Abstract

Cross-linking mass spectrometry has become a powerful technique for identifying protein interactomes and studying protein structures. We report the development of homo-bi-functional photo-activatable (BFPA) cross-linkers for cross-linking mass spectrometry. These cross-linkers theoretically react with any-to-any amino acid, overcoming limitations in amino acid reactivity. Different fragmentation energies and cross-linking conditions were tested, and the false discovery rate was benchmarked against a non-cross-linked sample and a false protein sequence search across different search engines. BFPA cross-linkers identified cross-links with better overall agreement with high resolution protein structures compared to randomized cross-links and compared to other commonly used cross-linkers. Different cross-link sites were identified by BFPA cross-linkers across bovine serum albumin, human importin complex and dengue protein complex, demonstrating its wide applicability to different protein complexes. BFPA have the potential to serve as complementary tools to current cross-linkers to expand the coverage of cross-linking mass spectrometry experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) has become a powerful technique to elucidate protein structures and for identification of protein-protein interaction networks1,2,3. XL-MS provides residue-to-residue cross-links and distance constraints which can be integrated with other structural inputs for integrative structural modelling4,5,6. While different developments of XL-MS methods have expanded its applications, cross-linker reactivity is still an important bottleneck that determines which amino acids can be cross-linked for downstream sample processing and data analysis. Commonly used amine-reactive cross-linkers (K-K), such as bis-(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) and disuccinimidyl sulfoxide (DSSO) have some side-reactivity with hydxoyl groups (S/T/Y-S/T/Y)7,8. Cross-linkers with different reactive chemistries have been developed, including carboxylic acid reactive (D/E-D/E)9,10,11, cysteine-reactive cross-linkers12 (C-C), aromatic glyoxal cross-linkers13 (R-R) and formaldehyde14 (K/R-K/R) with side reactivity (N/H/D/Y). Many of the 20 natural amino acids remain inert to cross-linker chemistries, which limits the potential of XL-MS for protein structure characterization. Current hetero-bi-functional photo-cross-linkers, such as succinimidyl 4,4’-azipentanoate (SDA), are still dependent on K/S/T/Y reactivity on one side while the photo-activatable diazirine can cross-link any amino acid15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Here, to achieve reactivity between any amino acid to any amino acid we report the development of homo-bi-functional photo-activatable cross-linkers (BFPA) for XL-MS.

Results

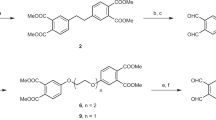

BFPA cross-linkers have two photoactivatable diazirine groups with spacer arms of different lengths, abbreviated as EBDA and BBDA for N,N’-(ethane-1,2-diyl)bis[3-(3-methyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)propanamide] and N,N’-(butane-1,4-diyl)bis[3-(3-methyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)propanamide] respectively (Figs. 1A, B, Supplementary Fig 1). The two diazirines generate a carbene intermediate that covalently cross-links to any proximal amino acid after UV photo-activation (Fig. 1C), forming cross-linked peptides identifiable by XL-MS. Diazirines react with O-H, N-H, S-H polar bonds with lower preference for C-H bonds18. We tested cross-linking conditions of BFPA cross-linkers on bovine serum albumin (BSA) proteins. Higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) energies of 25%, 35%, 45% and stepped 25/35/45% were tested, with HCD35% and 45% identifying higher number of cross-linked peptides (Figs. 1D, E). Testing of combinations of 1 mM, 10 mM cross-linker concentrations and 30, 60 min incubation times of cross-linker with protein before UV-activation identified 1 mM 60 min, 10 mM 30 min and 10 mM 60 min as more optimal conditions for cross-linked peptide identification (Fig. 1F, G). An average of 18, 17, 14 cross-linked peptides identified by EBDA and 10, 13, 9 cross-linked peptides identified by BBDA in 1 mM 60 min, 10 mM 30 min and 10 mM 60 min conditions respectively. To account for diazirine preference for acidic residues and its tendency to cleave under HCD conditions, we searched the 10 mM 30 min condition for acidic to acidic residues only for both cleavable and non-cleavable conditions (Supplementary Fig 2A, B). For both EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers, both cleavable and non-cleavable conditions identified similar number of cross-links. Similar peptide pairs were identified when comparing cross-linked identified by any to any residue search and acidic to acidic residue search (Supplementary Fig 2C, D), which could indicate ambiguity in cross-link site assignment. Additionally, the diazirine containing cross-linkers SDA, EBDA and BBDA had similar levels of mono-links based on modified diazirine groups (Supplementary Fig 2E, F).

A, B Bi-functional photo-activatable cross-linkers with differing spacer length for EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers respectively. C Proposed photo-activation cross-linking reaction of cross-linkers. D, E Comparison of HCD25%, HCD35%, HCD45% and step HCD 25/35/45% for cross-linked peptide identification of BSA cross-linked with EBDA and BBDA respectively. p-values < 0.05 from one-way ANOVA pair-wise comparison are shown. Mean value with standard deviation shown. Individual values shown as dots. F, G Comparison of number of cross-linked peptides identified by EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers respectively at 1 mM, 10 mM concentrations and with 30 min or 60 min pre-incubation times. p-values < 0.05 from one-way ANOVA pair-wise comparison are shown. Individual values from n = 3 cross-linking replicates shown as dots. Mean value with standard deviation shown.

