Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection typically resolves within weeks, but rare cases of prolonged replication—sometimes exceeding a year—have been documented, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. These persistent infections pose health risks and may give rise to highly divergent variants, yet the underlying biology remains poorly understood. Here, we describe a model of SARS-CoV-2 persistence using transgenic Syrian hamsters (males) lacking the interleukin-2 receptor gamma subunit (IL2rg). Infection with the XBB.1.16 variant led to efficient viral replication in respiratory tissues by two weeks after infection, with dissemination to other sites, including the intestinal tract. Viral titers remained high in multiple tissues at 100 days after infection. Longitudinal oral swab sequencing revealed dynamic shifts in intrahost single-nucleotide variant (iSNV) frequencies, with constellations of iSNVs rising and falling together, consistent with strong genetic linkage. Synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations accumulated at similar rates, suggesting genetic drift as the dominant evolutionary force. Tissue- and swab-derived sequences revealed extensive within-host diversity and hinted at tissue-specific evolutionary trajectories. This model enables detailed investigation of SARS-CoV-2 persistence and within-host viral evolution and provides a controlled system to study how long-term replication in tissue reservoirs may contribute to viral diversification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In typical SARS-CoV-2 infections, the virus is cleared from the upper respiratory tract within 10 days of symptom onset, and viral RNA is cleared within 30 days1,2. However, in some instances, infection can persist substantially longer. A longitudinal study in the United Kingdom enrolling over 70,000 individuals found evidence for persistent viral RNA shedding lasting at least two months in upper respiratory tract samples in 0.1–0.5% of participants3. Individuals with immunocompromising conditions such as congenital immune deficiencies or untreated HIV infection, or those on immunosuppressive regimens, such as transplant recipients or people with hematologic malignancies, are at increased risk for SARS-CoV-2 persistence4,5. B-cell deficiencies, due to immunosuppressive treatments or uncontrolled HIV infection, appear to confer the highest risk for persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection5,6. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality for immunocompromised people due to the lack of effective, evidence-based treatment options for this population. Such infections are also a concern for broader public health, as they are thought to be a major source of highly divergent new SARS-CoV-2 variants7,8. In support of this hypothesis, we and others have shown that SARS-CoV-2 can accumulate mutations consistent with immune escape in persistently infected individuals and that the substitution rate may be accelerated in persistent infections9,10,11.

SARS-CoV-2 can disseminate to a range of tissue sites during acute infection12,13, and persistent replication in various tissues could lead to the evolution of different viral lineages within the same host10,13,14,15,16. However, it is difficult to study viral replication and evolutionary dynamics in tissue sites in humans, particularly when the participants likely to have persistent infections are immunocompromised and often medically fragile. Moreover, persistent infections are relatively rare, even among immunocompromised persons, making it difficult for any single center to establish cohorts of immunocompromised individuals in numbers that give sufficient power to resolve potential associations between parameters like type and degree of immune deficiency and virus strain on infection outcomes and viral evolutionary dynamics. Nonetheless, it is essential that we improve our understanding of the pathology of SARS-CoV-2 persistence and the dynamics of within-host evolution to improve outcomes for persistently infected individuals and to better forecast potential trends in the emergence of new variants.

For these reasons, we sought to characterize SARS-CoV-2 persistence in an immunocompromised animal model. We focused on Syrian hamsters deficient in the interleukin-2 receptor gamma subunit (IL2rg)17. Wild-type hamsters are susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2 isolates and can develop disease signs and pathology resembling those observed in humans18. Originally generated to characterize persistent human adenovirus infection in immunocompromised hosts17, the IL2rg knockout (KO) hamster line lacks functional T-cell, B-cell, and natural killer cell responses, in a phenotype resembling human X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID). Here, we used IL2rg KO hamsters to better understand the pathophysiology of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection and the potential impact of tissue compartmentalization on within-host viral evolution.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 disseminates widely among tissues during infection of IL2rg KO hamsters

In wild-type Syrian hamsters infected with SARS-CoV-2, infectious virus can be recovered from the respiratory tissues for up to 11 days after infection19. To determine the extent of infection in IL2rg KO hamsters, animals (3–4-month-old males, n = 4) were intranasally inoculated with 104 plaque-forming units (pfu) of a SARS-CoV-2 isolate from the XBB.1.16 lineage.

On day 14 after infection, virus replicated efficiently in the lung and nasal turbinate tissues of all four animals with mean virus titers of around 106 pfu/g in both tissues (Fig. 1a; white bars). Efficient virus replication was also noted in the liver, jejunum, and ileum of all animals. We also detected infectious virus in the duodenum, heart, spleen, kidney, and serum of at least two animals and in the brain of one animal.

IL2rg KO hamsters (3–4-month-old, males, n = 4) were intranasally inoculated with a SARS-CoV-2 isolate from the XBB.1.16 lineage at a dose of 104 pfu in a total volume of 30 µl of inoculum while under anesthesia. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay with Vero E6 TMPRSS2-ACE2 cells. a Virus titers on days 14 and 100 after infection in the indicated tissue samples with titers at day 100 from hamsters #1, #2, and #4 only. Data were analyzed by using a two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test with * representing a P-value of 0.0160. There were no significant differences between virus titers in other tissues between time points. b Body weights of hamsters were monitored daily for 100 days. c Virus titers were determined using oral swab samples obtained from hamsters on the indicated days after infection. Data were analyzed by using a one-way ANOVA with no significant differences between time points. Dots (a, c) or lines (b) indicate data from individual hamsters. Vertical bars show the mean virus titer ± SD (a, c) with the lower limit of detection indicated by the horizontal dashed line (a). P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. NT nasal turbinate, NS not significant, ✝, hamster #3 succumbed on day 92 after infection. Source data are provided as a Supplementary data file.

