 WT or Ad-Flag Usp2 K447R in the presence or absence of TGFβ1. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. H–L WT TECs transfected with Ad-null, Ad-Usp2 WT, and Ad-Usp2 K447R under TGFβ1 stimulation was indicated. Representative images of SMAD3 immunofluorescence staining are shown in (H; (Scale bar = 25 μm)), and densitometry quantification of nuclear levels of SMAD2 are shown in (I). J Western blot analyses of SMAD3 in the fractions extracted from TECs. K 3TP-Lux luciferase activity assay in HEK293T cells after transfection of the 3TP-Lux plasmid, a renilla plasmid, and Ad-null, Ad-USP2, or Ad-USP2 K447R for 24 h, followed by the treatment with or without 2 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 16 h. Relative luciferase activity is presented as folds of that in the cells with transfection of Ad-null (n = 5). L Western blot analysis of TGFBR1, USP2, SMAD3, pSMAD3, and Tubulin in TECs (left). The mRNA level of Col1a1, Col1a2, Serpine1, and Smad7 as determined by qPCR (right; n = 5). M WT TECs transfected with Ad-Flag-Usp2 and Ad-Sirt2 or siSirt2 in the presence or absence of TGFβ1 as indicated. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. N WT TECs transfected with Ad HA-Sirt2 or Ad-Flag-Usp2 under TGFβ1 stimulation as indicated. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-HA antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. O WT TECs transfected with Ad-Flag-Usp2 WT, Ad-Flag-Usp2 K447R, or Ad-Sirt2 under TGFβ1 stimulation as indicated. Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. P HK2 cells transfected with Ad-Flag-USP2 WT, Ad-Flag-SIRT2 H187Y, or Ad HA-SIRT2 under TGFβ1 stimulation as indicated (Elements in this figure were created with BioRender.com). Total cell lysates were subjected to Co-IP with anti-Flag antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. Q USP2-SIRT2 docking with the HDOCK server. High magnification of the boxed areas is presented on the left. The arrow indicates K447 of the USP2 protein. R Total cells lysates from the kidney of UUO and FA-treated WT or S2KO mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-USP2 antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. For all panels, data were presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction test.

SIRT2 delactylates USP2 K447 and inhibits the activity of USP2

The above data confirmed that TGFβ1 promoted the lactylation of USP2 K447 while SIRT2 OE decreased it. Consequently, we explored whether SIRT2 mediates the delactylation of USP2 at lysine 447. Firstly, TGFβ1-induced lactylation of USP2 was markedly inhibited by SIRT2 OE, and promoted by SIRT2 knockdown (Fig. 5M). To explore and confirm whether TGFβ1 influences the interaction between USP2 and SIRT2, we detected the binding of USP2 to SIRT2 under TGFβ1 stimulation (Fig. 5N). Compared to the WT USP2, USP2 K447R transfection suppressed TGFβ1-mediated upregulation of USP2 lactylation, which was not further affected by SIRT2 OE (Fig. 5O). SIRT2 H187Y (an enzyme dead mutant) OE did not reduce the lactylation of USP2 under TGFβ1 stimulation, while WT SIRT2 OE remarkably decreased the lactylation level of USP2 (Fig. 5P). Molecular docking simulations showed USP2 K447 at the contact surface between USP2 and SIRT2 (Fig. 5Q). Furthermore, the lactylation level of USP2 was increased in the kidney of Sirt2 KO mice following injury compared to those in WT mice (Fig. 5R). Above all, these results indicate that SIRT2 delactylates USP2 at K447. Moreover, using the ubiquitin-rhodamine G (Ub-RhoG) cleavage assay, we observed that purified recombinant USP2 K447R and USP2 C276A both showed drastically lower fluorescence intensity (indicating negligible catalytic activity) compared to WT USP2, with no significant difference in fluorescence intensity between the two mutants at any time point (Fig. S3G). Furthermore, we found that AAV-Ksp-Usp2 transfection reversed the reduction of kidney fibrosis and ferroptosis in Usp2 KO UUO mice. In addition, we found that AAV-Ksp-Usp2 transfection, but not AAV-Ksp-Usp2 K447R, reversed the reduction in renal fibrosis and ferroptosis induced by Usp2 KO in UUO mice (Fig. 6A–G). These results demonstrate that interventional Usp2 OE in renal TECs exacerbates kidney fibrosis and ferroptosis induced by UUO surgery.