Next, we compared BSA protein cross-links from DSSO, SDA and BFPA cross-linkers. 191, 54, 17 and 13 average cross-links were identified across 3 replicates from DSSO, SDA, EBDA and BBDA respectively, with a different cross-linking pattern produced by BFPA cross-linkers (Figs. 2A, B. Supplementary Data 1). To determine the structural accuracy of cross-links, we mapped cross-links to the BSA structure22 PDB: 4F5S (Figs. 2C, D). Due to the varying lengths of amino acid side-chains, we used both a general 30Å Cα-Cα distance constraint and an amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraint to account for the possible different lengths (Fig. 2E). A majority of cross-links were within the 30Å Cα-Cα distance constraint (Figs. 2F, G. Supplementary Data 2). A majority of EBDA and BBDA cross-links satisfied both the 30Å and amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraints, indicating good agreement between identified cross-links and structure. Lysines, K, accounted for 78.43% of DSSO cross-link sites, 36.11% for SDA and 6.86% and 6.25% for EBDA and BBDA respectively (Fig. 2H, Supplementary Data 3). Acidic residues (D, E) accounted for 24.51% and 27.50% of EBDA and BBDA cross-link sites while cysteine accounted for 1.96% and 8.75% of EBDA and BBDA cross-link sites respectively. Other amino acids I, L, A, T were the most frequently cross-linked amino acids for EBDA and BBDA. Amino acids with charged side chains (E,D,K), hydrophilic side chains (S,T,Y), short side chains (A, I, L) and hydrophobic side chains (P, F) were cross-linked, indicating a broad reactivity of the BFPA cross-linkers.

A, B Cross-links on BSA sequence for DSSO (blue), SDA (purple), EBDA (green) and BBDA (orange) cross-links. Lysine amino acids are marked in red. C, D Cross-links mapped to BSA structure (PDB: 4F5S). E Cross-link Cα-Cα distance constraint should be adjusted to account for different amino acid side-chain lengths. F Distribution of Cα-Cα distances of identified cross-links. G Percentage of cross-links mapped onto PDB: 4F5S which satisfied (blue) or violated (red) a 30 Å distance constraint or adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraint. Bars are labelled with number of satisfied/violated cross-links. H Frequency of amino acid cross-link sites by percentage (%) of all cross-link sites. I Comparison of cross-links identified by MeroX, xiSEARCH+xiFDR and Metamorpheus. Individual values from n = 3 cross-link replicates shown as dots. Mean value with standard deviation shown. J Comparison of BSA cross-links identified from non cross-linked BSA sample (false sample) across different search engines. Individual values from n = 3 cross-link replicates shown as dots. Mean value with standard deviation shown. K Comparison of non-BSA cross-links identified with Enolase sequence added (false sequence) across different search engines. Individual values from n = 3 cross-link replicates shown as dots. Mean value with standard deviation shown.

We further compared the results from three different search engines, MeroX23, xiSEARCH filtered with xiFDR24, Metamorpheus25. (Fig. 3I, Supplementary Fig 2G, 3A). xiSEARCH identified the highest number of cross-links while Metamorpheus identified the lowest number of cross-links. 7 EBDA cross-linked peptides and 3 BBDA cross-linked peptides were identified from 2 or more replicates by both MeroX and xiSEARCH. We benchmarked the false positive identification rate of the three search engines against a non-cross-linked sample. This false sample should contain only linear peptides, so false identifications would be a result of identifying cross-linked peptides from non cross-linked spectra (Fig. 2J). xiSEARCH identified the highest number of cross-links from the false sample while Metamorpheus identified the lowest number. A further benchmark of the false discovery rate from a false sequence was performed. Yeast enolase sequence was added to the database search space, and false identifications would be a result of identifying non-BSA peptide sequences as cross-linked spectra (Fig. 2K). xiSEARCH identified the lowest number of cross-links, while MeroX and Metamorpheus identified comparable number of cross-links from the false sequence.

A–C Importin complex (KPNA2-KPNB1) cross-links by DSSO (blue, left), SDA (purple, center), EBDA (green, right) and BBDA (orange, right). Red: IBB domain. Purple: NLS binding domains. Yellow: HEAT repeat regions that are cross-linked. D–F Structure of importin alpha-1 IBB domain in pink interacting with importin beta in grey (PDB: 1QGK). DSSO, SDA EBDA/BBDA cross-links mapped to structure. G–I Structure of full-length importin alpha-1 in pink interacting with importin beta in grey predicted by Alphafold Multimer. J, K Plot of percentage of cross-links which satisfy 30 Å distance constraint or amino acid adjusted distance constraint respectively for 1QGK structure and AlphaFold predicted structures. pTM scores are listed below the rank of the AlphaFold model. L Amino acid frequency of cross-link sites for Importin complex cross-links from DSSO (blue), SDA (purple), EBDA (green) and BBDA (orange) cross-linkers.