Having established that virus replication remained robust at day 14 after infection, we next sought to establish a persistent infection. Animals (3–4-month-old males, n = 4) were intranasally inoculated with the XBB.1.16 variant (104 pfu) and monitored for 100 days. During this time, none of the hamsters demonstrated any outward signs of illness, including ruffled fur, hunched posture, or inactivity. Animals gained weight throughout the period; however, hamster #3 began to lose weight on day 66 after infection and succumbed to its infection on day 92 (Fig. 1b). To determine if a persistent infection was established during this period, we collected oral swab samples from the hamsters on days 39, 53, 64, 77, and 97 after infection. We detected infectious virus from available samples, with virus titers ranging from 102 to 104 pfu/ml with no significant differences (Fig. 1c).

At 100 days after infection, tissues were collected to determine virus titers. Virus replicated efficiently in the respiratory tissues (lung and nasal turbinate), but high titers were also detected in the intestinal tissues (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) (Fig. 1a; gray bars). Compared to the virus titers observed in the group of animals euthanized on day 14 after infection, titers in animals at day 100 were 10- to 100-fold higher in the liver, spleen, kidney, and serum, with infectious virus detected in the brain and heart of many animals. However, only brain tissue had significantly higher virus titers on day 100 compared with day 14. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 has also been detected in plasma in some human cases, indicating a shared feature of viremia13,20. Virus titers were also determined in these tissues of hamster #3, which succumbed on day 92. In this animal, infectious virus was detected in the lung, nasal turbinate, liver, and ileum (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Pathology in the tissues of persistently infected IL2rg KO hamsters at 100 days after infection

To examine the pathology and distribution of virus in fixed tissue samples at day 100 after infection, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) to detect viral nucleocapsid (N) protein and in situ hybridization with a probe specific for the N gene to detect viral RNA. In the lung tissues of persistently infected IL2rg KO hamsters, we detected viral antigen and RNA primarily in alveolar epithelial cells, with minor staining of viral antigen and RNA in the bronchiolar and bronchial epithelium (Fig. 2a). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed focal inflammation and immune cell infiltration at the viral detection site in the lung tissue of hamster #2, with Iba-1-positive macrophage infiltration (Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, there was no detectable inflammation or tissue injury, and few, if any, Iba-1-positive macrophages in the lung tissues of the other two hamsters (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2a).

a Lung, b ileum, and c liver tissues were collected 100 days after inoculation with the XBB.1.16 variant from hamsters #1, #2, and #4. Representative images of the tissues at high magnification are shown for immunohistochemistry (IHC) with a rabbit monoclonal antibody that detects SAS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid; in situ hybridization (ISH) targeting the nucleocapsid gene of SARS-CoV-2; immunohistochemistry with a rabbit polyclonal antibody that detects the macrophage marker Iba1; and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Scale bars, 100 µm.

In the ileum, we detected viral antigen and RNA in Iba1-positive macrophages in the tissues of all three hamsters, but there was no detectable inflammation or tissue injury (Fig. 2b). Viral antigen and RNA were also detected in Kupffer cells in the liver of all three hamsters (Fig. 2c), but the degree of liver pathology differed. Extensive inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis were present in hamster #1, compared to minimal, localized inflammation in hamster #4 (Fig. 2c). Notably, hamster #2 showed no evidence of hepatic inflammation or injury. In the kidneys, viral antigen and RNA were present in Iba1-positive macrophages and tubular epithelial cells, but no evidence of infection (viral protein by IHC or RNA by ISH) was detected in the heart (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c, respectively).

Collectively, viral persistence was observed consistently across all three hamsters at day 100 after infection, although distinct pathological manifestations were evident in different tissues of the individual animals.

Virus from a persistent infection maintains its replicative phenotype in wild-type hamsters

Because hamster #3 succumbed on day 92 after infection, we asked whether the virus from this animal gained an enhanced replicative phenotype. Wild-type Syrian hamsters (2–3-month-old, males, n = 4/group) were infected with 105 pfu of either the original XBB.1.16 isolate or virus obtained from the lung tissue of IL2rg KO hamster #3. Respiratory tissues were collected from four animals from each infection group on days 3 and 6 after infection, while the remaining four animals from each group were monitored for body weight loss over 14 days.

Infection with the original XBB.1.16 virus resulted in mean virus titers of 7.2 log10 and 6.6 log10 (pfu/g) in the lung and nasal turbinate tissues at day 3 after infection, respectively (Fig. 3a). Infection with the XBB.1.16 virus obtained from the lung tissue of hamster #3 resulted in mean titers of 7.3 log10 and 7.1 log10 (pfu/g) in these tissues, respectively (Fig. 3a). Measured titers were not significantly different across infection groups in either the lung (p-value = 0.305) or the nasal turbinate (p-value = 0.101).

Wild-type Syrian hamsters (2–3-month-old, males) were intranasally inoculated with virus at a dose of 105 pfu in a total volume of 30 µl while under anesthesia. a, b Virus titers were determined by plaque assay with Vero E6 TMPRSS2-ACE2 cells from hamsters (n = 4/time point/virus) at day 3 or 6 after infection. Vertical bars show the mean virus titer ± SD. Data were analyzed by using Welch’s t-test with no significant differences between the two viruses in any tissue or at any time point. Points indicate data from individual hamsters. The lower limit of detection is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. NT nasal turbinate, NS not significant. c Body weights of infected hamsters (n = 4/virus) were monitored daily for 14 days. Data are presented as the mean percentages of starting body weights ± SD with dots indicating individual hamsters. Data were analyzed by using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with no significant differences between viruses at any time point with P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Source data are provided as a Supplementary data file.

