Abstract

Candida auris is a critical priority fungal pathogen (World Health Organization). Clinical management is challenging, with high associated mortality, rapidly increasing antifungal resistance, and frequent nosocomial outbreaks. A critical bottleneck in understanding virulence is the lack of gene expression profiling models during infection. We developed a fish embryo yolk-sac microinjection model using Aphanius dispar (Arabian killifish; AK) at human body temperature. This enabled interrogation of infection dynamics via dual host-pathogen RNA-seq across five major clades of C. auris (I-V). Host responses included heat shock, complement activation, and nutritional immunity, notably haem oxygenase (HMOX) expression during clade IV infection. We identified a pathogen transcriptional signature across all five clades, strongly enriched for putative xenosiderophore transmembrane transporter candidate (XTC) genes. We describe this family and a sub-clade of five putative haem transport-related (HTR) genes. Only the basal clade V isolate formed filaments, associated with canonical and atypical regulators of morphogenesis. Clades I and IV demonstrated increased virulence, accompanied by up-regulation of three HTR genes in clade IV, and the non-mating mating-type locus (MTL) gene PIKA in both clades. Our study provides insights into C. auris pathogenesis, highlighting species-wide in vivo up-regulation of XTC genes during host tissue infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Candida auris is an ascomycetous yeast that has rapidly progressed from a recently identified species to a World Health Organization (WHO) critical priority human fungal pathogen and global public health threat1,2. The earliest known isolate was retrospectively identified from a bloodstream infection dating to 19963, following its initial description as a novel species in 20084. Over the past decade, C. auris has caused nosocomial outbreaks globally, leading to intensive care unit (ICU) closures and substantial infection control challenges and costs5,6,7. Alarmingly, C. auris is now a leading cause of invasive candidiasis in several hospital settings globally8,9. C. auris bloodstream infections carry an associated mortality rate of approximately 45%10 and are often resistant to azole antifungals, with an increasing number of pan-drug resistant isolates reported globally11. Phylogenetic analysis has revealed five major clades of C. auris, and a minor sixth clade recently found12,13, suggesting multiple populations of C. auris have simultaneously emerged from unknown environmental reservoirs that have facilitated its rapid adaptation to human infection, drug resistance, and healthcare-associated persistence14,15. Clade-specific differences have been noted: clades I, III, and IV are more commonly associated with invasive disease, whereas clades II and V have been linked to otomycosis16. Mortality from candidaemia may be higher with clades I and IV than clade III, but this difference has not been shown to be statistically significant17. These differences in clinical presentation and virulence may reflect underlying genotypic variation across clades.

Gene expression profiling has become a standard approach for assessing host and pathogen responses to infection. However, no experiment has described the gene expression of C. auris during in vivo infection of living tissue to date. Studies have assessed the pathogen transcriptome in an in vivo murine catheter model18, human whole blood ex vivo19, co-incubation with human dermal fibroblasts20 or murine cell line-derived macrophages21. Additionally, host responses have been assessed in murine peripheral skin22, human peripheral blood-derived monocytes23, and murine bone marrow-derived macrophages24. C. auris has been shown to reproduce as budding yeasts in mammalian tissues25,26 and possess multiple adhesins associated with an aggregation phenotype27,28. There has been no evidence of toxin synthesis, unlike distantly related C. albicans29,30. C. auris digests of host tissue through secreted aspartyl proteases31 and evades host immune responses through cell surface masking32 and intra-phagocytic survival with cell lysis33. However, these studies have not interrogated in vivo in-host pathogen gene expression, except for the dual RNA-seq study using the ex vivo whole blood model, for which it was possible to compare gene expression profiles between C. auris and other Candida species19.

The absence of in vivo tissue infection profiling for C. auris may be due to the lack of adequate RNA recovery from current models. Most murine models, such as BALB/c25,34,35,36 and C57BL/6 mice24, have rarely demonstrated lethality through C. auris infection23,37,38 without major immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide/cortisone39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50, monoclonal antibody neutrophil depletion26,51, or other immunodeficiency27,52,53. Additionally, mouse models are also expensive and associated with concerns over environmental pathogen shedding54. Alternative host models such as Galleria mellonella34,44,55,56,57,58,59,60,61, Drosophila melanogaster62 and Caenorhabditis elegans60 have been employed, but these may lack key elements of mammalian-relevant immune systems, thus limiting their scope of application. In patients, immune control of C. auris is thought to depend on myeloid cell activity via C-type lectin receptors such as complement receptor 3 and mannose receptor MMR, followed by interleukin (IL-17) pathway activation63,64. The zebrafish (Danio rerio) model has allowed hindbrain32,65 and swim bladder66 microinjection modelling of C. auris infection, but rarely at temperatures above 30 °C, which zebrafish are broadly intolerant of. Fungal transcriptional programmes can vary greatly across temperatures and are critical for mammalian pathogenesis67,68,69. Despite these successes in profiling host responses, none of these models has enabled the profiling of C. auris RNA during infection.

A marine model could also shed light not only on human infection but also on a possible evolutionarily adaptive niche. The environmental origins of C. auris have not been conclusively demonstrated; however, a marine origin has been hypothesised and supported by the successful isolation of C. auris in coastal waters of both the Indian and Pacific oceans70,71. Notably, a close relative of C. auris in the Metschnikowiaceae clade, C. haemulonii, was first isolated in 1961 from the gut of blue-striped grunt (genera name “Haemulon” for their blood-red mouth interior)72. Fish larvae must survive hostile and varied ocean environments, demonstrating very early innate immune responses such as antimicrobial peptide production and the complement cascade73,74. Only in adulthood are teleost fish expected to possess functional IL-17 subtypes (A and F) that lead to T-helper-17 subset differentiation and adaptive immunity in response to fungal infection75. A thermotolerant teleost fish embryo model, such as the Aphanius dispar, also known as the Arabian killifish (AK), which can acclimatise to temperatures up to and including 40 °C76,77,78, offers a balance between considerations such as suitability for experimental manipulation and applicability to human fungal infection at mammalian temperatures79,80. Additionally, fish embryo models align with the principles of replacement, refinement and reduction of animals in laboratory research and offer an opportunity to develop novel animal models with ethical benefits over models such as adult mice81.

In this paper, we present the first study exploring the in-host virulence of C. auris clades I-V in the AK yolk-sac microinjection model at 37 °C. We supplemented our validation of the model with histology, fungal burden recovery, and dual host-pathogen RNA-seq. By comparing in vivo and in vitro expression profiles of C. auris, we detected a cross-clade expression signature that was significantly enriched for siderophore transporter SIT1 paralogues, which mediate uptake of siderophores produced by other microbes (xenosiderophores). We designated this expanded gene family as xenosiderophore transporter candidates (XTC), which included a haem transport-related (HTR) sub-clade. We also identified in vivo filamentation by clade V during infection, which was associated with orthologues of key hypha-associated genes from C. albicans. Together, these findings substantially enhance our knowledge of the processes employed by C. auris during infection.

Results

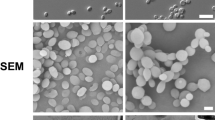

Modelling C. auris infection in A. dispar

AK yolk-sac microinjections with each of the five C. auris clades demonstrated lethality (defined by cessation of heartbeat) at 37 °C (92–100% vs 6% for sham injections; Fig. 1A, B). Earlier lethality was significantly higher for clade I compared to clades II (p = 1.69−04), III (p = 7.8304) or V (p = 1.1503), and for clade IV compared to clades II (p = 7.6603) or (p = III 3.06−02, Fig. 1B, Data S1); median survival was lower for clade I and IV (70.4 and 92.9 h) vs clade II, III and V (106.7, 116.5, and 116.1 h). To investigate morphological outcomes of infection, we compared histological sections of infected yolk-sacs at 48 h post-infection (HPI). All clades exhibited budding yeast morphologies both in vitro and in vivo, except for the clade V strain, which demonstrated predominantly filamentous forms when grown in vivo (Fig. 1C). Growth kinetics showed only minor inter-clade variation. Clade II grew more slowly in YPD-broth at 37 °C (Fig. S1A), although this did not translate into lower CFU recovery from infected embryos (Fig. 1D). On average (\(\bar{x}\)), 673 CFUs were recovered per infected embryo post injection, which increased 166-fold at 24 HPI (\(\bar{x}=1.12\times {10}^{5}\)) and by an additional ~60% at 48 HPI (\(\bar{x}=1.78\times {10}^{5}\)). Filamentous clade V isolates formed rough (vs smooth) colonies on YPD-agar in approximately 1–2% of cases (Fig. S1B), composed of elongated yeast cells, filamentous and pseudohyphal structures measuring >10–50 μm (Fig. S1C). These results confirm that AK yolk-sac microinjection supports active C. auris infection, leading to embryo mortality by 7 days post-injection. This system therefore provides a robust and informative in vivo model for studying the pathogenicity of human fungal pathogens such as C. auris.