The BFPA cross-linkers were used to study the human importin-alpha-1 (KPNA2) interaction with human importin-beta (KPNB1)26,27. KPNA2 importin-beta binding (IBB) domain interacts with HEAT repeats 7 to 19 of KPNB1, while HEAT repeats 1 to 6 of KPNB1 mediate interactions with Ran28. KPNA2 also interacts with protein nuclear localization signal (NLS) through the NLS binding domains. We identified an average of 233, 52, 28 and 29 cross-linked peptides from three replicates for DSSO, SDA, EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers respectively by MeroX (Fig. 3A, C. Supplementary Data 1). Cross-links were identified between the IBB domain and different HEAT repeats among the different cross-linkers, indicating a different cross-link pattern. We mapped cross-links to a published crystal structure which contained only the IBB domain of KPNA2 interacting with KPNB128 (PDB: 1QGK) (Fig. 3D–F). We used AlphaFold to predict the structure of non-IBB domains of KPNA2 and mapped cross-links to the predicted structure (Fig. 3G–I). BFPA cross-links showed better general agreement compared to DSSO and SDA for both 30Å and amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraints for both the crystal structure and the AlphaFold predicted full-length structure (Fig. 3J, K. Supplementary Fig 3F, 3G. Supplementary Data 2). The most frequently cross-linked amino acid sites are E, I, N for EBDA and I, V, E, D for BBDA (Fig. 3L. Supplementary Data 3), with acidic residues (D, E) accounting for 20.34% and 21.19% of cross-link sites for EBDA and BBDA respectively.

The BFPA cross-linkers were further applied to Denv4 proteins, NS2B and NS3 protease domain. The Denv4 NS2B belt interaction with NS3 protease domain were previously cross-linked with DSSO and mapped to a solved crystal structure (PDB: 7VMV)29. Here, we acquired new SDA, EBDA and BBDA XL-MS data on the eNS2B47NS3Pro constructs previously studied (Fig. 4A, B. Supplementary Data 1). Average of 35, 14, 39 cross-links were identified from 3 replicates by MeroX for SDA, EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers respectively. EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers identified cross-links from NS2B aa44-52 region to NS3 aa1-15, aa60-66, aa160-166 regions. Cross-links to NS3 aa160-166 were not identified in DSSO or SDA cross-linked samples. (Fig. 4A–F) Cross-links by EBDA and BBDA for NS2B aa44-52 to NS3 aa60-66 is situated in a different structural position from DSSO cross-links from NS2B S48 to NS3 S56 (Fig. 4C–F), indicating ability of BFPA cross-linkers to identify new and different protein interacting regions from current conventionally used cross-linkers. EBDA and BBDA cross-links satisfied both the 30Å and amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraints, indicating good agreement between cross-links and structure (Fig. 4G). Acidic residues (D, E) accounted for 30.43% and 15.52% of cross-link sites for EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers respectively (Fig. 4H). Apart from acidic amino acids, the most frequently cross-linked amino acids were M and S for EBDA and S, A, L for BBDA.

A, B Denv4 NS2b-NS3 cross-links for DSSO (blue), SDA (purple) and EBDA (green), BBDA (orange). Orange: Lysine amino acids. * Denotes NS3 aa55-65, ** Denotes NS3 aa160-166, *** Denotes NS3 aa1-15. C–F NS2B to NS3-protease crystal structure (PDB: 7VMV) with DSSO (blue), SDA (purple), EBDA (green) and BBDA (orange) cross-links mapped respectively. * Denotes NS3 aa55-65, ** Denotes NS3 aa160-166, *** Denotes NS3 aa1-15. G Percentage and number of cross-links mapped onto PDB: 7VMV which satisfy 30 Å distance constraint or adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraint. Bars are labelled with number of satisfied/violated cross-links. H Amino acid frequency of cross-link sites for Denv4 Ns2b-NS3 cross-links from DSSO (blue), SDA (purple), EBDA (green) and BBDA (orange) cross-linkers. I, J Comparison between experimental data, randomized cross-link site (same peptide pair, randomized cross-link site) and randomized cross-link (randomized peptide pair and ranodmized cross-link site) for EBDA and BBDA respectively. Both 30 Å and adjusted distance constraints are compared for BSA, KPNA2-KPNB1 complex and NS2B-NS3 complex. Individual values from n = 3 randomized cross-links datasets shown as dots. Mean value with standard deviation shown.