Infectious virus titers were reduced for both viruses on day 6 after infection compared to the earlier time point in both tissues (Fig. 3b). Both viruses replicated to similar titers in the lung and nasal turbinate tissues with no statistically significant differences (p-values = 0.438 and 0.528, respectively; Fig. 3b).

Hamsters infected with either virus had similar changes in weight over the 14-day period. There was minimal weight loss (2–3% of the original body weight) on days 3–4 after infection, after which all animals consistently gained weight by days 7–8 after infection (Fig. 3c). There were no significant differences in weight loss among animals infected with either virus on any day after infection.

Within-host viral genetic variation is largely consistent with genetic drift

We next sought to define patterns of SARS-CoV-2 evolution in these persistently infected hamsters. First, we performed deep sequencing in two technical replicates of the virus stock used to inoculate the animals. There was one consensus-level mutation in the virus inoculum relative to the original clinical isolate from which it was derived (EPI_ISL_17977756). This was an arginine-to-glycine substitution at Spike codon 682 (R682G; Wuhan-Hu-1 Spike amino acid numbering; 79.1% frequency). Minor viral populations encoded either the original arginine (R682) at a frequency of 18.0% or an arginine-to-tryptophan substitution (R682W) at 2.9%.

Next, we performed deep sequencing on viral RNA from all available hamster samples (Supplementary Table 1). Sequencing of the viral RNA from oral swabs was performed using ARTIC V5.3.2 primers on the Illumina MiSeq platform, whereas sequencing of tissue samples was performed with the QIAseq COVID Panel on the Novaseq 6000 platform. Intrahost single-nucleotide variants (iSNVs) were called using our previously characterized workflow, with a minimum frequency of 3% and a minimum read depth of 200×21,22.

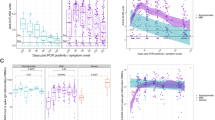

To characterize the evolutionary dynamics within individual hamsters, we first calculated the number of iSNVs detected in each oral swab sample relative to the consensus sequence of the virus inoculum. At a variant calling threshold of 3%, we detected high numbers of iSNVs in almost all oral swab samples (Fig. 4a). The number of iSNVs detected in these samples exceeded those present in the inoculum, indicating that de novo mutations in the hamsters likely contributed to the viral genetic diversity observed in the oral swab samples. The number of detected iSNVs varied throughout infection, although the viral titers remained high. Consistent with previous studies23,24,25, C→T transition mutations were substantially more common than other mutations in the oral swab samples, likely due to APOBEC (apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like)-mediated RNA editing24,25 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Slightly more than half of these C→T mutations were nonsynonymous, consistent with previous findings10.

a Number of iSNVs detected over time in oral swabs from each hamster compared to the virus inoculum. b Cumulative distribution of nonsynonymous and synonymous iSNV frequencies detected in oral swab samples shown for each hamster. The y-axis shows the proportion of iSNVs with frequencies that fall below the frequency values given on the x-axis. c The ratio of nonsynonymous (NS) to synonymous (S) iSNVs in each open reading frame compared to neutral expectation (gray bars, calculated from the ratio of potential nonsynonymous to synonymous sites). For the E (envelope) open reading frame in which we detected no synonymous substitutions, we set the NS/S value to 6. Black whiskers show the 95% confidence interval of the ratio. Overall, the entire SARS-CoV-2 genome; N nucleocapsid protein, M membrane protein.

Most iSNVs were detected at frequencies below 10% (Fig. 4b), consistent with patterns observed during acute human infections21. This was the case for both synonymous and nonsynonymous iSNVs. The distributions of synonymous and nonsynonymous iSNV frequencies were also remarkably similar to one another (Fig. 4b, the iSNV count summary for each hamster can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4), further indicating that purifying selection is not reducing frequencies of observed nonsynonymous iSNVs. Lower levels of nonsynonymous versus synonymous iSNV frequencies have been observed in some acute respiratory virus infections26,27 suggesting that purifying selection is a driver of within-host viral evolution in those infections. To further assess whether selection shaped intrahost viral populations in our hamsters, we calculated the ratio of the number of observed non-synonymous iSNVs to the number of observed synonymous iSNVs for each gene across all oral swab samples and then compared this ratio to the one expected under neutral evolution (i.e., in the absence of any kind of selection). These ratios showed high variability with broad 95% confidence intervals that typically encompassed the neutral expectation value (Fig. 4c; the total number of nonsynonymous and synonymous mutations for each open reading frame can be found in Supplementary Table 2; a complete list of the amino acid changes detected at a frequency of ≥3% in any animal is presented in Supplementary Data 2). Together, these findings indicate that SARS-CoV-2 evolution in these severely immunocompromised hamsters occurs largely through genetic drift: mutations are accumulating stochastically, without strong natural selection.

We further characterized viral evolutionary dynamics over time by analyzing the longitudinal trends observed in the oral swab samples (Fig. 5). For clarity, we show only mutations whose frequencies changed by a value of >0.1 between time points or appeared at a frequency ≥0.5 at any time point. We observed dramatic fluctuations in the frequencies of multiple iSNVs in each animal over time. Large fluctuations in iSNV frequencies are consistent with genetic drift playing a strong role in shaping intrahost viral evolution, particularly when iSNV frequencies fluctuate up and down, rather than changing frequency in a consistent, directional manner. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows several iSNVs that illustrate this dynamic pattern that is consistent with the process of genetic drift. Furthermore, and quite strikingly in hamsters #1 and #2, several iSNVs present at similar frequencies rose and fell together (Fig. 5). This pattern suggests strong genetic linkage among iSNVs and that recombination either does not occur extensively in vivo or that it is not detectable in our data.

