Abstract

Chemotaxis is an adaptive mechanism that shapes the behavior of motile bacteria in habitats characterized by fluctuating and often conflicting cues environmental (e.g. stay-or-go). Chemotactic responses are orchestrated by phosphorylation of CheY, which triggers rotational switching of the flagella. In Escherichia coli and similar taxa, CheZ is the principal CheY-P phosphatase, whereas in lineages lacking CheZ, members of the structurally distinct CheC-FliY-CheX family fulfill this role. Intriguingly, some bacteria code for CheX and CheZ, presenting a conundrum regarding their function, and the role of CheX in CheZ-containing organisms is unknown. We imposed a sustained motility constraint under conditions of looming nutrient depletion in Vibrio vulnificus, which possesses both CheX and CheZ, using the c-di-GMP effector PlzD that robustly curtails swimming motility. Our analyses revealed that the activity of CheX, but not CheZ, could be attenuated to mitigate the imposed constraint, assigning CheX a pivotal function in fine-tuning foraging behavior during a “stay-or-go” decision. V. vulnificus CheX maintained CheY-P phosphatase activity despite its conserved dimeric fold structure exhibiting divergence in active-site architecture, suggesting a preserved catalytic mechanism among distantly related homologs. Co-conservation of cheX and cheZ across disparate bacterial phyla suggests their adaptative retention confers robustness and versatility to chemotactic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial chemotaxis is a fundamental physiological response that enable motile bacteria to navigate their environment by detecting and responding to gradients of attractants and repellents1,2,3. This process transforms random motility into directed migration, thereby enhancing bacterial survival and ecological fitness4. The chemotaxis pathway consists of several highly conserved components. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) are transmembrane receptors that detect specific environmental attractants or repellents. MCPs assemble into large, cooperative hexagonal arrays at the cell poles5, amplifying sensitivity to minute changes in ligand concentration6. CheA is a cytoplasmic kinase that associates with MCPs and the coupling protein CheW, which facilitates signal transmission from the receptor to the kinase. Attractant binding to the MCPs inhibits CheA autophosphorylation, thereby reducing phosphoryl transfer to the response regulator CheY. The resulting decrease in phosphorylated CheY (CheY-P) lowers its interaction with the flagellar motor, biasing rotation toward the counterclockwise state that drives smooth, forward swimming. Conversely, repellent binding stimulates CheA autophosphorylation, increasing CheY phosphorylation and enhancing clockwise rotation of the flagellar motor, which induces more frequent reorientations that facilitate avoidance of unfavorable stimuli. The methyltransferase CheR and methylesterase CheB dynamically methylate and demethylate MCPs, respectively, enabling the cell to adapt to persistent stimuli and maintain sensitivity over a wide range of concentrations. This feedback ensures robust chemotactic behavior even in fluctuating gradients. In the absence of a gradient, bacteria alternate between straight swimming (runs) and directional reorientations (e.g. tumbling in Escherichia coli7 and reversal/flicks in Vibrio species8,9), resulting in random movement. In a gradient, the chemotaxis pathway biases this movement such that the cell moves toward an attractant and away from a repellent.

The rapid dephosphorylation of CheY-P terminates the signal that instigates directional changes. This allows for a rapid response to changes in the environment by restoring CheY to its unphosphorylated state, which biases flagellar rotation back towards runs. CheZ, the best characterized of the CheY-P phosphatases, bears conserved residues (Asp143 and Gln147) that interact with the CheY phosphorylation site and increases CheY-P auto-dephosphorylation by positioning a water molecule for in-line attack of the phosphorus10. While CheZ is the primary CheY-P phosphatase in E. coli10,11,12, many other bacteria lack CheZ and utilize the CheC-FliY-CheX family of phosphatases in various combinations to achieve similar regulatory outcomes (e.g. Bacillus subtilis has only CheC and FliY, while Bacillus halodurans, has CheX in addition to CheC and FliY)13,14,15,16,17,18. CheX has been shown to be a stronger CheY-P phosphatase than either CheC or FliY13 and CheX and CheZ are generally not found concurrently in bacterial genomes. Hence, the presence of both in some lineages is perplexing and a role for CheX in cells that also harbor CheZ has not been reported.

c-di-GMP is a key second messenger in bacterial signal transduction19,20,21, orchestrating, among many behaviors, the transition between motile and sessile lifestyles22,23,24. The intracellular levels of c-di-GMP are tightly controlled by the opposing activities of diguanylate cyclases (DGCs), which synthesize c-di-GMP from GTP, and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that degrade it. Effector proteins are essential components of c-di-GMP signaling pathways, acting as mediators that bind to c-di-GMP and initiate specific cellular responses. High levels of c-di-GMP typically reduce motility and promote biofilm formation, while low levels favor a more motile and virulent state.

Among its diverse repertoire of effectors, homologs of YcgR have emerged as principal mediators of c-di-GMP-dependent inhibition of swimming motility in E. coli and related enterobacteria25,26,27,28. Upon binding c-di-GMP via its PilZ domain29,30,31,32, YcgR undergoes a conformational change27,33,34 and interacts with components of the flagellar motor to modulate its output in two distinct ways: it biases the flagellar motor toward counterclockwise (CCW) rotation, thereby diminishing the frequency of directional changes required for effective chemotaxis while concurrently attenuating the overall torque and rotational speed of the flagellum, resulting in a pronounced decrease in swimming velocity25,35,36. Hence, YcgR and related c-di-GMP effectors exercise adaptive control of flagellar motility in response to environmental stimuli, dynamically balancing motile and sessile lifestyles to optimize bacterial fitness and survival.

Bacteria inhabit environments characterized by fluctuating and often conflicting cues. The challenge they face is not merely to respond, but to interpret sometimes opposing signals (e.g. stay-or-go) to enact behaviors that optimize survival (e.g. surface colonization vs. foraging). Although the mechanisms by which extracellular cues and intracellular signaling pathways regulate chemotaxis and motility inhibition are well characterized, dynamic interplay between these distinct networks is less well understood. Here, we impose a motility constraint in V. vulnificus, a species that codes for both CheX and CheZ37, by expressing its YcgR homolog, PlzD28,33. Analysis of suppressor mutants revealed a strategy whereby tempered CheX, but not CheZ, activity relieved effector-imposed motility constraints by increasing the flagellar switch frequency and range expansion of swimming cells, ascribing a role for CheX in fine-tuning foraging under constraint.

Results

Suppressor mutations of effector-imposed motility constraints map to cheX, a component of the chemotaxis pathway

To avoid the pleiotropic effects of elevated cellular c-di-GMP levels on bacterial physiology, we elected to constitutively express PlzD, which inhibited motility of V. vulnificus through soft agar nearly 5-fold (Fig. 1A). Extended incubation times yielded isolates that suppressed this phenotype. To distinguish between chromosome-encoded mutations that suppressed plzD-mediated motility inhibition and plasmid-encoded mutations that disrupted plzD expression, plasmids were recovered from each suppressor mutant and separately re-introduced into wild type V. vulnificus cells. Inhibition of swimming by these cells under inducing conditions indicated that the recovered plasmid functioned normally and that the mutant from which it came bore a chromosome-encoded mutation, whereas levels of swimming comparable to control cells (wildtype cells carrying the empty expression vector) suggested a plasmid-encoded mutation (Fig. S1B). Whole genome sequencing (WGS) revealed that several suppressor mutants harbored missense mutations that mapped to aot11_15760, which codes for a homolog of CheX (see Table S1 for details). The changes resulted in CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L67P variants in two of these mutants. Swimming assays through soft agar showed that plzD expression failed to inhibit motility of the mutants, whereas its co-expression with genes coding for wildtype CheX, but not the CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L67P variants, inhibited motility of the parent suppressor (an example for CheXL65R is shown in Fig. 1B). These results suggested that mutations in cheX could relieve the motility defect resulting from constitutive plzD expression. Fluorescence imaging of ∆plzD cells producing PlzD-GFP and ∆cheX cells producing CheX-RFP fusions revealed a polar signal for PlzD but a cytoplasmic distribution for CheX (Fig. 1C) and attempts to detect an interaction between PlzD and CheX by co-immunoprecipitation and BACTH were unsuccessful, suggesting that the functional relationship between them was not dependent on a direct physical interaction.