A Illustrative time-lapse microscopy of embryo death, including yolk-sac collapse during infection (clade I infection) or survival (sham injection) using Acquifer live imaging. B Survival curves for embryos injected with each C. auris clade or sham injection. Significance testing between groups is given in Data S1; hours post-injection (HPI). C H&E Staining of AK yolk-sac at 48 HPI for each clade or sham injection; morphology is indicated by blue arrows, with insets indicating typical yeast (clade III) and filamentous morphology (clade V). The yolk-sac edge is oriented at the top. D Colony forming units (CFUs) per clade from embryos homogenised after injection as an indicator of injection dose and in vivo growth.

Host responses to C. auris infection

To characterise host responses to C. auris during infection, we identified host differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in AK yolk-sacs between infection by each clade and sham injections (Fig. 2). Across all infections, 685 host DEGs were detected (representing 2.49% of potential genes), including 183 up-regulated and 508 down-regulated genes in response to at least one clade. Notably, there were no DEGs common to infection by all five clades. Only five DEGs (four up-regulated genes and one down-regulated gene) were shared across infections with four clades (Data S2). Up-regulated genes included Laminin subunit alpha-1 (LAMA1, not significant in response to clade III) and three genes that were not significant in response to clade II, Glucose-6-phosphatase (G6PC), DN117939 (hypothetical protein) and Tryptophan aminotransferase protein 1 (TAR1); immunoglobulin-like fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 1 (IGFN1) was down-regulated. These findings suggest host transcriptional responses to C. auris are modest and clade-specific at these early time points, possibly reflecting variation in virulence and stages of infection.

At 3 days post fertilisation (DPF), A. dispar were microinjected with C. auris from each of five clades I–V. Transcriptional comparisons were made between host and pathogen conditions using either a shared or clade-specific reference. Functional annotations were generated to ascertain enriched features. Illustrations © the authors.

Although we did not observe a shared host transcriptional response across all C. auris clades, we identified distinct, clade-specific host responses to infection. At 24 HPI, clade II elicited the largest host response, with 41 up-regulated genes and 210 down-regulated genes (Fig. 3A). Minimal differences were detected between sham injection and uninjected controls, confirming the specificity of the infection-induced response (Fig. 3B, SI Appendix). By 48 HPI, clade IV induced the strongest transcriptional response, with 49 up-regulated and 104 down-regulated host genes. Notably, we detected differential expression of several key immune-related genes across clades, with the most pronounced changes in clades I and IV. These included heat shock proteins (HSP30 and HSP70), complement cascade elements, pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), inflammatory transcription regulators, and genes involved in nutritional immunity (Fig. 3C). Among genes associated with pathogen recognition, CARD14 was most prominently up-regulated during clade I and IV infection at 48 HPI (Fig. 3D, E), while NLRP3 (a key inflammasome component) was expressed during clade III infection at 24 HPI.

A Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each of two comparisons, sham injection vs no injection (left panel), and C. auris injection vs sham injection (right panel), at either 24 or 48 h post-injection (HPI). B Volcano plot showing log-fold change and significance according to -log10 false discovery rate (FDR) for sham injection vs no injection. C Heatmap demonstrating log-fold change for differential expression between C. auris injection and sham injection for groups of genes. D Volcano plot showing log-fold change and significance for DEGs expressed during infection with clade I C. auris at 48 HPI. E Volcano plot showing log-fold change and significance for DEGs expressed during infection with clade IV C. auris at 48 HPI.

Functional enrichment analysis of host DEGs revealed several significantly enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms (and additional annotations), particularly in response to the more virulent clades I and IV at 48 HPI. Clade I infection was associated with 15 enriched GO terms, driven in part by up-regulation of LAMA1 and LAMA2 (orthologues of Laminin subunit-α, Fig. 3D). In clade IV-infected yolk-sacs, enriched terms were related to haem catabolism, haem binding, and haem oxygenase (HMOX) activity. Two HMOX orthologues were major contributors to this response, such as haem oxidation (log-fold change \(\bar{x}=3.96\), FDR < 0.0003, Fig. 3E, Fig. S3). Quantitative PCR confirmed increased expression of HMOX genes in the host; embryos infected by clade IV demonstrated late up-regulation at 48 HPI with a fold change of 3.26 and 9.21 for two HMOX genes, DN109585 and DN112160, respectively (compared to uninfected embryos; Fig. S2A). Another host up-regulated gene from infection by clade IV was ferroxidase hephaestin (HPHL1), which is also involved in iron nutritional immunity. Together, these findings suggest that heat shock proteins, nutritional immunity (particularly iron), and the complement effect system are important elements of the AK larval response to C. auris microinjection at 37 °C.

Pathogen gene expression during A. dispar infection

We compared the in-host transcriptome to expression induced by growth in a standard rich laboratory media (YPD). Principle components and sample correlation clustering from gene expression data indicated a predominant separate clustering of in vivo vs in vitro conditions, indicating that the gene expression profile of C. auris during infection is substantially different to that when it is grown in nutrient-rich laboratory media (Fig. S1G, S1H). We identified 960 DEGs between in vivo AK infection at 24 HPI or 48 HPI vs in vitro culture in YPD over 24 h (499 up-regulated, 523 down-regulated, 17.7% of potential genes, Fig. 4A). We identified few DEGs between the two time-points 24 HPI to 48 HPI, with zero DEGs for clade IV and V between those time points (Fig. 5A). The highest numbers of up-regulated DEGs were identified in the filamentous clade V at 24 HPI and in the more virulent clades I and IV at 48 HPI (Fig. 5B, C). Six functional annotation terms were enriched across all in-host infections at 48 HPI, related to major superfacilitator family carbohydrate and siderophore-iron transmembrane transport (Fig. 6). Quantitative PCR confirmed increased expression of SIT genes that had been significantly up-regulated by C. auris at 48 HPI (Fig. S2B): during embryo infection, clade IV demonstrated up-regulation with a fold change of 2.55 and 8.16 at 24 and 48 HPI, respectively, for XTC3 (B9J08_003921) compared to culture in YPD alone. Furthermore, XTC7 (B9J08_001487) was up-regulated with a fold change of 39.5 and 130.8 at 24 and 48 HPI, respectively. Together, this analysis reveals that during infection, which is a nutrient-limited environment, C. auris is responding by significantly increasing expression of genes involved in sugar uptake, as well as members of the C. auris expanded gene family of siderophore transporters.

A Total DEGs per clade for each comparison between 24 h post injection (HPI), 48 HPI, and growth in YPD alone. B Combined set of significant DEGs common to all five clades between in vivo infection and in vivo growth in YPD. Genes are coloured by manually annotated category (Data S3). C Volcano plots demonstrate mean log-fold change for DEGs identified for any clade. Genes with infinite false discovery rate (FDR) are indicated with an arrow. Genes included in the combined set are coloured by category as per (B).

C. auris gene set, pathway and domain enrichment: Transcripts from C. auris reference genomes for each clade were annotated for Gene Ontology (GO) terms, Kyoto Encycopaedia of Genes and Genome pathways (KEGG), PFAM domains, transmembrane domains, GPI-anchored domains, SignalP domains, and membership within the accessory genome. For each set of up-regulated or down-regulated genes in each comparison, Fisher’s exact test was used with Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) correction for multiple testing for each set, with a false discovery rate (FDR) cut-off of 0.001. Mean log-fold change and ratio of genes in that set were calculated for genes in each set possessing each feature.

Thirteen DEGs common to all clades of in-host transcription were transmembrane transporters, including up-regulation of transporters for xenosiderophores (SIT1 genes 3921 and 1487), sugar transporters (HGT2, HGT12), an ammonia transporter (ATO2), and a nicotinic acid transporter (TNA1). We also found down-regulation of several drug-resistance-related efflux pumps (MDR2 and DTR1) and peptide transporters (TPO3, PTR22, Fig. 4B and Data S3). Surprisingly, several putative virulence factors such as lipase LIP1 and cell wall-related KRE6 and SOD6 were also down-regulated across all five clades, as were ALS4 and MDR1 in at least one clade (Fig. 4C). Several members of the SIT1 family were differentially expressed by <5 of the clades including 0002, 1457, 1458, 1542,2110, 2241, 2465, 3908, and 4097. Meanwhile, two SIT1 genes were down-regulated across 3 of the clades (1519 and 1499). Several SIT1 genes were upregulated in ≥1 clade and down-regulated in ≥1 clade (3908 and 2465). The strong signal of differential expression in the SIT1 expanded gene family highlights the potential importance during in-host survival.

Transcriptional differences underlying virulence and filamentation

The more virulent clades (I and IV) are a-type mating type locus (MTL), while the less virulent clades (II, III and V) contain the α-type MTL. Surprisingly, we found differential expression in several non-mating genes between more virulent and less virulent clades, including poly-A polymerase (PAP1), oxysterol binding protein (OBPA) and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PIKA, Fig. 7B). Within the set of 10 DEGs shared across all comparisons, several genes outside the MTL were up-regulated, including vacuolar protein sorting gene, VPS70, and filamentous growth regulator, FGR14. Additionally, the drug efflux pump, MDR1, was down-regulated across all comparisons, supporting the idea of a fitness trade-off between resistance and virulence.