This display is filtered on mutations that showed an absolute frequency change >0.1 between time points or appeared at a single time point with a frequency ≥0.5. Not all iSNVs were detected above threshold frequencies at each time point, so some traces are not contiguous from day 39 through day 97. Since hamster #3 succumbed to its infection on day 92, there are no data after day 77.

Finally, in hamster #2, we also observed a dramatic turnover in the virus population in the oral swab data. On day 39 after inoculation, the oral swab consensus sequence contained 68 mutations relative to the inoculum virus. By day 53, 31 of these mutations had reverted to the inoculum sequence, while 32 new majority-level iSNVs had appeared, many of which were present as minority variants on day 39. It is unlikely that these mutations were all acquired in a short time, so we speculate that at least two different viral lineages coexisted in this animal, and the second one became dominant for a time. Such lineage turnover has been observed in a persistently infected human10, where at least three lineages were detected. Many of the mutations present at majority levels in this animal on day 53 were also present at minority levels prior to that, suggesting that the other lineage was present earlier but subdominant.

Virus populations show greater similarity to individual host than by the tissue type

Multiple viral lineages could arise and coexist within the same animal due to tissue compartmentalization (i.e., spatial population structure). If mixing among tissue compartments is limited, virus populations in different tissues could diverge due to selection or genetic drift. Drift would lead to the random accumulation of changes across the genome, whereas tissue-specific selection pressures might result in the accumulation of similar mutations in a given tissue type across animals. To investigate this, we compared viral sequences among tissues and animals at the time of tissue collection along with oral swab comparisons when relevant. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity analysis, which accounts for both richness and evenness (i.e., both the number of mutations and their frequencies), revealed that viral sequences from hamster specimens were highly dissimilar to the inoculum, consistent with the accumulation of multiple de novo mutations after infection (Fig. 6a). Overall, samples tended to be more similar within animals than between animals; however, viruses sampled from lung at the time of necropsy were an exception to this trend (see hamsters #1 and #4, Fig. 6a). Bray-Curtis analysis also provides evidence for turnover in viral populations within animals during infection, seen most clearly in hamster #1 after day 39 and hamster #4 after day 64; this is consistent with the fluctuating patterns of iSNV frequencies seen in Fig. 5. As a complementary approach, we used the Jaccard index for hierarchical clustering to compare sequences from each sample based on the presence or absence of given iSNVs (Fig. 6b). This analysis revealed that viral samples from the same hamster often clustered together, consistent with lower levels of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between samples from the same hamster. Viruses from the lung tissue of 3 of the 4 animals formed a distinct cluster (Fig. 6b, orange labels). Another cluster was populated with intestinal samples, mostly from hamsters #2 and #4 (Fig. 6b, green labels), whereas oral swab samples from these animals nested in different clusters. Overall, these patterns suggest that multiple viral lineages may have been established in different tissues within hamsters shortly after inoculation, with lineages disappearing and reappearing in oral swab samples throughout the course of infection. The finding that many samples tend to cluster together by hamster rather than by tissue type is consistent with viral evolution occurring on separate trajectories within individual hamsters, with seeding of multiple viral lineages at the time of inoculation.

a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index comparing sequence data for each sample. b Hierarchical clustering dendrogram of viral populations from hamster samples. The dendrogram was constructed using the Jaccard index based on the presence/absence of iSNVs in each sample. The y-axis represents the Jaccard dissimilarity measure, ranging from 0 (identical sets of mutations present in both samples) to 1 (completely different sets of mutations in each sample). Sequences are colored by sample type: GI tissues, lung tissue, oral swab, or virus inoculum.

Discussion

Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised people remains a pressing problem for individual and public health. Immunocompromised individuals continue to have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality following SARS-CoV-2 infection, with limited evidence-based options for managing infection in these patients. Moreover, persistent viral replication in the presence of weakened immune responses is thought to be a major driver of the emergence of highly divergent immune escape variants that can cause waves of infection in the broader population. Thus, there is a need to improve our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and evolution in persistent infections, to address the potential role of tissue reservoirs in viral persistence and evolution, and to evaluate candidate therapies to eradicate persistent infection. These efforts have been hampered by the lack of a small animal model to study persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Our study establishes IL2rg KO Syrian hamsters as a tractable model system to study SARS-CoV-2 persistence without the need to suppress the immune response with repeated administrations of a drug such as cyclosporine. A previous study using IL2rg KO hamsters demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection could persist for up to 24 days19. Here, we show that SARS-CoV-2 disseminated extensively throughout the tissues of IL2rg KO animals within 14 days of inoculation, and persistent high-titer virus replication occurred in organs and tissues through day 100. On day 14, we detected viral titers of approximately 106 pfu/g in lung and nasal turbinate tissues, comparable to the high viral loads detected in the upper respiratory tract of humans during acute infection28. Three of four animals continued to maintain or even gain weight through day 100 after infection, suggesting that IL2rg KO hamsters could support SARS-CoV-2 infections of even longer duration. Despite stable or increased body weight, the hamsters still shed infectious virus and oral swabs remained virus-isolation–positive up to day 97 after infection, consistent with reports of infectious virus shedding in humans from swabs or saliva collected 14–70 days after initial infection29,30,31. Importantly, we detected infectious virus in serum at both days 14 and 100, in line with studies that have detected vRNA or infectious virus in human serum or plasma32,33. The presence of infectious virus in serum or plasma suggests that infection can spread between anatomical sites through the bloodstream.