To account for possible ambiguity in cross-link site assignment, we compared structure mapping of cross-links with that of randomly generated cross-links. We generated two random sets of cross-links. The first set are randomized cross-link sites, with experimental peptide pairs used and cross-linked sites were randomized based on the peptide pair sequences. The second set are randomized cross-linked peptide + randomized cross-linked site. Theoretical tryptic peptides were randomly chosen to make up peptide pairs, and cross-linked sites on these peptide pairs were randomly generated. Three randomizations were generated and compared to the experimental data (Figs. 4I, J, Supplementary Data 1). For both EBDA and BBDA across the three protein complexes, the experimental cross-links had better satisfaction of both the 30Å and amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraints compared to the randomized cross-links. These results indicate a better fit of the experimental cross-links with structural data compared to random cross-links.

Discussion

The BFPA cross-linkers utilize diazirine functional groups, which are activated by UV irradiation to form a carbene that reacts in a nonspecific manner18. The activated diazirine may also isomerize to a diazo compound which reacts with carboxylic acids to form esters that are MS-cleavable18. Our analysis of the BFPA cross-linkers showed characteristics expected of diazirine chemistry. Across BSA, importin complex and Denv4 NS2B-NS3 protein complex, acidic residues (D, E) account for ~15–30% of cross-linked residues, NHS-reactive amino acids (K, S, T, Y) for ~15–23% of cross-linked residues while C and R accounted for ~1–8% and ~0–3% of cross-linked residues respectively. These results indicate that diazirine containing EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers do have a preference for acidic residues. Comparison of search identifications for any-to-any and acidic-to-acidic showed that similar peptide pairs were identified (Supplementary Fig 2B, D). Given that diazirines react with any amino acid with some preference for acidic residues, there indicates some ambiguity in assignment of cross-link sites from identified cross-links. We are not able to rule out the possibility that any-to-any amino acid is cross-linked. Identified any-to-any cross-link sites do have better structural accuracy compared to randomized cross-links (Figs. 4I, J), indicating that the ambiguity in cross-link site assignment is not random. The ambiguity could be due to incomplete fragmentation of the cross-linked peptide. Additionally, search of acidic-to-acidic cross-links as MS-cleavable or non-cleavable seemed to identify similar peptide pairs, with comparable numbers of identified cross-links. The BFPA cross-linkers also exhibit similar mono-link characteristics as SDA16,17, with similar identification rates of quenched diazirine species as mono-links (Supplementary Fig 2F). Reaction with Tris mono-links was much higher in SDA compared to EBDA and BBDA, which could be due to reaction of Tris with the NHS-ester of SDA that is not present in EBDA or BBDA (Supplementary Fig 2F). Overall, our results show clearly that the BFPA cross-linkers exhibit characteristics of diazirine-based chemical cross-linking.

Comparison of BFPA cross-linkers with DSSO and SDA show fewer number of cross-link identifications. Diazirines can be quenched by water, and a homo-bi-functional diazirine cross-linker is expected to have a large majority of molecules reacting with water, leaving a small minority of molecules to react with protein30. To mitigate this, we used a pre-incubation step to allow the BFPA cross-linkers to complex with proteins before UV-irradiation. In contrast, SDA cross-linkers first react the NHS-ester with amines to bring the diazirine group into proximity of the protein before UV-irradiation. Hence, the lower number of cross-link identifications of BFPA cross-linkers is likely due to solvent quenching, with possible contributions from limitations of sensitivity or photo-activation. Here, we used longer 30–60 min photo-activation time for diazirines which is comparable to 15–60 min photo-activation times reported by different cross-linking mass spectrometry applications of diazirine-based cross-linkers12,16,17,31. Use of UV-LED lamps could shorten the photo-activation time needed20. Both EBDA and BBDA cross-links showed a charge distribution mainly across +3, +4 and +5 charges (Supplementary Fig 2J, K). We benchmarked the false positive identification rate associated with false identifications of non-cross-linked peptides (Fig. 2J) and false identifications of protein sequences (Fig. 2K) showing that there is a small number of false identifications from both sources across different search engines. Recent studies have benchmarked the false error rate of MeroX to be higher32 or comparable33 to other search engines. Our own comparison shows that MeroX has a comparable or lower false identification rate, but our comparison is limited to cross-linked purified proteins of a single or heterodimer complex instead of cross-linked proteins from a complex proteome. The rate of false identifications is lower than the number of identified cross-links for EBDA and BBDA, increasing confidence in the identification of EBDA and BBDA cross-links. Additionally, 4, 10 and 7 cross-linked peptides were identified by MeroX from 2 or more replicates by both EBDA and BBDA for BSA, KPNA2-KPNB1 complex and NS2B-NS3 complex respectively (Supplementary Fig 2G–I), indicating concordance between the two cross-linkers despite a small difference in spacer arm length ( ~ 2Å difference). Despite the relatively high false positive identification rate for BFPA cross-linkers, cross-links identified from EBDA and BBDA show good agreement with high resolution structures across the proteins tested: BSA, importin complex, Denv4 NS2B-NS3 complex (Figs. 2G, 3I, J and 4G). To account for difference in amino acid side-chain lengths and the ability of the non-specific cross-linking of BFPA cross-linkers, we calculated an amino acid adjusted distance constraint for Cα-Cα distance. EBDA and BBDA cross-links satisfied both the 30Å and the more stringent amino acid adjusted Cα-Cα distance constraint across the protein complexes tested. Additionally, experimental cross-links satisfied both Cα-Cα distance constraint criteria compared to randomized cross-link sites and randomized cross-linked peptides + cross-link sites, indicating a higher structural accuracy of identified cross-links over random cross-links.