A The set of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) shared across all comparisons between clade I and IV (more virulent) and clade II and III (less virulent), coloured by manually annotated category, at either 24 or 48 h post infection (HPI). B Volcano plots demonstrate mean log-fold change for each DEG found in any comparison; genes included in the combined set are coloured as per (A). C The set of DEGs shared across all comparisons between filamenting clade V and all other clades (I–IV) in vivo, coloured by manually annotated category. D Volcano plots demonstrating mean log-fold change for all comparisons between clade V and clades I–IV at 24 HPI and 48 HPI for each DEG found in any comparison; genes included in the combined set are coloured as per (C).

To explore drivers of filamentation by the clade V strain, we identified 1046 DEGs between clade V and each of the other clades (I-IV), comprising 601 up-regulated and 526 down-regulated genes across all comparisons. We identified a set of 57 genes shared across all comparisons for in vivo conditions only, since we did not observe filamentation in nutrient-rich YPD. Twenty-two genes were up-regulated at 24 HPI, seven at 48 HPI, and 18 at both time-points (Fig. 7C). Most of the up-regulated genes were metabolic (n = 13), including two cytochrome P450 ERG5 orthologues, though ERG11 was down-regulated. Transmembrane transporters for sugar (including two HGT13 orthologues), amino acids and siderophores (SIT1 1487) were also up-regulated (n = 10). Cell wall genes up-regulated in filamentous clade V (n = 8) included the novel adhesin SCF1, GPI-anchored genes PGA31 and IFF4, and orthologues of classical C. albicans hyphal adhesins ALS3 and RBR3. We identified differentially expressed transcription factors and related regulators, such as HAP41 and the pheromone receptor STE2, which could play a governing role on these responses.

We also examined significant DEGs between clade V and at least one other clade using mean-log fold change (Fig. 7D). Several genes that play critical roles in C. albicans hypha formation were highly up-regulated, such as transcription factor UME6 and hypha-specific G1 cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase HGC1. Enrichment analysis indicated up-regulated gene sets involving CFEM domain, cytochrome P450/oxidoreductase activity, hypha-regulated cell wall GPI-anchored proteins and siderophore transport, particularly at 24 HPI and comparing clade V to clade II (Fig. 7D). Significantly up-regulated iron-related transport genes in clade V included FRE3, CFL4, FRP1, and SIT1 genes 1487, 1499, 1519, 1542, and 4097. This is consistent with the preservation of a major filamentation programme in C. auris, demonstrated in the basal clade V.

Xenosiderophore transporter candidate (XTC) and haem-transport related (HTR) expanded gene family

Given the prominence of SIT1 orthologues across the transcriptomic analyses of C. auris during in vivo gene expression, we set out to characterise the structural and evolutionary conservation of the expanded gene family across orthogroups, including outgroup species C. haemulonii and C. albicans (Note S1). We performed phylogenetic analysis on proteins with sequence similarity across seven orthologue clusters, of which two main groupings of transporters with 14 transmembrane domains (TMRs) emerged (Fig. S5). The first group included genes with functional annotation relating to siderophore import (including 12 genes in clade I). The second group included haem transmembrane import genes (including 5 genes in clade I). Most of the orthologues retained 14 TMRs, and a few had evidence of additional annotations except for the trichothecene mycotoxin efflux pump PFAM domain across multiple groupings. The orthologue SIT1 1547 contained 12 TMRs and was up-regulated with SIT1 1548 containing 2 TMRs, which was not identified as a SIT1 orthologue in our pipeline but has previously been described as such19,82.

To explore the evolutionary history of SIT1-related genes in fungi, we performed Blastp searches for orthologues of C. albicans SIT1 using an e-value cut-off of 1e−20 across 226 fungal species’ reference genomes (n = 304). We identified 1689 hits, which clustered into two branches: a smaller branch (n = 397) annotated for siderophore transport, including the 12 C. auris groupings which we have designated “xenosiderophore transporter candidates” (XTC), and a larger branch (n = 1292) featuring genes predicted (by GO term) to encode haem transporters, including the 5 C. auris groupings, which we have additionally designated “haem transport-related” (HTR, Fig. 8A). There were no putative haem transporters or members of the larger branch for C. albicans, which only contained the single SIT1 gene. We calculated the mean number of orthogroups per genome per species (Fig. 8B). This showed the most prominent expansion of the XTC branch in the Metschnikowiaceae clade, including C. auris (12 orthologues) and even more so in C. haemulonii, with 15 orthologues. No other fungal species or group of species contained so many. XTC orthologues were not present in any members of the basal Blasocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota and Mucoromycota, or in several Ascomycota (e.g. Pichia kudriavzevii, Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Pyricularia oryzae) and Basidiomycota (e.g. Ustilago maydis). Common human fungal pathogens such as Aspergillus fumigatus, C. albicans and Nakaseomyces glabratus contained only one XTC orthologue (Fig. 8B). The HTR clade, by contrast, was more prominent across fungal phyla, with as many as nine in Mucor species, 16 in A. flavus and 22 in F. solani. We therefore propose a naming of these two expanded gene families as XTC1-12 and HTR1-5 in C. auris (Table 1).

A Panfungal xenosiderophore phylogeny based on blastp hits for C. albicans SIT1 across fungal genomes available in FungiDB. Sequences were aligned with Clustal Omega and FastTreee, scale bar: substitutions per site, XTC: xenosiderophore transport candidate, HTR: haem transport-related. B Per-species mean Blastp hits for siderophore transporters. C Differential expression of XTC/HTR genes assigned in order of B8441 v3 contig across experiments in this paper.

We note the absence of XTC5 in clade V, XTC10 in clade IV, and in addition to these, XTC4, XTC9 and XTC11 in clade II (Fig. 8C). Clade II, which exhibits the greatest degree of XTC gene loss, is also considered by some to be the least virulent strain. It is also noteworthy that the AK embryo expressed HMOX genes during clade IV infection, while clade IV C. auris up-regulated HTR1, HTR2 and HTR5. This suggests a specific host-pathogen interaction axis in nutritional immunity related to haem scavenging. No other clades of infection were associated with such iron-related functional enrichment in the host, and no other clades expressed more than one HTR gene. In summary, XTC1, XTC2, XTC3, XTC4, XTC6, XTC7, XTC11 and XTC12 were up-regulated in-host, while XTC8, XTC9 and XTC12 were down-regulated in at least one clade, while up-regulation of XTC3 and XTC7 was significant across all clades. Additionally, the more virulent clades were associated with up-regulation of XTC4, XTC5 and XTC8. The filamentous clade V up-regulated XTC7 across comparisons with all other clades, and up-regulated XTC1, XTC4, XTC8 and XTC9 compared to at least one other clade.

Discussion

We describe the use of an AK yolk-sac microinjection model for comparative functional genomics of C. auris during in vivo in-host infection. All five clades demonstrated lethality, with an increase in virulence during clades I and IV infections, consistent with clinical and laboratory findings17. In-host growth was similar across all clades and high enough to indicate a large enough in vivo fungal burden for robust bulk transcriptome interrogation across the species. The contained nature of the yolk-sac provides a host tissue growth medium that enables the assessment of pathogen survival and virulence strategies in vivo and a straightforward experimental unit of host tissue without the challenges of pathogen RNA isolation, such as locating foci of infection in larger animals. Thus, an AK yolk-sac microinjection model has the potential to fill a substantial need for in vivo gene expression studies in general.

We investigated the host transcriptional response to C. auris infection, which featured an innate immune response, as expected. The most highly up-regulated genes included two predicted haem oxygenase (HMOX) genes. HMOX genes have been shown to mask iron from invading pathogens as a feature of anti-Candida nutritional immunity83, so presumably have a similar function against C. auris. This was particularly notable given HMOX genes were up-regulated in response to clade IV infection, and the clade IV isolate had a corresponding significant up-regulation of three haem transport-related HTR genes. In addition to nutritional immunity genes, we found up-regulated heat shock and complement cascade genes during infection, confirming the expected immune response to fungal infection63,64. Genes with complex roles in immunity were up-regulated, such as NLRP3, for which C. auris may be less activating than e.g. C. albicans33,84. It is notable that the yolk-sac model was not associated with histological or transcriptional evidence of host neutrophil recruitment and activation, which may relate to the hypothesis that C. auris is immunoevasive22. Reference genome bias resulting from the available adult gill transcriptome assembly85 may limit detection of host gene expression features, so future long and short read assembly from gene expression data across a range of larval stages could further understanding of AK immunity. Additional time-points could be an informative future area of study to develop fine-resolution strain-specific transcription networks. Furthermore, the potential of a translucent and genetically tractable fish embryo model could enable future visualisation of cellular dynamics and genetic pathway manipulation77.