Similar to our IL2rg KO hamster model, persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans has been linked to early disseminated infection. In an autopsy study of 44 COVID-19 cases, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 84 distinct anatomical sites and body fluids. In several of these cases, the virus disseminated early, with replication occurring in multiple non-respiratory tissues during the first two weeks of infection13. Notably, subgenomic RNA was identified in at least one tissue in 14 of 27 cases beyond day 14, indicating ongoing replication in non-respiratory sites for weeks to months. Among “late” cases (≥31 days after infection), viral RNA was found in the central nervous system in 5 of 6 cases, with persistence across multiple other tissue groups. Infectious virus was isolated from diverse tissues (e.g., brain, heart, lymph node, gastrointestinal tract, adrenal gland, and eye), consistent with our findings in IL2rg KO hamsters and with reports of virus isolation from non-respiratory tissues in human cases34,35. The heterogeneous outcomes observed in humans with persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection suggest that persistence is stochastic and idiosyncratic, with disease manifestations and evolutionary trajectories likely determined by which tissues are seeded early, and which can sustain long-term viral replication. Despite their identical genetic background and comparable immune defects, IL2rg KO hamsters exhibited variable clinical outcomes, underscoring the need for further characterization of this model to delineate the determinants of tissue-specific viral persistence and disease heterogeneity.

Our histopathological analysis revealed that complex disease processes occurred in persistently infected IL2rg KO hamsters. In the lung tissues, we detected viral antigen and RNA primarily in the alveolar epithelial cells, with some presence in the bronchiolar and bronchial epithelium. Interestingly, while focal inflammation and immune cell infiltration were observed in the lung tissue of hamster #2, no detectable inflammation or tissue injury was evident in the lungs of the other two animals.

In humans, SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause hepatic necrosis and infection of Kupffer cells36. It is therefore interesting to note that liver pathology varied among the animals in our study. Hamster #1 exhibited extensive inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis. In contrast, hamster #4 showed sporadic focal inflammation of mainly macrophages based on Iba1 marker staining, and hamster #2 displayed no notable tissue injury. These differences imply that differential host immune responses are still functional in IL2rg KO hamsters, such as interferon responses to SARS-CoV-2 persistence in different tissues, further underscoring the complexity of chronic infection dynamics.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA is abundantly detectable in wastewater, and human gastrointestinal (GI) enterocytes can support viral replication. However, the role of GI tissues in SARS-CoV-2 infection, transmission, pathogenesis, and evolution remains unclear. On day 100, we detected infectious virus in three different anatomic areas of the small intestine at titers only 10-fold lower than those in respiratory tract tissues. Interestingly, despite efficient virus replication in the intestinal tract, no tissue damage was observed in the ileum. In future studies, a more detailed assessment of histopathology in both the small and large intestinal tissues is warranted, along with a more detailed analysis of infectious virus recovery and viral genome sequences from feces during the course of infection.

Persistent replication allows large viral population sizes to persist without the frequent population bottlenecks that occur in chains of acute transmission21. In immunocompromised humans, SARS-CoV-2 can replicate in the presence of weak but consistent selective pressure from adaptive immune responses. Notably, B-cell deficiencies may confer the greatest risk of SARS-CoV-2 persistence5,6. This selective environment may particularly favor the emergence of mutations that enhance antibody escape, alter receptor-binding affinity, or modulate fusogenicity11. In contrast, the IL2rg KO hamster model provides a setting that functionally lacks selective pressure from adaptive immunity. Consistent with this, we found that SARS-CoV-2 evolution in severely immunocompromised hamsters occurs primarily through genetic drift, as evidenced by NS/S ratios comparable to neutral evolution models and similar patterns in the cumulative distribution of nonsynonymous and synonymous mutation frequencies. We also found that iSNV frequencies oscillated dramatically over time in most animals, underscoring that genetic drift has strong effects on allele frequencies even in the absence of strong detectable natural selection. The observation that frequencies of multiple iSNVs rose and fell together in multiple animals suggests that within-host recombination is limited, or difficult to detect, in these animals. This finding also suggests that multiple genetic lineages of viruses coexist within infected hamsters, with different lineages predominating at different times in oral swab samples. Such a situation has been observed in a prolonged human infection, in which at least three distinct viral lineages were defined10.

Interestingly, we noted an excess of non-synonymous mutations compared to synonymous mutations in certain genes, particularly in the envelope gene. A similar pattern was noted in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 persistent infection10. This finding may suggest that genes other than Spike may be under selective pressure during prolonged infection, although most reports of persistent infection in humans have focused on the accumulation of amino acid substitutions in Spike.

Viral replication in different anatomical compartments with incomplete mixing could play a role in the development of distinct coexisting lineages. We cannot know when infection was established in different tissue sites in the persistently infected animals, but the observation of high titers of infectious virus in most sampled tissues by day 14 after inoculation suggests that populations of replicating viruses could be established at various tissue sites very early in infection. Bray-Curtis analysis and Jaccard hierarchical clustering revealed that viral sequences from lung tissues tended to be distinct from viruses found in oral swab samples in the same animal, while in some cases, sequences from intestinal tissues of different animals clustered more closely with each other than with sequences from other sample types within the same animal. No sequences sampled from persistently infected hamsters closely resembled the inoculum. Together, these observations show that SARS-CoV-2 accumulated multiple de novo mutations over the course of persistent infection in these animals. As expected, we did not observe evidence of selection for phenotypes like immune escape. The fluctuations in iSNV frequencies over time in oral swab samples and our similarity analyses including oral swabs and tissues sampled at necropsy suggest that viral evolution proceeded along different trajectories in each animal. In addition, multiple lineages were likely established within each hamster early during infection, potentially across the respiratory tract (including the lung and oral cavity).