A Colony spread through soft agar of wildtype control cells carrying the empty vector (WT) or expressing plzD (WT + plzD). A plot of the corresponding motility zones showing the respective mean values for each strain is on the right. B Colony spread in soft agar under inducing conditions of wild type cells (WT) and a cheX suppressor mutant (Sup) carrying the IPTG-inducible plzD expression plasmid (+pplzD) alone or together with an arabinose-inducible plasmid expressing wild type cheX (pcheX) or the L65R variant (pcheXL65R). To the right is a bar plot of the corresponding motility zones for each strain. C Representative phase and fluorescence images (×100 magnification) of V. vulnificus ∆plzD (top row) and ∆cheX (bottom row) cells expressing plzDgfp and cheXrfp, respectively. Scale bar, 1 µm. D Western blot of V. vulnificus ∆cheX cells expressing HA-tagged CheX or the CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L65P variants from an arabinose-inducible expression plasmid (pcheX). Control cells (−) carry the empty expression plasmid. E Colony spread in soft agar by WT and ∆cheX cells expressing plzD from an IPTG-inducible expression plasmid (+pplzD). F Bar plot of the motility zones for ∆cheX+pplzD cells that also carry pcheX in media containing IPTG and varying amounts of L-ara. G Motility zones for wild type cells carrying the empty expression vector (+vec) and wild type, ∆cheZ and ∆cheX cells expressing plzD (+pplzD) and, where indicated, cheX (+pcheX). Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate assays. Statistically significant differences between the strains in A were determined by an unpaired Student’s test, two-tailed (p < 0.0001). Statistically significant differences from wild type were determined by one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test in (B, F, G). p values: ***, <0.001; ****, <0.0001; ns no significant difference.

Decreasing cellular CheX levels relieve effector-mediated inhibition of motility

Mutations that mapped to flagellar rotation and c-di-GMP degradation pathways were identified in two additional suppressor mutants. Missense mutations in aot11_10690 (motA) and aot11_19910 (a putative PDE) generated MotAK173Q and AOT_19910A107T variants. However, co-expression of plzD with wild type motA or wild type aot11_19910 did not restore inhibition of swimming motility in the respective suppressor backgrounds (Fig. S1C), suggesting that the motility phenotype of these mutants was due to something other than mutation of MotA or AOT_19910. WGS of both suppressor mutants revealed the insertion of a novel insertion sequence (IS) element 15 and 37 bp into cheX in the motA and aot11_19910 suppressors, respectively (Fig. S1D). The IS element, present at different locations on chromosome 1 and 2 in the parental strain (Fig. S1E), was 1307 bp in length and direct repeats of 9 bp (5-TAAAAAA-3’) and an 11 bp inverted repeat (5’-GTTCATCGCGG-3’) were identified at its boundaries. The transposase was a member of the IS1001 family and included a N-terminal 50 amino acid helix-turn-helix domain and a C-terminal 240 residue DDE domain. The insertion of an IS element within the first few nucleotides of cheX suggested that disruption of cheX expression, rather than mutations in motA or aot11_19910, was responsible for the phenotypes of these suppressor mutants. Accordingly, co-expression of plzD with wild type cheX restored inhibition of motility in the respective suppressor backgrounds (Fig. S1C), suggesting that the loss of CheX, rather than a physical interaction with PlzD, was responsible for restoring motility. This was confirmed when the genes for wild type CheX and the CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L67P variants were expressed in the ∆cheX background as N-terminal HA-fusions for detection by western blotting. While CheX was stably produced, CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L67P were not (Fig. 1D). Indeed, the signal for CheXL65R was 15-fold lower than wild type CheX, while the signal for CheXL65R/L67P was 50-fold lower than wildtype. Since inhibition of swimming motility by wild type cells expressing plzD was relieved by deletion of cheX (Fig. 1E) and the motility of ∆cheX cells expressing plzD could be suppressed by inducing cheX expression (Fig. 1F), these results suggested that the loss of cheX restored motility to cells that expressed plzD.

To ascertain the specificity of plzD-mediated inhibition of motility, the spread though soft agar of wild type, ∆cheX and ∆cheZ cells expressing plzD was assessed. The expression of plzD inhibited the spread of ∆cheZ cells through soft agar 5-fold, the same extent as wild type cells (Fig. 1G). Conversely, the spread by ∆cheX cells expressing plzD was not inhibited. Inhibition of colony spread was restored following co-expression of cheX. These results suggested that inhibition of motility by PlzD correlated with the levels of CheX but not CheZ.

V. vulnificus CheX is a CheY-P phosphatase

The crystal structure of the 153 residue CheX of V. vulnificus (6VPW) was determined at 1.9 Å resolution (Fig. 2A). There were 94 water molecules in the final model (refinement statistics and the quality of the final model are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Data 2). Two polypeptide chains (A and B) crystalized as a dimer of six α-helices surrounding two six-stranded, anti-parallel β-sheets packed together at its center. Chain A included residues 3-153 of CheX (the first two residues were disordered in the crystal structure) and Chain B included residues 2-153 (the first amino acid and residues 31-36 of the loop region were disordered in the structure). Structural alignment of V. vulnificus CheX with homologs from Borrelia burgdorferi, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and Thermotoga maritima revealed that, despite these enzymes sharing only 27% pairwise identity, each exhibited a conserved dimer structure of six α-helices surrounding two six-stranded antiparallel β-sheets packed at its center (Fig. 2B). V. vulnificus CheX included the consensus D/S-X3-E-X2-N-X21-P residues of the phosphatase active site and an adjacent conserved G residue that mediates a turn important for forming the β-sheet of the dimer interface (Fig. S2).

A The CheX homodimer (Chain A in cyan and B in gray) of six α-helices surrounding two six-stranded anti-parallel β-sheets packed together at its center. The dashed line indicates loop residues 31-36 of Chain A that were disordered in the structure. B Structural alignment of V. vulnificus CheX (6VPW, cyan) with the structures from B. burgdorferi (3HZH, gold), D. desulfuricans (3HM4, green) and T. maritima (1XKO, pink). C A CheX monomer is shown with the conserved E91 and N94 residues of the E-X2-N motif in green stick configuration on the left and rotated 115° on the right. Residues that form a hydrophobic pocket are in orange. The L65 and L67 positions are in magenta. Water molecules are shown as red spheres.

Assessment of the structure revealed the nature of the instability of L65R and L65R/L67P substitutions. Both leucine residues are buried in the structure and contribute to hydrophobic packing (Fig. 2C). L65 forms a hydrophobic pocket with L23, L25, F61, and A146 while L67 forms a hydrophobic pocket with V42, A66, L81, V85, and V89. The instability of the first pocket by change of L65 to arginine would likely shift alpha helix 2 (residues 62-75), with the substitution of P67 for L67 likely breaking this helix entirely, resulting in poor folding and rapid proteolytic turnover. Thus, these mutations likely confer loss of function.

The structure of B. burgdorferi CheX complexed with its cognate CheY~P substrate38 showed that the phosphoryl group on E79 of CheY interacted directly with the long helix of CheX, which bears the conserved E-X2-N active site motif (E96 and N99). These residues are separated by a single helical turn and insert into the CheY phosphorylation site. They, together with Thr81 of CheY, orient a water molecule for hydrolytic attack on the phosphate moiety of CheY. This active site alignment was maintained in distant CheX homologs (Fig. S3), suggesting that this mechanism is likely conserved among most members of the CheC/CheX/FliY family. Structural overlay of V. vulnificus CheX with the B. burgdorferi CheX:CheY complex (Fig. S4) revealed closely aligned backbones for most of the secondary structure elements (rmsd = 1.03 Å for Cα atoms). Although two stretches of V. vulnificus CheX (residues 31-42 and 120-134) aligned poorly with CheX of B. burgdorferi, these residues localized to the intradimer surface and are not involved in substrate recognition. There were differences in the geometries of rotameric positions within the predicted CheX E-X2-N active sites (E91 and E96 did not align and E91 of V. vulnificus CheX cannot directly hydrogen bond with the analogous M16 of its anticipated CheY-P substrate, since methionine lacks the necessary hydrogen bond donor or acceptor atoms in its side chain), however, B. burgdorferi CheX was co-crystallized in the presence of the substrate with which it interacts (B. burgdorferi CheY), whereas V. vulnificus CheX was not. The overall agreement in alignment of V. vulnificus CheX with the B. burgdorferi CheX:CheY complex suggested that the substrate of V. vulnificus CheX was phosphorylated CheY.