We provided a thorough investigation of differential expression by C. auris during infection of host tissue compared with in vitro conditions. The lack of a major distinction across time-points (24 vs 48 HPI) indicates that the transcriptional activity of C. auris in-host was highly similar at these stages. Six functional annotation terms (GO, KEGG pathway and PFAM domain) were significantly enriched among genes that were up-regulated across all five clades, including sugar and siderophore transporters. The enrichment of sugar transporters outside of nutrient-rich YPD-broth is unsurprising, such as high-affinity glucose transporter HGT12, with evidence of redundancy in C. albicans86,87,88,89, and HGT2, part of an eight-gene ‘core filamentation response network’ in C. albicans90. More surprising was the down-regulation of putative virulence factors such as Secreted Aspartyl Protease 3 (SAP3), thought to be the most important SAP in C. auris, and required for virulence in a mouse model31. Copper Superoxide Dismutase SOD6 was also down-regulated, previously shown to be down-regulated in iron starvation91. Multi-drug efflux pumps such as MDR2 (down-regulated in vivo) and MDR1 (down-regulated in vivo and in clades I and IV vs clades II and III) are understood to drive drug resistance through multiple but unclear mechanisms in C. auris92,93; in-host down-regulation may indicate a fitness trade-off for virulence vs drug resistance. A total of 12 siderophore transporters were up-regulated during infection, and four were down-regulated, with three family members up-regulated in more virulent clades and five in the filamentous clade V. The prominent finding of these xenosiderophore transport candidate (XTC) genes necessitates further experimental work to address their potential for anti-virulence therapeutic targeting.

We also identified up-regulation of several genes at the mating type locus (MTL) in more virulent strains; MTL genes may contribute to virulence in fungal species, including Cryptococcus neoformans94, through uncertain mechanisms, such as via the expression of non-mating genes contained within the locus. C. auris does not clearly undergo meiotic recombination95 and it is not clear what role MTL-associated genes play in pathogenesis and morphology. Two of the three non-mating genes (PAP1 and PIKA) in the MTL were up-regulated by more virulent strains (I and IV) compared to the less virulent strains (II and III). Importantly, the two more virulent clades (I and IV) contain MTLa rather than MTLα (clades II & III)29, and clades V and VI contain MTLa and MTLα, respectively13. Thus, it is unclear if the up-regulation of non-mating genes is a MTL specific transcriptional nuance or a feature of more highly virulent C. auris clades. The MTL also did not feature prominently in the filamentation response observed in clade V, providing no evidence for an obvious role for the MTL in such morphological changes.

We also observed in vivo filamentation by a representative strain of C. auris clade V, the basal/ancestral clade96, accompanied by a genera-typical filamentous gene expression signature. Specifically, we measured the up-regulation of HGC1 and UME6, which are two of the most important regulators of filamentation in C. albicans, and have recently been described as drivers of C. auris filamentation and biofilm formation97. The expression of adhesin SCF1 in filamenting clade V is noteworthy because its cationic adhesion mechanism has been postulated to be consistent with adhesion mechanisms common to marine organisms, including bivalves27. The generalist marine-isolated pathogen C. haemulonii has also displayed filamentation competence at lower temperatures98, consistent with an ancestral aquatic state. Filamentation is an important pathogenicity trait in fungi, especially Candida species, although its roles have been more poorly described in aquatic infections99.

Human histopathology reports of C. auris infection are rarely published and have not demonstrated classical in-host filamentation, to our knowledge. An ex vivo human epithelial model using a clade I isolate did demonstrate filamentous C. auris at 37 °C after injection into deeper dermis100. Clade III C. auris has also been observed to form filamentous/hyphal forms in G. mellonella injection58. Fan and colleagues have observed filamentous forms of C. auris across all four clades, even demonstrating a higher virulence in the G. mellonella model101, though the phenotype required passage through a murine host with additional prolonged growth at 25 °C for at least 5 d before and after injection25. Other stimuli have induced filamentation in clade I isolates, such as hydroxyurea genotoxic stress102 and Hsp90 inhibition103, where several up-regulated genes in C. auris filamentation (SCF1, IFF4 and PGA31) matched those in our study. Constitutive filamentous growth has also been demonstrated with a transposon-mediated disruption of a long non-coding RNA104, which sit adjacent to chitin deacetylase CDA2, which was down-regulated at 24 HPI in our experiment during filamentation. These findings indicate that hyphal formation is possible across C. auris clades.

We underscored how the family of predicted xenosiderophore transporter genes is significantly expanded in several members of the Metschnikowiaceae clade compared to other Saccharomycetae29, raising questions as to the roles of siderophore transporters in C. auris biology and evolution105. Siderophore synthesis may be unlikely in C. auris, given the lack of evidence in other Candida species106. As a result, C. albicans Sit1, which is required for virulence107, is thought to be a xenosiderophore transporter for iron-chelators produced by other microbes and specific to the ferrioxamine type common in iron-poor ocean environments108,109. Siderophore transporters can also act intracellularly for compartments such as the mitochondrion110,111, or act as efflux pumps for various molecules112, including trichothecene mycotoxins as identified by our functional annotations. Given that XTC gene up-regulation by C. auris has also been detected during ex vivo whole blood infection (XTC2A-B, B9J08_1547-8), this suggests that our findings may be clinically relevant19.

C. auris encodes a large expanded gene family of 17 siderophore transporters that we named xenosiderophore transporter candidates (XTC) 1-12 and haem transport-related (HTR) genes 1-5, the latter sharing sequence similarity with the genomic sequence for S. pombe low-affinity haem transporter Str3113. In other Candida species, such as C. albicans, iron assimilation is understood to be central for in-host survival114,115, where deprivation triggers various pathogenic programmes such as alterations in cell surface beta-glucan116. Haem is acquired by C. albicans through vesicular endocytosis and CFEM-domain containing proteins117,118 and does not contain HTR genes, suggesting a possible loss of transmembrane haem transporters. The ubiquity of HTR across the fungal kingdom and lack of XTC genes in the three basal fungal phyla suggest that SIT1/HTC could have arisen from a duplication of an HTR-related gene in the Dikarya (the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) with subsequent independent loss of both XTC and HTC genes in multiple fungal lineages. These findings together underline the importance of iron metabolism as a clinical target with existing therapies, such as iron chelators deferiprone/deferoxamine with evidence of echinocandin antifungal synergy119 or low toxicity antihelminthic pyrvinium pamoate as a disruptor of iron homoeostasis120,121.

Limitations to this study include the lack of gene knockout studies related to the expanded gene family of XTC/HTR transporters. Depicting the potentially overlapping roles in expanded gene families is a challenge requiring extensive bodies of research122. Another expanded gene family in C. auris is the Hil (Hyr/Iff-like) family, including eight members with similar motifs (effector domain, signal peptide and GPI-anchor) but differing tandem repeat section lengths, which may result in functional variation123. Given the unique expansion of XTC genes in the Metschinikowiaceae clade, assessment of the role in related pathogenic Candida, such as C. haemulonii, may shed light on species-specific adaptation via gene family expansion. Further gene knockouts could confirm roles of DEGs with potential roles in filamentation and virulence, supplemented by additional testing in potentially more clinically relevant models, such as ex vivo whole blood or in vivo murine virulence studies. Finally, investigating a potential antifungal role for manipulation of iron metabolism will require fundamental ascertainment of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of iron chelators in the yolk sac and their effects on fungal growth and gene expression. Development of the AK model is also required to image host immune cells with fluorescent fungal strains, improve reference genome databases, and determine the effects of traditional antifungal drugs on C. auris gene expression during infection.

We present an in vivo host tissue infection transcriptional profile for C. auris, a World Health Organization critical priority fungal pathogen. By examining representative strains from all five major clades implicated in its recent, near-simultaneous global emergence, we uncover clade-specific differences in morphology, virulence and gene expression. Our findings demonstrate the utility of a thermotolerant yolk-sac injection model and support the hypothesis of a marine origin for C. auris. Notably, we observed natural filamentation in clade V and elevated virulence in clades I and IV, each linked to distinct transcriptional programmes. We identify the expanded XTC and HTR families as species-wide, infection-induced features, underscoring their potential as targets for studying fungal biology, pathogenesis, and antifungal development. Together, our results shed light on the mechanisms by which C. auris adapts to and persists in host tissue, offering insights into its evolution from a likely marine yeast ancestor and advancing our understanding of this emerging fungal pathogen and global public health threat.