BFPA cross-linkers, EBDA and BBDA, were tested on proteins from different species, including bovine serum albumin, human importin complex (KPNA2-KPNB1) and dengue serotype 4, Denv4 NS2B-NS3. Interaction of human importin-alpha to importin-beta is necessary for the nuclear localization of proteins26,27. Available structures contain only the IBB domain of KPNA2 interacting KPNB1 and AlphaFold was used to predict the full-length sequence structure of KPNA2 interacting with KPNB1. BFPA cross-links showed a better satisfaction of the AlphaFold prediction of the full-length structure compared to DSSO or SDA cross-links, indicating that BFPA cross-linkers may be better able to capture the structure of the importin complex. Further work can be done to utilize the BFPA cross-linkers to study the structures of the importin complex and its various binding partners. The better satisfaction of high-resolution structure is also observed for BFPA cross-links of the Denv4 NS2B-NS3 complex. NS2B loop to NS3 protease interaction is important for its role in replication and assembly of the dengue virus29,34. BFPA cross-links additionally identify cross-links to NS3 aa1-15 and aa160–166 region that are not observed by DSSO, indicating that BFPA cross-linkers can be used to complement current cross-linkers for additional sequence coverage. Comparison of BFPA cross-link sites with DSSO and SDA shows a varied and different coverage (Supplementary Fig 3A–E). Given the lower sensitivity and lower number of identified BFPA cross-links, we recommend the use of BFPA cross-linkers as a complement to other cross-linkers to increase the cross-link coverage of the overall protein sequence.

Our results demonstrate that BFPA cross-linkers can increase amino acid coverage of protein structure analysis using XL-MS. The results presented are a first step towards further development of chemically non-specific cross-linkers which can cross-link any amino acid to any amino acid for a universal approach to protein structure analysis by XL-MS. The BFPA cross-linkers have limitations in sensitivity, identification and ambiguity in cross-link site assignment but provides structural data coherent with high resolution structures that can be used for structural analysis. Use of these cross-linkers with XL-MS for protein structure analysis will complement current cross-linkers to enable further biological and functional insights into the interactions of disease related protein complexes.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Bovine serum albumin was purchased from Sigma (A9418-10G). Full-length IMA1 (KPNA2) and IMB1 (KPNB1) coding sequences were subcloned into the pNIC28-Bsa4 expression vector35. Expression plasmids were transformed into the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) Rosetta strain. Expression cultures in terrific broth were grown in the presence of 34 µg/mL chloramphenicol and 50 µg/mL kanamycin at 37 °C to an optical density of 2. Cultures were then cooled to 18 °C and overexpression was induced by adding 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside IPTG. Cells were harvested after 18 h, resuspended in lysis buffer (100 mM HEPES, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM Imidazole, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP, pH 8.0) and subjected to sonication. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 45000 g. Lysate supernatants were then filtered and subjected to standard Ni-NTA purification followed by size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep grade column (Cytiva). Fractions containing desired proteins were pooled and concentrated to approx 10 mg/mL. The final buffer was 20 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5. Protein purification of Denv4 NS2B and NS3 protease was performed as previously described29. Briefly, protein plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli Rosetta T1R cells and grown with Luria Broth (LB) medium overnight at 37 °C until an OD600 of 0.8–1.0. 1 mM IPTG was added to induce protein overexpression. Cells were harvested after 18 h, resuspended in resuspension buffer (1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 160 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Cells were lysed by sonication, homogenised then centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 1 h at 4 °C. Supernatant was collected and incubated for 1.5 h at 4 °C with Ni-NTA beads. Beads were washed with resuspension buffer containing 20–40 mM imidazole, and proteins were eluted with resuspension buffer with 300 mM imidazole. Elutes were cleaved by TEV protease followed by dialysis overnight. Flow-through from Ni-NTA beads was collected. Purification was performed using HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg (GE Healthcare) column followed by centrifugation through 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off Amicon centrifugal filter units. Purified proteins were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen.

Cross-linking and sample preparation for mass spectrometry

Bi-functional photo-activatable cross-linkers were obtained from Enamine through a custom synthesis request (Enamine EN300-45646017, EN300-45646016). DSSO cross-linker was obtained from Thermo Scientific (A33545). Dry powder cross-linkers were dissolved in DMSO to 100 mM concentration. Cross-linking with SDA, EBDA and BBDA cross-linkers was performed in amber tubes to reduce exposure to light. Three biological replicates were prepared and cross-linked for each condition. Chemical structures were drawn using ACD/ChemSketch.