Given the functional relationship between CheX and CheY in bacteria that lack CheZ and their physical association in B. burgdorferi, we assessed if these proteins interacted in V. vulnficus. As in V. cholerae39, V. vulnificus codes for five CheY homologs, only one of which (cheY3) participates in switching flagellar rotation. A ∆cheY3∆cheX strain that produced CheY3-CFP and 6HIS-CheX fusions were as motile as wild type cells (Fig. 3A). Fluorescence imaging revealed that approximately one-third of the CheY3-CFP signal localized to the cell pole while the remainder was diffuse (Fig. 3B). To determine if CheX and CheY interact in vivo, pull-down experiments from cell extracts of ∆cheY3∆cheX cells producing HIS-tagged CheX alone or with HA-tagged CheY were performed using nickel-coated magnetic beads, and recovered proteins were analyzed by immunoblot. A single band was observed with anti-HIS antibody for cells that only produced CheX, whereas two bands (corresponding to free and complexed CheX) were observed for cells producing CheX and CheY3 (Fig. 3C). After stripping and re-probing with anti-HA antibody, no band was observed for cells that only produced CheX, while a single band of the same size as the complex detected with anti-HIS antibody was observed for cells producing CheX and CheY3.

A Motility through soft agar of wild type (WT) cells carrying empty vectors and ∆cheY3∆cheX cells producing CheY3-CFP (+pcheY3-cfp) and 6HIS-CheX (+p6HIScheX) in media that lacked or contained (−/+) inducers (20 µM IPTG and 0.05% L-ara). B Representative phase and fluorescence images (×100 magnification) of V. vulnificus ∆cheY3∆cheX cells producing CheY3-CFP. Scale bar, 1 µm. C Western blot of pull-downs with Ni-coated beads from extracts of ∆cheY3∆cheX cells producing (+) 6HIS-CheX (X, 15.5 kDa) and/or CheY3-HA (Y, 14.3 kDa). Anti-HIS antibody (HIS) was used to detect CheX. The blot was stripped for subsequent detection of CheY3 with anti-HA antibody (HA). D Western blot with anti-HA antibody of phosphorylated HA-tagged CheY3 (CheY3-P) before and after incubation alone or with purified V. vulnificus CheZ or CheX. The black and white arrowheads denote the positions of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated CheY3, respectively. E Schematic of the chemotaxis assay. Wild type (WT) and mutant strains (∆cheY3, ∆cheX, ∆cheZ, ∆cheXZ) are separately inoculated into minimal soft agar at a point equidistance between an attractant (a; 10 mM L-serine) and a blank (b; water), and chemotactic zones (colored regions) to the left (gray area) and right (white area) of the inoculation point (i) are recorded. F Stacked bar plot of the chemotactic zones towards the blank (gray bars) and attractant (white bars) for each strain. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate assays. Statistically significant differences between the zones (the stacked areas of gray and white within an individual bar, which equate to the chemotactic areas in the gray and white regions in E) for each strain were determined by multiple unpaired t-tests with a Welch correction. G Grouped bar plot of the chemotactic zones in (E). Statistically significant differences in chemotaxis towards the blank (gray bars) and attractant (white bars) for each mutant relative to WT were determined by one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. H Colony spread through soft agar of wild type (WT), ∆cheX, ∆cheY3, and ∆cheZ cells. To the right is a bar plot of the corresponding motility zones for each strain. Statistically significant differences from wild type were determined by one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. p values: *, <0.05; **, <0.01; ***, <0.001; ****, <0.0001; ns no significant difference.

To ascertain if V. vulnificus CheX functioned as a CheY-P phosphatase, the phosphorylation status of HA-tagged CheY3 was assessed before and after incubation with CheZ or CheX by western blot analysis using Phos-tag gels. Upon purification from ∆cheX∆cheZ cells, two distinct bands corresponding to unmodified and phosphorylated CheY3 were detected (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the addition of either CheZ or CheX resulted in only a single band indicative of unmodified CheY3. Collectively, these results suggested that CheX and CheY3 interacted in V. vulnificus and that CheX was a functional CheY-P phosphatase.

CheX and CheZ exert distinct effects on V. vulnificus chemotaxis

We assessed the chemotactic behavior of V. vulnificus strains lacking cheY3, cheX and/or cheZ by separately inoculating them into minimal media soft agar at a point equidistance between an attractant and a blank and recording their biased movement (Fig. 3E). Wild type, ∆cheX, ∆cheZ and ∆cheXZ cells exhibited biased movement toward attractant by at least 3-fold over the blank (Fig. 3F). The exception was the ∆cheY3 strain, which did not exhibit any chemotactic bias or migrate from the inoculation point. Chemotaxis by ∆cheZ cells was not significantly different from wild type, whereas chemotaxis by ∆cheX, ∆cheY3 and ∆cheXZ strains decreased 1.7, 8 and 2.4-fold, respectively, toward the blank (Fig. 3G, gray bars) and 1.8, 27 and 2.5-fold toward the attractant (Fig. 3G, white bars). These results suggested that the loss of CheY3 or its reduced collective dephosphorylation suppressed the chemotactic response of V. vulnificus and that CheX and CheZ jointly regulate but exert distinct effects on V. vulnificus chemotaxis.

CheX expands the excursion range of swimming cells by decreasing the flagellar switching frequency

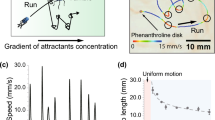

V. vulnificus swimming through soft agar revealed that the effect of cheZ deletion on motility was negligible relative to wild type cells, whereas the loss of cheX decreased colony spread by 33% (Fig. 3H). Cells that lacked cheY3 were unable to spread from the point of inoculation. Monitoring swimming behavior of wild-type cells at the single-cell level revealed forward and reverse runs interspersed with re-orientations in the x, y, and z planes that promoted extensive exploration of the surrounding space at an average speed of 73 µm/s (Fig. 4A, B). While the swimming pattern and mean speed (68 µm/s) of ∆cheZ cells were not significantly different from wildtype cells, the trajectories of ∆cheX cells revealed directional changes that occurred in rapid succession (i.e. a ping-pong pattern of short CW and CCW runs), resulting in striking starburst patterns connected by short linear runs and a lower average speed of 59 µm/s. Conversely, cells that lacked cheY and appeared non-motile in soft agar were in fact highly mobile (>75 µm/s) but failed to change direction, producing long unidirectional curvilinear traces. Hence, the essentially unconfined displacement of ∆cheY3 cells that were unable to change direction led to a complete loss of chemotaxis.

A 3D swimming motility traces (top panel) of wild type, ∆cheX, ∆cheZ, and ∆cheY cells. Speed trace of a single representative cell for each strain, tracked for a similar length of time (with the exception of ∆cheY) and scaled to the equivalent relative dimensional space (bottom panel). A color speed bar is on the left. Violin plots showing B the mean speed, C the flagellar switching frequency (the number of flagellar motor rotational changes per second) and D confinement ratio (net displacement/total distance traveled) for each strain. NB, the cheY3 deletion mutant is unable to change direction hence the switching frequency is 0. Confinement values close to 0 indicate highly confined movement and those close to 1 indicate unconstrained travel of constant orientation (linear). Dashed horizontal lines denote the median, first and third quartiles for the data range from at least 100 tracks for each strain. Statistically significant differences relative to wild type (WT) were determined by one-way ANOVA with a Dunn’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. p values: **, <0.01; ****, <0.0001; ns no significant difference.

To further characterize the effect of CheX on V. vulnificus swimming behavior, the flagellar switching frequency (the number of flagellar motor rotational changes per second) and confinement ratio (net displacement/total distance traveled) of trajectories for wild type, ∆cheX, ∆cheY3 and ∆cheZ cells was quantified. The switching frequency for ∆cheZ and ∆cheX cells increased 1.7 and 2.8-fold, respectively, relative to wild type cells (Fig. 4C), whereas ∆cheY3 cells failed to reverse direction or flick. These results suggested that while the loss of CheZ had a modest impact on reversal and flick events of swimming cells, the loss of CheX significantly increased the frequency of these events and the loss of CheY3 completely abolished them. Notably, the confinement ratio, a measure of the efficiency of displacement of a cell from starting position to endpoint, decreased only slightly for ∆cheZ cells relative to that of wild type (Fig. 4D). Conversely, the displacement efficiency of ∆cheX cells was half that of wildtype cells, while ∆cheY3 cells exhibited essentially unconfined displacement. Notably, the combined deletion of cheX and cheZ impaired movement to the greatest extent (Fig. S5A). These findings suggested that while the loss of CheZ alone resulted in only a minor perturbation of V. vulnificus swimming behavior, the absence of CheX (either alone or together with CheZ) or CheY3 produced more severe and opposing dysregulatory effects on the frequency of directional changes. However, the loss of CheX, which decreases the excursion range of swimming V. vulnificus cells, could not restore efficient displacement (Fig. S5B) or chemotaxis (Fig. S5C) to ∆cheY3 cells that cannot change direction or chemotax, suggesting that the effect of CheX on V. vulnificus foraging is dependent on CheY3.