Methods

Aphanius dispar care, monitoring, husbandry and procedures

Wild-type adult AK aged 18–36 months were kept at the Aquatic Resources Facility, Exeter, in two 28 °C incubation tanks (n = 18, 20), with male and female fish in a 1:2 ratio, 12-h day and night light cycles, and artificial enrichment foliage. Embryos were collected using three plastic netted collection chambers per tank with transfer of all enrichment into tanks, and placed overnight from 16:00 to 09:15 in dark conditions. Chambers were then drained, cleaned and strained with 35 parts per thousand artificial seawater (ASW) to isolate all embryos. Subsequent ASW was sterile suction filtered via 0.2 μm pore Nalgene Rapid-Flow (Thermo Scientific, UK). Embryos were inspected for viability in terms of an intact blastocyst without discolouration by stereo dissection microscope (Optech, UK) and incubated at 30 °C (Memmert, Germany) for 72 h with day and night cycles with daily ASW changes and removal of dead, unhealthy or underdeveloped embryos, with a maximum of 30 embryos per standard size 100 × 15 mm petri dish (Greiner Bio-One, Austria). Excluded embryos were killed or disposed of either by submission in Virkon solution (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) or freezing at −80 °C.

Experimental procedures

Injection needles were prepared using borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard apparatus, USA) and a heated pulling system (heater level >62, PC-10, Narishige, UK). We used tweezers to snap the tip to an estimated 1 mm graticule-measured aperture of 10–20 μm, and sterilised needles before use with 253.7 nm UV light over 15 min (Environmental Validation Solutions, UK). Injection bays were made with microwaved 1% agarose in 1 g (Sigma, USA) per 100 mL ASW for up to 24 embryos in 100 mm petri dishes using custom-made moulds in an inverted 60 mm petri dish. Embryos were randomly chosen from each dish, and the sequence of injection for each biological repeat was randomly allocated by computer. For microinjection, C. auris yeasts were counted by haemocytometer and added to 25 μL sterile filtered phenol red solution 0.5% (Sigma, UK) to a concentration of 0.5 × 108 per mL in 100 μL. Injection needles were loaded with 5 μL injection solution using 20 μL Microloader EpT.I.P.S. (Eppendorf, UK) immediately before injection of up to 30 embryos, before reloading. Injections were performed with 400–500 hPa injection pressure and 7–40 hPa compensation pressure over 100–200 ms with the FemtoJet 4i (Eppendorf UK) using a micromanipulator (World Precision Instruments, UK) and a Microtec HM-3 stereo dissection microscope (Optech, UK). In order to deliver a dose of approximately 500 yeasts in 10 nL solution, an injection bolus was administered to an estimated diameter of 0.2–0.3 mm (10–15% of total embryo diameter) via a single chorion puncture. Any embryos that failed to meet these criteria for injection were excluded. Control in vitro inoculations were microinjected as above into 1 mL YPD in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes before incubation without shaking at 37 °C for 24 h, contemporaneously with embryos as below.

Statistics and reproducibility

For the calculation of sample size per group, we determined that ≥23 embryos per condition were required, based on a power calculation of \(\sigma\) = 0.25, significance = 0.05, power = 0.9, and \(\delta\) effect size of 25% mortality (two-sided t-test). To demonstrate differences in virulence over biological triplicate experiments, Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted with Log-Rank testing and Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) correction125 using survival v.3.5.8 and survminer v.0.4.9 packages in R v.4.4.0. RNA-seq experiments were based on DNA extracted from three separate embryos per condition as technical replicates. RNA was extracted separately for each embryo, except for two embryos (negative control embryos without injection at 24 HPI), which were pooled together and analysed as a single datapoint alongside a third embryo analysed as a duplicate. qPCR readings were from triplicate replicates per condition. Growth curves were taken from four colonies per strain in technical triplicate resulting in twelve data points per colony.

Study design and sample sizes

We used an unblinded prospective virulence study comparing six groups of AK embryo yolk-sac microinjection, including clades I-V of C. auris, and sham injections as the negative control. After excluding embryos that were unhealthy or did not complete successful microinjection, we included n = 10–13 embryos per group per experiment (total n = 34–37 embryos per group). Each embryo was considered to be an experimental unit (n = 70–72 embryos per experiment, total n = 213 embryos). For estimation of C. auris in-host growth by homogenisation and plating of colony-forming units, three embryos per condition per time-point across two (0 and 24 HPI) or three (48 HPI) experiments were used (total n = 126). For time lapse microscopy demonstration of A. dispar yolk-sac collapse and death, representative image sets were chosen from a pilot experiment using a reduced dosage (1/10) of C. auris (n = 4). For histological demonstration of C. auris morphology, one embryo per condition at 24 HPI and 48 HPI each were used in one experiment, and seven embryos per condition plus three embryos without injection in a second experiment (n = 57). RNA was extracted from three embryos per condition per time-point (0, 24 and 48 HPI, n = 54) plus three embryos per time-point without any injection (n = 9, total n = 63) as a control for the impact of microinjection.

C. auris strains and growth

We selected five C. auris strains to represent each major clade (Data S1.). Culture stocks were kept in −80 °C in Yeast extract Peptone Dextrose (YPD) broth (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) containing 25% glycerol (ThermoFisher, UK) and plated onto YPD-agar (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h before inoculation and overnight growth in 10 mL YPD broth at 30 °C in a shaking incubator at 200 RPM (Multitron, Infors HT, UK). Five mL from each overnight culture was then centrifuged at 5000 g for 2 min before triple washing in 1 mL autoclaved deionised water (DIW, Milli-Q, Merck, USA) to prevent aggregation28, then re-suspended again in 200 μL DIW. Decontamination of surfaces was conducted with both mopping and cleaning wipes in 70% Ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) or 10% Chemgene HLD4L (Medimark Scientific, UK) as per manufacturer’s instructions. For growth curves, C. auris strains were grown overnight in YPD in 4 replicates. Overnight cultures were inoculated into YPD to a final OD600 of 0.02 in a 96-well plate. OD600 was read over 25 hourly cycles at 37 °C with 300 s shaking at 2.5 mm amplitude on an Infinite 200 PRO plate reader (Tecan, Switzerland).

Outcome measurement

Individual embryos were kept in 1 mL sterile filtered ASW per embryo in a 48 well flat bottom plate (Corning, USA) sealed with Parafilm ‘M’ (Bemis Company, USA) at 37 °C with passive humidification using a 500 mL open glass beaker of water. Embryos were monitored for presence of heart rate at 24-hourly intervals up to 7 d by stereo dissection microscope. Initial time of injection was subtracted from each time-point to minimise bias between groups. Colony forming units (CFUs) were calculated by homogenisation of embryos at 0, 24 and 48 HPI by autoclaved plastic micropestle in a 1.5 mL conical tube (Eppendorf, UK) in 100 μL 10,000 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) solution (Gibco, UK). Dilutions were made with P/S solution and DIW in 1/10–10,000 and counts were adjusted according to dilution after plating onto YPD agar plates and read after 72 h incubation at 30 °C. Statistical testing between CFU numbers was performed with Wilcoxon testing and BH correction.

Imaging

For direct microscopy, AK were kept in 300 μL ASW containing 0.04% Tricaine anaesthesia (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) in an optical adhesive and parafilm-sealed 96-well plate. These were then monitored for heartbeat by 5 bright field 2X or 4X images at pre-focused z slices taken every 2 h by Acquifer microscopy (Bruker, Germany) over 72 h. All images were processed in ImageJ 1.53a (NIH, USA). Microscopy of YPD-agar-grown colonies was performed without staining in DIW.

Histology

Sectioning and staining were performed by Microtechnical Services, Exeter, UK. Embryos were fixed in 1 mL 10% neutral-buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) for >24 h, followed by immersion in 4% phenol 10 mL glycerine BP made up to 100 mL with distilled water126, sectioned at 4 μm without orientation, and stained with Harris Haematoxylin & 1% Alcoholic Eosin on Leica Autostainer. H&E stained histological sections were imaged on an Olympus IX83 microscope coupled with an Olympus DP23 colour camera using an Olympus UPlanXApo x40/0.95 objective controlled by cellSens software v.3.2. Brightfield microscopy was performed with an EVOS M5000 microscope (ThermoFisher, UK).

RNA extraction and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using the Monarch® Total RNA Miniprep Kit (NEB, USA). Embryos were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, re-suspended in DNA/RNA Protection Reagent and disrupted with an autoclaved plastic micropestle. Bead beating was performed in a FastPrep 24 homogeniser (MP Biomedicals) with 0.5 mm zirconia/silica beads for 8 cycles of 35 s at 6 m/s plus 45 s on ice. Lysate was recovered and incubated for 5 min at 55 °C with proteinase K before addition of lysis buffer and RNA purification following manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA samples were quantified using the Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA), and integrity was checked with the Tapestation 4200 (Agilent, USA). Library preparation and sequencing were performed by the Exeter Sequencing Service. Samples were normalised and prepared using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep - Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module following the standard protocol. Libraries were sequenced on a Novaseq 6000 sequencer with 150 bp paired-end reads. Reads were trimmed with fastp127 v.0.23.1 to remove reads <75 bases and trim based from the 3′ end with q-score <22. Quality control was performed with FastQC (https://github.com/s-andrews/FastQC) v.0.11.9 and MultiQC128 v.1.6.