The possibility that different tissues can allow for viral compartmentalization and persistence of viral lineages through repeated cross-tissue seeding in persistently infected hosts has important implications. For example, replication in specific tissues could be important for the evolution and emergence of new variants of concern. Tissue reservoirs could also be important for the establishment and maintenance of SARS-CoV-2 persistence itself15. Treatment options for persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections in immunocompromised individuals remain limited, and viral persistence at tissue sites might provide reservoirs from which systemic infection could be re-established after treatment is discontinued4. The hamster model we established here may be especially useful in evaluating treatments for SARS-CoV-2 persistence.

From this study, we identified noteworthy amino acid changes in the viral genomes. A substitution in the viral envelope protein (i.e., E:T30I) was detected in multiple hamsters in both oral swabs and tissue samples at the consensus level (Supplementary Data 2). Previous studies have suggested that this substitution may be a marker of long-term SARS-CoV-2 infection: it is among the most frequently detected changes in immunocompromised patients, arising independently in persistent infections with a variety of viral lineages, but it is otherwise rare in the global phylogeny37. Consensus-level amino acid changes were detected immediately upstream (S:G687W/R) or downstream (S:S687P in hamster #1) of the furin-cleavage site in Spike, which could affect the efficiency of cleavage, but we cannot determine from our data whether these changes confer a fitness advantage to these particular viruses38,39.

Our study has important limitations. IL2rg KO hamsters were initially designed to model human X-linked SCID16. These hamsters are profoundly immunocompromised, lacking functional B cells and T cells, and mature NK cells. X-linked SCID is rare in humans, and most reports of SARS-CoV-2 persistence in humans have involved patients with some residual immune function. Indeed, two clinical studies have suggested that B-cell deficiencies may carry the greatest risk of SARS-CoV-2 persistence5,17. Patients whose B-cell activity is weak but still present may provide the ideal environment for the within-host selection of antibody-escape mutants, while we would expect there to be no selective pressure from adaptive immunity in IL2rg KO hamsters. Because of the immunocompromised status of these transgenic hamsters, we provided cage bedding that was sterile, but we were unable to provide a completely sterile environment for the animals. It is possible that the animals have had a secondary infection with a different pathogen. However, we did not investigate whether these IL2rg KO hamsters had other infections, which limits our knowledge of how other infections could alter the outcome of the persistent infection with SARS-CoV-2. In addition, due to limited sample availability, we were unable to sequence samples in technical replicates. This limitation reduces the precision with which we can estimate iSNV frequencies, especially near the 3% threshold, and may increase the likelihood that we failed to exclude spurious low-frequency iSNVs arising due to method error. However, our previous work, as well as work by Grubaugh et al.22, showed highly accurate iSNV calls with tiled amplicon sequencing using a 3% frequency threshold, suggesting that our 3% minimum frequency for calling true iSNVs effectively excludes false positives21. We also found a near-linear correlation between iSNV frequencies measured above 3% in technical replicates, suggesting that the reduced precision available to us in this study is unlikely to dramatically affect our ability to make inferences about the strength and direction of natural selection.

Collectively, this study demonstrates that IL2rg KO hamsters are a useful model for persistent SARS-CoV-2 infections, which could provide insights into the development of antiviral treatment strategies aimed at eliminating viral tissue reservoirs and minimizing the risk of drug resistance. By applying selective pressure through antibody treatment or antiviral drugs in this model, it will be possible to model within-host evolutionary processes that could lead to the emergence of novel antigenic or drug-resistant variants.

Methods

Biosafety and animal protocols

All experiments involving SARS-CoV-2 virus were performed under biosafety level 3 agriculture containment with an institutionally approved biosafety protocol (B00000263). Hamster studies were performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin, Madison (protocol number V006426), and we have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Cells and viruses

A SARS-CoV-2 isolate (hCoV-19/USA/IRI97754/2023 [EPI_ISL_17977756]) from the XBB.1.16 lineage was isolated from a de-identified nasopharyngeal swab and propagated on Vero TMPRSS2 cells (JCRB 1819). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 1 mg/ml geneticin (G418; Invivogen). Vero E6 TMPRSS2-ACE2 cells used for virus titration were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 10 μg/mL puromycin (Invivogen). Both cell lines were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and were determined to be mycoplasma-free by regular PCR testing.

Experimental infection and sample collection of hamsters

Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) were housed in single cages and provided with food and water ad libitum along with sterile bedding and enrichment. The room housing the animals had controlled temperature and humidity with 12-h light and dark cycles. Animals were allowed to acclimate for 5 days prior to the study and monitored at least once daily by trained personnel for any signs of severe infection, a humane endpoint.

To establish a persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection, IL2rg KO hamsters17 (3-4-month-old, males) were intranasally inoculated with 104 pfu of an XBB.1.16 variant in a total volume of 30 µl of inoculum while anesthetized with isoflurane. To evaluate virus pathogenicity in wild-type Syrian hamsters, animals (2–3-month-old, males, Envigo) were intranasally inoculated with 105 pfu of virus in a total volume of 30 µl while anesthetized with isoflurane. When body weights and oral swabs were taken, the animals were not anesthetized. For tissue collection, animals were humanely euthanized by isoflurane overdose.