Occurrence of CheX and CheZ homologs across bacterial genomes

Putative CheX homologs exhibited pronounced sequence divergence across bacterial classes, particularly among ε-proteobacteria and α-proteobacteria, suggesting potential functional divergence or lineage-specific variability in CheX-like proteins across these clades. To enhance lineage-specific sensitivity, we stratified the putative CheX homologs by bacterial class and independently regenerated class-specific profile Hidden Markov models (HMMs). This strategy enabled more accurate modeling of sequence diversity and improved homolog detection performance within individual phylogenetic lineages (Fig. S6A). To further validate the search results, we incorporated gene neighborhood conservation as an additional criterion by examining syntenic relationships between CheX and its flanking genes. These syntenic arrangements were found to be highly conserved within certain taxonomic classes, particularly γ-proteobacteria and ε-proteobacteria (Dataset S1, tab CheX.context.allbact). For example, the V. vulnificus CheX homolog is flanked upstream by a gene encoding the zinc uptake transcriptional repressor Zur, and downstream by genes encoding a secondary thiamine-phosphate synthase (YjbQ), a DUF481 domain-containing protein, and a PBP1A family penicillin-binding protein. Across γ-proteobacteria, 8560 putative CheX homologs were identified with proximity to one or more of these flanking genes. These homologs exhibited a wide range of sequence identity to V. vulnificus CheX, from 100% to as low as 17%, further supporting the utility of synteny-based contextual validation within this lineage. We also identified 3300 putative CheX homologs from ε-proteobacteria, which were commonly embedded in a gene neighborhood featuring upstream genes encoding N-(5’-phosphoribosyl) anthranilate isomerase and tryptophan synthase subunits alpha and beta, and downstream genes encoding the flagellar motor switch protein FliN and cytochrome-c peroxidase. Similarly, 3265 putative CheX homologs from β-proteobacteria were typically found to be preceded by genes encoding an MCP four-helix bundle domain-containing protein and a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein.

We applied a similar strategy in the detection of CheZ homologs by reconstructing class-specific profile HMMs tailored to taxonomic context. This approach resulted in the identification of 86,501 putative CheZ homologs from γ-proteobacteria and 10,372 from β-proteobacteria, most of which were typically associated with a homolog of the chemotaxis response regulator CheY, consistent with the gene neighborhood observed around the V. vulnificus CheZ homolog. Additionally, we identified 7949 putative CheZ homologs from ε-proteobacteria, which were frequently characterized by downstream genes encoding a U32 family peptidase and a DUF3972 domain-containing protein, highlighting a distinct syntenic configuration in this lineage.

A total of 107,575 genome assemblies were identified as containing either a CheX and/or CheZ homolog (Dataset S1, tab CheX_CheZ_occurrence). Analyses revealed taxonomic patterns for CheX and CheZ homologs that were consistent with lineage-specific associations, although these patterns were potentially biased due to more frequent sequencing of certain taxa that likely skew the apparent distribution of these homologs across bacterial lineages. Given the inherent limitations of draft assemblies (incomplete genomic information and potentially missing genes) and the difficulty in determining whether the apparent absence of a homolog reflects the true biological circumstance or a technical omission, further analysis was restricted to complete genome assemblies, where gene absence can be more confidently inferred. Among these, 12.9% were annotated as complete with 1.6% resolved to the chromosome level (Fig. S6B). Of these, 5.1% coded only for CheX, 79.9% only for CheZ and 15% coded for both (Fig. S6C). Further analysis revealed distinct and consistent taxonomic patterns; nearly all genome assemblies from the class Bacillota encode a CheX homolog but lacked CheZ, and assemblies containing only the CheZ homolog were concentrated within specific genera, most of which belonged to the family Enterobacteriaceae and included Escherichia, Salmonella, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas and Bordetella (Supplementary Data 1 and Table S2). Notably, of these assemblies, those that coded for CheX typically also coded for CheZ, suggesting a strong co-occurrence when CheX was present. Co-occurrence was predominantly associated with members of the class γ-proteobacteria, followed by ε-proteobacteria and β-proteobacteria (Fig. S6D). At the genus level, the most frequent representatives were Vibrio, Campylobacter, Burkholderia and Aeromonas (Fig. S6G), a trend that was consistently reflected in the most common families and orders within this group (Fig. S6E, F). Of the 129 Vibrio species with publicly available genome assemblies, all coded for both CheX and CheZ (Dataset S1), as did most isolates for each species (e.g. 99.7% of V. cholerae isolates coded for both CheX and CheZ, and all but one V. parahaemolyticus isolate coded for both). Collectively, these results suggest a taxonomic specificity for the co-occurrence of CheX and CheZ homologs in bacterial genomes.

We investigated the relationship between bacterial flagellar architecture and the co-occurrence of CheX and CheZ homologs across genomes. Our dataset encompassed 141 bacterial genera, each represented by a minimum of five complete genome assemblies encoding CheX, CheZ or both, and flagellar pattern was simplified to a binary categorization of polar or peritrichous (Table S3). This refinement revealed a subtle correlation between the occurrence of cheX and cheZ in genomes and flagellar patterns. Among genomes coding only for CheX, six genera exhibit polar flagellation while seventeen have peritrichous flagella (Fig. S7), suggesting that the presence of CheX alone is more commonly associated with a peritrichous flagellar arrangement. Among genomes coding for CheZ exclusively, slightly more than half exhibit polar flagella, with the remainder peritrichous. Co-occurrence was most frequently observed among genera with polar flagella, with the exception of Sulfurospirillum and Grimontia, which are peritrichous.

Discussion

Resolving conflicts—e.g. in cells of biofilm consortia that must resolve the opposing pressures of constrained motility and nutrient-limitation—is a formidable challenge40,41,42. Bacterial chemotaxis engages motility and is dependent on the rapid and reversible phosphorylation of CheY4. In E. coli and related species, CheZ serves as the principal CheY-P phosphatase, efficiently catalyzing the removal of the phosphoryl group to terminate the chemotactic response. Alternatively, CheX functions as a CheY-P phosphatase predominantly in bacterial lineages lacking CheZ. Intriguingly, some bacteria, including most Vibrio species, possess both CheX and CheZ, but why is unclear. Applying a selective pressure by expressing the c-di-GMP effector PlzD, which markedly attenuates V. vulnificus motility, led to the emergence of suppressor mutations that mapped to cheX. Our investigation revealed that decreased levels of CheX (evidenced by the insertion of an IS element that disrupted cheX expression in some suppressor mutants, reduced stability of the CheXL65R and CheXL65R/L67P variants compared to wild-type CheX, and restoration of motility in ∆cheX cells expressing plzD), rather than its interaction with PlzD, was responsible for restoring motility. We propose a unique role for CheX in V. vulnificus, whereby specifically decreasing the level of this chemotaxis component can be used to tactically relieve foraging constraints imposed by PlzD-mediated motility inhibition.

In B. burgdorferi, CheX is the sole CheY-P phosphatase, and its deletion results in a non-chemotactic phenotype characterized by persistent cellular flexing and a complete loss of translational motility14,17,43,44. In contrast, deletion of cheX in V. vulnificus led to only a partial impairment of motility and chemotactic proficiency. We suggest that CheX has a unique and additional role beyond that of CheZ and that their interplay allows for nuanced control of motility and chemotactic signaling to optimize the balance between local searching and long-range exploration14. In support of this notion, CheX can partially complement the loss of other phosphatases in Bacillus subtilis and related species but does not fully replicate their adaptational roles, indicating non-redundant functions13. Given that V. vulnificus CheX acts as a CheY-P phosphatase and is diffusely distributed throughout the cytoplasm, it is plausible that the aberrant swimming behavior observed in ΔcheX mutants arises from an increase in the cellular CheY-P pool and its rapid re-engagement with the flagellar motor. These phenotypic effects are strictly dependent on the presence of CheY, as its absence abolishes all directional changes. Our previous investigations demonstrated that PlzD attenuates the frequency of directional changes in motile cells, resulting in extended, curvilinear swimming trajectories that constrain spatial exploration28. Cells lacking CheX exhibited a significantly elevated switching frequency compared to those deficient in CheZ. The selective emergence of suppressor mutations in cheX but not cheZ suggests that the increased rotational switching and turn frequency arising from reduced CheX activity more effectively offset the constraints of linear swimming behavior caused by persistent PlzD signaling, and enabled more expansive exploration of the environment by the bacterial population.