Differential gene expression

We aligned sequences (\(\bar{x}=52.9{{{\rm{m}}}}\) reads per replicate, range 41.1–112.2 m) using the Trinity pipeline129 v.2.15.1 to the C. auris clade I B8441 reference genome (GCA_002759435.2)29 downloaded from GenBank (mean aligned reads in infected embryos 3.83 m, 0.81–13.1%). We further aligned clade-specific reference genomes for each strain (Data S1.), including clade II (GCA_003013715.2)4, III (GCA_002775015.1)14, IV (GCA_008275145.1)14 and V (GCA_016809505.1)96,130,131. We aligned conditions containing A. dispar to the de novo GJEY01 adult gill transcriptome assembly85 downloaded from GenBank, for which we detected expression over 27,481 potential genes. Alignment was performed with Bowtie2132 v.2.5.1, transcript estimation with RNA Seq by Expectation Maximisation (RSEM)133 v.1.3.3, differential expression with EdgeR134 v.3.40.0, Samtools135 v.1.17 and limma136 v.3.54.0 using a false discovery rate (FDR) p-value cut-off of 0.001 and a log fold change cut-off of +/−2.0. Principal components were calculated and plotted using the prcomp function in Rv4.4.0 and the ggfortify v.0.4.17 R package for fragments per kilobase per million, and correlations plots from counts per million as per the default output of the Trinity pipeline. Log fold change was plotted with ComplexHeatmap137. In creating volcano plots, we did not display a hypothetical host protein without annotations (HP_DN122662) with a log-fold change of −11.11 and a false discovery rate of 30.57 when comparing sham injection vs no injection. Additionally, we did not display four C. auris transcripts with infinite calculated FDR comparing in-host to in vitro DEG at 24 HPI, including TNA1_4893 and NGT1_2864 (up-regulated in-host) and IFF4_4451 and ALS4_4112 (down-regulated in vitro).

Annotation and enrichment

GO terms138,139 were assigned using DIAMOND140 v.2.1.8 via the DIAMOND2GO pipeline141 for each of the C. auris reference genomes. KEGG terms142 were assigned using the BlastKOALA online platform using the eukaryote database143. Protein FAMily (PFAM) domains144 were identified using the PFAM-A.hmm database (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/current_release/Pfam-A.full.gz) and HMMER and HMM Scan145 with a cut-off of 1e−5. Further domain-specific identification was performed with SignalP 5.0146, DeepTMHMM 1.0147 and NetGPI 1.1148. Enrichment analysis for DEG subsets was calculated using the Fisher’s Exact test, adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method per set of up-regulated or down-regulated features in each comparison as a conservative estimate of significant gene set enrichment, with a false discovery rate cutoff of p = 0.001. Annotation tables were checked with additional information from available literature, supplemented by details and web-scraped orthologue names from Candida Genome Database82 and Blastp searches149. Annotations for the GJEY01 genome were also performed using Diamond2GO, BlastKoala and HMMScan as above and checked against A. dispar annotations and gene names obtained directly from the GJEY01 transcriptome makers85. For plotting, lists of GO terms were identified (and for A. dispar enrichment, reduced by removal of redundant terms) by REVIGO150.

qRT-PCR

Quantitative PCRs were performed on three replicates of cDNA reverse transcribed from RNA. Equal quantities of RNA from each sample were reverse transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase and oligo dT primers (Promega, UK). qPCRs were carried out using PowerTrack SYBR Master mix (Applied Biosystems, UK) with cDNA as template on a QuantStudio™ 7 Pro qPCR platform (Applied Biosystems, UK). Fold change in gene expression level was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method with normalisation to the housekeeping genes B2MG (beta-2-microglobulin-like, DN135862|c3_g2_i2) in A. dispar and ACT1 (B9J08_000486) in C. auris. Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism v.10.2.1 (calculation of standard deviation). Oligo sequences are as follows (forward, reverse): DN135862 | c3_g2_i1 (ATGTCTCTGTGAGGTCACTC, GGGAATTCCTGGACTTTACG); DN109585 | c0_g1_i1 (CCACTAAGAGAAACCACGTC, GGAATTCCTGTCTAGCTCCT); DN112160 | c6_g3_i3 (CGGACTGGAGAGAGAAGATT, ACCTAAGTACCGGGTGTAAG); B9J08_000486 (CGTTGTTCCAATTTACGCTG, TCTCAGCAGTGGTAGAGAAG), B9J08_003921 (GTCTAATCTCCAGACGGTCA, CAGAAGCACAAGGGAGTAAC); B9J08_001487 (AATGGTATGTTGAGTTGCCC, ACGTCAAAGGAACCAAGATG).

Orthologue assignment

To identify accessory genes across C. auris clades, we used the Synima pipeline151 with Orthofinder v2.5.5152 with additional reference genomes for C. albicans (SC5314_GCA_000182965.3) and C. haemulonii (B11899_ASM1933202v1). We also incorporated a very recent version of the C. auris B8441 assembly (v3) to arrange contigs and illustrate re-arrangements, with broad syntenic concordance; it contains 5 more genes than v2, for which 27 (0.5%) and 16 (0.3%) genes were unique to each genome, respectively. Multiple alignment of single copy orthologues as defined by Orthofinder was performed with Muscle v5.1153 and a phylogeny was made with FastTree v2.1.11154 using default settings.

RNA-seq meta-analysis

NCBI SRA was searched for ‘Candida auris’ on 16th April 2024 and downloaded as metadata via the ‘Send to: Run Selector’ function. Each project accession number for runs containing RNA was searched against available published literature to identify publications, noting subject of study, clades/strains, growth media, comparative conditions, temperature and time scales used. Calculation of FPKM was performed and analysed as above using the set of single copy orthologues to demonstrate variance via PCA with ggfortify and prcomp packages in R and to calculate an unweighted co-expression Pearson’s correlation (cut-off of 0.85) for SIT1 genes with and without the additional data from the RNA-Seq meta-analysis.

SIT1 analysis

The protein transcript for C. albicans SIT1 was Blastp searched against the draft pangenome database as above. We visualised the structure using Alphafold v3155 and ChimeraX v1.8156. Clade I-V C. auris and C. haemulonii SIT1 genes were aligned using Muscle as above before using RAXML-NG v1.2.2 with 1000 bootstraps and the LG4X model157, which was visualised using ggtree v3.12.0. For panfungal SIT1 analysis, we used the fungidb portal for Blastp using the C. albicans SIT1 against all available fungal data (with no hits within oomyceta), including 274 reference genomes representing 197 species and a cut-off of 1e−20. Annotations for each protein transcript were performed as above to obtain GO terms, KEGG pathways, PFAM domains, GPI-anchors, SignalP domains, and TMRs, while a phylogeny for SIT1 similar sequences across all fungal references was constructed as above, following multiple alignment with Clustal Omega v1.2.4158.

Ethical statement

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. All animal experiments were performed under Project Licence PP4402521 in compliance with University of Exeter Animal Welfare Ethical Review Board regulations and MRC Centre for Medical Mycology Project Review Board, and are reported in line with ‘Animal Research: Reporting in vivo Experiments’ (ARRIVE 2.0) Guidelines124.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw reads have been deposited via NCBI/GEO via accession GSE277854. All generated datasets and required to make figures are available via Github (https://github.com/hughgifford/Arabian_Killifish_C_auris_2024) and Zenodo159.

Code availability

All code required to make figures are available with no restrictions to access via Github (https://github.com/hughgifford/Arabian_Killifish_C_auris_2024) and Zenodo159.

References

Meis, J. F. & Chowdhary, A. Candida auris: a global fungal public health threat. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 1298–1299 (2018).

WHO. World Health Organization (WHO) fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240060241 (2022).

Lee, W. G. et al. First three reported cases of nosocomial fungemia caused by Candida auris. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 4 (2011).

Satoh, K. et al. Candida auris sp. Nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol. Immunol. 53, 41–44 (2009).

Eyre, D. W. et al. A Candida auris outbreak and its control in an intensive care setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1322–1331 (2018).

Taori, S. K. et al. Candida auris outbreak: mortality, interventions and cost of sustaining control. J. Infect. 79, 601–611 (2019).

Shuping, L. et al. High prevalence of Candida auris colonization during protracted neonatal unit outbreak, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2909.230393 (2023).

Adam, R. D. et al. Analysis of Candida auris fungemia at a single facility in Kenya. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 85, 182–187 (2019).

Prayag, P. S., Patwardhan, S., Panchakshari, S., Rajhans, P. A. & Prayag, A. The dominance of Candida auris: a single-center experience of 79 episodes of candidemia from western India. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 26, 560–563 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Is the superbug fungus really so scary? A systematic review and meta-analysis of global epidemiology and mortality of Candida auris. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 827 (2020).