A–H WT and Usp2 KO (U2KO) mice were transfected with AAV-ctrl, AAV-Ksp-WT Usp2, and AAV-Ksp-Usp2 K447R, and after 2 weeks of transfection, mice were randomly assigned to UUO surgery according to an established protocol (n = 6). A Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining and Sirius red in kidneys from mice (scale bar, 100 μm). B Western blot analysis of the expression of CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, GPX4, HMOX1, and Tubulin. C, D The mRNA level of Col1a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, Acta2, Col3a1, Ngal, and Kim-1 in the kidney of mice. E The level of Iron, MDA, SOD, GSH and the ratio of GSSG in renal homogenate. F Representative TUNEL staining and quantification (3 field per mice; n = 6) of apoptotic cells in kidney sections from mice (Scale bar = 20 μm). G, H Total cells lysates from kidney of mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-TFRC or anti-TXNDC5 antibody, and western blotting using indicated antibodies. For all panels, data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction test. For all panels, data were presented as mean ± SD. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction test.

ML364 alleviating fibrosis and ferroptosis in the kidney, liver, and lungs of male mice

Given the vital role of USP2 in the development of renal fibrosis, we hypothesized that ML364 intervention could improve the fibrotic response of the mouse liver, kidney, and lungs. As expected, ML364 intervention alleviated the extent of kidney fibrosis induced by UUO surgery (Fig. 7A). The upregulation of CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and HMOX1, and the downregulation of GPX4 were also restrained after ML364 treatment in the kidney of UUO mice (Fig. 7B). Consistently, ML364 intervention downregulated the transcription of profibrotic genes, namely Col1a1, Col3a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, and Acta2, in mouse kidneys following injury (Fig. 7C). Further analysis revealed that ML364 administration reduced Ngal and Kim-1 transcripts in the kidneys of UUO mice (Fig. 7D). In the kidneys of UUO mice treated with ML364, there was a decrease in MDA levels and iron accumulation, along with an increase in SOD levels and the GSH/GSSG ratio (Fig. 7E). TUNEL staining demonstrated that treatment with ML364 significantly reduced cell death in the kidneys of UUO mice compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 7F). Furthermore, ML364 decreased the protein levels of USP2, TFRC, and TXNDC5, while increasing the ubiquitination level of TFRC and TXNDC5 in the kidney of UUO mice (Fig. 7G, H).

A–G WT mice were randomly assigned to sham or UUO surgery according to an established protocol, and after 3 days, mice were treated with ML364 (10 mg/kg body weight, i.v. daily) or vehicle. Kidney samples were obtained from mice on day 10 post-UUO or sham surgery (n = 6 per group). A Representative images of Masson’s trichrome staining and Sirius red in kidneys from mice (scale bar = 100 μm). B Western blot analysis of the expression of USP2, CCN2, FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, GPX4, HMOX1, and Tubulin. C, D The mRNA level of Col1a1, Fn1, Eln, Ccn2, Acta2, Col3a1, Ngal, and Kim-1. E The level of Iron, MDA, SOD, GSH and the ratio of GSSG in renal homogenate. F Representative TUNEL staining and quantification (3 field per mice; n = 6) of apoptotic cells in kidney sections from mice (Scale bar = 20 μm). G, H Total cell lysates from the kidney or liver of mice subjected to Co-IP with anti-TFRC or anti-TXNDC5 antibody, and western blotting using the indicated antibodies. For all panels, data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction test.

Similar to previous findings, the administration of ML364 effectively suppressed the fibrosis and ferroptosis in the liver induced by carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) and in the lung induced by bleomycin (BLM) (Fig. S5A–D). In the tissue samples from mice, it was observed that treatment with ML364 notably mitigated the degree of fibrosis, as evidenced by the results of Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red staining (Fig. S5A, H). ML364 treatment led to a reduction in the expression of fibrosis-related genes, as well as a decrease in the accumulation of iron and MDA levels (Fig. S5B–E,J, K). Furthermore, ML364 was found to induce the ubiquitination of the TFRC and TXNDC5 proteins, along with the ratio of GSH/GSSG (Fig. S5F, G, I). In conclusion, our study demonstrates the therapeutic potential of ML364 in mitigating fibrosis and ferroptosis in the kidney, liver and lung tissues.

Discussion

This study shows kidney USP2 lactylation drives CKD pathogenesis. USP2 deubiquitinates TXNDC5 to activate TGFβ signaling and TFRC to promote ferroptosis. TGFβ1-induced K447 lactylation is essential, while SIRT2 delactylates USP2 to suppress its activity. Genetic knockout or ML364 inhibition of USP2 alleviates renal/liver/lung fibrosis in mice, identifying USP2 as a CKD therapeutic target.