Histopathology

Tissues from hamsters were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding with 3-µm-thick sections generated that were mounted on sets of silane-coated glass sides. One set of tissue slides was treated with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain for histopathological examination. Another set of tissue slides was used for viral RNA detection by in situ hybridization using an RNA scope 2.5 HD Red Detection kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) with an antisense probe targeting the nucleocapsid gene of SARS-CoV-2. Tissue sections were also processed for IHC with a rabbit monoclonal antibody against the viral nucleocapsid protein (Sino Biological; 40143-R001, 1:1000 dilution) along with an antibody against the macrophage marker Iba1 (GenTex; GTX100042, 1:1000 dilution). Specific antigen-antibody reactions were visualized by means of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride staining (Dako Envision system; K4001, 1:1 dilution).

SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing

Viral RNA from virus stock and oral swab samples was extracted using the Viral RNA Kit (Qiagen). For tissue samples, clarified homogenates in Trizol were used to extract viral RNA using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The QIAseq DIRECT SARS-CoV-2 Kit (Qiagen) was used to sequence viral RNA from all hamster tissue samples. Generated libraries were deep sequenced using 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads on Illumina Novaseq at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Biotechnology Center, generating at least 2 million paired-end reads for each sample. Before analyzing the results, we confirmed that fewer than 10 SARS-CoV-2 reads were generated in negative controls.

Viral RNA from nasal swab samples was processed separately for sequencing using the COVIDSeq assay kit (Illumina) with the ARTIC V5.3.2 primer scheme for RT-PCR and library preparation. The generated libraries were deep sequenced using 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads on Illumina Miseq at the UW-Madison Influenza Research Institute.

Processing raw Illumina data

The sequencing data were processed with the nf-core viral-recon pipeline v2.6.0 (https://nf-co.re/viralrecon/2.6.0/), using a modified config file (“-t 0.01 -q 30 -m 200”) to include low-frequency variants in the variant calling process, where -t 0.01 sets a minimum allele frequency threshold of 1%, -q 30 enforces a base quality filter of Q30 to ensure high-confidence variant calling, and -m 200 requires a minimum coverage depth of 200 reads to reduce errors from low read support and (“-t 0.5 -q 20 -m 10 -n N”) to ensure iSNVs above 50% are included in the consensus sequence. We first generated a consensus sequence for the XBB.1.16 inoculum by mapping reads from the inoculum sample to the Wuhan-1 reference. To define consensus sequences and call iSNVs for each biological specimen from hamsters, we mapped reads from specimens to the XBB.1.16 inoculum sequence using the modified primer file and gtf for correctly primer trimming and annotation.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism software was used to analyze the virus titer data from the lung and nasal turbinate tissues along with weights of the hamsters; no data were excluded. In Fig. 1a, data (n = 4 hamsters/time point) were analyzed by using a two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. In Fig. 1c, data (n = 4 hamsters) were analyzed by using a two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. In Fig. 3a, b, data (n = 4 hamsters/virus/time point) were analyzed by using Welch’s t-test with no significant differences between the two viruses in any tissue or at any time point. In Fig. 3c, data (n = 4 hamsters/virus) are presented as the mean percentages of starting body weights ± SD and were analyzed by using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Relative mutation rate calculation

We classified sequences based on sample type, distinguishing between oral swabs and tissue samples (lung, duodenum, ileum, and jejunum) in Supplementary Fig. 3. For our analysis, we included only iSNVs that appeared with a frequency >3%. Mutations observed in these iSNVs were categorized according to their nucleotide change (e.g., C→T) and type (non-synonymous, synonymous, or intergenic). To calculate relative mutation rates, we first grouped the data by animal ID, mutation type, and nucleotide substitution classification. For each animal, relative mutation rates were calculated by dividing the count of each specific mutation by the total number of mutations observed in that animal. The distribution of these normalized mutation rates was then visualized using boxplots.

Dissimilarity indexes

We used the Bray–Curtis index for whole-genome pairwise comparisons, where species were represented by unique variants in the genome. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity indexes were calculated using the vegan package (version 2.6-4) in R.

We used the Jaccard index for hierarchical clustering. Jaccard dissimilarities were computed based on the presence or absence of iSNVs in each sample using the pdist function from the SciPy spatial distance package. The resulting distance matrix was then used to perform hierarchical clustering via the linkage function from the SciPy cluster hierarchy package. Figure 6b presents results obtained using the average-linkage clustering method, which merges clusters based on the mean pairwise dissimilarities.

Figures and plots

Figures were generated using RStudio version 2024.12.0 + 467 and Python, utilizing the ggplot2 package, or GraphPad Prism. Final esthetic modifications were made using Adobe Illustrator 2025 or PowerPoint.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the sequences associated with this project have been deposited to NCBI BioProject PRJNA1382858. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2. All other data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Cevik, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2, e13–e22 (2021).

Killingley, B. et al. Safety, tolerability and viral kinetics during SARS-CoV-2 human challenge in young adults. Nat. Med. 28, 1031–1041 (2022).

Ghafari, M. et al. High number of SARS-CoV-2 persistent infections uncovered through genetic analysis of samples from a large community-based surveillance study. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.29.23285160 (2023).

Machkovech, H. M. et al. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection: significance and implications. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e453–e462 (2024).

Raglow, Z. et al. SARS-CoV-2 shedding and evolution in patients who were immunocompromised during the omicron period: a multicentre, prospective analysis. Lancet Microbe 5, e235–e246 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral clearance and evolution varies by type and severity of immunodeficiency. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadk1599 (2024).

Markov, P. V. et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 361–379 (2023).

Corey, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants in patients with immunosuppression. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2104756 (2021).

Halfmann, P. J. et al. Evolution of a globally unique SARS-CoV-2 Spike E484T monoclonal antibody escape mutation in a persistently infected, immunocompromised individual. Virus Evol. 9, veac104 (2022).