Lyman, M. Notes from the field: transmission of pan-resistant and echinocandin-resistant Candida auris in health care facilities—Texas and the District of Columbia, January-April 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 70, 1022–1023 (2021).

Khan, T. et al. Emergence of the novel sixth Candida auris clade VI in Bangladesh. Microbiol. Spectr. 12, e03540–23 (2024).

Suphavilai, C. et al. Detection and characterisation of a sixth Candida auris clade in Singapore: a genomic and phenotypic study. Lancet Microbe 5, 100878 (2024).

Lockhart, S. R. et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 64, 134–140 (2017).

Gifford, H., Rhodes, J. & Farrer, R. A. The diverse genomes of Candida auris. Lancet Microbe 5, 100903 (2024).

Byun, S. A. et al. Virulence traits and azole resistance in Korean Candida auris Isolates. J. Fungi 9, 979 (2023).

Santana, D. J., Zhao, G. & O’Meara, T. R. The many faces of Candida auris: phenotypic and strain variation in an emerging pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012011 (2024).

Wang, T. W. et al. Functional redundancy in Candida auris cell surface adhesins crucial for cell-cell interaction and aggregation. Nat. Commun. 15, 9212 (2024).

Allert, S. et al. From environmental adaptation to host survival: attributes that mediate pathogenicity of Candida auris. Virulence 13, 191–214 (2022).

Fayed, B. et al. Transcriptome analysis of human dermal cells infected with Candida auris identified unique pathogenesis/defensive mechanisms particularly ferroptosis. Mycopathologia 189, 65 (2024).

Yang, B. et al. A correlative study of the genomic underpinning of virulence traits and drug tolerance of Candida auris. Infect. Immun. 0, e00103–e00124 (2024).

Balakumar, A. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics unveils skin cell specific antifungal immune responses and IL-1Ra- IL-1R immune evasion strategies of emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012699 (2024).

Bruno, M. et al. Transcriptional and functional insights into the host immune response against the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1516–1531 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Innate immune responses against the fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat. Commun. 13, 3553 (2022).

Yue, H. et al. Filamentation in Candida auris, an emerging fungal pathogen of humans: passage through the mammalian body induces a heritable phenotypic switch. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 1–13 (2018).

Chadwick, C., Jesus, M. D., Ginty, F. & Martinez, J. S. Pathobiology of Candida auris infection analyzed by multiplexed imaging and single cell analysis. PLoS ONE 19, e0293011 (2024).

Santana, D. J. et al. A Candida auris-specific adhesin, Scf1, governs surface association, colonization, and virulence. Science 381, 1461–1467 (2023).

Pelletier, C., Shaw, S., Alsayegh, S., Brown, A. J. P. & Lorenz, A. Candida auris undergoes adhesin-dependent and -independent cellular aggregation. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012076 (2024).

Muñoz, J. F. et al. Genomic insights into multidrug-resistance, mating and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat. Commun. 9, 5346 (2018).

Richardson, J. P. et al. Candidalysins are a new family of cytolytic fungal peptide toxins. mBio 13, e03510–e03521 (2022).

Kim, J.-S., Lee, K.-T. & Bahn, Y.-S. Secreted aspartyl protease 3 regulated by the Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway promotes the virulence of Candida auris. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1257897 (2023).

Horton, M. V. et al. Candida auris cell wall mannosylation contributes to neutrophil evasion through pathways divergent from Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. mSphere 6, e00406–e00421 (2021).

Weerasinghe, H. et al. Candida auris uses metabolic strategies to escape and kill macrophages while avoiding robust activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome response. Cell Rep. 42, 112522 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. The first isolate of Candida auris in China: clinical and biological aspects. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 7, 1–9 (2018).

Fan, S., Li, C., Bing, J., Huang, G. & Du, H. Discovery of the diploid form of the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 2641–2646 (2020).

Fan, S. et al. A biological and genomic comparison of a drug-resistant and a drug-susceptible strain of Candida auris isolated from Beijing, China. Virulence 12, 1388–1399 (2021).

Wurster, S., Albert, N. D. & Kontoyiannis, D. P. Candida auris bloodstream infection induces upregulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint pathway in an immunocompetent mouse model. mSphere 7, e00817–e00821 (2022).

Bing, J. et al. Rapid evolution of an adaptive multicellular morphology of Candida auris during systemic infection. Nat. Commun. 15, 2381 (2024).

Ben-Ami, R. et al. Multidrug-resistant Candida haemulonii and C. auris, Tel Aviv, Israel. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 195–203 (2017).

Hager, C. L., Larkin, E. L., Long, L. A. & Ghannoum, M. A. Evaluation of the efficacy of rezafungin, a novel echinocandin, in the treatment of disseminated Candida auris infection using an immunocompromised mouse model. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 73, 2085–2088 (2018).

Zhao, M. et al. In vivo pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of APX001 against Candida spp. In a neutropenic disseminated candidiasis mouse model. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 62, e02542–17 (2018).

Singh, S. et al. The NDV-3A vaccine protects mice from multidrug resistant Candida auris infection. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007460 (2019).

Zhang, F. et al. A marine microbiome antifungal targets urgent-threat drug-resistant fungi. Science 370, 974–978 (2020).

Muñoz, J. E. et al. Pathogenicity levels of Colombian strains of Candida auris and Brazilian strains of Candida haemulonii species complex in both murine and Galleria mellonella experimental models. J. Fungi 6, 104 (2020).

Abe, M. et al. Potency of gastrointestinal colonization and virulence of Candida auris in a murine endogenous candidiasis. PLoS ONE 15, e0243223 (2020).

Forgács, L. et al. Comparison of in vivo pathogenicity of four Candida auris clades in a neutropenic bloodstream infection murine model. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 1160–1169 (2020).

Nagy, F. et al. In vitro and in vivo interaction of caspofungin with isavuconazole against Candida auris planktonic cells and biofilms. Med. Mycol. 59, 1015–1023 (2021).

Forgács, L. et al. In vivo efficacy of amphotericin B against four Candida auris clades. J. Fungi 8, 499 (2022).

Singh, S. et al. Protective efficacy of anti-Hyr1p monoclonal antibody against systemic candidiasis due to multi-drug-resistant Candida auris. J. Fungi 9, 103 (2023).

Salama, E. A. et al. Lansoprazole interferes with fungal respiration and acts synergistically with amphotericin B against multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2322649 (2024).

Torres, S. R. et al. Impact of Candida auris infection in a neutropenic murine model. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 64, e01625–19 (2020).

Xin, H., Mohiuddin, F., Tran, J., Adams, A. & Eberle, K. Experimental mouse models of disseminated Candida auris infection. mSphere 4, e00339–19 (2019).

Rosario-Colon, J., Eberle, K., Adams, A., Courville, E. & Xin, H. Candida cell-surface-specific monoclonal antibodies protect mice against Candida auris invasive infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6162 (2021).

Torres, S. R. et al. Assessment of environmental and occupational exposure while working with multidrug resistant (MDR) fungus Candida auris in an animal facility. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 16, 507–518 (2019).

Borman, A. M. Of mice and men and larvae: Galleria mellonella to model the early host-pathogen interactions after fungal infection. Virulence 9, 9–12 (2017).

Romera, D. et al. The Galleria mellonella infection model as a system to investigate the virulence of Candida auris strains. Pathog. Dis. 78, ftaa067 (2020).

García-Carnero, L. C. et al. Early virulence predictors during the Candida species–Galleria mellonella interaction. J. Fungi 6, 152 (2020).

Garcia-Bustos, V. et al. Characterization of the differential pathogenicity of Candida auris in a Galleria mellonella infection model. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00013–e00021 (2021).

Carvajal, S. K. et al. Pathogenicity assessment of Colombian strains of Candida auris in the Galleria mellonella invertebrate model. J. Fungi 7, 401 (2021).

Hernando-Ortiz, A. et al. Virulence of Candida auris from different clinical origins in Caenorhabditis elegans and Galleria mellonella host models. Virulence 12, 1063–1075 (2021).

Spettel, K. et al. Candida auris in Austria—what is new and what is different. J. Fungi 9, 129 (2023).

Wurster, S. et al. Drosophila melanogaster as a model to study virulence and azole treatment of the emerging pathogen Candida auris. J. Antimicrobial. Chemother. 74, 1904–1910 (2019).

Harpf, V., Rambach, G., Würzner, R., Lass-Flörl, C. & Speth, C. Candida and complement: new aspects in an old battle. Front. Immunol. 11, 1471 (2020).

Pechacek, J. & Lionakis, M. S. Host defense mechanisms against Candida auris. Expert Rev. Anti Infec. Ther. 21, 1087–1096 (2023).

Johnson, C. J., Davis, J. M., Huttenlocher, A., Kernien, J. F. & Nett, J. E. Emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris evades neutrophil attack. mBio 9, e01403–e01418 (2018).