Several studies have demonstrated that USP2 is involved in regulating the activity of the TGFβ signaling pathway. USP2 interacts with SMAD7 and prevents SMAD7 ubiquitination in Glioblastoma, while SMAD7 is a major inhibitor of TGFβ signaling44. In contrast, another study showed that the interaction between USP2 with TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 upon TGFβ stimulation was found to promote metastasis by facilitating the recruitment of SMAD2/3, essential components of the TGFβ signaling cascade in lung adenocarcinomas45. In the current study, we found that USP2 is an endogenous activator of TGFβ signaling through deubiquitinates and stabilizes TXNDC5 and TXNDC5 direct binding with and stabilization of TGFBR1 (Fig. 1). Moreover, previous studies have shown that TGFβ can upregulate USP2 expression in trophoblasts46. In contrast, we found TGFβ-induces the lactylation of USP2, but not the expression of USP2, in TECs (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results suggest that the regulatory effect of USP2 on the TGFβ signaling pathway is heterogeneous in different tissue cells. The significance of our work lies in expanding the understanding of the multifunctional nature of USP2 and its implications across an array of pathophysiological circumstances.

In the current study, according to the proteomic sequencing data, we found that SPTBN1 and CDKN1C were also reduced in the kidneys of Usp2 KO mice compared to those in WT mice. The βII-Spectrin (SPTBN1) is an adapter protein for SMAD3/SMAD4 complex formation during transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signal transduction47. TGFβ triggers phosphorylation and association of SPTBN1 with SMAD3 and SMAD4, followed by nuclear translocation47. SPTBN1 deficiency results in the mislocalization of SMAD3 and SMAD4 and loss of the TGFβ-dependent transcriptional response, which can be rescued by overexpression of the COOH-terminal region of SPTBN147. Our research results indicate that when TXNDC5 is absent, USP2 OE does not have a significant regulatory effect on the phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of SMAD3, as well as the expression of TGFβ target genes (Fig. S2G–K). These results indirectly suggest that SPTBN1 may not be a key target for USP2 in regulating the TGFβ signaling pathway, but further research is still needed to explore these aspects.

As for CDKN1C (also known as p57) is a strong inhibitor of several G1 cyclin/Cdk complexes and a negative regulator of cell proliferation. Using primary human hematopoietic cells and microarray analysis, a report showed that p57 was the only cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor induced by TGFβ48. Upregulation of p57 mRNA and protein occurs before TGFβ-induced G1 cell cycle arrest, requires transcription, and is mediated via a highly conserved region of the proximal p57 promoter48. The upregulation of p57 is essential for TGFβ-induced cell cycle arrest in these cells48. However, other studies indicated that accelerated degradation of p57 by TGFβ1/SMAD signaling is mediated through a newly synthesized factor that modifies p57 or the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in osteoblasts49,50. The contradictory effects of TGFβ signaling on the regulation of p57 transcription and protein level suggest that the regulation of TGFβ on p57 may be cell- and tissue-specific. In our results, the protein level of p57 is decreased, which may be due to the inactivation of the TGFβ signaling pathway following Usp2 KO (Fig. 1B). We will further investigate these aspects in the future.

Our study differs fundamentally from the reported research on SETDB151 in both mechanistic focus and molecular targets. While that study explored how the histone methyltransferase SETDB1 inhibits TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in pulmonary fibrosis via epigenetic regulation of SNAI1, our work identifies the deubiquitinase USP2 as a key mediator of TGFβ signaling and ferroptosis across multiple organs. Mechanistically, SETDB1 suppresses EMT by promoting H3K9me3 at the SNAI1 locus, whereas USP2 activates TGFβ signaling through deubiquitination/stabilization of TGFβR1 (via TXNDC5) and enhances ferroptosis by deubiquitinating TFRC. Notably, SETDB1 links ferroptosis to EMT induction as a secondary effect, while USP2 directly drives ferroptosis as a profibrotic mechanism. These distinctions highlight divergent pathways: epigenetic regulation of EMT versus posttranslational control of TGFβ/ferroptosis crosstalk via USP2.

This study identifies deubiquitinase USP2 as an endogenous agonist of TGFβ and ferroptosis, modulating TXNDC5 and TFRC via deubiquitination. TGFβ-induced lactylation of USP2 is critical for activating TGFβ signaling, while SIRT2 delactylates USP2 to suppress its activity. Inhibition of USP2 reduces TGFβ signaling and ferroptosis, proposing a therapeutic strategy for CKD.