Chaguza, C. et al. Accelerated SARS-CoV-2 intrahost evolution leading to distinct genotypes during chronic infection. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100943 (2023).

Cele, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 prolonged infection during advanced HIV disease evolves extensive immune escape. Cell Host Microbe 30, 154–162.e5 (2022).

Farjo, M. et al. Within-host evolutionary dynamics and tissue compartmentalization during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Virol. 98, e0161823 (2024).

Stein, S. R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature 612, 758–763 (2022).

Van Cleemput, J. et al. Organ-specific genome diversity of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–11 (2021).

Proal, A. D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat. Immunol. 24, 1616–1627 (2023).

El Moussaoui, M. et al. Intrahost evolution leading to distinct lineages in the upper and lower respiratory tracts during SARS-CoV-2 prolonged infection. Virus Evol. 10, veae073 (2024).

Li, R. et al. Generation and characterization of an Il2rg knockout Syrian hamster model for XSCID and HAdV-C6 infection in immunocompromised patients. Dis. Models Mech. 13, dmm044602 (2020).

Imai, M. et al. Syrian hamsters as a small animal model for SARS-CoV-2 infection and countermeasure development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 117, 16587–16595 (2020).

Rosenke, K. et al. Defining the Syrian hamster as a highly susceptible preclinical model for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 2673–2684 (2020).

Giacomelli, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viremia and COVID-19 mortality: a prospective observational study. PLoS ONE 18, e0281052 (2023).

Braun, K. M. et al. Acute SARS-CoV-2 infections harbor limited within-host diversity and transmit via tight transmission bottlenecks. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009849 (2021).

Grubaugh, N. D. et al. An amplicon-based sequencing framework for accurately measuring intrahost virus diversity using PrimalSeq and iVar. Genome Biol. 20, 8 (2019).

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Patterns of within-host genetic diversity in SARS-CoV-2. Elife 10, e66857 (2021).

Popa, A. et al. Genomic epidemiology of superspreading events in Austria reveals mutational dynamics and transmission properties of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabe2555 (2020).

Simmonds, P. Rampant C→U Hypermutation in the genomes of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses: causes and consequences for their short- and long-term evolutionary trajectories. mSphere 5, e00408-20 (2020).

McCrone, J. T. et al. Stochastic processes constrain the within and between host evolution of influenza virus. Elife 7, e35962 (2018).

VanInsberghe, D. et al. Genetic drift and purifying selection shape within-host influenza A virus populations during natural swine infections. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012131 (2024).

Puhach, O., Meyer, B. & Eckerle, I. SARS-CoV-2 viral load and shedding kinetics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 147–161 (2023).

Avanzato, V. A. et al. Case study: Prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell 183, 1901–1912.e9 (2020).

Choi, B. et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2291–2293 (2020).

Alshukairi, A. N. et al. Re-infection with a different SARS-CoV-2 clade and prolonged viral shedding in a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patient. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 110, 267–271 (2021).

Jacobs, J. L. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 viremia is associated with Coronavirus disease 2019 severity and predicts clinical outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 74, 1525–1533 (2022).

Platt, A. et al. Replication-Competent Virus Detected in Blood of a Fatal COVID-19 Case. Ann. Int. Med. https://doi.org/10.7326/L23-0253 (2023).

Puelles, V. G. et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 590–592 (2020).

Yao, X.-H. et al. A cohort autopsy study defines COVID-19 systemic pathogenesis. Cell Res. 31, 836–846 (2021).

Zanon, M. et al. Liver pathology in COVID-19 related death and leading role of autopsy in the pandemic. World J. Gastroenterol. 29, 200–220 (2023).

Wilkinson, S. A. J. et al. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 mutations in immunodeficient patients. Virus Evol. 8, veac050 (2022).

Gupta, K. et al. Structural basis for cell-type specific evolution of viral fitness by SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 12, 222 (2022).

Lubinski, B. et al. Spike protein cleavage-activation in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 P681R mutation: an analysis from its first appearance in lineage A.23.1 identified in Uganda. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0151422 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21AI164001 to Y.K., the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant numbers JP24wm0125008, JP24fk0108637, JP25fk0108732, JP223fa627003, and JP243fa727002 to T.S. Funding was also through the University of Wisconsin–Madison to T.C.F. and P.J.H. and from Utah State University to Z.W. We thank Yuko Sato and Seiya Ozono for their technical assistance. We also thank Chase Nelson for his insight into virus evolution analysis and Sue Watson for editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.K., T.C.F., Y.K., and P.J.H. Methodology and data analysis: W.W., T.C.F., M.K., S.I., S.K., Y.H., and P.J.H. Investigation: W.W., M.K., S.I., S.K., Y.L., Y.H., and P.J.H. Visualization: W.W., M.K., S.I., Y.H., K.K., T.C.F., and P.J.H. Writing—original draft: W.W., H.M., K.K., T.C.F., and P.J.H. Writing—review and editing: W.W., M.K., S.I., S.K., Y.L., H.M., Y.H., T.S., Z.W., K.K., T.C.F., Y.K., and P.J.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.K. has received unrelated funding support from Daiichi Sankyo Pharmaceutical, Toyama Chemical, Tauns Laboratories, Inc., Shionogi & Co. Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, KM Biologics, Kyoritsu Seiyaku, Shinya Corporation, and Fuji Rebio. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Connor Bamford and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Harry Taylor and Johannes Stortz.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, W., Kuroda, M., Liu, Y. et al. Pathology and viral evolutionary dynamics in a hamster model of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection. Commun Biol 9, 193 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09473-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09473-y