For cross-linking of purified proteins, 50 µg of proteins were made up to 45 µl in 50 mM HEPES pH7.4, 150 mM NaCl buffer. 5 µl of 100 mM cross-linker in DMSO was added and mixed. For optimization experiment, 5 µl of 10 mM cross-linker or 5 µl of 100 mM cross-linker was added and mixed (final 1 mM or 10 mM). For DSSO, proteins were incubated for 60 min at 25 °C, followed by quenching with addition of 5 µl of 1 M Tris buffer, pH8 and incubation for 15 min at 25 °C. For SDA, EBDA and BBDA, proteins were incubated for 30 min at 25 °C in the dark before activation of diazirine groups with a UV Lamp (Fisher UVP 95034301) at 365 nm for 60 min (8 W lamp at 3–5 cm distance from sample). Incubation times of 30 min or 60 min before UV activation were tested. 5 µl of 1 M Tris buffer was added and proteins were transferred to clear tubes before proceeding.

After cross-linking, proteins were denatured by addition of 50 µl 8 M urea in 50 mM TEAB. Proteins were reduced by addition of TCEP to 10 mM concentration and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. Proteins were then alkylated by addition of CAA to 55 mM concentration and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C in the dark. 200 µl of 100 mM TEAB was added to the solution before addition of 1 µg of LysC and incubation for 4 h at 37 °C. 150 µl of 100 mM TEAB was then added before addition of 1 µg of trypsin and incubation for 16 h at 37 °C. Digested peptides were acidified by addition of 10% TFA to final 1% concentration.

Peptides were then desalted using Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters 186000383). Cartridges were activated with 200 µl acetonitrile, conditioned by passing 200 µl of 0.1% formic acid in water through twice. Peptides were then loaded onto the cartridge before washing with 200 µl of 0.1% formic acid in water twice. Peptides were then eluted with 200 µl of 65% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid in water. Eluted peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation and stored at -20 °C before mass spectrometry analysis.

Cross-linking mass spectrometry acquisition and data analysis

Dried peptides were reconstituted in 2% acetonitrile, 0.5% acetic acid, 0.06% trifluoroacetic acid in LC-MS grade water to 0.5 µg/µl concentration. 2 µl of peptides were loaded onto a Easy-Spray 75 µm x 50 cm column on a VanquishNeo UHPLC (Thermo) system coupled to a Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo) with an Easy-Spray source. Peptides were resolved with a 300 nl/min flow rate with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and mobile phase B (80% acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid) with a resolving gradient as follows: 0-3% B for 2 min, 3-42% B for 60 min, 42–60% B for 6 min, 60-100% B for 2 min, 100% B for 5 min, followed by column equilibration at 0% B. Mass Spectra was collected in Data-Dependent Acquisition with a MS1 scans performed in the Orbitrap with a scan range of 400–1600 m/z at 60 K resolution, AGC target of 400,000 and maximum injection time of 50 ms. MS2 scans were selected based on charge state of +3-8, and dynamic exclusion of 90 s. MS2 scans were acquired in the Orbitrap at 30 K resolution, AGC target of 50,000, maximum injection time of 100 ms and activation type of HCD. Different HCD normalized collision energies were tested, including 25%, 35%, 45% and stepped 25,35,45%.

Mass spectra raw files were converted to .mzML or .mgf format using MSConvert (Proteowizard)36. For MeroX23 v2.0.1.4 searches, quadratic mode with variable modifications for methionine oxidation ( + 15.9949 Da) and cysteine alkylation ( + 57.0215 Da) was used. Up to 3 missed cleavages, precursor precision of 10 ppm and fragment ion precision of 20 ppm with FDR cutoff of 1%, no score cutoff and no prescore filter using simple, very fast scoring settings were used. For xiSEARCH24 v1.8.7 searches, variable modifications for methionine oxidation and cysteine alkylation was used. Up to 3 missed cleavages, precursor precision of 10ppm and fragment ion precision of 20 ppm and default 5% residue pair xiFDR setting was used. Linear modifications were searched for EBDA loop (224.1524 Da), oxid (240.1473 Da), hydro (242.1630 Da), alkene (210.1368 Da) and tris (345.2263 Da) modifications and for BBDA loop (252.1837 Da), oxid (268.1786 Da), hydro (270.1943 Da), alkene (238.1681 Da) and tris (373.2576 Da) modifications. For Metamorpheus25 v1.0.1 searches, variable modifications for methionine oxidation and cysteine alkylation was used. Up to 3 missed cleavages, precursor precision of 10ppm and fragment ion precision of 20ppm with q-value cutoff of 1% was used. For DSSO, cross-linker monoisotopic mass of 252.1838 Da was used with site specificity of protein N-terminus, K, S, T and Y for site 1 and site 2. For fragmentation, alkene fragment of 54.0106 Da and thiol fragment of 85.9826 were selected as essential for site 1 and site 2. For SDA, cross-linker monoisotopic mass of 82.0413 was used with site specificity for K, S, T and Y for site 1 and any amino acid for site 2. For EBDA, cross-linker monoisotopic mass of 224.1525 was used with site specificity for any amino acid for site 1 and site 2. For BBDA cross-linker settings, cross-linker monoisotopic mass of 252.1838 was used with site specificity of amino acid for site 1 and site 2.