In the estuarine water column where Vibrio reside, chemotaxis enables bacteria to exploit fleeting nutrient hotspots and to colonize particulate matter or other micro and macro marine organisms45,46,47,48,49. Our results suggest that altering the chemotactic network may also aid in the dispersal of bacteria from the highly structured microenvironments of biofilms42 that are being maintained by c-di-GMP signaling. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the c-di-GMP effector MapZ interacts with the chemoreceptor methyltransferase CheR1 to promote chemotaxis50 and prolonged incubation of a non-chemotactic E. coli mutant that lacked all chemoreceptors led to the emergence of a motility suppressor bearing a transposon insertion in cheZ51, the sole CheY-P phosphatase. It was proposed that the combination of decreased phosphatase activity, continued CheA activity and long half-life of CheY-P led to its accumulation in the cell and increased tumbling frequency2. Thus, modulating chemotaxis may be a general strategy to circumvent motility restrictions, including those imposed by c-di-GMP effectors. Since it is plausible that cytoplasmic CheX would have greater opportunity to dephosphorylate CheY-P than polarly localized CheZ52,53, it may act globally to reduce CheY-P levels, while CheZ may provide a more targeted or regulated dephosphorylation of CheY-P at the cell pole (Fig. 5), thereby supporting efficient chemotaxis and foraging behavior in organisms where the presence of CheX alongside CheZ might otherwise appear redundant.

Left, MCPs, CheA, CheW, CheB and CheV collectively control the phosphorylation of CheY (Y, gold). CheY-P (green) interacts with the flagellar motor, switching its direction of rotation. CheZ (Z, blue) stimulates polar CheY-P dephosphorylation, displacing it from the switch complex to decrease the switch rate and favor longer runs, while CheX (X, pink) dephosphorylates cytoplasmic CheY-P to maintain cellular homeostasis. The loss of CheX results in increased cellular CheY-P levels, increasing the switch rate.

B. burgdorferi CheX was shown to be a binding partner and substrate of the serine protease HtrB54, suggesting that targeted degradation of CheX may function to modulate the chemotactic response in this species. It is conceivable that the V. vulnificus HtrA homolog functions similarly to regulate the output of its chemotaxis network to circumvent the motility constraints imposed by PlzD activity. Intriguingly, deletion of V. cholerae motW was reported to cause a reduction in both directional switching frequency and swimming velocity in liquid55, similar to the phenotype of V. vulnificus cells over-expressing plzD. Notably, mutations in vc0377 (cheX) suppressed these ∆motW phenotypes. Although the role of VC0377 was not demonstrated, it paints a complex picture of multiple converging inputs for CheX-mediated motility regulation in Vibrio species.

The CheC/CheX/FliY family is characterized by a consensus sequence, D/S-X3-E-X2-N-X21-P, which delineates the active site of the phosphatase15,18. Structural analysis revealed that V. vulnificus CheX adopted a conserved dimeric fold with an active site architecture similar to CheX homologs from B. burgdorferi38, T. maritima17 and D. desulfuricans, despite sharing only 27% amino acid identity. The Glu and Asn residues within the conserved (-EXXN-) motif are separated by a single turn on the long α-helix, with the E residue participating in binding to CheY-P and the N residue facilitating phosphatase activity by forming a hydrogen bond with a water molecule that is positioned for nucleophilic attack on the CheY3 phosphorylation site38. CheX of V. vulnificus associated with and exhibited phosphatase activity towards CheY, despite the lack of hydrogen bonding between its active site E91 and M16 of CheY in the predicted complex. This implies that essential catalytic features were maintained and operated through a conserved mechanism shared across distant homologs, and underscores the evolutionary versatility of the CheX scaffold in accommodating active-site variation while preserving core functional attributes. It is also possible that this apparent shortcoming is compensated for by alternative bonds in the native structure or is tolerated because the genome also codes for a functional CheZ.

CheZ, originally thought to be restricted to β- and γ-proteobacteria, is also present in α, δ and ε-proteobacteria as well as other classes including Aquificia, Deferribacteres, Nitrospiria and Sphingobacteriia56,57,58. CheX is also found in diverse bacterial classes59,60. Co-occurrence of CheX and CheZ homologs was most common in the classes α, β, ε and γ-proteobacteria, as well as Desulfovibrionia. Our comparative analysis revealed a subtle association between the genomic distribution of cheX and cheZ and flagellar architecture. Genomes encoding CheX alone more frequently exhibited peritrichous flagellation, whereas those coding only for CheZ were observed equally among bacteria with polar and peritrichous flagellar arrangements. Co-occurrence of cheX and cheZ was most frequently observed in genera with polar flagella. From an evolutionary perspective, the presence of both cheX and cheZ in the genomes of some bacteria may represent a transitional state. Conversely, it may be that their co-occurrence is maintained by selective pressures favoring their combined function (i.e. adaptive retention) to confer robustness and versatility to chemotactic control. This may be judicious for species that transition between unique environments (e.g. estuarine and enteric), so that effective motility is maintained in both61.

The unique role of CheX in a bacterium that also possess CheZ likely reflects a need for robust, adaptable chemotactic signaling, and their distinct effects on motility and chemotaxis suggests that their co-occurrence expands the repertoire available for bacteria to navigate complex environments. Notably, a strain deficient in both CheX and CheZ retained approximately 50% chemotactic efficiency relative to the wildtype strain. Given that effective chemotaxis relies on the rapid dephosphorylation of CheY-P to synchronize directional switching with environmental cues, it is possible that CheY-P undergoes sufficient spontaneous autodephosphorylation in the absence of these phosphatases. Alternatively, the existence of an as-yet-undefined CheY-P phosphatase or a molecular phosphate sink in V. vulnificus cannot be excluded. Such a strategy, in which one CheY variant interacts with the flagellar switch and another serves as a phosphate sink in lieu of a phosphatase, has been demonstrated in other bacteria62,63,64. Analogous to V. cholerae, V. vulnificus encodes five CheY homologs, of which only CheY3 is required for modulating flagellar rotation39; it is conceivable that one or more of the remaining homologs functions as a phosphate sink. Future investigations should aim to elucidate the dynamic interplay between CheX and CheY-P in V. vulnificus, identify additional mechanisms regulating CheY-P levels in vivo, and determine the broader physiological ramifications of this regulatory network for V. vulnificus pathogenesis and environmental persistence. Furthermore, comparative studies are warranted to reveal how CheX and CheZ operate in other bacterial taxa where they co-exist.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

V. vulnificus strain ATCC27562 was used. E. coli S17.1λπ was used for cloning, plasmid maintenance, and conjugation to V. vulnificus. Luria-Bertani broth and agar were purchased from BD Difco. The following antibiotics and additives were purchased from Sigma and used at the indicated concentrations: ampicillin (Ap) at 100 µg ml−1, trimethoprim (Tp) at 10 µg ml−1, gentamycin (Gm) at 35 µg ml−1, L-arabinose (ara) at 0.05% and isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 50 µM. Instant Ocean® was used at 20 parts per thousand (IO20 ppt) and tryptone was added to 1% where indicated.

Soft-agar swimming assays and isolation of suppressors of plzD expression

Plates (0.3% agar) of IO20 with tryptone, Ap and 5 µM IPTG were inoculated with 2 μl of V. vulnificus carrying pC2X6HT-plzD that had grown overnight in the same media lacking IPTG. Plates were incubated overnight at 30 °C. Samples were collected from flares that emerged and re-streaked to obtain isolated colonies. Plasmids were recovered from each suppressor mutant and separately re-introduced into wild type V. vulnificus cells to verify their functionality. Isolates identified as bearing chromosomal mutations were sent for whole genome sequencing. The motility in soft agar of other mutants was assayed in the same manner and the diameter of motility zones was measured. All assays were done in triplicate.