Limitation

There are several limitations of our study. First of all, in our study, we used only male mice to examine the response to renal USP2 deficiency. Second, we have demonstrated that TGF-β1 affects USP2 activity but not USP2 expression by stimulating the K447 lactylation site of USP2, which we speculate may be related to the conformational change of USP2. Additionally, whether TGF-β1 stimulation affects USP2 expression or its lactylation has not been verified in human samples, which requires fresh kidney biopsy samples for WB experiments to verify.

Data availability

The data underlying the results presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon submission of a legitimate request. All uncropped and unedited blot/gel images are provided as Supplementary Figs. in the Supplementary Information PDF, with clear labels indicating their correspondence to the respective panels in the main figures. Mouse kidney proteomics measurement raw data (Usp2 KO vs. WT) were deposited at iProX (Subproject ID: IPX0014038001; Integrated Proteome Resources; https://www.iprox.cn/) and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Proteomics sequencing analysis data of kidney tissues from USP2 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Numerical source data for graphs and charts presented in this study are available in Supplementary Data 2.

Code availability

No custom computer code was developed in this study. For visualization of enrichment results (including terms, gene ratio, gene counts, and P values), the ggplot2 and ggpubr packages in R software were used, following the methods described in Ito, K. & Murakami, D. (2013)36. Additionally, high-throughput analysis of myelinating cultures was conducted using the ImageJ macro “MyelinJ”, as detailed in Michael, W.J., George, M.A., Hugh, W.J., and Susan, B.C. (2019)35. The original code/tools for all analyses are publicly available as described in the respective publications.

References

Guangyan, Y. et al. HSPA8 dampens SCAP/INSIG split and SREBP activation by reducing PKR-mediated INSIG phosphorylation. Cell Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2025.115339 (2025).

Neil C., H., Florian, R. & Thomas A., W. Fibrosis: from mechanisms to medicines. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2938-9 (2020).

Shu, Y. et al. KLF10 promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression through transcriptional activation of zDHHC7. EMBO Rep. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202154229 (2022).

Konrad, H. et al. Platelet-instructed SPP1(+) macrophages drive myofibroblast activation in fibrosis in a CXCL4-dependent manner. Cell Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112131 (2023).

Yun-Ji, L. et al. MicroRNA-19b exacerbates systemic sclerosis through promoting Th9 cells. Cell Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114565 (2024).

Li, L. et al. Orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII enhances myofibroblast glycolysis leading to kidney fibrosis. EMBO Rep. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.202051169 (2021).

Meng, X. M., Nikolic-Paterson, D. J. & Lan, H. Y. TGF-β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 12, 325–338 (2016).

Naiquan, L., Dongyang, L., Dajun, L., Ying, L. & Jing, L. FOSL2 participates in renal fibrosis via SGK1-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition of proximal tubular epithelial cells. J. Transl. Int. Med. https://doi.org/10.2478/jtim-2023-0105 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Sp1-like protein KLF13 acts as a negative feedback regulator of TGF-β signaling and fibrosis. Cell Rep. 42, 112367 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. Inhibition of PFKP in renal tubular epithelial cell restrains TGF-β induced glycolysis and renal fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 14, 816 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. SIRT2 alleviated renal fibrosis by deacetylating SMAD2 and SMAD3 in renal tubular epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 14, 646 (2023).

Yang, S. et al. MircroRNA-92b as a negative regulator of the TGF-β signaling by targeting the type I receptor. iScience 26, 108131 (2023).

Vander Ark, A., Cao, J. & Li, X. TGF-β receptors: In and beyond TGF-β signaling. Cell Signal. 52, 112–120 (2018).

Wang, W., Zhu, Y., Sun, Z., Jin, C. & Wang, X. Positive feedback regulation between USP15 and ERK2 inhibits osteoarthritis progression through TGF-β/SMAD2 signaling. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 84 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. USP4 is regulated by AKT phosphorylation and directly deubiquitylates TGF-β type I receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 717–726 (2012).

Zhang, S. et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 11 serves as a marker of poor prognosis and promotes metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest. 98, 883–894 (2018).

Guangyan, Y. et al. USP43-mediated HSPA8 deubiquitination alleviates diabetic kidney disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2025.152177 (2025).

Shu, Y. et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme USP2 alleviates muscle atrophy by stabilizing PPAR-γ. Diabetes https://doi.org/10.2337/db24-0375 (2025).

Luza, S. et al. The ubiquitin proteasome system and schizophrenia. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 528–537 (2020).

Bard, J. A. M. et al. Structure and Function of the 26S Proteasome. Annu Rev. Biochem. 87, 697–724 (2018).