Pharkjaksu, S., Boonmee, N., Mitrpant, C. & Ngamskulrungroj, P. Immunopathogenesis of emerging Candida auris and Candida haemulonii strains. J. Fungi 7, 725 (2021).

Shapiro, R. S. & Cowen, L. E. Uncovering cellular circuitry controlling temperature-dependent fungal morphogenesis. Virulence 3, 400–404 (2012).

Leach, M. D. et al. Hsf1 and Hsp90 orchestrate temperature-dependent global transcriptional remodelling and chromatin architecture in Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 7, 11704 (2016).

Xiao, W. et al. Response and regulatory mechanisms of heat resistance in pathogenic fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 106, 5415–5431 (2022).

Arora, P. et al. Environmental isolation of Candida auris from the coastal wetlands of Andaman Islands, India. mBio 12, e03181–20 (2021).

Escandón, P. Novel environmental niches for Candida auris: isolation from a coastal habitat in Colombia. J. Fungi 8, 748 (2022).

Uden, V. & Kolipinski, M. C. Torulopsis haemulonii nov. spec., a yeast from the Atlantic Ocean. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 28, 78–80 (1962).

Bavia, L., Santiesteban-Lores, L. E., Carneiro, M. C. & Prodocimo, M. M. Advances in the complement system of a teleost fish, Oreochromis niloticus. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 123, 61–74 (2022).

Buchmann, K., Karami, A. M. & Duan, Y. The early ontogenetic development of immune cells and organs in teleosts. Fish. Shellfish Immunol. 146, 109371 (2024).

Tian, H. et al. Cytokine networks provide sufficient evidence for the differentiation of CD4+ T cells in teleost fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 141, 104627 (2023).

Akbarzadeh, A. & Leder, E. H. Acclimation of killifish to thermal extremes of hot spring: transcription of gonadal and liver heat shock genes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 191, 89–97 (2016).

Hamied, A. et al. Identification and characterization of highly fluorescent pigment cells in embryos of the Arabian killifish (Aphanius Dispar). iScience 23, 101674 (2020).

Alsakran, A. et al. Stage-by-stage exploration of normal embryonic development in the Arabian killifish. Aphanius dispar. Dev. Dyn. 254, 380–395 (2024).

Minhas, R. et al. The thermotolerant Arabian killifish, Aphanius dispar, as a novel infection model for human fungal pathogens. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.08.617174 (2024).

Gifford, H., Wilson, D., Rhodes, J. & Farrer, R. A. Seaside to bedside: assembly in research for emerging human fungal pathogen Candida auris. In Genome Assembly (ed. Farrer, R. A.) vol. 2955 263–291 (Springer US, 2025).

Burden, N., Chapman, K., Sewell, F. & Robinson, V. Pioneering better science through the 3Rs: an introduction to the national centre for the replacement, refinement, and reduction of animals in research (NC3Rs). J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 54, 198–208 (2015).

Skrzypek, M. S. et al. The Candida Genome Database (CGD): incorporation of assembly 22, systematic identifiers and visualization of high throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D592–D596 (2017).

Potrykus, J. et al. Fungal iron availability during deep seated candidiasis is defined by a complex interplay involving systemic and local events. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003676 (2013).

Kasper, L. et al. The fungal peptide toxin candidalysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4260 (2018).

Bonzi, L. C. et al. The time course of molecular acclimation to seawater in a euryhaline fish. Sci. Rep. 11, 18127 (2021).

Varma, A. et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterisation of a glucose transporter, CaHGT1, of Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182, 15–21 (2000).

Luo, L., Tong, X. & Farley, P. C. The Candida albicans gene HGT12 (Orf19.7094) encodes a hexose transporter. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51, 14–17 (2007).

Brown, V., Sexton, J. A. & Johnston, M. A glucose sensor in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 5, 1726–1737 (2006).

Larcombe, D. E. et al. Glucose-enhanced oxidative stress resistance-A protective anticipatory response that enhances the fitness of Candida albicans during systemic infection. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011505 (2023).

Martin, R. et al. A core filamentation response network in Candida albicans is restricted to eight genes. PLoS ONE 8, e58613 (2013).

Schatzman, S. S. et al. Copper-only superoxide dismutase enzymes and iron starvation stress in Candida fungal pathogens. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 570–583 (2020).

Rybak, J. M. et al. Abrogation of triazole resistance upon deletion of CDR1 in a clinical isolate of Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents and Chemother. 63, e00057–19 (2019).

Li, J., Coste, A. T., Bachmann, D., Sanglard, D. & Lamoth, F. Deciphering the Mrr1/Mdr1 pathway in azole resistance of Candida auris. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 66, e00067–22 (2022).

Sun, S., Coelho, M. A., David-Palma, M., Priest, S. J. & Heitman, J. The evolution of sexual reproduction and the mating-type locus: links to pathogenesis of Cryptococcus human pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Genet. 53, 417–444 (2019).

Wang, Y. & Xu, J. Population genomic analyses reveal evidence for limited recombination in the superbug Candida auris in nature. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 3030–3040 (2022).

Chow, N. A. et al. Potential fifth clade of Candida auris, Iran, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 25, 1780–1781 (2019).

Louvet, M. et al. Ume6-dependent pathways of morphogenesis and biofilm formation in Candida auris. Microbiol. Spectr. 0, e01531–24 (2024).

Deng, Y., Li, S., Bing, J., Liao, W. & Tao, L. Phenotypic switching and filamentation in Candida haemulonii, an emerging opportunistic pathogen of humans. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00779–21 (2021).

Overy, D. P., Rämä, T., Oosterhuis, R., Walker, A. K. & Pang, K.-L. The neglected marine fungi, Sensu stricto, and their isolation for natural products’ discovery. Mar. Drugs 17, 42 (2019).

Seiser, S. et al. Native human and mouse skin infection models to study Candida auris-host interactions. Microbes Infect. 26, 105234 (2024).

Fan, S. et al. Filamentous growth is a general feature of Candida auris clinical isolates. Med. Mycol. 59, 734–740 (2021).

Bravo Ruiz, G., Ross, Z. K., Gow, N. A. R. & Lorenz, A. Pseudohyphal growth of the emerging pathogen Candida auris is triggered by genotoxic stress through the S phase checkpoint. mSphere 5, e00151–20 (2020).

Kim, S. H. et al. Genetic analysis of Candida auris implicates Hsp90 in morphogenesis and azole tolerance and Cdr1 in Azole Resistance. mBio 10, e02529–18 (2019).

Gao, J. et al. LncRNA DINOR is a virulence factor and global regulator of stress responses in Candida auris. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 842–851 (2021).

Chybowska, A. D., Childers, D. S. & Farrer, R. A. Nine things genomics can tell us about Candida auris. Front. Genet. 11, 351 (2020).

Ismail, A., Bedell, G. W. & Lupan, D. M. Siderophore production by the pathogenic yeast, Candida albicans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 130, 885–891 (1985).

Heymann, P. et al. The Siderophore iron transporter of Candida albicans (Sit1p/Arn1p) mediates uptake of ferrichrome-type siderophores and Is required for epithelial invasion. Infect. Immun. 70, 5246–5255 (2002).

Boiteau, R. M. et al. Siderophore-based microbial adaptations to iron scarcity across the eastern Pacific Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14237–14242 (2016).

Park, J. et al. Siderophore production and utilization by marine bacteria in the North Pacific Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1636–1653 (2023).

Renshaw, J. C. et al. Fungal siderophores: structures, functions and applications. Mycol. Res. 106, 1123–1142 (2002).

Johnstone, T. C. & Nolan, E. M. Beyond iron: non-classical biological functions of bacterial siderophores. Dalton Trans. 44, 6320–6339 (2015).

Nakajima, Y. et al. Effect of disrupting the trichothecene efflux pump encoded by FgTri12 in the nivalenol chemotype of Fusarium graminearum. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 61, 93–96 (2015).

Xue, P. et al. Heme sensing and trafficking in fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 43, 100286 (2023).

Fourie, R., Kuloyo, O. O., Mochochoko, B. M., Albertyn, J. & Pohl, C. H. Iron at the Centre of Candida albicans Interactions. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8, 185 (2018).

Alselami, A. & Drummond, R. A. How metals fuel fungal virulence, yet promote anti-fungal immunity. Dis. Models Mech. 16, dmm050393 (2023).

Pradhan, A. et al. Non-canonical signalling mediates changes in fungal cell wall PAMPs that drive immune evasion. Nat. Commun. 10, 5315 (2019).

Weissman, Z. & Kornitzer, D. A family of Candida cell surface haem-binding proteins involved in haemin and haemoglobin-iron utilization. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1209–1220 (2004).

Ding, C. et al. Conserved and divergent roles of Bcr1 and CFEM proteins in Candida parapsilosis and Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 6, e28151 (2011).

Sharma, P. & Pasrija, R. Iron chelators enhance the potency of Echinocandins against Candida auris. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-7042978/v1 (2025).