Construction and complementation of the mutant strains

Replacement of cheX with a Tp resistance gene was accomplished as follows: PCR fragments that included 1 kb upstream to the first 9 bp of cheX (primers DcheX-1 and DcheX-TpK7-2) and the last 9 bp to 1 kb downstream of cheX (primers DcheX-TpK7-3 and DcheX-4) were amplified and fused to a central Tp antibiotic resistance cassette (primers TmR-F and TmR-R). The primers included complementary 35 bp overhangs to fuse the PCR products by Gibson assembly (New England BioLabs). V. vulnificus strains carrying the pMMB-TfoX expression plasmid65 were induced overnight in LB medium containing ampicillin and IPTG at 30 °C. A 10 µl aliquot of cells was added to 500 µl of IO-20 containing 100 µM IPTG and the Gibson reaction mixture. The transformation mixture was incubated statically overnight at 30 °C. The next day, 1 ml of LB medium was added to the tube, and the cells were allowed to outgrow for 3 h before plating on LB Tp plates. Allelic replacement of the target region was confirmed by PCR. This method was also used to replace cheZ with a Cm resistance cassette and to create the ∆cheX∆cheZ strain. A markerless deletion of cheY was created using the pRE112 sucrose counter-selection plasmid66. For complementation, the respective gene was amplified, cloned downstream of the Ptac promoter in pC2X6HT or pSU38GT67 and sequenced. The plasmid was conjugated to the respective mutant and expression was induced with 10 µM IPTG or 0.025% ara, respectively. See Table S4 for constructs and primer sequences.

Fluorescence microscopy

The pC2X6HT plasmid expressing plzD-gfp, cheX-rfp or cheY-cfp was conjugated to the indicated V. vulnificus strains. Strains were grown in IO20 with tryptone and Ap and expression was induced with IPTG (25 µM) for 4 h and images were captured with an Olympus IX83 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu electron microscopy charge-coupled-device (EM-CCD) camera and a 100X Phase objective. Images were processed using cellSense (Olympus).

Motility tracking

For 3D tracking, cells were grown overnight in tryptone supplemented IO20 media at 30 °C. An aliquot was gently washed once in the same medium (5 min at 4000 × g) and then diluted to an OD600 of 0.1 in fresh IO20 medium lacking tryptone. Tracking chambers were made by layering three parafilm frames between a microscope slide and a 22 × 22 mm no. 1.5 coverslip. The chamber was sealed by placing it in a 55 °C dry oven for 10 min. Bacteria were flowed into the chamber at one edge by capillary action. The edges of the unit were sealed with hot VALAP, and the samples were immediately imaged on the above-mentioned microscope equipped with an Olympus long-working-distance (LWD) air condenser (numerical aperture [NA], 0.55) and an Olympus LUCPLFLN LWD 40X phase-contrast objective (Ph2; NA, 0.6). The correction collar was set to 1.2. For each movie recording, frames were acquired at a rate of 15 Hz and an exposure time of 5 ms with a Hamamatsu Orca-R2 camera (1344 by 1024 pixels). The objective was positioned so that the focus was 40 µm above the coverslip. The data were saved as a stack of 16-bit tiff files of 300 images each. Image stacks were background corrected and aligned to a 3D position reference library in Matlab using a custom-written tracking program to analyze motility behavior68,69. Each reorientation event (flicks and reversals) identified by the program was manually confirmed based on the angle and swimming speed between the corresponding vectors for 600 trajectories prior to statistical analysis. Trajectories with an average speed of less than 10 µm/s or with a duration of less than 50 frames were ignored. Plots were created using data from three stacks of three biological replicates for each strain. Traces from a single representative experiment are shown.

For 2D tracking, the motility of early-exponential (OD600 of 0.1) cells was recorded using dark-field microscopy on an Olympus IX83 microscope equipped with a ×20 ELWD objective. A stack of at least 150 frames (100 ms exposure time) was recorded for each sample and the movement of 50 randomly sampled motile cells per stack was traced to calculate the switching frequency and confinement ratio (a measure of the efficiency of movement of a cell from starting position to endpoint) using the TrackMate plugin (v 7.14.0)70,71 in Fiji72. Data from three stacks of three biological replicates were analyzed for each strain. Traces from a single representative experiment are shown.

Immunoprecipitation and detection

V. vulnificus ∆cheX∆cheY cells expressing HIS-tagged CheX from pC2X6HT and HA-tagged CheY from pSU38GT were grown overnight in 5 ml IO20 Ap Gm at 20 °C. The next day, cells were diluted 1:100 in 50 ml of fresh media containing 100 µM IPTG and 0.1% L-ara and grown to an OD600 of 0.5. The cells were pelleted at 5000 × g for 10 min, washed twice with IO20, resuspended in B-PER Reagent (Thermo Scientific) containing 1 mM bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) and the extracts were incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 5 min to pellet cellular debris. A total of 50 µL of Washed HisPur Ni-NTA magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) was added to the supernatant and the samples were incubated with gentle rolling at room temperature for 30 min. The beads were then washed three times with B-PER to remove non-specifically bound proteins and contaminants. Bound proteins were eluted with buffer containing 250 mM imidazole and separated on NuPAGE 4 to 12% Bis-Tris pre-cast protein gels (Invitrogen). HA-tagged wildtype CheX and the CheXL65R and CheXL65RL67P variants were expressed from pSU38GT in the ∆cheX strain for immunodetection. His-tagged V. vulnificus CheX and CheZ were expressed and purified from BL21(DE3) cells using HisPur Ni-NTA magnetic beads as described above and stored in TKM buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol and 10% glycerol) at −20 °C until use. HA-tagged CheY was purified from V. vulnificus ∆cheX∆cheZ cells using anti-HA magnetic beads (Thermo Scientific) and then 100 µM was incubated alone or with an equal concentration of purified CheZ or CheX in TKM buffer for 1 min at 37 °C. The reactions were stopped with 4x SDS-PAGE sample buffer (Millipore) and separated by Phos-tag SDS-PAGE (Wako, Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-His (BioRad) and anti-HA (Thermo Scientific) HRP antibodies were used for detection of tagged proteins.

Purification of recombinant Vibrio vulnificus CheX for crystallization

The full-length open reading frame for cheX (vv1_1397) was amplified from genomic DNA of V. vulnificus CMCP6 (NCBI reference sequence NC_004459.3) and the PCR product was cloned using ligation independent cloning as described previously into pMSCG53 vector to expressed recombinant protein with an N-terminal 6×His tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site73. Recombinant CheX was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)-Magic cells in 3 liters High Yield M9 SeMet media (Medicilon Inc.) supplemented with 200 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin at 25 °C. The bacterial pellets collected by centrifugation were resuspended in 50 mM Tris pH 8.3, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630, flash frozen, and stored at −30 °C until purification. Thawed cells were lysed by sonication and lysate was clarified by centrifugation. The protein was purified using an ÅKTAxpress system (GE Healthcare) as previously described74. The supernatant was loaded onto a HisTrapFF (GE Healthcare) column in loading buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP), and 5% glycerol). The column was washed with 10 column volumes (cv) of loading buffer and 10 cv of washing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 1 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol). The protein was eluted with elution buffer (10 mM Tris pH 8.3, 500 mM NaCl, 1 M imidazole) and then loaded onto a Superdex 200 26/600 column and separated in loading buffer. The 6xHis-tag was cleaved by recombinant TEV protease in ratio 1:20 (protease:protein) overnight at 22 °C and passed over a HisTrapFF column using loading buffer with 5 mM imidazole. The cleaved protein was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 5 mM TCEP buffer in presence or absence of 500 mM NaCl and concentrated to 10.4 and 9.2 mg ml−1 respectively, prior to crystallization.

CheX crystallization

Concentrated protein was set up for crystallization in 2-μl crystallization drops (1:1 (protein:reservoir solution) in 96-well crystallization plates (Corning) using commercially available screens. Diffraction quality crystals of CheX grew from 100 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.5), 25% (w/v) PEG 3350 (Classic’s II, condition #43) and protein solution with 500 mM NaCl. The crystal was cryoprotected in reservoir solution and flash cooled in liquid nitrogen for data collection.

Data collection and processing, structure solution and refinement

Diffraction data were collected on the 21-ID-F beamline of the Life Science Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne National Laboratory, USA. A total of 200 frames were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL -3000 (PMID 16855301)75. Data collection and processing statistics are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Data 2. The structure of CheX was solved by molecular replacement with Phaser76 from the CCP4 suite77 using the structure of the CheC-like protein from Shewanella oneidensis (PDB entry 3h2d) as a search model. The initial solution underwent several rounds of refinement in REFMAC v.5.578 and manual model building and corrections using Coot79. Water molecules were generated using ARP/wARP80. Translation–libration–screw (TLS) groups81 were created and TLS corrections were applied during the final stages of refinement. MolProbity82 was used to monitor the quality of the model during refinement and for final validation of the structure. The final model and diffraction data were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB entry 6VPW).