Cross-link search output was plotted using Graphpad prism v10.1.2. Cross-link circular plots and sequence plots were made using xiVIEW37. PyXlinkViewer38 was used to map cross-links to PDB structures in Pymol39 v.2.5.5 and to determine cross-link Cα-Cα distances in PDB structures.

Alphafold structural prediction

Interacting structure of full-length KPNA2 to KPNB1 was predicted using alphafold2 multimer v3 via ColabFold40,41,42. PDB: 1QGK structure28, which contains KPNB1 and IBB region of KPNA2, was used as the template with input of KPNA2 and KPNB1 full-length sequences using default settings. Top 5 ranked predicted models had interface predicted template modelling (ipTM) scores above 0.6 (Fig. 3J, K).

Statistics and reproducibility

3 cross-link replicates were used for all experiments and comparisons in this study. One-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons was performed through GraphPad Prism for comparison of different cross-linking conditions.

Data availability

Raw mass spectrometry spectra and search data have been deposited at ProteomeXchange43 (PXD056634) and JPost44 repository (JPST003413). AlphaFold predicted structures have been deposited at https://zenodo.org (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13902775). Source data for graphs are provided in Supplementary Data 1-3. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

O’Reilly, F. J. & Rappsilber, J. Cross-linking mass spectrometry: methods and applications in structural, molecular and systems biology. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 1000–1008 (2018).

Chavez, J. D. et al. Chemical Crosslinking Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Protein Conformations and Supercomplexes in Heart Tissue. Cell Syst. 6, 136–141.e135 (2018).

Gonzalez-Lozano, M. A. et al. Stitching the synapse: Cross-linking mass spectrometry into resolving synaptic protein interactions. Sci. Adv. 6, eaax5783 (2020).

Chavez, J. D. & Bruce, J. E. Chemical cross-linking with mass spectrometry: a tool for systems structural biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 48, 8–18 (2019).

Ziemianowicz, D. S. et al. IMProv: A Resource for Cross-link-Driven Structure Modeling that Accommodates Protein Dynamics. Mol. Cell Proteom. 20, 100139 (2021).

Chen, Z. A. & Rappsilber, J. Protein structure dynamics by crosslinking mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 80, 102599 (2023).

Iacobucci, C. et al. First Community-Wide, Comparative Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry Study. Anal. Chem. 91, 6953–6961 (2019).

Kao, A. et al. Development of a novel cross-linking strategy for fast and accurate identification of cross-linked peptides of protein complexes. Mol. Cell Proteom. 10, M110 002212 (2011).

Leitner, A. et al. Chemical cross-linking/mass spectrometry targeting acidic residues in proteins and protein complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9455–9460 (2014).

Gutierrez, C. B. et al. Developing an Acidic Residue Reactive and Sulfoxide-Containing MS-Cleavable Homobifunctional Cross-Linker for Probing Protein-Protein Interactions. Anal. Chem. 88, 8315–8322 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Carboxylate-Selective Chemical Cross-Linkers for Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Protein Structures. Anal. Chem. 90, 1195–1201 (2018).

Gutierrez, C. B. et al. Development of a Novel Sulfoxide-Containing MS-Cleavable Homobifunctional Cysteine-Reactive Cross-Linker for Studying Protein-Protein Interactions. Anal. Chem. 90, 7600–7607 (2018).

Jones, A. X. et al. Improving mass spectrometry analysis of protein structures with arginine-selective chemical cross-linkers. Nat. Commun. 10, 3911 (2019).

Tayri-Wilk, T. et al. Mass spectrometry reveals the chemistry of formaldehyde cross-linking in structured proteins. Nat. Commun. 11, 3128 (2020).

Dubinsky, L., Krom, B. P. & Meijler, M. M. Diazirine based photoaffinity labeling. Bioorg. Med Chem. 20, 554–570 (2012).

Giese, S. H., Belsom, A. & Rappsilber, J. Correction to Optimized Fragmentation Regime for Diazirine Photo-Cross-Linked Peptides. Anal. Chem. 89, 3802–3803 (2017).

Giese, S. H., Belsom, A. & Rappsilber, J. Optimized Fragmentation Regime for Diazirine Photo-Cross-Linked Peptides. Anal. Chem. 88, 8239–8247 (2016).

Iacobucci, C. et al. Carboxyl-Photo-Reactive MS-Cleavable Cross-Linkers: Unveiling a Hidden Aspect of Diazirine-Based Reagents. Anal. Chem. 90, 2805–2809 (2018).

Brodie, N. I., Makepeace, K. A., Petrotchenko, E. V. & Borchers, C. H. Isotopically-coded short-range hetero-bifunctional photo-reactive crosslinkers for studying protein structure. J. Proteom. 118, 12–20 (2015).