Structural modeling

The structures of CheX homologs were predicted using AlphaFold383. Chimera84 was used for molecular visualization. Five homology models were generated for each protein, and the model with the best overall agreement score was analyzed further.

Detecting CheX and CheZ homologs across bacterial genomes

To identify homologs of CheX and CheZ across bacterial genomes, we constructed profile HMMs85 using the protein sequences encoded by the genes aot11_RS08725 and aot11_RS1132, respectively, from V. vulnificus NBRC 15645 (GenBank accession: NZ_CP012881.1). These sequences were initially queried using BLASTP86 against a curated dataset comprising annotated protein sequences from 617 complete and publicly available Vibrio genome assemblies. Among these, 602 assemblies were found to contain both CheX and CheZ homologs. Multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) were generated from the non-redundant sets of top-scoring sequences using MUSCLE version 3.8.155187, and served as input for constructing the initial profile HMMs representing conserved sequence features. These HMMs were then used to search a comprehensive protein sequence database derived from all publicly available bacterial genome assemblies, employing HMMER version 3.2.188. Searches were conducted iteratively, with newly identified homologs incorporated into successive rounds to refine the HMMs and enhance detection sensitivity. Despite iterative refinement of the CheX profile HMM, several false positives were encountered. Notably, homologs of FliN, which encodes the flagellar motor switch protein, were frequently assigned high similarity scores and erroneously classified as CheX homologs, likely due to partial sequence overlap between CheX and FliN. To address this issue, a profile HMM constructed from representative FliN sequences was employed as a negative training set. Hits identified by the CheX HMM that also matched the FliN HMM were flagged as false positives and excluded from further analysis.

In our analysis of potential correlations between bacterial flagellar architectures and the co-occurrence of cheX and cheZ within genomes, inclusion criteria required that a genus possess at least five complete genome assemblies encoding either gene, with the assigned flagellation category supported by at least 5% of those assemblies. For instance, the genus Pseudomonas is represented by 1375 assemblies encoding solely CheZ, one encoding CheX alone, and one encoding both enzymes; consequently, Pseudomonas was classified as ‘CheZ only’ in accordance with these thresholds. By contrast, Campylobacter comprises 127 assemblies with CheZ alone and 350 encoding both CheX and CheZ, thus meriting its classification as both ‘CheZ only’ and ‘Both’.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was determined by the Student’s t test (two-tailed distribution with two-sample, equal variance) when directly comparing two conditions or a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by pairwise comparisons with a post hoc adjustment (see figure legends) when comparing data with multiple samples.

References

Falke, J. J., Bass, R. B., Butler, S. L., Chervitz, S. A. & Danielson, M. A. The two-component signaling pathway of bacterial chemotaxis: a molecular view of signal transduction by receptors, kinases, and adaptation enzymes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 457–512 (1997).

Wadhams, G. H. & Armitage, J. P. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 1024–1037 (2004).

Sourjik, V. & Wingreen, N. S. Responding to chemical gradients: bacterial chemotaxis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 262–268 (2012).

Colin, R., Ni, B., Laganenka, L. & Sourjik, V. Multiple functions of flagellar motility and chemotaxis in bacterial physiology. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 45, fuab038 (2021).

Maddock, J. R. & Shapiro, L. Polar location of the chemoreceptor complex in the Escherichia coli Cell. Science 259, 1717–1723 (1993).

Sourjik, V. & Berg, H. C. Receptor sensitivity in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 123–127 (2002).

Yuan, J., Fahrner, K. A., Turner, L. & Berg, H. C. Asymmetry in the clockwise and counterclockwise rotation of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12846–12849 (2010).

Xie, L., Altindal, T., Chattopadhyay, S. & Wu, X. L. Bacterial flagellum as a propeller and as a rudder for efficient chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2246–2251 (2011).

Son, K., Menolascina, F. & Stocker, R. Speed-dependent chemotactic precision in marine bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8624–8629 (2016).

Zhao, R., Collins, E. J., Bourret, R. B. & Silversmith, R. E. Structure and catalytic mechanism of the E. coli chemotaxis phosphatase CheZ. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9, 570–575 (2002).

Silversmith, R. E. et al. CheZ-mediated dephosphorylation of the Escherichia coli chemotaxis response regulator CheY: role for CheY glutamate 89. J. Bacteriol. 185, 1495–1502 (2003).

Scharf, B. E., Fahrner, K. A., Turner, L. & Berg, H. C. Control of direction of flagellar rotation in bacterial chemotaxis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 201–206 (1998).

Muff, T. J., Foster, R. M., Liu, P. J. Y. & Ordal, G. W. CheX in the three-phosphatase system of bacterial chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7007–7013 (2007).

Motaleb, M. A. et al. CheX is a phosphorylated CheY phosphatase essential for Borrelia burgdorferi chemotaxis. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7963–7969 (2005).

Muff, T. J. & Ordal, G. W. The diverse CheC-type phosphatases: chemotaxis and beyond. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1054–1061 (2008).

Sircar, R., Greenswag, A. R., Bilwes, A. M., Gonzalez-Bonet, G. & Crane, B. R. Structure and activity of the flagellar rotor protein FliY a member of the CheC phosphatase family. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 13493–13502 (2013).

Park, S. Y. et al. Structure and function of an unusual family of protein phosphatases: the bacterial chemotaxis proteins CheC and CheX. Mol. Cell 16, 563–574 (2004).

Szurmant, H. & Ordal, G. W. Diversity in chemotaxis mechanisms among the bacteria and archaea. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 301–319 (2004).

Römling, U. Cyclic di-GMP signaling—where did you come from and where will you go? Mol. Microbiol. 120, 564–574 (2023).

Römling, U. & Amikam, D. Cyclic di-GMP as a second messenger. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 218–228 (2006).

Römling, U., Gomelsky, M. & Galperin, M. Y. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 629–639 (2005).

Commichau, F. M., Dickmanns, A., Gundlach, J., Ficner, R. & Stülke, J. A jack of all trades: the multiple roles of the unique essential second messenger cyclic di-AMP. Mol. Microbiol. 97, 189–204 (2015).

Wang, R., Wang, F., He, R., Zhang, R. & Yuan, J. The second messenger c-di-GMP adjusts motility and promotes surface aggregation of bacteria. Biophys. J. 115, 2242–2249 (2018).

Sauer, K. et al. The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 608–620 (2022).

Han, Q. et al. Flagellar brake protein YcgR interacts with motor proteins MotA and FliG to regulate the flagellar rotation speed and direction. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1159974 (2023).

Kojima, S., Yoneda, T., Morimoto, W. & Homma, M. Effect of PlzD, a YcgR homolog of c-di-GMP binding protein, on polar flagellar motility in Vibrio alginolyticus. J. Biochem. 166, mvz014 (2019).

Ko, J. et al. Structure of PP4397 reveals the molecular basis for different c-di-GMP binding modes by Pilz domain proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 398, 97–110 (2010).

Chen, T., Pu, M., Subramanian, S., Kearns, D. & Rowe-Magnus, D. PlzD modifies Vibrio vulnificus foraging behavior and virulence in response to elevated c-di-GMP. mBio 14, e01536-23 (2023).

Amikam, D. & Galperin, M. Y. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22, 3–6 (2006).

Pratt, J. T., Tamayo, R., Tischler, A. D. & Camilli, A. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12860–12870 (2007).

Galperin, M. Y. & Chou, S. H. Structural conservation and diversity of PilZ-related domains. J. Bacteriol. 202, e00664-19 (2020).

Ryjenkov, D. A., Simm, R., Römling, U. & Gomelsky, M. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP: the PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30310–30314 (2006).

Benach, J. et al. The structural basis of cyclic diguanylate signal transduction by PilZ domains. EMBO J. 26, 5153–5166 (2007).

Hou, Y. J. et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of c-di-GMP–bound YcgR regulating flagellar motility in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 808–821 (2020).

Paul, K., Nieto, V., Carlquist, W. C., Blair, D. F. & Harshey, R. M. The c-di-GMP binding protein YcgR controls flagellar motor direction and speed to affect chemotaxis by a “Backstop Brake” mechanism. Mol. Cell 38, 128–139 (2010).

Nieto, V. et al. Under elevated c-di-GMP in Escherichia coli, YcgR alters flagellar motor bias and speed sequentially, with additional negative control of the flagellar regulon via the adaptor protein RssB. J. Bacteriol. 202, e00578-19 (2019).

Rusch, D. B. & Rowe-Magnus, D. A. Complete genome sequence of the pathogenic Vibrio vulnificus type strain ATCC 27562. Genome Announc. 5, e00907-17 (2017).

Pazy, Y. et al. Identical phosphatase mechanisms achieved through distinct modes of binding phosphoprotein substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1924–1929 (2010).

Hyakutake, A. et al. Only one of the five CheY homologs in vibrio cholerae directly switches flagellar rotation. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8403–8410 (2005).

Spratt, M. R. & Lane, K. Navigating environmental transitions: the role of phenotypic variation in bacterial responses. mBio 13, e02212-22 (2022).

Moreno-Gámez, S. How bacteria navigate varying environments. Science 378, 845–845 (2022).

McDougald, D., Rice, S. A., Barraud, N., Steinberg, P. D. & Kjelleberg, S. Should we stay or should we go: mechanisms and ecological consequences for biofilm dispersal. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 39–50 (2012).

Ge, Y. & Charon, N. W. Molecular characterization of a flagellar/chemotaxis operon in the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 153, 425–431 (1997).

Chang, Y. et al. Molecular mechanism for rotational switching of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 1041–1047 (2020).

Lambert, B. S., Fernandez, V. I. & Stocker, R. Motility drives bacterial encounter with particles responsible for carbon export throughout the ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 4, 113–118 (2019).

Stocker, R., Seymour, J. R., Samadani, A., Hunt, D. E. & Polz, M. F. Rapid chemotactic response enables marine bacteria to exploit ephemeral microscale nutrient patches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4209–4214 (2008).

Raina, J. B. et al. Chemotaxis shapes the microscale organization of the ocean’s microbiome. Nature 605, 132–138 (2022).

Raina, J. B., Fernandez, V., Lambert, B., Stocker, R. & Seymour, J. R. The role of microbial motility and chemotaxis in symbiosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 284–294 (2019).

Seymour, J. R., Amin, S. A., Raina, J. B. & Stocker, R. Zooming in on the phycosphere: the ecological interface for phytoplankton–bacteria relationships. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17065 (2017).

Xu, L. et al. A cyclic di-GMP–binding adaptor protein interacts with a chemotaxis methyltransferase to control flagellar motor switching. Sci. Signal. 9, ra102 (2016).

Tamar, E., Koler, M. & Vaknin, A. The role of motility and chemotaxis in the bacterial colonization of protected surfaces. Sci. Rep. 6, 19616 (2016).

Sourjik, V. & Berg, H. C. Localization of components of the chemotaxis machinery of Escherichia coli using fluorescent protein fusions. Mol. Microbiol. 37, 740–751 (2000).

Roggo, C., Carraro, N. & van der Meer, J. R. Probing chemotaxis activity in Escherichia coli using fluorescent protein fusions. Sci. Rep. 9, 3845 (2019).

Coleman, J. L., Crowley, J. T., Toledo, A. M. & Benach, J. L. The HtrA protease of Borrelia burgdorferi degrades outer membrane protein BmpD and chemotaxis phosphatase CheX. Mol. Microbiol. 88, 619–633 (2013).

Altinoglu, I. et al. Analysis of HubP-dependent cell pole protein targeting in Vibrio cholerae uncovers novel motility regulators. PLoS Genet. 18, e1009991 (2022).

Lertsethtakarn, P. & Ottemann, K. M. A remote CheZ orthologue retains phosphatase function. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 225–235 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. The hypoxia-associated localization of chemotaxis protein CheZ in Azorhizorbium caulinodans. Front. Microbiol. 12, 731419 (2021).

Terry, K., Go, A. C. & Ottemann, K. M. Proteomic mapping of a suppressor of non-chemotactic cheW mutants reveals that Helicobacter pylori contains a new chemotaxis protein. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 871–882 (2006).

Wuichet, K. & Zhulin, I. B. Origins and diversification of a complex signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Sci. Signal. 3, ra50 (2010).

Gumerov, V. M., Andrianova, E. P. & Zhulin, I. B. Diversity of bacterial chemosensory systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 61, 42–50 (2021).

Grognot, M., Nam, J. W., Elson, L. E. & Taute, K. M. Physiological adaptation in flagellar architecture improves <I>Vibrio alginolyticus</I> chemotaxis in complex environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2301873120 (2023).

Amin, M. et al. Phosphate sink containing two-component signaling systems as tunable threshold devices. PLoS Comput. Biol. 10, e1003890 (2014).

Sourjik, V. & Schmitt, R. Phosphotransfer between CheA, CheY1, and CheY2 in the chemotaxis signal transduction chain of Rhizobium meliloti. Biochemistry 37, 2327–2335 (1998).

Porter, S. L. et al. The CheYs of Rhodobacter sphaeroides*. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32694–32704 (2006).

Dalia, A. B., McDonough, E. & Camilli, A. Multiplex genome editing by natural transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 8937–8942 (2014).

Edwards, R. A., Keller, L. H. & Schifferli, D. M. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207, 149–157 (1998).

Chodur, D. M. et al. The proline variant of the W[F/L/M][T/S]R cyclic di-GMP binding motif suppresses dependence on signal association for regulator function. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00344–17 (2017).

Taute, K. M., Gude, S., Tans, S. J. & Shimizu, T. S. High-throughput 3D tracking of bacteria on a standard phase contrast microscope. Nat. Commun. 6, 8776 (2015).

Grognot, M. & Taute, K. M. A multiscale 3D chemotaxis assay reveals bacterial navigation mechanisms. Commun. Biol. 4, 669 (2021).

Ershov, D. et al. TrackMate 7: integrating state-of-the-art segmentation algorithms into tracking pipelines. Nat. Methods 19, 829–832 (2022).

Tinevez, J. Y. et al. TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods 115, 80–90 (2017).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Stols, L. et al. A new vector for high-throughput, ligation-independent cloning encoding a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. Protein Expr. Purif. 25, 8–15 (2002).

Shuvalova, L. Structural genomics and drug discovery, methods and protocols. Methods Mol. Biol. 1140, 137–143 (2014).

Minor, W., Cymborowski, M., Otwinowski, Z. & Chruszcz, M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution—from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr 62, 859–866 (2006).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Agirre, J. et al. The CCP4 suite: integrative software for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 79, 449–461 (2023).

Murshudov, G. N. et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 67, 355–367 (2011).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Cohen, S. X. et al. ARP/wARPand molecular replacement: the next generation. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 64, 49–60 (2007).

Painter, J. & Merritt, E. A. TLSMDweb server for the generation of multi-group TLS models. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 39, 109–111 (2006).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2009).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. UCSF Chimera, MODELLER, and IMP: an integrated modeling system. J. Struct. Biol. 179, 269–278 (2012).

Eddy, S. R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763 (1998).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10, 421 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. Muscle5: high-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nat. Commun. 13, 6968 (2022).

Johnson, L. S., Eddy, S. R. & Portugaly, E. Hidden Markov model speed heuristic and iterative HMM search procedure. BMC Bioinform. 11, 431 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by funding from Indiana University FRSP-Seed Program and the Johnson Center for Innovation and Translational Research to D.R.M., the IUB-Colonel Bayard Franklin Floyd Memorial Fund in Microbiology to S.M., and HHS/NIH/NIAID Contract Nos. HHSN272201700060C and 75N93022C00035 to K.J.F.S. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). Access to LS-CAT and computation resources is coordinated by the Northwestern Structural Biology Facility, which is funded in part by the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Research Center award from the NCI P30CA060553. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript is the result of funding in whole or in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy. Through acceptance of this federal funding, NIH has been given the right to make this manuscript publicly available in PubMed Central upon the Official Date of Publication, as defined by NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R.-M. conceived the study and designed the research. A.F., C.L., Y.H., and G.M. performed experiments and collected data. B.F., R.P., D.R., L.S., K.J.F.S., and D.R.-M. carried out data analysis and visualization. B.F., R.P., and D.R. developed analytical tools and software. A.F., C.L., G.M., R.P., D.R., L.S., K.J.F.S., and D.R.-M. interpreted the results. D.R.-M. and K.J.F.S. supervised the study and drafted the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors discussed the results, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Xiaohui Zhou and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Tobias Goris. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frederick, A., Lopes, C., Fulton, B. et al. Altering chemotaxis as a strategy to enhance the foraging range of motility-restricted bacteria. Commun Biol 9, 197 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09475-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09475-w