Faustino, A. M., Sharma, P., Manriquez-Sandoval, E., Yadav, D. & Fried, S. D. Progress toward Proteome-Wide Photo-Cross-Linking to Enable Residue-Level Visualization of Protein Structures and Networks In Vivo. Anal. Chem. 95, 10670–10685 (2023).

Gutierrez, C. et al. Enabling Photoactivated Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Protein Complexes by Novel MS-Cleavable Cross-Linkers. Mol. Cell Proteom. 20, 100084 (2021).

Bujacz, A. Structures of bovine, equine and leporine serum albumin. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 68, 1278–1289 (2012).

Iacobucci, C. et al. A cross-linking/mass spectrometry workflow based on MS-cleavable cross-linkers and the MeroX software for studying protein structures and protein-protein interactions. Nat. Protoc. 13, 2864–2889 (2018).

Mendes, M. L. et al. An integrated workflow for crosslinking mass spectrometry. Mol. Syst. Biol. 15, e8994 (2019).

Lu, L. et al. Identification of MS-Cleavable and Noncleavable Chemically Cross-Linked Peptides with MetaMorpheus. J. Proteome Res. 17, 2370–2376 (2018).

Mahipal, A. & Malafa, M. Importins and exportins as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharm. Ther. 164, 135–143 (2016).

Weis, K. Importins and exportins: how to get in and out of the nucleus. Trends Biochem Sci. 23, 185–189 (1998).

Cingolani, G., Petosa, C., Weis, K. & Muller, C. W. Structure of importin-beta bound to the IBB domain of importin-alpha. Nature 399, 221–229 (1999).

Quek, J. P. et al. Dynamic Interactions of Post Cleaved NS2B Cofactor and NS3 Protease Identified by Integrative Structural Approaches. Viruses 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14071440 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Dissecting diazirine photo-reaction mechanism for protein residue-specific cross-linking and distance mapping. Nat. Commun. 15, 6060 (2024).

Kleiner, R. E., Hang, L. E., Molloy, K. R., Chait, B. T. & Kapoor, T. M. A Chemical Proteomics Approach to Reveal Direct Protein-Protein Interactions in Living Cells. Cell Chem. Biol. 25, 110–120.e113 (2018).

Clasen, M. A. et al. Proteome-scale recombinant standards and a robust high-speed search engine to advance cross-linking MS-based interactomics. Nat. Methods 21, 2327–2335 (2024).

Beveridge, R., Stadlmann, J., Penninger, J. M. & Mechtler, K. A synthetic peptide library for benchmarking crosslinking-mass spectrometry search engines for proteins and protein complexes. Nat. Commun. 11, 742 (2020).

Falgout, B., Pethel, M., Zhang, Y. M. & Lai, C. J. Both nonstructural proteins NS2B and NS3 are required for the proteolytic processing of dengue virus nonstructural proteins. J. Virol. 65, 2467–2475 (1991).

Savitsky, P. et al. High-throughput production of human proteins for crystallization: the SGC experience. J. Struct. Biol. 172, 3–13 (2010).

Chambers, M. C. et al. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 918–920 (2012).

Combe, C.W. Graham, M. Kolbowski, L. Fischer, L. & Rappsilber, J. xiVIEW: Visualisation of crosslinking mass spectrometry data. J. Mol. Biol. 17, 168656 (2024).

Schiffrin, B., Radford, S. E., Brockwell, D. J. & Calabrese, A. N. PyXlinkViewer: A flexible tool for visualization of protein chemical crosslinking data within the PyMOL molecular graphics system. Protein Sci. 29, 1851–1857 (2020).

Schrodinger, L. L. C. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 (2015).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Evans, R. et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.04.463034 (2022).

Deutsch, E. W. et al. The ProteomeXchange consortium at 10 years: 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1539–D1548 (2023).

Okuda, S. et al. jPOSTrepo: an international standard data repository for proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D1107–D1111 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by an A*STAR Career Development Fund (Project ID: 212D800074). Z.S. is supported by an A*STAR Career Development Fund and an A*STAR Young Achiever Award. R.M.S. is supported by A*STAR Core funding and by Singapore National Research Foundation under its NRF-SIS “SingMass” scheme. We thank the NTU Protein Production Platform (https://proteins.sbs.ntu.edu.sg/) for producing recombinant IMA1 (KPNA2) and IMB1 (KPNB1) proteins. We thank Subhash Vasudevan and Wint Wint Phoo for providing purified Denv4 NS2B-NS3 protease proteins.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. conceived and designed the study, performed cross-linking mass spectrometry experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. S.M.W. and A.G.M.O. performed cross-linking mass spectrometry experiments. R.M.S. provided supervision and aided in conceiving and designing the study.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Laura Rodriguez Perez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ser, Z., Ong, A.G.M., Wang, S.M. et al. Towards a universal cross-linking mass spectrometry approach for protein structure analysis with homo-bi-functional photo-activatable cross-linkers. Commun Biol 9, 128 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09407-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09407-8